The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

Ghost on the Throne

ROMAN EMPIRE -THE HISTORY...

>

ARCHIVE~ SPOTLIGHTED BOOK - GHOST ON THE THRONE - GLOSSARY (Spoiler Thread)

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Jun 10, 2020 11:18PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Jun 03, 2020 08:34PM

Mod

Mod

by James Romm (no photo)

by James Romm (no photo)

reply

|

flag

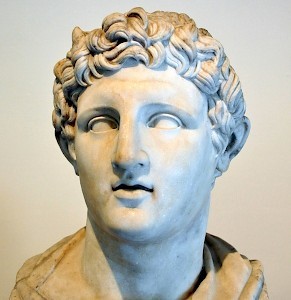

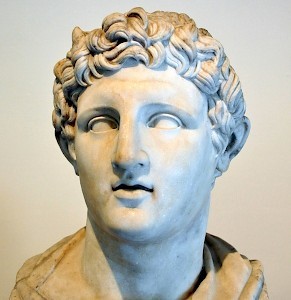

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (Greek: Αλέξανδρος Γʹ ὁ Μακεδών, Aléxandros III ho Makedȏn; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great (Greek: Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Μέγας, Aléxandros ho Mégas), was a king (basileus) of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon and a member of the Argead dynasty. He was born in Pella in 356 BC and succeeded his father Philip II to the throne at the age of 20. He spent most of his ruling years on an unprecedented military campaign through western Asia and northeast Africa, and by the age of thirty, he had created one of the largest empires of the ancient world, stretching from Greece to northwestern India. He was undefeated in battle and is widely considered one of history's most successful military commanders.

During his youth, Alexander was tutored by Aristotle until age 16. After Philip's assassination in 336 BC, he succeeded his father to the throne and inherited a strong kingdom and an experienced army. Alexander was awarded the generalship of Greece and used this authority to launch his father's pan-Hellenic project to lead the Greeks in the conquest of Persia. In 334 BC, he invaded the Achaemenid Empire (Persian Empire) and began a series of campaigns that lasted 10 years. Following the conquest of Anatolia, Alexander broke the power of Persia in a series of decisive battles, most notably the battles of Issus and Gaugamela. He subsequently overthrew Persian King Darius III and conquered the Achaemenid Empire in its entirety. At that point, his empire stretched from the Adriatic Sea to the Beas River.

Alexander endeavoured to reach the "ends of the world and the Great Outer Sea" and invaded India in 326 BC, winning an important victory over the Pauravas at the Battle of the Hydaspes. He eventually turned back at the demand of his homesick troops, dying in Babylon in 323 BC, the city that he planned to establish as his capital, without executing a series of planned campaigns that would have begun with an invasion of Arabia. In the years following his death, a series of civil wars tore his empire apart, resulting in the establishment of several states ruled by the Diadochi, Alexander's surviving generals and heirs.

Alexander's legacy includes the cultural diffusion and syncretism which his conquests engendered, such as Greco-Buddhism. He founded some twenty cities that bore his name, most notably Alexandria in Egypt. Alexander's settlement of Greek colonists and the resulting spread of Greek culture in the east resulted in a new Hellenistic civilization, aspects of which were still evident in the traditions of the Byzantine Empire in the mid-15th century AD and the presence of Greek speakers in central and far eastern Anatolia until the Greek genocide of the 1920s. Alexander became legendary as a classical hero in the mould of Achilles, and he features prominently in the history and mythic traditions of both Greek and non-Greek cultures. He was undefeated in battle and became the measure against which military leaders compared themselves. Military academies throughout the world still teach his tactics. He is often ranked among the most influential people in history.

Remainder of article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexand...

Source: Wikipedia

More:

https://www.history.com/topics/ancien...

https://www.livescience.com/39997-ale...

https://www.britannica.com/biography/...

https://www.ancient.eu/Alexander_the_...

https://www.biography.com/political-f...

by

by

Philip Freeman

Philip Freeman

by

by

Sean Patrick

Sean Patrick

by

by

Anthony Everitt

Anthony Everitt

by

by

Plutarch

Plutarch

by

by

Paul Anthony Cartledge

Paul Anthony Cartledge

Alexander III of Macedon (Greek: Αλέξανδρος Γʹ ὁ Μακεδών, Aléxandros III ho Makedȏn; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great (Greek: Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Μέγας, Aléxandros ho Mégas), was a king (basileus) of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon and a member of the Argead dynasty. He was born in Pella in 356 BC and succeeded his father Philip II to the throne at the age of 20. He spent most of his ruling years on an unprecedented military campaign through western Asia and northeast Africa, and by the age of thirty, he had created one of the largest empires of the ancient world, stretching from Greece to northwestern India. He was undefeated in battle and is widely considered one of history's most successful military commanders.

During his youth, Alexander was tutored by Aristotle until age 16. After Philip's assassination in 336 BC, he succeeded his father to the throne and inherited a strong kingdom and an experienced army. Alexander was awarded the generalship of Greece and used this authority to launch his father's pan-Hellenic project to lead the Greeks in the conquest of Persia. In 334 BC, he invaded the Achaemenid Empire (Persian Empire) and began a series of campaigns that lasted 10 years. Following the conquest of Anatolia, Alexander broke the power of Persia in a series of decisive battles, most notably the battles of Issus and Gaugamela. He subsequently overthrew Persian King Darius III and conquered the Achaemenid Empire in its entirety. At that point, his empire stretched from the Adriatic Sea to the Beas River.

Alexander endeavoured to reach the "ends of the world and the Great Outer Sea" and invaded India in 326 BC, winning an important victory over the Pauravas at the Battle of the Hydaspes. He eventually turned back at the demand of his homesick troops, dying in Babylon in 323 BC, the city that he planned to establish as his capital, without executing a series of planned campaigns that would have begun with an invasion of Arabia. In the years following his death, a series of civil wars tore his empire apart, resulting in the establishment of several states ruled by the Diadochi, Alexander's surviving generals and heirs.

Alexander's legacy includes the cultural diffusion and syncretism which his conquests engendered, such as Greco-Buddhism. He founded some twenty cities that bore his name, most notably Alexandria in Egypt. Alexander's settlement of Greek colonists and the resulting spread of Greek culture in the east resulted in a new Hellenistic civilization, aspects of which were still evident in the traditions of the Byzantine Empire in the mid-15th century AD and the presence of Greek speakers in central and far eastern Anatolia until the Greek genocide of the 1920s. Alexander became legendary as a classical hero in the mould of Achilles, and he features prominently in the history and mythic traditions of both Greek and non-Greek cultures. He was undefeated in battle and became the measure against which military leaders compared themselves. Military academies throughout the world still teach his tactics. He is often ranked among the most influential people in history.

Remainder of article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexand...

Source: Wikipedia

More:

https://www.history.com/topics/ancien...

https://www.livescience.com/39997-ale...

https://www.britannica.com/biography/...

https://www.ancient.eu/Alexander_the_...

https://www.biography.com/political-f...

by

by

Philip Freeman

Philip Freeman by

by

Sean Patrick

Sean Patrick by

by

Anthony Everitt

Anthony Everitt by

by

Plutarch

Plutarch by

by

Paul Anthony Cartledge

Paul Anthony Cartledge

Ancient Macedonia

Macedonia, ancient kingdom centred on the plain in the northeastern corner of the Greek peninsula, at the head of the Gulf of Thérmai. In the 4th century bce it achieved hegemony over Greece and conquered lands as far east as the Indus River, establishing a short-lived empire that introduced the Hellenistic Age of ancient Greek civilization.

The cultural links of prehistoric Macedonia were mainly with Greece and Anatolia. A people who called themselves Macedonians are known from about 700 bce, when they pushed eastward from their home on the Haliacmon (Aliákmon) River under the leadership of King Perdiccas I and his successors. The origin and identity of this people are much debated and are at the centre of a heated modern dispute between those who argue that this people should be considered ethnically Greek and those who argue that they were not Greek or that their origin and identity cannot be determined. This dispute hinges in part on the question of whether this people spoke a form of Greek before the 5th century bce; it is known, however, that by the 5th century bce the Macedonian elite had adopted a form of ancient Greek and had also forged a unified kingdom. Athenian control of the coastal regions forced Macedonian rulers to concentrate on bringing the uplands and plains of Macedonia under their sway—a task finally achieved by their king Amyntas III (reigned c. 393–370/369 bce).

Two of Amyntas’s sons, Alexander II and Perdiccas III, reigned only briefly. Amyntas’s third son, Philip II, assumed control in the name of Perdiccas’s infant heir, but, having restored order, he made himself king (reigned 359–336) and raised Macedonia to a predominant position in Greece.

