What do you think?

Rate this book

232 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1972

‘Dandelions grew among the weeds. Their leaves spread wide and low, thrusting aside the hardy growth around them. Full of vitality, and large for dandelions, they radiated in all directions. You wondered—whether the dandelions in this region were stronger, more determined to live, than those elsewhere. They were all already producing buds; some had bloomed, with three or even four flowers—the petals uncommonly thick, their yellow unusually deep.’

‘Here we have the emptiness, the nothingness, of the Orient. My own works have been described as works of emptiness, but it is not to be taken for the nihilism of the West.’

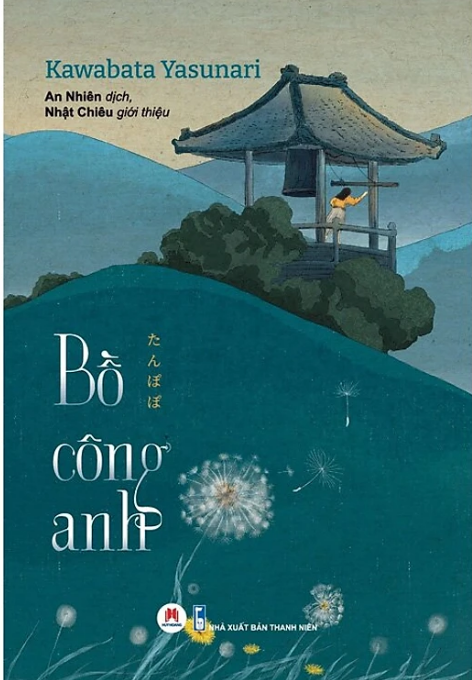

"'You were so quick to cry when you were little,' she said. 'You used to feel sorry for the camellia blossoms when they dropped, so you would gather them up. Put them in envelopes, between the pages of a book. I never once saw you sweep the flowers up and throw them away.'" (78)Left unfinished at the time of his death in 1972, Dandelions is Kawabata's final novel. It has only three main characters: Ineko, who has been diagnosed with somagnosia (a condition that leaves her suddenly unable to see certain bodies); Kuno, who is Ineko's lover, and whose body Ineko frequently cannot see; and Ineko's mother. The novel begins when Kuno and Ineko's mother have just left Ineko at a madhouse in a town next to the Ikuta River, whose banks are covered with dandelions; what follows is a long conversation between Kuno and Ineko's mother, interspersed with a number of flashbacks related to Ineko's past. The novel is clearly unfinished, but there is enough in it to make it worth reading. The beginning is especially good—the conversation between Kuno and Ineko's mother as they walk away from the madhouse is wonderful. There's a Japanese phrase—tōne no sasu kane (a bell with a distant ring)—which I think captures the novel well.