Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses discussion

This topic is about

Metamorphoses

The Metamorphoses - The 15 Books

>

Book Twelve - 10 August, 2019

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Kalliope

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Sep 22, 2018 06:34AM

Discussion of Twelfth Book.

Discussion of Twelfth Book.

reply

|

flag

To whet our appetite for Book 12 which we're starting to discuss this weekend, here's a link to a mouthwatering exhibition on Troy at the British Museum this autumn: https://www.britishmuseum.org/whats_o...

To whet our appetite for Book 12 which we're starting to discuss this weekend, here's a link to a mouthwatering exhibition on Troy at the British Museum this autumn: https://www.britishmuseum.org/whats_o...

how I wish I could see the exhibition, beautiful website, thank you! -- "But this isn’t a straightforward tale of right and wrong. Its heroes – and none more so than the great Achilles – are complex, with heroic strength but human weaknesses and in the end it is unclear who, if anyone, really wins."

how I wish I could see the exhibition, beautiful website, thank you! -- "But this isn’t a straightforward tale of right and wrong. Its heroes – and none more so than the great Achilles – are complex, with heroic strength but human weaknesses and in the end it is unclear who, if anyone, really wins."

Elena wrote: "how I wish I could see the exhibition"

Elena wrote: "how I wish I could see the exhibition"I'll definitely be going and will happily report back.

Some BM exhibitions can be disappointing since they simply move objects from other rooms to create a show but with this one, over 70% of the exhibits are coming from other museums (according to a colleague of mine who used to work at the BM and still has friends there).

So, to Book 12... the quandary Ovid must have faced is how to retell a story that is already told in one of the foundational texts of classical literature, and which has been extensively mined in Greek drama.

So, to Book 12... the quandary Ovid must have faced is how to retell a story that is already told in one of the foundational texts of classical literature, and which has been extensively mined in Greek drama. It seems to me that there's always a self-conscious sense of belatedness in this book - plus there's the spectre of Virgil's Aeneid, contemporary with Ovid and already hailed as *the* Latin epic.

'The Greeks at Aulis' made me smile when Aulis is bathetically described as 'famous for fish' - when in literary terms it's famous for the sacrifice of Iphigenia (e.g. Euripides' Iphigenia at Aulis).

I also couldn't help noting the numerous instances of the word 'wrath' or 'rage' - a pointed intertext with the opening line of the Iliad.

And Ovid cleverly encompasses the two versions of the Iphigenia story - one where she dies, the other where she is spirited away by Athena e.g. Euripides' Iphigenia in Tauris - by using the formula 'the story goes'.

The section on Rumour (fama in Latin, rumour but also reputation, fame, and therefore the thing for which poets strive) is a well-recognised set piece, and prompts Chaucer's The House of Fame.

The section on Rumour (fama in Latin, rumour but also reputation, fame, and therefore the thing for which poets strive) is a well-recognised set piece, and prompts Chaucer's The House of Fame. I especially like the section where the crowd 'pass on stories to others; the fiction grows and detail is added by each new teller' (12.56-7) - a self-conscious acknowledgement of how literature and intertextuality works.

For a thoroughly 21st century take on the Iphigenia story, I would refer to The Songs of the Kings by Barry Unsworth.

For a thoroughly 21st century take on the Iphigenia story, I would refer to The Songs of the Kings by Barry Unsworth.

Reading Ovid's version of the Iphigenia tale brought to mind the Canadian Opera Compay's production a few years back of Gluck's opera. It could only be described as stark, the stage totally black. With the arrival of Orestes on stage, that production in turn harkened back to the even more memorable COC production of Elektra, that featured a brutally compressed stage, the confined space emphasizing the air of oppression and desperation.

Reading Ovid's version of the Iphigenia tale brought to mind the Canadian Opera Compay's production a few years back of Gluck's opera. It could only be described as stark, the stage totally black. With the arrival of Orestes on stage, that production in turn harkened back to the even more memorable COC production of Elektra, that featured a brutally compressed stage, the confined space emphasizing the air of oppression and desperation.With some regret, I don't think Ovid comes close to re-creating the intensity of Euripides' version of the story.

corpus deus aequoris albam contulit in volucrem, cuius modo nomen habebat (XII, 144-145)

