The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Barnaby Rudge

>

BR Chapters 66-70

Chapter 67

As the next day dawns, the city of London wears “a strange aspect indeed.” The riots and the night of destruction have stunned London’s public. Soldiers are in the streets and the citizens of London are milling about, scores of whom are displaced from their homes, and an unease hangs like a miasma over the entire metropolis. We read that some of the recently freed Newgate prisoners wanted to return to the prison rather than face another night free in the dangerous streets. Meanwhile, the mob have proclaimed their next targets of opportunity. There was even a rumour that the mob intended to “throw the gates of Bedlam open, and let all the madmen loose.” Soon the “dreaded night drew near again.” This chapter has a very intense tone of distrust and fear. As readers, we know that more is to come; what it will be and how destructive it will become we have yet to find out.

At seven o’clock the Privy Council issued a proclamation to employ the military and each soldier is issued thirty-six rounds of powder and ball. This suggests that the government is no longer willing to accept what has occurred. Individual homes take up arms and the streets are cleared. With all these actions and precautions the mob once again swells and takes to the streets. As night settles in the rioters “rose like a great sea” and soon fires were set and the chaos was unleashed once again. Dickens tells us that “[t]hat the streets were now a dreadful spectacle.”

Thoughts

To what extent do you think Dickens has captured the mood of London, the people, and the mob in the opening paragraphs of this chapter?

In terms of comparison, A Tale of Two Cities also has a mob scene, but that book is yet to come. Can you name any other novel that effectively portrays a mob scene? Did you find this other book more/less effective in capturing the mood of a mob?

We read that one of the preeminent leaders of the mob was Hugh and the target of his group was the vintner’s house where Haredale, Grueby, and the vintner have taken refuge. The fact that Grueby is now an employee of the vintner seems a bit of a stretch and a coincidence, but I am certain Dickens has something more up his literary sleeve for Grueby. In this chapter Dickens again portrays Hugh as a man driven who had “extreme audacity, and ... conviction”.

In order to get a better view of the riot Haredale and Langdale ascend to the roof of the house to watch the riot unfold. This vantage point also helps the reader become a witness to the evening’s unfolding events. Upon seeing the scene below the vintner soon understands his home will be destroyed and realizes that the only course of action is to flee across the roofs of adjoining buildings. Looking up to the roof Hugh recognizes Haredale, and Haredale urges the vintner to save himself. They flee to the basement and grope their way towards safety. And then the moment we have been waiting for ... in the basement, coming to rescue them, is none other than Joe Willet and Edward Chester. And how, do you say, could this happen? Well, remember when Joe Willet came to to pay the bill of the Maypole so many chapters ago? It was that vintner. And so the Dickens magic of coincidence works its way again. Joe tells us that it was Edward Chester who struck Hugh from his horse right in front of the mob. John Grueby gathers up everyone and helps them to enter by a back door, and then goes in search of the soldiers. Langdale leads the group to a safe exit from the house and into the night.

Thoughts

In this chapter Haredale and Langdale barely escape from the mob, and more specially from Hugh who was intent on harming them. We also have the return of Joe Willet and Edward who are rapidly assuming the role of saviours, if not heroes. Hugh is portrayed in this chapter as a leader of the mob and a man intent on creating as much havoc and destruction as possible.

Did you find that Dickens, in any way, portrayed Hugh in heroic terms is this chapter?

In what ways did Edward and Joe act as heroes in this chapter?

From earlier chapters we know that Edward Chester was in love with Emma Haredale, but they were halted in their affection for each other by their elders who held a grudge against each other. How can we see this chapter as a turning point in their relationship?

With Joe Willet back in the plot would you care to project what will happen next to him?

To what extent could this chapter a turning point in the story? Why?

What is the significance of the fact that the army was issued powder and shot?

As the next day dawns, the city of London wears “a strange aspect indeed.” The riots and the night of destruction have stunned London’s public. Soldiers are in the streets and the citizens of London are milling about, scores of whom are displaced from their homes, and an unease hangs like a miasma over the entire metropolis. We read that some of the recently freed Newgate prisoners wanted to return to the prison rather than face another night free in the dangerous streets. Meanwhile, the mob have proclaimed their next targets of opportunity. There was even a rumour that the mob intended to “throw the gates of Bedlam open, and let all the madmen loose.” Soon the “dreaded night drew near again.” This chapter has a very intense tone of distrust and fear. As readers, we know that more is to come; what it will be and how destructive it will become we have yet to find out.

At seven o’clock the Privy Council issued a proclamation to employ the military and each soldier is issued thirty-six rounds of powder and ball. This suggests that the government is no longer willing to accept what has occurred. Individual homes take up arms and the streets are cleared. With all these actions and precautions the mob once again swells and takes to the streets. As night settles in the rioters “rose like a great sea” and soon fires were set and the chaos was unleashed once again. Dickens tells us that “[t]hat the streets were now a dreadful spectacle.”

Thoughts

To what extent do you think Dickens has captured the mood of London, the people, and the mob in the opening paragraphs of this chapter?

In terms of comparison, A Tale of Two Cities also has a mob scene, but that book is yet to come. Can you name any other novel that effectively portrays a mob scene? Did you find this other book more/less effective in capturing the mood of a mob?

We read that one of the preeminent leaders of the mob was Hugh and the target of his group was the vintner’s house where Haredale, Grueby, and the vintner have taken refuge. The fact that Grueby is now an employee of the vintner seems a bit of a stretch and a coincidence, but I am certain Dickens has something more up his literary sleeve for Grueby. In this chapter Dickens again portrays Hugh as a man driven who had “extreme audacity, and ... conviction”.

In order to get a better view of the riot Haredale and Langdale ascend to the roof of the house to watch the riot unfold. This vantage point also helps the reader become a witness to the evening’s unfolding events. Upon seeing the scene below the vintner soon understands his home will be destroyed and realizes that the only course of action is to flee across the roofs of adjoining buildings. Looking up to the roof Hugh recognizes Haredale, and Haredale urges the vintner to save himself. They flee to the basement and grope their way towards safety. And then the moment we have been waiting for ... in the basement, coming to rescue them, is none other than Joe Willet and Edward Chester. And how, do you say, could this happen? Well, remember when Joe Willet came to to pay the bill of the Maypole so many chapters ago? It was that vintner. And so the Dickens magic of coincidence works its way again. Joe tells us that it was Edward Chester who struck Hugh from his horse right in front of the mob. John Grueby gathers up everyone and helps them to enter by a back door, and then goes in search of the soldiers. Langdale leads the group to a safe exit from the house and into the night.

Thoughts

In this chapter Haredale and Langdale barely escape from the mob, and more specially from Hugh who was intent on harming them. We also have the return of Joe Willet and Edward who are rapidly assuming the role of saviours, if not heroes. Hugh is portrayed in this chapter as a leader of the mob and a man intent on creating as much havoc and destruction as possible.

Did you find that Dickens, in any way, portrayed Hugh in heroic terms is this chapter?

In what ways did Edward and Joe act as heroes in this chapter?

From earlier chapters we know that Edward Chester was in love with Emma Haredale, but they were halted in their affection for each other by their elders who held a grudge against each other. How can we see this chapter as a turning point in their relationship?

With Joe Willet back in the plot would you care to project what will happen next to him?

To what extent could this chapter a turning point in the story? Why?

What is the significance of the fact that the army was issued powder and shot?

Chapter 68

Freed from Newgate prison, Barnaby and his father find themselves in the streets with files and tools to release themselves from their fetters. Even though Barnaby is reunited with his father, we are told that Barnaby looked upon Hugh as “his preserver and truest friend.” Barnaby and his father flee the area and end up resting in a poor shed. Barnaby assumes the role of protector and caregiver to his father and guards, kisses, and soothes him in his sleep. We at last get a firm indication that Barnaby is thinking about his mother as he wonders when “she will come to join them.” Barnaby listens for her footsteps and watches for her shadow. Barnaby is sent by his father to London in order to find the blind man and bring him back to his father. After getting the instructions of how to find him a few times from his father, Barnaby sets off to London. When he arrives in the city Barnaby finds himself changed in his attitude towards the riot. Dickens questions whether it was the time Barnaby had just passed in the solitude of the country, the absence of his rioter companions, or perhaps that he had no violent agenda. Whatever it was, Barnaby now thinks that London “seemed populated by a legion of devils.” Looking around, Barnaby sees the “cruel burning and destroying, the dreadful cries and stunning noises” and questions whether “they were the good lord’s noble cause!” Barnaby finds the blind man’s house closed and locked up.

