Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses discussion

The Metamorphoses - The 15 Books

>

Book Two - 19th November 2018

message 1:

by

Kalliope

(new)

Sep 22, 2018 06:31AM

Discussion of the Second Book.

Discussion of the Second Book.

reply

|

flag

Elena wrote: "We are surrounded by fires in California and I reread the Phaethon episode as a terrifyingly realistic short story...."

Elena wrote: "We are surrounded by fires in California and I reread the Phaethon episode as a terrifyingly realistic short story...."I was trying to read the beginning of book two last night while my husband watched images of the California fires on tv, Elena, and I had the same thought.

I pitied poor Earth as she pleaded for help:

"Apply some speedy cure, prevent our fate,

And succour Nature, ere it be too late."

She cea'sd, for choak'd with vapours round her spread,

Down to the deepest shades she sunk her head.

Garth translaction, 1717

I myself have no words for what is going on, but my reaction to the fire is best expressed by a poet who lived 2,000 years ago...

I myself have no words for what is going on, but my reaction to the fire is best expressed by a poet who lived 2,000 years ago...

I found the first book very much like genesis in that Ovid proposes that the world was created by a single define intelligence who creates order out of chaos. In Book II we are clearly into the theme of love.

I found the first book very much like genesis in that Ovid proposes that the world was created by a single define intelligence who creates order out of chaos. In Book II we are clearly into the theme of love.

Czarny wrote: "I found the first book very much like genesis in that Ovid proposes that the world was created by a single define intelligence who creates order out of chaos. In Book II we are clearly into the theme of love"

Czarny wrote: "I found the first book very much like genesis in that Ovid proposes that the world was created by a single define intelligence who creates order out of chaos. In Book II we are clearly into the theme of love"I am looking forward to some romance as well. Compared to the Bible, however, Ovid's genesis is much more prolific. I counted five different versions of the creation of man:

1) out of divine semen (79)

2) out of the earth which retained some aethereal semen (81)

3) out of the earth soaked with the blood of the Giants (160)

4) by Prometheus (as mentioned in (363)

5) out of the rocks that Deucalion and Pyrrha threw behind them (400ff.)

Great, Peter. Isn't Ovid somewhat poking fun at, or, at least, drawing attention to, the numerous 'versions' that existed in his time of the creation?

Great, Peter. Isn't Ovid somewhat poking fun at, or, at least, drawing attention to, the numerous 'versions' that existed in his time of the creation?

Roman Clodia wrote: "Great, Peter. Isn't Ovid somewhat poking fun at, or, at least, drawing attention to, the numerous 'versions' that existed in his time of the creation?"

Roman Clodia wrote: "Great, Peter. Isn't Ovid somewhat poking fun at, or, at least, drawing attention to, the numerous 'versions' that existed in his time of the creation?"RC and Peter... yes... I begin to ask myself how much of what Ovid is writing about, did he believe in...

Certainly not an expert, but this reads very different from the much more earnest Greek accounts.

When posting paintings, I feel as if we are reversing Ovid's ecphrasis, the written description of images, turned back into images.

When posting paintings, I feel as if we are reversing Ovid's ecphrasis, the written description of images, turned back into images.The beginning of Book II describing the 'artwork' of the doors of of the palace of the Sun, as made by Vulcan, is a beautiful echprastic section.

No wonder Vulcan, or the 'craftsman god', fascinated European painters... their 'godly' alter-ego.

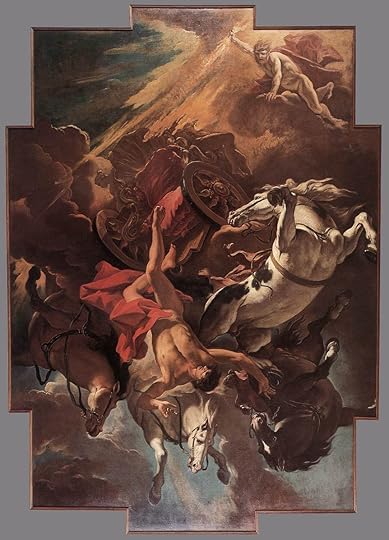

To depict Phaeton's fall is a great challenge and Rubens, unsurprisingly, felt he could meet it..

To depict Phaeton's fall is a great challenge and Rubens, unsurprisingly, felt he could meet it..Rubens. Fall of Phaeton. 1606-8. Washington National Gallery.

We see Phaeton drawing an arc while falling, and the four horses. The Earth is already beginning to burn, and Apollo/Helios is shown as Light.

It is not very large. This theme and rendition would call for a huge painting. But this is a young Rubens still; he painted it in Italy while still being an 'apprentice' of sorts, and who had to prove his powers. Far from the huge painting of the Adoration of the Magi that he painted for the Antwerp City Hall.

