Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit - Group Read 2

>

Little Dorrit II: Chapters 23 - 34

This is a list of all the chapters in this thread, beginning with Second book: chapter 23, which is the first chapter in Charles Dickens's original monthly installment 17. Clicking on each chapter will automatically link you to the summary for that chapter:

This is a list of all the chapters in this thread, beginning with Second book: chapter 23, which is the first chapter in Charles Dickens's original monthly installment 17. Clicking on each chapter will automatically link you to the summary for that chapter:Second Book: Riches

XVII – April 1857 (chapters 23–26)

Book II: Chapter 23 (Message 3)

Book II: Chapter 24 (Message 13)

Book II: Chapter 25 (Message 35)

Book II: Chapter 26 (Message 51)

XVIII – May 1857 (chapters 27–29)

Book II: Chapter 27 (Message 63)

Book II: Chapter 28 (Message 73)

Book II: Chapter 29 (Message 98)

XIX-XX – June 1857 (chapters 30–34)

Book II: Chapter 30 (Message 107)

Book II: Chapter 31 (Message 131)

Book II: Chapter 32 (Message 146)

Book II: Chapter 33 (Message 159)

Book II: Chapter 34 (Message 177)

message 3:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 15, 2020 09:16AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Book II: Chapter 23:

We are now at the beginning of installment 17 and the action follows straight on from the previous chapter. Left alone, Arthur wearily tries to stop himself from worrying about the mystery which consumes his thoughts:

“the one subject that he endeavoured with all his might to rid himself of, and that he could not fly from.”

What is the mystery to do with his family’s business, and what reason could there be, for such a man as Blandois to visit the Clennam house? He knows that it had been of a secret nature, and that his mother, that indomitable figure, had been submissive to him, and afraid of him. His old vague fears haunt him, and he is sure there is evil in this, but his mother is unapproachable. After a day of worry, Arthur decides to try to learn something from his only friend of old, Affery.

When he arrives at his mother’s house, he finds Flintwinch on the doorstep:

“The smoke came crookedly out of Mr Flintwinch’s mouth, as if it circulated through the whole of his wry figure and came back by his wry throat, before coming forth to mingle with the smoke from the crooked chimneys and the mists from the crooked river.”

He asks about the foreign gentleman, but Flintwinch tells him nothing. Arthur begins to imagine that Flintwinch may have killed Blandois, as although he is small and bent, he is “as tough as an old yew-tree, and as crusty as an old jackdaw”. Flintwinch demands to know why Arthur is staring at him, and Arthur apologises, saying that he hates to see any connection between his mother and Blandois, made public, as the placards are doing. Flintwinch is unmoved, and philosophical about it. He say that Mr. Casby and Flora Finching are visiting Mrs. Clennam, and leads Arthur upstairs to his mother’s room. It is becoming very difficult for Arthur to have a private conversation with Affery.

Arthur asks if he may wheel his mother to her desk, and Flora chatters even louder and faster than usual, thereby indicating that she is aware their conversation will be of a confidential nature, and respects it. His mother however, ignores the fact that Arthur is speaking in a low voice, and to Arthur’s consternation, speaks so that everyone may hear. Arthur tells his mother that Blandois has been in prison, which does not surprise her, but when he tells her he had been charged with murder:

“She started at the word, and her looks expressed her natural horror.”

She quickly recovers however, and challenges the facts, saying that Arthur would prefer to believe a fellow prisoner’s word than her and Flintwinch’s. She seems to view this as a triumph, refuses to accept any help that Arthur could offer her, and denies that there is any secret. Arthur tries one last time:

“Will you entrust me with no confidence, no charge, no explanation? Will you take no counsel with me? Will you not let me come near you?”

but she rebuffs him, saying that he voluntarily gave up his position, and now Flintwinch occupies it. Flintwinch has been listening all the while, but now, to Arthur’s horror, Mrs. Clennam starts to tell Mr. Casby what Arthur said. He manages to stop her, but she makes a point of forcing him to say that he wants it to be a secret. She is imperious and elated:

“Observe, then! It is you who make this a secret … and not I. It is you, Arthur, who bring here doubts and suspicions … and secrets here. What is it to me, do you think, where the man has been, or what he has been? … The whole world may know it, if they care to know it; it is nothing to me.”

Flintwinch looks elated too, and the narrator comments wryly “which most assuredly was not inspired by Flora.”

Arthur decides there is nothing left but to appeal to his old ally Affery, even thought she seems to be under the others’ thumbs. But how can he get her alone? She is still sitting in a corner, with the toasting-fork in her hand:

“guarding herself from approach with that symbolical instrument of hers; so that, when a word or two had been addressed to her by Flora, or even by the bottle-green patriarch himself, she had warded off conversation with the toasting-fork like a dumb woman.”

Arthur has an inspiration, and whispers to Flora to ask if she may see the house. Flora is delighted, perhaps seeing romantic possibilities in this:

“always in fluctuating expectation of the time when Clennam would renew his boyhood and be madly in love with her again”. She immediately adopts her role, and reminisces about the old times she spent there. Flora continues to chatter on, asking if she may see round, for old times’ sake, and Arthur suggests that Affery lights the way.

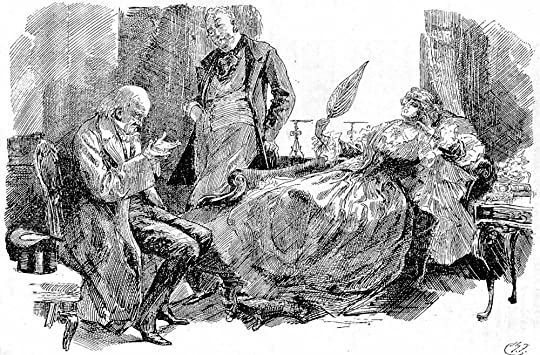

'Flora's Tour of Inspection' - Phiz

There follows a ridiculous and highly amusing charade, where Flora hangs on to Arthur’s arm down the stairs:

“wherever it became darker than elsewhere, Flora became heavier, and that when the house was lightest she was too”

and Flintwinch, to Arthur’s annoyance, follows behind. Arthur manages to tell Affery that he wants to speak to her, and Flora takes the initiative, claiming to want to see inside an old closet. But it is of no use. Affery, terrified that Flintwinch observes them, throws her apron over her head. When Arthur tries to reassure her, she say it is even worse when it is dark:

“Because the house is full of mysteries and secrets; because it’s full of whisperings and counsellings; because it’s full of noises. There never was such a house for noises. I shall die of ‘em, if Jeremiah don’t strangle me first. As I expect he will … noises is the secrets, rustlings and stealings about, tremblings, treads overhead and treads underneath.”

Arthur manages to ask Affery about Blandois, but she says, still terrified of her husband, that she has only seen him twice. She begs Arthur to go away, and say she has been in a dream for ever so long, but she will not say any more.

Affery, Arthur and Flora - James Mahoney

Flintwinch appears and relights the candle, taking umbrage at seeing his wife with her apron over her head. He charges at Affery, and twists her nose through her apron, as hard as he can.

They eventually return to Mrs. Clennam’s room, where she is in conversation with the Patriach, who continues to give out his peculiarly deceptive air of benevolence.

We are now at the beginning of installment 17 and the action follows straight on from the previous chapter. Left alone, Arthur wearily tries to stop himself from worrying about the mystery which consumes his thoughts:

“the one subject that he endeavoured with all his might to rid himself of, and that he could not fly from.”

What is the mystery to do with his family’s business, and what reason could there be, for such a man as Blandois to visit the Clennam house? He knows that it had been of a secret nature, and that his mother, that indomitable figure, had been submissive to him, and afraid of him. His old vague fears haunt him, and he is sure there is evil in this, but his mother is unapproachable. After a day of worry, Arthur decides to try to learn something from his only friend of old, Affery.

When he arrives at his mother’s house, he finds Flintwinch on the doorstep:

“The smoke came crookedly out of Mr Flintwinch’s mouth, as if it circulated through the whole of his wry figure and came back by his wry throat, before coming forth to mingle with the smoke from the crooked chimneys and the mists from the crooked river.”

He asks about the foreign gentleman, but Flintwinch tells him nothing. Arthur begins to imagine that Flintwinch may have killed Blandois, as although he is small and bent, he is “as tough as an old yew-tree, and as crusty as an old jackdaw”. Flintwinch demands to know why Arthur is staring at him, and Arthur apologises, saying that he hates to see any connection between his mother and Blandois, made public, as the placards are doing. Flintwinch is unmoved, and philosophical about it. He say that Mr. Casby and Flora Finching are visiting Mrs. Clennam, and leads Arthur upstairs to his mother’s room. It is becoming very difficult for Arthur to have a private conversation with Affery.

