The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son

>

D&S, Chp. 55-57

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 56 is titled "Several People delighted, and the Game Chicken disgusted". This Game Chicken person gets on my nerves and I'm glad to see the last of him. He seemed pointless to me, shows up with Mr. Toots now and then, says a few words some times, and disappears again for long periods of time, so why is he here at all? Well, he is finally going for good. Chapter 56 and also Chapter 57 demonstrate Dickens's ability to create balance with his writing. After the horrible death of Carker at the end of chapter 55, we begin chapter 56 "The Midshipman was alive" and it is. This chapter is alive with reunions, new beginnings, friendship, and mysteries solved. While the previous chapter was dark, cold, lonely, a chapter of one, chapter 56 is filled with people, and people who love each other, with the possible exception of that Chicken guy. As Carker was all alone on his crazy flight, now we have the opposite. In this chapter Florence is finally surrounded by those who love her. Captain Cuttle, Walter, Mr. Toots, Mrs. Toodle, Soloman Gill, Susan and most importantly, to me anyway, Diogenes are all gathered in The Midshipman, possibly the most amount of people who have ever been in the place at one time, or two. One man died in chapter 55, Dombey was left alone in chapter 55, but in chapter 56 one man comes to life, and Florence is surrounded by those who love her. Poor Dombey.

This chapter is fun, everyone that could be back is back, and everyone is happy. Except the Chicken. The days from the beginning of the chapter, when Susan and Toots arrive, until the night before the wedding is busy with family and friends. That night before we have Florence and Walter sitting together while the Captain plays cribbage with Mr. Toots who was taking suggestions from Susan, when we have this:

The Captain spoke with all composure and attention to the game, but suddenly his cards dropped out of his hand, his mouth and eyes opened wide, his legs drew themselves up and stuck out in front of his chair, and he sat staring at the door with blank amazement. Looking round upon the company, and seeing that none of them observed him or the cause of his astonishment, the Captain recovered himself with a great gasp, struck the table a tremendous blow, cried in a stentorian roar, ‘Sol Gills ahoy!’ and tumbled into the arms of a weather-beaten pea-coat that had come with Polly into the room.

In another moment, Walter was in the arms of the weather-beaten pea-coat. In another moment, Florence was in the arms of the weather-beaten pea-coat. In another moment, Captain Cuttle had embraced Mrs Richards and Miss Nipper, and was violently shaking hands with Mr Toots, exclaiming, as he waved his hook above his head, ‘Hooroar, my lad, hooroar!’ To which Mr Toots, wholly at a loss to account for these proceedings, replied with great politeness, ‘Certainly, Captain Gills, whatever you think proper!’

The weather-beaten pea-coat, and a no less weather-beaten cap and comforter belonging to it, turned from the Captain and from Florence back to Walter, and sounds came from the weather-beaten pea-coat, cap, and comforter, as of an old man sobbing underneath them; while the shaggy sleeves clasped Walter tight. During this pause, there was an universal silence, and the Captain polished his nose with great diligence. But when the pea-coat, cap, and comforter lifted themselves up again, Florence gently moved towards them; and she and Walter taking them off, disclosed the old Instrument-maker, a little thinner and more careworn than of old, in his old Welsh wig and his old coffee-coloured coat and basket buttons, with his old infallible chronometer ticking away in his pocket.

Yes Sol Gills has arrived home just in time for the wedding. Sol, who everyone has assumed was dead since they have never heard from him. Although Sol Gills confuses them all by asking the Captain why he never wrote to him:

‘Although I have heard something of the changes of events, from her,’ resumed the Instrument-maker, taking his old spectacles from his pocket, and putting them on his forehead in his old manner, ‘they are so great and unexpected, and I am so overpowered by the sight of my dear boy, and by the,’—glancing at the downcast eyes of Florence, and not attempting to finish the sentence—‘that I—I can’t say much to-night. But my dear Ned Cuttle, why didn’t you write?’

The astonishment depicted in the Captain’s features positively frightened Mr Toots, whose eyes were quite fixed by it, so that he could not withdraw them from his face.

‘Write!’ echoed the Captain. ‘Write, Sol Gills?’

‘Ay,’ said the old man, ‘either to Barbados, or Jamaica, or Demerara, that was what I asked.’

‘What you asked, Sol Gills?’ repeated the Captain.

‘Ay,’ said the old man. ‘Don’t you know, Ned? Sure you have not forgotten? Every time I wrote to you.’

The Captain took off his glazed hat, hung it on his hook, and smoothing his hair from behind with his hand, sat gazing at the group around him: a perfect image of wondering resignation.

‘You don’t appear to understand me, Ned!’ observed old Sol.

‘Sol Gills,’ returned the Captain, after staring at him and the rest for a long time, without speaking, ‘I’m gone about and adrift. Pay out a word or two respecting them adwenturs, will you! Can’t I bring up, nohows? Nohows?’ said the Captain, ruminating, and staring all round.

It seems old Sol has been writing to the Captain all along, but the Captain has never received one letter. We find out that Sol has been sending his letters to Number nine Brig Place, the home of Mrs. MacStinger and as we all know, former home of the Captain. The Captain tells them that he "cut and run" from there and no one knew where he had gone. He says he had to do that because if Mrs. MacStinger had known where he was going, she would never have allowed him to leave. But some time ago, I can't remember when, she did find out where he was, and was taken home by Bunsby. So I wonder what happened to the letters? It doesn't matter anymore, old Sol is home and just in time for the wedding. How's that for timing? And now it's time to finally get rid of the Chicken once and for all:

‘Now, Master,’ said the Chicken, doggedly, when he, at length, caught Mr Toots’s eye, ‘I want to know whether this here gammon is to finish it, or whether you’re a going in to win?’

‘Chicken,’ returned Mr Toots, ‘explain yourself.’

‘Why then, here’s all about it, Master,’ said the Chicken. ‘I ain’t a cove to chuck a word away. Here’s wot it is. Are any on ‘em to be doubled up?’

When the Chicken put this question he dropped his hat, made a dodge and a feint with his left hand, hit a supposed enemy a violent blow with his right, shook his head smartly, and recovered himself.

‘Come, Master,’ said the Chicken. ‘Is it to be gammon or pluck? Which?’

‘Chicken,’ returned Mr Toots, ‘your expressions are coarse, and your meaning is obscure.’

‘Why, then, I tell you what, Master,’ said the Chicken. ‘This is where it is. It’s mean.’

‘What is mean, Chicken?’ asked Mr Toots.

‘It is,’ said the Chicken, with a frightful corrugation of his broken nose. ‘There! Now, Master! Wot! When you could go and blow on this here match to the stiff’un;’ by which depreciatory appellation it has been since supposed that the Game One intended to signify Mr Dombey; ‘and when you could knock the winner and all the kit of ‘em dead out o’ wind and time, are you going to give in? To give in?’ said the Chicken, with contemptuous emphasis. ‘Wy, it’s mean!’

‘Chicken,’ said Mr Toots, severely, ‘you’re a perfect Vulture! Your sentiments are atrocious.’

‘My sentiments is Game and Fancy, Master,’ returned the Chicken. ‘That’s wot my sentiments is. I can’t abear a meanness. I’m afore the public, I’m to be heerd on at the bar of the Little Helephant, and no Gov’ner o’ mine mustn’t go and do what’s mean. Wy, it’s mean,’ said the Chicken, with increased expression. ‘That’s where it is. It’s mean.’

‘Chicken,’ said Mr Toots, ‘you disgust me.’

‘Master,’ returned the Chicken, putting on his hat, ‘there’s a pair on us, then. Come! Here’s a offer! You’ve spoke to me more than once’t or twice’t about the public line. Never mind! Give me a fi’typunnote to-morrow, and let me go.’

‘Chicken,’ returned Mr Toots, ‘after the odious sentiments you have expressed, I shall be glad to part on such terms.’

‘Done then,’ said the Chicken. ‘It’s a bargain. This here conduct of yourn won’t suit my book, Master. Wy, it’s mean,’ said the Chicken; who seemed equally unable to get beyond that point, and to stop short of it. ‘That’s where it is; it’s mean!’

So Mr Toots and the Chicken agreed to part on this incompatibility of moral perception; and Mr Toots lying down to sleep, dreamed happily of Florence, who had thought of him as her friend upon the last night of her maiden life, and who had sent him her dear love.

This chapter is fun, everyone that could be back is back, and everyone is happy. Except the Chicken. The days from the beginning of the chapter, when Susan and Toots arrive, until the night before the wedding is busy with family and friends. That night before we have Florence and Walter sitting together while the Captain plays cribbage with Mr. Toots who was taking suggestions from Susan, when we have this:

The Captain spoke with all composure and attention to the game, but suddenly his cards dropped out of his hand, his mouth and eyes opened wide, his legs drew themselves up and stuck out in front of his chair, and he sat staring at the door with blank amazement. Looking round upon the company, and seeing that none of them observed him or the cause of his astonishment, the Captain recovered himself with a great gasp, struck the table a tremendous blow, cried in a stentorian roar, ‘Sol Gills ahoy!’ and tumbled into the arms of a weather-beaten pea-coat that had come with Polly into the room.

