21st Century Literature discussion

This topic is about

Austerlitz

2018 Book Discussions

>

Austerlitz - 4 - Whole Book (Spoilers Allowed) (Oct 2018)

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Lia

(new)

-

added it

Oct 01, 2018 06:29AM

Thank you for reading Austerlitz with us. Please share your thoughts or links to other resources related to Austerlitz, spoilers are allowed in this folder.

Thank you for reading Austerlitz with us. Please share your thoughts or links to other resources related to Austerlitz, spoilers are allowed in this folder.

reply

|

flag

Camie wrote: "Did this drive anyone else crazy?"

Camie wrote: "Did this drive anyone else crazy?"I found myself drifting in and out of conscious focus once I get “sucked in.” I’m following the plot, my eyes moving, I’m more or less parsing what’s being said, roughly processing the images and quotes, not necessarily logically, more by free association.

But then suddenly something jolts me out of that, and I have to look around to see who is speaking: is the narrator talking about his own traveling, his memory, his sympathy, or are we still dealing with A’s reported speech?

So for me, the “A says” barely register. I know they are there, but it’s not more intrusive than the incredible evenness of the tone (Austerlitz doesn’t seem to get angry or resentful or rage or anything, does he? No raised voices here, just melancholy and clinical diagnosis.) I don’t mean this in a bad way, but Sebald lulls me into oblivion.

I liked the book ok. It is set up well from the start. We know these men have met, and that Austerlitz is largely the one reminiscing here. Quite early on I started to notice how often the words " said Austerlitz " were repeated. I didn't actually go back and count but sometimes it was twice on a page. Occasionally "Austerlitz continued" is used, but overall it started to get very annoying to me. There aren't many characters to mix up here, it's an easy story to follow, there's not much question who is telling it. Maybe it suffered in the German- English translation but I started to wonder why we needed to be reminded so often who was speaking. Anyone else bothered by this? If not, perhaps I should sign this Cranky Reader.

I liked the book ok. It is set up well from the start. We know these men have met, and that Austerlitz is largely the one reminiscing here. Quite early on I started to notice how often the words " said Austerlitz " were repeated. I didn't actually go back and count but sometimes it was twice on a page. Occasionally "Austerlitz continued" is used, but overall it started to get very annoying to me. There aren't many characters to mix up here, it's an easy story to follow, there's not much question who is telling it. Maybe it suffered in the German- English translation but I started to wonder why we needed to be reminded so often who was speaking. Anyone else bothered by this? If not, perhaps I should sign this Cranky Reader.

Sorry Lia I accidentally deleted my first statement, so I have resubmitted it - but we are out of order in our comments, lol.

Sorry Lia I accidentally deleted my first statement, so I have resubmitted it - but we are out of order in our comments, lol.I understand what you are saying and agree it may be true one can get caught up in the words ( or wording) instead of the story especially in print. I wonder about the audio version ?

I've read many reviews and no one else mentions what I'm talking about so perhaps it just bothered me.

I did have to chuckle when I read that the English translation has a good number fewer pages than the German, thinking it could have been even shorter had we not had all of the "who's telling the story " reminders.

Thanks for explaning! I was so sure I saw a post, but then I can’t verify my memory. I thought, maybe if I reach for the web archive, put it in slow motion... :p

Thanks for explaning! I was so sure I saw a post, but then I can’t verify my memory. I thought, maybe if I reach for the web archive, put it in slow motion... :p Speaking of repetitiveness, Sebald’s writing style very strongly reminds me of Ishiguro — Austerlitz especially reminds me of The Unconsoled style wise, but in terms of tropes and themes, When We Were Orphans and Never Let Me Go also seem close.

There are certain scenes in Austerlitz that immediately felt like deja vu — like I’ve read the exact same cast (down to the struggling hotel porter), same set, same pattern, same lostness, same headspace in Ishiguro’s universe. This uncanny feeling of deja vu is much more pronounced in The Unconsoled, to the point where it feels like a gimmick.