Arthur asks if he may wheel his mother to her desk, and Flora chatters even louder and faster than usual, thereby indicating that she is aware their conversation will be of a confidential nature, and respects it. His mother however, ignores the fact that Arthur is speaking in a low voice, and to Arthur’s consternation, speaks so that everyone may hear. Arthur tells his mother that Blandois has been in prison, which does not surprise her, but when he tells her he had been charged with murder:

“She started at the word, and her looks expressed her natural horror.”

She quickly recovers however, and challenges the facts, saying that Arthur would prefer to believe a fellow prisoner’s word than her and Flintwinch’s. She seems to view this as a triumph, refuses to accept any help that Arthur could offer her, and denies that there is any secret. Arthur tries one last time:

“Will you entrust me with no confidence, no charge, no explanation? Will you take no counsel with me? Will you not let me come near you?”

but she rebuffs him, saying that he voluntarily gave up his position, and now Flintwinch occupies it. Flintwinch has been listening all the while, but now, to Arthur’s horror, Mrs. Clennam starts to tell Mr. Casby what Arthur said. He manages to stop her, but she makes a point of forcing him to say that he wants it to be a secret. She is imperious and elated:

“Observe, then! It is you who make this a secret … and not I. It is you, Arthur, who bring here doubts and suspicions … and secrets here. What is it to me, do you think, where the man has been, or what he has been? … The whole world may know it, if they care to know it; it is nothing to me.”

Flintwinch looks elated too, and the narrator comments wryly “which most assuredly was not inspired by Flora.”

Arthur decides there is nothing left but to appeal to his old ally Affery, even thought she seems to be under the others’ thumbs. But how can he get her alone? She is still sitting in a corner, with the toasting-fork in her hand:

“guarding herself from approach with that symbolical instrument of hers; so that, when a word or two had been addressed to her by Flora, or even by the bottle-green patriarch himself, she had warded off conversation with the toasting-fork like a dumb woman.”

Arthur has an inspiration, and whispers to Flora to ask if she may see the house. Flora is delighted, perhaps seeing romantic possibilities in this:

“always in fluctuating expectation of the time when Clennam would renew his boyhood and be madly in love with her again”. She immediately adopts her role, and reminisces about the old times she spent there. Flora continues to chatter on, asking if she may see round, for old times’ sake, and Arthur suggests that Affery lights the way.

'Flora's Tour of Inspection' - Phiz

There follows a ridiculous and highly amusing charade, where Flora hangs on to Arthur’s arm down the stairs:

“wherever it became darker than elsewhere, Flora became heavier, and that when the house was lightest she was too”

and Flintwinch, to Arthur’s annoyance, follows behind. Arthur manages to tell Affery that he wants to speak to her, and Flora takes the initiative, claiming to want to see inside an old closet. But it is of no use. Affery, terrified that Flintwinch observes them, throws her apron over her head. When Arthur tries to reassure her, she say it is even worse when it is dark:

“Because the house is full of mysteries and secrets; because it’s full of whisperings and counsellings; because it’s full of noises. There never was such a house for noises. I shall die of ‘em, if Jeremiah don’t strangle me first. As I expect he will … noises is the secrets, rustlings and stealings about, tremblings, treads overhead and treads underneath.”

Arthur manages to ask Affery about Blandois, but she says, still terrified of her husband, that she has only seen him twice. She begs Arthur to go away, and say she has been in a dream for ever so long, but she will not say any more.

Affery, Arthur and Flora - James Mahoney

Flintwinch appears and relights the candle, taking umbrage at seeing his wife with her apron over her head. He charges at Affery, and twists her nose through her apron, as hard as he can.

They eventually return to Mrs. Clennam’s room, where she is in conversation with the Patriach, who continues to give out his peculiarly deceptive air of benevolence.

message 4:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 15, 2020 09:18AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

And a little more ...

Domestic Abuse:

Charles Dickens does not shy away from topics other Victorian writers sometimes avoid, and in this chapter we have some strong signals.

We've seen how frightened Affery is of Flintwinch, but so far she has seemed frightened of everything! Not only "those two clever ones", but also strange sounds in the house, and terrified of knowing anything at all about what might be going on. This seems to be the clearest indication to me, that she is a battered wife. When Jeremiah Flintwinch says - as he has on several occasions - that he is going to "give her a dose", it's not an empty threat. He is going to hurt her, and presumably Mrs. Clennam is party to this, but in her stern rigid beliefs, she turns a blind eye and does not care.

“Jeremiah come a dancing at me sideways, after I had let you out (he always comes a dancing at me sideways when he’s going to hurt me), and he said to me, “Now, Affery,” he said, “I am a coming behind you, my woman, and a going to run you up.” So he took and squeezed the back of my neck in his hand, till it made me open my mouth, and then he pushed me before him to bed, squeezing all the way. That’s what he calls running me up, he do. Oh, he’s a wicked one!’”

Domestic Abuse:

Charles Dickens does not shy away from topics other Victorian writers sometimes avoid, and in this chapter we have some strong signals.

We've seen how frightened Affery is of Flintwinch, but so far she has seemed frightened of everything! Not only "those two clever ones", but also strange sounds in the house, and terrified of knowing anything at all about what might be going on. This seems to be the clearest indication to me, that she is a battered wife. When Jeremiah Flintwinch says - as he has on several occasions - that he is going to "give her a dose", it's not an empty threat. He is going to hurt her, and presumably Mrs. Clennam is party to this, but in her stern rigid beliefs, she turns a blind eye and does not care.

“Jeremiah come a dancing at me sideways, after I had let you out (he always comes a dancing at me sideways when he’s going to hurt me), and he said to me, “Now, Affery,” he said, “I am a coming behind you, my woman, and a going to run you up.” So he took and squeezed the back of my neck in his hand, till it made me open my mouth, and then he pushed me before him to bed, squeezing all the way. That’s what he calls running me up, he do. Oh, he’s a wicked one!’”

I truly hate Flintwinch. The way he abuses Affery is unacceptable. I keep telling myself that abusing your wife was acceptable back then (even now people will turn a blind eye to it). But, I just want something really bad to happen to Flintwinch.

I truly hate Flintwinch. The way he abuses Affery is unacceptable. I keep telling myself that abusing your wife was acceptable back then (even now people will turn a blind eye to it). But, I just want something really bad to happen to Flintwinch. An interesting new thought is presented. Did Flintwinch kill Blandois? I do not know. I cannot get the timeline straight as to when we last saw Blandois. I think Flintwinch is capable of doing it, but why.

Debra, I agree with you about Flintwinch! I do believe too that even though abuseing your wife was allowed, there was a line that was not supposed to be crossed, such as Flintwinch half strangling Affery early in the book. I could see Flintwinch killing Blandois simply because he could not control him, but I can also see Blandois killing for the same reason.

Debra, I agree with you about Flintwinch! I do believe too that even though abuseing your wife was allowed, there was a line that was not supposed to be crossed, such as Flintwinch half strangling Affery early in the book. I could see Flintwinch killing Blandois simply because he could not control him, but I can also see Blandois killing for the same reason.

I also love the absurdity of Flora, and how she breaks the tension by playing along with Arthur's wishes :) The scene where she hangs on to Arthur, and "gets heavier" when it is darker and nobody can see, is an abiding image for me from this book :)

I'm wondering if Flintwinch and Blandois are working together swindling people. It's still a mystery where Flintwinch's double comes into the plot.

I'm wondering if Flintwinch and Blandois are working together swindling people. It's still a mystery where Flintwinch's double comes into the plot.I loved the scene with Arthur and Flora going down the stairs with her trying to ignite some romantic feelings by snuggling up to him. She's almost knocking Arthur down the stairs. Meanwhile Affrey is throwing her apron over her head.

The scene goes from comedy to tragedy in a heartbeat when Flintwinch grabs Affrey by the neck. Why don't the Clemmons talk to Flintwinch when they see this treatment of Affrey?

I don't think Mrs. Clemmon would care how Flintwinch treats his wife. And Arthur obviously has no control over what happens in this house.

I don't think Mrs. Clemmon would care how Flintwinch treats his wife. And Arthur obviously has no control over what happens in this house.

