The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

The Holly-Tree

The Holly-Tree Inn

>

The Holly-Tree Inn Part Two

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

I didn't mind this part that much, perhaps because it was shorter (the first branch took up half of the book) and I don't mind children. I do agree though, it seems to get less christmassy by the minute.

Gretna Green was a place where you could get married when underage, and without permission from your parents. At least originally you would be married by the blacksmith there. It's kind of like running off to Vegas, but then with the marriage being official everywhere (like, if you marry in Vegas you're not legally married here in The Netherlands, but if you'd marry in Gretna Green you would be). Anyway, everywhere else you'd have to be at least 21 and I believe even then need the permission of the bride's father or guardian, but you'd certainly need that permission before turning 21. Most people in the time married well before that age, so running off to Gretna Green was quite a thing when daddy didn't approve of the groom-to-be. Or if you were 8-year-olds apparently.

Gretna Green was a place where you could get married when underage, and without permission from your parents. At least originally you would be married by the blacksmith there. It's kind of like running off to Vegas, but then with the marriage being official everywhere (like, if you marry in Vegas you're not legally married here in The Netherlands, but if you'd marry in Gretna Green you would be). Anyway, everywhere else you'd have to be at least 21 and I believe even then need the permission of the bride's father or guardian, but you'd certainly need that permission before turning 21. Most people in the time married well before that age, so running off to Gretna Green was quite a thing when daddy didn't approve of the groom-to-be. Or if you were 8-year-olds apparently.

I really did enjoy this second part, finding it very sweet and enjoyable, but then I love children. But I admit I love mine and my grandchildren best, of course. I did love this little story within a story, though. As for Gretna Green, another note is that it is just across the northern border in Scotland. I read many books where it was in the plot, especially romances, and when my husband and I visited the UK we visited there. It is mostly for tourists now and we had a mock wedding "over the anvil" for a couple in our group who were celebrating an anniversary.

I really did enjoy this second part, finding it very sweet and enjoyable, but then I love children. But I admit I love mine and my grandchildren best, of course. I did love this little story within a story, though. As for Gretna Green, another note is that it is just across the northern border in Scotland. I read many books where it was in the plot, especially romances, and when my husband and I visited the UK we visited there. It is mostly for tourists now and we had a mock wedding "over the anvil" for a couple in our group who were celebrating an anniversary.

Well you are all invited to bring your children and grandchildren when you come to visit, but please try to keep an eye on them, I only have so many. :-) Tonight should have been our family Christmas party, a night to dread. It isn't just the close family, my daughter, her husband, our two grandchildren, my son and his girlfriend, it's everybody who's related to us at all from anywhere. This is the first year of our married lives we haven't had this dreadful party on the Saturday before Christmas. Why is it dreadful? you are dying to know. Because it is family, so they aren't careful about what their kids are doing. It's like they open the door, the kids come running in, and that's the last time the parents notice them until they finally leave sometime late in the evening. You probably noticed from the pictures that I don't exactly have a child friendly home, especially not at Christmas. Not that children can't have fun here. Our grandkids were just here for cookie baking, we played Christmas games, watched Christmas movies and sang Christmas songs. But they know where things are, what to touch and what to stay away from, I can yell at them, I can even still yell at their mother.

But at the family party people who haven't seen each other since the last family party are now all together and happy to see each other. They eat and drink wine and talk and talk and talk. My husband keeps the all the food trays on the table filled and makes punch, and I chase the kids around. There was the year they decided it would be a good idea to have a food fight and when I walked into the dining room I found kids throwing apple and watermelon slices at each other. I wasn't happy. Then there was the chase the dog screaming year I already mentioned. And the year they were shooting grapes into the Santa tree with rubber bands. And their parents aren't even in the same room. Usually when other people bring their children they keep an eye on them, it's the family I have to worry about. But this year I don't have to worry about any houses ending up with pieces broken off of them, this will be the first year my houses have made it through a season without something getting broken. It's kind of sad. Figure that out.

