What do you think?

Rate this book

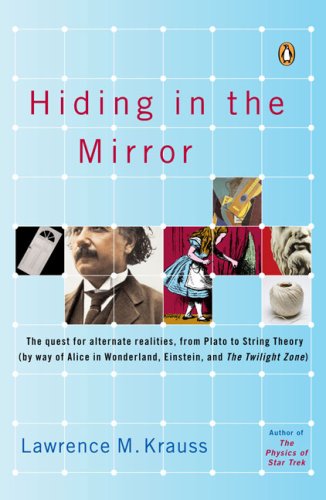

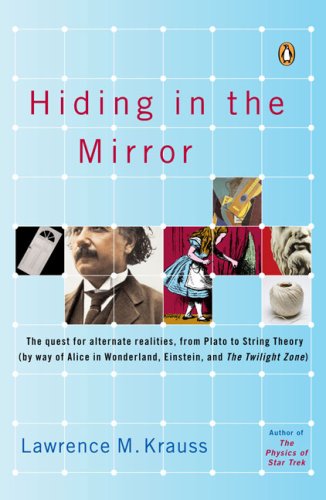

288 pages, Paperback

First published October 20, 2005

I will also attempt to present a "fair and balanced" treatment of string theory (in a "non-Fox News" sense)

This was embarrassing, because the earth was, and is, known to be older than that, except by school boards in Ohio, Georgia, and Kansas perhaps.

As any European high school student could tell you, the sum of the angles inside this triangle is 180 degrees.

Excellent. A physicist examines the history of our fascination with extra spatial dimensions in religion, philosophy, popular culture, and science. Most of the emphasis is on science and, in particular, string theories.