The History Book Club discussion

FREE READ (Only at the HBC)

>

SALT - FREE READ (ONLY AT THE HBC) - READ AND LEAD - Leisurely Read

OK, this is a free read. So there are no deadlines, no assigned moderation, no weekly reading assignment - just folks who want to talk about this particular book.

Hopefully, in time we will have folks step up to the plate and who want to read a poll selected book and the person who nominated the book just gets to read and post about the book they are reading and make comments as they go through the book. There are no spoiler threads and nothing else to it.

It is like the book discussions that you find in most other groups. These are not the History Book Club Buddy Reads, Spotlighted Reads or Book of the Month nor our Presidential Read Series - those all have structure to them. The HBC is making it easy for those folks so they have a spot too.

But we feel that sometimes folks want to read something of their own choosing so we have the polls for the Free Reads and nominations.

You must follow our rules and guidelines for civility and respect and of course - no self promotion and citations are required for any other book or author different from the selection itself.

Hopefully, in time we will have folks step up to the plate and who want to read a poll selected book and the person who nominated the book just gets to read and post about the book they are reading and make comments as they go through the book. There are no spoiler threads and nothing else to it.

It is like the book discussions that you find in most other groups. These are not the History Book Club Buddy Reads, Spotlighted Reads or Book of the Month nor our Presidential Read Series - those all have structure to them. The HBC is making it easy for those folks so they have a spot too.

But we feel that sometimes folks want to read something of their own choosing so we have the polls for the Free Reads and nominations.

You must follow our rules and guidelines for civility and respect and of course - no self promotion and citations are required for any other book or author different from the selection itself.

Who would like to join me for this free read. Sign up on this thread.

I would love to have some company as we post randomly how we feel about the book

I would love to have some company as we post randomly how we feel about the book

Video - The Big History series asks questions guaranteed to change the way you look at the past.

Did Napoleon’s invasion of Russia come undone because of…tin buttons?

Did New York become America’s biggest city because of…salt?

How does the sinking of the Titanic power your cell phone?

What’s the connection between ancient Egyptian mummies and a modern ham and cheese sandwich?

By weaving science into the core of the human story, Big History takes familiar subjects and gives them a twist that will have you rethinking everything from the Big Bang to today’s headlines.

The series creates an interconnected panorama of patterns and themes that links history to dozens of fields including astronomy, biology, chemistry, and geology. The first season ends with a two-hour finale that pulls everything we know about science and history into one grand narrative of the universe and us.

This is a great series by the way - Bill Gates

Did Napoleon’s invasion of Russia come undone because of…tin buttons?

Did New York become America’s biggest city because of…salt?

How does the sinking of the Titanic power your cell phone?

What’s the connection between ancient Egyptian mummies and a modern ham and cheese sandwich?

By weaving science into the core of the human story, Big History takes familiar subjects and gives them a twist that will have you rethinking everything from the Big Bang to today’s headlines.

The series creates an interconnected panorama of patterns and themes that links history to dozens of fields including astronomy, biology, chemistry, and geology. The first season ends with a two-hour finale that pulls everything we know about science and history into one grand narrative of the universe and us.

This is a great series by the way - Bill Gates

Bentley wrote: "March 1st - please join me - very much a free reading opportunity"

Bentley wrote: "March 1st - please join me - very much a free reading opportunity"I've been wanting to read this, so I'll pick it up. I'm still adjusting to the culture of this (and other) GR groups, so we'll see how it goes.

Great Jim - glad to have you join me. The Free Read will be the easiest. It is quite laissez faire. If you do not mention any other books or authors - then there are no citations to add either - that is the only thing we follow because of the goodreads software.

Everything in a Free Read is open ended - no stress (lol) - I have been wanting to read it too since seeing The Big History episode on Salt.

Everything in a Free Read is open ended - no stress (lol) - I have been wanting to read it too since seeing The Big History episode on Salt.

Introduction - The Rock

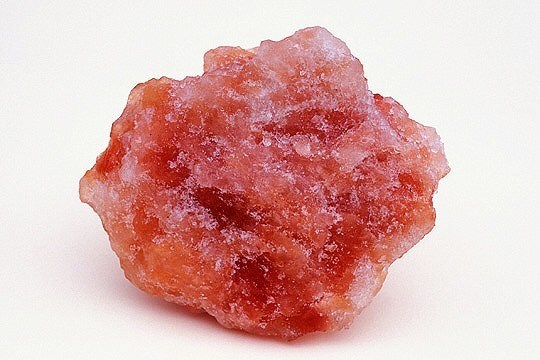

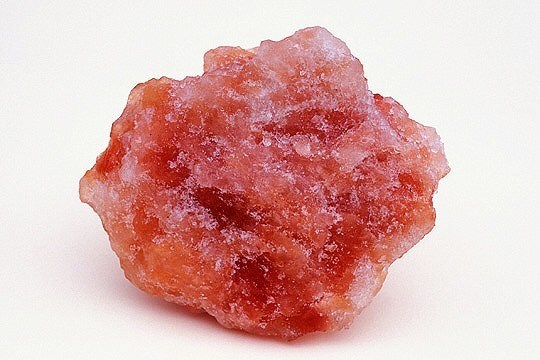

I just started the introduction of the book Salt. He bought the rock in Catalonia - salt mountain of Cardonia. The author tried all sorts of things to dry it out and found it had its own rules.

I just started the introduction of the book Salt. He bought the rock in Catalonia - salt mountain of Cardonia. The author tried all sorts of things to dry it out and found it had its own rules.

The History of Salt:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History...

Source: Wikipedia

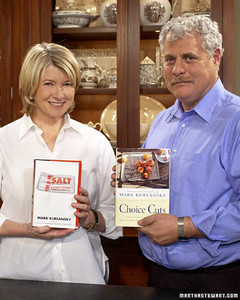

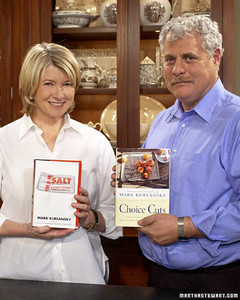

The Value of Salt Throughout History (Martha Steward and Mark Kurlansky)

Martha Stewart and author Mark Kurlanski read from his book Salt: A World History, the history of natural salt extracted from oceans and mined from the earth.

Video: https://www.marthastewart.com/910543/...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History...

Source: Wikipedia

The Value of Salt Throughout History (Martha Steward and Mark Kurlansky)

Martha Stewart and author Mark Kurlanski read from his book Salt: A World History, the history of natural salt extracted from oceans and mined from the earth.

Video: https://www.marthastewart.com/910543/...

Making your own salt:

DIY HERB SALT FROM SEA WATER!

In this short video we outline the steps we use to make sea salt from sea water and then infuse dried herbs from the garden to make herb salt. You can see our full recipe here https://www.northcoastjournal.com/hum...

Video: https://youtu.be/13gmtWermnI

DIY HERB SALT FROM SEA WATER!

In this short video we outline the steps we use to make sea salt from sea water and then infuse dried herbs from the garden to make herb salt. You can see our full recipe here https://www.northcoastjournal.com/hum...

Video: https://youtu.be/13gmtWermnI

Ghandi was very upset about the British Salt Tax:

Gandhi intended to produce salt from seawater to avoid paying tax and thus undermine Britain’s salt monopoly. This act of civil disobedience gained the support of tens of thousands of Indians, and inspired millions more to join the movement.

Video: https://youtu.be/SITkKXDptPg

1930 GANDHI THE SALT MARCH S. 1 EP. 25 | 100 YEARS SERIES

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mum_G...