In another moment, Walter was in the arms of the weather-beaten pea-coat. In another moment, Florence was in the arms of the weather-beaten pea-coat. In another moment, Captain Cuttle had embraced Mrs Richards and Miss Nipper, and was violently shaking hands with Mr Toots, exclaiming, as he waved his hook above his head, ‘Hooroar, my lad, hooroar!’ To which Mr Toots, wholly at a loss to account for these proceedings, replied with great politeness, ‘Certainly, Captain Gills, whatever you think proper!’

The weather-beaten pea-coat, and a no less weather-beaten cap and comforter belonging to it, turned from the Captain and from Florence back to Walter, and sounds came from the weather-beaten pea-coat, cap, and comforter, as of an old man sobbing underneath them; while the shaggy sleeves clasped Walter tight. During this pause, there was an universal silence, and the Captain polished his nose with great diligence. But when the pea-coat, cap, and comforter lifted themselves up again, Florence gently moved towards them; and she and Walter taking them off, disclosed the old Instrument-maker, a little thinner and more careworn than of old, in his old Welsh wig and his old coffee-coloured coat and basket buttons, with his old infallible chronometer ticking away in his pocket.

Yes Sol Gills has arrived home just in time for the wedding. Sol, who everyone has assumed was dead since they have never heard from him. Although Sol Gills confuses them all by asking the Captain why he never wrote to him:

‘Although I have heard something of the changes of events, from her,’ resumed the Instrument-maker, taking his old spectacles from his pocket, and putting them on his forehead in his old manner, ‘they are so great and unexpected, and I am so overpowered by the sight of my dear boy, and by the,’—glancing at the downcast eyes of Florence, and not attempting to finish the sentence—‘that I—I can’t say much to-night. But my dear Ned Cuttle, why didn’t you write?’

The astonishment depicted in the Captain’s features positively frightened Mr Toots, whose eyes were quite fixed by it, so that he could not withdraw them from his face.

‘Write!’ echoed the Captain. ‘Write, Sol Gills?’

‘Ay,’ said the old man, ‘either to Barbados, or Jamaica, or Demerara, that was what I asked.’

‘What you asked, Sol Gills?’ repeated the Captain.

‘Ay,’ said the old man. ‘Don’t you know, Ned? Sure you have not forgotten? Every time I wrote to you.’

The Captain took off his glazed hat, hung it on his hook, and smoothing his hair from behind with his hand, sat gazing at the group around him: a perfect image of wondering resignation.

‘You don’t appear to understand me, Ned!’ observed old Sol.

‘Sol Gills,’ returned the Captain, after staring at him and the rest for a long time, without speaking, ‘I’m gone about and adrift. Pay out a word or two respecting them adwenturs, will you! Can’t I bring up, nohows? Nohows?’ said the Captain, ruminating, and staring all round.

It seems old Sol has been writing to the Captain all along, but the Captain has never received one letter. We find out that Sol has been sending his letters to Number nine Brig Place, the home of Mrs. MacStinger and as we all know, former home of the Captain. The Captain tells them that he "cut and run" from there and no one knew where he had gone. He says he had to do that because if Mrs. MacStinger had known where he was going, she would never have allowed him to leave. But some time ago, I can't remember when, she did find out where he was, and was taken home by Bunsby. So I wonder what happened to the letters? It doesn't matter anymore, old Sol is home and just in time for the wedding. How's that for timing? And now it's time to finally get rid of the Chicken once and for all:

‘Now, Master,’ said the Chicken, doggedly, when he, at length, caught Mr Toots’s eye, ‘I want to know whether this here gammon is to finish it, or whether you’re a going in to win?’

‘Chicken,’ returned Mr Toots, ‘explain yourself.’

‘Why then, here’s all about it, Master,’ said the Chicken. ‘I ain’t a cove to chuck a word away. Here’s wot it is. Are any on ‘em to be doubled up?’

When the Chicken put this question he dropped his hat, made a dodge and a feint with his left hand, hit a supposed enemy a violent blow with his right, shook his head smartly, and recovered himself.

‘Come, Master,’ said the Chicken. ‘Is it to be gammon or pluck? Which?’

‘Chicken,’ returned Mr Toots, ‘your expressions are coarse, and your meaning is obscure.’

‘Why, then, I tell you what, Master,’ said the Chicken. ‘This is where it is. It’s mean.’

‘What is mean, Chicken?’ asked Mr Toots.

‘It is,’ said the Chicken, with a frightful corrugation of his broken nose. ‘There! Now, Master! Wot! When you could go and blow on this here match to the stiff’un;’ by which depreciatory appellation it has been since supposed that the Game One intended to signify Mr Dombey; ‘and when you could knock the winner and all the kit of ‘em dead out o’ wind and time, are you going to give in? To give in?’ said the Chicken, with contemptuous emphasis. ‘Wy, it’s mean!’

‘Chicken,’ said Mr Toots, severely, ‘you’re a perfect Vulture! Your sentiments are atrocious.’

‘My sentiments is Game and Fancy, Master,’ returned the Chicken. ‘That’s wot my sentiments is. I can’t abear a meanness. I’m afore the public, I’m to be heerd on at the bar of the Little Helephant, and no Gov’ner o’ mine mustn’t go and do what’s mean. Wy, it’s mean,’ said the Chicken, with increased expression. ‘That’s where it is. It’s mean.’

‘Chicken,’ said Mr Toots, ‘you disgust me.’

‘Master,’ returned the Chicken, putting on his hat, ‘there’s a pair on us, then. Come! Here’s a offer! You’ve spoke to me more than once’t or twice’t about the public line. Never mind! Give me a fi’typunnote to-morrow, and let me go.’

‘Chicken,’ returned Mr Toots, ‘after the odious sentiments you have expressed, I shall be glad to part on such terms.’

‘Done then,’ said the Chicken. ‘It’s a bargain. This here conduct of yourn won’t suit my book, Master. Wy, it’s mean,’ said the Chicken; who seemed equally unable to get beyond that point, and to stop short of it. ‘That’s where it is; it’s mean!’

So Mr Toots and the Chicken agreed to part on this incompatibility of moral perception; and Mr Toots lying down to sleep, dreamed happily of Florence, who had thought of him as her friend upon the last night of her maiden life, and who had sent him her dear love.

Chapter 57 is titled Another Wedding and we start in the fine, cold church where Mr. Dombey was married. On their marriage morning Florence and Walter walk to this church, but not to be married, but to visit the resting place of her brother Paul. Then there is more walking reminding me of that first walk they took through the city so long ago:

‘It is very early, Walter, and the streets are almost empty yet. Let us walk.’

‘But you will be so tired, my love.’

‘Oh no! I was very tired the first time that we ever walked together, but I shall not be so to-day.’

And thus—not much changed—she, as innocent and earnest-hearted—he, as frank, as hopeful, and more proud of her—Florence and Walter, on their bridal morning, walk through the streets together.

Not even in that childish walk of long ago, were they so far removed from all the world about them as to-day. The childish feet of long ago, did not tread such enchanted ground as theirs do now. The confidence and love of children may be given many times, and will spring up in many places; but the woman’s heart of Florence, with its undivided treasure, can be yielded only once, and under slight or change, can only droop and die.

They take the streets that are the quietest, and do not go near that in which her old home stands. It is a fair, warm summer morning, and the sun shines on them, as they walk towards the darkening mist that overspreads the City. Riches are uncovering in shops; jewels, gold, and silver flash in the goldsmith’s sunny windows; and great houses cast a stately shade upon them as they pass. But through the light, and through the shade, they go on lovingly together, lost to everything around; thinking of no other riches, and no prouder home, than they have now in one another.

The people with no money seem to be happier than the people with all the money in this book. Perhaps in all Dickens' books, I'm not sure. And now we come to the wedding to see Florence and Walter become man and wife. The Captain, Uncle Sol, and Mr. Toots have come, Susan Nipper is there, and that is all, a very small, quiet wedding. And now it's time for the young couple to go, Susan is sobbing and Mr. Toots comes forward, urges her to cheer up, and takes charge of her. Florence gives poor Toots a kiss, then Uncle Sol, and the Captain, and Florence and Walter are gone. All their things have been boarded on the ship, and everything is ready for their trip. Later, we find that Walter has left a letter for Mr. Dombey to be sent in three weeks' time. Sol reads it to them:

‘“Sir. I am married to your daughter. She is gone with me upon a distant voyage. To be devoted to her is to have no claim on her or you, but God knows that I am.

