Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

comments

from the Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses group.

Showing 1-20 of 419

I'm pretty sure we read it at one of my schools. But I'm also pretty sure that it was a much abridged edition. I could not imagine wading through Dickens' long descriptions as a child, but greatly enjoy them now. I used to live on Blackheath, near the top of Shooters' Hill, so the description of the coach passengers trudging up in the rain came close to home! R.

I'm pretty sure we read it at one of my schools. But I'm also pretty sure that it was a much abridged edition. I could not imagine wading through Dickens' long descriptions as a child, but greatly enjoy them now. I used to live on Blackheath, near the top of Shooters' Hill, so the description of the coach passengers trudging up in the rain came close to home! R.

Coincidence! My wife and I are also reading A Tale of Two Cities in tandem. I'm so busy, though, that I'm finding it a bit hard to keep up. I've yet to reach the Gorgon chapter. R.

Coincidence! My wife and I are also reading A Tale of Two Cities in tandem. I'm so busy, though, that I'm finding it a bit hard to keep up. I've yet to reach the Gorgon chapter. R.

Ooh yes, I like that! It also makes it clear that Diana is of such a stature that she is not easily hidden.

Ooh yes, I like that! It also makes it clear that Diana is of such a stature that she is not easily hidden. I find I am really coming to like these later 19th-century painters who still stuck to an academic technique, yet often managed to do something quite interesting with it. R.

As you may have noticed, I have been absent from discussion of this book (though I have read it), and may indeed be largely absent from the next book also. The first few lectures of a new course I am preparing are taking me way out of my comfort zone, and only when I get back into known waters will I find time for further explorations. Sorry about that! Roger.

As you may have noticed, I have been absent from discussion of this book (though I have read it), and may indeed be largely absent from the next book also. The first few lectures of a new course I am preparing are taking me way out of my comfort zone, and only when I get back into known waters will I find time for further explorations. Sorry about that! Roger.

Elena, that's twice recently that you have commented on the beauty and consolations, even as the aftermath of rape. I am inclined to agree. But did you read that Jia Tolentino article I posted as I think comment 5/2? She very specifically engages with this as a feminist, claiming that the pretty endings only make the offense worse. But I'm paraphrasing—badly, I'm sure. Do read it! R.

Elena, that's twice recently that you have commented on the beauty and consolations, even as the aftermath of rape. I am inclined to agree. But did you read that Jia Tolentino article I posted as I think comment 5/2? She very specifically engages with this as a feminist, claiming that the pretty endings only make the offense worse. But I'm paraphrasing—badly, I'm sure. Do read it! R.

Thanks, Jim. Etiology is a word I have heard but never used. Looks as though it could be useful, though, so I'd better learn it! And you are right about Ovid and performance: not that he wrote to be recited, but his stories are mostly told (ie. performed) by someone, and even those that aren't have the sense of being acted out rather than simply happening. As a director and librettist, I am on home ground here. R.

Thanks, Jim. Etiology is a word I have heard but never used. Looks as though it could be useful, though, so I'd better learn it! And you are right about Ovid and performance: not that he wrote to be recited, but his stories are mostly told (ie. performed) by someone, and even those that aren't have the sense of being acted out rather than simply happening. As a director and librettist, I am on home ground here. R.

Totally off topic, Kalliope, but my I have recently been watching the television show El Ministerio del Tiempo with my son, who is practicing his Spanish. Do you know it? The theme is time-travel: each week, emissaries from the ministry go back to the past to prevent something happening that would deflect the course of Spanish history. For instance, when it was discovered that the young Lope de Vega was enlisted on a ship destroyed in the Spanish Armada, the challenge was to get him onto one of the few ships that didn't sink.

Totally off topic, Kalliope, but my I have recently been watching the television show El Ministerio del Tiempo with my son, who is practicing his Spanish. Do you know it? The theme is time-travel: each week, emissaries from the ministry go back to the past to prevent something happening that would deflect the course of Spanish history. For instance, when it was discovered that the young Lope de Vega was enlisted on a ship destroyed in the Spanish Armada, the challenge was to get him onto one of the few ships that didn't sink.Anyway, Diego Velázquez comes in as a minor but recurrent character. In the first episode, they open one of the time doors and see a number of rambunctious children scurrying back into their poses for Las Meniñas. In the one we saw last night, Velázquez corners the young Picasso in a Madrid bar and asks him what he likes best in the Prado. His first answer is Goya (he doesn't know whom he is speaking to), but later says he likes Velázquez even more.

Which reminds me to add: the Apollo on your catalog cover looks wonderful, without any of the oddness that comes from seeing him as part of that otherwise realistic group. R.

Well, what ARE nymphs? Is there a precise technical definition, as in female semi-deities associated with the natural world, or merely a pool of beautiful and ever-young women, conveniently on hand whenever some god gets horny? I mean, who else is there to cast as rape victims other than nymphs? R.

Well, what ARE nymphs? Is there a precise technical definition, as in female semi-deities associated with the natural world, or merely a pool of beautiful and ever-young women, conveniently on hand whenever some god gets horny? I mean, who else is there to cast as rape victims other than nymphs? R.

Kalliope wrote: "I am glad you liked my idea of the Cinderella mix. I was fearing boos...

Kalliope wrote: "I am glad you liked my idea of the Cinderella mix. I was fearing boos...And I am trying to imagine now Rubens depicting Mary Poppins."

I'm sorry I misattributed your idea in my post. As for Rubens doing Mary Poppins, think his Assumption of the Virgin (Antwerp or Düsseldorf) and secularize it. Pretty horrible thought, actually. R.

