The Evolution of Science Fiction discussion

This topic is about

Flatland

Group Reads 2018

>

April 2018 Group Read: Flatland a Romance of Many Dimensions

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Jo

(new)

-

rated it 3 stars

Apr 01, 2018 08:20AM

This is to discuss April's group read, Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions.

This is to discuss April's group read, Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions.

reply

|

flag

I've been meaning to read Flatland for sometime so now I have no excuses! It is available for download for free from Project Gutenburg

I've been meaning to read Flatland for sometime so now I have no excuses! It is available for download for free from Project Gutenburg www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/search/?quer...

There are three versions available.

I'm reading an annotated version. The annotator suggests reading the preface afterwards, as an epilogue. I doubt it really matters much. We probably all already know the basic idea.

I finished this one a few days ago. It's interesting for a book that was written over 130 years ago. I liked the second half a little better than the first half.

I finished this one a few days ago. It's interesting for a book that was written over 130 years ago. I liked the second half a little better than the first half.

The annotated edition states that Mr. Abbot Abbot would be surprised to learn that this book is currently read most as an introduction to the topic of higher dimensions. Abbot Abbot (both parents were cousins named Abbot, so he was A. Square) was really mostly about his current society.

I'm not finished with it, and I'm sure I won't understand all those references anyway, but here is one thing I think I understood so far. Victorian society was fascinated by the Greeks and thought that England should learn from them and make their society more like the Greek. Abbot was, among other things, trying to point out that the Greeks did many things that should not be emulated. Like women having almost no rights, and "defective" children being left out to die. So when you see things like that in the book, you shouldn't assume that Abbot really thinks those are good ideas.

I'm not finished with it, and I'm sure I won't understand all those references anyway, but here is one thing I think I understood so far. Victorian society was fascinated by the Greeks and thought that England should learn from them and make their society more like the Greek. Abbot was, among other things, trying to point out that the Greeks did many things that should not be emulated. Like women having almost no rights, and "defective" children being left out to die. So when you see things like that in the book, you shouldn't assume that Abbot really thinks those are good ideas.

I read Flatland about a year and a half ago. It's a very original science fiction story, a clever concept. I wrote this brief review which is mostly spoiler, not that it matters all that much: https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...

I read Flatland about a year and a half ago. It's a very original science fiction story, a clever concept. I wrote this brief review which is mostly spoiler, not that it matters all that much: https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...

I read an annotated version. I'll comment first on the book itself, then separately on the annotations.

In brief, I've always intended to read it, and am glad I can finally check it off my list, but I didn't get anything much from it that I didn't already know.

I was first introduced to the ideas of higher dimensions (other than a vague introduction from A Wrinkle in Time) by the T.V. show Cosmos. (The original one by Carl Sagan.) It was fascinating and mind-expanding. If I remember correctly, Sagan used examples from this book. I've read further books of math and physics (and have a degree in physics). The concepts are very clear, but I am sadly, completely unable to mentally picture anything with more than 3 dimensions. Just like poor A Square can't visualize 3 dimensions in his mind after he returns to 2 dimensions.

It fascinates me that people have been able to prove topological principles and the possible numbers of "regular" polyhedra in higher dimensions. It seems like one would need to be able to visualize such things to make much progress.

Apart from the geometry lessons, the rest was pretty dull.

In brief, I've always intended to read it, and am glad I can finally check it off my list, but I didn't get anything much from it that I didn't already know.

I was first introduced to the ideas of higher dimensions (other than a vague introduction from A Wrinkle in Time) by the T.V. show Cosmos. (The original one by Carl Sagan.) It was fascinating and mind-expanding. If I remember correctly, Sagan used examples from this book. I've read further books of math and physics (and have a degree in physics). The concepts are very clear, but I am sadly, completely unable to mentally picture anything with more than 3 dimensions. Just like poor A Square can't visualize 3 dimensions in his mind after he returns to 2 dimensions.

It fascinates me that people have been able to prove topological principles and the possible numbers of "regular" polyhedra in higher dimensions. It seems like one would need to be able to visualize such things to make much progress.

Apart from the geometry lessons, the rest was pretty dull.

