The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

Caesar

ROMAN EMPIRE -THE HISTORY...

>

CAESAR - GLOSSARY - Spoiler Thread

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Note that there is a separate thread carried over from the discussions of books in the Masters of Rome series by Colleen McCullough, titled SERIES - GLOSSARY - POTENTIAL SPOILERS. There are many topics there regarding ancient Rome, and potentially there will be repeats of them in this thread.

Here is the link: https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

There is also another great glossary that was done for the book Rubicon.

Here is the link to that glossary: https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

by

by

Colleen McCullough

Colleen McCullough

by

by

Tom Holland

Tom Holland

Here is the link: https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

There is also another great glossary that was done for the book Rubicon.

Here is the link to that glossary: https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

by

by

Colleen McCullough

Colleen McCullough by

by

Tom Holland

Tom Holland

Note that there is a separate thread carried over from the discussions of the book SPQR. There are many topics there regarding ancient Rome, and potentially there will be repeats of them in this thread.

Here is the link:

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

Here is the link:

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

Here is a list of the topics in the Series glossary. Until I can figure out how to post a link to a specific posting, I will copy over pertinent postings into this thread.

P 1

Servilla Caepionis

Marcus Junius Brutus the Elder

Fasces

Lictors

Julia, Daughter of Julius Caesar

Aurelia - Caesar's Mother

Cornelia Cinnilla, Julia's mother

Layout of the Roman Home

Romans: Family and Children

Seven Hills of Rome

Quaestor

all of the Roman Offices

Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus

Lucius Calpurnius Bibulus

Lucius Cornelius Balbus

Lucius Cornelius Balbus Younger

Cato the Younger

Cato the Elder - Marcus Porcius Cato

Julia (gens)

Gaius Julius Caesar (proconsul) - father of Julius Caesar

Marcus Licinius Crassus

Pompey

Julius Caesar

Auctoritas

Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Gaius Marius

Client, plebeian, plebs, praetor peregrinus, praetor urbanus, paterfamilias

Roman Naming Conventions

Saturnalia

Aulus Gabinius

P 2

Plebeians and Patricians

Cicero

The Boni

Gaius Cassius Longinus (post 54)

Lucius Licinius Lucullus

Quintus Hortensius Hortalus

Denarius coins of various periods

Gaius Memmius

Lucius Sergius Catilina

Quintus Servilius Caepio the Elder

Quintus Servilius Caepio the Younger

Aemilia Lepida

Atilia

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio Nasica

Military "Crowns"

Junia Secunda, Junia Tertia

Crucifixion

Quintus Lutatius Catulus

Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus

Appius Claudius Pulcher

Publius Clodius Pulcher

Tablinum

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

Gens Claudia

Clodia Metella

Gaius Valerius Catullus

Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus

Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo

Quintus Sertorius

Aulus Gabinius

Fimbriani

Fulvia

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Creticus

Marcus Aurelius Cotta

Marcus Antonius Gnipho

Quintus Marcius Rex

P 3

King Mithridates

Pharnaces

Gaius Verres

Panares and Lasthenes

Manius Acilius Glabrio

Gaius Calpurnius Piso

Vestal Virgins

Lucius Junius Brutus

Tax Farmers or Publicans

Censors

Equestrians

Lucius Roscius Otho

Lucius Aurelius Cotta

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus

Gaius Servilius Ahala

Quintus Fabius Maximus Cunctator

Lucius Aemilius Paullus

Mamercus Aemilius Lepidus Livianus

Marcus Livius Drusus

Adoption

Julia Antonia

Lucius Cornelius Cinna

Publius Sulla

Quintus Caecilius Metellus

Catulus Caesar

Aedile

Cursus Honorum

Ludi, or games

Funeral games

Titus Pomponius Atticus

Mos Maiorum

Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus

Lucius Gellius Publicola

Third Servile War

Marcus Junius Brutus

Caesar and the Pirates

Tribuni aerarii

Jury trials

Marcus Marius Gratidianus

Lucius Lucceius

Gaius Antonius Hybrida

Novus homo

Gaius Manilius

siege of Mitylene

Assizes

Slavery

Tigranes

Phraates

Marcus Terentius Varro

P 4

Hyrcanus

Antipater

Titus Labienus

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Nepos

Mucia Tertia

Ager publicus

Pontifex Maximus

Sempronia Tuditani

Atropos

hay on his horns

Flamen Dialis

Regia

Numa Pompilius

Rex Sacrorum

Quinctilis and Sextilis

Terentia

Treason Laws

Coercitio

King Nicomedes of Bithynia

Kalends, Nones, and Ides

Roman Triumvirates

Lucius Cornelius Balbus Major

Gaius Matius

Portus Itius

Gaius Trebatius Testa

Dumnorix

Codex

Gaul's three parts

Aulus Hirtius

Gauls/Celts

Druids

Ambiorix

Quintus Cicero

Caesar's bridges over the Rhine

Vercingetorix

Gaius Trebonius

silver eagle

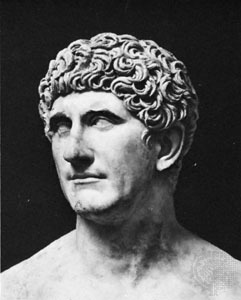

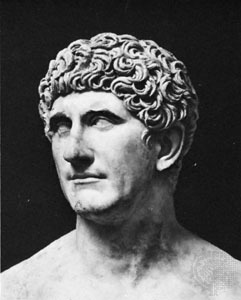

Mark Antony, through reading of Caesar’s will

P 5

The Rubicon (205)

Gaius Scribonius Curio

Battle of the Bagradas River

Ibises

Cleopatra's Alexandria

Potheinus

Mithridates of Pergamum

Achillas

Ganymedes

Silphium

Library of Alexandria

Lucius Marcius Philippus

Atia Balba Caesonia

Publius Cornelius Dolabella

Gaius Sallustius Crispus

Early life of Octavius (later the emperor Augustus)

Julian calendar

Roman triumph

Gnaeus Pompey the Younger

Sextus Pompey

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa

Battle of Munda

Quintus Salvidienus Rufus

Quintus Pedius

Lucius Pinarius Scarpus

Porcia Catonis

Roman dictator

Gaius Maecenas

Adlect

Gaius Vibius Pansa Caetronianus

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (triumvir)

Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus

Battle of Mutina

Philippics

Battle of Philippi

P 1

Servilla Caepionis

Marcus Junius Brutus the Elder

Fasces

Lictors

Julia, Daughter of Julius Caesar

Aurelia - Caesar's Mother

Cornelia Cinnilla, Julia's mother

Layout of the Roman Home

Romans: Family and Children

Seven Hills of Rome

Quaestor

all of the Roman Offices

Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus

Lucius Calpurnius Bibulus

Lucius Cornelius Balbus

Lucius Cornelius Balbus Younger

Cato the Younger

Cato the Elder - Marcus Porcius Cato

Julia (gens)

Gaius Julius Caesar (proconsul) - father of Julius Caesar

Marcus Licinius Crassus

Pompey

Julius Caesar

Auctoritas

Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Gaius Marius

Client, plebeian, plebs, praetor peregrinus, praetor urbanus, paterfamilias

Roman Naming Conventions

Saturnalia

Aulus Gabinius

P 2

Plebeians and Patricians

Cicero

The Boni

Gaius Cassius Longinus (post 54)

Lucius Licinius Lucullus

Quintus Hortensius Hortalus

Denarius coins of various periods

Gaius Memmius

Lucius Sergius Catilina

Quintus Servilius Caepio the Elder

Quintus Servilius Caepio the Younger

Aemilia Lepida

Atilia

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio Nasica

Military "Crowns"