Thoughts

Barnaby’s father is a double murderer and his friend Hugh is a central character in the mob violence surrounding the Gordon Riots. Which of these two characters do you think has caused the most harm to Barnaby? Is any sympathy created for either of these two men in this chapter?

Barnaby performs a nurturing role in the care of his father. What do you think Dickens’s purpose was in creating this scene?

We have had virtually no mention of Barnaby’s mother in several chapters. What is Dickens’s purpose in mentioning her in this chapter?

When Barnaby does not find the blind man he heads into a place in the city where he heard a great crowd was located in the hopes of finding Hugh and persuading him to avoid danger and return to the country with him. Barnaby soon finds both Hugh and the rioters but now the sights, sounds, and roars of the mob sicken him. As Barnaby approaches Hugh on horseback he witnesses Hugh as he fell headlong from his horse. Hugh is incensed and demands who unhorsed him, it Barnaby does not know. Barnaby drags Hugh from the scene of the riot which is occurring at the vintner’s house. This is a very interesting scene as Dickens has first shown us what the mob was like from within the vintner’s house in the previous chapter. As readers we are aware who has unhorsed Hugh but neither Hugh nor Barnaby nor anyone else in the mob does.

Hugh then wants to know where Dennis is. Apparently he has melted away from the mob earlier in the day and disappeared. Hugh makes in back to his horse, Barnaby mounts the horse as well, and together they ride away from the vintner’s house, but not before one last look where what the see is “one large, flowing blaze.” In a scene that predates the riots in A Tale of Two Cities we read that the vintner’s wine ran through the streets where dozens of men, women, and children “drank until they died.” The liquor had killed them. And so, on the last night of the riots, the destruction of London by the mob boomerangs and destroys many of the rioters themselves. Poetic justice? Barnaby reaches the country, helps Hugh off the horse, and sets the horse free. Then, he leads Hugh slowly forward.

Thoughts

This chapter brings the riots to a close, it presents the readers with much to think about. Did you enjoy the parallel sequencing of time in this chapter and the previous one where we get two perspectives on the attack on the vintner’s home? As readers we know that the vintner and Haredale are within the house as Hugh is attacking the house from the outside. We know who knocked Hugh off his horse.

Where, oh where, is Dennis? A mob attack on a wine storage establishment should have been of great interest to him.

We see Barnaby trying to help Hugh escape from the mob. What can account for Barnaby’s seemingly lack of interest in any more looting?

Freed from Newgate prison, Barnaby and his father find themselves in the streets with files and tools to release themselves from their fetters. Even though Barnaby is reunited with his father, we are told that Barnaby looked upon Hugh as “his preserver and truest friend.” Barnaby and his father flee the area and end up resting in a poor shed. Barnaby assumes the role of protector and caregiver to his father and guards, kisses, and soothes him in his sleep. We at last get a firm indication that Barnaby is thinking about his mother as he wonders when “she will come to join them.” Barnaby listens for her footsteps and watches for her shadow. Barnaby is sent by his father to London in order to find the blind man and bring him back to his father. After getting the instructions of how to find him a few times from his father, Barnaby sets off to London. When he arrives in the city Barnaby finds himself changed in his attitude towards the riot. Dickens questions whether it was the time Barnaby had just passed in the solitude of the country, the absence of his rioter companions, or perhaps that he had no violent agenda. Whatever it was, Barnaby now thinks that London “seemed populated by a legion of devils.” Looking around, Barnaby sees the “cruel burning and destroying, the dreadful cries and stunning noises” and questions whether “they were the good lord’s noble cause!” Barnaby finds the blind man’s house closed and locked up.

Thoughts

Barnaby’s father is a double murderer and his friend Hugh is a central character in the mob violence surrounding the Gordon Riots. Which of these two characters do you think has caused the most harm to Barnaby? Is any sympathy created for either of these two men in this chapter?

Barnaby performs a nurturing role in the care of his father. What do you think Dickens’s purpose was in creating this scene?

We have had virtually no mention of Barnaby’s mother in several chapters. What is Dickens’s purpose in mentioning her in this chapter?

When Barnaby does not find the blind man he heads into a place in the city where he heard a great crowd was located in the hopes of finding Hugh and persuading him to avoid danger and return to the country with him. Barnaby soon finds both Hugh and the rioters but now the sights, sounds, and roars of the mob sicken him. As Barnaby approaches Hugh on horseback he witnesses Hugh as he fell headlong from his horse. Hugh is incensed and demands who unhorsed him, it Barnaby does not know. Barnaby drags Hugh from the scene of the riot which is occurring at the vintner’s house. This is a very interesting scene as Dickens has first shown us what the mob was like from within the vintner’s house in the previous chapter. As readers we are aware who has unhorsed Hugh but neither Hugh nor Barnaby nor anyone else in the mob does.

Hugh then wants to know where Dennis is. Apparently he has melted away from the mob earlier in the day and disappeared. Hugh makes in back to his horse, Barnaby mounts the horse as well, and together they ride away from the vintner’s house, but not before one last look where what the see is “one large, flowing blaze.” In a scene that predates the riots in A Tale of Two Cities we read that the vintner’s wine ran through the streets where dozens of men, women, and children “drank until they died.” The liquor had killed them. And so, on the last night of the riots, the destruction of London by the mob boomerangs and destroys many of the rioters themselves. Poetic justice? Barnaby reaches the country, helps Hugh off the horse, and sets the horse free. Then, he leads Hugh slowly forward.

Thoughts

This chapter brings the riots to a close, it presents the readers with much to think about. Did you enjoy the parallel sequencing of time in this chapter and the previous one where we get two perspectives on the attack on the vintner’s home? As readers we know that the vintner and Haredale are within the house as Hugh is attacking the house from the outside. We know who knocked Hugh off his horse.

Where, oh where, is Dennis? A mob attack on a wine storage establishment should have been of great interest to him.

We see Barnaby trying to help Hugh escape from the mob. What can account for Barnaby’s seemingly lack of interest in any more looting?

Chapter 69

The chapter opens with some friction between Barnaby and his father. It seems that Mr Barnaby is becoming paranoid. As Barnaby approaches his father with Hugh, Mr Barnaby slinks off. When approached by Barnaby he accuses his son of meeting with his mother and plotting to betray him. In fact, Barnaby feels a touch of fear when talking to his father. Mr Barnaby wants to know where the blind man is and questions his son about the chosen hiding place. Mr Barnaby recoils at the sight of the blood on Hugh. Mr Barnaby then covers his head with a cloak to hide Hugh and his blood from his sight. This scene reminds me a bit of the reactions of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth to Duncan’s blood.

Meanwhile, Hugh is moaning and groaning, partly from his loss of blood, partly from the pain of falling off his horse, and probably in some agony due to his excessive drinking. No doubt somewhat confused and stressed himself, Barnaby strolls out into the fields and the sweet and pleasant air. His mind flashes back to his tranquil past and to wandering the fields with his friends the dogs accompanying him. We are told that Barnaby “had no consciousness, God help him, of having done wrong.” As our novel moves towards its conclusion Dickens is drawing clear comparisons between life in rural England and life in the city of London. Barnaby thinks how happy his mother, Hugh, his father and himself would be if they went to live “in some lonely place.” Soon, however, Barnaby’s musings are interrupted and he is once again approached by his father who demands Barnaby return to London and find the blind man. Barnaby disguises himself lest he be recognized in the streets of London and sets off again. During the day we read that Mr Barnaby’s mind is flashing back to the night of the murders. That night Barnaby returns again, this time with the blind man.

Thoughts

The beginning of this chapter gives us much insight into the nature of Barnaby. Once Barnaby is surrounded by a rural landscape his mind reverts to a more tranquil place. We also learn that Barnaby does not have much recall of the tumultuous times he has recently been involved in London with the mob. We also see that his father is becoming plagued, almost like Macbeth, with the images of those he has murdered.

