Classics and the Western Canon discussion

Democracy in America

>

Week 12: DIA Vol2 Part 1 Ch. 17 - Vol 2 Part 2 Ch. 7

Chapter 20 ON CERTAIN TENDENCIES PECULIAR TO HISTORIANS IN DEMOCRATIC CENTURIES

Chapter 20 ON CERTAIN TENDENCIES PECULIAR TO HISTORIANS IN DEMOCRATIC CENTURIESReturning to his theme of Aristocratic individuals and democratic generalizations and applies it to historians viewpoints. For aristocratic historians, events are shaped by a small number of prominent individuals and specific causes. For Democartic historians, history is shaped by general causes and movements of a people, the downsides of which are these causes are sometimes lost in obscurity and deemed inevitable destinies to which they were powerless against.

Chapter 21 ON PARLIAMENTARY ELOQUENCE IN THE UNITED STATES

I took two main ideas out of this chapter.

1. Politicians will try to emulate the frequent and eloquent speeches of those thought to be a good leader in order to extend their political life. I conceptualized this as a transformation of the publish or perish rule for college professors into the speak well or go home rule for politicians.

2. Speeches tend towards the larger subjects or address the nation as a whole since there are no classes to address individually.

PART II Influence of Democracy on the Sentiments of the Americans

PART II Influence of Democracy on the Sentiments of the AmericansChapter 1 WHY DEMOCRATIC PEOPLES SHOW A MORE ARDENT AND ENDURING LOVE OF EQUALITY THAN OF LIBERTY

The goods that liberty yields reveal themselves only in the long run, and it is always easy to mistake their cause. . . To a certain number of citizens political liberty gives sublime pleasures from time to time. . . Men cannot enjoy political liberty without making sacrifices to obtain it, and it has never been won without great effort.I wonder if this is a difference between a self-evident truth of equality and an unalienable right to liberty?

The advantages of equality are felt immediately and can be seen daily to flow from their source. . .Equality provides a multitude of lesser pleasures to everyone every day. The charms of equality are constantly apparent and within reach of all.

. . .[People] want equality in liberty, and if they cannot have it, they want it still in slavery. They will suffer poverty, servitude, and barbarity, but they will not suffer aristocracy.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty. . .

Chapter 2 ON INDIVIDUALISM IN DEMOCRATIC COUNTRIES

Chapter 2 ON INDIVIDUALISM IN DEMOCRATIC COUNTRIESTocqueville takes a small chapter to define Individualism and distinguish it from egoism and establish it as a product of democracy. Is this a real problem, or is Tocqueville just making things up to explain why some citizens do not want to participate? Isn’t this balanced out by those who wish to distinguish themselves from the mass of equals in some way?

Chapter 3 HOW INDIVIDUALISM IS MORE PRONOUNCED AT THE END OF A DEMOCRATIC REVOLUTION THAN AT ANY OTHER TIME

Does Tocqueville make this statement based on his own personal situation?

Those citizens who were among the most prominent members of the ruined hierarchy cannot suddenly forget their former grandeur. They continue to think of themselves as strangers in the new society for quite some time.Tocqueville’s main point here seems to be that the Americans were better off being born into a democracy than attaining one through a democratic revolution because while equality in a democracy alone tends to dissolve the duties between them, a sudden equality from a democratic revolution additionally produces mistrust and hatred between the former classes.

Chapter 4 HOW AMERICANS COMBAT INDIVIDUALISM WITH FREE INSTITUTIONS

Individualism coincident with the equal conditions of a democracy compliment the barriers keeping citizens apart raised by despotism. One counter measure to Individualism is the institution of political liberty itself:

When citizens are forced to concern themselves with public affairs, they are inevitably drawn beyond the sphere of their individual interests, and from time to time their attention is diverted from themselves.Elections may produce times of heated debate among men, but the good of coming together outweighs the bad of any political ill feelings that may be stirred up.

Chapter 5 ON THE USE THAT AMERICANS MAKE OF ASSOCIATION IN CIVIL LIFEThe most fundamentally important “science” in democratic countries is the science of

civil

associations. These take the place of powerful private individuals in countries without equality of conditions and allow the relatively weak individuals of a democratic society to join together with other like-minded individuals to become a powerful force to be reckoned with. He concludes

Chapter 5 ON THE USE THAT AMERICANS MAKE OF ASSOCIATION IN CIVIL LIFEThe most fundamentally important “science” in democratic countries is the science of

civil

associations. These take the place of powerful private individuals in countries without equality of conditions and allow the relatively weak individuals of a democratic society to join together with other like-minded individuals to become a powerful force to be reckoned with. He concludesIf men are to remain civilized, or to become so, they must develop and perfect the art of associating to the same degree that equality of conditions increases among them.Chapter 6 ON THE RELATION BETWEEN ASSOCIATIONS AND NEWSPAPERS

It seems Tocqueville has expanded the critical need for newspapers in maintaining a democracy.