But I think Sebald is also weaving a lot of recurring elements that echo through the text, or resonate with some random picture that didn’t make a lot of sense at first, until you read on, and a casual, low key remark makes you think about that picture. I think that’s a kind of repetition too, not unlike all the “Austerlitz said.”

And this eternal recurrence, this intrusive repetition, makes me feel slightly spooked, unsettled. (Not that I dislike it.)

https://m.france24.com/en/20181002-fr...

https://m.france24.com/en/20181002-fr...Not directly about Sebald or Austerlitz, but I thought the sensibility is strangely relevant:

After heroically delivering a message in World War I, French pigeon Le Vaillant died of gas poisoning. A century later, it looks as though he and the thousands of other animals killed in the conflict will now be remembered with a monument in Paris.

Especially curious that the French government is resisting that, but the people remember!

“We want [it there] because the local mayor supports the project and it is where horses were requisitioned for the war,”

I love how memory can morph into material architecture!

I just finished this today. I thought I was going to love it & rave about it forever but unfortunately on finishing it, it's not quite one I'd want to re-read, it didn't make it to my Favourites shelf & I rated it 4 stars. For most of the book I thought it was going to be 5 stars. Did anyone else think the same?

I enjoyed so many aspects of this book but I think it was the ending that disappointed. I think Sebald wanted us to feel this but I needed the story to be wrapped up a little more. I'm so glad to have read this. His writing is exceptional, I even loved the long sentences. It was heartbreaking without being sentimental. It has so much going for it but the ending is too much like a sudden stop (and this is one of my pet peeves!). After including such long, flowing prose the story is suddenly broken. Could there have been a sequel if Sebald hadn't died so unexpectedly? I understand, Camie, why you might feel like a 'cranky reader', I think with a fantastic conclusion the little gripes like being reminded who is speaking could have been forgotten.

I enjoyed so many aspects of this book but I think it was the ending that disappointed. I think Sebald wanted us to feel this but I needed the story to be wrapped up a little more. I'm so glad to have read this. His writing is exceptional, I even loved the long sentences. It was heartbreaking without being sentimental. It has so much going for it but the ending is too much like a sudden stop (and this is one of my pet peeves!). After including such long, flowing prose the story is suddenly broken. Could there have been a sequel if Sebald hadn't died so unexpectedly? I understand, Camie, why you might feel like a 'cranky reader', I think with a fantastic conclusion the little gripes like being reminded who is speaking could have been forgotten.

I can relate, the ending is a bit off-putting. Despite the seeming lack of emotion, I was emotionally really worked up at the end of section 2/ beginning of section 3, I felt concerned for Austerlitz. But that sense of connection started to unravelled somewhere after the bath-cure. I ended up knowing a lot of factoids about Austerlitz, what he encountered, what’s being documented, yet his person doesn’t seem real.

I can relate, the ending is a bit off-putting. Despite the seeming lack of emotion, I was emotionally really worked up at the end of section 2/ beginning of section 3, I felt concerned for Austerlitz. But that sense of connection started to unravelled somewhere after the bath-cure. I ended up knowing a lot of factoids about Austerlitz, what he encountered, what’s being documented, yet his person doesn’t seem real.I agree Sebald probably intended the broken ending: Austerlitz is a broken man, people and institutions worked hard to obliterate his past. Maybe that’s the point: it’s not possible to put a human back together after you break it into pieces and catalogue it into some institutions. Even Hilary (the high school teacher, probably trained in archival research) couldn’t help unconceal Austerlitz.

For me, the really poignant thing is that Austerlitz spent his whole life driven to try to put his concealed personhood back together, even though he’s learned, determined, sensitive, resourceful... ultimately (I think) he failed. He’s doomed from the start, yet he cannot not go through with it. (Like the Nocturama raccoon with OCD!)

What do you think about having a German gentile as “witness”? Do you think it’s ... problematic? Insensitive? For a German (Sebald) to write a fictitious account of a second generation (post holocaust) Jew? Or is this story really about the narrator, a German looking at the concealment of a crime, and its effect on people today?

