The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son

>

D&S, Chp. 8-10

Hello Curiosities,

Life goes on – which might be a bland enough truism, but there are situations, such as watching an episode of Midsomer Murders or sitting in a conference, when you do have to be reminded of it and when it can afford you greatest consolation. Life, then, as they say, goes on, and this also proves true for Little Paul, who is seen through babyhood by Mrs. Chick and Miss Tox, mainly. After the dismissal of Polly Toodle, Paul’s health seems to be in danger, and he grows into a sickly, weak, but at the same time somewhat old-seeming boy. Our narrator sums it up like this,

”The chill of Paul’s christening had struck home, perhaps to some sensitive part of his nature, which could not recover itself in the cold shade of his father; but he was an unfortunate child from that day.”

To support Mrs. Chick and Miss Tox in their endeavours to bring up Paul, Mr. Dombey employs a certain Mrs. Wickam,”who had a surprising natural gift of viewing all subjects in an utterly forlorn and pitiable light”, which might cast another dreary shadow on the Dombey children’s lives. Characteristically, none of the three ladies ever speaks to Mr. Dombey about his son’s frail health, and this, I think, shows how close Pride and Arrogance often come to Failure because it’s clearly Mr. Dombey’s overbearing nature and his stiffness that preclude the sycophantic Mrs. Chick and Miss Tox to broach a subject that might displease him. Instead of enjoying his son’s childhood, Dombey is impatient to see him grow up, to witness his entering into the firm and fulfilling the function of “Son” in the company’s name.

When you consider how people around Mr. Dombey never tell him the truth and how he himself seems to have all priorities wrong – losing out on what makes parenthood so worthwhile and pinning his hopes on a future of his own making instead of valuing the present –, how do you then feel about Dombey? Do you pity him? Despise him? Does he make you feel angry?

When Paul is about five years old, his father by and by suspects that the boy’s health is not as it should be, and Mrs. Chick, in conjunction with Miss Tox, recommend him to send Paul to Brighton, into the house of a Mrs. Pipchin, a respectable widow who has achieved some fame of knowing a lot about how to train children – by giving them whatever they don’t want and depriving them of whatever they would like best. Mr. Dombey, on finding that Mrs. Pipchin’s husband broke his heart over the Peruvian mines, thinks that she is a highly respectable lady and finally consents to the proposal of having Paul sent to Brighton, with Florence for his companion. Mrs. Pipchin’s establishment is, like most of the places Dickens’s heroes have to stay at in their childhood, an extremely bleak place, and there are only two other inmates – young Master Bitherstone and Miss Panckey – as well as Mrs. Pipchin’s niece Berinthia, who is called Berry by the children. Berry seems to be a very nice person but her aunt is a selfish and tyrannous witch, and yet she seems to have taken a fancy to Paul after a strange conversation they had in front of the fire.

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

We might want to regard Mrs. Chick as a sycophant who flatters her brother in order to profit from his vanity. However, when he once speaks gruffly to her, she says, ”’My dear Paul, […] I must be spoken to kindly, or there is an end of me’”, which has the effect of softening down her brother to a certain degree. – What can we infer from this little episode?

Another telling detail is that Dombey says to his sister that he doesn’t “’[…] question your natural devotion to, and regard for, the future of my house.’” What does it tell of Mr. Dombey that he does not use the word “son” here but uses the periphrasis, and what might it say about Mr. Dombey’s future?

There are two conversations in this chapter – one between Paul and his father, another between Paul and Mrs. Pipchin. What do these conversations tell us about Paul? He seems to upset both of his partners in their way of thinking to a certain degree: How could Mr. Dombey and Mrs. Pipchin have profited from these conversations? What may these conversations tell us about the course of the novel?

Mrs. Wickam is a very superstitious woman, and she tells Berinthia about her own niece, Betsey Jane, who reminds her of Paul. She says that when a child, her niece would be as odd as Paul – and that whomever she took a fancy to would sooner or later die. – Does this forebode evil to Florence, who is surely the person Paul loves best in the world?

By the way, we hardly get any news about Florence in this chapter. Why might this be the case? She only comes into the foreground at the end of the chapter, when Paul and she are enjoying their walks along the beach, and Paul shoos off other children because he wants to be alone with his sister – like his father’s wish for no one to step in between himself and his son, in a way. Here, Paul often wonders about what the waves are whispering and what far invisible region lies beyond them. – Does this remind you of a previous chapter?

Life goes on – which might be a bland enough truism, but there are situations, such as watching an episode of Midsomer Murders or sitting in a conference, when you do have to be reminded of it and when it can afford you greatest consolation. Life, then, as they say, goes on, and this also proves true for Little Paul, who is seen through babyhood by Mrs. Chick and Miss Tox, mainly. After the dismissal of Polly Toodle, Paul’s health seems to be in danger, and he grows into a sickly, weak, but at the same time somewhat old-seeming boy. Our narrator sums it up like this,

”The chill of Paul’s christening had struck home, perhaps to some sensitive part of his nature, which could not recover itself in the cold shade of his father; but he was an unfortunate child from that day.”

To support Mrs. Chick and Miss Tox in their endeavours to bring up Paul, Mr. Dombey employs a certain Mrs. Wickam,”who had a surprising natural gift of viewing all subjects in an utterly forlorn and pitiable light”, which might cast another dreary shadow on the Dombey children’s lives. Characteristically, none of the three ladies ever speaks to Mr. Dombey about his son’s frail health, and this, I think, shows how close Pride and Arrogance often come to Failure because it’s clearly Mr. Dombey’s overbearing nature and his stiffness that preclude the sycophantic Mrs. Chick and Miss Tox to broach a subject that might displease him. Instead of enjoying his son’s childhood, Dombey is impatient to see him grow up, to witness his entering into the firm and fulfilling the function of “Son” in the company’s name.

When you consider how people around Mr. Dombey never tell him the truth and how he himself seems to have all priorities wrong – losing out on what makes parenthood so worthwhile and pinning his hopes on a future of his own making instead of valuing the present –, how do you then feel about Dombey? Do you pity him? Despise him? Does he make you feel angry?

When Paul is about five years old, his father by and by suspects that the boy’s health is not as it should be, and Mrs. Chick, in conjunction with Miss Tox, recommend him to send Paul to Brighton, into the house of a Mrs. Pipchin, a respectable widow who has achieved some fame of knowing a lot about how to train children – by giving them whatever they don’t want and depriving them of whatever they would like best. Mr. Dombey, on finding that Mrs. Pipchin’s husband broke his heart over the Peruvian mines, thinks that she is a highly respectable lady and finally consents to the proposal of having Paul sent to Brighton, with Florence for his companion. Mrs. Pipchin’s establishment is, like most of the places Dickens’s heroes have to stay at in their childhood, an extremely bleak place, and there are only two other inmates – young Master Bitherstone and Miss Panckey – as well as Mrs. Pipchin’s niece Berinthia, who is called Berry by the children. Berry seems to be a very nice person but her aunt is a selfish and tyrannous witch, and yet she seems to have taken a fancy to Paul after a strange conversation they had in front of the fire.

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

We might want to regard Mrs. Chick as a sycophant who flatters her brother in order to profit from his vanity. However, when he once speaks gruffly to her, she says, ”’My dear Paul, […] I must be spoken to kindly, or there is an end of me’”, which has the effect of softening down her brother to a certain degree. – What can we infer from this little episode?

Another telling detail is that Dombey says to his sister that he doesn’t “’[…] question your natural devotion to, and regard for, the future of my house.’” What does it tell of Mr. Dombey that he does not use the word “son” here but uses the periphrasis, and what might it say about Mr. Dombey’s future?

There are two conversations in this chapter – one between Paul and his father, another between Paul and Mrs. Pipchin. What do these conversations tell us about Paul? He seems to upset both of his partners in their way of thinking to a certain degree: How could Mr. Dombey and Mrs. Pipchin have profited from these conversations? What may these conversations tell us about the course of the novel?

Mrs. Wickam is a very superstitious woman, and she tells Berinthia about her own niece, Betsey Jane, who reminds her of Paul. She says that when a child, her niece would be as odd as Paul – and that whomever she took a fancy to would sooner or later die. – Does this forebode evil to Florence, who is surely the person Paul loves best in the world?

By the way, we hardly get any news about Florence in this chapter. Why might this be the case? She only comes into the foreground at the end of the chapter, when Paul and she are enjoying their walks along the beach, and Paul shoos off other children because he wants to be alone with his sister – like his father’s wish for no one to step in between himself and his son, in a way. Here, Paul often wonders about what the waves are whispering and what far invisible region lies beyond them. – Does this remind you of a previous chapter?