Hence the more equal men are, and the more individualism is to be feared, the more necessary newspapers become. To believe that their only purpose is to guarantee liberty would be to diminish their importance; they maintain civilization.Newspapers not only give voice to many and opposing opinions, they are in and of themselves associations by which people of common interests converse and counteract individualism.

Chapter 7 RELATIONS BETWEEN CIVIL ASSOCIATIONS AND POLITICAL ASSOCIATIONS

The fact that civil associations are rare in nations that ban political associations suggests there is some relationship between them.

Tocqueville seems to assume that everyone in a democracy participates in political associations. Political associations in turn educate and encourage the citizens to participate in civil associations.

The benefits of free political and civil associations outweigh the dangers.

The first time I heard in the United States that one hundred thousand men[*] had publicly pledged not to use strong liquor, the thing seemed to [902] me more amusingq than serious, and I did not at first see clearly why these citizens, who were so temperate, would not be content to drink water within their families.

The first time I heard in the United States that one hundred thousand men[*] had publicly pledged not to use strong liquor, the thing seemed to [902] me more amusingq than serious, and I did not at first see clearly why these citizens, who were so temperate, would not be content to drink water within their families.I ended by understanding that these hundred thousand Americans, frightened by the progress that drunkenness was making around them, had wanted to give their patronage to temperance. They had acted precisely like a great lord who dressed very plainly in order to inspire disdain for luxury among simple citizens. It may be believed that if these hundred thousand menr lived in France, each one of them would have individually addressed the government in order to beg it to oversee the taverns throughout the entire kingdom.

It seems that today US (not just US) became France. People who believes that abortion is wrong just do not do it but fight for others do not do it as well. The same for some many things. (I hope that this sentence do make grammatical sense)

Rafael wrote: "It seems that today US (not just US) became France. People who believes that abortion is wrong just do not do it but fight for others do not do it as well. The same for some many things. (I hope that this sentence do make grammatical sense)"

Rafael wrote: "It seems that today US (not just US) became France. People who believes that abortion is wrong just do not do it but fight for others do not do it as well. The same for some many things. (I hope that this sentence do make grammatical sense)"De Tocqueville said exactly the same that people who believed that drunkness is wrong are not content with not to drink 'but fight for others do not do it as well.' With abortion, afaik, people not sending individual petitions to the government but using the power of civil association (and more) to make everybody around them to fell in line. Government involved mostly by politicians wooing these voters. In this sense, the US is still not France. Though I may be totally wrong.

In regard to associations, Tocqueville seems to have only thought of the potential for civil unrest, conspiracy, and rebellion-making when he counted the dangers of associations. I wonder if Tocqueville saw the dangers of special interest lobby groups, or does even their potential benefits outweigh the dangers?

In regard to associations, Tocqueville seems to have only thought of the potential for civil unrest, conspiracy, and rebellion-making when he counted the dangers of associations. I wonder if Tocqueville saw the dangers of special interest lobby groups, or does even their potential benefits outweigh the dangers?

I had the same question when reading this chapter. He couldn't imagine association of farmers or steel manufacturers who promote high tariffs - that was my then answer, but now I think that he may think of this as good and democratic intervention.

I had the same question when reading this chapter. He couldn't imagine association of farmers or steel manufacturers who promote high tariffs - that was my then answer, but now I think that he may think of this as good and democratic intervention.And I think some of this kind existed in his time in America, so he should have overlooked them or treated them as benign.

David wrote: "In regard to associations, Tocqueville seems to have only thought of the potential for civil unrest, conspiracy, and rebellion-making when he counted the dangers of associations...."

David wrote: "In regard to associations, Tocqueville seems to have only thought of the potential for civil unrest, conspiracy, and rebellion-making when he counted the dangers of associations...."Isn't it typical T, to try to explore both sides of the coin, especially as he tries to "sell" democracy back to Europe? Not strictly DIA, but Cook in his Great Courses lectures makes a big deal of DIA's stress that democracy sort of begins or is self-taught by citizens participating in associations aligned with their self-interests -- and doing so at the local level where they can see and feel their impact. Also, that "association" doesn't imply agreement across all aspects of living, but shared interest enough in the purpose of the association to work together on its aims.

Although T (fore)saw the commercial aspects/focus of America, I don't think it was possible yet to forecast the vast power corporations would come to wield in society and in government -- which has brought along the special interest groups with access to deep pockets to support their efforts. E.g., perhaps tritely, the health insurance industry can provide lobbying resources and organization not readily available to its customers nor to the potential customers it may want to avoid. It is to that "corporationization" of democracy that I am seeing later students of democracy turn as a key issue -- although I am far from having a perspective with which I am comfortable. But the Citizens United decision seems to fit in there somewhere. And, again, I'm not suggesting we go to discussing the merits or demerits of current issues, only to think about key ways and areas in which the world (more specifically, democracy) has -- or has not -- morphed since T. observed it.