Debra wrote: "I truly hate Flintwinch. The way he abuses Affery is unacceptable. I keep telling myself that abusing your wife was acceptable back then (even now people will turn a blind eye to it). But, I just w..."

Debra wrote: "I truly hate Flintwinch. The way he abuses Affery is unacceptable. I keep telling myself that abusing your wife was acceptable back then (even now people will turn a blind eye to it). But, I just w..."Back at the end of chapter 17, after Mr. Dorrit visits Mrs. Clemmon's house, he dreams of finding Blandois buried in the cellar, then bricked up in a wall. I wonder if his subconscious was telling him something.

Bionic Jean wrote: "I also love the absurdity of Flora, and how she breaks the tension by playing along with Arthur's wishes :) The scene where she hangs on to Arthur, and "gets heavier" when it is darker and nobody c..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "I also love the absurdity of Flora, and how she breaks the tension by playing along with Arthur's wishes :) The scene where she hangs on to Arthur, and "gets heavier" when it is darker and nobody c..."I also found that scene very humorous.

Katy wrote: ".Back at the end of chapter 17, after Mr. Dorrit visits Mrs. Clemmon's house, he dreams of finding Blandois buried in the cellar, then bricked up in a wall. I wonder if his subconscious was telling him something."

Katy wrote: ".Back at the end of chapter 17, after Mr. Dorrit visits Mrs. Clemmon's house, he dreams of finding Blandois buried in the cellar, then bricked up in a wall. I wonder if his subconscious was telling him something."Oh my gosh. I forgot about this dream. At the time, I thought it was a strange thing to include in the story. Now, I think it might mean something.

message 13:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 16, 2020 10:51AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Book II: Chapter 24:

Three months have passed, and:

“That illustrious man and great national ornament, Mr Merdle, continued his shining course.”

The word going round is that he is in line for either a baronetcy, or even a peerage.

Rumour has it that Lord Decimus is troubled, because Mr. Merdle does not belong to the Barnacle family, even though his own credentials are not exemplary. But there are several other Barnacles whom he would prefer to be honoured.

Mr. and Mrs. Sparkler are now established in their own small house, in the much-sought after fashionable and expensive area of London, (which nevertheless smells of “yesterday’s soup and coach-horses”). Fanny has learned about the death of her father, and was genuinely upset for a while, before she had set her mind to ensuring that her mourning clothes would be just as flattering as Mrs. Merdle’s. Now she is bored.

It is a hot evening, and Fanny is reclining on a drawing-room sofa, with her husband in attendance. There follows an hilarious scene where Edmund desperately tries to do everything as his wife wishes, but only succeeds in exasperating her, with his compliments about how she, or his mother, is “a remarkably fine woman with no—”.

Fanny complains pettishly about how he is always in the way, and how large he is.

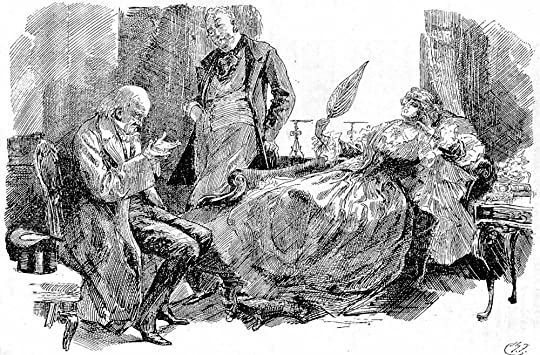

Fanny and Edmund Sparkler? - James Mahoney

A little abashed, Edmund says his nickname used to be “Quinbus Flestrin, Junior, or the Young Man Mountain.

‘You ought to have told me so before,’ Fanny complained“ and flounces around. Edmund keeps trying to please his wife, saying:

“everybody knows you are calculated to shine in society”

but this only provokes her into feeling sorry for herself, that she cannot go into society because of her father’s death:

“and my poor uncle’s—though I do not disguise from myself that the last was a happy release, for, if you are not presentable you had much better die—”

Eventually Fanny decides that Edmund had better go to bed. Edmund apologises “tender[ly] and earnest[ly]”, for whatever he might have done, and is graciously forgiven. Fanny brightens up when Edmund reminds her that Amy will soon be with them, although she will need bringing out of herself, and also: “my good little Mouse will have to be roused … from a low tendency which I know very well to be at the bottom of her heart.”. Fanny talks too about Edward (Tip)’s bout of Malaria Fever, which he had contracted abroad, and how it has delayed him in executing their father’s will. Not that it matters overmuch, she says, as her father had been very generous to her on her marriage. And she affectionately calls Amy “Amiable and dear little Twoshoes”.

Becoming a little tearful, Fanny finds that remembering how Edward had dismissed Mrs. General from the house immediately after their father’s death, cheers her up a little.

The chapter ends with an odd episode. Despite the late hour, they have an unexpected visitor. It is Mr. Merdle, who says more than once:

“as I happened to be out for a stroll, I thought I’d give you a call.”

'Mr Merdle pays the Sparklers a Visit' - Fred Barnard

He is asked if he has dined, and when he says he has not, is offered food, and a drink, but Mr. Merdle does not want anything. He looks very weary, as he:

“took the chair which Edmund Sparkler had offered him, and which he had hitherto been pushing slowly about before him, like a dull man with a pair of skates on for the first time, who could not make up his mind to start. He now put his hat upon another chair beside him, and, looking down into it as if it were some twenty feet deep”

Fanny is concerned, and says he must make sure he is not ill, whereupon “the master-mind of the age” announces:

“‘Oh! I am very well,’ replied Mr Merdle, after deliberating about it. ‘I am as well as I usually am. I am well enough. I am as well as I want to be.’”

Fanny mentions Mr. Dorrit, to which Mr. Merdle unaccountably comments:

“Quite a coincidence.”

Fanny continues regardless, saying what is on her mind: namely that she does not want Mrs. General to get anything from her father’s will. When Mr. Merdle expresses his opinion that she will not, Fanny is delighted.

'Mr Merdle becomes a borrower' - Phiz

Mr. Merdle decides it is time to go, and asks them for the loan of a penknife. Fanny is amused that such a man of business should ask them for this, but he say that he needs one, and knows they will have such a thing among their trinkets. He would prefer a tortoiseshell one to a mother of pearl one, and promises not to stain it with ink. They will have it back tomorrow, he assures them, and leaves.

Fanny watches him go, by now thoroughly vexed at being surrounded by dull, idiotic and lumpish people.

Three months have passed, and:

“That illustrious man and great national ornament, Mr Merdle, continued his shining course.”

The word going round is that he is in line for either a baronetcy, or even a peerage.

Rumour has it that Lord Decimus is troubled, because Mr. Merdle does not belong to the Barnacle family, even though his own credentials are not exemplary. But there are several other Barnacles whom he would prefer to be honoured.

Mr. and Mrs. Sparkler are now established in their own small house, in the much-sought after fashionable and expensive area of London, (which nevertheless smells of “yesterday’s soup and coach-horses”). Fanny has learned about the death of her father, and was genuinely upset for a while, before she had set her mind to ensuring that her mourning clothes would be just as flattering as Mrs. Merdle’s. Now she is bored.

It is a hot evening, and Fanny is reclining on a drawing-room sofa, with her husband in attendance. There follows an hilarious scene where Edmund desperately tries to do everything as his wife wishes, but only succeeds in exasperating her, with his compliments about how she, or his mother, is “a remarkably fine woman with no—”.

Fanny complains pettishly about how he is always in the way, and how large he is.

Fanny and Edmund Sparkler? - James Mahoney

A little abashed, Edmund says his nickname used to be “Quinbus Flestrin, Junior, or the Young Man Mountain.

‘You ought to have told me so before,’ Fanny complained“ and flounces around. Edmund keeps trying to please his wife, saying:

“everybody knows you are calculated to shine in society”

but this only provokes her into feeling sorry for herself, that she cannot go into society because of her father’s death:

“and my poor uncle’s—though I do not disguise from myself that the last was a happy release, for, if you are not presentable you had much better die—”

Eventually Fanny decides that Edmund had better go to bed. Edmund apologises “tender[ly] and earnest[ly]”, for whatever he might have done, and is graciously forgiven. Fanny brightens up when Edmund reminds her that Amy will soon be with them, although she will need bringing out of herself, and also: “my good little Mouse will have to be roused … from a low tendency which I know very well to be at the bottom of her heart.”. Fanny talks too about Edward (Tip)’s bout of Malaria Fever, which he had contracted abroad, and how it has delayed him in executing their father’s will. Not that it matters overmuch, she says, as her father had been very generous to her on her marriage. And she affectionately calls Amy “Amiable and dear little Twoshoes”.