Junia Secunda, Junia Tertia

Crucifixion

Quintus Lutatius Catulus

Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus

Appius Claudius Pulcher

Publius Clodius Pulcher

Tablinum

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

Gens Claudia

Clodia Metella

Gaius Valerius Catullus

Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus

Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo

Quintus Sertorius

Aulus Gabinius

Fimbriani

Fulvia

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Creticus

Marcus Aurelius Cotta

Marcus Antonius Gnipho

Quintus Marcius Rex

P 3

King Mithridates

Pharnaces

Gaius Verres

Panares and Lasthenes

Manius Acilius Glabrio

Gaius Calpurnius Piso

Vestal Virgins

Lucius Junius Brutus

Tax Farmers or Publicans

Censors

Equestrians

Lucius Roscius Otho

Lucius Aurelius Cotta

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus

Gaius Servilius Ahala

Quintus Fabius Maximus Cunctator

Lucius Aemilius Paullus

Mamercus Aemilius Lepidus Livianus

Marcus Livius Drusus

Adoption

Julia Antonia

Lucius Cornelius Cinna

Publius Sulla

Quintus Caecilius Metellus

Catulus Caesar

Aedile

Cursus Honorum

Ludi, or games

Funeral games

Titus Pomponius Atticus

Mos Maiorum

Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus

Lucius Gellius Publicola

Third Servile War

Marcus Junius Brutus

Caesar and the Pirates

Tribuni aerarii

Jury trials

Marcus Marius Gratidianus

Lucius Lucceius

Gaius Antonius Hybrida

Novus homo

Gaius Manilius

siege of Mitylene

Assizes

Slavery

Tigranes

Phraates

Marcus Terentius Varro

P 4

Hyrcanus

Antipater

Titus Labienus

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Nepos

Mucia Tertia

Ager publicus

Pontifex Maximus

Sempronia Tuditani

Atropos

hay on his horns

Flamen Dialis

Regia

Numa Pompilius

Rex Sacrorum

Quinctilis and Sextilis

Terentia

Treason Laws

Coercitio

King Nicomedes of Bithynia

Kalends, Nones, and Ides

Roman Triumvirates

Lucius Cornelius Balbus Major

Gaius Matius

Portus Itius

Gaius Trebatius Testa

Dumnorix

Codex

Gaul's three parts

Aulus Hirtius

Gauls/Celts

Druids

Ambiorix

Quintus Cicero

Caesar's bridges over the Rhine

Vercingetorix

Gaius Trebonius

silver eagle

Mark Antony, through reading of Caesar’s will

P 5

The Rubicon (205)

Gaius Scribonius Curio

Battle of the Bagradas River

Ibises

Cleopatra's Alexandria

Potheinus

Mithridates of Pergamum

Achillas

Ganymedes

Silphium

Library of Alexandria

Lucius Marcius Philippus

Atia Balba Caesonia

Publius Cornelius Dolabella

Gaius Sallustius Crispus

Early life of Octavius (later the emperor Augustus)

Julian calendar

Roman triumph

Gnaeus Pompey the Younger

Sextus Pompey

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa

Battle of Munda

Quintus Salvidienus Rufus

Quintus Pedius

Lucius Pinarius Scarpus

Porcia Catonis

Roman dictator

Gaius Maecenas

Adlect

Gaius Vibius Pansa Caetronianus

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (triumvir)

Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus

Battle of Mutina

Philippics

Battle of Philippi

Carthage

The port at Carthage

According to legend, Carthage was founded by the Phoenician Queen Elissa (better known as Dido) sometime around 813 BCE although, actually, it rose following Alexander's destruction of Tyre in 332 BCE. The city (in modern-day Tunisia, North Africa) was originally known as Kart-hadasht (new city) to distinguish it from the older Phoenician city of Utica nearby. The Greeks called the city Karchedon and the Romans turned this name into Carthago. Originally a small port on the coast, established only as a stop for Phoenician traders to re-supply or repair their ships, Carthage grew to become the most powerful city in the Mediterranean before the rise of Rome.

A Great Trade Centre

After the fall of the great Phoenician city of Tyre to Alexander the Great in 332 BCE, those Tyrians who were able to escape fled to Carthage with whatever wealth they had. Since many whom Alexander spared were those rich enough to buy their lives, these refugees landed in the city with considerable means and established Carthage as the new centre of Phoenician trade. The Carthaginians then drove the native Africans from the area, enslaved many of them, and exacted tribute from the rest. From a small town on the coast, the city grew in size and grandeur with enormous estates covering miles of acreage. Not even one hundred years passed before Carthage was the richest city in the Mediterranean. The aristocrats lived in palaces, the less affluent in modest but attractive homes, while tribute and tariffs regularly increased the city’s wealth on top of the lucrative business in trade. The harbour was immense, with 220 docks, gleaming columns which rose around it in a half-circle, and was ornamented with Greek sculpture. The Carthaginian trading ships sailed daily to ports all around the Mediterranean Sea while their navy, supreme in the region, kept them safe and, also, opened new territories for trade and resources through conquest.

Carthage Against Rome

It was this expansion which first brought Carthage into conflict with Rome. When Rome was weaker than Carthage, she posed no threat. The Carthaginian navy had long been able to enforce the treaty which kept Rome from trading in the western Mediterranean. When Carthage took Sicily, however, Rome responded. Though they had no navy and knew nothing of fighting on the sea, Rome built 330 ships which they equipped with clever ramps and gangways (the corvus) which could be lowered onto an enemy ship and secured; thus turning a sea battle into a land battle. The First Punic War (264-241 BCE) had begun. After an initial struggle with military tactics, Rome won a series of victories and finally defeated Carthage in 241 BCE. Carthage was forced to cede Sicily to Rome and pay a heavy war indemnity.

Following this war, Carthage became embroiled in what is known as The Mercenary War (241-237 BCE) which started when the Carthaginian army of mercenaries demanded the payment Carthage owed them. This war was finally won by Carthage through the efforts of the general Hamilcar Barca. Carthage suffered greatly from both these conflicts and, when Rome occupied the Carthaginian colonies of Sardinia and Corsica, there was nothing the Carthaginians could do about it. They tried to make the best of their situation by conquering and expanding holdings in Spain but again went to war with Rome when the Carthaginian general Hannibal attacked the city of Saguntum, an ally of Rome. The Second Punic War (218-202 BCE) was fought largely in northern Italy as Hannibal invaded Italy from Spain by marching his forces over the Alps. Hannibal won every engagement against the Romans in Italy. In 216 BCE he won his greatest victory at the Battle of Cannae but, lacking sufficient troops and supplies, could not build on his successes. He was defeated by the Roman general Scipio Africanus at the Battle of Zama, in North Africa, in 202 BCE and Carthage again sued for peace.

Placed, again, under a heavy war indemnity by Rome, Carthage struggled to pay their debt while also trying to fend off incursions from neighbouring Numidia. Carthage went to war against Numidia and lost. Having only recently paid off their debt to Rome, they now owed a new war debt to Numidia. Rome was not concerned with what Carthage and Numidia were involved with but did not care for the sudden revitalization of the Carthaginian army. Carthage believed that their treaty with Rome was ended when their war debt was paid; Rome disagreed. The Romans felt that Carthage was still obliged to bend to Roman will; so much so that the Roman Senator Cato the Elder ended all of his speeches, no matter what the subject, with the phrase, “Further, I think that Carthage should be destroyed.” In 149 BCE, Rome suggested just that course of action.

The Destruction of Carthage

A Roman embassy to Carthage made demands to the senate which included the stipulation that Carthage be dismantled and then re-built further inland. The Carthaginians, understandably, refused to do so and the Third Punic War (149-146 BCE) began. The Roman general Scipio Aemilianus besieged Carthage for three years until it fell. After sacking the city, the Romans burned it to the ground, leaving not one stone on top of another. A modern myth has grown up that the Romans forces then sowed the ruins with salt but this story has no basis in fact. It is said that Scipio Aemilianus wept when he ordered the destruction of the city and behaved virtuously toward the survivors.

Utica now became the capital of Rome’s African provinces and Carthage lay in ruin until 122 BCE when Gaius Sepronius Gracchus, the Roman tribune, founded a small colony there. Memory of the Punic wars still being too fresh, however, the colony failed. Julius Caesar proposed and planned the re-building of Carthage and, five years after his death, Carthage rose again. Power now shifted from Utica back to Carthage and it remained an important Roman colony until the fall of the empire.

Later History

Carthage rose in prominence as Christianity grew and Augustine of Hippo lived there before coming to Rome. The city continued under Roman influence through the Byzantine Empire (formerly the Eastern Roman Empire) who held it against repeated attacks by the Vandals. In 698 CE, the Muslims defeated the Byzantine forces at the Battle of Carthage, destroyed the city completely, and drove the Byzantines from Africa. They then fortified and developed the neighbouring city of Tunis and established it as the new centre for trade and governorship of the region. Carthage still lies in ruin in modern day Tunisia and remains an important tourist attraction and archaeological site. The outline of the great harbor can still be seen as well as the ruins of the homes and palaces from the time when the city of Carthage ruled the Mediterranean. (Source: http://www.ancient.eu/carthage/)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient...

http://www.roman-empire.net/republic/...

https://www.britannica.com/place/Cart...

http://www.livescience.com/24246-anci...

http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/e...

