The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Nicholas Nickleby

Nicholas Nickleby

>

NN, Chp. 51-55

Chapter 52 continues where the previous chapter stopped, and we find Nicholas arrest his course and take his counsel with Newman lest he should be taken for and as a thief. It soon becomes obvious that it is quite difficult to come up with a good way of dealing with the problem because the Cheeryble brothers are both on a business trip to Europe and it will take days before they can be in London. Nicholas also feels qualms about acquainting Frank Cheeryble with the matter because his uncles had chosen not to do so, and what right has he, Nicholas, to ignore that decision. You see that in this matter, Nicholas is ready enough to respect the reservations of people older than he, but maybe this is also because it happens to coincide with his own rather jealous feelings about Frank as far as Madeline is concerned. He says

What do you think? Would Nicholas really react the same way if he were completely indifferent to Madeline’s charms? Or maybe, it is the damsel-in-distress-situation that increases his ardent love even more? And is it responsible not to confer with Frank on this matter?

It is much to Newman’s merit that he was able to dissuade Nicholas from doing anything rash and stupid – for how long, though? – and at the same time never to give up hope. With Newman’s aid, Nicholas finally comes to the conclusion that it might be advisable to see Madeline and talk with her once more. Newman then delivers quite a nice speech about how necessary hope is for a living creature, and maybe he is speaking from his own experience?

When Nicholas has left him, Newman looks after him, ruminating and saying:

Is this the author himself speaking through one of his characters, trying to justify one trait in his protagonist that might not go down too well with all of his readers? Is there any chance of Nicholas learning to curb his anger and be less irascible? And what do you yourselves think of Nicholas at his point?

Newman, on his way home, then makes us fall in with the Kenwigses again, who have some more of their genteel problems – this time connected with the invitation to an excursion on board a steamer Morleena has received. Now the whole family, especially Mrs. Kenwigs, is busy preparing the young girl for that social event, and again we get the idea that certain people pay a very high degree of attention to social distinctions and status symbols. Do you see any parallel in that connection between the Kenwigses and Mr. Bray? Both prepare their daughters for a situation that may increase the status of the family and of the daughter, both are keenly aware that they maybe don’t have the position in society they were really and truly destined for, and even the Kenwigs family is not free from mercenary thoughts. – Where do you see the differences between these two families?

Accompanying Morleena to the hairdresser, Noggs witnesses yet another instance of social pretentiousness, when the hairdresser objects to serving a coal-heaver:

Is this a mere frolic of Dickens’s imagination, or can this be seen in connection with some pervading motif of the novel? Are there other examples of pretentiousness, maybe also with regard to furthering one’s business connections?

In the barber’s shop, Newman (and we) also meet another old acquaintance, namely Uncle Lillyvick, who has eaten humble pie in the meantime, as soon comes out when he accompanies Morleena and Newman to the family circle he not long ago spurned so harshly. Uncle Lillyvick confesses that his wife Henrietta has eloped with a half-pay captain, not without taking some household valuables with her. As the bulk of the uncle’s possessions seems still intact, though, and as he shows true repentance and interest in the children, particularly the new-born, he is soon forgiven by the Kenwigses, of course, with the understanding that Henrietta Lillyvick be exempt from any lenient feelings bestowed upon him, and him alone.

This may have been the last we will see of the Kenwigs, after even the illustrious Crummles troupe has bid us farewell. The novel is drawing to a close, and so certain minor characters will have to disappear. – Did you enjoy the Kenwigses and their dramatic family story? What did it contribute to the overall structure of the novel?

”[…] ‘that in this effort I am influenced by no selfish or personal considerations, but by pity for her and detestation and abhorrence of this heartless scheme; and that I would do the same were there twenty rivals in the field, and I the last and least favoured of them all.’”

What do you think? Would Nicholas really react the same way if he were completely indifferent to Madeline’s charms? Or maybe, it is the damsel-in-distress-situation that increases his ardent love even more? And is it responsible not to confer with Frank on this matter?

It is much to Newman’s merit that he was able to dissuade Nicholas from doing anything rash and stupid – for how long, though? – and at the same time never to give up hope. With Newman’s aid, Nicholas finally comes to the conclusion that it might be advisable to see Madeline and talk with her once more. Newman then delivers quite a nice speech about how necessary hope is for a living creature, and maybe he is speaking from his own experience?

When Nicholas has left him, Newman looks after him, ruminating and saying:

”’He’s a violent youth at times,’ said Newman, looking after him; ‘and yet I like him for it. […]’”

Is this the author himself speaking through one of his characters, trying to justify one trait in his protagonist that might not go down too well with all of his readers? Is there any chance of Nicholas learning to curb his anger and be less irascible? And what do you yourselves think of Nicholas at his point?

Newman, on his way home, then makes us fall in with the Kenwigses again, who have some more of their genteel problems – this time connected with the invitation to an excursion on board a steamer Morleena has received. Now the whole family, especially Mrs. Kenwigs, is busy preparing the young girl for that social event, and again we get the idea that certain people pay a very high degree of attention to social distinctions and status symbols. Do you see any parallel in that connection between the Kenwigses and Mr. Bray? Both prepare their daughters for a situation that may increase the status of the family and of the daughter, both are keenly aware that they maybe don’t have the position in society they were really and truly destined for, and even the Kenwigs family is not free from mercenary thoughts. – Where do you see the differences between these two families?

Accompanying Morleena to the hairdresser, Noggs witnesses yet another instance of social pretentiousness, when the hairdresser objects to serving a coal-heaver:

”’It’s necessary to draw the line somewheres my fine feller,’ replied the principal. ‘We draw the line there. We can’t go beyond bakers. If we was to get any lower than bakers our customers would desert us, and we might shut up shop. You must try some other establishment, sir. We couldn't do it here.’”

Is this a mere frolic of Dickens’s imagination, or can this be seen in connection with some pervading motif of the novel? Are there other examples of pretentiousness, maybe also with regard to furthering one’s business connections?

In the barber’s shop, Newman (and we) also meet another old acquaintance, namely Uncle Lillyvick, who has eaten humble pie in the meantime, as soon comes out when he accompanies Morleena and Newman to the family circle he not long ago spurned so harshly. Uncle Lillyvick confesses that his wife Henrietta has eloped with a half-pay captain, not without taking some household valuables with her. As the bulk of the uncle’s possessions seems still intact, though, and as he shows true repentance and interest in the children, particularly the new-born, he is soon forgiven by the Kenwigses, of course, with the understanding that Henrietta Lillyvick be exempt from any lenient feelings bestowed upon him, and him alone.

This may have been the last we will see of the Kenwigs, after even the illustrious Crummles troupe has bid us farewell. The novel is drawing to a close, and so certain minor characters will have to disappear. – Did you enjoy the Kenwigses and their dramatic family story? What did it contribute to the overall structure of the novel?

Chapter 53 takes us back to the Gride-Nickleby plot, and to our hero’s attempts at saving his beloved Madeline. The next morning, Nicholas betakes himself to the Bray’s lodgings, where he finds the front door ajar – a promising sign of luck, or just another of the many coincidences? – and simply enters the house. Now we get the following description of Madeline Bray:

I underlined some passages that struck me particularly, and I’d really like to know what you think of this description and the underlying assumptions we are supposed to make about Madeline. What does this description tell us about Dickens and his idea of perfect womanhood – if this passage allows us to draw any conclusions as to this, at all?

Madeline’s father tries to make the impression as though everything was quite normal, whereas his pretences are belied by the fact that Madeline has forgotten to water the flowers and to uncover the bird’s cage – a detail that might seem interesting in connection with the story of the little invalid boy told by Tom Linkinwater.

