The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son

>

D&S, Chp. 61-62

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 62

Finally, finally, finally, the last bottle of Madeira is opened!

The partakers are Mr. Dombey, Sol Gills and his nephew Walter, Captain Cuttle and Mr. Toots – and there are also Florence and Susan present, although I don’t know whether those last two were, according to Victorian mores supposed, as women, to relish Madeira. Among other things we learn that Mr. Dombey has recovered from his illness after all and that Solomon Gills is prospering, not so much because of his shop, which he now leads with Captain Cuttle as his partner, but more because of some old, forgotten shipping business has paid out well for him. Walter, on the basis of this little fortune, has also gone into the shipping business and is enlarging his house little by little so that there might be some kind of Dombey and Son in the future – and that Miss Tox’s prophesy that after all, Dombey and Son might be Dombey and Daughter is quite true in a way. Another thing we learn is that Mr. Morfin is now married to Harriet, and that the surviving Carkers have remained true to their intention of letting Mr. Dombey live off the Carker inheritance.

We also learn that Florence and Walter had a daughter shortly after little Paul’s birth, and that this little child is old Dombey’s favourite – however much he loves little Paul. Not only does the novel conclude with the whisperings of the waves we have so often listened to, but we also get this little passage:

This reminded me of a passage I read in the very first chapter; here it is:

Which brings me to my only question for now: Seeing that Dombey has mastered the storms of his master-passion Pride, are we ready to forgive him?

Finally, finally, finally, the last bottle of Madeira is opened!

The partakers are Mr. Dombey, Sol Gills and his nephew Walter, Captain Cuttle and Mr. Toots – and there are also Florence and Susan present, although I don’t know whether those last two were, according to Victorian mores supposed, as women, to relish Madeira. Among other things we learn that Mr. Dombey has recovered from his illness after all and that Solomon Gills is prospering, not so much because of his shop, which he now leads with Captain Cuttle as his partner, but more because of some old, forgotten shipping business has paid out well for him. Walter, on the basis of this little fortune, has also gone into the shipping business and is enlarging his house little by little so that there might be some kind of Dombey and Son in the future – and that Miss Tox’s prophesy that after all, Dombey and Son might be Dombey and Daughter is quite true in a way. Another thing we learn is that Mr. Morfin is now married to Harriet, and that the surviving Carkers have remained true to their intention of letting Mr. Dombey live off the Carker inheritance.

We also learn that Florence and Walter had a daughter shortly after little Paul’s birth, and that this little child is old Dombey’s favourite – however much he loves little Paul. Not only does the novel conclude with the whisperings of the waves we have so often listened to, but we also get this little passage:

”Mr Dombey is a white-haired gentleman, whose face bears heavy marks of care and suffering; but they are traces of a storm that has passed on for ever, and left a clear evening in its track.”

This reminded me of a passage I read in the very first chapter; here it is:

”On the brow of Dombey, Time and his brother Care had set some marks, as on a tree that was to come down in good time – remorseless twins they are for striding through their human forests, notching as they go – while the countenance of Son was crossed with a thousand little creases, which the same deceitful Time would take delight in smoothing out and wearing away with the flat part of his scythe, as a preparation of the surface for his deeper operations.”

Which brings me to my only question for now: Seeing that Dombey has mastered the storms of his master-passion Pride, are we ready to forgive him?

Are we ready to forgive him?

Yes, I notice that I am after reading these last chapters. He is changed, he does better, and that apparently does make all the difference (and that he's a fictional character and his wrongs, awful as they were, were fictional too helps probably). I like him a lot better as a grandfather than I liked him as a father, I know that for sure!

On one hand I'd have loved for Edith and Dombey to reconcile and somehow fall in love with each other after all, or at least talk things out and become friends in a way, but I don't think that would have worked. Not in that society. I also think that cousing Feenix does take care of Edith in a way, mostly by providing her a safe place to live, both physically and socially. Living with an elderly cousin, taking care of him, is some kind of comeback into respectability, although her former social circles would probably also see it as some kind of sentence/penance on her side. It would probably open doors for her to live a relatively normal life. I do find cousin Feenix kind of endearing somehow. His observations and actions can be hit or miss, but it all seems to come from a somewhat deluded but good heart.

Yes, I notice that I am after reading these last chapters. He is changed, he does better, and that apparently does make all the difference (and that he's a fictional character and his wrongs, awful as they were, were fictional too helps probably). I like him a lot better as a grandfather than I liked him as a father, I know that for sure!

On one hand I'd have loved for Edith and Dombey to reconcile and somehow fall in love with each other after all, or at least talk things out and become friends in a way, but I don't think that would have worked. Not in that society. I also think that cousing Feenix does take care of Edith in a way, mostly by providing her a safe place to live, both physically and socially. Living with an elderly cousin, taking care of him, is some kind of comeback into respectability, although her former social circles would probably also see it as some kind of sentence/penance on her side. It would probably open doors for her to live a relatively normal life. I do find cousin Feenix kind of endearing somehow. His observations and actions can be hit or miss, but it all seems to come from a somewhat deluded but good heart.

Tristram wrote: "Interestingly, both Edith and Florence now have a father – or some sort of father ersatz – and it remains to be seen how is taking care of whom. Cousin Feenix might think that he is looking after Edith but if you take a look at his unstable legs you might think that before long, Edith will play the protective part in that duo. Are you satisfied with this outcome?"

Tristram wrote: "Interestingly, both Edith and Florence now have a father – or some sort of father ersatz – and it remains to be seen how is taking care of whom. Cousin Feenix might think that he is looking after Edith but if you take a look at his unstable legs you might think that before long, Edith will play the protective part in that duo. Are you satisfied with this outcome?"Jantine wrote: "Living with an elderly cousin, taking care of him, is some kind of comeback into respectability, although her former social circles would probably also see it as some kind of sentence/penance on her side. It would probably open doors for her to live a relatively normal life. I do find cousin Feenix kind of endearing somehow. His observations and actions can be hit or miss, but it all seems to come from a somewhat deluded but good heart."