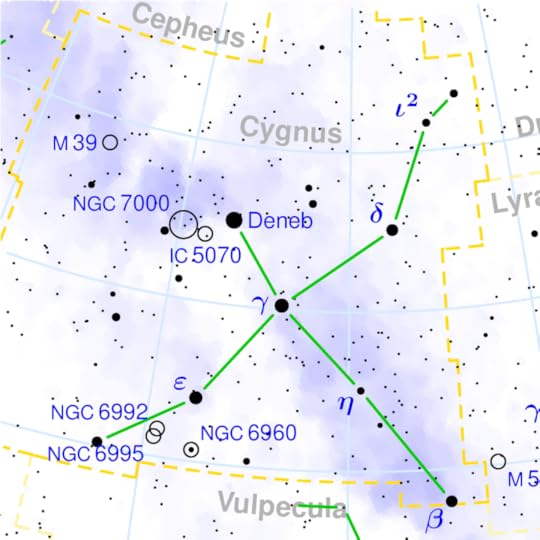

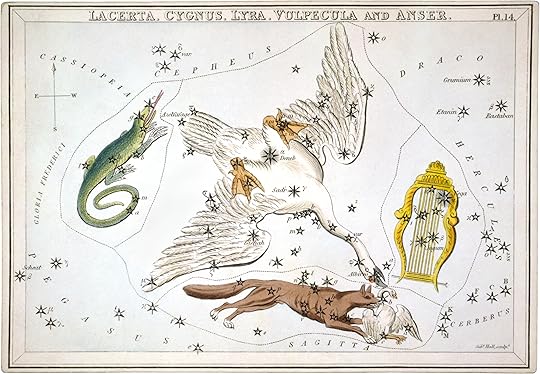

corpus deus aequoris albam contulit in volucrem, cuius modo nomen habebat (XII, 144-145)Cygnus in fact is both the scientific name for swans as well as the name of a star constellation. The latter is one of my favourites. Its stars clearly mark the form of a swan with an extended neck flying on the background of the Milky Way.

In Book Twelve, war is an unavoidable action with no resolution; gods and heroes alike are fighting for supremacy. A conflict that will not be won without a: sword, shield, and the divine favor of Olympus.

In Book Twelve, war is an unavoidable action with no resolution; gods and heroes alike are fighting for supremacy. A conflict that will not be won without a: sword, shield, and the divine favor of Olympus.King Priam mourns for his half-son Aesacus upon Trojan soil, the funeral rights are performed in a private ceremony. All paid their respects, except the firebrand Paris; under Aphrodite’s favor, he abducted Helen.

Enraged, King Menelaus launched over one thousand ships to pursue the wily prince toward Troy. As they reach Aulis, a “divine” storm blocked their way while soldiers prayed for a solution. First, the prophet Calchas eluded Achaean (Greek) triumph paid in nine years of bloodshed; symbolized by the hungry snake, it will ensue with toil.

Second, is the sacrifice of young princess Iphigenia to appease Artemis’s wrath. Mycenaean king Agamemnon knows that every conflict has its infinite number of casualties; the slaughter of an “untainted” life will bring salvation. Moved by his actions, the goddess metamorphosized Iphigenia into a doe; while in heaven, immortals fight amongst themselves.

They take sides to support their “pious” allies and cannot be held accountable. Why? Immense power is subjected to fate; their actions determine Troy’s destruction. But for Rumor, it’s a display of power; her brass palace has relayed information, to its citizens, about an Achaean army ready to sack the city.

Alarmed of such news, its military gathered arms in defense of their homeland; with Protesilias as the first causality in war. Warrior’s on both sides must kill in order to gain recognition; Trojans and Achaeans alike, cannot win glory without proving themselves. But for Achilles, he aims to become the mightiest warrior in history.

His hubris took root during a skirmish with Cycnus; second to Hector, this solider has slaughtered over one thousand Achaeans. Achilles’s “blessed” Pelion spear rebounded upon Cycnus’s flesh; the “son” of Poseidon cannot die easily.

That fact triggered the hero’s murderous intent; from arrows to swords, Achilles pushed past his limit. Caught off guard, the Trojan warrior was strangled to death; Cycnus’s swan transformation became “his” salivation.

Such a memorable battle must be celebrated; opposing sides held a truce to gather their departed comrades on the field. To commemorate Achilles’s victory, sacrifice was offered to Athena, while their general’s recount past exploits; everyone pondered about what made the hero’s “quarry” seem imperious to weapons.

Nestor revealed that these “invincible” men were once commonplace; none as famous as the heroine Caenis. Born a woman, her beauty held into high esteem that it caught the eye of Poseidon; Caenis prayed for masculinity as a way to safeguard her own violation.