The young Rubens, however and unlike Phaeton, could rise to the heights and control 'his' chariot....

I am finding this a rather confusing book. But more on that when I have had more time to puzzle it out.

I am finding this a rather confusing book. But more on that when I have had more time to puzzle it out.One story, though, jumps out at me immediately: that of Calisto (I use the Italian spelling; Ovid does not name her). Francesco Cavalli wrote a delicious opera on the subject in 1651, to a superb libretto by Giovanni Faustini. I was involved in the first modern revival of the opera at Glyndebourne in 1975; there is a rather poor video of that production here; various clips from more modern productions and a complete audio recording can be found online.

I have since done three productions of my own. The photos below are from the most recent of these—also the one with the lowest budget; it had a very simple set. They show, in turn, Jove and Mercury when they first spy Calisto; Calisto herself; and Jove as Diana (now sung by a mezzo) preparing to make his first approach.

In preparation for this production, I also wrote a long poem, "Calisto Retold," trying to recapture the particular mixture of myth, pathos, and outright comedy in Faustini's libretto. The passage below describes the scene that follows from the third picture above. Italicized portions are more or less translations of the sung text (which is really quite close to Ovid); the others are my own storytelling. R.

======

Now Jupiter returns, but who would know him,======

in bodice, dress, and buskins, with a bow?

The image of Diana (though advised

by Mercury to cut down the machismo),

he woos Calisto with unmatched charisma:

Budding blossom of my bosom,

little virgin, just emerging,

how could you be absent from your goddess?

For without you, mad about you,

I've no treasure, find no pleasure

in the hunt without my little novice.

He's not the greatest poet, but Calisto

sees no falseness in his cloying strain:

O Diana, dearest diva, you

who guide the silver orb around the earth!

Wild beasts took me from your presence,

depriving me of your beloved worth.

(We do not need to quote their further blisses,

for Jove intends to put things right with kisses.)

Calisto readily agrees. (Not here, not now—

this is a family show.) In ladylike

decorum, Jove suggests that they adjourn:

some grove more shady… brook more murmury…

some love-nest where they will not be observed.

So off they go, in happy roundelay,

exchanging kisses all the livelong day.

Incidentally, the Calisto of Cavalli and Faustini is not at all resistant to Jove's approaches, and does not even know what has happened to her. When she sees Diana, her immediate response is to thank her for what has happened and ask for more. And when answering Juno's question, "Did anything else happen between your goddess and you?", all she can say is "A certain sweetness that… I don't know how to tell you." Hmm.

I have a lot of trouble with Ovid's work, especially in that it often appears to me more of a name-dropping catalogue of his erudition in Greek, Roman and other lore. However, the story of Phaethon's fateful chariot ride stuck out as an impressive exception to this general rule.

I have a lot of trouble with Ovid's work, especially in that it often appears to me more of a name-dropping catalogue of his erudition in Greek, Roman and other lore. However, the story of Phaethon's fateful chariot ride stuck out as an impressive exception to this general rule. In its seven or eight pages, he did keep himself down to only two or three score proper nouns - particularly of the rivers which were affected by the oppressive heat. But after hearing Neptune's complaints to Jove about the runaway sun, we get what was to me the most poignant part of the passage: the complaint of the 'earth goddess' who, in most uncharacteristic fashion for Ovid, goes unnamed? Any idea why?

Also, other than being burned to a crisp by Jove's awesome strike, in what manner was Phaethon 'metamorphosed'?

Ted Hughes has a very full treatment of the Phaethon story in his Tales from Ovid, Although I haven't counted words, I suspect it is quite a bit longer than the original. He starts, for example, with a page or more giving the back-story that explains Phaethon's doubts about his parentage, which of course set the whole thing in motion.

Ted Hughes has a very full treatment of the Phaethon story in his Tales from Ovid, Although I haven't counted words, I suspect it is quite a bit longer than the original. He starts, for example, with a page or more giving the back-story that explains Phaethon's doubts about his parentage, which of course set the whole thing in motion. Another thing that Hughes does—quite unusual for him—is to tell most of the first part of the story in more or less regular five-line stanzas (38 of them, to be precise). He seems to be setting up a sense of order—only to destabilize this order into irregular line-lengths and lurching phrases when Phaeton gives his borrowed steeds their rein:

They burst upwards, they hurled themselves

Ahead of themselves,

Winged hooves churning cloud.

They outstripped those dawn winds from the East—

But from the first moment

They felt something wrong with the chariot.

The load was too light.

More like a light pinnace

Without ballast or cargo,

Without the deep-keeled weight to hold a course,

Bucking and flipping

At every wave,

Sliding away sidelong at every gust.

The chariot

Bounced and was whisked about as if it were empty.

