The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

Devil in the Grove

CIVIL RIGHTS

>

ARCHIVE - APRIL 2016 - SPOILER THREAD - Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America by Gilbert King

I am sure that there are some young people in the group and here is a History for Kids Video about Thurgood Marshall:

https://youtu.be/9UtxSIXr5yM

Source: Youtube

https://youtu.be/9UtxSIXr5yM

Source: Youtube

message 3:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Mar 29, 2016 10:50AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Brown vs. Board of Education - Thurgood Marshall

Part One:

https://youtu.be/XMNGNXGo82g

Part Two:

https://youtu.be/_Cuztsow-Ps

Note: There seems to be some overlap/duplication for five minutes or so and then there is new footage

Source: Youtube (The Gist of Freedom)

Part One:

https://youtu.be/XMNGNXGo82g

Part Two:

https://youtu.be/_Cuztsow-Ps

Note: There seems to be some overlap/duplication for five minutes or so and then there is new footage

Source: Youtube (The Gist of Freedom)

message 5:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Mar 29, 2016 11:03AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

American Forum - The Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America

The Miller Center is a nonpartisan institute that seeks to provide critical insights for the nation’s governance challenges.

Gilbert King

September 4, 2013

11:00AM - 12:00PM

Gilbert King has written about Supreme Court history and the death penalty for The New York Times and The Washington Post, and is a featured contributor to Smithsonian magazine's history blog, “Past Imperfect,” as well as The Washington Post's “The Root.” His book, The Execution of Willie Francis, was published in 2008.

Gilbert’s most recent book is Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 2013.

Devil in the Grove draws on never-before-published material about the deadliest case of future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall’s career. Gilbert is also a photographer whose work has appeared in Glamour and New York Magazine, as well as international editions of Vogue, Harper's Bazaar, Marie Claire, Cosmopolitan, and Elle.

Video: http://web1.millercenter.org/forums/v...

Other Link:

http://millercenter.org/events/2013/t...

Source: Youtube

The Miller Center

The Miller Center is a nonpartisan institute that seeks to provide critical insights for the nation’s governance challenges.

Gilbert King

September 4, 2013

11:00AM - 12:00PM

Gilbert King has written about Supreme Court history and the death penalty for The New York Times and The Washington Post, and is a featured contributor to Smithsonian magazine's history blog, “Past Imperfect,” as well as The Washington Post's “The Root.” His book, The Execution of Willie Francis, was published in 2008.

Gilbert’s most recent book is Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 2013.

Devil in the Grove draws on never-before-published material about the deadliest case of future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall’s career. Gilbert is also a photographer whose work has appeared in Glamour and New York Magazine, as well as international editions of Vogue, Harper's Bazaar, Marie Claire, Cosmopolitan, and Elle.

Video: http://web1.millercenter.org/forums/v...

Other Link:

http://millercenter.org/events/2013/t...

Source: Youtube

The Miller Center

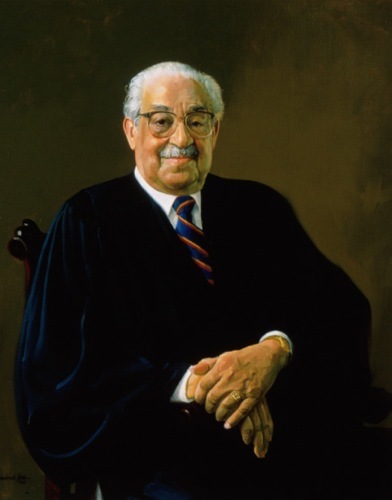

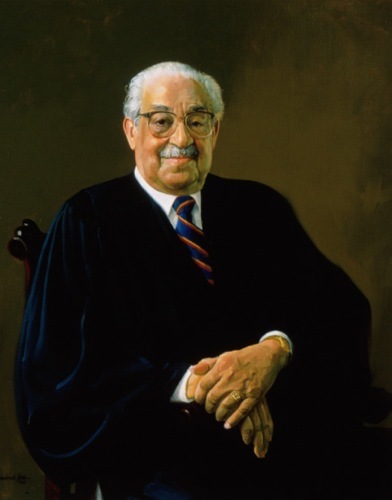

Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood MarshallCivil Rights Activist, Supreme Court Justice, Judge, Lawyer (1908–1993)

Thurgood Marshall was instrumental in ending legal segregation and became the first African-American justice of the Supreme Court.

Synopsis

Born on July 2, 1908, in Baltimore, Maryland, Thurgood Marshall studied law at Howard University. As counsel to the NAACP, he utilized the judiciary to champion equality for African Americans. In 1954, he won the Brown v. Board of Education case, in which the Supreme Court ended racial segregation in public schools. Marshall was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1967, and served for 24 years. He died in Maryland on January 24, 1993.

Early Life

Thurgood Marshall was born on July 2, 1908, in Baltimore, Maryland. His father, William Marshall, the grandson of a slave, worked as a steward at an exclusive club. His mother, Norma, was a kindergarten teacher. One of William Marshall's favorite pastimes was to listen to cases at the local courthouse before returning home to rehash the lawyers' arguments with his sons. Thurgood Marshall later recalled, "Now you want to know how I got involved in law? I don't know. The nearest I can get is that my dad, my brother, and I had the most violent arguments you ever heard about anything. I guess we argued five out of seven nights at the dinner table."

Marshall attended Baltimore's Colored High and Training School (later renamed Frederick Douglass High School), where he was an above-average student and put his finely honed skills of argument to use as a star member of the debate team. The teenaged Marshall was also something of a mischievous troublemaker. His greatest high school accomplishment, memorizing the entire United States Constitution, was actually a teacher's punishment for misbehaving in class.

After graduating from high school in 1926, Marshall attended Lincoln University, a historically black college in Pennsylvania. There, he joined a remarkably distinguished student body that included Kwame Nkrumah, the future president of Ghana; Langston Hughes, the great poet; and Cab Calloway, the famous jazz singer.

After graduating from Lincoln with honors in 1930, Marshall applied to the University of Maryland Law School. Despite being overqualified academically, Marshall was rejected because of his race. This firsthand experience with discrimination in education made a lasting impression on Marshall and helped determine the future course of his career. Instead of Maryland, Marshall attended law school in Washington, D.C. at Howard University, another historically black school. The dean of Howard Law School at the time was the pioneering civil rights lawyer Charles Houston. Marshall quickly fell under the tutelage of Houston, a notorious disciplinarian and extraordinarily demanding professor. Marshall recalled of Houston, "He would not be satisfied until he went to a dance on the campus and found all of his students sitting around the wall reading law books instead of partying." Marshall graduated magna cum laude from Howard in 1933.

Murray v. Pearson

After graduating from law school, Marshall briefly attempted to establish his own practice in Baltimore, but without experience he failed to land any significant cases. In 1934, he began working for the Baltimore branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. In one of Marshall's first cases—which he argued alongside his mentor, Charles Houston—he defended another well-qualified undergraduate, Donald Murray, who like himself had been denied entrance to the University of Maryland Law School. Marshall and Houston won Murray v. Pearson in January 1936, the first in a long string of cases designed to undermine the legal basis for de jure racial segregation in the United States.

Chambers v. Florida & Smith v. Allwright

Later in 1936, Marshall moved to New York City to work full time as legal counsel for the NAACP. Over the following decades, Marshall argued and won a variety of cases to strike down many forms of legalized racism, helping to inspire the American Civil Rights Movement. Marshall's first victory before the Supreme Court came in Chambers v. Florida (1940), in which he successfully defended four black men who had been convicted of murder on the basis of confessions coerced from them by police. Another crucial Supreme Court victory came in the 1944 case of Smith v. Allwright, in which the Court struck down the Democratic Party's use of whites-only primary elections in various Southern states.

