The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

The Metaphysical Club

PHILOSOPHY AND POLITICS

>

7. THE METAPHYSICAL CLUB ~ August 5th - August 11th ~~ Part Three - Chapter Seven ~ (151- 176) ~ The Peirces ~No-Spoilers, please

message 2:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 01:39AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Welcome folks to the discussion of The Metaphysical Club.

Message One - on each non spoiler thread - will help you find all of the information that you need for each week's reading.

For Week Seven - for example, we are reading and discussing the following:

Week Seven - August 5th - August 11th

Part Three - Chapter Seven

The Peirces (151 - 176)

Please only discuss Chapter Seven through page 176 on this thread. However from now on you can also discuss any of the pages that came before this week's reading - including anything in the Preface or Introduction or anything in Chapter One through Chapter Six. However the main focus of this week's discussion is Chapter Seven.

This is a non spoiler thread.

But we will have in this folder a whole bunch of spoiler threads dedicated to all of the pragmatists or other philosophers or philosophic movements which I will set up as we read along and on any of the additional spoiler threads - expansive discussions about each of the pragmatists/philosophers/philosophic movements can also take place on any of these respective threads. Spoiler threads are also clearly marked.

If you have any links, or ancillary information about anything dealing with the book itself feel free to add this to our Glossary thread.

If you have lists of books or any related books about the people discussed, or about the events or places discussed or any other ancillary information - please feel free to add all of this to the thread called - Bibliography.

If you would like to plan ahead and wonder what the syllabus is for the reading, please refer to the Table of Contents.

If you would like to write your review of the book and present your final thoughts because maybe you like to read ahead - the spoiler thread where you can do all of that is called Book as a Whole and Final Thoughts. You can also have expansive discussions there.

For all of the above - the links are always provided in message one.

Always go to message one of any thread to find out all of the important information you need.

Bentley will be moderating this book and Kathy will be the backup.

Message One - on each non spoiler thread - will help you find all of the information that you need for each week's reading.

For Week Seven - for example, we are reading and discussing the following:

Week Seven - August 5th - August 11th

Part Three - Chapter Seven

The Peirces (151 - 176)

Please only discuss Chapter Seven through page 176 on this thread. However from now on you can also discuss any of the pages that came before this week's reading - including anything in the Preface or Introduction or anything in Chapter One through Chapter Six. However the main focus of this week's discussion is Chapter Seven.

This is a non spoiler thread.

But we will have in this folder a whole bunch of spoiler threads dedicated to all of the pragmatists or other philosophers or philosophic movements which I will set up as we read along and on any of the additional spoiler threads - expansive discussions about each of the pragmatists/philosophers/philosophic movements can also take place on any of these respective threads. Spoiler threads are also clearly marked.

If you have any links, or ancillary information about anything dealing with the book itself feel free to add this to our Glossary thread.

If you have lists of books or any related books about the people discussed, or about the events or places discussed or any other ancillary information - please feel free to add all of this to the thread called - Bibliography.

If you would like to plan ahead and wonder what the syllabus is for the reading, please refer to the Table of Contents.

If you would like to write your review of the book and present your final thoughts because maybe you like to read ahead - the spoiler thread where you can do all of that is called Book as a Whole and Final Thoughts. You can also have expansive discussions there.

For all of the above - the links are always provided in message one.

Always go to message one of any thread to find out all of the important information you need.

Bentley will be moderating this book and Kathy will be the backup.

message 3:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 02:05AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Make sure that you are familiar with the HBC's rules and guidelines and what is allowed on goodreads and HBC in terms of user content. Also, there is no self promotion, spam or marketing allowed.

Here are the rules and guidelines of the HBC:

http://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/5...

Please on the non spoiler threads: a) Stick to material in the present week's reading.

Also, in terms of all of the threads for discussion here and on the HBC - please be civil.

We want our discussion to be interesting and fun.

Make sure to cite a book using the proper format.

You don't need to cite the Menand book, but if you bring another book into the conversation; please cite it accordingly as required.

Now we can begin week seven....

Here are the rules and guidelines of the HBC:

http://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/5...

Please on the non spoiler threads: a) Stick to material in the present week's reading.

Also, in terms of all of the threads for discussion here and on the HBC - please be civil.

We want our discussion to be interesting and fun.

Make sure to cite a book using the proper format.

You don't need to cite the Menand book, but if you bring another book into the conversation; please cite it accordingly as required.

Now we can begin week seven....

message 4:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 05:27PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Chapter Summaries and Overview

Chapter Seven: The Peirces

Part 2, Chapter 7 - The Peirces, Section One

We are introduced to Charles Peirce, who helped influence pragmatic thinking.

Part 2, Chapter 7 - The Peirces, Section Two

In this section, the author introduces us to the world of Charles Peirce's father. This was a man who was quiet and brilliant. He expected more from his students, and even more from himself.

Math came to him easily, and yet he realized that it was not as easy for his students.

He tried to help them understand. Sometimes it worked and sometimes it did not.

However, he spent the majority of his adult life trying to prove that logic and statistics

could be used to predict outcomes. Charles Pierce's father believes the universe can

be known through statistics. This is the man whom Charles Peirce must succeed.

Part 2, Chapter 7 - The Peirces, Section Three

He seems to have lived in his father's shadow his entire young adult life. He works with his father and it becomes apparent that many expect him to exceed his father and create something new.

However, it is obvious that Charles cannot stay in his father's shadow and that his drug

addiction may cause problems.

His marriage to Harriet Melusina Fay does not seem very compatible either. From the little the author knows about Charles, there are many obstacles he must clear before he can be his own person.

Part 2, Chapter 7 - The Peirces, Section Four

In this section, the author introduces us to The Robinson v. Mandell case. This was also called the Howland Case and dealt with the disposition of wealth made in whaling.

We learn how Benjamin and Charles worked very well together on this case and became famous.

The author tells us how they were on the edge of a new way of thinking, and we learn that this will eventually lead to a portion of the pragmatic thinking that will begin to influence philosophical thinking shortly after the Civil War.

Part 3, Chapter 7 - The Peirces, Section 5

The culmination of this case is a climax in Charles Peirce's life. He has helped his father prove that the use of statistics could answer many questions that seemed to have no answer.

They used numbers to prove the validity of a signature. This upset the scientific world as much as it did the general public.

Benjamin let Charles ride his coattails. And it shows the timeline of how far Charles has come and where he might branch off next.

message 5:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 02:44AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Most folks want to know right off the bat - what is the title about? Here is a good posting explaining that.

The Metaphysical Club

by John Shook

The Metaphysical Club was an informal discussion group of scholarly friends, close from their associations with Harvard University, that started in 1871 and continued until spring 1879.

This Club had two primary phases, distinguished from each other by the most active participants and the topics pursued.

The first phase of the Metaphysical Club lasted from 1871 until mid-1875, while the second phase existed from early 1876 until spring 1879. The dominant theme of first phase was pragmatism, while idealism dominated the second phase.

Pragmatism - First Phase:

The "pragmatist" first phase of the Metaphysical Club was organized by Charles Peirce (Harvard graduate and occasional lecturer), Chauncey Wright (Harvard graduate and occasional lecturer), and William James (Harvard graduate and instructor of physiology and psychology).

These three philosophers were then formulating recognizably pragmatist views. Other active members of the "Pragmatist" Metaphysical Club were two more Harvard graduates and local lawyers, Nicholas St. John Green and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who were also advocating pragmatic views of human conduct and law.

Idealist - Second Phase:

The "idealist" second phase of the Metaphysical Club was organized and led by idealists who showed no interest in pragmatism: Thomas Davidson (independent scholar), George Holmes Howison (professor of philosophy at nearby Massachusetts Institute of Technology), and James Elliot Cabot (Harvard graduate and Emerson scholar). There was some continuity between the two phases.