Chapter 9

Our narration now turns away from the Dombeys and towards our more light-hearted set of characters, but even Solomon Gills and his nephew Walter have to face trouble because years ago Solomon accepted the responsibility for debts incurred by Walter’s father – Walter himself has no idea that his father’s ancient debts are at the bottom of his uncle’s present grief – and now a payment of several hundreds of pounds is due. The broker, Mr. Brogley, an acquaintance of Gills’s, is quite affable and friendly, but he leaves no doubt as to that the money must come down, or else the Midshipman will go down. In his despair, Walter turns to Captain Cuttle and lets him in on their new problem: The captain’s first reaction is to scrape together his belongings and offer them up to Mr. Brogley, but he is soon made to understand that the debts are whales and his offerings are sprats, to borrow an expression from the broker himself. To Walter’s dismay then Captain Cuttle comes up with the idea that if it is a whale of money that is needed, they must ask the munificent Mr. Dombey for a loan to pay Brogley. Walter is sent to the office to inquire about the rich man’s whereabouts, and he returns with the news that, it being Saturday, Dombey has gone to Brighton. Unperturbed in his determination, though, the Captain tells Walter that to Brighton the two of them shall go.

This was my recap, quite crisp in its brevity, and now, for those who like, there are some

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS:

The passing of time in Dombey and Son seems to become an important plot element as far as I can see after the first eight chapters, and Dickens has to face the further difficulty of keeping tabs on different sets of characters who are, as yet, only slightly linked with each other. The beginning of Chapter 9, with Walter’s musings on Florence and her adventure, and with the Captain and Sol’s romantic notions, is a means both of marking the passing of time and of keeping the sets of characters together. – Do you think Dickens’s way of doing this successful? Is his keeping track of time more accurate than in his earlier novels?

Walter has kept the shoes Florence was wearing when he rescued her and that so often came loose from her feet, in his own room. – Seems like a fairy tale, doesn’t it?

What do you think of the mental picture Walter paints of Florence? It has, for example, details like this: “Florence was the most grateful little creature in the world, and it was delightful to see her bright gratitude beaming in her face.“ What do words like these tell us about a) Walter, or maybe even b) the narrator? What they tell us about Florence is clear: She is quite another Little Nell.

Can it be the case that Miss Nipper is entertaining amourous thoughts with regard to Walter? The narrator gives us this:

We should not forget that Victorian England was a rigid class society, and Florence is a rich merchant’s daughter, whereas Walter is an employee of her father’s, and not a very important one at that. His background is probably middle-class, and as the events described in this chapter show, his financial situation is precarious.

For all this, Walter dreams of marrying Florence “in spite of Mr Dombey’s teeth, cravat, and watch-chain“ and to bear her away “to the blue shores of somewhere or other triumphantly.“ - What might the quotation about Mr Dombey’s teeth, cravat and watch-chain imply? What picture as a man is created by mentioning these details, which are quite often mentioned, by the way? – And what about the thought of carrying Florence off to a region overseas?

Mr. Brogley is quite different from a broker or money-lender as they might have appeared in Dickens’s earlier novels: He is not an overly covetous monster, but a friendly and yet adamant man. What does this tell us about Dickens’s development as a writer?

In this chapter, we also make the acquaintance of another comic relief character, Mrs. Mac Stinger, a widow with a handful of children, and a termagant at that. Apparently, Captain Cuttle stands in great awe of her and she seems to keep him as a kind of prisoner because why else would he have to resume to strategem in order to leave his house? – All in all, what do you think of the Mac Stinger episode? Do you find her convincing as a character? Is it in tune with the mood of the chapter, with the novel as such?

What do you think of Cuttle’s plan to ask Mr. Dombey for a loan? Is it a conclusive and sensible thing to come up with in his situation? Or is it an attempt of the narrator’s to establish further links between his characters? – Then there is this, in its irony, telling bit from the conversation between Captain Cuttle and Walter when the Captain explains to the young man the expediency of asking Mr. Dombey for help:

Our narration now turns away from the Dombeys and towards our more light-hearted set of characters, but even Solomon Gills and his nephew Walter have to face trouble because years ago Solomon accepted the responsibility for debts incurred by Walter’s father – Walter himself has no idea that his father’s ancient debts are at the bottom of his uncle’s present grief – and now a payment of several hundreds of pounds is due. The broker, Mr. Brogley, an acquaintance of Gills’s, is quite affable and friendly, but he leaves no doubt as to that the money must come down, or else the Midshipman will go down. In his despair, Walter turns to Captain Cuttle and lets him in on their new problem: The captain’s first reaction is to scrape together his belongings and offer them up to Mr. Brogley, but he is soon made to understand that the debts are whales and his offerings are sprats, to borrow an expression from the broker himself. To Walter’s dismay then Captain Cuttle comes up with the idea that if it is a whale of money that is needed, they must ask the munificent Mr. Dombey for a loan to pay Brogley. Walter is sent to the office to inquire about the rich man’s whereabouts, and he returns with the news that, it being Saturday, Dombey has gone to Brighton. Unperturbed in his determination, though, the Captain tells Walter that to Brighton the two of them shall go.

This was my recap, quite crisp in its brevity, and now, for those who like, there are some

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS:

The passing of time in Dombey and Son seems to become an important plot element as far as I can see after the first eight chapters, and Dickens has to face the further difficulty of keeping tabs on different sets of characters who are, as yet, only slightly linked with each other. The beginning of Chapter 9, with Walter’s musings on Florence and her adventure, and with the Captain and Sol’s romantic notions, is a means both of marking the passing of time and of keeping the sets of characters together. – Do you think Dickens’s way of doing this successful? Is his keeping track of time more accurate than in his earlier novels?

Walter has kept the shoes Florence was wearing when he rescued her and that so often came loose from her feet, in his own room. – Seems like a fairy tale, doesn’t it?

What do you think of the mental picture Walter paints of Florence? It has, for example, details like this: “Florence was the most grateful little creature in the world, and it was delightful to see her bright gratitude beaming in her face.“ What do words like these tell us about a) Walter, or maybe even b) the narrator? What they tell us about Florence is clear: She is quite another Little Nell.

Can it be the case that Miss Nipper is entertaining amourous thoughts with regard to Walter? The narrator gives us this:

“Miss Nipper, on the other hand, rather looked out for these occasions: her sensitive young heart being secretly propitiated by Walter’s good looks, and inclining to the belief that ist sentiments were responded to.“

We should not forget that Victorian England was a rigid class society, and Florence is a rich merchant’s daughter, whereas Walter is an employee of her father’s, and not a very important one at that. His background is probably middle-class, and as the events described in this chapter show, his financial situation is precarious.

For all this, Walter dreams of marrying Florence “in spite of Mr Dombey’s teeth, cravat, and watch-chain“ and to bear her away “to the blue shores of somewhere or other triumphantly.“ - What might the quotation about Mr Dombey’s teeth, cravat and watch-chain imply? What picture as a man is created by mentioning these details, which are quite often mentioned, by the way? – And what about the thought of carrying Florence off to a region overseas?

Mr. Brogley is quite different from a broker or money-lender as they might have appeared in Dickens’s earlier novels: He is not an overly covetous monster, but a friendly and yet adamant man. What does this tell us about Dickens’s development as a writer?

In this chapter, we also make the acquaintance of another comic relief character, Mrs. Mac Stinger, a widow with a handful of children, and a termagant at that. Apparently, Captain Cuttle stands in great awe of her and she seems to keep him as a kind of prisoner because why else would he have to resume to strategem in order to leave his house? – All in all, what do you think of the Mac Stinger episode? Do you find her convincing as a character? Is it in tune with the mood of the chapter, with the novel as such?

What do you think of Cuttle’s plan to ask Mr. Dombey for a loan? Is it a conclusive and sensible thing to come up with in his situation? Or is it an attempt of the narrator’s to establish further links between his characters? – Then there is this, in its irony, telling bit from the conversation between Captain Cuttle and Walter when the Captain explains to the young man the expediency of asking Mr. Dombey for help:

“‘[…] We mustn’t leave a stone unturned – and there’s a stone for you.‘

‘A stone“ – Mr Dombey!‘ faltered Walter.“

Chapter 10

This chapter announces “the Sequel of the Midshipman’s Disaster” but before quelling our curiosity as to the fate of Sol Gills and his shop, we are invited to look through the prawn’s eyes and the opera-glass of Major Bagstock – at little Paul Dombey being mollycoddled by Miss Tox. The Major resents being pushed aside for the Dombey family, and he resolves on making Mr. Dombey’s acquaintance in order to get his foot into that door. When the Major learns that Dombey Father and Dombey Son can be found in Brighton, he suddenly fondly remembers his brother-in-arms Bill Bitherstone and young Master Bitherstone and decides to pay the young boy a visit. He walks young Bitherstone around relentlessly, with no consideration for the child’s wishes, until he happens to run into Mr. Dombey and his children, striking up an acquaintance via poor Paul, whom he had seen at Miss Tox’s place. The Major’s flattery and the deference he pays to Mr. Dombey win that man’s heart very easily and make him think that this officer is an excellent person whose acquaintance is worth fostering.