I am satisfied with the Feenix part, very. I didn't know he had that kind of thoughtfulness in him. I do think Edith needs a father more than a husband, and while I am sorry she isn't getting any Madiera, there is nothing magical about the convention of marriage, especially Edith and Dombey's marriage, which it has been pointed out repeatedly was a socially-condoned act of prostitution. So to go back to Dombey, whom she never loved, would be to go back to her prostitution, and we don't see that as a good outcome for Alice, do we?

I don't even think Feenix is getting out of this arrangement more than he is putting in. The money and the respectability are his and the latter especially is huge. Even if we look at it strictly in economic terms, as Jantine points out, Edith is getting something she never ever had before, which is the opportunity to make a living as a gentlewoman respectably (by caring for her cousin). And if we look beyond the economics, which is what this book wants us to do ("What is money?"), Edith is getting someone to love her unreservedly and someone she can love and care for, also something she never had and what she wanted so desperately with Florence but was not allowed because Dombey came first and ruined it.

I find I'm very satisfied with this ending for Edith. She softens just enough for her own redemption--she will think kindly of Dombey and wish him well--but she does not bend. I'm glad she remains her unbending self.

And of course it is perfectly true to her character that she remains innocent of adultery but won't tell anyone except Florence. The one person whose opinion Edith really cares about has been herself (and Florence eventually), because nobody else has cared about Edith. It's nice that Feenix, wily guy, has found the way to coax the truth out of her through Florence, since Feenix now cares about her too.

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Interestingly, both Edith and Florence now have a father – or some sort of father ersatz – and it remains to be seen how is taking care of whom. Cousin Feenix might think that he i..."

Hi Julie

Your comments and insights on Edith are very sound and impressive. You have put her, and thus the novel, in a clearer focus.

Hi Julie

Your comments and insights on Edith are very sound and impressive. You have put her, and thus the novel, in a clearer focus.

I think that Cousin Feenix is paying Edith a kind of debt he thinks that his family have run up with Edith by not caring about her properly when she must have needed it most, i.e. when she was alone with her mother, who tried to use her daughter in order to secure a comfortable position in society for herself. This reminds me of a further parallel between Edith and Alice in that the latter repeatedly says that she feels no remorse about anything she did because the world felt no remorse about anything it did to her. In the end, Alice softened and found Harriet to care for her - Edith, on the other hand, would never have deigned to express this feeling of bitterness. I think that her pride was on the whole a little bit more self-destructive than Alice's in that she never spared herself anything and was never outspoken (except to her mother) about what she conceived as the wrongs she had to undergo.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 62

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 62Finally, finally, finally, the last bottle of Madeira is opened!

The partakers are Mr. Dombey, Sol Gills and his nephew Walter, Captain Cuttle and Mr. Toots – and there are also Floren..."

Makes me wish I could be there to partake with them.

Me too, Francis, me too. It must have been one of those occasions when everything is just right and everyone is happy and nice.

Dombey and Son has so much more depth and breadth than the earlier novels. I marvel at how Dickens was able to turn the corner so quickly.

Our next novels will be a treat to read and discuss.

Our next novels will be a treat to read and discuss.

Tristram wrote: "This reminds me of a further parallel between Edith and Alice in that the latter repeatedly says that she feels no remorse about anything she did because the world felt no remorse about anything it did to her. In the end, Alice softened and found Harriet to care for her - Edith, on the other hand, would never have deigned to express this feeling of bitterness. I think that her pride was on the whole a little bit more self-destructive than Alice's in that she never spared herself anything and was never outspoken (except to her mother) about what she conceived as the wrongs she had to undergo."

Tristram wrote: "This reminds me of a further parallel between Edith and Alice in that the latter repeatedly says that she feels no remorse about anything she did because the world felt no remorse about anything it did to her. In the end, Alice softened and found Harriet to care for her - Edith, on the other hand, would never have deigned to express this feeling of bitterness. I think that her pride was on the whole a little bit more self-destructive than Alice's in that she never spared herself anything and was never outspoken (except to her mother) about what she conceived as the wrongs she had to undergo."I still think Alice is sloppily written but this comment has me coming back around on whether she's a necessary character or not. She does do a lot to put Edith into relief, and explore the themes of money and pride. I guess the book does need her.

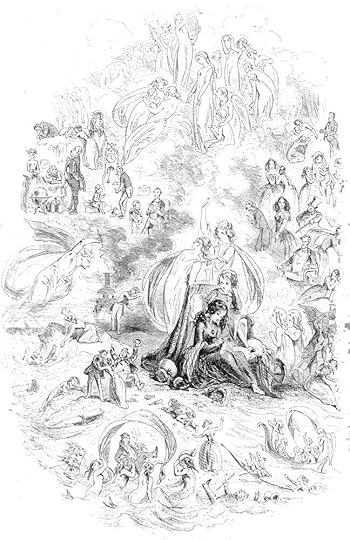

This plate was the uncaptioned frontispiece for Dickens's Dombey and Son in serial with the last number, which appeared in April 1848.

Commentary

Phiz chose to treat the frontispiece for the last number quite differently than he had the covers for the individual numbers of the periodical publication, which had a hearts and diamonds "house of cards" motif. In contrast, the vignette and frontispiece issued with the final double number, which appeared on 1 April 1848, surrounds the central vignette of Paul and his mother with specific in the novel’s characters and situations, some of which are represented literally and others symbolically. Whereas the wrapper is full of textual cues, such as "Bankers.BK" and "Cheque.BK" (lower left) and "Cash Box" and "Day Book" (upper centre) upon Mr. Dombey sits in a throne-like chair, the frontispiece contains but a single embedded word (that on the cash-box above Paul and his father, just left of centre), so that one cannot fully understand to the images refer unless one has an intimate knowledge of the book as a whole — which, of course, the reader of the nineteen monthly parts would possess.