To what extent do you think Barnaby should be pitied by the reading audience?

Do you think Mr Barnaby has any true or emotional attachment to his son?

This is the first time we have seen Hugh as being, in any way, subdued in nature. Is it only because of his injuries and loss of blood or is Dickens signalling something else in the beginning of this chapter?

The first information that Mr Barnaby wants is know from Stagg is whether Mrs Barnaby has been found, and, if so, will she say anything to save him. The answer from Stagg is a simple no. We do learn that Mrs Barnaby is heartbroken at the loss of her son, and that her health has suffered as a result. Mrs Barnaby believes that “Heaven will help her and her innocent son” Stagg suggests that Mr Barnaby and his son keep moving and that, in time, Mrs Barnaby will come round to their point of view. The next thing we know Dennis shows up but acts strangely. He did not want to enter the place they were staying and he is now dressed much like he was when he performed his duties as a hangman. Dennis tells the others that he found them due to the bells they had on their horses. Hugh questions Dennis as to where he went yesterday after he left the jail. As the conversation continues it is noticeable that Dennis's demeanour is slowly shifting. A trap! Dennis signals and a band of soldiers appear. Their friend Dennis has turned on his former rioter partners. He now claims to be acting on “constitootional princlples.” Another more simple way to phrase it is that Dennis has lead the soldiers to the place where they can capture two people who were rioting and one who is an escaped felon. It seems that the price on the heads of Hugh, Barnaby, and Mr Barnaby was more than Dennis could pass up. Dennis is an opportunist and he has just made himself some money and perhaps even provided himself with three men to hang. In all the confusion Stagg attempts to escape. Well, almost escape. He is asked to surrender by the soldiers and yet he keeps running. The order to fire is given and the troops do so. Stagg is killed. On his body is found rings and money, no doubt stolen during the looting of homes and businesses during the riots. Dennis is upset that he didn’t get to “work off” Stagg. Dickens has great fun with Dennis (in a black humour kind of way) when he has Dennis ramble on about the constitution and every man’s right to be hanged by Dennis. As the troops take the prisons away we are told that Barnaby attempted to wave at Hugh. For his part, Hugh envisions the mob will set him free him from jail just as the mob had previously freed Barnaby and his father earlier in the week. By the end of the chapter, however, Hugh is more realistic and realizes that he is “riding to his death.”

Thoughts

Barnaby and his father have been captured for the second time. To what extent do you think Dickens is overwriting the plot at this point in the novel?

We have finally had a bit of news about Mrs Barnaby. Do you think Dickens has keep her out of the story for too long?

What do you think the purpose was of having the troops shot and kill Stagg?

Dickens has clearly indicated how a rural setting is linked to a kinder and gentler Barnaby. Do you find Barnaby’s swings in character and personality to be annoying, enlightening, symbolic? To what extent could Dickens be making a larger comment on the nature of country versus city life?

Does anyone have any idea why Dickens created the character Stagg as blind?

The chapter opens with some friction between Barnaby and his father. It seems that Mr Barnaby is becoming paranoid. As Barnaby approaches his father with Hugh, Mr Barnaby slinks off. When approached by Barnaby he accuses his son of meeting with his mother and plotting to betray him. In fact, Barnaby feels a touch of fear when talking to his father. Mr Barnaby wants to know where the blind man is and questions his son about the chosen hiding place. Mr Barnaby recoils at the sight of the blood on Hugh. Mr Barnaby then covers his head with a cloak to hide Hugh and his blood from his sight. This scene reminds me a bit of the reactions of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth to Duncan’s blood.

Meanwhile, Hugh is moaning and groaning, partly from his loss of blood, partly from the pain of falling off his horse, and probably in some agony due to his excessive drinking. No doubt somewhat confused and stressed himself, Barnaby strolls out into the fields and the sweet and pleasant air. His mind flashes back to his tranquil past and to wandering the fields with his friends the dogs accompanying him. We are told that Barnaby “had no consciousness, God help him, of having done wrong.” As our novel moves towards its conclusion Dickens is drawing clear comparisons between life in rural England and life in the city of London. Barnaby thinks how happy his mother, Hugh, his father and himself would be if they went to live “in some lonely place.” Soon, however, Barnaby’s musings are interrupted and he is once again approached by his father who demands Barnaby return to London and find the blind man. Barnaby disguises himself lest he be recognized in the streets of London and sets off again. During the day we read that Mr Barnaby’s mind is flashing back to the night of the murders. That night Barnaby returns again, this time with the blind man.

Thoughts

The beginning of this chapter gives us much insight into the nature of Barnaby. Once Barnaby is surrounded by a rural landscape his mind reverts to a more tranquil place. We also learn that Barnaby does not have much recall of the tumultuous times he has recently been involved in London with the mob. We also see that his father is becoming plagued, almost like Macbeth, with the images of those he has murdered.

To what extent do you think Barnaby should be pitied by the reading audience?

Do you think Mr Barnaby has any true or emotional attachment to his son?

This is the first time we have seen Hugh as being, in any way, subdued in nature. Is it only because of his injuries and loss of blood or is Dickens signalling something else in the beginning of this chapter?

The first information that Mr Barnaby wants is know from Stagg is whether Mrs Barnaby has been found, and, if so, will she say anything to save him. The answer from Stagg is a simple no. We do learn that Mrs Barnaby is heartbroken at the loss of her son, and that her health has suffered as a result. Mrs Barnaby believes that “Heaven will help her and her innocent son” Stagg suggests that Mr Barnaby and his son keep moving and that, in time, Mrs Barnaby will come round to their point of view. The next thing we know Dennis shows up but acts strangely. He did not want to enter the place they were staying and he is now dressed much like he was when he performed his duties as a hangman. Dennis tells the others that he found them due to the bells they had on their horses. Hugh questions Dennis as to where he went yesterday after he left the jail. As the conversation continues it is noticeable that Dennis's demeanour is slowly shifting. A trap! Dennis signals and a band of soldiers appear. Their friend Dennis has turned on his former rioter partners. He now claims to be acting on “constitootional princlples.” Another more simple way to phrase it is that Dennis has lead the soldiers to the place where they can capture two people who were rioting and one who is an escaped felon. It seems that the price on the heads of Hugh, Barnaby, and Mr Barnaby was more than Dennis could pass up. Dennis is an opportunist and he has just made himself some money and perhaps even provided himself with three men to hang. In all the confusion Stagg attempts to escape. Well, almost escape. He is asked to surrender by the soldiers and yet he keeps running. The order to fire is given and the troops do so. Stagg is killed. On his body is found rings and money, no doubt stolen during the looting of homes and businesses during the riots. Dennis is upset that he didn’t get to “work off” Stagg. Dickens has great fun with Dennis (in a black humour kind of way) when he has Dennis ramble on about the constitution and every man’s right to be hanged by Dennis. As the troops take the prisons away we are told that Barnaby attempted to wave at Hugh. For his part, Hugh envisions the mob will set him free him from jail just as the mob had previously freed Barnaby and his father earlier in the week. By the end of the chapter, however, Hugh is more realistic and realizes that he is “riding to his death.”

Thoughts

Barnaby and his father have been captured for the second time. To what extent do you think Dickens is overwriting the plot at this point in the novel?

We have finally had a bit of news about Mrs Barnaby. Do you think Dickens has keep her out of the story for too long?

What do you think the purpose was of having the troops shot and kill Stagg?

Dickens has clearly indicated how a rural setting is linked to a kinder and gentler Barnaby. Do you find Barnaby’s swings in character and personality to be annoying, enlightening, symbolic? To what extent could Dickens be making a larger comment on the nature of country versus city life?

Does anyone have any idea why Dickens created the character Stagg as blind?