Brown v. Board of Education

However, the great achievement of Marshall's career as a civil-rights lawyer was his victory in the landmark 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. The class action lawsuit was filed on behalf of a group of black parents in Topeka, Kansas on behalf of their children forced to attend all-black segregated schools. Through Brown v. Board, one of the most important cases of the 20th century, Marshall challenged head-on the legal underpinning of racial segregation, the doctrine of "separate but equal" established by the 1896 Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal," and therefore racial segregation of public schools violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. While enforcement of the Court's ruling proved to be uneven and painfully slow, Brown v. Board provided the legal foundation, and much of the inspiration, for the American Civil Rights Movement that unfolded over the next decade. At the same time, the case established Marshall as one of the most successful and prominent lawyers in America.

Circuit Court Judge & Solicitor General

In 1961, then-newly elected President John F. Kennedy appointed Thurgood Marshall as a judge for the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals. Serving as a circuit court judge over the next four years, Marshall issued more than 100 decisions, none of which was overturned by the Supreme Court. Then, in 1965, Kennedy's successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, appointed Marshall to serve as the first black U.S. solicitor general, the attorney designated to argue on behalf of the federal government before the Supreme Court. During his two years as solicitor general, Marshall won 14 of the 19 cases that he argued before the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court Justice

Finally, in 1967, President Johnson nominated Marshall to serve on the bench before which he had successfully argued so many times before—the United States Supreme Court. On October 2, 1967, Marshall was sworn in as a Supreme Court justice, becoming the first African American to serve on the nation's highest court.

Marshall joined a liberal Supreme Court headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren, which aligned with Marshall's views on politics and the Constitution. As a Supreme Court justice, Marshall consistently supported rulings upholding a strong protection of individual rights and liberal interpretations of controversial social issues. He was part of the majority that ruled in favor of the right to abortion in the landmark 1973 case Roe v. Wade, among several other cases. In the 1972 case Furman v. Georgia, which led to a de facto moratorium on the death penalty, Marshall articulated his opinion that the death penalty was unconstitutional in all circumstances.

Throughout Marshall's 24-year tenure on the Court, Republican presidents appointed eight consecutive justices, and Marshall gradually became an isolated liberal member of an increasingly conservative Court. For the latter part of his time on the bench, Marshall was largely relegated to issuing strongly worded dissents, as the Court reinstated the death penalty and limited affirmative action measures and abortion rights. Marshall retired from the Supreme Court in 1991; Justice Clarence Thomas replaced him.

Death and Legacy

Thurgood Marshall died on January 24, 1993, at the age of 84.

Thurgood Marshall stands alongside Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X as one of the greatest and most important figures of the American Civil Rights Movement. And although he may be the least popularly celebrated of the three, Marshall was arguably the most instrumental in the movement's achievements toward racial equality. Marshall's strategy of attacking racial inequality through the courts represented a third way of pursuing racial equality, more pragmatic than King's soaring rhetoric and less polemical than Malcolm X's strident separatism. In the aftermath of Marshall's death, an obituary read: "We make movies about Malcolm X, we get a holiday to honor Dr. Martin Luther King, but every day we live with the legacy of Justice Thurgood Marshall."

Personal Life

Marshall married Vivian "Buster" Burey in 1929, and the couple remained married until her death in 1955. Shortly thereafter, Marshall married Cecilia Suyat, his secretary at the NAACP; they had two sons, Thurgood Jr. and John Marshall.

(Source: Biography.com)

More:

by

by

Christine Taylor-Butler

Christine Taylor-Butler by

by

Chris Crowe

Chris Crowe

The Groveland Case

The Groveland CaseThe Groveland Case refers to events that took place in Groveland, Florida, from 1949 to 1951 and the resulting prosecutions related to four African-American men being accused of rape of a young white woman in 1949. One man was shot by a posse after having fled the area; the other three were quickly arrested but denied being in the area of the alleged rape. They were convicted by an all-white jury; one was sentenced to life as he was 16 years old; the other two were sentenced to death by electric chair.

In 1949, Harry T. Moore, the executive director of the Florida NAACP, organized a campaign against the wrongful conviction of three African Americans, including a 16-year-old, for the rape of a young white woman in Groveland. Two years later, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered a new trial. Soon afterward, Sheriff Willis V. McCall of Lake County, Florida, shot two of the men while they were in his custody, killing one and seriously wounding Irvin. At the second trial, Irvin was represented by Thurgood Marshall as special counsel, of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. Irvin was convicted by an all-white jury and sentenced to death. In 1955 his sentence was commuted to life by the Florida governor, and in 1968 he was paroled.

Case Details

On July 16, 1949, Norma Padgett, a 17-year-old Groveland, Florida white woman, accused four black men of rape, testifying that she and her husband were attacked when their car stalled on a rural road near Groveland. The next day, 16-year-old Charles Greenlee, Sam Shepherd, and Walter Irvin were arrested and put in jail pending trial. Ernest Thomas fled the county and avoided arrest for several days.

A Sheriff's posse of over 1000 armed men, found, shot and killed him about 200 miles northwest during a lengthy chase through the swamps. McCall was in the area when Thomas was killed, but a coroner's inquest was unable to determine exactly who killed the suspect.

McCall was out of the state when Greenlee, Irvin and Shepherd were first arrested, returning to Lake County the following day. As word spread about the accusation of rape and subsequent arrest of three of the "Groveland Boys", an angry crowd gathered at the county jail. The crowd demanded that McCall turn the men over to them. Just moments before, McCall had hidden Shepherd and Irvin in a nearby orange grove, then had them transferred to Raiford State Prison. After allowing Padgett's husband and father to search the jail, McCall promised the mob that he would see that justice was done and urged them to "...let the court handle this calmly."

With Shepherd and Irvin out of harm's way, the mob looked for a new target. They turned on a black section of Groveland, a small town in south Lake County where two of the accused and their families lived. The men drove to Groveland in a caravan and once they arrived, shot into the tavern owned by the mother of Ernest Thomas, and hurled insults at any blacks they found. On the third day, fearing an escalation of mob and Ku Klux Klan violence, McCall and several prominent businessmen in the area warned most of the black residents to leave town until things settled down, which most did. McCall called in the National Guard, but pulled troops away from the black section of Groveland. After that, the mob moved in and proceeded to burn Shepherd's house and two others to the ground. The presence of the National Guard halted the destruction caused by the rioters; but they were not satisfied. Cockcroft, the leader of the riot, revealed the mob's intentions when he told a reporter, "The next time, we'll clean out every Negro section in south Lake County."

A grand jury indicted the three remaining rape suspects. Shepherd and Greenlee separately later told FBI investigators that the deputies beat them until they confessed. Irvin refused to confess, despite also being severely beaten. An FBI investigation concluded that Lake County Sheriff's Department deputies James Yates and Leroy Campbell were responsible for the beatings, and agents documented the physical abuse with photographs. The Justice Department urged the U.S. Attorney in Tampa to file charges, but U.S. Attorney Herbert Phillips was reluctant, and failed to return indictments.

Once the trial began, the prosecution did not bring the alleged confessions into evidence, fearing that a higher court would overturn guilty verdicts on the grounds of coerced confessions. Shepherd and Irvin claimed they were in Eatonville, Florida, drinking that night. Greenlee claimed to be nowhere near the other defendants on that night and said that he had never met the other defendants until he was arrested and taken to the same jail in Tavares, Florida.

The physician who examined Norma Padgett was not called to the witness stand by the prosecution, and Judge Truman Futch did not allow the defense to call him. A forensics expert for the defense testified that the footprint casts were fraudulently manufactured by Deputy James Yates (Yates was indicted years later in another footprint case when another deputy admitted that Yates had fraudulently manufactured shoeprint evidence and an FBI investigation confirmed the plaster casts were faked. But before Yates could be tried, the statute of limitations had expired).

The three men were each convicted. Shepherd and Irvin were sentenced to death. Greenlee, because of his age, was sentenced to life in prison. Greenlee never appealed his conviction, as he faced receiving the death penalty in the future should another jury find him guilty again. In 1951, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Lake County's verdict on the grounds that blacks had been improperly excluded from the jury and ordered a new trial. But Justice Robert Jackson was more critical of the prejudicial pretrial publicity and McCall's trumpeting the coerced confessions to the press. In his concurring opinion, Justice Jackson wrote, "The case presents one of the best examples of one of the worst menaces to American justice."