Although Peirce had departed in April 1875 for a year in Europe, and Wright died in September 1875, most of the original members from the first phase were available for a renewed second phase.

By January 1876 the "Idealist" Metaphysical Club (for James still was referring to a metaphysical club in a letter of 10 February 1876) was meeting regularly for discussions first on Hume, then proceeding through Kant and Hegel in succeeding years.

Besides Davidson, Howison, and Cabot, the most active members appear to be William James, Charles Carroll Everett (Harvard graduate and Dean of its Divinity School), George Herbert Palmer (Harvard graduate and professor of philosophy), and Francis Ellingwood Abbott (Harvard graduate and independent scholar).

Other occasional participants include Francis Bowen (Harvard graduate and professor of philosophy), Nicholas St. John Green, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and G. Stanley Hall (Harvard graduate and psychologist).

The Metaphysical Club was a nine-year episode within a much broader pattern of informal philosophical discussion that occurred in the Boston area from the 1850s to the 1880s.

Chauncey Wright, renowned in town for his social demeanor and remarkable intelligence, had been a central participant in various philosophy clubs and study groups dating as early as his own college years at Harvard in the early 1850s.

Wright, Peirce, James, and Green were the most active members of the Metaphysical Club from its inception in 1871.

By mid-1875 the original Metaphysical Club was no longer functioning; James was the strongest connection between the first and second phases, helping Thomas Davidson to collect the members of the "Idealist" Metaphysical Club.

Link to the Hegel Club:

James also was a link to the next philosophical club, the "Hegel Club", which began in fall 1880 in connection with George Herbert Palmer's seminar on Hegel. By winter 1881 the Hegel Club had expanded to include several from the Metaphysical Club, including James, Cabot, Everett, Howison, Palmer, Abbott, Hall, and the newcomer William Torrey Harris who had taken up residence in Concord.

This Hegel Club was in many ways a continuation of the St. Louis Hegelian Society from the late 1850s and 1860s, as Harris, Howison, Davidson, and their Hegelian students had moved east.

The Concord Summer School of Philosophy (1879-1888), under the leadership of Amos Bronson Alcott and energized by the Hegelians, soon brought other young American scholars into the orbit of the Cambridge clubs, such as John Dewey.

The "Pragmatist" Metaphysical Club met on irregular occasions, probably fortnightly during the Club's most active period of fall 1871 to winter 1872, and they usually met in the home of Charles Pierce or William James in Cambridge.

This Club met for four years until mid-1875, when their diverse career demands, extended travels to Europe, and early deaths began to disperse them. The heart of the club was the close bonds between five very unusual thinkers on the American intellectual scene.

Chauncey Wright and Charles Sanders Peirce shared the same scientific interests and outlook, having adopted a positivistic and evolutionary stance, and their common love for philosophical discussion sparked the club's beginnings. Wright's old friend and lawyer Nicholas St. John Green was glad to be included, as was Peirce's good friend William James who had also gone down the road towards empiricism and evolutionism. William James brought along his best friend, the lawyer Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who like Green was mounting a resistance to the legal formalism dominating that era. Green brought fellow lawyer Joseph Bangs Warner, and the group also invited two philosophers who had graduated with them from Harvard, Francis Ellingwood Abbott and John Fiske, who were both interested in evolution and metaphysics.

Other occasional members were Henry Ware Putnam, Francis Greenwood Peabody, and William Pepperell Montague.

Activities of the "Pragmatist" Metaphysical Club were recorded only by Peirce, William James, and William's brother Henry James, who all describe intense and productive debates on many philosophical problems.

Both Peirce and James recalled that the name of the club was the "Metaphysical" Club. Peirce suggests that the name indicated their determination to discuss deep scientific and metaphysical issues despite that era's prevailing positivism and agnosticism. A successful "Metaphysical Club" in London was also not unknown to them. Peirce later stated that the club witnessed the birth of the philosophy of pragmatism in 1871, which he elaborated (without using the term 'pragmatism' itself) in published articles in the late 1870s. His own role as the "father of pragmatism" should not obscure, in Peirce's view, the importance of Nicholas Green. Green should be recognized as pragmatism's "grandfather" because, in Peirce's words, Green had "often urged the importance of applying Alexander Bain's definition of belief as 'that upon which a man is prepared to act,' from which 'pragmatism is scarce more than a corollary'." Chauncey Wright also deserves considerable credit, for as both Peirce and James recall, it was Wright who demanded a phenomenalist and fallibilist empiricism as a vital alternative to rationalistic speculation.

The several lawyers in this club took great interest in evolution, empiricism, and Bain's pragmatic definition of belief.

They were also acquainted with James Stephen's A General View of the Criminal Law in England, which also pragmatically declared that people believe because they must act. At the time of the Metaphysical Club, Green and Holmes were primarily concerned with special problems in determining criminal states of mind and general problems of defining the nature of law in a culturally evolutionary way.

Both Green and Holmes made important advances in the theory of negligence which relied on a pragmatic approach to belief and established a "reasonable person" standard. Holmes went on to explore pragmatic definitions of law that look forward to future judicial consequences rather than to past legislative decisions.

(Source: http://www.pragmatism.org/research/me...)

The Metaphysical Club

by John Shook

The Metaphysical Club was an informal discussion group of scholarly friends, close from their associations with Harvard University, that started in 1871 and continued until spring 1879.

This Club had two primary phases, distinguished from each other by the most active participants and the topics pursued.

The first phase of the Metaphysical Club lasted from 1871 until mid-1875, while the second phase existed from early 1876 until spring 1879. The dominant theme of first phase was pragmatism, while idealism dominated the second phase.

Pragmatism - First Phase:

The "pragmatist" first phase of the Metaphysical Club was organized by Charles Peirce (Harvard graduate and occasional lecturer), Chauncey Wright (Harvard graduate and occasional lecturer), and William James (Harvard graduate and instructor of physiology and psychology).

These three philosophers were then formulating recognizably pragmatist views. Other active members of the "Pragmatist" Metaphysical Club were two more Harvard graduates and local lawyers, Nicholas St. John Green and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who were also advocating pragmatic views of human conduct and law.

Idealist - Second Phase:

The "idealist" second phase of the Metaphysical Club was organized and led by idealists who showed no interest in pragmatism: Thomas Davidson (independent scholar), George Holmes Howison (professor of philosophy at nearby Massachusetts Institute of Technology), and James Elliot Cabot (Harvard graduate and Emerson scholar). There was some continuity between the two phases.

Although Peirce had departed in April 1875 for a year in Europe, and Wright died in September 1875, most of the original members from the first phase were available for a renewed second phase.

By January 1876 the "Idealist" Metaphysical Club (for James still was referring to a metaphysical club in a letter of 10 February 1876) was meeting regularly for discussions first on Hume, then proceeding through Kant and Hegel in succeeding years.

Besides Davidson, Howison, and Cabot, the most active members appear to be William James, Charles Carroll Everett (Harvard graduate and Dean of its Divinity School), George Herbert Palmer (Harvard graduate and professor of philosophy), and Francis Ellingwood Abbott (Harvard graduate and independent scholar).

Other occasional participants include Francis Bowen (Harvard graduate and professor of philosophy), Nicholas St. John Green, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and G. Stanley Hall (Harvard graduate and psychologist).

The Metaphysical Club was a nine-year episode within a much broader pattern of informal philosophical discussion that occurred in the Boston area from the 1850s to the 1880s.

Chauncey Wright, renowned in town for his social demeanor and remarkable intelligence, had been a central participant in various philosophy clubs and study groups dating as early as his own college years at Harvard in the early 1850s.

Wright, Peirce, James, and Green were the most active members of the Metaphysical Club from its inception in 1871.

By mid-1875 the original Metaphysical Club was no longer functioning; James was the strongest connection between the first and second phases, helping Thomas Davidson to collect the members of the "Idealist" Metaphysical Club.

