The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

The Raj Quartet

HISTORY OF SOUTHERN ASIA

>

THE RAJ QUARTET SERIES - INTRODUCTION ~ (Spoiler Thread)

This is a review of the Quartet from A Library Blog from Moore Memorial Public Library in Texas City, Texas:

Having finally finished all four of the books making up the Quartet, I have a new understanding of Paul Scott’s final take on the British dominion of India. The action of the four books takes place between 1942 and 1947. In 1942 the Indian Congress first issued a motion for the British to leave, and in 1947 the British did just that. Scott tells his story through interweaving personal accounts, diaries, letters and reports of people playing major or minor roles in India –British commanders and their families, proprietors of shops, factories and newspapers, Indian soldiers in the British army, spies, police and ambassadors – the list goes on. Scott knew his India, having been posted to India for three years as a supply officer, and was able to visit India again in 1964, before writing the Raj Quartet. He wrote the four books over a roughly ten year period, with the last published in 1975, just three years before his death at the age of 57.

There is direct action within the accounts as well. Scott’s technique of providing us with documents written by characters in the story can make for slow reading, but faithful attention to details and nuance is amply rewarded by the outcome of a story with depth and resonance. Some critics have complained that they feel lectured to at times with Scott’s detailed elucidation of history. The characters are fictitious, of course, but they exist on a canvas of real events. Indian national figures like Gandhi, Nehru and Pakistan’s Jinnah are seen in the background, through the characters’ perceptions.

The characters themselves are alive and multi-dimensional. Unlike E.M. Forster’s novel “A Passage to India”, the British who are in India are presented sympathetically, even when their presumptions about India and Indians are derogatory and unfeeling. Somehow you see how they got there – most particularly in the character of Ronald Merrick, a villain who sees the bottom line of race that is Empire, and uses this perception for self-advancement. But was the British Empire – the Raj, as it was called in India, really based on racism? There are British commanders who inspire loyalty in their Indian recruits, with their Memsahib British wives going out to visit the Indian soldiers’ families in a gesture of underlying solidarity. There are Indian servants who have lived with an English family their whole lives, and have a closeness that is genuine. Does the closeness, where it exists, come simply from the spirituality and depth of the Indian?

Throughout the books Scott shows how the Indian landscape pervades everywhere - the vastness of the plains, the wildness of the hill country. It is this landscape that the children of Britain came to, and took it as their own, so that hereafter English vistas seemed too constricted, not answering to their increased appetite for scope and richness in their daily lives. Reading the Raj Quartet gave me a picture of how the Empire grasped India, tried to form it, and then let go – so that the disparity of India’s peoples – particularly the Hindus and the Muslims – could only express itself in disarray, with helpless violence. That violence and enmity continues today, in the legacy of Pakistan, an exterior solution to an interior dilemma.

(Source: http://moorebrarians.blogspot.com/201...)

Having finally finished all four of the books making up the Quartet, I have a new understanding of Paul Scott’s final take on the British dominion of India. The action of the four books takes place between 1942 and 1947. In 1942 the Indian Congress first issued a motion for the British to leave, and in 1947 the British did just that. Scott tells his story through interweaving personal accounts, diaries, letters and reports of people playing major or minor roles in India –British commanders and their families, proprietors of shops, factories and newspapers, Indian soldiers in the British army, spies, police and ambassadors – the list goes on. Scott knew his India, having been posted to India for three years as a supply officer, and was able to visit India again in 1964, before writing the Raj Quartet. He wrote the four books over a roughly ten year period, with the last published in 1975, just three years before his death at the age of 57.

There is direct action within the accounts as well. Scott’s technique of providing us with documents written by characters in the story can make for slow reading, but faithful attention to details and nuance is amply rewarded by the outcome of a story with depth and resonance. Some critics have complained that they feel lectured to at times with Scott’s detailed elucidation of history. The characters are fictitious, of course, but they exist on a canvas of real events. Indian national figures like Gandhi, Nehru and Pakistan’s Jinnah are seen in the background, through the characters’ perceptions.

The characters themselves are alive and multi-dimensional. Unlike E.M. Forster’s novel “A Passage to India”, the British who are in India are presented sympathetically, even when their presumptions about India and Indians are derogatory and unfeeling. Somehow you see how they got there – most particularly in the character of Ronald Merrick, a villain who sees the bottom line of race that is Empire, and uses this perception for self-advancement. But was the British Empire – the Raj, as it was called in India, really based on racism? There are British commanders who inspire loyalty in their Indian recruits, with their Memsahib British wives going out to visit the Indian soldiers’ families in a gesture of underlying solidarity. There are Indian servants who have lived with an English family their whole lives, and have a closeness that is genuine. Does the closeness, where it exists, come simply from the spirituality and depth of the Indian?

Throughout the books Scott shows how the Indian landscape pervades everywhere - the vastness of the plains, the wildness of the hill country. It is this landscape that the children of Britain came to, and took it as their own, so that hereafter English vistas seemed too constricted, not answering to their increased appetite for scope and richness in their daily lives. Reading the Raj Quartet gave me a picture of how the Empire grasped India, tried to form it, and then let go – so that the disparity of India’s peoples – particularly the Hindus and the Muslims – could only express itself in disarray, with helpless violence. That violence and enmity continues today, in the legacy of Pakistan, an exterior solution to an interior dilemma.

(Source: http://moorebrarians.blogspot.com/201...)

Rave Reviews for Behind Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet: A Life in Letters by Times Literary Supplement and Transnational Literature

Posted on June 21, 2012 by Cambria Press

(Source: http://cambriapressacademicpublisher....)

These books describe Paul Scott's writing of the Quartet:

Cambria Press congratulates Professor Janis Haswell on the recent rave review by Transnational Literature of her two-volume book, Behind Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet: A Life in Letters. The first volume delves into the early years 1940–1965, and the second volume examines the years 1966–1978.

The book review journal is a testament to how Professor’s Haswell’s painstaking work is a major contribution to the literary field. It states that “the letters continually illuminate details of his work as a novelist, his self-conscious and perceptive evaluations of his and others’ work, and the experiences that shaped his fiction … the letters offer us a valuable biographical window onto Scott’s work methods and ideas, as well as the everyday life of a postwar English writer. Those interested in Scott, and in postwar fiction more broadly, will find much to appreciate in Janis Haswell’s admirably annotated volumes.”

The Times Literary Supplement also praises the book for being “an important addition to the growing body of scholarship about a writer who lived for his art.”

Note: Books not on Goodreads - will research further and add citations - found it under the call number. There are two volumes to this work.

by

by

Paul Scott

Paul Scott

by

by

Paul Scott

Paul Scott

Posted on June 21, 2012 by Cambria Press

(Source: http://cambriapressacademicpublisher....)

These books describe Paul Scott's writing of the Quartet:

Cambria Press congratulates Professor Janis Haswell on the recent rave review by Transnational Literature of her two-volume book, Behind Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet: A Life in Letters. The first volume delves into the early years 1940–1965, and the second volume examines the years 1966–1978.

The book review journal is a testament to how Professor’s Haswell’s painstaking work is a major contribution to the literary field. It states that “the letters continually illuminate details of his work as a novelist, his self-conscious and perceptive evaluations of his and others’ work, and the experiences that shaped his fiction … the letters offer us a valuable biographical window onto Scott’s work methods and ideas, as well as the everyday life of a postwar English writer. Those interested in Scott, and in postwar fiction more broadly, will find much to appreciate in Janis Haswell’s admirably annotated volumes.”

The Times Literary Supplement also praises the book for being “an important addition to the growing body of scholarship about a writer who lived for his art.”

Note: Books not on Goodreads - will research further and add citations - found it under the call number. There are two volumes to this work.

by

by

Paul Scott

Paul Scott by

by

Paul Scott

Paul Scott

From Stanford University - Source: http://bookhaven.stanford.edu/tag/jan...