‘“Why, loving her beyond all earthly things, I have yet, without remorse, united her to the uncertainties and dangers of my life, I will not say to you. You know why, and you are her father.

‘“Do not reproach her. She has never reproached you.

‘“I do not think or hope that you will ever forgive me. There is nothing I expect less. But if an hour should come when it will comfort you to believe that Florence has someone ever near her, the great charge of whose life is to cancel her remembrance of past sorrow, I solemnly assure you, you may, in that hour, rest in that belief.”’

I wonder if her father will care. I wonder how long she was gone before he noticed. For now, they put that last bottle of Madeira back again, it isn't time to open it. As for the newly married couple:

A few days have elapsed, and a stately ship is out at sea, spreading its white wings to the favouring wind.

Upon the deck, image to the roughest man on board of something that is graceful, beautiful, and harmless—something that it is good and pleasant to have there, and that should make the voyage prosperous—is Florence. It is night, and she and Walter sit alone, watching the solemn path of light upon the sea between them and the moon.

At length she cannot see it plainly, for the tears that fill her eyes; and then she lays her head down on his breast, and puts her arms around his neck, saying, ‘Oh Walter, dearest love, I am so happy!’

Her husband holds her to his heart, and they are very quiet, and the stately ship goes on serenely.

‘As I hear the sea,’ says Florence, ‘and sit watching it, it brings so many days into my mind. It makes me think so much—’

‘Of Paul, my love. I know it does.’

Of Paul and Walter. And the voices in the waves are always whispering to Florence, in their ceaseless murmuring, of love—of love, eternal and illimitable, not bounded by the confines of this world, or by the end of time, but ranging still, beyond the sea, beyond the sky, to the invisible country far away!

And that leaves Florence happy with a husband she loves and one that adores her. And Dombey sits alone in the dark, a long time ago he tried to tell Paul money was the most important thing. I wonder if he still feels that way. And what does he miss more now, the money, his son, or the one person that loved him most of all? Between this, Edith, and the train, I say - poor Dombey.

‘It is very early, Walter, and the streets are almost empty yet. Let us walk.’

‘But you will be so tired, my love.’

‘Oh no! I was very tired the first time that we ever walked together, but I shall not be so to-day.’

And thus—not much changed—she, as innocent and earnest-hearted—he, as frank, as hopeful, and more proud of her—Florence and Walter, on their bridal morning, walk through the streets together.

Not even in that childish walk of long ago, were they so far removed from all the world about them as to-day. The childish feet of long ago, did not tread such enchanted ground as theirs do now. The confidence and love of children may be given many times, and will spring up in many places; but the woman’s heart of Florence, with its undivided treasure, can be yielded only once, and under slight or change, can only droop and die.

They take the streets that are the quietest, and do not go near that in which her old home stands. It is a fair, warm summer morning, and the sun shines on them, as they walk towards the darkening mist that overspreads the City. Riches are uncovering in shops; jewels, gold, and silver flash in the goldsmith’s sunny windows; and great houses cast a stately shade upon them as they pass. But through the light, and through the shade, they go on lovingly together, lost to everything around; thinking of no other riches, and no prouder home, than they have now in one another.

The people with no money seem to be happier than the people with all the money in this book. Perhaps in all Dickens' books, I'm not sure. And now we come to the wedding to see Florence and Walter become man and wife. The Captain, Uncle Sol, and Mr. Toots have come, Susan Nipper is there, and that is all, a very small, quiet wedding. And now it's time for the young couple to go, Susan is sobbing and Mr. Toots comes forward, urges her to cheer up, and takes charge of her. Florence gives poor Toots a kiss, then Uncle Sol, and the Captain, and Florence and Walter are gone. All their things have been boarded on the ship, and everything is ready for their trip. Later, we find that Walter has left a letter for Mr. Dombey to be sent in three weeks' time. Sol reads it to them:

‘“Sir. I am married to your daughter. She is gone with me upon a distant voyage. To be devoted to her is to have no claim on her or you, but God knows that I am.

‘“Why, loving her beyond all earthly things, I have yet, without remorse, united her to the uncertainties and dangers of my life, I will not say to you. You know why, and you are her father.

‘“Do not reproach her. She has never reproached you.

‘“I do not think or hope that you will ever forgive me. There is nothing I expect less. But if an hour should come when it will comfort you to believe that Florence has someone ever near her, the great charge of whose life is to cancel her remembrance of past sorrow, I solemnly assure you, you may, in that hour, rest in that belief.”’

I wonder if her father will care. I wonder how long she was gone before he noticed. For now, they put that last bottle of Madeira back again, it isn't time to open it. As for the newly married couple:

A few days have elapsed, and a stately ship is out at sea, spreading its white wings to the favouring wind.

Upon the deck, image to the roughest man on board of something that is graceful, beautiful, and harmless—something that it is good and pleasant to have there, and that should make the voyage prosperous—is Florence. It is night, and she and Walter sit alone, watching the solemn path of light upon the sea between them and the moon.

At length she cannot see it plainly, for the tears that fill her eyes; and then she lays her head down on his breast, and puts her arms around his neck, saying, ‘Oh Walter, dearest love, I am so happy!’

Her husband holds her to his heart, and they are very quiet, and the stately ship goes on serenely.

‘As I hear the sea,’ says Florence, ‘and sit watching it, it brings so many days into my mind. It makes me think so much—’

‘Of Paul, my love. I know it does.’

Of Paul and Walter. And the voices in the waves are always whispering to Florence, in their ceaseless murmuring, of love—of love, eternal and illimitable, not bounded by the confines of this world, or by the end of time, but ranging still, beyond the sea, beyond the sky, to the invisible country far away!

And that leaves Florence happy with a husband she loves and one that adores her. And Dombey sits alone in the dark, a long time ago he tried to tell Paul money was the most important thing. I wonder if he still feels that way. And what does he miss more now, the money, his son, or the one person that loved him most of all? Between this, Edith, and the train, I say - poor Dombey.

Back to the Chicken for a minute. I don't understand him, why is he here, what does he want, what is his purpose in the book at all? I am certainly glad to see him go, but I'm not sure what he was there for from the beginning.

Kim wrote: "But some time ago, I can't remember when, she did find out where he was, and was taken home by Bunsby."

Kim wrote: "But some time ago, I can't remember when, she did find out where he was, and was taken home by Bunsby."I'm glad you mentioned that because I thought I'd imagined it. Maybe Dickens forgot that scene?

Kim wrote: "Between this, Edith, and the train, I say - poor Dombey."

Kim wrote: "Between this, Edith, and the train, I say - poor Dombey."You are very kind and no doubt right, but I find myself mostly resenting that they're probably saving that Madeira for Dombey to come around, and I don't think he deserves it one bit.

But I guess we don't always get what we deserve.

Kim wrote: "Back to the Chicken for a minute. I don't understand him, why is he here, what does he want, what is his purpose in the book at all? I am certainly glad to see him go, but I'm not sure what he was ..."

I think he was not a real person, but a part of Toots. The part of him that was jealous, that wanted to boast his wealth, that wanted to win Florence over instead of not begrudging her the life with the man she loves most. The way Toots is, I think he needed this separate persona to distance himself from these feelings, because he didn't want to be that person. And realising Florence would get married to Walter anyway, he had a hard time, but in the end he managed to get rid of his jealousy and anger about it and be the happier man for it.

That the Chicken only 'talked' when Toots was alone, and no one seemed to acknowledge him in any way except Toots, strengthens this for me. There was no mention of him in all of that chapter, until Toots was home, while Dickens always gives everyone a place, even the dog. Still, he had appeared to be there. And where Toots was very restless in church the morning before - and very restless anyway, having to get out several times to compose himself - he was a different man in that regard the day of the wedding. He was there for The Nipper, he was calm, etc. As if he got rid of his restlessness somehow ...

ETA I had this nagging feeling about the Chicken not being a real person and being a part of Toots all along, but after chapter 56 I am quite sure of it.

I think he was not a real person, but a part of Toots. The part of him that was jealous, that wanted to boast his wealth, that wanted to win Florence over instead of not begrudging her the life with the man she loves most. The way Toots is, I think he needed this separate persona to distance himself from these feelings, because he didn't want to be that person. And realising Florence would get married to Walter anyway, he had a hard time, but in the end he managed to get rid of his jealousy and anger about it and be the happier man for it.

That the Chicken only 'talked' when Toots was alone, and no one seemed to acknowledge him in any way except Toots, strengthens this for me. There was no mention of him in all of that chapter, until Toots was home, while Dickens always gives everyone a place, even the dog. Still, he had appeared to be there. And where Toots was very restless in church the morning before - and very restless anyway, having to get out several times to compose himself - he was a different man in that regard the day of the wedding. He was there for The Nipper, he was calm, etc. As if he got rid of his restlessness somehow ...