Link to the Hegel Club:

James also was a link to the next philosophical club, the "Hegel Club", which began in fall 1880 in connection with George Herbert Palmer's seminar on Hegel. By winter 1881 the Hegel Club had expanded to include several from the Metaphysical Club, including James, Cabot, Everett, Howison, Palmer, Abbott, Hall, and the newcomer William Torrey Harris who had taken up residence in Concord.

This Hegel Club was in many ways a continuation of the St. Louis Hegelian Society from the late 1850s and 1860s, as Harris, Howison, Davidson, and their Hegelian students had moved east.

The Concord Summer School of Philosophy (1879-1888), under the leadership of Amos Bronson Alcott and energized by the Hegelians, soon brought other young American scholars into the orbit of the Cambridge clubs, such as John Dewey.

The "Pragmatist" Metaphysical Club met on irregular occasions, probably fortnightly during the Club's most active period of fall 1871 to winter 1872, and they usually met in the home of Charles Pierce or William James in Cambridge.

This Club met for four years until mid-1875, when their diverse career demands, extended travels to Europe, and early deaths began to disperse them. The heart of the club was the close bonds between five very unusual thinkers on the American intellectual scene.

Chauncey Wright and Charles Sanders Peirce shared the same scientific interests and outlook, having adopted a positivistic and evolutionary stance, and their common love for philosophical discussion sparked the club's beginnings. Wright's old friend and lawyer Nicholas St. John Green was glad to be included, as was Peirce's good friend William James who had also gone down the road towards empiricism and evolutionism. William James brought along his best friend, the lawyer Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who like Green was mounting a resistance to the legal formalism dominating that era. Green brought fellow lawyer Joseph Bangs Warner, and the group also invited two philosophers who had graduated with them from Harvard, Francis Ellingwood Abbott and John Fiske, who were both interested in evolution and metaphysics.

Other occasional members were Henry Ware Putnam, Francis Greenwood Peabody, and William Pepperell Montague.

Activities of the "Pragmatist" Metaphysical Club were recorded only by Peirce, William James, and William's brother Henry James, who all describe intense and productive debates on many philosophical problems.

Both Peirce and James recalled that the name of the club was the "Metaphysical" Club. Peirce suggests that the name indicated their determination to discuss deep scientific and metaphysical issues despite that era's prevailing positivism and agnosticism. A successful "Metaphysical Club" in London was also not unknown to them. Peirce later stated that the club witnessed the birth of the philosophy of pragmatism in 1871, which he elaborated (without using the term 'pragmatism' itself) in published articles in the late 1870s. His own role as the "father of pragmatism" should not obscure, in Peirce's view, the importance of Nicholas Green. Green should be recognized as pragmatism's "grandfather" because, in Peirce's words, Green had "often urged the importance of applying Alexander Bain's definition of belief as 'that upon which a man is prepared to act,' from which 'pragmatism is scarce more than a corollary'." Chauncey Wright also deserves considerable credit, for as both Peirce and James recall, it was Wright who demanded a phenomenalist and fallibilist empiricism as a vital alternative to rationalistic speculation.

The several lawyers in this club took great interest in evolution, empiricism, and Bain's pragmatic definition of belief.

They were also acquainted with James Stephen's A General View of the Criminal Law in England, which also pragmatically declared that people believe because they must act. At the time of the Metaphysical Club, Green and Holmes were primarily concerned with special problems in determining criminal states of mind and general problems of defining the nature of law in a culturally evolutionary way.

Both Green and Holmes made important advances in the theory of negligence which relied on a pragmatic approach to belief and established a "reasonable person" standard. Holmes went on to explore pragmatic definitions of law that look forward to future judicial consequences rather than to past legislative decisions.

(Source: http://www.pragmatism.org/research/me...)

message 6:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 02:48AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Discussion Ideas and Themes of the Book

While reading the book - try to take some notes about the ideas presented along the following lines:

1. Science

2. Religion

3. Philosophy

4. Psychology

5. Sociology

6. Evolution

7. Pragmatism

There are very good reasons why this book is not only called The Metaphysical Club but also after the colon: A Story of Ideas in America and the purpose of our discussion of this book is "to discuss those ideas".

Don't just read my posts - but jump right in - the more you post and the more you contribute - the more you will get out of the conversation and the read.

While reading the book - try to take some notes about the ideas presented along the following lines:

1. Science

2. Religion

3. Philosophy

4. Psychology

5. Sociology

6. Evolution

7. Pragmatism

There are very good reasons why this book is not only called The Metaphysical Club but also after the colon: A Story of Ideas in America and the purpose of our discussion of this book is "to discuss those ideas".

Don't just read my posts - but jump right in - the more you post and the more you contribute - the more you will get out of the conversation and the read.

message 7:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 10, 2013 07:14AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Discussion Ideas:

Please feel free to select any topic, person, idea, event, group or even a new vocabulary word to discuss in context with this chapter and discussion.

Remember we are discussing major ideas and events right off the bat:

Ideas:

Metaphysics

Pragmatism

The Metaphysical Club

Darwinism

Evolution

Transcendentalism (Transcendentalists)

Abolitionism (Abolitionists)

Events:

The American Civil War

People:

Louis Agassiz*

William James - did not serve in Civil War*

French Paleontologist, George Cuvier

Prussian Naturalist, Alexander von Humboldt

Josiah Nott

Abraham Lincoln

Charles William Eliot

Charles Darwin (Darwinians)*

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (Lamarckians)

Herbert Spencer (Spencerians)

Joseph Hooker

Asa Gray

Samuel Morton

Thomas Huxley

Sigmund Freud

Elizabeth Cary Agassiz

Alonzo Potter (Episcopal Bishop of Pennsylvania)

Sarah Potter

Benjamin Peirce* - a professor of astronomy and mathematics at Harvard University and perhaps the first serious research mathematician in America - father of Charles Sanders Pierce

William Dean Howells

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr (referred to in this chapter as Wendell Holmes) - did serve in Civil War*

Wilky James (Garth Wilkinson James) - brother of William James - served in Civil War*

Bob James (Robertson James) - brother of William James - also served in Civil War*

Henry James Sr. (father of William, Wilky, Bob, Henry Jr, Alice)*

Charles Sanders Pierce* - son of Benjamin Peirce - was an American philosopher, logician, mathematician, and scientist, sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism". He was educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for 30 years. Today he is appreciated largely for his contributions to logic, mathematics, philosophy, scientific methodology, and semiotics, and for his founding of pragmatism.

Sarah Hunt Mills Pierce - mother of Charles Sanders Pierce, wife of Benjamin Pierce and daughter of Elijah Hunt Mills*

Benjamin R. Curtis*

William Henry Channing*

James Freeman Clarke* - the Transcendentalist*

George Bancroft - historian*

Reverend John Peirce*

Ralph Waldo Emerson" - author of "American Scholar"

Franklin Sanborn - abolitionist*

Thomas Hill (1862 - 69) - President of Harvard*

Charles William Eliot (1869 - 1909) - President of Harvard*

A. Lawrence Lowell (1909-33) - President of Harvard - wrote thesis on quaternions*

William Rowan Hamilton - Irish mathematician - devised quaternions - a type of abstract number*

Groups

The National Academy of Sciences

Government:

The Constitution

Bill of Rights

Emancipation Proclamation

Places

Harvard*

Lawrence Scientific School

Things

None in this chapter

Vocabulary

Brahmins

Intellectual Elitist

Meritocrat

Please feel free to select any topic, person, idea, event, group or even a new vocabulary word to discuss in context with this chapter and discussion.