He got it right: The letters of Paul Scott, the man behind Jewel in the Crown

Tuesday, July 19th, 2011

Eliel Saarinen's Cranbrook

I met British author Paul Scott briefly, during a scholarship weekend decades ago at the Cranbrook Academy of Arts and Institute of Sciences – with its beautiful gardens and buildings by architect Eliel Saarinen, coincidentally, a mile or so down the street from my family home. A writer’s scholarship was heady stuff back then. Poetry and prose were separated like goats and sheep: the poetry folks were shuffled off for meetings with Galway Kinnell; the fiction people were sent off with Paul Scott.

Debonair and rumpled Galway was the charmer of the two – he charmed me, anyway, over biscuits and tea. Paul Scott seemed under the weather – an old tropical disease, was the rumor. To my eye, it seemed to have a lot to do with alcohol.

At any rate, in our small prose sessions, Paul seemed displeased with the lot of us. After dismissing one piece of writing after another, he came to mine – a short satire of Russian writers (take that, Elif Batuman!). “This is quite different,” he said, lifting his eyes to mine. “I can see what you must have been like as a child. You were quite brave, quite courageous.” I did not correct him, but met his gaze. Actually, he called it wrong. I had been quite timid and withdrawn.

The Charmer

The Cranbrook week was over all too soon. But I didn’t forget him, and planned to meet him when I was a young intern at Vogue in London (yes, it was exactly like The Devil Wears Prada, and I felt very much like the Anne Hathaway character, except for the looks). So I was surprised to read in the news of his death, a few months after my arrival, of colon cancer.

I wonder now if that’s part of why he was “under the weather” before, in the lush green of a Michigan summer.

His newly published Staying On, a coda to his Raj Quartet, hadn’t grabbed me; it won a Booker Prize after his death. Like everyone else, I became a devoted fan of the Jewel in the Crown series years later – but by that time I’d had my own experiences in India.

Now, in 2011, two volumes of his letters have been published: Behind Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet: A Life in Letters, edited by Janis Haswell. The volumes are reviewed in the Times Literary Supplement here. An excerpt:

For much of his life, Paul Scott was the epitome of the struggling novelist. Dogged by self-doubt and money worries, tormented by writer’s block or inching forward painfully with a many-stranded narrative, his health and family problems exacerbated by a sedentary and often solitary lifestyle, he suffered for his art on a daily basis. Even success had its drawbacks. In a letter recording a lucrative paperback deal, he inveighs against “this coming and going and signing on the dotted line and being wooed by some crap publisher you don’t want to go to . . . all this is now a bit nasty, this is what I used to have ambitions for; and worked myself up into a tizzy just to meet this great man or this useful woman”. His frustration boils over on to the page. But the underlying reason for it is clear: “I’d almost give my right arm just to be left in peace to get on with The Birds of Paradise”. Some people really have no choice but to write, and Scott was one of them. As he himself explains, “The bloody trouble is we are only alive when we’re half dead trying to get a paragraph right”.

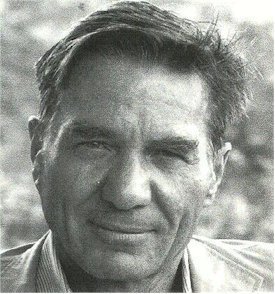

Paul Scott

My own mega-volume of Scott’s Quartet is marked lightly with pencil in the margins. “For me, the British Raj is an extended metaphor [and] I don’t think a writer chooses his metaphors. They choose him,” Scott had said.

His biographer Hilary Spurling wrote:

Thumbing through reminds me of why I loved his vision as large as the empire, his empathy, his humanity. And when he got it right, he got it right:

Jewel in the Crown: Art Malik as Hari Kumar, Tim Pigott-Smith as Ronald Merrick

He got it right: The letters of Paul Scott, the man behind Jewel in the Crown

Tuesday, July 19th, 2011

Eliel Saarinen's Cranbrook

I met British author Paul Scott briefly, during a scholarship weekend decades ago at the Cranbrook Academy of Arts and Institute of Sciences – with its beautiful gardens and buildings by architect Eliel Saarinen, coincidentally, a mile or so down the street from my family home. A writer’s scholarship was heady stuff back then. Poetry and prose were separated like goats and sheep: the poetry folks were shuffled off for meetings with Galway Kinnell; the fiction people were sent off with Paul Scott.

Debonair and rumpled Galway was the charmer of the two – he charmed me, anyway, over biscuits and tea. Paul Scott seemed under the weather – an old tropical disease, was the rumor. To my eye, it seemed to have a lot to do with alcohol.

At any rate, in our small prose sessions, Paul seemed displeased with the lot of us. After dismissing one piece of writing after another, he came to mine – a short satire of Russian writers (take that, Elif Batuman!). “This is quite different,” he said, lifting his eyes to mine. “I can see what you must have been like as a child. You were quite brave, quite courageous.” I did not correct him, but met his gaze. Actually, he called it wrong. I had been quite timid and withdrawn.

The Charmer

The Cranbrook week was over all too soon. But I didn’t forget him, and planned to meet him when I was a young intern at Vogue in London (yes, it was exactly like The Devil Wears Prada, and I felt very much like the Anne Hathaway character, except for the looks). So I was surprised to read in the news of his death, a few months after my arrival, of colon cancer.

I wonder now if that’s part of why he was “under the weather” before, in the lush green of a Michigan summer.

His newly published Staying On, a coda to his Raj Quartet, hadn’t grabbed me; it won a Booker Prize after his death. Like everyone else, I became a devoted fan of the Jewel in the Crown series years later – but by that time I’d had my own experiences in India.

Now, in 2011, two volumes of his letters have been published: Behind Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet: A Life in Letters, edited by Janis Haswell. The volumes are reviewed in the Times Literary Supplement here. An excerpt:

For much of his life, Paul Scott was the epitome of the struggling novelist. Dogged by self-doubt and money worries, tormented by writer’s block or inching forward painfully with a many-stranded narrative, his health and family problems exacerbated by a sedentary and often solitary lifestyle, he suffered for his art on a daily basis. Even success had its drawbacks. In a letter recording a lucrative paperback deal, he inveighs against “this coming and going and signing on the dotted line and being wooed by some crap publisher you don’t want to go to . . . all this is now a bit nasty, this is what I used to have ambitions for; and worked myself up into a tizzy just to meet this great man or this useful woman”. His frustration boils over on to the page. But the underlying reason for it is clear: “I’d almost give my right arm just to be left in peace to get on with The Birds of Paradise”. Some people really have no choice but to write, and Scott was one of them. As he himself explains, “The bloody trouble is we are only alive when we’re half dead trying to get a paragraph right”.

Paul Scott

My own mega-volume of Scott’s Quartet is marked lightly with pencil in the margins. “For me, the British Raj is an extended metaphor [and] I don’t think a writer chooses his metaphors. They choose him,” Scott had said.

His biographer Hilary Spurling wrote:

“Probably only an outsider could have commanded the long, lucid perspectives he brought to bear on the end of the British raj, exploring with passionate, concentrated attention a subject still generally treated as taboo, or fit only for historical romance and adventure stories. However Scott saw things other people would sooner not see, and he looked too close for comfort. His was a bleak, stern, prophetic vision and, like E.M. Forster‘s, it has come to seem steadily more accurate with time.”

Thumbing through reminds me of why I loved his vision as large as the empire, his empathy, his humanity. And when he got it right, he got it right:

"It will end, she told herself, in total and unforgiveable disaster; that is the situation. As she continued to look down upon the tableau of Rowan, Gopal and Kumar – and the clerk who no re-entered, presumably as a result of the ring of a bell that Rowan had pressed – she felt that she was being vouchsafed a vision of the future they were all headed for. At its heart was the rumbling sound of martial music. It was a vision because the likeness of it would happen. In her own time it would happen. … The reality of the actual deed would be a monument to all that had been thought for the best. ‘But it isn’t the best we should remember,’ she said, and shocked herself by speaking aloud, and clutched the folds and mother-of-pearl buttons in that habitual gesture. We must remember the worst because the worst is the lives we lead, the best is only our history, and between our history and our lives there is this vast dark plain where the rapt and patient shepherds drive their invisible flocks in expectation of God’s forgiveness.