In November 1951, McCall was transporting Shepherd and Irvin from Raiford to Tavares for the retrial, when he pulled his car off the state road leading into Umatilla, a small town in Lake County, claiming tire trouble. McCall swore in a deposition that Shepherd and Irvin attacked him in an escape attempt when he let them out of the car so that Shepherd could relieve himself. McCall claimed that the two prisoners attacked him in an escape attempt and he shot them both. Shepherd was killed on the spot, but Irvin played dead and survived, despite being shot three times. Deputy James Yates, arrived at the scene, observed that Irvin was still alive and shot him again.

The next day in his hospital room, Irvin told FBI investigators and the press that McCall shot them without provocation, as did Yates. Irvin claimed that Yates fired the sixth and last bullet into his neck, while Irvin was lying wounded on the ground. Irvin's story was verified by author Gary Corsair in his 2010 book Legal Lynching: The Sad Saga of The Groveland Four. In his book, Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America, author Gilbert King examined the unredacted FBI files from the case; he writes that the FBI located a .38 caliber bullet buried ten inches in the ground beneath Irvin's blood spot—evidence that supported Irvin's version of the shooting.

The Lake County Coroner's inquest never saw the FBI reports. The coroner concluded that McCall had acted in the line of duty, and Judge Truman Futch claimed that he saw no need to impanel a grand jury. The re-trial of Irvin was moved from Lake County to Marion County (the next county to the north).

It began in February 1952, after Irvin had recovered from the shooting. Prosecutor Jesse Hunter offered Irvin a deal: if he pled guilty to the rape of Padgett, the state would not seek the death penalty. Irvin refused, saying that he did not rape her and would not lie. He was defended in the re-trial by NAACP lawyer Thurgood Marshall (who later was appointed as an Associate Justice on the US Supreme Court).

The trial attracted international coverage; newspapers in the Soviet Union pointed to the trial as evidence that American blacks were not free. New evidence was presented, but the jury found Irvin guilty, after a short deliberation of 90 minutes. Judge Futch sentenced Irvin to death. The case was appealed again, but the conviction was upheld by the Florida State Supreme Court. In early 1954, the Supreme Court of the United States declined to hear the case.

After promising Irvin's mother that he would not let her boy die in the electric chair, Thurgood Marshall continued to seek relief outside the courts. He organized a committee of religious leaders to apply pressure on newly elected Governor LeRoy Collins, who in 1955 personally reviewed the case. He commuted Irvin's sentence to life in prison. After conducting his own investigation, Collins stated that "the State did not walk that extra mile--did not establish the guilt of Walter Lee Irvin in an absolute and conclusive manner."

Greenlee was paroled in 1962 and was living when Gilbert King's book was published in 2012. Irvin was paroled in 1968. In 1970, he visited Lake County and was found dead in his car, officially of natural causes. Marshall had some doubts.

(continued below)

Push for Exoneration

Push for ExonerationSen. Geraldine Thompson, D-Orlando, filed a proposed resolution (SCR 136) for consideration during the 2016 legislative session, which starts in January. The proposal would seek to clear the names of Charles Greenlee, Walter Irvin, Samuel Shepherd and Ernest Thomas and points to “egregious wrongs” perpetrated against the men by the criminal justice system. The resolution said the men had alibis but were arrested in the alleged attack. The push for exoneration is being aided by an online petition on change.org started by UF senior Joshua Venkataraman and also by extensive media coverage including an article by nationally syndicated columnist Leonard Pitts, Jr. in The Miami Herald.

Harry T. Moore Bombing

Harry T. Moore, an executive director of the Florida NAACP, demanded that McCall be indicted for murder following the Groveland rape case, and requested that the Governor suspend him from office. Six weeks after calling for McCall's removal, Moore and his wife were killed when a bomb exploded under their bedroom in Mims in Brevard County on Christmas night 1951. Rumors alleged that McCall was behind the bombing. However, an extensive FBI investigation at the time and additional separate investigations have failed to produce any evidence supporting the claim of McCall's involvement.

The Florida State Archives contain several letters that Moore wrote to Florida governors calling for McCall to be removed from office and prosecuted for allowing nightriders to burn down houses and terrorize black citizens in and around Bay Lake, Florida after the arrests of four men accused of raping a white woman in the summer of 1948. And NAACP leaders, including Thurgood Marshall and Franklin Williams, expressed their thoughts that McCall was somehow involved in Moore's murder.

In 2005, a new investigation was launched by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement to include excavation of the Moore home in a search for new forensic evidence to aid the investigation. On August 16, 2006, Florida Attorney General Charlie Crist announced his office had completed its 20-month investigation, resulting in the naming of four now-dead suspects, Earl Brooklyn, Tillman Belvin, Joseph Cox and Edward Spivey. All four had a long history with the Ku Klux Klan, serving as officers in the Orange County Klavern. Although members of the Ku Klux Klan were suspected of the crime, the people responsible were never brought to trial.

(Source: Wikipedia)

by Gary Corsair (no photo)

by Gary Corsair (no photo)

Folks, I am providing a link to one of our Civil Rights threads on Brown vs Board of Education - some great books listed by the History Book Club.

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

"Thurgood Marshall Nominated to Supreme Court" (Washington DC, 6/13/1967)"

https://youtu.be/ri0NwkwkkoE

Source: UCLAFilmTVArchive

https://youtu.be/ri0NwkwkkoE

Source: UCLAFilmTVArchive

message 12:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Mar 30, 2016 12:17PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Thurgood Marshall’s Defense of Death Penalty Cases

Author Gilbert King describes the case of four young African American men charged with the rape of a white woman in Florida in 1949, based on his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America. Thurgood Marshall and other lawyers from the NAACP assumed responsibility for the defense.

Link: https://youtu.be/bCgkFYZn7pk

Yale Courses

Source; Youtube

Author Gilbert King describes the case of four young African American men charged with the rape of a white woman in Florida in 1949, based on his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America. Thurgood Marshall and other lawyers from the NAACP assumed responsibility for the defense.

Link: https://youtu.be/bCgkFYZn7pk

Yale Courses

Source; Youtube

Thurgood Marshall: Biography, Supreme Court Justice, Civil Rights Attorney, Quotes (1993)

Thurgood Marshall: Biography, Supreme Court Justice, Civil Rights Attorney, Quotes (1993)Below is a link to an interview of the authors of Thurgood Marshall: Rebel at the Bar, Warrior on the Bench, Michael Davis and Hunter J. Clark.

https://youtu.be/VBBiogcDokg

Source: YouTube (Book TV, CSPAN-2)

by Michael Davis (no photo) and Hunter R. Clark (no photo)

by Michael Davis (no photo) and Hunter R. Clark (no photo)

Fearless Attorney Most Hated Man at Tenn. Trial

Fearless Attorney Most Hated Man at Tenn. TrialHistorical Newspaper Article

I came across this interesting article from the October 5, 1946 edition of The Afro American that is covering the 1946 Columbia Riot trial in Columbia, Tennessee. The article is specific to NAACP lawyer Maurice Weaver, one of Marshall's fellow attorneys in the trial and helped Marshall flee town when it was over. See Chapter One Mink Slide of Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America.

https://news.google.com/newspapers?ni...

Charles Hamilton Houston

Charles Hamilton Houston

Charles Hamilton Houston (September 3, 1895-April 22, 1950) was a black lawyer who helped play a role in dismantling the Jim Crow laws and helped train future Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall. Known as "The Man Who Killed Jim Crow", he played a role in nearly every civil rights case before the Supreme Court between 1930 and Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Houston's brilliant plan to attack and defeat Jim Crow segregation by using the inequality of the "separate but equal" doctrine (from the Supreme Court's Plessy v. Ferguson decision) as it pertained to public education in the United States was the master stroke that brought about the landmark Brown decision.