Remember we are discussing major ideas and events right off the bat:

Ideas:

Metaphysics

Pragmatism

The Metaphysical Club

Darwinism

Evolution

Transcendentalism (Transcendentalists)

Abolitionism (Abolitionists)

Events:

The American Civil War

People:

Louis Agassiz*

William James - did not serve in Civil War*

French Paleontologist, George Cuvier

Prussian Naturalist, Alexander von Humboldt

Josiah Nott

Abraham Lincoln

Charles William Eliot

Charles Darwin (Darwinians)*

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (Lamarckians)

Herbert Spencer (Spencerians)

Joseph Hooker

Asa Gray

Samuel Morton

Thomas Huxley

Sigmund Freud

Elizabeth Cary Agassiz

Alonzo Potter (Episcopal Bishop of Pennsylvania)

Sarah Potter

Benjamin Peirce* - a professor of astronomy and mathematics at Harvard University and perhaps the first serious research mathematician in America - father of Charles Sanders Pierce

William Dean Howells

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr (referred to in this chapter as Wendell Holmes) - did serve in Civil War*

Wilky James (Garth Wilkinson James) - brother of William James - served in Civil War*

Bob James (Robertson James) - brother of William James - also served in Civil War*

Henry James Sr. (father of William, Wilky, Bob, Henry Jr, Alice)*

Charles Sanders Pierce* - son of Benjamin Peirce - was an American philosopher, logician, mathematician, and scientist, sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism". He was educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for 30 years. Today he is appreciated largely for his contributions to logic, mathematics, philosophy, scientific methodology, and semiotics, and for his founding of pragmatism.

Sarah Hunt Mills Pierce - mother of Charles Sanders Pierce, wife of Benjamin Pierce and daughter of Elijah Hunt Mills*

Benjamin R. Curtis*

William Henry Channing*

James Freeman Clarke* - the Transcendentalist*

George Bancroft - historian*

Reverend John Peirce*

Ralph Waldo Emerson" - author of "American Scholar"

Franklin Sanborn - abolitionist*

Thomas Hill (1862 - 69) - President of Harvard*

Charles William Eliot (1869 - 1909) - President of Harvard*

A. Lawrence Lowell (1909-33) - President of Harvard - wrote thesis on quaternions*

William Rowan Hamilton - Irish mathematician - devised quaternions - a type of abstract number*

Groups

The National Academy of Sciences

Government:

The Constitution

Bill of Rights

Emancipation Proclamation

Places

Harvard*

Lawrence Scientific School

Things

None in this chapter

Vocabulary

Brahmins

Intellectual Elitist

Meritocrat

message 8:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 11:51AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Chapter Abstracts - Chapter Seven

Chapter abstracts are short descriptions of events that occur in each chapter.

They highlight major plot events and detail the important relationships and characteristics of characters and objects.

The Chapter Abstracts that I will add can be used to review what you have read, and to prepare you for what you will read.

These highlights can be a reading guide or you can use them in your discussion to discuss any of these points. I add them so these bullet points can serve as a "refresher" or a stimulus for further discussion.

Here are a few:

New Abstracts:

* Charles Sanders Pierce studied chemistry at the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard.

* Pierce's work was always an expansion of his father's work.

* Professor Pierce viewed math as the purest language of thought.

* Pierce and Agassiz lobbied Congress to form a National Academy of Science.

* Pierce had a bit of an opium addiction.

* The Civil War destroyed the whaling business.

* The estate won on account of a technicality.

* Hetty married Edward Green and moved to London.

Chapter abstracts are short descriptions of events that occur in each chapter.

They highlight major plot events and detail the important relationships and characteristics of characters and objects.

The Chapter Abstracts that I will add can be used to review what you have read, and to prepare you for what you will read.

These highlights can be a reading guide or you can use them in your discussion to discuss any of these points. I add them so these bullet points can serve as a "refresher" or a stimulus for further discussion.

Here are a few:

New Abstracts:

* Charles Sanders Pierce studied chemistry at the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard.

* Pierce's work was always an expansion of his father's work.

* Professor Pierce viewed math as the purest language of thought.

* Pierce and Agassiz lobbied Congress to form a National Academy of Science.

* Pierce had a bit of an opium addiction.

* The Civil War destroyed the whaling business.

* The estate won on account of a technicality.

* Hetty married Edward Green and moved to London.

message 9:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 12:22PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Discussion Questions for Chapter Seven - think about some of these questions while you are reading:

New Questions:

These questions that are general questions that you should be able to discuss integrating information that you read from previous chapters and this one. Also keep some of these questions in mind as you read further.

a) How did Benjamin Pierce view mathematics and its place within the scientific community?

b) What business did the Civil War destroy, though it did not interfere with the textile industry in New England

c) What was based on a combination of the theory of probability and statistics?

d) Why did many people fear the idea of mathematical laws, such as the Law of Errors?

e) What did Darwin ascertain from the study of flora in Eastern Asia and North

America? Why was it controversial?

f) What were Buckle's four influences on the human species and why were they

important to 19th Century sociology and physiology?

g) What was Oliver Wendell Holmes' contribution to the theory of pragmatism?

h) What role did Darwin, Laplace, and Lamarck play in the pragmatic theory?

i) What is the difference between Swedenborgism and Mesmerism? How do you think

they influenced William James?

New Questions:

These questions that are general questions that you should be able to discuss integrating information that you read from previous chapters and this one. Also keep some of these questions in mind as you read further.

a) How did Benjamin Pierce view mathematics and its place within the scientific community?

b) What business did the Civil War destroy, though it did not interfere with the textile industry in New England

c) What was based on a combination of the theory of probability and statistics?

d) Why did many people fear the idea of mathematical laws, such as the Law of Errors?

e) What did Darwin ascertain from the study of flora in Eastern Asia and North

America? Why was it controversial?

f) What were Buckle's four influences on the human species and why were they

important to 19th Century sociology and physiology?

g) What was Oliver Wendell Holmes' contribution to the theory of pragmatism?

h) What role did Darwin, Laplace, and Lamarck play in the pragmatic theory?

i) What is the difference between Swedenborgism and Mesmerism? How do you think

they influenced William James?

message 10:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 09:50PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Some quotes from Chapter Seven that might be the basis for discussion. Feel free to do a copy and paste and then post your commentary about each or any of them below. Be civil and respectful and discuss your ideas. Also read what your fellow readers are saying and comment on their posts if you agree or disagree and cite sources that help substantiate your point of view.

a) "There is a son of Professor Pierce, who I suspect to be a very 'smart' fellow with a great deal of character, pretty independent & violent though," William James wrote to his family soon after he entered the Lawrence Scientific School in the fall of 1861. This was Charles Sanders Pierce.

--Part 3, Chapter 7, Section 1 - The Pierces

c) "Mathematics is the science which draws necessary conclusions."

--Part 3, Chapter 7, Section 2 - The Peirces

a) "There is a son of Professor Pierce, who I suspect to be a very 'smart' fellow with a great deal of character, pretty independent & violent though," William James wrote to his family soon after he entered the Lawrence Scientific School in the fall of 1861. This was Charles Sanders Pierce.

--Part 3, Chapter 7, Section 1 - The Pierces

c) "Mathematics is the science which draws necessary conclusions."

--Part 3, Chapter 7, Section 2 - The Peirces

message 11:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 03:47AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

All, "we are open for discussion of Chapter Seven" - so that folks can begin discussion on any aspect of Chapter Seven without further delay.

At this point we can also discuss any aspect that came before in the Preface, Chapters One through Chapter Six since these pages were previously discussed in the non spoiler threads that came before.

At this point we can also discuss any aspect that came before in the Preface, Chapters One through Chapter Six since these pages were previously discussed in the non spoiler threads that came before.