There are signs of Miss Tox’s entertaining hopes with regard to Mr. Dombey – we may guess that from her behaviour in a conversation with Mrs. Chick – and the Major also senses this, and when he leaves one of the dinners Mr. Dombey invited him to, he shows great derision at Miss Tox’s plans – of course, in the privacy of his own rooms and not in the presence of that refined lady.

The chapter then winds up with a coda referring to the Midshipman again, when Walter and Captain Cuttle make their appearance before Mr. Dombey on the Sunday after that last dinner party. Mr. Dombey treats the two in a very haughty manner, but for all his coldness he lets Paul decide whether Walter shall have the money or not. His motive seems to be to instil the boy with a consciousness of his own power and the power that little Paul will exert one day – because of the money Dombey and Son have at their disposal. It is not the will to help Walter, whom he obviously does not like too much, but rather to teach his son that lesson that makes him forward the money to relieve Uncle Sol. The lesson does not seem to be lost on little Paul for he afterwards struts the room rather cockily. Walter, having received instructions as to how to obtain the money in question, leaves the house with mixed feelings.

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

I don’t really like the Major, but I like the style of speaking Dickens gives him. Just take this sample of one of his monologues:

If Pride and narcissism are topics of this novel and find their most tragic example in the stand-offish Mr. Dombey, can we not say then that old Joey B. of the ever-awake lobster-eye, is the caricature of narcissism, the ridiculous and swaggering, garrulous version of Pride? A Hall-of-Mirrors Version of Mr. Dombey?

The beginning of the chapter also marks the passage of time, but not quite as clearly as Chapter 9. Are we really expected to believe that Major Bagstock has been feeding his resentment at Miss Tox for something like five years? After all, he first spotted Paul as an infant, and now Paul is transferred to Mrs. Pipchin’s excellent establishment.

”’I am the present unworthy representative of that name, Major,” is Mr. Dombey’s reply when the Major asks if he has Mr. Dombey before him. – Clearly, this is mock modesty on Mr. Dombey’s part, but could it not also be an instance of tragic irony?

Major Bagstock and Mr. Dombey becoming chums? Does this appear realistic or probable to you? The Major seems rather uncouth in his gushing, but he also knows how to pull the right levers. How does old Joey B. manage to manipulate Mr. Dombey?

When Miss Tox talks about the Major’s valour to Mrs. Chick, and about his expertise on firearms, she winds up saying, ”’and in the East and West Indies, my love, I really couldn’t undertake to say what he did not do.’” I like that little detail because it seems to imply, of course unbeknownst to Miss Tox herself, that the Major might have committed some atrocious acts in the overseas regions. Just an idea of mine.

Unlike Mr. Scrooge would have done, Mr. Dombey gives Walter a helping hand. And still, all for the wrong reasons. Do you think that Paul will take a leaf out of his father’s book? What might the little boy think of Walter, and of Captain Cuttle, who does not cut a very successful figure in the company present? What do you think of Mr. Dombey’s treatment of Walter and Captain Cuttle?

When Walter’s eyes well up with tears of thankfulness, so do Florence’s, and Mr. Dombey sees that, although he appears to be looking at Walter only. – What effect might Florence’s reaction have on Dombey?

”’Girls,’ said Mr Dombey, ‘have nothing to do with Dombey and Son. […]’” Any comments?

This chapter announces “the Sequel of the Midshipman’s Disaster” but before quelling our curiosity as to the fate of Sol Gills and his shop, we are invited to look through the prawn’s eyes and the opera-glass of Major Bagstock – at little Paul Dombey being mollycoddled by Miss Tox. The Major resents being pushed aside for the Dombey family, and he resolves on making Mr. Dombey’s acquaintance in order to get his foot into that door. When the Major learns that Dombey Father and Dombey Son can be found in Brighton, he suddenly fondly remembers his brother-in-arms Bill Bitherstone and young Master Bitherstone and decides to pay the young boy a visit. He walks young Bitherstone around relentlessly, with no consideration for the child’s wishes, until he happens to run into Mr. Dombey and his children, striking up an acquaintance via poor Paul, whom he had seen at Miss Tox’s place. The Major’s flattery and the deference he pays to Mr. Dombey win that man’s heart very easily and make him think that this officer is an excellent person whose acquaintance is worth fostering.

There are signs of Miss Tox’s entertaining hopes with regard to Mr. Dombey – we may guess that from her behaviour in a conversation with Mrs. Chick – and the Major also senses this, and when he leaves one of the dinners Mr. Dombey invited him to, he shows great derision at Miss Tox’s plans – of course, in the privacy of his own rooms and not in the presence of that refined lady.

The chapter then winds up with a coda referring to the Midshipman again, when Walter and Captain Cuttle make their appearance before Mr. Dombey on the Sunday after that last dinner party. Mr. Dombey treats the two in a very haughty manner, but for all his coldness he lets Paul decide whether Walter shall have the money or not. His motive seems to be to instil the boy with a consciousness of his own power and the power that little Paul will exert one day – because of the money Dombey and Son have at their disposal. It is not the will to help Walter, whom he obviously does not like too much, but rather to teach his son that lesson that makes him forward the money to relieve Uncle Sol. The lesson does not seem to be lost on little Paul for he afterwards struts the room rather cockily. Walter, having received instructions as to how to obtain the money in question, leaves the house with mixed feelings.

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

I don’t really like the Major, but I like the style of speaking Dickens gives him. Just take this sample of one of his monologues:

”’Would you, Ma’am, would you!’ said the Major, straining with vindictiveness, and swelling every vein in his head. ‘Would you give Joey B. the go-by, Ma’am? Not yet, Ma’am, not yet! Damme, not yet, Sir. Joe is awake, Ma’am. Bagstock is alive, Sir. J.B. knows a move or two, Ma’am. Josh has his weather-eye open, Sir. You’ll find him tough, Ma’am. Tough, Sir, tough is Joseph. Tough and de-vilish sly!’”

If Pride and narcissism are topics of this novel and find their most tragic example in the stand-offish Mr. Dombey, can we not say then that old Joey B. of the ever-awake lobster-eye, is the caricature of narcissism, the ridiculous and swaggering, garrulous version of Pride? A Hall-of-Mirrors Version of Mr. Dombey?

The beginning of the chapter also marks the passage of time, but not quite as clearly as Chapter 9. Are we really expected to believe that Major Bagstock has been feeding his resentment at Miss Tox for something like five years? After all, he first spotted Paul as an infant, and now Paul is transferred to Mrs. Pipchin’s excellent establishment.

”’I am the present unworthy representative of that name, Major,” is Mr. Dombey’s reply when the Major asks if he has Mr. Dombey before him. – Clearly, this is mock modesty on Mr. Dombey’s part, but could it not also be an instance of tragic irony?

Major Bagstock and Mr. Dombey becoming chums? Does this appear realistic or probable to you? The Major seems rather uncouth in his gushing, but he also knows how to pull the right levers. How does old Joey B. manage to manipulate Mr. Dombey?

When Miss Tox talks about the Major’s valour to Mrs. Chick, and about his expertise on firearms, she winds up saying, ”’and in the East and West Indies, my love, I really couldn’t undertake to say what he did not do.’” I like that little detail because it seems to imply, of course unbeknownst to Miss Tox herself, that the Major might have committed some atrocious acts in the overseas regions. Just an idea of mine.

Unlike Mr. Scrooge would have done, Mr. Dombey gives Walter a helping hand. And still, all for the wrong reasons. Do you think that Paul will take a leaf out of his father’s book? What might the little boy think of Walter, and of Captain Cuttle, who does not cut a very successful figure in the company present? What do you think of Mr. Dombey’s treatment of Walter and Captain Cuttle?

When Walter’s eyes well up with tears of thankfulness, so do Florence’s, and Mr. Dombey sees that, although he appears to be looking at Walter only. – What effect might Florence’s reaction have on Dombey?

”’Girls,’ said Mr Dombey, ‘have nothing to do with Dombey and Son. […]’” Any comments?

Chapter 8: Poor Paul. The conversation between him and his dad was heart-breaking, yet thought-provoking.

Chapter 8: Poor Paul. The conversation between him and his dad was heart-breaking, yet thought-provoking."Papa, what's money?...Why didn't money save me my Mama?"