Born in Washington, D.C., Houston prepared for college at Dunbar High School in Washington, then matriculated to Amherst College, graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1915.opps

From 1915 to 1917, Houston taught English at Howard University. From 1917 to 1919, he was a First Lieutenant in the United States Infantry, based in Fort Meade, Maryland. Houston later wrote:

"The hate and scorn showered on us Negro officers by our fellow Americans convinced me that there was no sense in my dying for a world ruled by them. I made up my mind that if I got through this war I would study law and use my time fighting for men who could not strike back."

In the fall of 1919, he entered Harvard Law School, earning his Bachelor of Laws degree 1922 and his Doctor of Laws degree in 1923. In 1922, he became the first African-American to serve as an editor of the Harvard Law Review.

After studying at the University of Madrid in 1924, Houston was admitted to the District of Columbia bar that same year and joined forces with his father in practicing law. Beginning in the 1930s, Houston served as the first special counsel to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and therefore was involved with the majority of civil rights cases from then until his death on April 22, 1950.

He later joined Howard Law School's faculty, establishing a long-standing relationship between Howard and Harvard law schools. While at Howard, he was a mentor to Thurgood Marshall, who argued Brown v. Board of Education and was later appointed to the Supreme Court.

Houston used his post at Howard to recruit talented students into the NAACP's legal efforts (among them Marshall and Oliver Hill, the first- and second-ranked students in the class of 1933, both of whom were drafted into organization's legal battles by Houston).

By the mid-1930s, two separate anti-lynching bills backed by the NAACP had failed to gain passage, and the organization had won a landmark victory against restrictive housing covenants that excluded blacks from particular neighborhoods only to see the achievement undermined by subsequent legal precedents.

Houston struck upon the idea that unequal education was the Achilles heel of Jim Crow. By demonstrating the failure of states to even try to live up to the 1896 rule of "separate but equal," Houston hoped to finally overturn the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling that had given birth to that phrase.

His target was broad, but the evidence was numerous. Southern states collectively spent less than half of what was allotted for white students on education for blacks; there were even greater disparities in individual school districts. Black schools were equipped with castoff supplies from white ones and built with inferior materials. Black facilities appeared to be part of a crude segregationist satire - a design to make black education a contradiction in terms.

Houston designed a strategy of attacking segregation in law schools - forcing states to either create costly parallel law schools or integrate the existing ones. The strategy had hidden benefits: since law students were predominantly male, Houston sought to neutralize the age-old argument that allowing blacks to attend white institutions would lead to miscegenation, or "race-mixing". He also reasoned that judges deciding the cases might be more sympathetic to plaintiffs who were pursuing careers in law. Finally, by challenging segregation in graduate schools, the NAACP lawyers would bypass the inflammatory issue of miscegenation among young children.

The successful ruling handed down in the Brown decision was testament to the master strategy formulated by Houston.

Houston was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha, the first intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternity established for African Americans.

Houston was posthumously awarded the NAACP's Spingarn Medal in 1950 and, in 1958, the main building of the Howard University School of Law was dedicated as Charles Hamilton Houston Hall. His importance became more broadly known through the success of Thurgood Marshall and after the 1983 publication of Genna Rae McNeil's Groundwork: Charles Hamilton Houston and the Struggle for Civil Rights.

Houston is the namesake of the Charles Houston Bar Association and the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School, which opened in the fall of 2005. In addition, there is a professorship at Harvard Law named after him. Currently, the Dean of Harvard Law School, Elena Kagan, is also the Charles Hamilton Houston Professor of Law.

(Source: NAACP.org)

More:

by

by

Rawn James Jr.

Rawn James Jr. by Genna Rae McNeil (no photo)

by Genna Rae McNeil (no photo)

The NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund (NAACP LDF)

The NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund (NAACP LDF)The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF) is the country’s first and foremost civil and human rights law firm. Founded in 1940 under the leadership of Thurgood Marshall, who subsequently became the first African-American U.S. Supreme Court Justice, LDF was launched at a time when the nation’s aspirations for equality and due process of law were stifled by widespread state-sponsored racial inequality. From that era to the present, LDF’s mission has always been transformative: to achieve racial justice, equality, and an inclusive society.

As the legal arm of the civil rights movement, LDF has a tradition of expert legal advocacy in the Supreme Court and other courts across the nation. LDF’s victories established the foundations for the civil rights that all Americans enjoy today. In its first two decades, LDF undertook a coordinated legal assault against officially enforced public school segregation. This campaign culminated in Brown v. Board of Education 1, the landmark Supreme Court decision in 1954 that has been described as “the most important American governmental act of any kind since the Emancipation Proclamation.” The Court’s unanimous decision overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine of legally sanctioned discrimination, widely known as Jim Crow.

In the face of fierce and often violent “massive resistance” to public school desegregation, LDF was forced to sue hundreds of school districts across the country to vindicate Brown’s promise. It was not until LDF’s subsequent victories in cases such as Cooper v. Aaron (1958)2, Green v. County School Board (1968)3,and Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg (1971)4, that the Supreme Court issued mandates that ultimately required all vestiges of desegregation to be eliminated “root and branch.” In more recent decades, LDF has remained at the forefront of the ongoing struggle to ensure a high-quality and equitable opportunity to learn for all of our nation’s youth. For instance, LDF served as lead counsel to African-American and Latino students who intervened in litigation leading up to the Supreme Court’s 2003 decision in Grutter v. Bollinger5, which sanctioned race-conscious university admissions policies to obtain the educational benefits of a diverse student body.

LDF’s crusade against racial discrimination has not been limited to public education. As a result of LDF’s litigation in the 1940s-1960s, the Supreme Court overturned state-sanctioned segregation of public buildings, parks and recreation facilities, hospitals, and restaurants. Many of these victories resulted from LDF’s determined representation of civil rights movement leaders, including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and countless grassroots activists who were arrested for participating in freedom rides, demonstrations, and marches to protest entrenched racial discrimination throughout the country. In Hamm v. City of Rock Hill (1964)6 for example, LDF persuaded the Supreme Court to dismiss all prosecutions of demonstrators who had participated in civil rights sit-ins.

LDF has also consistently fought to eliminate barriers to full political participation by all Americans in our nation’s democratic processes. In 1943, Thurgood Marshall successfully persuaded the Supreme Court to rule in Smith v. Allwright 7 that Texas’s refusal to allow African-Americans to vote in the Democratic primary election violated the 15th Amendment. In 1965, LDF litigated to ensure against disruptions of Dr. King’s voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama shortly after the notorious “Bloody Sunday” episode, when marchers were beaten by policemen as they tried to cross the Edmund Pettis Bridge. These events galvanized passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, one of our nation’s core federal civil rights statutes, which LDF and other advocates have repeatedly used to safeguard citizens’ voting rights and ensure more inclusive democratic governance.

See the source link below for the full article.

(Source: LDF)

More:

by

by

Michelle Alexander

Michelle Alexander by

by

Bryan Stevenson

Bryan Stevenson

The Spingarn Medal

The Spingarn Medal

The Spingarn Medal

Awarded annually for the highest achievement of an American of African descent.

THE SPINGARN MEDAL was instituted in 1914 by the late J.E. Spingarn (then Chairman of the NAACP Board of Directors), who gave annually until his death in 1939, a gold medal to be awarded for the highest or noblest achievement by an American Negro during the preceding year or years. A fund sufficient to continue the award was set up by his will to perpetuate this award.

PURPOSE

The purpose of the medal is twofold: first to call the attention of the American people to the existence of distinguished merit and achievement among Americans of African descent and secondly to serve as a reward for such achievement, and as a stimulus to the ambition of youth of color.