I agree the ending just seemed to - stop. But that didn't bother me because I never felt like I was experiencing a story anyway. I felt more like I was a witness (via the narrator) to Austerlitz's need for catharsis. And I felt that the memories and emotions Austerlitz had been experiencing were so raw that he had not had time to organize, or process, them into any kind of explanation or narrative that would have been a story. Or to put it another way, when one first suffers some kind of trauma, the mind feels stunned, and it is only over time that one starts to create, for oneself and for others, the "story" of what that trauma meant. Generally speaking of course. And so I felt like this was what I was seeing with Austerlitz - he had not yet made sense of, not yet ascribed a particular meaning to, these events. I guess it felt to me like he was in a kind of limbo, so I didn't expect an ending.

I agree the ending just seemed to - stop. But that didn't bother me because I never felt like I was experiencing a story anyway. I felt more like I was a witness (via the narrator) to Austerlitz's need for catharsis. And I felt that the memories and emotions Austerlitz had been experiencing were so raw that he had not had time to organize, or process, them into any kind of explanation or narrative that would have been a story. Or to put it another way, when one first suffers some kind of trauma, the mind feels stunned, and it is only over time that one starts to create, for oneself and for others, the "story" of what that trauma meant. Generally speaking of course. And so I felt like this was what I was seeing with Austerlitz - he had not yet made sense of, not yet ascribed a particular meaning to, these events. I guess it felt to me like he was in a kind of limbo, so I didn't expect an ending. I was surprised how much I enjoyed the book. I felt very immersed in Austerlitz's world, not just objectively but also his emotions, his memories, his sense of the layers of time (like ghosts). The book engaged me intellectually with ideas and concepts, but also viscerally and emotionally. I'll definitely re-read it later on, after which time I'm sure I'll have a slightly different take on it, as it just seems like a very rich book to me.

Short info: Today, Jan Assmann and Aleida Assmann received the very prestigious Peace Prize of the German Book Trade (the ceremony is even broadcast on national TV) for their research into the nature of memory and the (re-)construction of the past - a central theme of Sebald's, whose works, particularly On the Natural History of Destruction, have often been discussed based on the theories of the Assmanns.

Short info: Today, Jan Assmann and Aleida Assmann received the very prestigious Peace Prize of the German Book Trade (the ceremony is even broadcast on national TV) for their research into the nature of memory and the (re-)construction of the past - a central theme of Sebald's, whose works, particularly On the Natural History of Destruction, have often been discussed based on the theories of the Assmanns.

I don't remember enough about the ending to remember whether I thought it was abrupt--overall I have such positive memories of the book though that it has remained one of my favorites in my mind. I'm still tempted to re-read, though I've been following along with the comments everyone makes here.

I don't remember enough about the ending to remember whether I thought it was abrupt--overall I have such positive memories of the book though that it has remained one of my favorites in my mind. I'm still tempted to re-read, though I've been following along with the comments everyone makes here. Just one comment about the idea of a German gentile writing this story--several of the books I've read by Sebald are about how he deals with being a German in the aftermath of WWII. I think that's what makes a lot of it so poignant--he was born in 1944. Now, not for one second do I compare the troubles he would have had growing up at that time to the Holocaust, but I do imagine there would have been this enormous cloud of guilt and shame and anger and who knows what that he grew up in. I can only imagine that that would leave a heavy imprint.

One of my all-time favorite passages is from The Emigrants, where Sebald describes his feelings at moving to the city. It was "particularly auspicious that the rows of houses were interrupted here and there by patches of waste land on which stood ruined buildings, for ever since I had once visited Munich I had felt nothing to be so unambiguously linked to the word 'city' as the presence of heaps of rubble, fire scorched walls, and the gaps of windows through which one could see the vacant air."

To someone who automatically links the word 'city' to 'destruction', I can see that they are going to have a completely different viewpoint on life than I will. It struck me so forcefully at the time I read it--though I understood that people growing up in different circumstances than I would look at the world differently, I don't think I ever really 'understood' it.

So, in some ways, I think Sebald's entire oeuvre deals, at some level, with this struggle to place himself in the world he was born into.