Kalliope wrote: "To depict Phaeton's fall is a great challenge and Rubens, unsurprisingly, felt he could meet it."

Kalliope wrote: "To depict Phaeton's fall is a great challenge and Rubens, unsurprisingly, felt he could meet it."If this is in Washington, I should know it, but I don't. It is truly magnificent, but I wonder if it is on permanent display?

[It is possible, though, that I have simply missed it. We visit the Washington NG about twice a year, but almost always for special exhibits, taking in only those sections of the permanent collection that catch our fancy that day. It occurs to me now that I don't know where the Rubens room is; next visit, I will make a point of looking out for it. R.]

Kalliope wrote: "The beginning of Book II describing the 'artwork' of the doors of of the palace of the Sun, as made by Vulcan, is a beautiful ecphrastic section."

Kalliope wrote: "The beginning of Book II describing the 'artwork' of the doors of of the palace of the Sun, as made by Vulcan, is a beautiful ecphrastic section."Yes, that struck me too. And I immediately started wondering whether and where we could find the "reverse-ecphrastic version" (I love this concept!) of those doors as an actual artwork. But I didn't look, because I realized that even if some artist had attempted it, it would pale beside the original, caught between the competing demands of detail and scale.

So this is an example of ecphrasis that is not a mere substitute for some other medium, but a superior art form, because it describes an imaginary artwork whose physical representation could never match its presence in the mind. R.

Steve wrote: "…the complaint of the 'earth goddess' who, in most uncharacteristic fashion for Ovid, goes unnamed? Any idea why?"

Steve wrote: "…the complaint of the 'earth goddess' who, in most uncharacteristic fashion for Ovid, goes unnamed? Any idea why?"Thanks, Steve. I also noticed this throughout this book. I mentioned above that we get the name of Calisto from somewhere else, not from Ovid. Europa is just "Agenor's daughter." And there are many other characters who do not seem to be named at all. R.

Steve wrote: "Also, other than being burned to a crisp by Jove's awesome strike, in what manner was Phaethon 'metamorphosed'?"

Steve wrote: "Also, other than being burned to a crisp by Jove's awesome strike, in what manner was Phaethon 'metamorphosed'?"I suspect this is a question for Roman Clodia or some other literary historian. Just because the book is titled "Metamorphoses," does it necessarily mean that every story in it must involve a transformation? I don't know. R.

Roger wrote: "Steve wrote: "Also, other than being burned to a crisp by Jove's awesome strike, in what manner was Phaethon 'metamorphosed'?"

Roger wrote: "Steve wrote: "Also, other than being burned to a crisp by Jove's awesome strike, in what manner was Phaethon 'metamorphosed'?"As Roger suggests, not every subject of each story is changed ~ and I'd say that one thing we can expect from Ovid is to have expectations overturned in some way.

I haven't started re-reading Book 2 yet but from memory seem to recall that the metamorphosis from the Phaethon tale is transferred to his sisters whose grief turns them into trees - weeping willows?

Roger wrote: "Kalliope wrote: "The beginning of Book II describing the 'artwork' of the doors of of the palace of the Sun, as made by Vulcan, is a beautiful ecphrastic section."

Roger wrote: "Kalliope wrote: "The beginning of Book II describing the 'artwork' of the doors of of the palace of the Sun, as made by Vulcan, is a beautiful ecphrastic section."Yes, that struck me too."

Yes! I love this idea, too, of paintings and other visual media of reception being a reverse ecphrasis - nice!

In Book Two, we have a series of unfortunate events that revolve around hubris and transformation; Phaethon's fall from Apollo's chariot brought the universe to it's knees'. As a demi-god, he's need for proof gave way for disaster. Apollo's descriptive travel route shows his concern of Phaethon's welfare; yet, he's not listening. Which shows during his flight, the horses are temperamental and each constellation is affected; so much, that even nature is reduced to ashes.

In Book Two, we have a series of unfortunate events that revolve around hubris and transformation; Phaethon's fall from Apollo's chariot brought the universe to it's knees'. As a demi-god, he's need for proof gave way for disaster. Apollo's descriptive travel route shows his concern of Phaethon's welfare; yet, he's not listening. Which shows during his flight, the horses are temperamental and each constellation is affected; so much, that even nature is reduced to ashes.Gaia's petition for salvation reaches Jupiter's ears, thus his verdict decreed a thunderbolt; after his death, the Heliades become poplar trees and best friend Cycnus a swan.

Water is opposite of fire, therefore these new forms represent grief.

As the chaos subsided, Callisto's transformation into a bear signifies Juno's need for revenge; yet, that lesson is flipped over into a new constellation. Forever placing her and Arcas into memory, innocent pawns of vengeance that gained honor despite being raped by Jupiter himself.