Lily wrote: "It is to that "corporationization" of democracy that I am seeing later students of democracy turn as a key issue..."

Lily wrote: "It is to that "corporationization" of democracy that I am seeing later students of democracy turn as a key issue..."Perhaps instead of Tocqueville's suggestion that rich individuals are the new aristocrats, just waiting for democracy to fail in order to take over, that corporations, or whole industries, will take this path to become the new aristocrats?

David wrote: "Chapter 17 ON SOME SOURCES OF POETRY IN DEMOCRATIC NATIONS

David wrote: "Chapter 17 ON SOME SOURCES OF POETRY IN DEMOCRATIC NATIONSThis chapter can be summed up in a few"

Here's my own summary of Chapter 17: Utter nonsense.

Gary wrote: "David wrote: "Chapter 17 ON SOME SOURCES OF POETRY IN DEMOCRATIC NATIONS

Gary wrote: "David wrote: "Chapter 17 ON SOME SOURCES OF POETRY IN DEMOCRATIC NATIONSThis chapter can be summed up in a few"

Here's my own summary of Chapter 17: Utter nonsense."

On one hand, what he says makes sense, but on the other hand I think he tried to hard to come up with something to say here that fit in with his other outcomes of equality. Again, his generalization is suspect by lack of evidence; I cannot think of any, let alone enough, examples that would make his model believable.

David wrote: "Again, his generalization is suspect by lack of evidence; "

David wrote: "Again, his generalization is suspect by lack of evidence; "I think it's fair to say that poetry did not have a solid foundation in 1830's America, but it's not fair to say were no poets, especially given his vague definition of poetry. Once again, he wants to frame societies in terms of aristocracy vs. democracy, and great achievements of individuals will always be for him the province of aristocracy.

What was he saying to his base? He wasn't running for office in the U.S., but he did seem to be trying to find the right niche for himself in France. He also had married a commoner, an English woman at that, apparently over the objections of his family. I do get a sense the second volume was not as well received as the first -- which did apparently gain widespread interest. I have a request out for the Norton Critical Edition. It usually includes some of the critical responses at the time. This is one of the few books I have read where I have so frequently wanted to put myself inside the mind of the writer as he chose what to commit to publication -- why there at all? What has gone into the wastebasket? Been burned? Been completely re-positioned. Is there simply because the writer's mind went there and no trusted reader chose to challenge it enough to other than leave it in place?

What was he saying to his base? He wasn't running for office in the U.S., but he did seem to be trying to find the right niche for himself in France. He also had married a commoner, an English woman at that, apparently over the objections of his family. I do get a sense the second volume was not as well received as the first -- which did apparently gain widespread interest. I have a request out for the Norton Critical Edition. It usually includes some of the critical responses at the time. This is one of the few books I have read where I have so frequently wanted to put myself inside the mind of the writer as he chose what to commit to publication -- why there at all? What has gone into the wastebasket? Been burned? Been completely re-positioned. Is there simply because the writer's mind went there and no trusted reader chose to challenge it enough to other than leave it in place?

David wrote: "Perhaps instead of Tocqueville's suggestion that rich individuals are the new aristocrats, just waiting for democracy to fail in order to take over, that corporations, or whole industries, will take this path to become the new aristocrats?..."

David wrote: "Perhaps instead of Tocqueville's suggestion that rich individuals are the new aristocrats, just waiting for democracy to fail in order to take over, that corporations, or whole industries, will take this path to become the new aristocrats?..."[g] Well, for analogies between entities that disparate... let (or don't let) the politicians pick their rhetoric.

Lily wrote: "What was he saying to his base? He wasn't running for office in the U.S., but he did seem to be trying to find the right niche for himself in France. He also had married a commoner, an English woman..."

Lily wrote: "What was he saying to his base? He wasn't running for office in the U.S., but he did seem to be trying to find the right niche for himself in France. He also had married a commoner, an English woman..."Interestingly, have never read about the critical response to his books, for me, the second volume and his analysis of moral aspects seem to be more valuable than the first with analysis of political institution, which is mostly outdated imho.

Alexey wrote: "Interestingly, have never read about the critical response to his books, for me, the second volume and his analysis of moral aspects seem to be more valuable than the first with analysis of political institution, which is mostly outdated imho...."

Alexey wrote: "Interestingly, have never read about the critical response to his books, for me, the second volume and his analysis of moral aspects seem to be more valuable than the first with analysis of political institution, which is mostly outdated imho...."That was my initial expectation, too, Alexey. As I get into reading the second volume, I'm beginning to wonder....

Roger wrote: "In AdT's time, for-profit limited-liability corporations hardly existed."