Philip’s son Alexander III (Alexander the Great; reigned 336–323) overthrew the Achaemenian (Persian) Empire and expanded Macedonia’s dominion to the Nile and Indus rivers. On Alexander’s death at Babylon his generals divided up the satrapies (provinces) of his empire and used them as bases in a struggle to acquire the whole. From 321 to 301 warfare was almost continual. Macedonia itself remained the heart of the empire, and its possession (along with the control of Greece) was keenly contested. Antipater (Alexander’s regent in Europe) and his son Cassander managed to retain control of Macedonia and Greece until Cassander’s death (297), which threw Macedonia into civil war. After a six-year rule (294–288) by Demetrius I Poliorcetes, Macedonia again fell into a state of internal confusion, intensified by Galatian marauders from the north. In 277 Antigonus II Gonatas, the capable son of Demetrius, repulsed the Galatians and was hailed as king by the Macedonian army. Under him the country achieved a stable monarchy—the Antigonid dynasty, which ruled Macedonia from 277 to 168.

Under Philip V (reigned 221–179) and his son Perseus (reigned 179–168), Macedonia clashed with Rome and lost. Under Roman control Macedonia at first (168–146) formed four independent republics without common bonds. In 146, however, it became a Roman province with the four sections as administrative units. Macedonia remained the bulwark of Greece, and the northern frontiers saw frequent campaigning against neighbouring tribes. Toward 400 ce it was divided into the provinces of Macedonia and Macedonia secunda, within the diocese of Moesia.

(Source: https://www.britannica.com/place/Mace...)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macedon...

https://www.history.com/topics/ancien...

https://www.ancient.eu/macedon/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=05eBO...

http://www.historyofmacedonia.org/Con...

by

by

Richard A. Billows

Richard A. Billows

by Ian Worthington (no photo)

by Ian Worthington (no photo)

by John D. Grainger (no photo)

by John D. Grainger (no photo)

by James R. Ashley (no photo)

by James R. Ashley (no photo)

by Arthur Mapletoft Curteis (no photo)

by Arthur Mapletoft Curteis (no photo)

Macedonia, ancient kingdom centred on the plain in the northeastern corner of the Greek peninsula, at the head of the Gulf of Thérmai. In the 4th century bce it achieved hegemony over Greece and conquered lands as far east as the Indus River, establishing a short-lived empire that introduced the Hellenistic Age of ancient Greek civilization.

The cultural links of prehistoric Macedonia were mainly with Greece and Anatolia. A people who called themselves Macedonians are known from about 700 bce, when they pushed eastward from their home on the Haliacmon (Aliákmon) River under the leadership of King Perdiccas I and his successors. The origin and identity of this people are much debated and are at the centre of a heated modern dispute between those who argue that this people should be considered ethnically Greek and those who argue that they were not Greek or that their origin and identity cannot be determined. This dispute hinges in part on the question of whether this people spoke a form of Greek before the 5th century bce; it is known, however, that by the 5th century bce the Macedonian elite had adopted a form of ancient Greek and had also forged a unified kingdom. Athenian control of the coastal regions forced Macedonian rulers to concentrate on bringing the uplands and plains of Macedonia under their sway—a task finally achieved by their king Amyntas III (reigned c. 393–370/369 bce).

Two of Amyntas’s sons, Alexander II and Perdiccas III, reigned only briefly. Amyntas’s third son, Philip II, assumed control in the name of Perdiccas’s infant heir, but, having restored order, he made himself king (reigned 359–336) and raised Macedonia to a predominant position in Greece.

Philip’s son Alexander III (Alexander the Great; reigned 336–323) overthrew the Achaemenian (Persian) Empire and expanded Macedonia’s dominion to the Nile and Indus rivers. On Alexander’s death at Babylon his generals divided up the satrapies (provinces) of his empire and used them as bases in a struggle to acquire the whole. From 321 to 301 warfare was almost continual. Macedonia itself remained the heart of the empire, and its possession (along with the control of Greece) was keenly contested. Antipater (Alexander’s regent in Europe) and his son Cassander managed to retain control of Macedonia and Greece until Cassander’s death (297), which threw Macedonia into civil war. After a six-year rule (294–288) by Demetrius I Poliorcetes, Macedonia again fell into a state of internal confusion, intensified by Galatian marauders from the north. In 277 Antigonus II Gonatas, the capable son of Demetrius, repulsed the Galatians and was hailed as king by the Macedonian army. Under him the country achieved a stable monarchy—the Antigonid dynasty, which ruled Macedonia from 277 to 168.

Under Philip V (reigned 221–179) and his son Perseus (reigned 179–168), Macedonia clashed with Rome and lost. Under Roman control Macedonia at first (168–146) formed four independent republics without common bonds. In 146, however, it became a Roman province with the four sections as administrative units. Macedonia remained the bulwark of Greece, and the northern frontiers saw frequent campaigning against neighbouring tribes. Toward 400 ce it was divided into the provinces of Macedonia and Macedonia secunda, within the diocese of Moesia.

(Source: https://www.britannica.com/place/Mace...)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macedon...

https://www.history.com/topics/ancien...

https://www.ancient.eu/macedon/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=05eBO...

http://www.historyofmacedonia.org/Con...

by

by

Richard A. Billows

Richard A. Billows by Ian Worthington (no photo)

by Ian Worthington (no photo) by John D. Grainger (no photo)

by John D. Grainger (no photo) by James R. Ashley (no photo)

by James R. Ashley (no photo) by Arthur Mapletoft Curteis (no photo)

by Arthur Mapletoft Curteis (no photo)

Alexander the Great timeline

356 B.C.

Alexander born in Pella. The exact date in unknown, but probably either 20 or 26 July.

Philip captures Potidaea.

Parmenio defeats Paeonians and Illyrians.

354 B.C.

Demosthenes attacks idea of a ‘crusade against Persia’.

Mid-summer: Philip captures Mathone: loses an eye in the battle.

352 B.C.

Artabazus and Memnon refugees with Philip, who now emerges as potential leader of crusade against Persia.

351 B.C.

Philip’s fleet harassing Athenian shipping.

Demosthenes’ First Philippic.

348 B.C.

August: Philip captures Olynthus.

Aeschines’ attempt to unite Greek states against Philip fails.

346 B.C.

March: embassy to Philip from Athens.

Halus besieged by Parmeniio

April: peace of Philocrates ratified.

Second Athenian embassy held up till July.

July: Philip occupies Thermopylae.

August: Philip admitted to seat on Amphictyonic Council, and presides over Pythian Games.

Isocrates publishes Philippus.

344 B.C.

Philip appointed Archon of Thessaly for life.

343 B.C.

Non-aggression pact between Philip and Artaxerxes Ochus.

Trail and acquittal of Aeschines.

343 B.C.

Aristotle invited to Macedonia al Alexander’s tutor.

342 B.C.

Olympia’s brother Alexander succeeds to throne of Epirus with Philip’s backing.

340 B.C.

Congress of Allies meets in Athens.

Demosthenes awarded gold crown at Dionysia.

Alexander left as Regent in Macedonia: his raid on Maedi and the foundation of Alexandropolis.

Philip’s campaign against Perinthus and Byzantium.

339 B.C.

September: Philip occupies Elatea.

Isocrates’ Panathenaicus.

338 ? B.C.

August 2: Battle of Chaeronea.

Alexander among ambassadors to Athens.

Philip marries Attalus’ niece Cleopatra.

Oylmpias and Alexander in exile.

337 B.C.

Spring: Hellenic League convened at Corinth.

Recall of Alexander to Pella.

Autumn: League at Corinth ratifies crusade to against Persia.

336 B.C.

Spring: Parmenoi and Attalus sent to Asia Minor for preliminary

military operations.

June: accession of Darius III Codomannus.

Cleopatra bears Philip a son.

Wedding of Alexander of Epirus to Olympia’s daughter.

Murder of Philip.

Alexander accedes to the throne of Macedonia.

Late summer: Alexander calls meeting of Hellenie League at

Corinth, confirmed as Captain-General of anti-Persian crusade.

335 B.C.

Early spring: Alexander goes north to deal with Thrace and Illyria.

Revolt of Thebes.

334 B.C.

Alexander and the attacking force cross into Asia Minor.

May: Battle of the Granicus.

General reorganization of Greek cities in Asia Minor.

Siege and capture of Miletus.

Autumn: reduction of Halicarnassus.

Alexander advances through Lycia and Pamphylia.

333 B.C.

Alexander’s column moves north to Celaenae and Gordium.

Death of Memnon.

Mustering of Persian forces in Babylon.

Episode of the Gordian Knot.

Alexander marches to Ancyra and thence south to Cilician Gates.

Darius moves westward from Babylon.

September: Alexander reaches Tarsus: his illness there.

Darius crosses the Euphrates.

? Sept.-Oct.: Battle if Issus.

Alexander advances southward though Phoenicia.

Marathus: first peace-offer by Darius.

332 B.C.

? January: submission of Byblos and Sidon.

Siege of Tyre begun.