Then Coronis, Apollo's paramour, is in an illicit affair and Raven must report this sin to his master; along the way, he chats with Crow who states an ominous warning. Telling will cost your position and plumage; thus, Raven became a black bird. Aesculapius is raised by Chiron and his daughter, Ocyrhoe prophesized immortality; while, father will wish to relinquish immortality for death.

Her horse transformation is something the gods wish to silence because it challenges authority; Battus for greed and Aglauros for two-timing both Olympiads. Europa is entranced by the white bull and is whisked away; not knowing that she's riding on Jupiter.

Until then, see you at Book Three everyone!!

Callisto Paintings: heroic, and not so much

Callisto Paintings: heroic, and not so muchI might as well post the great Titian painting of Diana discovering Callisto's pregnancy, one of the seven "poesies," or scenes from Ovid, painted for Philip II of Spain. And with it, the Rubens version of the same subject, painted for Philip IV, around 80 years later. Both represent what might be called the "heroic" treatment of the subject—though cynics might think it is simply an excuse to paint female nudes.

Titian: Diana and Callisto (1556–59, Edinburgh NG)

Rubens: Diana and Callisto (c.1635, Madrd, Prado)

With the earlier episode of the story, Callisto's seduction by Jupiter, we are in a different ballpark. Rubens painted a version that, if not heroic (how could it be?), is certainly strong. François Boucher's 1759 painting has almost the strength of Rubens, but his other versions and those by other artists of the rococo era seem to aim instead for prettiness. The same cynics might say that Jupiter's change of gender gave perfect cover for erotic titillation of a rather different kind. R.

Rubens: Jupiter and Callisto (1615, Kassel)

Boucher: Jupiter and Callisto (1759, Kansas City)

Boucher: Jupiter and Callisto (1744, Moscow, Pushkin Mus.)

Boucher: Jupiter and Callisto (1763, New York Met)

Fragonard: Jupiter and Callisto (1755, Angers)

Angelica Kauffmann (attrib.): Jupiter and Callisto (late 18th century)

Book 2 in Met. Has similar structure to Book 1. The first long, tragic section is about a cosmological event—chaos threatens to return after all the work that was done to make the known universe tidy. The parallels to the modern world as the California fires burn is painfully apt as several others noted. There were also fires in Greece this summer. Jove finally relieves the drought at Earth’s urging. The line in which she says that she bears the burden of the plow is lovely.

Book 2 in Met. Has similar structure to Book 1. The first long, tragic section is about a cosmological event—chaos threatens to return after all the work that was done to make the known universe tidy. The parallels to the modern world as the California fires burn is painfully apt as several others noted. There were also fires in Greece this summer. Jove finally relieves the drought at Earth’s urging. The line in which she says that she bears the burden of the plow is lovely.Then several “romantic” stories are told including Calisto and Europa. Somehow the paintings made it easier to picture that if Jove was disguised as Diana, then it was a same sex romance. The Rubens is beautiful.

Europa heads into the ocean on the Jove/bull. Will there be more in Chapter 3? The notes in Raeburn translation point out a cliffhanger structure that leads from section to section.

Desirae wrote: "In Book Two, we have a series of unfortunate events that revolve around hubris and transformation; Phaethon's fall from Apollo's chariot brought the universe to it's knees'. As a demi-god, he's nee..."

Desirae wrote: "In Book Two, we have a series of unfortunate events that revolve around hubris and transformation; Phaethon's fall from Apollo's chariot brought the universe to it's knees'. As a demi-god, he's nee..."Oops Jupiter, not Jove in my previous post. I wish Ovid would settle on fewer names! Seriously, I agree with Desirae that hubris is a connecting theme. It accounts for the more minor tales of the crows and ravens too. They are so eager to be tattletales and know it alls that they get turned from white to black.

Roger wrote: "

Roger wrote: "If this is in Washington, I should know it, but I don't. It is truly magnificent,..."

I hope it is on display and you can watch it next time you are there, Roger. As I mentioned, it is not very large in spite of its theme and rendition.

It is a relatively 'recent' acquisition for the Museum.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archiv...

Roger wrote: "

Roger wrote: "I might as well post the great Titian painting of Diana discovering Callisto's pregnancy, one of the seven "poesies," or scenes from Ovid, painted for P..."

This is an excellent selection, Roger. There are so many paintings of Callisto, that I felt somewhat overwhelmed at trying to trace them...

I keep being perplexed by the way Ovid connects the various episodes... And now he leaves a 'cliffhanger', as Historygirl points out, at the end of Book II. The Europa story, one of the more popular ones in the whole work.

I keep being perplexed by the way Ovid connects the various episodes... And now he leaves a 'cliffhanger', as Historygirl points out, at the end of Book II. The Europa story, one of the more popular ones in the whole work.

On the sad episode of Apollo and Coronis...