The movie - Ghandi and the segment about the salt march:

https://youtu.be/WW3uk95VGes

Gandhi intended to produce salt from seawater to avoid paying tax and thus undermine Britain’s salt monopoly. This act of civil disobedience gained the support of tens of thousands of Indians, and inspired millions more to join the movement.

Video: https://youtu.be/SITkKXDptPg

1930 GANDHI THE SALT MARCH S. 1 EP. 25 | 100 YEARS SERIES

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mum_G...

The movie - Ghandi and the segment about the salt march:

https://youtu.be/WW3uk95VGes

What did anyone think of the comment that for centuries salt was equated with fertility?

Salt was very important to the Romans:

To the South of Rome lay the fertile agricultural lands of the Campanian Plain, watered by two rivers and capable of producing as many as three grain crops a year in some districts. Rome also possessed the highly lucrative salt trade, derived from the salt flats at the mouth of the Tiber. The importance of this commodity in the ancient world cannot be overstated.

To this day we say: “a man who is worth his salt.” In ancient Rome, this was literally true. The word “salary” comes from the Latin word for salt salarium, which linked employment, salt and soldiers, although the exact link is unclear. One theory is that the word soldier itself comes from the Latin sal dare (to give salt). The Roman historian Pliny the Elder states in his Natural History that "[I]n Rome. . .the soldier's pay was originally salt and the word salary derives from it. . ." (Plinius Naturalis Historia XXXI). More likely, the salarium was either an allowance paid to Roman soldiers for the purchase of salt or the price of having soldiers conquer salt supplies and guard the Salt Roads (Via Salarium) that led to Rome.

Whatever version one accepts, there is no question about the vital importance of salt and the salt trade that must have played a vital role in the establishment of a prosperous settled community in Rome, which must have attracted the unwelcome attention of less favoured tribes. The picture that emerges of the first Roman community is that of a group of clans fighting to defend their territory against the pressure of other peoples (Latins, Etruscans, Sabines etc.).

Interesting history of salt from Salt Works

https://www.seasalt.com/history-of-salt

Mining for Salt | How to Make Everything

https://youtu.be/YjC6h4x7V2I

HowStuffWorks - Dry Salt Mining

https://youtu.be/XBhY347jmgI

Salt Mine Documentary: History Of Salt Mining - Classic Docs

https://youtu.be/7RSh5IXad2E

Source: Youtube, Discovery

Salt was very important to the Romans:

To the South of Rome lay the fertile agricultural lands of the Campanian Plain, watered by two rivers and capable of producing as many as three grain crops a year in some districts. Rome also possessed the highly lucrative salt trade, derived from the salt flats at the mouth of the Tiber. The importance of this commodity in the ancient world cannot be overstated.

To this day we say: “a man who is worth his salt.” In ancient Rome, this was literally true. The word “salary” comes from the Latin word for salt salarium, which linked employment, salt and soldiers, although the exact link is unclear. One theory is that the word soldier itself comes from the Latin sal dare (to give salt). The Roman historian Pliny the Elder states in his Natural History that "[I]n Rome. . .the soldier's pay was originally salt and the word salary derives from it. . ." (Plinius Naturalis Historia XXXI). More likely, the salarium was either an allowance paid to Roman soldiers for the purchase of salt or the price of having soldiers conquer salt supplies and guard the Salt Roads (Via Salarium) that led to Rome.

Whatever version one accepts, there is no question about the vital importance of salt and the salt trade that must have played a vital role in the establishment of a prosperous settled community in Rome, which must have attracted the unwelcome attention of less favoured tribes. The picture that emerges of the first Roman community is that of a group of clans fighting to defend their territory against the pressure of other peoples (Latins, Etruscans, Sabines etc.).

Interesting history of salt from Salt Works

https://www.seasalt.com/history-of-salt

Mining for Salt | How to Make Everything

https://youtu.be/YjC6h4x7V2I

HowStuffWorks - Dry Salt Mining

https://youtu.be/XBhY347jmgI

Salt Mine Documentary: History Of Salt Mining - Classic Docs

https://youtu.be/7RSh5IXad2E

Source: Youtube, Discovery

Ernest Jones

Salt has long been a symbol of fertility, borne from the sea. Freud's biographer, the psychoanalyst Ernest Jones, pointed out that the Romans called a man in love ''salax,'' in a salted, salacious state. Salt could seem to create life and spur procreation because it could also prevent the decay of death. It could seem a guardian of the living world, holding off the inevitable for a time.

Salt's powers even reached into the spiritual world. In Japan it warded off evil spirits. In many countries newborns were rubbed in salt or dipped in salt water, a custom that may have preceded the practice of baptism. Christian holy water and holy salt may have had their origins in the Greek and Roman custom of using salt in religious offerings.

Salt is a necessary component in the functioning of cells and is found in all aspects of our bodies. How much is too much salt and how mow much is too little?

Without salt and water - our cells would die of dehydration.

Without salt and water - our cells would die of dehydration.

The book referred to this publication by Diamond:

Vintage Recipes: 101 Uses For Salt 1926 Diamond Crystal Salt

https://antiquealterego.com/2013/10/1...

Vintage Recipes: 101 Uses For Salt 1926 Diamond Crystal Salt

https://antiquealterego.com/2013/10/1...

In the introduction - Kurlansky tells us that salt is the only family of rocks that are eaten by humans. Now we think that salt is plentiful but in ancient times and even up until a hundred years ago - salt was one of the most sought after commodities in history.

Salt on the plains of Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia. Sergio Ballivian / Getty Images

https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJourna...

How salt forms in nature

https://www.thoughtco.com/all-about-s...

Source: Salt Company

Salt on the plains of Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia. Sergio Ballivian / Getty Images

https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJourna...

How salt forms in nature

https://www.thoughtco.com/all-about-s...

Source: Salt Company

Egyptians used salt for mummification: (Kurlansky writes in the Introduction)

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanitie...

Source: Khan Academy

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanitie...

Source: Khan Academy

Mark Kurlansky on the Cultural Importance of Salt

Salt, it may be useful to know, cures a zombie

Read more: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-c...

Source: The Smithsonian

Salt, it may be useful to know, cures a zombie

Read more: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-c...

Source: The Smithsonian

I am about to begin Part One: A Discourse on Salt, Cadavers and Pungent Sauces - has anyone started the book and what are you thoughts and what have you found surprising?

In a Free Read - there are no schedules, no stress, no date to begin or finish - you just read along and finish when you can. Who has started the book - let me know.

Of course, there are no schedules so I will get to the next part when I can - the book is interesting so far.

In a Free Read - there are no schedules, no stress, no date to begin or finish - you just read along and finish when you can. Who has started the book - let me know.

Of course, there are no schedules so I will get to the next part when I can - the book is interesting so far.

'World's longest salt cave' discovered in Israel

Link: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle...

Source: BBC News

Link: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle...

Source: BBC News

It begins with the author standing or a rice paddy in rural Sichuan province, China.

Wild China - BBC

BBC - Wild China - Heart of the Dragon

https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x2y...

The Chinese did in fact create a lot of inventions and firsts - paper making, printing, gun powder and the compass. Oldest literate civilization in existence. Although in rural China they may need some new inventions.

Mao Zedong

Source: Daily Motion

Wild China - BBC

BBC - Wild China - Heart of the Dragon

https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x2y...

The Chinese did in fact create a lot of inventions and firsts - paper making, printing, gun powder and the compass. Oldest literate civilization in existence. Although in rural China they may need some new inventions.