CONDITIONS

The medal is presented annually to the man or woman of African descent and American citizenship who shall have made the highest achievement during the preceding year or years in any honorable field of human endeavor. The Committee of Awards is bound by no burdensome restrictions, but may decide for itself each year what particular act or achievement deserves the highest acclaim. The choice is not limited to any one field, whether of intellectual, spiritual, physical, scientific, artistic, commercial, educational or other endeavor. It is intended primarily that the medal shall be for the highest achievement in the preceding year. If no achievement in one year seems to merit it, the Committee may award it for work achieved in preceding years, or may withhold it. The medal is usually presented to the winner at the annual convention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the presentation speech is delivered by a distinguished citizen.

A nine person Committee of Award is selected by the NAACP Board of Directors. The Committee's decision is final in all matters affecting the award.

(Source: NACCP.org)

More:

by Louis Haber (no photo)

by Louis Haber (no photo)

Thurgood Marshall Full Episode

Thurgood Marshall Full EpisodeThurgood Marshall, the crusading attorney and civil rights activist who led the fight against school desegregation, became the first African-American to sit on the U.S. Supreme Court. The following video describes Thurgood Marshall's early years and his career to the Supreme Court.

https://youtu.be/pw6s89Nmyv4

Source: YouTube (Biography.com)

The following link is for an 2011 HBO Best from Hollywood movie about Thurgood Marshall:

The following link is for an 2011 HBO Best from Hollywood movie about Thurgood Marshall:Thurgood

Lawrence Fishburn gives a powerful portrayal of Thurgood Marshall delivering a speech at Howard University in which Marshall tells the story of his life.

https://youtu.be/XAWOl8jT64M

Source: YouTube

"The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund is simply the best civil rights law firm in American history." -- President Obama

LDF Website

Thurgood Marshall founded LDF in 1940 and served as its first Director-Counsel. He was the architect of the legal strategy that ended the country’s official policy of segregation. Marshall was the first African American to serve on the Supreme Court on which he served as Associate Justice from 1967-1991 after he was successfully nominated by President Johnson. He retired from the bench in 1991 and passed away on January 24, 1993 in Washington DC at the age of 84. Civil rights and social change came about through meticulous and persistent litigation efforts, at the forefront of which stood Thurgood Marshall and the Legal Defense Fund. Through the courts, he ensured that Blacks enjoyed the rights and responsibilities of full citizenship.

Marshall was born on July 2, 1908 in Baltimore, Maryland to William Marshall, railroad porter, who later worked on the staff of Gibson Island Club, a white-only country club and Norma Williams, a school teacher. One of his great-grandfathers had been taken as a slave from the Congo to Maryland where he was eventually freed. Marshall graduated from Lincoln University in 1930 and applied to University of Maryland Law School – he was denied admission because the school was still segregated at that time. So Marshall matriculated to Howard University Law School where he graduated first in his class and met his mentor, Charles Hamilton Huston, with whom he enjoyed a lifelong friendship. In an interview published in 1992 in the American Bar Association Journal, Marshall wrote that "Charlie Houston insisted that we be social engineers rather than lawyers,” a mantra that he upheld and personified.

Immediately after graduation, Marshall opened a law office in Baltimore and in the early 1930s, he represented the local NAACP chapter in a successful lawsuit that challenged the University of Maryland Law School over its segregation policy. In addition, he successfully brought lawsuits that integrated other state universities. In 1936, Marshall became the NAACP’s chief legal counsel. The NAACP’s initial goal was to funnel equal resources to black schools. Marshall successfully challenged the board to only litigate cases that would address the heart of segregation.

After founding the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in 1940, Marshall became the key strategist in the effort to end racial segregation, in particular meticulously challenging Plessy v. Ferguson, the Court-sanctioned legal doctrine that called for “separate but equal” structures for white and blacks. Marshall won a series of court decisions that gradually struck down that doctrine, ultimately leading to Brown v. Board of Education, which he argued before the Supreme Court in 1952 and 1953, finally overturning “separate but equal” and acknowledging that segregation greatly diminished students’ self-esteem. Asked by Justice Felix Frankfurter during the argument what he meant by "equal," Mr. Marshall replied, "Equal means getting the same thing, at the same time, and in the same place."

In 1957 LDF, led by Marshall, became an entirely separate entity from the NAACP with its own leadership and board of directors and has remained a separate organization to this day.

As a lead legal architect of the civil rights movement, Marshall constantly traveled to small, dusty, scorching courtrooms throughout the south. At one point, he oversaw as many as 450 simultaneous cases. Among other major victories, he successfully challenged a whites-only primary elections in Texas in addition to a case in which the Supreme Court declared that restrictive covenants that barred blacks from buying or renting homes could not be enforced in state courts.

In 1961, President Kennedy nominated Marshall to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit in which he wrote 112 opinions, none of which was overturned on appeal. Four years later, he was appointed by President Johnson to be solicitor general and in 1967 President Johnson nominated him to the Supreme Court to which he commented: "I have a lifetime appointment and I intend to serve it. I expect to die at 110, shot by a jealous husband." Of the appointment President Johnson later that Marshall’s nomination was "the right thing to do, the right time to do it, the right man and the right place."

As a Supreme Court Justice, he became increasingly dismayed and disappointed as the court’s majority retreated from remedies he felt were necessary to address remnants of Jim Crow. In his Bakke dissent, he wrote: "In light of the sorry history of discrimination and its devastating impact on the lives of Negroes, bringing the Negro into the mainstream of American life should be a state interest of the highest order. To fail to do so is to insure that America will forever remain a divided society."

In particular, Marshall fervently dissented in cases in which the Supreme Court upheld death sentences; he wrote over 150 opinions dissenting from cases in which the Court refused to hear death penalty appeals. Among Marshall’s salient majority opinions for the Supreme Court were: Amalgamated Food Employees Union v. Logan Valley Plaza, in 1968, which determined that a mall was “public forum” and unable to exclude picketers; Stanley v. Georgia, in 1969, held that pornography, when owned privately, could not be prosecuted. "If the First Amendment means anything, it means that a state has no business telling a man, sitting alone in his own house, what books he may read or what films he may watch”; and Bounds v. Smith, which held that state prison systems are must provide their inmates with "adequate law libraries or adequate assistance from persons trained in the law." Marshall’s status as a pillar of the Civil Rights Movement is confirmed and upheld by LDF and other organizations who strive to uphold the principals of civil rights and racial justice. His legacy cannot be overstated: he worked diligently and tirelessly to end what was America’s official doctrine of separate-but-equal.

Source: LDF website

Link to the above: http://www.naacpldf.org/thurgood-mars...

Brown versus Board of Education:

http://www.naacpldf.org/case/brown-v-...

A shocking paragraph from the above:

"Even today, the work of Brown is far from finished . Over 200 school desegregation cases remain open on federal court dockets; LDF alone has nearly 100 of these cases. Recent Supreme Court decisions have made it harder to achieve and maintain school desegregation. As a result of these developments and other factors, public school children are more racially isolated now than at any point in the past four decades. This backsliding makes it even more critical for LDF to continue defending the principles articulated in Brown and leading the ongoing struggle to provide an equal opportunity to learn for children in every one of our nation’s classrooms. As then Senator Obama observed in a 2008 speech in Philadelphia, “segregated schools were, and are, inferior schools 50 years after Brown v. Board of Education – and the inferior education they provided, then and now, helps explain the pervasive achievement gap between today’s black and white students.”

LDF Website

Thurgood Marshall founded LDF in 1940 and served as its first Director-Counsel. He was the architect of the legal strategy that ended the country’s official policy of segregation. Marshall was the first African American to serve on the Supreme Court on which he served as Associate Justice from 1967-1991 after he was successfully nominated by President Johnson. He retired from the bench in 1991 and passed away on January 24, 1993 in Washington DC at the age of 84. Civil rights and social change came about through meticulous and persistent litigation efforts, at the forefront of which stood Thurgood Marshall and the Legal Defense Fund. Through the courts, he ensured that Blacks enjoyed the rights and responsibilities of full citizenship.