Peirce was one of the most creative and versatile intellectual figures of the last two centuries. Although his genius went largely unrecognized during his lifetime, his work has exerted a considerable influence on the development of philosophy and many other disciplines. In addition to his acknowledged role as one of the pioneers of pragmatism, formal logic, and philosophical sign theory, Peirce made groundbreaking contributions to mathematics, experimental psychology, cosmology, cartography, historiography, and the emerging field of computer science. Many treasures still wait to be unearthed from the rich corpus of the published and unpublished manuscripts of this seminal American mind.

message 13:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 02:53PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

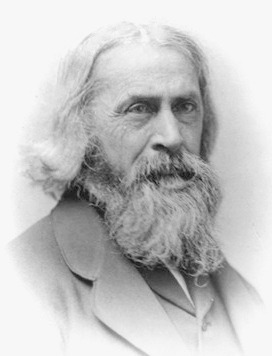

An American mathematician who taught at Harvard University for approximately 50 years. He made contributions to celestial mechanics, statistics, number theory, algebra, and the philosophy of mathematics and Charles Sanders Pierce's father. He had five children:

*James Mills Peirce (1834–1906), who also taught mathematics at Harvard and succeeded to his father's professorship,

*Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914), a famous logician, polymath and philosopher,

*Benjamin Mills Peirce (1844–1870), who worked as a mining engineer before an early death,

*Helen Huntington Peirce Ellis (1845–1923), who married William Rogers Ellis, and

* Herbert Henry Davis Peirce (1849–1916), who pursued a career in the Foreign Service.

Young Benjamin Pierce - 1857

message 14:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 01:25PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Sarah Mills Peirce (c.1865)

(Source: [Fuente: Elisabeth Walther,

Charles Sanders Peirce: Leben und Werk,

Baden-Baden: Agis Verlag, 1989, 23])

-Mother of Charles Sander Pierce - daughter of Elijah Hunt Mills who was a United States Senator of Massachusetts

message 15:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 01:43PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Louis Agassiz (seated) and Benjamin Peirce (standing and CSP's father) is pointing and indicating the global position of Harvard College.

message 16:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 01:45PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Celebrating the 150th Anniversary of the National Academy of Sciences

The painting by Albert Herter depicts President Abraham Lincoln and the signing of the Academy charter of March 3, 1863. Left to right: Benjamin Peirce, Alexander Dallas Bache, Joseph Henry, Louis Agassiz, Lincoln, Senator Henry Wilson, Charles H. Davis, and Benjamin Apthorp Gould.

message 17:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 02:02PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

The Uses of Astronomy

by Mary Crone Odekon

How do you explain the uses of astronomy? On a summer day in 1856 in Albany, New York, the answer was a two-hour manifesto by famed orator Edward Everett (remember him?).

Everett was not an astronomer. He had recently served as both President of Harvard University and US Secretary of State, and was the main oratorical heavyweight to mark the opening of a new observatory funded by heiress Blandina Bleecker Dudley.

He also delivered the Gettysburg Address -- not the succinct version of Abraham Lincoln, which was scheduled for the same day at the last minute, but the full-blown, two-hour main event.

The dedication of the Dudley Observatory, along with a new Geological Hall (inaugurated the previous day with a speech by Louis Agassiz that lasted only one hour), was part of an eight-day extravaganza of lectures linked to the tenth annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Most prominent American scientists were in attendance, joined by political leaders, donors, and thousands of local citizens.

Everett is in the middle and is the orator:

The Dudley Observatory Dedication, 1857, by Tompkins H. Matteson. More than 160 portraits are combined in this painting, including Maria Mitchell, Benjamin Peirce, Joseph Henry, Louis Agassiz, Millard Fillmore, and, of course, Edward Everett.

Credit: Albany Institute of History and Art.

High Resolution for a closer look: http://www.dudleyobservatory.org/Coll...

Also following an absolutely fascinating article about some of the men featured in this book and where they are in the painting along with other images - look at the High Resolution painting I provided for better clarity. The article also shows exactly where everybody was sitting and who they all were.

http://www.dudleyobservatory.org/Coll...

by Mary Crone Odekon

How do you explain the uses of astronomy? On a summer day in 1856 in Albany, New York, the answer was a two-hour manifesto by famed orator Edward Everett (remember him?).

Everett was not an astronomer. He had recently served as both President of Harvard University and US Secretary of State, and was the main oratorical heavyweight to mark the opening of a new observatory funded by heiress Blandina Bleecker Dudley.

He also delivered the Gettysburg Address -- not the succinct version of Abraham Lincoln, which was scheduled for the same day at the last minute, but the full-blown, two-hour main event.

The dedication of the Dudley Observatory, along with a new Geological Hall (inaugurated the previous day with a speech by Louis Agassiz that lasted only one hour), was part of an eight-day extravaganza of lectures linked to the tenth annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Most prominent American scientists were in attendance, joined by political leaders, donors, and thousands of local citizens.

Everett is in the middle and is the orator:

The Dudley Observatory Dedication, 1857, by Tompkins H. Matteson. More than 160 portraits are combined in this painting, including Maria Mitchell, Benjamin Peirce, Joseph Henry, Louis Agassiz, Millard Fillmore, and, of course, Edward Everett.

Credit: Albany Institute of History and Art.

High Resolution for a closer look: http://www.dudleyobservatory.org/Coll...

Also following an absolutely fascinating article about some of the men featured in this book and where they are in the painting along with other images - look at the High Resolution painting I provided for better clarity. The article also shows exactly where everybody was sitting and who they all were.

http://www.dudleyobservatory.org/Coll...

The great naturalist Louis Agassiz, the great mathematician and third superintendent of the Coast Survey Benjamin Peirce, and the former naval officer, hydrographic inspector and fourth superintendent of the Coast Survey Carlile P. Patterson.

Image ID: theb1202, NOAA's People Collection

message 19:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 02:22PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

The 1871 Hassler Expedition

The 1871 Hassler Expedition and Louis Agassiz

Louis Agassiz, Principal Investigator for the 1871 Hassler Expedition. (Photo: NOAA Photo Library)

In February 1871, Professor Louis Agassiz of Harvard University received a most welcome letter from the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, Benjamin Pierce. Pierce congratulated Agassiz on regaining his health and added an exciting invitation: “Now, my dear friend, I have a very serious proposition for you. I am going to send a new iron steamer round to California in the course of the summer . . . .Would you go in her, and do deep-sea dredging all the way around?”

Dredging offered the best way for scientists to sample life at the sea bottom Agassiz had experience on Coast Survey vessels in this task. In 1869, he conducted experimental work in shallow waters off the Florida Keys. But what Pierce proposed for the upcoming Hassler Expedition represented science on a grander scale. The installation of new and improved dredges on the Coast Survey vessel Hassler, Pierce explained, would allow Agassiz to explore the sea at depths greater than scientists had ever gone before. Agassiz responded with enthusiasm. “Your proposition leaves me no rest . . . . I do not think anything more likely to have a lasting influence upon the progress of science was ever devised.” Despite precarious health and advancing age, Agassiz took on the challenging task of organizing and building financial and public support for what would prove the final expedition of his career.

In 1871, Louis Agassiz was among the most famous names in American Science. Born in Switzerland in 1807, he had earned doctorates in medicine and philosophy, and before the age of 30 held a prestigious teaching post at Lyceum of Neuchatel in Switzerland. His early work in comparative anatomy focused on the fossil record of fish.

He also branched out into the study of glaciers, and is known as the father of modern glaciology.

Agassiz promoted the theory of a catastrophic “ice age” when glaciers covered the early topography and life forms. In 1848, Agassiz assumed a professorship at Harvard University where his rare gifts as teacher, public speaker, and man of letters earned him the respect of colleagues and students and wide public esteem.

In 1859 he founded Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, and four years later became a founding member of the National Academy of Sciences. By 1871, however, age and years of exhausting work, as well as the growing influence of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, had taken a heavy toll on Agassiz. In 1869 he suffered a physical breakdown that forced him into nearly two years of complete inactivity. With his physical strength returning, the Hassler Expedition seemed the perfect agent to restore his spirits and further bolster his lofty reputation.