But at the family party people who haven't seen each other since the last family party are now all together and happy to see each other. They eat and drink wine and talk and talk and talk. My husband keeps the all the food trays on the table filled and makes punch, and I chase the kids around. There was the year they decided it would be a good idea to have a food fight and when I walked into the dining room I found kids throwing apple and watermelon slices at each other. I wasn't happy. Then there was the chase the dog screaming year I already mentioned. And the year they were shooting grapes into the Santa tree with rubber bands. And their parents aren't even in the same room. Usually when other people bring their children they keep an eye on them, it's the family I have to worry about. But this year I don't have to worry about any houses ending up with pieces broken off of them, this will be the first year my houses have made it through a season without something getting broken. It's kind of sad. Figure that out.

I enjoyed the 2nd branch better than the first. Having spent a lot of time in the children's' room at my library, I can say with confidence that I like most children -- it's their parents whom I often dislike. And I liked the two in our story. Yes - Harry seemed a bit too precocious sometimes, but my philosophy has always been that the parent has 18 years to get their child to be an independent, responsible adult. Walmers seems to be doing a pretty good job in that department. Yes, Harry can be a bit too self-assured, but perhaps that's a result of the class system more than his character. At any rate, he treats people pretty well even for a bossy 8 year old.

I enjoyed the 2nd branch better than the first. Having spent a lot of time in the children's' room at my library, I can say with confidence that I like most children -- it's their parents whom I often dislike. And I liked the two in our story. Yes - Harry seemed a bit too precocious sometimes, but my philosophy has always been that the parent has 18 years to get their child to be an independent, responsible adult. Walmers seems to be doing a pretty good job in that department. Yes, Harry can be a bit too self-assured, but perhaps that's a result of the class system more than his character. At any rate, he treats people pretty well even for a bossy 8 year old. Okay - this wasn't a great piece of literature, but it was sweet and had an actual story, unlike the list of inns we were treated to in the first branch. I would have so much preferred that Dickens (?) choose one good inn anecdote for the first branch, rather than writing a paragraph or two on twenty inns.

And, like Kim, I wonder why on Earth they didn't have any of these stories set at Christmas? Our narrator being stuck there and hearing the stories at Christmas does me no good, unless they, from time to time, insert a comment about him refilling his eggnog, or taking a break from the tale to sing a carol or two around the hearth. I'm putting a lot of pressure on our third branch to bring some holiday cheer into this "Christmas story". And I hope the authors will do SOMETHING to bring some cohesion to our tale.

I've been watching at least one Christmas movie a day since Thanksgiving (no Hallmark allowed) and have quickly discovered that there are Christmas films (It's a Wonderful Life, A Christmas Carol, etc.) and there are movies that take place at Christmas, but really have very little to do with the holiday (Love Finds Andy Hardy, The Long Kiss Goodnight). So far, the Holly-Tree is one of those that just takes place at Christmas.

As to your last question, Mary Lou, I have made a rather stunning and sobering discovery the other day, which I am hereby going to share with you.

Finding the story rather short with regard to the number of writers that are involved and wanting to know who wrote what, I did some research on the web and also landed on the website of the Gutenberg project. And it was there that I discovered that the story is actually much longer, that there are ten or twelve individual chapters - and that my Delphi e-reader editon (as well as most other editions) only gave the bits written by Dickens, namely those three chapters I had in the reading schedule. At that time, I did not know that we were not dealing with the complete text of the Holly-Tree Inn and already wondered how all those writers condensed their ideas into such a relatively short text.

The Gutenberg Project offers the entire original text - it even has a longer poem in it - and, what's more, it also says who was responsible for every individual chapter. As I said, all the chapters we are dealing with here were written by Dickens.

So, I humbly ask your pardons for offering you only a partial version of this collaborative piece of writing - but it was not until quite recently that I noticed the fragmentary character of what we have got here.

Finding the story rather short with regard to the number of writers that are involved and wanting to know who wrote what, I did some research on the web and also landed on the website of the Gutenberg project. And it was there that I discovered that the story is actually much longer, that there are ten or twelve individual chapters - and that my Delphi e-reader editon (as well as most other editions) only gave the bits written by Dickens, namely those three chapters I had in the reading schedule. At that time, I did not know that we were not dealing with the complete text of the Holly-Tree Inn and already wondered how all those writers condensed their ideas into such a relatively short text.