Mr. Bray quickly assumes his masterful air and bearing when he sees Nicholas arrive, bringing home to his visitor the idea that his daughter is no longer, and has, in fact, never been dependent on business connections with him and his employers, whom he decries as “purse-proud” merchants, implying that they are mere upstarts, favoured by fortune to a certain degree, whereas he, Mr. Bray, is a true gentleman, by birth (which is, by the by, also a sort of fortune, isn’t it?). His whole way of treating Nicholas is meant to underline the social distance between them, but maybe, there is also something more to it … Maybe, by flying into a kind of temper, Mr. Bray wants to persuade himself that he has done his daughter a favour when he struck the bargain with Arthur, because he helped her back to the means of living the way she is supposed to live according to her social status – and helping himself in that way, too, of course, but that’s neither here nor there, is it, really, when you come to think of it …

Mr. Bray’s insults finally goad Nicholas into indirectly reproaching the father of sacrificing his daughter for his own needs, but at this point, Madeline sides with his father, imploring Nicholas to think and consider that her father is very ill. From that point, the conversation does not take a very promising course, even when – through the interference of the maid – Nicholas can get a private interview with Madeline. Speaking directly of the marriage here, and entreating her to consider what she is doing with her life, he still does not manage to make Madeline err on the course of what she perceives to be her duty. She bids him give her thanks to the Cheeryble brothers – in whose name, of course, he is urging his case – and tell them that come what may, she will do her duty by her father. What can be said for Madeline in this conversation is that she certainly matches Nicholas when it comes to using highly dramatic language which would do honour to any stage provided that it specialised in melodrama.

The scene then changes from a despondent Nicholas to the bridegroom Arthur Gride, who is torn between regrets of having invited Ralph into his plot at all and the knowledge that without him, he would probably never have succeeded in making Mr. Bray accept his offer of himself as an in-law. We also see Arthur going through some mysterious business papers, which he has taken from his chest and which engross him so much that it takes quite some time before he notices that there is somebody else in the room. Somebody who has been let in by Peg Sliderskew.

We could have depended upon Nicholas doing something rash, couldn’t we? The young stranger is none else but him, and in a desperate attempt at saving the day after all, Nicholas now asks Gride to name his price for calling the wedding off. It must be added that, wisely, Nicholas refrains from giving his name and that he but darkly hints at being connected with people who have the means of paying any price he names. He may not exactly be improving his position by adding that he does not appeal to Arthur’s nobler and better feelings because he knows that he does not have any. This if, of course, true but there are truths that should not be uttered when you want to bring somebody round. Arthur immediately takes Nicholas for a thwarted admirer and suitor of Madeline’s and does his best to rouse the young man’s wrath by conjuring up images of how he is going to enjoy the charms of his young wife and how both of them, Arthur and Madeline, will laugh when they think of poor Nicholas. Why do you think Arthur insists so much on these details? Why does the narrator bring them up? Had Arthur gone on in this vein much longer, Nicholas would probably once again manhandle his host – but Arthur rids himself by going to the window and crying for help, implying that he would even hurt himself, drawing blood, and pin it on Nicholas. Our protagonist sees that all his efforts – he is not too good at diplomacy, on the whole – are of no avail, and so he withdraws as quickly as he came.

What is the effect Nicholas will produce with this messed-up interference? What did he change with regard to Madeline’s position as Arthur’s bride? And last not least, what other options are there for Nicholas and his friends to prevent the marriage?

”There are no words which can express, nothing with which can be compared, the perfect pallor, the clear transparent cold ghastly whiteness, of the beautiful face which turned towards him when he entered. Her hair was a rich deep brown, but shading that face, and straying upon a neck that rivalled it in whiteness, it seemed by the strong contrast raven black. Something of wildness and restlessness there was in the dark eye, but there was the same patient look, the same expression of gentle mournfulness which he well remembered, and no trace of a single tear. Most beautiful—more beautiful perhaps in appearance than ever—there was something in her face which quite unmanned him, and appeared far more touching than the wildest agony of grief. It was not merely calm and composed, but fixed and rigid, as though the violent effort which had summoned that composure beneath her father’s eye, while it mastered all other thoughts, had prevented even the momentary expression they had communicated to the features from subsiding, and had fastened it there as an evidence of its triumph.”

I underlined some passages that struck me particularly, and I’d really like to know what you think of this description and the underlying assumptions we are supposed to make about Madeline. What does this description tell us about Dickens and his idea of perfect womanhood – if this passage allows us to draw any conclusions as to this, at all?

Madeline’s father tries to make the impression as though everything was quite normal, whereas his pretences are belied by the fact that Madeline has forgotten to water the flowers and to uncover the bird’s cage – a detail that might seem interesting in connection with the story of the little invalid boy told by Tom Linkinwater.

Mr. Bray quickly assumes his masterful air and bearing when he sees Nicholas arrive, bringing home to his visitor the idea that his daughter is no longer, and has, in fact, never been dependent on business connections with him and his employers, whom he decries as “purse-proud” merchants, implying that they are mere upstarts, favoured by fortune to a certain degree, whereas he, Mr. Bray, is a true gentleman, by birth (which is, by the by, also a sort of fortune, isn’t it?). His whole way of treating Nicholas is meant to underline the social distance between them, but maybe, there is also something more to it … Maybe, by flying into a kind of temper, Mr. Bray wants to persuade himself that he has done his daughter a favour when he struck the bargain with Arthur, because he helped her back to the means of living the way she is supposed to live according to her social status – and helping himself in that way, too, of course, but that’s neither here nor there, is it, really, when you come to think of it …

Mr. Bray’s insults finally goad Nicholas into indirectly reproaching the father of sacrificing his daughter for his own needs, but at this point, Madeline sides with his father, imploring Nicholas to think and consider that her father is very ill. From that point, the conversation does not take a very promising course, even when – through the interference of the maid – Nicholas can get a private interview with Madeline. Speaking directly of the marriage here, and entreating her to consider what she is doing with her life, he still does not manage to make Madeline err on the course of what she perceives to be her duty. She bids him give her thanks to the Cheeryble brothers – in whose name, of course, he is urging his case – and tell them that come what may, she will do her duty by her father. What can be said for Madeline in this conversation is that she certainly matches Nicholas when it comes to using highly dramatic language which would do honour to any stage provided that it specialised in melodrama.

The scene then changes from a despondent Nicholas to the bridegroom Arthur Gride, who is torn between regrets of having invited Ralph into his plot at all and the knowledge that without him, he would probably never have succeeded in making Mr. Bray accept his offer of himself as an in-law. We also see Arthur going through some mysterious business papers, which he has taken from his chest and which engross him so much that it takes quite some time before he notices that there is somebody else in the room. Somebody who has been let in by Peg Sliderskew.

We could have depended upon Nicholas doing something rash, couldn’t we? The young stranger is none else but him, and in a desperate attempt at saving the day after all, Nicholas now asks Gride to name his price for calling the wedding off. It must be added that, wisely, Nicholas refrains from giving his name and that he but darkly hints at being connected with people who have the means of paying any price he names. He may not exactly be improving his position by adding that he does not appeal to Arthur’s nobler and better feelings because he knows that he does not have any. This if, of course, true but there are truths that should not be uttered when you want to bring somebody round. Arthur immediately takes Nicholas for a thwarted admirer and suitor of Madeline’s and does his best to rouse the young man’s wrath by conjuring up images of how he is going to enjoy the charms of his young wife and how both of them, Arthur and Madeline, will laugh when they think of poor Nicholas. Why do you think Arthur insists so much on these details? Why does the narrator bring them up? Had Arthur gone on in this vein much longer, Nicholas would probably once again manhandle his host – but Arthur rids himself by going to the window and crying for help, implying that he would even hurt himself, drawing blood, and pin it on Nicholas. Our protagonist sees that all his efforts – he is not too good at diplomacy, on the whole – are of no avail, and so he withdraws as quickly as he came.

What is the effect Nicholas will produce with this messed-up interference? What did he change with regard to Madeline’s position as Arthur’s bride? And last not least, what other options are there for Nicholas and his friends to prevent the marriage?

One may indeed say that our narrator has woven such a perfect web around Madeline, with Arthur as the zealous spider – there is even a reference to cobwebs and flies in Arthur’s office made by Newman in one of the preceding chapters – that there is hardly a way out. There is, however, after all, as Chapter 54 shows. But it is a very poor and disappointing one, as far as the qualities of the narration are concerned because Dickens uses the trite deus ex machina solution.

Before the narrator sends Ralph and Arthur to Mr. Bray’s rooms, he treats us to one more altercation between Arthur and Peg Sliderskew after which the old lady vents her mind to herself, saying that she has always been kept content with little viands, little household money and small wages because Gride pointed out to her that he would die a childless bachelor, and now her master has changed his mind, passing over Peg. From what she says, one might easily imagine that she would see herself entitled to be Arthur’s bride. Is there really this kind of jealousy at the bottom of Peg’s disgruntlement? And, what kind of life might she have led in Arthur’s services? Could she have turned out a better person, had she had a better master? Arthur, of course, shows no gratitude and deliberates on getting rid of Peg sooner or later after the wedding. Is Arthur all-too sure of Peg and her deafness? Might there not be a surprise in the wings of this story for him?