Heavy stuff. I'm glad the father was somewhat open to talking and didn't shut Paul down completely. I feel sorry for Paul's losses, but love his inquisitive nature, because it shows he's not totally weak.

I also find it fascinating how anti-money/anti-capitalist Dickens was. His stories always have the message that money can't buy love, or happiness, or integrity.

Alissa wrote: "Chapter 8: Poor Paul. The conversation between him and his dad was heart-breaking, yet thought-provoking.

"Papa, what's money?...Why didn't money save me my Mama?"

Heavy stuff. I'm glad the fathe..."

Hi Alissa

Yes, there is much D&S that offers greater depth than his previous novels. As you note, Mr Dombey is a perfect example. He is a complex man, and we are only 10 chapters into the novel. So far, as much as I dislike him, I think he is struggling with a legacy he may well not know how to handle properly.

And there is much more to come, and many characters to intrigue us.

"Papa, what's money?...Why didn't money save me my Mama?"

Heavy stuff. I'm glad the fathe..."

Hi Alissa

Yes, there is much D&S that offers greater depth than his previous novels. As you note, Mr Dombey is a perfect example. He is a complex man, and we are only 10 chapters into the novel. So far, as much as I dislike him, I think he is struggling with a legacy he may well not know how to handle properly.

And there is much more to come, and many characters to intrigue us.

The talk about money and why it couldn't save little Paul's mom is one that often happens in real life - but then when talking about God. Perhaps Dickens also wanted to show that God and faith (not religion, Dombey clearly was religious, for little Paul was babtized) were replaced by money in the Dombey household, like was (is) the case all over the world - and that money somehow is their god now. It is clear to me that Dickens does not go after money itself being bad, but he points at the idolization of it.

Paul, the poor little guy. Shipped off like that - at least with Florence with him, the only person who remained and loved him all of his life. He does seem eager to please and help Walter. I got the idea he met Walter before and liked him, and that it was more because of that than out of pity, but I can be wrong. I do think it shows little Paul still has a big heart though, wanting to help when he can. Also, his father gives him a snippet of attention and a moment of importance to him (well, the firm, but never mind) that the little Paul might not hve experienced first hand yet.

Paul, the poor little guy. Shipped off like that - at least with Florence with him, the only person who remained and loved him all of his life. He does seem eager to please and help Walter. I got the idea he met Walter before and liked him, and that it was more because of that than out of pity, but I can be wrong. I do think it shows little Paul still has a big heart though, wanting to help when he can. Also, his father gives him a snippet of attention and a moment of importance to him (well, the firm, but never mind) that the little Paul might not hve experienced first hand yet.

Tristram wrote: "Hello Curiosities,

Life goes on – which might be a bland enough truism, but there are situations, such as watching an episode of Midsomer Murders or sitting in a conference, when you do have to b..."

When Mr Dombey says he does not question his sister’s devotion to the “house” I think there is a double meaning. I read the word “house” as referring to both his home and the house of Dombey as the business. Mr Dombey is unable to separate his personal and his professional life. Until he does, I fear for the well-being of Florence and Paul. To what extent are his children commodities to be used or to be rejected?

Life goes on – which might be a bland enough truism, but there are situations, such as watching an episode of Midsomer Murders or sitting in a conference, when you do have to b..."

When Mr Dombey says he does not question his sister’s devotion to the “house” I think there is a double meaning. I read the word “house” as referring to both his home and the house of Dombey as the business. Mr Dombey is unable to separate his personal and his professional life. Until he does, I fear for the well-being of Florence and Paul. To what extent are his children commodities to be used or to be rejected?

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 9

Our narration now turns away from the Dombeys and towards our more light-hearted set of characters, but even Solomon Gills and his nephew Walter have to face trouble because years ago S..."

Tristram

Ah yes. Time, fairy tales, and the rigid class structure. These three elements of the novel do continue to appear very frequently and I think we need to pay attention to them very closely.

It seems to me that Dickens is much more careful to track time in different ways. First, I cannot recall any of his earlier novels where he is so precise in giving people’s ages which then gives his readers a solid footing upon which to understand not only what is happening in the novel but how long each event is separated from others. Coupled with that is the constant reference to Dombey’s watch and especially the watch chain. Is Dickens suggesting some other suggestive link between time and chains? As we go through the novel I think it might be interesting to take a close look at Browne’s illustrations. If my memory serves me correctly, clocks are part of many illustrations.

Poor Nell, or is it now poor Florence? There are already clear similarities between these two delightful young ladies ;-). As for the presence of a fairy tale motif I do feel its presence. A handsome young man with a shoe in search of a foot cannot be mere chance.

The class structure is alive and well once again. This time, however, at least this far into the novel, I feel Dickens is being far more subtle and creative in the way he presents it.

Our narration now turns away from the Dombeys and towards our more light-hearted set of characters, but even Solomon Gills and his nephew Walter have to face trouble because years ago S..."

Tristram

Ah yes. Time, fairy tales, and the rigid class structure. These three elements of the novel do continue to appear very frequently and I think we need to pay attention to them very closely.

It seems to me that Dickens is much more careful to track time in different ways. First, I cannot recall any of his earlier novels where he is so precise in giving people’s ages which then gives his readers a solid footing upon which to understand not only what is happening in the novel but how long each event is separated from others. Coupled with that is the constant reference to Dombey’s watch and especially the watch chain. Is Dickens suggesting some other suggestive link between time and chains? As we go through the novel I think it might be interesting to take a close look at Browne’s illustrations. If my memory serves me correctly, clocks are part of many illustrations.

Poor Nell, or is it now poor Florence? There are already clear similarities between these two delightful young ladies ;-). As for the presence of a fairy tale motif I do feel its presence. A handsome young man with a shoe in search of a foot cannot be mere chance.

The class structure is alive and well once again. This time, however, at least this far into the novel, I feel Dickens is being far more subtle and creative in the way he presents it.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 10

This chapter announces “the Sequel of the Midshipman’s Disaster” but before quelling our curiosity as to the fate of Sol Gills and his shop, we are invited to look through the prawn’s e..."

I very much liked your comparison of Dombey’s cold sterile pride to that of Bagstock’s “hall-of-mirrors” burbling, blundering, and overtly swelling and exploding nature and character. They do reflect each other and play off each other wonderfully well. Pride comes in many shapes and forms. They are both wonderful creations.

Paul’s first lesson in the power of money is striking. It does raise the question of who is worse. Is it Scrooge who will not part with a penny unless he can extract blood from it or is it Dombey who uses money as a far more subtle but equally dangerous method of control?

This chapter announces “the Sequel of the Midshipman’s Disaster” but before quelling our curiosity as to the fate of Sol Gills and his shop, we are invited to look through the prawn’s e..."

I very much liked your comparison of Dombey’s cold sterile pride to that of Bagstock’s “hall-of-mirrors” burbling, blundering, and overtly swelling and exploding nature and character. They do reflect each other and play off each other wonderfully well. Pride comes in many shapes and forms. They are both wonderful creations.

Paul’s first lesson in the power of money is striking. It does raise the question of who is worse. Is it Scrooge who will not part with a penny unless he can extract blood from it or is it Dombey who uses money as a far more subtle but equally dangerous method of control?

Tristram, I have never once thought of anything you said as ambiguous since I have no clue what that means, and as to why your recaps are long, it's because you talk a lot, even more than I do, and you probably sound ambiguous the entire time. :-)

Kim wrote: "Tristram, I have never once thought of anything you said as ambiguous since I have no clue what that means, and as to why your recaps are long, it's because you talk a lot, even more than I do, and..."

Oh dear, Kim, if you knew some people from my work you'd know their complaints, at least from some of them, at how unambiguous many things I say are :-)

Oh dear, Kim, if you knew some people from my work you'd know their complaints, at least from some of them, at how unambiguous many things I say are :-)

am·big·u·ous

open to more than one interpretation; having a double meaning.

"ambiguous phrases"

unclear or inexact because a choice between alternatives has not been made.

"the election result was ambiguous"

open to more than one interpretation; having a double meaning.

"ambiguous phrases"

unclear or inexact because a choice between alternatives has not been made.

"the election result was ambiguous"

un·am·big·u·ous

not open to more than one interpretation.

"instructions should be unambiguous"

I wonder how long I'll remember that.

not open to more than one interpretation.

"instructions should be unambiguous"

I wonder how long I'll remember that.

Tristram wrote: "Oh dear, Kim, if you knew some people from my work you'd know their complaints, at least from some of them, at how unambiguous many things I say are :-)"

I would think they would complain more if they couldn't figure out what you're talking about than if they are absolutely sure.

I would think they would complain more if they couldn't figure out what you're talking about than if they are absolutely sure.