ETA I had this nagging feeling about the Chicken not being a real person and being a part of Toots all along, but after chapter 56 I am quite sure of it.

The darkness of chapter 55 was wonderful in my opinion. Carker clearly was a man who 'snapped'. He turned out to be just as prideful as Dombey was, although his pride was turned towards not his family, firm and 'how things should be', but towards how he could get his way and screw people for that. With women, with Dombey, everyone did his bidding because he was so smart, he told himself. And then first Edith did not do his bidding at all, but used him instead of him using her, and then Dombey came into the picture being rightfully angry with him. I think at that moment Carker had everything he prided himself for taken from under his feet. He was not on the run for Dombey, or for the police - he was on the run for facing that he had no reason to be proud anymore, facing that all of his schemes fell through. It read like the flight of a madman, and I think that is exactly what he had become. The appearance of Dombey and the flight of Edith were relatively small, but those things tipped him over the edge. For some people it's a fine line between keeping it all together and becoming stark raving mad.

I think the night at the railway was part foreshadowing of Carker's death, and part pointing out even more how mad he had become. It read to me like Carker was already thinking of taking his own life, or seeing that as a possibility.

Also, Carker's last moments did give Dombey a bit of humanity back. As disgusted and angry as he was, the look on his face when he realised the train was coming made clear that in the end he did not want Carker to die. At least not in such a horrible way. No matter how much Carker had wounded his pride. I noticed that I gained a bit of hope back that Dombey might become a better person, even if he has to hit rock bottom for that.

I think the night at the railway was part foreshadowing of Carker's death, and part pointing out even more how mad he had become. It read to me like Carker was already thinking of taking his own life, or seeing that as a possibility.

Also, Carker's last moments did give Dombey a bit of humanity back. As disgusted and angry as he was, the look on his face when he realised the train was coming made clear that in the end he did not want Carker to die. At least not in such a horrible way. No matter how much Carker had wounded his pride. I noticed that I gained a bit of hope back that Dombey might become a better person, even if he has to hit rock bottom for that.

Jantine wrote: "I think he was not a real person, but a part of Toots. The part of him that was jealous, that wanted to boast his wealth, that wanted to win Florence over instead of not begrudging her the life with the man she loves most."

Jantine wrote: "I think he was not a real person, but a part of Toots. The part of him that was jealous, that wanted to boast his wealth, that wanted to win Florence over instead of not begrudging her the life with the man she loves most."Oh, that makes so much sense, even if the Chicken isn't literally a figment of Toots's imagination, since Captain Cuttle does serve him a drink at one point--although who knows, maybe he's just humoring Toots and serving Toots a drink. But I don't think it has to be literal to work.

I found myself very pleased with Toots in this installment and I think it was because although he's not the first unqualified young man to fall in love with a Dickens heroine, he doesn't die. He goes on living and being useful. It's extraordinarily selfless.

Also I am glad he and Walter appreciate each other.

Jantine wrote: "Kim wrote: "Back to the Chicken for a minute. I don't understand him, why is he here, what does he want, what is his purpose in the book at all? I am certainly glad to see him go, but I'm not sure ..."

Hi Jantine

Wow. I never thought about the possibility that The Game Chicken could just be a figment of Toots’s over-active imagination. I agree with Julie that the Chicken does not have to be literally a figment of an active imagination but your comment has given me lots to think about.

The Game Chicken could be a form of doppelgänger. He is everything that Toots is not. The Chicken is tough, sturdy, aggressive, a lower class survivor, a person with an edgy speech pattern ... heck, the Chicken is everything Toots is not. What a persona for a person to create to protect and shield a more delicate person. The Chicken is a perfect mask or projection, an inner wish projected to society. Carl Jung termed this projection a mask.

In fact, could it be that Dickens is also having some fun with the name. The word “chicken” has a negative connotation when applied to a person. If we add the word “game” to chicken we can see how the particular chicken who accompanies Toots is willing to play the game of societal expectations.

Hi Jantine

Wow. I never thought about the possibility that The Game Chicken could just be a figment of Toots’s over-active imagination. I agree with Julie that the Chicken does not have to be literally a figment of an active imagination but your comment has given me lots to think about.

The Game Chicken could be a form of doppelgänger. He is everything that Toots is not. The Chicken is tough, sturdy, aggressive, a lower class survivor, a person with an edgy speech pattern ... heck, the Chicken is everything Toots is not. What a persona for a person to create to protect and shield a more delicate person. The Chicken is a perfect mask or projection, an inner wish projected to society. Carl Jung termed this projection a mask.

In fact, could it be that Dickens is also having some fun with the name. The word “chicken” has a negative connotation when applied to a person. If we add the word “game” to chicken we can see how the particular chicken who accompanies Toots is willing to play the game of societal expectations.

I don't doubt that Dickens had some fun with the name at all :-D

Thinking about Carker's now spread around teeth, I decided to look up some symbolism of teeth. I came across this site:

http://www.biblemeanings.info/Words/B...

I think it is quite interesting to have it next to this story, Carker being the one who prepared all information before it got to Dombey and who influenced every bit of Dombey's behaviour - before running away Dombey did everything Carker said, Carker was the one bringing messages from Florence and the firm's papers to Dombey while he was in Brighton. After the Edith running away-debacle he was driven by his hate for Carker. The other way around too, Carker often being his spokesperson towards Edith, and towards the firm. So he was the set of teeth that grinded and prepared, and so defined how Dombey was nourished.

In that case I am even more curious how Dombey will develop when he will not be nourished by Carker anymore - because that set of teeth has been shattered, 'whirled away upon a jagged mill' as Dickens closed the circle around the symbolism of Carker's teeth.

Thinking about Carker's now spread around teeth, I decided to look up some symbolism of teeth. I came across this site:

http://www.biblemeanings.info/Words/B...

I think it is quite interesting to have it next to this story, Carker being the one who prepared all information before it got to Dombey and who influenced every bit of Dombey's behaviour - before running away Dombey did everything Carker said, Carker was the one bringing messages from Florence and the firm's papers to Dombey while he was in Brighton. After the Edith running away-debacle he was driven by his hate for Carker. The other way around too, Carker often being his spokesperson towards Edith, and towards the firm. So he was the set of teeth that grinded and prepared, and so defined how Dombey was nourished.

In that case I am even more curious how Dombey will develop when he will not be nourished by Carker anymore - because that set of teeth has been shattered, 'whirled away upon a jagged mill' as Dickens closed the circle around the symbolism of Carker's teeth.

Hi Jantine

Yes. I see how Carker’s teeth can be expanded beyond that as solely portraying an aggressive ripping, tearing projection. He does, as you say, both prepare and grind information for consumption.

I found Carker to be a very interesting psychological study. Did you find Carker’s treatment and comments towards his brother helped the reader better understand his motivations and nature towards Mr Dombey and Edith?

Yes. I see how Carker’s teeth can be expanded beyond that as solely portraying an aggressive ripping, tearing projection. He does, as you say, both prepare and grind information for consumption.

I found Carker to be a very interesting psychological study. Did you find Carker’s treatment and comments towards his brother helped the reader better understand his motivations and nature towards Mr Dombey and Edith?

Jantine,

I really like your interpretation of the Game Chicken as Mr. Toots's Mr. Hyde even though there are scenes when other characters such as Captain Cuttle and Rob the Grinder interact with him. I thought that the Game Chicken was an example of the parasites and fawners that wealthy people have to put up with. In a way, he is a comic relief equivalent of Mr. Carker: Clearly, Toots is more gullible and more harmless than Mr. Dombey, but there are several instances of how proud Toots is of his Game Chicken, whom he blindly adores up to a certain moment, i.e. the moment when the Chicken encourages him to thwart Walter and Florence's marriage. Hanging around with the Chicken gives Toots a feeling of exclusiveness, of being someone in society - in that way, the Chicken feeds on Mr. Toots's pride and vanity, just as Carker does on Mr. Dombey's.

As to Carker's losing his head, I can fully understand this - for the very reasons Jantine names: Carker is used to being in full control of every situation and of the people (and horses) around him. They are all just pawns in his games. Now, however, when he finds himself being duped by Edith, his world in which he has been master for so long, is all of a sudden turned upside down and he has to realize that somebody has got the better of him. Consequently, he loses a great deal of his self-confidence and has to come to terms with a new reality. In this context, his headlessness (even before the train smashes him) makes full sense to me.

Did you notice, by the way, that the narrator even grants a human side to Carker in this situation. Shortly before the accident, the narrator says,

I really like your interpretation of the Game Chicken as Mr. Toots's Mr. Hyde even though there are scenes when other characters such as Captain Cuttle and Rob the Grinder interact with him. I thought that the Game Chicken was an example of the parasites and fawners that wealthy people have to put up with. In a way, he is a comic relief equivalent of Mr. Carker: Clearly, Toots is more gullible and more harmless than Mr. Dombey, but there are several instances of how proud Toots is of his Game Chicken, whom he blindly adores up to a certain moment, i.e. the moment when the Chicken encourages him to thwart Walter and Florence's marriage. Hanging around with the Chicken gives Toots a feeling of exclusiveness, of being someone in society - in that way, the Chicken feeds on Mr. Toots's pride and vanity, just as Carker does on Mr. Dombey's.