The version I read had annotations from Thomas F. Banchoff, and William F. Lindgren. There are other annotated versions, such as one by Ian Stewert, which I assume focus more on the math. These annotations were about Abbot and his world.

The annotations, presented on alternating pages from the main text, plus more at the end, were longer than the main text. Many were superfluous definitions of words or phrases that I understood easily. But I'll mention some bits I found interesting.

Flatland was intentionally written in outdated language. Partly to call to mind ancient societies, particularly Greek. The parable of Plato's cave was among the intended references. English education of the time was heavy on Greek texts. Readers of the time would have picked-up the Greek references and the many near-quotes of Shakespeare that went over my head. (If you don't recognize them, don't worry. It really doesn't matter.)

Abbot was interested in evolution of English and has published a book on differences between Shakespeare's English and modern (Victorian) English. That book is still used today (and I may read it.) He also promoted the bizarre idea that students should be taught English grammar, not just Greek and Latin. His grammar work "How to write clearly" is still read. He also championed the education of women.

He went, by chance, to one of the few schools of the time that taught as much math as classics. He did well in math, but later thought that it was a bad idea that his school spent so much time on it. He feels he missed having more of the classical education.

Abbot promoted a version of Christianity without miracles. He thought such a version could be used to attract more modern converts. These ideas are apparently included in Philochristus: Memoirs of a Disciple of the Lord, which is sort of modern Gospel supposedly written by a follower of Jesus. It is available for free online. I tried a chapter (about the events with the loaves and fishes) and whatever points he was making were lost on me. It still seemed like a miraculous event in his telling, and the fake Olde English made it more opaque. This book was not very well received. When A. Square laments at not being understood, it is easy to think Abbot was talking about himself. However, his books of textual analysis showing the similarities between Mathew, Mark, and Luke, and the differences from John, were very well received and still influential.

Flatland was initially published anonymously (like "Philochristus"). It was fairly well received. When a reviewer made comments about how the flatlanders must have some thickness, Abbot responded in a letter written by the character A Square. Parts of that letter end up as the Prologue (or Epilogue, depending on which version you read).

Incidentally, he is not the brother of Evelyn Abbott, even though the current Goodreads description says so. That was a mistake made in an early Encyclopedia Britannica that has stuck around.

He seems like a pretty cool guy.

The annotations, presented on alternating pages from the main text, plus more at the end, were longer than the main text. Many were superfluous definitions of words or phrases that I understood easily. But I'll mention some bits I found interesting.

Flatland was intentionally written in outdated language. Partly to call to mind ancient societies, particularly Greek. The parable of Plato's cave was among the intended references. English education of the time was heavy on Greek texts. Readers of the time would have picked-up the Greek references and the many near-quotes of Shakespeare that went over my head. (If you don't recognize them, don't worry. It really doesn't matter.)

Abbot was interested in evolution of English and has published a book on differences between Shakespeare's English and modern (Victorian) English. That book is still used today (and I may read it.) He also promoted the bizarre idea that students should be taught English grammar, not just Greek and Latin. His grammar work "How to write clearly" is still read. He also championed the education of women.

He went, by chance, to one of the few schools of the time that taught as much math as classics. He did well in math, but later thought that it was a bad idea that his school spent so much time on it. He feels he missed having more of the classical education.

Abbot promoted a version of Christianity without miracles. He thought such a version could be used to attract more modern converts. These ideas are apparently included in Philochristus: Memoirs of a Disciple of the Lord, which is sort of modern Gospel supposedly written by a follower of Jesus. It is available for free online. I tried a chapter (about the events with the loaves and fishes) and whatever points he was making were lost on me. It still seemed like a miraculous event in his telling, and the fake Olde English made it more opaque. This book was not very well received. When A. Square laments at not being understood, it is easy to think Abbot was talking about himself. However, his books of textual analysis showing the similarities between Mathew, Mark, and Luke, and the differences from John, were very well received and still influential.

Flatland was initially published anonymously (like "Philochristus"). It was fairly well received. When a reviewer made comments about how the flatlanders must have some thickness, Abbot responded in a letter written by the character A Square. Parts of that letter end up as the Prologue (or Epilogue, depending on which version you read).