? June: second peace-offer by Darius refused.

July 29: fall of Tyre.

Sept.-Oct.: Gaza captured.

? November 14: Alexander crowned as Pharaoh at Memphis.

331 B.C.

Early spring: visit to the Oracle of Ammon at Siwah.

? April 7-8: foundation of Alexanderia.

Alexander returns to Tyre.

July-August: Alexander reaches Thapsacus on Euphrates; Darius moves his main forces from Babylon.

September 18: Alexander crosses the Tigris.

Darius’ final peace-offer rejected.

Sept. 30 or Oct. 1: Battle of Gaugamela.

Macedonians advance from Arbela on Babylon, which falls in mid-October.

Revolt of Agis defeated at Megalopolis.

Early December: Alexander occupies Susa unopposed.

Alexander forces Susian Gates.

330 B.C.

? January: Alexander reaches and sacks Perseplis.

? May : burning of temples etc. in Persepols.

Early June: Alexander sets out for Ecbatana.

Darius retreats toward Bactria.

Greek allies dismissed at Ecbatana; Parmenio left behind there, with Harpalus as Treasurer.

Pursuit of Darius renewed, via Caspian Gates.

July; Darius found murdered near Hecatompylus.

Bessus establishes himself as ‘Great King’ in Bactria.

March for Hyrcania begins.

Late August: march to Drangiana.

The ‘conspiracy of Philotas’.

March though Arachosia to Parapamisidae.

329 B.C.

March-April: Alexander crosses Hindu Kush by Khawak Pass.

April-May: Alexander advancing to Bactria; Bessus retreats across the Oxus.

June: Alexander reaches and crosses the Oxus; veterans and

Thessalian volunteers dismissed.

Surrender of Bessus.

Alexander advances to Maracanda.

Revolt of Spitamenes, annihilation of Macedonian detachment

Alexander takes up winter quarters at Zariaspa.

Execution of Bessus.

328 B.C.

Campaign against Spitamenes.

Autumn: murder of Cleitus the Black.

Defeat and death of Spitamenes.

327 B.C.

Spring: capture of the Soghdian Rock.

Alexander’s marriage to Roxane.

Recruitment of 30,000 Perisan ‘Successors’.

The ‘Pages Conspiracy’ and Callisthenes’ end.

Early summer: Alexander recrosses Hindu Kush by Kushan Pass: the invasion of India begins.

Alexander reaches Nysa; the ‘Dionysus episode’.

Capture of Aornos.

326 B.C.

Advance to Taxila.

Battle of the Hydaspes (The Jhelum) against the rajah Porus.

Death of Bucephalas.

? July: Mutiny at the Hyphasis.

Return to the Jhelum: reinforcements move down-river.

Campaign against Brahmin cities: Alexander seriously wounded.

325 B.C.

Revolt in Bactria: 3000 mercenaries loose in Asia.

Alexander reaches Patala, builds harbor and dockyards.

? September: Alexander’s march through Gedrosian Desert.

Defection of Harpalus from Asia Minor to Greece.

The satrapal purge begins.

Nearchus and the fleet reach Harmozia, link up with Alexander at Salmous.

Arrival of Craterus form Drangiana.

324 B.C.

January: Nearches and fleet sent on to Susa.

The episode of Cyrus’ tomb.

Alexander returns to Persepolis.

Move to Susa, long halt there.

Spring: arrival of 30,000 trained Persian ‘Successors’.

The Susa mass-marriages.

March: the Exiles’ Decree and the Deification Decree.

Craterus appointed to succeed Antiparter as Regent, and convoy troops home.

Alexander moves from Susa to Ecbatana.

Death of Hephaestion.

323 B.C.

Assassination of Harpalus in Crete.

Alexander’s Campaign against the Cossaeans and return to Babylon.

Alexander explores Pallacopas Canal; his boat-trip through the marshes.

Arrival of Antipater’s son Cassander to negotiate with Alexander.

May 20/30: Alexander falls ill after a party; and dies on 10/11th June.

(Source: https://vmacedonia.com/history/ancien...)

356 B.C.

Alexander born in Pella. The exact date in unknown, but probably either 20 or 26 July.

Philip captures Potidaea.

Parmenio defeats Paeonians and Illyrians.

354 B.C.

Demosthenes attacks idea of a ‘crusade against Persia’.

Mid-summer: Philip captures Mathone: loses an eye in the battle.

352 B.C.

Artabazus and Memnon refugees with Philip, who now emerges as potential leader of crusade against Persia.

351 B.C.

Philip’s fleet harassing Athenian shipping.

Demosthenes’ First Philippic.

348 B.C.

August: Philip captures Olynthus.

Aeschines’ attempt to unite Greek states against Philip fails.

346 B.C.

March: embassy to Philip from Athens.

Halus besieged by Parmeniio

April: peace of Philocrates ratified.

Second Athenian embassy held up till July.

July: Philip occupies Thermopylae.

August: Philip admitted to seat on Amphictyonic Council, and presides over Pythian Games.

Isocrates publishes Philippus.

344 B.C.

Philip appointed Archon of Thessaly for life.

343 B.C.

Non-aggression pact between Philip and Artaxerxes Ochus.

Trail and acquittal of Aeschines.

343 B.C.

Aristotle invited to Macedonia al Alexander’s tutor.

342 B.C.

Olympia’s brother Alexander succeeds to throne of Epirus with Philip’s backing.

340 B.C.

Congress of Allies meets in Athens.

Demosthenes awarded gold crown at Dionysia.

Alexander left as Regent in Macedonia: his raid on Maedi and the foundation of Alexandropolis.

Philip’s campaign against Perinthus and Byzantium.

339 B.C.

September: Philip occupies Elatea.

Isocrates’ Panathenaicus.

338 ? B.C.

August 2: Battle of Chaeronea.

Alexander among ambassadors to Athens.

Philip marries Attalus’ niece Cleopatra.

Oylmpias and Alexander in exile.

337 B.C.

Spring: Hellenic League convened at Corinth.

Recall of Alexander to Pella.

Autumn: League at Corinth ratifies crusade to against Persia.

336 B.C.

Spring: Parmenoi and Attalus sent to Asia Minor for preliminary

military operations.

June: accession of Darius III Codomannus.

Cleopatra bears Philip a son.

Wedding of Alexander of Epirus to Olympia’s daughter.

Murder of Philip.

Alexander accedes to the throne of Macedonia.

Late summer: Alexander calls meeting of Hellenie League at

Corinth, confirmed as Captain-General of anti-Persian crusade.

335 B.C.

Early spring: Alexander goes north to deal with Thrace and Illyria.

Revolt of Thebes.

334 B.C.

Alexander and the attacking force cross into Asia Minor.

May: Battle of the Granicus.

General reorganization of Greek cities in Asia Minor.

Siege and capture of Miletus.

Autumn: reduction of Halicarnassus.

Alexander advances through Lycia and Pamphylia.

333 B.C.

Alexander’s column moves north to Celaenae and Gordium.

Death of Memnon.

Mustering of Persian forces in Babylon.

Episode of the Gordian Knot.

Alexander marches to Ancyra and thence south to Cilician Gates.

Darius moves westward from Babylon.

September: Alexander reaches Tarsus: his illness there.

Darius crosses the Euphrates.

? Sept.-Oct.: Battle if Issus.

Alexander advances southward though Phoenicia.

Marathus: first peace-offer by Darius.

332 B.C.

? January: submission of Byblos and Sidon.

Siege of Tyre begun.

? June: second peace-offer by Darius refused.

July 29: fall of Tyre.

Sept.-Oct.: Gaza captured.

? November 14: Alexander crowned as Pharaoh at Memphis.

331 B.C.

Early spring: visit to the Oracle of Ammon at Siwah.

? April 7-8: foundation of Alexanderia.

Alexander returns to Tyre.

July-August: Alexander reaches Thapsacus on Euphrates; Darius moves his main forces from Babylon.

September 18: Alexander crosses the Tigris.

Darius’ final peace-offer rejected.

Sept. 30 or Oct. 1: Battle of Gaugamela.

Macedonians advance from Arbela on Babylon, which falls in mid-October.

Revolt of Agis defeated at Megalopolis.

Early December: Alexander occupies Susa unopposed.

Alexander forces Susian Gates.

330 B.C.

? January: Alexander reaches and sacks Perseplis.

? May : burning of temples etc. in Persepols.

Early June: Alexander sets out for Ecbatana.

Darius retreats toward Bactria.

Greek allies dismissed at Ecbatana; Parmenio left behind there, with Harpalus as Treasurer.

Pursuit of Darius renewed, via Caspian Gates.

July; Darius found murdered near Hecatompylus.

Bessus establishes himself as ‘Great King’ in Bactria.

March for Hyrcania begins.

Late August: march to Drangiana.

The ‘conspiracy of Philotas’.

March though Arachosia to Parapamisidae.