Lia wrote: "I found myself drifting in and out of conscious focus once I get “sucked in.” I’m following the plot, my eyes moving, I’m more or less parsing what..."

Lia wrote: "I found myself drifting in and out of conscious focus once I get “sucked in.” I’m following the plot, my eyes moving, I’m more or less parsing what..."Lia you describe exactly my experience with this book. It's like traveling, like a road trip with the most erudite companion imaginable, someone who makes me really see things anew. Reading this novel reminds me of what it was like to watch the film My Dinner with Andre for the first time. Austerlitz is a lot deeper than that movie's message, but there is the same willingness on Sebald's part to let his magnificent imagination combine with his deep knowledge of history, and to let the conversation go where it will.

Then as you say Lia the narrative comes to these touchstone images that bring the read sharply into focus, which seem to happen exactly when I as a reader may have drifted too far and lost my concentration. One of my favorites: Observations re: a moth on the wall. Wonderful.

Lark wrote: "It's like traveling, like a road trip with the most erudite companion imaginable, someone who makes me really see things anew. Reading this novel reminds me of what it was like to watch the film My Dinner with Andre for the first time..."

Lark wrote: "It's like traveling, like a road trip with the most erudite companion imaginable, someone who makes me really see things anew. Reading this novel reminds me of what it was like to watch the film My Dinner with Andre for the first time..."YES! Definitely, I think my biggest “take away” is how I can be more sensitive to what I’m seeing when I’m travelling, when I’m looking at buildings from different eras, when I’m visiting libraries, archives, museums. You can passively join a commercial tour and “merely look at” pretty facade, or you can try to understand, imagine, the kind of human activities, stories, tragedies, that these artifacts “witnessed.” Austerlitz demanded the buildings to bear witness, to feel for him, to remember what he himself cannot:

when I passed through Pilsen with the children’s transport in the summer of 1939, but the idea, ridiculous in itself, that this cast-iron column, which with its scaly surface seemed almost to approach the nature of a living being, might remember me and was, if I may so put it, said Austerlitz, a witness to what I could no longer recollect for myself.

It sounded almost as though Sebald is preaching a kind of moral imperative for us to fight against the institutional will to forget, to conceal, and to witness, to really see, to remember.

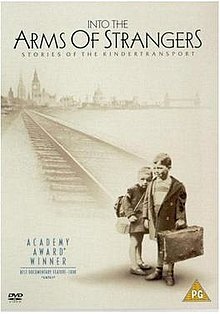

Have you seen the documentary, Into the Arms of Strangers

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Into_...

Apparently it came out around the same time as Sebald’s publication of Austerlitz. (I haven’t seen it myself, but heard about it.)

Bryan wrote: "in some ways, I think Sebald's entire oeuvre deals, at some level, with this struggle to place himself in the world he was born into..."

Bryan wrote: "in some ways, I think Sebald's entire oeuvre deals, at some level, with this struggle to place himself in the world he was born into..."Thanks Bryan. Do you think reading Sebald’s other novels affect how you interpret Austerlitz?

I’m asking as a (almost) Ishiguro completist, I know reading his other novels changed how I interpret individual novels. And I feel like Sebald’s style is somewhat similar to Ishiguro’s — especially his manipulation of memories and recalls. I have a feeling that I will have to read more of Sebald’s works to appreciate any individual novel.

Cath wrote: "I felt very immersed in Austerlitz's world, not just objectively but also his emotions, his memories, his sense of the layers of time (like ghosts). The book engaged me intellectually with ideas and concepts, but also viscerally and emotionally. I'll definitely re-read it later on..."

Cath wrote: "I felt very immersed in Austerlitz's world, not just objectively but also his emotions, his memories, his sense of the layers of time (like ghosts). The book engaged me intellectually with ideas and concepts, but also viscerally and emotionally. I'll definitely re-read it later on..."I agree. Apparently a critic described Sebald as writing like an angel (not a pretty image given the broken angel graveyard photos we have in Austerlitz), and then another critic parodied that and said Sebald writes like a ghost, and I thought, YES! THAT’S EXACTLY RIGHT!