Jewel in the Crown: Art Malik as Hari Kumar, Tim Pigott-Smith as Ronald Merrick

Paul Scott: A Life of the Author of the Raj Quartet

by

by

Hilary Spurling

Hilary Spurling

Synopsis: - from Publisher's Weekly - their review

In this fine biography Spurling is equally at home in the literary, social and psychological worlds of a talented novelist who died of cancer in 1978 after winning Britain's prestigious Booker literary award but several years before TV's The Jewel in the Crown , based on the four novels in his Raj Quartet, brought him world renown.

Spurling, author of a biography of Ivy Compton Burnett, examines in scrupulous, sympathetic detail Scott's difficult early years; his several stays in India which inspired him to explore with relentless honesty the declining years of the British Raj; the repressed homosexuality that put a disastrous strain on his marriage; and his stint as an unorthodox but extremely popular university teacher. Not a historical novelist in the accepted sense (``One is not ruled by the past . . . one simply is it,'' he insisted), Scott was fascinated by people. As Spurling subtly shows, Hari Kumar, the psychologically displaced Indian, and Ronald Merrick, the homosexual army officer who torments him, probably Scott's most memorable characters, reflect aspects of his own personality

Review of Book from The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis: - Kathleen Erickson - Vice President

Imperialist empires have been rising and falling since the beginning of civilization. Perhaps what will distinguish the fallen empires of the 20th century is that it seems unlikely they—or others in their place—will rise again. It is as if the 20th century has seen the end not only of its historical share of fallen empires, but the end of the very concept of empire and imperialism.

How does this happen? How does a political structure that has endured centuries and been the modus operandi of nations as culturally diverse as Imperial Rome and Victorian England and even (although Lenin would certainly deny it) the Communist Bloc, cease to be?

As vast as the causes of such a phenomenon must be and as extraordinary as the end of imperialism is in its impact on governments, military organization and national economies—its most poignant effect is at the level of day-to-day human experience. And to understand the impact of the end of imperialism, from the individual perspective, one could do no better than to read Paul Scott's Raj Quartet: four novels that tell the story of the end of British rule in India.

But to read the Raj Quartet—published (1966-1975) just a generation after the fall of the British Raj—is to wonder at Paul Scott's vision. Hilary Spurling's Paul Scott: A Life of the Author of the Raj Quartet answers many questions Raj readers are likely to have regarding Scott.

Paul Scott was born in 1920, the son of a mother and father whose positions within the English class system were tenuous, at best. Paul's father was a commercial artist, descended from a line only marginally secure within a society which, as Spurling notes, could cast out a family guilty of no greater an infraction than taking meals in the kitchen. His mother's antecedents were even less secure; she knew real hardship as a child, and her marriage represented a step up the social ladder.

The worldwide depression of the 1930s weakened the rung of the ladder to which young Paul's family clung, and when his father's business in suburban London provided too little income to support Paul's continued education, he took work as a junior clerk in an accountancy firm. This was a bitter experience for Scott; he had aspired from an early age to a future in the arts, and this Dickensian turn of events darkened his world view in a manner that was to stay with him—and influence his writing—for the rest of his life. It also established another life-long pattern: the tension between being a breadwinner and an artist.

History intervened in Paul's life again with the advent of the Second World War. Most significantly, for Scott and his readers, the war took him to India, where Scott observed "...a society so hidebound and ingrown that it treated the imminent collapse of Western civilization as an unwarranted intrusion on its own comfort."

Particularly, we understand from Spurling's biography how Scott came to see what the end of empire and imperialism means, in human terms, to both the rulers and the ruled. Spurling relates an experience Scott had at an airport in Malaya, where he met an elderly Englishwoman who had been in a Japanese prison camp. Scott offered to carry her bag onto their plane, and Spurling quotes Scott's retelling of the woman's refusal: "No, no. It's because people like me always had our bags carried for us that what happened to us happened."

What isn't clear from Spurling's biography is how Scott rose above his upbringing and family precedents to become the post-imperialist man who wrote the Raj Quartet. To what forces did Scott owe his character?

The facts Spurling presents about Scott's background suggest that Scott's character owed nothing to time, place or birth. Spurling does, in her analysis of the complexity of Scott's character, provide a clue as to the development of his conscience. It would seem that the psychological process by which negative forces—in Scott's case guilt and fear—fossilize into something hard and fine, was very much the source of Paul Scott's personal virtues. Spurling lays Scott's guilt at the door of his [ultimately] suppressed homosexuality, while his fear flows from the financial insecurity of his youth that continued throughout his adult life. In turn, his humility about his own shortcomings caused him to be tolerant where others were concerned. He became a true aristocrat, judging individual merit on such species-sustaining and culture-indifferent qualities as intelligence, wit, compassion and talent.

Scott's ability to be compassionate at the individual level—to see the personal tragedy of a "memsahib" reduced to carrying her own luggage late in life—at the same time he could personally despise and professionally savage the class system that produced such a woman—was critical to the depth of characterization he achieves in the Raj Quartet. Only an author who knew from personal experience how mixed is any one individual's goodness or evil, could create heroes as human and villains as capable of provoking sympathy as are the heroes and villains of the Raj Quartet. That Scott embodied essential elements of himself in the two principal male heroes in the Raj as well as in the Quartet's principal villain (perhaps the most finely drawn villain in English literature), is a monumental tribute to Scott's fundamental understanding and love of the human condition.

Scott's death in 1978 came at a time when both his personal and professional lives were achieving something almost like equilibrium. He died of cirrhosis of the liver and colon cancer, not surprising when one considers that by Scott's own reckoning his normal daily consumption of alcohol and cigarettes was a quart of vodka and 60 to 80 cigarettes.

Spurling closes her life of Paul Scott by quoting Scott in saying, "The major problem...in fact and fiction, past and present, was the actual business...of living with other people." It was Scott's natural ability to approach a resolution of the problems of living with other people without carrying a jot about their race, gender, or class that makes him a natural citizen in the post-imperial age.

by

by

Hilary Spurling

Hilary SpurlingSynopsis: - from Publisher's Weekly - their review

In this fine biography Spurling is equally at home in the literary, social and psychological worlds of a talented novelist who died of cancer in 1978 after winning Britain's prestigious Booker literary award but several years before TV's The Jewel in the Crown , based on the four novels in his Raj Quartet, brought him world renown.

Spurling, author of a biography of Ivy Compton Burnett, examines in scrupulous, sympathetic detail Scott's difficult early years; his several stays in India which inspired him to explore with relentless honesty the declining years of the British Raj; the repressed homosexuality that put a disastrous strain on his marriage; and his stint as an unorthodox but extremely popular university teacher. Not a historical novelist in the accepted sense (``One is not ruled by the past . . . one simply is it,'' he insisted), Scott was fascinated by people. As Spurling subtly shows, Hari Kumar, the psychologically displaced Indian, and Ronald Merrick, the homosexual army officer who torments him, probably Scott's most memorable characters, reflect aspects of his own personality

Review of Book from The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis: - Kathleen Erickson - Vice President

Imperialist empires have been rising and falling since the beginning of civilization. Perhaps what will distinguish the fallen empires of the 20th century is that it seems unlikely they—or others in their place—will rise again. It is as if the 20th century has seen the end not only of its historical share of fallen empires, but the end of the very concept of empire and imperialism.

How does this happen? How does a political structure that has endured centuries and been the modus operandi of nations as culturally diverse as Imperial Rome and Victorian England and even (although Lenin would certainly deny it) the Communist Bloc, cease to be?

As vast as the causes of such a phenomenon must be and as extraordinary as the end of imperialism is in its impact on governments, military organization and national economies—its most poignant effect is at the level of day-to-day human experience. And to understand the impact of the end of imperialism, from the individual perspective, one could do no better than to read Paul Scott's Raj Quartet: four novels that tell the story of the end of British rule in India.

