What do you think?

Rate this book

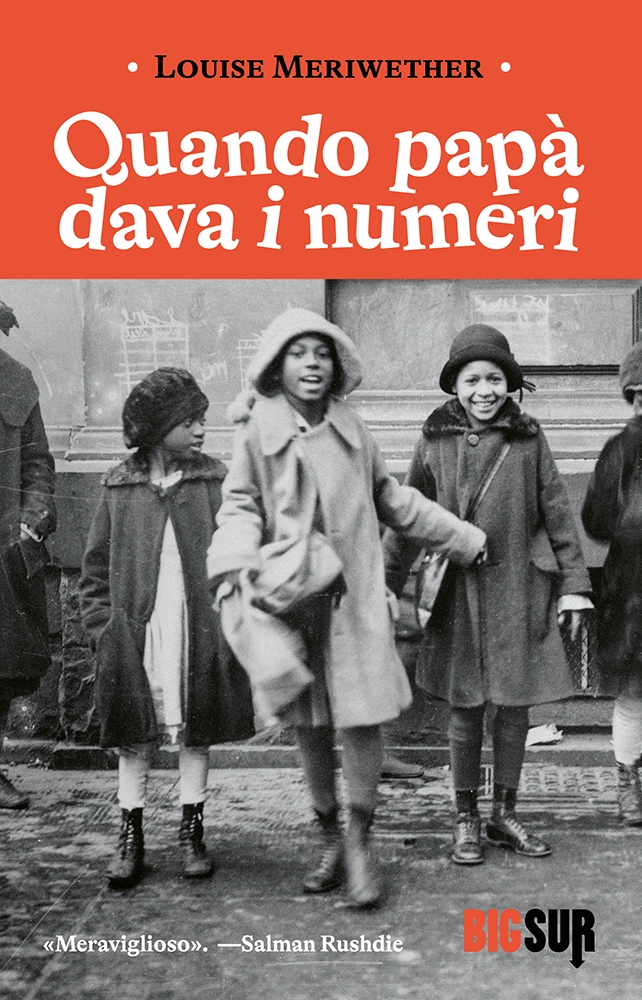

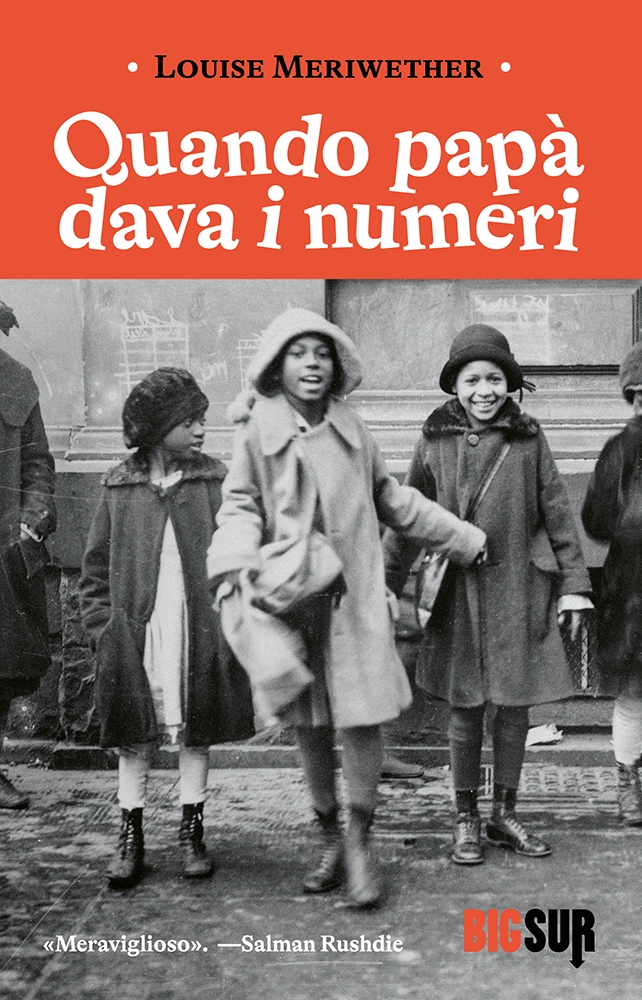

211 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1970

Compare the heroine of this book - to say nothing of the landscape - with the heroine of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and you will see to what extent poverty wears a color - and also, as we put it in Harlem, arrives at an attitude. By this time, the heroine of Tree...is among those troubled Americans, that silent (!) majority which wonders what black Francie wants, and why she's so unreliable as a maid.The landscape that Baldwin references is the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn in Smith's novel, written in 1943, and, obviously, Harlem in Meriwether's book, written in 1970. Having read both books now, I find Meriwether's novel more realistic, grittier. I'm one of the few who didn't care that much for A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, long assuming that it was because I read it too late in my life (rather than as a younger reader as so many who clearly love the book). But after reading Meriwether's book that covers some similar situations, but illustrates the real issues that go just beyond class, I find Meriwether's book much more relevant to shit going on in our country today, including (but not limited to) wrongful incarceration.

(p5-6)