As to Carker's losing his head, I can fully understand this - for the very reasons Jantine names: Carker is used to being in full control of every situation and of the people (and horses) around him. They are all just pawns in his games. Now, however, when he finds himself being duped by Edith, his world in which he has been master for so long, is all of a sudden turned upside down and he has to realize that somebody has got the better of him. Consequently, he loses a great deal of his self-confidence and has to come to terms with a new reality. In this context, his headlessness (even before the train smashes him) makes full sense to me.

Did you notice, by the way, that the narrator even grants a human side to Carker in this situation. Shortly before the accident, the narrator says,

"The air struck chill and comfortless as it breathed upon him. There was a heavy dew; and, hot as he was, it made him shiver. After a glance at the place where he had walked last night, and at the signal-lights burning in the morning, and bereft of their significance, he turned to where the sun was rising, and beheld it, in its glory, as it broke upon the scene.

So awful, so transcendent in its beauty, so divinely solemn. As he cast his faded eyes upon it, where it rose, tranquil and serene, unmoved by all the wrong and wickedness on which its beams had shone since the beginning of the world, who shall say that some weak sense of virtue upon Earth, and its in Heaven, did not manifest itself, even to him? If ever he remembered sister or brother with a touch of tenderness and remorse, who shall say it was not then?"

Kim,

That childhood experience of yours about the poor boy was surely horrible. As a parent, I can only read it with horror.

As to the title of the chapter, it is a very cynical one, isn't it? Carker's loss is apparently not worth a human tear - I wonder whether Harriet and John might not have shed some tears after all - but it is just a side note for Rob, who now has to look for a new situation. It is some form of poetic justice in that Carker, the man who has always treated people as pawns, as means to an end, is here seen as the means to Rob's subsistence.

That childhood experience of yours about the poor boy was surely horrible. As a parent, I can only read it with horror.

As to the title of the chapter, it is a very cynical one, isn't it? Carker's loss is apparently not worth a human tear - I wonder whether Harriet and John might not have shed some tears after all - but it is just a side note for Rob, who now has to look for a new situation. It is some form of poetic justice in that Carker, the man who has always treated people as pawns, as means to an end, is here seen as the means to Rob's subsistence.

Hm yes, I must admit I forgot about Cuttle and Rob interacting with The Chicken. I could see Cuttle humouring Toots, but not Rob.

It does have a beauty and a significance I think, that both Dombey and Toots lose that person that manipulates them in their pride, in a way that cuts them clean from any obligation. Dombey doesn't have to wonder where Carker is and if he should duel him anymore. Toots pays the 50 pounds and the Chicken has no more claim upon him.

It does have a beauty and a significance I think, that both Dombey and Toots lose that person that manipulates them in their pride, in a way that cuts them clean from any obligation. Dombey doesn't have to wonder where Carker is and if he should duel him anymore. Toots pays the 50 pounds and the Chicken has no more claim upon him.

I was surprised to see Carker go. I'm losing track of the number of times this book has taken me aback with its efficiency: here we're two installments from the end (I think?) and Paul is already dead, and Walter and Florence already married, and Carker dead as well. I understand this is a powerful chapter, with its stunned villain and its human moments juxtaposed to graphic violence, but--I don't know. Nothing's resolved. So somebody got the better of Carker--really? That's all it takes? He never really saw where the efforts of all his years and years of scheming went. He doesn't know where Edith will go next and he's had no resolution with his family or Dombey, unless you count Dombey watching him die, which I can't really see as a resolution. It was very weird to have that whole setup of Dombey hates you enough to kill you! Dombey is on your heels! Alice has loosed Dombey! Dombey is enraged with lethal madness!--and then have Carker get hit by a train. He doesn't even get a goodbye with Rob the Grinder.

I was surprised to see Carker go. I'm losing track of the number of times this book has taken me aback with its efficiency: here we're two installments from the end (I think?) and Paul is already dead, and Walter and Florence already married, and Carker dead as well. I understand this is a powerful chapter, with its stunned villain and its human moments juxtaposed to graphic violence, but--I don't know. Nothing's resolved. So somebody got the better of Carker--really? That's all it takes? He never really saw where the efforts of all his years and years of scheming went. He doesn't know where Edith will go next and he's had no resolution with his family or Dombey, unless you count Dombey watching him die, which I can't really see as a resolution. It was very weird to have that whole setup of Dombey hates you enough to kill you! Dombey is on your heels! Alice has loosed Dombey! Dombey is enraged with lethal madness!--and then have Carker get hit by a train. He doesn't even get a goodbye with Rob the Grinder.I kind of feel this character has been abruptly cut off metaphorically as well as literally.

Tristram wrote: "Kim,

That childhood experience of yours about the poor boy was surely horrible. As a parent, I can only read it with horror...."

Here are two more horrible things about it, the first being that I can't forget it. And I mean not even a tiny bit of it. I can see what he was wearing, I can see his legs under the car with the red cuffs on his blue jeans. I can see the red and black lunch box laying on the road. And that damn model airplane kit. If the white car drove past me right now I'd know it. Of all the things to remember as if it were yesterday, that isn't the one I would have picked.

The other thing was what happened the next day. This boy lived just at the top of the hill, two houses away from me, and the next day we were sitting in the back yard, me, my sister, the three kids from next door, we were doing nothing at all but sitting, no one felt like doing much, when all of a sudden his younger brother came running into the yard. He must have been about five years old, and ran up to us all excited and yelled, "Guess what! Mikey went to camp and he'll be there for a long time and I'm really going to miss him!", and turned and ran back up the hill to his own house. It's good he did because not one of us said anything, even after he was gone I don't think we said anything, although I know some of us were crying. I never saw him again, his mother couldn't stand being there, so she took him and moved in with her parents and never came back. Her husband stayed at the house though, and eventually they got divorced and he remarried, but if I ever saw Mikey again I no longer recognized him. I wonder what he's doing now.

That childhood experience of yours about the poor boy was surely horrible. As a parent, I can only read it with horror...."

Here are two more horrible things about it, the first being that I can't forget it. And I mean not even a tiny bit of it. I can see what he was wearing, I can see his legs under the car with the red cuffs on his blue jeans. I can see the red and black lunch box laying on the road. And that damn model airplane kit. If the white car drove past me right now I'd know it. Of all the things to remember as if it were yesterday, that isn't the one I would have picked.

The other thing was what happened the next day. This boy lived just at the top of the hill, two houses away from me, and the next day we were sitting in the back yard, me, my sister, the three kids from next door, we were doing nothing at all but sitting, no one felt like doing much, when all of a sudden his younger brother came running into the yard. He must have been about five years old, and ran up to us all excited and yelled, "Guess what! Mikey went to camp and he'll be there for a long time and I'm really going to miss him!", and turned and ran back up the hill to his own house. It's good he did because not one of us said anything, even after he was gone I don't think we said anything, although I know some of us were crying. I never saw him again, his mother couldn't stand being there, so she took him and moved in with her parents and never came back. Her husband stayed at the house though, and eventually they got divorced and he remarried, but if I ever saw Mikey again I no longer recognized him. I wonder what he's doing now.

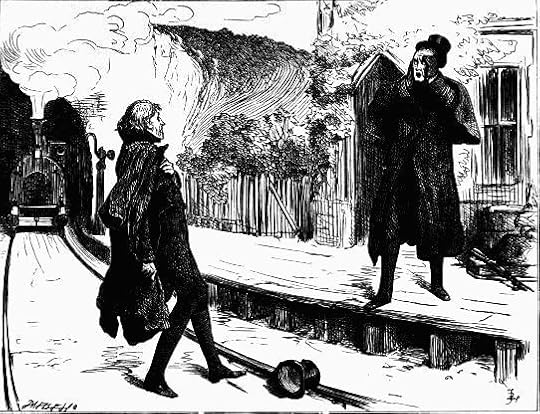

He saw the face change from its vindictive passion to a faint sickness and terror

Chapter 55

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

The air struck chill and comfortless as it breathed upon him. There was a heavy dew; and, hot as he was, it made him shiver. After a glance at the place where he had walked last night, and at the signal-lights burning in the morning, and bereft of their significance, he turned to where the sun was rising, and beheld it, in its glory, as it broke upon the scene.

So awful, so transcendent in its beauty, so divinely solemn. As he cast his faded eyes upon it, where it rose, tranquil and serene, unmoved by all the wrong and wickedness on which its beams had shone since the beginning of the world, who shall say that some weak sense of virtue upon Earth, and its in Heaven, did not manifest itself, even to him? If ever he remembered sister or brother with a touch of tenderness and remorse, who shall say it was not then?