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 10

This chapter announces “the Sequel of the Midshipman’s Disaster” but before quelling our curiosity as to the fate of Sol Gills and his shop, we are invited to look thro..."

Yes, Peter, I can confess here that Major Bagstock, though he is absolutely horrid, is one of my favourite characters in the novel. It's so much fun to read his cascades of words aloud. He's not as good as Mrs. Gamp, of course, but still, he's, as they say, quite a character.

As to Mr. Dombey's lesson about money to Paul: It is chilling how Dombey uses an actually good thing, generosity and helpfulness, to teach a cold lesson of pride and condescension, and of materialism. He stresses that Walter has come all the long way to beg for something he does not have but needs to save his uncle, and how Paul can fulfil this important wish. This tells Paul how powerful money is after all (even though it could not keep his mother alive), and how much power resides in the decision to help or not to help. By asking little Paul whether he wants to give the money to Walter, he implies that this decision imparts power - the power to let live or to make die.

Dickens presents this scene - in a way a corresponding scene to the one in which Paul inquires about the power of money when sitting with his father - in an unforgettable way. And in a chilling one, if you ask me.

This chapter announces “the Sequel of the Midshipman’s Disaster” but before quelling our curiosity as to the fate of Sol Gills and his shop, we are invited to look thro..."

Yes, Peter, I can confess here that Major Bagstock, though he is absolutely horrid, is one of my favourite characters in the novel. It's so much fun to read his cascades of words aloud. He's not as good as Mrs. Gamp, of course, but still, he's, as they say, quite a character.

As to Mr. Dombey's lesson about money to Paul: It is chilling how Dombey uses an actually good thing, generosity and helpfulness, to teach a cold lesson of pride and condescension, and of materialism. He stresses that Walter has come all the long way to beg for something he does not have but needs to save his uncle, and how Paul can fulfil this important wish. This tells Paul how powerful money is after all (even though it could not keep his mother alive), and how much power resides in the decision to help or not to help. By asking little Paul whether he wants to give the money to Walter, he implies that this decision imparts power - the power to let live or to make die.

Dickens presents this scene - in a way a corresponding scene to the one in which Paul inquires about the power of money when sitting with his father - in an unforgettable way. And in a chilling one, if you ask me.

Alissa wrote: "I'm glad the father was somewhat open to talking and didn't shut Paul down completely."

Alissa,

I was quite moved by the awkward display of love and interest Dombey the Father displays for his son here. In the course of this conversation, Dombey is unmasked in two ways: One, it should become clear that his reliance on money and wealth and station is maybe not well-placed. Two, it shows that in his heart of hearts, this granite man, this whited sepulchre of arrogance, is a human being with feelings like love - only he doesn't know how to deal with them, how to let them come to the surface.

Alissa,

I was quite moved by the awkward display of love and interest Dombey the Father displays for his son here. In the course of this conversation, Dombey is unmasked in two ways: One, it should become clear that his reliance on money and wealth and station is maybe not well-placed. Two, it shows that in his heart of hearts, this granite man, this whited sepulchre of arrogance, is a human being with feelings like love - only he doesn't know how to deal with them, how to let them come to the surface.

Peter wrote: "Poor Nell, or is it now poor Florence? There are already clear similarities between these two delightful young ladies ;-)...."

Peter wrote: "Poor Nell, or is it now poor Florence? There are already clear similarities between these two delightful young ladies ;-)...."I was thinking more that Walter is like Nell, as the dependent of an improvident elder who has to get himself into trouble--in this case, go begging to his boss, when he clearly feels uncomfortable in doing so--in order to bail the family out. Although Walter, being male and with a job, has more resources than Nell, he's also got a different kind of dignity and status to lose, and he just lost it. Poor guy.

Dombey is such a pig to sweep away all of Cuttle's treasures like that.

Tristram wrote: "it shows that in his heart of hearts, this granite man, this whited sepulchre of arrogance, is a human being with feelings like love - only he doesn't know how to deal with them, how to let them come to the surface..."

Tristram wrote: "it shows that in his heart of hearts, this granite man, this whited sepulchre of arrogance, is a human being with feelings like love - only he doesn't know how to deal with them, how to let them come to the surface..."Is this love, or is this corruption? Clearly Dombey will do a thing for Paul that he doesn't want to do, but it's in the interest of winning him over to the love of status, which is kind of the devil in this family.

Paul is already kind of an arrogant little thing, but he's following Florence's lead on this one, not his father's, and I wouldn't be surprised to see this action backfire on Mr. Dombey. What if Paul, like Scrooge, has just figured out what money is actually for--power in the sense of accomplishing a thing, not of being powerful?

After working my way though Oliver and Nickleby and Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge and maybe a third of Chuzzlewit--I am so delighted to feel at this point that this book is SO GOOD. The way the children and their elders are characterized and lined up and mutually entangled at the end of this installment--I am sympathizing with all three kids in so many ways and itching to find out what happens as they mature and the conflicts set into motion now start to find expression.

After working my way though Oliver and Nickleby and Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge and maybe a third of Chuzzlewit--I am so delighted to feel at this point that this book is SO GOOD. The way the children and their elders are characterized and lined up and mutually entangled at the end of this installment--I am sympathizing with all three kids in so many ways and itching to find out what happens as they mature and the conflicts set into motion now start to find expression.

Dombey and Son

Chapter 8

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

Thus Paul grew to be nearly five years old. He was a pretty little fellow; though there was something wan and wistful in his small face, that gave occasion to many significant shakes of Mrs. Wickam’s head, and many long-drawn inspirations of Mrs. Wickam’s breath. His temper gave abundant promise of being imperious in after-life; and he had as hopeful an apprehension of his own importance, and the rightful subservience of all other things and persons to it, as heart could desire. He was childish and sportive enough at times, and not of a sullen disposition; but he had a strange, old-fashioned, thoughtful way, at other times, of sitting brooding in his miniature arm-chair, when he looked (and talked) like one of those terrible little Beings in the Fairy tales, who, at a hundred and fifty or two hundred years of age, fantastically represent the children for whom they have been substituted. He would frequently be stricken with this precocious mood upstairs in the nursery; and would sometimes lapse into it suddenly, exclaiming that he was tired: even while playing with Florence, or driving Miss Tox in single harness. But at no time did he fall into it so surely, as when, his little chair being carried down into his father’s room, he sat there with him after dinner, by the fire. They were the strangest pair at such a time that ever firelight shone upon. Mr Dombey so erect and solemn, gazing at the glare; his little image, with an old, old face, peering into the red perspective with the fixed and rapt attention of a sage. Mr Dombey entertaining complicated worldly schemes and plans; the little image entertaining Heaven knows what wild fancies, half-formed thoughts, and wandering speculations. Mr Dombey stiff with starch and arrogance; the little image by inheritance, and in unconscious imitation. The two so very much alike, and yet so monstrously contrasted.

Commentary:

Although the original series of steel-engravings by Phiz has several likenesses of Paul Dombey, most notably Paul and Mrs. Pipchin (Chapter 8), the same moment that Furniss has realised occurs in the Household Edition volume, in which the boy and his father are sitting in front of the fire after dinner in the same relationship to one another. Furniss renders Dombey a statue on a throne, in contrast to the puzzled and inquisitive little boy sitting beside his uncommunicative, unemotional father. It seems likely, then, that Furniss, having studied the earlier illustrations, settled upon this textual and narrative-pictorial moment as the one most appropriate for preparing the reader for the novel's characters and situations.

Paul and Mrs. Pipchin

Chapter 8

Phiz

original sketch

In color obviously

Text Illustrated:

At this exemplary old lady, Paul would sit staring in his little arm-chair by the fire, for any length of time. He never seemed to know what weariness was, when he was looking fixedly at Mrs Pipchin. He was not fond of her; he was not afraid of her; but in those old, old moods of his, she seemed to have a grotesque attraction for him. There he would sit, looking at her, and warming his hands, and looking at her, until he sometimes quite confounded Mrs Pipchin, Ogress as she was. Once she asked him, when they were alone, what he was thinking about.

‘You,’ said Paul, without the least reserve.

‘And what are you thinking about me?’ asked Mrs Pipchin.

‘I’m thinking how old you must be,’ said Paul.

‘You mustn’t say such things as that, young gentleman,’ returned the dame. ‘That’ll never do.’

‘Why not?’ asked Paul.

‘Because it’s not polite,’ said Mrs Pipchin, snappishly.

‘Not polite?’ said Paul.

‘No.’

‘It’s not polite,’ said Paul, innocently, ‘to eat all the mutton chops and toast’, Wickam says.