The Gutenberg Project offers the entire original text - it even has a longer poem in it - and, what's more, it also says who was responsible for every individual chapter. As I said, all the chapters we are dealing with here were written by Dickens.

So, I humbly ask your pardons for offering you only a partial version of this collaborative piece of writing - but it was not until quite recently that I noticed the fragmentary character of what we have got here.

I have not yet started reading the third branch, and so I can't promise that it will be more Christmassy, but I hope it will.

As it happens, my family and I have also watched some Christmas movies over the past few weeks and we noticed that the label Christmas movie sticks more easily on some of them than on others. In choosing our Christmas fare, my wife made quite a point of the fact that Die Hard is not really a Christmas movie at all, a detail that until then had quite evaded my notion.

I must say that I liked the first branch better because of that crazy - here we go, Kim - concatenation of ideas and memories the narrator went throug, espcially with regard to the stories of the murderous innkeepers. This is more in accordance with my sense of humour than the story of the two children, which was way too sweet for me. However, I could feel with Boots and his misgivings when he tried to delay the two children at the inn until their parents would arrive. He must have felt like a mean traitor, indeed.

As it happens, my family and I have also watched some Christmas movies over the past few weeks and we noticed that the label Christmas movie sticks more easily on some of them than on others. In choosing our Christmas fare, my wife made quite a point of the fact that Die Hard is not really a Christmas movie at all, a detail that until then had quite evaded my notion.

I must say that I liked the first branch better because of that crazy - here we go, Kim - concatenation of ideas and memories the narrator went throug, espcially with regard to the stories of the murderous innkeepers. This is more in accordance with my sense of humour than the story of the two children, which was way too sweet for me. However, I could feel with Boots and his misgivings when he tried to delay the two children at the inn until their parents would arrive. He must have felt like a mean traitor, indeed.

Tristram wrote: "I have made a rather stunning and sobering discovery the other day, which I am hereby going to share with you..."

Tristram wrote: "I have made a rather stunning and sobering discovery the other day, which I am hereby going to share with you..."Well, this explains a lot. Thanks for sharing this info. As it turns out, this season has been surprisingly busy for me (what with all those Christmas movies ;-) ) so just reading the Dickens branches worked well for me, time-wise. I would like to read the other authors' contributions, though. Maybe I'll have time when Christmas is just a memory and a lingering feeling of being bloated.

Tristram, you noted the murderous innkeepers and then the sweetness of the Boots branch. They really are about as far apart as two stories can be, aren't they?

I have The Holly Tree in different Christmas books and none of them have the other stories only Dickens. I just assumed they were lost somewhere along the way.

An Engagement

Second Branch

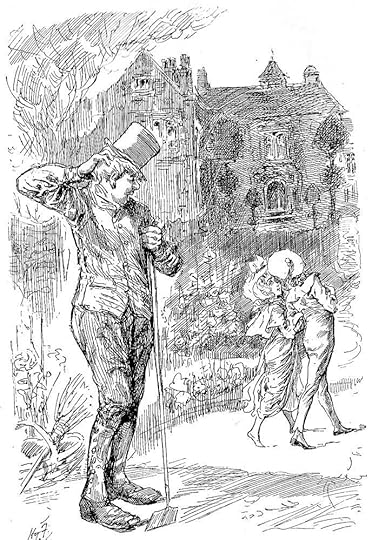

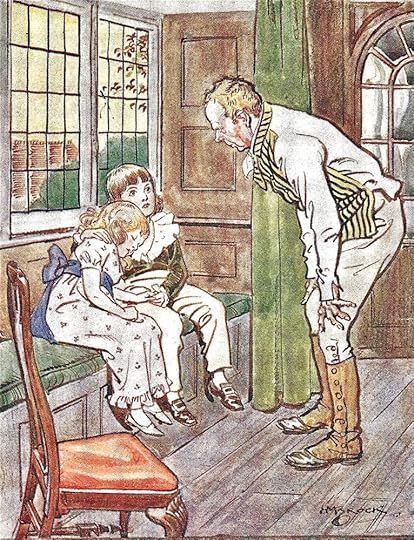

Harry Furniss

1910

Text Illustrated:

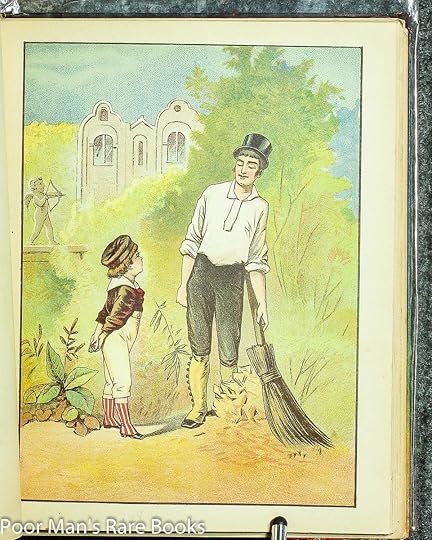

How did Boots happen to know all this? Why, through being under-gardener. Of course he couldn't be under-gardener, and he always about, in the summer-time, near the windows on the lawn, a-mowing, and sweeping, and weeding, and pruning, and this and that, without getting acquainted with the ways of the family. Even supposing Master Harry hadn't come to him one morning early, and said, "Cobbs, how should you spell Norah, if you was asked?" and then began cutting it in print all over the fence.

He couldn't say that he had taken particular notice of children before that; but really it was pretty to see them two mites a-going about the place together, deep in love. And the courage of the boy! Bless your soul, he'd have throwed off his little hat, and tucked up his little sleeves, and gone in at a lion, he would, if they had happened to meet one, and she had been frightened of him. One day he stops, along with her, where Boots was hoeing weeds in the gravel, and says, speaking up, "Cobbs," he says, "I like you." "Do you, sir? I'm proud to hear it." "Yes, I do, Cobbs. Why do I like you, do you think, Cobbs?" "Don't know, Master Harry, I am sure." "Because Norah likes you, Cobbs." "Indeed, sir? That's very gratifying." "Gratifying, Cobbs? It's better than millions of the brightest diamonds to be liked by Norah." "Certainly, sir." "Would you like another situation, Cobbs?" "Well, sir, I shouldn't object if it was a good 'un." "Then, Cobbs," says he, "you shall be our Head Gardener when we are married." And he tucks her, in her little sky-blue mantle, under his arm, and walks away.

Commentary:

Most of Dickens seasonal offerings in the weekly journals Household Words (1851-58) and All the Year Round (1859-1867), appeared in substantial "Extra Christmas" numbers, and The Holly-Tree Inn was no exception, being the multi-part or framed tale for Christmas 1855, the principal collaborator of the novella being the novelist and Dickens protegé Wilkie Collins, who provided the second story, "The Ostler." a print one.]

For this sixth seasonal offering, however, there were also three lesser contributors: William Howitt ("The Landlord"), Adelaide Anne Procter ("The Barmaid"), and Harriet Parr (aka "Holme Lee" — "The Poor Pensioner"). Dickens introduced The Holly-Tree Inn with "The Guest," developed the romantic plot of the runaway children in "The Boots" (the subject of Furniss's initial illustration), and concluded with "The Bill," the seventh and final part.

Furniss's handling of this moment of the narrative-within-the-narrative is much more impressionistic and dynamic — especially in terms of the garden backdrop — than that of Harry French forty years earlier. Whereas French realises the scene between the precocious Master Harry Walmers, Jr., and Cobbs, then the under-gardener to Harry's father in a Sixties manner, with modelling and realistic detail, Furniss's version is charged with energy, despite its paucity of detail, and includes both Norah and the Victorian mansion of the wealthy Walmers family.

Whereas French's gardener Cobbs (identified as such by the watering can) is both amused and fascinated with Harry's audacity, Furniss's gardener (identified by his leggings and hoe) seems utterly confounded as the young couple stroll blithely off right, already married in imagination and perhaps even plotting their elopement to Gretna Green. The building in the background is not the Yorkshire coaching inn from which the novella takes its name (in Dickens's mind based on The George and New Inn, Gretna Bridge, where the novelist stayed in 1838 while investigating the notorious Yorkshire schools for Nicholas Nickleby — April 1838 through October 1839 — which he epitomised in Squeers' Dotheboys Hall).Rather, this scene occurs earlier than the elopement.