Incidentally, he is not the brother of Evelyn Abbott, even though the current Goodreads description says so. That was a mistake made in an early Encyclopedia Britannica that has stuck around.

He seems like a pretty cool guy.

Thanks for the details, Ed. I'm going to get the Librivox audiobook of this & give it a try. I've also heard about it for years, but never managed to read it due to the language. It bores me to tears in text.

Thanks for the details, Ed. I'm going to get the Librivox audiobook of this & give it a try. I've also heard about it for years, but never managed to read it due to the language. It bores me to tears in text.

I just finished the book and thought it was more entertaining in part two. I am glad I read the book because it made a nice change from some of the more serious books I have recently finished reading.

I just finished the book and thought it was more entertaining in part two. I am glad I read the book because it made a nice change from some of the more serious books I have recently finished reading.

Rosemarie wrote: "I just finished the book and thought it was more entertaining in part two. I am glad I read the book because it made a nice change from some of the more serious books I have recently finished reading."

Rosemarie wrote: "I just finished the book and thought it was more entertaining in part two. I am glad I read the book because it made a nice change from some of the more serious books I have recently finished reading."I also liked the second half better. I especially enjoyed how the 2 dimensional square was unable to visualize 3 dimensional space, in much the same way that I (and hopefully others as well) have trouble envisioning 4 or more dimensions.

I think it is pretty much impossible for us to really envision 4 or more dimensions. But there is an app or game called "4D Toys" that lets you play around with 4D objects, and maybe you can develop some sort of intuition about how they would appear to us who can only see 3D.

Search for "4D Toys" on "Steam" or the Apple store or wherever you get your games, or on your favorite free video sharing site.

Search for "4D Toys" on "Steam" or the Apple store or wherever you get your games, or on your favorite free video sharing site.

No, you are not wrong. Time is sometimes called a 4th dimension.

But here we are talking about 4 or more spatial dimensions.

But here we are talking about 4 or more spatial dimensions.

I read the book in January. I didn’t really like it, but like others have commented, I preferred the 2nd half. I read the Dover edition which was not annotated, that I recall. Fortunately, it was a very short book.

I read the book in January. I didn’t really like it, but like others have commented, I preferred the 2nd half. I read the Dover edition which was not annotated, that I recall. Fortunately, it was a very short book.

I quite enjoyed it, to me there was not much difference between the first and second half. I was quite amused by his section on women, I couldn't work out if it was meant to be ironic or not. As Ed mentioned that he supported women's education, I can read it in a better light :-)

I quite enjoyed it, to me there was not much difference between the first and second half. I was quite amused by his section on women, I couldn't work out if it was meant to be ironic or not. As Ed mentioned that he supported women's education, I can read it in a better light :-)I don't know if it's just this period but a lot of the older books do tend to be "Science" fiction with the emphasis on the science rather than the fiction and usually a lot of details for the science. (I exclude H. G. Wells here).

Just finished it yesterday, found it quite strange. I read the version from project Gutenberg, w/o annotations. The language for me, non-native speaker, was unusual but passable. The story reminded me of Plato's works but I wasn't sure whether it is a satire or true beliefs of the author, not only the place of women, but hints on Lambroso physiognomy as well. Math part is an affront to my euclidean geometry, where he states that line is really a thin parallelogram and where 2D still has height, just quite small

Just finished it yesterday, found it quite strange. I read the version from project Gutenberg, w/o annotations. The language for me, non-native speaker, was unusual but passable. The story reminded me of Plato's works but I wasn't sure whether it is a satire or true beliefs of the author, not only the place of women, but hints on Lambroso physiognomy as well. Math part is an affront to my euclidean geometry, where he states that line is really a thin parallelogram and where 2D still has height, just quite small

I finally got around to reading this yesterday & enjoyed it more than I expected to. Wish I'd read it sooner. I gave it a 4 star review here:

I finally got around to reading this yesterday & enjoyed it more than I expected to. Wish I'd read it sooner. I gave it a 4 star review here:https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...

Oleksandr wrote: "he states that line is really a thin parallelogram and where 2D still has height, just quite small..."