But to read the Raj Quartet—published (1966-1975) just a generation after the fall of the British Raj—is to wonder at Paul Scott's vision. Hilary Spurling's Paul Scott: A Life of the Author of the Raj Quartet answers many questions Raj readers are likely to have regarding Scott.

Paul Scott was born in 1920, the son of a mother and father whose positions within the English class system were tenuous, at best. Paul's father was a commercial artist, descended from a line only marginally secure within a society which, as Spurling notes, could cast out a family guilty of no greater an infraction than taking meals in the kitchen. His mother's antecedents were even less secure; she knew real hardship as a child, and her marriage represented a step up the social ladder.

The worldwide depression of the 1930s weakened the rung of the ladder to which young Paul's family clung, and when his father's business in suburban London provided too little income to support Paul's continued education, he took work as a junior clerk in an accountancy firm. This was a bitter experience for Scott; he had aspired from an early age to a future in the arts, and this Dickensian turn of events darkened his world view in a manner that was to stay with him—and influence his writing—for the rest of his life. It also established another life-long pattern: the tension between being a breadwinner and an artist.

History intervened in Paul's life again with the advent of the Second World War. Most significantly, for Scott and his readers, the war took him to India, where Scott observed "...a society so hidebound and ingrown that it treated the imminent collapse of Western civilization as an unwarranted intrusion on its own comfort."

Particularly, we understand from Spurling's biography how Scott came to see what the end of empire and imperialism means, in human terms, to both the rulers and the ruled. Spurling relates an experience Scott had at an airport in Malaya, where he met an elderly Englishwoman who had been in a Japanese prison camp. Scott offered to carry her bag onto their plane, and Spurling quotes Scott's retelling of the woman's refusal: "No, no. It's because people like me always had our bags carried for us that what happened to us happened."

What isn't clear from Spurling's biography is how Scott rose above his upbringing and family precedents to become the post-imperialist man who wrote the Raj Quartet. To what forces did Scott owe his character?

The facts Spurling presents about Scott's background suggest that Scott's character owed nothing to time, place or birth. Spurling does, in her analysis of the complexity of Scott's character, provide a clue as to the development of his conscience. It would seem that the psychological process by which negative forces—in Scott's case guilt and fear—fossilize into something hard and fine, was very much the source of Paul Scott's personal virtues. Spurling lays Scott's guilt at the door of his [ultimately] suppressed homosexuality, while his fear flows from the financial insecurity of his youth that continued throughout his adult life. In turn, his humility about his own shortcomings caused him to be tolerant where others were concerned. He became a true aristocrat, judging individual merit on such species-sustaining and culture-indifferent qualities as intelligence, wit, compassion and talent.

Scott's ability to be compassionate at the individual level—to see the personal tragedy of a "memsahib" reduced to carrying her own luggage late in life—at the same time he could personally despise and professionally savage the class system that produced such a woman—was critical to the depth of characterization he achieves in the Raj Quartet. Only an author who knew from personal experience how mixed is any one individual's goodness or evil, could create heroes as human and villains as capable of provoking sympathy as are the heroes and villains of the Raj Quartet. That Scott embodied essential elements of himself in the two principal male heroes in the Raj as well as in the Quartet's principal villain (perhaps the most finely drawn villain in English literature), is a monumental tribute to Scott's fundamental understanding and love of the human condition.

Scott's death in 1978 came at a time when both his personal and professional lives were achieving something almost like equilibrium. He died of cirrhosis of the liver and colon cancer, not surprising when one considers that by Scott's own reckoning his normal daily consumption of alcohol and cigarettes was a quart of vodka and 60 to 80 cigarettes.

Spurling closes her life of Paul Scott by quoting Scott in saying, "The major problem...in fact and fiction, past and present, was the actual business...of living with other people." It was Scott's natural ability to approach a resolution of the problems of living with other people without carrying a jot about their race, gender, or class that makes him a natural citizen in the post-imperial age.

From the Atlantic - http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/a...

Victoria’s Secret

Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet reveals how sex doomed the British Empire.

Victoria’s Secret

Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet reveals how sex doomed the British Empire.

From a Blog - Paul Scott’s The Raj Quartet: vast panoramic political cycle, yet mostly narrated by heroines

September 7, 2009 by ellenandjim

(Source: http://ellenandjim.wordpress.com/2009...)

http://ellenandjim.wordpress.com/2009...

September 7, 2009 by ellenandjim

(Source: http://ellenandjim.wordpress.com/2009...)

http://ellenandjim.wordpress.com/2009...

The Raj Quartet by Paul Scott - From Urban Book Review: http://urbanbookreview.blogspot.com/2...

Four impressive books make the Raj quartet, "The Jewel in the Crown" (480pgs) "The Day of the Scorpion" (495 pgs) "The Towers of Silence" (397pgs) "A Division of the Spoils" (720pgs). A lot to read - over 2000 pages - but of such quality, such perfectly interlocking storylines spread over the four books . Characters and situations in the first book carry through to the last in a beautifully natural way. The huge cast of characters become familiar over the four books so as a reader you get so involved, so engrossed that you really begin to care about these people. Such superb intricate detail is described throughout the novels that the beauty and magnificence of India is brought to life. Set in India during the British Empire - The Raj - it spans a time from the early 30's throughout the war to Independence of India and the partition in to Pakistan and India. It’s a series of events told from several different perspectives both British and Indian. We get intricate backgrounds of the many characters in scrumptious detail then intricate plotting that intrigues and entertains. It is both warm and heartrending yet through provoking as it explores the many facets of the Indian Empire ruled by really only a handful of British civilians and soldiers. We are taken into their lives and we see all sides to them as they try to react to events and history unfolding around them.

Each of the four novels could be read as a stand-alone novel but to really appreciate what the author Paul Scott (who died in 1978) was trying to achieve a back-to-back read of all four is necessary. I was lucky having spent many months finding these novels in matching covers then being able to read them as a holiday read all together. We are taken in the storyline through a series of key events small and large that shapes the lives of those concerned against a backdrop of war and forthcoming Indian independence. Forbidden relationships between a white British woman of the ruling Raj class and an educated Indian who has been to the best British boarding school have a tragic outcome and set in turn a series events that follow key characters around India till independence. Key events and characters dip in and out of the novels - someone in the first novel may reappear in the third yet it all happens seamlessly and not at all contrived. The massive groundwork done in the first novel is carried through to fruition in the final three works. The first novel (The Jewel in the Crown) is told a lot of the time in flashback giving the tragic events that unfold a view from several different perspectives. This admittedly slows the pace somewhat in this first novel but the strength of the narrative and the beauty of the descriptive passages carries the day. Having set the tragic scene we move on a short while in the second novel (The day of the Scorpion) and introduce a lot of the later characters on which the consequences of the first novels outcome rest. This is a truly fantastic read setting out the early life of many of the characters - young men and women whom the fall of the British empire in India would affect the most. A whole exotic world of hill station life and people going out to India form England is recreated here all of it now passed into history. The author gets right into the mind of the characters with all the certainties and doubts of the British empire that come apart at the seams when war breaks out in the far east. A gripping and entertaining novel it was a superb unforgettable read that I could not put down - never dull for a moment the story and evocation of life in India just flowed of the pages. The third novel (The Towers of Silence) brings in extra but vitally important characters that are themselves on the periphery of Raj life which was hopelessly class ridden yet held together only really by the idea that white British people were chosen almost by god to rule India. Yet not having the "correct" background or money meant there were layers within white society that were hardly acceptable - this novel explores these concepts in riveting detail. Moving yet amusing in places this really gets to grips with the whole Raj experience of Empire and the different classes of people who administered it. Yet whilst it explores these levels of snobbery it also links all the other characters stories together so when in the final novel the strands come together it all becomes clear. The fourth and final novel "A Division of the Spoils" is concerned with the coming Independence of India and its partition. The people whose lives have been spent in India ruling and administrating face the twilight of the British Raj with uncertainty as the Muslims and Hindus that make up India's population battle it out in dreadful intercommunity slaughter. With all the previously certain things in their lives turned upside down the problems affect ruling Indians too in the princely states whose existence was guaranteed by British rule. Political intrigue and betrayal as well as a coming together of threads fist started in the first novel all occur in this the final novel. For me this last novel cleared up many of the uncertainties but still left a few enigmas. By far the most gripping of all the novels mainly because of the finalisation of the story the many twists and turns of the saga carried on right until the end. At no time throughout the books could I have foreseen the outcome or the reasoning behind it.