329 B.C.

March-April: Alexander crosses Hindu Kush by Khawak Pass.

April-May: Alexander advancing to Bactria; Bessus retreats across the Oxus.

June: Alexander reaches and crosses the Oxus; veterans and

Thessalian volunteers dismissed.

Surrender of Bessus.

Alexander advances to Maracanda.

Revolt of Spitamenes, annihilation of Macedonian detachment

Alexander takes up winter quarters at Zariaspa.

Execution of Bessus.

328 B.C.

Campaign against Spitamenes.

Autumn: murder of Cleitus the Black.

Defeat and death of Spitamenes.

327 B.C.

Spring: capture of the Soghdian Rock.

Alexander’s marriage to Roxane.

Recruitment of 30,000 Perisan ‘Successors’.

The ‘Pages Conspiracy’ and Callisthenes’ end.

Early summer: Alexander recrosses Hindu Kush by Kushan Pass: the invasion of India begins.

Alexander reaches Nysa; the ‘Dionysus episode’.

Capture of Aornos.

326 B.C.

Advance to Taxila.

Battle of the Hydaspes (The Jhelum) against the rajah Porus.

Death of Bucephalas.

? July: Mutiny at the Hyphasis.

Return to the Jhelum: reinforcements move down-river.

Campaign against Brahmin cities: Alexander seriously wounded.

325 B.C.

Revolt in Bactria: 3000 mercenaries loose in Asia.

Alexander reaches Patala, builds harbor and dockyards.

? September: Alexander’s march through Gedrosian Desert.

Defection of Harpalus from Asia Minor to Greece.

The satrapal purge begins.

Nearchus and the fleet reach Harmozia, link up with Alexander at Salmous.

Arrival of Craterus form Drangiana.

324 B.C.

January: Nearches and fleet sent on to Susa.

The episode of Cyrus’ tomb.

Alexander returns to Persepolis.

Move to Susa, long halt there.

Spring: arrival of 30,000 trained Persian ‘Successors’.

The Susa mass-marriages.

March: the Exiles’ Decree and the Deification Decree.

Craterus appointed to succeed Antiparter as Regent, and convoy troops home.

Alexander moves from Susa to Ecbatana.

Death of Hephaestion.

323 B.C.

Assassination of Harpalus in Crete.

Alexander’s Campaign against the Cossaeans and return to Babylon.

Alexander explores Pallacopas Canal; his boat-trip through the marshes.

Arrival of Antipater’s son Cassander to negotiate with Alexander.

May 20/30: Alexander falls ill after a party; and dies on 10/11th June.

(Source: https://vmacedonia.com/history/ancien...)

Olympias

Olympias (Ancient Greek: Ὀλυμπιάς, pronounced [olympiás], c. 375–316 BC) was the daughter of king Neoptolemus I of Epirus, the sister of Alexander I of Epirus, the fourth wife of Philip II, the king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia and the mother of Alexander the Great. She was extremely influential in Alexander's life and was recognized as de facto leader of Macedon during Alexander's conquests. After her son's death, she fought on behalf of Alexander's son Alexander IV, successfully defeating Adea Eurydice. After she was finally defeated by Cassander, his armies refused to execute her, and he finally had to summon family members of those Olympias had previously killed to end her life. According to the 1st century AD biographer, Plutarch, she was a devout member of the orgiastic snake-worshiping cult of Dionysus, and he suggests that she slept with snakes in her bed.

Origin

Olympias was the daughter of Neoptolemus I, king of the Molossians, an ancient Greek tribe in Epirus, and sister of Alexander I. Her family belonged to the Aeacidae, a well-respected family of Epirus, which claimed descent from Neoptolemus, son of Achilles. Apparently, she was originally named Polyxena, as Plutarch mentions in his work Moralia, and changed her name to Myrtale prior to her marriage to Philip II of Macedon as part of her initiation into an unknown mystery cult.

The name Olympias was the third of four names by which she was known. She probably took it as a recognition of Philip's victory in the Olympic Games of 356 BC, the news of which coincided with Alexander's birth (Plut. Alexander 3.8). She was finally named Stratonice, which was probably an epithet attached to Olympias following her victory over Eurydice in 317 BC.

Queen of Macedonia

When I died in 360 BC, his brother Arymbas succeeded him on the Molossian throne. In 358 BC, Arymbas made a treaty with the new king of Macedonia, Philip II, and the Molossians became allies of the Macedonians. The alliance was cemented with a diplomatic marriage between Arymbas' niece, Olympias, and Philip in 357 BC. It made Olympias the queen consort of Macedonia, and Philip the king. Philip had allegedly fallen in love with Olympias when both were initiated into the mysteries of Cabeiri at the Sanctuary of the Great Gods, on the island of Samothrace, though their marriage was largely political in nature.

One year later, in 356 BC, Philip's race horse won in the Olympic Games; for this victory, his wife, who was known then as Myrtale, received the name Olympias. In the summer of the same year, Olympias gave birth to her first child, Alexander. In ancient Greece people believed that the birth of a great man was accompanied by portents. As Plutarch describes, the night before the consummation of their marriage, Olympias dreamed that a thunderbolt fell upon her womb and a great fire was kindled, its flames dispersed all about and then were extinguished. After the marriage Philip dreamed that he put a seal upon his wife's womb, the device of which was the figure of a lion. Aristander's interpretation was that Olympias was pregnant of a son whose nature would be bold and lion-like. Philip and Olympias also had a daughter, Cleopatra, who later married her uncle, Alexander I of Epirus, to further diplomatic ties between Macedonia and Epirus.

According to primary sources, their marriage was very stormy due to Philip's volatility and Olympias' ambition and alleged jealousy, which led to their growing estrangement. Things got more tumultuous in 337 BC when Philip married a noble Macedonian woman, Cleopatra, the niece of Attalus, who was given the name Eurydice by Philip. At a gathering after the marriage, Philip failed to defend Alexander's claim to the Macedonian throne when Attalus threatened his legitimacy, causing great tensions between Philip, Olympias, and Alexander. Olympias went into voluntary exile in Epirus along with Alexander, staying at the Molossian court of her brother Alexander I, who was the king at the time.

In 336 BC, Philip cemented his ties to Alexander I of Epirus by offering him the hand of his and Olympias' daughter Cleopatra in marriage, a fact that led Olympias to further isolation as she could no longer count on her brother's support. However, Philip was murdered by Pausanias, a member of Philip's somatophylakes, his personal bodyguard, while attending the wedding, and Olympias, who returned to Macedonia, was suspected of having countenanced his assassination.

Alexander's reign and the Wars of the Diadochi

After the death of Philip II, Olympias allegedly ordered the execution of Eurydice and her child in order to secure Alexander's position as king of Macedonia. During Alexander's campaigns, she regularly corresponded with him and may have confirmed her son's claim in Egypt that his father was not Philip but Zeus. The relationship between Olympias and Alexander was cordial, but her son tried to keep her away from politics. However, she wielded great influence in Macedonia and caused troubles to Antipater, the regent of the kingdom. In 330 BC, she returned to Epirus and served as a regent to her cousin Aeacides in the Epirote state, as her brother Alexander I had died during a campaign in southern Italy.

After Alexander the Great's death in Babylon in 323 BC, his wife Roxana gave birth to their son named Alexander IV. Alexander IV and with his uncle Philip III Arrhidaeus, the half brother of Alexander the Great who may have been disabled, were subject to the regency of Perdiccas, who tried to strengthen his position through a marriage with Antipater's daughter Nicaea. At the same time, Olympias offered Perdiccas the hand of her and Philip's daughter, Cleopatra. Perdiccas chose Cleopatra, which angered Antipater, who allied himself with several other Diadochi, deposed Perdiccas, and was declared regent, only to die within the year.

Polyperchon succeeded Antipater in 319 BC as regent, but Antipater's son Cassander established Philip II's son Philip III (Arrhidaeus) as king and forced Polyperchon out of Macedonia. He fled to Epirus, taking Roxana and her son Alexander IV with him, who had previously been left in the care of Olympias. At the beginning, Olympias had not been involved in this conflict, but she soon realized that in the case of Cassander's rule, her grandson would lose the crown, so she allied with Polyperchon in 317 BC. The Macedonian soldiers supported her return and the united armies of Polyperchon and Olympias, with the house of Aeacides, invaded Macedonia to drive Cassander out from power.

After winning in battle by convincing the army of Adea Eurydice, the wife of Philip III, to side with her own, Olympias captured and executed the two in October 317 BC. She also captured Cassander's brother and a hundred of his partisans. Cassander soon blockaded and besieged Olympias in Pydna and one of the terms of the capitulation had been that Olympias's life would be saved, but Cassander had decided to execute her, sparing only temporarily the lives of Roxana and Alexander IV (they were executed a few years later in 309 BC). When the fortress of Pydna fell, Cassander ordered Olympias killed, but the soldiers refused to harm the mother of Alexander the Great. In the end, the families of her many victims stoned her to death with the approval of Cassander, who is also said to have denied to her body the rites of burial.