If I remember correctly, that bit was added in the 2nd edition in response to a reviewer. The reviewer thought that the shapes would have to have some thickness in order for light to bounce off the edges. In the real world, that may be true, because Maxwell's equations for light require at least 3 physical dimensions, but we can certainly imagine a mathematical 2D world with no third dimension. The story wouldn't really change whether we regard these creatures as living in a truly 2D world, or a world that is simply 2D-for-all-practical-purposes.

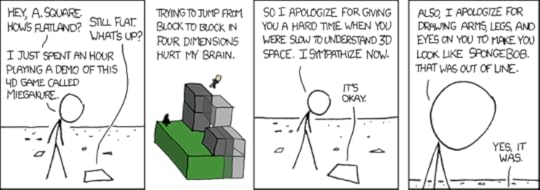

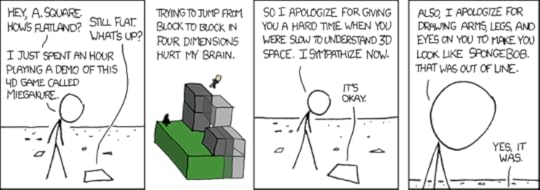

From XKCD

From XKCD

If I remember correctly, that bit was added in the 2nd edition in response to a reviewer. The reviewer thought that the shapes would have to have some thickness in order for light to bounce off the edges. In the real world, that may be true, because Maxwell's equations for light require at least 3 physical dimensions, but we can certainly imagine a mathematical 2D world with no third dimension. The story wouldn't really change whether we regard these creatures as living in a truly 2D world, or a world that is simply 2D-for-all-practical-purposes.

From XKCD

From XKCD

Before reading this, I had read the more recent VAS: An Opera in Flatland: A Novel.. Before, I had always thought that Flatland was only about mathematical ideas, but I gathered from "VAS" that there was some sort of social commentary also going on, and that was why I was eager to pick up Flatland.

VAS is an interesting book, but not really recommended to SF fans. As another reviewer said, it is fiction about science, but not science fiction in the way that term is usually understood. And the science in question is genetics. ("Vas" is short for "Vasectomy".) It has really creative visual layout, even includes a chapter in the form of a comic book, and one version comes with a soundtrack on CD. But for all that creativity, it was only 3 stars from me. Your mileage may vary.

VAS is an interesting book, but not really recommended to SF fans. As another reviewer said, it is fiction about science, but not science fiction in the way that term is usually understood. And the science in question is genetics. ("Vas" is short for "Vasectomy".) It has really creative visual layout, even includes a chapter in the form of a comic book, and one version comes with a soundtrack on CD. But for all that creativity, it was only 3 stars from me. Your mileage may vary.

Ed wrote: "The version I read had annotations from Thomas F. Banchoff, and William F. Lindgren. There are other annotated versions, such as one by Ian Stewert, which I assume focus more on the math. These ann..."

Ed wrote: "The version I read had annotations from Thomas F. Banchoff, and William F. Lindgren. There are other annotated versions, such as one by Ian Stewert, which I assume focus more on the math. These ann..."Fascinating. Thanks, Ed.

I finally finished it. It is a decend read for those interested in proto-sci-fi, but it is limited. The author is very imaginative when it comes to imagining a two dimensional reality.

I finally finished it. It is a decend read for those interested in proto-sci-fi, but it is limited. The author is very imaginative when it comes to imagining a two dimensional reality. It reminded me of Micromegas by Voltaire. Both authors are doing satires and both authors are talking about perspectives, They use aliens and focus on geometry or seize to achieve this.

I'm reading next month's group read (Stranger in a Strange Land) and I notice a not so suttle reference to Flatland. Amusing.

I just read that section in Stranger in a Strange Land as well.

I just read that section in Stranger in a Strange Land as well. I enjoy the fact that I had read a book mentioned by Heinlein.

Books mentioned in this topic

Micromegas (other topics)VAS: An Opera in Flatland (other topics)

Philochristus: Memoirs of a Disciple of the Lord (other topics)

A Wrinkle in Time (other topics)

Cosmos (other topics)