Agassiz embraced the project with the highest hopes. In a letter preserved at Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, he described the Hassler Expedition as potentially the most significant accomplishment in ocean science since the voyages of Captain Cook.

By probing the deepest depths, he expected to collect ancient life forms analogous to those he had studied in the fossil record. Privately, he had an additional agenda. Agassiz had long been a vocal critic of Darwin and his work. But as a true scientist, he kept his mind open to new possibilities and to the evidence supplied by the natural world. The voyage, he hoped, would provide him the time to consider “the whole Darwinian theory free from all external influences and former prejudices.”

In Annual Report of the Coast Survey for 1871, published at the beginning of the voyage, Superintendent Pierce paid homage to Agassiz and the Hassler Expedition: “The departure from sight and daily intimacy of that eminent man, upon a long and, it may be, perilous voyage, leaves a void which cannot be filled. But while the exploration intended is a consummation worthy of his great life, he alone is equal to the grandeur of the enterprise.”

The 1871 Expedition

On December 4, 1871, nearly six months later than originally projected, the Hassler slipped her mooring at Boston’s Charlestown Navy Yard under the charge of Commander Philip C. Johnson, a naval officer of wide experience and excellent reputation.

Accompanying Agassiz was his wife Elizabeth, Thomas Hill—former President of Harvard, and L.F. Pourtales, a former Agassiz student in Switzerland and long time scientist with the Coast Survey.

Stormy winter weather forced the ship to lay at anchor for three days at Martha’s Vineyard. The delay provided time to properly stow equipment and transform the ship into something of a home. Elizabeth Agassiz made a particular effort to domesticate their cabin, adding a couch, a large arm chair, a portable table, and hanging a picture of their treasured house in Nahant. The presence of Commander Johnson’s wife added an additional level of feminine companionship not then associated with a Coast Survey voyage.

The expedition lasted eight long months, with the time punctuated by alternating periods of great wonder and crushing disappointment. Though at first the use of dredges was restricted to shallow and moderate depths, some of the results proved spectacular as suggested in a letter to Superintendent Pierce dated January 16, 1872:

I should have written to you from Barbadoes, but the day before we left the island was favorable for dredging, and our success in that line was so unexpectedly great, that I could not get away from the specimens, and made the most of them for study while I had the chance. We made only four hauls, in between seventy-five and one hundred and twenty fathoms. But what hauls! Enough to occupy half a dozen competent zoologists for a whole year, if the specimens could be kept fresh for that length of time.

L.F. Pourtales who prepared that official report of the expedition, also commented on the rich early harvests. He noted the great variety and volume of specimens, including “many forms heretofore unknown” as well as species that had been previously encountered at much greater depths in far distant waters. Pourtales also dutifully recorded the multiple failures of the newly developed equipment. Deepwater sounding apparatus failed repeated, the Hassler’s new steam engine manifested a variety of problems, the hull leaked, and later in the voyage all of the attempts at deepwater sampling failed when the hemp tow cables continually parted. Foul weather also made life on the Hassler miserable, especially early in the voyage. A long and narrow ship of fairly shallow draft, the Hassler rolled heavily in bad weather, especially when steaming rather than proceeding under sail. At one point in a storm off of the Caribbean the ship recorded a 42 degree roll. In an early private letter to Superintendent Pierce, Agassiz excoriated the vessel as “a complete failure.”

In truth, the brilliant Agassiz was a mercurial person whose moods shifted quickly. Much of the cruise went well. Agassiz, ever the teacher, presented lectures nearly every evening and took great delight in instructing the Hassler’s officers and crew about how to observe the natural world.

The Hassler Expedition certainly failed to meet the original high expectations of its sponsors and chief scientist. But, judged on its own merits, the expedition seems more successful. The ship explored the Magellan Strait—something that drew the praise and envy of Charles Darwin himself. They collected oceanographic and geographical data in a host of remote areas, and collected tens of thousands of specimens. Today more than 7,000 of these are catalogued at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard, while still others went to the Smithsonian Institution and other natural history collections.

Although in private correspondence, Elizabeth Agassiz made clear her relief at the conclusion of the expedition, her published narrative captures moments of magic that occurred on the clean white science vessel. While off the Patagonian coast she recorded:

The Hassler left her anchorage on this desolate shore on an evening of singular beauty. It was difficulty to tell when she was on her way, so quietly did she move through the glassy waters, over which the sun went down in burnished gold, leaving the sky without a cloud. The light of the beach fires followed her till they too faded, and on the phosphorescence of the sea attended her into the night.

Of the Magellan Straight she wrote:

…the Hassler pursued her course, past a seemingly endless panorama of mountains and forests rising into the pale regions of snow and ice, where lay glaciers in which every rift and crevasse, as well as the many cascades flowing down to join the waters beneath, could be counted as she steamed by them. . . . These were weeks of exquisite delight to Agassiz. The vessel often skirted the shore so closely that its geology could be studied from the deck.

Ultimately, the Hassler Expedition’s goal of exploring the deepest reaches of the ocean went unrealized. The time available and experimental new technologies proved inadequate.

However, vast new areas were explored and a cadre of naval officers associated with the Coast Survey learned the principals of scientific observation at the feet of a man acknowledged as of one of the great teachers in the history of American natural science. The voyage concluded in early August 1872 when the thoroughly tested and improved Hassler took up formal duties as a Coast Survey ship.

Louis Agassiz lived but another year dreaming great dreams to the very end. He died on December 14, 1873. The museum he founded lives on as does the spirit of scientific inquiry he helped to foster in the U.S. Coast Survey.

Source: NOAA - http://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/maritime/...)

The 1871 Hassler Expedition and Louis Agassiz

Louis Agassiz, Principal Investigator for the 1871 Hassler Expedition. (Photo: NOAA Photo Library)

In February 1871, Professor Louis Agassiz of Harvard University received a most welcome letter from the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, Benjamin Pierce. Pierce congratulated Agassiz on regaining his health and added an exciting invitation: “Now, my dear friend, I have a very serious proposition for you. I am going to send a new iron steamer round to California in the course of the summer . . . .Would you go in her, and do deep-sea dredging all the way around?”

Dredging offered the best way for scientists to sample life at the sea bottom Agassiz had experience on Coast Survey vessels in this task. In 1869, he conducted experimental work in shallow waters off the Florida Keys. But what Pierce proposed for the upcoming Hassler Expedition represented science on a grander scale. The installation of new and improved dredges on the Coast Survey vessel Hassler, Pierce explained, would allow Agassiz to explore the sea at depths greater than scientists had ever gone before. Agassiz responded with enthusiasm. “Your proposition leaves me no rest . . . . I do not think anything more likely to have a lasting influence upon the progress of science was ever devised.” Despite precarious health and advancing age, Agassiz took on the challenging task of organizing and building financial and public support for what would prove the final expedition of his career.

In 1871, Louis Agassiz was among the most famous names in American Science. Born in Switzerland in 1807, he had earned doctorates in medicine and philosophy, and before the age of 30 held a prestigious teaching post at Lyceum of Neuchatel in Switzerland. His early work in comparative anatomy focused on the fossil record of fish.

He also branched out into the study of glaciers, and is known as the father of modern glaciology.

Agassiz promoted the theory of a catastrophic “ice age” when glaciers covered the early topography and life forms. In 1848, Agassiz assumed a professorship at Harvard University where his rare gifts as teacher, public speaker, and man of letters earned him the respect of colleagues and students and wide public esteem.

In 1859 he founded Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, and four years later became a founding member of the National Academy of Sciences. By 1871, however, age and years of exhausting work, as well as the growing influence of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, had taken a heavy toll on Agassiz. In 1869 he suffered a physical breakdown that forced him into nearly two years of complete inactivity. With his physical strength returning, the Hassler Expedition seemed the perfect agent to restore his spirits and further bolster his lofty reputation.