(no image) The Life and Death of Carthage; A Survey of Punic History and Culture from Its Birth to the Final Tragedy by Gilbert Charles Picard (no photo)

by Dexter Hoyos (no photo)

by Dexter Hoyos (no photo)

by Richard A. Gabriel (no photo)

by Richard A. Gabriel (no photo)

by Leonard Cottrell (no photo)

by Leonard Cottrell (no photo)

by

by

Richard Miles

Richard Miles

The port at Carthage

According to legend, Carthage was founded by the Phoenician Queen Elissa (better known as Dido) sometime around 813 BCE although, actually, it rose following Alexander's destruction of Tyre in 332 BCE. The city (in modern-day Tunisia, North Africa) was originally known as Kart-hadasht (new city) to distinguish it from the older Phoenician city of Utica nearby. The Greeks called the city Karchedon and the Romans turned this name into Carthago. Originally a small port on the coast, established only as a stop for Phoenician traders to re-supply or repair their ships, Carthage grew to become the most powerful city in the Mediterranean before the rise of Rome.

A Great Trade Centre

After the fall of the great Phoenician city of Tyre to Alexander the Great in 332 BCE, those Tyrians who were able to escape fled to Carthage with whatever wealth they had. Since many whom Alexander spared were those rich enough to buy their lives, these refugees landed in the city with considerable means and established Carthage as the new centre of Phoenician trade. The Carthaginians then drove the native Africans from the area, enslaved many of them, and exacted tribute from the rest. From a small town on the coast, the city grew in size and grandeur with enormous estates covering miles of acreage. Not even one hundred years passed before Carthage was the richest city in the Mediterranean. The aristocrats lived in palaces, the less affluent in modest but attractive homes, while tribute and tariffs regularly increased the city’s wealth on top of the lucrative business in trade. The harbour was immense, with 220 docks, gleaming columns which rose around it in a half-circle, and was ornamented with Greek sculpture. The Carthaginian trading ships sailed daily to ports all around the Mediterranean Sea while their navy, supreme in the region, kept them safe and, also, opened new territories for trade and resources through conquest.

Carthage Against Rome

It was this expansion which first brought Carthage into conflict with Rome. When Rome was weaker than Carthage, she posed no threat. The Carthaginian navy had long been able to enforce the treaty which kept Rome from trading in the western Mediterranean. When Carthage took Sicily, however, Rome responded. Though they had no navy and knew nothing of fighting on the sea, Rome built 330 ships which they equipped with clever ramps and gangways (the corvus) which could be lowered onto an enemy ship and secured; thus turning a sea battle into a land battle. The First Punic War (264-241 BCE) had begun. After an initial struggle with military tactics, Rome won a series of victories and finally defeated Carthage in 241 BCE. Carthage was forced to cede Sicily to Rome and pay a heavy war indemnity.

Following this war, Carthage became embroiled in what is known as The Mercenary War (241-237 BCE) which started when the Carthaginian army of mercenaries demanded the payment Carthage owed them. This war was finally won by Carthage through the efforts of the general Hamilcar Barca. Carthage suffered greatly from both these conflicts and, when Rome occupied the Carthaginian colonies of Sardinia and Corsica, there was nothing the Carthaginians could do about it. They tried to make the best of their situation by conquering and expanding holdings in Spain but again went to war with Rome when the Carthaginian general Hannibal attacked the city of Saguntum, an ally of Rome. The Second Punic War (218-202 BCE) was fought largely in northern Italy as Hannibal invaded Italy from Spain by marching his forces over the Alps. Hannibal won every engagement against the Romans in Italy. In 216 BCE he won his greatest victory at the Battle of Cannae but, lacking sufficient troops and supplies, could not build on his successes. He was defeated by the Roman general Scipio Africanus at the Battle of Zama, in North Africa, in 202 BCE and Carthage again sued for peace.

Placed, again, under a heavy war indemnity by Rome, Carthage struggled to pay their debt while also trying to fend off incursions from neighbouring Numidia. Carthage went to war against Numidia and lost. Having only recently paid off their debt to Rome, they now owed a new war debt to Numidia. Rome was not concerned with what Carthage and Numidia were involved with but did not care for the sudden revitalization of the Carthaginian army. Carthage believed that their treaty with Rome was ended when their war debt was paid; Rome disagreed. The Romans felt that Carthage was still obliged to bend to Roman will; so much so that the Roman Senator Cato the Elder ended all of his speeches, no matter what the subject, with the phrase, “Further, I think that Carthage should be destroyed.” In 149 BCE, Rome suggested just that course of action.

The Destruction of Carthage

A Roman embassy to Carthage made demands to the senate which included the stipulation that Carthage be dismantled and then re-built further inland. The Carthaginians, understandably, refused to do so and the Third Punic War (149-146 BCE) began. The Roman general Scipio Aemilianus besieged Carthage for three years until it fell. After sacking the city, the Romans burned it to the ground, leaving not one stone on top of another. A modern myth has grown up that the Romans forces then sowed the ruins with salt but this story has no basis in fact. It is said that Scipio Aemilianus wept when he ordered the destruction of the city and behaved virtuously toward the survivors.

Utica now became the capital of Rome’s African provinces and Carthage lay in ruin until 122 BCE when Gaius Sepronius Gracchus, the Roman tribune, founded a small colony there. Memory of the Punic wars still being too fresh, however, the colony failed. Julius Caesar proposed and planned the re-building of Carthage and, five years after his death, Carthage rose again. Power now shifted from Utica back to Carthage and it remained an important Roman colony until the fall of the empire.

Later History

Carthage rose in prominence as Christianity grew and Augustine of Hippo lived there before coming to Rome. The city continued under Roman influence through the Byzantine Empire (formerly the Eastern Roman Empire) who held it against repeated attacks by the Vandals. In 698 CE, the Muslims defeated the Byzantine forces at the Battle of Carthage, destroyed the city completely, and drove the Byzantines from Africa. They then fortified and developed the neighbouring city of Tunis and established it as the new centre for trade and governorship of the region. Carthage still lies in ruin in modern day Tunisia and remains an important tourist attraction and archaeological site. The outline of the great harbor can still be seen as well as the ruins of the homes and palaces from the time when the city of Carthage ruled the Mediterranean. (Source: http://www.ancient.eu/carthage/)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient...

http://www.roman-empire.net/republic/...

https://www.britannica.com/place/Cart...

http://www.livescience.com/24246-anci...

http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/e...

(no image) The Life and Death of Carthage; A Survey of Punic History and Culture from Its Birth to the Final Tragedy by Gilbert Charles Picard (no photo)

by Dexter Hoyos (no photo)

by Dexter Hoyos (no photo) by Richard A. Gabriel (no photo)

by Richard A. Gabriel (no photo) by Leonard Cottrell (no photo)

by Leonard Cottrell (no photo) by

by

Richard Miles

Richard Miles

message 7:

by

Vicki, Assisting Moderator - Ancient Roman History

(last edited Feb 05, 2018 01:42PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Polybius

Polybius

Polybius (/pəˈlɪbiəs/; Greek: Πολύβιος, Polýbios; c. 200 – c. 118 BC) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period noted for his work, The Histories, which covered the period of 264–146 BC in detail. The work describes the rise of the Roman Republic to the status of dominance in the ancient Mediterranean world and included his eyewitness account of the Sack of Carthage in 146 BC. Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed constitution or the separation of powers in government, which was influential on Montesquieu's The Spirit of the Laws and the framers of the United States Constitution.

Origins

Polybius was born around 200 BC in Megalopolis, Arcadia, when it was an active member of the Achaean League. His father, Lycortas, was a prominent, land-owning politician and member of the governing class who became strategos (commanding general) of the Achaean League. Consequently, Polybius was able to observe first hand the political and military affairs of Megalopolis. He developed an interest in horse riding and hunting, diversions that later commended him to his Roman captors. In 182 BC, he was given quite an honor when he was chosen to carry the funeral urn of Philopoemen, one of the most eminent Achaean politicians of his generation. In either 169 BC or 170 BC, Polybius was elected hipparchus (cavalry officer), an event which often presaged election to the annual strategia (chief generalship). His early political career was devoted largely towards maintaining the independence of Megalopolis.