Chapter 70

Chapter 70 opens with a tone of casual brutality. Our friend Dennis the hangman feels no guilt in turning in his recent riot mates and eases his conscious by assuring himself that it was his constitutional duty to capture such miscreants as Hugh, Barnaby, and Barnaby’s father. Dennis has decided to retire into “the tranquil respectability” of private life and so he heads off to solace himself with “half an hour or so of female society.” I am sure that Emma, Dolly, and even Miggs will not be happy to see him. As he walks through the detritus of the London riots he does not see the destruction as much as an increased opportunity to “work off” many of the mob when they are captured. He does not see himself as in any danger himself as he reasons that he will not be identified as a participant in the mob’s activities. Even if he is identified, Dennis is convinced his usefulness as a hangman will grand him a free get out of jail card. Dennis does realize that the fact of the forceful detention of Dolly and Emma is not the brightest of his decisions, but he has confidence in his own quick intelligence.

When he arrives where Emma, Dolly, and Miggs are held Miggs launches into a self-delusional ramble. Miggs says that Simmuns is her own. What follows is a weirdly humorous sequence where Miggs cloying claims she is not “Wenus” and Dennis assures her she is. Dennis learns from Miggs that Tappertit was with the prisoners the day before and Dennis hints that it is Tappertit’s intention to take Dolly with him, not Miggs. Dennis tells Miggs that she was to be handed over to someone else. Dennis then insinuates that he will “get [Dolly] off” for her. With this revelation, Miggs brightens up considerably but then switches to the point that she does not want to seek vengeance on Sim. I winced and then chucked when Dennis then calls Miggs “sugar-stick.” Such an endearing phrase. During this and the following conversation Miggs has stopped her ears with her hand but remains remarkably aware of all Dennis has to say. I found this humorous and could picture the scene performed on stage. Indeed, consider the stage with Dolly and Emma cowering in the background, and Miggs and Dennis in the foreground with Miggs listening intently to everything Dennis has to say while keeping her ears apparently covered so she can hear nothing. With tragedy comes comedy in this chapter. Miggs thinks that Gashford was planning to remove Emma tomorrow night.

Thoughts

Why do you suppose Dennis wants to find out what everyone else is thinking and planning to do in this chapter?

Has your opinion changed about Dennis from reading his interactions with Miggs?

To what extent do you think Dickens wanted this chapter to be humourous? Why/why not?

Dennis has a plan for the removal of Dolly and Miggs. Dennis plans to get one of the rioters who, fearing for his life, would be glad of the opportunity to flee the country. The fact that this man would be with a beautiful woman would act as a further enhancement to the plan. How and what would happen to Dolly at the hands of this man “would rest entirely with himself.” Dennis seems very happy to dismiss any person’s life without a thought. This plan would certainly not favour the safety of Dolly in any way. If such an action did occur, Miggs saw it as a lesson to Varden and his wife. So much for loyalty.

The conversation ends, Dennis goes off to pursue his plan, and Miggs launches into a “burst of mental anguish” which Dolly attempts to sooth. As the chapter ends we realize that Miggs has conducted herself in an amazing fashion. Even with her ears plugged, she has heard every word that Dennis spoke.

Thoughts

How would you describe the conduct of Miggs? Is it humourous, annoying or some other word or phrase?

Things are looking grim for Dolly and Emma. Well, Miggs too, I guess, but it is hard to have much sympathy for her. What do you think will occur next? What is your reasoning?

Reflections

I wrote these recaps during the week of August 11-18. August 16th was the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo Riots in Manchester. Barnaby Rudge was written some 180 years ago. The issue of people’s rights, their grievances, the way people demonstrate their dissent and the myriad of conflicting points of view that emerge in any arena of protest echo those of the Gordon Riots. If we go further back in history there are countless other examples of dissent as well.

Dickens is rightly seen as a champion of the poor, a writer who pointed out the flaws and weaknesses of government, the law, and those who hold the most power in society. Certainly, Dickens also saw how money influences a person’s life and beliefs.

Barnaby Rudge is one of two novels that are classified as historical fiction. The other is A Tale of Two Cities. At the completion of each novel the Curiosities generally have a week when we discuss the novel as a whole. As we move ever closer to the end of the novel perhaps one question to consider is to what extent can we - or should we - read Barnaby Rudge as an historical novel? To what extent can we see the novel as a reflection of the people and the times?

Chapter 70 opens with a tone of casual brutality. Our friend Dennis the hangman feels no guilt in turning in his recent riot mates and eases his conscious by assuring himself that it was his constitutional duty to capture such miscreants as Hugh, Barnaby, and Barnaby’s father. Dennis has decided to retire into “the tranquil respectability” of private life and so he heads off to solace himself with “half an hour or so of female society.” I am sure that Emma, Dolly, and even Miggs will not be happy to see him. As he walks through the detritus of the London riots he does not see the destruction as much as an increased opportunity to “work off” many of the mob when they are captured. He does not see himself as in any danger himself as he reasons that he will not be identified as a participant in the mob’s activities. Even if he is identified, Dennis is convinced his usefulness as a hangman will grand him a free get out of jail card. Dennis does realize that the fact of the forceful detention of Dolly and Emma is not the brightest of his decisions, but he has confidence in his own quick intelligence.

When he arrives where Emma, Dolly, and Miggs are held Miggs launches into a self-delusional ramble. Miggs says that Simmuns is her own. What follows is a weirdly humorous sequence where Miggs cloying claims she is not “Wenus” and Dennis assures her she is. Dennis learns from Miggs that Tappertit was with the prisoners the day before and Dennis hints that it is Tappertit’s intention to take Dolly with him, not Miggs. Dennis tells Miggs that she was to be handed over to someone else. Dennis then insinuates that he will “get [Dolly] off” for her. With this revelation, Miggs brightens up considerably but then switches to the point that she does not want to seek vengeance on Sim. I winced and then chucked when Dennis then calls Miggs “sugar-stick.” Such an endearing phrase. During this and the following conversation Miggs has stopped her ears with her hand but remains remarkably aware of all Dennis has to say. I found this humorous and could picture the scene performed on stage. Indeed, consider the stage with Dolly and Emma cowering in the background, and Miggs and Dennis in the foreground with Miggs listening intently to everything Dennis has to say while keeping her ears apparently covered so she can hear nothing. With tragedy comes comedy in this chapter. Miggs thinks that Gashford was planning to remove Emma tomorrow night.

Thoughts

Why do you suppose Dennis wants to find out what everyone else is thinking and planning to do in this chapter?

Has your opinion changed about Dennis from reading his interactions with Miggs?

To what extent do you think Dickens wanted this chapter to be humourous? Why/why not?

Dennis has a plan for the removal of Dolly and Miggs. Dennis plans to get one of the rioters who, fearing for his life, would be glad of the opportunity to flee the country. The fact that this man would be with a beautiful woman would act as a further enhancement to the plan. How and what would happen to Dolly at the hands of this man “would rest entirely with himself.” Dennis seems very happy to dismiss any person’s life without a thought. This plan would certainly not favour the safety of Dolly in any way. If such an action did occur, Miggs saw it as a lesson to Varden and his wife. So much for loyalty.

The conversation ends, Dennis goes off to pursue his plan, and Miggs launches into a “burst of mental anguish” which Dolly attempts to sooth. As the chapter ends we realize that Miggs has conducted herself in an amazing fashion. Even with her ears plugged, she has heard every word that Dennis spoke.

Thoughts

How would you describe the conduct of Miggs? Is it humourous, annoying or some other word or phrase?

Things are looking grim for Dolly and Emma. Well, Miggs too, I guess, but it is hard to have much sympathy for her. What do you think will occur next? What is your reasoning?

Reflections

I wrote these recaps during the week of August 11-18. August 16th was the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo Riots in Manchester. Barnaby Rudge was written some 180 years ago. The issue of people’s rights, their grievances, the way people demonstrate their dissent and the myriad of conflicting points of view that emerge in any arena of protest echo those of the Gordon Riots. If we go further back in history there are countless other examples of dissent as well.

Dickens is rightly seen as a champion of the poor, a writer who pointed out the flaws and weaknesses of government, the law, and those who hold the most power in society. Certainly, Dickens also saw how money influences a person’s life and beliefs.

Barnaby Rudge is one of two novels that are classified as historical fiction. The other is A Tale of Two Cities. At the completion of each novel the Curiosities generally have a week when we discuss the novel as a whole. As we move ever closer to the end of the novel perhaps one question to consider is to what extent can we - or should we - read Barnaby Rudge as an historical novel? To what extent can we see the novel as a reflection of the people and the times?

