What do you think?

Rate this book

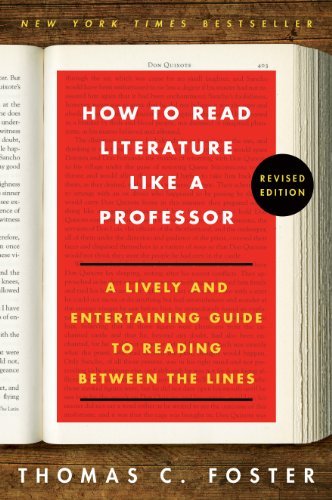

A thoroughly revised and updated edition of Thomas C. Foster's classic guide—a lively and entertaining introduction to literature and literary basics, including symbols, themes, and contexts—that shows you how to make your everyday reading experience more rewarding and enjoyable.

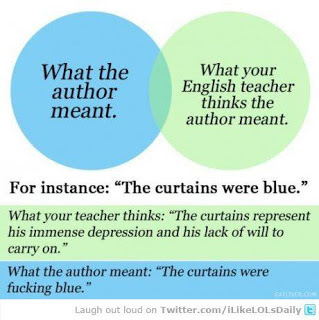

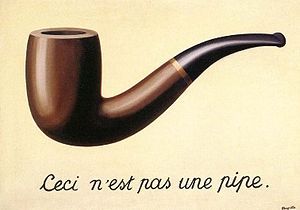

While many books can be enjoyed for their basic stories, there are often deeper literary meanings interwoven in these texts. How to Read Literature Like a Professor helps us to discover those hidden truths by looking at literature with the eyes—and the literary codes—of the ultimate professional reader: the college professor.

What does it mean when a literary hero travels along a dusty road? When he hands a drink to his companion? When he's drenched in a sudden rain shower? Ranging from major themes to literary models, narrative devices, and form, Thomas C. Foster provides us with a broad overview of literature—a world where a road leads to a quest, a shared meal may signify a communion, and rain, whether cleansing or destructive, is never just a shower—and shows us how to make our reading experience more enriching, satisfying, and fun.

This revised edition includes new chapters, a new preface, and a new epilogue, and incorporates updated teaching points that Foster has developed over the past decade.

366 pages, Kindle Edition

First published February 18, 2003

QUICK QUIZ: What do John Cleese, Cole Porter, Moonlighting, and Death Valley Days have in common? No, they’re not part of some Communist plot. All were involved with some version of The Taming of the Shrew...I'm insanely thrilled with this book. For many of us it is impossible to attend literature lectures and have forgotten most of the ones we did honor with our presence, many years ago. So this is it. Read the book and become wiser. The information might not be unfamiliar to many of us, but it certainly deepens our experience of serious books.

If you look at any literary period between the eighteenth and twenty-first centuries, you’ll be amazed by the dominance of the Bard. He’s everywhere, in every literary form you can think of. And he’s never the same: every age and every writer reinvents its own Shakespeare. All this from a man who we’re still not sure actually wrote the plays that bear his name.

Try this. In 1982 Paul Mazursky directed an interesting modern version of The Tempest. It had an Ariel figure (Susan Sarandon), a comic but monstrous Caliban (Raul Julia), and a Prospero (famed director John Cassavetes), an island, and magic of a sort. The film’s title? Tempest. Woody Allen reworked A Midsummer Night’s Dream as his film A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy.

West Side Story famously reworks Romeo and which resurfaces again in the 1990s, in a movie featuring contemporary teen culture and automatic pistols. And that’s a century or so after Tchaikovsky’s ballet based on the same play.

The BBC series Masterpiece Theatre has recast Othello as a contemporary story of black police commissioner John Othello, his lovely white wife Dessie, and his friend Ben Jago, deeply resentful at being passed over for promotion. The action will surprise no one familiar with the original.

Nor is the Shakespeare adaptation phenomenon restricted to the stage and screen. Jane Smiley rethinks King Lear in her novel A Thousand Acres.

I hate “political” writing—novels, plays, poems. They don’t travel well, don’t age well, and generally aren’t much good in their own time and place, however sincere they may be. I speak here of literature whose primary intent is to influence the body politic—for instance, those works of socialist realism (one of the great misnomers of all time) of the Soviet era in which the plucky hero figures out a way to increase production and thereby meet the goals of the five-year plan on the collective farm—what I once heard the great Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes characterize as the love affair between a boy, and girl, and a tractor. Overtly political writing can be one-dimensional, simplistic, reductionist, preachy, dull.Don't we find those preachy dullness in too many novels nowadays? I like the idea of calling it programmatic. Word-dumping or information dumping were my favorite two concepts in addressing it. But I have something new to call it. :-))