Power, Love, Sex, Betrayal, War, wasted lives, dashed hopes all set in an exotic world long forgotten, a powerful moving gripping saga that I feel has been overlooked in recent years dealing as it does with the largely forgotten British Empire in India. At no time does this glorify Empire - in fact it is damning in its criticism of both sides of the racial divide, the central tenet of the whole work is absurdity of those in the British community who see their role in India far too seriously, as if God had ordained them to rule and the tragic consequences of this to themselves and those around them. Altogether a superb read rich in detail, beautiful narrative and a wonderful sense of an on going story. A beautiful touch was the inclusion early in the third book of a couple of ancillary characters that later went on to be the basis of Paul Scott's Booker prize winning book Staying On six years later along with other characters form the Raj Quartet. I'll recommend the Raj Quartet for a superb holiday read - it is available as a large all in one volume, I read mine as the Granada paperbacks from the early 80's that were republished to compliment the 14 part TV series "The Jewel in the Crown".

Four impressive books make the Raj quartet, "The Jewel in the Crown" (480pgs) "The Day of the Scorpion" (495 pgs) "The Towers of Silence" (397pgs) "A Division of the Spoils" (720pgs). A lot to read - over 2000 pages - but of such quality, such perfectly interlocking storylines spread over the four books . Characters and situations in the first book carry through to the last in a beautifully natural way. The huge cast of characters become familiar over the four books so as a reader you get so involved, so engrossed that you really begin to care about these people. Such superb intricate detail is described throughout the novels that the beauty and magnificence of India is brought to life. Set in India during the British Empire - The Raj - it spans a time from the early 30's throughout the war to Independence of India and the partition in to Pakistan and India. It’s a series of events told from several different perspectives both British and Indian. We get intricate backgrounds of the many characters in scrumptious detail then intricate plotting that intrigues and entertains. It is both warm and heartrending yet through provoking as it explores the many facets of the Indian Empire ruled by really only a handful of British civilians and soldiers. We are taken into their lives and we see all sides to them as they try to react to events and history unfolding around them.

Each of the four novels could be read as a stand-alone novel but to really appreciate what the author Paul Scott (who died in 1978) was trying to achieve a back-to-back read of all four is necessary. I was lucky having spent many months finding these novels in matching covers then being able to read them as a holiday read all together. We are taken in the storyline through a series of key events small and large that shapes the lives of those concerned against a backdrop of war and forthcoming Indian independence. Forbidden relationships between a white British woman of the ruling Raj class and an educated Indian who has been to the best British boarding school have a tragic outcome and set in turn a series events that follow key characters around India till independence. Key events and characters dip in and out of the novels - someone in the first novel may reappear in the third yet it all happens seamlessly and not at all contrived. The massive groundwork done in the first novel is carried through to fruition in the final three works. The first novel (The Jewel in the Crown) is told a lot of the time in flashback giving the tragic events that unfold a view from several different perspectives. This admittedly slows the pace somewhat in this first novel but the strength of the narrative and the beauty of the descriptive passages carries the day. Having set the tragic scene we move on a short while in the second novel (The day of the Scorpion) and introduce a lot of the later characters on which the consequences of the first novels outcome rest. This is a truly fantastic read setting out the early life of many of the characters - young men and women whom the fall of the British empire in India would affect the most. A whole exotic world of hill station life and people going out to India form England is recreated here all of it now passed into history. The author gets right into the mind of the characters with all the certainties and doubts of the British empire that come apart at the seams when war breaks out in the far east. A gripping and entertaining novel it was a superb unforgettable read that I could not put down - never dull for a moment the story and evocation of life in India just flowed of the pages. The third novel (The Towers of Silence) brings in extra but vitally important characters that are themselves on the periphery of Raj life which was hopelessly class ridden yet held together only really by the idea that white British people were chosen almost by god to rule India. Yet not having the "correct" background or money meant there were layers within white society that were hardly acceptable - this novel explores these concepts in riveting detail. Moving yet amusing in places this really gets to grips with the whole Raj experience of Empire and the different classes of people who administered it. Yet whilst it explores these levels of snobbery it also links all the other characters stories together so when in the final novel the strands come together it all becomes clear. The fourth and final novel "A Division of the Spoils" is concerned with the coming Independence of India and its partition. The people whose lives have been spent in India ruling and administrating face the twilight of the British Raj with uncertainty as the Muslims and Hindus that make up India's population battle it out in dreadful intercommunity slaughter. With all the previously certain things in their lives turned upside down the problems affect ruling Indians too in the princely states whose existence was guaranteed by British rule. Political intrigue and betrayal as well as a coming together of threads fist started in the first novel all occur in this the final novel. For me this last novel cleared up many of the uncertainties but still left a few enigmas. By far the most gripping of all the novels mainly because of the finalisation of the story the many twists and turns of the saga carried on right until the end. At no time throughout the books could I have foreseen the outcome or the reasoning behind it.

Power, Love, Sex, Betrayal, War, wasted lives, dashed hopes all set in an exotic world long forgotten, a powerful moving gripping saga that I feel has been overlooked in recent years dealing as it does with the largely forgotten British Empire in India. At no time does this glorify Empire - in fact it is damning in its criticism of both sides of the racial divide, the central tenet of the whole work is absurdity of those in the British community who see their role in India far too seriously, as if God had ordained them to rule and the tragic consequences of this to themselves and those around them. Altogether a superb read rich in detail, beautiful narrative and a wonderful sense of an on going story. A beautiful touch was the inclusion early in the third book of a couple of ancillary characters that later went on to be the basis of Paul Scott's Booker prize winning book Staying On six years later along with other characters form the Raj Quartet. I'll recommend the Raj Quartet for a superb holiday read - it is available as a large all in one volume, I read mine as the Granada paperbacks from the early 80's that were republished to compliment the 14 part TV series "The Jewel in the Crown".

One of Stephen King's 10 most favorite series and Novels - The Christian Science Monitor

http://www.csmonitor.com/Books/2012/0...

http://www.csmonitor.com/Books/2012/0...

From the Imaginative Conservative - source: http://www.theimaginativeconservative...)

Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet: The English War and Peace

by Eva Brann

I want to begin with a judgment of luminous wrong-headedness. It has appeared twice in the pages of a widely-read weekly book review:

The Raj Quartet is one of the longest, most successfully rendered works of 19th century fiction written in the 20th century.

It is, of course, meant to be put-down, not praise.

What is wrong-headed is the prank played with chronology. Time serves us in no other way than as an imperturbable order of succession. Dates of existence give us the only hard ordering frame we have for the world in its going. Consequently if a novel was completed in 1975, it is a contemporary novel, and should be counted as such.

And that is, of course, precisely what is illuminating in the dictum above. It implies that citizenship in one’s time does not accrue by mere reason of date of birth but must be earned by passing a critical test: The honor of being here and now is bestowed by the craft of critics.

With respect to novels this perverse notion, that the times accredit the work rather than the work the times, takes potently concrete shape. One would think that all the books recognized as novels come to establish a genre: the fairly lengthy prose fiction,

For such an ex post facto genre the exception proves the rule, and so deviations are readily accommodated: There are novels all in rhyme (e.g„ Vikram Seth, Golden Gate), non-fiction novels that are meticulous reportage (e.g., Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood), and novels which are one-fifteenth as long as others (cf. Robbe-Grillet’s In the Labyrinth and War and Peace).