He needed some such touch then. Death was on him. He was marked off—the living world, and going down into his grave.

He paid the money for his journey to the country-place he had thought of; and was walking to and fro, alone, looking along the lines of iron, across the valley in one direction, and towards a dark bridge near at hand in the other; when, turning in his walk, where it was bounded by one end of the wooden stage on which he paced up and down, he saw the man from whom he had fled, emerging from the door by which he himself had entered. And their eyes met.

In the quick unsteadiness of the surprise, he staggered, and slipped on to the road below him. But recovering his feet immediately, he stepped back a pace or two upon that road, to interpose some wider space between them, and looked at his pursuer, breathing short and quick.

He heard a shout—another—saw the face change from its vindictive passion to a faint sickness and terror—felt the earth tremble—knew in a moment that the rush was come—uttered a shriek—looked round—saw the red eyes, bleared and dim, in the daylight, close upon him—was beaten down, caught up, and whirled away upon a jagged mill, that spun him round and round, and struck him limb from limb, and licked his stream of life up with its fiery heat, and cast his mutilated fragments in the air.

When the traveller, who had been recognised, recovered from a swoon, he saw them bringing from a distance something covered, that lay heavy and still, upon a board, between four men, and saw that others drove some dogs away that sniffed upon the road, and soaked his blood up, with a train of ashes.

[image error]

original sketch

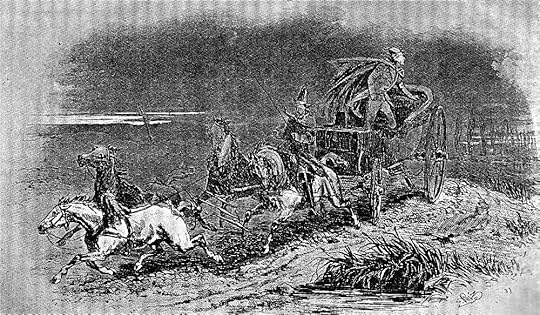

On The Dark Road

Chapter 55

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Listen, my friend. I am much hurried. Let us see how fast we can travel! The faster, the more money there will be to drink. Off we go then! Quick!"

"Halloa! whoop! Halloa! Hi!" Away, at a gallop, over the black landscape, scattering the dust and dirt like spray!

The clatter and commotion echoed to the hurry and discordance of the fugitive's ideas. Nothing clear without, and nothing clear within. Objects flitting past, merging into one another, dimly descried, confusedly lost sight of, gone! Beyond the changing scraps of fence and cottage immediately upon the road, a lowering waste. Beyond the shifting images that rose up in his mind and vanished as they showed themselves, a black expanse of dread and rage and baffled villainy. Occasionally, a sigh of mountain air came from the distant Jura, fading along the plain. Sometimes that rush which was so furious and horrible, again came sweeping through his fancy, passed away, and left a chill upon his blood.

The lamps, gleaming on the medley of horses' heads, jumbled with the shadowy driver, and the fluttering of his cloak, made a thousand indistinct shapes, answering to his thoughts. Shadows of familiar people, stooping at their desks and books, in their remembered attitudes; strange apparitions of the man whom he was flying from, or of Edith; repetitions in the ringing bells and rolling wheels, of words that had been spoken; confusions of time and place, making last night a month ago, a month ago last night—home now distant beyond hope, now instantly accessible; commotion, discord, hurry, darkness, and confusion in his mind, and all around him. — Hallo! Hi! away at a gallop over the black landscape; dust and dirt flying like spray, the smoking horses snorting and plunging as if each of them were ridden by a demon, away in a frantic triumph on the dark road — whither?

Commentary:

According to Valerie Lester Browne, this was Phiz's first attempt at a classic 'dark plate', in this case to show the futility of the villainous Carker's trying to cheat death as he makes his way through France to England to confront Mr. Dombey. The 1848 illustration, moreover, engages the viewer with the sharpness and vivacity of the figures and the prancing horses — horses having been from his earliest compositions one of Phiz's strengths. Better reproductions of this delightful illustration convey the aerial perspective through making clear the line of Lombardy poplars running off to the horizon, upper right.

For the illustration, 'On a dark road,' Phiz turned the plate horizontally and used a ruling machine, which pushed a bank of needles across the wax ground on the plate, creating a background of narrow stripes, akin to mezzotinting. (The technique is sometimes referred to as 'machine tinting'.) He then drew into dark areas to make them blacker and produced a variety of greys by stopping-out other areas. To retain the dazzling whites, he burnished away the ruled lines and stopped out those areas completely on the first and all subsequent visits to the acid.

Phiz's use of a ruling machine was a divergence from the more popular aquatint method used by other etchers. He may have disliked aquatint's time-consuming use of resin, a messy substance which, if inhaled, could injure the lungs. With his ruling machine he created tones with less nuisance. (After his experiments on Lever's Roland Cashel (1850), he no longer used the ruling machine for light topics; the brights were never bright enough.)

'On the Dark Road' is one of the most completely successful of all Phiz's images. A long, slow diagonal slices down fro receding poplar trees in thew upper right to the coach and standing figure of windswept Carker, and moves on down through the coachman (who provides an opposing diagonal with his whip) to the four horses racing towards the bottom left of the picture. Phiz took enormous technical care with the plate, and its atmosphere of menace is enhanced by the addition of details: a black bird, a dark pool, a lowering sky, a leaning finger-post, and the rolling eyes and hot breath of the horses.

The dark plate becomes ubiquitous among Browne's etchings in the late forties and through the fifties, and it is as well to explain the technique at this point. In its most basic form it provides a way of adding mechanically ruled, very closely spaced lines to the steel in order to produce a "tint," a grayish shading of the plate. It is this simple method that Browne occasionally used for authors other than Dickens. But in general he made more subtle and complex use of the dark plate. . . . . The highlights, areas which were to remain white, would be stopped out with varnish, and then the biting could commence. Those areas which were to be lightest in tint would be stopped out after a short bite, the next lightest after a longer bite, and so on down to the very blackest areas — which would never, except where wholly exposed by the needle, become totally black, but would shimmer with the tiny lights of the unexposed bits between the ruled lines; the darkest sky in On the Dark Road has these little lights, while the dark parts of the puddle have none, apparently having been exposed to the acid by the needle rather than the ruling machine.

An ominous and menacing atmosphere surrounds the open carriage or barouche as the onset of darkness implies impending doom for Carker, although the figures and horses in this earliest Phiz dark plate are sharply delineated, and the four horses (hardly heavy carriage-horses, but spirited racing steeds in harness) passing rapidly through the French countryside are individualised. Phiz has the open coach rapidly approaching the viewer, with an apparent break in the clouds (right) throwing the face of the standing figure, the lead horse, the body of the postillion's horse, and the vegetation at the side of the road (lower right) into fleeting sunlight in a powerful chiaroscuro that contributes to the melodramatic effect of the illustration as a whole as dark and light compete for dominance in the plate, in which Carker's head (turned, as it were, towards the past rather than the unknown future) is the pinnacle of the pyramid.

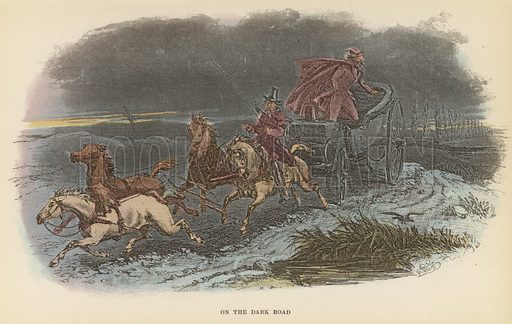

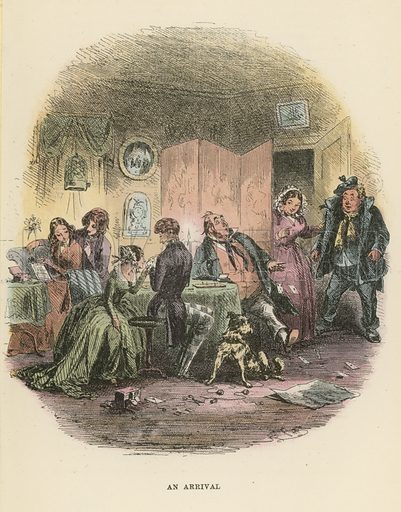

An Arrival

Chapter 56

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The Captain spoke with all composure and attention to the game, but suddenly his cards dropped out of his hand, his mouth and eyes opened wide, his legs drew themselves up and stuck out in front of his chair, and he sat staring at the door with blank amazement. Looking round upon the company, and seeing that none of them observed him or the cause of his astonishment, the Captain recovered himself with a great gasp, struck the table a tremendous blow, cried in a stentorian roar, ‘Sol Gills ahoy!’ and tumbled into the arms of a weather-beaten pea-coat that had come with Polly into the room.