Roger wrote: "In AdT's time, for-profit limited-liability corporations hardly existed."True, I don't assume Tocqueville could have seen quite this far ahead. Even the great "robber barons", ("criminal aristocrats"), industrialists, or philanthropists, depending on circumstances and perspectives, were probably bigger than Tocqueville could have imagined. When they did arrive, the political scene was greatly influenced by them on behalf of their corporations. This 1901 US cartoon depicting John D. Rockefeller as a powerful monarch. clearly echos the fears of Tocqueville's warnings.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robber_...

As I understand, de Tocqueville thought association is the only effective counterweight to the powerful individuals and when everyone is trained to participate in associations, no individuals could be dangerously powerful.

As I understand, de Tocqueville thought association is the only effective counterweight to the powerful individuals and when everyone is trained to participate in associations, no individuals could be dangerously powerful.Here the next question if he overestimated the role of civil associations or the ability and the predisposition to form such associations.

David wrote: "Chapter 18 WHY AMERICAN WRITERS AND ORATORS ARE OFTEN BOMBASTIC

David wrote: "Chapter 18 WHY AMERICAN WRITERS AND ORATORS ARE OFTEN BOMBASTICTocqueville suggests that America writers resort to much pompous, bombastic, and high sounding speech in an effort to lift their work above the sea of equality of which they are apart."

I think AT perpetrates the very thing he rails against in this section. Ironic. Or maybe he feels entitled because he is not, himself, American.

Alexey wrote: "As I understand, de Tocqueville thought association is the only effective counterweight to the powerful individuals and when everyone is trained to participate in associations, no individuals could..."

Alexey wrote: "As I understand, de Tocqueville thought association is the only effective counterweight to the powerful individuals and when everyone is trained to participate in associations, no individuals could..."Good point, Alexey. I wonder if AT failed to anticipate the sheer growth in size of the US, as well as the communication technology advancements that have made it ubiquitous for nearly every person with an opinion about anything to participate in not only an association, but a non-local (i.e. national) one at that.

And although no individuals are dangerously powerful, the relative influence of these associations give them collectively, and institutional power.

When folks talks about institutional injustices, this is why.

Kyle wrote: "I think AT perpetrates the very thing he rails against in this section. Ironic. Or maybe he feels entitled because he is not, himself, American."

Kyle wrote: "I think AT perpetrates the very thing he rails against in this section. Ironic. Or maybe he feels entitled because he is not, himself, American."I wonder if the first translator at the time, Reeve, played any part in what you are percieving?

Kyle wrote: "And although no individuals are dangerously powerful, the relative influence of these associations give them collectively, and institutional power.

Kyle wrote: "And although no individuals are dangerously powerful, the relative influence of these associations give them collectively, and institutional power.When folks talks about institutional injustices, this is why."

It is certainly a digression, but I cannot understand why we talk about institutional injustices when everyone, who really cares about something, can find people alike and form an association easier than anytime before. If people care about something, they can obtain institutional power despite their economic and social status. At least in this regard, institutional injustice sounds like nonsensical conception.

David wrote: ""people treat plays as a brief time outs from life and expect them to be more of an emotional “show” than an uplifting or profound presentation of literature or intellect." This of course explains cat videos."

David wrote: ""people treat plays as a brief time outs from life and expect them to be more of an emotional “show” than an uplifting or profound presentation of literature or intellect." This of course explains cat videos."You are a wise man, David.

David wrote: "Lily wrote: "It is to that "corporationization" of democracy that I am seeing later students of democracy turn as a key issue ..."

David wrote: "Lily wrote: "It is to that "corporationization" of democracy that I am seeing later students of democracy turn as a key issue ..."Corporations are no where mentioned in the Constitution, yet they have lately become important players in American democracy. The "corporatization" of democracy began when businesses claimed equal protection under the law under the 14th Amendment (1868), which I here quote in part: "No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law ... " Corporations claimed to be persons under the Amendment and the courts upheld that claim, although the rights granted then were economic rather than political. Only recently did that change. In 1978 a divided Supreme Court, reversing nearly 200 years of precedent, gave corporations the right to contribute to political campaigns. In 2010 an again divided Court gave corporations the same political rights as persons, including the right to advocate politically and use their financial resources to influence campaigns and policy. A presidential candidate in 2008 was quoted as saying that "corporations are people." There was blowback to his frank statement, but it was true nonetheless.

These very recent changes in the political rights of corporations have had profound effects on American democracy. Money now plays an even larger part in politics that ever before, so much so that some have claimed that corporations "own" the government. I don't think that's true yet, even though it is certainly true that many elected officials are beholden to corporations. It is also certain that this is not the democracy envisioned by the Founders, nor is it the democracy described by T.

For more about corporations as legal persons, see the following NPR piece entitled When Did Companies Become People? Excavating The Legal Evolution (July 2014) https://www.npr.org/2014/07/28/335288...