Becoming a little tearful, Fanny finds that remembering how Edward had dismissed Mrs. General from the house immediately after their father’s death, cheers her up a little.

The chapter ends with an odd episode. Despite the late hour, they have an unexpected visitor. It is Mr. Merdle, who says more than once:

“as I happened to be out for a stroll, I thought I’d give you a call.”

'Mr Merdle pays the Sparklers a Visit' - Fred Barnard

He is asked if he has dined, and when he says he has not, is offered food, and a drink, but Mr. Merdle does not want anything. He looks very weary, as he:

“took the chair which Edmund Sparkler had offered him, and which he had hitherto been pushing slowly about before him, like a dull man with a pair of skates on for the first time, who could not make up his mind to start. He now put his hat upon another chair beside him, and, looking down into it as if it were some twenty feet deep”

Fanny is concerned, and says he must make sure he is not ill, whereupon “the master-mind of the age” announces:

“‘Oh! I am very well,’ replied Mr Merdle, after deliberating about it. ‘I am as well as I usually am. I am well enough. I am as well as I want to be.’”

Fanny mentions Mr. Dorrit, to which Mr. Merdle unaccountably comments:

“Quite a coincidence.”

Fanny continues regardless, saying what is on her mind: namely that she does not want Mrs. General to get anything from her father’s will. When Mr. Merdle expresses his opinion that she will not, Fanny is delighted.

'Mr Merdle becomes a borrower' - Phiz

Mr. Merdle decides it is time to go, and asks them for the loan of a penknife. Fanny is amused that such a man of business should ask them for this, but he say that he needs one, and knows they will have such a thing among their trinkets. He would prefer a tortoiseshell one to a mother of pearl one, and promises not to stain it with ink. They will have it back tomorrow, he assures them, and leaves.

Fanny watches him go, by now thoroughly vexed at being surrounded by dull, idiotic and lumpish people.

“Right or wrong, Rumour was very busy; and Lord Decimus, while he was, or was supposed to be, in stately excogitation of the difficulty, lent her some countenance by taking, on several public occasions, one of those elephantine trots of his through a jungle of overgrown sentences, waving Mr Merdle about on his trunk as Gigantic Enterprise, The Wealth of England, Elasticity, Credit, Capital, Prosperity, and all manner of blessings.”

I do have to say that, given the length of some of Charles Dickens's sentences, this seems to me a case of the pot calling the kettle black!

Of course Charles Dickens is far more entertaining, however :)

I do have to say that, given the length of some of Charles Dickens's sentences, this seems to me a case of the pot calling the kettle black!

Of course Charles Dickens is far more entertaining, however :)

It was clear to me that Mr. Merdle was depressed in this chapter- even Fanny notices that he "isn't well." Between his behavior and his lack of appetite that's clear. But when he asked for a penknife my first thought was "suicide," I think something has gone terribly wrong with all the money he's been handling and he's going to kill himself. In fact, I think he stopped in just to get the penknife. He's not a dropping in kind of man.

It was clear to me that Mr. Merdle was depressed in this chapter- even Fanny notices that he "isn't well." Between his behavior and his lack of appetite that's clear. But when he asked for a penknife my first thought was "suicide," I think something has gone terribly wrong with all the money he's been handling and he's going to kill himself. In fact, I think he stopped in just to get the penknife. He's not a dropping in kind of man.That made me read his reassurance that Mrs. General won't be getting any money differently. I don't think anyone who invested with him will be getting any money.

The penknife does seem like a strange thing to ask for. ??

The penknife does seem like a strange thing to ask for. ??I cannot decide if Fanny is upset about about the death of her father and her uncle and trying to hide it or only upset because she cannot be social when she is in morning.

What does Fanny mean when she tells Sparkler they cannot be alone together anymore?

Debra wrote: "The penknife does seem like a strange thing to ask for. ??

Debra wrote: "The penknife does seem like a strange thing to ask for. ??Debra, I think it's both.mmI think Fanny is genuinely upset about the death of her father and uncle but she's also Fanny- doesn't like sitting around being bored, while in mourning and she is taking it out on Sparkler whom she finds annoying in the best of circumstances. I think that's why she's says they says they can't be alone together. She just says whatever comes into her head.

Thanks, Anne. So, we still get to see some good in Fanny. She knows that she is taking it out on Sparkler and does not want to.

Thanks, Anne. So, we still get to see some good in Fanny. She knows that she is taking it out on Sparkler and does not want to.

Debra wrote: She knows that she is taking it out on Sparkler and does not want to."

Debra wrote: She knows that she is taking it out on Sparkler and does not want to."I don't know about that. LOL

Fanny says, "I find myself in a situation which to a certain extent disqualifies me for going into society. It's too bad, really!"

Fanny says, "I find myself in a situation which to a certain extent disqualifies me for going into society. It's too bad, really!"At first, I thought she was talking about being in mourning. But my book notes that the expression means that she is pregnant. That may explain her moodiness!

Connie, that's how I read it! Thanks for confirming what I suspected! It was her "to a certain extent" that made me think pregnancy rather than mourning, as if I remember correctly, those in mourning could go out, but could not dance. There were some really strict rules for mourning and pregnancy during this time!

Connie, that's how I read it! Thanks for confirming what I suspected! It was her "to a certain extent" that made me think pregnancy rather than mourning, as if I remember correctly, those in mourning could go out, but could not dance. There were some really strict rules for mourning and pregnancy during this time!

Connie, So she's pregnant? That makes her extra irritable. Pregnant women can't go into society? Interesting.

Connie, So she's pregnant? That makes her extra irritable. Pregnant women can't go into society? Interesting.

Jenny, but why can't she go into society if she doesn't dance? maybe it's both mourning and pregnancy. If she can't go into society for 9 months I think she'll kill her husband by then.

Jenny, but why can't she go into society if she doesn't dance? maybe it's both mourning and pregnancy. If she can't go into society for 9 months I think she'll kill her husband by then.

It's fortunate that Amy will be coming to stay with Fanny. It will provide some company for Fanny. Amy is such a nurturing person that she will probably enjoy helping Fanny.

It's fortunate that Amy will be coming to stay with Fanny. It will provide some company for Fanny. Amy is such a nurturing person that she will probably enjoy helping Fanny.

Connie wrote: "Fanny says, "I find myself in a situation which to a certain extent disqualifies me for going into society. It's too bad, really!"

Connie wrote: "Fanny says, "I find myself in a situation which to a certain extent disqualifies me for going into society. It's too bad, really!"At first, I thought she was talking about being in mourning. But ..."

My gosh. I did not suspect a pregnancy.

Debra wrote: "Connie wrote: "Fanny says, "I find myself in a situation which to a certain extent disqualifies me for going into society. It's too bad, really!"

Debra wrote: "Connie wrote: "Fanny says, "I find myself in a situation which to a certain extent disqualifies me for going into society. It's too bad, really!"At first, I thought she was talking about being in..."

I was a little surprised too. Fanny is usually a high energy person, but Fred Barnard's illustration shows her resting. It's going to be a long nine months for her husband too!

message 27:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 16, 2020 01:13PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

This is the first chapter where I feel sorry for Edmund Sparkler. He seemed such a nincompoop before, but he really can't help being so dim. Fanny really tries his patience here, but he stays attentive and supportive. And it makes very good entertainment.

Fanny is being complimentary about her sister, in calling her "Twoshoes". Today to say "little good twoshoes" can be meant sarcastically, as a criticism - that someone is excessively virtuous - but it comes from an old children's story from 1765 LINK HERE.

I was quite surprised to be told in this chapter than Edmund Sparkler is large - and was so as a child (I quoted it in my summary). Hardly any of Charles Dickens's illustrators have portrayed him that way - not even Phiz! So I have to conclude that until this chapter Charles Dickens had not finally decided, or he would have had a word with Hablot Knight Browne.

Sol Eytinge Junior did portray him as portly - but we didn't seem to like that one!

Fanny is being complimentary about her sister, in calling her "Twoshoes". Today to say "little good twoshoes" can be meant sarcastically, as a criticism - that someone is excessively virtuous - but it comes from an old children's story from 1765 LINK HERE.

I was quite surprised to be told in this chapter than Edmund Sparkler is large - and was so as a child (I quoted it in my summary). Hardly any of Charles Dickens's illustrators have portrayed him that way - not even Phiz! So I have to conclude that until this chapter Charles Dickens had not finally decided, or he would have had a word with Hablot Knight Browne.

Sol Eytinge Junior did portray him as portly - but we didn't seem to like that one!

Anne, the mourning is why she cannot dance. She would still be allowed to chaperone, or to sit aside with others in mourning, or who were sitting out a particular dance, ect.

Anne, the mourning is why she cannot dance. She would still be allowed to chaperone, or to sit aside with others in mourning, or who were sitting out a particular dance, ect. It was considered inappropriate for pregnant women who were showing to be out in public, though they could have female friends visit. Again, this is only if I remember correctly of course, but I think I am.

Jenny wrote: "Anne, the mourning is why she cannot dance. She would still be allowed to chaperone, or to sit aside with others in mourning, or who were sitting out a particular dance, ect.

Jenny wrote: "Anne, the mourning is why she cannot dance. She would still be allowed to chaperone, or to sit aside with others in mourning, or who were sitting out a particular dance, ect. It was considered ina..."

Jenny,

She's sitting at home because she's already showing? It's going to be a long pregnancy for her and everyone around her.

I can easily see Fanny having this baby and turning it right over to Amy to nurture. Something is definitely going on with Merdle. We have had questions about his health from the first introduction, but all his symptoms seem to be indicative of stress. I agree that Mrs. General might not be the only person who won't "get anything." I wonder if he is holding Fanny's money from her father. She is sure she will be fine even though Tip is delaying the will because she is already settled.

I can easily see Fanny having this baby and turning it right over to Amy to nurture. Something is definitely going on with Merdle. We have had questions about his health from the first introduction, but all his symptoms seem to be indicative of stress. I agree that Mrs. General might not be the only person who won't "get anything." I wonder if he is holding Fanny's money from her father. She is sure she will be fine even though Tip is delaying the will because she is already settled.

Jean, that's an interesting link about Goody Two Shoes. I've heard the expression, but never knew there was a children's book.

Jean, that's an interesting link about Goody Two Shoes. I've heard the expression, but never knew there was a children's book.

I thought this chapter was a good update of what's going on with all of the Dorrits. Although it is mainly about Fanny, we learn secondhand about the delay of the will, Tip's illness, and what the plan is for Amy. There must be something up with the will, as Dickens seems to be keeping us in suspense about it.

I thought this chapter was a good update of what's going on with all of the Dorrits. Although it is mainly about Fanny, we learn secondhand about the delay of the will, Tip's illness, and what the plan is for Amy. There must be something up with the will, as Dickens seems to be keeping us in suspense about it.Like some others, I am curious about the significance of the penknife, although I did not think of Mr. Merdle using it to kill himself. It is possible. I do believe that there is going to be a huge loss of money. A few chapter back, Dickens talked about how everyone is investing money with complete confidence in Mr. Merdle, but the chapter had ominous overtones.

message 34:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 17, 2020 04:38AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

It's probably best if we move straight on, as there will be LOTS of backstory to read here, and talk about today :)

message 35:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 17, 2020 04:50AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Book II: Chapter 25:

We now move to the dinner-party Mr. Merdle mentioned in the previous chapter. All the usual important people are there, including Bar, Bishop and Barnacle. It is at the Physician’s house, and the narrator wryly comments that the admiring:

“brilliant ladies about London … who would have been shocked to find themselves so close to him if they could have known on what sights those thoughtful eyes of his had rested within an hour or two, and near to whose beds, and under what roofs, his composed figure had stood.”

Because people know that the Physician sees them in all their different states and conditions, they tend to behave more openly and naturally at his parties. Mr. Merdle is missed, but not overmuch:

“Mr Merdle’s default left a Banquo’s chair at the table; but, if he had been there, he would have merely made the difference of Banquo in it, and consequently he was no loss.”

Bar begins flirting with Mrs. Merdle, in an attempt to find out which title has been offered to Mr. Merdle, but neither discovers anything through the conversation:

“’I should like it to be true; why should I deny that to you? You would know better, if I did!’

‘Just so,’ said Physician.

‘But whether it is all true, or partly true, or entirely false, I am wholly unable to say. It is a most provoking situation, a most absurd situation; but you know Mr Merdle, and are not surprised.’”

Having said which, Mrs. Merdle is handed into her carriage, and leaves. The other guests soon follow her example, and Physician settles down to read a book. And we are about to find out exactly what this attractive man, “who is admitted to some of us every day with our wigs and paint off”, who gives parties where everyone enjoys being a little more true to themselves than usual, will be faced with tonight.

It is almost midnight, when the Physician hears someone at the door. Answering it himself, his servants having retired to bed, he is surprised to discover a man from the warm baths (public baths) waiting “much agitated and out of breath”. The man asks him to accompany him, handing him a scrap of paper with the Physician’s name and address on. Recognising the writing, Physician hurries, and asks everyone to stand back when they arrive at the warm baths.

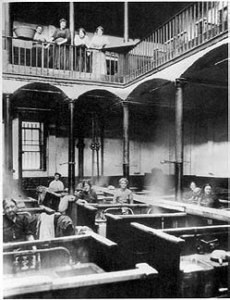

First public wash house in England - photo of it from 1914

“There was a bath in that corner, from which the water had been hastily drained off. Lying in it, as in a grave or sarcophagus, with a hurried drapery of sheet and blanket thrown across it, was the body of a heavily-made man, with an obtuse head, and coarse, mean, common features … The white marble at the bottom of the bath was veined with a dreadful red. On the ledge at the side, were an empty laudanum-bottle and a tortoise-shell handled penknife—soiled, but not with ink.”

The man’s throat has been cut, and the Physician sees among the man’s neat belonging on the table, the edge of a paper which is intended for his eyes. Those in charge of the warm baths do what is necessary, without any fuss. But the Physician, who has seen humanity in all its dreadful states, still has to sit down outside for a while, “feeling sick and faint”.

He decides to call at Bar’s house, seeing a light still on in the window. Bar is still at work despite the late hour, and is astonished to see his friend on the doorstep, and asks:

“‘What’s the matter?’

‘You asked me once what Merdle’s complaint was.’

‘Extraordinary answer! I know I did.’

‘I told you I had not found out.’

‘Yes. I know you did.’

‘I have found it out.’”

And now Bar knows too, as he can see the truth in Physician’s shocked face. They go together to break the news to Mrs. Merdle. When they are inside:

“The Chief Butler … approached the window with dignity; looking on at Physician’s news exactly as he had looked on at the dinners in that very room.

‘Mr Merdle is dead.’

‘I should wish,’ said the Chief Butler, ‘to give a month’s notice.’

‘Mr Merdle has destroyed himself.’”

adds the Physician, trying to provoke some kind of reaction, but even this news does not disturb the Chief Butler’s aplomb. He merely states with his dignified manner intact:

“I should wish to leave immediately … Sir, Mr Merdle never was the gentleman, and no ungentlemanly act on Mr Merdle’s part would surprise me.”

Mrs. Merdle is reported by Physician to be bearing the part of the news she has been told well enough. As Bar and Physician make their way back to their respective homes, the narrator comments:

“if all those hundreds and thousands of beggared people who were yet asleep could only know, as they two spoke, the ruin that impended over them, what a fearful cry against one miserable soul would go up to Heaven!”

The news gets round the next day like wildfire, and there are many strange and wonderful rumours as to what had caused Mr. Merdle’s death. By noon, many believe the problem to have been “Pressure”. This naturally gives rise, an hour later, to the rumour that he has killed himself:

“All the people who had tried to make money and had not been able to do it, said, There you were! You no sooner began to devote yourself to the pursuit of wealth than you got Pressure. The idle people improved the occasion in a similar manner. See, said they, what you brought yourself to by work, work, work! You persisted in working, you overdid it. Pressure came on, and you were done for!”

Soon after this, people begin to worry about Mr. Merdle’s wealth. Perhaps it is not as vast as had been supposed, or it is difficult to realise. And then the attitude towards the heretofore “greatest man of the age” begins to change. It is said:

“He had sprung from nothing, by no natural growth or process that any one could account for; he had been, after all, a low, ignorant fellow; he had been a down-looking man, and no one had ever been able to catch his eye; he had been taken up by all sorts of people in quite an unaccountable manner; he had never had any money of his own, his ventures had been utterly reckless, and his expenditure had been most enormous.”

And as the day goes on, the hatred for Mr. Merdle increases, and it is said that:

“every servile worshipper of riches who had helped to set him on his pedestal, would have done better to worship the Devil point-blank … For by that time it was known that the late Mr Merdle’s complaint had been simply Forgery and Robbery …he, the shining wonder, the new constellation to be followed by the wise men bringing gifts, until it stopped over a certain carrion at the bottom of a bath and disappeared—was simply the greatest Forger and the greatest Thief that ever cheated the gallows.”

We now move to the dinner-party Mr. Merdle mentioned in the previous chapter. All the usual important people are there, including Bar, Bishop and Barnacle. It is at the Physician’s house, and the narrator wryly comments that the admiring:

“brilliant ladies about London … who would have been shocked to find themselves so close to him if they could have known on what sights those thoughtful eyes of his had rested within an hour or two, and near to whose beds, and under what roofs, his composed figure had stood.”

Because people know that the Physician sees them in all their different states and conditions, they tend to behave more openly and naturally at his parties. Mr. Merdle is missed, but not overmuch:

“Mr Merdle’s default left a Banquo’s chair at the table; but, if he had been there, he would have merely made the difference of Banquo in it, and consequently he was no loss.”

Bar begins flirting with Mrs. Merdle, in an attempt to find out which title has been offered to Mr. Merdle, but neither discovers anything through the conversation:

“’I should like it to be true; why should I deny that to you? You would know better, if I did!’

‘Just so,’ said Physician.

‘But whether it is all true, or partly true, or entirely false, I am wholly unable to say. It is a most provoking situation, a most absurd situation; but you know Mr Merdle, and are not surprised.’”

Having said which, Mrs. Merdle is handed into her carriage, and leaves. The other guests soon follow her example, and Physician settles down to read a book. And we are about to find out exactly what this attractive man, “who is admitted to some of us every day with our wigs and paint off”, who gives parties where everyone enjoys being a little more true to themselves than usual, will be faced with tonight.

It is almost midnight, when the Physician hears someone at the door. Answering it himself, his servants having retired to bed, he is surprised to discover a man from the warm baths (public baths) waiting “much agitated and out of breath”. The man asks him to accompany him, handing him a scrap of paper with the Physician’s name and address on. Recognising the writing, Physician hurries, and asks everyone to stand back when they arrive at the warm baths.

First public wash house in England - photo of it from 1914

“There was a bath in that corner, from which the water had been hastily drained off. Lying in it, as in a grave or sarcophagus, with a hurried drapery of sheet and blanket thrown across it, was the body of a heavily-made man, with an obtuse head, and coarse, mean, common features … The white marble at the bottom of the bath was veined with a dreadful red. On the ledge at the side, were an empty laudanum-bottle and a tortoise-shell handled penknife—soiled, but not with ink.”

The man’s throat has been cut, and the Physician sees among the man’s neat belonging on the table, the edge of a paper which is intended for his eyes. Those in charge of the warm baths do what is necessary, without any fuss. But the Physician, who has seen humanity in all its dreadful states, still has to sit down outside for a while, “feeling sick and faint”.

He decides to call at Bar’s house, seeing a light still on in the window. Bar is still at work despite the late hour, and is astonished to see his friend on the doorstep, and asks:

“‘What’s the matter?’

‘You asked me once what Merdle’s complaint was.’

‘Extraordinary answer! I know I did.’

‘I told you I had not found out.’

‘Yes. I know you did.’

‘I have found it out.’”

And now Bar knows too, as he can see the truth in Physician’s shocked face. They go together to break the news to Mrs. Merdle. When they are inside:

“The Chief Butler … approached the window with dignity; looking on at Physician’s news exactly as he had looked on at the dinners in that very room.

‘Mr Merdle is dead.’

‘I should wish,’ said the Chief Butler, ‘to give a month’s notice.’

‘Mr Merdle has destroyed himself.’”

adds the Physician, trying to provoke some kind of reaction, but even this news does not disturb the Chief Butler’s aplomb. He merely states with his dignified manner intact:

“I should wish to leave immediately … Sir, Mr Merdle never was the gentleman, and no ungentlemanly act on Mr Merdle’s part would surprise me.”

Mrs. Merdle is reported by Physician to be bearing the part of the news she has been told well enough. As Bar and Physician make their way back to their respective homes, the narrator comments:

“if all those hundreds and thousands of beggared people who were yet asleep could only know, as they two spoke, the ruin that impended over them, what a fearful cry against one miserable soul would go up to Heaven!”

The news gets round the next day like wildfire, and there are many strange and wonderful rumours as to what had caused Mr. Merdle’s death. By noon, many believe the problem to have been “Pressure”. This naturally gives rise, an hour later, to the rumour that he has killed himself:

“All the people who had tried to make money and had not been able to do it, said, There you were! You no sooner began to devote yourself to the pursuit of wealth than you got Pressure. The idle people improved the occasion in a similar manner. See, said they, what you brought yourself to by work, work, work! You persisted in working, you overdid it. Pressure came on, and you were done for!”

Soon after this, people begin to worry about Mr. Merdle’s wealth. Perhaps it is not as vast as had been supposed, or it is difficult to realise. And then the attitude towards the heretofore “greatest man of the age” begins to change. It is said:

“He had sprung from nothing, by no natural growth or process that any one could account for; he had been, after all, a low, ignorant fellow; he had been a down-looking man, and no one had ever been able to catch his eye; he had been taken up by all sorts of people in quite an unaccountable manner; he had never had any money of his own, his ventures had been utterly reckless, and his expenditure had been most enormous.”

And as the day goes on, the hatred for Mr. Merdle increases, and it is said that:

“every servile worshipper of riches who had helped to set him on his pedestal, would have done better to worship the Devil point-blank … For by that time it was known that the late Mr Merdle’s complaint had been simply Forgery and Robbery …he, the shining wonder, the new constellation to be followed by the wise men bringing gifts, until it stopped over a certain carrion at the bottom of a bath and disappeared—was simply the greatest Forger and the greatest Thief that ever cheated the gallows.”

message 36:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 17, 2020 04:54AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Wow! What a chapter! And so cleverly written, so that we are not sure by the description of the body, who it is, until the brilliant “tell” of the tortoiseshell knife, "soiled, but not with ink"!

Mr. Merdle’s big head, and physical type have not been described until now, and just as I didn't imagine Edmund Sparkler as Charles Dickens described in the previous chapter, I never imagined Mr. Merdle as so coarse, with: “ an obtuse head, and coarse mean, common features”, and his figure being “clammy to touch”.

It is such an undignified death: sensational and sordid. We see him not as an icon of wealth, after all, but a man who lies beside “an empty laudanum-bottle and a tortoise-shell handled penknife … Separation of jugular vein—death rapid.”

I'll pick out one reference, and put it under spoilers just in case any one does not know the play Macbeth. “Banquo’s Chair” refers to the character of Banquo from William Shakespeare’s play. (view spoiler)

Mr. Merdle’s big head, and physical type have not been described until now, and just as I didn't imagine Edmund Sparkler as Charles Dickens described in the previous chapter, I never imagined Mr. Merdle as so coarse, with: “ an obtuse head, and coarse mean, common features”, and his figure being “clammy to touch”.

It is such an undignified death: sensational and sordid. We see him not as an icon of wealth, after all, but a man who lies beside “an empty laudanum-bottle and a tortoise-shell handled penknife … Separation of jugular vein—death rapid.”

I'll pick out one reference, and put it under spoilers just in case any one does not know the play Macbeth. “Banquo’s Chair” refers to the character of Banquo from William Shakespeare’s play. (view spoiler)

message 37:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 17, 2020 04:59AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

And a little more …

about John Sadleir:

At last I can share the end of the story, about the man in real life, John Sadleir, who Mr. Merdle was based on:

John Sadleir in c.1856 - exactly in the middle of the serialisation of Little Dorrit (1855-1857)

I’d said he was an Irish financier, member of Parliament and Junior Lord of the Treasury, but not how shady his business practises were—or how his life ended!

In 1856 John Sadleir was convicted of fraudulently overselling £150,000 of shares in the Royal Swedish Railway. He had overdrawn £288,000 from a Tipperary bank, and they were now insolvent. He represented some assets at £100,000 when in fact they were £30,000. He spent rents of properties he held in receivership and money entrusted to him as a solicitor. In the end, he attempted to raise money to cover his enormous debts by means of a forged deed. Altogether, he had disposed of more than £1.5 million, mainly in disastrous speculations.

When John Sadleir realised that he could not hide his fraudulent activities any longer, he went to an area of Hampstead Heath near Jack Straw’s Tavern, on a cold, February night, armed with prussic acid and a case of razors. Unlike Mr. Merdle though, he did not need to slit his throat, as the poison was to kill him. The next morning he was found dead, lying stiff and cold on the Heath.

The inquest into John Sadleir’s death went four sessions before a verdict was reached. It was found that he had left suicide notes full of guilt and remorse about his ruin of others:

“I cannot live—I have ruined too many—I could not live and see their agony—I have committed diabolical crimes unknown to any human being. They will now appear, bringing my family and others to distress—causing to all shame and grief that they should have ever known me.

I blame no one, but attribute all to my own infamous villainy. I could go through any torture as a punishment for my crimes, No torture could be too much for such crimes, but I cannot live to see the tortures I inflict upon others.”

His friends at first hid the notes, as they hoped for a verdict of temporary insanity. However, the notes ultimately convinced the coroner’s jury that John Sadleir was sane, precisely because he had realised the real harm he had done to others.

Today we may view this as harsh, or lacking in compassion, but the Victorians were satisfied. The “Annual Register” said that John Sadleir was:

“indeed a swindler on the very grandest scale, and kept up the game to the last: when his last game was played and dejection was inevitable, he committed suicide under circumstances of the utmost deliberation.”

The story doesn’t even end there! His elder brother James Sadleir, who was also an MP, was found to be deeply implicated in the fraud, having conspired with John. A few months later James Sadleir was expelled from the House of Commons. He fled to the Continent, settling in Zurich and then Geneva. He was murdered there in 1881, while being robbed of his gold watch.

John Sadleir himself was buried in an unmarked grave in Highgate Cemetery.

about John Sadleir:

At last I can share the end of the story, about the man in real life, John Sadleir, who Mr. Merdle was based on:

John Sadleir in c.1856 - exactly in the middle of the serialisation of Little Dorrit (1855-1857)

I’d said he was an Irish financier, member of Parliament and Junior Lord of the Treasury, but not how shady his business practises were—or how his life ended!

In 1856 John Sadleir was convicted of fraudulently overselling £150,000 of shares in the Royal Swedish Railway. He had overdrawn £288,000 from a Tipperary bank, and they were now insolvent. He represented some assets at £100,000 when in fact they were £30,000. He spent rents of properties he held in receivership and money entrusted to him as a solicitor. In the end, he attempted to raise money to cover his enormous debts by means of a forged deed. Altogether, he had disposed of more than £1.5 million, mainly in disastrous speculations.

When John Sadleir realised that he could not hide his fraudulent activities any longer, he went to an area of Hampstead Heath near Jack Straw’s Tavern, on a cold, February night, armed with prussic acid and a case of razors. Unlike Mr. Merdle though, he did not need to slit his throat, as the poison was to kill him. The next morning he was found dead, lying stiff and cold on the Heath.

The inquest into John Sadleir’s death went four sessions before a verdict was reached. It was found that he had left suicide notes full of guilt and remorse about his ruin of others:

“I cannot live—I have ruined too many—I could not live and see their agony—I have committed diabolical crimes unknown to any human being. They will now appear, bringing my family and others to distress—causing to all shame and grief that they should have ever known me.

I blame no one, but attribute all to my own infamous villainy. I could go through any torture as a punishment for my crimes, No torture could be too much for such crimes, but I cannot live to see the tortures I inflict upon others.”

His friends at first hid the notes, as they hoped for a verdict of temporary insanity. However, the notes ultimately convinced the coroner’s jury that John Sadleir was sane, precisely because he had realised the real harm he had done to others.

Today we may view this as harsh, or lacking in compassion, but the Victorians were satisfied. The “Annual Register” said that John Sadleir was:

“indeed a swindler on the very grandest scale, and kept up the game to the last: when his last game was played and dejection was inevitable, he committed suicide under circumstances of the utmost deliberation.”

The story doesn’t even end there! His elder brother James Sadleir, who was also an MP, was found to be deeply implicated in the fraud, having conspired with John. A few months later James Sadleir was expelled from the House of Commons. He fled to the Continent, settling in Zurich and then Geneva. He was murdered there in 1881, while being robbed of his gold watch.

John Sadleir himself was buried in an unmarked grave in Highgate Cemetery.

message 38:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 17, 2020 05:04AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

John Sadleir and Mr. Merdle:

Mr. Merdle is not the only character in Victorian literature to be based on John Sadleir. Anthony Trollope also wrote one, but I’ll put it under spoilers for anyone who hasn’t read the novel this character is in. If you have, you will be able to recognise it by now! (view spoiler)

In his introduction to Little Dorrit, Charles Dickens connects the novel’s Mr. Merdle with “a certain Irish Bank”. There have also been little clues about his forthcoming suicide, the most overt being the “black traces on his lips where they met, as if a little train of gunpowder had been fired there” His suicidal tendencies are hinted at by the hand-to-head gesture he makes, which is modelled on John Sadleir’s last days.

The third big clue, (which several here did pick up!) is when he tucks his hands inside his coat cuffs, trying to withdraw into his clothes, and sometimes clasping his wrists as though taking himself into custody for a crime only he knows he has committed—yet. The readers of the time will have been well aware of exactly who Mr. Merdle was based on, and it probably added an extra exciting frisson :)

We are not told of Mr. Merdle’s origins, although as we noticed, the butler correctly identified that he was not a “gentleman”. Yet he was admired—even idolised—by all of society, because of his immense wealth, and now we know that he perpetrated fraud on the grandest scale. Charles Dickens had no need to spell it out, by writing an inquest, because we readers have suspected from the very beginning that Mr. Merdle felt guilty of something, and condemned himself. He was so retiring; almost afraid of Society.

He also suffered from some unknown “complaint”, and an entire chapter was devoted to this. Mr. Merdle’s Physician told us then that it was, “a deep-seated recondite complaint which does not ease from day to day”. And in this chapter, he tells his friend Bar, that he has at last discovered what this “complaint” is.

Mr. Merdle is not the only character in Victorian literature to be based on John Sadleir. Anthony Trollope also wrote one, but I’ll put it under spoilers for anyone who hasn’t read the novel this character is in. If you have, you will be able to recognise it by now! (view spoiler)

In his introduction to Little Dorrit, Charles Dickens connects the novel’s Mr. Merdle with “a certain Irish Bank”. There have also been little clues about his forthcoming suicide, the most overt being the “black traces on his lips where they met, as if a little train of gunpowder had been fired there” His suicidal tendencies are hinted at by the hand-to-head gesture he makes, which is modelled on John Sadleir’s last days.

The third big clue, (which several here did pick up!) is when he tucks his hands inside his coat cuffs, trying to withdraw into his clothes, and sometimes clasping his wrists as though taking himself into custody for a crime only he knows he has committed—yet. The readers of the time will have been well aware of exactly who Mr. Merdle was based on, and it probably added an extra exciting frisson :)

We are not told of Mr. Merdle’s origins, although as we noticed, the butler correctly identified that he was not a “gentleman”. Yet he was admired—even idolised—by all of society, because of his immense wealth, and now we know that he perpetrated fraud on the grandest scale. Charles Dickens had no need to spell it out, by writing an inquest, because we readers have suspected from the very beginning that Mr. Merdle felt guilty of something, and condemned himself. He was so retiring; almost afraid of Society.

He also suffered from some unknown “complaint”, and an entire chapter was devoted to this. Mr. Merdle’s Physician told us then that it was, “a deep-seated recondite complaint which does not ease from day to day”. And in this chapter, he tells his friend Bar, that he has at last discovered what this “complaint” is.

message 39:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 17, 2020 03:15AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

And yet more …!

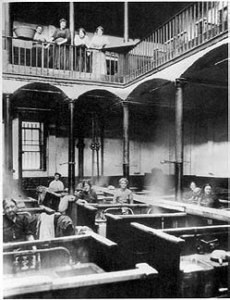

About the Warm Baths:

“‘I come from the warm-baths, sir, round in the neighbouring street.”

The image I included in the text is of the first warm baths in Liverpool, as no illustrator seems to have been brave enough to illustrate this chapter! Here's another one of a similar wash house, this time in Hornsey (South London). The photograph is again taken later, of course, in 1901.