Whoop, I was right! The one-armed man was Joe!

As a gamer and huge fan of Skyrim, Stagg's trying to flee looked like the fleeing thief at the start of that game to me. I know, it's not really a literary contribution or anything, but somehow I wanted to share.

I must admit that I only started A Tale of Two Cities, and never read far. I'll give it another chance when it is it's time in this group. However, if I remember correctly, it starts with liquor of some kind falling from a cart, and people drinking it's puddles, just like they did in chapter 68. Anyway, I had this huge flashback somehow. What if it is some kind of symbolism as well? Like, people are willing to die and drink something dirty (I mean, I don't believe streets were much cleaner then than they are now, although the dirt might be of a different kind), as long as they are satisfied? People place intoxication above common sense? Something like that?

As a gamer and huge fan of Skyrim, Stagg's trying to flee looked like the fleeing thief at the start of that game to me. I know, it's not really a literary contribution or anything, but somehow I wanted to share.

I must admit that I only started A Tale of Two Cities, and never read far. I'll give it another chance when it is it's time in this group. However, if I remember correctly, it starts with liquor of some kind falling from a cart, and people drinking it's puddles, just like they did in chapter 68. Anyway, I had this huge flashback somehow. What if it is some kind of symbolism as well? Like, people are willing to die and drink something dirty (I mean, I don't believe streets were much cleaner then than they are now, although the dirt might be of a different kind), as long as they are satisfied? People place intoxication above common sense? Something like that?

Jantine wrote: "Whoop, I was right! The one-armed man was Joe!

Jantine wrote: "Whoop, I was right! The one-armed man was Joe!As a gamer and huge fan of Skyrim, Stagg's trying to flee looked like the fleeing thief at the start of that game to me. I know, it's not really a li..."

Jantine, how did you figure that out or even guess that the one-armed man was Joe? That would never have occurred to me. Good for you.

Now my next question is: How are they (Haredale, Varden) going to find Emma and Dolly? I know they will but I can't imagine how. The next question is: Where is Mrs. Rudge? So, I am anxious to read on. I guess my only complaint about this process is the waiting to read the next week's chapters. My first group read on Goodreads, I actually just went ahead and finished the book and abandoned the group. I am doing better with Dickens thus far, but it is difficult for me with certain books.

I do love all the great comments and insights. Thanks to everyone.

Jantine wrote: "Whoop, I was right! The one-armed man was Joe!

As a gamer and huge fan of Skyrim, Stagg's trying to flee looked like the fleeing thief at the start of that game to me. I know, it's not really a li..."

Hi Jantine

It is never a problem to make connections. That’s what EM Forster told us to do! And who are we to argue with him ... ? :-)

Your memory is right about A Tale of Two Cities. There is a wine cask that breaks on a street, and there are many people who drink the spilt wine and it is a massive symbol. It is a great scene.

As a gamer and huge fan of Skyrim, Stagg's trying to flee looked like the fleeing thief at the start of that game to me. I know, it's not really a li..."

Hi Jantine

It is never a problem to make connections. That’s what EM Forster told us to do! And who are we to argue with him ... ? :-)

Your memory is right about A Tale of Two Cities. There is a wine cask that breaks on a street, and there are many people who drink the spilt wine and it is a massive symbol. It is a great scene.

Bobbie wrote: "Jantine wrote: "Whoop, I was right! The one-armed man was Joe!

As a gamer and huge fan of Skyrim, Stagg's trying to flee looked like the fleeing thief at the start of that game to me. I know, it's..."

Hi Bobbie

One of the great things about Dickens is how he manages to bring the plots of his novels together in the end. Sometimes he uses wizardry, sometimes coincidence, and sometimes by pointing out to us what he has been making obvious throughout the novel but the reader seemed to have missed.

You are so right about needing to know but being made to wait as a reader. We must remember that all of Dickens’s major novels were written in either weekly or, more commonly, monthly parts. He needed to keep us readers in suspense so we would buy the next instalment. Every soap opera on TV today and most TV series contain story lines that often have both a problem-resolution plot and an ongoing story line occurring at the same time.

I’m a big fan of the original NCIS series which as been on the air for some 18 years. The writers have teased us viewers with the fact that Ziva, a great character who was supposedly killed some years ago, is still alive. The last episode of this past year had her return to warn of danger ahead for the team. And then, poof, season ended and I can’t wait for the new season to begin.

There is an overused phrase that Dickens’s friend and author Wilkie Collins said to describe how to write a Victorian serial novel for a reading audience. It is “make them laugh, make them cry, make them wait.” So true!

As a gamer and huge fan of Skyrim, Stagg's trying to flee looked like the fleeing thief at the start of that game to me. I know, it's..."

Hi Bobbie

One of the great things about Dickens is how he manages to bring the plots of his novels together in the end. Sometimes he uses wizardry, sometimes coincidence, and sometimes by pointing out to us what he has been making obvious throughout the novel but the reader seemed to have missed.

You are so right about needing to know but being made to wait as a reader. We must remember that all of Dickens’s major novels were written in either weekly or, more commonly, monthly parts. He needed to keep us readers in suspense so we would buy the next instalment. Every soap opera on TV today and most TV series contain story lines that often have both a problem-resolution plot and an ongoing story line occurring at the same time.

I’m a big fan of the original NCIS series which as been on the air for some 18 years. The writers have teased us viewers with the fact that Ziva, a great character who was supposedly killed some years ago, is still alive. The last episode of this past year had her return to warn of danger ahead for the team. And then, poof, season ended and I can’t wait for the new season to begin.

There is an overused phrase that Dickens’s friend and author Wilkie Collins said to describe how to write a Victorian serial novel for a reading audience. It is “make them laugh, make them cry, make them wait.” So true!

Bobbie wrote: "my next question is: How are they (Haredale, Varden) going to find Emma and Dolly? I know they will but I can't imagine how. The next question is: Where is Mrs. Rudge?..."

Bobbie wrote: "my next question is: How are they (Haredale, Varden) going to find Emma and Dolly? I know they will but I can't imagine how. The next question is: Where is Mrs. Rudge?..."My guess is that Joe and Ned will be the ones to rescue Dolly and Emma, thus removing any doubts as to their worthiness, and they will all live happily ever after. But we must wait to see how CD accomplishes this feat. And what of Miggs? She and Tappertit surely can't ride off into the sunset together (though it may be a crueler sentence for Sim than hanging would be).

Where IS Mrs. Rudge? It can't be so easy as that she's returned to her London house, can it? That makes the most sense, and Haredale hasn't been on watch there since she's returned to town, so it's probable. She'd have to go somewhere where Barnaby might think to look for her.

Did anyone else notice this paragraph in chapter 69?

Did anyone else notice this paragraph in chapter 69?"Well," said Mr. Dennis, mournfully, "if you an't enough to make a man mistrust his feller-creeturs, I don't know what is. Desert the banners! Me! Ned Dennis, as was so christened by his own father! - Is this axe your'n, brother?"

Is it just a coincidence that Dennis's first name is Ned, and that Edward Chester's nick-name is also Ned? As horrible a father as Chester is, I think I'd rather share a gene pool with him than Dennis. Awful options, though!

The return of Joe and Ned (Chester, not Dennis) has been long-awaited, and the escape from the vintner's house was gripping. But I've about had it with the riots - and the rioters, for that matter - and I'm hoping that we'll now get back to the family stories. I don't mind a good action film if it's got a good story behind it but, when reading, I find it more challenging to follow text that is mostly descriptive with little dialogue. Humor, bucolic scenes, and happy families always draw me in more than mayhem and destruction. But warmth and light are always appreciated more after we've been out in the cold darkness, so a bit of chaos is necessary.

The return of Joe and Ned (Chester, not Dennis) has been long-awaited, and the escape from the vintner's house was gripping. But I've about had it with the riots - and the rioters, for that matter - and I'm hoping that we'll now get back to the family stories. I don't mind a good action film if it's got a good story behind it but, when reading, I find it more challenging to follow text that is mostly descriptive with little dialogue. Humor, bucolic scenes, and happy families always draw me in more than mayhem and destruction. But warmth and light are always appreciated more after we've been out in the cold darkness, so a bit of chaos is necessary.