In another moment, Walter was in the arms of the weather-beaten pea-coat. In another moment, Florence was in the arms of the weather-beaten pea-coat. In another moment, Captain Cuttle had embraced Mrs Richards and Miss Nipper, and was violently shaking hands with Mr Toots, exclaiming, as he waved his hook above his head, ‘Hooroar, my lad, hooroar!’ To which Mr Toots, wholly at a loss to account for these proceedings, replied with great politeness, ‘Certainly, Captain Gills, whatever you think proper!’

The weather-beaten pea-coat, and a no less weather-beaten cap and comforter belonging to it, turned from the Captain and from Florence back to Walter, and sounds came from the weather-beaten pea-coat, cap, and comforter, as of an old man sobbing underneath them; while the shaggy sleeves clasped Walter tight. During this pause, there was an universal silence, and the Captain polished his nose with great diligence. But when the pea-coat, cap, and comforter lifted themselves up again, Florence gently moved towards them; and she and Walter taking them off, disclosed the old Instrument-maker, a little thinner and more careworn than of old, in his old Welsh wig and his old coffee-coloured coat and basket buttons, with his old infallible chronometer ticking away in his pocket.

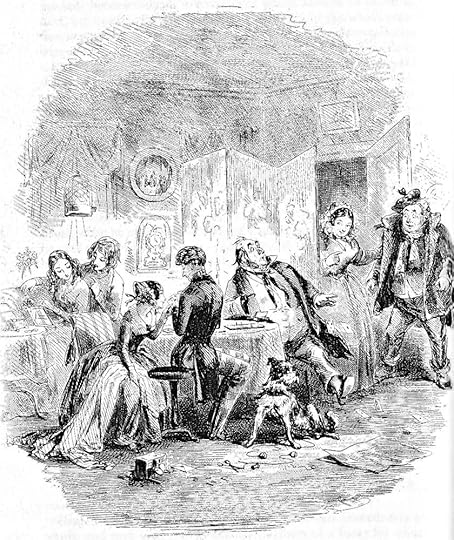

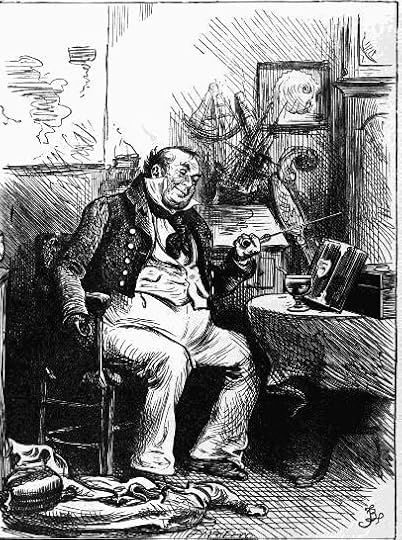

After this, he smoked four pipes successively in the little parlour by himself

Chapter 56

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

Limited and plain as Florence’s wardrobe was—what a contrast to that prepared for the last marriage in which she had taken part!—there was a good deal to do in getting it ready, and Susan Nipper worked away at her side, all day, with the concentrated zeal of fifty sempstresses. The wonderful contributions Captain Cuttle would have made to this branch of the outfit, if he had been permitted—as pink parasols, tinted silk stockings, blue shoes, and other articles no less necessary on shipboard—would occupy some space in the recital. He was induced, however, by various fraudulent representations, to limit his contributions to a work-box and dressing case, of each of which he purchased the very largest specimen that could be got for money. For ten days or a fortnight afterwards, he generally sat, during the greater part of the day, gazing at these boxes; divided between extreme admiration of them, and dejected misgivings that they were not gorgeous enough, and frequently diving out into the street to purchase some wild article that he deemed necessary to their completeness. But his master-stroke was, the bearing of them both off, suddenly, one morning, and getting the two words FLORENCE GAY engraved upon a brass heart inlaid over the lid of each. After this, he smoked four pipes successively in the little parlour by himself, and was discovered chuckling, at the expiration of as many hours.

"Why, it's mean....that's where it is. It's mean!"

Fred Barnard

Chapter 56

Text Illustrated:

His patron being much engaged with his own thoughts, did not observe this for some time, nor indeed until the Chicken, determined not to be overlooked, had made divers clicking sounds with his tongue and teeth, to attract attention.

‘Now, Master,’ said the Chicken, doggedly, when he, at length, caught Mr Toots’s eye, ‘I want to know whether this here gammon is to finish it, or whether you’re a going in to win?’

‘Chicken,’ returned Mr Toots, ‘explain yourself.’

‘Why then, here’s all about it, Master,’ said the Chicken. ‘I ain’t a cove to chuck a word away. Here’s wot it is. Are any on ‘em to be doubled up?’

When the Chicken put this question he dropped his hat, made a dodge and a feint with his left hand, hit a supposed enemy a violent blow with his right, shook his head smartly, and recovered himself.

‘Come, Master,’ said the Chicken. ‘Is it to be gammon or pluck? Which?’

‘Chicken,’ returned Mr Toots, ‘your expressions are coarse, and your meaning is obscure.’

‘Why, then, I tell you what, Master,’ said the Chicken. ‘This is where it is. It’s mean.’

‘What is mean, Chicken?’ asked Mr Toots.

‘It is,’ said the Chicken, with a frightful corrugation of his broken nose. ‘There! Now, Master! Wot! When you could go and blow on this here match to the stiff’un;’ by which depreciatory appellation it has been since supposed that the Game One intended to signify Mr Dombey; ‘and when you could knock the winner and all the kit of ‘em dead out o’ wind and time, are you going to give in? To give in?’ said the Chicken, with contemptuous emphasis. ‘Wy, it’s mean!’

‘Chicken,’ said Mr Toots, severely, ‘you’re a perfect Vulture! Your sentiments are atrocious.’

‘My sentiments is Game and Fancy, Master,’ returned the Chicken. ‘That’s wot my sentiments is. I can’t abear a meanness. I’m afore the public, I’m to be heerd on at the bar of the Little Helephant, and no Gov’ner o’ mine mustn’t go and do what’s mean. Wy, it’s mean,’ said the Chicken, with increased expression. ‘That’s where it is. It’s mean.’

‘Chicken,’ said Mr Toots, ‘you disgust me.’

‘Master,’ returned the Chicken, putting on his hat, ‘there’s a pair on us, then. Come! Here’s a offer! You’ve spoke to me more than once’t or twice’t about the public line. Never mind! Give me a fi’typunnote to-morrow, and let me go.’

‘Chicken,’ returned Mr Toots, ‘after the odious sentiments you have expressed, I shall be glad to part on such terms.’

‘Done then,’ said the Chicken. ‘It’s a bargain. This here conduct of yourn won’t suit my book, Master. Wy, it’s mean,’ said the Chicken; who seemed equally unable to get beyond that point, and to stop short of it. ‘That’s where it is; it’s mean!’

So Mr Toots and the Chicken agreed to part on this incompatibility of moral perception; and Mr Toots lying down to sleep, dreamed happily of Florence, who had thought of him as her friend upon the last night of her maiden life, and who had sent him her dear love.

Kim wrote: "

original sketch

On The Dark Road

Chapter 55

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Listen, my friend. I am much hurried. Let us see how fast we can travel! The faster, the more money there will be to dr..."

Kim: three cheers for Browne.

To me “On the Dark Road” captures the mood and tension of the Carker-Dombey relationship in the novel. The illustration has a brooding feel and yet it is full of energy. You can sense the power of the horses as they speed through the night and the fear of Carker as he looks towards the pursuing Dombey. The darkness, the pond, and the bird beginning to take flight all combine to illustrate that the final reckoning is fast approaching. Carker is, as the commentary observes, at the apex of the pyramid in the illustration. His final hour is approaching. All that surrounds Carker are the elements of nature.

original sketch

On The Dark Road

Chapter 55

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Listen, my friend. I am much hurried. Let us see how fast we can travel! The faster, the more money there will be to dr..."

Kim: three cheers for Browne.

To me “On the Dark Road” captures the mood and tension of the Carker-Dombey relationship in the novel. The illustration has a brooding feel and yet it is full of energy. You can sense the power of the horses as they speed through the night and the fear of Carker as he looks towards the pursuing Dombey. The darkness, the pond, and the bird beginning to take flight all combine to illustrate that the final reckoning is fast approaching. Carker is, as the commentary observes, at the apex of the pyramid in the illustration. His final hour is approaching. All that surrounds Carker are the elements of nature.

Kim wrote: "

An Arrival

Chapter 56

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The Captain spoke with all composure and attention to the game, but suddenly his cards dropped out of his hand, his mouth and eyes opened wide, ..."