The Victorians had very little access to clean water, so for many it was an uphill struggle to keep themselves clean and healthy. Then in 1846 the “Baths and Wash-houses Act” was passed. This was the first legislation to empower British local authorities to fund the building of public baths and wash house, and from then on they proliferated all over the country. By 1865, numerous large towns had public baths and they were popular wherever they were established.

Before the Act - and the main reason why it had been passed - the first ever public baths and wash house in Britain had been established in Liverpool, and were a great success. St. George’s Pier Head salt-water baths were opened in 1828 by the Corporation of Liverpool, with the first known warm fresh-water public wash house being opened in May 1842 on Frederick Street (I included a photo of this for the chapter summary). This was partly in response to a cholera epidemic in 1832.

The first ever London public baths was opened in 1845, in Glasshouse Yard, Docklands. After the passing of the “Baths and Wash-houses Act” a much grander one was opened by Prince Albert (the husband of Queen Victoria) at Goulston Square, Whitechapel, in 1847. This, I believe, must be the location of Mr. Merdle’s suicide.

We know that the Merdles lived just off Cavendish Square, and that the Physician was at Bar’s house, when he learnt of Mr. Merdle’s suicide. We assume these friends lived close to one another, and the distance between Cavendish Square and Goulston Square is 4-5 miles: a half hour walk.

The warm baths building was demolished in 1989, and a Women’s Library has been built on the site, but that is not the main problem. Have you noted the dates?

Charles Dickens wrote Little Dorrit between 1855 and 1857. He began it 9 years after the Act which made public baths so popular … but he set the novel in 1827.

Therefore, at the time of Little Dorrit, there were no public baths in London - or anywhere else here! The Romans had built London baths, but they didn’t last after they left, because it was felt they spread the plague - and encouraged licentiousness as they were mixed. The first ones were to open a year later; those referred to in Liverpool.

Yes, Charles Dickens seems to have made a mistake! I looked to see if John Sutherland had written about it as one of his literary conundrums, as he delights in finding out such inconsistencies in Victorian literature, but he doesn’t seem to have. The dates I quoted are easy enough to verify online, or in the bible about London, The London Encyclopaedia.

About the Warm Baths:

“‘I come from the warm-baths, sir, round in the neighbouring street.”

The image I included in the text is of the first warm baths in Liverpool, as no illustrator seems to have been brave enough to illustrate this chapter! Here's another one of a similar wash house, this time in Hornsey (South London). The photograph is again taken later, of course, in 1901.

The Victorians had very little access to clean water, so for many it was an uphill struggle to keep themselves clean and healthy. Then in 1846 the “Baths and Wash-houses Act” was passed. This was the first legislation to empower British local authorities to fund the building of public baths and wash house, and from then on they proliferated all over the country. By 1865, numerous large towns had public baths and they were popular wherever they were established.

Before the Act - and the main reason why it had been passed - the first ever public baths and wash house in Britain had been established in Liverpool, and were a great success. St. George’s Pier Head salt-water baths were opened in 1828 by the Corporation of Liverpool, with the first known warm fresh-water public wash house being opened in May 1842 on Frederick Street (I included a photo of this for the chapter summary). This was partly in response to a cholera epidemic in 1832.

The first ever London public baths was opened in 1845, in Glasshouse Yard, Docklands. After the passing of the “Baths and Wash-houses Act” a much grander one was opened by Prince Albert (the husband of Queen Victoria) at Goulston Square, Whitechapel, in 1847. This, I believe, must be the location of Mr. Merdle’s suicide.

We know that the Merdles lived just off Cavendish Square, and that the Physician was at Bar’s house, when he learnt of Mr. Merdle’s suicide. We assume these friends lived close to one another, and the distance between Cavendish Square and Goulston Square is 4-5 miles: a half hour walk.

The warm baths building was demolished in 1989, and a Women’s Library has been built on the site, but that is not the main problem. Have you noted the dates?

Charles Dickens wrote Little Dorrit between 1855 and 1857. He began it 9 years after the Act which made public baths so popular … but he set the novel in 1827.

Therefore, at the time of Little Dorrit, there were no public baths in London - or anywhere else here! The Romans had built London baths, but they didn’t last after they left, because it was felt they spread the plague - and encouraged licentiousness as they were mixed. The first ones were to open a year later; those referred to in Liverpool.

Yes, Charles Dickens seems to have made a mistake! I looked to see if John Sutherland had written about it as one of his literary conundrums, as he delights in finding out such inconsistencies in Victorian literature, but he doesn’t seem to have. The dates I quoted are easy enough to verify online, or in the bible about London, The London Encyclopaedia.

A short but very dramatic chapter! I too did not suspect Mr. Merdle's physical appearance, and was thrown for a loop intill the pen knife was described. I wonder too, since the chief buttler could tell he was not a gentleman, perhaps he did see through Mr. Dorrit.

A short but very dramatic chapter! I too did not suspect Mr. Merdle's physical appearance, and was thrown for a loop intill the pen knife was described. I wonder too, since the chief buttler could tell he was not a gentleman, perhaps he did see through Mr. Dorrit.

This chapter is a stunner even when you know what's coming. Not getting ink on the penknife is such a great touch.

This chapter is a stunner even when you know what's coming. Not getting ink on the penknife is such a great touch.In the recent BBC series Anton Lesser portrays Mr Merdle. He's not overweight but he conveys the world-weary detachment of Merdle very well, I think.

https://images.app.goo.gl/oV6p6smDfNR...

Here he is in his Little Dorrit clothes. Many fans recognize him from Game of Thrones.

Here he is in his Little Dorrit clothes. Many fans recognize him from Game of Thrones.https://images.app.goo.gl/pw7WnQwgPHN...

It's very interesting that Mr. Merdle's character and crimes were based on a real person and that the readers at the time would have known exactly on whom Merdle was based.

It's very interesting that Mr. Merdle's character and crimes were based on a real person and that the readers at the time would have known exactly on whom Merdle was based. I enjoyed the comic relief provided by Bar.

message 44:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 17, 2020 07:33AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

I agree Mark, Anton Lesser plays every part he is in exceptionally well :) I've seen him as Thomas More in Wolf Hall, Fagin in "Dickensian" and literally dozens of others, from the upright, thoughtful Chief Superintendent Bright in "Endeavour", to a cheeky cockney villain in "Inspector Morse"! He's one of our best Shakespearean actors, and a member of the RSC. He won an award for his recording of Great Expectations, and I think his understated performance in Little Dorrit was superb. It's such a difficult, enigmatic part to play. I posted a still from the miniseries in one of my summaries where he was accompanied by the "Bosom", on which he displayed all his riches.

I do prefer Eleanor Bron in the role of Mrs. Merdle - as I do several members of the earlier cast. I'm watching it now, but am aware just how many characters are missed out: Rigaud, Cavalletto, Harriet/Tattycoram, Mrs. Meagles ...

On the other hand, the attention to detail and locations, and the grand, noisy street scenes are superb. Plenty of TV films "cheat" doing a lot of close-ups :(

I do prefer Eleanor Bron in the role of Mrs. Merdle - as I do several members of the earlier cast. I'm watching it now, but am aware just how many characters are missed out: Rigaud, Cavalletto, Harriet/Tattycoram, Mrs. Meagles ...

On the other hand, the attention to detail and locations, and the grand, noisy street scenes are superb. Plenty of TV films "cheat" doing a lot of close-ups :(

This is a stunning chapter, even though we clearly see what is coming, as Dickens has provided us with hints all along the way. You expect to despise Merdle, but you end up feeling rather sorry for him. He has ruined his life, along with the lives of so many others, on the pursuit of pleasure and money, but the reality is that the money was hollow and there was very little pleasure he took from anything he acquired. Also seems sad that his last act was to visit people who should have cared for him, but obviously did not, and to seek from them the instrument of his death.

This is a stunning chapter, even though we clearly see what is coming, as Dickens has provided us with hints all along the way. You expect to despise Merdle, but you end up feeling rather sorry for him. He has ruined his life, along with the lives of so many others, on the pursuit of pleasure and money, but the reality is that the money was hollow and there was very little pleasure he took from anything he acquired. Also seems sad that his last act was to visit people who should have cared for him, but obviously did not, and to seek from them the instrument of his death. Lesser is a marvelous choice to portray him--one of my favorite actors and so versatile.