Dickens seems to emphasize through both Gruesby and Barnaby that Gordon is not to blame and should not be held responsible for the rioters. I don't know how this jibes with history, but as readers of a work of fiction, how do all of you react to that?

Dickens seems to emphasize through both Gruesby and Barnaby that Gordon is not to blame and should not be held responsible for the rioters. I don't know how this jibes with history, but as readers of a work of fiction, how do all of you react to that? If I'm to give Gordon any leeway here, the least he must do for my satisfaction is get out there on his pulpit, denounce the rioters, call for calm, and insist that anyone violating the peace be arrested and prosecuted for their crimes. Dickens hasn't shown Gordon doing that.

[FYI - Off topic]

[FYI - Off topic]Bobbie wrote: "I am anxious to read on. I guess my only complaint about this process is the waiting to read the next week's chapters. My first group read on Goodreads, I actually just went ahead and finished the book and abandoned the group...."

Bobbie - I won't tell if you read ahead. ;-) You just need to be careful about spoilers. I try not to do it for that reason, and also because the more I read, the more I'll forget about that week's selection when discussion time comes.

I've been in other groups that are not structured at all. The book is announced and people comment on it or not as they see fit - sometimes on the book as a whole, sometimes on sections if it's a longer book. But for me, they all pale in comparison the structure we have here, where we are all discussing (if not actually reading) at the same pace. And no other group I've belonged to has had such meaty, thought-provoking discussions!

When I'm ahead on the reading schedule, I use the extra time for non-Dickens reading. But when life gets hectic, this slower pace is greatly appreciated!

Bobbie wrote: "JJantine, how did you figure that out or even guess that the one-armed man was Joe? That would never have occurred to me. Good for you. "

It might have been because I've read more Dickens, in combination with the discussions here. I noticed how everyone longed for Edward and Joe getting involved in the story again (or at least everyone was curious where the heck they were), and lo and behold, here is this mysterious one-armed man that has a connection to the army! Oh wait, Joe went into the army to disappear, didn't he? Like I said last week, I think it is very Dickens to let us as a reader think afterwards "yes, off course, I could have known!" ;-)

It might have been because I've read more Dickens, in combination with the discussions here. I noticed how everyone longed for Edward and Joe getting involved in the story again (or at least everyone was curious where the heck they were), and lo and behold, here is this mysterious one-armed man that has a connection to the army! Oh wait, Joe went into the army to disappear, didn't he? Like I said last week, I think it is very Dickens to let us as a reader think afterwards "yes, off course, I could have known!" ;-)

I am having trouble though remembering what was said about this mysterious one armed man. I would like to go back and read those spots but don't know where to find them.

I am having trouble though remembering what was said about this mysterious one armed man. I would like to go back and read those spots but don't know where to find them. And as for reading ahead, I don't really do it because as you said, Mary Lou, if I do read ahead I forget what was in what section and forget what we need to comment on. I have been reading a little cozy mystery series in between the sections and that has worked nicely.

About Staggs: When I read the passage of how he tried to escape and was shot down by the soldiers, I couldn't help thinking that he was wasted in a way. He is one of the most interesting villains in the novel - next to Hugh - and therefore I think he has been dispatched a little bit too early. In a way, he is rather important a villain in that his whisperings of gold and of how it can be found in cities instead of in the countryside, made Barnaby want to go to London and got him into the predicament we find him and his mother in.

So, from a point of view of dramaturgy, Staggs could have been of further use to the author, but apparently Dickens thought that he had got the most out of that character ... Nevertheless, I think it very strange that a cunning man like Staggs should try to run away like that, with the odds being so strongly against him. Would he not be clever enough to await a better opportunity.

His blindness makes him even more fascinating to me. First because the deprivation of the important visual sense must have honed other senses in him, and so I find it very believable that he is able to manipulate Barnaby and his mother so easily. Maybe, a person's tone and manner of speaking tell him more things than are accessible to other people's perception. Second, I was fascinated by what he said about people's expectations as to a blind man's moral qualities. In a way, this is true: Somehow, we tend to expect members of minorities - such as people with disabilities - to be more patient, more caring and more virtuous. In a way, this is a strange kind of prejudice, one that Staggs has learned to turn to his own advantage.

One question remains for me: Why should the blind villain have wanted to tie his fate to Mr. Rudge's? Why did he help him? And how did he ever find Mrs. Rudge and Barnaby?

So, from a point of view of dramaturgy, Staggs could have been of further use to the author, but apparently Dickens thought that he had got the most out of that character ... Nevertheless, I think it very strange that a cunning man like Staggs should try to run away like that, with the odds being so strongly against him. Would he not be clever enough to await a better opportunity.

His blindness makes him even more fascinating to me. First because the deprivation of the important visual sense must have honed other senses in him, and so I find it very believable that he is able to manipulate Barnaby and his mother so easily. Maybe, a person's tone and manner of speaking tell him more things than are accessible to other people's perception. Second, I was fascinated by what he said about people's expectations as to a blind man's moral qualities. In a way, this is true: Somehow, we tend to expect members of minorities - such as people with disabilities - to be more patient, more caring and more virtuous. In a way, this is a strange kind of prejudice, one that Staggs has learned to turn to his own advantage.

One question remains for me: Why should the blind villain have wanted to tie his fate to Mr. Rudge's? Why did he help him? And how did he ever find Mrs. Rudge and Barnaby?

Mary Lou wrote: "Did anyone else notice this paragraph in chapter 69?

"Well," said Mr. Dennis, mournfully, "if you an't enough to make a man mistrust his feller-creeturs, I don't know what is. Desert the banners! ..."

As far as I know, there was really a hangman called Edward Dennis at the time of the Gordon riots, and Dickens simply put him into the book, changing the man's character to a certain extent, however.

"Well," said Mr. Dennis, mournfully, "if you an't enough to make a man mistrust his feller-creeturs, I don't know what is. Desert the banners! ..."

As far as I know, there was really a hangman called Edward Dennis at the time of the Gordon riots, and Dickens simply put him into the book, changing the man's character to a certain extent, however.

Peter wrote: "Dickens is rightly seen as a champion of the poor, a writer who pointed out the flaws and weaknesses of government, the law, and those who hold the most power in society. Certainly, Dickens also saw how money influences a person’s life and beliefs. "

Dickens certainly was a champion of the poor and a critic of social and political injustices, but it is interesting that he is wholeheartedly on the side of the authorities in Barnaby Rudge. He criticizes certain weak and opportunistic officials, like the Mayor of London, and reactionaries like the country "gentleman", but he advocates the repression of the riots through the military - whose hands were tied at first by the lack of decision on the authorities' part - unquestioningly. Likewise, two of the positive characters, Joe and Edward, are soldiers.

In Tale of Two Cities, this is similar: The narration dwells on the horrors and cruelties that arise when the suppressed masses resort to violence even though he concedes that they have many reasons for being dissatisfied with their lives.

Dickens is clearly a man of reform and not of revolution, isn't he?

Dickens certainly was a champion of the poor and a critic of social and political injustices, but it is interesting that he is wholeheartedly on the side of the authorities in Barnaby Rudge. He criticizes certain weak and opportunistic officials, like the Mayor of London, and reactionaries like the country "gentleman", but he advocates the repression of the riots through the military - whose hands were tied at first by the lack of decision on the authorities' part - unquestioningly. Likewise, two of the positive characters, Joe and Edward, are soldiers.

In Tale of Two Cities, this is similar: The narration dwells on the horrors and cruelties that arise when the suppressed masses resort to violence even though he concedes that they have many reasons for being dissatisfied with their lives.

Dickens is clearly a man of reform and not of revolution, isn't he?

Peter wrote: "How would you describe the conduct of Miggs? Is it humourous, annoying or some other word or phrase?"

Up to this moment, I have always considered Miggs a purely comic character. In real life, she would be a terrible person to have around, but so far, in the novel she has always provided satirical humour. In this scene, though, while there is a lot of humour in that Dennis and Miggs seem to arrive at an understanding without ever stating their intentions in so many words, the nature of their understanding is so horrible that Miggs has made it into the league of villains in this chapter. At the same time, this enhances her importance in the novel.