Marshall was born on July 2, 1908 in Baltimore, Maryland to William Marshall, railroad porter, who later worked on the staff of Gibson Island Club, a white-only country club and Norma Williams, a school teacher. One of his great-grandfathers had been taken as a slave from the Congo to Maryland where he was eventually freed. Marshall graduated from Lincoln University in 1930 and applied to University of Maryland Law School – he was denied admission because the school was still segregated at that time. So Marshall matriculated to Howard University Law School where he graduated first in his class and met his mentor, Charles Hamilton Huston, with whom he enjoyed a lifelong friendship. In an interview published in 1992 in the American Bar Association Journal, Marshall wrote that "Charlie Houston insisted that we be social engineers rather than lawyers,” a mantra that he upheld and personified.

Immediately after graduation, Marshall opened a law office in Baltimore and in the early 1930s, he represented the local NAACP chapter in a successful lawsuit that challenged the University of Maryland Law School over its segregation policy. In addition, he successfully brought lawsuits that integrated other state universities. In 1936, Marshall became the NAACP’s chief legal counsel. The NAACP’s initial goal was to funnel equal resources to black schools. Marshall successfully challenged the board to only litigate cases that would address the heart of segregation.

After founding the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in 1940, Marshall became the key strategist in the effort to end racial segregation, in particular meticulously challenging Plessy v. Ferguson, the Court-sanctioned legal doctrine that called for “separate but equal” structures for white and blacks. Marshall won a series of court decisions that gradually struck down that doctrine, ultimately leading to Brown v. Board of Education, which he argued before the Supreme Court in 1952 and 1953, finally overturning “separate but equal” and acknowledging that segregation greatly diminished students’ self-esteem. Asked by Justice Felix Frankfurter during the argument what he meant by "equal," Mr. Marshall replied, "Equal means getting the same thing, at the same time, and in the same place."

In 1957 LDF, led by Marshall, became an entirely separate entity from the NAACP with its own leadership and board of directors and has remained a separate organization to this day.

As a lead legal architect of the civil rights movement, Marshall constantly traveled to small, dusty, scorching courtrooms throughout the south. At one point, he oversaw as many as 450 simultaneous cases. Among other major victories, he successfully challenged a whites-only primary elections in Texas in addition to a case in which the Supreme Court declared that restrictive covenants that barred blacks from buying or renting homes could not be enforced in state courts.

In 1961, President Kennedy nominated Marshall to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit in which he wrote 112 opinions, none of which was overturned on appeal. Four years later, he was appointed by President Johnson to be solicitor general and in 1967 President Johnson nominated him to the Supreme Court to which he commented: "I have a lifetime appointment and I intend to serve it. I expect to die at 110, shot by a jealous husband." Of the appointment President Johnson later that Marshall’s nomination was "the right thing to do, the right time to do it, the right man and the right place."

As a Supreme Court Justice, he became increasingly dismayed and disappointed as the court’s majority retreated from remedies he felt were necessary to address remnants of Jim Crow. In his Bakke dissent, he wrote: "In light of the sorry history of discrimination and its devastating impact on the lives of Negroes, bringing the Negro into the mainstream of American life should be a state interest of the highest order. To fail to do so is to insure that America will forever remain a divided society."

In particular, Marshall fervently dissented in cases in which the Supreme Court upheld death sentences; he wrote over 150 opinions dissenting from cases in which the Court refused to hear death penalty appeals. Among Marshall’s salient majority opinions for the Supreme Court were: Amalgamated Food Employees Union v. Logan Valley Plaza, in 1968, which determined that a mall was “public forum” and unable to exclude picketers; Stanley v. Georgia, in 1969, held that pornography, when owned privately, could not be prosecuted. "If the First Amendment means anything, it means that a state has no business telling a man, sitting alone in his own house, what books he may read or what films he may watch”; and Bounds v. Smith, which held that state prison systems are must provide their inmates with "adequate law libraries or adequate assistance from persons trained in the law." Marshall’s status as a pillar of the Civil Rights Movement is confirmed and upheld by LDF and other organizations who strive to uphold the principals of civil rights and racial justice. His legacy cannot be overstated: he worked diligently and tirelessly to end what was America’s official doctrine of separate-but-equal.

Source: LDF website

Link to the above: http://www.naacpldf.org/thurgood-mars...

Brown versus Board of Education:

http://www.naacpldf.org/case/brown-v-...

A shocking paragraph from the above:

"Even today, the work of Brown is far from finished . Over 200 school desegregation cases remain open on federal court dockets; LDF alone has nearly 100 of these cases. Recent Supreme Court decisions have made it harder to achieve and maintain school desegregation. As a result of these developments and other factors, public school children are more racially isolated now than at any point in the past four decades. This backsliding makes it even more critical for LDF to continue defending the principles articulated in Brown and leading the ongoing struggle to provide an equal opportunity to learn for children in every one of our nation’s classrooms. As then Senator Obama observed in a 2008 speech in Philadelphia, “segregated schools were, and are, inferior schools 50 years after Brown v. Board of Education – and the inferior education they provided, then and now, helps explain the pervasive achievement gap between today’s black and white students.”

message 22:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Apr 02, 2016 06:00PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

I thought that this photo might be interesting for the group:

LDF Attorneys on the steps of the Supreme Court: (Left to Right) John Scott, James Nabrit, Spottswood Robinson, Frank Reeves, Jack Greenberg, Thurgood Marshall, Louis Redding, U. Simpson Tate, George Hayes.

1933

Thurgood Marshall graduates first in his class from Howard University’s School of Law. Oliver Hill, also a classmate and one of the Brown counsels, graduates second. Marshall and Hill were both mentored by the Law School’s vice-dean Charles Hamilton Houston.

1934

Houston joins the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) as part- time counsel.

1935

After having been denied admittance to the University of Maryland Law School, Marshall wins a case in the Maryland Court of Appeals against the Law School, which gains admission for Donald Murray, the first black applicant to a white southern law school.

1936

Marshall joins the NAACP’s legal staff.

1938

Marshall succeeds Houston as special counsel. Houston returns to his Washington, D.C. law practice but remains counsel with the NAACP.

1938

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada The U.S. Supreme Court invalidates state laws that required African-American students to attend out-of-state graduate schools to avoid admitting them to their states’ all-white facilities or building separate graduate schools for them.

1940

Marshall writes the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund’s corporate charter and becomes its first director and chief counsel.

1940

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk A federal appeals court orders that African- American teachers be paid salaries equal to those of white teachers.

1948

Sipuel v. Oklahoma State Regents The Supreme Court rules that a state cannot bar an African- American student from its all-white law school on the ground that she had not requested the state to provide a separate law school for black students.

1949

Jack Greenberg graduates from Columbia Law School and joins LDF as a staff attorney.

1950

Charles Hamilton Houston dies. He was the chief architect of the NAACP LDF legal strategy for

racial equality, Thurgood Marshall’s teacher and mentor, and Dean of Howard University’s Law School.

1950

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents The Supreme Court holds that an African-American student admitted to a formerly all white graduate school could not be subjected to practices of segregation that interfered with meaningful classroom instruction and interaction with other students, such as making a student sit in the classroom doorway, isolated from the professor and other students.

1950

Sweatt v. Painter

The Supreme Court rules that a separate law school hastily established for black students to prevent their having to be admitted to the previously all-white University of Texas School of Law could not provide a legal education “equal” to that available to white students. The Court orders the admission of Heman Marion Sweatt to the University of Texas Law School.

1954 Brown v. Board of Education

The Supreme Court rules that racial segregation in public schools violates the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees equal protection, and the Fifth Amendment, which guarantees due process.

This landmark case overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine that underpinned legal segregation.

Attorneys for the plaintiffs in the five cases that comprised the Supreme Court case were:

Thurgood Marshall, Director-Counsel, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

Harold Boulware - Briggs v. Elliott (South Carolina)

Jack Greenberg, Louis L. Redding - Gebhart v. Belton (Delaware)

Robert L. Carter, Charles S. Scott - Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (Kansas)

Oliver M. Hill, Spottswood W. Robinson III - Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (Virginia)

James M. Nabrit, Jr., George E. C. Hayes - Bolling v. Sharpe (District of Columbia)

Attorneys Of Counsel: Charles L. Black, Jr., Elwood H. Chisolm, William T. Coleman, Jr., Charles T. Duncan, William R. Ming, Jr., Constance Baker Motley, David E. Pinsky, Frank D. Reeves, John Scott, and Jack B. Weinstein.