Mao Zedong

Source: Daily Motion

Pangu

Pangu (simplified Chinese: 盘古; traditional Chinese: 盤古; pinyin: Pángǔ; Wade–Giles: P'an-ku) is the first living being and the creator of all in some versions of Chinese mythology.

Remainder of article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pangu

Source: Wikipedia

by E.T.C. Werner (no photo)

by E.T.C. Werner (no photo)

Pangu (simplified Chinese: 盘古; traditional Chinese: 盤古; pinyin: Pángǔ; Wade–Giles: P'an-ku) is the first living being and the creator of all in some versions of Chinese mythology.

Remainder of article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pangu

Source: Wikipedia

by E.T.C. Werner (no photo)

by E.T.C. Werner (no photo)

Salt: An Ancient Chinese Commodity

Like it or not, everyone needs to consume some salt. Know it or not, the Chinese were early pioneers in drilling, panning, and consuming their share. Salt is a basic taste (as are sweet, sour, bitter, and the newest one named with a Japanese word, umami, which translates as 'savory'). Sodium is one of salt's components, the other is chloride, hence its chemical name is simply 'sodium chloride.'

Chinese salt history probably began with the Yellow Emperor Huangdi. At the least, he is credited with presiding over the first war ever fought over salt. One of the earliest verifiable salt works was in prehistoric China in the northern province of Shanxi. It was at Lake Yincheng in a mountainous and desert area. Chinese historians believe that by 6,000 BCE and at summer’s end, people gathered crystals of salt found in tropical climate areas. These were probably on the edges of lakes and other saline water sources.

Little is known where else salt was first found, how it was used, or even if or how it was exploited in early China. One Chinese record, circa 2,000 BCE, shows preserving fish in salt. Another speaks of an Emperor Yu, a few years earlier, attempting to control and tax salt in his domain. Still another dates different salt usage from about 800 BCE and of the salt trade occurring a millennium earlier during the Xia dynasty (21st century to 16th century BCE). Yet still another says that salt was mined five hundred years after iron was used in China and that was recorded as about 1,000 BCE. Still one more says that Yi Dun, in 450 BCE, produced salt by boiling brine in iron pans.

Some salt production came from underground pools of salty water. From them, the salted water was poured out of long bamboo buckets ingeniously brought up from great depths. One reads about twenty percent of China’s salt coming from famous wells in the Sichuan area near the Fuxi River, a tributary of the Yangtze. The first wells in Sichuan were drilled to great depths in 252 BCE on orders of the then governor Li Bing. He saw to it that they used bamboo piping because it was resistant to rotting and no doubt protected by the very water it was bringing to the surface.

At these same wells some two to three hundred years later, the Chinese used the gas coming from holes nearby and next to where the brine came up. Because it made many workers sick, this gas was deemed evil. A bit later, they figured out that the best thing to do was ignite that gas, and then all illness ceased. The Chinese learned to cook over the flames from the gas. This may have been the first use of natural gas.

In early times, salt was rare and reserved for the Emperor. Early usage by his court was relegated to food preservation. Later, as salt was costly and subject to considerable taxation it was used sparingly. China was not alone in imposing salt taxes. Athens, Rome, France, Mexico, and others did, too. Today salt is tax-free, inexpensive, commonplace, available to all, it can be had in many colors, kinds, and crystal types. That is a big change from early salt usage.

Did you know that salt cakes were once money? Circa 1300 CE, salt was more readily available and that unusual tender went out of fashion. However, in those days while it was less difficult to acquire, it was still tough to collect its taxes from producer to consumer. Taxation certainly was as ancient at its earliest acquisition, using it as money a more modern usage.

Collecting monies to transport this economically precious commodity began about the 20th century BCE. Using it as money came three thousand years later. One historian wrote of forty-two different taxes collected just to take salt across the entire Hubei Province. He did not mention what a cake was worth, as money or for anything else about its economics.

As a government monopoly, elite salt merchants were selected and authorized to collect taxes on salt. They made a bundle and became rich. Suzhou''s famous gardens were built by salt merchant families. Many, among the forty thousand or so in the salt trade were corrupt. Strange Tales in a Chinese Studio (1877) by Herbert Giles is one of the best books to detail early Chinese salt trading. If you can locate a library with a copy, do read it.

These days, Chinese people consume a lot of salt, one report says more than twenty pounds per person per year. In the United States, about three-quarters of that amount is ingested and that amount is thought to be unhealthy. There are major differences in how and where salt is eaten, how much is actually consumed, and also in where salt is found.

High in the Gobi desert in Golmud which is in China’s northwest province of Qinghai, there are twenty salt lakes and the government is planning to build many industries involving salt and salt-lake chemicals there. At the largest inland salt lake in the world, Lake Qarham, they are already producing lots of salt. Uses for this or any salt in China and in the United States differs. In the United States a large amount of salt is found in canned foods, in packaged products, and in otherwise commercially prepared commodities. And, it is poured extensively and in large quantities on foods at the table. Diners do so just before eating.

This type of use was unknown in early China, and hardly done today. The Chinese main use was and is for preserving vegetables, salting fish, and pickling and preserving all types of animal flesh. Rarely in times of old did they or do they now put salt on foods at the table. This idea of producing saltiness through direct use of salt is uncommon and uncalled for in China. Instead, the Chinese use numerous salted condiments, the most important today is soy sauce.

For some years, salt had a bad rap in the Western world. Not so for the Chinese in or outside of China. Times have changed and nowadays some in the United States say that salt may not lead to high blood pressure, that is, unless a person is sodium sensitive. The University of California (at Berkeley) Newsletter, says it still makes sense to consume less than 2,400 mg per day. That amount is a little more than a teaspoon, and it is about twice what American Dietitians recommend. Nonetheless, do not shake your salt cellar with abandon because all too many food manufacturers already did. Their products are loaded with salt.

Salt is not the same as it was in yesteryear. Most is now purified removing other minerals. The World Health Organization and UNICEF urge salt producers worldwide to add iodine to their salt to avoid a disease called goiter. This disease produces an enlargement of the thyroid gland and because of iodine’s addition, the disease is virtually eliminated. In many regions of China, they also add selenium to their salt. The purpose is, they say, to reduce cancer and heart-related problems.

In 1998, the Chinese government's Salt Corporation sealed the last well in the Sichuan Province. They ruled that salt from there was sub-standard. Nearby in Zigong, they still produce a little because people long for salt that is more irregular, less pure, and certainly without iodine. They say that the iodine gives their pickled products a peculiar taste. Many people in the United States, refrain from using iodized salt, as well, not appreciating the taste and texture of the resulting pickled products.

In China, they illustrate poor results with iodized salt and mention Larou, a traditional and popular pork dish made by curing pork. It, they claim, tastes better when made with salt that has no iodine. The Chinese make Larou by cutting pork into pieces and covering it with naturally mined unadulterated non-iodized salt. They add some spices and leave the pork a week, then wash it well to remove any residual salt. The pork is hung over a charcoal fire, with or without peanut shells and sugarcane used as the fuel, and they smoke the pork for two days.

Chinese do not salt their food at the table because they believe that producing the salty flavor is the job of the cook, not the consumer. Most salt in their food comes from adding one or more jiang or fermented sauces. The cook adds one or more of them, be the food he or she is preparing one hundred percent vegetarian or made with fish or meat. Years ago, the earliest fermented sauces were actually made with meat. They were not made with soybeans. Traditionally, the meat was layered with salt in earthen jars or pickled in brine. The best way was to put the animal flesh between layers of salt, then seal it. Soybeans added to these sauces came lots later, and when they did begin to be used, they were first added to fish, then fermented together. This was called jiang yu.