In criticism, however, instead of novels there appears something called “The Novel.” It behaves not as a genre but as a species: It has a line of evolution within which throw-backs like The Raj Quartet are discernible. Since it has become maladaptive, it is probably heading toward extinction, to join the dinosaurs. It is on this evolutionary hypothesis that what David Lodge calls the sermons on the text “Is the novel dying” (38) have become a preoccupation of criticism.

There is some agreement about the change in environment to which The Novel is failing to adapt. It is Reality that is killing The Novel, or rather the transmutation of reality, not from one state of affairs to another, but out of itself altogether: “Reality is no longer realistic,” as Norman Mailer says in The Man Who Studied Yoga, What this paradox is intended to mean is that there is no common phenomenal world anymore; our environment has gone surreal. Hence it requires a new novel, one that experiments with “fabulating” techniques: inversions of fact and fiction, randomness, surrealisms both vulgar and sophisticated, and bottomless subjectivism.

Now there has got to be something wrong with this vision of things. That the phenomenal world has illusionistic aspects is simply the wisdom of the ancients, and it is not what is meant here. That our contemporary world has been largely transmogrified into second nature, so that primary beings are harder to find, and that the traditional centers are giving way to fragmented perspectives—these and all the other much-debated features of modernity may make the genealogy of “Reality” harder to trace. But surely the notion that reality is over is a decision and not a finding, a sort of deliberate self-spooking. To put it another way: the coroners of Reality are also its assassins.

Oddly enough, among the motives for writing finis to the traditional novel one powerful purpose is precisely the establishment of a purer, sharper reality. Recall that “reality” is Latin for “thinginess.” Robbe-Grillet’s chosisme” is intended to disinfect things and purify them of their human meaning, so as to restore their pristine independence.

Either way, what is clear is that the putatively dying novel is the so-called “realistic novel.” What would be a good description of this, essentially the traditional novel? To begin with, realism, the usual critical term, is not quite accurate, for the great traditional novels are full of psychic and surreal episodes.

There is, however, a delineation by Iris Murdoch of a novel of tolerance which comes closer to the novel that is said to have come to its end:

A great novelist is essentially tolerant, that is, displays a real apprehension of persons other than the author as having a right to existence and to have a separate mode of being which is important and interesting to themselves.

I must say that the defense of the characters inhabiting great novels in terms of their civil rights gives me a little pause. (Murdoch is defining the great novel as an expression of Classical Liberalism.) Moreover, tolerance seems a faint term for the affirmative sympathy great authors bestow on their characters. Nonetheless, “real persons more or less naturalistically presented” as being “mutually-independent centers of significance” are indeed to be found in the works of the novelists she mentions, among whom are Jane Austen and Tolstoy. Now here is a huge claim: Paul Scott belongs in this company.

Let me begin to defend this claim with respect first to tolerance and then to Tolstoy. I shall use as a small preliminary example Scott’s treatment of a character who really requires a lot of toleration: Captain Jimmy Clark, one of the old boys of Chillingborough, the public school that plays a fatal role in the book. Scott himself describes him in a later essay as a “wretched cad of a chap,” who, regrettably, succeeds in seducing Sarah, the major woman of the novel. Yet for all his sexual cockiness and brutal candor, it is he, and not the gentlemanly chaps, who has the ear for fine classical sitar playing. That too is in Scott’s account. It figures in, though it does not outweigh Clark’s coarseness toward Sarah. Tolerance does not preclude fine moral reckoning (see III).

As for Tolstoy, the comparison was suggested in passing by David Rubin, whose brief account of the novel is laden with insights. He was corrected in a review by Lawrence Graver, who proposes that Trollope rather than Tolstoy is the proper counterpart. Now I am a loyal Trollope lover, but this comparison seems to me absurd. Trollope is said to have had more than an amateurish knowledge of English parliamentary politics, and he certainly has a wide and nuanced knowledge of English types. But who was ever shaken by the fateful pathos of his setting or his people, as one might be by Scott’s? On the contrary, Trollope’s world is the quintessence of snugness. That is why he was so fervently revived during the Second World War.

No, the comparison with Tolstoy is much more telling. First, War and Peace and The Raj Quartet are both long-breathed and large-scened, though they do differ from each other—as the Russia of 1812 differs from the Anglo-India of 1942. Tolstoy’s Russians offer indomitable though inertial resistance to the Western invader of their large land; the British depicted by Scott subjugate an immense continent with half-hearted sedulousness.

That apotheosis of warm-hearted Russian girlhood, Natasha, finds her entirely lovable completion in bossy, dowdy houswifehood. The ungainly, inhibited English girl Sarah, on the other hand, finds at the end release from family and a dawning love of her own. In both novels these consummations take place in the short epilogue of peace—deadly in the Indian case—that succeeds the great war. The Russian book is elemental and golden, overlaid with the sheen of a serene love of the land; the English book is complex and melancholy, ridden with moral scruple, decline, and loss of faith in England.

Accordingly Tolstoy and Scott, who both reflect on history, have opposite views of it. Tolstoy thinks that it is only the integral of very small human differentials, which consequently make all the difference. Scott, sensitive to India’s immensity, emphasizes the frailty of human action in the face of history’s “moral drift” (1987, 13).

Nonetheless, they and their novels end alike, with the children: Just as, in the last pages of War and Peace, Andre Bolkonsky’s son Nikolai fervently promises to make his dead father proud, so The Jewel in the Crown ends with an episode that postdates the quartet as a whole. Parvati, the lovely young daughter of a dead English mother and a self-exiled Indian father, goes off to her music lesson. She will grow up to be a gifted keeper of the great tradition, the Indian music that her mother had just begun to understand.

Putting The Raj Quartet in Tolstoyan company implies of course that it is a great novel. Let me specify the elements that seem to me to make it so:

Continued in next post:

Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet: The English War and Peace

by Eva Brann

I want to begin with a judgment of luminous wrong-headedness. It has appeared twice in the pages of a widely-read weekly book review:

The Raj Quartet is one of the longest, most successfully rendered works of 19th century fiction written in the 20th century.

It is, of course, meant to be put-down, not praise.

What is wrong-headed is the prank played with chronology. Time serves us in no other way than as an imperturbable order of succession. Dates of existence give us the only hard ordering frame we have for the world in its going. Consequently if a novel was completed in 1975, it is a contemporary novel, and should be counted as such.

And that is, of course, precisely what is illuminating in the dictum above. It implies that citizenship in one’s time does not accrue by mere reason of date of birth but must be earned by passing a critical test: The honor of being here and now is bestowed by the craft of critics.

With respect to novels this perverse notion, that the times accredit the work rather than the work the times, takes potently concrete shape. One would think that all the books recognized as novels come to establish a genre: the fairly lengthy prose fiction,

For such an ex post facto genre the exception proves the rule, and so deviations are readily accommodated: There are novels all in rhyme (e.g„ Vikram Seth, Golden Gate), non-fiction novels that are meticulous reportage (e.g., Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood), and novels which are one-fifteenth as long as others (cf. Robbe-Grillet’s In the Labyrinth and War and Peace).

In criticism, however, instead of novels there appears something called “The Novel.” It behaves not as a genre but as a species: It has a line of evolution within which throw-backs like The Raj Quartet are discernible. Since it has become maladaptive, it is probably heading toward extinction, to join the dinosaurs. It is on this evolutionary hypothesis that what David Lodge calls the sermons on the text “Is the novel dying” (38) have become a preoccupation of criticism.

There is some agreement about the change in environment to which The Novel is failing to adapt. It is Reality that is killing The Novel, or rather the transmutation of reality, not from one state of affairs to another, but out of itself altogether: “Reality is no longer realistic,” as Norman Mailer says in The Man Who Studied Yoga, What this paradox is intended to mean is that there is no common phenomenal world anymore; our environment has gone surreal. Hence it requires a new novel, one that experiments with “fabulating” techniques: inversions of fact and fiction, randomness, surrealisms both vulgar and sophisticated, and bottomless subjectivism.

