The Old Curiosity Club discussion

The Old Curiosity Shop

>

TOCS: Chapters 06 - 10

Chapter 7 plunges us into another kind of conspiracy against Nell and her grandfather, and while we do not really know what Quilp is going to do – neither do we know why he is going to do anything, but let us be content with the assumption that spite is a very strong motivation in the dwarf, as I will continue calling him, in accordance with the narrative voice –, we are soon the wiser with regard to the plot hatched by Fred Trent and Richard Swiveller.

The chapter can be summarized in one or two sentences, and therefore will be: Sitting in Mr. Swiveller’s lodgings, Nell’s morose brother Fred by and by manages to convince his friend that it would be worthwhile if he married Nell when she is a few years older. At first, Mr. Swiveller is anything but pleased by this thought, but Fred implies that his grandfather is a man of wealth and that while he would never take kindly to him, i.e. Fred, there is nothing really he would not forgive his grand-daughter, not even a secret marriage.

This chapter teaches us quite a lot about the two young men, especially about their relationship: The narrator points out that Fred has an undoubted ascendency over his friend and that he is wont to impress his will on Richard’s mind (and actions), and so it’s no wonder that Fred keeps on explaining his plan to Swiveller although the latter shows no real interest.

What could have happened to poison the relationship between the grandfather and young Fred to such a degree that Fred has little hope of ever re-entering into the old man’s good books? Do you think this is entirely Fred’s mistake – he is unprepossessing enough –, or would the old man, too, have to be blamed for this? Could the grandfather’s bias for Nell have contributed to sowing bitterness between him and his grandson? At any rate, there is not a lot to be said in favour of Fred, seeing that he is even ready to force his sister to marry Mr. Swiveller. This clearly shows the strength of the young man’s egoism as well as his lack of respect for his sister.

What do you think of young Richard Swiveller, though? His outward appearance is quite on the scruffy side, but he seems to be full of poetry (and spirits), as his first few sentences show us:

This tendency to interlace his own sentences with bits and pieces from popular songs and from poetry reminded me a bit of Silas Wegg. Do you think that an uncommon love of poetry and an inexhaustible stock of imagination are the only things Swiveller and Silas have in common, or must we see Richard as yet another ruthless villain? Is he as vile as Fred, or can we regard him as somebody who is not particularly evil but simply selfish and given to the creature comforts of life, and who is therefore easy to manipulate?

I quite like Dick Swiveller because he is one of those characters with whom Dickens lets his imagination roam freely. Just take these two examples here:

And then this one – this is particularly touching, but already taken from the next chapter:

There is only that little affair with Miss Sophy Wackles to settle before Mr. Swiveller can become a suitor to Little Nell, but that affair will be spoken of in my recap of the next chapter.

So, let’s see: Here is Little Nell, not older than 14, but she already has two prospective husbands – Mr. Swiveller and Mr. Quilp. What might Quilp do when he notices that there is a rival? Who would you bank your money on in a fistfight between Swiveller and Quilp?

The chapter can be summarized in one or two sentences, and therefore will be: Sitting in Mr. Swiveller’s lodgings, Nell’s morose brother Fred by and by manages to convince his friend that it would be worthwhile if he married Nell when she is a few years older. At first, Mr. Swiveller is anything but pleased by this thought, but Fred implies that his grandfather is a man of wealth and that while he would never take kindly to him, i.e. Fred, there is nothing really he would not forgive his grand-daughter, not even a secret marriage.

This chapter teaches us quite a lot about the two young men, especially about their relationship: The narrator points out that Fred has an undoubted ascendency over his friend and that he is wont to impress his will on Richard’s mind (and actions), and so it’s no wonder that Fred keeps on explaining his plan to Swiveller although the latter shows no real interest.

What could have happened to poison the relationship between the grandfather and young Fred to such a degree that Fred has little hope of ever re-entering into the old man’s good books? Do you think this is entirely Fred’s mistake – he is unprepossessing enough –, or would the old man, too, have to be blamed for this? Could the grandfather’s bias for Nell have contributed to sowing bitterness between him and his grandson? At any rate, there is not a lot to be said in favour of Fred, seeing that he is even ready to force his sister to marry Mr. Swiveller. This clearly shows the strength of the young man’s egoism as well as his lack of respect for his sister.

What do you think of young Richard Swiveller, though? His outward appearance is quite on the scruffy side, but he seems to be full of poetry (and spirits), as his first few sentences show us:

”’Fred,’ said Mr Swiveller, ‘remember the once popular melody of Begone dull care; fan the sinking flame of hilarity with the wing of friendship; and pass the rosy wine.’”

This tendency to interlace his own sentences with bits and pieces from popular songs and from poetry reminded me a bit of Silas Wegg. Do you think that an uncommon love of poetry and an inexhaustible stock of imagination are the only things Swiveller and Silas have in common, or must we see Richard as yet another ruthless villain? Is he as vile as Fred, or can we regard him as somebody who is not particularly evil but simply selfish and given to the creature comforts of life, and who is therefore easy to manipulate?

I quite like Dick Swiveller because he is one of those characters with whom Dickens lets his imagination roam freely. Just take these two examples here:

”By a like pleasant fiction his single chamber was always mentioned in a plural number. In its disengaged times, the tobacconist had announced it in his window as 'apartments' for a single gentleman, and Mr Swiveller, following up the hint, never failed to speak of it as his rooms, his lodgings, or his chambers, conveying to his hearers a notion of indefinite space, and leaving their imaginations to wander through long suites of lofty halls, at pleasure.”

And then this one – this is particularly touching, but already taken from the next chapter:

”’Not exactly, Fred,’ replied the imperturable Richard, continuing to write with a businesslike air. ‘I enter in this little book the names of the streets that I can't go down while the shops are open. This dinner today closes Long Acre. I bought a pair of boots in Great Queen Street last week, and made that no throughfare too. There's only one avenue to the Strand left often now, and I shall have to stop up that to-night with a pair of gloves. The roads are closing so fast in every direction, that in a month's time, unless my aunt sends me a remittance, I shall have to go three or four miles out of town to get over the way.’”

There is only that little affair with Miss Sophy Wackles to settle before Mr. Swiveller can become a suitor to Little Nell, but that affair will be spoken of in my recap of the next chapter.

So, let’s see: Here is Little Nell, not older than 14, but she already has two prospective husbands – Mr. Swiveller and Mr. Quilp. What might Quilp do when he notices that there is a rival? Who would you bank your money on in a fistfight between Swiveller and Quilp?

Chapter 8 reminded me a little bit of the Sketches by Boz in that the bulk of the chapter is not really necessary for the plot. At least that’s what I think. However, Dickens seems to have relished the idea of describing the soirée at Miss Wackles’s house. We get to know Miss Sophia Wackles as well as her mother and her two sisters, one elder, the other younger than she:

This short, but memorable description reminded me of the typical secondary level family in Dickens’s novels, i.e. a family consisting of minor characters. We have just left the Kenwigs family, but even in Dickens’s later novels, we would find a family background that was just drawn for entertainment or from a spirit of creative exuberance. Another touch to the whole picture is Mr. Cheggs, who is Mr. Swiveller’s rival and who reminded me of characters such a John Chivery or Mr. Sampson, the Wilfer pilot.

Dickens gives us a lot to enjoy, e.g. the fact that Mr. Swiveller actually goes to the dance in order to pick a quarrel with Sophy – for instance by proving a most jealous and exacting suitor – and so to find an excuse for ending the relationship before it gets too much into the drift of marriage proposals and the like. When he is there, however, he feels real jealousy because of Mr. Cheggs’s presence, and he is just about to jettison all his plans with regard to ridding himself of Sophy. What he does not know, however, is that Sophy wants to use that opportunity to draw him out of his entrenched position and that she half uses Mr. Cheggs as a bait. Although Richard Swiveller seems to be her favourite, do you think she will eventually be satisfied, and maybe even happy, with Mr. Cheggs? And here’s an even trickier question: What might have induced her to take a fancy to Mr. Swiveller in the first place?

”The spot was at Chelsea, for there Miss Sophia Wackles resided with her widowed mother and two sisters, in conjunction with whom she maintained a very small day-school for young ladies of proportionate dimensions; a circumstance which was made known to the neighbourhood by an oval board over the front first-floor windows, whereupon appeared in circumambient flourishes the words ‘Ladies’ Seminary’; and which was further published and proclaimed at intervals between the hours of half-past nine and ten in the morning, by a straggling and solitary young lady of tender years standing on the scraper on the tips of her toes and making futile attempts to reach the knocker with spelling-book. The several duties of instruction in this establishment were this discharged. English grammar, composition, geography, and the use of the dumb-bells, by Miss Melissa Wackles; writing, arithmetic, dancing, music, and general fascination, by Miss Sophia Wackles; the art of needle-work, marking, and samplery, by Miss Jane Wackles; corporal punishment, fasting, and other tortures and terrors, by Mrs Wackles. Miss Melissa Wackles was the eldest daughter, Miss Sophy the next, and Miss Jane the youngest. Miss Melissa might have seen five-and-thirty summers or thereabouts, and verged on the autumnal; Miss Sophy was a fresh, good humoured, buxom girl of twenty; and Miss Jane numbered scarcely sixteen years. Mrs Wackles was an excellent but rather venemous old lady of three-score.”

This short, but memorable description reminded me of the typical secondary level family in Dickens’s novels, i.e. a family consisting of minor characters. We have just left the Kenwigs family, but even in Dickens’s later novels, we would find a family background that was just drawn for entertainment or from a spirit of creative exuberance. Another touch to the whole picture is Mr. Cheggs, who is Mr. Swiveller’s rival and who reminded me of characters such a John Chivery or Mr. Sampson, the Wilfer pilot.

Dickens gives us a lot to enjoy, e.g. the fact that Mr. Swiveller actually goes to the dance in order to pick a quarrel with Sophy – for instance by proving a most jealous and exacting suitor – and so to find an excuse for ending the relationship before it gets too much into the drift of marriage proposals and the like. When he is there, however, he feels real jealousy because of Mr. Cheggs’s presence, and he is just about to jettison all his plans with regard to ridding himself of Sophy. What he does not know, however, is that Sophy wants to use that opportunity to draw him out of his entrenched position and that she half uses Mr. Cheggs as a bait. Although Richard Swiveller seems to be her favourite, do you think she will eventually be satisfied, and maybe even happy, with Mr. Cheggs? And here’s an even trickier question: What might have induced her to take a fancy to Mr. Swiveller in the first place?

Chapter 9 begins with an account of Little Nell’s mental distress arising from the changes she has had to witness in her grandfather’s frame and behaviour, changes that have made her start

“And yet,” for all the worries and responsibilities Nell has to endure, “to the old man's vision, Nell was still the same.”

What does this show us? Is this, in the first place, testimony to Little Nell’s self-denial and forbearance, to her inner strength, which enables her to hide her worries from her grandfather in order to spare him further anxiety? And if so, can we really assume a fourteen-year old girl to have such reservoirs of power in her? Or does this sentence tell us something about the egocentricity of the old man, who is bent on following his own train of thought and unable to see anything that does not fit in with his view on the world?

On the third night after Nell’s interview with Quilp, she and her grandfather are sitting in the shop together, the old man having abstained from his nightly excursions for the time being, and Mr. Trent is bemoaning Quilp’s tarrying in giving an answer to his request. He says that if Quilp forsakes them right now, when he, Trent, has invested so much time and money into his plan, he will leave them beggars. Thereupon, we have this short altercation:

This seems to be the major point of discord between Nell and her grandfather, and it is undoubtedly the cause for what is going to happen to the two of them, the inciting moment of the plot. What does it tell you about the two characters, though?

Their conversation is being overheard by Quilp himself, who has finally arrived and, availing himself of the opportunity to listen in on his potential victims, taken a chair and perched himself on its back, with his feet resting on the seat,

I found this little detail quite remarkable. Any comments?

Quilp’s presence soon leads to the withdrawing of Little Nell, whom the dwarf leers at in his usual way. He also comments on a kiss the grandfather bestows on his grand-child, in very unsettling words. Once the girl has gone, however, the dwarf bends his mind on his business, and he shows his anger at having fallen for Grandfather Trent’s line instead of realizing from the very start that the old man has no real prospects but is simply an ordinary gambler. Quilp is obviously exasperated at the thought of having thrown his good money into the bottomless pit of games of chance, but, as he says, Old Trent’s reputation for being rich, his mean and miserly ways of living like a recluse with his grand-daughter, have pulled the wool over his eyes. However, he makes it clear that now there is an end to it, i.e. that he will not advance any further money.

The old man takes exception at being called a “shallow gambler”, stressing that he never gambled for the sake of pleasure-seeking or excitement, but only in order to ensure a good future for Little Nell. One may ask oneself the question whether this is true, i.e. whether there is no addiction to the gaming-table within him. He might have started this course of action with a view to improving Nell’s prospects, but there might still be the chance that by now gambling, and winning money for Nell, have turned into an obsession with him.

When asked by the old man how he got to know a secret so well-kept, Quilp, remembering the insults Kit has voiced against him, takes up a suggestion made by the old man and tells him that it was indeed Kit. Probably, this is not only due to the dwarf’s vengefulness but also a well-calculated plan of isolating the old man from anyone who might want to help him.

”to trace in his words and looks the dawning of despondent madness; to watch and wait and listen for confirmation of these things day after day, and to feel and know that, come what might, they were alone in the world with no one to help or advise or care about them […]”

“And yet,” for all the worries and responsibilities Nell has to endure, “to the old man's vision, Nell was still the same.”

What does this show us? Is this, in the first place, testimony to Little Nell’s self-denial and forbearance, to her inner strength, which enables her to hide her worries from her grandfather in order to spare him further anxiety? And if so, can we really assume a fourteen-year old girl to have such reservoirs of power in her? Or does this sentence tell us something about the egocentricity of the old man, who is bent on following his own train of thought and unable to see anything that does not fit in with his view on the world?

On the third night after Nell’s interview with Quilp, she and her grandfather are sitting in the shop together, the old man having abstained from his nightly excursions for the time being, and Mr. Trent is bemoaning Quilp’s tarrying in giving an answer to his request. He says that if Quilp forsakes them right now, when he, Trent, has invested so much time and money into his plan, he will leave them beggars. Thereupon, we have this short altercation:

”’What if we are?’ said the child boldly. ‘Let us be beggars, and be happy.’

‘Beggars – and happy!’ said the old man. ‘Poor child!’

‘Dear grandfather,’ cried the girl with an energy which shone in her flushed face, trembling voice, and impassioned gesture, ‘I am not a child in that I think, but even if I am, oh hear me pray that we may beg, or work in open roads or fields, to earn a scanty living, rather than live as we do now.’

‘Nelly!’ said the old man.”

This seems to be the major point of discord between Nell and her grandfather, and it is undoubtedly the cause for what is going to happen to the two of them, the inciting moment of the plot. What does it tell you about the two characters, though?

Their conversation is being overheard by Quilp himself, who has finally arrived and, availing himself of the opportunity to listen in on his potential victims, taken a chair and perched himself on its back, with his feet resting on the seat,

”gratifying at the same time that taste for doing something fantastic and monkey-like, which on all occasions had strong possession of him.”

I found this little detail quite remarkable. Any comments?

Quilp’s presence soon leads to the withdrawing of Little Nell, whom the dwarf leers at in his usual way. He also comments on a kiss the grandfather bestows on his grand-child, in very unsettling words. Once the girl has gone, however, the dwarf bends his mind on his business, and he shows his anger at having fallen for Grandfather Trent’s line instead of realizing from the very start that the old man has no real prospects but is simply an ordinary gambler. Quilp is obviously exasperated at the thought of having thrown his good money into the bottomless pit of games of chance, but, as he says, Old Trent’s reputation for being rich, his mean and miserly ways of living like a recluse with his grand-daughter, have pulled the wool over his eyes. However, he makes it clear that now there is an end to it, i.e. that he will not advance any further money.

The old man takes exception at being called a “shallow gambler”, stressing that he never gambled for the sake of pleasure-seeking or excitement, but only in order to ensure a good future for Little Nell. One may ask oneself the question whether this is true, i.e. whether there is no addiction to the gaming-table within him. He might have started this course of action with a view to improving Nell’s prospects, but there might still be the chance that by now gambling, and winning money for Nell, have turned into an obsession with him.

When asked by the old man how he got to know a secret so well-kept, Quilp, remembering the insults Kit has voiced against him, takes up a suggestion made by the old man and tells him that it was indeed Kit. Probably, this is not only due to the dwarf’s vengefulness but also a well-calculated plan of isolating the old man from anyone who might want to help him.

When Quilp takes his leave, he is watched by someone who has also witnessed his entering the house. This someone, it quickly turns out, is no one else but Kit, who, knowing that Little Nell is often alone in the house, stands guard in front of the shop lest anything untoward should happen to her. Maybe, he does it, too, with a view to catching a glimpse of her at the window.

When he returns home after a while, into a poor but cleanly apartment which he shares with his mother, Mrs. Nubbles, and two younger siblings, his mother also says that some people would think that he is in love with Little Nell, a surmise that the boy roundly rejects. Not only a lady can protest too much, methinks … Do you think that Kit has fallen in love with Little Nell? Or is he simply moved by pity and the feeling that the girl needs someone to stand by her? All in all, he seems to be a very caring and generous boy, as the following passage shows:

Mother and son talk about Little Nell’s situation, and the mother says that she does not wonder the grandfather tries to keep his nocturnal excursions a secret from Kit because, after all, it’s extremely cruel to leave a young girl alone in such a big old house every single night. Kit replies that he is sure the old man does not mean any harm since he does not see the potential cruelty in his actions. Their conversation is eventually interrupted by the arrival of Little Nell – breathless and pale –, who has some important news to impart. Nell says that her grandfather has experienced a sudden decline in health, as though after a traumatic experience, and that the mention of Kit’s name increased the old man’s fitfulness and anxiety. Apparently, her grandfather feels betrayed by Kit for something the boy has done, thus severing all ties between the Trents and himself, and Little Nell has come to tell Kit herself, feeling that it would be too cruel to let somebody else carry that final message. Little Nell bursts out:

Apparently, even Mrs. Nubbles, although she surely does trust in her son’s loyalty and honesty, feels somewhat doubtful of Kit’s not having lapsed unconsciously after Little Nell’s emotional words. What do you think about Little Nell’s readiness to believe in her grandfather’s ravings rather than in the mute loyalty of Kit? Is it childish? Is it thankless? And what does the grandfather’s readiness to believe Quilp’s incrimination of Kit say about the old man?

However you look at the question, it seems as though Quilp wanted to cut off Little Nell and her grandfather from every friend they might have. Why could he want to do that?

When he returns home after a while, into a poor but cleanly apartment which he shares with his mother, Mrs. Nubbles, and two younger siblings, his mother also says that some people would think that he is in love with Little Nell, a surmise that the boy roundly rejects. Not only a lady can protest too much, methinks … Do you think that Kit has fallen in love with Little Nell? Or is he simply moved by pity and the feeling that the girl needs someone to stand by her? All in all, he seems to be a very caring and generous boy, as the following passage shows:

”Kit was disposed to be out of temper, as the best of us are too often – but he looked at the youngest child who was sleeping soundly, and from him to his other brother in the clothes-basket, and from him to their mother, who had been at work without complaint since morning, and thought it would be a better and kinder thing to be good-humoured. So he rocked the cradle with his foot; made a face at the rebel in the clothes-basket, which put him in high good-humour directly; and stoutly determined to be talkative and make himself agreeable.”

Mother and son talk about Little Nell’s situation, and the mother says that she does not wonder the grandfather tries to keep his nocturnal excursions a secret from Kit because, after all, it’s extremely cruel to leave a young girl alone in such a big old house every single night. Kit replies that he is sure the old man does not mean any harm since he does not see the potential cruelty in his actions. Their conversation is eventually interrupted by the arrival of Little Nell – breathless and pale –, who has some important news to impart. Nell says that her grandfather has experienced a sudden decline in health, as though after a traumatic experience, and that the mention of Kit’s name increased the old man’s fitfulness and anxiety. Apparently, her grandfather feels betrayed by Kit for something the boy has done, thus severing all ties between the Trents and himself, and Little Nell has come to tell Kit herself, feeling that it would be too cruel to let somebody else carry that final message. Little Nell bursts out:

”’[…] Oh, Kit, what have you done? You, in whom I trusted so much, and who were almost the only friend I had!’”

Apparently, even Mrs. Nubbles, although she surely does trust in her son’s loyalty and honesty, feels somewhat doubtful of Kit’s not having lapsed unconsciously after Little Nell’s emotional words. What do you think about Little Nell’s readiness to believe in her grandfather’s ravings rather than in the mute loyalty of Kit? Is it childish? Is it thankless? And what does the grandfather’s readiness to believe Quilp’s incrimination of Kit say about the old man?

However you look at the question, it seems as though Quilp wanted to cut off Little Nell and her grandfather from every friend they might have. Why could he want to do that?

Tristram wrote: "One may ask oneself the question whether this is true, i.e. whether there is no addiction to the gaming-table within him. He might have started this course of action with a view to improving Nell’s prospects, but there might still be the chance that by now gambling, and winning money for Nell, have turned into an obsession with him..."

Tristram wrote: "One may ask oneself the question whether this is true, i.e. whether there is no addiction to the gaming-table within him. He might have started this course of action with a view to improving Nell’s prospects, but there might still be the chance that by now gambling, and winning money for Nell, have turned into an obsession with him..."Given that there is absolutely no reason for him to think the gambling table is going to pay off for him better now than it has before, other than "my luck has to change" which is what all hooked gamblers believe--I think it's fair to say the grandfather's just deceiving himself again that he's somehow superior to other gamblers because he does it for Nell. Especially since Nell has made it absolutely clear that this isn't helping her.

He's truly a wretched guy and I would rather read about Quilp, an openly and joyfully evil caricature, than about the grandfather, who's convinced himself that he's some kind of self-sacrificing saint. There is nothing whiny and self-pitying about Quilp--I grant him that, and also the advantage in a fight against Swiveler.

I am wondering what the backstory on Fred is, and what it means that Quilp placed him as a sailor. Was this to benefit Fred, or his grandfather? Why is Fred so miserable a person, and what is the mysterious fate of his and Nell's mother?

I very much enjoyed the Wackles dance, and all the intrigue and cross-purposes there, and Swiveler's rhyming and dodging. I find I enjoy reading about the Wackleses more than I did about the Kenwigses, who served a similar comic relief role. I think it's because Mrs. Wackles has her head on a lot straighter than any Kenwigs parent. She knows Swiveler needs to be tested, so she sets the test. I'm curious whether Sophie will undermine her in future chapters, though.

Tristram wrote: "Be a good girl, Nelly, a very good girl, and see if one of these days you don't come to be Mrs Quilp of Tower Hill.’”

Tristram wrote: "Be a good girl, Nelly, a very good girl, and see if one of these days you don't come to be Mrs Quilp of Tower Hill.’”What does this tell you about Quilp? .."

It tells us that Quilp is a creepy old git, and that Nell has good reason to cry if that's in her future.

Tristram wrote: " oh hear me pray that we may beg, or work in open roads or fields, to earn a scanty living, rather than live as we do now.’

Tristram wrote: " oh hear me pray that we may beg, or work in open roads or fields, to earn a scanty living, rather than live as we do now.’‘Nelly!’ said the old man.”

This seems to be the major point of discord between Nell and her grandfather, and it is undoubtedly the cause for what is going to happen to the two of them, the inciting moment of the plot. What does it tell you about the two characters, though?.."

More recurring themes... this reminds me so much of Ada and Richard in Bleak House - Ada just wanting to live a happy, if destitute, life with Richard, and Richard turning the court case and promise of money into an addiction. Can we use their fates to predict what will happen with Nell and Grandfather?

Gambling has never held any interest for me, and the couple of times I visited casinos I thought they were sad places and a waste of time and money. So I really don't get gambling addictions, but it seems that Trent must have one. That elusive jackpot is always just a game away.

Tristram wrote: "Who would you bank your money on in a fistfight between Swiveller and Quilp?..."

Tristram wrote: "Who would you bank your money on in a fistfight between Swiveller and Quilp?..."Swiveller's a lover, not a fighter, and he loves himself most of all ;-) The passage you quoted about him keeping a list of streets he had to avoid tells us that he's a bit of a lazy coward, and not interested in confrontation. Quilp, despite his diminutive stature, has a mean streak and no qualms about using violence as a means of persuasion. The missing link in this battle is Fred. He's a manipulative sneak, and while he might not want to get his own hands dirty, I doubt Fred would hesitate to throw Dick under the bus to attain his goals.

Julie wrote: "I am wondering what the backstory on Fred is, and what it means that Quilp placed him as a sailor. Was this to benefit Fred, or his grandfather? Why is Fred so miserable a person, and what is the mysterious fate of his and Nell's mother?..."

Julie wrote: "I am wondering what the backstory on Fred is, and what it means that Quilp placed him as a sailor. Was this to benefit Fred, or his grandfather? Why is Fred so miserable a person, and what is the mysterious fate of his and Nell's mother?..."Excellent questions, Julie. I'd forgotten the bit about Quilp getting Fred work. His tentacles are all over this family.

Fred and Grandfather are, perhaps surprisingly, birds of a feather. They both are looking for a windfall, and can't be content to come by it through daily work. The same can be said for Dick. Money for nothing. Fred believes he's entitled to it for some unfathomable reason; GF has convinced himself that gambling IS work, and he's just waiting for that big paycheck; Lazy Dick is willing to go into debt and marry for money. This hope to fall into money is emerging as a main theme of TOCS.

Tristram wrote: "...her grandfather feels betrayed by Kit for something the boy has done, thus severing all ties between the Trents and himself, and Little Nell has come to tell Kit herself, feeling that it would be too cruel to let somebody else carry that final message...."

Tristram wrote: "...her grandfather feels betrayed by Kit for something the boy has done, thus severing all ties between the Trents and himself, and Little Nell has come to tell Kit herself, feeling that it would be too cruel to let somebody else carry that final message...."Poor Kit! Dickens has used chapter 9 to establish Kit as a loyal, trustworthy, and selfless son, brother, and friend, only to have the girl he loves return his affections with false accusations and severed ties. I haven't warmed up to Nell yet (though I've not yet gone over to the Grump side, either). But Dickens saw to it that I loved Kit. It's as bad as kicking a loyal dog.

Mary Lou wrote: "It tells us that Quilp is a creepy old git, and that Nell has good reason to cry if that's in her future."

Yes, and it also tells us that Quilp apparently has an idea of how long his wife is till going to live, and I wonder why he knows this so well ;-)

It's also a strange kind of wooing to tell prospective wife number 2 that number 1's sojourn in this vale of tears will not be a long one any more. Even Henry VIII. was probably more felicitous in making advances ...

Yes, and it also tells us that Quilp apparently has an idea of how long his wife is till going to live, and I wonder why he knows this so well ;-)

It's also a strange kind of wooing to tell prospective wife number 2 that number 1's sojourn in this vale of tears will not be a long one any more. Even Henry VIII. was probably more felicitous in making advances ...

Mary Lou wrote: "I haven't warmed up to Nell yet (though I've not yet gone over to the Grump side, either)."

It's actually called the Grump side only by its opponents. We call ourselves "the perceptive, well-versed in the ways of the world people who simply cannot put up with sappy characters in fiction."

And yes, Grandfather Trent is a very thankless egoist, which is shown in his quickly wanting some scapegoat he could blame for Quilp's knowledge of his plans. It is a pity Little Nell should be so much under the grandfather's spell that she is ready to break all ties with Kit even though her better judgment tells her that Kit would never have betrayed them. It is also bewildering to see how the old man has convinced himself that gambling away money he has never earned is work. His aim, to place Nell above all worldly cares, sounds noble but it would be more sensible to lay some money by and put the Old Curiosity Shop on steady feet.

It's actually called the Grump side only by its opponents. We call ourselves "the perceptive, well-versed in the ways of the world people who simply cannot put up with sappy characters in fiction."

And yes, Grandfather Trent is a very thankless egoist, which is shown in his quickly wanting some scapegoat he could blame for Quilp's knowledge of his plans. It is a pity Little Nell should be so much under the grandfather's spell that she is ready to break all ties with Kit even though her better judgment tells her that Kit would never have betrayed them. It is also bewildering to see how the old man has convinced himself that gambling away money he has never earned is work. His aim, to place Nell above all worldly cares, sounds noble but it would be more sensible to lay some money by and put the Old Curiosity Shop on steady feet.

Tristram wrote: "It is a pity Little Nell should be so much under the grandfather's spell that she is ready to break all ties with Kit even though her better judgment tells her that Kit would never have betrayed them. ."

Tristram wrote: "It is a pity Little Nell should be so much under the grandfather's spell that she is ready to break all ties with Kit even though her better judgment tells her that Kit would never have betrayed them. ."It always kind of shocks me what a premium the Victorians place on womanly obedience. I wonder how far it goes--clearly Nell believes she's doing the wrong thing in carrying on with the Kit ban, but are we supposed to admire her because she defers to her grandfather even when he's wrong and both she and we know it? Or are we supposed to be rooting for her to rebel?

Julie wrote: "...what a premium the Victorians place on womanly obedience..."

Julie wrote: "...what a premium the Victorians place on womanly obedience..."I agree in theory (and certainly this shows in the Quilp marriage), but in Nell's defense, this isn't just womanly obedience; this would fall under the fourth commandment of honoring your parents (or grandparents in this case). The gender disparity on top of the expectation that children obey their elders is a double-whammy for Nell and Kit.

Julie wrote: "are we supposed to admire her because she defers to her grandfather even when he's wrong and both she and we know it? Or are we supposed to be rooting for her to rebel?..."

Looking at it from a fourth commandment perspective, I suppose my hope would be that Nell would seek the truth and be able to use her powers of persuasion to redeem Kit in her grandfather's eyes.

Mary Lou wrote: "I agree in theory (and certainly this shows in the Quilp marriage), but in Nell's defense, this isn't just womanly obedience; this would fall under the fourth commandment of honoring your parents (or grandparents in this case)."

Mary Lou wrote: "I agree in theory (and certainly this shows in the Quilp marriage), but in Nell's defense, this isn't just womanly obedience; this would fall under the fourth commandment of honoring your parents (or grandparents in this case)."That's a good point, and now I'm thinking of Oliver's (view spoiler)

Now I'm trying to think of any heroic Dickens children who are rebels at all.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

It seems that after the retirement of the first-person narrator from the story, events unfold more quickly and there is more opportunity for humour to show its motley head. The l..."

Beneath the tears of Nell we find a very young girl. On the one hand her own grandfather shows little love towards her. Nell’s late night walks to Quilp’s residence to fulfill her grandfather’s selfish requests are thoughtless on Old Trent’s part. On the other hand, we have a grotesque dwarf discussing the possible early death of his wife coupled with his aggressive sexual suggestions of marriage to Nell. What should she do? How can she maintain her innocence?

Perhaps we should see Nell’s innocence as her strength. If she actually knew what was going on around her and being said to her Nell might as well shed her innocence and deploy a callousness that would serve as a way to survive.

To this point in the novel her innocence is her strength. She is the archetype of the innocent child, the infant.

It seems that after the retirement of the first-person narrator from the story, events unfold more quickly and there is more opportunity for humour to show its motley head. The l..."

Beneath the tears of Nell we find a very young girl. On the one hand her own grandfather shows little love towards her. Nell’s late night walks to Quilp’s residence to fulfill her grandfather’s selfish requests are thoughtless on Old Trent’s part. On the other hand, we have a grotesque dwarf discussing the possible early death of his wife coupled with his aggressive sexual suggestions of marriage to Nell. What should she do? How can she maintain her innocence?

Perhaps we should see Nell’s innocence as her strength. If she actually knew what was going on around her and being said to her Nell might as well shed her innocence and deploy a callousness that would serve as a way to survive.

To this point in the novel her innocence is her strength. She is the archetype of the innocent child, the infant.

Tristram wrote: "When Quilp takes his leave, he is watched by someone who has also witnessed his entering the house. This someone, it quickly turns out, is no one else but Kit, who, knowing that Little Nell is ofte..."

Nell has three possible courtiers. Quilp anticipates his wife’s death. His marriage to Nell would be for his own advantage, both financially and sexually. Fred encourages Richard Swiveller to consider Nell as a wife. This would lead to both Fred and Swiveller gaining access to Fred’s grandfather’s money. Only Kit would marry Nell for reasons of the heart.

Dickens has already established that Kit feels very protective of Nell, is well-grounded as a family oriented individual, and is perfectly honest. There is, however, something wrong and Kit is no longer welcome in the Trent home. Thus, the faithful companion of Nell is rejected from the home and external elements with self-interest in their hearts are allowed into the home.

Nell has three possible courtiers. Quilp anticipates his wife’s death. His marriage to Nell would be for his own advantage, both financially and sexually. Fred encourages Richard Swiveller to consider Nell as a wife. This would lead to both Fred and Swiveller gaining access to Fred’s grandfather’s money. Only Kit would marry Nell for reasons of the heart.

Dickens has already established that Kit feels very protective of Nell, is well-grounded as a family oriented individual, and is perfectly honest. There is, however, something wrong and Kit is no longer welcome in the Trent home. Thus, the faithful companion of Nell is rejected from the home and external elements with self-interest in their hearts are allowed into the home.

Chapter 8:

Chapter 8:I like how Dick ordered take-out from a restaurant and had it delivered to his house. I didn't know you could do that in Victorian times. What does it mean to "dispatch a message" to an eating-house? I don't think they had phones back then. I also found it interesting how the delivery guy returned for the empty plates and dishes. No styrofoam containers!

I love the picture that Dickens painted of Kit and his family. They seem like humble, good-hearted people, and the baby in the clothes basket was a cute detail. I wonder what happened to Kit's dad?

I love the picture that Dickens painted of Kit and his family. They seem like humble, good-hearted people, and the baby in the clothes basket was a cute detail. I wonder what happened to Kit's dad?

I'm not impressed by Grandpa Trent either. All that effort he put into gambling he could have put into his shop to make it succeed. He's also a bad judge of character to do business with Quilp (a guy who growls and bites people) and to misjudge Kit, a good boy.

I'm not impressed by Grandpa Trent either. All that effort he put into gambling he could have put into his shop to make it succeed. He's also a bad judge of character to do business with Quilp (a guy who growls and bites people) and to misjudge Kit, a good boy.It's interesting how Quilp asked Trent, "Who do you think did it?" and Trent filled in the blank with his own wrong assumption: Kit. All of his upset is based on an assumption, not a fact.

I'm surprised Fred is so ignorant about his grandfather's finances. All he had to do was question Nell or pay more attention to the worrying. I think the grandfather even said he was poor, but Fred didn't believe it. Fred is setting Dick up to marry his sister based on an assumption. Ignorance and assumption seem to be themes here.

Chapter 6

Chapter 6While reading this chapter, Alice and Wonderland popped into mind. It must have had something to do with Nell's age, Alice's age, Quilp's "fondness" for Nell, Lewis Carroll's putative "fondness" for Alice, and the general grotesquery of the stories. I wonder if OCS gave Carroll the germ of an idea.

Nell in this chapter is definitely not a child. More than the narrator has changed. Nell's grown 5 - 7 years since chapter 5.

Looks like grandpa doesn't care as much for his granddaughter as he claims. I wouldn't be sending Nell to Quilp, especially if I had Kit to do it.

Standing on his head to revenge himself against Quilp doesn't do it for me. Sorry.

Condign? Condign? Condign? Please, Sir Charles, let that be the end of the vocabulary test.

Tristram wrote: "I was especially taken aback by this passage – after all, Nell is 14 years old:

Tristram wrote: "I was especially taken aback by this passage – after all, Nell is 14 years old:” ‘How should you like to be my number two, Nelly?’

‘To be what, sir?’

‘My number two, Nelly, my second, my Mrs Quilp,’ said the dwarf.

"

And your mind wanders after reading this, and you think grandpa owes Quilp money and needs more, and Quilp will force him to repay by ransoming Nell.

Anyone besides me originally think this too?

Chapter 6 Continued

Chapter 6 ContinuedQuilp knows he's grotesque, a carnival attraction, and that no one is going to pay attention to him unless he forces them to pay attention. I can imagine what it was like for him growing up, and how that created the adult that he is. I can certainly see how his heartlessness was born out of the equal heartlessness of those who bullied him when young. For sure he knows the only way he will get things in this world that come easy to other men is through deceit, leverage, and being meaner than anyone else in the room.

Money is power. Having people owe you money is greater power.

Dickens has certainly taken a shine to money lenders and debt holders. You can see the effect his father's jailing had on him.

Dickens has certainly taken a shine to money lenders and debt holders. You can see the effect his father's jailing had on him.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "I was especially taken aback by this passage – after all, Nell is 14 years old:

” ‘How should you like to be my number two, Nelly?’

‘To be what, sir?’

‘My number two, Nelly, my ..."

Nell’s grandfather is a desperate man, and men in debt have been known to do horrendous deeds. If we look back to NN, Madeline Bray’s father did nudge towards your point.

If we accept the premise then both Nell’s grandfather and Quilp become even more odious.

In next weeks postings I will take up your point in more depth.

” ‘How should you like to be my number two, Nelly?’

‘To be what, sir?’

‘My number two, Nelly, my ..."

Nell’s grandfather is a desperate man, and men in debt have been known to do horrendous deeds. If we look back to NN, Madeline Bray’s father did nudge towards your point.

If we accept the premise then both Nell’s grandfather and Quilp become even more odious.

In next weeks postings I will take up your point in more depth.

It is interesting that some of you should start wondering what made Quilp become such a mean-spirited, dyed-in-the-wood villain. Where does his lust for power and his delight in humiliating, intimidating and scaring other people come from? Where does his short temper and his readiness to resort to physical violence stem from?

I usually try to come up with a background story for most villains I read of, and very often Dickens clearly invites us to do this and think this way. However, in the case of Quilp I never had the impression he wanted us to look behind the ugly canvas and imagine how this character came to be what he is because Quilp, more so than Ralph Nickleby, Fagin, Sikes, and all the other Dickens scoundrels, is just Evil Personified. He revels in evil and in ugliness, and I would eben be able to imagine that he came into the world like this - although this idea is contrary to modern conceptions. Apart from Blandois (or whatever his name was, you know the evil Frenchman in Little Dorrit), I find no other character in Dickens that I could have taken for the Devil himself.

Maybe, it is because of the fairy tale character that TOCS possesses, but, as I said, to me, there is no story behind Quilp ... Am I alone with that sentiment?

I usually try to come up with a background story for most villains I read of, and very often Dickens clearly invites us to do this and think this way. However, in the case of Quilp I never had the impression he wanted us to look behind the ugly canvas and imagine how this character came to be what he is because Quilp, more so than Ralph Nickleby, Fagin, Sikes, and all the other Dickens scoundrels, is just Evil Personified. He revels in evil and in ugliness, and I would eben be able to imagine that he came into the world like this - although this idea is contrary to modern conceptions. Apart from Blandois (or whatever his name was, you know the evil Frenchman in Little Dorrit), I find no other character in Dickens that I could have taken for the Devil himself.

Maybe, it is because of the fairy tale character that TOCS possesses, but, as I said, to me, there is no story behind Quilp ... Am I alone with that sentiment?

I think the story behind Quilp is his physical attributes. He is a man despised for the way he looks, so he despises right back.

I think the story behind Quilp is his physical attributes. He is a man despised for the way he looks, so he despises right back.

Tristram wrote: "It is interesting that some of you should start wondering what made Quilp become such a mean-spirited, dyed-in-the-wood villain. Where does his lust for power and his delight in humiliating, intimi..."

Hi Tristram

Yes. Quilp does come from some place that may never be explained. In terms of our placing him within the matrix of characters I see him as the Trickster, the Devil figure. He is the embodiment of evil within the framework of the fairy tale. With Nell as the Innocent, the Virgin, our cast of archetypes is beginning to expand nicely.

Hi Tristram

Yes. Quilp does come from some place that may never be explained. In terms of our placing him within the matrix of characters I see him as the Trickster, the Devil figure. He is the embodiment of evil within the framework of the fairy tale. With Nell as the Innocent, the Virgin, our cast of archetypes is beginning to expand nicely.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I think the story behind Quilp is his physical attributes. He is a man despised for the way he looks, so he despises right back."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I think the story behind Quilp is his physical attributes. He is a man despised for the way he looks, so he despises right back."I don't know. I guess Kit does call him ugly, but he's so awful and invulnerable that it kind of seems beyond explanation. As Tristram says, he comes into the world evil and his appearance is presented as a symptom and sign of his character, not its cause. It does feel more archetypical and less psychological in its logic.

I think this is why also I find Quilp less upsetting to read about than the grandfather--Quilp doesn't feel real--he's almost comic. But I do feel I know a lot of people who ruin themselves and others like Grandfather Trent.

We meet him as an adult with full set of armor. How can we say he came into this world this way when we know nothing of his childhood? We do, though, know how children treat children who look like he looks.

We meet him as an adult with full set of armor. How can we say he came into this world this way when we know nothing of his childhood? We do, though, know how children treat children who look like he looks.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "We meet him as an adult with full set of armor. How can we say he came into this world this way when we know nothing of his childhood? We do, though, know how children treat children who look like ..."

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "We meet him as an adult with full set of armor. How can we say he came into this world this way when we know nothing of his childhood? We do, though, know how children treat children who look like ..."Yes, this is plausible, and if we come across a section later where Quilp or the never-reticent narrator monologues about the miseries of a world that could treat a person the way it treated Quilp in childhood, I'm on board. But as-is, I'm not getting a sense that this is the point the character is here to illustrate.

Tristram wrote: "What do you think of young Richard Swiveller, though?"

Tristram wrote: "What do you think of young Richard Swiveller, though?"Swiveller is lots of fun, and fun is needed in this story. Passages I locked onto that show his personality.

Regarding the bedpost:

To be the friend of Swiveller you must reject all circumstantial evidence, all reason, observation, and experience, and repose a blind belief in the bookcase. It was his pet weakness, and he cherished it.

Then there is the likeness between Fred and Nell that Dick expounds upon, basically telling us Fred is one ugly dude:

Why certainly, replied Dick, I must say for her that there's not any very strong likeness between her and you.

And lastly he comments on the well being of the marriage to Nell, if there is no dowry or inheritance, Fred proposes:

A family and an annual income of nothing, to keep 'em on,'...

And then goes about breaking his relationship with his squeeze. This guy is hilarious.

So why is Kit with Nell on this visit to Quilp anyway? He wasn't with her the last time, did dear old Grandfather suddenly ask Kit to accompany her because he has seen the light after Master Humphrey has confronted him with his letting Nell wander through the city by herself. Is it safer to wander around in cities then as now, or now as then? I don't know, I can't imagine what would get me to a city larger than Harrisburg Pennsylvania and I wouldn't walk around in it after dark or before dark for that matter. I'll take the Amish any day. And he knows good old grandpa leaves every night, does he know where he goes? You would think he would by now, I doubt that would matter, but you would think he would have figured it out. And since he's watching Little Nell, why doesn't he always follow her when she's sent out at night?

I adore Dick Swiveller just the way he is, almost. The first time I laughed is when I met Dick Swiveller. I can't wait to see more of him. Those apartments of his being one room reminded me of a friend who moved to another state and called me when he found a new home, "an apartment". It is great, he told me, the sofa is against the wall across from the window and he can sit there and look out at the scene in front of him. He also had a "chair" on the other side of the room and the television next to it. As for the bedroom, his comment on the bed was almost the same as to the sofa, the I can look out the window comment. He then told me the kitchen has a little table perfect for one or two, and the kitchen is the perfect size for a small refrigerator and microwave. He didn't mention a bathroom and by this time I was afraid there wasn't one, so I looked up the place on the internet and it looked like a one story motel. All the rooms, including his, could be found in any Motel 6 or Comfort Inn, or the like, you've ever seen.

Mrs. Wackles want to get her daughter married. Sophia's sisters want her to get married, Sophia wants to get married, it seems to me to be the reason for the big making Dick jealous plan. I'm not sure why she wanted Dick over Mr. Cheggs, it seems like a safer bet to go with Cheggs, but Dick has been picked out and Dick is the one they went for. Dickens mothers seem to do that, and I think that's some of what got Mrs. Quilp to marry him, I can't imagine her falling in love with him on first sight and second and third sight of him would have cured her of that. We'll have another mother in a later book who does the same thing. That's what I think anyway, Mr. Wackles is dead, so they have to find a new man to take his place and take care of them. Now that she's married him she seems to have grown to worship him in her own terrified way. I guess you can get used to anything.

I was wondering why Quilp married poor Mrs. Quilp anyway. She didn't bring money with her, he isn't thrilled with his mother-in-law, she doesn't have some kind of well known family that would bring him up in society, he doesn't love her, he doesn't take her out around people just to show how someone like him could get a young, beautiful wife. It appears he married her just to torture her. I can't stand the guy, I've decided the reason he likes jumping on furniture, sitting on the back of chairs and acting monkey like is because he isn't really human.

Why can I say about Grandfather? The same thing I've always said, he's an ass, if he ever gets over being one it's too late for me already, my opinion of him won't change. This guy thinks only of himself all the time. Maybe once he got the brilliant idea that if he gambles he will make money for Little Nell, I can't imagine how, but maybe that was his idea, but he stopped going for that reason long ago. Whether he really believes it's for Nell I don't know.

I adore Dick Swiveller just the way he is, almost. The first time I laughed is when I met Dick Swiveller. I can't wait to see more of him. Those apartments of his being one room reminded me of a friend who moved to another state and called me when he found a new home, "an apartment". It is great, he told me, the sofa is against the wall across from the window and he can sit there and look out at the scene in front of him. He also had a "chair" on the other side of the room and the television next to it. As for the bedroom, his comment on the bed was almost the same as to the sofa, the I can look out the window comment. He then told me the kitchen has a little table perfect for one or two, and the kitchen is the perfect size for a small refrigerator and microwave. He didn't mention a bathroom and by this time I was afraid there wasn't one, so I looked up the place on the internet and it looked like a one story motel. All the rooms, including his, could be found in any Motel 6 or Comfort Inn, or the like, you've ever seen.

Mrs. Wackles want to get her daughter married. Sophia's sisters want her to get married, Sophia wants to get married, it seems to me to be the reason for the big making Dick jealous plan. I'm not sure why she wanted Dick over Mr. Cheggs, it seems like a safer bet to go with Cheggs, but Dick has been picked out and Dick is the one they went for. Dickens mothers seem to do that, and I think that's some of what got Mrs. Quilp to marry him, I can't imagine her falling in love with him on first sight and second and third sight of him would have cured her of that. We'll have another mother in a later book who does the same thing. That's what I think anyway, Mr. Wackles is dead, so they have to find a new man to take his place and take care of them. Now that she's married him she seems to have grown to worship him in her own terrified way. I guess you can get used to anything.

I was wondering why Quilp married poor Mrs. Quilp anyway. She didn't bring money with her, he isn't thrilled with his mother-in-law, she doesn't have some kind of well known family that would bring him up in society, he doesn't love her, he doesn't take her out around people just to show how someone like him could get a young, beautiful wife. It appears he married her just to torture her. I can't stand the guy, I've decided the reason he likes jumping on furniture, sitting on the back of chairs and acting monkey like is because he isn't really human.

Why can I say about Grandfather? The same thing I've always said, he's an ass, if he ever gets over being one it's too late for me already, my opinion of him won't change. This guy thinks only of himself all the time. Maybe once he got the brilliant idea that if he gambles he will make money for Little Nell, I can't imagine how, but maybe that was his idea, but he stopped going for that reason long ago. Whether he really believes it's for Nell I don't know.

Little Nell stood timidly by, with her eyes raised to the countenance of Mr Quilp as he read the letter.

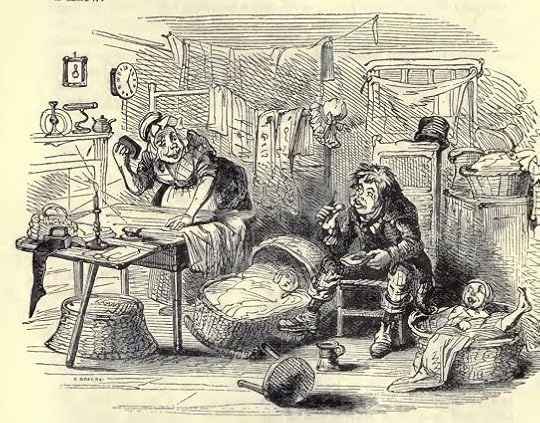

Chapter 6

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Little Nell stood timidly by, with her eyes raised to the countenance of Mr Quilp as he read the letter, plainly showing by her looks that while she entertained some fear and distrust of the little man, she was much inclined to laugh at his uncouth appearance and grotesque attitude. And yet there was visible on the part of the child a painful anxiety for his reply, and consciousness of his power to render it disagreeable or distressing, which was strongly at variance with this impulse and restrained it more effectually than she could possibly have done by any efforts of her own.

That Mr Quilp was himself perplexed, and that in no small degree, by the contents of the letter, was sufficiently obvious. Before he had got through the first two or three lines he began to open his eyes very wide and to frown most horribly, the next two or three caused him to scratch his head in an uncommonly vicious manner, and when he came to the conclusion he gave a long dismal whistle indicative of surprise and dismay. After folding and laying it down beside him, he bit the nails of all of his ten fingers with extreme voracity; and taking it up sharply, read it again. The second perusal was to all appearance as unsatisfactory as the first, and plunged him into a profound reverie from which he awakened to another assault upon his nails and a long stare at the child, who with her eyes turned towards the ground awaited his further pleasure.

‘Halloa here!’ he said at length, in a voice, and with a suddenness, which made the child start as though a gun had been fired off at her ear. ‘Nelly!’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Do you know what’s inside this letter, Nell?’

‘No, sir!’

‘Are you sure, quite sure, quite certain, upon your soul?’

‘Quite sure, sir.’

‘Do you wish you may die if you do know, hey?’ said the dwarf.

‘Indeed I don’t know,’ returned the child.

‘Well!’ muttered Quilp as he marked her earnest look. ‘I believe you. Humph! Gone already? Gone in four-and-twenty hours! What the devil has he done with it, that’s the mystery!’

This reflection set him scratching his head and biting his nails once more. While he was thus employed his features gradually relaxed into what was with him a cheerful smile, but which in any other man would have been a ghastly grin of pain, and when the child looked up again she found that he was regarding her with extraordinary favour and complacency.

‘You look very pretty to-day, Nelly, charmingly pretty. Are you tired, Nelly?’

‘No, sir. I’m in a hurry to get back, for he will be anxious while I am away.’

‘There’s no hurry, little Nell, no hurry at all,’ said Quilp. ‘How should you like to be my number two, Nelly?’

‘To be what, sir?’

‘My number two, Nelly, my second, my Mrs Quilp,’ said the dwarf.

The child looked frightened, but seemed not to understand him, which Mr Quilp observing, hastened to make his meaning more distinctly.

‘To be Mrs Quilp the second, when Mrs Quilp the first is dead, sweet Nell,’ said Quilp, wrinkling up his eyes and luring her towards him with his bent forefinger, ‘to be my wife, my little cherry-cheeked, red-lipped wife. Say that Mrs Quilp lives five year, or only four, you’ll be just the proper age for me. Ha ha! Be a good girl, Nelly, a very good girl, and see if one of these days you don’t come to be Mrs Quilp of Tower Hill.’

So far from being sustained and stimulated by this delightful prospect, the child shrank from him in great agitation, and trembled violently. Mr Quilp, either because frightening anybody afforded him a constitutional delight, or because it was pleasant to contemplate the death of Mrs Quilp number one, and the elevation of Mrs Quilp number two to her post and title, or because he was determined from purposes of his own to be agreeable and good-humoured at that particular time, only laughed and feigned to take no heed of her alarm.

Commentary:

Although many of Browne's early cuts for The Old Curiosity Shop are somewhat caricatured, comic portrayals of characters, his Quilp is a notable creation. Less has been said in favor of his Nell, but compared to Cattermole's, who is either a wax doll or barely visible, Browne makes us believe in the "cherry-cheeked, red-lipped" child Quilp describes so lecherously, and yet the artist never loses the pathos of Nell's situation — indeed, it could be argued that Phiz's Nell is more flesh and blood than Dickens'. Phiz seems to have transcended the rigidity of figure which characterized his virtuous females in Nicholas Nickleby.

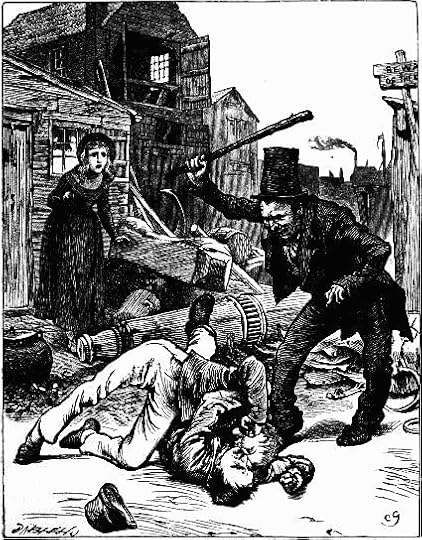

"I'll beat you to pulp, you dogs"

Chapter 6

Charles Green

Text Illustrated:

With that, Mr Quilp suffered himself to roll gradually off the desk until his short legs touched the ground, when he got upon them and led the way from the counting-house to the wharf outside, when the first objects that presented themselves were the boy who had stood on his head and another young gentleman of about his own stature, rolling in the mud together, locked in a tight embrace, and cuffing each other with mutual heartiness.

‘It’s Kit!’ cried Nelly, clasping her hand, ‘poor Kit who came with me! Oh, pray stop them, Mr Quilp!’

‘I’ll stop ‘em,’ cried Quilp, diving into the little counting-house and returning with a thick stick, ‘I’ll stop ‘em. Now, my boys, fight away. I’ll fight you both. I’ll take both of you, both together, both together!’

With which defiances the dwarf flourished his cudgel, and dancing round the combatants and treading upon them and skipping over them, in a kind of frenzy, laid about him, now on one and now on the other, in a most desperate manner, always aiming at their heads and dealing such blows as none but the veriest little savage would have inflicted. This being warmer work than they had calculated upon, speedily cooled the courage of the belligerents, who scrambled to their feet and called for quarter.

‘I’ll beat you to a pulp, you dogs,’ said Quilp, vainly endeavoring to get near either of them for a parting blow. ‘I’ll bruise you until you’re copper-coloured, I’ll break your faces till you haven’t a profile between you, I will.’`

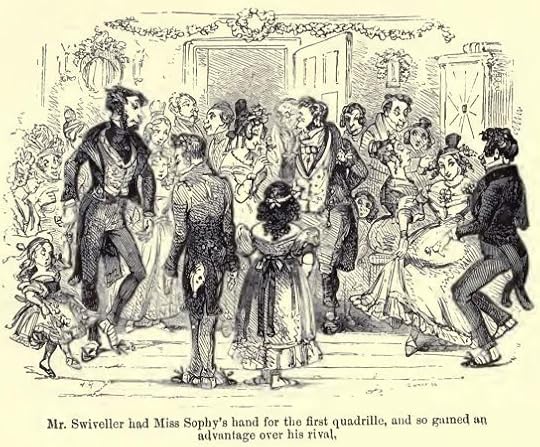

Chapter 8

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

However, Mr Swiveller had Miss Sophy’s hand for the first quadrille (country-dances being low, were utterly proscribed) and so gained an advantage over his rival, who sat despondingly in a corner and contemplated the glorious figure of the young lady as she moved through the mazy dance. Nor was this the only start Mr Swiveller had of the market-gardener, for determining to show the family what quality of man they trifled with, and influenced perhaps by his late libations, he performed such feats of agility and such spins and twirls as filled the company with astonishment, and in particular caused a very long gentleman who was dancing with a very short scholar, to stand quite transfixed by wonder and admiration. Even Mrs Wackles forgot for the moment to snub three small young ladies who were inclined to be happy, and could not repress a rising thought that to have such a dancer as that in the family would be a pride indeed.

At this momentous crisis, Miss Cheggs proved herself a vigourous and useful ally, for not confining herself to expressing by scornful smiles a contempt for Mr Swiveller’s accomplishments, she took every opportunity of whispering into Miss Sophy’s ear expressions of condolence and sympathy on her being worried by such a ridiculous creature, declaring that she was frightened to death lest Alick should fall upon, and beat him, in the fulness of his wrath, and entreating Miss Sophy to observe how the eyes of the said Alick gleamed with love and fury; passions, it may be observed, which being too much for his eyes rushed into his nose also, and suffused it with a crimson glow.

‘You must dance with Miss Cheggs,’ said Miss Sophy to Dick Swiviller, after she had herself danced twice with Mr Cheggs and made great show of encouraging his advances. ‘She’s a nice girl—and her brother’s quite delightful.’

‘Quite delightful, is he?’ muttered Dick. ‘Quite delighted too, I should say, from the manner in which he’s looking this way.’

Here Miss Jane (previously instructed for the purpose) interposed her many curls and whispered her sister to observe how jealous Mr Cheggs was.

‘Jealous! Like his impudence!’ said Richard Swiviller.

‘His impudence, Mr Swiviller!’ said Miss Jane, tossing her head. ‘Take care he don’t hear you, sir, or you may be sorry for it.’

‘Oh, pray, Jane—’ said Miss Sophy.

‘Nonsense!’ replied her sister. ‘Why shouldn’t Mr Cheggs be jealous if he likes? I like that, certainly. Mr Cheggs has a good a right to be jealous as anyone else has, and perhaps he may have a better right soon if he hasn’t already. You know best about that, Sophy!’

Though this was a concerted plot between Miss Sophy and her sister, originating in humane intentions and having for its object the inducing Mr Swiviller to declare himself in time, it failed in its effect; for Miss Jane being one of those young ladies who are prematurely shrill and shrewish, gave such undue importance to her part that Mr Swiviller retired in dudgeon, resigning his mistress to Mr Cheggs and conveying a defiance into his looks which that gentleman indignantly returned.

Commentary:

The Old Curiosity Shop evolved as a serial in Dickens’s own threepenny weekly miscellany, Master Humphrey’s Clock, the pages of which it entirely took over from its ninth chapter until its completion.1 From the outset, a crucial element in Dickens’s vision for his periodical was that it should be enhanced by ‘woodcuts dropped into the text’, an idea to which he remained committed when the Clock became solely a vehicle first for the Shop, and then for Barnaby Rudge, with which it ended its run. Accordingly, 75 wood engravings (as they in fact were) were integrated with the text of the first story, and 76 with the second. George Cattermole produced 14 illustrations for the Shop, and 17 for Rudge, while Daniel Maclise and Samuel Williams provided just one apiece for the Shop, each featuring Nell, but Hablot K. Browne (Phiz) designed no fewer than 59 for each novel. He also drew every one of the periodical’s illuminated capital letters.

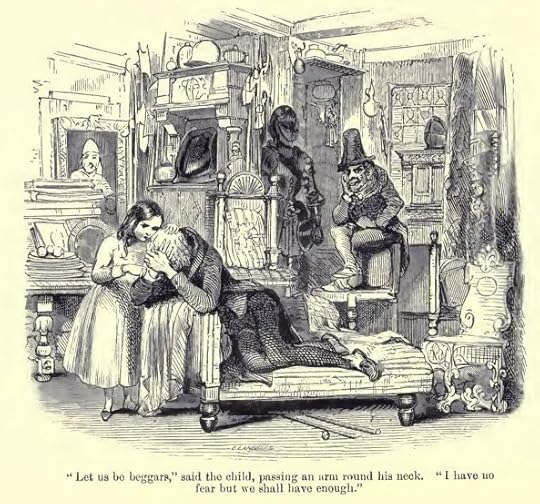

Little Nell as Comforter

Chapter 9

George Cattermole

Text Illustrated:

One night, the third after Nelly’s interview with Mrs Quilp, the old man, who had been weak and ill all day, said he should not leave home. The child’s eyes sparkled at the intelligence, but her joy subsided when they reverted to his worn and sickly face.

‘Two days,’ he said, ‘two whole, clear, days have passed, and there is no reply. What did he tell thee, Nell?’

‘Exactly what I told you, dear grandfather, indeed.’

‘True,’ said the old man, faintly. ‘Yes. But tell me again, Nell. My head fails me. What was it that he told thee? Nothing more than that he would see me to-morrow or next day? That was in the note.’

‘Nothing more,’ said the child. ‘Shall I go to him again to-morrow, dear grandfather? Very early? I will be there and back, before breakfast.’

The old man shook his head, and sighing mournfully, drew her towards him.

‘’Twould be of no use, my dear, no earthly use. But if he deserts me, Nell, at this moment—if he deserts me now, when I should, with his assistance, be recompensed for all the time and money I have lost, and all the agony of mind I have undergone, which makes me what you see, I am ruined, and—worse, far worse than that—have ruined thee, for whom I ventured all. If we are beggars—!’

‘What if we are?’ said the child boldly. ‘Let us be beggars, and be happy.’

‘Beggars—and happy!’ said the old man. ‘Poor child!’

‘Dear grandfather,’ cried the girl with an energy which shone in her flushed face, trembling voice, and impassioned gesture, ‘I am not a child in that I think, but even if I am, oh hear me pray that we may beg, or work in open roads or fields, to earn a scanty living, rather than live as we do now.’

‘Nelly!’ said the old man.

‘Yes, yes, rather than live as we do now,’ the child repeated, more earnestly than before. ‘If you are sorrowful, let me know why and be sorrowful too; if you waste away and are paler and weaker every day, let me be your nurse and try to comfort you. If you are poor, let us be poor together; but let me be with you, do let me be with you; do not let me see such change and not know why, or I shall break my heart and die. Dear grandfather, let us leave this sad place to-morrow, and beg our way from door to door.’

The old man covered his face with his hands, and hid it in the pillow of the couch on which he lay.

‘Let us be beggars,’ said the child passing an arm round his neck, ‘I have no fear but we shall have enough, I am sure we shall. Let us walk through country places, and sleep in fields and under trees, and never think of money again, or anything that can make you sad, but rest at nights, and have the sun and wind upon our faces in the day, and thank God together! Let us never set foot in dark rooms or melancholy houses, any more, but wander up and down wherever we like to go; and when you are tired, you shall stop to rest in the pleasantest place that we can find, and I will go and beg for both.’

The child’s voice was lost in sobs as she dropped upon the old man’s neck; nor did she weep alone.

These were not words for other ears, nor was it a scene for other eyes. And yet other ears and eyes were there and greedily taking in all that passed, and moreover they were the ears and eyes of no less a person than Mr Daniel Quilp, who, having entered unseen when the child first placed herself at the old man’s side, refrained—actuated, no doubt, by motives of the purest delicacy—from interrupting the conversation, and stood looking on with his accustomed grin. Standing, however, being a tiresome attitude to a gentleman already fatigued with walking, and the dwarf being one of that kind of persons who usually make themselves at home, he soon cast his eyes upon a chair, into which he skipped with uncommon agility, and perching himself on the back with his feet upon the seat, was thus enabled to look on and listen with greater comfort to himself, besides gratifying at the same time that taste for doing something fantastic and monkey-like, which on all occasions had strong possession of him. Here, then, he sat, one leg cocked carelessly over the other, his chin resting on the palm of his hand, his head turned a little on one side, and his ugly features twisted into a complacent grimace. And in this position the old man, happening in course of time to look that way, at length chanced to see him: to his unbounded astonishment.

Commentary:

Although the mode of illustration upon which Dickens had decided for his novel, the woodblock, offered the advantage of being printed with the text rather than on a separate page, it was time-consuming to execute so that a single illustrator — Hablot Knight Browne or "Phiz" had become his usual collaborator — would not be equal to the task. The collaborative team (or "Clock Works" as Dickens dubbed it) consisted of Samuel Williams (1788-1853) and Daniel Maclise (1807-1870) supporting the chief illustrators, George Cattermole (1800-1868) and Phiz. However, in the end the supporting artists contributed only a single plate each while Phiz contributed the designs for most of the plates and Cattermole contributed fourteen drawings for ten plates and tail-pieces.

Since Cattermole's strength lay in the depiction of architectural backdrops as opposed to character drawings, his plates are set largely indoors; his execution of the old curiosity itself is highly effective. With his antiquarian and architectural bent, Cattermole was the logical choice for executing what Valerie Lester Browne describes as the story's "loftier" subjects, including the highly emotional scene of Nell's death. Jane Rabb Cohen has described the scenes that Dickens allotted to Cattermole and Brown respectively as "picturesque" and "grotesque". Chapman and Hall published the first volume edition of The Old Curiosity Shop on 15 December 1841, priced at thirteen shillings and printed from the Clock's stereotype plates. It bore the title:

The Old Curiosity Shop.

A Tale.

By Charles Dickens.

With Illustrations

By

George Cattermole And Hablot K. Browne.

Complete In One Volume.

That Cattermole's name precedes Browne's may suggest that the older, more established artist was both Dickens's and the public's favourite at the time. It was not simply a strategy playing upon name recognition. Cohen states that Dickens deliberately placed Cattermole's name ahead of Browne's because he felt that "Cattermole's name would undoubtedly enhance the prestige of the undertaking". Alternatively, the wording may simply reflect that of the wrapper (see below) that Cattermole designed.

To his initial contribution of 61 illustrations Phiz subsequently added four "extra illustrations" for Chapman and Hall's first Cheap Edition of 1848.

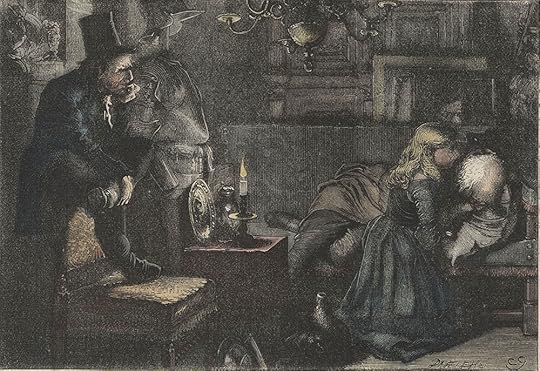

Little Nell and her Grandfather in the Old Curiosity Shop

Chapter 9

John Watkins Chapman

Text Illustrated:

One night, the third after Nelly’s interview with Mrs Quilp, the old man, who had been weak and ill all day, said he should not leave home. The child’s eyes sparkled at the intelligence, but her joy subsided when they reverted to his worn and sickly face.

‘Two days,’ he said, ‘two whole, clear, days have passed, and there is no reply. What did he tell thee, Nell?’

‘Exactly what I told you, dear grandfather, indeed.’

‘True,’ said the old man, faintly. ‘Yes. But tell me again, Nell. My head fails me. What was it that he told thee? Nothing more than that he would see me to-morrow or next day? That was in the note.’

‘Nothing more,’ said the child. ‘Shall I go to him again to-morrow, dear grandfather? Very early? I will be there and back, before breakfast.’

The old man shook his head, and sighing mournfully, drew her towards him.

‘’Twould be of no use, my dear, no earthly use. But if he deserts me, Nell, at this moment—if he deserts me now, when I should, with his assistance, be recompensed for all the time and money I have lost, and all the agony of mind I have undergone, which makes me what you see, I am ruined, and—worse, far worse than that—have ruined thee, for whom I ventured all. If we are beggars—!’

‘What if we are?’ said the child boldly. ‘Let us be beggars, and be happy.’

‘Beggars—and happy!’ said the old man. ‘Poor child!’

‘Dear grandfather,’ cried the girl with an energy which shone in her flushed face, trembling voice, and impassioned gesture, ‘I am not a child in that I think, but even if I am, oh hear me pray that we may beg, or work in open roads or fields, to earn a scanty living, rather than live as we do now.’

‘Nelly!’ said the old man.