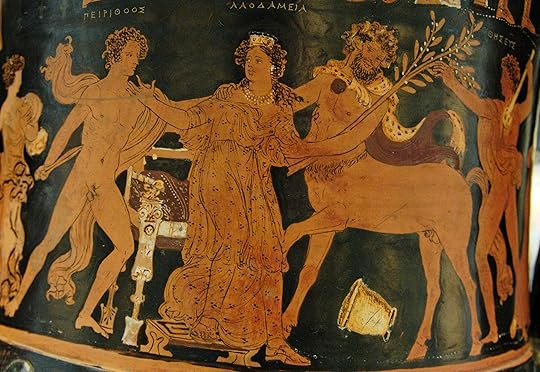

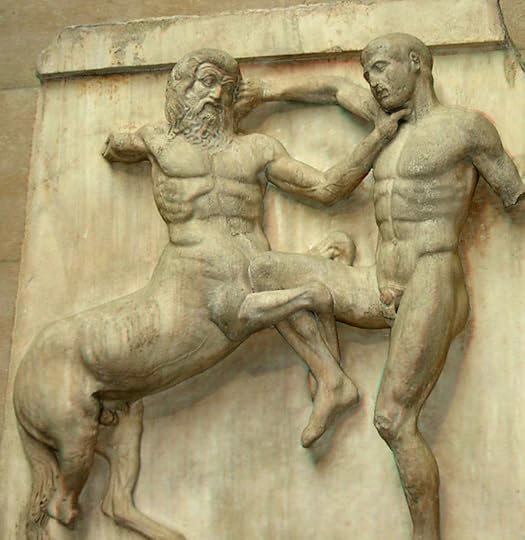

As “his” fame grew, a wedding will set the stage towards a new beginning; king Ixion’s son Pirithous and princess Hippodamia invite mortals and centaurs in the celebration. Two races are united to witness the harmonious union; until, wine-induced Eurytus tried to claim Hippodamia.

Theseus, in response, grasped a wine bowl and hurled it to the assailant’s head; a joyous event turned into a brawl, a retinue of hero’s and centaurs battled for supremacy. Even innocent bystanders were slain in attendance, including the centaurian couple Cyllarus and Hylonome; each warrior has killed a centaur to display their courage, but “Caeneus” has slaughtered five.

“His” divine invincibility has placed their enemies on edge; the centaurians worked together to crush their foe underground. From trees to boulders, “Caeneus” was boxed in with no chance of escape; transformed as a bird, that audacity lives on.

Tlepolemus, son of Heracles, did not hear Nestor’s homage to his “divine” father. His refusal to mention Heracles stems from hatred; as ruler of Pylos, all twelve of Nestor’s brothers were killed during battle. In open combat, Heracles is an unstoppable force; yet, brother Periclymenus is a shape shifter.

In eagle form, he took flight and attacked the hero in swift succession; while hovering overhead, Heracles pulled back his Hydra quiver and released an arrow aimed at the young prince.

Ten years passed, Poseidon’s grief for Cycnus was not forgotten upon the plains of Troy; Achilles’s brutality has fired the flames of vengeance upon both realms. Hector’s body is dragged across the battlefield behind the victor’s chariot, while its walls are reduced to nothing but ash. The gods give him glory and has abused their power with no recognition; such arrogance cannot be ignored.

Conversing with Apollo, he guided firebrand Paris’s arrow to silence Achilles’ triumph; his wish for fame came true after dying upon foreign soil. As the funeral pyre burned away his body, what remained is Vulcan’s “divine armor.” A prize that all Achaean warriors and kings will debate amongst themselves…

Until then, see you in Book Thirteen everyone!!!

Sorry all, but I still have a lot of trouble with Ovid's work. In this book for instance, there is a rather straightforward summary of the Trojan war's beginning and development. But then, it seems that more than half the book was involved with a very, very brutal slaughter of centaurs.

Sorry all, but I still have a lot of trouble with Ovid's work. In this book for instance, there is a rather straightforward summary of the Trojan war's beginning and development. But then, it seems that more than half the book was involved with a very, very brutal slaughter of centaurs. It seems as Ovid not only again wanted to run out at least two dozen proper nouns (to show he knows their names?), but also wanted to outdo himself in the graphic descriptions of the manner of each of the deaths - one through the eye, another through the throat - you get the idea. He even apologizes at one point that he only has the names of five of those killed, but cannot tell us the specific manner in which they died. What gives?

RC has commented previously that we shouldn't judge the classics by our modern standards of literature, and I agree. But still, why the (to my relatively unintiated non-classical mind) the largely unnecessary digression? And why the excessive blood and seemingly endless fascination with death? And while I'm at it, why the insatiable lust of the gods and willingness to rape at will?

I'd really appreciate anyone's explanation for these aspects which make Ovid both uncomfortable for me to read and difficult for me to get the point of it all.

Steve wrote: "But still, why the (to my relatively unintiated non-classical mind) the largely unnecessary digression? And why the excessive blood and seemingly endless fascination with death? And while I'm at it, why the insatiable lust of the gods and willingness to rape at will?"

Steve wrote: "But still, why the (to my relatively unintiated non-classical mind) the largely unnecessary digression? And why the excessive blood and seemingly endless fascination with death? And while I'm at it, why the insatiable lust of the gods and willingness to rape at will?"Interesting questions, Steve, and of course there's no definitive answer, just our own individual takes on the text. For me, it's all about the literary and cultural contexts in which Ovid is writing.

The story of Troy is so foundational that it's difficult to find a novel way of approaching it. Ovid's is to treat it obliquely. So the 'digression' of the battle of the Lapiths and centaurs is a stand-in for the Trojan war. The excessive blood is drawing attention to the basic facts of war (Ovid comes from a generation that grew up just after the bloody civil wars that wrenched Rome apart).

The explicit wounds draw on both Homer and Virgil - and there are many instances of soldiers in the Aeneid being wounded or killed by being speared or stabbed through the mouth or throat - scholars have read this as a comment on the silencing of certain viewpoints. The episode of the married couple who die together is a riff on the Nisus and Euryalus episode in the Aeneid.

It's also the case that the battle of the Lapiths and centaurs is depicted on the Parthenon frieze: the Athenians used it as one of the series of images which showed the clash between the 'civilised' and 'uncivilised' (or self and other). Ovid, writing about 400 years later shows both sides as blood-thirsty.

As for the many (many) rapes, it's pretty well recognised now that rape can be a metaphor for asymmetrical power, whether patriarchal or other. Rome is built on myths of rape: the mother of Romulus and Remus, the mythical founders of Rome, was raped by Mars so that Rome itself is the outcome of rape.

The republic is ushered in by the rape of Lucrece where the tyranny of monarchy is figured through this abuse by Tarquin - it's after this expulsion of the kings that the republican Senate is set up. Even after the republic becomes, in effect, a hereditary monarchy under Augustus, the mythology of the senate-led republic is kept up. Rome's self-identity is founded on these mythic rapes ('over her dead body').

The story of Caenis in Book 12 is also instructive in understanding how rape and gender are connected in the Roman mind: Caenis is raped by Neptune and when he apologises and offers her a wish to compensate, she says she never wants to be raped again - and so she is turned into a man. Her body, being male, is literally impenetrable hence why s/he cannot be pierced by arrows, spears or swords. The implication is that 'real' masculinity ('vir' in Latin) is physically uncompromised - boys/adolescents can be raped, but not 'real' men. Rape is both a biological destiny in Roman thought and a metaphor for power inequalities.

I think Ovid *is* uncomfortable for us to read and, perhaps, intentionally so. There certainly have been feminist debates from the 1980s about whether the Met should be taught on undergraduate curricula not just because of the number of rapes but because some readers regard them as textually gleeful. It would be interesting to see whether we agree or disagree with that verdict.

Like Steve I struggled reading through the gory description of the fight between the centaurs and the Lapiths. Could it be that Ovid included such scenes to entertain those parts of the public that in our time endulge in Action movies or Computer Games? Looking at some of the wall paintings in medieval churches one can find very explicit scenes of torturing saints. So there must be some fascination of bloodshed in us. With regard to rape, I wonder whether the sexual relations in arranged marriages or between master and slave would not count as rape in our times. So maybe the distance / disgust was much lower in times of Ovid.

Like Steve I struggled reading through the gory description of the fight between the centaurs and the Lapiths. Could it be that Ovid included such scenes to entertain those parts of the public that in our time endulge in Action movies or Computer Games? Looking at some of the wall paintings in medieval churches one can find very explicit scenes of torturing saints. So there must be some fascination of bloodshed in us. With regard to rape, I wonder whether the sexual relations in arranged marriages or between master and slave would not count as rape in our times. So maybe the distance / disgust was much lower in times of Ovid.

The conflict of the wedding is a prelude to Troy's destruction; Nestor's recount was a battle between civil and natural order. As the new Lapith king, he married Hippodamia to justify a new age; yet, the centaur's are "invited" to witness it's change within an open ceremony. Unlike Chiron, they are wild and are not accustomed to "worldly" ideals; therefore, one incident led to a massacre. To the point, that even women took up arms in defense; “Caeneus” was targeted because her invincibility was overpowering authority.

The conflict of the wedding is a prelude to Troy's destruction; Nestor's recount was a battle between civil and natural order. As the new Lapith king, he married Hippodamia to justify a new age; yet, the centaur's are "invited" to witness it's change within an open ceremony. Unlike Chiron, they are wild and are not accustomed to "worldly" ideals; therefore, one incident led to a massacre. To the point, that even women took up arms in defense; “Caeneus” was targeted because her invincibility was overpowering authority. Which also led to Troy, Paris's need for love overshadowed reason; that mistake cost an entire civilization to annihilation. Cycnus died for a cause that entails nothing; Achilles's ruthless ambition blinded his own humanity. Even the gods are fighting amongst each other to prove a point. War is the catalyst of unresolved disputes; if left unchecked, nothing will stop it.

Desirae wrote: "The conflict of the wedding is a prelude to Troy's destruction; Nestor's recount was a battle between civil and natural order. ..."

Desirae wrote: "The conflict of the wedding is a prelude to Troy's destruction; Nestor's recount was a battle between civil and natural order. ..."Thank you so much for this explanation and analysis, Desirae. I understood only through further reading that Hippodeimea is identical with Briseis, the woman about whom Achilles and Agamemnon almost fell apart. So there is a clear link to the Troian war.

Perithoos Hippodameia Vase. 350-340 AD. British Museum

Fight between a Centaur and a Lapith, Partenon.

I suppose it's impossible for us in the 21st century to fully relate to the world of 1st century Rome and that society's view of its own legends, as they were largely inherited from an even earlier civilization. That said, I wonder if the point of Ovid's lengthy and gory account of the wedding day massacre is that the entire blood bath accomplished absolutely nothing. It does appear to be a prelude to the Trojan War. Which also raises the question of the futility of war in general.

I suppose it's impossible for us in the 21st century to fully relate to the world of 1st century Rome and that society's view of its own legends, as they were largely inherited from an even earlier civilization. That said, I wonder if the point of Ovid's lengthy and gory account of the wedding day massacre is that the entire blood bath accomplished absolutely nothing. It does appear to be a prelude to the Trojan War. Which also raises the question of the futility of war in general.

I'm also stuck by the fact that both of the two great heroes, Achilles and (looking ahead into Book XIII) Ajax die in far from glorious ways, Achilles by subterfuge at the hands of decidedly un-heroic Paris and Ajax by suicide after losing a battle of words with the sly Ulysses.

I'm also stuck by the fact that both of the two great heroes, Achilles and (looking ahead into Book XIII) Ajax die in far from glorious ways, Achilles by subterfuge at the hands of decidedly un-heroic Paris and Ajax by suicide after losing a battle of words with the sly Ulysses.Is Ovid suggesting that the age of heroes has passed? I mention this in view of the fact that Ovid himself fell victim to palace politics. I wonder how sincere were his praises of the Augustian regime.

I'm reminded of other artists who, when having to survive oppressive regimes, craftily embedded subversive ideas into their works while ostensibly toeing the party line.

Thanks, all! I really appreciate your efforts to make the bloodbath involving the centaurs at least partially intelligible.

Thanks, all! I really appreciate your efforts to make the bloodbath involving the centaurs at least partially intelligible. From RC's idea that it presented a novel way to tell a well-told tale (Troy) through Peter's analysis of the 'heart of darkness' in all of us which surfaces in action movies and video games and Desirae's thoughtful elucidation of the way in Paris, Cygnus, Achilles and even the Gods seem to be driven by largely irrational impulses to essentially meaningless ends, I came to understand this troubling Book much better.

But then Jim's analysis of the futility of war and the possible subterfuge of Ovid's veiled criticism of the age of heroes and potentially, of Augustus himself was truly an amazing leap of possible interpretation. Could the bombast of violence and surfeit of blood be a sardonic and sarcastic comment on the rapacious vainglory he felt underpinned the Empire from which he'd been so unceremoniously cast?

This book is of war and warriors. One strangled warrior was turned into a swan and one raped maiden was turned into male warrior… The incessant descriptions of battles are too monotonous and tedious and even the death of Achilles seems to be unimpressive:

This book is of war and warriors. One strangled warrior was turned into a swan and one raped maiden was turned into male warrior… The incessant descriptions of battles are too monotonous and tedious and even the death of Achilles seems to be unimpressive:“Of all the mighty man, the small remains

A little urn, and scarcely fill’d, contains.”

There is an excellent novel Ransom by David Malouf that is based on a small episode of Trojan War.

So we have the most grotesque scene in the battle of the brutish Centaurs interrupted in line 415 with the charming love story of two beautiful Centaurs Cyllarus and Hylonome. The description of the pretty girl Centaur grooming her mane with flowers to attract the handsome boy Centaur is straight out of a Walt Disney cartoon...OK Ovid just what are you up to?

So we have the most grotesque scene in the battle of the brutish Centaurs interrupted in line 415 with the charming love story of two beautiful Centaurs Cyllarus and Hylonome. The description of the pretty girl Centaur grooming her mane with flowers to attract the handsome boy Centaur is straight out of a Walt Disney cartoon...OK Ovid just what are you up to?

Haha, Elena, I read the centaur love story as a riff on Virgil's Nisus and Euryalus episode in book 9 of the Aeneid (worth a google if you're not familiar with it): another pair of lovers who die together in battle. The younger is described as beautiful and in death Virgil uses the simile of a poppy cut down by a plough (which is itself an allusion to both Homer and Sappho, and was reused by Catullus) - so a whole nexus of echoes and intertexts, as usual, in Ovid.

Haha, Elena, I read the centaur love story as a riff on Virgil's Nisus and Euryalus episode in book 9 of the Aeneid (worth a google if you're not familiar with it): another pair of lovers who die together in battle. The younger is described as beautiful and in death Virgil uses the simile of a poppy cut down by a plough (which is itself an allusion to both Homer and Sappho, and was reused by Catullus) - so a whole nexus of echoes and intertexts, as usual, in Ovid.

i.e. Disney romance interrupts a slasher drama interrupts a sword-and-sandal epic?!?! (respectively, a centaur love story, the slaughter of centaurs by Lapiths and the Trojan war) I honestly don't think Ovid had an outline on hand when he took up his stylus, and rather just followed wherever his peripatetic muse took him.

i.e. Disney romance interrupts a slasher drama interrupts a sword-and-sandal epic?!?! (respectively, a centaur love story, the slaughter of centaurs by Lapiths and the Trojan war) I honestly don't think Ovid had an outline on hand when he took up his stylus, and rather just followed wherever his peripatetic muse took him.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Haha, Elena, I read the centaur love story as a riff on Virgil's Nisus and Euryalus episode in book 9 of the Aeneid (worth a google if you're not familiar with it): another pair of lovers who die t..." This is so helpful, all these echoes and references must reflect a well-read audience.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Haha, Elena, I read the centaur love story as a riff on Virgil's Nisus and Euryalus episode in book 9 of the Aeneid (worth a google if you're not familiar with it): another pair of lovers who die t..." This is so helpful, all these echoes and references must reflect a well-read audience.

Steve wrote: "i.e. Disney romance interrupts a slasher drama interrupts a sword-and-sandal epic?!?! (respectively, a centaur love story, the slaughter of centaurs by Lapiths and the Trojan war) I honestly don't ..." I'm trying to visualize the transmission of these stories that seem to get swept up into vast anthologies as epics. The Odyssey is an anthology of travelers' tales united by the hero's wanderings, in some ways the Old Testament is an anthology, and certianly the Arabian Nights. It seems the Greeks had short texts with sentimental stories of love that end in the transformation. Bibliophiles collected short texts into anthologies and then arranged them to indirectly comment on each other. Greek and later Latin and Arabic authors took the next step and strung the stories together with transitions and interconnections, and then embedded one story into another...with transitions from one papyrus scroll to the next. Something like that seems to explain the complex structure we are encountering. Book 12 with its the Russian doll structure has me reeling...

Steve wrote: "i.e. Disney romance interrupts a slasher drama interrupts a sword-and-sandal epic?!?! (respectively, a centaur love story, the slaughter of centaurs by Lapiths and the Trojan war) I honestly don't ..." I'm trying to visualize the transmission of these stories that seem to get swept up into vast anthologies as epics. The Odyssey is an anthology of travelers' tales united by the hero's wanderings, in some ways the Old Testament is an anthology, and certianly the Arabian Nights. It seems the Greeks had short texts with sentimental stories of love that end in the transformation. Bibliophiles collected short texts into anthologies and then arranged them to indirectly comment on each other. Greek and later Latin and Arabic authors took the next step and strung the stories together with transitions and interconnections, and then embedded one story into another...with transitions from one papyrus scroll to the next. Something like that seems to explain the complex structure we are encountering. Book 12 with its the Russian doll structure has me reeling...

Elena wrote: "Steve wrote: "i.e. Disney romance interrupts a slasher drama interrupts a sword-and-sandal epic?!?! (respectively, a centaur love story, the slaughter of centaurs by Lapiths and the Trojan war) I h..."

Elena wrote: "Steve wrote: "i.e. Disney romance interrupts a slasher drama interrupts a sword-and-sandal epic?!?! (respectively, a centaur love story, the slaughter of centaurs by Lapiths and the Trojan war) I h..."Wow! I love Elena's Russian Doll analogy! As we've seen so many times in the Met (most notably in the Arachne tale) there are sories-within-legends-within-anecdotes ....

And each re-telling opens up possible new interpretations.

That's why so many people (myself included) have been lured to these stories through opera, which frees up librettists, composers, producers and all the rest to conceive of new interpretations and run with them!

Jim wrote: "And each re-telling opens up possible new interpretations."

Jim wrote: "And each re-telling opens up possible new interpretations."Exactly, Jim - that, I'd say, is one of the things Ovid is drawing attention to, the openness of stories that can be re-told, re-interpreted, subverted, expanded, contracted... stories themselves can be, and are, metamorphosed.

Do we want to move onto Book 13? Off the top of my head, it doesn't completely move away from the Trojan War.

Do we want to move onto Book 13? Off the top of my head, it doesn't completely move away from the Trojan War.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Do we want to move onto Book 13? Off the top of my head, it doesn't completely move away from the Trojan War." Yes, I'd like to go on to Book 13, or treat 12 and 13 together. The Trojan War story must have been Ovid's chance to compete with both Homer and Virgil. I don't know Virgil at all except from the Broch's German "Tod des Vergil," which emphasized Virgil's desire to have the uncompleted Aeneid destroyed

Roman Clodia wrote: "Do we want to move onto Book 13? Off the top of my head, it doesn't completely move away from the Trojan War." Yes, I'd like to go on to Book 13, or treat 12 and 13 together. The Trojan War story must have been Ovid's chance to compete with both Homer and Virgil. I don't know Virgil at all except from the Broch's German "Tod des Vergil," which emphasized Virgil's desire to have the uncompleted Aeneid destroyed

That might have been an apocryphal story, Elena (about Virgil wanting the Aeneid) to be burnt) though it's one which grips the imagination.

That might have been an apocryphal story, Elena (about Virgil wanting the Aeneid) to be burnt) though it's one which grips the imagination.

Roman Clodia wrote: "To whet our appetite for Book 12 which we're starting to discuss this weekend, here's a link to a mouthwatering exhibition on Troy at the British Museum this autumn: https://www.britishmuseum.org/w..."

Roman Clodia wrote: "To whet our appetite for Book 12 which we're starting to discuss this weekend, here's a link to a mouthwatering exhibition on Troy at the British Museum this autumn: https://www.britishmuseum.org/w..."Oh, my... I would love to go...

I have just read in Book 12 until the death of Cycnus... which, when he first appeared confused me since we've met a couple of Cycnuses before - Book 2 and 7, I believe.

I have just read in Book 12 until the death of Cycnus... which, when he first appeared confused me since we've met a couple of Cycnuses before - Book 2 and 7, I believe.I have not found a good, or specific image to Cycnus and Achilles.

Roman Clodia wrote: "So, to Book 12... the quandary Ovid must have faced is how to retell a story that is already told in one of the foundational texts of classical literature, and which has been extensively mined in G..."

Roman Clodia wrote: "So, to Book 12... the quandary Ovid must have faced is how to retell a story that is already told in one of the foundational texts of classical literature, and which has been extensively mined in G..."The notes in my edition trace the various sources from which Ovid created his own version of the Iliad. They mention the 'Cypria' - a poem in the no longer surviving collection known as the Epic Cycle (how do the academics know this?)

The version of Iphigena being saved at the last minute seems to be the version in Cypria. While in Aeschylus Agamemnon and in de Rerum Natura she is killed.

Very confusing.

I must say that even though it will be very interesting to see how Ovid changes Homer, and later Virgil, I preferred the work until now - with the gods. May be because I am more familiar with the stories we are dealing now.

I must say that even though it will be very interesting to see how Ovid changes Homer, and later Virgil, I preferred the work until now - with the gods. May be because I am more familiar with the stories we are dealing now.

Jim wrote: "Reading Ovid's version of the Iphigenia tale brought to mind the Canadian Opera Compay's production a few years back of Gluck's opera. It could only be described as stark, the stage totally black. ..."

Jim wrote: "Reading Ovid's version of the Iphigenia tale brought to mind the Canadian Opera Compay's production a few years back of Gluck's opera. It could only be described as stark, the stage totally black. ..."Those must have been wonderful operas to watch, Jim.

I'm enjoying no end reading Third book It's the work of art in itselg ,and the BOOK 2 , the Narciss part and Cadmus

On the structure - again from my notes - Ovid's Iliad accounts a bit more than a 10% of the entire boo, while his Aeneid for 8 % - so a total of 18% dedicated to the 'imitation' of 'two earlier epics with which the Metamorphose has virtually nothing in common except length and the dactylic hexameter'.

On the structure - again from my notes - Ovid's Iliad accounts a bit more than a 10% of the entire boo, while his Aeneid for 8 % - so a total of 18% dedicated to the 'imitation' of 'two earlier epics with which the Metamorphose has virtually nothing in common except length and the dactylic hexameter'.So, as I said above, I hope that this 'imitative' section offers an added dimension. It seems it is humour and parody. The fight with the third swan of the book - presented as joke on the heroic?.. it seems that strangling is not heroic.

My favourite part in this early section of the book is the description of 'Rumour'.

My favourite part in this early section of the book is the description of 'Rumour'.I loved this - with Gullibility, Error, baseless Joy, frantic Fears, fresh Faction and Whispers...

Johann Wilhelm Baur. 1709.

Elena wrote: "Steve wrote: "i.e. Disney romance interrupts a slasher drama interrupts a sword-and-sandal epic?!?! (respectively, a centaur love story, the slaughter of centaurs by Lapiths and the Trojan war) I h..."

Elena wrote: "Steve wrote: "i.e. Disney romance interrupts a slasher drama interrupts a sword-and-sandal epic?!?! (respectively, a centaur love story, the slaughter of centaurs by Lapiths and the Trojan war) I h..."Yes, the structure and the transitions for me has been the most fascinating and challenging part of the read. That's why I had to work on a kind of Index for myself, which got more and more complicated. I have stopped but plan to reread this and continue what I had been doing, but now that I am trying to catch up with you all, I just cannot do that at the moment.

But it is the most baffling element for me.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Haha, Elena, I read the centaur love story as a riff on Virgil's Nisus and Euryalus episode in book 9 of the Aeneid (worth a google if you're not familiar with it): another pair of lovers who die t..."

Roman Clodia wrote: "Haha, Elena, I read the centaur love story as a riff on Virgil's Nisus and Euryalus episode in book 9 of the Aeneid (worth a google if you're not familiar with it): another pair of lovers who die t..."I have not read the Aeneid.. May be a plan for 2020.

Kalliope wrote: "Roman Clodia wrote: "So, to Book 12... the quandary Ovid must have faced is how to retell a story that is already told in one of the foundational texts of classical literature, and which has been e..."

Kalliope wrote: "Roman Clodia wrote: "So, to Book 12... the quandary Ovid must have faced is how to retell a story that is already told in one of the foundational texts of classical literature, and which has been e..."For Gluck, knowing his (French) audience, it just wouldn't do for Iphigenia not to be rescued. Like Ovid himself, Gluck understood that stories are elusive entities that once sent off into the world are likely to evolve, change their appearance, collect new meanings, worm their way into unforeseen environments. Metamorphosis never ends ....

Jim wrote: "For a thoroughly 21st century take on the Iphigenia story, I would refer to The Songs of the Kings by Barry Unsworth."

Jim wrote: "For a thoroughly 21st century take on the Iphigenia story, I would refer to The Songs of the Kings by Barry Unsworth."Thank you for this, Jim. I will keep it in mind.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Steve wrote: "But still, why the (to my relatively unintiated non-classical mind) the largely unnecessary digression? And why the excessive blood and seemingly endless fascination with death? And w..."

Roman Clodia wrote: "Steve wrote: "But still, why the (to my relatively unintiated non-classical mind) the largely unnecessary digression? And why the excessive blood and seemingly endless fascination with death? And w..."Thank you for this post, RC. As always, a great help, at least for me to get closer to the Roman mentality - so close and so far from ours.

Desirae wrote: "The conflict of the wedding is a prelude to Troy's destruction; Nestor's recount was a battle between civil and natural order. As the new Lapith king, he married Hippodamia to justify a new age; ye..."

Desirae wrote: "The conflict of the wedding is a prelude to Troy's destruction; Nestor's recount was a battle between civil and natural order. As the new Lapith king, he married Hippodamia to justify a new age; ye..."The notes in my book draw attention to the parallel between the two epics caused by an episode of women-staling.

To me the battle of the centaurs seemed a comic take up of the Troy battles - a parody win which household items substituting real arms and weaponry.

My edition also underlines the sort of competition between young Achilles, he doer of deeds and the old Nestor the speaker of words. The latter almost as effective as the first. The latter wins with 350 lines devoted to his story and in which he points at Achilles' ignorance (his own father had been present in the episode Nestor narrates), and Caeneus was from the same town as Achilles.

My edition also underlines the sort of competition between young Achilles, he doer of deeds and the old Nestor the speaker of words. The latter almost as effective as the first. The latter wins with 350 lines devoted to his story and in which he points at Achilles' ignorance (his own father had been present in the episode Nestor narrates), and Caeneus was from the same town as Achilles.

I found this wonderful painting, in the National Gallery. We have the battle in the background, with its setting clearly indicating a sort of classical 'pick-nick' and in the foreground the loving couple of Cyllary and Hylonome.

I found this wonderful painting, in the National Gallery. We have the battle in the background, with its setting clearly indicating a sort of classical 'pick-nick' and in the foreground the loving couple of Cyllary and Hylonome.

Pietro di Cosimo. Lapiths and Centaurs. Ca. 1487.

And a detail of the couple.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Haha, Elena, I read the centaur love story as a riff on Virgil's Nisus and Euryalus episode in book 9 of the Aeneid (worth a google if you're not familiar with it): another pair of lovers who die t..."

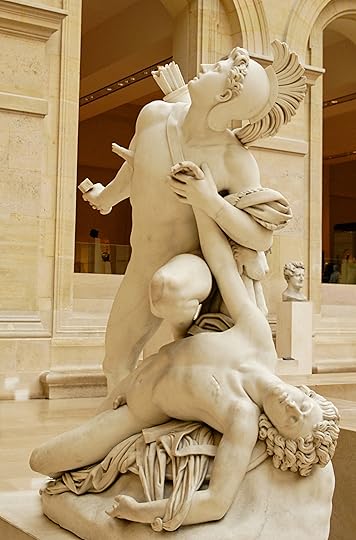

Roman Clodia wrote: "Haha, Elena, I read the centaur love story as a riff on Virgil's Nisus and Euryalus episode in book 9 of the Aeneid (worth a google if you're not familiar with it): another pair of lovers who die t..."RC, Thanks for pointing out that Cyllarus & Hylonome are an intertextual allusion to Nisus & Euryalus:

Jean-Baptiste Roman, Louvre.

I realize you’ve been pointing out the Met’s ubiquitous intertextuality for a while but I’ve just recently caught on. Which reminds me of Nestor telling of his javelin prowess in the Illiad and Ovid having Nestor use it as a pole vault to escape the Boar in Book VIII. I forget where I heard this (was it you?).

I was thinking that Cyllarus & Hylonome is also Ovid showing the humanity of the enemy even if they are half-beasts. Also as Achilles’ arc if featured in this chapter, the Centaur's battle at the wedding seems to be an intertextual allusion to him. The Trojan war was started at a wedding where Discord rolled the golden apple resulting in Paris carrying away Helen. This was the wedding of Peleus & Thetis who gave birth to Achilles and would later enlist Chiron as his tutor. (Also Achilles disguise himself as a woman to avoid the war.)

I don't think it was me who mentioned Nestor and the javelin - but what a supreme Ovidian moment!

I don't think it was me who mentioned Nestor and the javelin - but what a supreme Ovidian moment! One of the great pleasures for me of this text is its pervasive intertextuality - and it's all done with such richness and density. We can spend forever unpacking the allusions and, presumably, not all the texts invoked have come down to us.

Books mentioned in this topic

The Songs of the Kings (other topics)Agamemnon (other topics)

De Rerum Natura (other topics)

The Songs of the Kings (other topics)

The House of Fame (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Barry Unsworth (other topics)Barry Unsworth (other topics)