Up to this moment, I have always considered Miggs a purely comic character. In real life, she would be a terrible person to have around, but so far, in the novel she has always provided satirical humour. In this scene, though, while there is a lot of humour in that Dennis and Miggs seem to arrive at an understanding without ever stating their intentions in so many words, the nature of their understanding is so horrible that Miggs has made it into the league of villains in this chapter. At the same time, this enhances her importance in the novel.

Jantine wrote: "Whoop, I was right! The one-armed man was Joe!

As a gamer and huge fan of Skyrim, Stagg's trying to flee looked like the fleeing thief at the start of that game to me. I know, it's not really a li..."

I used to play "Morrowind" for quite a while, Jantine, but unlike the first two parts of "Gothic", I never finished it. When I played computer games, I was more attracted to strategy games like "Civilization" and "Total War" (Rome, Medieval and the one set in the 18th century).

As a gamer and huge fan of Skyrim, Stagg's trying to flee looked like the fleeing thief at the start of that game to me. I know, it's not really a li..."

I used to play "Morrowind" for quite a while, Jantine, but unlike the first two parts of "Gothic", I never finished it. When I played computer games, I was more attracted to strategy games like "Civilization" and "Total War" (Rome, Medieval and the one set in the 18th century).

Tristram wrote: "About Staggs: When I read the passage of how he tried to escape and was shot down by the soldiers, I couldn't help thinking that he was wasted in a way. He is one of the most interesting villains i..."

Tristram wrote: "About Staggs: When I read the passage of how he tried to escape and was shot down by the soldiers, I couldn't help thinking that he was wasted in a way. He is one of the most interesting villains i..."Staggs was an interesting villain, wasn't he? Seemingly so unassuming. Dickens always seems to have one or two minor characters in his books that seem short-changed, and whom I'd love to know more about. Staggs is that character in Rudge

You (and Dickens) are right about people's assumptions when it comes to the disabled. I wonder why that is? It's really kind of a fascinating phenomenon. We have a large deaf community and I frequently had to serve them in a previous position I held. I learned very quickly (and sadly) that their disability did not make them kinder people. It shouldn't be surprising really - why wouldn't someone with challenges feel bitter? In quite a few cases, it was used to manipulate, or feign a lack of knowledge of our policies and standards of conduct. And I also learned that just because someone is deaf doesn't mean he can't make quite a ruckus when he's angry! (Deaf people are surprisingly noisy!)

Anyhow, I found it very interesting that Dickens took the time to comment on what seems to be a common misconception. Maybe he, like I, was so surprised to come to that realization that he made Staggs blind just to explore it a bit.

Tristram wrote: "About Staggs: When I read the passage of how he tried to escape and was shot down by the soldiers, I couldn't help thinking that he was wasted in a way. He is one of the most interesting villains i..."

Hi Tristram

I agree. Stagg is an interesting and somewhat perplexing creation. He acts as a tenuous link between Tappertit and his crew and Mr Rudge but these two subsets of characters don't really link in any meaningful way in the novel besides being the “bad guys.” How he is able to track down Barnaby and his mother like a bloodhound is rather astounding given the fact he is blind.

His death was a surprise to me as well. Being shot was a surprise. Could it be Dickens did not want to send a blind man to the gallows? Still, being killed as he was is equally inglorious. I don’t recall him being part of the most violent of the Gordon mob. He certainly was not a featured rioter like Duncan, Hugh, or Barnaby. Would his fate have even been hanging?

Hi Tristram

I agree. Stagg is an interesting and somewhat perplexing creation. He acts as a tenuous link between Tappertit and his crew and Mr Rudge but these two subsets of characters don't really link in any meaningful way in the novel besides being the “bad guys.” How he is able to track down Barnaby and his mother like a bloodhound is rather astounding given the fact he is blind.

His death was a surprise to me as well. Being shot was a surprise. Could it be Dickens did not want to send a blind man to the gallows? Still, being killed as he was is equally inglorious. I don’t recall him being part of the most violent of the Gordon mob. He certainly was not a featured rioter like Duncan, Hugh, or Barnaby. Would his fate have even been hanging?

The rioters at work

Chapter 66

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

There being now a great many parties in the streets, each went to work according to its humour, and a dozen houses were quickly blazing, including those of Sir John Fielding and two other justices, and four in Holborn—one of the greatest thoroughfares in London—which were all burning at the same time, and burned until they went out of themselves, for the people cut the engine hose, and would not suffer the firemen to play upon the flames. At one house near Moorfields, they found in one of the rooms some canary birds in cages, and these they cast into the fire alive. The poor little creatures screamed, it was said, like infants, when they were flung upon the blaze; and one man was so touched that he tried in vain to save them, which roused the indignation of the crowd, and nearly cost him his life.

At this same house, one of the fellows who went through the rooms, breaking the furniture and helping to destroy the building, found a child’s doll—a poor toy—which he exhibited at the window to the mob below, as the image of some unholy saint which the late occupants had worshipped. While he was doing this, another man with an equally tender conscience (they had both been foremost in throwing down the canary birds for roasting alive), took his seat on the parapet of the house, and harangued the crowd from a pamphlet circulated by the Association, relative to the true principles of Christianity! Meanwhile the Lord Mayor, with his hands in his pockets, looked on as an idle man might look at any other show, and seemed mightily satisfied to have got a good place.

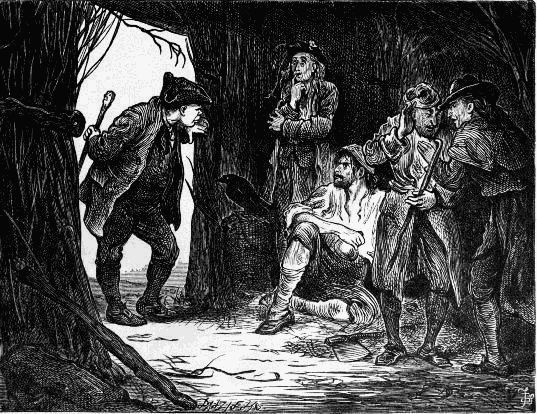

To the rescue

Chapter 67

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The vaults were profoundly dark, and having no torch or candle—for they had been afraid to carry one, lest it should betray their place of refuge—they were obliged to grope with their hands. But they were not long without light, for they had not gone far when they heard the crowd forcing the door; and, looking back among the low-arched passages, could see them in the distance, hurrying to and fro with flashing links, broaching the casks, staving the great vats, turning off upon the right hand and the left, into the different cellars, and lying down to drink at the channels of strong spirits which were already flowing on the ground.

They hurried on, not the less quickly for this; and had reached the only vault which lay between them and the passage out, when suddenly, from the direction in which they were going, a strong light gleamed upon their faces; and before they could slip aside, or turn back, or hide themselves, two men (one bearing a torch) came upon them, and cried in an astonished whisper, ‘Here they are!’

At the same instant they pulled off what they wore upon their heads. Mr Haredale saw before him Edward Chester, and then saw, when the vintner gasped his name, Joe Willet.

Ay, the same Joe, though with an arm the less, who used to make the quarterly journey on the grey mare to pay the bill to the purple-faced vintner; and that very same purple-faced vintner, formerly of Thames Street, now looked him in the face, and challenged him by name.

‘Give me your hand,’ said Joe softly, taking it whether the astonished vintner would or no. ‘Don’t fear to shake it; it’s a friendly one and a hearty one, though it has no fellow. Why, how well you look and how bluff you are! And you—God bless you, sir. Take heart, take heart. We’ll find them. Be of good cheer; we have not been idle.’

There was something so honest and frank in Joe’s speech, that Mr Haredale put his hand in his involuntarily, though their meeting was suspicious enough. But his glance at Edward Chester, and that gentleman’s keeping aloof, were not lost upon Joe, who said bluntly, glancing at Edward while he spoke:

‘Times are changed, Mr Haredale, and times have come when we ought to know friends from enemies, and make no confusion of names. Let me tell you that but for this gentleman, you would most likely have been dead by this time, or badly wounded at the best.’