On the sad episode of Apollo and Coronis...Johann Zoffany. 1759. Private Collection.

In this one Apollo has already slain her and full of regret is trying to bring her back to life by collecting some herbs (not a detail in Ovid)... The pyre to burn her is on the right, in the background.

Adam Elsheimer. 1607. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

I especially like the Elsheimer, and so early too! In my own selection, what I like about the Fragonard, despite the terminal insipidity of the figures, is the way the moon is made a part of the landscape, rather than just a hair ornament as in the others. R.

I especially like the Elsheimer, and so early too! In my own selection, what I like about the Fragonard, despite the terminal insipidity of the figures, is the way the moon is made a part of the landscape, rather than just a hair ornament as in the others. R.

Th’ astonisht youth, where-e’er his eyes cou’d turn,

Th’ astonisht youth, where-e’er his eyes cou’d turn,Beheld the universe around him burn:

The world was in a blaze; nor cou’d he bear

The sultry vapours and the scorching air,

Which from below, as from a furnace, flow’d;

And now the axle-tree beneath him glow’d:

Lost in the whirling clouds that round him broke,

And white with ashes, hov’ring in the smoke.

The corresponding place in the Bible:

Then the LORD rained upon Sodom and upon Gomorrah brimstone and fire from the LORD out of heaven;

And he overthrew those cities, and all the plain, and all the inhabitants of the cities, and that which grew upon the ground. Genesis 19:24-25

Both events are probably the references to the Minoan eruption of Thera, which was a major catastrophic volcanic eruption. Dated to the mid-second millennium BCE, the eruption was one of the largest volcanic events on Earth in recorded history.

The Phaethon disaster takes aetiology to a whole new level, accounting for a whole host of cosmic phenomena. The scorching of the chariot as it plunged earthward accounts for the Etiopians' blackened skin.The Nile hides its head from the flames, its source remaining a mystery for centuries to come. Phoebus parks what's left of his chariot for a day, thereby accounting for the darkness of a solar eclipse. The sight of Phaethon's fiery plunge to earth accounts for meteors that appear to fall but thereafter cannot be found. And finally, the tears of his sisters become amber droplets to adorn rich ladies.

The Phaethon disaster takes aetiology to a whole new level, accounting for a whole host of cosmic phenomena. The scorching of the chariot as it plunged earthward accounts for the Etiopians' blackened skin.The Nile hides its head from the flames, its source remaining a mystery for centuries to come. Phoebus parks what's left of his chariot for a day, thereby accounting for the darkness of a solar eclipse. The sight of Phaethon's fiery plunge to earth accounts for meteors that appear to fall but thereafter cannot be found. And finally, the tears of his sisters become amber droplets to adorn rich ladies.Such explanations are one of the features of all kinds of mythology that make it so appealing even to our modern selves, so blighted as we have become with the dismal realities of our day, where science offers a rational but unromantic analysis of everything. Let's face it: Ovid's account of the creation is a heck of a lot more fun than "the big bang" because it offers us a tangible scenario that we can imagine ourselves actually watching unfold.

Jim wrote: "...Let's face it: Ovid's account of the creation is a heck of a lot more fun than "the big bang"..."

Jim wrote: "...Let's face it: Ovid's account of the creation is a heck of a lot more fun than "the big bang"..."Although being a physicist I have to agree with you Jim. Maybe not the Big Bang, which still leaves some space for a divine initiator (as approved by the Catholic Church), but the movement of the moons, planets and stars have lost all their celestial magic since Newton.

Of all the tales included in the Met, surely Phaeton's wild ride is the most powerful, dramatic, earthshaking episode. It impacts not just one part of the world or a few mortals and gods; the entire earth, seas, sky and even the celestial stars are scorched! In her desperation, Earth pleads "Think of the universe!" Jove must put a stop to this catastrophe or else all of creation will be destroyed. This is one passage that Golding's fanciful, swinging verse cannot further illuminate. The Mandelbaum version says it all and we're swept away, along with Phaeton, clinging to that careening chariot!

Of all the tales included in the Met, surely Phaeton's wild ride is the most powerful, dramatic, earthshaking episode. It impacts not just one part of the world or a few mortals and gods; the entire earth, seas, sky and even the celestial stars are scorched! In her desperation, Earth pleads "Think of the universe!" Jove must put a stop to this catastrophe or else all of creation will be destroyed. This is one passage that Golding's fanciful, swinging verse cannot further illuminate. The Mandelbaum version says it all and we're swept away, along with Phaeton, clinging to that careening chariot!

Jim wrote: "Of all the tales included in the Met, surely Phaeton's wild ride is the most powerful, dramatic, earthshaking episode. It impacts not just one part of the world or a few mortals and gods; the entir..."