(Source:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olympias)

More:

https://www.ancient.eu/Olympias/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/...

https://www.livius.org/articles/perso...

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/hi...

https://www.thoughtco.com/queen-olymp...

by Elizabeth Carney (no photo)

by Elizabeth Carney (no photo)

by Sharon L. James (no photo)

by Sharon L. James (no photo)

by Books LLC (no photo)

by Books LLC (no photo)

by Guida M. Jackson (no photo)

by Guida M. Jackson (no photo)

by Michael A. Dimitri (no photo)

by Michael A. Dimitri (no photo)

Olympias (Ancient Greek: Ὀλυμπιάς, pronounced [olympiás], c. 375–316 BC) was the daughter of king Neoptolemus I of Epirus, the sister of Alexander I of Epirus, the fourth wife of Philip II, the king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia and the mother of Alexander the Great. She was extremely influential in Alexander's life and was recognized as de facto leader of Macedon during Alexander's conquests. After her son's death, she fought on behalf of Alexander's son Alexander IV, successfully defeating Adea Eurydice. After she was finally defeated by Cassander, his armies refused to execute her, and he finally had to summon family members of those Olympias had previously killed to end her life. According to the 1st century AD biographer, Plutarch, she was a devout member of the orgiastic snake-worshiping cult of Dionysus, and he suggests that she slept with snakes in her bed.

Origin

Olympias was the daughter of Neoptolemus I, king of the Molossians, an ancient Greek tribe in Epirus, and sister of Alexander I. Her family belonged to the Aeacidae, a well-respected family of Epirus, which claimed descent from Neoptolemus, son of Achilles. Apparently, she was originally named Polyxena, as Plutarch mentions in his work Moralia, and changed her name to Myrtale prior to her marriage to Philip II of Macedon as part of her initiation into an unknown mystery cult.

The name Olympias was the third of four names by which she was known. She probably took it as a recognition of Philip's victory in the Olympic Games of 356 BC, the news of which coincided with Alexander's birth (Plut. Alexander 3.8). She was finally named Stratonice, which was probably an epithet attached to Olympias following her victory over Eurydice in 317 BC.

Queen of Macedonia

When I died in 360 BC, his brother Arymbas succeeded him on the Molossian throne. In 358 BC, Arymbas made a treaty with the new king of Macedonia, Philip II, and the Molossians became allies of the Macedonians. The alliance was cemented with a diplomatic marriage between Arymbas' niece, Olympias, and Philip in 357 BC. It made Olympias the queen consort of Macedonia, and Philip the king. Philip had allegedly fallen in love with Olympias when both were initiated into the mysteries of Cabeiri at the Sanctuary of the Great Gods, on the island of Samothrace, though their marriage was largely political in nature.

One year later, in 356 BC, Philip's race horse won in the Olympic Games; for this victory, his wife, who was known then as Myrtale, received the name Olympias. In the summer of the same year, Olympias gave birth to her first child, Alexander. In ancient Greece people believed that the birth of a great man was accompanied by portents. As Plutarch describes, the night before the consummation of their marriage, Olympias dreamed that a thunderbolt fell upon her womb and a great fire was kindled, its flames dispersed all about and then were extinguished. After the marriage Philip dreamed that he put a seal upon his wife's womb, the device of which was the figure of a lion. Aristander's interpretation was that Olympias was pregnant of a son whose nature would be bold and lion-like. Philip and Olympias also had a daughter, Cleopatra, who later married her uncle, Alexander I of Epirus, to further diplomatic ties between Macedonia and Epirus.

According to primary sources, their marriage was very stormy due to Philip's volatility and Olympias' ambition and alleged jealousy, which led to their growing estrangement. Things got more tumultuous in 337 BC when Philip married a noble Macedonian woman, Cleopatra, the niece of Attalus, who was given the name Eurydice by Philip. At a gathering after the marriage, Philip failed to defend Alexander's claim to the Macedonian throne when Attalus threatened his legitimacy, causing great tensions between Philip, Olympias, and Alexander. Olympias went into voluntary exile in Epirus along with Alexander, staying at the Molossian court of her brother Alexander I, who was the king at the time.

In 336 BC, Philip cemented his ties to Alexander I of Epirus by offering him the hand of his and Olympias' daughter Cleopatra in marriage, a fact that led Olympias to further isolation as she could no longer count on her brother's support. However, Philip was murdered by Pausanias, a member of Philip's somatophylakes, his personal bodyguard, while attending the wedding, and Olympias, who returned to Macedonia, was suspected of having countenanced his assassination.

Alexander's reign and the Wars of the Diadochi

After the death of Philip II, Olympias allegedly ordered the execution of Eurydice and her child in order to secure Alexander's position as king of Macedonia. During Alexander's campaigns, she regularly corresponded with him and may have confirmed her son's claim in Egypt that his father was not Philip but Zeus. The relationship between Olympias and Alexander was cordial, but her son tried to keep her away from politics. However, she wielded great influence in Macedonia and caused troubles to Antipater, the regent of the kingdom. In 330 BC, she returned to Epirus and served as a regent to her cousin Aeacides in the Epirote state, as her brother Alexander I had died during a campaign in southern Italy.

After Alexander the Great's death in Babylon in 323 BC, his wife Roxana gave birth to their son named Alexander IV. Alexander IV and with his uncle Philip III Arrhidaeus, the half brother of Alexander the Great who may have been disabled, were subject to the regency of Perdiccas, who tried to strengthen his position through a marriage with Antipater's daughter Nicaea. At the same time, Olympias offered Perdiccas the hand of her and Philip's daughter, Cleopatra. Perdiccas chose Cleopatra, which angered Antipater, who allied himself with several other Diadochi, deposed Perdiccas, and was declared regent, only to die within the year.

Polyperchon succeeded Antipater in 319 BC as regent, but Antipater's son Cassander established Philip II's son Philip III (Arrhidaeus) as king and forced Polyperchon out of Macedonia. He fled to Epirus, taking Roxana and her son Alexander IV with him, who had previously been left in the care of Olympias. At the beginning, Olympias had not been involved in this conflict, but she soon realized that in the case of Cassander's rule, her grandson would lose the crown, so she allied with Polyperchon in 317 BC. The Macedonian soldiers supported her return and the united armies of Polyperchon and Olympias, with the house of Aeacides, invaded Macedonia to drive Cassander out from power.

After winning in battle by convincing the army of Adea Eurydice, the wife of Philip III, to side with her own, Olympias captured and executed the two in October 317 BC. She also captured Cassander's brother and a hundred of his partisans. Cassander soon blockaded and besieged Olympias in Pydna and one of the terms of the capitulation had been that Olympias's life would be saved, but Cassander had decided to execute her, sparing only temporarily the lives of Roxana and Alexander IV (they were executed a few years later in 309 BC). When the fortress of Pydna fell, Cassander ordered Olympias killed, but the soldiers refused to harm the mother of Alexander the Great. In the end, the families of her many victims stoned her to death with the approval of Cassander, who is also said to have denied to her body the rites of burial.

(Source:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olympias)

More:

https://www.ancient.eu/Olympias/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/...

https://www.livius.org/articles/perso...

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/hi...

https://www.thoughtco.com/queen-olymp...

by Elizabeth Carney (no photo)

by Elizabeth Carney (no photo) by Sharon L. James (no photo)

by Sharon L. James (no photo) by Books LLC (no photo)

by Books LLC (no photo) by Guida M. Jackson (no photo)

by Guida M. Jackson (no photo) by Michael A. Dimitri (no photo)

by Michael A. Dimitri (no photo)

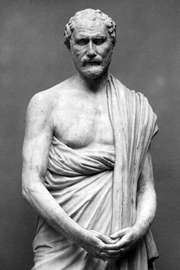

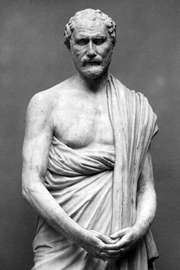

Aristotle

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) made significant and lasting contributions to nearly every aspect of human knowledge, from logic to biology to ethics and aesthetics. Though overshadowed in classical times by the work of his teacher Plato, from late antiquity through the Enlightenment, Aristotle’s surviving writings were incredibly influential. In Arabic philosophy, he was known simply as “The First Teacher”; in the West, he was “The Philosopher.”

Aristotle’s Early Life

Aristotle was born in 384 B.C. in Stagira in northern Greece. Both of his parents were members of traditional medical families, and his father, Nicomachus, served as court physician to King Amyntus III of Macedonia. His parents died while he was young, and he was likely raised at his family’s home in Stagira. At age 17 he was sent to Athens to enroll in Plato's Academy. He spent 20 years as a student and teacher at the school, emerging with both a great respect and a good deal of criticism for his teacher’s theories. Plato’s own later writings, in which he softened some earlier positions, likely bear the mark of repeated discussions with his most gifted student.

