What do you think?

Rate this book

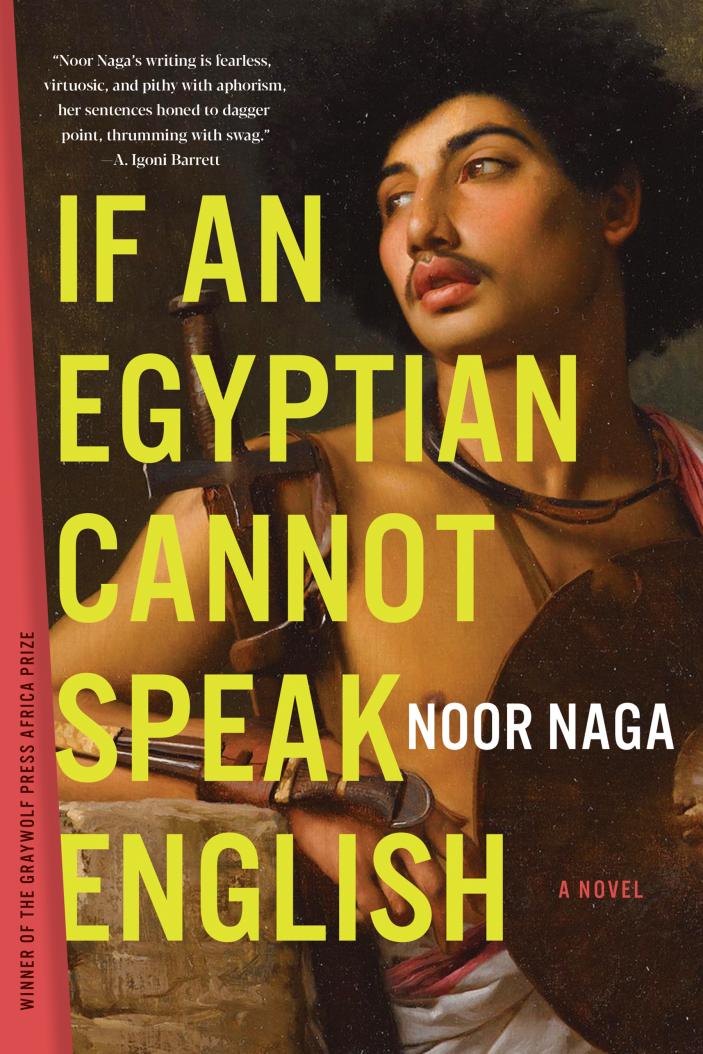

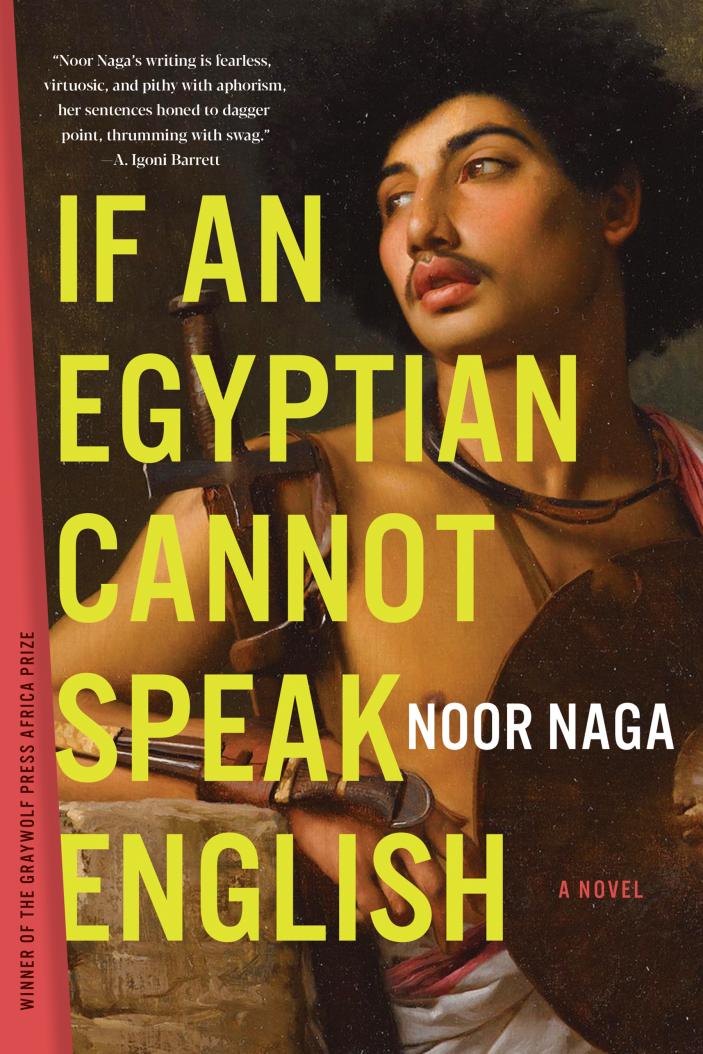

204 pages, Kindle Edition

First published April 12, 2022

“I tried to tell a taxi driver I wanted to get off on the west side of Zamalek, and it was like he’d never heard of west. No one uses the cardinal points for directions. The Dokki side? he asked and I wasn’t sure, couldn’t say. The maps are all wrong. Where the roads are numbered (rarely), they are not ordered consecutively, and when they are named, no one uses those names. The landmarks are arbitrary—a discontinued post office, a banana-seller. The bridges are referred to by dates. I’ll take the 26th of July to Zamalek and then you point where you want to get off, the driver says politely. It’s as though the city were deliberately designed to resist comprehension and to discipline those who left for daring to return. You have either lived here and you know, or you never have and never will.”

“I swear this isn’t who I am. I’m not a violent person, but there is a violence that moves through you like a live current when you hate what someone has made you become. I feel estranged from myself the longer I am with her, made criminal solely because she is afraid, made pathetic because she pities me—a poor boy though I never was.”

“I resent [my father] because I recognize him. This desperation to refashion ourselves into the most pleasing form makes fools of us both. We’re pliable and capricious, shed our skin at the slightest threat, and ultimately stick out everywhere we go. We were both more convincing Egyptians in New York than we’d ever be on this side of the Atlantic. There I had enough Arabic to flirt with the Halal Guys and the Yemenis at my deli. At school, identity