Now there has got to be something wrong with this vision of things. That the phenomenal world has illusionistic aspects is simply the wisdom of the ancients, and it is not what is meant here. That our contemporary world has been largely transmogrified into second nature, so that primary beings are harder to find, and that the traditional centers are giving way to fragmented perspectives—these and all the other much-debated features of modernity may make the genealogy of “Reality” harder to trace. But surely the notion that reality is over is a decision and not a finding, a sort of deliberate self-spooking. To put it another way: the coroners of Reality are also its assassins.

Oddly enough, among the motives for writing finis to the traditional novel one powerful purpose is precisely the establishment of a purer, sharper reality. Recall that “reality” is Latin for “thinginess.” Robbe-Grillet’s chosisme” is intended to disinfect things and purify them of their human meaning, so as to restore their pristine independence.

Either way, what is clear is that the putatively dying novel is the so-called “realistic novel.” What would be a good description of this, essentially the traditional novel? To begin with, realism, the usual critical term, is not quite accurate, for the great traditional novels are full of psychic and surreal episodes.

There is, however, a delineation by Iris Murdoch of a novel of tolerance which comes closer to the novel that is said to have come to its end:

A great novelist is essentially tolerant, that is, displays a real apprehension of persons other than the author as having a right to existence and to have a separate mode of being which is important and interesting to themselves.

I must say that the defense of the characters inhabiting great novels in terms of their civil rights gives me a little pause. (Murdoch is defining the great novel as an expression of Classical Liberalism.) Moreover, tolerance seems a faint term for the affirmative sympathy great authors bestow on their characters. Nonetheless, “real persons more or less naturalistically presented” as being “mutually-independent centers of significance” are indeed to be found in the works of the novelists she mentions, among whom are Jane Austen and Tolstoy. Now here is a huge claim: Paul Scott belongs in this company.

Let me begin to defend this claim with respect first to tolerance and then to Tolstoy. I shall use as a small preliminary example Scott’s treatment of a character who really requires a lot of toleration: Captain Jimmy Clark, one of the old boys of Chillingborough, the public school that plays a fatal role in the book. Scott himself describes him in a later essay as a “wretched cad of a chap,” who, regrettably, succeeds in seducing Sarah, the major woman of the novel. Yet for all his sexual cockiness and brutal candor, it is he, and not the gentlemanly chaps, who has the ear for fine classical sitar playing. That too is in Scott’s account. It figures in, though it does not outweigh Clark’s coarseness toward Sarah. Tolerance does not preclude fine moral reckoning (see III).

As for Tolstoy, the comparison was suggested in passing by David Rubin, whose brief account of the novel is laden with insights. He was corrected in a review by Lawrence Graver, who proposes that Trollope rather than Tolstoy is the proper counterpart. Now I am a loyal Trollope lover, but this comparison seems to me absurd. Trollope is said to have had more than an amateurish knowledge of English parliamentary politics, and he certainly has a wide and nuanced knowledge of English types. But who was ever shaken by the fateful pathos of his setting or his people, as one might be by Scott’s? On the contrary, Trollope’s world is the quintessence of snugness. That is why he was so fervently revived during the Second World War.

No, the comparison with Tolstoy is much more telling. First, War and Peace and The Raj Quartet are both long-breathed and large-scened, though they do differ from each other—as the Russia of 1812 differs from the Anglo-India of 1942. Tolstoy’s Russians offer indomitable though inertial resistance to the Western invader of their large land; the British depicted by Scott subjugate an immense continent with half-hearted sedulousness.

That apotheosis of warm-hearted Russian girlhood, Natasha, finds her entirely lovable completion in bossy, dowdy houswifehood. The ungainly, inhibited English girl Sarah, on the other hand, finds at the end release from family and a dawning love of her own. In both novels these consummations take place in the short epilogue of peace—deadly in the Indian case—that succeeds the great war. The Russian book is elemental and golden, overlaid with the sheen of a serene love of the land; the English book is complex and melancholy, ridden with moral scruple, decline, and loss of faith in England.

Accordingly Tolstoy and Scott, who both reflect on history, have opposite views of it. Tolstoy thinks that it is only the integral of very small human differentials, which consequently make all the difference. Scott, sensitive to India’s immensity, emphasizes the frailty of human action in the face of history’s “moral drift” (1987, 13).

Nonetheless, they and their novels end alike, with the children: Just as, in the last pages of War and Peace, Andre Bolkonsky’s son Nikolai fervently promises to make his dead father proud, so The Jewel in the Crown ends with an episode that postdates the quartet as a whole. Parvati, the lovely young daughter of a dead English mother and a self-exiled Indian father, goes off to her music lesson. She will grow up to be a gifted keeper of the great tradition, the Indian music that her mother had just begun to understand.

Putting The Raj Quartet in Tolstoyan company implies of course that it is a great novel. Let me specify the elements that seem to me to make it so:

1. First there is indeed that widely affirmative mode Murdoch calls tolerance. Elizabeth Bowen says somewhere that “a novelist must be imperturbable.” Scott, on the other hand, advises the novelist: “You must commit yourself” (1987, 79). It appears to be the fusion of these, serene engagement and subtle wholeheartedness, that is the psychic mode of great novels.

2. The great novels are full of resolved complexity. The net they knit is enormous, but there are no dropped stitches or loose ends. The prime example in the Quartet is the underground life of one of the two precipitating characters, Parvati’s occulted father, Hari Kumar, the Anglicized Indian with whom Daphne Manners falls in love and who is accused of her rape. He vanishes from view after the first book, re-emerges in a harrowing interrogation in the second, only to disappear, as it seems, for good. His absence hovers over the second half of the novel: Has the author forgotten him, left him dangling? But he returns toward the end, though not in propria persona— those connections are missed. He reappears rather as a printed voice, a voice of infinite melancholy, writing essays about the lost Eden of England, indeed about Chillingborough, essays which are signed with the name Philoctetes, the betrayed archer-hero with the incurable wound.

3. A great novelist has in mind thousands of bits of knowledge which when selected appear to accrue significance on their own. Scott refers to this property as “graces bestowed” (1987, 215). He lists as examples both the name Daphne, which is a laurel native to Eurasia and the name of a nymph metamorphosed into that shrub while running from a god; and the name Philoctetes, which Scott relates to the Great Archer Hari. But such felicities are legion in the novel.

4. In all the great novels I know there is an inextricable reciprocity of scenes and characters, of atmosphere and action. The Raj Quartet is full of subtle deeds and fine-spun conversations which slowly weave a magnificent panoramic tapestry. But it also exudes strong, strange-familiar redolences, enveloping auras, which seem to precipitate the individual figures. In Section IV below something will be said about how Scott achieves this effect.

5. The occurrences and deeds of great novels are explicit. In particular is the evil done literal evil. I shall dwell on this matter in the next section. In sum, a very great novel, a post-final novel, was completed little more than a decade ago, although The Novel was supposed to be dead. Or as Scott puts it, inveighing against the “literary body-snatchers the sort of people who prove that the novel is dead because they want it to be”: “Well, if the novel is dead, all I can say is that it’s having a lovely funeral” (1987, 193).

Continued in next post:

II The Philistine Satan

The Raj Quartet has something War and Peace lacks: an evil presence of enormous pathos. It is the almost vibrant desolation around this person which confirms Scott as a “tolerant” novelist in the most positive sense.

This villain is Ronald Merrick, whose name, as so many in this novel, sounds overtones, here those of merit gone wrong. There are, to be sure, other unadmirable characters in the book. Authorial tolerance, as has been said, does not preclude personal or moral aversion.

There is, above all, Sarah’s mother Mildred Layton, a languidly snobbish, rigid Memsahib, who displays, however, her own sort of arid valor.