‘Wickam,’ retorted Mrs Pipchin, colouring, ‘is a wicked, impudent, bold-faced hussy.’

‘What’s that?’ inquired Paul.

‘Never you mind, Sir,’ retorted Mrs Pipchin. ‘Remember the story of the little boy that was gored to death by a mad bull for asking questions.’

‘If the bull was mad,’ said Paul, ‘how did he know that the boy had asked questions? Nobody can go and whisper secrets to a mad bull. I don’t believe that story.’

‘You don’t believe it, Sir?’ repeated Mrs Pipchin, amazed.

‘No,’ said Paul.

‘Not if it should happen to have been a tame bull, you little Infidel?’ said Mrs Pipchin.

As Paul had not considered the subject in that light, and had founded his conclusions on the alleged lunacy of the bull, he allowed himself to be put down for the present. But he sat turning it over in his mind, with such an obvious intention of fixing Mrs Pipchin presently, that even that hardy old lady deemed it prudent to retreat until he should have forgotten the subject.

From that time, Mrs Pipchin appeared to have something of the same odd kind of attraction towards Paul, as Paul had towards her. She would make him move his chair to her side of the fire, instead of sitting opposite; and there he would remain in a nook between Mrs Pipchin and the fender, with all the light of his little face absorbed into the black bombazeen drapery, studying every line and wrinkle of her countenance, and peering at the hard grey eye, until Mrs Pipchin was sometimes fain to shut it, on pretence of dozing. Mrs Pipchin had an old black cat, who generally lay coiled upon the centre foot of the fender, purring egotistically, and winking at the fire until the contracted pupils of his eyes were like two notes of admiration. The good old lady might have been—not to record it disrespectfully—a witch, and Paul and the cat her two familiars, as they all sat by the fire together. It would have been quite in keeping with the appearance of the party if they had all sprung up the chimney in a high wind one night, and never been heard of any more.

This, however, never came to pass. The cat, and Paul, and Mrs Pipchin, were constantly to be found in their usual places after dark; and Paul, eschewing the companionship of Master Bitherstone, went on studying Mrs Pipchin, and the cat, and the fire, night after night, as if they were a book of necromancy, in three volumes.

Commentary:

The tendency of the Dombey influence to blight and wither is illustrated in the first of several plates dealing with Paul's childhood, "Paul and Mrs. Pipchin", perhaps the most celebrated etching in the novel, if only because Dickens is on record as having been violently disappointed with it. Dickens seems to have objected because Paul is sitting in the wrong kind of chair, and Mrs. Pipchin should be stooped and much older, the whole atmosphere is not uncanny enough, the witchlike and magical qualities of the text insufficiently realized. Yet Browne was presented with special problems as an interpreter. The description of Mrs. Pipchin is, if taken straight, quite extravagant: she is a "marvelously ill-favored, ill-conditioned old lady, of a stooping figure, with a mottled face, like bad marble, a hook nose, and a hard grey eye, that looked as if it might have been hammered at on an anvil without sustaining any injury"; she is an "ogress and childqueller" who likes hairy, sticky, creeping plants, and whose 11 waters of gladness and milk of human kindness had been pumped out dry". The description of the scene depicted in the fifth plate concludes that "the good old lady might have been — not to record it disrespectfully — a witch, and Paul and the cat her two familiars, as they all sat by the fire together". Dickens may have been upset because the plate (whose drawings he evidently did not get to see) failed to match his own inner vision. Forster remarks that Dickens "felt the disappointment more keenly, because the conception of the grim old boarding-house keeper had taken back his thoughts to the miseries of his own child-life, and made her, as her prototype in verity was, a part of the terrible reality". Browne can certainly be faulted for not getting the chair right, but one must ask how an illustrator is to deal with semifacetious suggestions of the uncanny and supernatural when he is illustrating a purportedly realistic novel. Surely he is faced with the problem of embodying a sense of the author's description without suddenly shifting his style into a more fantastic one.

The drawings for "Paul and Mrs. Pipchin" give evidence that Browne worked hard to get this illustration right. The initial sketch is a free ink drawing, with the figures facing the same way as in the printed etching; the number of comparable drawings extant is small enough so it seems reasonable to assume that when Phiz did make such a sketch he was especially concerned about the left-right arrangement, as in the vignette title for Martin Chuzzlewit. In this case a look at the working drawing, reversed as usual, reveals that the placement of the figures makes some difference. With Paul on the left, as in the etching, he catches our attention first, and only then do we notice Mrs. Pipchin; with the figures reversed, Mrs. Pipchin dominates: looking from left to right we see first her creepy plants, then her looming figure, and only third little Paul. The printed version and the initial drawing cause us to see Mrs. Pipchin more through Paul's eyes; the author's description of her then may be understood to take some of its fairy tale quality from that viewpoint. Browne seems to me to have been as successful as possible in his attempt to combine a realistic with a fantastic atmosphere, and it should be mentioned that Mrs. Pipchin's expression is a good deal more frightening and witchlike in Steel B than in Steel A, though it is the latter which most resembles the working drawing — suggesting that Browne was still experimenting with La Pipchin down to the last minute.

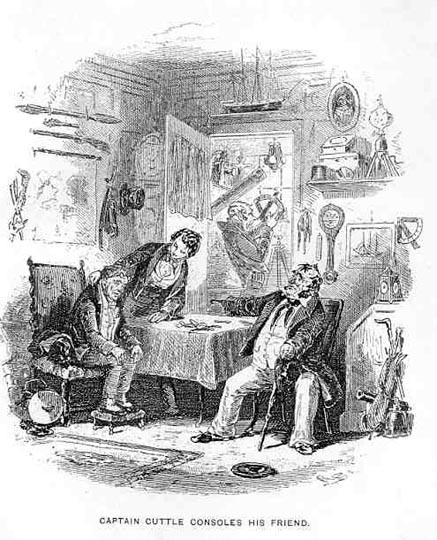

The companion etching, "Captain Cuttle consoles his friend", takes us from the harshness of Paul's Brighton environment to the protections of the Wooden Midshipman. Visually, the parallel is between Paul sitting in his chair looking up apprehensively at the old "child-queller," and Sol Gills sitting in his chair being comforted by his nephew and Captain Cuttle. although the basic point may be one of contrast, both Paul and Sol are "old-fashioned" in slightly different senses: Paul, we discover, seems precocious because he is so close to and intuitively so aware of death; Mr. Gills is old-fashioned in the present sense of being, as he says, behind the times. In both there are overtones of enfeeblement and decline.

From "The Life of Charles Dickens" by John Forster:

The first chapter of it was sent me only four days later (nearly half the entire part, so freely his fancy was now flowing and overflowing), with intimation for the artist:

"The best subject for Browne will be at Mrs. Pipchin's; and if he liked to do a quiet odd thing, Paul, Mrs. Pipchin, and the Cat, by the fire, would be very good for the story. I earnestly hope he will think it worth a little extra care. The second subject, in case he shouldn't take a second from that same chapter, I will shortly describe as soon as I have it clearly (to-morrow or next day), and send it to you by post."

The result was not satisfactory; but as the artist more than redeemed it in the later course of the tale, and the present disappointment was mainly the incentive to that better success, the mention of the failure here will be excused for what it illustrates of Dickens himself:

"I am really distressed by the illustration of Mrs. Pipchin and Paul. It is so frightfully and wildly wide of the mark. Good Heaven! in the commonest and most literal construction of the text, it is all wrong. She is described as an old lady, and Paul's 'miniature arm-chair' is mentioned more than once. He ought to be sitting in a little arm-chair down in the corner of the fireplace, staring up at her. I can't say what pain and vexation it is to be so utterly misrepresented. I would cheerfully have given a hundred pounds to have kept this illustration out of the book. He never could have got that idea of Mrs. Pipchin if he had attended to the text. Indeed I think he does better without the text; for then the notion is made easy to him in short description, and he can't help taking it in."

He felt the disappointment more keenly, because the conception of the grim old boarding-house keeper had taken back his thoughts to the miseries of his own child-life, and made her, as her prototype in verity was, a part of the terrible reality. I had forgotten, until I again read this letter of the 4th of November 1846, that he thus early proposed to tell me that story of his boyish sufferings which a question from myself, of some months later date, so fully elicited. He was now hastening on with the close of his third number, to be ready for departure to Paris.

". . . I hope to finish the number by next Tuesday or Wednesday. It is hard writing under these bird-of-passage circumstances, but I have no reason to complain, God knows, having come to no knot yet. . . . I hope you will like Mrs. Pipchin's establishment. It is from the life, and I was there—I don't suppose I was eight years old; but I remember it all as well, and certainly understood it as well, as I do now. We should be devilish sharp in what we do to children. I thought of that passage in my small life, at Geneva. Shall I leave you my life in MS. when I die? There are some things in it that would touch you very much, and that might go on the same shelf with the first volume of Holcroft's."