One receives but a scant impression of the building behind Cobbs, the under-gardener at the Walmers' estate at Shooter's Hill in the French illustration, but Furniss provides a panoramic view of the south of England mansion, through the garden of which Norah and Harry are strolling animatedly — perhaps already planning their elopement when Harry visits his grandmother. In contrast to French and Furniss, E. A. Abbey in the Household Edition instead elected to realise a scene at the inn, after Norah and Harry have arrived, which is some months after Cobbs has left the estate of Mr. Harry Walmers, Senior, to become the boots at the Holly-Tree Inn, Yorkshire. Abbey shows a Cobbs transformed from under-gardener to the hostelry's general factotum (the "boots"), a role made famous by the celebrated comic figure of Sam Weller in Dickens's first novel, The Pickwick Papers. Abbey even gives Cobbs the same striped silk waistcoat worn by the ebullient Cockey in Hablot Knight Browne's illustrations, notably The First Appearance of Sam Weller (July 1836), whereas Furniss and French give us a more proletarian and agrarian Cobbs, not yet the teller of the tale-within-the-tale in The Holly-Tree.

Arrivals at The Holly Tree

Harry Furniss

1910

Text Illustrated:

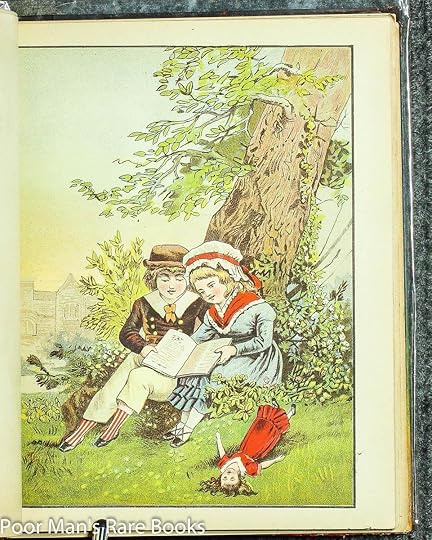

Sir, Boots was at this identical Holly-Tree Inn (having left it several times to better himself, but always come back through one thing or another), when, one summer afternoon, the coach drives up, and out of the coach gets them two children. The Guard says to our Governor, "I don't quite make out these little passengers, but the young gentleman's words was, that they was to be brought here." The young gentleman gets out; hands his lady out; gives the Guard something for himself; says to our Governor, "We're to stop here to-night, please. Sitting-room and two bedrooms will be required. Chops and cherry-pudding for two!" and tucks her in her little sky-blue mantle, under his arm, and walks into the house much bolder than Brass.

Commentary:

Furniss's handling of this moment of the narrative-within-the-narrative is much more impressionistic and dynamic — especially in terms of the coaching scene that forms the backdrop — than that of Harry French forty years earlier in the garden scene at Shooter's Hill. Whereas French realises the scene between the precocious Master Harry Walmers, Jr., and Cobbs, then the under-gardener to Harry's father in a Sixties manner, with modelling and realistic detail, Furniss's realisation of the arrival at the Holly Tree in Yorkshire is thoroughly comedic, with the well-dressed children handling The business of arranging accommodation with aplomb as the landlord ("Governor") rubs his hands in glee at the prospect of a substantial bill for the diminutive but obviously affluent travellers.

Whereas French's gardener Cobbs (identified as such by the watering can) is both amused and fascinated with Harry's audacity, Furniss's boots (the observer outside the frame of the picture) seems completely impressed with Master Harry's audacity in carrying out his plans for the elopement to Gretna Green. The scene has now shifted to the Yorkshire coaching inn from which the novella takes its name (in Dickens's mind based on The George and New Inn, Gretna Bridge, where the novelist stayed in 1838 while investigating the notorious Yorkshire schools for Nicholas Nickleby — April 1838 through October 1839 — which he epitomised in Squeers' Dotheboys Hall). However, all that we see in Furniss's drawing of the inn is the porch and the yard (complete with a pigeon roost) in the background, lightly sketched in so as to keep the eye well forward on the travellers and the landlord.