The earthen jars of fish and salt were sealed then placed in a sunny location for some days then moved to cooler places, often inside the doorway of a house. There, they could be doused with buckets of water should the weather or the temperature of the jar get too hot. The jars would stay a year or two, or more, and then be unsealed when/as needed. Not wanting to waste a thing, liquids taken from these jars were the earliest fermented sauces. They were used to flavor foods cooked or marinated.

In the Sichuan province, many different vegetables were also pickled in salt or brine. They still are. These staples can be made two very popular ways, pao cai or zha cai. And they have been for at least three thousand years. Both techniques are still in use, and the vegetables preserved these ways taste great and are great appetite stimulants.

To make pao cai, vegetables are washed and dried somewhat, then put into brine and kept a day or two, not much more. Then they are rinsed and served plain or cooked with other foods. The zha cai method is more complex. The vegetables need to be washed and dried, then layered salt, vegetable, salt, etc. This is done in earthen jars that are sealed and left to pickle, which is another name for the fermenting process. Made this way, zha cai can stay for years. Some farmer families put up an extra jar each year for each girl in the family. They want her to take them with when she gets married.

Not all jars are sealed. Some, particularly the vegetable ones, are only covered with fabric or a plate. As such, they need attention every couple of weeks. The cloth or loose top on them needs to be removed and washed to get rid of a harmless white topping called kahm, the yeast forming there. After removing it and washing the cloth and/or the cover, the vegetables are covered again. The role of salt in this and all pickling is important. Without it, the carbohydrate or protein in the food putrefies. One result can be an alcoholic product, another can be a lethal one.

Eggs were and are also put up in salt. Some are soaked in brine, then put into mud and straw. Others, soaked or not, are packed in salt, ash, lye, and sometimes tea leaves. The mud/straw ones make for gelatinized eggs with a deep orange yolk. The ones packed in ash and lye produce eggs with a blackened white, a greenish yolk, a strong aroma, and a mild flavor. You may know these as pi dan or 'thousand year' eggs. You may have read about them in Irving Beilin Chang’s article in Flavor and Fortune called 'Duck-boys, Duck-eggs, and Egg Chemists' in Volume 9(1) on ages 9 and 10, or elsewhere.

In actuality, the eggs are ready to eat in ninety to one hundred days. The time misnomer may have started with an early mistranslation. Westerners put a comma after three zeros, the Chinese put theirs after four zero''s, so hundred day eggs were called thousand year eggs.

Remainder of article:

http://www.flavorandfortune.com/dataa...

Source: Flavor and Fortune

More:

by

by

Pu Songling

Pu Songling

Like it or not, everyone needs to consume some salt. Know it or not, the Chinese were early pioneers in drilling, panning, and consuming their share. Salt is a basic taste (as are sweet, sour, bitter, and the newest one named with a Japanese word, umami, which translates as 'savory'). Sodium is one of salt's components, the other is chloride, hence its chemical name is simply 'sodium chloride.'

Chinese salt history probably began with the Yellow Emperor Huangdi. At the least, he is credited with presiding over the first war ever fought over salt. One of the earliest verifiable salt works was in prehistoric China in the northern province of Shanxi. It was at Lake Yincheng in a mountainous and desert area. Chinese historians believe that by 6,000 BCE and at summer’s end, people gathered crystals of salt found in tropical climate areas. These were probably on the edges of lakes and other saline water sources.

Little is known where else salt was first found, how it was used, or even if or how it was exploited in early China. One Chinese record, circa 2,000 BCE, shows preserving fish in salt. Another speaks of an Emperor Yu, a few years earlier, attempting to control and tax salt in his domain. Still another dates different salt usage from about 800 BCE and of the salt trade occurring a millennium earlier during the Xia dynasty (21st century to 16th century BCE). Yet still another says that salt was mined five hundred years after iron was used in China and that was recorded as about 1,000 BCE. Still one more says that Yi Dun, in 450 BCE, produced salt by boiling brine in iron pans.

Some salt production came from underground pools of salty water. From them, the salted water was poured out of long bamboo buckets ingeniously brought up from great depths. One reads about twenty percent of China’s salt coming from famous wells in the Sichuan area near the Fuxi River, a tributary of the Yangtze. The first wells in Sichuan were drilled to great depths in 252 BCE on orders of the then governor Li Bing. He saw to it that they used bamboo piping because it was resistant to rotting and no doubt protected by the very water it was bringing to the surface.

At these same wells some two to three hundred years later, the Chinese used the gas coming from holes nearby and next to where the brine came up. Because it made many workers sick, this gas was deemed evil. A bit later, they figured out that the best thing to do was ignite that gas, and then all illness ceased. The Chinese learned to cook over the flames from the gas. This may have been the first use of natural gas.

In early times, salt was rare and reserved for the Emperor. Early usage by his court was relegated to food preservation. Later, as salt was costly and subject to considerable taxation it was used sparingly. China was not alone in imposing salt taxes. Athens, Rome, France, Mexico, and others did, too. Today salt is tax-free, inexpensive, commonplace, available to all, it can be had in many colors, kinds, and crystal types. That is a big change from early salt usage.

Did you know that salt cakes were once money? Circa 1300 CE, salt was more readily available and that unusual tender went out of fashion. However, in those days while it was less difficult to acquire, it was still tough to collect its taxes from producer to consumer. Taxation certainly was as ancient at its earliest acquisition, using it as money a more modern usage.

Collecting monies to transport this economically precious commodity began about the 20th century BCE. Using it as money came three thousand years later. One historian wrote of forty-two different taxes collected just to take salt across the entire Hubei Province. He did not mention what a cake was worth, as money or for anything else about its economics.

As a government monopoly, elite salt merchants were selected and authorized to collect taxes on salt. They made a bundle and became rich. Suzhou''s famous gardens were built by salt merchant families. Many, among the forty thousand or so in the salt trade were corrupt. Strange Tales in a Chinese Studio (1877) by Herbert Giles is one of the best books to detail early Chinese salt trading. If you can locate a library with a copy, do read it.

These days, Chinese people consume a lot of salt, one report says more than twenty pounds per person per year. In the United States, about three-quarters of that amount is ingested and that amount is thought to be unhealthy. There are major differences in how and where salt is eaten, how much is actually consumed, and also in where salt is found.

High in the Gobi desert in Golmud which is in China’s northwest province of Qinghai, there are twenty salt lakes and the government is planning to build many industries involving salt and salt-lake chemicals there. At the largest inland salt lake in the world, Lake Qarham, they are already producing lots of salt. Uses for this or any salt in China and in the United States differs. In the United States a large amount of salt is found in canned foods, in packaged products, and in otherwise commercially prepared commodities. And, it is poured extensively and in large quantities on foods at the table. Diners do so just before eating.

This type of use was unknown in early China, and hardly done today. The Chinese main use was and is for preserving vegetables, salting fish, and pickling and preserving all types of animal flesh. Rarely in times of old did they or do they now put salt on foods at the table. This idea of producing saltiness through direct use of salt is uncommon and uncalled for in China. Instead, the Chinese use numerous salted condiments, the most important today is soy sauce.

For some years, salt had a bad rap in the Western world. Not so for the Chinese in or outside of China. Times have changed and nowadays some in the United States say that salt may not lead to high blood pressure, that is, unless a person is sodium sensitive. The University of California (at Berkeley) Newsletter, says it still makes sense to consume less than 2,400 mg per day. That amount is a little more than a teaspoon, and it is about twice what American Dietitians recommend. Nonetheless, do not shake your salt cellar with abandon because all too many food manufacturers already did. Their products are loaded with salt.