According to Alan Horsman, editor of the standard scholarly edition,

The method of the frontispiece matches that of the cover design for the monthly parts in so far as it combines allegory with the illustration of particular incidents from the novel. The main subject, the unknown sea into which time flows, allows for comedy as well for sentiment and melodrama.The centre, and the top to which the eye is carried from it, emphasize Paul taken from his place beside the actual sea to the metaphorical sea and his mother. But about this centre there is comedy as he grows up, watched by Miss Tox or the Blimbers, or as winds and mermaids bring Sol Gills back to the shore [lower register, centre], or, with less appositeness, Miss Tox sees the Major sinking from her only to be caught in the waves herself, and to have to beg Cupid to save her [lower register, right]. The two death-beds of the early part of the novel and the rescue of Mr. Dombey from suicide by Florence and her child, at the end of it, while the melodrama is fully represented in the rejection and death of Carker [left of centre, in front of a locomotive, cringing from a winged devil] and in Edith and Mr. Dombey obviously dead to each other. The whole answers the design on the wrapper, now that the story is known and complete. [Appendix E, pp. 870-71]

One might add that the scene at the bottom might also represent Walter Gay's surviving the shipwreck on the Dombey & Co. voyage to Barbados. Providentially, he returns to London and marries Florence Dombey. The nymphs also represent the imaginative world so obviously lacking from Dombey's grim universe.

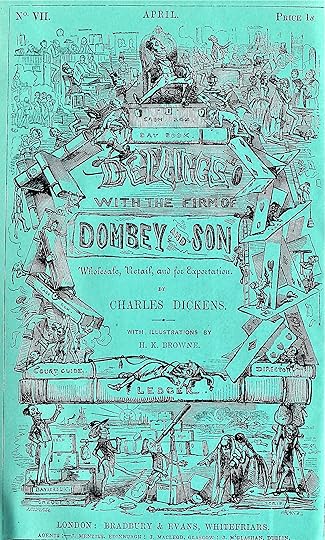

Monthly Wrapper

Commentary:

Dickens' seventh novel is at once less complicated and more complex than his sixth. Instead of Martin Chuzzlewit's proliferation of subplots and groups of characters mirroring one another in rather abstract ways, in Dombey and Son Dickens carefully relates moral, social, and psychological themes, purposefully rather than in hindsight. His penetration beneath the brilliant linguistic surface is also deeper. although the novel pivots on the moral progress of Mr. Dombey, the fact that his evil has social ramifications means that his individual development does not become the primary point of reference. And Mr. Dombey is at once the source of Paul's and Florence's difficulties in childhood and his own ensnarement in a tangled set of conflicts regarding power and sex. Browne's most important illustrations bear on these topics, and at their best they interpret and illuminate in ways more subtle and profound than do those of Martin Chuzzlewit.

The new dimensions and assuredness of Dickens' initial formulation of his themes are strikingly visualized in the cover design for Dombey and Son especially in contrast to that for Chuzzlewit. As usual, we cannot know how much guidance Dickens gave Phiz in the particular allegorical conception of the design, but he must have revealed a good deal about his plans for the novel; the wrapper includes references to Dombey's commercial career and the ultimate fall of his business, to his marriage, to the birth and schooling of Paul, to a young man setting out to sea and being shipwrecked, to the Wooden Midshipman, and to one of the last episodes in the as yet unwritten novel, Florence's care for her shattered father. although Dickens felt there was a little "too much in" the design, it is on the whole fairly unrevealing of the plot and conceived in traditional imagery and structure. There is no reason to think that Browne could not, given the requisite hints about Dombey's personality and the commercial themes of the novel, have composed out of his own imagination and stock of visual ideas the central allegory as we have it.

The fool with cap and bells, lying on the ledger, is a traditional figure Phiz reverted to more than once in his monthly covers; here, the fool's pipesmoke "dreams" the rising and falling structure of the design. The proud Dombey sits above on a throne, but his Cash box and day book are supported by an edifice of ledgers which is no more substantial than the precarious structure of playing cards paralleling it on the right. A structure on the point of collapse will be hinted at in the Bleak House cover, but here it is the most effective element in a design which is otherwise full of details that could have meant little at first to the original readers. When the novel was completed, Browne produced an allegorical frontispiece more closely related to the body of the novel, yet it omitted the commercial theme altogether. Thus it is difficult to say whether we should consider the two designs complementary or must rather conclude that there is some disjunction of purpose. The commercial theme as such is never adverted to again in the plates to this novel, whose subjects, as usual, Dickens specified; but careful reading of the plates and their interconnections shows that they do emphasize and complement Dickens' social vision.

Kim wrote: "

Monthly Wrapper

Commentary:

Dickens' seventh novel is at once less complicated and more complex than his sixth. Instead of Martin Chuzzlewit's proliferation of subplots and groups of characters..."

Hi Kim

And so we come to the end of D&S, and with that are presented with the frontispiece and the opportunity to decode it.

Thank you for including it in this week’s recaps. The frontispiece seems like a jigsaw of images. What relates to what? Is there a logical sequence, order, or format to the separate images? Can we “read” the novel from the images? To what extent is the frontispiece allegorical?

It would be wonderful for the Curiosities to gather in The Railway Arms one evening to talk about, speculate, and try to decode it. Alas, that’s not possible. If only there was a detailed record of the Browne - Dickens conversations and letters that would let readers understand their creative process in more detail.

Monthly Wrapper

Commentary:

Dickens' seventh novel is at once less complicated and more complex than his sixth. Instead of Martin Chuzzlewit's proliferation of subplots and groups of characters..."