Furniss's characterisation of the landlord (dressed in the manner of the Regency, in contrast to Norah's and Harry's contemporary fashions) proves somewhat inaccurate as the reader, already having encountered this scene in the text before reaching the illustration, knows that the jolly-faced, benign Governor, far from acceding to Master Harry's plans, leaves immediately after the arrival to "quiet their friends' minds" and report the missing pair to the authorities in an effort to find their relatives. The charm of the illustration lies in Furniss's description as a miniature, fashionably dressed adult confidently negotiating with the landlord, recalling the less confident of David Copperfield when he was dealing with the friendly waiter on the road to London, a moment amusingly realised by Hablot Knight Browne in The friendly waiter and I (June 1849). For readers in 1910 an added charm of the plate, based on a pen-and-ink study, would have been the interplay of guard, driver, and ostler as they work to effect the change of horses at the old coaching inn, now very much a thing of the past in the railway era.

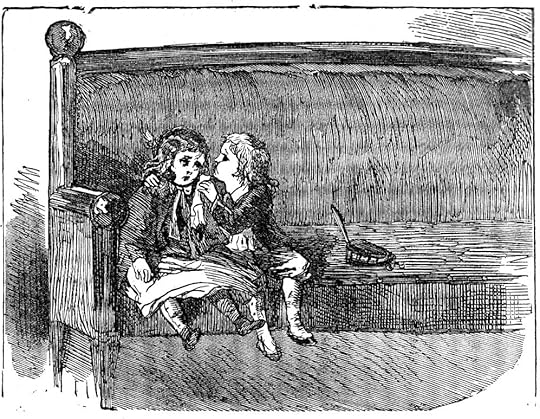

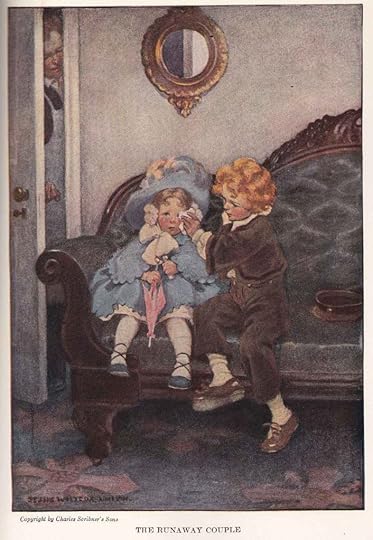

Mr. and Mrs. Harry Walmers, Jr.

Second Branch

Sol Eytinge

1867 Diamond Edition

Text Illustrated:

So Boots goes up-stairs to the Angel, and there he finds Master Harry on a e-normous sofa,— immense at any time, but looking like the Great Bed of Ware, compared with him, — a drying the eyes of Miss Norah with his pocket-hankecher. Their little legs was entirely off the ground, of course, and it really is not possible for Boots to express to me how small them children looked.

Commentary:

The 1855 "framed tale" for Christmas, with contributions by Dickens's staff-writers, the successor to The Seven Poor Travellers in the fifth Extra Christmas Number in Household Words, has seven parts, four not by Dickens himself. The much larger Christmas offering originally appeared as The Holly-Tree Inn without illustration on 15 December 1855. Perhaps because only Dickens's contributions have been widely reprinted, posterity has lost sight of the other tales in the sequence, although these were penned by some of the mid-nineteenth-century's more popular writers of journalistic short fiction: Part 2, "The Ostler," is by Wilkie Collins; Part 4, "The Landlord," by William Howitt; Part 5, "The Barmaid," by Adelaide Anne Proctor; and "The Poor Pensioner," by Harriet Parr (writing under the nom de plume "Holme Lee") — the last three of whom got their start as professional writers on the staff of Household Words. In contrast, Dickens's three pieces — "The Guest" (Part 1), "The Boots" (Part 3), and "The Bill") Part 7) have been reprinted under the heading "The Holly-Tree Inn: Three Branches" ever since 1867. For this sixth seasonal offering, however, there were three lesser pieces of varying quality which Dickens introduced with "The Guest," developed the romantic plot of the runaway children in "The Boots" (the subject of Furniss's first and second illustrations for the short story in 1910), and concluded with "The Bill," the seventh and final part in which the middle-class Londoner who is the original narrator learns of his error and returns home to be married instead of emigrating to America.