Alexey wrote: " ... for me, the second volume and his analysis of moral aspects seem to be more valuable than the first ..."

Alexey wrote: " ... for me, the second volume and his analysis of moral aspects seem to be more valuable than the first ..."Lily wrote: '"That was my initial expectation, too, Alexey. As I get into reading the second volume, I'm beginning to wonder.... "

Both volumes are rife with generalizations, but Volume 1 was based, at least in part, on fieldwork. Volume 2 seems to me to have been conceived in a wood-paneled study. Reading some of the chapters in Volume 2 put me in mind of deductive reasoning run amuck. i.e. from certain principles, certain surmises follow, at least in the mind of the surmiser. To me these sort of unsupported conjectures are suspect, and we readers need to consider them critically.

Gary wrote: "Alexey wrote: " ... for me, the second volume and his analysis of moral aspects seem to be more valuable than the first ..."

Gary wrote: "Alexey wrote: " ... for me, the second volume and his analysis of moral aspects seem to be more valuable than the first ..."Lily wrote: '"That was my initial expectation, too, Alexey. As I get int..."

Could not agree more, I suppose that we need to consider critical all hypothesis whatever they are based on. However, I am a Popperian in this question - the first volume may rest on empirical data but failed to predict future change at all, the second volume may rest solely on his speculation but many of his generalisations turned out to be true, at least for Russia.

Alexey wrote: "...I am a Popperian in this question...."

Alexey wrote: "...I am a Popperian in this question...."Alexey -- I don't know Popper well enough to grasp your allusion and am lazy enough this morning that I am going to ask you to explain rather than go do the Internet work I would need to understand....

I would grant T that the first section does at least sort of predict the Civil War or at least some significant disruptive social response to slavery in the U.S.

Kyle wrote: "When folks talks about institutional injustices, this is why...."

Kyle wrote: "When folks talks about institutional injustices, this is why...."I didn't follow your logic, Kyle. (When I searched for "institutional injustice examples," the results didn't clarify for me what we might be discussing here!?! Police brutality? Policies and programs that treat different groups "not equally"/"unfairly", e.g., don't maintain civic facilities equitably in different economic areas? ....?? )

Alexey wrote: "I cannot understand why we talk about institutional injustices when everyone, who really cares about something, can find people alike and form an association easier than anytime before. If people care about something, they can obtain institutional power"

Alexey wrote: "I cannot understand why we talk about institutional injustices when everyone, who really cares about something, can find people alike and form an association easier than anytime before. If people care about something, they can obtain institutional power"Tocqueville might suggest individualism. I would add also a bit of Cephalus from the Republic to that had other duties to attend to and is more inclined to pass the fight on to the younger generation, others.

Republic I.331d. . .I fear, said Cephalus, that I must go now, for I have to look after the sacrifices, and I hand over the argument to Polemarchus and the company. Is not Polemarchus your heir? I said. To be sure, he answered, and went away laughing to the sacrifices.

Lily wrote: "I would grant T that the first section does at least sort of predict the Civil War or at least some significant disruptive social response to slavery in the U.S."

Lily wrote: "I would grant T that the first section does at least sort of predict the Civil War or at least some significant disruptive social response to slavery in the U.S."This is one of examples when, I thought, he missed the point, but perhaps I was too harsh on him, forecasting of political event for decades cannot be precise, and he definitely saw the problem.

As for Popper, he stated in his Open society, that way we come to hypothesis is not important, but hypothesis should be falsifiable and open to testing against evidences. Sorry can not find exact citation.

The concept was introduced by the philosopher of science Karl Popper. He saw falsifiability as the logical part and the cornerstone of his scientific epistemology, which sets the limits of scientific inquiry. He proposed that statements and theories that are not falsifiable are unscientific. Declaring an unfalsifiable theory to be scientific would then be pseudoscience.

The concept was introduced by the philosopher of science Karl Popper. He saw falsifiability as the logical part and the cornerstone of his scientific epistemology, which sets the limits of scientific inquiry. He proposed that statements and theories that are not falsifiable are unscientific. Declaring an unfalsifiable theory to be scientific would then be pseudoscience.I shall require that [the] logical form [of the theory] shall be such that it can be singled out, by means of empirical tests, in a negative sense: it must be possible for an empirical scientific system to be refuted by experience.

Popper, Karl (1959). The Logic of Scientific Discovery (2002 pbk; 2005 ebook ed.). Pg. 19. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-27844-7.

@29Alexey wrote: "the second volume may rest solely on his speculation but many of his generalisations turned out to be true, at least for Russia...."

@29Alexey wrote: "the second volume may rest solely on his speculation but many of his generalisations turned out to be true, at least for Russia...."Which ones particularly strike you, i.e., are driving your comment here, Alexey?

Alexey wrote: "As for Popper, he stated in his Open society, that way we come to hypothesis is not important, but hypothesis should be falsifiable and open to testing against evidences...."