Hi Kim

And so we come to the end of D&S, and with that are presented with the frontispiece and the opportunity to decode it.

Thank you for including it in this week’s recaps. The frontispiece seems like a jigsaw of images. What relates to what? Is there a logical sequence, order, or format to the separate images? Can we “read” the novel from the images? To what extent is the frontispiece allegorical?

It would be wonderful for the Curiosities to gather in The Railway Arms one evening to talk about, speculate, and try to decode it. Alas, that’s not possible. If only there was a detailed record of the Browne - Dickens conversations and letters that would let readers understand their creative process in more detail.

I'm so glad that Dombey redeemed himself and that he and Florence can enjoy a happy family life. I like too that Edith bowed out with dignity. This was a good novel, a big improvement from the previous ones (even though I liked them too!). I like how Dickens developed the main characters more and didn't bloat the novel with unimportant side characters. I found it much easier to engage with the characters this way.

I'm so glad that Dombey redeemed himself and that he and Florence can enjoy a happy family life. I like too that Edith bowed out with dignity. This was a good novel, a big improvement from the previous ones (even though I liked them too!). I like how Dickens developed the main characters more and didn't bloat the novel with unimportant side characters. I found it much easier to engage with the characters this way.

I'm afraid I still can't warm to Dombey, and I feel that he got a happy ending he didn't deserve. He behaved badly towards everyone, even when they forgave again and again like Florence.

I'm afraid I still can't warm to Dombey, and I feel that he got a happy ending he didn't deserve. He behaved badly towards everyone, even when they forgave again and again like Florence.Maybe he didn't know any better and was simply emotionally stunted - I do think that he just didn't appreciate how his behaviour effected Florence (apart from the blow). It would be interesting to know more about his own childhood now.

I suppose he was very much a product of the age, when small boys were packed off to boarding school and small girls were largely ignored in terms of education etc.

And I suppose his awakening in terms of enjoying his grandchildren was the final chapter in his development from cold, money-loving tyrant to warm-hearted and benevolent figure.

I did like Feenix's calling Carker as Barker, because I always felt like the constant flashing of teeth was meant to make Carker appear like a wolf.

From The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster:

In the first enjoyment of writing after his long rest, to which a former letter has referred, he had over-written his number by nearly a fifth; and upon his proposal to transfer the fourth chapter to his second number, replacing it by another of fewer pages, I had to object that this might damage his interest at starting. Thus he wrote on the 7th of August:

". . . I have received your letter to-day with the greatest delight, and am overjoyed to find that you think so well of the number. I thought well of it myself, and that it was a great plunge into a story; but I did not know how far I might be stimulated by my paternal affection. . . . What should you say, for a notion of the illustrations, to 'Miss Tox introduces the Party?' and 'Mr. Dombey and family?' meaning Polly Toodle, the baby, Mr. Dombey, and little Florence: whom I think it would be well to have. Walter, his uncle, and Captain Cuttle, might stand over. It is a great question with me, now, whether I had not better take this last chapter bodily out, and make it the last chapter of the second number; writing some other new one to close the first number. I think it would be impossible to take out six pages without great pangs. Do you think such a proceeding as I suggest would weaken number one very much? I wish you would tell me, as soon as you can after receiving this, what your opinion is on the point. If you thought it would weaken the first number, beyond the counterbalancing advantage of strengthening the second, I would cut down somehow or other, and let it go. I shall be anxious to hear your opinion. In the meanwhile I will go on with the second, which I have just begun. I have not been quite myself since we returned from Chamounix, owing to the great heat."

Two days later:

"I have begun a little chapter to end the first number, and certainly think it will be well to keep the ten pages of Wally and Co. entire for number two. But this is still subject to your opinion, which I am very anxious to know. I have not been in writing cue all the week; but really the weather has rendered it next to impossible to work."

Four days later:

"I shall send you with this (on the chance of your being favourable to that view of the subject) a small chapter to close the first number, in lieu of the Solomon Gills one. I have been hideously idle all the week, and have done nothing but this trifling interloper: but hope to begin again on Monday—ding dong. . . . The inkstand is to be cleaned out to-night, and refilled, preparatory to execution. I trust I may shed a good deal of ink in the next fortnight."

Then, the day following, on arrival of my letter, he submitted to a hard necessity.

"I received yours to-day. A decided factor to me! I had been counting, alas! with a miser's greed, upon the gained ten pages. . . No matter. I have no doubt you are right, and strength is everything. The addition of two lines to each page, or something less,—coupled with the enclosed cuts, will bring it all to bear smoothly. In case more cutting is wanted, I must ask you to try your hand. I shall agree to whatever you propose."

These cuttings, absolutely necessary as they were, were not without much disadvantage; and in the course of them he had to sacrifice a passage foreshadowing his final intention as to Dombey. It would have shown, thus early, something of the struggle with itself that such pride must always go through; and I think it worth preserving in a note.

In the first enjoyment of writing after his long rest, to which a former letter has referred, he had over-written his number by nearly a fifth; and upon his proposal to transfer the fourth chapter to his second number, replacing it by another of fewer pages, I had to object that this might damage his interest at starting. Thus he wrote on the 7th of August:

". . . I have received your letter to-day with the greatest delight, and am overjoyed to find that you think so well of the number. I thought well of it myself, and that it was a great plunge into a story; but I did not know how far I might be stimulated by my paternal affection. . . . What should you say, for a notion of the illustrations, to 'Miss Tox introduces the Party?' and 'Mr. Dombey and family?' meaning Polly Toodle, the baby, Mr. Dombey, and little Florence: whom I think it would be well to have. Walter, his uncle, and Captain Cuttle, might stand over. It is a great question with me, now, whether I had not better take this last chapter bodily out, and make it the last chapter of the second number; writing some other new one to close the first number. I think it would be impossible to take out six pages without great pangs. Do you think such a proceeding as I suggest would weaken number one very much? I wish you would tell me, as soon as you can after receiving this, what your opinion is on the point. If you thought it would weaken the first number, beyond the counterbalancing advantage of strengthening the second, I would cut down somehow or other, and let it go. I shall be anxious to hear your opinion. In the meanwhile I will go on with the second, which I have just begun. I have not been quite myself since we returned from Chamounix, owing to the great heat."

Two days later:

"I have begun a little chapter to end the first number, and certainly think it will be well to keep the ten pages of Wally and Co. entire for number two. But this is still subject to your opinion, which I am very anxious to know. I have not been in writing cue all the week; but really the weather has rendered it next to impossible to work."

Four days later:

"I shall send you with this (on the chance of your being favourable to that view of the subject) a small chapter to close the first number, in lieu of the Solomon Gills one. I have been hideously idle all the week, and have done nothing but this trifling interloper: but hope to begin again on Monday—ding dong. . . . The inkstand is to be cleaned out to-night, and refilled, preparatory to execution. I trust I may shed a good deal of ink in the next fortnight."

Then, the day following, on arrival of my letter, he submitted to a hard necessity.

"I received yours to-day. A decided factor to me! I had been counting, alas! with a miser's greed, upon the gained ten pages. . . No matter. I have no doubt you are right, and strength is everything. The addition of two lines to each page, or something less,—coupled with the enclosed cuts, will bring it all to bear smoothly. In case more cutting is wanted, I must ask you to try your hand. I shall agree to whatever you propose."

These cuttings, absolutely necessary as they were, were not without much disadvantage; and in the course of them he had to sacrifice a passage foreshadowing his final intention as to Dombey. It would have shown, thus early, something of the struggle with itself that such pride must always go through; and I think it worth preserving in a note.

From The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster:

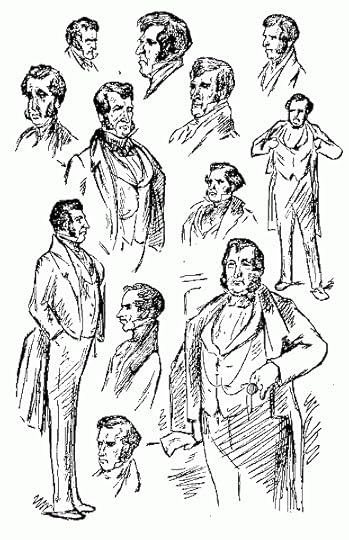

Several letters now expressed his anxiety and care about the illustrations. A nervous dread of caricature in the face of his merchant-hero, had led him to indicate by a living person the type of city-gentleman he would have had the artist select; and this is all he meant by his reiterated urgent request,

"I do wish he could get a glimpse of A, for he is the very Dombey."

But as the glimpse of A was not to be had, it was resolved to send for selection by himself glimpses of other letters of the alphabet, actual heads as well as fanciful ones; and the sheet full I sent out, which he returned when the choice was made, I here reproduce in fac-simile. In itself amusing, it has now the important use of showing, once for all, in regard to Dickens's intercourse with his artists, that they certainly had not an easy time with him; that, even beyond what is ordinary between author and illustrator, his requirements were exacting; that he was apt, as he has said himself, to build up temples in his mind not always makeable with hands; that in the results he had rarely anything but disappointment; and that of all notions to connect with him the most preposterous would be that which directly reversed these relations, and depicted him as receiving from any artist the inspiration he was always vainly striving to give. An assertion of this kind was contradicted in my first volume; but it has since been repeated so explicitly, that to prevent any possible misconstruction from a silence I would fain have persisted in, the distasteful subject is again reluctantly introduced.

Several letters now expressed his anxiety and care about the illustrations. A nervous dread of caricature in the face of his merchant-hero, had led him to indicate by a living person the type of city-gentleman he would have had the artist select; and this is all he meant by his reiterated urgent request,

"I do wish he could get a glimpse of A, for he is the very Dombey."

But as the glimpse of A was not to be had, it was resolved to send for selection by himself glimpses of other letters of the alphabet, actual heads as well as fanciful ones; and the sheet full I sent out, which he returned when the choice was made, I here reproduce in fac-simile. In itself amusing, it has now the important use of showing, once for all, in regard to Dickens's intercourse with his artists, that they certainly had not an easy time with him; that, even beyond what is ordinary between author and illustrator, his requirements were exacting; that he was apt, as he has said himself, to build up temples in his mind not always makeable with hands; that in the results he had rarely anything but disappointment; and that of all notions to connect with him the most preposterous would be that which directly reversed these relations, and depicted him as receiving from any artist the inspiration he was always vainly striving to give. An assertion of this kind was contradicted in my first volume; but it has since been repeated so explicitly, that to prevent any possible misconstruction from a silence I would fain have persisted in, the distasteful subject is again reluctantly introduced.

From The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster:

Thus ran the letter of the 3rd of October:

"Miss Tox's colony I will smash. Walter's allusion to Carker (would you take it all out?) shall be dele'd. Of course, you understand the man! I turned that speech over in my mind; but I thought it natural that a boy should run on, with such a subject, under the circumstances: having the matter so presented to him. . . . I thought of the possibility of malice on christening points of faith, and put the drag on as I wrote. Where would you make the insertion, and to what effect? That shall be done too. I want you to think the number sufficiently good stoutly to back up the first. It occurs to me—might not your doubt about the christening be a reason for not making the ceremony the subject of an illustration? Just turn this over. Again: if I could do it (I shall have leisure to consider the possibility before I begin), do you think it would be advisable to make number three a kind of half-way house between Paul's infancy, and his being eight or nine years old?—In that case I should probably not kill him until the fifth number. Do you think the people so likely to be pleased with Florence, and Walter, as to relish another number of them at their present age? Otherwise, Walter will be two or three and twenty, straightway. I wish you would think of this. . . . I am sure you are right about the christening. It shall be artfully and easily amended. . . . Eh?"

Thus ran the letter of the 3rd of October:

"Miss Tox's colony I will smash. Walter's allusion to Carker (would you take it all out?) shall be dele'd. Of course, you understand the man! I turned that speech over in my mind; but I thought it natural that a boy should run on, with such a subject, under the circumstances: having the matter so presented to him. . . . I thought of the possibility of malice on christening points of faith, and put the drag on as I wrote. Where would you make the insertion, and to what effect? That shall be done too. I want you to think the number sufficiently good stoutly to back up the first. It occurs to me—might not your doubt about the christening be a reason for not making the ceremony the subject of an illustration? Just turn this over. Again: if I could do it (I shall have leisure to consider the possibility before I begin), do you think it would be advisable to make number three a kind of half-way house between Paul's infancy, and his being eight or nine years old?—In that case I should probably not kill him until the fifth number. Do you think the people so likely to be pleased with Florence, and Walter, as to relish another number of them at their present age? Otherwise, Walter will be two or three and twenty, straightway. I wish you would think of this. . . . I am sure you are right about the christening. It shall be artfully and easily amended. . . . Eh?"

From The Life of Charles Dickens

There was one drawback. The second number had gone out to him, and the illustrations he found to be so "dreadfully bad" that they made him "curl his legs up." They made him also more than usually anxious in regard to a special illustration on which he set much store, for the part he had in hand.

The first chapter of it was sent me only four days later (nearly half the entire part, so freely his fancy was now flowing and overflowing), with intimation for the artist:

"The best subject for Browne will be at Mrs. Pipchin's; and if he liked to do a quiet odd thing, Paul, Mrs. Pipchin, and the Cat, by the fire, would be very good for the story. I earnestly hope he will think it worth a little extra care. The second subject, in case he shouldn't take a second from that same chapter, I will shortly describe as soon as I have it clearly (to-morrow or next day), and send it to you by post."

The result was not satisfactory; but as the artist more than redeemed it in the later course of the tale, and the present disappointment was mainly the incentive to that better success, the mention of the failure here will be excused for what it illustrates of Dickens himself.

"I am really distressed by the illustration of Mrs. Pipchin and Paul. It is so frightfully and wildly wide of the mark. Good Heaven! in the commonest and most literal construction of the text, it is all wrong. She is described as an old lady, and Paul's 'miniature arm-chair' is mentioned more than once. He ought to be sitting in a little arm-chair down in the corner of the fireplace, staring up at her. I can't say what pain and vexation it is to be so utterly misrepresented. I would cheerfully have given a hundred pounds to have kept this illustration out of the book. He never could have got that idea of Mrs. Pipchin if he had attended to the text. Indeed I think he does better without the text; for then the notion is made easy to him in short description, and he can't help taking it in."

He felt the disappointment more keenly, because the conception of the grim old boarding-house keeper had taken back his thoughts to the miseries of his own child-life, and made her, as her prototype in verity was, a part of the terrible reality. I had forgotten, until I again read this letter of the 4th of November 1846, that he thus early proposed to tell me that story of his boyish sufferings which a question from myself, of some months later date, so fully elicited. He was now hastening on with the close of his third number, to be ready for departure to Paris.

There was one drawback. The second number had gone out to him, and the illustrations he found to be so "dreadfully bad" that they made him "curl his legs up." They made him also more than usually anxious in regard to a special illustration on which he set much store, for the part he had in hand.

The first chapter of it was sent me only four days later (nearly half the entire part, so freely his fancy was now flowing and overflowing), with intimation for the artist:

"The best subject for Browne will be at Mrs. Pipchin's; and if he liked to do a quiet odd thing, Paul, Mrs. Pipchin, and the Cat, by the fire, would be very good for the story. I earnestly hope he will think it worth a little extra care. The second subject, in case he shouldn't take a second from that same chapter, I will shortly describe as soon as I have it clearly (to-morrow or next day), and send it to you by post."

The result was not satisfactory; but as the artist more than redeemed it in the later course of the tale, and the present disappointment was mainly the incentive to that better success, the mention of the failure here will be excused for what it illustrates of Dickens himself.

"I am really distressed by the illustration of Mrs. Pipchin and Paul. It is so frightfully and wildly wide of the mark. Good Heaven! in the commonest and most literal construction of the text, it is all wrong. She is described as an old lady, and Paul's 'miniature arm-chair' is mentioned more than once. He ought to be sitting in a little arm-chair down in the corner of the fireplace, staring up at her. I can't say what pain and vexation it is to be so utterly misrepresented. I would cheerfully have given a hundred pounds to have kept this illustration out of the book. He never could have got that idea of Mrs. Pipchin if he had attended to the text. Indeed I think he does better without the text; for then the notion is made easy to him in short description, and he can't help taking it in."

He felt the disappointment more keenly, because the conception of the grim old boarding-house keeper had taken back his thoughts to the miseries of his own child-life, and made her, as her prototype in verity was, a part of the terrible reality. I had forgotten, until I again read this letter of the 4th of November 1846, that he thus early proposed to tell me that story of his boyish sufferings which a question from myself, of some months later date, so fully elicited. He was now hastening on with the close of his third number, to be ready for departure to Paris.

From The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster:

But soon he sprang up, as usual, more erect for the moment's pressure; and after not many days I heard that the number was as good as done. His letter was very brief, and told me that he had worked so hard the day before (Tuesday, the 12th of January), and so incessantly, night as well as morning, that he had breakfasted and lain in bed till midday. "I hope I have been very successful." There was but one small chapter more to write, in which he and his little friend were to part company for ever; and the greater part of the night of the day on which it was written, Thursday the 14th, he was wandering desolate and sad about the streets of Paris. I arrived there the following morning on my visit; and as I alighted from the malle-poste, a little before eight o'clock, found him waiting for me at the gate of the post-office bureau.

But soon he sprang up, as usual, more erect for the moment's pressure; and after not many days I heard that the number was as good as done. His letter was very brief, and told me that he had worked so hard the day before (Tuesday, the 12th of January), and so incessantly, night as well as morning, that he had breakfasted and lain in bed till midday. "I hope I have been very successful." There was but one small chapter more to write, in which he and his little friend were to part company for ever; and the greater part of the night of the day on which it was written, Thursday the 14th, he was wandering desolate and sad about the streets of Paris. I arrived there the following morning on my visit; and as I alighted from the malle-poste, a little before eight o'clock, found him waiting for me at the gate of the post-office bureau.

Kim wrote: "From The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster:

Several letters now expressed his anxiety and care about the illustrations. A nervous dread of caricature in the face of his merchant-hero, had le..."

Kim

Thank you so much for this information. I find the whole process of the weekly/monthly instalments fascinating. Unlike the vast majority of today’s novelists who have the advantage and leisure of novel-long editing help and support before their book reaches the market, Dickens was constantly under enormous pressure to turn out the required number of pages. Once printed in their weekly/ monthly format he had no place or chance to make significant alterations.

To keep up such a pace for two years really is amazing.

Several letters now expressed his anxiety and care about the illustrations. A nervous dread of caricature in the face of his merchant-hero, had le..."

Kim

Thank you so much for this information. I find the whole process of the weekly/monthly instalments fascinating. Unlike the vast majority of today’s novelists who have the advantage and leisure of novel-long editing help and support before their book reaches the market, Dickens was constantly under enormous pressure to turn out the required number of pages. Once printed in their weekly/ monthly format he had no place or chance to make significant alterations.

To keep up such a pace for two years really is amazing.

I was still a bit unsure of the significance of the sea/river and time themes that (I think) Peter told us to look out for. I spotted quite a few examples but couldn't work out the overall meaning.

I was still a bit unsure of the significance of the sea/river and time themes that (I think) Peter told us to look out for. I spotted quite a few examples but couldn't work out the overall meaning.

David wrote: "I was still a bit unsure of the significance of the sea/river and time themes that (I think) Peter told us to look out for. I spotted quite a few examples but couldn't work out the overall meaning."

David wrote: "I was still a bit unsure of the significance of the sea/river and time themes that (I think) Peter told us to look out for. I spotted quite a few examples but couldn't work out the overall meaning."Hi David,

Personally, I interpret the sea as a symbol for the afterlife or the great unknown, because that's where Florence's mom, young Paul, and even Walter went, when they disappeared from Florence's life. I interpret time as the constraints of earthly life, especially when Paul went to that hard school. These were definitely repetitive themes in the story. Very mysterious, but very interesting.

David wrote: "I was still a bit unsure of the significance of the sea/river and time themes that (I think) Peter told us to look out for. I spotted quite a few examples but couldn't work out the overall meaning."

Hi David

Yes, it was me that suggested we might like to take a look at the many occasions time and the sea/ocean are mentioned in the novel.

I’ll give you a recap of my own ideas and feelings. That does not mean it is the definitive or even a correct meaning, but it’s what I took away from the novel.

To me, Time seems to have a more prominent place in D&S than in earlier novels. Partly, I think this is because Dickens is more carefully planning and plotting out the novel. I found D&S to be very precise. As a reader, the constant references to time allow the reader to trace the development of character, the chronological space between different events, and even get insights or reminder cues to character. For example, Captain Cuttle and Sol Gill are consistently linked to the watches they personally own or incorporate in the business of the Wooden Midshipman. This both links the reader closer to the character and helps develop theme and motif. The Midshipman is not a thriving enterprise. This is partly due to the fact sailing is undergoing a major shift from wind power to steam. Navigation and sailing will always require instrumentation but steam power is the new reality. This is linked to the coming of the railway and how rail power is radically transforming transportation as well as the fabric of English society. Consider the enormous change symbolized by Stagg’s Gardens and how Mr Toodle through hard work and time is able to rise moderately in the ranks of railway staff.

I see the concept of time in the novel as linked to change. In this way the bottles of Madeira wine perhaps best document time. Each bottle marks a significant change in life. Each bottle allows those who drink it to mark the passage of time, and thus allows the readers the opportunity to celebrate the passage of time as well.

I agree with Alissa’s comments and insights on the symbolism and meaning of the sea/oceans. If we take a look at the final sentences in the novel Dickens writes:”

The voices of the waves speak low to him of Florence, day and night - plainest when he, his blooming daughter, and her husband, walk between then in the evening ... listening to their roar. They [the waves] speak to him of Florence and his altered heart; of Florence and their murmuring to her of the love, eternal and illimitable, extending still, beyond the sea, beyond the sky, to the invisible country far away.

Never from the mighty sea may voices rise too late, to become between us and the unseen region on the other shore! Better, far better, than they whispered of that region in our childish ears, and the swift river hurried us away!”

These sentences show how the sea is a vast place, and in its waves and sounds and currents flow both life and death which is “the unseen region on the other shore.”

In Chapter 16 of the novel titled “What the Waves were always saying” Paul Dombey dies. The end of Chapter 16 and the final sentences of the novel connects the sea to both life and death, and thus, to Time.

Hi David

Yes, it was me that suggested we might like to take a look at the many occasions time and the sea/ocean are mentioned in the novel.

I’ll give you a recap of my own ideas and feelings. That does not mean it is the definitive or even a correct meaning, but it’s what I took away from the novel.