The arrival of the two men at the bride’s house is rather dismal: “There was nobody to receive or welcome them; and they stole upstairs into the usual sitting-room, more like two burglars than the bridegroom and his friend.” The bride is still waiting upstairs, and the two merry-makers, or married-makers, firstly run into the father, who assures them that “[s]he may be safely trusted now” and that he has “been talking to her this morning”. That all sounds very propitious. However, at the sight of the decrepit bridegroom, whose ugliness may not so much be a matter of age than of avarice, the father seems to hesitate and waver in his design to go through with it all. Here, Ralph shows his utmost skill in cynicism in that he points out to Mr. Bray that Gride’s age is rather in his favour because after all, this bodes well for an early widowhood of Madeline’s and leave her a rich woman very soon.

His doubts may make Mr. Bray seem an ambivalent character, but the narrator explains them to us this way:

This is definitely a sound observation of human nature, and I also know lots of people who “feel themselves […] quite virtuous and moral” by doing what they suppose to be good deeds with the money of other people (usually tax-payers), and so the narrator may have a point there. What do you think about his putting these observations into the text? Is he too obtrusive? Should he have left it to the reader to figure out the real motives behind Mr. Bray’s words and actions?

Mr. Bray now goes upstairs to fetch the lucky bride but before he does so, he tells the two men about a dream he had the night before – a dream which clearly foreshadows what is to come now. One should also mark that Ralph, two minutes before, congratulated Gride on not having to pay Bray’s annuity for long and having struck a good bargain. – There is many a slip betwixt the cup and the lip, and this time, it is for Arthur and Ralph to realize the truth of this saying because Mr. Bray will not return with his daughter. He dies of a fit, and sends his daughter into another one.

What do you think of this deus ex machina turn of events? Do you think it believable, or cheap? Is there any divine retribution in it, did Dickens plan it like this or was it just his last resort to escape a plot that he had crafted so well nothing else would help him find a solution? I most certainly found this sudden death of Mr. Bray very disappointing.

At the same time (a little before, to be precise), to make matters even worse (in terms of narration), the cavalry comes to the rescue: Nicholas and Kate barge into the room – Kate, being necessary as a chaperon because otherwise, Nicholas could not have taken Madeline to their house, for reasons of propriety. It is, indeed, a dramatic confrontation between Kate and her uncle, and the sister comes over as more likeable to me than the brother. Nicholas could not have known that Mr. Bray was going to die that morning, so one must ask what his intention was. Has he really come to take Madeline with him and his sister, under the very eyes of the father? What scene would have ensued then?

Before leaving, Nicholas prophesies to Ralph that he will soon be brought to heel, that he has already lost 10,000 Pounds that very day and that more defeats will follow. He then takes Madeline, who has, conveniently, fainted, with him and leaves the two old men alone, not without hurling old Arthur out of his way – finally he did lay his hands on the old man; not doing so would have been like leaving a room, pouting, without banging the door. The text talks of “Madeline’s immediate removal”, which reminded me of moving a wardrobe or some bookshelves. What do you think of the way in which Nicholas disposes over Madeline here? Is Madeline not literally the prize Nicholas “carries off” here?

Before the narrator sends Ralph and Arthur to Mr. Bray’s rooms, he treats us to one more altercation between Arthur and Peg Sliderskew after which the old lady vents her mind to herself, saying that she has always been kept content with little viands, little household money and small wages because Gride pointed out to her that he would die a childless bachelor, and now her master has changed his mind, passing over Peg. From what she says, one might easily imagine that she would see herself entitled to be Arthur’s bride. Is there really this kind of jealousy at the bottom of Peg’s disgruntlement? And, what kind of life might she have led in Arthur’s services? Could she have turned out a better person, had she had a better master? Arthur, of course, shows no gratitude and deliberates on getting rid of Peg sooner or later after the wedding. Is Arthur all-too sure of Peg and her deafness? Might there not be a surprise in the wings of this story for him?

The arrival of the two men at the bride’s house is rather dismal: “There was nobody to receive or welcome them; and they stole upstairs into the usual sitting-room, more like two burglars than the bridegroom and his friend.” The bride is still waiting upstairs, and the two merry-makers, or married-makers, firstly run into the father, who assures them that “[s]he may be safely trusted now” and that he has “been talking to her this morning”. That all sounds very propitious. However, at the sight of the decrepit bridegroom, whose ugliness may not so much be a matter of age than of avarice, the father seems to hesitate and waver in his design to go through with it all. Here, Ralph shows his utmost skill in cynicism in that he points out to Mr. Bray that Gride’s age is rather in his favour because after all, this bodes well for an early widowhood of Madeline’s and leave her a rich woman very soon.

His doubts may make Mr. Bray seem an ambivalent character, but the narrator explains them to us this way:

”When men are about to commit or to sanction the commission of some injustice, it is not at all uncommon for them to express pity for the object either of that or some parallel proceeding, and to feel themselves at the time quite virtuous and moral, and immensely superior to those who express no pity at all. This is a kind of upholding of faith above works, and is very comfortable.”

This is definitely a sound observation of human nature, and I also know lots of people who “feel themselves […] quite virtuous and moral” by doing what they suppose to be good deeds with the money of other people (usually tax-payers), and so the narrator may have a point there. What do you think about his putting these observations into the text? Is he too obtrusive? Should he have left it to the reader to figure out the real motives behind Mr. Bray’s words and actions?

Mr. Bray now goes upstairs to fetch the lucky bride but before he does so, he tells the two men about a dream he had the night before – a dream which clearly foreshadows what is to come now. One should also mark that Ralph, two minutes before, congratulated Gride on not having to pay Bray’s annuity for long and having struck a good bargain. – There is many a slip betwixt the cup and the lip, and this time, it is for Arthur and Ralph to realize the truth of this saying because Mr. Bray will not return with his daughter. He dies of a fit, and sends his daughter into another one.

What do you think of this deus ex machina turn of events? Do you think it believable, or cheap? Is there any divine retribution in it, did Dickens plan it like this or was it just his last resort to escape a plot that he had crafted so well nothing else would help him find a solution? I most certainly found this sudden death of Mr. Bray very disappointing.

At the same time (a little before, to be precise), to make matters even worse (in terms of narration), the cavalry comes to the rescue: Nicholas and Kate barge into the room – Kate, being necessary as a chaperon because otherwise, Nicholas could not have taken Madeline to their house, for reasons of propriety. It is, indeed, a dramatic confrontation between Kate and her uncle, and the sister comes over as more likeable to me than the brother. Nicholas could not have known that Mr. Bray was going to die that morning, so one must ask what his intention was. Has he really come to take Madeline with him and his sister, under the very eyes of the father? What scene would have ensued then?

Before leaving, Nicholas prophesies to Ralph that he will soon be brought to heel, that he has already lost 10,000 Pounds that very day and that more defeats will follow. He then takes Madeline, who has, conveniently, fainted, with him and leaves the two old men alone, not without hurling old Arthur out of his way – finally he did lay his hands on the old man; not doing so would have been like leaving a room, pouting, without banging the door. The text talks of “Madeline’s immediate removal”, which reminded me of moving a wardrobe or some bookshelves. What do you think of the way in which Nicholas disposes over Madeline here? Is Madeline not literally the prize Nicholas “carries off” here?

After all those dramatic events, we surely need a breather, and Chapter 55 mercifully provides us one, treating of “family matters” and giving Mrs. Nickleby large room to discourse on several matters, not always immediately linked with each other nor with anything else. In fact, this chapter mainly serves to summarize family developments that take place in the course of several weeks, for example Madeline’s being nursed back to health and making friends with Kate. The Cheeryble brothers, who have meanwhile returned from their business trip, have shown themselves very satisfied with the manner in which Nicholas has acted during the Bray crisis.