Salt is not the same as it was in yesteryear. Most is now purified removing other minerals. The World Health Organization and UNICEF urge salt producers worldwide to add iodine to their salt to avoid a disease called goiter. This disease produces an enlargement of the thyroid gland and because of iodine’s addition, the disease is virtually eliminated. In many regions of China, they also add selenium to their salt. The purpose is, they say, to reduce cancer and heart-related problems.

In 1998, the Chinese government's Salt Corporation sealed the last well in the Sichuan Province. They ruled that salt from there was sub-standard. Nearby in Zigong, they still produce a little because people long for salt that is more irregular, less pure, and certainly without iodine. They say that the iodine gives their pickled products a peculiar taste. Many people in the United States, refrain from using iodized salt, as well, not appreciating the taste and texture of the resulting pickled products.

In China, they illustrate poor results with iodized salt and mention Larou, a traditional and popular pork dish made by curing pork. It, they claim, tastes better when made with salt that has no iodine. The Chinese make Larou by cutting pork into pieces and covering it with naturally mined unadulterated non-iodized salt. They add some spices and leave the pork a week, then wash it well to remove any residual salt. The pork is hung over a charcoal fire, with or without peanut shells and sugarcane used as the fuel, and they smoke the pork for two days.

Chinese do not salt their food at the table because they believe that producing the salty flavor is the job of the cook, not the consumer. Most salt in their food comes from adding one or more jiang or fermented sauces. The cook adds one or more of them, be the food he or she is preparing one hundred percent vegetarian or made with fish or meat. Years ago, the earliest fermented sauces were actually made with meat. They were not made with soybeans. Traditionally, the meat was layered with salt in earthen jars or pickled in brine. The best way was to put the animal flesh between layers of salt, then seal it. Soybeans added to these sauces came lots later, and when they did begin to be used, they were first added to fish, then fermented together. This was called jiang yu.

The earthen jars of fish and salt were sealed then placed in a sunny location for some days then moved to cooler places, often inside the doorway of a house. There, they could be doused with buckets of water should the weather or the temperature of the jar get too hot. The jars would stay a year or two, or more, and then be unsealed when/as needed. Not wanting to waste a thing, liquids taken from these jars were the earliest fermented sauces. They were used to flavor foods cooked or marinated.

In the Sichuan province, many different vegetables were also pickled in salt or brine. They still are. These staples can be made two very popular ways, pao cai or zha cai. And they have been for at least three thousand years. Both techniques are still in use, and the vegetables preserved these ways taste great and are great appetite stimulants.

To make pao cai, vegetables are washed and dried somewhat, then put into brine and kept a day or two, not much more. Then they are rinsed and served plain or cooked with other foods. The zha cai method is more complex. The vegetables need to be washed and dried, then layered salt, vegetable, salt, etc. This is done in earthen jars that are sealed and left to pickle, which is another name for the fermenting process. Made this way, zha cai can stay for years. Some farmer families put up an extra jar each year for each girl in the family. They want her to take them with when she gets married.

Not all jars are sealed. Some, particularly the vegetable ones, are only covered with fabric or a plate. As such, they need attention every couple of weeks. The cloth or loose top on them needs to be removed and washed to get rid of a harmless white topping called kahm, the yeast forming there. After removing it and washing the cloth and/or the cover, the vegetables are covered again. The role of salt in this and all pickling is important. Without it, the carbohydrate or protein in the food putrefies. One result can be an alcoholic product, another can be a lethal one.

Eggs were and are also put up in salt. Some are soaked in brine, then put into mud and straw. Others, soaked or not, are packed in salt, ash, lye, and sometimes tea leaves. The mud/straw ones make for gelatinized eggs with a deep orange yolk. The ones packed in ash and lye produce eggs with a blackened white, a greenish yolk, a strong aroma, and a mild flavor. You may know these as pi dan or 'thousand year' eggs. You may have read about them in Irving Beilin Chang’s article in Flavor and Fortune called 'Duck-boys, Duck-eggs, and Egg Chemists' in Volume 9(1) on ages 9 and 10, or elsewhere.

In actuality, the eggs are ready to eat in ninety to one hundred days. The time misnomer may have started with an early mistranslation. Westerners put a comma after three zeros, the Chinese put theirs after four zero''s, so hundred day eggs were called thousand year eggs.

Remainder of article:

http://www.flavorandfortune.com/dataa...

Source: Flavor and Fortune

More:

by

by

Pu Songling

Pu Songling

Magnificent scene of workers mining salt in the famous salt lake in Yuncheng, Shanxi.

Magnificent scene of workers mining salt in the famous salt lake in Yuncheng, Shanxi. The technique of salt mining has existed for thousands years.

Link: 1,300-year-old salt production returns to "China's Dead Sea"

https://youtu.be/F90iI9NZkpM

Source: Youtube

Magnificent scene of workers mining salt in the famous salt lake in Yuncheng, Shanxi. The technique of salt mining has existed for thousands years.

Link: 1,300-year-old salt production returns to "China's Dead Sea"

https://youtu.be/F90iI9NZkpM

Source: Youtube

Zhou Dynasty - 1000BC - Iron came into use in China

http://apworldhistory101.com/history-...

Source: Youtube

http://apworldhistory101.com/history-...

Source: Youtube

Oldest method of salt production seen in Tibet

Using Salt Pans - Oldest method of salt production seen in Tibet

A villager works on salt pans in Markam county, Southwest China's Tibet autonomous region, March 21, 2015.[Photo/Xinhua]

Link: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/culture/...

Source: China Daily

Using Salt Pans - Oldest method of salt production seen in Tibet

A villager works on salt pans in Markam county, Southwest China's Tibet autonomous region, March 21, 2015.[Photo/Xinhua]

Link: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/culture/...

Source: China Daily

A 750-Year-Old Secret: See How Soy Sauce Is Still Made Today | Short Film Showcase

See how Japanese soy sauce has been made for 750 years in this fascinating short film by Mile Nagaoka. This was originally gotten from China.

https://youtu.be/EMmyamL4VGw

Source: Youtube and National Geographic

See how Japanese soy sauce has been made for 750 years in this fascinating short film by Mile Nagaoka. This was originally gotten from China.

https://youtu.be/EMmyamL4VGw

Source: Youtube and National Geographic

All, I am posting references to topics discussed in Chapter One - A Mandate of Salt

The author appears to be going through the history of salt beginning in China in this chapter.

The author appears to be going through the history of salt beginning in China in this chapter.

I have completed chapter one and it appears to be the history of salt in ancient China. I will add references that reflect Chapter One and the history.

Here is a history of salt in ancient China.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salt_in...

Source: Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salt_in...

Source: Wikipedia

This is sort of a summary of what Kurlansky is covering in Chapter One:

Salt

Salt--sodium chloride--is absolutely necessary to the functioning of the human body at the cellular level. Think about all the liquids that flow within and from human bodies: blood, mucus, tears, sweat, urine, and semen. They’re all salty.

The fact that they flow from the body means that humans constantly lose salt. Therefore salt is a necessity; pepper is always a luxury.

Humans who adopted agriculture--remember that probably 80% or more of their calories came from a starchy plant (grains or tubers)--had a lot less salt in their regular diets, so they needed to find additional sources of salt to survive.

Farmers with domesticated animals which could not roam free to find salt licks also needed to supply salt to their livestock (often several times a human’s salt needs). Pastoralists and foragers often consumed enough salt normally in their diets, so they rarely needed to find extra.

Salt had other uses. Salt could be used to preserve foods that otherwise might have rotted: think dried fish and bacon, pickles and olives, and cheese.

Salt is also a tool for “controlled rotting” in foods like kimchee, fish sauce, soy sauce, tofu, and sauerkraut.