Jim wrote: "Of all the tales included in the Met, surely Phaeton's wild ride is the most powerful, dramatic, earthshaking episode. It impacts not just one part of the world or a few mortals and gods; the entir..."Agree, it is a passage that takes your breath away.

On the metamorphosis of Phaeton's sisters and Cycnus...

On the metamorphosis of Phaeton's sisters and Cycnus...Again, another print by

Hedrik Goltzius. 1590.

As we progress, I'm finding it a bit surprising that the "elephant in the room", namely sexual politics has not emerged as a major topic. I accept that we cannot logically or practically apply today's values and mores in judging a text written over 2 millennia ago. That said, the recurrent victimization of innocent young women by Jove for his own gratification, compounded by Juno's revenge upon the victims must raise concerns. I acknowledge my ignorance, not being a historian but do we have reason to believe that misanthropy readily condoned in 1st century C.E. Rome?

As we progress, I'm finding it a bit surprising that the "elephant in the room", namely sexual politics has not emerged as a major topic. I accept that we cannot logically or practically apply today's values and mores in judging a text written over 2 millennia ago. That said, the recurrent victimization of innocent young women by Jove for his own gratification, compounded by Juno's revenge upon the victims must raise concerns. I acknowledge my ignorance, not being a historian but do we have reason to believe that misanthropy readily condoned in 1st century C.E. Rome?

A number of us have commented on the Book 1 thread, Jim, about sexual politics, specifically issues of rape and the muting of female voices - it's certainly a fruitful framework through which we can read many of the episodes. I haven't read (re-read) Book 2 yet but am sure to have comments to add.

A number of us have commented on the Book 1 thread, Jim, about sexual politics, specifically issues of rape and the muting of female voices - it's certainly a fruitful framework through which we can read many of the episodes. I haven't read (re-read) Book 2 yet but am sure to have comments to add.

Jim wrote: "As we progress, I'm finding it a bit surprising that the "elephant in the room", namely sexual politics has not emerged as a major topic..."

Jim wrote: "As we progress, I'm finding it a bit surprising that the "elephant in the room", namely sexual politics has not emerged as a major topic..."As Roman Clodia says, Jim, there have been a number of comments. For example, a couple of messages before your last one in Book I, I wrote something very similar to what you said just now:

One of the things that I find fascinating in this discussion is the way that sexual politics keeps shifting. We tend to assume that the moral code which we have evolved can be applied retrospectively to previous eras. But these issues, too, need to be viewed in the context of their time (whether Ovid's or that of the 16th century painters and composers), which is a much more slippery matter.I also engaged on a long discussion a bit earlier with Roman Clodia and others about the morality of the Daphne episode, finally conceding that my more indulgent attitude was probably not justified. But I agree: this is something that I would expect to be taken up by many people, and probably to elicit many points of view.

As you may have gathered, my own interest in Ovid now focuses on the further metamorphoses of his stories in the hands of the post-Renaissance artists, poets, and musicians who have been the furniture of my professional life. And whatever the attitude towards female autonomy in first-century Rome, there is little doubt that most retellers of the stories in the 16th through 18th centuries took a more romantic view at odds with the modern morality of #MeToo. I cannot think of many offhand that did not treat the visitations of Jove as a bit naughty, perhaps, but still a privilege for the nymphs concerned.

Juno's punishments, on the other hand, are almost always treated as being cruel, vindictive, and entirely unfair. R.

Jim wrote: "The Mandelbaum version says it all ..."

Jim wrote: "The Mandelbaum version says it all ..."For those of us that are reading other translations, can you possibly quote a few lines of the Mandelbaum?

In recompense, I attach a few more from Ted Hughes, whose Tales from Ovid I have already quoted in message #12. What I like, that I don't find in any of the more formal verse translations that I have seen, is his willingness to abandon regularity of meter.*

Now Phaethon saw the whole world*Though I have just looked at the Rolfe Humphries, which I have on Kindle, and see that, even within a regular line-length, he manages a quite effective sense of disarray; he may well be even better:

Mapped with fire. He looked through flames

And he breathed flames.

Flame in, flame out, like a fire-eater.

As the chariot sparked white-hot

He cowered from the showering cinders.

His eyes streamed in the fire-smoke.

And in the boiling darkness

He no longer knew where he was

Or where he was going.

He hung on as he could and left everything

To the horses.

And Phaethon sees the earth on fire; he cannot

Endure this heat, the blast of some great furnace.

Under his feet he feels the chariot glowing

White-hot; he cannot bear the sparks, the ashes,

The soot, the smoke, the blindness. He is going

Somewhere, that much he knows, but where he is

He does not know. They have their way, the horses.

Roger wrote: "I also engaged on a long discussion a bit earlier with Roman Clodia and others about the morality of the Daphne episode,

Roger wrote: "I also engaged on a long discussion a bit earlier with Roman Clodia and others about the morality of the Daphne episode,..."