Source: - The Winding Road to Brown - http://www.naacpldf.org/files/Excerpt...

LDF Attorneys on the steps of the Supreme Court: (Left to Right) John Scott, James Nabrit, Spottswood Robinson, Frank Reeves, Jack Greenberg, Thurgood Marshall, Louis Redding, U. Simpson Tate, George Hayes.

1933

Thurgood Marshall graduates first in his class from Howard University’s School of Law. Oliver Hill, also a classmate and one of the Brown counsels, graduates second. Marshall and Hill were both mentored by the Law School’s vice-dean Charles Hamilton Houston.

1934

Houston joins the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) as part- time counsel.

1935

After having been denied admittance to the University of Maryland Law School, Marshall wins a case in the Maryland Court of Appeals against the Law School, which gains admission for Donald Murray, the first black applicant to a white southern law school.

1936

Marshall joins the NAACP’s legal staff.

1938

Marshall succeeds Houston as special counsel. Houston returns to his Washington, D.C. law practice but remains counsel with the NAACP.

1938

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada The U.S. Supreme Court invalidates state laws that required African-American students to attend out-of-state graduate schools to avoid admitting them to their states’ all-white facilities or building separate graduate schools for them.

1940

Marshall writes the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund’s corporate charter and becomes its first director and chief counsel.

1940

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk A federal appeals court orders that African- American teachers be paid salaries equal to those of white teachers.

1948

Sipuel v. Oklahoma State Regents The Supreme Court rules that a state cannot bar an African- American student from its all-white law school on the ground that she had not requested the state to provide a separate law school for black students.

1949

Jack Greenberg graduates from Columbia Law School and joins LDF as a staff attorney.

1950

Charles Hamilton Houston dies. He was the chief architect of the NAACP LDF legal strategy for

racial equality, Thurgood Marshall’s teacher and mentor, and Dean of Howard University’s Law School.

1950

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents The Supreme Court holds that an African-American student admitted to a formerly all white graduate school could not be subjected to practices of segregation that interfered with meaningful classroom instruction and interaction with other students, such as making a student sit in the classroom doorway, isolated from the professor and other students.

1950

Sweatt v. Painter

The Supreme Court rules that a separate law school hastily established for black students to prevent their having to be admitted to the previously all-white University of Texas School of Law could not provide a legal education “equal” to that available to white students. The Court orders the admission of Heman Marion Sweatt to the University of Texas Law School.

1954 Brown v. Board of Education

The Supreme Court rules that racial segregation in public schools violates the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees equal protection, and the Fifth Amendment, which guarantees due process.

This landmark case overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine that underpinned legal segregation.

Attorneys for the plaintiffs in the five cases that comprised the Supreme Court case were:

Thurgood Marshall, Director-Counsel, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

Harold Boulware - Briggs v. Elliott (South Carolina)

Jack Greenberg, Louis L. Redding - Gebhart v. Belton (Delaware)

Robert L. Carter, Charles S. Scott - Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (Kansas)

Oliver M. Hill, Spottswood W. Robinson III - Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (Virginia)

James M. Nabrit, Jr., George E. C. Hayes - Bolling v. Sharpe (District of Columbia)

Attorneys Of Counsel: Charles L. Black, Jr., Elwood H. Chisolm, William T. Coleman, Jr., Charles T. Duncan, William R. Ming, Jr., Constance Baker Motley, David E. Pinsky, Frank D. Reeves, John Scott, and Jack B. Weinstein.

Source: - The Winding Road to Brown - http://www.naacpldf.org/files/Excerpt...

message 23:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Apr 02, 2016 06:20PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

LDF Director-Counsels

Thurgood Marshall - 1940 - 1961

Jack Greenberg - 1961 - 1984

Julius Chambers - 1984 - 1993

Elaine Jones - 1993 - 2004

More next post:

Source - LDF site

Link to articles on all of the above:

http://www.naacpldf.org/history

Thurgood Marshall - 1940 - 1961

Jack Greenberg - 1961 - 1984

Julius Chambers - 1984 - 1993

Elaine Jones - 1993 - 2004

More next post:

Source - LDF site

Link to articles on all of the above:

http://www.naacpldf.org/history

message 24:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Apr 02, 2016 06:24PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

LDF Director Counsels

Ted Shaw - 2004 - 2008

John Payton - 2008 - 2012

Sherrilyn Ifill - 2012 - Present

Source - LDF site

Link to articles on all of the above:

http://www.naacpldf.org/history

Ted Shaw - 2004 - 2008

John Payton - 2008 - 2012

Sherrilyn Ifill - 2012 - Present

Source - LDF site

Link to articles on all of the above:

http://www.naacpldf.org/history

message 25:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Apr 02, 2016 06:46PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Celebrating 75 Years of LDF - Video

On November 4, 2015, over 750 supporters joined the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (“LDF”) at the New York Hilton at its 75th Anniversary National Equal Justice Award Dinner honoring former Attorney General Eric H. Holder and two international foundations on November 4, 2015. The occasion served as a celebration of LDF's work, as well as a call to action to rally around the broad racial justice agenda that the organization has advanced. Dinner guests were treated to a performance by members of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, dynamic speakers, and this inspiring film screening depicting LDF's seventy-five year history.

Video: https://youtu.be/wFDq4ooyj_0

Source: Youtube

On November 4, 2015, over 750 supporters joined the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (“LDF”) at the New York Hilton at its 75th Anniversary National Equal Justice Award Dinner honoring former Attorney General Eric H. Holder and two international foundations on November 4, 2015. The occasion served as a celebration of LDF's work, as well as a call to action to rally around the broad racial justice agenda that the organization has advanced. Dinner guests were treated to a performance by members of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, dynamic speakers, and this inspiring film screening depicting LDF's seventy-five year history.

Video: https://youtu.be/wFDq4ooyj_0

Source: Youtube

message 26:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Apr 02, 2016 06:46PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Samuel L. Jackson asks, "What Would Your World Look Like Without LDF?"

In this year's LDF's 28th Annual National Equal Justice Award Dinner (NEJAD) video Academy award nominee Samuel L. Jackson asks, "what would your world look like without LDF?" See the video featuring and Jackson and highlighting LDF's work.

Video: https://youtu.be/vWenxx1rZe0

Source: Youtube

In this year's LDF's 28th Annual National Equal Justice Award Dinner (NEJAD) video Academy award nominee Samuel L. Jackson asks, "what would your world look like without LDF?" See the video featuring and Jackson and highlighting LDF's work.

Video: https://youtu.be/vWenxx1rZe0

Source: Youtube

message 27:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Apr 02, 2016 06:50PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Thurgood Marshall -On the Supreme Court

In 1967 Thurgood Marshall began his tenure as the first African American Supreme Court Justice.

Video: https://youtu.be/LMAvSZk53SA

Source: Youtube

In 1967 Thurgood Marshall began his tenure as the first African American Supreme Court Justice.

Video: https://youtu.be/LMAvSZk53SA

Source: Youtube

message 28:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Apr 02, 2016 07:27PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Constance Baker Motley: Working for Thurgood Marshall

Video: https://youtu.be/PrnnT_iuuEQ

Source: Youtube

Note: One very interesting fact that Motley discusses in this video is how the NAACP got separated from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund or the LDF as it is called.

At the beginning - the NAACP and NAACP Legal Defense Fund were one and the same.

Motley explains that "in 1956 as a part of the Southern massive resistance to the NAACP efforts - that the Southerners got the Internal Revenue Service to threaten to pull the tax exemptions of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund because they stated that the NAACP was engaged in legislative activity as well as legal".

So that is why the two organizations had to separate and it was about 56 or 58 according to Motley - "that Thurgood became the head of the legal effort LDF and his assistance assumed the role of the head of the NAACP."