Stored food that does not spoil is vital to farmers who cannot grow their crops year-round. Mummification, medicines, the processing of leather, and smelting metals also required certain salts.

Getting and Making Salt

Natural salt deposits often lie underground, particularly in deserts, so it may be mined. Natural evaporation pans (pools at the sea shore or lakes in arid regions) are a very useful means of getting salt.

As long as the area is dry and sunny, the sun itself puts in the energy necessary to evaporate the water and leave the salt behind.

However, if an area is wet, cool, and/or cloudy, human inputs of energy are required to evaporate the water. In these cases, the costs of fuel have an impact on the cost of the end product of salt.

As two scholars argue, “Salt production, in many ways, was the world’s first industry.” In some inland areas, salt-water springs flow from the earth, and these are often places where human settlements appear.

People can also burn some sorts of vegetation, and by processing the ashes produce salt.

Since salt was essential to the lives of all farmers, governments realized it was a good commodity to tax, since a salt tax would ensure a perpetual revenue.

In many cases, the production and distribution of salt was critical to state power. “[S]alt touched on almost every aspect of the lives of most pre-modern farming societies.

The availability and variety of salt could determine the types of food people ate. Efforts to produce salt could encourage technological innovation and influence the nature and allocation of labor.

Trade linkages that brought salt could also lead to substantial cultural exchange between societies. And finally, salt could play a critical role in determining the very nature of the relationship between the rulers and the ruled.”

In the Ancient Roman Empire

Rome itself might have been established (6th century BCE) as a salt-trading center. Humans made salt ponds on the edge of the Mediterranean and mined it in the Alps. For salt production, the Romans were not inventive, but they borrowed any useful techniques from the peoples they conquered.

Romans salted their fresh foods typically in two ways. Most meals were served with a fermented fish sauce (called garum or liquimen) as a condiment.

Greens that were eaten were typically salted; this is the origin of the English word “salad.” Salt-soaked olives were eaten by all classes of Romans, but they were a staple food for plebeians and slaves. Elaborate silver saltcellars were fashioned and purchased to show off wealth at the table.

“Salarium argentum,” or the salt money paid to Roman soldiers as part of their wage, persists in the English language in the word “salary.” The cliché “worth his salt” has origins in this time.

Horses in the large Roman army needed salt, too. The cost of salt sometimes was subsidized by the Roman government to gain popular support, since the price went down for commoners.

At other times, the Roman government (like during the Punic wars in the 2nd century BCE) intervened in price-setting to raise extra taxes, very much like contemporaneous Chinese governments.

The Punic wars were intended to destroy the Phoenician trading network. The purple dye that Phoenicians traded which gave them their name was actually extracted by salting a particular shellfish.

This process took long enough (and so many mollusks) that purple dye was very rare in large quantities, and therefore became something only the elite wore in the Mediterranean.

Once the Romans conquered the Phoenician city-states they discovered this secret process. Julius Caesar outlawed purple clothes for anyone outside his family (1st century BCE).

In Ancient China

The earliest written records for Chinese salt production date from around 800 BCE.

Iron pans--some as large as ten feet in diameter--came into use for making salt roughly contemporaneous with Confucius (5th century BCE). Mencius (4th century BCE), one of the more famous Confucian scholars, was allegedly a salt-merchant as well (interesting considering Confucian dogma regarding trade).

The production of salt led to much technological innovation in ancient (and medieval) China. In the Sichuan (Szechuan) province in the middle of the 3rd century BCE (252), a government official by the name of Li Bing realized that standalone salty pools were getting their salt from somewhere underground.

He began to organize digging--which eventually turned into drilling--to acquire that salt. Soon the mineshafts were sunk to 300 feet underground.

Trouble soon befell the miners sent underground: they would get weak, fall unconscious, and die. Every once and a while the mines would explode in flame, killing the workers.

This was blamed on evil spirits escaping, but eventually, by 100 CE, the Chinese learned to control these “spirits,” which were, of course, natural gas.

They lit flames at the surface where the gas was escaping, and since these were perpetual fires, began to use this “free” energy to cook and boil salt brine.

Shortly thereafter elaborate bamboo pipe systems were constructed to send the natural gas some distance from the mines (very much like gas stoves in the present, only without much in the way of shutoff valves).

(This bamboo piping technology spread to other parts of China, and used in elaborate urban plumbing systems by the year 1000 CE). These natural gas works were efficient enough that they continued to be used into the 20th century (CE).

The seven necessities of daily Chinese peasant life were named as firewood, grain, oil, salt, soy sauce, vinegar, and tea. Like the Romans, the ancient Chinese initially used fish sauce or paste, but eventually substituted fermented and salted soy sauce in their cuisine. Pickled vegetables and eggs--made with salt--were vital to the Chinese diet.

Chinese officials often organized the production of salt, and required families in salt-producing areas to manufacture a particular quota each year, effectively taxing their labor for the government. Because cooking up salt required a lot of carefully-timed procedures, this work could consume the whole family for weeks.

One of the early Chinese pictographs for salt was essentially an abstract drying pan.

By the Han era (2nd century BCE), the word for salt included an abstract government official, suggesting that salt and the government are inseparable.

The Legalists--whose ideology was ascendant in the 3rd century BCE--advocated fixing a price for salt, but allowing the government to buy it at a lower price, using the profit when sold to the population as the tax.

This may have been the first state-controlled monopoly of a vital commodity when it was implemented under the rule of the short-lived Qin Dynasty.

The revenues went to pay soldiers’ salaries and to fund the construction of the early elements of the Great Wall.

The Chinese government’s salt monopoly came and went depending on prevailing ideas of what good government was and the needs of the state to scare up additional revenue.

For example, when the Xiongnu pastoralists continued to threaten the Han frontier in 120 BCE, and the government had spent most of its cash, it re-established the monopoly on selling salt (and added monopolies on iron, wine, and beer).

Although this tax was very effective, the state organized a scholarly debate on the necessity of the salt monopoly in 81 BCE. When the monopolies were in force, there were drawbacks. Prices for salt went up, of course, so many smuggled salt and some Chinese subjects even turned to banditry of government salt caravans.

Sources: Mark Kurlansky, Salt: A World History (2003); Erik Gilbert and Jonathan Reynolds, Trading Tastes (2006) and http://users.rowan.edu/~mcinneshin/10...

by Erik Gilbert (no photo)

by Erik Gilbert (no photo)

Salt

Salt--sodium chloride--is absolutely necessary to the functioning of the human body at the cellular level. Think about all the liquids that flow within and from human bodies: blood, mucus, tears, sweat, urine, and semen. They’re all salty.

The fact that they flow from the body means that humans constantly lose salt. Therefore salt is a necessity; pepper is always a luxury.

Humans who adopted agriculture--remember that probably 80% or more of their calories came from a starchy plant (grains or tubers)--had a lot less salt in their regular diets, so they needed to find additional sources of salt to survive.

Farmers with domesticated animals which could not roam free to find salt licks also needed to supply salt to their livestock (often several times a human’s salt needs). Pastoralists and foragers often consumed enough salt normally in their diets, so they rarely needed to find extra.

Salt had other uses. Salt could be used to preserve foods that otherwise might have rotted: think dried fish and bacon, pickles and olives, and cheese.

Salt is also a tool for “controlled rotting” in foods like kimchee, fish sauce, soy sauce, tofu, and sauerkraut.

Stored food that does not spoil is vital to farmers who cannot grow their crops year-round. Mummification, medicines, the processing of leather, and smelting metals also required certain salts.