When Plato died in 347, control of the Academy passed to his nephew Speusippus. Aristotle left Athens soon after, though it is not clear whether frustrations at the Academy or political difficulties due to his family’s Macedonian connections hastened his exit. He spent five years on the coast of Asia Minor as a guest of former students at Assos and Lesbos. It was here that he undertook his pioneering research into marine biology and married his wife Pythias, with whom he had his only daughter, also named Pythias.

In 342 Aristotle was summoned to Macedonia by King Philip II to tutor his son, the future Alexander the Great—a meeting of great historical figures that, in the words of one modern commentator, “made remarkably little impact on either of them.”

Aristotle and the Lyceum

Aristotle returned to Athens in 335 B.C. As an alien, he couldn’t own property, so he rented space in the Lyceum, a former wrestling school outside the city. Like Plato’s Academy, the Lyceum attracted students from throughout the Greek world and developed a curriculum centered on its founder’s teachings. In accordance with Aristotle’s principle of surveying the writings of others as part of the philosophical process, the Lyceum assembled a collection of manuscripts that comprised one of the world’s first great libraries.

Aristotle’s Works

It was at the Lyceum that Aristotle probably composed most of his approximately 200 works, of which only 31 survive. In style, his known works are dense and almost jumbled, suggesting that they were lecture notes for internal use at his school. The surviving works of Aristotle are grouped into four categories. The “Organon” is a set of writings that provide a logical toolkit for use in any philosophical or scientific investigation. Next come Aristotle’s theoretical works, most famously his treatises on animals (“Parts of Animals,” “Movement of Animals,” etc.), cosmology, the “Physics” (a basic inquiry about the nature of matter and change) and the “Metaphysics” (a quasi-theological investigation of existence itself).

Third are Aristotle’s so-called practical works, notably the “Nicomachean Ethics” and “Politics,” both deep investigations into the nature of human flourishing on the individual, familial and societal levels. Finally, his “Rhetoric” and “Poetics” examine the finished products of human productivity, including what makes for a convincing argument and how a well-wrought tragedy can instill cathartic fear and pity.

The Organon

“The Organon” (Latin for “instrument”) is a series of Aristotle’s works on logic (what he himself would call analytics) put together around 40 B.C. by Andronicus of Rhodes and his followers. The set of six books includes “Categories,” “On Interpretation,” “Prior Analytics,” “Posterior Analytics,” “Topics,” and “On Sophistical Refutations.” The Organon contains Aristotle’s worth on syllogisms (from the Greek syllogismos, or “conclusions”), a form of reasoning in which a conclusion is drawn from two assumed premises. For example, all men are mortal, all Greeks are men, therefore all Greeks are mortal.

Metaphysics

Aristotle’s “Metaphysics,” written quite literally after his “Physics,” studies the nature of existence. He called metaphysics the “first philosophy,” or “wisdom.” His primary area of focus was “being qua being,” which examined what can be said about being based on what it is, not because of any particular qualities it may have. In “Metaphysics,” Aristotle also muses on causation, form, matter and even a logic-based argument for the existence of God.

Rhetoric

To Aristotle, rhetoric is “the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion.” He identified three main methods of rhetoric: ethos (ethics), pathos (emotional), and logos (logic). He also broke rhetoric into types of speeches: epideictic (ceremonial), forensic (judicial) and deliberative (where the audience is required to reach a verdict). His groundbreaking work in this field earned him the nickname “the father of rhetoric.”

Poetics

Aristotle’s “Poetics” was composed around 330 B.C. and is the earliest extant work of dramatic theory. It is often interpreted as a rebuttal to his teacher Plato’s argument that poetry is morally suspect and should therefore be expunged from a perfect society. Aristotle takes a different approach, analyzing the purpose of poetry. He argues that creative endeavors like poetry and theater provides catharsis, or the beneficial purging of emotions through art.

Aristotle’s Death and Legacy

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C., anti-Macedonian sentiment again forced Aristotle to flee Athens. He died a little north of the city in 322, of a digestive complaint. He asked to be buried next to his wife, who had died some years before. In his last years he had a relationship with his slave Herpyllis, who bore him Nicomachus, the son for whom his great ethical treatise is named.

Aristotle’s favored students took over the Lyceum, but within a few decades the school’s influence had faded in comparison to the rival Academy. For several generations Aristotle’s works were all but forgotten. The historian Strabo says they were stored for centuries in a moldy cellar in Asia Minor before their rediscovery in the first century B.C., though it is unlikely that these were the only copies.

In 30 B.C. Andronicus of Rhodes grouped and edited Aristotle’s remaining works in what became the basis for all later editions. After the fall of Rome, Aristotle was still read in Byzantium and became well-known in the Islamic world, where thinkers like Avicenna (970-1037), Averroes (1126-1204) and the Jewish scholar Maimonodes (1134-1204) revitalized Aritotle’s logical and scientific precepts.

Aristotle in the Middle Ages and Beyond

In the 13th century, Aristotle was reintroduced to the West through the work of Albertus Magnus and especially Thomas Aquinas, whose brilliant synthesis of Aristotelian and Christian thought provided a bedrock for late medieval Catholic philosophy, theology and science.

Aristotle’s universal influence waned somewhat during the Renaissance and Reformation, as religious and scientific reformers questioned the way the Catholic Church had subsumed his precepts. Scientists like Galileo and Copernicus disproved his geocentric model of the solar system, while anatomists such as William Harvey dismantled many of his biological theories. However, even today, Aristotle’s work remains a significant starting point for any argument in the fields of logic, aesthetics, political theory and ethics.

(Source: https://www.history.com/topics/ancien...)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristotle

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ar...

https://www.britannica.com/biography/...

https://www.biography.com/scholar/ari...

https://www.ancient.eu/aristotle/

by

by

Aristotle

Aristotle

by G.E.R. Lloyd (no photo)

by G.E.R. Lloyd (no photo)

by John M. Rist (no photo)

by John M. Rist (no photo)

by Carlo Natali (no photo)

by Carlo Natali (no photo)

by Kelly Roscoe (no photo)

by Kelly Roscoe (no photo)

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) made significant and lasting contributions to nearly every aspect of human knowledge, from logic to biology to ethics and aesthetics. Though overshadowed in classical times by the work of his teacher Plato, from late antiquity through the Enlightenment, Aristotle’s surviving writings were incredibly influential. In Arabic philosophy, he was known simply as “The First Teacher”; in the West, he was “The Philosopher.”

Aristotle’s Early Life

Aristotle was born in 384 B.C. in Stagira in northern Greece. Both of his parents were members of traditional medical families, and his father, Nicomachus, served as court physician to King Amyntus III of Macedonia. His parents died while he was young, and he was likely raised at his family’s home in Stagira. At age 17 he was sent to Athens to enroll in Plato's Academy. He spent 20 years as a student and teacher at the school, emerging with both a great respect and a good deal of criticism for his teacher’s theories. Plato’s own later writings, in which he softened some earlier positions, likely bear the mark of repeated discussions with his most gifted student.

When Plato died in 347, control of the Academy passed to his nephew Speusippus. Aristotle left Athens soon after, though it is not clear whether frustrations at the Academy or political difficulties due to his family’s Macedonian connections hastened his exit. He spent five years on the coast of Asia Minor as a guest of former students at Assos and Lesbos. It was here that he undertook his pioneering research into marine biology and married his wife Pythias, with whom he had his only daughter, also named Pythias.

In 342 Aristotle was summoned to Macedonia by King Philip II to tutor his son, the future Alexander the Great—a meeting of great historical figures that, in the words of one modern commentator, “made remarkably little impact on either of them.”

Aristotle and the Lyceum

Aristotle returned to Athens in 335 B.C. As an alien, he couldn’t own property, so he rented space in the Lyceum, a former wrestling school outside the city. Like Plato’s Academy, the Lyceum attracted students from throughout the Greek world and developed a curriculum centered on its founder’s teachings. In accordance with Aristotle’s principle of surveying the writings of others as part of the philosophical process, the Lyceum assembled a collection of manuscripts that comprised one of the world’s first great libraries.

Aristotle’s Works

It was at the Lyceum that Aristotle probably composed most of his approximately 200 works, of which only 31 survive. In style, his known works are dense and almost jumbled, suggesting that they were lecture notes for internal use at his school. The surviving works of Aristotle are grouped into four categories. The “Organon” is a set of writings that provide a logical toolkit for use in any philosophical or scientific investigation. Next come Aristotle’s theoretical works, most famously his treatises on animals (“Parts of Animals,” “Movement of Animals,” etc.), cosmology, the “Physics” (a basic inquiry about the nature of matter and change) and the “Metaphysics” (a quasi-theological investigation of existence itself).