Personal experiences

Polybius’ father, Lycortas, was a prominent advocate of neutrality during the Roman war against Perseus of Macedon. Lycortas attracted the suspicion of the Romans, and Polybius subsequently was one of the 1,000 Achaean nobles who were transported to Rome as hostages in 167 BC, and was detained there for 17 years. In Rome, by virtue of his high culture, Polybius was admitted to the most distinguished houses, in particular to that of Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus, the conqueror in the Third Macedonian War, who entrusted Polybius with the education of his sons, Fabius and Scipio Aemilianus (who had been adopted by the eldest son of Scipio Africanus). Polybius remained on cordial terms with his former pupil Scipio Aemilianus and was among the members of the Scipionic Circle. Polybius remained a counselor to Scipio when he defeated the Carthaginians in the Third Punic War. When the Achaean hostages were released in 150 BC, Polybius was granted leave to return home, but the next year he went on campaign with Scipio Aemilianus to Africa, and was present at the Sack of Carthage in 146, which he later described. Following the destruction of Carthage, Polybius likely journeyed along the Atlantic coast of Africa, as well as Spain.

After the destruction of Corinth in the same year, Polybius returned to Greece, making use of his Roman connections to lighten the conditions there. Polybius was charged with the difficult task of organizing the new form of government in the Greek cities, and in this office he gained great recognition.

At Rome

In the succeeding years, Polybius resided in Rome, completing his historical work while occasionally undertaking long journeys through the Mediterranean countries in the furtherance of his history, in particular with the aim of obtaining firsthand knowledge of historical sites. He apparently interviewed veterans to clarify details of the events he was recording and was similarly given access to archival material. Little is known of Polybius' later life; he most likely accompanied Scipio to Spain, acting as his military advisor during the Numantine War. He later wrote about this war in a lost monograph. Polybius probably returned to Greece later in his life, as evidenced by the many existent inscriptions and statues of him there. The last event mentioned in his Histories seems to be the construction of the Via Domitia in southern France in 118 BC, which suggests the writings of Pseudo-Lucian may have some grounding in fact when they state, "[Polybius] fell from his horse while riding up from the country, fell ill as a result and died at the age of eighty-two".

The Histories

Polybius’ Histories cover the period from 264 BC to 146 BC. Its main focus is the period from 220 BC to 167 BC, describing Rome's efforts in subduing its arch-enemy, Carthage, and thereby becoming the dominant Mediterranean force. Books I through V of The Histories are the introduction for the years during his lifetime, describing the politics in leading Mediterranean states, including ancient Greece and Egypt, and culminating in their ultimate συμπλοκή or interconnectedness. In Book VI, Polybius describes the political, military, and moral institutions that allowed the Romans to succeed. He describes the First and Second Punic Wars. Polybius concludes the Romans are the pre-eminent power because they have customs and institutions which promote a deep desire for noble acts, a love of virtue, piety towards parents and elders, and a fear of the gods (deisidaimonia). He also chronicled the conflicts between Hannibal and Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus such as the Battle of Ticinus, the Battle of the Trebia, the Siege of Saguntum, the Battle of Lilybaeum, and the Battle of Rhone Crossing. In Book XII, Polybius discusses the worth of Timaeus’ account of the same period of history. He asserts Timaeus' point of view is inaccurate, invalid, and biased in favor of Rome. Therefore, Polybius's Histories is also useful in analyzing the different Hellenistic versions of history and of use as a credible illustration of actual events during the Hellenistic period.

Sources

In the seventh volume of his Histories, Polybius defines the historian's job as the analysis of documentation, the review of relevant geographical information, and political experience. Polybius held that historians should only chronicle events whose participants the historian was able to interview, and was among the first to champion the notion of factual integrity in historical writing. In Polybius' time, the profession of a historian required political experience (which aided in differentiating between fact and fiction) and familiarity with the geography surrounding one's subject matter to supply an accurate version of events. Polybius himself exemplified these principles as he was traveled and possessed political and military experience. He did not neglect written sources that proved essential material for his histories from the period from 264 BC to 220 BC. When addressing events after 220 BC, he examined the writings of Greek and Roman historians to acquire credible sources of information, but rarely did he name those sources.

As historian

Polybius wrote several works, the majority of which are lost. His earliest work was a biography of the Greek statesman Philopoemen; this work was later used as a source by Plutarch when composing his Parallel Lives, however the original Polybian text is lost. In addition, Polybius wrote an extensive treatise entitled Tactics, which may have detailed Roman and Greek military tactics. Small parts of this work may survive in his major Histories, but the work itself is lost, as well. Another missing work was a historical monograph on the events of the Numantine War. The largest Polybian work was, of course, his Histories, of which only the first five books survive entirely intact, along with a large portion of the sixth book and fragments of the rest. Along with Cato the Elder (234–149 BC), he can be considered one of the founding fathers of Roman historiography.

Livy made reference to and uses Polybius' Histories as source material in his own narrative. Polybius was among the first historians to attempt to present history as a sequence of causes and effects, based upon a careful examination and criticism of tradition. He narrated his history based upon first-hand knowledge. The Histories capture the varied elements of the story of human behavior: nationalism, xenophobia, duplicitous politics, war, brutality, loyalty, valour, intelligence, reason, and resourcefulness.

A key theme of The Histories is the good statesman as virtuous and composed. The character of the Polybian statesman is exemplified in that of Philip II. His beliefs about Philip's character led Polybius to reject historian Theopompus' description of Philip's private, drunken debauchery. For Polybius, it was inconceivable that such an able and effective statesman could have had an immoral and unrestrained private life as described by Theopompus. In recounting the Roman Republic, Polybius stated that "the Senate stands in awe of the multitude, and cannot neglect the feelings of the people".

Other important themes running through The Histories are the role of Fortune in the affairs of nations, his insistence that history should be demonstratory, or apodeiktike, providing lessons for statesmen, and that historians should be "men of action" (pragmatikoi).

Polybius is considered by some to be the successor of Thucydides in terms of objectivity and critical reasoning, and the forefather of scholarly, painstaking historical research in the modern scientific sense. According to this view, his work sets forth the course of history's occurrences with clearness, penetration, sound judgment, and, among the circumstances affecting the outcomes, he lays especial emphasis on geographical conditions. Modern historians are especially impressed with the manner in which Polybius used his sources, particularly documentary evidence as well as his citation and quotation of sources. Furthermore, there is some admiration of Polybius's meditation on the nature of historiography in Book 12. His work belongs, therefore, amongst the greatest productions of ancient historical writing. The writer of the Oxford Companion to Classical Literature (1937) praises him for his "earnest devotion to truth" and his systematic pursuit of causation.

First as a hostage in Rome, then as client to the Scipios, and finally as a collaborator with Roman rule after 146 BC, Polybius was not in a position to freely express any negative opinions of Rome. Peter Green advises us to recall that Polybius was chronicling Roman history for a Greek audience, with the aim of convincing them of the necessity of accepting Roman rule – which he believed was inevitable. Nonetheless, for Green, Polybius's Histories remain invaluable and are the best source for the era they cover. Ron Mellor also sees Polybius as partisan who, out of loyalty to Scipio, vilified Scipio's opponents. Similarly, Adrian Goldsworthy frequently mentions Polybius' connections with Scipio when he uses Polybius as a source for Scipio's generalship. (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polybius)

More:

https://www.britannica.com/biography/...

http://www.ancient.eu/Polybius/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_His...

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/t...

http://www.mmdtkw.org/VPolybius.html

by Polybius (no photo)

by Polybius (no photo)

by Bruce Gibson (no photo)

by Bruce Gibson (no photo)

by Donald Walter Baranowski (no photo)

by Donald Walter Baranowski (no photo)

by Christopher Smith (no photo)

by Christopher Smith (no photo)

by T. James Luce (no photo)

by T. James Luce (no photo)

Polybius

Polybius (/pəˈlɪbiəs/; Greek: Πολύβιος, Polýbios; c. 200 – c. 118 BC) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period noted for his work, The Histories, which covered the period of 264–146 BC in detail. The work describes the rise of the Roman Republic to the status of dominance in the ancient Mediterranean world and included his eyewitness account of the Sack of Carthage in 146 BC. Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed constitution or the separation of powers in government, which was influential on Montesquieu's The Spirit of the Laws and the framers of the United States Constitution.