Another development in the Nickleby circle consists in the fact that Frank Cheeryble is apparently falling in love with Kate, which is why he comes to see the family more and more often. Mrs. Nickleby, for once, is the only person to notice this, and she encourages Frank in many different ways, which, to her, seem logical. When she talks about this development with Nicholas, though, the young man, is flabbergasted first, and then dismayed, saying that it is out of the question for Kate to accept Frank as a suitor, and he gives the following reason:

He also adds that he trusts so much in Kate’s good judgment that he knows she will feel the same way about this subject. Is Nicholas’s pride well-founded, or has he no right to interfere with his sister’s possible suitor? And if he is right, will he apply this principle to his own case, too? Remember that actually Madeline seems to be entitled to a big inheritance, and that she might, for all we know, turn out more prosperous than she seems right now.

One last point to be mentioned is a very sad one, indeed: Smike is wasting away, and there is but one solution to at least slow down this process, namely going to the countryside. Nicholas is given leave by the Cheeryble brothers in order to take Smike to Devonshire and spend some time with him. It seems as though our poor friend’s life will not last very long. If there is some mystery connected with him, or some special role assigned for him to play, time is running out.

Another development in the Nickleby circle consists in the fact that Frank Cheeryble is apparently falling in love with Kate, which is why he comes to see the family more and more often. Mrs. Nickleby, for once, is the only person to notice this, and she encourages Frank in many different ways, which, to her, seem logical. When she talks about this development with Nicholas, though, the young man, is flabbergasted first, and then dismayed, saying that it is out of the question for Kate to accept Frank as a suitor, and he gives the following reason:

”’[…] poverty should engender an honest pride, that it may not lead and tempt us to unworthy actions, and that we may preserve the self-respect which a hewer of wood and drawer of water may maintain—and does better in maintaining than a monarch his. Think what we owe to these two brothers; remember what they have done and do every day for us with a generosity and delicacy for which the devotion of our whole lives would be a most imperfect and inadequate return. What kind of return would that be which would be comprised in our permitting their nephew, their only relative, whom they regard as a son, and for whom it would be mere childishness to suppose they have not formed plans suitably adapted to the education he has had, and the fortune he will inherit—in our permitting him to marry a portionless girl so closely connected with us, that the irresistible inference must be that he was entrapped by a plot; that it was a deliberate scheme and a speculation amongst us three. […]’”

He also adds that he trusts so much in Kate’s good judgment that he knows she will feel the same way about this subject. Is Nicholas’s pride well-founded, or has he no right to interfere with his sister’s possible suitor? And if he is right, will he apply this principle to his own case, too? Remember that actually Madeline seems to be entitled to a big inheritance, and that she might, for all we know, turn out more prosperous than she seems right now.

One last point to be mentioned is a very sad one, indeed: Smike is wasting away, and there is but one solution to at least slow down this process, namely going to the countryside. Nicholas is given leave by the Cheeryble brothers in order to take Smike to Devonshire and spend some time with him. It seems as though our poor friend’s life will not last very long. If there is some mystery connected with him, or some special role assigned for him to play, time is running out.

Whew. I'm exhausted just from reading the synopses of these chapters. But before parsing them, allow me to offer a general impression. The chapter in which Lillyvick returns to the bosom of the Kenwig family helped me to crystallize something that's been niggling at me. With the farewells of the Crummles, and now this (possibly final) reemergence of the the Kenwigs, it occurs to me that they all seem like characters from different stories than the current one with Madeline, Gride, et al. It's been rather jarring having them come back onto the stage at this juncture. Of course, they're all tied together by Nicholas, but they really have no other significant intersection. That seems unusual for Dickens, and a bit of a disappointment for this reader. One might argue that it's more realistic; all of us have different segments of our lives that are compartmentalized. But it doesn't seem typical of Dickens later novels (does it?). To use a Seinfeld reference, Dickens was a master of worlds colliding. But Nick's worlds don't collide - they're like ships passing in the night. The Crummles and the Kenwigs, and even the Yorkshire contingent, seemingly have nothing to do with each other or the current cast of characters, namely the Brays and Gripe. Will Brooker be the tie that binds? I don't think so, at least not with the Crummles and Kenwigs.

Whew. I'm exhausted just from reading the synopses of these chapters. But before parsing them, allow me to offer a general impression. The chapter in which Lillyvick returns to the bosom of the Kenwig family helped me to crystallize something that's been niggling at me. With the farewells of the Crummles, and now this (possibly final) reemergence of the the Kenwigs, it occurs to me that they all seem like characters from different stories than the current one with Madeline, Gride, et al. It's been rather jarring having them come back onto the stage at this juncture. Of course, they're all tied together by Nicholas, but they really have no other significant intersection. That seems unusual for Dickens, and a bit of a disappointment for this reader. One might argue that it's more realistic; all of us have different segments of our lives that are compartmentalized. But it doesn't seem typical of Dickens later novels (does it?). To use a Seinfeld reference, Dickens was a master of worlds colliding. But Nick's worlds don't collide - they're like ships passing in the night. The Crummles and the Kenwigs, and even the Yorkshire contingent, seemingly have nothing to do with each other or the current cast of characters, namely the Brays and Gripe. Will Brooker be the tie that binds? I don't think so, at least not with the Crummles and Kenwigs. Dickens did have "worlds collide" in OT, but it was contrived and ludicrous. NN sometimes seems more Pickwickian, in that it follows Nick on seemingly unrelated adventures. Perhaps in his third novel he's trying to combine the strengths of the previous two. It is fascinating to watch his development as an author. I anxiously await the final two installments of NN to see if this observation ends up having any credence!

PS We can add Hawk and his circle, as well as the Mantalinis, to the list of separate "worlds" that don't collide with the most of the others in the book. I'd love to see a scene with Mantalini, Hawk, and Browdie interacting with one another!

Tristram wrote: "We now get to know Peg Sliderskew – “slide-or-skew”, I like that –, Mr. Gride’s servant, an old, deaf woman, who has been with him for long, long years...."

Tristram wrote: "We now get to know Peg Sliderskew – “slide-or-skew”, I like that –, Mr. Gride’s servant, an old, deaf woman, who has been with him for long, long years...."Peg Sliderskew. One of so many minor Dickens characters who steals whatever scene she's in! And brilliant of Dickens to give us these peripheral characters to inject humor into such bleak settings with characters who are almost too abhorrent to bear. Her life with Gride is abysmal, but she's taken ownership of it, and she doesn't like the idea of some little "upstart" moving in on her territory! Priceless.

Tristram wrote: "What does this description tell us about Dickens and his idea of perfect womanhood – if this passage allows us to draw any conclusions as to this, at all?..."

Tristram wrote: "What does this description tell us about Dickens and his idea of perfect womanhood – if this passage allows us to draw any conclusions as to this, at all?..."I found myself cheering for Madeline in this chapter, which surprised me a bit. She's devoted to her father to the point of idiocy, but she went into this arrangement knowing full well what it would entail, and she's not going to let some handsome stranger, regardless of his bona fides, come in and interfere. When she told Nick to back off and leave her the hell alone, I was quite proud of Madeline, even knowing that it probably wasn't going to end well for her. Remember -- this is only the second time she's ever laid eyes on him! She knows nothing of his character or intentions, regardless of his expressions of admiration for her.

As to Dickens' idea of perfect womanhood, like many of you, I'm not a fan of his perfect little woman characters. But I have to admit that as annoying and idealized as they are, all of them do seem to have an inner strength that peeks out from time to time. I think Kate and Madeline have both shown it in this novel.

Tristram wrote: "What do you think of this deus ex machina turn of events?..."

Tristram wrote: "What do you think of this deus ex machina turn of events?..."Bray's sudden death didn't bother me as much as it did you, Tristram, but I did feel cheated having not witnessed it. One would think he'd have had an altercation with someone, causing his collapse. Had this off screen death happened on a soap opera, we would have to assume that Madeline had a hand in her father's demise, only to find out later that somehow Peg Sliderskew or Newman Noggs had done the evil deed. Alas, I doubt there is any mystery here. So, the sudden death didn't bother me, but its execution (so to speak) did.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "What do you think of this deus ex machina turn of events?..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "What do you think of this deus ex machina turn of events?..."Bray's sudden death didn't bother me as much as it did you, Tristram, but I did feel cheated having not witnessed it...."

Although probably for the wrong reasons, I loved having Bray drop dead upstairs (THUMP!) right at the height of the Nicholas-Ralph histrionics. It felt straight out of a Monty Python sketch.

Tristram wrote: "By the way, what do you think of Newman constantly prying into his master’s affairs? On the one hand, Ralph’s business dealings are quite shady and dishonest, but is it not also dishonest for Newman to spy on the man who pays him?"

Tristram wrote: "By the way, what do you think of Newman constantly prying into his master’s affairs? On the one hand, Ralph’s business dealings are quite shady and dishonest, but is it not also dishonest for Newman to spy on the man who pays him?"The snooping is not professional, but I understand Newman's reasons. Ralph's dealings sometimes hurt innocent people, and Newman, having the conscience that he does, feels obligated to help and protect the innocents when he can. It's all part of his guardian angel function. The tears he shed for Kate when he spied on her begging Ralph for mercy says a lot about Newman's empathy, I think.

If Newman was snooping for selfish reasons, like to destroy or blackmail Ralph, or to make some money, that would be a different matter.

Yes, Alissa, and in a way there is nothing that Newman stands indebted for to Ralph, is there? After all, Ralph seems to have had quite in hand in Newman's downfall and now he is keeping him for a pittance as his clerk, leading him a dog's life all the time. The most important thing, however, is that Newman does not seem to spy on Ralph out of spite but simply because he is worried by all the harm his master brings on other people. That makes it more palatable to the reader and also justifies it.

Mary Lou,

I agree with you: The structure of NN is quite uneven and slipshod compared with Dickens's later novels, and it may be no coincidence that when reading the early Dickens, I feel reminded of Fielding and Smollett and their long, but often episodic novels. It is quite noticeable that Dickens still has difficulty in dealing with his vast set of characters in an adequate way, and this becomes clear by how he contrives to give each of the character circles - here the Kenwigs, the Crummles, Verisopht and Hawk - a last appearance in the novel. I like your Seinfeld reference, not just because it was a Seinfeld reference but also because in Seinfeld you often see the worlds colliding motif brought to a certain perfection, which this novel is, as yet, far from. Saying that, I wonder whether the Mantalinis will make a last appearance and when?

I agree with you: The structure of NN is quite uneven and slipshod compared with Dickens's later novels, and it may be no coincidence that when reading the early Dickens, I feel reminded of Fielding and Smollett and their long, but often episodic novels. It is quite noticeable that Dickens still has difficulty in dealing with his vast set of characters in an adequate way, and this becomes clear by how he contrives to give each of the character circles - here the Kenwigs, the Crummles, Verisopht and Hawk - a last appearance in the novel. I like your Seinfeld reference, not just because it was a Seinfeld reference but also because in Seinfeld you often see the worlds colliding motif brought to a certain perfection, which this novel is, as yet, far from. Saying that, I wonder whether the Mantalinis will make a last appearance and when?

The opening description of the house and Gride living in it is one of decay, and it is described this way to accentuate, not Gride's depravity, but Madeline's plight. There is the feel of the spider and his web about it, which Noggs makes sure we notice by emphasizing to Gride the cobwebs and dead carcasses of floating flies. This makes Nicholas all the more the hero and Ralph and Gride all the more the villains.

The opening description of the house and Gride living in it is one of decay, and it is described this way to accentuate, not Gride's depravity, but Madeline's plight. There is the feel of the spider and his web about it, which Noggs makes sure we notice by emphasizing to Gride the cobwebs and dead carcasses of floating flies. This makes Nicholas all the more the hero and Ralph and Gride all the more the villains. Describing the sound of Noggs cracking his knuckles as the sound small artillery. What a hoot. I think Noggs knows how annoying his habit is and practices it by cracking his knuckles in front of people he doesn't like, like his employer.

"Stop thief!" Noggs shouting to stop Nicholas from running off. Reminds me of OT. Must have been a shout used regularly to solicit help from anyone and everyone. Imagine living in a time when shouting such a phrase almost guarantees instantaneously raising a posse.

====================

At the moment I'm listening to Mil Nicholson narrate, and she sounds like a sinister Donald Duck, especially when she does Gride, Ralph, Squeers, Hawk, and strangely enough, older women, like Gride's housekeeper. It creeps me out and urges me to laugh at the same time. Very strange.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow Curiosities,

This week’s selection of chapters is mostly concerned with our friend Nicholas’s love interest Madeline Bray and with Nicholas’s attempts at thwarting the marriage plans h..."

Tristram

I agree with you. This chapter is one of great description. Gride, his residence, his actions, his housekeeper Peg. The reader has the opportunity to see how each of the separate descriptions of a person, a place, and an action all weave together to create a remarkable and memorable picture.

When we add to the very distasteful picture the mention of Madeline, in the chapter referred to as “little Madeline” we are now in the presence of polar opposites. On the one hand Little Madeline is sweet, innocent, young and naive; on the other, Gride’s world is one of dust, depravity and decay. Madeline’s plight is enhanced, and thus our knight Nicholas will be all the more welcome when (and if) he can save her.

The chapter also slips into our consciousness a character by the name of Brooker. How does he fit into the plot and why does he know Ralph. Generally, a late arrival in a Dickens novel signals an important event to come. What could it be?

This week’s selection of chapters is mostly concerned with our friend Nicholas’s love interest Madeline Bray and with Nicholas’s attempts at thwarting the marriage plans h..."

Tristram

I agree with you. This chapter is one of great description. Gride, his residence, his actions, his housekeeper Peg. The reader has the opportunity to see how each of the separate descriptions of a person, a place, and an action all weave together to create a remarkable and memorable picture.

When we add to the very distasteful picture the mention of Madeline, in the chapter referred to as “little Madeline” we are now in the presence of polar opposites. On the one hand Little Madeline is sweet, innocent, young and naive; on the other, Gride’s world is one of dust, depravity and decay. Madeline’s plight is enhanced, and thus our knight Nicholas will be all the more welcome when (and if) he can save her.

The chapter also slips into our consciousness a character by the name of Brooker. How does he fit into the plot and why does he know Ralph. Generally, a late arrival in a Dickens novel signals an important event to come. What could it be?

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 52 continues where the previous chapter stopped, and we find Nicholas arrest his course and take his counsel with Newman lest he should be taken for and as a thief. It soon becomes obvious ..."

To some degree I sense a subtle shift for the better in Nicholas. He is still impetuous and still hot-tempered (maybe now “warm” headed?) but his ever-present concern for his mother and sister is now shown in his actions towards Madeline’s fate as well. True, Frank is in his way, and yes Nicholas needs to tell Frank what is going on between Gride and Madeline, but Nicholas, as a knight in shining armour, is maturing slightly.

Newman Noggs seems to me to perform the role of a parent to Nicholas. Early in the novel he slips Nicholas a note of help/support, he takes Nicholas in when Nicholas returns to London from Dotheboys Hall, he seems to offer advice that is worldly and wise, he supports Nicholas’s first attempt to find the home of Madeline, and he seems to always be in the right place at the right time to pass on information that will assist Nicholas.

I do agree with Tristram that the presence of both the Kenwigs and Bray are ways for Dickens to comment, both accurately and with humour, on both the nuances and specifics of the class structure of the time. To have a barber draw the line on offering services to a coal-heaver is both funny and sobering at the same time.

And yes, as the Kenwig’s probably leave NN for the last time we must be approaching the end of the novel.

To some degree I sense a subtle shift for the better in Nicholas. He is still impetuous and still hot-tempered (maybe now “warm” headed?) but his ever-present concern for his mother and sister is now shown in his actions towards Madeline’s fate as well. True, Frank is in his way, and yes Nicholas needs to tell Frank what is going on between Gride and Madeline, but Nicholas, as a knight in shining armour, is maturing slightly.

Newman Noggs seems to me to perform the role of a parent to Nicholas. Early in the novel he slips Nicholas a note of help/support, he takes Nicholas in when Nicholas returns to London from Dotheboys Hall, he seems to offer advice that is worldly and wise, he supports Nicholas’s first attempt to find the home of Madeline, and he seems to always be in the right place at the right time to pass on information that will assist Nicholas.

I do agree with Tristram that the presence of both the Kenwigs and Bray are ways for Dickens to comment, both accurately and with humour, on both the nuances and specifics of the class structure of the time. To have a barber draw the line on offering services to a coal-heaver is both funny and sobering at the same time.

And yes, as the Kenwig’s probably leave NN for the last time we must be approaching the end of the novel.

"I'll be married in the bottle-green," cried Arthur Gride."

Chapter 51

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘The bottle-green,’ said old Arthur; ‘the bottle-green was a famous suit to wear, and I bought it very cheap at a pawnbroker’s, and there was—he, he, he!—a tarnished shilling in the waistcoat pocket. To think that the pawnbroker shouldn’t have known there was a shilling in it! I knew it! I felt it when I was examining the quality. Oh, what a dull dog of a pawnbroker! It was a lucky suit too, this bottle-green. The very day I put it on first, old Lord Mallowford was burnt to death in his bed, and all the post-obits fell in. I’ll be married in the bottle-green. Peg. Peg Sliderskew—I’ll wear the bottle-green!’

This call, loudly repeated twice or thrice at the room-door, brought into the apartment a short, thin, weasen, blear-eyed old woman, palsy-stricken and hideously ugly, who, wiping her shrivelled face upon her dirty apron, inquired, in that subdued tone in which deaf people commonly speak:

‘Was that you a calling, or only the clock a striking? My hearing gets so bad, I never know which is which; but when I hear a noise, I know it must be one of you, because nothing else never stirs in the house.’

‘Me, Peg, me,’ said Arthur Gride, tapping himself on the breast to render the reply more intelligible.

‘You, eh?’ returned Peg. ‘And what do you want?’

‘I’ll be married in the bottle-green,’ cried Arthur Gride.

‘It’s a deal too good to be married in, master,’ rejoined Peg, after a short inspection of the suit. ‘Haven’t you got anything worse than this?’

‘Nothing that’ll do,’ replied old Arthur.

‘Why not do?’ retorted Peg. ‘Why don’t you wear your every-day clothes, like a man—eh?’

‘They an’t becoming enough, Peg,’ returned her master.

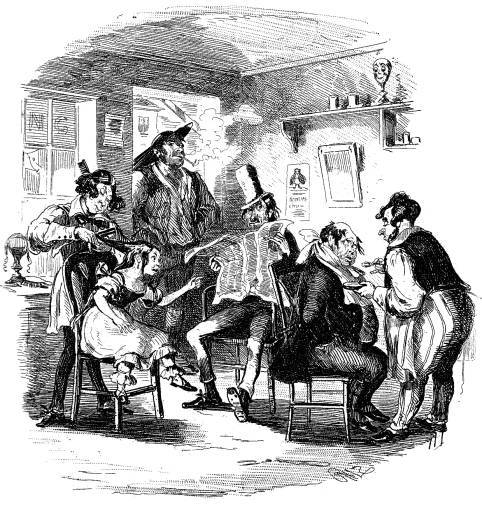

Great Excitement of Miss Kenwigs at the Hairdresser's Shop

Chapter 52

Phiz

Commentary:

The scene could easily be from one of Dickens's earliest Sketches by Boz, for it reveals his penchant for character comedy and eye for detail in situations common enough in lower middle-class early nineteenth-century London. However, here the cast of characters is not entirely random or accidental, for coincidence connects Noggs, Miss Kenwigs, and the gentleman being shaved. The comic and domestic action, constituting a "recognition scene," contrasts with the more serious and tumultuous action scene, "The Last Brawl between Sir Mulberry and His Pupil," in the previous month's illustrations. In chapter 52, "Nicholas despairs of rescuing Madeline Bray, but plucks up his Spirits again, and determines to attempt it. Domestic Intelligence of the Kenwigses and Lillyvicks," Dickens loosely stitches the comic subplot involving the Kenwigses to the main plot involving the conspiracy of the old moneylender and Ralph Nickleby against Madeline Bray and her invalid father. The point of conjunction is the local hairdresser's-cum-barber's in the neighborhood of the Kenwigses' residence, where Ralph Nickleby's clerk, Newman Noggs (seen reading a newspaper in Phiz's illustration), rents the upstairs rooms. Providentially, Lillyvick has returned to London after Miss Petowker abandoned him in favor of a half-pay officer, and is now reunited with his relatives. Note that Phiz cannot pass up the opportunity to depict the coal-heaver ("the applicant" who has just been rejected as a customer), even though he has left before the "recognition" scene occurs:

The applicant stared; grinned at Newman Noggs, who appeared highly entertained; looked slightly round the shop, as if in depreciation of the pomatum pots and other articles of stock; took his pipe out of his mouth and gave a very loud whistle; and then put it in again, and walked out.

The old gentleman who had just been lathered, and who was sitting in a melancholy manner with his face turned towards the wall, appeared quite unconscious of this incident, and to be insensible to everything around him in the depth of a reverie — a very mournful one, to judge from the sighs he occasionally vented — in which he was absorbed. Affected by this example, the proprietor began to clip Miss Kenwigs, the journeyman to scrape the old gentleman, and Newman to read last Sunday's paper, all three in silence: when Miss Kenwigs uttered a shrill little scream, and Newman, raising his eyes, saw that it had been elicited by the circumstance of the old gentleman turning his head, and disclosing the features of Mr Lillyvick the collector.

"Thieves! Thieves!" Shrieked the usurer, starting up and folding his book to his breast; "Robbers! Murder!"

Chapter 53

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

The room had no other light than that which it derived from a dim and dirt-clogged lamp, whose lazy wick, being still further obscured by a dark shade, cast its feeble rays over a very little space, and left all beyond in heavy shadow. This lamp the money-lender had drawn so close to him, that there was only room between it and himself for the book over which he bent; and as he sat, with his elbows on the desk, and his sharp cheek-bones resting on his hands, it only served to bring out his ugly features in strong relief, together with the little table at which he sat, and to shroud all the rest of the chamber in a deep sullen gloom. Raising his eyes, and looking vacantly into this gloom as he made some mental calculation, Arthur Gride suddenly met the fixed gaze of a man.

‘Thieves! thieves!’ shrieked the usurer, starting up and folding his book to his breast. ‘Robbers! Murder!’

‘What is the matter?’ said the form, advancing.

‘Keep off!’ cried the trembling wretch. ‘Is it a man or a—a—’

‘For what do you take me, if not for a man?’ was the inquiry.

‘Yes, yes,’ cried Arthur Gride, shading his eyes with his hand, ‘it is a man, and not a spirit. It is a man. Robbers! robbers!’

‘For what are these cries raised? Unless indeed you know me, and have some purpose in your brain?’ said the stranger, coming close up to him. ‘I am no thief.’

‘What then, and how come you here?’ cried Gride, somewhat reassured, but still retreating from his visitor: ‘what is your name, and what do you want?’

‘My name you need not know,’ was the reply. ‘I came here, because I was shown the way by your servant. I have addressed you twice or thrice, but you were too profoundly engaged with your book to hear me, and I have been silently waiting until you should be less abstracted. What I want I will tell you, when you can summon up courage enough to hear and understand me.’

Arthur Gride, venturing to regard his visitor more attentively, and perceiving that he was a young man of good mien and bearing, returned to his seat, and muttering that there were bad characters about, and that this, with former attempts upon his house, had made him nervous, requested his visitor to sit down. This, however, he declined.

‘Good God! I don’t stand up to have you at an advantage,’ said Nicholas (for Nicholas it was), as he observed a gesture of alarm on the part of Gride. ‘Listen to me. You are to be married tomorrow morning.’

‘N—n—no,’ rejoined Gride. ‘Who said I was? How do you know that?’

‘No matter how,’ replied Nicholas, ‘I know it. The young lady who is to give you her hand hates and despises you. Her blood runs cold at the mention of your name; the vulture and the lamb, the rat and the dove, could not be worse matched than you and she. You see I know her.’

Gride looked at him as if he were petrified with astonishment, but did not speak; perhaps lacking the power.

‘You and another man, Ralph Nickleby by name, have hatched this plot between you,’ pursued Nicholas. ‘You pay him for his share in bringing about this sale of Madeline Bray. You do. A lie is trembling on your lips, I see.’

"I must beseech you to contemplate again the fearful course to which you have been impelled".

Chapter 53

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘Oh!’ thought Nicholas, ‘that this slender chance might not be lost, and that I might prevail, if it were but for one week’s time and reconsideration!’

‘You are charged with some commission to me, sir,’ said Madeline, presenting herself in great agitation. ‘Do not press it now, I beg and pray you. The day after tomorrow; come here then.’

‘It will be too late—too late for what I have to say,’ rejoined Nicholas, ‘and you will not be here. Oh, madam, if you have but one thought of him who sent me here, but one last lingering care for your own peace of mind and heart, I do for God’s sake urge you to give me a hearing.’

She attempted to pass him, but Nicholas gently detained her.

‘A hearing,’ said Nicholas. ‘I ask you but to hear me: not me alone, but him for whom I speak, who is far away and does not know your danger. In the name of Heaven hear me!’

The poor attendant, with her eyes swollen and red with weeping, stood by; and to her Nicholas appealed in such passionate terms that she opened a side-door, and, supporting her mistress into an adjoining room, beckoned Nicholas to follow them.

‘Leave me, sir, pray,’ said the young lady.

‘I cannot, will not leave you thus,’ returned Nicholas. ‘I have a duty to discharge; and, either here, or in the room from which we have just now come, at whatever risk or hazard to Mr. Bray, I must beseech you to contemplate again the fearful course to which you have been impelled.’

‘What course is this you speak of, and impelled by whom, sir?’ demanded the young lady, with an effort to speak proudly.

‘I speak of this marriage,’ returned Nicholas, ‘of this marriage, fixed for tomorrow, by one who never faltered in a bad purpose, or lent his aid to any good design; of this marriage, the history of which is known to me, better, far better, than it is to you. I know what web is wound about you. I know what men they are from whom these schemes have come. You are betrayed and sold for money; for gold, whose every coin is rusted with tears, if not red with the blood of ruined men, who have fallen desperately by their own mad hands.’

‘You say you have a duty to discharge,’ said Madeline, ‘and so have I. And with the help of Heaven I will perform it.’

‘Say rather with the help of devils,’ replied Nicholas, ‘with the help of men, one of them your destined husband, who are—’

‘I must not hear this,’ cried the young lady, striving to repress a shudder, occasioned, as it seemed, even by this slight allusion to Arthur Gride. ‘This evil, if evil it be, has been of my own seeking. I am impelled to this course by no one, but follow it of my own free will. You see I am not constrained or forced. Report this,’ said Madeline, ‘to my dear friend and benefactor, and, taking with you my prayers and thanks for him and for yourself, leave me for ever!’

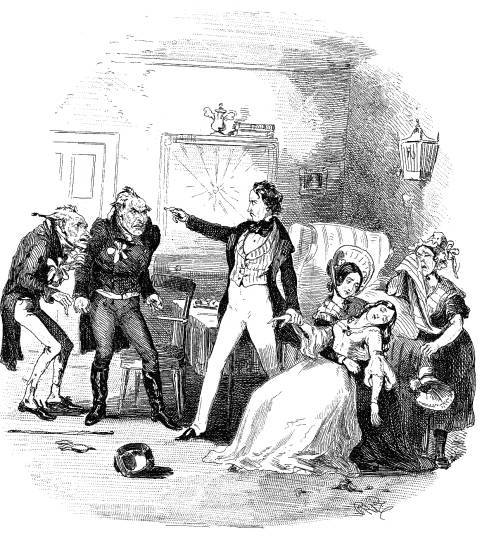

Nicholas Congratulates Arthur Gride on His Wedding Morning

Chapter 54

Phiz

Commentary:

The plate's title lends a further degree of irony to the climactic moment since Nicholas and death providentially rescue Madeline Bray from Gride's clutches as once again Nicholas frustrates his uncle's designs. The melodramatic nature of the scene in chapter 54, "The Crisis of the Project, and its Result," so obvious in the rhetoric of Nicholas as he cows the misers, is also reflected in the physical disposition and poses of the characters in Phiz's plate. Thus, text and illustration work together to underscore a memorable moment in the main plot. While the indignant youth (center) attempts to comfort Madeline Bray (her limp hand signifying her unconsciousness) with his left hand, he denounces the two malignant plotters (Ralph Nickleby and Arthur Gride, left) as "Wretches" with his right hand.

The sequence began with the arrival of the aged groom and his best man to collect their prize. Madeline's father, conflicted about granting his permission for the marriage, had retired with his daughter when Nicholas and Kate unexpectedly arrived, just before a thump on the floor above them announced Bray's collapse. Bray has died, presumably of the stress engendered by the insupportable situation. The precise moment that Phiz has realized is when, having carried Madeline insensible downstairs to be ministered to by his sister (identified by her bonnet in the illustration) and tearful servant (right), Nicholas notes that Gride's hold over Bray is at an end:

"That the bond, due today at twelve, is now waste paper. That your contemplated fraud shall be discovered yet. That your schemes are known to man, and overthrown by Heaven. Wretches, that he defies you both to do your worst!"

He drew Ralph Nickleby to the further end of the room, and pointed towards Gride

Chapter 54

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

‘One would think,’ said Ralph, speaking, in spite of himself, in a low and subdued voice, ‘that there was a funeral going on here, and not a wedding.’

‘He, he!’ tittered his friend, ‘you are so—so very funny!’

‘I need be,’ remarked Ralph, drily, ‘for this is rather dull and chilling. Look a little brisker, man, and not so hangdog like!’

‘Yes, yes, I will,’ said Gride. ‘But—but—you don’t think she’s coming just yet, do you?’

‘Why, I suppose she’ll not come till she is obliged,’ returned Ralph, looking at his watch, ‘and she has a good half-hour to spare yet. Curb your impatience.’

‘I—I—am not impatient,’ stammered Arthur. ‘I wouldn’t be hard with her for the world. Oh dear, dear, not on any account. Let her take her time—her own time. Her time shall be ours by all means.’

While Ralph bent upon his trembling friend a keen look, which showed that he perfectly understood the reason of this great consideration and regard, a footstep was heard upon the stairs, and Bray himself came into the room on tiptoe, and holding up his hand with a cautious gesture, as if there were some sick person near, who must not be disturbed.

‘Hush!’ he said, in a low voice. ‘She was very ill last night. I thought she would have broken her heart. She is dressed, and crying bitterly in her own room; but she’s better, and quite quiet. That’s everything!’

‘She is ready, is she?’ said Ralph.

‘Quite ready,’ returned the father.

‘And not likely to delay us by any young-lady weaknesses—fainting, or so forth?’ said Ralph.

‘She may be safely trusted now,’ returned Bray. ‘I have been talking to her this morning. Here! Come a little this way.’

He drew Ralph Nickleby to the further end of the room, and pointed towards Gride, who sat huddled together in a corner, fumbling nervously with the buttons of his coat, and exhibiting a face, of which every skulking and base expression was sharpened and aggravated to the utmost by his anxiety and trepidation.

‘Look at that man,’ whispered Bray, emphatically. ‘This seems a cruel thing, after all.’

‘What seems a cruel thing?’ inquired Ralph, with as much stolidity of face, as if he really were in utter ignorance of the other’s meaning.

‘This marriage,’ answered Bray. ‘Don’t ask me what. You know as well as I do.’

Ralph shrugged his shoulders, in silent deprecation of Bray’s impatience, and elevated his eyebrows, and pursed his lips, as men do when they are prepared with a sufficient answer to some remark, but wait for a more favourable opportunity of advancing it, or think it scarcely worth while to answer their adversary at all.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 52

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 52 And what do you yourselves think of Nicholas at his point?"

I think Nicholas is someone who receives a lot of unearned lucky breaks and has the haughtiness to think it was his talent that earned them. (Remember how the one play he wrote he copied? Why would Crummles hire someone to do that?)

His anger is born out of a kind of snobbishness, I think, and the effect he has on people has me befuddled. I once knew a CEO who wasn't very good at what he did, but he knew how to wear the right kind of suit and color his hair the right kind of color, and he was admired for that rather than his content. I wonder if this isn't how Nicholas passes through the world?

What would he be like if instead of having fallen into the theater and the Cheerybles business, he was still working for 5 shillings a week tutoring the Kenwigs' kids? Certainly his mother and sister would not be living where they are.

I know I'm too hard on him. It's not that he doesn't have positive qualities; it's that his poorer ones cast a shadow over the richer ones.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 52 This may have been the last we will see of the Kenwigs"

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 52 This may have been the last we will see of the Kenwigs"And good riddance -- not a family I ever liked. One gets the feeling that the Kenswigs see their daughters as a way to riches, like Bray sees his daughter as a way out of debt. But there are differences. The Kenswigs do care for their children, while Mr, Bray treats his daughter like a Scrooge might treat his maid.

Actually I see Squeers in Mr. Bray. There is a difference, but not a lot, between the way Squeers treats Smike and Bray treats Madeline -- like they were owned.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 52 This may have been the last we will see of the Kenwigs"

And good riddance -- not a family I ever liked. One gets the feeling that the Kenswigs see their daughters as a ..."

Xan

Yes. You make a very good point on how children are perceived in this novel. From Mrs Nickleby’s thoughts of Kate’s marriage to Hawk/Verisopht to Bray’s designs for Madeline, parents see their children as commodities to be bought, sold, or bartered. Even the Crummles see their children as agents for financial success.

How depressing to think that social mobility or social security comes with each addition to a family by way of children.

And good riddance -- not a family I ever liked. One gets the feeling that the Kenswigs see their daughters as a ..."

Xan

Yes. You make a very good point on how children are perceived in this novel. From Mrs Nickleby’s thoughts of Kate’s marriage to Hawk/Verisopht to Bray’s designs for Madeline, parents see their children as commodities to be bought, sold, or bartered. Even the Crummles see their children as agents for financial success.

How depressing to think that social mobility or social security comes with each addition to a family by way of children.

Kim wrote: "Great Excitement of Miss Kenwigs at the Hairdresser's Shop

Chapter 52

Phiz

Commentary:

The scene could easily be from one of Dickens's earliest Sketches by Boz, for it reveals his penchant for ..."

Kim. Great illustrations this week. I really like the barber shop illustration. Hair dressers and barber shops ... are there two places in society where the social classes mingle, even momentarily, where fashion is on display, or being created on one’s head?

Phiz has captured the scene wonderfully well. Lots of people, different positions, different clothes, a bustle of activity.

The Dickens touch of the barber not allowing the coal-heaver into the shop was perfect.

Chapter 52

Phiz

Commentary:

The scene could easily be from one of Dickens's earliest Sketches by Boz, for it reveals his penchant for ..."

Kim. Great illustrations this week. I really like the barber shop illustration. Hair dressers and barber shops ... are there two places in society where the social classes mingle, even momentarily, where fashion is on display, or being created on one’s head?

Phiz has captured the scene wonderfully well. Lots of people, different positions, different clothes, a bustle of activity.

The Dickens touch of the barber not allowing the coal-heaver into the shop was perfect.

Kim wrote: ""I must beseech you to contemplate again the fearful course to which you have been impelled".

Chapter 53

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘Oh!’ thought Nicholas, ‘that this sle..."

Both of the Barnard illustrations are powerful, perhaps the first that is presented in almost total darkness the better of the two. Nicholas as the avenger, as a spector to Gride, or as a fallible knight trying to save the honour of Madeline in the second both make me like Nicholas a bit more.

I have great difficulty liking Nicholas in the novel up to this point in the novel. I find that with the aid of the illustrations my opinion is altered. To me, the illustrations reinforce and extend the act of Nicholas as not being totally selfish, but suggest a more mature Nicholas who is acting as an agent of goodness in a diluted form of Cheeryble-ism.

Chapter 53

Fred Barnard

Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘Oh!’ thought Nicholas, ‘that this sle..."

Both of the Barnard illustrations are powerful, perhaps the first that is presented in almost total darkness the better of the two. Nicholas as the avenger, as a spector to Gride, or as a fallible knight trying to save the honour of Madeline in the second both make me like Nicholas a bit more.

I have great difficulty liking Nicholas in the novel up to this point in the novel. I find that with the aid of the illustrations my opinion is altered. To me, the illustrations reinforce and extend the act of Nicholas as not being totally selfish, but suggest a more mature Nicholas who is acting as an agent of goodness in a diluted form of Cheeryble-ism.

Kim wrote: "He drew Ralph Nickleby to the further end of the room, and pointed towards Gride

Chapter 54

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

‘One would think,’ said Ralph, speaking, in spite of himself, in a low..."

What a horrid moment in the novel. Can any fairy tale contain as much revulsion as to what will soon occur as depicted in this illustration?

To see these three odious men in the same room at the same time is very powerful. Bray holds his walking stick, and we are reminded of how he had earlier thumped it on the floor. The suggestion is he may well have used it on Madeline. In this illustration we also see the harp, abandoned in the corner, but set beside Gride. I see this as emblematic of Madeline, whose life will be one of discord and lack of harmony. Could it also suggest the angelic nature of Madeline balanced against the ugly, ancient troll she is about to wed?

Chapter 54

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

‘One would think,’ said Ralph, speaking, in spite of himself, in a low..."

What a horrid moment in the novel. Can any fairy tale contain as much revulsion as to what will soon occur as depicted in this illustration?

To see these three odious men in the same room at the same time is very powerful. Bray holds his walking stick, and we are reminded of how he had earlier thumped it on the floor. The suggestion is he may well have used it on Madeline. In this illustration we also see the harp, abandoned in the corner, but set beside Gride. I see this as emblematic of Madeline, whose life will be one of discord and lack of harmony. Could it also suggest the angelic nature of Madeline balanced against the ugly, ancient troll she is about to wed?

Peter wrote: "The Dickens touch of the barber not allowing the coal-heaver into the shop was perfect..."

Peter wrote: "The Dickens touch of the barber not allowing the coal-heaver into the shop was perfect..."Yes, and then Phiz putting the coal-heaver into the illustration even though he should have been gone.

When I put this in light of Peter's comments about children being commodities to their parents, it really is a grim worldview, all status-struggle, especially when even those who seem to love their children--the Kenwigses, Mr. Crummles, maybe Mrs. Nickleby if she's capable of love--still see them that way. A Noggs or La Creevy stands out so much against this background.

If we throw in the Cheeryble brothers, it seems like none of the altruistic characters in the book are parents.

Peter wrote: "When we add to the very distasteful picture the mention of Madeline, in the chapter referred to as “little Madeline” we are now in the presence of polar opposites. On the one hand Little Madeline is sweet, innocent, young and naive; on the other, Gride’s world is one of dust, depravity and decay."

Yes, Gride's way of talking about Madeline, e.g. in terms of a morsel of food, is both objectifying and utterly disturbing in an even darker way. His reference to "little Madeline" also reminds me of Sir Mulberry, who speaks of Kate as "little Nickleby". There is the same lecherous, unwholesome attitude in both of these men.

Yes, Gride's way of talking about Madeline, e.g. in terms of a morsel of food, is both objectifying and utterly disturbing in an even darker way. His reference to "little Madeline" also reminds me of Sir Mulberry, who speaks of Kate as "little Nickleby". There is the same lecherous, unwholesome attitude in both of these men.

As to the Kenwigses seeing their children as a means to social rise and prosperity, I would not be too hard on them because unlike the Squeers family and Mr. Bray, they are capable of genuine and heartfelt affection and, at least it seems so to me, they have their children's profit on their minds as much as, maybe more than, their own. The Kenwigses want to set up Morleena in the world for Morleena's sake, for example, like average parents want their children to succeed in life: They, the parents, can feel proud of it, but it's also that they want a better life for their children. This may be more important today than it was in Victorian times when, especially among the not so wealthy, children were also an investment in one's own future security.

Tristram wrote: "The Kenwigses want to set up Morleena in the world for Morleena's sake, for example, like average parents want their children to succeed in life..."

Tristram wrote: "The Kenwigses want to set up Morleena in the world for Morleena's sake, for example, like average parents want their children to succeed in life..."That's a good point--and I think on their part the Kenwigses are also genuinely offended at a personal level: they've made this man a member of their family and he cuts them off without even telling them in person. It's definitely about the money, but it's not only about the money.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 52

And what do you yourselves think of Nicholas at his point?"

I think Nicholas is someone who receives a lot of unearned lucky breaks and has the haughtiness to think it..."

Grump.

And what do you yourselves think of Nicholas at his point?"

I think Nicholas is someone who receives a lot of unearned lucky breaks and has the haughtiness to think it..."

Grump.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 52 This may have been the last we will see of the Kenwigs"

And good riddance -- not a family I ever liked. One gets the feeling that the Kenswigs see their daughters as a ..."

See post 34.

And good riddance -- not a family I ever liked. One gets the feeling that the Kenswigs see their daughters as a ..."

See post 34.