Do you think you will want to read Sebald’s other novels after Austerlitz? (I know I do!)

Lia wrote: "Thanks Bryan. Do you think reading Sebald’s other novels affect how you interpret Austerlitz?..."

Lia wrote: "Thanks Bryan. Do you think reading Sebald’s other novels affect how you interpret Austerlitz?..."No doubt they do...though I'm not sure in what way. I read The Emigrants first, and then a posthumous collection called Campo Santo. After that, I kind of had my ear to the ground as far as things being written about Sebald, and how I understood his work started to cohere into how I perceive it today. I went on to read Austerlitz, Vertigo and The Rings of Saturn (of which there is a rather contemplative movie filmed about, completed after Sebald was dead, that used to be available on Netflix).

If someone were wondering which of his to read after Austerlitz, I think I would probably suggest The Emigrants, though many consider The Rings of Saturn to be his masterpiece. Although Campo Santo was unfinished at Sebald's death, the prose sections have that same soothing effect on me as his longer pieces do. The critical sections, which make up the second half, seem like a mixed bag to me.

I found the ending very disconcerting. After hearing about Austerlitz struggle with his identity, his trying to find out information about his parents, his bouts of depression and hospitalization, it was distressing to just leave him and return to the narrator for that abrupt ending. I did enjoy prose, at least until the last 30 or so pages when I lost any feeling of connection to what was happening. I very much disliked the layout of the book, especially when all I saw was unbroken text, i.e., no paragraphs and no pictures.

I found the ending very disconcerting. After hearing about Austerlitz struggle with his identity, his trying to find out information about his parents, his bouts of depression and hospitalization, it was distressing to just leave him and return to the narrator for that abrupt ending. I did enjoy prose, at least until the last 30 or so pages when I lost any feeling of connection to what was happening. I very much disliked the layout of the book, especially when all I saw was unbroken text, i.e., no paragraphs and no pictures.

LindaJ^ wrote: " I very much disliked the layout of the book, especially when all I saw was unbroken text, i.e., no paragraphs and no pictures...."

LindaJ^ wrote: " I very much disliked the layout of the book, especially when all I saw was unbroken text, i.e., no paragraphs and no pictures...."I assume you mean the last 30 pages, since you said "no pictures?"

I entertained the idea that we are all the narrator -- you know how Austerlitz gave him all his photos, and that's all that is left of Austerlitz? I feel a bit like we're given a "flattened," no hierarchy, inhuman, unsorted archive of artifacts, fragments, mixed media, and we as meaning-seeking individuals have the obligation to make sense of the mess, to bear witness, to "shine a light" on a collection that is otherwise mere inanimate objects. If we don't do that, Austerlitz, and countless others who suffered horrible fate, and that chunk of history being deliberately covered up, will be forgotten.

Maybe that's why there's minimal (as in no) organization, paragraph, page break, captions... here's what they gathered, we have to make sense of it.

That is, I agree there's something unsettling or unpleasant about the way the book is structured (or not structured,) and something unsatisfying about the ending, or even the characterization of Austerlitz; but I like to imagine that too is intentional, and is part of the message.

I have no doubt it was all intentional. The lack of paragraphs, however, was, for me, a hinderance to becoming invested in the book. It took away from the beauty of the prose and just made it hard for me to read. Perhaps the manufacturers of e-books can include a function that allows one to indent and make paragraphs - how different can adding indents be to changing the font size and paragraph spacing?

I have no doubt it was all intentional. The lack of paragraphs, however, was, for me, a hinderance to becoming invested in the book. It took away from the beauty of the prose and just made it hard for me to read. Perhaps the manufacturers of e-books can include a function that allows one to indent and make paragraphs - how different can adding indents be to changing the font size and paragraph spacing?

I confess I read it on a tablet, and converted the ebook to a PDF for stylus margin notes. Toggling to thumbnails mode to see the overall "layout" and the orders of the images etc really helps. When I'm reading it makes no difference to me, but when I pause and try to process what I've read and seen so far, that really helps me visualize the flow.