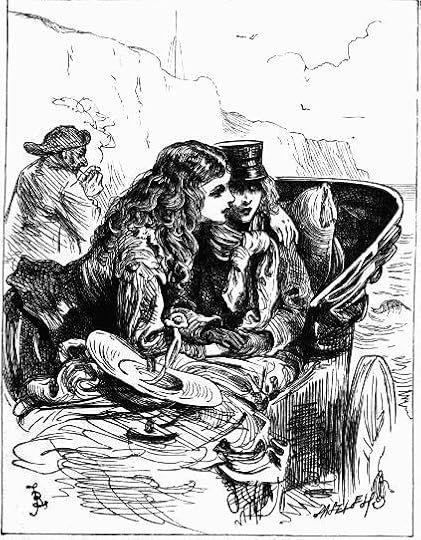

Listening to the Sea

Chapter 8

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

But as Paul himself was no stronger at the expiration of that time than he had been on his first arrival, though he looked much healthier in the face, a little carriage was got for him, in which he could lie at his ease, with an alphabet and other elementary works of reference, and be wheeled down to the sea-side. Consistent in his odd tastes, the child set aside a ruddy-faced lad who was proposed as the drawer of this carriage, and selected, instead, his grandfather—a weazen, old, crab-faced man, in a suit of battered oilskin, who had got tough and stringy from long pickling in salt water, and who smelt like a weedy sea-beach when the tide is out.

With this notable attendant to pull him along, and Florence always walking by his side, and the despondent Wickam bringing up the rear, he went down to the margin of the ocean every day; and there he would sit or lie in his carriage for hours together: never so distressed as by the company of children—Florence alone excepted, always.

‘Go away, if you please,’ he would say to any child who came to bear him company. ‘Thank you, but I don’t want you.’

Some small voice, near his ear, would ask him how he was, perhaps.

‘I am very well, I thank you,’ he would answer. ‘But you had better go and play, if you please.’

Then he would turn his head, and watch the child away, and say to Florence, ‘We don’t want any others, do we? Kiss me, Floy.’

He had even a dislike, at such times, to the company of Wickam, and was well pleased when she strolled away, as she generally did, to pick up shells and acquaintances. His favourite spot was quite a lonely one, far away from most loungers; and with Florence sitting by his side at work, or reading to him, or talking to him, and the wind blowing on his face, and the water coming up among the wheels of his bed, he wanted nothing more.

‘Floy,’ he said one day, ‘where’s India, where that boy’s friends live?’

‘Oh, it’s a long, long distance off,’ said Florence, raising her eyes from her work.

‘Weeks off?’ asked Paul.

‘Yes dear. Many weeks’ journey, night and day.’

‘If you were in India, Floy,’ said Paul, after being silent for a minute, ‘I should—what is it that Mama did? I forget.’

‘Loved me!’ answered Florence.

‘No, no. Don’t I love you now, Floy? What is it?—Died. If you were in India, I should die, Floy.’

She hurriedly put her work aside, and laid her head down on his pillow, caressing him. And so would she, she said, if he were there. He would be better soon.

‘Oh! I am a great deal better now!’ he answered. ‘I don’t mean that. I mean that I should die of being so sorry and so lonely, Floy!’

Another time, in the same place, he fell asleep, and slept quietly for a long time. Awaking suddenly, he listened, started up, and sat listening.

Florence asked him what he thought he heard.

‘I want to know what it says,’ he answered, looking steadily in her face. ‘The sea’ Floy, what is it that it keeps on saying?’

She told him that it was only the noise of the rolling waves.

‘Yes, yes,’ he said. ‘But I know that they are always saying something. Always the same thing. What place is over there?’ He rose up, looking eagerly at the horizon.

She told him that there was another country opposite, but he said he didn’t mean that: he meant further away—farther away!

Very often afterwards, in the midst of their talk, he would break off, to try to understand what it was that the waves were always saying; and would rise up in his couch to look towards that invisible region, far away.

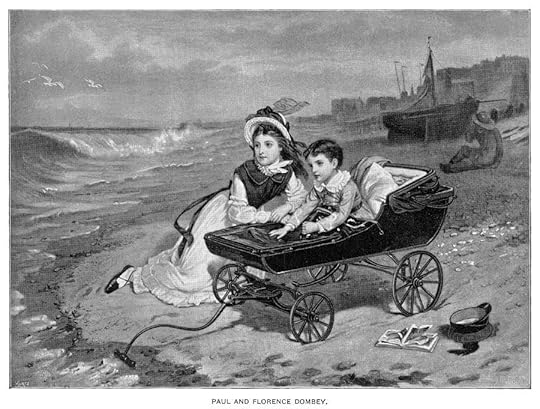

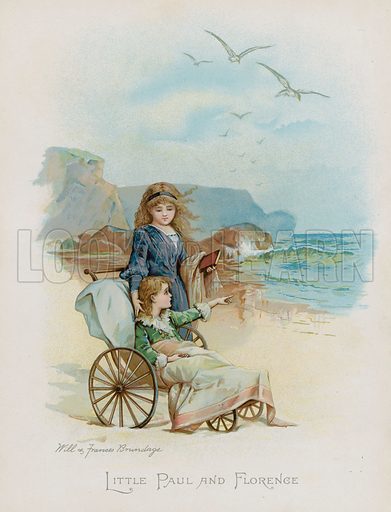

Be prepared to spend a long time at the sea:

Unknown artist

Paul and Flo Dombey

M. F. or E. M. Taylor

Jessie Wilcox Smith

Charles Edmond Brock

Unknown artist

Paul and Flo Dombey

M. F. or E. M. Taylor

Jessie Wilcox Smith

Charles Edmond Brock

"The sea, Floy, what is it that it keeps saying?"

Illustration for Pictures from Dickens 1890

John Henry Frederick Bacon

Frances Brundage

From Children's Stories from Dickens 1890

Captain Cuttle consoles his friend

Chapter 9

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Gills!’ said the Captain, hurrying into the back parlour, and taking him by the hand quite tenderly. ‘Lay your head well to the wind, and we’ll fight through it. All you’ve got to do,’ said the Captain, with the solemnity of a man who was delivering himself of one of the most precious practical tenets ever discovered by human wisdom, ‘is to lay your head well to the wind, and we’ll fight through it!’

Old Sol returned the pressure of his hand, and thanked him.

Captain Cuttle, then, with a gravity suitable to the nature of the occasion, put down upon the table the two tea-spoons and the sugar-tongs, the silver watch, and the ready money; and asked Mr Brogley, the broker, what the damage was.

‘Come! What do you make of it?’ said Captain Cuttle.

‘Why, Lord help you!’ returned the broker; ‘you don’t suppose that property’s of any use, do you?’

‘Why not?’ inquired the Captain.

‘Why? The amount’s three hundred and seventy, odd,’ replied the broker.

‘Never mind,’ returned the Captain, though he was evidently dismayed by the figures: ‘all’s fish that comes to your net, I suppose?’

‘Certainly,’ said Mr Brogley. ‘But sprats ain’t whales, you know.’

The philosophy of this observation seemed to strike the Captain. He ruminated for a minute; eyeing the broker, meanwhile, as a deep genius; and then called the Instrument-maker aside.

‘Gills,’ said Captain Cuttle, ‘what’s the bearings of this business? Who’s the creditor?’

‘Hush!’ returned the old man. ‘Come away. Don’t speak before Wally. It’s a matter of security for Wally’s father—an old bond. I’ve paid a good deal of it, Ned, but the times are so bad with me that I can’t do more just now. I’ve foreseen it, but I couldn’t help it. Not a word before Wally, for all the world.’

‘You’ve got some money, haven’t you?’ whispered the Captain.

‘Yes, yes—oh yes—I’ve got some,’ returned old Sol, first putting his hands into his empty pockets, and then squeezing his Welsh wig between them, as if he thought he might wring some gold out of it; ‘but I—the little I have got, isn’t convertible, Ned; it can’t be got at. I have been trying to do something with it for Wally, and I’m old fashioned, and behind the time. It’s here and there, and—and, in short, it’s as good as nowhere,’ said the old man, looking in bewilderment about him.

He had so much the air of a half-witted person who had been hiding his money in a variety of places, and had forgotten where, that the Captain followed his eyes, not without a faint hope that he might remember some few hundred pounds concealed up the chimney, or down in the cellar. But Solomon Gills knew better than that.