I also feel that applying our morals to previous ages is a double edge blade... I prefer to stay within the analytical approach and stay away from the morals. The latter can lead also to a desire to change or censor history, which for me can have very dangerous results.

In Ovid I am finding the humour and the politics, that RC pointed at, more fascinating.

The images of some of these beings being deprived of their speech (and like the Io episode managing to write her name - ´I´ in Italian- with her hoof, and therefore retaining her human abilities) are fascinating me - for they raise issues of (human) identity and artistic creativity.

On paintings on the Phaeton episode. I posted above the Rubens because I was familiar with it already, but I have now searched a bit and found some other very interesting images.

On paintings on the Phaeton episode. I posted above the Rubens because I was familiar with it already, but I have now searched a bit and found some other very interesting images.Poussin shows us the section before the fall, when Phaeton is kneeling in front of his father praying to let him use the chariot. He is rather strong, not the youth we/I imagine from the story who cannot hold the reins. Helios is sitting on a 'sunny arch'. On the left I can only see one white horse and the chariot can be glimpsed.

Nicolas Poussin. 1635. Berlin Gemäldegalerie.

Unsurprisingly, Anthony Van Dyck also depicted Phaeton's fall spectacularly. As a pupil of Rubens, this kind of subject would appeal to him. It is a much later painting. As said above Rubens while still in Italy and when young and still in Italy. I don't know whether VD had seen the one by his master.

Van Dyck's composition is simpler in the sense that he has singled out the four horses falling spectacularly, the loose chariot and the helpless Phaeton.

Van Dyck. 1635. Prado Museum.

Then also in Rubens's circle we have Jordaens treating the scene for a ceiling medallion - which has the extraordinary effect of us feeling how he is falling on top of us and that we will also be drawn into the disaster that he has caused. It belongs to a series on the Zodiac signs. He originally painted them for his own mansion in Antwerp, but are currently in Paris since 1802.

Jacob Jordaens. Falling Phaeton. 1641. Palais du Luxembourg, Paris.

And one more, that also looks to be on a ceiling:

Sebastiano Ricci. 1703. Museo Civico de Belluno.

And now we jump to the C19, with another likely painter to treat such a subject, Moreau.

Gustave Moreau. 1878. Louvre.

For anyone visiting Paris, I recommend to visit Moreau's house, now a Museum.

Thanks to everyone for your images.

Thanks to everyone for your images.Thanks especially, Kalliope, for those last ones

Phaeton's Fall is the perfect subject for a ceiling fresco.

How amazing it must be to stand beneath such a tumbling display.

Kalliope wrote: "I prefer to stay within the analytical approach and stay away from the morals...."

Kalliope wrote: "I prefer to stay within the analytical approach and stay away from the morals...."I know what you mean. As CS Lewis discussed in An Experiment in Criticism, it is a very limiting response to look at a work of art primarily in terms of our prior biases and experiences, and a very weak kind of art that encourages us to do so. We look to art to challenge, not to confirm.

On the other hand, it is quite possible to be objectively analytical in tracing the historical responses to a given theme. If we can demonstrate that a writer, painter, or composer of, say, the 17th century had a certain view of a subject, it is immaterial whether it matches our own, but quite legitimate to compare it with those of his processors, contemporaries, and successors. R.

Fionnuala wrote: "Phaeton's Fall is the perfect subject for a ceiling fresco.

Fionnuala wrote: "Phaeton's Fall is the perfect subject for a ceiling fresco.How amazing it must be to stand beneath such a tumbling display."

Yes, thanks, Kalli - some of those images are dizzying just looking at them 'flat', I can only imagine how vertiginous they are on a ceiling.

Hands up, I've never responded to the Phaethon episode as one of my favourites and in this case the visual images are more vivid for me than the text - very unusual!

Roger wrote: "I cannot think of many offhand that did not treat the visitations of Jove as a bit naughty, perhaps, but still a privilege for the nymphs concerned.."

Roger wrote: "I cannot think of many offhand that did not treat the visitations of Jove as a bit naughty, perhaps, but still a privilege for the nymphs concerned.."I wonder if that's because almost all the non-modern receptions we have of these rape/seduction episodes are by male writers/painters? Women authors in the C16th-17th centuries seem to be more attracted to Ovid's Heroides which enable female authorship.

Kalliope wrote: "I also feel that applying our morals to previous ages is a double edge blade... I prefer to stay within the analytical approach and stay away from the morals. The latter can lead also to a desire to change or censor history, which for me can have very dangerous results.."