Third are Aristotle’s so-called practical works, notably the “Nicomachean Ethics” and “Politics,” both deep investigations into the nature of human flourishing on the individual, familial and societal levels. Finally, his “Rhetoric” and “Poetics” examine the finished products of human productivity, including what makes for a convincing argument and how a well-wrought tragedy can instill cathartic fear and pity.

The Organon

“The Organon” (Latin for “instrument”) is a series of Aristotle’s works on logic (what he himself would call analytics) put together around 40 B.C. by Andronicus of Rhodes and his followers. The set of six books includes “Categories,” “On Interpretation,” “Prior Analytics,” “Posterior Analytics,” “Topics,” and “On Sophistical Refutations.” The Organon contains Aristotle’s worth on syllogisms (from the Greek syllogismos, or “conclusions”), a form of reasoning in which a conclusion is drawn from two assumed premises. For example, all men are mortal, all Greeks are men, therefore all Greeks are mortal.

Metaphysics

Aristotle’s “Metaphysics,” written quite literally after his “Physics,” studies the nature of existence. He called metaphysics the “first philosophy,” or “wisdom.” His primary area of focus was “being qua being,” which examined what can be said about being based on what it is, not because of any particular qualities it may have. In “Metaphysics,” Aristotle also muses on causation, form, matter and even a logic-based argument for the existence of God.

Rhetoric

To Aristotle, rhetoric is “the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion.” He identified three main methods of rhetoric: ethos (ethics), pathos (emotional), and logos (logic). He also broke rhetoric into types of speeches: epideictic (ceremonial), forensic (judicial) and deliberative (where the audience is required to reach a verdict). His groundbreaking work in this field earned him the nickname “the father of rhetoric.”

Poetics

Aristotle’s “Poetics” was composed around 330 B.C. and is the earliest extant work of dramatic theory. It is often interpreted as a rebuttal to his teacher Plato’s argument that poetry is morally suspect and should therefore be expunged from a perfect society. Aristotle takes a different approach, analyzing the purpose of poetry. He argues that creative endeavors like poetry and theater provides catharsis, or the beneficial purging of emotions through art.

Aristotle’s Death and Legacy

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C., anti-Macedonian sentiment again forced Aristotle to flee Athens. He died a little north of the city in 322, of a digestive complaint. He asked to be buried next to his wife, who had died some years before. In his last years he had a relationship with his slave Herpyllis, who bore him Nicomachus, the son for whom his great ethical treatise is named.

Aristotle’s favored students took over the Lyceum, but within a few decades the school’s influence had faded in comparison to the rival Academy. For several generations Aristotle’s works were all but forgotten. The historian Strabo says they were stored for centuries in a moldy cellar in Asia Minor before their rediscovery in the first century B.C., though it is unlikely that these were the only copies.

In 30 B.C. Andronicus of Rhodes grouped and edited Aristotle’s remaining works in what became the basis for all later editions. After the fall of Rome, Aristotle was still read in Byzantium and became well-known in the Islamic world, where thinkers like Avicenna (970-1037), Averroes (1126-1204) and the Jewish scholar Maimonodes (1134-1204) revitalized Aritotle’s logical and scientific precepts.

Aristotle in the Middle Ages and Beyond

In the 13th century, Aristotle was reintroduced to the West through the work of Albertus Magnus and especially Thomas Aquinas, whose brilliant synthesis of Aristotelian and Christian thought provided a bedrock for late medieval Catholic philosophy, theology and science.

Aristotle’s universal influence waned somewhat during the Renaissance and Reformation, as religious and scientific reformers questioned the way the Catholic Church had subsumed his precepts. Scientists like Galileo and Copernicus disproved his geocentric model of the solar system, while anatomists such as William Harvey dismantled many of his biological theories. However, even today, Aristotle’s work remains a significant starting point for any argument in the fields of logic, aesthetics, political theory and ethics.

(Source: https://www.history.com/topics/ancien...)

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristotle

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ar...

https://www.britannica.com/biography/...

https://www.biography.com/scholar/ari...

https://www.ancient.eu/aristotle/

by

by

Aristotle

Aristotle by G.E.R. Lloyd (no photo)

by G.E.R. Lloyd (no photo) by John M. Rist (no photo)

by John M. Rist (no photo) by Carlo Natali (no photo)

by Carlo Natali (no photo) by Kelly Roscoe (no photo)

by Kelly Roscoe (no photo)

Eumenes of Cardia

Eumenes of Cardia (/juːˈmɛniːz/; Greek: Εὐμένης; c. 362 – 316 BC) was a Greek general and satrap. He participated in the Wars of the Diadochi as a supporter of the Macedonian Argead royal house. He was executed after the Battle of Gabiene in 316 BC.

Early career

Eumenes was a native of Cardia in the Thracian Chersonese, although he was suspected to be Scythian. At a very early age, he was employed as a private secretary by Philip II of Macedon and after Philip's death (336 BC) by Alexander the Great, whom he accompanied into Asia. After Alexander's death (323 BC), Eumenes took command of a large body of Greek and Macedonian soldiers fighting in support of Alexander's son, Alexander IV.

Satrap of Cappadocia and Paphlagonia (323-319 BC)

In the ensuing division of the empire in the Partition of Babylon (323 BC), Cappadocia and Paphlagonia were assigned to Eumenes; but as they were not yet subdued, Leonnatus and Antigonus were charged by Perdiccas with securing them for him. Antigonus, however, ignored the order, and Leonnatus vainly attempted to induce Eumenes to accompany him to Europe and share in his far-reaching designs. Eumenes joined Perdiccas, who installed him in Cappadocia.

Battle of the Hellespont (321 BC)

When Craterus and Antipater, having subdued Greece in the Lamian War, determined to pass into Asia and overthrow the power of Perdiccas, their first blow was aimed at Cappadocia. Craterus and Neoptolemus, the satrap of Armenia, were completely defeated by Eumenes in the Battle of the Hellespont in 321. Neoptolemus was killed, and Craterus died of his wounds.

After the death of Perdiccas

After the murder of Perdiccas in Egypt by his own soldiers (320), the Macedonian generals condemned Eumenes to death, assigning Antipater and Antigonus as his executioners. In 319 BC, Antigonus marched his army into Cappadocia and, in a lightning campaign, drove Eumenes to Nora, a strong fortress on the border between Cappadocia and Lycaonia. Here Eumenes held out for more than a year until the death of Antipater threw his opponents into disarray.

The Second War of the Diadochi

Antipater had left the regency to his friend Polyperchon instead of his son Cassander. Cassander, therefore, allied himself with Antigonus, Lysimachus and Ptolemy, while Eumenes allied himself with Polyperchon. He was able to escape from Nora through trickery and, after gathering a small army, he marched into Cilicia where he made an alliance with Antigenes and Teutamos, the commanders of the Macedonian Silver Shields and the Hypaspists. Eventually Eumenes secured control over these men by playing on their loyalty to, and superstitious awe of, Alexander. He used the royal treasury at Kyinda to recruit an army of mercenaries to add to his own troops and the

Macedonians of Antigenes and Teutamos.

In 317 BC, Eumenes left Cilicia and marched into Syria and Phoenicia, and began to raise a naval force on behalf of Polyperchon. When it was ready he sent the fleet west to reinforce Polyperchon, but it was met by Antigonus's fleet off the coast of Cilicia, and the fleet of Eumenes changed sides.

Meanwhile, Antigonus had settled his affairs in Asia Minor and marched east to take out Eumenes before he could do further damage. Eumenes somehow had advance knowledge of this and marched out of Phoenica, through Syria into Mesopotamia, with the idea of gathering support in the upper satrapies.

Eumenes in the East

Eumenes gained the support of Amphimachos, the satrap of Mesopotamia, then marched his army into Northern Babylonia, where he put them into winter quarters. During the winter he negotiated with Seleucus, the satrap of Babylonia, and Peithon, the satrap of Media, seeking their help against Antigonus. Unable to sway Seleucus and Peithon, Eumenes left his winter quarters early and marched on Susa, a major royal treasury, in Susiana. In Susa, Eumenes sent letters to all the satraps to the north and east of Susiana, ordering them in the kings' names to join him with all their forces. When the satraps joined Eumenes he had a considerable force, with which he could look forward with some confidence to doing battle against Antigonus. Eumenes then marched southeastwards into Persia, where he picked up additional reinforcements.

Antigonus, meanwhile, had reached Susa and left Seleucus there to besiege the place, while he himself marched after Eumenes. At the river Kopratas, Eumenes surprised Antigonus during the crossing of the river and killed or captured 4,000 of his men. Antigonus, faced with disaster, decided to abandon the crossing and turned back northward, marching up into Media, threatening the upper satrapies. Eumenes wanted to march westward and cut Antigonus's supply lines, but the satraps refused to abandon their satrapies and forced Eumenes to stay in the east.