Agassiz embraced the project with the highest hopes. In a letter preserved at Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, he described the Hassler Expedition as potentially the most significant accomplishment in ocean science since the voyages of Captain Cook.

By probing the deepest depths, he expected to collect ancient life forms analogous to those he had studied in the fossil record. Privately, he had an additional agenda. Agassiz had long been a vocal critic of Darwin and his work. But as a true scientist, he kept his mind open to new possibilities and to the evidence supplied by the natural world. The voyage, he hoped, would provide him the time to consider “the whole Darwinian theory free from all external influences and former prejudices.”

In Annual Report of the Coast Survey for 1871, published at the beginning of the voyage, Superintendent Pierce paid homage to Agassiz and the Hassler Expedition: “The departure from sight and daily intimacy of that eminent man, upon a long and, it may be, perilous voyage, leaves a void which cannot be filled. But while the exploration intended is a consummation worthy of his great life, he alone is equal to the grandeur of the enterprise.”

The 1871 Expedition

On December 4, 1871, nearly six months later than originally projected, the Hassler slipped her mooring at Boston’s Charlestown Navy Yard under the charge of Commander Philip C. Johnson, a naval officer of wide experience and excellent reputation.

Accompanying Agassiz was his wife Elizabeth, Thomas Hill—former President of Harvard, and L.F. Pourtales, a former Agassiz student in Switzerland and long time scientist with the Coast Survey.

Stormy winter weather forced the ship to lay at anchor for three days at Martha’s Vineyard. The delay provided time to properly stow equipment and transform the ship into something of a home. Elizabeth Agassiz made a particular effort to domesticate their cabin, adding a couch, a large arm chair, a portable table, and hanging a picture of their treasured house in Nahant. The presence of Commander Johnson’s wife added an additional level of feminine companionship not then associated with a Coast Survey voyage.

The expedition lasted eight long months, with the time punctuated by alternating periods of great wonder and crushing disappointment. Though at first the use of dredges was restricted to shallow and moderate depths, some of the results proved spectacular as suggested in a letter to Superintendent Pierce dated January 16, 1872:

I should have written to you from Barbadoes, but the day before we left the island was favorable for dredging, and our success in that line was so unexpectedly great, that I could not get away from the specimens, and made the most of them for study while I had the chance. We made only four hauls, in between seventy-five and one hundred and twenty fathoms. But what hauls! Enough to occupy half a dozen competent zoologists for a whole year, if the specimens could be kept fresh for that length of time.

L.F. Pourtales who prepared that official report of the expedition, also commented on the rich early harvests. He noted the great variety and volume of specimens, including “many forms heretofore unknown” as well as species that had been previously encountered at much greater depths in far distant waters. Pourtales also dutifully recorded the multiple failures of the newly developed equipment. Deepwater sounding apparatus failed repeated, the Hassler’s new steam engine manifested a variety of problems, the hull leaked, and later in the voyage all of the attempts at deepwater sampling failed when the hemp tow cables continually parted. Foul weather also made life on the Hassler miserable, especially early in the voyage. A long and narrow ship of fairly shallow draft, the Hassler rolled heavily in bad weather, especially when steaming rather than proceeding under sail. At one point in a storm off of the Caribbean the ship recorded a 42 degree roll. In an early private letter to Superintendent Pierce, Agassiz excoriated the vessel as “a complete failure.”

In truth, the brilliant Agassiz was a mercurial person whose moods shifted quickly. Much of the cruise went well. Agassiz, ever the teacher, presented lectures nearly every evening and took great delight in instructing the Hassler’s officers and crew about how to observe the natural world.

The Hassler Expedition certainly failed to meet the original high expectations of its sponsors and chief scientist. But, judged on its own merits, the expedition seems more successful. The ship explored the Magellan Strait—something that drew the praise and envy of Charles Darwin himself. They collected oceanographic and geographical data in a host of remote areas, and collected tens of thousands of specimens. Today more than 7,000 of these are catalogued at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard, while still others went to the Smithsonian Institution and other natural history collections.

Although in private correspondence, Elizabeth Agassiz made clear her relief at the conclusion of the expedition, her published narrative captures moments of magic that occurred on the clean white science vessel. While off the Patagonian coast she recorded:

The Hassler left her anchorage on this desolate shore on an evening of singular beauty. It was difficulty to tell when she was on her way, so quietly did she move through the glassy waters, over which the sun went down in burnished gold, leaving the sky without a cloud. The light of the beach fires followed her till they too faded, and on the phosphorescence of the sea attended her into the night.

Of the Magellan Straight she wrote:

…the Hassler pursued her course, past a seemingly endless panorama of mountains and forests rising into the pale regions of snow and ice, where lay glaciers in which every rift and crevasse, as well as the many cascades flowing down to join the waters beneath, could be counted as she steamed by them. . . . These were weeks of exquisite delight to Agassiz. The vessel often skirted the shore so closely that its geology could be studied from the deck.

Ultimately, the Hassler Expedition’s goal of exploring the deepest reaches of the ocean went unrealized. The time available and experimental new technologies proved inadequate.

However, vast new areas were explored and a cadre of naval officers associated with the Coast Survey learned the principals of scientific observation at the feet of a man acknowledged as of one of the great teachers in the history of American natural science. The voyage concluded in early August 1872 when the thoroughly tested and improved Hassler took up formal duties as a Coast Survey ship.

Louis Agassiz lived but another year dreaming great dreams to the very end. He died on December 14, 1873. The museum he founded lives on as does the spirit of scientific inquiry he helped to foster in the U.S. Coast Survey.

Source: NOAA - http://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/maritime/...)

More on the above:

Louis Agassiz, an influential Harvard professor and founder of the University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, was invited by Superintendent of the Survey Benjamin Pierce to lead a deep-sea dredging expedition to South America aboard the US Coast Survey Steamer Hassler. The Hassler circumnavigated South America and visited, among other locations, the Galapagos Islands. Agassiz investigated evidence for Darwin’s theory of evolution, collected deep-sea specimens to analyze their relation to the fossil forms of earlier eras, and observed the glaciers and moraines of the southern Andes. Count L. F. Pourtalès directed the dredging operations, Franz Steindachner oversaw specimen collection, former Harvard President Thomas Hill served as a physicist, and J. H. Blake served as artist, documenting the expedition. Elizabeth Cary Agassiz accompanied her husband on the trip and published her account of the expedition in newspapers.

Holder, Charles Frederick. Louis Agassiz :his life and work. New York : G.P. Putnam's sons, 1893.

by Charles Frederick Holder (no photo)

by Charles Frederick Holder (no photo)

Here is the above free: (complements of Harvard University Library)

http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/9...

Louis Agassiz, an influential Harvard professor and founder of the University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, was invited by Superintendent of the Survey Benjamin Pierce to lead a deep-sea dredging expedition to South America aboard the US Coast Survey Steamer Hassler. The Hassler circumnavigated South America and visited, among other locations, the Galapagos Islands. Agassiz investigated evidence for Darwin’s theory of evolution, collected deep-sea specimens to analyze their relation to the fossil forms of earlier eras, and observed the glaciers and moraines of the southern Andes. Count L. F. Pourtalès directed the dredging operations, Franz Steindachner oversaw specimen collection, former Harvard President Thomas Hill served as a physicist, and J. H. Blake served as artist, documenting the expedition. Elizabeth Cary Agassiz accompanied her husband on the trip and published her account of the expedition in newspapers.

Holder, Charles Frederick. Louis Agassiz :his life and work. New York : G.P. Putnam's sons, 1893.

by Charles Frederick Holder (no photo)

by Charles Frederick Holder (no photo)Here is the above free: (complements of Harvard University Library)

http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/9...

message 21:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 02:32PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Journal: Blake, James Henry; Hassler journal, 1871-1872. Spec. Coll. Archives sMu 326.41.1. Ernst Mayr Library, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

Here is the above free: (complements of Harvard University Library)

http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/1...