Roman Clodia wrote: "lets say someone joining the stories of Cinderella with Hansel & Gretel with Moby Dick with Mary Poppins with Romeo & Juliet (which he does..) etc..."

Roman Clodia wrote: "lets say someone joining the stories of Cinderella with Hansel & Gretel with Moby Dick with Mary Poppins with Romeo & Juliet (which he does..) etc..."That's quite a literary cocktail you have stirred up there! I am thinking of Stephen Sondheim in Into the Woods or the stylistic legerdemain of David Mitchell in Cloud Atlas, but this is something else again. R.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Ah well, hopefully the next book will revive your interest :)"

Roman Clodia wrote: "Ah well, hopefully the next book will revive your interest :)"Thanks. I'm pretty sure it will. More than anyone else here, I think, it is the "further metamorphoses" of our group's title that mainly interest me. Which puts me in a different camp from you, but none the worse for either of us. R.

Vit wrote: "The tale of Ceres and Proserpine is one of the archetypal myths explaining the existence of seasons."

Vit wrote: "The tale of Ceres and Proserpine is one of the archetypal myths explaining the existence of seasons."My point exactly, Vit. Which is why I am puzzled that myths that are surely far less archetypal, such as Europa or Actaeon, should have spawned so many more reinterpretations over the centuries. The closest parallel to this, I think, in terms of descent to the underworld and at least partial return, is the story of Orpheus, which has proved greatly more fecund in later receptions.

As always, I love the balanced cadences of the Garth translation. R.

Elena wrote: "How can you separate the story teller from the story, kinda like the dancer and the dance..."

Elena wrote: "How can you separate the story teller from the story, kinda like the dancer and the dance..."What is this in response to, Elena?

Though of course you can separate the dancer from the dance, the singer from the song, and so on. R.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Roger wrote: "What he has here, after all, is central to the belief system: the explanation of why we have winter and summer."

Roman Clodia wrote: "Roger wrote: "What he has here, after all, is central to the belief system: the explanation of why we have winter and summer."Um, the Romans were far too sophisticated to 'believe' this story - t..."

Poor choice of words, perhaps. I am not suggesting belief in the sense that fundamentalists believe the literal stories of the Creation and the Garden of Eden. But underlying both of those are existential questions that demand answers of some kind, and many of us who don't literally believe still occasionally find the stories a convenient shorthand for our more sophisticated answers.

As for the rest, I see what you and Kalliope are saying—intellectually. But on the level of personal enjoyment, Book V is the first that has pretty much failed to grab me. And in terms of reception, it has triggered notably fewer artworks than other books, certainly as reflected in our thread, and I think also in life.

But I am not much for literary postmodernism either! R.

Kalliope wrote: "On embedded narratives. ..."

Kalliope wrote: "On embedded narratives. ..."I like all of this, but in a rather intellectual way. You say: "This creates a tripartite analogy between three pairs of audience and narrator. As Ceres is to Arethusa, and as Minerva is to the Muse reporting Calliope's song, so is the reader to Ovid." This is very neat, but instead of drawing the reader (OK, this reader) further into the story, as you might expect, it actually has the effect of distancing him. Not you, though?

This analysis is interesting, though, in that it adds the dimension of depth (your various layers) to what is normally the horizontal process of storytelling. But it also breaks up the continuity.

If you tell the Proserpina story from memory, for example, you have the original abduction, Ceres' intervention with Jupiter, the bite of the pomegranate spoiling her release, and the eventual compromise that gives us the seasons. But as Ovid tells it, you get into it semi-obliquely, first via Typhoeus and Sicily, then via Venus and Cupid. Proserpina gets abducted, then we have the episode with Cynae. Ceres looks for her, and we have another episode with Stellio. She learns of what happens via Arethusa. The pomegranate bit involves a separate mini-story about Ascalaphus, and so on.

I wonder if Ovid would have done this with a less familiar story? What he has here, after all, is central to the belief system: the explanation of why we have winter and summer. All his readers would have known it in some form, more so than many of the other stories that he includes. So he is not so much telling the story as contextualizing it.

As I say, though, I find it distancing. And I wonder if this is any kind of answer to my earlier question of why such an important story should have spurred comparatively little re-exploration in the visual arts and music? Some, certainly, but surprisingly little in relation to the importance of the concept behind the myth. R.

Kalliope wrote: "I finished reading the Notes of the Simpson edition for Book 5.

Kalliope wrote: "I finished reading the Notes of the Simpson edition for Book 5.I will be posting a selection of the comments during this week."

Yes, anything you can do to spur further discussion would be welcome. For some reason, despite containing one of the seminal stories, Book V does not seem to have fired us up. R.

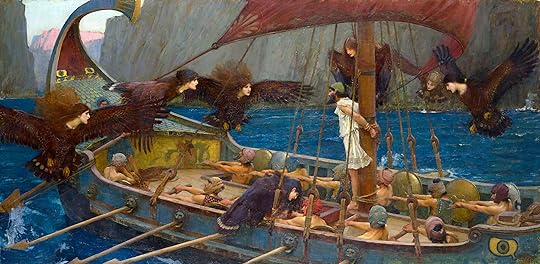

And in another book of myths, Odysseus encounters the Sirens. Here is the version by John William Waterhouse (1849–1917), whom I am coming to enjoy more and more. His birdwomen are really quite something! R.

And in another book of myths, Odysseus encounters the Sirens. Here is the version by John William Waterhouse (1849–1917), whom I am coming to enjoy more and more. His birdwomen are really quite something! R.

Waterhouse: Ulysses and the Sirens (1891, Melbourne)

— detail of the above