In contrast to the elemental night flight of Carker in Browne’s companion illustration “On the Dark Road” here we get a scene of domestic warmth and harmony. Carker’s solitary flight away from Dombey is counterbalanced in this illustration by Sol Gills return into the story and into his home where he finds his friends and family. Rather than Carker’s solitary dash through the elements of nature from a man he now fears, this illustration presents a coming together. This scene is domestic in nature.

The first sentence of Chapter 56 is “The Midshipman was all alive.” This sentence is in stark contrast to the last sentence of the previous chapter that recounts Carker’s end. Here we read that Carker’s body “lay heavy and still” and that some dogs were driven away “that sniffed upon the road, and soaked his blood up, with a train of ashes.“

When we look at the illustration for Sol’s return we see some interesting pairings. To the left are two couples who are portrayed as happy and harmonious. First, it is the day before the wedding of Walter and Florence. The two couples in this quadrant of the illustration are Florence and Walter. The other is Toots and Susan Nipper. The arrival of Sol Gills means he and Captain Cuttle are reunited. Rounding out the illustration is Polly, who has been a good and faithful friend to all those within the illustration. Let's not forget Diogenes who completes the harmonious scene. In the previous chapter dogs lapped up Carker's blood. In this illustration, Diogenes serves as a faithful companion to Florence, a link to Florence's young deceased brother Paul, and emblem of kindness and a gift from Toots.

The companion illustrations of “On the Dark Road” and “An arrival” by Browne offer the reader/viewer two different worlds.

As an aside, “An Arrival” also gives us a hint to a future plot development. No spoilers, of course, but can you see it? :-)

An Arrival

Chapter 56

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The Captain spoke with all composure and attention to the game, but suddenly his cards dropped out of his hand, his mouth and eyes opened wide, ..."

In contrast to the elemental night flight of Carker in Browne’s companion illustration “On the Dark Road” here we get a scene of domestic warmth and harmony. Carker’s solitary flight away from Dombey is counterbalanced in this illustration by Sol Gills return into the story and into his home where he finds his friends and family. Rather than Carker’s solitary dash through the elements of nature from a man he now fears, this illustration presents a coming together. This scene is domestic in nature.

The first sentence of Chapter 56 is “The Midshipman was all alive.” This sentence is in stark contrast to the last sentence of the previous chapter that recounts Carker’s end. Here we read that Carker’s body “lay heavy and still” and that some dogs were driven away “that sniffed upon the road, and soaked his blood up, with a train of ashes.“

When we look at the illustration for Sol’s return we see some interesting pairings. To the left are two couples who are portrayed as happy and harmonious. First, it is the day before the wedding of Walter and Florence. The two couples in this quadrant of the illustration are Florence and Walter. The other is Toots and Susan Nipper. The arrival of Sol Gills means he and Captain Cuttle are reunited. Rounding out the illustration is Polly, who has been a good and faithful friend to all those within the illustration. Let's not forget Diogenes who completes the harmonious scene. In the previous chapter dogs lapped up Carker's blood. In this illustration, Diogenes serves as a faithful companion to Florence, a link to Florence's young deceased brother Paul, and emblem of kindness and a gift from Toots.

The companion illustrations of “On the Dark Road” and “An arrival” by Browne offer the reader/viewer two different worlds.

As an aside, “An Arrival” also gives us a hint to a future plot development. No spoilers, of course, but can you see it? :-)

I was surprised that Carker died so quickly. I was expecting a showdown between him and Dombey. It makes sense, though, because Dickens's villains always self-destruct at the end. I think it's a rule that they have to.

I was surprised that Carker died so quickly. I was expecting a showdown between him and Dombey. It makes sense, though, because Dickens's villains always self-destruct at the end. I think it's a rule that they have to.I really enjoyed the reunion of all the good characters, like the Nipper, Mrs. Richards, Sol Gills, and so on. I also enjoyed the wedding chapter. Weddings and church scenes are a theme in this book. They signify a new beginning or turning-point for the characters. Florence's wedding was satisfying to read, and it tied up the story nicely. The only thing I don't understand is why they didn't drink that Madeira.

Now what will happen to Dombey? I'm very curious to see. I agree that he is a sad character, but I feel like he didn't try hard enough to improve himself or try to gain insight into his problems. There's still time, but I have no clue what will happen next.

Alissa wrote: "I was surprised that Carker died so quickly. I was expecting a showdown between him and Dombey. It makes sense, though, because Dickens's villains always self-destruct at the end. I think it's a ru..."

Hi Alissa

You are so right. It seems that once Dickens clearly establishes who the villains are in a novel their self-destruction is guaranteed. Their ends are most often gruesome which makes it fun to speculate what Dickens will do to the bad guy.

Yes, as we get to the end of a novel Dickens has to reward the good guys, and I really like your phrase that weddings and church scenes signify a new beginning or turning point for characters. There will be more church bells in the novel, and perhaps a surprise or two as well. I always enjoy the endings of Dickens novels. While often very predictable on one level his endings most often set the world into alignment again, and I like that.

Ah, now about Dombey. Here, I think, we will have much discussion in the last couple of weeks.

Hi Alissa

You are so right. It seems that once Dickens clearly establishes who the villains are in a novel their self-destruction is guaranteed. Their ends are most often gruesome which makes it fun to speculate what Dickens will do to the bad guy.

Yes, as we get to the end of a novel Dickens has to reward the good guys, and I really like your phrase that weddings and church scenes signify a new beginning or turning point for characters. There will be more church bells in the novel, and perhaps a surprise or two as well. I always enjoy the endings of Dickens novels. While often very predictable on one level his endings most often set the world into alignment again, and I like that.

Ah, now about Dombey. Here, I think, we will have much discussion in the last couple of weeks.

There are so many characters that don't die fast enough for me. And no, Little Nell isn't one of them.:-)

Alissa wrote: "I was surprised that Carker died so quickly. I was expecting a showdown between him and Dombey. It makes sense, though, because Dickens's villains always self-destruct at the end. I think it's a ru..."

Alissa wrote: "I was surprised that Carker died so quickly. I was expecting a showdown between him and Dombey. It makes sense, though, because Dickens's villains always self-destruct at the end. I think it's a ru..."That took me by surprise also. How else could Dickens have expounded on his demise? I'm asking I'm not sure.

Francis wrote: "Alissa wrote: "I was surprised that Carker died so quickly. I was expecting a showdown between him and Dombey. It makes sense, though, because Dickens's villains always self-destruct at the end. I ..."

Francis

Good question. In terms of plot I don’t think Dickens could have brought Carker and Dombey into a direct physical confrontation. Somebody would get hurt, or worse. If Dombey harmed/killed Carker, then Dombey would have to pay the penalty. That would mean no reconciliation with Florence. If Carker maimed/killed Dombey then that also would detract or worse cancel the reconciliation scene between Dombey and Florence. Dickens needed the reconciliation to be as neat and totally focussed as possible on Florence and her father for his readers.

A train is quite the way to die. That said, we have the presence of the train throughout the novel as a disruptive fact. Stagg’s Gardens is the clearest example. The coming of the train into Victorian society was a sea change. Consider how the Toodle family benefits from Mr Toodle’s job and his promotions.

Also, the train was a relatively new phenomenon in England. People were fascinated with it. Therefore, any tragedy because of this new technology would garner great interest in the reading public. When we look at all Dickens’s work, D&S is the only novel that makes the train a focus. In the other novels, even the late novels, people move about by true “horse” power.

Francis

Good question. In terms of plot I don’t think Dickens could have brought Carker and Dombey into a direct physical confrontation. Somebody would get hurt, or worse. If Dombey harmed/killed Carker, then Dombey would have to pay the penalty. That would mean no reconciliation with Florence. If Carker maimed/killed Dombey then that also would detract or worse cancel the reconciliation scene between Dombey and Florence. Dickens needed the reconciliation to be as neat and totally focussed as possible on Florence and her father for his readers.

A train is quite the way to die. That said, we have the presence of the train throughout the novel as a disruptive fact. Stagg’s Gardens is the clearest example. The coming of the train into Victorian society was a sea change. Consider how the Toodle family benefits from Mr Toodle’s job and his promotions.

Also, the train was a relatively new phenomenon in England. People were fascinated with it. Therefore, any tragedy because of this new technology would garner great interest in the reading public. When we look at all Dickens’s work, D&S is the only novel that makes the train a focus. In the other novels, even the late novels, people move about by true “horse” power.

I thought this was a wonderful end for Carker.

I thought this was a wonderful end for Carker. I really enjoyed his descent into panic, and I agree with Tristram that this was because his world where he is in control of himself and others for his amusement, was collapsing, and being thwarted and afraid were so alien to him that he couldn't adapt and fled.

The fact that he fled back to England makes sense if it was the place he felt most secure and in control, although I was surprised he didn't disappear overboard on the boat.