Here is the above free: (complements of Harvard University Library)

http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/1...

This is a great photo of the members of the Hassler Expedition from the Smithsonian:

And source with more and interesting information:

http://www.botany.si.edu/colls/expedi...

And source with more and interesting information:

http://www.botany.si.edu/colls/expedi...

message 24:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 02:46PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Regarding Thomas Hill: (former Harvard President)

1818-1891

Botanist on the U.S. Hassler Expedition (1871-1872) - also serving as the physician on board

Thomas Hill accompanied his friend, Louis Agassiz, on the Hassler Expedition to the South American seas. Hill never received formal training in the field of botany, but his father taught all of his children the scientific names of plants at a very early age. While on the Hassler Expedition, Hill followed the orders of Agassiz and was able to collect many algal species from the Straits of Magellan and along the coast of Brazil. Hill's lack of formal botanical training was evident on the voyage. Agassiz explained that the specimens were, "usually rather roughly prepared, different kinds being mounted indiscriminately together on course paper, without very complete data, but many samples were in fair quantity." Prior to accompanying the crew of the Hassler to South America, Hill had been very ill and was forced to resign as Harvard University President. However, Hill claims that the voyage miraculously restored his health.

Other Accomplishments:

-Received Bachelor of Arts from Harvard University (1838)

-Received Divinity Degree from the Harvard Divinity School (1845)

-Worked as a pastor in Waltham, Massachusetts (1845-1859)

-Served as President of Harvard (1862-1868)

- Accepted the ministry position at the First Church in Portland, Maine, where he would remain working for the next 18 years (1873)

1818-1891

Botanist on the U.S. Hassler Expedition (1871-1872) - also serving as the physician on board

Thomas Hill accompanied his friend, Louis Agassiz, on the Hassler Expedition to the South American seas. Hill never received formal training in the field of botany, but his father taught all of his children the scientific names of plants at a very early age. While on the Hassler Expedition, Hill followed the orders of Agassiz and was able to collect many algal species from the Straits of Magellan and along the coast of Brazil. Hill's lack of formal botanical training was evident on the voyage. Agassiz explained that the specimens were, "usually rather roughly prepared, different kinds being mounted indiscriminately together on course paper, without very complete data, but many samples were in fair quantity." Prior to accompanying the crew of the Hassler to South America, Hill had been very ill and was forced to resign as Harvard University President. However, Hill claims that the voyage miraculously restored his health.

Other Accomplishments:

-Received Bachelor of Arts from Harvard University (1838)

-Received Divinity Degree from the Harvard Divinity School (1845)

-Worked as a pastor in Waltham, Massachusetts (1845-1859)

-Served as President of Harvard (1862-1868)

- Accepted the ministry position at the First Church in Portland, Maine, where he would remain working for the next 18 years (1873)

message 27:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Aug 08, 2013 03:26PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Asa Gray

Here is a review of Darwin's Origin of Species by Asa Gray at the time: (published in The Atlantic JUL 1 1860, 12:00 PM ET) - very interesting)

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/a...

This is from Wired - Interesting article:

How Charles Darwin Seduced Asa Gray

BY DAVID DOBBS - 04.28.1112:10 PM

The history of science lives. Today it came to life over at the Atlantic, which just posted a key document in the fight over Darwin’s theory of evolution: a review of Darwin’s Origin of Species by Harvard botanist Asa Gray, which originally ran in the Atlantic in July 1860.

Gray’s review provided a pivotal victory for Darwin: It gave his highly controversial theory, which he had published the previous December, the support of one of America’s most respected scientists. Gray proved a key and effective advocate for Darwin in the U.S., especially during 1860, when he thrice defeated in debate America’s most prominent scientist, the zoologist Louis Agassiz.

Agassiz, a creationist, resisted Darwin’s theory ferociously. He did so both because he disagreed and because he himself had become the country’s most famous scientist by beautifully articulating a vision of species as works of God. He had built his career on this vision. He knew he had to defeat Darwin or go down himself.

He lost, however, and the defeat started with the 1860 debates with Gray. Gray, however, unlike the UK’s Thomas Huxley, aka “Darwin’s bulldog,” was not a pugnacious sort — not one to argue with archbishops. Rather he was a devout Christian who, as late as 1858, believed in pretty much the sort of static, God’s-order vision of species that Louis Agassiz promoted. But in a remarkable series of inquiries in 1858 and 1859, Darwin led Gray to his view.

The passage below tells how he did so. It’s from Chapter 5 of my book Reef Madness: Charles Darwin, Alexander Agassiz, and the Meaning of Coral — a book about another long argument in the 19th century, that over the origin of coral reefs, which paralleled and in many cases inverted the argument over the origin of species. In the small story of Gray’s seduction, as in the two big sweeping stories of which it is part, ideas travel long arcs and sometimes strike, smack in the back of the head, the people who let them go.

__

After Darwin’s book came out in late 1859, Louis mounted an all-or-nothing attack on it. He waged his war on two fronts — one among peers, another in the popular press and lecture circuit. Louis actually won a draw on the popular front, at least in the United States, for most Americans chose the straddle mentioned earlier. Even 150 years later, over half of Americans continued to believe that God either created most species as is or somehow directs evolution.

This happy stance ignores, of course, the philosophical implications that haunted Darwin, and it overlooks the underlying disagreement about how one should seek answers. Louis’s idealist logic and Darwin’s empirical method clashed as violently as did their creationist and mechanistic conclusions. For scientists of the era — a time when science was self-consciously moving toward an empirical stance — this argument about method mattered as much as whether we arose from God or monkey. It was this methodological debate that Louis so decisively lost.

A debate, of course, requires an opponent, and even Darwin couldn’t argue effectively from across the Atlantic. He didn’t much like arguing anyway, preferring to sway through his writing while friends did the knifework. In England, Thomas Huxley, self-anointed as “Darwin’s bulldog,” did the bloodiest of it. Huxley won an early and instantly famous debate over Darwinism even though his opponent, the former Oxford debater Archbishop Wilberforce, fired the most memorable salvo of the entire long war: In June 1860, before an excited crowd at Oxford, Wilberforce wrapped up his creationist attack on Origin by asking Huxley whether it was through his grandfather or grandmother that he descended from a monkey. The agnostic Huxley, murmuring to a friend that “The Lord hath delivered him unto my hands,” rose, rubbing those hands together, and dismantled the archbishop’s argument. He finished by declaring that if given the choice between kinship to a smelly ape or to a man willing to use his intelligence and privilege to twist the truth, he would choose the ape. The packed hall erupted in shouting; one woman reportedly fainted.

Darwin’s American advocate was less flashy. The Harvard botanist Asa Gray, it will be recalled, was among those who warmly welcomed Louis Agassiz to America. Far less outgoing than Louis (he preferred doing taxonomy to lecturing about it), Gray, at Harvard since 1842, had won eminence through solid work, lucid writing, and judicious promotion of rigorous science. As charmed as most by Louis’s high spirits and dazzling talk, he had accompanied him on his first trip to Philadelphia and Washington in 1846 to introduce him to the country’s scientific establishment. He was thrilled when Agassiz joined the Harvard faculty, inviting him to dinner several times to meet new colleagues. Louis would often stay late at these dinners as he and Gray talked deep into the night. Their rapport seemed to promise long allegiance.

But the two differed on numerous points over the next 15 years. In the mid-1850s, at a time when the issues of race and slavery repeatedly took the United States to the brink of civil war, Gray was disgusted to see Louis offer scientific views in support of racist arguments. Louis held that different human races, like similar but different animal species, had been created separately — and none too equally. This theory conflicted with both Gray’s growing scientific belief in species descent and his Christian belief in humankind’s common origin.