Alexey wrote: "As for Popper, he stated in his Open society, that way we come to hypothesis is not important, but hypothesis should be falsifiable and open to testing against evidences...."Had lunch yesterday with a friend, retired from scientific research in a major multinational, and we chewed the fat about Popper's position as brought into our discussion here. While his position on evidence that David quotes seemed obvious, at least across "normal science," i.e., within a paradigm (we each happened to be more aware of Kuhn's work than of Popper's), we talked a bit about how, in the "real" world, the source of hypotheses ('way we come to') often very much determines what research ("science") gets done.

Lily wrote: "Alexey wrote: "As for Popper, he stated in his Open society, that way we come to hypothesis is not important, but hypothesis should be falsifiable and open to testing against evidences...."

Lily wrote: "Alexey wrote: "As for Popper, he stated in his Open society, that way we come to hypothesis is not important, but hypothesis should be falsifiable and open to testing against evidences...."Had lu..."

I am in the opposite situation I knew much better Popper's than Kuhn, and I agree with you and your friend that the source of hypotheses determines the result (at least partially), as I understand Popper's view the hypothesis cannot be judged by its source but rather by its results (by 'fruits').

Alexey wrote: "...I understand Popper's view the hypothesis cannot be judged by its source but rather by its results (by 'fruits')..."

Alexey wrote: "...I understand Popper's view the hypothesis cannot be judged by its source but rather by its results (by 'fruits')..."Alexey, I think what we were putting on the table was, although the results indeed are what is important, often only hypotheses from politically more powerful sources even get a chance to be tested and carried through to results.

(view spoiler)

@29 Alexey wrote: "...the second volume may rest solely on his speculation but many of his generalisations turned out to be true, at least for Russia.

But the above is the one of your statements that really fascinated me, Alexey. Can you share examples? (As with Popper, I didn't/don't know enough to go there on my own.)

Gary wrote: "David wrote: "Chapter 17 ON SOME SOURCES OF POETRY IN DEMOCRATIC NATIONS

Gary wrote: "David wrote: "Chapter 17 ON SOME SOURCES OF POETRY IN DEMOCRATIC NATIONSThis chapter can be summed up in a few"

Here's my own summary of Chapter 17: Utter nonsense."

Does Whitman's scope agree or disagree with Tocqueville's ideas of poetic scope?

TO FOREIGN LANDS.

I heard that you ask’d for something to prove this puzzle the New World, And to define America, her athletic Democracy, Therefore I send you my poems that you behold in them what you wanted.

Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass (Modern Library Classics) . Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

A little more on Whiteman fitting in to Tocqueville's prediction

A little more on Whiteman fitting in to Tocqueville's predictionWalt Whitman, Poet of Democracy

By Jorge Luis Borges

https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/wa...

. . .Now then, there was always a hero in epic poetry; Vergil said, “I sing of arms, deeds, and the man”; that is to say, a man is chosen and exalted. Heroes like Achilles, Ulysses, Roland, and El Cid are some examples.

Everyone was the hero of Whitman’s poem since he wrote it in relation to democracy, in relation to an ideal of equality among all men on earth. . .

David wrote: "Does Whitman's scope agree or disagree with Tocqueville's ideas of poetic scope?..."

David wrote: "Does Whitman's scope agree or disagree with Tocqueville's ideas of poetic scope?..."I submit for your consideration other poets, contemporaries of Whitman d. 1892, whose voices refute T's assertions about poetry in America.

William Cullen Bryant d. 1878

Emily Dickinson d.1886

Edgar Allen Poe d. 1849

Ralph Waldo Emerson d.1882

Henry Wordsworth Longfellow d.1882

Henry David Thoreau d. 1862

Gary wrote: "I submit for your consideration other poets, contemporaries of Whitman d. 1892, whose works refute T's assertions about poetry in America."

Gary wrote: "I submit for your consideration other poets, contemporaries of Whitman d. 1892, whose works refute T's assertions about poetry in America."Common themes of those authors and poets seem to support Tocqueville's assertions rather than refute them.

Emily Dickenson's Themes

Death

Truth and its tenuous nature

Fame and Success

Grief

Faith

Longfellow Themes seem to come the closest to refuting T, but, he was also one of the first and the most "European-like"?

MytholAmericaogizing

The power of creative writing on Historical Narrative

Heroism is a Choice Made During Strife

Sentimentality

Emerson

Trancendentalism

Individualism (self-reliance)

Abolitionism

The Natural World, a kind of pantheism that AdT predicted and warned about.