‘What do you say?’ cried Mr Haredale.

‘I say,’ said Joe, ‘first, that it was a bold thing to be in the crowd at all disguised as one of them; though I won’t say much about that, on second thoughts, for that’s my case too. Secondly, that it was a brave and glorious action—that’s what I call it—to strike that fellow off his horse before their eyes!’

‘What fellow! Whose eyes!’

‘What fellow, sir!’ cried Joe: ‘a fellow who has no goodwill to you, and who has the daring and devilry in him of twenty fellows. I know him of old. Once in the house, HE would have found you, here or anywhere. The rest owe you no particular grudge, and, unless they see you, will only think of drinking themselves dead. But we lose time. Are you ready?’

‘Quite,’ said Edward. ‘Put out the torch, Joe, and go on. And be silent, there’s a good fellow.’

‘Silent or not silent,’ murmured Joe, as he dropped the flaring link upon the ground, crushed it with his foot, and gave his hand to Mr Haredale, ‘it was a brave and glorious action;—no man can alter that.’

Both Mr Haredale and the worthy vintner were too amazed and too much hurried to ask any further questions, so followed their conductors in silence. It seemed, from a short whispering which presently ensued between them and the vintner relative to the best way of escape, that they had entered by the back-door, with the connivance of John Grueby, who watched outside with the key in his pocket, and whom they had taken into their confidence. A party of the crowd coming up that way, just as they entered, John had double-locked the door again, and made off for the soldiers, so that means of retreat was cut off from under them.

However, as the front-door had been forced, and this minor crowd, being anxious to get at the liquor, had no fancy for losing time in breaking down another, but had gone round and got in from Holborn with the rest, the narrow lane in the rear was quite free of people. So, when they had crawled through the passage indicated by the vintner (which was a mere shelving-trap for the admission of casks), and had managed with some difficulty to unchain and raise the door at the upper end, they emerged into the street without being observed or interrupted. Joe still holding Mr Haredale tight, and Edward taking the same care of the vintner, they hurried through the streets at a rapid pace; occasionally standing aside to let some fugitives go by, or to keep out of the way of the soldiers who followed them, and whose questions, when they halted to put any, were speedily stopped by one whispered word from Joe.

The rabble's orgy

Chapter 68

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The vintner’s house with a half-a-dozen others near at hand, was one great, glowing blaze. All night, no one had essayed to quench the flames, or stop their progress; but now a body of soldiers were actively engaged in pulling down two old wooden houses, which were every moment in danger of taking fire, and which could scarcely fail, if they were left to burn, to extend the conflagration immensely. The tumbling down of nodding walls and heavy blocks of wood, the hooting and the execrations of the crowd, the distant firing of other military detachments, the distracted looks and cries of those whose habitations were in danger, the hurrying to and fro of frightened people with their goods; the reflections in every quarter of the sky, of deep, red, soaring flames, as though the last day had come and the whole universe were burning; the dust, and smoke, and drift of fiery particles, scorching and kindling all it fell upon; the hot unwholesome vapour, the blight on everything; the stars, and moon, and very sky, obliterated;—made up such a sum of dreariness and ruin, that it seemed as if the face of Heaven were blotted out, and night, in its rest and quiet, and softened light, never could look upon the earth again.

But there was a worse spectacle than this—worse by far than fire and smoke, or even the rabble’s unappeasable and maniac rage. The gutters of the street, and every crack and fissure in the stones, ran with scorching spirit, which being dammed up by busy hands, overflowed the road and pavement, and formed a great pool, into which the people dropped down dead by dozens. They lay in heaps all round this fearful pond, husbands and wives, fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, women with children in their arms and babies at their breasts, and drank until they died. While some stooped with their lips to the brink and never raised their heads again, others sprang up from their fiery draught, and danced, half in a mad triumph, and half in the agony of suffocation, until they fell, and steeped their corpses in the liquor that had killed them. Nor was even this the worst or most appalling kind of death that happened on this fatal night. From the burning cellars, where they drank out of hats, pails, buckets, tubs, and shoes, some men were drawn, alive, but all alight from head to foot; who, in their unendurable anguish and suffering, making for anything that had the look of water, rolled, hissing, in this hideous lake, and splashed up liquid fire which lapped in all it met with as it ran along the surface, and neither spared the living nor the dead. On this last night of the great riots—for the last night it was—the wretched victims of a senseless outcry, became themselves the dust and ashes of the flames they had kindled, and strewed the public streets of London.

Carrying off the prisoners

Chapter 69

George Cattermole

Text Illustrated:

‘There!’ said Dennis, who remained untouched among them when they had seized their prisoners; ‘it’s them two young ones, gentlemen, that the proclamation puts a price on. This other’s an escaped felon.—I’m sorry for it, brother,’ he added, in a tone of resignation, addressing himself to Hugh; ‘but you’ve brought it on yourself; you forced me to do it; you wouldn’t respect the soundest constitootional principles, you know; you went and wiolated the wery framework of society. I had sooner have given away a trifle in charity than done this, I would upon my soul.—If you’ll keep fast hold on ‘em, gentlemen, I think I can make a shift to tie ‘em better than you can.’

But this operation was postponed for a few moments by a new occurrence. The blind man, whose ears were quicker than most people’s sight, had been alarmed, before Barnaby, by a rustling in the bushes, under cover of which the soldiers had advanced. He retreated instantly—had hidden somewhere for a minute—and probably in his confusion mistaking the point at which he had emerged, was now seen running across the open meadow.

An officer cried directly that he had helped to plunder a house last night. He was loudly called on, to surrender. He ran the harder, and in a few seconds would have been out of gunshot. The word was given, and the men fired.

There was a breathless pause and a profound silence, during which all eyes were fixed upon him. He had been seen to start at the discharge, as if the report had frightened him. But he neither stopped nor slackened his pace in the least, and ran on full forty yards further. Then, without one reel or stagger, or sign of faintness, or quivering of any limb, he dropped.

Some of them hurried up to where he lay;—the hangman with them. Everything had passed so quickly, that the smoke had not yet scattered, but curled slowly off in a little cloud, which seemed like the dead man’s spirit moving solemnly away. There were a few drops of blood upon the grass—more, when they turned him over—that was all.

‘Look here! Look here!’ said the hangman, stooping one knee beside the body, and gazing up with a disconsolate face at the officer and men. ‘Here’s a pretty sight!’

‘Stand out of the way,’ replied the officer. ‘Serjeant! see what he had about him.’

The man turned his pockets out upon the grass, and counted, besides some foreign coins and two rings, five-and-forty guineas in gold. These were bundled up in a handkerchief and carried away; the body remained there for the present, but six men and the serjeant were left to take it to the nearest public-house.

‘Now then, if you’re going,’ said the serjeant, clapping Dennis on the back, and pointing after the officer who was walking towards the shed.

To which Mr Dennis only replied, ‘Don’t talk to me!’ and then repeated what he had said before, namely, ‘Here’s a pretty sight!’

‘It’s not one that you care for much, I should think,’ observed the serjeant coolly.

‘Why, who,’ said Mr Dennis rising, ‘should care for it, if I don’t?’

‘Oh! I didn’t know you was so tender-hearted,’ said the serjeant. ‘That’s all!’

‘Tender-hearted!’ echoed Dennis. ‘Tender-hearted! Look at this man. Do you call THIS constitootional? Do you see him shot through and through instead of being worked off like a Briton? Damme, if I know which party to side with. You’re as bad as the other. What’s to become of the country if the military power’s to go a superseding the ciwilians in this way? Where’s this poor feller-creetur’s rights as a citizen, that he didn’t have ME in his last moments! I was here. I was willing. I was ready. These are nice times, brother, to have the dead crying out against us in this way, and sleep comfortably in our beds arterwards; wery nice!’

Whether he derived any material consolation from binding the prisoners, is uncertain; most probably he did. At all events his being summoned to that work, diverted him, for the time, from these painful reflections, and gave his thoughts a more congenial occupation.

They were not all three carried off together, but in two parties; Barnaby and his father, going by one road in the centre of a body of foot; and Hugh, fast bound upon a horse, and strongly guarded by a troop of cavalry, being taken by another.