Origins

Polybius was born around 200 BC in Megalopolis, Arcadia, when it was an active member of the Achaean League. His father, Lycortas, was a prominent, land-owning politician and member of the governing class who became strategos (commanding general) of the Achaean League. Consequently, Polybius was able to observe first hand the political and military affairs of Megalopolis. He developed an interest in horse riding and hunting, diversions that later commended him to his Roman captors. In 182 BC, he was given quite an honor when he was chosen to carry the funeral urn of Philopoemen, one of the most eminent Achaean politicians of his generation. In either 169 BC or 170 BC, Polybius was elected hipparchus (cavalry officer), an event which often presaged election to the annual strategia (chief generalship). His early political career was devoted largely towards maintaining the independence of Megalopolis.

Personal experiences

Polybius’ father, Lycortas, was a prominent advocate of neutrality during the Roman war against Perseus of Macedon. Lycortas attracted the suspicion of the Romans, and Polybius subsequently was one of the 1,000 Achaean nobles who were transported to Rome as hostages in 167 BC, and was detained there for 17 years. In Rome, by virtue of his high culture, Polybius was admitted to the most distinguished houses, in particular to that of Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus, the conqueror in the Third Macedonian War, who entrusted Polybius with the education of his sons, Fabius and Scipio Aemilianus (who had been adopted by the eldest son of Scipio Africanus). Polybius remained on cordial terms with his former pupil Scipio Aemilianus and was among the members of the Scipionic Circle. Polybius remained a counselor to Scipio when he defeated the Carthaginians in the Third Punic War. When the Achaean hostages were released in 150 BC, Polybius was granted leave to return home, but the next year he went on campaign with Scipio Aemilianus to Africa, and was present at the Sack of Carthage in 146, which he later described. Following the destruction of Carthage, Polybius likely journeyed along the Atlantic coast of Africa, as well as Spain.

After the destruction of Corinth in the same year, Polybius returned to Greece, making use of his Roman connections to lighten the conditions there. Polybius was charged with the difficult task of organizing the new form of government in the Greek cities, and in this office he gained great recognition.

At Rome

In the succeeding years, Polybius resided in Rome, completing his historical work while occasionally undertaking long journeys through the Mediterranean countries in the furtherance of his history, in particular with the aim of obtaining firsthand knowledge of historical sites. He apparently interviewed veterans to clarify details of the events he was recording and was similarly given access to archival material. Little is known of Polybius' later life; he most likely accompanied Scipio to Spain, acting as his military advisor during the Numantine War. He later wrote about this war in a lost monograph. Polybius probably returned to Greece later in his life, as evidenced by the many existent inscriptions and statues of him there. The last event mentioned in his Histories seems to be the construction of the Via Domitia in southern France in 118 BC, which suggests the writings of Pseudo-Lucian may have some grounding in fact when they state, "[Polybius] fell from his horse while riding up from the country, fell ill as a result and died at the age of eighty-two".

The Histories

Polybius’ Histories cover the period from 264 BC to 146 BC. Its main focus is the period from 220 BC to 167 BC, describing Rome's efforts in subduing its arch-enemy, Carthage, and thereby becoming the dominant Mediterranean force. Books I through V of The Histories are the introduction for the years during his lifetime, describing the politics in leading Mediterranean states, including ancient Greece and Egypt, and culminating in their ultimate συμπλοκή or interconnectedness. In Book VI, Polybius describes the political, military, and moral institutions that allowed the Romans to succeed. He describes the First and Second Punic Wars. Polybius concludes the Romans are the pre-eminent power because they have customs and institutions which promote a deep desire for noble acts, a love of virtue, piety towards parents and elders, and a fear of the gods (deisidaimonia). He also chronicled the conflicts between Hannibal and Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus such as the Battle of Ticinus, the Battle of the Trebia, the Siege of Saguntum, the Battle of Lilybaeum, and the Battle of Rhone Crossing. In Book XII, Polybius discusses the worth of Timaeus’ account of the same period of history. He asserts Timaeus' point of view is inaccurate, invalid, and biased in favor of Rome. Therefore, Polybius's Histories is also useful in analyzing the different Hellenistic versions of history and of use as a credible illustration of actual events during the Hellenistic period.

Sources

In the seventh volume of his Histories, Polybius defines the historian's job as the analysis of documentation, the review of relevant geographical information, and political experience. Polybius held that historians should only chronicle events whose participants the historian was able to interview, and was among the first to champion the notion of factual integrity in historical writing. In Polybius' time, the profession of a historian required political experience (which aided in differentiating between fact and fiction) and familiarity with the geography surrounding one's subject matter to supply an accurate version of events. Polybius himself exemplified these principles as he was traveled and possessed political and military experience. He did not neglect written sources that proved essential material for his histories from the period from 264 BC to 220 BC. When addressing events after 220 BC, he examined the writings of Greek and Roman historians to acquire credible sources of information, but rarely did he name those sources.

As historian

Polybius wrote several works, the majority of which are lost. His earliest work was a biography of the Greek statesman Philopoemen; this work was later used as a source by Plutarch when composing his Parallel Lives, however the original Polybian text is lost. In addition, Polybius wrote an extensive treatise entitled Tactics, which may have detailed Roman and Greek military tactics. Small parts of this work may survive in his major Histories, but the work itself is lost, as well. Another missing work was a historical monograph on the events of the Numantine War. The largest Polybian work was, of course, his Histories, of which only the first five books survive entirely intact, along with a large portion of the sixth book and fragments of the rest. Along with Cato the Elder (234–149 BC), he can be considered one of the founding fathers of Roman historiography.

Livy made reference to and uses Polybius' Histories as source material in his own narrative. Polybius was among the first historians to attempt to present history as a sequence of causes and effects, based upon a careful examination and criticism of tradition. He narrated his history based upon first-hand knowledge. The Histories capture the varied elements of the story of human behavior: nationalism, xenophobia, duplicitous politics, war, brutality, loyalty, valour, intelligence, reason, and resourcefulness.

A key theme of The Histories is the good statesman as virtuous and composed. The character of the Polybian statesman is exemplified in that of Philip II. His beliefs about Philip's character led Polybius to reject historian Theopompus' description of Philip's private, drunken debauchery. For Polybius, it was inconceivable that such an able and effective statesman could have had an immoral and unrestrained private life as described by Theopompus. In recounting the Roman Republic, Polybius stated that "the Senate stands in awe of the multitude, and cannot neglect the feelings of the people".

Other important themes running through The Histories are the role of Fortune in the affairs of nations, his insistence that history should be demonstratory, or apodeiktike, providing lessons for statesmen, and that historians should be "men of action" (pragmatikoi).

Polybius is considered by some to be the successor of Thucydides in terms of objectivity and critical reasoning, and the forefather of scholarly, painstaking historical research in the modern scientific sense. According to this view, his work sets forth the course of history's occurrences with clearness, penetration, sound judgment, and, among the circumstances affecting the outcomes, he lays especial emphasis on geographical conditions. Modern historians are especially impressed with the manner in which Polybius used his sources, particularly documentary evidence as well as his citation and quotation of sources. Furthermore, there is some admiration of Polybius's meditation on the nature of historiography in Book 12. His work belongs, therefore, amongst the greatest productions of ancient historical writing. The writer of the Oxford Companion to Classical Literature (1937) praises him for his "earnest devotion to truth" and his systematic pursuit of causation.

First as a hostage in Rome, then as client to the Scipios, and finally as a collaborator with Roman rule after 146 BC, Polybius was not in a position to freely express any negative opinions of Rome. Peter Green advises us to recall that Polybius was chronicling Roman history for a Greek audience, with the aim of convincing them of the necessity of accepting Roman rule – which he believed was inevitable. Nonetheless, for Green, Polybius's Histories remain invaluable and are the best source for the era they cover. Ron Mellor also sees Polybius as partisan who, out of loyalty to Scipio, vilified Scipio's opponents. Similarly, Adrian Goldsworthy frequently mentions Polybius' connections with Scipio when he uses Polybius as a source for Scipio's generalship. (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polybius)

More:

https://www.britannica.com/biography/...

http://www.ancient.eu/Polybius/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_His...