was simple: my name etched in hieroglyphics on a silver cartouche at my throat. I could say, Back home, we do it like this, pat our bread flat and round, never having patted bread flat or otherwise. But here I keep saying I’m Egyptian and no one believes me. I’m the other kind of other, someone come from abroad who could just as easily return there.”

Question: If an Egyptian cannot speak English, who is telling his story?

_______________________________

We fall asleep in each other’s arms. We watch a film together and fall asleep in our outdoor clothes, in each other’s arms, her scratchy head beneath my chin. The grief numbs us both. I find myself measuring for the first time how far America is from Cairo, let alone Shobrakheit. How to bridge this ocean? How to explain all I left behind to get even this far?

We believed, we really believed that the revolution would succeed on the strength of our brotherhood, and the nobility of our cause. Had we been less occupied with documenting the losses, circulating names and dates, video footage, we might have noticed earlier that everything was not as it seemed. There was money pouring in from overseas, along with vested interests. We thought we were toppling a regime, but the whole world was involved. It seems so obvious now, but if you weren’t there, you can’t possibly judge. I can’t tell you what it was like.

William doesn’t even realize what’s at stake when I am asked by shopkeepers and street children and sugar-cane juicers where I’m from. And why should he realize? They ask him too. Those outside of a language, of a culture, see furniture through a window and believe it is a room. But those inside know there are infinite rooms just out of view, and that they can always be more deeply inside.