What do you think?

Rate this book

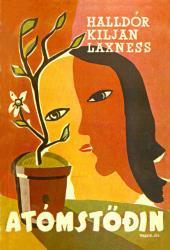

276 pages

First published January 1, 1948

"I have seen all the pictures from Buchenwald," said Benjamin. "It is impossible to be a poet any longer. The emotions stand still and will not heed the helm after you have studied the pictures of those emaciated bodies; and those dead gaping mouths. The love life of the trout, the rose glowing on the heath, dichterliebe, it's all over. Fini. Slutt. Tristram and Isolde are dead. They died in Buchenwald. And the nightingale has lost its voice because we have lost our ears, our ears are dead, our ears died in Buchenwald. And now nothing less than suicide will do any more, the square root of onanism."

..."But it is always possible to kill someone," said the god Brilliantine.

The other replied, "Yes, if one has an atom bomb. It is both intolerable and unseemly that a divine being like me, Benjamin, should not have an atom bomb while Du Pont has an atom bomb."

"I shall now tell you what you ought to do," said the organist, and placed before him a plate containing a few curled-up pastries and some broken biscuits. "You should compose a ballad about Du Pont and his atom bomb."

"I know what I'm going to do," said the god Brilliantine. "I'm going to divorce my wife and become a success. I'm going to be a political figure. I'm going to become a Minister and swear on oath; and get a decoration."

"You two are slipping," said the organist. "When I first knew you, you were satisfied just to be God; gods."

"Why may we not achieve a little success?" said the god. "Why may we not get a decoration?"

"Petty criminals never get decorations," said the organist. "Only the lackeys of the big ones get that sort of thing. To become a political success a man needs to have a millionaire. And you two have lost your millionaire. A petty thief does not become a Minister; to be a petty thief is the sort of humiliation which can only happen to gods, such as being born in a manger; people pity them, so that their names do not even get into the papers. Go to Sweden for the millionaires and offer your territorial waters, go to America and sell the country; then you will become a Minister, then you will get a decoration."

"I'm ready at any time to offer the Swedes the territorial waters and sell the country to the Yanks," said the god Brilliantine.

"Yes, but it does you not the slightest bit of good if you have lost your millionaire," said the organist.

"So you think I shouldn't bother to divorce my wife?" asked the god.

"Is there any reason for divorcing wives unless they themselves wish it?" asked the organist.

"But at least it will be all right for us to shorten Oli Figure by a head?" said the god.

"It all depends," said the organist. "Have a biscuit."