What do you think?

Rate this book

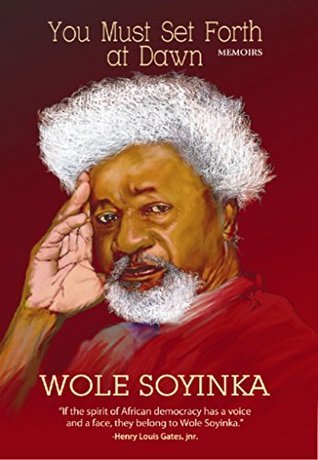

784 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 2006

Just when it seems that the premise of the latest tell-all memoir can't get any thinner, this powerful exemplar of the genre arrives on bookshelves. Soyinka, winner of the 1986 Nobel Prize for literature, delivers a book that is as much a history of a country as it is the story of his life. That Soyinka's story so closely aligns with the history of Nigeria testifies to his ongoing commitment to the cause of democracy, but the focus on politics leaves a few reviewers wishing for more of the personal stories found in Ak_