I confess I read it on a tablet, and converted the ebook to a PDF for stylus margin notes. Toggling to thumbnails mode to see the overall "layout" and the orders of the images etc really helps. When I'm reading it makes no difference to me, but when I pause and try to process what I've read and seen so far, that really helps me visualize the flow.

Camie wrote: "I liked the book ok. It is set up well from the start. We know these men have met, and that Austerlitz is largely the one reminiscing here. Quite early on I started to notice how often the words " ..."

Camie wrote: "I liked the book ok. It is set up well from the start. We know these men have met, and that Austerlitz is largely the one reminiscing here. Quite early on I started to notice how often the words " ..."Yes, I noticed it too, and it began to annoy me. I don't think it's a defect but is meant to remind us of the narrator, who acts as a kind of filter. Otherwise, if Austerlitz were addressing us directly, I imagine the tone would be much more emotional and less controlled. Lia and I recently discussed this during the first segment.

I too was disappointed by the last 30 or so pages. I don't mind the abrupt end, and actually love Lia's idea that the responsibility is put on us to make sense of this "archive." I just lost my connection with the story, kept drifting off as someone said above, and it took me forever to get through those pages. I was hoping for one more emotional punch, like the Vera and Library sections.

I too was disappointed by the last 30 or so pages. I don't mind the abrupt end, and actually love Lia's idea that the responsibility is put on us to make sense of this "archive." I just lost my connection with the story, kept drifting off as someone said above, and it took me forever to get through those pages. I was hoping for one more emotional punch, like the Vera and Library sections. Lark, I'm so glad you brought up My Dinner With André. (I'm always glad when someone brings it up!) Yes, this is much deeper, but it is similar in having a unique narrative and in leaving you off-balance and knowing there is so much more to learn.

I understand what Carrie is saying about the repetition, but as someone who tries to write who couldn't stop thinking how technically difficult this would be to pull off, every time I hit a "said Austerlitz" it was just a reminder to me of how brilliantly smooth the sentences read.

I like the interpretation that Sebald writes this to deal with the guilt he was born into. It's sort of like it's understandable that Austerlitz' subconscious forced his memories into repression, but there is no excuse for the rest of us.

Oh, and ghostly--yes, yes, yes!

This was my second read of Austerlitz. The first was some time ago, probably soon after it was published. I had read other books by Sebald, all but Vertigo actually, but I must say this second reading was very, very powerful. I too think it is meant to be unsettling, that we are meant to share in the narrator's guilt -- guilt for having forgotten the horrors of the holocaust. How could Austerlitz possibly ever recover from his past? By recovering it in the more literal sense! But of course there is no closure -- what a ridiculous notion. There is only forgetting. It is a haunting book, so the metaphor of the ghost is apt. I will read it again, but now I will return to Sebald's nonfiction writing.

This was my second read of Austerlitz. The first was some time ago, probably soon after it was published. I had read other books by Sebald, all but Vertigo actually, but I must say this second reading was very, very powerful. I too think it is meant to be unsettling, that we are meant to share in the narrator's guilt -- guilt for having forgotten the horrors of the holocaust. How could Austerlitz possibly ever recover from his past? By recovering it in the more literal sense! But of course there is no closure -- what a ridiculous notion. There is only forgetting. It is a haunting book, so the metaphor of the ghost is apt. I will read it again, but now I will return to Sebald's nonfiction writing.I was also reminded of Patrick Modiano, esp. Dora Bruder, creative nonfiction, but equally haunting.

Thanks everyone for your insightful comments. The group read enriches the reading experience immensely.

Elaine wrote: "How could Austerlitz possibly ever recover from his past? By recovering it in the more literal sense! But of course there is no closure -- what a ridiculous notion. There is only forgetting...."

Elaine wrote: "How could Austerlitz possibly ever recover from his past? By recovering it in the more literal sense! But of course there is no closure -- what a ridiculous notion. There is only forgetting...."My earliest childhood memory is from when I was not quite two years old; I don't think it's "normal" for Austerlitz to "forget" everything of his first 4 years. Obviously he dealt with the extreme trauma by suppressing it, but then perhaps the narrator and his nation is also coping with their own trauma by suppressing and forgetting. I'm not saying Austerlitz is blameworthy, but I do wonder if Austerlitz blames himself, or if he also feels guilty for forgetting somehow.

I want to read more books by Sebald as well. For some reasons I expected this to be experimental and difficult to read, and it is experimental in the sense that it breaks all the genre / media boundaries, but it's also very accessible.

Thanks for joining us, everyone. This is my first time leading anything and I was kind of nervous about it, but your participations and comments made it a blast! I think I got a lot more out of the book because I have a chance to discuss it with you all.

Thanks for leading the discussion, Lia. I've mostly been lurking, but found it a very engaging series of threads that has caused me to think about the book in ways I wouldn't otherwise have done on my own. Definitely want to read more Sebald after this one.

Thanks very much for leading this one Lia - it has been very interesting. Sorry I didn't find time for a re-read or contribute very much.

Thanks Hugh and Marc, even though you weren’t able to participate frequently, I appreciate all the helps I got from you guys.

Thanks Hugh and Marc, even though you weren’t able to participate frequently, I appreciate all the helps I got from you guys.

Well, it looks like the heart of the novel is here in the latter pages, and in it I found another one of Sebald's most poignant moments. Vera is explaining to Austerlitz about the "mysterious quality peculiar to photographs," Sebald writes of these "such photographs"

Well, it looks like the heart of the novel is here in the latter pages, and in it I found another one of Sebald's most poignant moments. Vera is explaining to Austerlitz about the "mysterious quality peculiar to photographs," Sebald writes of these "such photographs"One has the impression, she said, of something stirring in them, as if one caught small sighs of despair, gémissements de désespoir was her expression, said Austerlitz, as if the pictures had a memory of their own and remembered us, remembered the roles that we, the survivors, and those no longer among us had played in our former lives (182-83).I found it to be powerful insight, and not just for the survivors of one of the world's most egregious atrocities , but for those of us who have no ties to this particular history. It reminded me of the spread of fascism, that it didn't spread readily because of those who believed in its message; but, spread because of those who turned a blind a eye to it, those who watched the violence reach its various manifestations and remained silent...those who watched: their friends' families being separated, coworkers, common acquaintances, and strangers, being treated with cruelty in public, and did nothing to help. I took this section to heart, and while a few of you almost cried, I did cry; because the day I turned to the last page of Sebald's "Austerlitz," it was actually October 27, 2018. What’s happening, is it Sebald’s nightmare coming to life...Is the world forgetting?

This book, to me, was about a man who was forever riddled by the void left in his life from having been a refugee in a country since early childhood and surrounded by people and places that were foreign to him, which further enhanced his need to understand the ties that bind him to this world. Well, he could have had just this when when Dafydd asked his teacher Mr. Penrith-Smith what the name Austerlitz meant, right? Instead of uplifting the kid with cultural heritage, telling him the name is of Jewish descent, which is what he was seeking, he reduces him to a name and date of a battle…an event…a thing…an image, like the ones in this book. Thus begins the story of Austerlitz, wandering through old cobblestoned paths, in cities of old and new, walking among the ghosts of his past.

Throughout this novel, Austerlitz has been plagued by the presence of the dead moving about around him; looking off into the distance while in Terezín, he can see what appeared to him as a Jewish ghetto full of people. But, this clearly isn’t the case, is it? It’s difficult to distinguish between the dream-like narrative and what must have been Austerlitz’s reality that’s anything but a dream, instead a nightmare. What has surfaced, or what has been surfacing in Austerlitz, the sadness and foreboding that has been prevalent in the narrative since the beginning read to be guilt…the guilt from those who lived before, who died for him, who saved him from a similar fate-it weighs heavy on his conscience. I think finding his roots and understanding his heritage, it was a means to save himself from utter despair; but mostly, a means to save his parents from the same outcome as many…forgotten. What transpires in these last few pages is best summarized by James Wood, who wrote the introduction to the copy I read.

Jacques Austerlitz is joined by his name to these ruins: and again, at the end of the book, as at the beginning, he threatens to become simply part of the rubble of history, a thing, a depository of facts and dates, not a human being. And throughout the novel, present but not ever spoken, never written-it is the most beautiful act of Sebald’s withholding-is the other historical name that shadows the name Austerlitz, the name that begins and ends with the same letters, the name which we sometimes misread Austerlitz as, the place that Agáta Austerlitz was almost certainly ‘sent east’ to in 1944, and the place that Maximilian Aychenwald was almost certainly sent to from the French camp in Gurs, in 1942: Auschwitz.(XVIII-XIX)Although changed in the end, Austerlitz, after learning what he has yearned to know about his family history, is no more put together, complete a man, than he was in his younger days, I thought. Instead, he’s a compilation of a shattered history (Kathleen’s review), a fuzzy image with graying periphery, like the many pictures he described in the novel. I think about it this way, ever put together a broken glass bowl? It can be done, right? Imperfections visible, integrity of the bowl still intact. But, have you ever put together the remains of a shattered glass bowl? Yeah. It too can be done, but what does that final product resemble?

I found it odd rating this book with gold stars. Smh. Yet, I gave it 5 shining ones.

Lia, you were a perfect moderator. I loved how you presented the threads and drew from other novels to better understand aspects of this one. I hate that I missed out, and genuinely apologize to you for my absence. I hope to read with you again in the near future.

To you Kathleen, well, I love reading with you in general; and, I hate that I missed out on this discussion with you. However, even now, at this point, so many months later, you still indulge me in conversation...I am beyond grateful. You're one of the best reading buddies.

Ami, you not being here was our loss, but you fixed that by coming back with these fantastic comments!

Ami, you not being here was our loss, but you fixed that by coming back with these fantastic comments!I think you definitely found the heart of the novel. Those sighs in the pictures--that is what we hear in that cover! And the timing of when you finished the novel is a tragedy in itself, but an important reminder that the need to tell these stories goes on.

And I love your comparison to the glass bowl because what comes to mind is how when something like that breaks, we are often so sad and desperate to bring it back to life. It can never be the same, but maybe sometimes the light hits the cracks in the glass and creates a beauty of its own?

ICYMI. This popped up in my newsfeed, today.

ICYMI. This popped up in my newsfeed, today.Holocaust Survivors Brought to the Lake District as Children Gather in Prague

1945: This picture shows a group of Holocaust survivors known as the Windermere Boys, after the beauty spot in the Lake District where they were taken after escaping the horrors of World War II. They are posing in Prague's Old Town Square in what was then Czechoslovakia, in front of a memorial to 15th-century religious reformer Jan Hus

2019: The last eight survivors return to Prague with 200 relatives from all over the world, 74 years after they were liberated from Nazi camps in Czechoslovakia. Most of them settled elsewhere in the UK but they meet once a year. The group is also planning a memorial event to mark the 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in 2020

Front and centre: The survivors from Terezin concentration camp - known in German as Theresienstadt - stand with their families in front of the Hus memorial in Prague as they recreate the 74-year-old picture. Left to right: Lilian Friedman, Mala Tribich (sister of Sir Ben Helfgott), Sir Ben Helfgott, Leslie Kleinman (in pale raincoat), Sam Freiman on mobility scooter with white hat on, Sam Laskier, Icek Alterman and Arek Hersh

Article for further reading may be found here

For, Austerlitz...

Kathleen wrote: "Ami, you not being here was our loss, but you fixed that by coming back with these fantastic comments!

Kathleen wrote: "Ami, you not being here was our loss, but you fixed that by coming back with these fantastic comments!I think you definitely found the heart of the novel. Those sighs in the pictures--that is wha..."

It can never be the same, but maybe sometimes the light hits the cracks in the glass and creates a beauty of its own?

Ahhh, I like this!

Thank you. :)

Books mentioned in this topic

My Dinner With André (other topics)On the Natural History of Destruction (other topics)

Austerlitz (other topics)

The Unconsoled (other topics)

When We Were Orphans (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Jan Assmann (other topics)Aleida Assmann (other topics)