Kalliope wrote: "I also feel that applying our morals to previous ages is a double edge blade... I prefer to stay within the analytical approach and stay away from the morals. The latter can lead also to a desire to change or censor history, which for me can have very dangerous results.."Yes, I agree, too, that we need to take texts on their own terms and not try to superimpose our own ideals/biases/prejudices. What we can do, though, is look at how the period itself judges an act - e.g. on the Book 1 thread #178 I mentioned that the rape of Lucretia gives us historicised evidence that rape was regarded as a serious event with politicised overtones.

Further to the above. I posted on Cavalli's opera La Calisto in comment #10, making the point that his Calisto, unlike Ovid's, delighted in her initiation. But it is more complex than that. Cavalli and Faustini, his librettist, have us sympathize with Calisto throughout, but give her a series of emotions:

Further to the above. I posted on Cavalli's opera La Calisto in comment #10, making the point that his Calisto, unlike Ovid's, delighted in her initiation. But it is more complex than that. Cavalli and Faustini, his librettist, have us sympathize with Calisto throughout, but give her a series of emotions:• rage against Jove for his scorching of the earthHow many of these occur in Ovid? Not the middle ones, because Jove reveals his manhood sooner. But what a marvelous roller-coaster of the emotions Cavalli provides! R.

• angry rejection of his sexual approaches when in his own form

• grateful pleasure when he woos her as Diana

• ebullient gratitude when she next sees the real Diana

• devastation when Diana throws her out

• touching trust when Juno draws her out

• speechlessness when Juno turns her into a bear

• radiant love when Jove sets her in the heavens

Roger wrote: "We look to art to challenge, not to confirm."

Roger wrote: "We look to art to challenge, not to confirm."Well said, Roger! And a very apposite epitaph for Ovid, I'd suggest.

Btw, happy Thanksgiving to all our US friends!

Roger wrote: "Further to the above. I posted on Cavalli's opera La Calisto in comment #10, making the point that his Calisto, unlike Ovid's, delighted in her initiation. But it is more complex than that."

Roger wrote: "Further to the above. I posted on Cavalli's opera La Calisto in comment #10, making the point that his Calisto, unlike Ovid's, delighted in her initiation. But it is more complex than that."This looks like a fascinating re-opening of Ovid, Roger, and some interesting gender play - I'm hoping to re-read Book 2 over the weekend so have lots to think about as I do.

Of your paintings, Kalliope, the hands-down winner for me is the Jordaens, largely because of the strength of his drawing of the foreshortened figure, and the trompe-l'oeuil effect of having him break through the actual ceiling. It may be the first Jordaens that did not have me comparing him unfavorably to his master.

Of your paintings, Kalliope, the hands-down winner for me is the Jordaens, largely because of the strength of his drawing of the foreshortened figure, and the trompe-l'oeuil effect of having him break through the actual ceiling. It may be the first Jordaens that did not have me comparing him unfavorably to his master.On the other hand, while Moreau is an interesting figure, I have never really liked any of his paintings, finding them too complex to make out exactly what is going on, and far too overperfumed. R.

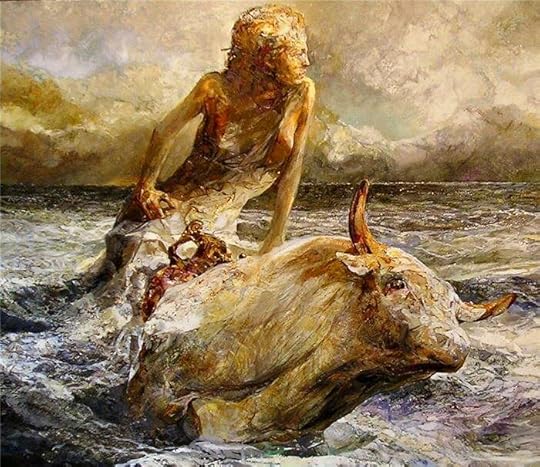

I believe Kalliope will be posting some pictures of Europa—and there are so many to choose from! But she probably won't choose this, which I found on the web. No information whatever, except the name of the artist, Sergey Petrov Vasil Ustyuzhanin, and even that may not be accurate,

I believe Kalliope will be posting some pictures of Europa—and there are so many to choose from! But she probably won't choose this, which I found on the web. No information whatever, except the name of the artist, Sergey Petrov Vasil Ustyuzhanin, and even that may not be accurate,

What I like about it, apart from the energy of the painting of the bull and the waves, is the figure of Europa herself. Unlike almost any of the more famous versions, she does not look either enamored, thrilled, or terrified. In fact, it is impossible to tell just what she is feeling. And given our current discussion about the morality of Ovid (or rather, the moralities we read into Ovid), I find this ambiguity stimulating. R.

Books mentioned in this topic

Le bain de Diane (other topics)After Ovid: New Metamorphoses (other topics)

The Penelopiad (other topics)

Metamorphica (other topics)

The Penelopiad (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Pierre Klossowski (other topics)Euripides (other topics)