Comment: Very interesting.

Who is she: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constan...

Another interesting tidbit about Thurgood - he was an excellent chef - and could cook a mean stew.

Video: https://youtu.be/PrnnT_iuuEQ

Source: Youtube

Note: One very interesting fact that Motley discusses in this video is how the NAACP got separated from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund or the LDF as it is called.

At the beginning - the NAACP and NAACP Legal Defense Fund were one and the same.

Motley explains that "in 1956 as a part of the Southern massive resistance to the NAACP efforts - that the Southerners got the Internal Revenue Service to threaten to pull the tax exemptions of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund because they stated that the NAACP was engaged in legislative activity as well as legal".

So that is why the two organizations had to separate and it was about 56 or 58 according to Motley - "that Thurgood became the head of the legal effort LDF and his assistance assumed the role of the head of the NAACP."

Comment: Very interesting.

Who is she: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constan...

Another interesting tidbit about Thurgood - he was an excellent chef - and could cook a mean stew.

Some Interesting Districting Articles:

Response:

It had to do with districting:

See following article:

https://americanvision.org/3918/the-o...

Another article:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/postev...

Another article:

http://siftingreality.com/2013/07/09/...

Response:

It had to do with districting:

See following article:

https://americanvision.org/3918/the-o...

Another article:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/postev...

Another article:

http://siftingreality.com/2013/07/09/...

message 30:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Apr 02, 2016 08:35PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Response on Membership numbers of NAACP

These are just extracts which address membership numbers - started with 4 (1909) - then 60 (same time period), then the NAACP membership grew rapidly, from around 9,000 in 1917 to around 90,000 in 1919, with more than 300 local branches. throughout the 1940s the NAACP saw enormous growth in membership, recording roughly 600,000 members by 1946. It now has a half million members.

EXTRACTS FROM HISTORY

Founding group

Founded February 12, 1909, the NAACP is the nation's oldest, largest and most widely recognized grassroots–based civil rights organization. Its more than half-million members and supporters throughout the United States and the world are the premier advocates for civil rights in their communities, conducting voter mobilization and monitoring equal opportunity in the public and private sectors.

The NAACP was formed partly in response to the continuing horrific practice of lynching and the 1908 race riot in Springfield, the capital of Illinois and resting place of President Abraham Lincoln.

Appalled at the violence that was committed against blacks, a group of white liberals that included Mary White Ovington and Oswald Garrison Villard, both the descendants of abolitionists, William English Walling and Dr. Henry Moscowitz issued a call for a meeting to discuss racial justice.

Some 60 people, seven of whom were African American (including W. E. B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell), signed the call, which was released on the centennial of Lincoln's birth.

Other early members included Joel and Arthur Spingarn, Josephine Ruffin, Mary Talbert, Inez Milholland, Jane Addams, Florence Kelley, Sophonisba Breckinridge, John Haynes Holmes, Mary McLeod Bethune, George Henry White, Charles Edward Russell, John Dewey, William Dean Howells, Lillian Wald, Charles Darrow, Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, and Fanny Garrison Villard.

Echoing the focus of Du Bois' Niagara Movement began in 1905, the NAACP's stated goal was to secure for all people the rights guaranteed in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution, which promised an end to slavery, the equal protection of the law, and universal adult male suffrage, respectively.

The NAACP's principal objective is to ensure the political, educational, social and economic equality of minority group citizens of United States and eliminate race prejudice. The NAACP seeks to remove all barriers of racial discrimination through the democratic processes.

The NAACP established its national office in New York City in 1910 and named a board of directors as well as a president, Moorfield Storey, a white constitutional lawyer and former president of the American Bar Association. The only African American among the organization's executives, Du Bois was made director of publications and research and in 1910 established the official journal of the NAACP, The Crisis.

Growth

With a strong emphasis on local organizing, by 1913 the NAACP had established branch offices in such cities as Boston, Massachusetts; Baltimore, Maryland; Kansas City, Missouri; Washington, D.C.; Detroit, Michigan; and St. Louis, Missouri.

Joel Spingarn, one of the NAACP founders, was a professor of literature and formulated much of the strategy that led to the growth of the organization.

He was elected board chairman of the NAACP in 1915 and served as president from 1929-1939.

A series of early court battles, including a victory against a discriminatory Oklahoma law that regulated voting by means of a grandfather clause (Guinn v. United States, 1910), helped establish the NAACP's importance as a legal advocate.

The fledgling organization also learned to harness the power of publicity through its 1915 battle against D. W. Griffith's inflammatory Birth of a Nation, a motion picture that perpetuated demeaning stereotypes of African Americans and glorified the Ku Klux Klan.

NAACP membership grew rapidly, from around 9,000 in 1917 to around 90,000 in 1919, with more than 300 local branches.

Writer and diplomat James Weldon Johnson became the Association's first black secretary in 1920, and Louis T. Wright, a surgeon, was named the first black chairman of its board of directors in 1934.

The NAACP waged a 30-year campaign against lynching, among the Association's top priorities. After early worries about its constitutionality, the NAACP strongly supported the federal Dyer Bill, which would have punished those who participated in or failed to prosecute lynch mobs.

Though the bill would pass the U.S. House of Representatives, the Senate never passed the bill, or any other anti-lynching legislation. Most credit the resulting public debate—fueled by the NAACP report ―Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889-1919‖—with drastically decreasing the incidence of lynching.

Johnson stepped down as secretary in 1930 and was succeeded by Walter F. White. White was instrumental not only in his research on lynching (in part because, as a very fair-skinned African American, he had been able to infiltrate white groups), but also in his successful block of segregationist Judge John J. Parker's nomination by President Herbert Hoover to the U.S. Supreme Court.

White presided over the NAACP's most productive period of legal advocacy. In 1930 the association commissioned the Margold Report, which became the basis for the successful reversal of the separate-but- equal doctrine that had governed public facilities since 1896's Plessy v. Ferguson.

In 1935 White recruited Charles H. Houston as NAACP chief counsel. Houston was the Howard University law school dean whose strategy on school-segregation cases paved the way for his protégé Thurgood Marshall to prevail in 1954's Brown v. Board of Education, the decision that overturned Plessy.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, which was disproportionately disastrous for African Americans, the NAACP began to focus on economic justice. After years of tension with white labor unions, the Association cooperated with the newly formed Congress of Industrial Organizations in an effort to win jobs for black Americans. White, a friend and adviser to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, met with her often in attempts to convince President Franklin D. Roosevelt to outlaw job discrimination in the armed forces, defense industries and the agencies spawned by Roosevelt's New Deal legislation.

Roosevelt ultimately agreed to open thousands of jobs to black workers when the NAACP supported labor leader A. Philip Randolph and his March on Washington movement in 1941. President Roosevelt would also agree to set up a Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to ensure compliance.

Throughout the 1940s the NAACP saw enormous growth in membership, recording roughly 600,000 members by 1946. It continued to act as a legislative and legal advocate, pushing for a federal anti-lynching law and for an end to state-mandated segregation.

Source: Entire History of the NAACP: (with photographs)

http://naacp.3cdn.net/14a2d3f78c1910a...

These are just extracts which address membership numbers - started with 4 (1909) - then 60 (same time period), then the NAACP membership grew rapidly, from around 9,000 in 1917 to around 90,000 in 1919, with more than 300 local branches. throughout the 1940s the NAACP saw enormous growth in membership, recording roughly 600,000 members by 1946. It now has a half million members.

EXTRACTS FROM HISTORY

Founding group

Founded February 12, 1909, the NAACP is the nation's oldest, largest and most widely recognized grassroots–based civil rights organization. Its more than half-million members and supporters throughout the United States and the world are the premier advocates for civil rights in their communities, conducting voter mobilization and monitoring equal opportunity in the public and private sectors.

The NAACP was formed partly in response to the continuing horrific practice of lynching and the 1908 race riot in Springfield, the capital of Illinois and resting place of President Abraham Lincoln.