Spiritualism

Heroism is a choice made during strife

Sentimentality

Freedom through poetry

Intensity of emotion

Thoreau's themes

The slumbering of mankind and need for spiritual awakening

Man as part of nature

the destructive force of industrial progress

The animal/spiritual dialectical struggle within man

Nature as reflection of human emotions

Spiritual rebirth reflected in nature and the seasons

Discovery of the essential through a life of simplicity

Exploring the interior of oneself

The right to resistance

Individual conscience and morality

Limited government

David wrote: "Gary wrote: "I submit for your consideration other poets, contemporaries of Whitman d. 1892, whose works refute T's assertions about poetry in America."

David wrote: "Gary wrote: "I submit for your consideration other poets, contemporaries of Whitman d. 1892, whose works refute T's assertions about poetry in America."Common themes of those authors and poets se..."

While I'm not particularly a reader of poetry, let alone a student, my sense is that Emily Dickinson is usually accorded a little broader range of themes than just the ones listed above. Albeit a biased source, the site for her museum puts it this way:

"Like most writers, Emily Dickinson wrote about what she knew and about what intrigued her. A keen observer, she used images from nature, religion, law, music, commerce, medicine, fashion, and domestic activities to probe universal themes: the wonders of nature, the identity of the self, death and immortality, and love."

The one that seems particularly American/democratic on that list is "identity of the self," certainly an issue as the individual emerged in importance from the family and community (as well as social strata?) in which embedded. I haven't looked to consider whether the difference matters in comparison with what T tries to promote as a standard or goal for poetic excellence. These do seem to be themes about universals rather than odes featuring specific individuals. I wish T had given us some of his European examples -- or maybe I need to go re-read him...

It is my perception that dear Longfellow has not weathered well in status among the pantheon of (American) poets, although I certainly enjoyed him and his tales in my own grade school days, mostly seventh and eighth grades. I still periodically pull from my shelves and enjoy an edition of Hiawatha illustrated by Frederic Remington. But I consider it a walk into a highly romanticized story with questionable links to actual history. (My memory tonight is not recalling the success of Longfellow's role in attempting to document Indian language -- a bit controversial, at least by the standards of those who followed him?)

Gary wrote: "David wrote: "Does Whitman's scope agree or disagree with Tocqueville's ideas of poetic scope?..."

Gary wrote: "David wrote: "Does Whitman's scope agree or disagree with Tocqueville's ideas of poetic scope?..."I submit for your consideration other poets, contemporaries of Whitman d. 1892, whose voices refu..."

Except for a few works by Bryant and Poe, these writers had not published when AdT made his visit. Dickenson was a small child. It looks like AdT accurately reported what he saw, but America did catch up well enough in literary output.

Lily wrote: "But the above is the one of your statements that really fascinated me, Alexey. Can you share examples? (As with Popper, I didn't/don't know enough to go there on my own.) .."

Lily wrote: "But the above is the one of your statements that really fascinated me, Alexey. Can you share examples? (As with Popper, I didn't/don't know enough to go there on my own.) .."I am sorry for long delay in answer, was on the phone, and had some problem with orientation in both my notes and the book. Mostly examples I thought of belong to part 4, but one example belong just to next thread and stroke me when I read the book

(view spoiler)

Roger wrote: "Except for a few works by Bryant and Poe, these writers had not published when AdT made his visit. Dickenson was a small child. It looks like AdT accurately reported what he saw, but America did catch up well enough..."

Roger wrote: "Except for a few works by Bryant and Poe, these writers had not published when AdT made his visit. Dickenson was a small child. It looks like AdT accurately reported what he saw, but America did catch up well enough..."By my read Volume 2 expands on Volume 1 by making predictions for democratic centuries. Indeed, in the chapter on poetry, T explicitly says that he is anticipating what's to come. "One may anticipate as well that poets who live in democratic ages will depict passions and ideals rather than persons and actions." In that light, I believe that referring to poets that came shortly after his time in America is appropriate.

Gary wrote: "I submit for your consideration other poets, contemporaries of Whitman d. 1892, whose voices refute T's assertions about poetry in America."

Gary wrote: "I submit for your consideration other poets, contemporaries of Whitman d. 1892, whose voices refute T's assertions about poetry in America."David wrote: "Common themes of those authors and poets seem to support Tocqueville's assertions rather than refute them.."

I expect we’d agree that poetry can be complex and that different readers may takeaway different interpretations of the same poem. By no means do I want to disparage others’ readings; what I do want to do is explain why I called T’s chapter titled Some Sources of Poetry in Democratic Nations “utter nonsense.”

T predicted certain things about poetry in America that I thought were and are off base. He predicted that Americans and American poets would

- not be interested in ideals, but only in the practical and real

- not be interested in the past

- not be interested in persons as subjects of poetry

- not be interested in nature poetry

- be mainly interested in human destinies as the chief, if not the sole, object of poetry.

Following find some of the statements by T that ticked me off. T was not wrong in everything he said about aristocratic and democratic poetry, but about these he was dead wrong.