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/t...

http://www.mmdtkw.org/VPolybius.html

by Polybius (no photo)

by Polybius (no photo) by Bruce Gibson (no photo)

by Bruce Gibson (no photo) by Donald Walter Baranowski (no photo)

by Donald Walter Baranowski (no photo) by Christopher Smith (no photo)

by Christopher Smith (no photo) by T. James Luce (no photo)

by T. James Luce (no photo)

Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius, (born c. 157 bce, Cereatae, near Arpinum [Arpino], Latium [now in Italy]—died January 13, 86 bce, Rome), Roman general and politician, consul seven times (107, 104–100, 86 bce), who was the first Roman to illustrate the political support that a successful general could derive from the votes of his old army veterans.

Early career

Gaius Marius was a strong and brave soldier and a skillful general, popular with his troops, but he showed little flair for politics and was not a good public speaker. As an equestrian, he lacked the education in Greek normal to the upper classes. He was superstitious and overwhelmingly ambitious, and, because he failed to force the aristocracy to accept him, despite his great military success, he suffered from an inferiority complex that may help explain his jealousy and vindictive cruelty. As a young officer-cadet, along with Jugurtha (later king of Numidia), on Scipio Aemilianus’ staff in the Numantine War in Spain (134 bce), he, like Jugurtha, made an excellent impression on his commanding officer. Marius’ family enjoyed the patronage of more than one noble family, in particular the distinguished and inordinately conceited Caecilii Metelli, then at the height of their political power. They backed his candidacy for tribune (defender) of the plebs (common people) in 119. As tribune, Marius proposed a bill affecting procedure in elections and legislative assemblies by narrowing the bridges—the gangway across which each voter passed to fill in and deposit his ballot tablet—as a result of which there was no longer room on the gangway for observers, normally aristocrats, who abused their position to influence an individual’s vote. When the two consuls tried to persuade the Senate to block the bill, Marius threatened them with imprisonment, and the bill was carried.

Marius showed himself no unprincipled candidate for popular favour, for he vetoed a popular grain bill, and the following years offered him little promise of a conspicuous career. He failed to secure the aedileship (control of markets and police) and was only just elected praetor (judicial magistrate) for the year 115 after bribing heavily, for which he was lucky to escape condemnation in court. The next year he governed Further Spain, campaigned successfully against bandits, and laid a foundation for great personal wealth through mining investments. After that, he made a good marriage into a patrician family that, after long obscurity, was on the point of strong political revival. His wife was Julia, the aunt of Julius Caesar.

Election to the consulship

The command in the war against Jugurtha (who was now Numidian king) was given to Quintus Metellus, and Marius was invited to join Metellus’ staff. After defeating Jugurtha in pitched battle, Metellus was less successful in later guerrilla warfare, and this failure was exaggerated by Marius in his public statements when at the end of 108 he returned to Rome to seek the consulship (chief magistracy). Marius was elected on the equestrian and popular vote and, to Metellus’ bitter chagrin, appointed by a popular bill to succeed Metellus at once in the African command.

In recruiting fresh troops, Marius broke with custom, because of a manpower shortage, by enrolling volunteers from outside the propertied classes, which alone had previously been liable for service. In Africa he kept Jugurtha on the run, and in 105 Jugurtha was captured, betrayed by his ally, King Bocchus of Mauretania—not to Marius himself but to Sulla, considered a rather disreputable young aristocrat, who had joined Marius’ staff as quaestor in 107. Sulla had the incident engraved on his seal, provoking Marius’ jealousy.

The victory, however, was Marius’, and he was elected consul again for 104—at the start of which year he celebrated a triumph and Jugurtha was executed—in order to take command against an alarming invasion of the Cimbri and Teutones, who had defeated a succession of Roman armies in the north, the last in disgraceful circumstances in 105. For this war, Marius used fresh troops raised by Rutilius Rufus, consul in 105, and excellently trained in commando tactics by gladiatorial instructors. With them, Marius defeated the Teutones at Aquae Sextiae (modern Aix-en-Provence, Fr.) in 102 and in 101 came to the support of the consul of 102, Quintus Lutatius Catulus, who had suffered a serious setback; together they defeated the Cimbri at the Vercellae, near modern Rovigo in the Po River valley, and the danger was over. This was the apex of Marius’ success. He had been consul every year since 104, and he was elected again the year 100. With Catulus he celebrated a joint triumph, but already there was bad feeling between them. Marius claimed the whole credit for the victory; Catulus and Sulla gave very different accounts of the event in their memoirs.

Marius had always had equestrian support, not only because his origins lay in that class but also because wars were bad for trade, and Marius had brought serious wars to an end. The Roman populace liked him because he was not an aristocrat. He had the further support of his veterans, for it was in their interest to stick closely to their general. Marius perhaps did not realize the potency of their force, one that Sulla, Caesar, and Octavian employed with overpowering effect later.

Fall from power

The year 100 saw Marius fail disastrously as a politician. Saturninus was tribune for the second time, and Glaucia was praetor; given the poverty of surviving sources, it is extremely difficult to understand either their political aims or Marius’ relationship to them. The three shared a common hatred of Metellus, who, as censor in 102, had tried to remove Saturninus and Glaucia from the Senate, and in 103 Saturninus had carried a bill, evidently in Marius’ interest, for the settlement of veterans in Africa. Now, with the inevitability of civil disorder—for the Roman populace opposed his measures—Saturninus introduced bills for land distribution of Cimbric territory in the north to Romans living in the country, and probably to Italians, and for the settlement of veterans, evidently including allied troops, in colonies overseas. This bill may have included a powerful command for Marius to supervise the resettlement of the veterans—empowering him to give Roman citizenship to a certain number of the new settlers in each colony.

Marius had already violated the law by granting citizenship on the battlefield to two cohorts of Italians (Camertes) who fought under him against the Cimbri in 101, and conceivably Saturninus and Marius were agreeable to a program of extensive enfranchisement of Italians by means of the new colonial settlements. A breach between them occurred, possibly because Marius, in his jealous way, thought that Saturninus was stealing some of his own thunder or possibly because Saturninus’ lawlessness had reached a pitch that no self-respecting consul could tolerate.

First the land and colonial bill was passed, but with blatant illegality; it required senators to take an oath within five days to observe it. After misleading statements about his own intention, Marius took the oath. Metellus refused, however, presumably because of the way in which the bill had been carried, and, forestalling condemnation in the treason court, he retired to Greece; later he was officially exiled. At the tribunician elections for 99, Saturninus was reelected together with a pretender who, already heavily discredited, claimed to be the son of Tiberius Gracchus. At the consular elections, with Glaucia as a candidate, Marcus Antonius, the orator, was elected, and Gaius Memmius, a man with an excellent popular record, was murdered. In the ensuing pandemonium the Senate passed the “last decree,” calling on the consuls to save the state. Through Marius’ action Saturninus and Glaucia were captured on the Capitol and imprisoned in the Senate house; then a mob stripped off the roof and stoned them to death. Although this was no responsibility of Marius, he was smeared as a man who betrayed not only his enemies but also his friends.

Later years

Rather than attend the inevitable recall of Metellus from exile, Marius went to the east in 99 and there met Mithradates VI of Pontus. He was elected to a priesthood (the augurship) but wisely withdrew his candidature for the censorship of 97. He acted as a background figure in the not fully unraveled politics of the 90s and successfully opposed an attempt in 95 to disenfranchise men to whom he had given citizenship under the terms of Saturninus’ colonial bill, though the law itself had been shelved. In 92 he supported the scandalous prosecution and condemnation of his old associate Rutilius Rufus (in fact a model administrator) for alleged misgovernment of Asia.

Marius was now beginning to show his age. In an Italian rebellion (the Social War) of 90–88, he campaigned under the consul Rutilius Lupus, a soldier far his inferior. In 88, when the tribune Sulpicius Rufus proposed the transfer of the Asian command from the consul Sulla to Marius, presumably on the ground that Marius alone was sufficiently experienced to conduct such a critical war, there was violent public opposition to Sulla in Rome. Sulla went to his army in Campania and marched with it on Rome. Sulpicius’ measures were rescinded, and Marius was exiled.