To me, Time seems to have a more prominent place in D&S than in earlier novels. Partly, I think this is because Dickens is more carefully planning and plotting out the novel. I found D&S to be very precise. As a reader, the constant references to time allow the reader to trace the development of character, the chronological space between different events, and even get insights or reminder cues to character. For example, Captain Cuttle and Sol Gill are consistently linked to the watches they personally own or incorporate in the business of the Wooden Midshipman. This both links the reader closer to the character and helps develop theme and motif. The Midshipman is not a thriving enterprise. This is partly due to the fact sailing is undergoing a major shift from wind power to steam. Navigation and sailing will always require instrumentation but steam power is the new reality. This is linked to the coming of the railway and how rail power is radically transforming transportation as well as the fabric of English society. Consider the enormous change symbolized by Stagg’s Gardens and how Mr Toodle through hard work and time is able to rise moderately in the ranks of railway staff.

I see the concept of time in the novel as linked to change. In this way the bottles of Madeira wine perhaps best document time. Each bottle marks a significant change in life. Each bottle allows those who drink it to mark the passage of time, and thus allows the readers the opportunity to celebrate the passage of time as well.

I agree with Alissa’s comments and insights on the symbolism and meaning of the sea/oceans. If we take a look at the final sentences in the novel Dickens writes:”

The voices of the waves speak low to him of Florence, day and night - plainest when he, his blooming daughter, and her husband, walk between then in the evening ... listening to their roar. They [the waves] speak to him of Florence and his altered heart; of Florence and their murmuring to her of the love, eternal and illimitable, extending still, beyond the sea, beyond the sky, to the invisible country far away.

Never from the mighty sea may voices rise too late, to become between us and the unseen region on the other shore! Better, far better, than they whispered of that region in our childish ears, and the swift river hurried us away!”

These sentences show how the sea is a vast place, and in its waves and sounds and currents flow both life and death which is “the unseen region on the other shore.”

In Chapter 16 of the novel titled “What the Waves were always saying” Paul Dombey dies. The end of Chapter 16 and the final sentences of the novel connects the sea to both life and death, and thus, to Time.

Last week, we opened the last instalment of Dombey and Son, which was actually a double number, i.e. about twice its normal length, and we already found the narrator wind up things for most of the characters we have accompanied through their lives so far. Little remains to be told, as even Mrs. Pipchin was able to retire with, and on, her well-deserved chair, on which she might hopefully prosper. Still, the last bottle of Madeira from Old Sol’s vaults has not yet been uncorked, and neither has Edith Dombey been given a valedictory scene, which she has every right to, owning that she is one of the most interesting characters in the novel. So, after all, there is still some suspense here.

We learned that shortly after the reconciliation between Mr. Dombey and his daughter, the broken man leaves his splendidly mournful house, and now he is actually lingering at death’s door, carefully tendered by Florence. He is not a thankless patient because he now tells Florence that he had well noticed how she was ”ministering at the little bedside [of her dying brother]”, and in his feverish ramblings he not only asks himself the childish question, Paul’s question, “What is money?” but he also repeatedly counts his children, arriving at two each time. His mind now often centres on Florence, but he is also delighted when he sees Susan at his bedside, whom he readily forgives for what she said to him the last time they met – although here I am not so sure whether Susan actually needed so much forgiving for telling the truth.

One day, Florence is called on by a gentleman who wants to take her to somebody who wants to speak to her – and since Walter strongly recommends that she go there, she does, all the more so since she recognizes Cousin Feenix in her caller. Underneath Cousin Feenix’s manner of levity, Florence senses a certain anxiety, and it is actually quite obvious what intentions led the old man into making his call. When they arrive at their destination, Florence’s forebodings are confirmed in that she is suddenly standing face to face with her stepmother, who was obviously not aware that Cousin Feenix was about to bring about this meeting, which actually takes place in the house where the marriage between Edith and Dombey had been celebrated. This is what we get to know about the house:

Will any good come of a meeting in such a house? Edith is set eyes on by Florence with her head ”turned away towards the dying light”, as though there were only darkness before her in her remaining path through life, and when the two women are facing each other, we get this:

Florence offers Edith to carry her request for pardon to her father, who, as she says, is sure to grant it, being such a sick and changed man now, but there is no word from Edith at first. It is actually Florence’s pardon that Edith asks first of all, feeling that she has also cast a stain upon her name and her child’s. Florence grants this pardon readily, and renews her offer with regard to her father, but there is still no reply from Edith. Finally, Edith tells Florence that she is guilty of a lot of things, such as pride and passion, but that she has never been guilty of adultery. She also adds that knowing Florence had for some time effected a change in her, and here Cousin Feenix chips in, corroborating Edith’s claim that she had never been entangled with Carker and saying that his family is also to blame for not having paid more attention to her and left her wholly to her mother, and then he entreats Edith not to stop midway because that would simply be wrong. It is then that Edith relents to Dombey, whom she hears is a changed man now, and that she says she wishes they might never have met because of the things she was bound to do to him. Some of her final words before the end of the interview are,

In other words, it’s their love for Florence that unites them now. At the close of the interview – Edith and her relative are going to spend the rest of their lives on the continent, where life is cheaper –, Cousin Feenix tells Florence that ”’[…] everything would have gone on pretty smoothly […]’ if it had not been for Carker, or Barker, as he calls him, and that he will now act as a father for Edith.

THOUGHTS AND QUESTIONS

Did you expect this outcome of the conversation, and are you satisfied with it? Or would you have preferred Edith and Dombey to meet once again and talked things over? The bottle of Madeira is not yet opened – would you have liked Edith to have partaken in it?

Interestingly, both Edith and Florence now have a father – or some sort of father ersatz – and it remains to be seen how is taking care of whom. Cousin Feenix might think that he is looking after Edith but if you take a look at his unstable legs you might think that before long, Edith will play the protective part in that duo. Are you satisfied with this outcome?

What do you think of Feenix’s remark that had it not been for Carker, the marriage might still have gone smoothly? What might going smoothly mean in Cousin Feenix’s eyes?