And when he got there, sat down in a chair, and fell into a silent fit of laughter

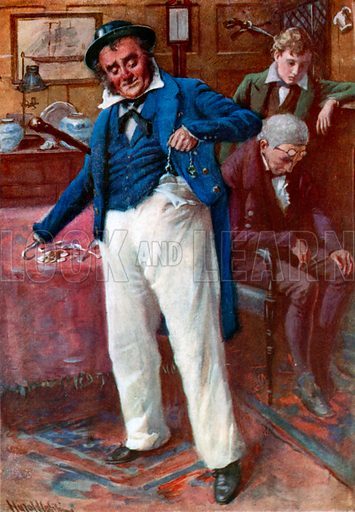

Chapter 10

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

Notwithstanding the palpitation of the heart which these allusions occasioned her, they were anything but disagreeable to Miss Tox, as they enabled her to be extremely interesting, and to manifest an occasional incoherence and distraction which she was not at all unwilling to display. The Major gave her abundant opportunities of exhibiting this emotion: being profuse in his complaints, at dinner, of her desertion of him and Princess’s Place: and as he appeared to derive great enjoyment from making them, they all got on very well.

None the worse on account of the Major taking charge of the whole conversation, and showing as great an appetite in that respect as in regard of the various dainties on the table, among which he may be almost said to have wallowed: greatly to the aggravation of his inflammatory tendencies. Mr Dombey’s habitual silence and reserve yielding readily to this usurpation, the Major felt that he was coming out and shining: and in the flow of spirits thus engendered, rang such an infinite number of new changes on his own name that he quite astonished himself. In a word, they were all very well pleased. The Major was considered to possess an inexhaustible fund of conversation; and when he took a late farewell, after a long rubber, Mr Dombey again complimented the blushing Miss Tox on her neighbour and acquaintance.

But all the way home to his own hotel, the Major incessantly said to himself, and of himself, ‘Sly, Sir—sly, Sir—de-vil-ish sly!’ And when he got there, sat down in a chair, and fell into a silent fit of laughter, with which he was sometimes seized, and which was always particularly awful. It held him so long on this occasion that the dark servant, who stood watching him at a distance, but dared not for his life approach, twice or thrice gave him over for lost. His whole form, but especially his face and head, dilated beyond all former experience; and presented to the dark man’s view, nothing but a heaving mass of indigo. At length he burst into a violent paroxysm of coughing, and when that was a little better burst into such ejaculations as the following:

‘Would you, Ma’am, would you? Mrs Dombey, eh, Ma’am? I think not, Ma’am. Not while Joe B. can put a spoke in your wheel, Ma’am. J. B.‘s even with you now, Ma’am. He isn’t altogether bowled out, yet, Sir, isn’t Bagstock. She’s deep, Sir, deep, but Josh is deeper. Wide awake is old Joe—broad awake, and staring, Sir!’ There was no doubt of this last assertion being true, and to a very fearful extent; as it continued to be during the greater part of that night, which the Major chiefly passed in similar exclamations, diversified with fits of coughing and choking that startled the whole house.

What a wealth of illustrations, Kim! I am puzzled to see, for instance, that Florence has so many different hair colours; I don't know why but I would not imagine her hair as being flaxen, but rather as being more like brunette. Otherwise, she'd look too much like Alice in Wonderland. It's interesting to see what difference it makes if you have Floy rest her head on Paul's shoulder or vice-versa, isn't it?

As to Mrs. Pipchin, I find her very impressive, not least because of her "hard grey eye" but still I think that Phiz did her justice enough. As the comment says, it would be quite infelicitous to present a character in a realistic novel as a fairy-tale book witch. The alienating effect this creates can, I think, be seen in the last illustration you posted: Barnard's Major Bagstock does not look like a real person but like a scarecrow with a pumpkin for a head. I'd say the major was somewhat leaner in his face, but his eyes were more protruding, and apart from that Barnard's figure here fails to come alive.

As to Mrs. Pipchin, I find her very impressive, not least because of her "hard grey eye" but still I think that Phiz did her justice enough. As the comment says, it would be quite infelicitous to present a character in a realistic novel as a fairy-tale book witch. The alienating effect this creates can, I think, be seen in the last illustration you posted: Barnard's Major Bagstock does not look like a real person but like a scarecrow with a pumpkin for a head. I'd say the major was somewhat leaner in his face, but his eyes were more protruding, and apart from that Barnard's figure here fails to come alive.

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "it shows that in his heart of hearts, this granite man, this whited sepulchre of arrogance, is a human being with feelings like love - only he doesn't know how to deal with them, h..."

Love or corruption? That's a good question, Julie: I think Dombey does love his son, although probably more the son that Paul is going to be than the five-year old that is sitting by his side and that cannot, as yet, represent the firm. When they are sitting together, the text, as far as I can remember, says that Dombey pats his son's arm, and I'd say that this can be seen as a sign of love, although the gesture is very hesitant or even interrupted in its middle. Still, the impulse counts, doesn't it?

Dombey's influence on Paul, however, is utterly deplorable. Paul is quite arrogant at times, as you said, and the text somewhere also says that he can be very imperious at times. Definitely his father's example. Paul's way of questioning everything in rather a philosophical way makes me think that his father's example as to the power of money will not make him a Scrooge but rather someone who will try to use his money and power for beneficial purposes. But only time will tell.

Love or corruption? That's a good question, Julie: I think Dombey does love his son, although probably more the son that Paul is going to be than the five-year old that is sitting by his side and that cannot, as yet, represent the firm. When they are sitting together, the text, as far as I can remember, says that Dombey pats his son's arm, and I'd say that this can be seen as a sign of love, although the gesture is very hesitant or even interrupted in its middle. Still, the impulse counts, doesn't it?

Dombey's influence on Paul, however, is utterly deplorable. Paul is quite arrogant at times, as you said, and the text somewhere also says that he can be very imperious at times. Definitely his father's example. Paul's way of questioning everything in rather a philosophical way makes me think that his father's example as to the power of money will not make him a Scrooge but rather someone who will try to use his money and power for beneficial purposes. But only time will tell.

Kim wrote: "

Dombey and Son

Chapter 8

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

Thus Paul grew to be nearly five years old. He was a pretty little fellow; though there was something wan and wistful in his small fa..."

Kim

I love seeing how various illustrators interpret the text and then give us the opportunity to view and “read” their work.

Dombey and his chair. How often do we read - and will continue to discover - his manner and habit of sitting. The illustrations give us the chance to see how he sits as stiffly as his cravat wraps around his neck. Imperial in nature, supreme in place. Lots can be learned from the way a person sits in a chair.

Dombey and Son

Chapter 8

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

Thus Paul grew to be nearly five years old. He was a pretty little fellow; though there was something wan and wistful in his small fa..."

Kim

I love seeing how various illustrators interpret the text and then give us the opportunity to view and “read” their work.

Dombey and his chair. How often do we read - and will continue to discover - his manner and habit of sitting. The illustrations give us the chance to see how he sits as stiffly as his cravat wraps around his neck. Imperial in nature, supreme in place. Lots can be learned from the way a person sits in a chair.

Kim wrote: "

Paul and Mrs. Pipchin

Chapter 8

Phiz

original sketch

In color obviously

Text Illustrated:

At this exemplary old lady, Paul would sit staring in his little arm-chair by the fire, for any..."

It’s no secret that I really enjoy the illustrations of Browne. I’m not sure what kind of chair Dickens wanted, but I like seeing Paul in his chair as is. He is not equal in height to Pipchin, yet his chair does elevate him to near her height. The placement of a withered and dry plant above both Paul and Pipchin’s heads frames the dry and arid world that Paul lives in with her.

Paul’s sad face as he looks toward Pipchin contrasts with her own skewed face that is looking past him to the fire. Meanwhile the cat has its back to them both and contemplates only the fire. It is to Paul that readers direct their sympathy.

Paul and Mrs. Pipchin

Chapter 8

Phiz

original sketch

In color obviously

Text Illustrated:

At this exemplary old lady, Paul would sit staring in his little arm-chair by the fire, for any..."

It’s no secret that I really enjoy the illustrations of Browne. I’m not sure what kind of chair Dickens wanted, but I like seeing Paul in his chair as is. He is not equal in height to Pipchin, yet his chair does elevate him to near her height. The placement of a withered and dry plant above both Paul and Pipchin’s heads frames the dry and arid world that Paul lives in with her.

Paul’s sad face as he looks toward Pipchin contrasts with her own skewed face that is looking past him to the fire. Meanwhile the cat has its back to them both and contemplates only the fire. It is to Paul that readers direct their sympathy.

Kim wrote: "

"The sea, Floy, what is it that it keeps saying?"

Illustration for Pictures from Dickens 1890

John Henry Frederick Bacon

Frances Brundage

From Children's Stories from Dickens 1890"