In the late summer of 316 BC, Antigonus moved southward again in the hope of bringing Eumenes to battle and ending the war quickly. Eventually, the two armies met in southern Media and fought the indecisive Battle of Paraitakene. Antigonus, whose casualties were more numerous, force marched his army to safety the next night. During the winter of 316-315 BC, Antigonus tried to surprise Eumenes in Persis by marching his army across a desert and catching his enemy off guard; unfortunately, he was observed by some locals who reported it to his opponents. A few days later both armies drew up for battle. The Battle of Gabiene was as indecisive as the previous battle at Parataikene. According to Plutarch and Diodorus, Eumenes had won the battle but lost control of his army's baggage camp thanks to his ally Peucestas' duplicity or incompetence. In addition to all the loot of the Silver Shields (treasure accumulated over 30 years of successful warfare including gold, silver, gems and other booty), the soldiers' women and children were taken and Eumenes' army wished to negotiate their return.

Teutamus, one of their commanders, sent the request to Antigonus who responded by demanding they give him Eumenes. The Silver Shields complied, arrested Eumenes and his officers, and handed them over. The war was thus at an end. Eumenes was placed under guard while Antigonus held a council to ponder his fate. Antigonus, supported by his son Demetrius, was disinclined to kill Eumenes, but most of the council insisted that he execute Eumenes and so it was decided.

Death

Antigonus, according to Plutarch, starved Eumenes for three days, but finally sent an executioner to dispatch him when the time came for him to move his camp. Eumenes' body was given to his friends, to be burnt with honor, and his ashes were conveyed in a silver urn to his wife and children.

Legacy

Despite Eumenes' undeniable skills as a general, he never commanded the full allegiance of the Macedonian officers in his army and died as a result. He was an able commander who did his utmost to maintain the unity of Alexander's empire in Asia, but his efforts were frustrated by generals and satraps both nominally under his command and under that of his enemies. Eumenes was hated and despised by many fellow commanders—certainly for his successes and supposedly for his non-Macedonian (in the tribal sense) background and prior office as Royal Secretary. Eumenes has been seen as a tragic figure, a man who seemingly tried to do the right thing but was overcome by a more ruthless enemy and the treachery of his own soldiers.

(Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eumenes)

More:

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/...

https://about-history.com/the-life-of...

https://www.britannica.com/biography/...

https://www.livius.org/articles/perso...

https://dailyhistory.org/What_was_the...

(no image) Eumenes by Plutarch

Plutarch

by Edward M. Anson (no photo)

by Edward M. Anson (no photo)

by Waldemar Heckel (no photo)

by Waldemar Heckel (no photo)

by Joseph Roisman (no photo)

by Joseph Roisman (no photo)

by

by

Charles River Editors

Charles River Editors

Eumenes of Cardia (/juːˈmɛniːz/; Greek: Εὐμένης; c. 362 – 316 BC) was a Greek general and satrap. He participated in the Wars of the Diadochi as a supporter of the Macedonian Argead royal house. He was executed after the Battle of Gabiene in 316 BC.

Early career

Eumenes was a native of Cardia in the Thracian Chersonese, although he was suspected to be Scythian. At a very early age, he was employed as a private secretary by Philip II of Macedon and after Philip's death (336 BC) by Alexander the Great, whom he accompanied into Asia. After Alexander's death (323 BC), Eumenes took command of a large body of Greek and Macedonian soldiers fighting in support of Alexander's son, Alexander IV.

Satrap of Cappadocia and Paphlagonia (323-319 BC)

In the ensuing division of the empire in the Partition of Babylon (323 BC), Cappadocia and Paphlagonia were assigned to Eumenes; but as they were not yet subdued, Leonnatus and Antigonus were charged by Perdiccas with securing them for him. Antigonus, however, ignored the order, and Leonnatus vainly attempted to induce Eumenes to accompany him to Europe and share in his far-reaching designs. Eumenes joined Perdiccas, who installed him in Cappadocia.

Battle of the Hellespont (321 BC)

When Craterus and Antipater, having subdued Greece in the Lamian War, determined to pass into Asia and overthrow the power of Perdiccas, their first blow was aimed at Cappadocia. Craterus and Neoptolemus, the satrap of Armenia, were completely defeated by Eumenes in the Battle of the Hellespont in 321. Neoptolemus was killed, and Craterus died of his wounds.

After the death of Perdiccas

After the murder of Perdiccas in Egypt by his own soldiers (320), the Macedonian generals condemned Eumenes to death, assigning Antipater and Antigonus as his executioners. In 319 BC, Antigonus marched his army into Cappadocia and, in a lightning campaign, drove Eumenes to Nora, a strong fortress on the border between Cappadocia and Lycaonia. Here Eumenes held out for more than a year until the death of Antipater threw his opponents into disarray.

The Second War of the Diadochi

Antipater had left the regency to his friend Polyperchon instead of his son Cassander. Cassander, therefore, allied himself with Antigonus, Lysimachus and Ptolemy, while Eumenes allied himself with Polyperchon. He was able to escape from Nora through trickery and, after gathering a small army, he marched into Cilicia where he made an alliance with Antigenes and Teutamos, the commanders of the Macedonian Silver Shields and the Hypaspists. Eventually Eumenes secured control over these men by playing on their loyalty to, and superstitious awe of, Alexander. He used the royal treasury at Kyinda to recruit an army of mercenaries to add to his own troops and the

Macedonians of Antigenes and Teutamos.

In 317 BC, Eumenes left Cilicia and marched into Syria and Phoenicia, and began to raise a naval force on behalf of Polyperchon. When it was ready he sent the fleet west to reinforce Polyperchon, but it was met by Antigonus's fleet off the coast of Cilicia, and the fleet of Eumenes changed sides.

Meanwhile, Antigonus had settled his affairs in Asia Minor and marched east to take out Eumenes before he could do further damage. Eumenes somehow had advance knowledge of this and marched out of Phoenica, through Syria into Mesopotamia, with the idea of gathering support in the upper satrapies.

Eumenes in the East

Eumenes gained the support of Amphimachos, the satrap of Mesopotamia, then marched his army into Northern Babylonia, where he put them into winter quarters. During the winter he negotiated with Seleucus, the satrap of Babylonia, and Peithon, the satrap of Media, seeking their help against Antigonus. Unable to sway Seleucus and Peithon, Eumenes left his winter quarters early and marched on Susa, a major royal treasury, in Susiana. In Susa, Eumenes sent letters to all the satraps to the north and east of Susiana, ordering them in the kings' names to join him with all their forces. When the satraps joined Eumenes he had a considerable force, with which he could look forward with some confidence to doing battle against Antigonus. Eumenes then marched southeastwards into Persia, where he picked up additional reinforcements.

Antigonus, meanwhile, had reached Susa and left Seleucus there to besiege the place, while he himself marched after Eumenes. At the river Kopratas, Eumenes surprised Antigonus during the crossing of the river and killed or captured 4,000 of his men. Antigonus, faced with disaster, decided to abandon the crossing and turned back northward, marching up into Media, threatening the upper satrapies. Eumenes wanted to march westward and cut Antigonus's supply lines, but the satraps refused to abandon their satrapies and forced Eumenes to stay in the east.

In the late summer of 316 BC, Antigonus moved southward again in the hope of bringing Eumenes to battle and ending the war quickly. Eventually, the two armies met in southern Media and fought the indecisive Battle of Paraitakene. Antigonus, whose casualties were more numerous, force marched his army to safety the next night. During the winter of 316-315 BC, Antigonus tried to surprise Eumenes in Persis by marching his army across a desert and catching his enemy off guard; unfortunately, he was observed by some locals who reported it to his opponents. A few days later both armies drew up for battle. The Battle of Gabiene was as indecisive as the previous battle at Parataikene. According to Plutarch and Diodorus, Eumenes had won the battle but lost control of his army's baggage camp thanks to his ally Peucestas' duplicity or incompetence. In addition to all the loot of the Silver Shields (treasure accumulated over 30 years of successful warfare including gold, silver, gems and other booty), the soldiers' women and children were taken and Eumenes' army wished to negotiate their return.

Teutamus, one of their commanders, sent the request to Antigonus who responded by demanding they give him Eumenes. The Silver Shields complied, arrested Eumenes and his officers, and handed them over. The war was thus at an end. Eumenes was placed under guard while Antigonus held a council to ponder his fate. Antigonus, supported by his son Demetrius, was disinclined to kill Eumenes, but most of the council insisted that he execute Eumenes and so it was decided.

Death

Antigonus, according to Plutarch, starved Eumenes for three days, but finally sent an executioner to dispatch him when the time came for him to move his camp. Eumenes' body was given to his friends, to be burnt with honor, and his ashes were conveyed in a silver urn to his wife and children.

Legacy