“… the taste for the ideal, and the pleasure people take in seeing it depicted, and never as intense or widespread in a democratic people as they are in an aristocracy. ”

“ … imagination, though not suffocated, is almost exclusively preoccupied with conceiving the useful and representing the real.”

“Having deprived poetry of the past, equality then strips away part of the present.”

“ …poets who live in democratic centuries can never take a particular individual as the subject of their work … “

“Democratic peoples may well amuse themselves briefly by contemplating nature, but the only thing that really inspires them is the sight of themselves.”

“The wonders of inanimate nature leave them cold, and it is hardly an exaggeration to say that they do not see the admirable forests that surround them until the trees fall to their axes.”

“ … poets who live in democratic ages will depict passions and ideas rather than persons and actions.”

“Human destinies — man, taken apart from time and country and set before nature and God, with his passions, doubts, unprecedented good fortune and incomprehensible misery — will become the chief, if not the sole, subject of poetry.“

“ … equality does not destroy all the subjects of poetry; it reduces their number but enlarges their scope.”

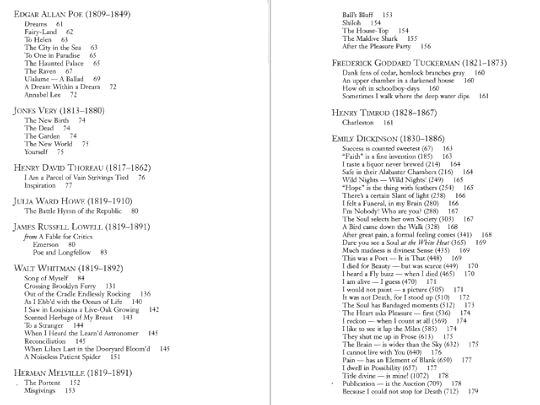

For the curious, here are some pre (or contemporary) DIA American poems/ poets:

For the curious, here are some pre (or contemporary) DIA American poems/ poets:

My apologies for blurry image hosting; you can click on the picture to see better.

Surely a lot of these weren't writing yet or hadn't been published at the time T was visiting...I didn't think Dickenson had anything published until after her death.

Surely a lot of these weren't writing yet or hadn't been published at the time T was visiting...I didn't think Dickenson had anything published until after her death. Longfellow, Whittier, and Holmes maybe? A few others?

I can't really blame T for the opinions he had of American literature at the time, but I don't think he made any allowances for maturity. Here's a generality worthy of T himself: pre-industrial revolution, pre-Civil War, the attitude was democratic as T saw it. The industrial revolution and the years it took to get on it's feet after colonial times eventually morphed into a moneyed aristocratic culture and mindset, while retaining democratic forms.

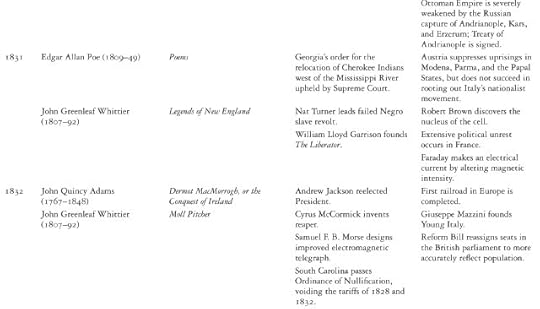

T visited America 1831 - 1832, during that time alone, these were being published

T visited America 1831 - 1832, during that time alone, these were being published

(1831 - 32)

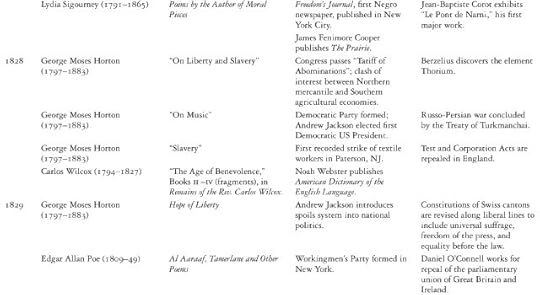

A couple more just before:

(1828-29)

More poems / criticism about poems being published 1800 - 1931 (year AdT visited America)

Using spoiler tags to avoid making the scroll too long for mobile users

(view spoiler)

Point is, America really wasn’t such a poetic wasteland.

This chapter can be summed up in a few

Chapter 18 WHY AMERICAN WRITERS AND ORATORS ARE OFTEN BOMBASTIC

Tocqueville suggests that America writers resort to much pompous, bombastic, and high sounding speech in an effort to lift their work above the sea of equality of which they are apart.

Chapter 19 SOME OBSERVATIONS ON THE THEATER OF DEMOCRATIC PEOPLES

America is still left with the influence of the Puritans who:Apparently Americans were too busy working during the week and going to church on Sunday to attend plays. However, Tocqueville says plays are becoming more popular but people treat plays as a brief time outs from life and expect them to be more of an emotional “show” than an uplifting or profound presentation of literature or intellect. This of course explains cat videos.