Getting and Making Salt

Natural salt deposits often lie underground, particularly in deserts, so it may be mined. Natural evaporation pans (pools at the sea shore or lakes in arid regions) are a very useful means of getting salt.

As long as the area is dry and sunny, the sun itself puts in the energy necessary to evaporate the water and leave the salt behind.

However, if an area is wet, cool, and/or cloudy, human inputs of energy are required to evaporate the water. In these cases, the costs of fuel have an impact on the cost of the end product of salt.

As two scholars argue, “Salt production, in many ways, was the world’s first industry.” In some inland areas, salt-water springs flow from the earth, and these are often places where human settlements appear.

People can also burn some sorts of vegetation, and by processing the ashes produce salt.

Since salt was essential to the lives of all farmers, governments realized it was a good commodity to tax, since a salt tax would ensure a perpetual revenue.

In many cases, the production and distribution of salt was critical to state power. “[S]alt touched on almost every aspect of the lives of most pre-modern farming societies.

The availability and variety of salt could determine the types of food people ate. Efforts to produce salt could encourage technological innovation and influence the nature and allocation of labor.

Trade linkages that brought salt could also lead to substantial cultural exchange between societies. And finally, salt could play a critical role in determining the very nature of the relationship between the rulers and the ruled.”

In the Ancient Roman Empire

Rome itself might have been established (6th century BCE) as a salt-trading center. Humans made salt ponds on the edge of the Mediterranean and mined it in the Alps. For salt production, the Romans were not inventive, but they borrowed any useful techniques from the peoples they conquered.

Romans salted their fresh foods typically in two ways. Most meals were served with a fermented fish sauce (called garum or liquimen) as a condiment.

Greens that were eaten were typically salted; this is the origin of the English word “salad.” Salt-soaked olives were eaten by all classes of Romans, but they were a staple food for plebeians and slaves. Elaborate silver saltcellars were fashioned and purchased to show off wealth at the table.

“Salarium argentum,” or the salt money paid to Roman soldiers as part of their wage, persists in the English language in the word “salary.” The cliché “worth his salt” has origins in this time.

Horses in the large Roman army needed salt, too. The cost of salt sometimes was subsidized by the Roman government to gain popular support, since the price went down for commoners.

At other times, the Roman government (like during the Punic wars in the 2nd century BCE) intervened in price-setting to raise extra taxes, very much like contemporaneous Chinese governments.

The Punic wars were intended to destroy the Phoenician trading network. The purple dye that Phoenicians traded which gave them their name was actually extracted by salting a particular shellfish.

This process took long enough (and so many mollusks) that purple dye was very rare in large quantities, and therefore became something only the elite wore in the Mediterranean.

Once the Romans conquered the Phoenician city-states they discovered this secret process. Julius Caesar outlawed purple clothes for anyone outside his family (1st century BCE).

In Ancient China

The earliest written records for Chinese salt production date from around 800 BCE.

Iron pans--some as large as ten feet in diameter--came into use for making salt roughly contemporaneous with Confucius (5th century BCE). Mencius (4th century BCE), one of the more famous Confucian scholars, was allegedly a salt-merchant as well (interesting considering Confucian dogma regarding trade).

The production of salt led to much technological innovation in ancient (and medieval) China. In the Sichuan (Szechuan) province in the middle of the 3rd century BCE (252), a government official by the name of Li Bing realized that standalone salty pools were getting their salt from somewhere underground.

He began to organize digging--which eventually turned into drilling--to acquire that salt. Soon the mineshafts were sunk to 300 feet underground.

Trouble soon befell the miners sent underground: they would get weak, fall unconscious, and die. Every once and a while the mines would explode in flame, killing the workers.

This was blamed on evil spirits escaping, but eventually, by 100 CE, the Chinese learned to control these “spirits,” which were, of course, natural gas.

They lit flames at the surface where the gas was escaping, and since these were perpetual fires, began to use this “free” energy to cook and boil salt brine.

Shortly thereafter elaborate bamboo pipe systems were constructed to send the natural gas some distance from the mines (very much like gas stoves in the present, only without much in the way of shutoff valves).

(This bamboo piping technology spread to other parts of China, and used in elaborate urban plumbing systems by the year 1000 CE). These natural gas works were efficient enough that they continued to be used into the 20th century (CE).

The seven necessities of daily Chinese peasant life were named as firewood, grain, oil, salt, soy sauce, vinegar, and tea. Like the Romans, the ancient Chinese initially used fish sauce or paste, but eventually substituted fermented and salted soy sauce in their cuisine. Pickled vegetables and eggs--made with salt--were vital to the Chinese diet.

Chinese officials often organized the production of salt, and required families in salt-producing areas to manufacture a particular quota each year, effectively taxing their labor for the government. Because cooking up salt required a lot of carefully-timed procedures, this work could consume the whole family for weeks.

One of the early Chinese pictographs for salt was essentially an abstract drying pan.

By the Han era (2nd century BCE), the word for salt included an abstract government official, suggesting that salt and the government are inseparable.

The Legalists--whose ideology was ascendant in the 3rd century BCE--advocated fixing a price for salt, but allowing the government to buy it at a lower price, using the profit when sold to the population as the tax.

This may have been the first state-controlled monopoly of a vital commodity when it was implemented under the rule of the short-lived Qin Dynasty.

The revenues went to pay soldiers’ salaries and to fund the construction of the early elements of the Great Wall.

The Chinese government’s salt monopoly came and went depending on prevailing ideas of what good government was and the needs of the state to scare up additional revenue.

For example, when the Xiongnu pastoralists continued to threaten the Han frontier in 120 BCE, and the government had spent most of its cash, it re-established the monopoly on selling salt (and added monopolies on iron, wine, and beer).

Although this tax was very effective, the state organized a scholarly debate on the necessity of the salt monopoly in 81 BCE. When the monopolies were in force, there were drawbacks. Prices for salt went up, of course, so many smuggled salt and some Chinese subjects even turned to banditry of government salt caravans.

Sources: Mark Kurlansky, Salt: A World History (2003); Erik Gilbert and Jonathan Reynolds, Trading Tastes (2006) and http://users.rowan.edu/~mcinneshin/10...

by Erik Gilbert (no photo)

by Erik Gilbert (no photo)

Li Bing

Statue of Li Bing at Erwang Temple, Dujiangyan, sculpted during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD)

Li Bing (Chinese: 李冰; pinyin: Lǐ Bīng; c. 3rd century BC) was a Chinese irrigation engineer and politician of the Warring States period. He served the state of Qin as an administrator and has become renowned for his association with the Dujiangyan Irrigation System, the construction of which he is traditionally said to have instigated and overseen.

Because of the importance of this 2000-year-old irrigation system to the development of Sichuan and the Yangtze River region, Li Bing became a great Chinese cultural icon, hailed as a great civil administrator and water conservation expert.

In Chinese mythology, he is known as the vanquisher of the River God and is compared to the Great Yu. Dujiangyan is still in use today and is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Remainder of article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Li_Bing

Source: Wikipedia

Statue of Li Bing at Erwang Temple, Dujiangyan, sculpted during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD)

Li Bing (Chinese: 李冰; pinyin: Lǐ Bīng; c. 3rd century BC) was a Chinese irrigation engineer and politician of the Warring States period. He served the state of Qin as an administrator and has become renowned for his association with the Dujiangyan Irrigation System, the construction of which he is traditionally said to have instigated and overseen.

Because of the importance of this 2000-year-old irrigation system to the development of Sichuan and the Yangtze River region, Li Bing became a great Chinese cultural icon, hailed as a great civil administrator and water conservation expert.

In Chinese mythology, he is known as the vanquisher of the River God and is compared to the Great Yu. Dujiangyan is still in use today and is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Remainder of article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Li_Bing

Source: Wikipedia

Dujiangyan (originally constructed in 256BC and is still in use today)

Du Jiang Yan Irrigation System

The Dujiangyan (Chinese: 都江堰; pinyin: Dūjiāngyàn) is an ancient irrigation system in Dujiangyan City, Sichuan, China.

Originally constructed around 256 BC by the State of Qin as an irrigation and flood control project, it is still in use today.

The system's infrastructure develops on the Min River (Minjiang), the longest tributary of the Yangtze. The area is in the west part of the Chengdu Plain, between the Sichuan basin and the Tibetan plateau.

Originally, the Min would rush down from the Min Mountains and slow down abruptly after reaching the Chengdu Plain, filling the watercourse with silt, thus making the nearby areas extremely prone to floods.

Li Bing, then governor of Shu for the state of Qin, and his son headed the construction of the Dujiangyan, which harnessed the river using a new method of channeling and dividing the water rather than simply damming it.

The water management scheme is still in use today to irrigate over 5,300 square kilometres (2,000 sq mi) of land in the region.

The Dujiangyan, the Zhengguo Canal in Shaanxi and the Lingqu Canal in Guangxi are collectively known as the "three great hydraulic engineering projects of the Qin."

Remainder of article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dujiangyan

Source: Wikipedia

Du Jiang Yan Irrigation System

The Dujiangyan (Chinese: 都江堰; pinyin: Dūjiāngyàn) is an ancient irrigation system in Dujiangyan City, Sichuan, China.

Originally constructed around 256 BC by the State of Qin as an irrigation and flood control project, it is still in use today.

The system's infrastructure develops on the Min River (Minjiang), the longest tributary of the Yangtze. The area is in the west part of the Chengdu Plain, between the Sichuan basin and the Tibetan plateau.

Originally, the Min would rush down from the Min Mountains and slow down abruptly after reaching the Chengdu Plain, filling the watercourse with silt, thus making the nearby areas extremely prone to floods.

Li Bing, then governor of Shu for the state of Qin, and his son headed the construction of the Dujiangyan, which harnessed the river using a new method of channeling and dividing the water rather than simply damming it.

The water management scheme is still in use today to irrigate over 5,300 square kilometres (2,000 sq mi) of land in the region.

The Dujiangyan, the Zhengguo Canal in Shaanxi and the Lingqu Canal in Guangxi are collectively known as the "three great hydraulic engineering projects of the Qin."

Remainder of article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dujiangyan

Source: Wikipedia

I will be beginning Chapter Two soon - Fish, Fowl and Pharaohs

Post your thoughts about the book.

Post your thoughts about the book.

Jim and Lacey - how are you doing on our leisurely read?

Post your thoughts as you read along - on your own schedule or with me - whatever you prefer - since this is free reading and post your thoughts as you come across anything interesting.

Also anyone else that wants to join in - by all means - it is never too late because it is a free read. Just let us know you are here.

Post your thoughts as you read along - on your own schedule or with me - whatever you prefer - since this is free reading and post your thoughts as you come across anything interesting.

Also anyone else that wants to join in - by all means - it is never too late because it is a free read. Just let us know you are here.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

✔Salt: A World History

✔Introduction: The Rock

✔Part One

A Discourse on Salt, Cadavers, and Pungent Sauces

✔Chapter One: A Mandate of Salt

✔Chapter Two: Fish, Fowl, and Pharoahs

✔Chapter Three: Saltmen Hard as Codfish

Chapter Four: Salt’s Salad Days

Chapter Five: Salting It Away in the Adriatic

Chapter Six: Two Ports and the Prosciutto in Between

Part Two

The Glow of Herring and the Scent of Conquest

Chapter Seven: Friday’s Salt

Chapter Eight: A Nordic Dream

Chapter Nine: A Well-Salted Hexagon

Chapter Ten: The Hapsburg Pickle

Chapter Eleven: The Leaving of Liverpool

Chapter Twelve: American Salt Wars

Chapter Thirteen: Salt and Independence

Chapter Fourteen: Liberté, Egalité, Tax Breaks

Chapter Fifteen: Preserving Independence

Chapter Sixteen: The War Between the Salts

Chapter Seventeen: Red Salt

Part Three

Sodium’s Perfect Marriage

Chapter Eighteen: The Odium of Sodium

Chapter Nineteen: The Mythology of Geology

Chapter Twenty: The Soil Never Sets On . . .

Chapter Twenty-One: Salt and the Great Soul

Chapter Twenty-Two: Not Looking Back

Chapter Twenty-Three: The Last Salt Days of Zigong

Chapter Twenty-Four: Ma, La, and Mao

Chapter Twenty-Five: More Salt than Fish

Chapter Twenty-Six: Big Salt, Little Salt

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Index

✔Salt: A World History

✔Introduction: The Rock

✔Part One

A Discourse on Salt, Cadavers, and Pungent Sauces

✔Chapter One: A Mandate of Salt

✔Chapter Two: Fish, Fowl, and Pharoahs

✔Chapter Three: Saltmen Hard as Codfish

Chapter Four: Salt’s Salad Days

Chapter Five: Salting It Away in the Adriatic

Chapter Six: Two Ports and the Prosciutto in Between

Part Two

The Glow of Herring and the Scent of Conquest

Chapter Seven: Friday’s Salt

Chapter Eight: A Nordic Dream

Chapter Nine: A Well-Salted Hexagon

Chapter Ten: The Hapsburg Pickle

Chapter Eleven: The Leaving of Liverpool

Chapter Twelve: American Salt Wars

Chapter Thirteen: Salt and Independence

Chapter Fourteen: Liberté, Egalité, Tax Breaks

Chapter Fifteen: Preserving Independence

Chapter Sixteen: The War Between the Salts

Chapter Seventeen: Red Salt

Part Three

Sodium’s Perfect Marriage

Chapter Eighteen: The Odium of Sodium

Chapter Nineteen: The Mythology of Geology

Chapter Twenty: The Soil Never Sets On . . .

Chapter Twenty-One: Salt and the Great Soul

Chapter Twenty-Two: Not Looking Back

Chapter Twenty-Three: The Last Salt Days of Zigong

Chapter Twenty-Four: Ma, La, and Mao

Chapter Twenty-Five: More Salt than Fish

Chapter Twenty-Six: Big Salt, Little Salt

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Index

I just picked up this book and am planning to start it.

I just picked up this book and am planning to start it. Bentley, thanks for the various posts; I am looking forward to reading them.

Books mentioned in this topic

Trading Tastes: Commodity and Cultural Exchange to 1750 (other topics)Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (other topics)

Myths and Legends of China (other topics)

Salt: A World History (other topics)

Authors mentioned in this topic

Erik Gilbert (other topics)Pu Songling (other topics)

E.T.C. Werner (other topics)

Mark Kurlansky (other topics)

What is the Book About:

In his fifth work of nonfiction, Mark Kurlansky turns his attention to a common household item with a long and intriguing history: salt. The only rock we eat, salt has shaped civilization from the very beginning, and its story is a glittering, often surprising part of the history of humankind. A substance so valuable it served as currency, salt has influenced the establishment of trade routes and cities, provoked and financed wars, secured empires, and inspired revolutions. Populated by colorful characters and filled with an unending series of fascinating details, Salt by Mark Kurlansky is a supremely entertaining, multi-layered masterpiece.

Mark Kurlansky is the author of many books including Cod, The Basque History of the World, 1968, and The Big Oyster. His newest book is Birdseye. (less)