There is also Pandit Baba, the fanatical behind-the-scenes instigator of rebellion, Merrick’s ultimate nemesis, who has, for all his slipperiness, a certain blunt righteousness.

But neither of these has the odor of unholiness that hangs about the monstrously efficient District Superintendent of Police in Mayapore, later a captain in the Indian army, who acquires a defacing scar and a prosthetic hand.

But great treatments of human evil do not take refuge in indeterminate demonisms. They have the courage of their moral revulsion: Definite crimes are committed. Take for example that dark evil which preoccupies Marlowe in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, surely the greatest novelette of our century. For all its ineffable horror, there are also namable misdeeds: Kurtz has allowed himself to be worshipped as a god, with human sacrifices. Or consider how much more vaporous Dostoevsky’s Possessed became when the first editor prudishly excluded Stavrogin’s confession, which reveals the actual deed corresponding to his spiritual perversion: He had seduced and driven to suicide a little girl.

Scott’s Merrick tortures and molests prisoners, and drives one of them to suicide. He manipulates superiors, blackmails subordinates, and abuses confidential knowledge—always working discreetly, though at the limits.

Moreover, the explanation of this appalling man’s conduct is given along straightforwardly secular lines, in terms of an unfortunate conjunction of sexual pathology, social inferiority, and tearingly ambiguous racial feeling.

This not unsympathetic account, rendered after Merrick’s lurid semi-suicidal death, comes from the most understanding quarter, the wise and decent sophisticate and long-inactive homosexual, Count Bronowski (Book IV, 594).

It is because there are real crimes and secular diagnosis that Merrick can acquire theological gravity. This perspective is provided by one of the most moving figures in fiction, Barbie Batchelor, the missionary spinster whose book, The Towers of Silence, is the intense heart of the Raj series. She is the sort of person one could not stand to spend an hour with in a social setting. She scurries about officiously and talks compulsively. But Scott follows her fate from her own center, from the threatening void behind her chatter, through the spells of “imaginary silences,” moments of insight when she does not know whether she has actually uttered anything, to her final mute madness. Her despair derives from love deprived of an aim; above all she is oppressed by an intense devotion to an absconded god.

This woman’s precarious sanity is finally unhinged as a direct result of her encounter with Merrick. She is packed and ready to leave Pankot when she first catches a glimpse of him; she gasps “both at the sight of a man and at the noxious emanation that lay like an almost visible miasma around the plants along the balustrade which had grown dense and begun to trail tendrils.”

In the course of their meeting he had sought her out as he had gone after other victims he had chosen: men, women, finally a child he teaches her about despair. In particular he reveals to her the despair behind the suttee-like death of her friend and heroine, Edwina Crane. Miss Crane had set herself afire after the fatal beating of the schoolmaster Chaudhuri, who had been protecting her from a mob on the road from Dibrapur:

“There is no God. Not even on the road from Dibrapur.” An invisible lightning struck the veranda. The purity of its colourless fire etched shadows on his face. The cross glowed on her breast and then seemed to burn out (375).

Having thus undone Damascus, he sends her off on a tonga which, over-burdened with the weight of her trunk (it contains the testimonials of her life), careens down-hill to calamity. Her last sane words are: “I have seen the devil.”

That Merrrick is Satanic is utterly clear: He has a sort of non-being; he is “a man,” as Guy Perrin, the fresh hero of the last book says, “who comes too late and invents himself to make up for it”—too late, that is, for the kind of domination he longs to exercise. He hunts and catches souls. He purveys despair. But he is a smaller and newer devil than Milton’s “lost Archangel” who rules Pandemonium in self-confident grandeur. Merrick is goaded to middle-class ressentiment by the frosty superiority of the Chillingburians, white and black, not possessed by rebellious pride. What is more devastating, he is a renegade without a Lord, consigned to traveling to and fro in India and to riding up and down in it with no one to report to. He is a devil in a world without a god, a humanistic devil, a human devil, a human being.

Now I am mindful of the cheap frisson to be gained from that notorious interpretational identity: “The ostensibly human character X is really the mythical Y,” the Great Earth Mother, say, or the Wicked Witch of the West. But aside from the fact that Scott’s indicators are unmistakable, it is actually only to Barbie Batchelor that Ronald Merrick is the devil, and his essentially human deviltry is the direct complement of God’s absence: In a world from which God has absconded a man can be a demon.

The wonder is that this frigid philistine can invest his own perverted person with such a bleakly piteous aura. Scott’s early novels, some of which are clear preludes to The Raj Quartet, are all about the moral struggle of lonely men against forces of disintegration. It is almost as if Merrick had been molded out of the negative to their common essence.

Continued in next post

The Raj Quartet has something War and Peace lacks: an evil presence of enormous pathos. It is the almost vibrant desolation around this person which confirms Scott as a “tolerant” novelist in the most positive sense.

This villain is Ronald Merrick, whose name, as so many in this novel, sounds overtones, here those of merit gone wrong. There are, to be sure, other unadmirable characters in the book. Authorial tolerance, as has been said, does not preclude personal or moral aversion.

There is, above all, Sarah’s mother Mildred Layton, a languidly snobbish, rigid Memsahib, who displays, however, her own sort of arid valor.

There is also Pandit Baba, the fanatical behind-the-scenes instigator of rebellion, Merrick’s ultimate nemesis, who has, for all his slipperiness, a certain blunt righteousness.

But neither of these has the odor of unholiness that hangs about the monstrously efficient District Superintendent of Police in Mayapore, later a captain in the Indian army, who acquires a defacing scar and a prosthetic hand.

But great treatments of human evil do not take refuge in indeterminate demonisms. They have the courage of their moral revulsion: Definite crimes are committed. Take for example that dark evil which preoccupies Marlowe in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, surely the greatest novelette of our century. For all its ineffable horror, there are also namable misdeeds: Kurtz has allowed himself to be worshipped as a god, with human sacrifices. Or consider how much more vaporous Dostoevsky’s Possessed became when the first editor prudishly excluded Stavrogin’s confession, which reveals the actual deed corresponding to his spiritual perversion: He had seduced and driven to suicide a little girl.

Scott’s Merrick tortures and molests prisoners, and drives one of them to suicide. He manipulates superiors, blackmails subordinates, and abuses confidential knowledge—always working discreetly, though at the limits.

Moreover, the explanation of this appalling man’s conduct is given along straightforwardly secular lines, in terms of an unfortunate conjunction of sexual pathology, social inferiority, and tearingly ambiguous racial feeling.

This not unsympathetic account, rendered after Merrick’s lurid semi-suicidal death, comes from the most understanding quarter, the wise and decent sophisticate and long-inactive homosexual, Count Bronowski (Book IV, 594).

It is because there are real crimes and secular diagnosis that Merrick can acquire theological gravity. This perspective is provided by one of the most moving figures in fiction, Barbie Batchelor, the missionary spinster whose book, The Towers of Silence, is the intense heart of the Raj series. She is the sort of person one could not stand to spend an hour with in a social setting. She scurries about officiously and talks compulsively. But Scott follows her fate from her own center, from the threatening void behind her chatter, through the spells of “imaginary silences,” moments of insight when she does not know whether she has actually uttered anything, to her final mute madness. Her despair derives from love deprived of an aim; above all she is oppressed by an intense devotion to an absconded god.

This woman’s precarious sanity is finally unhinged as a direct result of her encounter with Merrick. She is packed and ready to leave Pankot when she first catches a glimpse of him; she gasps “both at the sight of a man and at the noxious emanation that lay like an almost visible miasma around the plants along the balustrade which had grown dense and begun to trail tendrils.”

In the course of their meeting he had sought her out as he had gone after other victims he had chosen: men, women, finally a child he teaches her about despair. In particular he reveals to her the despair behind the suttee-like death of her friend and heroine, Edwina Crane. Miss Crane had set herself afire after the fatal beating of the schoolmaster Chaudhuri, who had been protecting her from a mob on the road from Dibrapur: