The Old Curiosity Club discussion

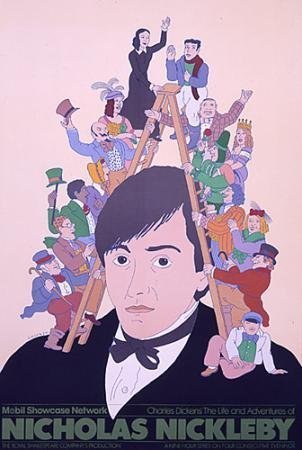

Nicholas Nickleby

>

NN, Chp. 21-25

The following four chapters lead us into a completely new world, the world of theatre, and apart from that, we are also leaving London to finally arrive in Portsmouth as well as in Sketch-land because what is happening is probably not all too important with regard to the major plot line but is clearly meant to provide some comic relief and to side-track the readers for a while.

After Nicholas’s fateful encounter with his uncle, he decides to leave London and to take Smike with him. Before leaving, he once more pays a morning visit to his mother and his sister’s apartment, without actually taking his leave from them – but just to look up at their windows one more time.

Do you think it clever of Nicholas to leave like that? To leave at all? He may appease his uncle’s desire for vengeance, but may he not also deliver his relatives into his uncle’s hands? And is the degree of kindness his uncle has shown them all a justification to trust in him for more kindness?

On their journey which leads them to Portsmouth – where Nicholas has the idea of his and Smike’s working in the harbour or on board a ship – Nicholas tries to elicit more information from his friend as to his early days. What he manages to establish as information runs down to this:

Maybe, this mystery will be cleared up before long, but at the moment it is all Nicholas can learn from Smike, who has taken a very deep liking for our protagonist, probably because it is the first time someone ever showed an interest in him. What do you think of this kind of devotion:

Do you think that a boy like Smike would act like this out of thankfulness, or is it exaggerated on the part of the narrator. In other words, is Smike a realistic, lifelike character for you at all?

Another question: Considering that Dickens was still a young man when writing this novel, what do you think of the tone of the narrative voice, which, during the journey, delights us with observations like the following:

In a wayside inn, our friends finally make the acquaintance of Mr. Vincent Crummles, the director of a troupe of itinerant actors, and his two sons. In the course of a shared meal, Mr. Crummles convinces Nicholas that he should join his troupe because he would never make a good sailor, hitherto never having gained any experience in this special calling. The long and the short of it finally is that Nicholas, who still calls himself Mr. Johnson, agrees to accept Mr. Crummles’s offer.

QUESTIONS AND THOUGHTS

I really wonder that such a proud peacock as Nicholas deigns to join a company of actors, even though his main job is supposed to be that of a playwright – which would allow him to keep himself backstage. Crummles is also interested in getting Smike on the stage, and the question is why Nicholas should allow such a thing to happen: Will Smike, whose outward appearance of misery predestines him for certain roles, in the eyes of Mr. Crummles, be able to learn his lines at all, and to fit in with the other actors? Or is it not more likely for him to make a laughing-stock of himself?

I must say that I like the landlord very much, although he is not even given a name by our narrator. The way he makes Nicholas stay at his inn is marvellous:

There are quite some wily landlords or waiters in the Dickens universe, but this one tops them all, doesn’t he? And just consider how he makes Nicholas share his meal with Mr. Crummles, and how he says,

It’s probably statements like this on the part of Nicholas that allowed this conviction to grow in the landlord:

Is Dickens poking fun here at his protagonist’s pompous way of speaking – a manner which is also shared by Nicholas’s sister? Or is this just a coincidence and was Dickens unaware of what a ridiculous way of talking his protagonist has? Interestingly, the landlord is right with his assumption as to Mr. Crummles’s reaction in that a little later, Crummles says, about Nick:

And he is right, about the comedy!

After Nicholas’s fateful encounter with his uncle, he decides to leave London and to take Smike with him. Before leaving, he once more pays a morning visit to his mother and his sister’s apartment, without actually taking his leave from them – but just to look up at their windows one more time.

Do you think it clever of Nicholas to leave like that? To leave at all? He may appease his uncle’s desire for vengeance, but may he not also deliver his relatives into his uncle’s hands? And is the degree of kindness his uncle has shown them all a justification to trust in him for more kindness?

On their journey which leads them to Portsmouth – where Nicholas has the idea of his and Smike’s working in the harbour or on board a ship – Nicholas tries to elicit more information from his friend as to his early days. What he manages to establish as information runs down to this:

”‘No,’ rejoined the youth, with a melancholy look; ‘a room—I remember I slept in a room, a large lonesome room at the top of a house, where there was a trap-door in the ceiling. I have covered my head with the clothes often, not to see it, for it frightened me: a young child with no one near at night: and I used to wonder what was on the other side. There was a clock too, an old clock, in one corner. I remember that. I have never forgotten that room; for when I have terrible dreams, it comes back, just as it was. I see things and people in it that I had never seen then, but there is the room just as it used to be; that never changes.’”

Maybe, this mystery will be cleared up before long, but at the moment it is all Nicholas can learn from Smike, who has taken a very deep liking for our protagonist, probably because it is the first time someone ever showed an interest in him. What do you think of this kind of devotion:

”‘You will never let me serve you as I ought. You will never know how I think, day and night, of ways to please you.’”

Do you think that a boy like Smike would act like this out of thankfulness, or is it exaggerated on the part of the narrator. In other words, is Smike a realistic, lifelike character for you at all?

Another question: Considering that Dickens was still a young man when writing this novel, what do you think of the tone of the narrative voice, which, during the journey, delights us with observations like the following:

”[…] and in journeys, as in life, it is a great deal easier to go down hill than up. However, they kept on, with unabated perseverance, and the hill has not yet lifted its face to heaven that perseverance will not gain the summit of at last.”

In a wayside inn, our friends finally make the acquaintance of Mr. Vincent Crummles, the director of a troupe of itinerant actors, and his two sons. In the course of a shared meal, Mr. Crummles convinces Nicholas that he should join his troupe because he would never make a good sailor, hitherto never having gained any experience in this special calling. The long and the short of it finally is that Nicholas, who still calls himself Mr. Johnson, agrees to accept Mr. Crummles’s offer.

QUESTIONS AND THOUGHTS

I really wonder that such a proud peacock as Nicholas deigns to join a company of actors, even though his main job is supposed to be that of a playwright – which would allow him to keep himself backstage. Crummles is also interested in getting Smike on the stage, and the question is why Nicholas should allow such a thing to happen: Will Smike, whose outward appearance of misery predestines him for certain roles, in the eyes of Mr. Crummles, be able to learn his lines at all, and to fit in with the other actors? Or is it not more likely for him to make a laughing-stock of himself?

I must say that I like the landlord very much, although he is not even given a name by our narrator. The way he makes Nicholas stay at his inn is marvellous:

“‘Twelve miles,’ said Nicholas, leaning with both hands on his stick, and looking doubtfully at Smike.

‘Twelve long miles,’ repeated the landlord.

‘Is it a good road?’ inquired Nicholas.

‘Very bad,’ said the landlord. As of course, being a landlord, he would say.

‘I want to get on,’ observed Nicholas, hesitating. ‘I scarcely know what to do.’

‘Don’t let me influence you,’ rejoined the landlord. ‘I wouldn’t go on if it was me.’

‘Wouldn’t you?’ asked Nicholas, with the same uncertainty.

‘Not if I knew when I was well off,’ said the landlord. And having said it he pulled up his apron, put his hands into his pockets, and, taking a step or two outside the door, looked down the dark road with an assumption of great indifference.”

There are quite some wily landlords or waiters in the Dickens universe, but this one tops them all, doesn’t he? And just consider how he makes Nicholas share his meal with Mr. Crummles, and how he says,

”‘Lord love you,’ said the landlord, ‘it’s only Mr. Crummles; he isn’t particular.’

‘Is he not?’ asked Nicholas, on whose mind, to tell the truth, the prospect of the savoury pudding was making some impression.

‘Not he,’ replied the landlord. ‘He’ll like your way of talking, I know. But we’ll soon see all about that. Just wait a minute.’”

It’s probably statements like this on the part of Nicholas that allowed this conviction to grow in the landlord:

”’[…] Here; you see that I am travelling in a very humble manner, and have made my way hither on foot. It is more than probable, I think, that the gentleman may not relish my company; and although I am the dusty figure you see, I am too proud to thrust myself into his.’”

Is Dickens poking fun here at his protagonist’s pompous way of speaking – a manner which is also shared by Nicholas’s sister? Or is this just a coincidence and was Dickens unaware of what a ridiculous way of talking his protagonist has? Interestingly, the landlord is right with his assumption as to Mr. Crummles’s reaction in that a little later, Crummles says, about Nick:

”‘There’s genteel comedy in your walk and manner, juvenile tragedy in your eye, and touch-and-go farce in your laugh,’ said Mr. Vincent Crummles. ‘You’ll do as well as if you had thought of nothing else but the lamps, from your birth downwards.’”

And he is right, about the comedy!

Chapters 23 and 24 can be dealt with rather quickly and summarily because they do not really drive the plot on at all but allow the narrator to excel at describing theatrical life in the form of sketch-like episodes. We get to know Mr. Crummles’s pride in the infant phenomenon, his daughter Ninetta, who is supposed to be 10 years old, but has been 10 for quite a while now. We also make the acquaintance of different actors, like Messrs Folair and Lenville, who invite themselves to breakfast at Nicholas’s in order not only to eat at his expense – note, by the way, how Smike tries to set the best bits aside for Nicholas – but also to make sure that they get good roles in the play Nicholas is t write. By the way, writing is probably not the word that is aptest here because Mr. Crummles himself says that being a playwright does not have anything to do with having imagination. All Nicholas has to do is to translate an obscure play from French into English, and to make sure that a pump and two tubs – stage properties Crummles newly acquired and is very proud of – find their way into the action. A pump, two tubs, and Messrs. Folair and Lenville, that is. By the way, Mr. Folair struck me as being extremely friendly with Mr. Crummles as long as the director is facing him, and being extremely critical of him in his absence. Nicholas had better beware of this actor, I’d say.

There also is the graceful Miss Snevellicci, an actress with whom Nicholas definitely flirts unless I am mistaken. The question is whether he does so because he is really attracted by her or whether he is trying to fit in with the troupe. Chapter 24 tells us of a great Bespeak for Miss Snevellici – i.e. an evening in Miss Snevellicci’s honour, with parts (I think one third, because say what you will about Mr. Crummles, he certainly knows which side his bread is buttered on and he drives a hard bargain!) of the takings going to Miss S. – on the occasion of which Nick has his first appearance on the stage, which is, of course – just consider that he is full of ham –, a success.

This chapter also offers Dickens the opportunity to make fun of critics and patrons, as can be seen from Nicholas and Miss Snevellicci’s visits at some houses in Portsmouth.

A very interesting quotation, which may be read as a comment on the theatre in general, can be found in Chapter 23, when Smike first steps into the Portsmouth theatre:

Chapter 25 still keeps up the levity of the general tone and one cannot be too sure if it really adds something crucial to the plot: Be that as it may, it reintroduces Miss Henrietta Petowker, who is a good friend of Mrs. Crummles’s, and Mr. Lillyvick into the story. Miss Petowker and Mr. Lillyvick are going to get married, a situation that is good for quite a lot of comic relief in that Mr. Lillyvick seems keenly aware of all the expense such a wedding will mean for him. On the other hand, he seems to have been driven into that marriage partly by his suspicions as to the worldly interests of the Kenwigs with regard to his property:

May not what is said here by Mr. Lillyvick – and remembering the situation at the Kenwigses, one can say that he is not altogether wrong – also be what Ralph instinctively feels? After all, his family have never seemed to care for him as long as they were well-off, and soon after Mr. Nickleby’s death, they remember that there is an uncle in London. I was struck by the parallelism between the Kenwigses and the Nicklebys here although, of course, the former is purely comic whereas the latter also borders on the dramatic – just consider what happened in Chapter 20.

Be that as it may, with Mr. Lillyvick being married, all hopes to enter into his property will have evaporated for the Kenwigs, and one may ask oneself the question whether Henrietta Petowker is really so much more disinterested than the Kenwigses. Another question is how Mr. and Mrs. Kenwigs will react to this news. I am also doubtful as to whether Mr. Lillyvick will be very happy with his new wife, because it is hard to imagine, for me at least, that a water-rate collector will mix well with itinerant actors, the dignity of his profession and status in society probably inciting many an easy-going actor to make fun of him, as the case of Mr. Folair shows.

The chapter finally ends showing us with how much patience and care Nicholas ensures that his friend Smike learns his lines.

FINAL QUESTIONS

Did you enjoy the last few chapters? Or did you find they were slowing the story down too much?

Which of the new characters do you like best, which ones least?

Do you think it likely for Nicholas to have joined the actors, and to have left London at all?

There also is the graceful Miss Snevellicci, an actress with whom Nicholas definitely flirts unless I am mistaken. The question is whether he does so because he is really attracted by her or whether he is trying to fit in with the troupe. Chapter 24 tells us of a great Bespeak for Miss Snevellici – i.e. an evening in Miss Snevellicci’s honour, with parts (I think one third, because say what you will about Mr. Crummles, he certainly knows which side his bread is buttered on and he drives a hard bargain!) of the takings going to Miss S. – on the occasion of which Nick has his first appearance on the stage, which is, of course – just consider that he is full of ham –, a success.

This chapter also offers Dickens the opportunity to make fun of critics and patrons, as can be seen from Nicholas and Miss Snevellicci’s visits at some houses in Portsmouth.

A very interesting quotation, which may be read as a comment on the theatre in general, can be found in Chapter 23, when Smike first steps into the Portsmouth theatre:

”‘Is this a theatre?’ whispered Smike, in amazement; ‘I thought it was a blaze of light and finery.’

‘Why, so it is,’ replied Nicholas, hardly less surprised; ‘but not by day, Smike—not by day.’”

Chapter 25 still keeps up the levity of the general tone and one cannot be too sure if it really adds something crucial to the plot: Be that as it may, it reintroduces Miss Henrietta Petowker, who is a good friend of Mrs. Crummles’s, and Mr. Lillyvick into the story. Miss Petowker and Mr. Lillyvick are going to get married, a situation that is good for quite a lot of comic relief in that Mr. Lillyvick seems keenly aware of all the expense such a wedding will mean for him. On the other hand, he seems to have been driven into that marriage partly by his suspicions as to the worldly interests of the Kenwigs with regard to his property:

”‘If a bachelor happens to have saved a little matter of money,’ said Mr Lillyvick, ‘his sisters and brothers, and nephews and nieces, look to that money, and not to him; even if, by being a public character, he is the head of the family, or, as it may be, the main from which all the other little branches are turned on, they still wish him dead all the while, and get low-spirited every time they see him looking in good health, because they want to come into his little property. You see that?’”

May not what is said here by Mr. Lillyvick – and remembering the situation at the Kenwigses, one can say that he is not altogether wrong – also be what Ralph instinctively feels? After all, his family have never seemed to care for him as long as they were well-off, and soon after Mr. Nickleby’s death, they remember that there is an uncle in London. I was struck by the parallelism between the Kenwigses and the Nicklebys here although, of course, the former is purely comic whereas the latter also borders on the dramatic – just consider what happened in Chapter 20.

Be that as it may, with Mr. Lillyvick being married, all hopes to enter into his property will have evaporated for the Kenwigs, and one may ask oneself the question whether Henrietta Petowker is really so much more disinterested than the Kenwigses. Another question is how Mr. and Mrs. Kenwigs will react to this news. I am also doubtful as to whether Mr. Lillyvick will be very happy with his new wife, because it is hard to imagine, for me at least, that a water-rate collector will mix well with itinerant actors, the dignity of his profession and status in society probably inciting many an easy-going actor to make fun of him, as the case of Mr. Folair shows.

The chapter finally ends showing us with how much patience and care Nicholas ensures that his friend Smike learns his lines.

FINAL QUESTIONS

Did you enjoy the last few chapters? Or did you find they were slowing the story down too much?

Which of the new characters do you like best, which ones least?

Do you think it likely for Nicholas to have joined the actors, and to have left London at all?

Tristram wrote: "Did you enjoy the last few chapters? Or did you find they were slowing the story down too much?..."

Tristram wrote: "Did you enjoy the last few chapters? Or did you find they were slowing the story down too much?..."Hmmm.... I was listening, rather than reading, the last two chapters, and I kept falling asleep. All the new characters were difficult to keep straight (and, as they are new, I haven't developed my own relationship with them yet, so was apathetic). As I was lagging behind, I nearly considered skipping them and relying on your excellent summaries. BUT... I consider that cheating, so first thing after this afternoon's nap (I swear, I'm as bad as the Fat Boy in Pickwick), I went back to chapters 24 and 25 for One Last Try.

I'm so glad I did! Chapter 24 was okay, and gave me a better sense of who these people are whom Nick and Smike have hooked up with. But chapter 25 provided comic relief that was a breath of fresh air! Not that NN has been a downer in the same way that OT was -- I've appreciated Dickens' lighter touch here. But the wedding was just too delicious. :-)

"Why," said the collector, with a rueful face, "they will have four bridesmaids; I'm afraid they'll make it rather theatrical."

"Oh, no, not at all," replied Nicholas, with an awkward attempt to convert a laugh into a cough."

I've been around some amateur theatrical people, and this exchange made me bust up laughing. There's always drama, even when there isn't or shouldn't be. Oh! The emoting! The thought of them as the principals in a wedding is just too funny.

...how very proud she ought to feel that it was in her power to confer lasting bliss on a deserving object, and how necessary it was for the happiness of mankind in general that women should possess fortitude and resignation on such occasions.

That certainly makes marriage sound like a good deal, doesn't it? And then the later exchange about the noose. One can't help but wonder what Catherine thought as she read these passages!

Re: our lists of memorable Dickens characters... I don't know that "the infant phenomenon" would make the list, but I just laugh every time they refer to her. I think I'll start calling my granddaughter the infant phenomenon. Of course, no one will get it.

I was struck by the parallelism between the Kenwigses and the Nicklebys here a..."

I was struck by the parallelism between the Kenwigses and the Nicklebys here a..."Interestingly, Nicholas seems to be missing that similarity completely.

Tristram wrote: "I must say that I like the landlord very much, although he is not even given a name by our narrator. The way he makes Nicholas stay at his inn is marvellous:..."

Tristram wrote: "I must say that I like the landlord very much, although he is not even given a name by our narrator. The way he makes Nicholas stay at his inn is marvellous:..."The attention to these transitional scenes and minor characters are, for me, what makes Dickens such a master. Just brilliant.

I have to admit, I'm very confused by the plot. I thought Nicholas was going to tutor the Kenwigs for 5 shillings a week. Then, suddenly, he leaves town and joins a theatre. Is he still going to tutor, or did he quit?

I have to admit, I'm very confused by the plot. I thought Nicholas was going to tutor the Kenwigs for 5 shillings a week. Then, suddenly, he leaves town and joins a theatre. Is he still going to tutor, or did he quit? The scenes change so quickly, Dotheboy's Hall is a faint memory now.

Anyway, I enjoyed the theatre scenes and that Nicholas is earning more money--30 shillings! When he turned down the 15-shilling assistant job, it seemed like a reckless move at the time, but now he is earning twice that with work that is more pleasant and creative.

I like that there's a mystery developing around Smike now. Where did he come from? Who took him to the Yorkshire school? I don't know how realistic he is as a character, but he is sympathetic. I always enjoy the scenes with Nicholas and Smike. They make an unlikely, interesting pair, and I find their friendship touching.

I like that there's a mystery developing around Smike now. Where did he come from? Who took him to the Yorkshire school? I don't know how realistic he is as a character, but he is sympathetic. I always enjoy the scenes with Nicholas and Smike. They make an unlikely, interesting pair, and I find their friendship touching.

Tristram wrote: "This week, our instalments will introduce us into the magic world of theatre, a world that Dickens himself was very fascinated by and that we will also encounter in Great Expectations and, to a cer..."

Tristram

I think there is quite frequently a distinct relationship between people and the place they live. In fact, I think Dickens often portrays buildings, homes, and even rooms as very human themselves. As noted earlier, Hablot Browne picks up these relationships as well and his illustrations of physical spaces often take on the personality of a person as much as they are a physical space.

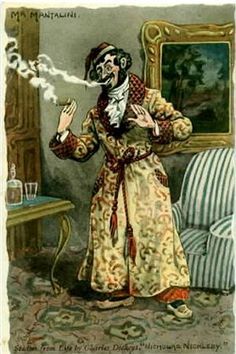

The evil nature of Ralph Nickleby is again reinforced when we read that he expressed little surprise in the failure of Mantalini’s business “insomuch as it had been procured and brought about chiefly by himself.” We now know for certain how he operates as a businessman. Also, if Ralph Nickleby engineered the collapse of Mantalini’s business, then that means he placed Kate in a place that was certain to fail at some point. His evilness seems to have no boundaries.

Tristram

I think there is quite frequently a distinct relationship between people and the place they live. In fact, I think Dickens often portrays buildings, homes, and even rooms as very human themselves. As noted earlier, Hablot Browne picks up these relationships as well and his illustrations of physical spaces often take on the personality of a person as much as they are a physical space.

The evil nature of Ralph Nickleby is again reinforced when we read that he expressed little surprise in the failure of Mantalini’s business “insomuch as it had been procured and brought about chiefly by himself.” We now know for certain how he operates as a businessman. Also, if Ralph Nickleby engineered the collapse of Mantalini’s business, then that means he placed Kate in a place that was certain to fail at some point. His evilness seems to have no boundaries.

Tristram wrote: "Chapters 23 and 24 can be dealt with rather quickly and summarily because they do not really drive the plot on at all but allow the narrator to excel at describing theatrical life in the form of sk..."

I, for one, really enjoy the theatrical chapters and characters. One of Dickens’s great skills is his development and portrayal of minor characters. When these characters are from the world of the theatre, Dickens has even more space to create truly memorable people. I can’t help but also think that many of his descriptions of theatrical characters are very thinly grafted creations of people he knew, observed, or even acted with in his early life.

I, for one, really enjoy the theatrical chapters and characters. One of Dickens’s great skills is his development and portrayal of minor characters. When these characters are from the world of the theatre, Dickens has even more space to create truly memorable people. I can’t help but also think that many of his descriptions of theatrical characters are very thinly grafted creations of people he knew, observed, or even acted with in his early life.

Chapter 21

Chapter 21Well, so much for Kate being the family breadwinner. Interesting how with Nicholas's adventures looking for a job, we always know what the job pays, but not so much with Kate.

1,500+ pounds? My, my, but Mr. Mantalini gets around. Where is he keeping all those horses? I suspect that knife has been sharpened on more than one razor strop.

That footman -- the one who answered the door and received Kate and her mama -- reminded me of Lurch from the Adams Family. Did I hear an inarticulate moan or two?

When Mr. W enters the room and begins touting his wife's qualifications I start wondering who's applying to whom?

I enjoyed this chapter; Dickens having a little fun. Job hunting among the educated but poor in Victorian England. Dickens is showing us quite a cross-section of London business and social life.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 21

Well, so much for Kate being the family breadwinner. Interesting how with Nicholas's adventures looking for a job, we always know what the job pays, but not so much with Kate.

1,500+ p..."

Xan

Yes indeed. I can’t think of another author who gives a greater cross-section of London business and social life than Dickens. For me, 19C London is what Dickens portrays in his novels.

Perhaps the closest we get to south-rural England comes from Hardy and the industrial north from Gaskell. Who do you enjoy as “regional novelists?

Well, so much for Kate being the family breadwinner. Interesting how with Nicholas's adventures looking for a job, we always know what the job pays, but not so much with Kate.

1,500+ p..."

Xan

Yes indeed. I can’t think of another author who gives a greater cross-section of London business and social life than Dickens. For me, 19C London is what Dickens portrays in his novels.

Perhaps the closest we get to south-rural England comes from Hardy and the industrial north from Gaskell. Who do you enjoy as “regional novelists?

Hardy is good if you can stomach his "heartwarming" endings. Never read Gaskell. Haven't read Trollope. Read Jane Eyre and Pride and Prejudice. I'm Victorian Era challenged.

Hardy is good if you can stomach his "heartwarming" endings. Never read Gaskell. Haven't read Trollope. Read Jane Eyre and Pride and Prejudice. I'm Victorian Era challenged.In the U.S. Ivan Doig is good. So is James Lee Burke.

A modern-day novel in the Victorian Era tradition I recommend is "By Gaslight," by Steven Price, a fellow Canadian, Peter. That may have been my best read of 2015 (or was it 2016)?

I'd recommend Trollope but it has to be said that his novels usually don't give a cross-section of Victorian society but rather tend to stick with the upper classes. At least, I cannot remember any working-class people from a Trollope novel.

Tristram wrote: "Will Smike, whose outward appearance of misery predestines him for certain roles, in the eyes of Mr. Crummles, be able to learn his lines at all, and to fit in with the other actors? ..."

Tristram wrote: "Will Smike, whose outward appearance of misery predestines him for certain roles, in the eyes of Mr. Crummles, be able to learn his lines at all, and to fit in with the other actors? ..."My main fear is Smike will be treated like the circus freak.

I'm truly happy Crummles saved Nicholas from sailing. Never was there a young man less suited and more ignorant of a job. He need not worry that upon his return his mother and sister would no longer be alive, because he wouldn't be returning. They would have thrown him overboard.

"Now see here my good man, I don't like your tone of voice."

Overboard!!

Smike would have lasted longer than Nicholas.

-----------------------------

Rum and milk for the trip? I have to say walking long distances in 19th century England must have been quite the sport, what with everyone drunk and rowdy.

------------------------------

There's genteel comedy in your walk and manner, juvenile tragedy in your eye, and touch-and-go farce in your laugh ...

How come I don't see any of that?

A pound a week? Wouldn't everyone be in the theater?

I have to say that Noggs and Miss La Creevy both make better stage presences than Nicholas. Them I'd go see. Not Nicholas.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Hardy is good if you can stomach his "heartwarming" endings. Never read Gaskell. Haven't read Trollope. Read Jane Eyre and Pride and Prejudice. I'm Victorian Era challenged.

In the U.S. Ivan Doig ..."

Hi Xan

Oh, you are not Victorian Era challenged. Anyone who hangs about The Saracen’s Head is in a very exclusive category of Victorians.

I too really enjoy James Lee Burke. Dave would sort out Ralph Nickleby and Squeers in short order.

I’m glad you enjoyed “By Gaslight.” It does offer a great feel for the 19C. Steven Price lives in Victoria where we just moved from. Victoria has the most ”Victorian feel” of any location in Canada. I really miss living there.

In the U.S. Ivan Doig ..."

Hi Xan

Oh, you are not Victorian Era challenged. Anyone who hangs about The Saracen’s Head is in a very exclusive category of Victorians.

I too really enjoy James Lee Burke. Dave would sort out Ralph Nickleby and Squeers in short order.

I’m glad you enjoyed “By Gaslight.” It does offer a great feel for the 19C. Steven Price lives in Victoria where we just moved from. Victoria has the most ”Victorian feel” of any location in Canada. I really miss living there.

I can't find it now, but there was something Nicholas said in chapter 22 that made me think he has no intention of sending money to his mother and sister. I had thought he left home to find a job of sufficient pay to send money home. I guess not.

I can't find it now, but there was something Nicholas said in chapter 22 that made me think he has no intention of sending money to his mother and sister. I had thought he left home to find a job of sufficient pay to send money home. I guess not.

Tristram wrote: "I'd recommend Trollope but it has to be said that his novels usually don't give a cross-section of Victorian society but rather tend to stick with the upper classes. At least, I cannot remember any..."

Tristram wrote: "I'd recommend Trollope but it has to be said that his novels usually don't give a cross-section of Victorian society but rather tend to stick with the upper classes. At least, I cannot remember any..."Middlemarch, which I have never finished, cuts through a cross-section of country life, plus I love Eliot's command of the language. But it is a bit of a slog, and Dorothea, in the beginning, at least, is a pill.

I really love Middlemarch and read it twice so far, but I must read it again, simply to write a review, and to enjoy it. I can't remember the physician's wife's name, but think she is a lot worse to bear than Doro.

What was it, by the way, that Nicholas said which made you think he never had the real intention to send any money home?

What was it, by the way, that Nicholas said which made you think he never had the real intention to send any money home?

Peter wrote: "Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Hardy is good if you can stomach his "heartwarming" endings. Never read Gaskell. Haven't read Trollope. Read Jane Eyre and Pride and Prejudice. I'm Victorian Era challenge..."

I've got House of the Rising Sun on my shelf here but never really taken a look at it yet. If you continue praising J.L.B., you might induce me to start reading it as soon as I finished Aickman.

I've got House of the Rising Sun on my shelf here but never really taken a look at it yet. If you continue praising J.L.B., you might induce me to start reading it as soon as I finished Aickman.

Tristram wrote: "I can't remember the physician's wife's name, but think she is a lot worse to bear than Doro...."

Tristram wrote: "I can't remember the physician's wife's name, but think she is a lot worse to bear than Doro...."I agree, she is. But Dorothea is the first you meet ( and for some time).

I'll get back to you on the Nicholas passage. Right now I'm going bike riding.

Chapter 23

Chapter 23I thoroughly enjoyed this chapter. The Theater! The Theater!!!

I thought Dickens interesting and daring leaving the audience wondering if the young Infant Phenomenon would marry the savage. There also seems to be some question of age, perhaps her being 15 instead of 10. Dickens takes chances with social mores, doesn't he? He also uses the word trousers when describing Mr. Lenville's attire. Saucy trousers?

And Mr. Folair, hahahaha.

[S]he is too good for country boards, and that she ought to be in one of the large houses in London, OR NOWHERE (emphasis mine).

(...)

{off to the side for Nicholas's ears only} There isn't a female child of common sharpness in a charity school, that couldn't do better than that.

But might she be better than you, Mr. Folair?

A pound a week, indeed. That 5 shillings a week sounding good yet, Nicholas?

Lastly, if those lodgings were acceptable to Nicholas, then one wonders about the ones that weren't.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I'm truly happy Crummles saved Nicholas from sailing. Never was there a young man less suited and more ignorant of a job..."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I'm truly happy Crummles saved Nicholas from sailing. Never was there a young man less suited and more ignorant of a job..."Yes, in answer to Tristram's question about whether it's odd that Nicholas is up for joining the theater, I'd say not so much when you consider he first planned to be a sailor, which seems very strange and, as Crummles points out right away, not at all background-appropriate.

Something else strange is how Nicholas bounces between being the straight man who draws out and laughs at other characters' ridiculousness, and being the melodramatic hero who makes scenes. Is this a guy in the heat of the moment or at a cool distance from it? I guess it depends on the moment, but I find it disorienting.

I love the theater chapters, they are my favorites; but, I'm wondering why Nicholas had to leave London at all. No one knew he was there - except Newman Noggs - until he showed up at his mother and sister's house, so why didn't he just stay where he was as teacher for the Kenwigs children. I'm glad he didn't, but I don't understand the big rush to leave town.

And I wonder how Dickens mother felt about being the model for Mrs. Nickleby.

And I wonder how Dickens mother felt about being the model for Mrs. Nickleby.

Here is something about our Crummles:

"It seems likely that Dickens modeled Vincent Crummles and his daughter Miss Ninetta Crummles on the actor-manager T.D. Davenport and his daughter Jean. 'Infant phenomena' were a regular feature of many theatrical shows during the early decades of the nineteenth century. Davenport and his daughter appeared on the Portsmouth stage in March 1837, and playbills announced that the nine-year-old prodigy would play a variety of parts, including Shylock, Little Pickle and Hector Earsplitter, sing songs ranging from 'Since Now I'm Doom'd' to 'I'm a Brisk and Sprightly Lad Just Come Home from Sea' and dance both sailor's hornpipes and Highland flings."

The Westminster Subscription Theatre(Tothill Street) was a quasi-private theatre opened under the management of T. D. Davenport in 1832. Although it never acquired any sort of licence, several noteworthy players began their careers here.

"It seems likely that Dickens modeled Vincent Crummles and his daughter Miss Ninetta Crummles on the actor-manager T.D. Davenport and his daughter Jean. 'Infant phenomena' were a regular feature of many theatrical shows during the early decades of the nineteenth century. Davenport and his daughter appeared on the Portsmouth stage in March 1837, and playbills announced that the nine-year-old prodigy would play a variety of parts, including Shylock, Little Pickle and Hector Earsplitter, sing songs ranging from 'Since Now I'm Doom'd' to 'I'm a Brisk and Sprightly Lad Just Come Home from Sea' and dance both sailor's hornpipes and Highland flings."

The Westminster Subscription Theatre(Tothill Street) was a quasi-private theatre opened under the management of T. D. Davenport in 1832. Although it never acquired any sort of licence, several noteworthy players began their careers here.

The Professional Gentlemen at Madame Mantalini's

Chapter 21

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

After ringing the bell which would summon Madame Mantalini, Kate glanced at the card, and saw that it displayed the name of ‘Scaley,’ together with some other information to which she had not had time to refer, when her attention was attracted by Mr. Scaley himself, who, walking up to one of the cheval-glasses, gave it a hard poke in the centre with his stick, as coolly as if it had been made of cast iron.

‘Good plate this here, Tix,’ said Mr. Scaley to his friend.

‘Ah!’ rejoined Mr. Tix, placing the marks of his four fingers, and a duplicate impression of his thumb, on a piece of sky-blue silk; ‘and this here article warn’t made for nothing, mind you.’

From the silk, Mr. Tix transferred his admiration to some elegant articles of wearing apparel, while Mr. Scaley adjusted his neckcloth, at leisure, before the glass, and afterwards, aided by its reflection, proceeded to the minute consideration of a pimple on his chin; in which absorbing occupation he was yet engaged, when Madame Mantalini, entering the room, uttered an exclamation of surprise which roused him.

‘Oh! Is this the missis?’ inquired Scaley.

‘It is Madame Mantalini,’ said Kate.

‘Then,’ said Mr. Scaley, producing a small document from his pocket and unfolding it very slowly, ‘this is a writ of execution, and if it’s not conwenient to settle we’ll go over the house at wunst, please, and take the inwentory.’

Poor Madame Mantalini wrung her hands for grief, and rung the bell for her husband; which done, she fell into a chair and a fainting fit, simultaneously. The professional gentlemen, however, were not at all discomposed by this event, for Mr. Scaley, leaning upon a stand on which a handsome dress was displayed (so that his shoulders appeared above it, in nearly the same manner as the shoulders of the lady for whom it was designed would have done if she had had it on), pushed his hat on one side and scratched his head with perfect unconcern, while his friend Mr. Tix, taking that opportunity for a general survey of the apartment preparatory to entering on business, stood with his inventory-book under his arm and his hat in his hand, mentally occupied in putting a price upon every object within his range of vision.

Such was the posture of affairs when Mr. Mantalini hurried in; and as that distinguished specimen had had a pretty extensive intercourse with Mr Scaley’s fraternity in his bachelor days, and was, besides, very far from being taken by surprise on the present agitating occasion, he merely shrugged his shoulders, thrust his hands down to the bottom of his pockets, elevated his eyebrows, whistled a bar or two, swore an oath or two, and, sitting astride upon a chair, put the best face upon the matter with great composure and decency.

Commentary:

Another kind of continuity is established in Parts VII through X, where nearly all the plates deal in some way with acting, disguise, or pretense. As a group these plates emphasize the extent to which acting becomes a major metaphor in the novel. Unfortunately for the novel as a whole, the effect is to make those plates in which Nicholas appears seem largely melodramatic, since they seem to imply that there is little difference between the protagonist's life and acting. But such large considerations aside, most of the plates in question are extremely effective. For example, no one is more an actor than Mr. Mantalini in "The Professional Gentlemen at Madame Mantalini's" (ch. 21), except the same man in later plates, or the Kenwigs family.

"You can just give him that 'ere card, and tell him if he wants to speak to me, and save trouble, here I am, that's all"

Chapter 21

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

Kate busied herself in what she had to do, and was silently arranging the various articles of decoration in the best taste she could display, when she started to hear a strange man’s voice in the room, and started again, to observe, on looking round, that a white hat, and a red neckerchief, and a broad round face, and a large head, and part of a green coat were in the room too.

‘Don’t alarm yourself, miss,’ said the proprietor of these appearances. ‘I say; this here’s the mantie-making consarn, an’t it?’

‘Yes,’ rejoined Kate, greatly astonished. ‘What did you want?’

The stranger answered not; but, first looking back, as though to beckon to some unseen person outside, came, very deliberately, into the room, and was closely followed by a little man in brown, very much the worse for wear, who brought with him a mingled fumigation of stale tobacco and fresh onions. The clothes of this gentleman were much bespeckled with flue; and his shoes, stockings, and nether garments, from his heels to the waist buttons of his coat inclusive, were profusely embroidered with splashes of mud, caught a fortnight previously—before the setting-in of the fine weather.

Kate’s very natural impression was, that these engaging individuals had called with the view of possessing themselves, unlawfully, of any portable articles that chanced to strike their fancy. She did not attempt to disguise her apprehensions, and made a move towards the door.

‘Wait a minnit,’ said the man in the green coat, closing it softly, and standing with his back against it. ‘This is a unpleasant bisness. Vere’s your govvernor?’

‘My what—did you say?’ asked Kate, trembling; for she thought ‘governor’ might be slang for watch or money.

‘Mister Muntlehiney,’ said the man. ‘Wot’s come on him? Is he at home?’

‘He is above stairs, I believe,’ replied Kate, a little reassured by this inquiry. ‘Do you want him?’

‘No,’ replied the visitor. ‘I don’t ezactly want him, if it’s made a favour on. You can jist give him that ‘ere card, and tell him if he wants to speak to me, and save trouble, here I am; that’s all.’

With these words, the stranger put a thick square card into Kate’s hand, and, turning to his friend, remarked, with an easy air, ‘that the rooms was a good high pitch;’ to which the friend assented, adding, by way of illustration, ‘that there was lots of room for a little boy to grow up a man in either on ‘em, vithout much fear of his ever bringing his head into contract vith the ceiling.’

The dressing room door being hastily flung open, Mr. Mantalini was disclosed to view

Chapter 21

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘My cup of happiness’s sweetener,’ said Mantalini, approaching his wife with a penitent air; ‘will you listen to me for two minutes?’

‘Oh! don’t speak to me,’ replied his wife, sobbing. ‘You have ruined me, and that’s enough.’

Mr. Mantalini, who had doubtless well considered his part, no sooner heard these words pronounced in a tone of grief and severity, than he recoiled several paces, assumed an expression of consuming mental agony, rushed headlong from the room, and was, soon afterwards, heard to slam the door of an upstairs dressing-room with great violence.

‘Miss Nickleby,’ cried Madame Mantalini, when this sound met her ear, ‘make haste, for Heaven’s sake, he will destroy himself! I spoke unkindly to him, and he cannot bear it from me. Alfred, my darling Alfred.’

With such exclamations, she hurried upstairs, followed by Kate who, although she did not quite participate in the fond wife’s apprehensions, was a little flurried, nevertheless. The dressing-room door being hastily flung open, Mr. Mantalini was disclosed to view, with his shirt-collar symmetrically thrown back: putting a fine edge to a breakfast knife by means of his razor strop.

‘Ah!’ cried Mr. Mantalini, ‘interrupted!’ and whisk went the breakfast knife into Mr. Mantalini’s dressing-gown pocket, while Mr. Mantalini’s eyes rolled wildly, and his hair floating in wild disorder, mingled with his whiskers.

The Country Manager Rehearses a Combat

Chapter 22

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Nicholas was prepared for something odd, but not for something quite so odd as the sight he encountered. At the upper end of the room, were a couple of boys, one of them very tall and the other very short, both dressed as sailors—or at least as theatrical sailors, with belts, buckles, pigtails, and pistols complete—fighting what is called in play-bills a terrific combat, with two of those short broad-swords with basket hilts which are commonly used at our minor theatres. The short boy had gained a great advantage over the tall boy, who was reduced to mortal strait, and both were overlooked by a large heavy man, perched against the corner of a table, who emphatically adjured them to strike a little more fire out of the swords, and they couldn’t fail to bring the house down, on the very first night.

‘Mr. Vincent Crummles,’ said the landlord with an air of great deference. ‘This is the young gentleman.’

Mr. Vincent Crummles received Nicholas with an inclination of the head, something between the courtesy of a Roman emperor and the nod of a pot companion; and bade the landlord shut the door and begone.

‘There’s a picture,’ said Mr. Crummles, motioning Nicholas not to advance and spoil it. ‘The little ‘un has him; if the big ‘un doesn’t knock under, in three seconds, he’s a dead man. Do that again, boys.’

The two combatants went to work afresh, and chopped away until the swords emitted a shower of sparks: to the great satisfaction of Mr. Crummles, who appeared to consider this a very great point indeed. The engagement commenced with about two hundred chops administered by the short sailor and the tall sailor alternately, without producing any particular result, until the short sailor was chopped down on one knee; but this was nothing to him, for he worked himself about on the one knee with the assistance of his left hand, and fought most desperately until the tall sailor chopped his sword out of his grasp. Now, the inference was, that the short sailor, reduced to this extremity, would give in at once and cry quarter, but, instead of that, he all of a sudden drew a large pistol from his belt and presented it at the face of the tall sailor, who was so overcome at this (not expecting it) that he let the short sailor pick up his sword and begin again. Then, the chopping recommenced, and a variety of fancy chops were administered on both sides; such as chops dealt with the left hand, and under the leg, and over the right shoulder, and over the left; and when the short sailor made a vigorous cut at the tall sailor’s legs, which would have shaved them clean off if it had taken effect, the tall sailor jumped over the short sailor’s sword, wherefore to balance the matter, and make it all fair, the tall sailor administered the same cut, and the short sailor jumped over his sword. After this, there was a good deal of dodging about, and hitching up of the inexpressibles in the absence of braces, and then the short sailor (who was the moral character evidently, for he always had the best of it) made a violent demonstration and closed with the tall sailor, who, after a few unavailing struggles, went down, and expired in great torture as the short sailor put his foot upon his breast, and bored a hole in him through and through.

Commentary:

The seedy theatrical company which shelters Nicholas (under the pseudonym "Mr. Johnson") as resident playwright, adapter, and translator of French farces is the subject of considerable satire in Nicholas Nickleby, based in part on the young writer's aspirations to be a thespian and in part on his close personal relationships with such figures of nineteenth-century theatre as the great actor-manager of Drury Lane, William C. Macready (1793-1873), whose restoration of the original text of Shakespeare's King Lear he praised in a theatrical review in The Examiner for 4 February 1838. The core of the company, the Crummles family, Dickens describes in some detail in chapter 22, "Nicholas, accompanied by Smike, sallies forth to seek his Fortune. He encounters Mr. Vincent Crummles; and who he was, is herein made manifest," and chapter 23. According to Nicholas Bentley et al. in The Dickens Index, Dickens based Crummles and his daughter Ninetta, "The Infant Phenomenon," on actor-manager T. D. Davenport (1792-1851) and his daughter Jean Margaret (1829-1903), one of the most celebrated juvenile actresses of the period. Undoubtedly the sequence involving the Crummles family is loosely based on Davenport's leasing the Portsmouth Theatre the year before to showcase the precocious talents of eight-year-old Jean, whom Dickens had seen make her stage debut at The Richmond Theatre, Surrey, in 1836. Nicholas and Smike stumble upon Crummles quite by accident at a road-side inn, where the manager is rehearsing a pair of juvenile actors in a duelling scene from a transpontine drama of the type popular in the period.

In Phiz's October 1838 steel engraving Smike is notably startled by the violence of the cutlass duel by the mismatched "sailors," whereas Nicholas in respectable beaver and frockcoat (rear, centre right) is only moderately interested for he perceives, as his companion does not, that this is merely theatre and not reality.

In this plate, Browne implies a complex relation of acting to reality by including both a portrait of the fat host, who has some resemblance to Crummles, and a picture of Don Quixote and San Cho Panza. Thus, the illustration is a graphic version of a novel that deals with acting and pretense, and within that illustration there is yet another, based upon a book which is in turn a fiction about fiction, and the chivalric pretensions of Don Quixote. But the Quixote reference here applies also to Nicholas and Smike, who have set out in the world to seek their fortunes.

Mr. Crummles looked, from time to time, with great interest at Smike

Chapter 22

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘You are going that way?’ asked the manager.

‘Ye-yes,’ said Nicholas. ‘Yes, I am.’

‘Do you know the town at all?’ inquired the manager, who seemed to consider himself entitled to the same degree of confidence as he had himself exhibited.

‘No,’ replied Nicholas.

‘Never there?’

‘Never.’

Mr. Vincent Crummles gave a short dry cough, as much as to say, ‘If you won’t be communicative, you won’t;’ and took so many pinches of snuff from the piece of paper, one after another, that Nicholas quite wondered where it all went to.

While he was thus engaged, Mr. Crummles looked, from time to time, with great interest at Smike, with whom he had appeared considerably struck from the first. He had now fallen asleep, and was nodding in his chair.

‘Excuse my saying so,’ said the manager, leaning over to Nicholas, and sinking his voice, ‘but what a capital countenance your friend has got!’

‘Poor fellow!’ said Nicholas, with a half-smile, ‘I wish it were a little more plump, and less haggard.’

‘Plump!’ exclaimed the manager, quite horrified, ‘you’d spoil it for ever.’

‘Do you think so?’

‘Think so, sir! Why, as he is now,’ said the manager, striking his knee emphatically; ‘without a pad upon his body, and hardly a touch of paint upon his face, he’d make such an actor for the starved business as was never seen in this country. Only let him be tolerably well up in the Apothecary in Romeo and Juliet, with the slightest possible dab of red on the tip of his nose, and he’d be certain of three rounds the moment he put his head out of the practicable door in the front grooves O.P.’

‘You view him with a professional eye,’ said Nicholas, laughing.

‘And well I may,’ rejoined the manager. ‘I never saw a young fellow so regularly cut out for that line, since I’ve been in the profession. And I played the heavy children when I was eighteen months old.’

The Rehearsal

Chapter 23

Felix O. C. Darley

1861 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

As Mrs. Vincent Crummles recrossed back to the table, there bounded on to the stage from some mysterious inlet, a little girl in a dirty white frock with tucks up to the knees, short trousers, sandaled shoes, white spencer, pink gauze bonnet, green veil and curl papers; who turned a pirouette, cut twice in the air, turned another pirouette, then, looking off at the opposite wing, shrieked, bounded forward to within six inches of the footlights, and fell into a beautiful attitude of terror, as a shabby gentleman in an old pair of buff slippers came in at one powerful slide, and chattering his teeth, fiercely brandished a walking-stick.

"They are going through the Indian Savage and the Maiden," said Mrs. Crummles.

"Oh!" said the manager, "the little ballet interlude. Very good, go on. A little this way, if you please, Mr. Johnson. That'll do. Now!"

The manager clapped his hands as a signal to proceed, and the savage, becoming ferocious, made a slide towards the maiden; but the maiden avoided him in six twirls, and came down, at the end of the last one, upon the very points of her toes. This seemed to make some impression upon the savage; for, after a little more ferocity and chasing of the maiden into corners, he began to relent, and stroked his face several times with his right thumb and four fingers, thereby intimating that he was struck with admiration of the maiden's beauty. Acting upon the impulse of this passion, he (the savage) began to hit himself severe thumps in the chest, and to exhibit other indications of being desperately in love, which being rather a prosy proceeding, was very likely the cause of the maiden's falling asleep; whether it was or no, asleep she did fall, sound as a church, on a sloping bank, and the savage perceiving it, leant his left ear on his left hand, and nodded sideways, to intimate to all whom it might concern that she was asleep, and no shamming. Being left to himself, the savage had a dance, all alone. Just as he left off, the maiden woke up, rubbed her eyes, got off the bank, and had a dance all alone too — such a dance that the savage looked on in ecstasy all the while, and when it was done, plucked from a neighbouring tree some botanical curiosity, resembling a small pickled cabbage, and offered it to the maiden, who at first wouldn't have it, but on the savage shedding tears relented. Then the savage jumped for joy; then the maiden jumped for rapture at the sweet smell of the pickled cabbage. Then the savage and the maiden danced violently together, and, finally, the savage dropped down on one knee, and the maiden stood on one leg upon his other knee; thus concluding the ballet, and leaving the spectators in a state of pleasing uncertainty, whether she would ultimately marry the savage, or return to her friends.

"Very well indeed," said Mr. Crummles; "bravo!"

Commentary:

Since so much of the satire in Nicholas Nickleby involves the deplorable state of the English theatre, the chapters involving the provincial company under the management of Vincent Crummles, who recruits both Mr. Johnson (Nicholas) and his servant, Smike, to take roles in Romeo and Juliet. Nicholas and Smike (carrying bundle) are in the background of this illustration of the Infant Phenomenon's dancing in rehearsal.

The passage realized occurs as Nicholas and Smike enter the Portsmouth theatre with the company's manager, Vincent Crummles, in Chapter 23 of 1861 edition of The Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, although the quotation beneath the frontispiece does not specifically mention this chapter. As is typical of this edition, the chapter title ("Treats of the Company of Mr. Vincent Crummles, and of his Affairs, Domestic and Theatrical") is given in both a prefatory "Table of Contents" (v to vii) and in capitals immediately under the chapter number; this chapter was first published in Part Seven (October 1838) in the Chapman and Hall monthly serialization. However, the Phiz illustrations for this number concern events in Chapters 22 and 24, so that Darley was breaking with the precedent set by the original British publication in describing the rehearsal in the theatre at Portsmouth as Nicholas's formal introduction to the British stage, for which he will serve as resident playwright, freely translating plays from French without regard for Continental copyright — a common practice for English acting companies.

Independent of Darley's choices of subjects for the frontispieces of the three volumes of Nicholas Nickleby, Fred Barnard elected to provide a more realistic version of an earlier part of the same scene in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition, with Nicholas and the other onlookers left rear, and the principals centre-stage: The Indian and The Maiden — Chap. xxiii. Whereas Barnard's approach is to render the scene caught in the midst of action, with the "Indian" gnashing his teeth and menacing the "Maiden" (in mid-pirouette) with his cane, Darley has captured the moment of stasis when the dance ends, all emotion spent, and the dancers freeze, striking a pose to take a round of applause.

Comparing the two, one can better appreciate the elegance of Darley's treatment, which fails, nevertheless, to capture the energy and humor of the text as Barnard's does. Whereas Barnard focuses on the contrasting emotions and postures of the performers, Darley gives the context of the scene, showing the footlights in the foreground, and a corpulent Crummles and Nicholas in the background (with umbrella), with Smike carrying a small bundle on the end of a stick to intimate that the pair are travellers — and Mrs. Crummles, oblivious to the dancers and absorbed in a book (extreme left). Although the scene occurs in the 1830s, Darley has given the male dancer clothing that is consistent with the fashions of the 1980s (still, improbably, wearing his silk hat!), but has put the female ("The Infant Phenomenon") in a ballet dress. Without doubt, the Crummles of Darley is more human and less of a caricature than the figure offered by Phiz in this sequence of theatrical illustrations. The stage set (a forest with a Martello tower to the left) completes the theatrical scene, with the Phenomenon dressed exactly as in the text and the beautifully attired male dancer's cane lying beside him on the boards. However, the "Indian" is wearing street shoes rather than buff slippers, and is neither "shabby" nor "old," suggesting that Darley has deliberately deviated from the text to provide a more pleasing composition, making the fifteen-year-old Ninetta (The Phenomenon) look less frowzy than he might have, given Dickens's description.

The Indian Savage and the Maiden

Chapter 23

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

As Mrs. Vincent Crummles recrossed back to the table, there bounded on to the stage from some mysterious inlet, a little girl in a dirty white frock with tucks up to the knees, short trousers, sandaled shoes, white spencer, pink gauze bonnet, green veil and curl papers; who turned a pirouette, cut twice in the air, turned another pirouette, then, looking off at the opposite wing, shrieked, bounded forward to within six inches of the footlights, and fell into a beautiful attitude of terror, as a shabby gentleman in an old pair of buff slippers came in at one powerful slide, and chattering his teeth, fiercely brandished a walking-stick.

‘They are going through the Indian Savage and the Maiden,’ said Mrs Crummles.

‘Oh!’ said the manager, ‘the little ballet interlude. Very good, go on. A little this way, if you please, Mr. Johnson. That’ll do. Now!’

The manager clapped his hands as a signal to proceed, and the savage, becoming ferocious, made a slide towards the maiden; but the maiden avoided him in six twirls, and came down, at the end of the last one, upon the very points of her toes. This seemed to make some impression upon the savage; for, after a little more ferocity and chasing of the maiden into corners, he began to relent, and stroked his face several times with his right thumb and four fingers, thereby intimating that he was struck with admiration of the maiden’s beauty. Acting upon the impulse of this passion, he (the savage) began to hit himself severe thumps in the chest, and to exhibit other indications of being desperately in love, which being rather a prosy proceeding, was very likely the cause of the maiden’s falling asleep; whether it was or no, asleep she did fall, sound as a church, on a sloping bank, and the savage perceiving it, leant his left ear on his left hand, and nodded sideways, to intimate to all whom it might concern that she was asleep, and no shamming. Being left to himself, the savage had a dance, all alone. Just as he left off, the maiden woke up, rubbed her eyes, got off the bank, and had a dance all alone too—such a dance that the savage looked on in ecstasy all the while, and when it was done, plucked from a neighbouring tree some botanical curiosity, resembling a small pickled cabbage, and offered it to the maiden, who at first wouldn’t have it, but on the savage shedding tears relented. Then the savage jumped for joy; then the maiden jumped for rapture at the sweet smell of the pickled cabbage. Then the savage and the maiden danced violently together, and, finally, the savage dropped down on one knee, and the maiden stood on one leg upon his other knee; thus concluding the ballet, and leaving the spectators in a state of pleasing uncertainty, whether she would ultimately marry the savage, or return to her friends.

Commentary:

Role, spectacle and meaning are subtly intertwined throughout the narrative. Attracted as he was by vivacious theatre folk, keen as he was to maintain the extraordinarily high volume of sales for this new work, Dickens was not using the "pantomimic" just to entertain. Far from presenting a kind of escapist romp, he was offering his readers a vehicle through which he could express the world-view earlier expressed in his essay on "The Pantomime of Life" in Bentley's Miscellany: that "the close resemblance which the clowns of the stage bear to those of every-day life is perfectly extraordinary"; the implication being that society itself is a pantomime, in which people act outrageously and risibly. This invites the Bahktinian corollary that the carnavelesque has a subversive purpose, providing a diversity of voices and provoking a diversity of responses, producing fluidity, liberation and change — providing, in fact, "an opportunity for changing his readers' basic stories about the nature of reality". Bahktinian readings, bringing out the fantastical in the text, and showing the subversive purposes it serves, seem highly appropriate here. After all, this was the novel that had the most direct and specific impact of all Dickens's novels, making the so-called "Yorkshire schools" notorious, and forcing their closure (see Ackroyd). As in Oliver Twist, which he was finishing while writing the earlier chapters, the general idea was to show goodness endangered but finally triumphant. But the Crummleses epitomise the author's current approach to the conflict involved, as a struggle dramatic in its intensity, far-reaching in its possibilities, and heroic to the core.

In this reading, the Crummles episodes do not constitute "a glorious fragment," as Paul Schlicke suggests in Dickens and Popular Entertainment, but are a key to our understanding of the whole novel. Oliver Twist cannot carry the day for himself. He is, in a sense, lily-livered, that is to say, he is at once pure and weak. "Why, where's your spirit?" asks the Dodger, when the boy yearns to be restored to Mr Brownlow's in Chapter 18 of that novel. Oliver has to be rescued and reinstated by others, and by fate, in the manner of life to which his mother had once been accustomed. Nicholas is different. He is the first of Dickens's heroes to accomplish such a reinstatement for himself. However, his role as hero, like the stage Romeo's, has to be grown into and mastered. He may already look the part, but he is not quite nineteen at the beginning, and has not yet adopted it. Dickens would have been thoroughly conversant with Rousseau's ideas. and not just through his childhood reading of Sandford and Merton. In another of his essays, for instance, he roundly criticises the French thinker's notion of "The Noble Savage" as "nonsense". But as for the period that we now call adolescence, Dickens was evidently more in tune with his ideas. Rousseau saw this time as a crucial period, a kind of "second birth," a time when "ordinary educations end" and when, for example, the boy "begins to feel himself in his fellows, to be moved by their complaints and to suffer from their pains". This last is very much the case with Nicholas when he travels to Dotheboys Hall and sees the ill-treated boys there, among whom he particularly notices Smike: "He was such a timid, broken-spirited creature, that Nicholas could not help exclaiming, 'Poor fellow!'"

The Great Bespeak for Miss Snevellici

Chapter 24

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

At last, the orchestra left off, and the curtain rose upon the new piece. The first scene, in which there was nobody particular, passed off calmly enough, but when Miss Snevellicci went on in the second, accompanied by the phenomenon as child, what a roar of applause broke out! The people in the Borum box rose as one man, waving their hats and handkerchiefs, and uttering shouts of ‘Bravo!’ Mrs. Borum and the governess cast wreaths upon the stage, of which, some fluttered into the lamps, and one crowned the temples of a fat gentleman in the pit, who, looking eagerly towards the scene, remained unconscious of the honour; the tailor and his family kicked at the panels of the upper boxes till they threatened to come out altogether; the very ginger-beer boy remained transfixed in the centre of the house; a young officer, supposed to entertain a passion for Miss Snevellicci, stuck his glass in his eye as though to hide a tear. Again and again Miss Snevellicci curtseyed lower and lower, and again and again the applause came down, louder and louder. At length, when the phenomenon picked up one of the smoking wreaths and put it on, sideways, over Miss Snevellicci’s eye, it reached its climax, and the play proceeded.

But when Nicholas came on for his crack scene with Mrs. Crummles, what a clapping of hands there was! When Mrs. Crummles (who was his unworthy mother), sneered, and called him ‘presumptuous boy,’ and he defied her, what a tumult of applause came on! When he quarrelled with the other gentleman about the young lady, and producing a case of pistols, said, that if he was a gentleman, he would fight him in that drawing-room, until the furniture was sprinkled with the blood of one, if not of two—how boxes, pit, and gallery, joined in one most vigorous cheer! When he called his mother names, because she wouldn’t give up the young lady’s property, and she relenting, caused him to relent likewise, and fall down on one knee and ask her blessing, how the ladies in the audience sobbed! When he was hid behind the curtain in the dark, and the wicked relation poked a sharp sword in every direction, save where his legs were plainly visible, what a thrill of anxious fear ran through the house! His air, his figure, his walk, his look, everything he said or did, was the subject of commendation. There was a round of applause every time he spoke. And when, at last, in the pump-and-tub scene, Mrs. Grudden lighted the blue fire, and all the unemployed members of the company came in, and tumbled down in various directions—not because that had anything to do with the plot, but in order to finish off with a tableau—the audience (who had by this time increased considerably) gave vent to such a shout of enthusiasm as had not been heard in those walls for many and many a day.

In short, the success both of new piece and new actor was complete, and when Miss Snevellicci was called for at the end of the play, Nicholas led her on, and divided the applause.

Commentary:

In Ch. 24, "Of the Great Bespeak for Miss Snevellicci, and the first Appearance of Nicholas upon any Stage" (Part 8, November 1838), Nicholas (under the alias "Mr. Johnson"), Miss Snevellicci (the subject of the "bespeak" or benefit performance), and the Infant Phenomenon canvass Portsmouth for donations from wealthy patrons. The opening night, despite the apparent chaos in the audience suggested in Phiz's illustration, is highly successful, at least commercially, thanks to the financial support of Mr. and Mrs. Borum, who attend the bespeak with their children Augustus, Charlotte, and Emma (left). Dickens once again satirizes both the early Victorian theatre and the artistic tastes of the rising middle class — the very class that is purchasing the monthly parts of his novels in such numbers.

The illustration shows nothing of the actors and only a bit of the stage; because of the way they are framed by a scenic flat, footlights, the left side of the stage, and theorchestra, the members of the audience appear to be the ones Putting on the performance. Much in the style of a caricaturist of individual faces, Phiz has stressed the audience's oddities, their individual eccentricities and exaggerated behavior, which is as conventionalized in its way as actors' — the overeffusiveness of the Borums, the stereotyped demeanor of the smitten young officer, the transfixion of the ginger-beer boy. All of this is in the text except for the basic graphic device, the exclusion of the actors and the theatrical framing of the audience.

"As an exquisite embodiment of the poet's visions, and a realisation of human intellectuality"

Chapter 24

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

The first house to which they bent their steps, was situated in a terrace of respectable appearance. Miss Snevellicci’s modest double-knock was answered by a foot-boy, who, in reply to her inquiry whether Mrs. Curdle was at home, opened his eyes very wide, grinned very much, and said he didn’t know, but he’d inquire. With this he showed them into a parlour where he kept them waiting, until the two women-servants had repaired thither, under false pretences, to see the play-actors; and having compared notes with them in the passage, and joined in a vast quantity of whispering and giggling, he at length went upstairs with Miss Snevellicci’s name.

Now, Mrs. Curdle was supposed, by those who were best informed on such points, to possess quite the London taste in matters relating to literature and the drama; and as to Mr. Curdle, he had written a pamphlet of sixty-four pages, post octavo, on the character of the Nurse’s deceased husband in Romeo and Juliet, with an inquiry whether he really had been a ‘merry man’ in his lifetime, or whether it was merely his widow’s affectionate partiality that induced her so to report him. He had likewise proved, that by altering the received mode of punctuation, any one of Shakespeare’s plays could be made quite different, and the sense completely changed; it is needless to say, therefore, that he was a great critic, and a very profound and most original thinker.

‘Well, Miss Snevellicci,’ said Mrs. Curdle, entering the parlour, ‘and how do you do?’

Miss Snevellicci made a graceful obeisance, and hoped Mrs. Curdle was well, as also Mr. Curdle, who at the same time appeared. Mrs. Curdle was dressed in a morning wrapper, with a little cap stuck upon the top of her head. Mr Curdle wore a loose robe on his back, and his right forefinger on his forehead after the portraits of Sterne, to whom somebody or other had once said he bore a striking resemblance.

‘I venture to call, for the purpose of asking whether you would put your name to my bespeak, ma’am,’ said Miss Snevellicci, producing documents.

‘Oh! I really don’t know what to say,’ replied Mrs. Curdle. ‘It’s not as if the theatre was in its high and palmy days—you needn’t stand, Miss Snevellicci—the drama is gone, perfectly gone.’

‘As an exquisite embodiment of the poet’s visions, and a realisation of human intellectuality, gilding with refulgent light our dreamy moments, and laying open a new and magic world before the mental eye, the drama is gone, perfectly gone,’ said Mr. Curdle.

‘What man is there, now living, who can present before us all those changing and prismatic colours with which the character of Hamlet is invested?’ exclaimed Mrs. Curdle.

‘What man indeed—upon the stage,’ said Mr. Curdle, with a small reservation in favour of himself. ‘Hamlet! Pooh! ridiculous! Hamlet is gone, perfectly gone.’

Quite overcome by these dismal reflections, Mr. and Mrs. Curdle sighed, and sat for some short time without speaking. At length, the lady, turning to Miss Snevellicci, inquired what play she proposed to have.

Commentary:

For young people to be dressed ridiculously is deeply significant. It indicates that something is wrong, more generally, in the way they are being treated. Smike is a shambles. The lame, skinny, gangling eighteen- or nineteen-year-old, around the same age as Nicholas, is first seen in a very small boy's suit, which is naturally "absurdly short in the arms and legs," a large, decrepit pair of overboots such as farmers might wear, and his old child's neckfrill half-hidden by a "coarse, man's neckerchief". This youth's predicament, wedged between childhood and adulthood and unable to advance from one to the other, is grotesquely manifested here. The Crummles's fifteen-year-old daughter has also been dressed inappropriately for her age: the "Infant Phenomenon" is got up to look as if she is ten, with sandals, a pink bonnet and so on. This could be seen as grotesque too, but the pink and the frills and the flounces soften the effect. Her exploitation, though recognised for what it is, especially when the naughty Borum boys torment her in Chapter 24, bothers Dickens less. This child is a voluntary victim. Demanding attention to her costume even when off-stage — requiring "one leg of the little white trousers" to be even with the other —, she is a theatre child, and has evidently chosen to identify herself as such.

Nicholas instructs Smike in the art of acting

Chapter 25

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

As there was no performance that night, Mr. Crummles declared his intention of keeping it up till everything to drink was disposed of; but Nicholas having to play Romeo for the first time on the ensuing evening, contrived to slip away in the midst of a temporary confusion, occasioned by the unexpected development of strong symptoms of inebriety in the conduct of Mrs. Grudden.

To this act of desertion he was led, not only by his own inclinations, but by his anxiety on account of Smike, who, having to sustain the character of the Apothecary, had been as yet wholly unable to get any more of the part into his head than the general idea that he was very hungry, which—perhaps from old recollections—he had acquired with great aptitude.

‘I don’t know what’s to be done, Smike,’ said Nicholas, laying down the book. ‘I am afraid you can’t learn it, my poor fellow.’

‘I am afraid not,’ said Smike, shaking his head. ‘I think if you—but that would give you so much trouble.’

‘What?’ inquired Nicholas. ‘Never mind me.’

‘I think,’ said Smike, ‘if you were to keep saying it to me in little bits, over and over again, I should be able to recollect it from hearing you.’

‘Do you think so?’ exclaimed Nicholas. ‘Well said. Let us see who tires first. Not I, Smike, trust me. Now then. Who calls so loud?’

‘“Who calls so loud?”’ said Smike.

‘“Who calls so loud?”’ repeated Nicholas.

‘“Who calls so loud?”’ cried Smike.

Thus they continued to ask each other who called so loud, over and over again; and when Smike had that by heart Nicholas went to another sentence, and then to two at a time, and then to three, and so on, until at midnight poor Smike found to his unspeakable joy that he really began to remember something about the text.

Commentary: