The Old Curiosity Club discussion

The Old Curiosity Shop

>

TOCS Chapters 21-25

Chapter the Twenty-second

We begin the chapter with the Nubbles family preparing for Kit’s departure which is as grand a moment as “if he had been about to penetrate into the interior of Africa, or to take a cruise around the world.” Kit, in his farewell speech to his mother, assumes the role of both provider for the family and a son. Did you notice the shift in tone from the previous chapter? Dickens is a master of changing pace, tone, and mood between chapters and, indeed, within them. We have gone from snarling dogs and the ugliness of Quilp to the warm tones, mood and “contagious” laugh of the Nubbles family. And so off Kit goes to his new employers at Abel cottage.

Dickens describes the Garlands this way: “[t]o be sure, it was a beautiful little cottage with a thatched roof and little spires at the gable-ends ... . On one side was a little stable, just the size for the pony.” There were “white curtains ... and birds in cages that looked as bright as if they were made of gold [that] were singing at the windows.” All in all, this home is a direct opposite to that of Quilp, and thus, once again, we see how a person’s home and its structure directly parallels a character’s personality. The door is opened and Kit sees “a little servant-girl, very tidy, modest, and demure, but very pretty too.”

Thoughts

I have mentioned before that Dickens often changed his plans for characters and their fates in the midst of writing a novel. Sam Weller’s presence was increased in PP because of his popularity, Walter Gay from DS, who was doomed to die, ends up instead marrying Florence Dombey, and, of course, we have the two endings of GE. Let us take another look at Kit. Looking back, how has Dickens’s presentation of Kit changed from our first meeting with him in the novel? Looking into the future, what might Dickens’s plans be for Kit?

Birds, birds, birds. Here again we have a mention of birds. The Garland birds are happy in their state, they are as bright as gold, and are singing. If we look back to the earlier chapters and the mention of Nell’s bird, how can we compare and contrast the birds, their owners and the plot?

We read that the Garland’s servant’s name is Barbara. Kit is very observant of her, her work box, hymn-book and, well, everything about Barbara. As the chapter ends Kit is looking at Barbara, and Barbara is peeking at Kit, and they realize that each has been detected by the other. Well, I have to ask, what is happening between Kit and Barbara? How might this serve the future of the plot?

We begin the chapter with the Nubbles family preparing for Kit’s departure which is as grand a moment as “if he had been about to penetrate into the interior of Africa, or to take a cruise around the world.” Kit, in his farewell speech to his mother, assumes the role of both provider for the family and a son. Did you notice the shift in tone from the previous chapter? Dickens is a master of changing pace, tone, and mood between chapters and, indeed, within them. We have gone from snarling dogs and the ugliness of Quilp to the warm tones, mood and “contagious” laugh of the Nubbles family. And so off Kit goes to his new employers at Abel cottage.

Dickens describes the Garlands this way: “[t]o be sure, it was a beautiful little cottage with a thatched roof and little spires at the gable-ends ... . On one side was a little stable, just the size for the pony.” There were “white curtains ... and birds in cages that looked as bright as if they were made of gold [that] were singing at the windows.” All in all, this home is a direct opposite to that of Quilp, and thus, once again, we see how a person’s home and its structure directly parallels a character’s personality. The door is opened and Kit sees “a little servant-girl, very tidy, modest, and demure, but very pretty too.”

Thoughts

I have mentioned before that Dickens often changed his plans for characters and their fates in the midst of writing a novel. Sam Weller’s presence was increased in PP because of his popularity, Walter Gay from DS, who was doomed to die, ends up instead marrying Florence Dombey, and, of course, we have the two endings of GE. Let us take another look at Kit. Looking back, how has Dickens’s presentation of Kit changed from our first meeting with him in the novel? Looking into the future, what might Dickens’s plans be for Kit?

Birds, birds, birds. Here again we have a mention of birds. The Garland birds are happy in their state, they are as bright as gold, and are singing. If we look back to the earlier chapters and the mention of Nell’s bird, how can we compare and contrast the birds, their owners and the plot?

We read that the Garland’s servant’s name is Barbara. Kit is very observant of her, her work box, hymn-book and, well, everything about Barbara. As the chapter ends Kit is looking at Barbara, and Barbara is peeking at Kit, and they realize that each has been detected by the other. Well, I have to ask, what is happening between Kit and Barbara? How might this serve the future of the plot?

Chapter the Twenty-third

This is a very interesting chapter. It will advance the plot by letting us learn some of Quilp’s thoughts and plans, bring the dissolute trio of Quilp, Swiveller, and Frederick Trent together, and further evolve their characters. Let’s get to it.

We learn that the name of Quilp’s retreat is the Wilderness, and it is very different from Abel Cottage which we visited last chapter. Names do tell their own story in Dickens, be they the name of a person or the name of a dwelling. Dick Swiveller is in the process of “wending his way homewards after his fashion” and muttering about his sad past as a “miserable orphan.” He laments that he has now been “thrown upon the mercies of deluding dwarf.” From seemingly nowhere Swiveller hears a voice say “let me be a father to you.” It is Quilp’s voice. Quilp has been with Swiveller all the time. Dick has been drinking quite a lot! Quilp wants Dick to bring Trent to see him and assure Trent that Quilp is his friend. We must give Dick Swiveller some credit. He calls Quilp an “evil spirit” to which Quilp looks at Dick with a “mingled expression of cunning and dislike.” Once again, we see Quilp “wringing his hand.

The next morning Dick sees Trent and tells Fred that Quilp has “a queer way about him” and is “an artful dog.” Initially Fred can’t figure out Quilp’s interest in Dick, but soon sets his mind to the fact it involves money and since he too wants some of the grandfather’s alleged wealth decides to see Quilp. When Fred is with Quilp, Quilp sets about sowing seeds of discord between Fred, his grandfather and Nell. I have suggested earlier a touch of Shakespeare’s King Lear in this story. Now, I feel shades of Othello as Quilp, much like Iago, twist’s Fred’s mind against his own family.

Thoughts

How far off the mark am I on finding connections between this story and touches of Shakespeare?

Each time we have Quilp in the story it seems we have references to Quilp being a devil, an “evil spirit” and having “a queer way about him.” What might Dickens’s motivation for such a continuous series of unsettling references to Quilp be? In your estimation, how successful has Dickens been?

The next section of the chapter deals with a game of four-handed cribbage. It should come as no surprise that Quilp cheats, uses slight-of-hand, and kicks his partner under the table. We read that “the dwarf had eyes and ears; not occupied alone with what was passing above the table, but with signals that might be exchanged beneath it, which he laid all kinds of traps to detect.” Immediately after this game of cribbage, when he gets Fred’s undivided attention, Quilp says “[i]s it a bargain between us Fred? Shall [Dick Swiveller] marry little rosy Nell by-and-by?” We learn that neither Quilp or Fred know the whereabouts of Nell, but when they are discovered Quilp believes it will be easy for Dick to win Nell’s love in a year or two. Thus, with Nell married, Quilp and Fred will have access to the riches that Fred’s grandfather claims he does not have, but Quilp believes he does have.

Later Quilp overhears a conversation between Fred and Dick where they wonder what “enchantment” Quilp’s wife was under when she married Quilp. The chapter ends with Quilp reflecting that he is “a brute only in the gratification of his appetites.”

Thoughts

The four-handed cribbage game is an extended metaphor for what has occurred both in this chapter and in the preceding chapters that involve Quilp. What game is Quilp really playing? What are the strategies that he uses in order to win? Do you believe he will ever change his personality or his manner of dealing with people and situations? Why or why not?

The chapter ends with another reference to Quilp and his appetites. He smokes too much and he eats excessively. What might this extended metaphor of his consumptive appetites suggest?

What is your initial response to the deal that Fred and Quilp have made? What are the chances of its success?

To what extent do you feel Dick Swiveller is as evil-natured as his friends?

This is a very interesting chapter. It will advance the plot by letting us learn some of Quilp’s thoughts and plans, bring the dissolute trio of Quilp, Swiveller, and Frederick Trent together, and further evolve their characters. Let’s get to it.

We learn that the name of Quilp’s retreat is the Wilderness, and it is very different from Abel Cottage which we visited last chapter. Names do tell their own story in Dickens, be they the name of a person or the name of a dwelling. Dick Swiveller is in the process of “wending his way homewards after his fashion” and muttering about his sad past as a “miserable orphan.” He laments that he has now been “thrown upon the mercies of deluding dwarf.” From seemingly nowhere Swiveller hears a voice say “let me be a father to you.” It is Quilp’s voice. Quilp has been with Swiveller all the time. Dick has been drinking quite a lot! Quilp wants Dick to bring Trent to see him and assure Trent that Quilp is his friend. We must give Dick Swiveller some credit. He calls Quilp an “evil spirit” to which Quilp looks at Dick with a “mingled expression of cunning and dislike.” Once again, we see Quilp “wringing his hand.

The next morning Dick sees Trent and tells Fred that Quilp has “a queer way about him” and is “an artful dog.” Initially Fred can’t figure out Quilp’s interest in Dick, but soon sets his mind to the fact it involves money and since he too wants some of the grandfather’s alleged wealth decides to see Quilp. When Fred is with Quilp, Quilp sets about sowing seeds of discord between Fred, his grandfather and Nell. I have suggested earlier a touch of Shakespeare’s King Lear in this story. Now, I feel shades of Othello as Quilp, much like Iago, twist’s Fred’s mind against his own family.

Thoughts

How far off the mark am I on finding connections between this story and touches of Shakespeare?

Each time we have Quilp in the story it seems we have references to Quilp being a devil, an “evil spirit” and having “a queer way about him.” What might Dickens’s motivation for such a continuous series of unsettling references to Quilp be? In your estimation, how successful has Dickens been?

The next section of the chapter deals with a game of four-handed cribbage. It should come as no surprise that Quilp cheats, uses slight-of-hand, and kicks his partner under the table. We read that “the dwarf had eyes and ears; not occupied alone with what was passing above the table, but with signals that might be exchanged beneath it, which he laid all kinds of traps to detect.” Immediately after this game of cribbage, when he gets Fred’s undivided attention, Quilp says “[i]s it a bargain between us Fred? Shall [Dick Swiveller] marry little rosy Nell by-and-by?” We learn that neither Quilp or Fred know the whereabouts of Nell, but when they are discovered Quilp believes it will be easy for Dick to win Nell’s love in a year or two. Thus, with Nell married, Quilp and Fred will have access to the riches that Fred’s grandfather claims he does not have, but Quilp believes he does have.

Later Quilp overhears a conversation between Fred and Dick where they wonder what “enchantment” Quilp’s wife was under when she married Quilp. The chapter ends with Quilp reflecting that he is “a brute only in the gratification of his appetites.”

Thoughts

The four-handed cribbage game is an extended metaphor for what has occurred both in this chapter and in the preceding chapters that involve Quilp. What game is Quilp really playing? What are the strategies that he uses in order to win? Do you believe he will ever change his personality or his manner of dealing with people and situations? Why or why not?

The chapter ends with another reference to Quilp and his appetites. He smokes too much and he eats excessively. What might this extended metaphor of his consumptive appetites suggest?

What is your initial response to the deal that Fred and Quilp have made? What are the chances of its success?

To what extent do you feel Dick Swiveller is as evil-natured as his friends?

Chapter the Twenty-fourth

It has been a few chapters since we have been with Little Nell and her father. In the interim we have spent our time in London. Now, we again turn our attention to the countryside. After Nell and her father flee the race-ground they sit “upon the borders of a little wood” where “their resting-place was solitary and still.” Still, they can “distinguish the noise of the distant shouts, the hum of voices, and the beating of drums.” We learn that Mr Trent has a “disordered imagination.” To Nell, her greatest fear is to be separated from her grandfather. Nell reassures her grandfather that “[w]e are alone together, and may ramble where we like.” To reinforce this image we get ... wait for it ... a reference to a bird that, as Nell observes, is “flying into the wood, and leading the way for us to follow. You remember that we said we would walk in woods and fields, and by the sides of rivers, and how happy we would be. ... and there is the bird - the same bird - now he flies to another tree, and stays to sing. Come!” Here, the bird functions as a metaphor for their freedom and their ability to choose their own path in the world. Later in the chapter birds are again used as harbingers of freedom. Nell and her grandfather stop “to listen to the songs that broke the happy silence, or watch the sun as it trembled through the leaves” and at length their path became “clearer and less intricate” and they followed a lane to a “very small place” where they meet a “pale, simple-looking man, of a spare and merger habit.” This man is a school teacher.

Thoughts

Is it me, or do you also find that Nell’s grandfather gets more annoying each time we meet him?

Dickens blends and contrasts the feelings of both place and space very effectively - city and country, discordant noise and peace. How effective do you find his comparisons? Why do you think he is so consciously making these contrasts?

To me, the flight of Nell and her grandfather blends elements of Cordelia and Lear from Shakespeare’s King Lear and Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. What do you think? Can you think of any other texts where we see echoes of Nell’s flight?

Again, we see a bird play a subtle, but important role in this novel. Naturally, I will be pointing out all bird-sightings. To what extent do you think that Dickens is consciously embedding bird’s into the symbolic and metaphoric fabric of the novel? Fair warning ... more bird references are coming!

The schoolmaster seems to be rather sad, lonely, distressed, and thoughtful. The teacher invites Nell and her grandfather into his humble little schoolroom and tells them they are welcome to stay until morning. Nell sees “a few dog-eared books” and other indications that the school is not too prosperous. Still, there is clear evidence that one or more of the students are good scholars. We learn that there is one outstanding student who is “far beyond all his companions.” We further learn that this student is ill, very ill, and it appears that the school master is trying to rationalize the fact that the student is not playing on the green and not attending his regular routines. The chapter with the teacher asking Nell to say a prayer for a sick child as he gazes at the student’s work and laments the fact that “it is a little hand to have done all that, and waste away with sickness. It is a very, very, little hand.”

Thoughts

In this chapter we have a situation where an older man is lamenting the poor health of a child. Do you see any comparable situation in this chapter to the overall arc of the story so far with Nell and her grandfather? If so, why might Dickens be using this technique in the novel?

In this chapter we moved from a country fair to a schoolhouse in a small town. If we could categorize what the purpose of each new location that Nell and her father find themselves, what would you say this chapter might be?

This chapter marks the end of a reading part of the novel for the original readers. Why is this chapter an effective place to stop?

It has been a few chapters since we have been with Little Nell and her father. In the interim we have spent our time in London. Now, we again turn our attention to the countryside. After Nell and her father flee the race-ground they sit “upon the borders of a little wood” where “their resting-place was solitary and still.” Still, they can “distinguish the noise of the distant shouts, the hum of voices, and the beating of drums.” We learn that Mr Trent has a “disordered imagination.” To Nell, her greatest fear is to be separated from her grandfather. Nell reassures her grandfather that “[w]e are alone together, and may ramble where we like.” To reinforce this image we get ... wait for it ... a reference to a bird that, as Nell observes, is “flying into the wood, and leading the way for us to follow. You remember that we said we would walk in woods and fields, and by the sides of rivers, and how happy we would be. ... and there is the bird - the same bird - now he flies to another tree, and stays to sing. Come!” Here, the bird functions as a metaphor for their freedom and their ability to choose their own path in the world. Later in the chapter birds are again used as harbingers of freedom. Nell and her grandfather stop “to listen to the songs that broke the happy silence, or watch the sun as it trembled through the leaves” and at length their path became “clearer and less intricate” and they followed a lane to a “very small place” where they meet a “pale, simple-looking man, of a spare and merger habit.” This man is a school teacher.

Thoughts

Is it me, or do you also find that Nell’s grandfather gets more annoying each time we meet him?

Dickens blends and contrasts the feelings of both place and space very effectively - city and country, discordant noise and peace. How effective do you find his comparisons? Why do you think he is so consciously making these contrasts?

To me, the flight of Nell and her grandfather blends elements of Cordelia and Lear from Shakespeare’s King Lear and Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. What do you think? Can you think of any other texts where we see echoes of Nell’s flight?

Again, we see a bird play a subtle, but important role in this novel. Naturally, I will be pointing out all bird-sightings. To what extent do you think that Dickens is consciously embedding bird’s into the symbolic and metaphoric fabric of the novel? Fair warning ... more bird references are coming!

The schoolmaster seems to be rather sad, lonely, distressed, and thoughtful. The teacher invites Nell and her grandfather into his humble little schoolroom and tells them they are welcome to stay until morning. Nell sees “a few dog-eared books” and other indications that the school is not too prosperous. Still, there is clear evidence that one or more of the students are good scholars. We learn that there is one outstanding student who is “far beyond all his companions.” We further learn that this student is ill, very ill, and it appears that the school master is trying to rationalize the fact that the student is not playing on the green and not attending his regular routines. The chapter with the teacher asking Nell to say a prayer for a sick child as he gazes at the student’s work and laments the fact that “it is a little hand to have done all that, and waste away with sickness. It is a very, very, little hand.”

Thoughts

In this chapter we have a situation where an older man is lamenting the poor health of a child. Do you see any comparable situation in this chapter to the overall arc of the story so far with Nell and her grandfather? If so, why might Dickens be using this technique in the novel?

In this chapter we moved from a country fair to a schoolhouse in a small town. If we could categorize what the purpose of each new location that Nell and her father find themselves, what would you say this chapter might be?

This chapter marks the end of a reading part of the novel for the original readers. Why is this chapter an effective place to stop?

Chapter the Twenty-fifth

This is a very interesting chapter. It swings widely in emotion, social commentary, and character development. Overall, it may offer more questions than answers, but let’s put our heads together and explore it.

We begin with the morning coming. Nell learns that the old lady that usually attends to the schoolmaster’s morning needs was helping nurse the sick little scholar. Nell willing volunteers to prepare breakfast. The schoolmaster notices that Nell’s grandfather appeared tired and suggests they spend another day with him. Nell agrees, and sets about “the performance of such household duties as his little cottage stood in need of.” As The school day begins to unfold. The student’s come, notice that their schoolmate is absent, and do not “violate the sanctity of seat or peg.” For the schoolmaster, his mind is more on the sick student that his day’s lessons. The students - being students - act out a bit and finally the teacher decides to declare “an extra half-holiday this afternoon.” He only asks that the students not be too noisy or disruptive out of class. In anticipation of how some people will respond to this unscheduled dismissal of class he remarks “[i]t is difficult ... to please everybody, as most of us would have discovered, even without the fable which bears that moral.” The schoolmaster is correct. Several people express their “entire disproved of the schoolmaster’s proceedings.” What could be the sub-text of these comments?

Thoughts

The chapter opens with several incidences of co-operation between Nell and the schoolmaster and the schoolmaster's housekeeper who is today helping attend the sick student. People helping others. This is one of the tropes that Dickens is clearly focussing on in TOCS. In contrast, we see how others do not sense a need to help others but rather act only for their own interests. What other examples of these contrasting states can be found in this chapter? What do you think are the reasons Dickens is structuring the text in such a manner?

In this chapter there is a passing reference to a fable about pleasing everybody. The gable recounts the story of a man, his son, and their donkey going to market. This is an example of how modern readers may well miss a reference that the original readers would comprehend more easily. I missed it and was grateful that my Penguin copy explained it in the “Notes.” Do you often wish you could read a Victorian novel with the sensibility of a Victorian rather than someone in the 21C? I wish I fully understood the micro history of Dickens’s novels.

Briefly, this is the fable. A man and his son were taking their donkey to market. People along the way suggested that someone should ride the beast, that the son not ride while the father walked, and so on, until it ended up that the man and the boy were carrying the donkey. How might this fable fit into TOCS?

The mother of the dying boy partially blames the school master for her son’s ill health and says he should not see her son: “This is what his learning has brought him to. Oh dear, dear, what can I do? ... . If he hadn’t been poring over his books out of fear for you, he would have been well and merry now, I know he would.” Such feelings are shared with many others in the sick room and they “murmured to each other that they never thought there was much good in learning, and that this convinced them.”

The schoolmaster gets to see Harry, the ill boy. Harry sees Nell and wants to shake her hand. Harry is failing quickly. He asks that someone wave a handkerchief from the window to the boys playing on the green. Again, Harry asks for Nell’s hand. The schoolmaster holds Harry’s hand. Harry dies, and yet the teacher could not lay the dead hand down.

Thoughts

The death of a child. Nell weeping. The laments of a parent. The inability and helpless of knowledge and understanding (represented by the schoolmaster) to change the fate of life. I must ask this question: To what extent did you find this chapter overly melodramatic? Why?

Reflections

We are far enough into the novel to see that Nell and her grandfather are always on the move. They have met with, dealt with, and learned much from those they have met. Some people open their hearts and homes to them while others plot and scheme against them. To me, I think Dickens is offering his readers vignettes of life they would know and immediately recognize. Dickens knew his original readers well.

We may wonder what the end game is in this novel. That, of course, remains to be seen. What I think we can do is continue to watch what we know has already been established in the novel. For example, what images seem to be repeated continually? To what degree is the relationship between Nell and her grandfather altering? If so, how, and for what purpose? Do any of the people Nell and her grandfather meet fit into archetypes that will help us as readers understand and appreciate the novel more?

By now you may have formed an opinion of Nell. Her presentation as a character tends to create strong opinions. Who is she? From what depths of myth or archetype might she come? On the other hand, is her character too melodramatic and too annoying?

The final word goes to the birds. I think the presence of the birds in TOCS goes far beyond static elements of setting. Time will tell if I can convince you. For now, here is a bit more information on Dickens and birds. Burnaby Rudge, our next novel, will prominently feature a Raven. No more on that novel, or I will spoil the fun. For now, in general terms of Ravens, Dickens had three as pets over his own lifetime. He named them all Grip. Dickens had the first Raven stuffed upon its death and kept it in his study Years later, after Dickens’s death, the Raven was auctioned off and now can be found in the rare books department of the Philadelphia Free Library. This is the Raven that is linked to E. A. Poe’s famous poem “The Raven.”

While on Dickens’s first reading tour in North America he was given an Eagle by an admirer. Dickens brought the bird back to England and kept it in the backyard of his home. It was later given to the British artist Sir Edwin Landseer. Landseer was best known for his paintings of animals and he is the artist who designed the lions at Nelson’s Column. Landseer also contributed one illustration for a Christmas book by Dickens.

And now to canaries. Dickens’s eldest daughter Mamie had a pet canary whose name was “Dick.” When Mamie was in France the canary was sent to France to keep Mamie company. Because of all the birds in the Dickens household, he refused to allow anyone to own a cat, or to allow a cat into his home. When Dick the canary passed away, he was buried in the garden of Gad’s Hill Place and a gravestone was erected that stated “This is the grave of Dick, the best of birds.” And yes, my fellow Curiosities, there will be more about birds to come at a later time.

This is a very interesting chapter. It swings widely in emotion, social commentary, and character development. Overall, it may offer more questions than answers, but let’s put our heads together and explore it.

We begin with the morning coming. Nell learns that the old lady that usually attends to the schoolmaster’s morning needs was helping nurse the sick little scholar. Nell willing volunteers to prepare breakfast. The schoolmaster notices that Nell’s grandfather appeared tired and suggests they spend another day with him. Nell agrees, and sets about “the performance of such household duties as his little cottage stood in need of.” As The school day begins to unfold. The student’s come, notice that their schoolmate is absent, and do not “violate the sanctity of seat or peg.” For the schoolmaster, his mind is more on the sick student that his day’s lessons. The students - being students - act out a bit and finally the teacher decides to declare “an extra half-holiday this afternoon.” He only asks that the students not be too noisy or disruptive out of class. In anticipation of how some people will respond to this unscheduled dismissal of class he remarks “[i]t is difficult ... to please everybody, as most of us would have discovered, even without the fable which bears that moral.” The schoolmaster is correct. Several people express their “entire disproved of the schoolmaster’s proceedings.” What could be the sub-text of these comments?

Thoughts

The chapter opens with several incidences of co-operation between Nell and the schoolmaster and the schoolmaster's housekeeper who is today helping attend the sick student. People helping others. This is one of the tropes that Dickens is clearly focussing on in TOCS. In contrast, we see how others do not sense a need to help others but rather act only for their own interests. What other examples of these contrasting states can be found in this chapter? What do you think are the reasons Dickens is structuring the text in such a manner?

In this chapter there is a passing reference to a fable about pleasing everybody. The gable recounts the story of a man, his son, and their donkey going to market. This is an example of how modern readers may well miss a reference that the original readers would comprehend more easily. I missed it and was grateful that my Penguin copy explained it in the “Notes.” Do you often wish you could read a Victorian novel with the sensibility of a Victorian rather than someone in the 21C? I wish I fully understood the micro history of Dickens’s novels.

Briefly, this is the fable. A man and his son were taking their donkey to market. People along the way suggested that someone should ride the beast, that the son not ride while the father walked, and so on, until it ended up that the man and the boy were carrying the donkey. How might this fable fit into TOCS?

The mother of the dying boy partially blames the school master for her son’s ill health and says he should not see her son: “This is what his learning has brought him to. Oh dear, dear, what can I do? ... . If he hadn’t been poring over his books out of fear for you, he would have been well and merry now, I know he would.” Such feelings are shared with many others in the sick room and they “murmured to each other that they never thought there was much good in learning, and that this convinced them.”

The schoolmaster gets to see Harry, the ill boy. Harry sees Nell and wants to shake her hand. Harry is failing quickly. He asks that someone wave a handkerchief from the window to the boys playing on the green. Again, Harry asks for Nell’s hand. The schoolmaster holds Harry’s hand. Harry dies, and yet the teacher could not lay the dead hand down.

Thoughts

The death of a child. Nell weeping. The laments of a parent. The inability and helpless of knowledge and understanding (represented by the schoolmaster) to change the fate of life. I must ask this question: To what extent did you find this chapter overly melodramatic? Why?

Reflections

We are far enough into the novel to see that Nell and her grandfather are always on the move. They have met with, dealt with, and learned much from those they have met. Some people open their hearts and homes to them while others plot and scheme against them. To me, I think Dickens is offering his readers vignettes of life they would know and immediately recognize. Dickens knew his original readers well.

We may wonder what the end game is in this novel. That, of course, remains to be seen. What I think we can do is continue to watch what we know has already been established in the novel. For example, what images seem to be repeated continually? To what degree is the relationship between Nell and her grandfather altering? If so, how, and for what purpose? Do any of the people Nell and her grandfather meet fit into archetypes that will help us as readers understand and appreciate the novel more?

By now you may have formed an opinion of Nell. Her presentation as a character tends to create strong opinions. Who is she? From what depths of myth or archetype might she come? On the other hand, is her character too melodramatic and too annoying?

The final word goes to the birds. I think the presence of the birds in TOCS goes far beyond static elements of setting. Time will tell if I can convince you. For now, here is a bit more information on Dickens and birds. Burnaby Rudge, our next novel, will prominently feature a Raven. No more on that novel, or I will spoil the fun. For now, in general terms of Ravens, Dickens had three as pets over his own lifetime. He named them all Grip. Dickens had the first Raven stuffed upon its death and kept it in his study Years later, after Dickens’s death, the Raven was auctioned off and now can be found in the rare books department of the Philadelphia Free Library. This is the Raven that is linked to E. A. Poe’s famous poem “The Raven.”

While on Dickens’s first reading tour in North America he was given an Eagle by an admirer. Dickens brought the bird back to England and kept it in the backyard of his home. It was later given to the British artist Sir Edwin Landseer. Landseer was best known for his paintings of animals and he is the artist who designed the lions at Nelson’s Column. Landseer also contributed one illustration for a Christmas book by Dickens.

And now to canaries. Dickens’s eldest daughter Mamie had a pet canary whose name was “Dick.” When Mamie was in France the canary was sent to France to keep Mamie company. Because of all the birds in the Dickens household, he refused to allow anyone to own a cat, or to allow a cat into his home. When Dick the canary passed away, he was buried in the garden of Gad’s Hill Place and a gravestone was erected that stated “This is the grave of Dick, the best of birds.” And yes, my fellow Curiosities, there will be more about birds to come at a later time.

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Twenty-first

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Twenty-firstKit’s ... honesty has been established without a doubt, but what is next for his character? Will he be part of the entire trajectory of the novel?..."

Gosh, I hope so! Kit is the only reason I continue reading. I haven't connected with anyone else at this point, which is why I got goosebumps when Dick and Quilp arrived at Kit's home. It seems an overreaction, but I honestly can't remember the last time I had such a visceral reaction to a scene. It was as though an ominous evil had darkened this poor but bright and happy home. Frankly, I was very upset with Mr. Dickens for sullying what I hoped would be a safe place. I was happy when the two left, but their visit seemed like an ominous omen for the Nubbles family.

Keep an eye open for more encounters with dogs or canine-like activity.

Oh, good Lord. This interaction made me think that Quilp is not only cruel and selfish, but also a bit manic. The man has a screw loose.

I don't know if I can stomach any more people being mean to dogs. I've reached the point in my life when I need to shift to more gentle authors who focus on life's simple pleasures. Dull but comforting sounds so inviting.

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Twenty-second

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Twenty-secondAnd so off Kit goes to his new employers at Abel cottage. ..."

So the name "Abel" belongs to both the Garland's son and their home. Surely this invites further scrutiny.

Abel, of course, was the second-born son of Adam and Eve. The name in Hebrew means "breath". Abel found favor with God, which didn't go over well with Cain, so Cain murdered him. Oh, dear. Abel thus became the first martyr. Am I leaving out any salient points?

The first thought that pops into my mind is, is there a Cain out there somewhere? If there's a murderous brother lurking, it would explain the overprotectiveness shown by the Garlands. The original Abel was a good and godly man. Abel Garland has only been described in glowing terms so far, but is it significant that we've only heard of his goodness? We've yet to witness it for ourselves yet.

I'll be interested to see how things progress now that Kit is at Abel Cottage, and what we learn of Abel Garland.

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Twenty-fourth

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Twenty-fourthIs it me, or do you also find that Nell’s grandfather gets more annoying each time we meet him? ..."

It's not just you. After all the comments about Little Nell that I've been privy to since joining your company several years ago, I quite expected to get cavities from all of Nell's sweetness, but I find her much less tedious than her grandfather. She, at least, shows familial loyalty (no matter how misplaced it may be) and seems to have a healthy skepticism towards some of the less savory characters they've encountered. Not to mention the forethought of hiding a bit of money in her hem for future emergencies.

I can't help but notice the difference between our school teacher here, and Squeers in our last selection. Having caring parents close at hand obviously makes a difference. Seems like there may also be some foreshadowing of Paul Dombey here.

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Twenty-fifth

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Twenty-fifthDo you often wish you could read a Victorian novel with the sensibility of a Victorian rather than someone in the 21C? I wish I fully understood the micro history of Dickens’s novels. ...

Yes and no. I do feel as if I'm missing out on some references (I'd completely forgotten the fable about carrying the donkey, for example, and am still not sure how it fits in here), but I think it's more interesting for me to read these stories and others (like the Bible) decades or centuries later to see that, while human beings may have evolved in many ways over time, human nature is still very much the same.

The thing that struck me in this chapter was the mob mentality. The students took advantage of the teacher's distraction and egged each other on in their bad behavior, when I'm sure they would have normally, or individually, behaved pretty well. The mothers (here I go, thinking the word "hens" again!) got in full gossip gear and were eager to bad mouth the poor schoolmaster to anyone who seemed open to hearing it. Had one brave soul stood up for him and pointed out his devotion to the sick boy, I have no doubt that the others would have felt shamed, and quickly jumped on that bandwagon.

We may wonder what the end game is in this novel. That, of course, remains to be seen. What I think we can do is continue to watch what we know has already been established in the novel. For example, what images seem to be repeated continually?

We still have a long way to go, of course, but at this point TOCS seems to be a simple story of good versus evil. I suppose that's what all stories are, once distilled, but there's very little nuance here. Perhaps it will also be a bit of a cautionary tale against gambling, but while that's been the catalyst for our story, it hasn't really been a focal point.

Because of all the birds in the Dickens household, he refused to allow anyone to own a cat, or to allow a cat into his home.

This made me wonder about the cat he loved so much that after its death, Dickens turned its paw into a letter opener (ick). I found this, which explains the discrepancy:

http://www.openculture.com/2014/11/ch...

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter the Twenty-fifth

Do you often wish you could read a Victorian novel with the sensibility of a Victorian rather than someone in the 21C? I wish I fully understood the micro hi..."

Hi Mary Lou

Thank you for your thoughtful and insightful comments.

Ch 21

Kit is a delightful character. While his first appearance was not too flattering, Dickens seems to be steering him into a new and much more positive light. Now, as for the dogs. We have seen dogs presented in less than favourable circumstances. Perhaps there will be an alteration in their portrayal and how they interact with humans later in the novel. For now, if you focus on birds, you will be pleased to see what Dickens has in mind later in the story.

Ch 22

Yes. I too believe that Dickens had the Bible in the back of his mind when he wrote his novels. Often, some part will percolate to the surface. As to what might await Able and the Garlands we will have to wait. For now, they are good, and represent Good. Even Whiskers is good for Kip.

Ch 24

I very much enjoy your linking and recall of what the Curiosities have been discussing and reading previously. When we compare Nell to Quilp and Old Trent (and not to mention the array of other nasty minor characters met along the way) Nell’s super-sugary nature is, I think, structurally necessary. Yes, she is portrayed as a hyper-melodramatic goodie-two-shoes, but without such a counterbalance the novel would crumble.

Ch 25

Your mention of the phrase “human nature” really resonated with me. My Victorian history professor said at the very beginning of the course, and repeated it seems every week, that history does not repeat itself. Human nature is what repeats itself. It is up to historians to record human nature, interpret it, and, hopefully, help society learn about itself. The caveat was that how the history is written depends on where human nature rests at the time of its being recorded.

We were all baffled by what she said back then. It is only now that I see her wisdom.

Do you often wish you could read a Victorian novel with the sensibility of a Victorian rather than someone in the 21C? I wish I fully understood the micro hi..."

Hi Mary Lou

Thank you for your thoughtful and insightful comments.

Ch 21

Kit is a delightful character. While his first appearance was not too flattering, Dickens seems to be steering him into a new and much more positive light. Now, as for the dogs. We have seen dogs presented in less than favourable circumstances. Perhaps there will be an alteration in their portrayal and how they interact with humans later in the novel. For now, if you focus on birds, you will be pleased to see what Dickens has in mind later in the story.

Ch 22

Yes. I too believe that Dickens had the Bible in the back of his mind when he wrote his novels. Often, some part will percolate to the surface. As to what might await Able and the Garlands we will have to wait. For now, they are good, and represent Good. Even Whiskers is good for Kip.

Ch 24

I very much enjoy your linking and recall of what the Curiosities have been discussing and reading previously. When we compare Nell to Quilp and Old Trent (and not to mention the array of other nasty minor characters met along the way) Nell’s super-sugary nature is, I think, structurally necessary. Yes, she is portrayed as a hyper-melodramatic goodie-two-shoes, but without such a counterbalance the novel would crumble.

Ch 25

Your mention of the phrase “human nature” really resonated with me. My Victorian history professor said at the very beginning of the course, and repeated it seems every week, that history does not repeat itself. Human nature is what repeats itself. It is up to historians to record human nature, interpret it, and, hopefully, help society learn about itself. The caveat was that how the history is written depends on where human nature rests at the time of its being recorded.

We were all baffled by what she said back then. It is only now that I see her wisdom.

Mary Lou wrote: Peter wrote: "Is it me, or do you also find that Nell’s grandfather gets more annoying each time we meet him? ..."

Mary Lou wrote: Peter wrote: "Is it me, or do you also find that Nell’s grandfather gets more annoying each time we meet him? ..."It's not just you. ..."

Nope, not just you in the least.

I was angry at him all over again when his worst fear is that Nell won't be able to visit him. This is grandfather's relation to Nell all over again: he thinks it's about loving her, but it's about loving himself--otherwise, his worst fear would be harm coming to her, not his personal loss of her as a comfort.

Notice he's also imagining himself in jail? What did you do, Grandfather Trent?

Or is he just thinking debtor's prison?

Also, it's Nell's mother who is his child, right? Grandfather mentioned her mother in an earlier chapter--but if he's her mother's father, then why are he and Nell's brother both named Trent?

Peter wrote: "Quilp assures Mrs Nubbles that “l don’t eat babies.”..."

Peter wrote: "Quilp assures Mrs Nubbles that “l don’t eat babies.”..."This made me laugh out loud when I read it.

Thus, with Nell married, Quilp and Fred will have access to the riches that Fred’s grandfather claims he does not have, but Quilp believes he does have.

Quilp knows at this point that Grandfather Trent has no money though, right? Not only has he booted him out of his house for lack of funds, but there's this exchange near the end of Chapter 23:

"...I know how rich he really is," [said Quilp]

"I suppose you should," said Trent.

"I think I should indeed," rejoined the dwarf; and in that, at least, he spoke the truth.

I read this to be sarcastic on our narrator's part.

Anyway, if Quilp knows there's no money, I can't sort out exactly what his goal is here. I mean sure, vengeance, but how? This book does feel kind of short on end-game in more than one plot thread.

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "Quilp assures Mrs Nubbles that “l don’t eat babies.”..."

This made me laugh out loud when I read it.

Thus, with Nell married, Quilp and Fred will have access to the riches that Fre..."

Hi Julie

Your reading of the passage and logic make sense. A touch of sarcasm on the narrator’s point gives us much to think about.

Could it be that Dickens wants Quilp to be painted in an even more ugly light, if that is possible? Does Quilp want to pursue old Trent and Nell for the sheer pleasure of it? Does Quilp have any future plans for them if he does hunt them down?

I still can’t understand Quilp or his motivations. That may be Dickens’s exact point when we consider Quilp’s character. The depths of his character, and hence his evil, are unknown.

This made me laugh out loud when I read it.

Thus, with Nell married, Quilp and Fred will have access to the riches that Fre..."

Hi Julie

Your reading of the passage and logic make sense. A touch of sarcasm on the narrator’s point gives us much to think about.

Could it be that Dickens wants Quilp to be painted in an even more ugly light, if that is possible? Does Quilp want to pursue old Trent and Nell for the sheer pleasure of it? Does Quilp have any future plans for them if he does hunt them down?

I still can’t understand Quilp or his motivations. That may be Dickens’s exact point when we consider Quilp’s character. The depths of his character, and hence his evil, are unknown.

Chapter 21

Chapter 21Looks like things are looking up for Kit. Good kid. He deserves it.

This chapter is interesting. I consider it in two halves. The first half is all sunny and nice music as Kit gets a good job. Then, as Quilp enters, it gives way to cloudying skies and darkening music. And this is how I see Quilp if this were a dramatization of the book. Dark music anticipating his arrival. That way we can prepare ourselves by grabbing our seats and gritting our teeth. We need a song entitled Quilp's song.

I think this budding "friendship" between Quilp and Swiveller has legs. Fertile ground here. Each is playing the other. So who out plays whom? (Did I get that right?) Swiveller is the only person who does not fear Quilp, and he just may be smarter than he lets on.

.

Peter wrote: "The mother of the dying boy partially blames the school master for her son’s ill health."

I wish I would have known her long ago before I went through all those awful years at school only to find out now reading TOCS that the reason for my seizures and migraines may have been the school all along. :-)

I wish I would have known her long ago before I went through all those awful years at school only to find out now reading TOCS that the reason for my seizures and migraines may have been the school all along. :-)

"Why don't you come and bite me, why don't you come and tear me to pieces, you coward?"

Chapter 21

Phiz

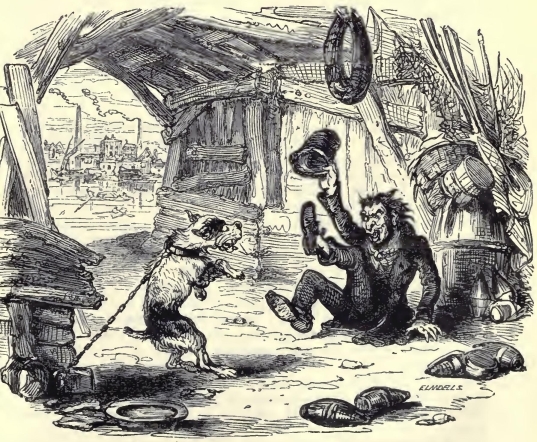

Text Illustrated:

In the height of his ecstasy, Mr Quilp had like to have met with a disagreeable check, for rolling very near a broken dog-kennel, there leapt forth a large fierce dog, who, but that his chain was of the shortest, would have given him a disagreeable salute. As it was, the dwarf remained upon his back in perfect safety, taunting the dog with hideous faces, and triumphing over him in his inability to advance another inch, though there were not a couple of feet between them.

‘Why don’t you come and bite me, why don’t you come and tear me to pieces, you coward?’ said Quilp, hissing and worrying the animal till he was nearly mad. ‘You’re afraid, you bully, you’re afraid, you know you are.’

The dog tore and strained at his chain with starting eyes and furious bark, but there the dwarf lay, snapping his fingers with gestures of defiance and contempt. When he had sufficiently recovered from his delight, he rose, and with his arms a-kimbo, achieved a kind of demon-dance round the kennel, just without the limits of the chain, driving the dog quite wild. Having by this means composed his spirits and put himself in a pleasant train, he returned to his unsuspicious companion, whom he found looking at the tide with exceeding gravity, and thinking of that same gold and silver which Mr Quilp had mentioned.

Poor dog.

Commentary:

Although many of Browne's early cuts for The Old Curiosity Shop are somewhat caricatured, comic portrayals of characters, his Quilp is a notable creation. Less has been said in favor of his Nell, but compared to Cattermole's, who is either a wax doll or barely visible, Browne makes us believe in the "cherry-cheeked, red-lipped" child Quilp describes so lecherously, and yet the artist never loses the pathos of Nell's situation — indeed, it could be argued that Phiz's Nell is more flesh and blood than Dickens'. Phiz seems to have transcended the rigidity of figure which characterized his virtuous females in Nicholas Nickleby.

Browne absorbed many influences besides that of caricature, including Christian iconography, German Romantic art, and the influence of some of his contemporaries among British painters, such as Maclise.

It is, however, as a caricaturist that Dickens regarded Browne at this point. It is possible that Phiz's designs for The Old Curiosity Shop presented Dickens with disturbing visual evidence of his text's implications. Never again do the original illustrations for a Dickens novel portray so much low life or so much exuberant energy. The character who epitomizes both is Quilp.

Quilp cavorts through sixteen cuts (excluding one by Cattermole, five of which, following the text, have him thrusting himself through doors and windows, often preceded by his tall, narrow hat. In another he is shown having gone through a gateway. Elsewhere he is usually engaged in violent or disreputable behavior: leaning back in his chair with his feet on the table, smoking a long, upward — pointing cigar while his wife sits by submissively; sitting on his desk while Nell stands apprehensively near by; smoking in the grandfather's chair with his bandy legs halfway up in the air; beating savagely at Dick, whom he has mistaken for his own wife; rolling on the ground, tormenting his dog; sitting on a beer barrel, raucously drinking and enjoying Sampson's discomfort; and beating at the effigy of Kit. Also in this latter illustration (ch. 16), the figure of Punch on the tombstone is like an incarnation of Quilp as Nell's pursuer; the puppet even looks as though it is making an obscene gesture at Nell (The first but not the second point has been made by Gabriel Pearson, p. 87). The cumulative effect of Phiz's illustrations is to emphasize embedded sexual nuances and to bring to the novel the vital energy of comic rascality.

The Kitchen at Abel Cottage

Chapter 22

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Down stairs, therefore, Kit went; and at the bottom of the stairs there was such a kitchen as was never before seen or heard of out of a toy-shop window, with everything in it as bright and glowing, and as precisely ordered too, as Barbara herself. And in this kitchen, Kit sat himself down at a table as white as a tablecloth, to eat cold meat, and drink small ale, and use his knife and fork the more awkwardly, because there was an unknown Barbara looking on and observing him.

It did not appear, however, that there was anything remarkably tremendous about this strange Barbara, who having lived a very quiet life, blushed very much and was quite as embarrassed and uncertain what she ought to say or do, as Kit could possibly be. When he had sat for some little time, attentive to the ticking of the sober clock, he ventured to glance curiously at the dresser, and there, among the plates and dishes, were Barbara’s little work-box with a sliding lid to shut in the balls of cotton, and Barbara’s prayer-book, and Barbara’s hymn-book, and Barbara’s Bible. Barbara’s little looking-glass hung in a good light near the window, and Barbara’s bonnet was on a nail behind the door. From all these mute signs and tokens of her presence, he naturally glanced at Barbara herself, who sat as mute as they, shelling peas into a dish; and just when Kit was looking at her eyelashes and wondering—quite in the simplicity of his heart—what colour her eyes might be, it perversely happened that Barbara raised her head a little to look at him, when both pair of eyes were hastily withdrawn, and Kit leant over his plate, and Barbara over her pea-shells, each in extreme confusion at having been detected by the other.

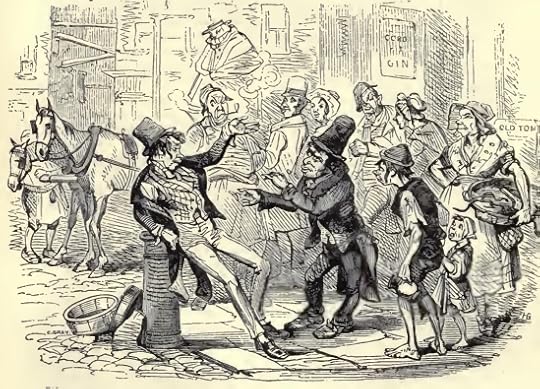

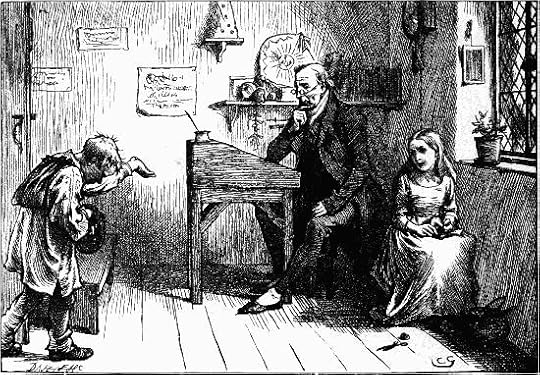

Quilp's Discovery

Chapter 23

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Left an infant by my parents, at an early age,’ said Mr Swiveller, bewailing his hard lot, ‘cast upon the world in my tenderest period, and thrown upon the mercies of a deluding dwarf, who can wonder at my weakness! Here’s a miserable orphan for you. Here,’ said Mr Swiveller raising his voice to a high pitch, and looking sleepily round, ‘is a miserable orphan!’

‘Then,’ said somebody hard by, ‘let me be a father to you.’

Mr Swiveller swayed himself to and fro to preserve his balance, and, looking into a kind of haze which seemed to surround him, at last perceived two eyes dimly twinkling through the mist, which he observed after a short time were in the neighbourhood of a nose and mouth. Casting his eyes down towards that quarter in which, with reference to a man’s face, his legs are usually to be found, he observed that the face had a body attached; and when he looked more intently he was satisfied that the person was Mr Quilp, who indeed had been in his company all the time, but whom he had some vague idea of having left a mile or two behind.

‘You have deceived an orphan, Sir,’ said Mr Swiveller solemnly.’

‘I! I’m a second father to you,’ replied Quilp.

‘You my father, Sir!’ retorted Dick. ‘Being all right myself, Sir, I request to be left alone—instantly, Sir.’

‘What a funny fellow you are!’ cried Quilp.

‘Go, Sir,’ returned Dick, leaning against a post and waving his hand. ‘Go, deceiver, go, some day, Sir, p’r’aps you’ll waken, from pleasure’s dream to know, the grief of orphans forsaken. Will you go, Sir?’

The dwarf taking no heed of this adjuration, Mr Swiveller advanced with the view of inflicting upon him condign chastisement. But forgetting his purpose or changing his mind before he came close to him, he seized his hand and vowed eternal friendship, declaring with an agreeable frankness that from that time forth they were brothers in everything but personal appearance. Then he told his secret over again, with the addition of being pathetic on the subject of Miss Wackles, who, he gave Mr Quilp to understand, was the occasion of any slight incoherency he might observe in his speech at that moment, which was attributable solely to the strength of his affection and not to rosy wine or other fermented liquor. And then they went on arm-in-arm, very lovingly together.

Commentary:

When we realize that the number of illustrations featuring Quilp is close to half the total number of drawings for the considerably longer novels in monthly parts, we get some statistical sense of the impact of Quilp's visual presence. Surely, illustrations make it impossible to conceal from oneself the dominant role of this delightful villain.

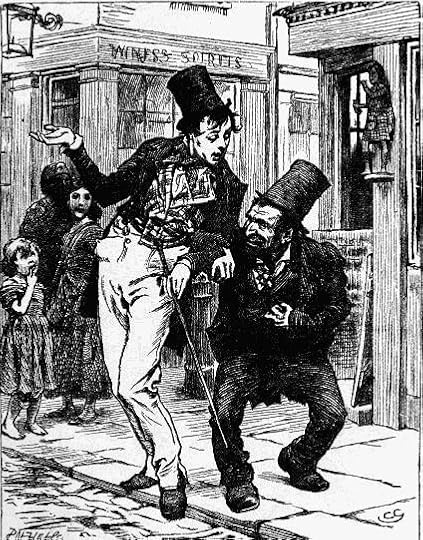

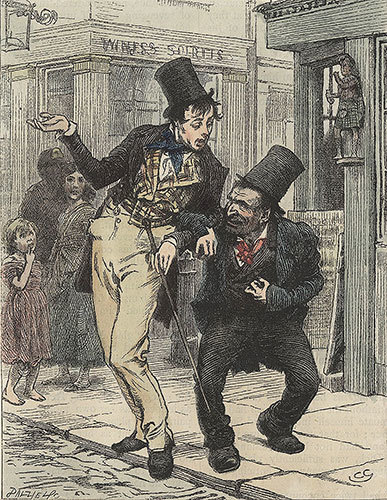

And then they went on arm-in-arm, very lovingly together

Chapter 23

Charles Green

Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens

Text Illustrated:

‘Go, Sir,’ returned Dick, leaning against a post and waving his hand. ‘Go, deceiver, go, some day, Sir, p’r’aps you’ll waken, from pleasure’s dream to know, the grief of orphans forsaken. Will you go, Sir?’

The dwarf taking no heed of this adjuration, Mr Swiveller advanced with the view of inflicting upon him condign chastisement. But forgetting his purpose or changing his mind before he came close to him, he seized his hand and vowed eternal friendship, declaring with an agreeable frankness that from that time forth they were brothers in everything but personal appearance. Then he told his secret over again, with the addition of being pathetic on the subject of Miss Wackles, who, he gave Mr Quilp to understand, was the occasion of any slight incoherency he might observe in his speech at that moment, which was attributable solely to the strength of his affection and not to rosy wine or other fermented liquor. And then they went on arm-in-arm, very lovingly together.

They went on arm in arm, very lovingly together

Chapter 23

Roland Wheelwright

1930

Rowland Wheelwright was an Australian-born British painter and illustrator. Using a diffuse pastel palette, he depicted equestrian, historical, and maritime scenes. Born to a family of sheep farmers in 1870 in Ipswich, Australia, Wheelwright moved with his parents to England during the Australian drought of the 1880s. The artist went on to study at St. John's Wood Art School and the Herkomer School of Art in Bushey. While in school, he became acquainted with painters such as Lucy Kemp-Welch while studying under Sir Hubert von Herkomer. Wheelwright died in 1955 in Bushey, United Kingdom.

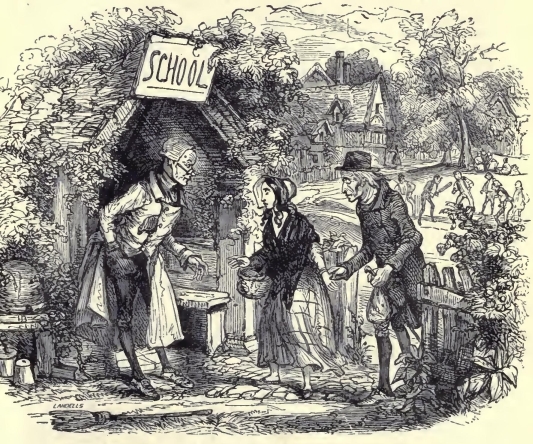

At the Schoolmaster's Porch

Chapter 24

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

It was a very small place. The men and boys were playing at cricket on the green; and as the other folks were looking on, they wandered up and down, uncertain where to seek a humble lodging. There was but one old man in the little garden before his cottage, and him they were timid of approaching, for he was the schoolmaster, and had ‘School’ written up over his window in black letters on a white board. He was a pale, simple-looking man, of a spare and meagre habit, and sat among his flowers and beehives, smoking his pipe, in the little porch before his door.

‘Speak to him, dear,’ the old man whispered.

‘I am almost afraid to disturb him,’ said the child timidly. ‘He does not seem to see us. Perhaps if we wait a little, he may look this way.’

They waited, but the schoolmaster cast no look towards them, and still sat, thoughtful and silent, in the little porch. He had a kind face. In his plain old suit of black, he looked pale and meagre. They fancied, too, a lonely air about him and his house, but perhaps that was because the other people formed a merry company upon the green, and he seemed the only solitary man in all the place.

They were very tired, and the child would have been bold enough to address even a schoolmaster, but for something in his manner which seemed to denote that he was uneasy or distressed. As they stood hesitating at a little distance, they saw that he sat for a few minutes at a time like one in a brown study, then laid aside his pipe and took a few turns in his garden, then approached the gate and looked towards the green, then took up his pipe again with a sigh, and sat down thoughtfully as before.

As nobody else appeared and it would soon be dark, Nell at length took courage, and when he had resumed his pipe and seat, ventured to draw near, leading her grandfather by the hand. The slight noise they made in raising the latch of the wicket-gate, caught his attention. He looked at them kindly but seemed disappointed too, and slightly shook his head.

Commentary:

Typical conditions under which Browne worked would make frequent last-minute additions under Dickens' instructions unlikely. From the early years of their association the novelist and illustrator followed a standard pattern of collaboration: for each forthcoming monthly number Dickens would give the subjects of the two illustrations (or four, for the final, double numbers) and include proof copy or a bit of manuscript whenever possible. Browne would execute these as drawings and submit them, time and distance allowing, to Dickens, who would either approve them or suggest alterations. If approved, the design would be etched by Browne on a steel previously prepared by Robert Young and then sent along to Young with the drawing and perhaps some further instructions regarding the biting-in; according to Browne's son, Young also "came down to Croydon nearly every Sunday, and sometimes during the week," for consultation. Here is a "diary" (evidently intended for a publisher's guidance) of Browne's typical procedures:

Friday evening, 11th Jan.........Received portion of copy containing Subject No. 1.

Sunday........................................... Posted sketch to Dickens.

Monday evening, 14th Jan..........Received back sketch of Subject No.1 from Dickens, enclosing a subject for No. 2.

Tuesday, 15th Jan.....................Forwarded sketch of Subject 2 to Dickens.

Wednesday, 16th Jan...................Received back ditto.

Sunday .......... .

Tuesday, 22nd Jan....................... First plate finished.

Saturday, 26th Jan.........................Second ditto finished.

— Supposing that I had nothing else to do, you may see by the foregoing that I could not well commence etching operations until Wednesday, the 16th.

"I make ten days to etch and finish four etchings. What do you make of it?" Browne comments at the bottom of this "diary." (Thomson, p. 234. (Four etchings means two in duplicate.)

We may take this to be a description of the normal process based on Browne's work for a novel later than Pickwick Papers (in the Preface to which Dickens states that "the interval has been so short between the production of each number in manuscript and its appearance in print, that the greater portion of the Illustrations have been executed by the artist from the author's mere verbal description of what he intended to write").

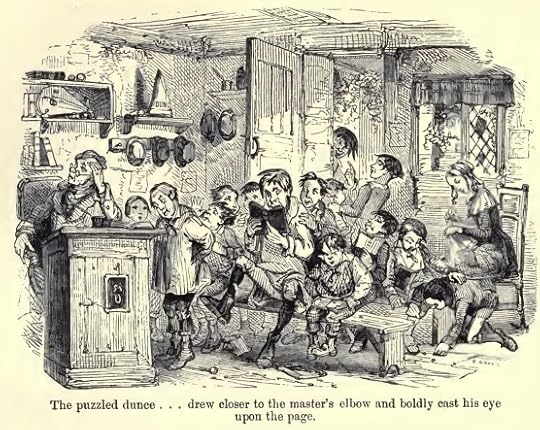

The Dunce improves the Occasion

Chapter 25

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

None knew this better than the idlest boys, who, growing bolder with impunity, waxed louder and more daring; playing odd-or-even under the master’s eye, eating apples openly and without rebuke, pinching each other in sport or malice without the least reserve, and cutting their autographs in the very legs of his desk. The puzzled dunce, who stood beside it to say his lesson out of book, looked no longer at the ceiling for forgotten words, but drew closer to the master’s elbow and boldly cast his eye upon the page; the wag of the little troop squinted and made grimaces (at the smallest boy of course), holding no book before his face, and his approving audience knew no constraint in their delight. If the master did chance to rouse himself and seem alive to what was going on, the noise subsided for a moment and no eyes met his but wore a studious and a deeply humble look; but the instant he relapsed again, it broke out afresh, and ten times louder than before.

A small white-headed boy with a sunburnt face appeared at the door

Chapter 25

Charles Green

Text Illustrated:

A small white-headed boy with a sunburnt face appeared at the door while he was speaking, and stopping there to make a rustic bow, came in and took his seat upon one of the forms. The white-headed boy then put an open book, astonishingly dog’s-eared upon his knees, and thrusting his hands into his pockets began counting the marbles with which they were filled; displaying in the expression of his face a remarkable capacity of totally abstracting his mind from the spelling on which his eyes were fixed. Soon afterwards another white-headed little boy came straggling in, and after him a red-headed lad, and after him two more with white heads, and then one with a flaxen poll, and so on until the forms were occupied by a dozen boys or thereabouts, with heads of every colour but grey, and ranging in their ages from four years old to fourteen years or more; for the legs of the youngest were a long way from the floor when he sat upon the form, and the eldest was a heavy good-tempered foolish fellow, about half a head taller than the schoolmaster.

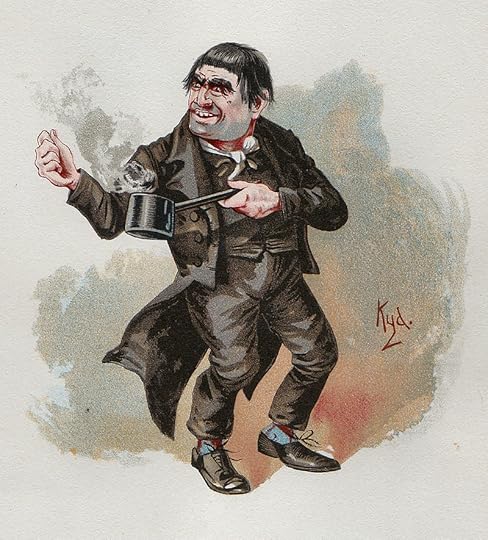

Kyd

Commentary:

Of the set of 50 cigarette cards, initially produced in 1910 and reissued in 1923, fully 15 or 30% concern a single novel, The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, attesting to the enduring popularity of the picaresque comic novel, and also suggesting that the later, darker novels such as Our Mutual Friend and The Mystery of Edwin Drood offered little for the caricaturist, the only late characters in the series being the singularly unpleasant Silas Wegg and Rogue Riderhood from Our Mutual Friend, and Turveydrop, Jo, Bucket, and Chadband from Bleak House. The popular taste was clearly still towards the earlier farce and character comedy of Dickens.

Kyd's representations are largely based on the original illustrations by Phiz and Seymour, although the modelling of the figures is suggestive of Phiz's own, expanded series for Household Edition volume of the 1870s. The anomaly, of course, is that Kyd should elect to depict minor figures from the first Dickens novel such as the Dingley Dell cricketers Dumkins and Luffey and the minor antagonist Major Bagstock, but omit significant characters from such later, still-much-read novels as A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations. Five of the fifty or 10% of the series come from the cast of The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress (1837-39): Oliver himself, asking for more; Fagin with his toasting fork, from the scene in which he prepares dinner for his crew; Sikes holding a beer-mug, and the Artful Dodger in an oversized adult topcoat and crushed top-hat. Surprisingly, some of the other significant characters, including Nancy and Rose Maylie, are not among the first set of fifty characters, in which Kyd exhibits a strong male bias, as he realizes only seven female characters: only the beloved Nell, the abrasive Sally Brass, and the quirky Marchioness from The Old Curiosity Shop, Sairey Gamp from Martin Chuzzlewit, Aunt Betsey Trotwood from David Copperfield, the burly Mrs. McStinger from Dombey and Son, and the awkward Fanny Squeers from Nicholas Nickleby appear in the essentially comic cavalcade. Since the popular taste in "characters from Dickens" as well as in "novels from Dickens" has changed markedly over the past century, Dick Swiveller must come as a delightful surprise for modern readers taking up that textual monument to Victorian sentimentality, The Old Curiosity Shop, for the first time.

Kim,

Thanks for finally adding Kyd to Kit again ;-) And thanks for the brilliant insight into how Phiz cooperated with Dickens. All these particulars were new to me!

Thanks for finally adding Kyd to Kit again ;-) And thanks for the brilliant insight into how Phiz cooperated with Dickens. All these particulars were new to me!

On Chapter 21

What I especially liked was the reason Quilp gives for not eating babies. He simply doesn‘t like them! So, he refrains from eating babies for the very opposite reason why normal mortals don‘t have them on their diet.

As to Kit‘s change and development - not only in terms of fortune but also with regard to his personality -, I am very glad that Dickens decided to give Kit a larger role in the plot and therefore to make him a more sensible and to-be-taken-seriously character. He is one of the few likeable characters up to now. Next to Dick, I‘d say.

As Peter, Mary Lou and Julie pointed out, Quilp‘s motives for trying to marry Swiveller to Little Nell are somewhat threadbare, or diffuse at best. He simply seems to be doing so out of spite - because Swiveller and Fred slighted and opposed him. While this takes up a pattern of vengefulness that has manifested itself once before - namely when he sets Grandpa against Kit because Kit insulted him in a conversation with the boy who stands on his head -, it still seems far-fetched. Quilp is a man of business, somebody who looks for and after his material advantages. Why should he spend time and money on a wild-goose-chase, trying to hunt up Nell and her grandfather and then make Nell marry Richard? There is no money in it for him, and quite on the contrary, he would lose even more money by looking for them. Add this to the money he has already given to Grandpa, money which he may have made good by the sales he got from the Old Curiosity Shop. But still, there is no material advantage.

The only reason he is forging this plot is probably because otherwise it would have been difficult for Dickens to keep the novel together. There is hardly any sensible connection between Quilp and the two wayfarers anymore, but the novel needs one, and that is why Dickens creates this revenge motif, trying to build a castle on a foundation of straw.

Similarly, I think that Quilp‘s little chat with the dog is absurd. It‘s completely over the top, and I am afraid we are sitting in the audience of Short and Codlin‘s Punch-and-Judy show when we witness Quilp rolling on the floor and taunting that dog.

What I especially liked was the reason Quilp gives for not eating babies. He simply doesn‘t like them! So, he refrains from eating babies for the very opposite reason why normal mortals don‘t have them on their diet.

As to Kit‘s change and development - not only in terms of fortune but also with regard to his personality -, I am very glad that Dickens decided to give Kit a larger role in the plot and therefore to make him a more sensible and to-be-taken-seriously character. He is one of the few likeable characters up to now. Next to Dick, I‘d say.

As Peter, Mary Lou and Julie pointed out, Quilp‘s motives for trying to marry Swiveller to Little Nell are somewhat threadbare, or diffuse at best. He simply seems to be doing so out of spite - because Swiveller and Fred slighted and opposed him. While this takes up a pattern of vengefulness that has manifested itself once before - namely when he sets Grandpa against Kit because Kit insulted him in a conversation with the boy who stands on his head -, it still seems far-fetched. Quilp is a man of business, somebody who looks for and after his material advantages. Why should he spend time and money on a wild-goose-chase, trying to hunt up Nell and her grandfather and then make Nell marry Richard? There is no money in it for him, and quite on the contrary, he would lose even more money by looking for them. Add this to the money he has already given to Grandpa, money which he may have made good by the sales he got from the Old Curiosity Shop. But still, there is no material advantage.

The only reason he is forging this plot is probably because otherwise it would have been difficult for Dickens to keep the novel together. There is hardly any sensible connection between Quilp and the two wayfarers anymore, but the novel needs one, and that is why Dickens creates this revenge motif, trying to build a castle on a foundation of straw.

Similarly, I think that Quilp‘s little chat with the dog is absurd. It‘s completely over the top, and I am afraid we are sitting in the audience of Short and Codlin‘s Punch-and-Judy show when we witness Quilp rolling on the floor and taunting that dog.

On Chapter 22

The introduction of Barbara, the servant, made me smile. Not only because she is such a nice person but also because it seems very obvious by the end of the chapter that Kit and Barbara may be about to fall in love with each other. The writing of it is on the wall. This would mean that Little Nell has one suitor less, and as it is the only really eligible suitor the question arises what further plans fate, and the writer, has for Little Nell.

When I called Kit an eligible suitor for Nell, of course, this only refers to the “new“ Kit. It was obvious that the one we saw at the beginning of the novel never had a chance - neither in Nell‘s eyes nor according to the rules of anything we know about drama.

As to Abel Garland, from all I have seen of him, I think he would more properly and aptly be called Unable Garland.

The introduction of Barbara, the servant, made me smile. Not only because she is such a nice person but also because it seems very obvious by the end of the chapter that Kit and Barbara may be about to fall in love with each other. The writing of it is on the wall. This would mean that Little Nell has one suitor less, and as it is the only really eligible suitor the question arises what further plans fate, and the writer, has for Little Nell.

When I called Kit an eligible suitor for Nell, of course, this only refers to the “new“ Kit. It was obvious that the one we saw at the beginning of the novel never had a chance - neither in Nell‘s eyes nor according to the rules of anything we know about drama.

As to Abel Garland, from all I have seen of him, I think he would more properly and aptly be called Unable Garland.

On Chapters 24 and 25

I think the schoomaster episode is a deliberately introduced parallel with regard to the relationship between Nell and Grandpa. The schoolmaster is emotionally dependent on the little scholar, among other things because he is so clever and docile and he also looks up to the teacher as his friend. Similarly, Grandpa depends on Nell‘s loyalty, love and on her (and the reader‘s) patience.

For all the apparent selflessness of the teacher, there might also be a certain amount of egocentricity about him. Who knows, maybe the little scholar‘s grandmother was not altogether wrong when she reproached him with overburdening the boy with tasks and expectations. I‘d not go so far as to say that he is responsible for the boy‘s death (like the grandmother implies, or rather openly asserts), but to a certain extent, the teacher may have lived through his gifted and admiring pupil.

Just look how often Grandpa makes Nell avow her love for him, and you might see some parallel in the two cases as well. Grandpa always says he is doing this and doing that - this and that meaning gambling, of course - for Nell, but there might still be some question as to whether he is not also doing it for himself. The fact is that he needs and exploits Little Nell. This was probably not so extreme in the case of the teacher and his scholar, but the teacher seems to have derived quite some self-esteem through the little scholar‘s regard for him.

I think the schoomaster episode is a deliberately introduced parallel with regard to the relationship between Nell and Grandpa. The schoolmaster is emotionally dependent on the little scholar, among other things because he is so clever and docile and he also looks up to the teacher as his friend. Similarly, Grandpa depends on Nell‘s loyalty, love and on her (and the reader‘s) patience.

For all the apparent selflessness of the teacher, there might also be a certain amount of egocentricity about him. Who knows, maybe the little scholar‘s grandmother was not altogether wrong when she reproached him with overburdening the boy with tasks and expectations. I‘d not go so far as to say that he is responsible for the boy‘s death (like the grandmother implies, or rather openly asserts), but to a certain extent, the teacher may have lived through his gifted and admiring pupil.

Just look how often Grandpa makes Nell avow her love for him, and you might see some parallel in the two cases as well. Grandpa always says he is doing this and doing that - this and that meaning gambling, of course - for Nell, but there might still be some question as to whether he is not also doing it for himself. The fact is that he needs and exploits Little Nell. This was probably not so extreme in the case of the teacher and his scholar, but the teacher seems to have derived quite some self-esteem through the little scholar‘s regard for him.

I think Quilp's "conversation" with the dog is revealing: Quilp doesn't care whether he lives or dies. In some ways he's the most desperate of gamblers. Sometimes it's the ones who don't care that win.

I think Quilp's "conversation" with the dog is revealing: Quilp doesn't care whether he lives or dies. In some ways he's the most desperate of gamblers. Sometimes it's the ones who don't care that win.

Tristram wrote: "This was probably not so extreme in the case of the teacher and his scholar, but the teacher seems to have derived quite some self-esteem through the little scholar‘s regard for him."