After a series of near catastrophes, all much embroidered in the telling, Marius escaped safely to Africa. In 87, when Sulla was fighting in Greece, disorder in Rome led to the consul Cinna being dismissed. Marius landed in Etruria, raised an army, sacked Ostia, and, by joining forces with Cinna, captured Rome; both Marius and Cinna were elected consuls for 86, Marius for the seventh time. Hideous massacre followed as Marius ordered the deaths of Marcus Antonius, Lutatius Catulus, Publicus Licinius Crassus, and other distinguished men whom he considered to have behaved with treacherous ingratitude toward him. By this time he was hardly sane, and his death, in 86, was a godsend for enemies and friends alike. If the outcome of his proscriptions was considered to be less disastrous than that of the later proscriptions of Sulla, it was only because they lasted for a shorter time.

Marius’ only son died as consul fighting against Sulla in 82. His widow survived until 69 and received the unusual honour, for a woman, of a public funeral oration by her nephew Julius Caesar, who later won great popularity by restoring to the Capitol Marius’ trophies, which Sulla had removed.

Marius was commemorated by the name Mariana given to Uchi Majus and Thibaris (two African settlements) and to a colony in Corsica, and by the Fossa Mariana, a canal dug by his soldiers at the mouth of the Rhône River. (Source: https://www.britannica.com/biography/...)

More:

http://www.roman-empire.net/republic/...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaius_M...

http://www.unrv.com/empire/gaius-mari...

http://faculty.vassar.edu/jolott/old_...

http://military.wikia.com/wiki/Gaius_...

(no image) Gaius Marius: A Political Biography by Richard J. Evans (no photo)

by Christopher Anthony Matthew (no photo)

by Christopher Anthony Matthew (no photo)

by Marc Hyden (no photo)

by Marc Hyden (no photo)

by Lawrence Keppie (no photo)

by Lawrence Keppie (no photo)

by

by

Plutarch

Plutarch

Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius, (born c. 157 bce, Cereatae, near Arpinum [Arpino], Latium [now in Italy]—died January 13, 86 bce, Rome), Roman general and politician, consul seven times (107, 104–100, 86 bce), who was the first Roman to illustrate the political support that a successful general could derive from the votes of his old army veterans.

Early career

Gaius Marius was a strong and brave soldier and a skillful general, popular with his troops, but he showed little flair for politics and was not a good public speaker. As an equestrian, he lacked the education in Greek normal to the upper classes. He was superstitious and overwhelmingly ambitious, and, because he failed to force the aristocracy to accept him, despite his great military success, he suffered from an inferiority complex that may help explain his jealousy and vindictive cruelty. As a young officer-cadet, along with Jugurtha (later king of Numidia), on Scipio Aemilianus’ staff in the Numantine War in Spain (134 bce), he, like Jugurtha, made an excellent impression on his commanding officer. Marius’ family enjoyed the patronage of more than one noble family, in particular the distinguished and inordinately conceited Caecilii Metelli, then at the height of their political power. They backed his candidacy for tribune (defender) of the plebs (common people) in 119. As tribune, Marius proposed a bill affecting procedure in elections and legislative assemblies by narrowing the bridges—the gangway across which each voter passed to fill in and deposit his ballot tablet—as a result of which there was no longer room on the gangway for observers, normally aristocrats, who abused their position to influence an individual’s vote. When the two consuls tried to persuade the Senate to block the bill, Marius threatened them with imprisonment, and the bill was carried.

Marius showed himself no unprincipled candidate for popular favour, for he vetoed a popular grain bill, and the following years offered him little promise of a conspicuous career. He failed to secure the aedileship (control of markets and police) and was only just elected praetor (judicial magistrate) for the year 115 after bribing heavily, for which he was lucky to escape condemnation in court. The next year he governed Further Spain, campaigned successfully against bandits, and laid a foundation for great personal wealth through mining investments. After that, he made a good marriage into a patrician family that, after long obscurity, was on the point of strong political revival. His wife was Julia, the aunt of Julius Caesar.

Election to the consulship

The command in the war against Jugurtha (who was now Numidian king) was given to Quintus Metellus, and Marius was invited to join Metellus’ staff. After defeating Jugurtha in pitched battle, Metellus was less successful in later guerrilla warfare, and this failure was exaggerated by Marius in his public statements when at the end of 108 he returned to Rome to seek the consulship (chief magistracy). Marius was elected on the equestrian and popular vote and, to Metellus’ bitter chagrin, appointed by a popular bill to succeed Metellus at once in the African command.

In recruiting fresh troops, Marius broke with custom, because of a manpower shortage, by enrolling volunteers from outside the propertied classes, which alone had previously been liable for service. In Africa he kept Jugurtha on the run, and in 105 Jugurtha was captured, betrayed by his ally, King Bocchus of Mauretania—not to Marius himself but to Sulla, considered a rather disreputable young aristocrat, who had joined Marius’ staff as quaestor in 107. Sulla had the incident engraved on his seal, provoking Marius’ jealousy.

The victory, however, was Marius’, and he was elected consul again for 104—at the start of which year he celebrated a triumph and Jugurtha was executed—in order to take command against an alarming invasion of the Cimbri and Teutones, who had defeated a succession of Roman armies in the north, the last in disgraceful circumstances in 105. For this war, Marius used fresh troops raised by Rutilius Rufus, consul in 105, and excellently trained in commando tactics by gladiatorial instructors. With them, Marius defeated the Teutones at Aquae Sextiae (modern Aix-en-Provence, Fr.) in 102 and in 101 came to the support of the consul of 102, Quintus Lutatius Catulus, who had suffered a serious setback; together they defeated the Cimbri at the Vercellae, near modern Rovigo in the Po River valley, and the danger was over. This was the apex of Marius’ success. He had been consul every year since 104, and he was elected again the year 100. With Catulus he celebrated a joint triumph, but already there was bad feeling between them. Marius claimed the whole credit for the victory; Catulus and Sulla gave very different accounts of the event in their memoirs.

Marius had always had equestrian support, not only because his origins lay in that class but also because wars were bad for trade, and Marius had brought serious wars to an end. The Roman populace liked him because he was not an aristocrat. He had the further support of his veterans, for it was in their interest to stick closely to their general. Marius perhaps did not realize the potency of their force, one that Sulla, Caesar, and Octavian employed with overpowering effect later.

Fall from power

The year 100 saw Marius fail disastrously as a politician. Saturninus was tribune for the second time, and Glaucia was praetor; given the poverty of surviving sources, it is extremely difficult to understand either their political aims or Marius’ relationship to them. The three shared a common hatred of Metellus, who, as censor in 102, had tried to remove Saturninus and Glaucia from the Senate, and in 103 Saturninus had carried a bill, evidently in Marius’ interest, for the settlement of veterans in Africa. Now, with the inevitability of civil disorder—for the Roman populace opposed his measures—Saturninus introduced bills for land distribution of Cimbric territory in the north to Romans living in the country, and probably to Italians, and for the settlement of veterans, evidently including allied troops, in colonies overseas. This bill may have included a powerful command for Marius to supervise the resettlement of the veterans—empowering him to give Roman citizenship to a certain number of the new settlers in each colony.

Marius had already violated the law by granting citizenship on the battlefield to two cohorts of Italians (Camertes) who fought under him against the Cimbri in 101, and conceivably Saturninus and Marius were agreeable to a program of extensive enfranchisement of Italians by means of the new colonial settlements. A breach between them occurred, possibly because Marius, in his jealous way, thought that Saturninus was stealing some of his own thunder or possibly because Saturninus’ lawlessness had reached a pitch that no self-respecting consul could tolerate.

First the land and colonial bill was passed, but with blatant illegality; it required senators to take an oath within five days to observe it. After misleading statements about his own intention, Marius took the oath. Metellus refused, however, presumably because of the way in which the bill had been carried, and, forestalling condemnation in the treason court, he retired to Greece; later he was officially exiled. At the tribunician elections for 99, Saturninus was reelected together with a pretender who, already heavily discredited, claimed to be the son of Tiberius Gracchus. At the consular elections, with Glaucia as a candidate, Marcus Antonius, the orator, was elected, and Gaius Memmius, a man with an excellent popular record, was murdered. In the ensuing pandemonium the Senate passed the “last decree,” calling on the consuls to save the state. Through Marius’ action Saturninus and Glaucia were captured on the Capitol and imprisoned in the Senate house; then a mob stripped off the roof and stoned them to death. Although this was no responsibility of Marius, he was smeared as a man who betrayed not only his enemies but also his friends.

Later years

Rather than attend the inevitable recall of Metellus from exile, Marius went to the east in 99 and there met Mithradates VI of Pontus. He was elected to a priesthood (the augurship) but wisely withdrew his candidature for the censorship of 97. He acted as a background figure in the not fully unraveled politics of the 90s and successfully opposed an attempt in 95 to disenfranchise men to whom he had given citizenship under the terms of Saturninus’ colonial bill, though the law itself had been shelved. In 92 he supported the scandalous prosecution and condemnation of his old associate Rutilius Rufus (in fact a model administrator) for alleged misgovernment of Asia.

Marius was now beginning to show his age. In an Italian rebellion (the Social War) of 90–88, he campaigned under the consul Rutilius Lupus, a soldier far his inferior. In 88, when the tribune Sulpicius Rufus proposed the transfer of the Asian command from the consul Sulla to Marius, presumably on the ground that Marius alone was sufficiently experienced to conduct such a critical war, there was violent public opposition to Sulla in Rome. Sulla went to his army in Campania and marched with it on Rome. Sulpicius’ measures were rescinded, and Marius was exiled.

After a series of near catastrophes, all much embroidered in the telling, Marius escaped safely to Africa. In 87, when Sulla was fighting in Greece, disorder in Rome led to the consul Cinna being dismissed. Marius landed in Etruria, raised an army, sacked Ostia, and, by joining forces with Cinna, captured Rome; both Marius and Cinna were elected consuls for 86, Marius for the seventh time. Hideous massacre followed as Marius ordered the deaths of Marcus Antonius, Lutatius Catulus, Publicus Licinius Crassus, and other distinguished men whom he considered to have behaved with treacherous ingratitude toward him. By this time he was hardly sane, and his death, in 86, was a godsend for enemies and friends alike. If the outcome of his proscriptions was considered to be less disastrous than that of the later proscriptions of Sulla, it was only because they lasted for a shorter time.

Marius’ only son died as consul fighting against Sulla in 82. His widow survived until 69 and received the unusual honour, for a woman, of a public funeral oration by her nephew Julius Caesar, who later won great popularity by restoring to the Capitol Marius’ trophies, which Sulla had removed.

Marius was commemorated by the name Mariana given to Uchi Majus and Thibaris (two African settlements) and to a colony in Corsica, and by the Fossa Mariana, a canal dug by his soldiers at the mouth of the Rhône River. (Source: https://www.britannica.com/biography/...)

More:

http://www.roman-empire.net/republic/...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaius_M...

http://www.unrv.com/empire/gaius-mari...

http://faculty.vassar.edu/jolott/old_...

http://military.wikia.com/wiki/Gaius_...

(no image) Gaius Marius: A Political Biography by Richard J. Evans (no photo)

by Christopher Anthony Matthew (no photo)

by Christopher Anthony Matthew (no photo) by Marc Hyden (no photo)

by Marc Hyden (no photo) by Lawrence Keppie (no photo)

by Lawrence Keppie (no photo) by

by

Plutarch

Plutarch

Cursus Honorum

The cursus honorum (Latin: "course of offices") was the sequential order of public offices held by aspiring politicians in both the Roman Republic and the early Roman Empire. It was designed for men of senatorial rank. The cursus honorum comprised a mixture of military and political administration posts. Each office had a minimum age for election. There were minimum intervals between holding successive offices and laws forbade repeating an office.

These rules were altered and flagrantly ignored in the course of the last century of the Republic. For example, Gaius Marius held consulships for five years in a row between 104 BC and 100 BC. Officially presented as opportunities for public service, the offices often became mere opportunities for self-aggrandizement. The reforms of Lucius Cornelius Sulla required a ten-year period between holding another term in the same office.

To have held each office at the youngest possible age (suo anno, "in his year") was considered a great political success, since to miss out on a praetorship at 39 meant that one could not become consul at 42. Cicero expressed extreme pride not only in being a novus homo ("new man"; comparable to a "self-made man") who became consul even though none of his ancestors had ever served as a consul, but also in having become consul "in his year".

Quaestor

The first official post was that of quaestor. Candidates had to be at least 30 years old. However, men of patrician rank could subtract two years from this and other minimum age requirements.

Twenty quaestors served in the financial administration at Rome or as second-in-command to a governor in the provinces. They could also serve as the paymaster for a legion. A young man who obtained this job was expected to become a very important official. An additional task of all quaestors was the supervision of public games. As a quaestor, an official was allowed to wear the toga praetexta, but was not escorted by lictors, nor did he possess imperium.

Aedile

At 36 years of age, former quaestors could stand for election to one of the aedile positions. Of these aediles, two were plebeian and two were patrician, with the patrician aediles called Curule Aediles. The plebeian aediles were elected by the Plebeian Council and the curule aediles were either elected by the Tribal Assembly or appointed by the reigning consul. The aediles had administrative responsibilities in Rome. They had to take care of the temples (whence their title, from the Latin aedes, "temple"), organize games, and be responsible for the maintenance of the public buildings in Rome. Moreover, they took charge of Rome's water and food supplies; in their capacity as market superintendents, they served sometimes as judges in mercantile affairs.

The Aedile was the supervisor of public works; the words "edifice" and "edification" stem from the same root. He oversaw the public works, temples and markets. Therefore, the Aediles would have been in some cooperation with the current Censors, who had similar or related duties. Also they oversaw the organization of festivals and games (ludi), which made this a very sought-after office for a career minded politician of the late republic, as it was a good means of gaining popularity by staging spectacles.

Curule Aediles were added at a later date in the 4th century BC, and their duties do not differ substantially from plebeian aediles. However, unlike plebeian aediles, curule aediles were allowed certain symbols of rank—the sella curulis or 'curule chair,' for example—and only patricians could stand for election to curule aedile. This later changed, and both Plebeians and Patricians could stand for Curule Aedileship.

The elections for Curule Aedile were at first alternated between Patricians and Plebeians, until late in the 2nd century BC, when the practice was abandoned and both classes became free to run during all years.

While part of the cursus honorum, this step was optional and not required to hold future offices. Though the office was usually held after the quaestorship and before the praetorship, there are some cases with former praetors serving as aediles.

Praetor

After holding either the office of quaestor or aedile, a man of 39 years could run for praetor. The number of Praetors elected varied through history, generally increasing with time. During the republic, six or eight were generally elected each year to serve judicial functions throughout Rome and other governmental responsibilities. In the absence of the Consuls, a Praetor would be given command of the garrison in Rome or in Italy. Also, a Praetor could exercise the functions of the Consuls throughout Rome, but their main function was that of a judge. They would preside over trials involving criminal acts as well as grant court orders or validate "illegal" acts as acts of administering justice. As a Praetor, a magistrate was escorted by six lictors, and wielded imperium. After a term as Praetor, the magistrate would serve as a provincial governor in the office of Propraetor, wielding Propraetor imperium, commanding the province’s legions, and possessing ultimate authority within his province(s).

Of all the Praetors, two were more prestigious than the others. The first was the Praetor Peregrinus, who was the chief judge in trials involving one or more foreigners. The other was the Praetor Urbanus, the chief judicial office in Rome. He had the power to overturn any verdict by any other courts, and served as judge in cases involving criminal charges against provincial governors. The Praetor Urbanus was not allowed to leave the city for more than ten days. If one of these two Praetors was absent from Rome, the other would perform the duties of both.

Consul

The office of consul was the most prestigious of all, and represented the summit of a successful career. The minimum age was 42 for plebeians and 40 for patricians. Years were identified by the names of the two consuls elected for a particular year; for instance, M. Messalla et M. Pisone consulibus, "in the consulship of Messalla and Piso," dates an event to 61 BC. Consuls were responsible for the city's political agenda, commanded large-scale armies and controlled important provinces. The consuls served for only a year (a restriction intended to limit the amassing of power by individuals) and could only rule when they agreed, because each consul could veto the other's decision.