Although it conveys adequately Norah's distress at being away from home and suffering an exhausting coach trip, and Harry's solicitousness, Eytinge's slight wood-engraving gives the reader no sense of the story's physical setting, the Yorkshire Inn based on the well-known George and New Inn at Greta Bridge. The enormous couch might be anywhere.

Using the distnctive voice of Cobbs, the "Boots" (that is, the hotel employee who, like Sam Weller in The Pickwick Papers of 1836-37, cleans boots and is the general factotum for a coaching inn), Dickens's Traveller narrates the tale of the asexual attraction of two precocious children, Norah and Harry, who plan to elope to Gretna Green. The illustrator should try to capture the essential humour of the piece that Dickens would employ again in A Holiday Romance in Our Young Folks in 1867. Unfortunately, the pluck and dash of the precocious Harry is not in evidence in Eytinge's illustration.

When called upon by the snow-bound traveller for a tale, the loquacious Cobbs recalls when, as the under-gardener to Mr. Walmers at Shooter's Hill, about seven miles from London, he had watched young Master Harry and Norah play in the garden, — and then goes on to narrate how the trajectory of their romance led to their being guests at the Holly Tree Inn in Yorkshire. Without the four contributions of Dickens's collaborators, the piece was often reprinted as "Boots at The Holly-Tree Inn," the second of "The Holly-Tree: Three Branches." Cobbs's narrative as retailed by monologic traveller (a first-person narrative at one remove, so to speak, for Dickens's focal character of the frame remains in charge of "conducting" the story, although quoting Cobbs liberally) gives Dickens the opportunity to lapse into dialect and to offer a unique working-class perspective on the antics of the two charming, privileged children of the upper-middle class and their idyllic but ephemeral existence as an eloping "couple" at the inn. The inn-keeper himself (the "guv'nor") is absent in York, trying to locate the children's relatives, and so has ordered Cobbs to find pretexts effectively preventing their departure for Gretna Green across the Scottish border. Hence, Cobbs offers the ebullient Master Harry one of the village's few attractions, "Love's Lane." In E. A. Abbey's Harper and Brothers Household Edition large-scale wood-engraving, There's Love's Lane, both the chambermaid and Cobbs are amused by Harry's attitude as they escort a sleepy Norah up to her room by candlelight. Thus, Abbey imbues the figures with an inner life that is wholly lacking in the "Bed o' Ware" scene in the Diamond Edition of 1867, rushed to press to promote Dickens's forthcoming American reading tour.

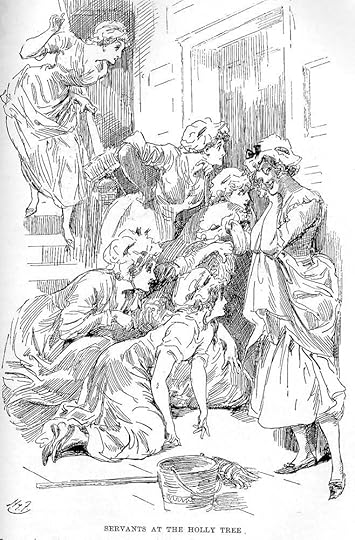

Servants at The Holly Tree

Harry Furniss

1910

Text Illustrated:

The way in which the women of that house — without exception — every one of 'em — married and single — took to that boy when they heard the story, Boots considers surprising. It was as much as he could do to keep 'em from dashing into the room and kissing him. They climbed up all sorts of places, at the risk of their lives, to look at him through a pane of glass. They was seven deep at the keyhole. They was out of their minds about him and his bold spirit.

Commentary:

In this scene Furniss does not depict Cobbs, who is the observer of but not an actor in the scene. Furniss's realisation of the passage in which the inn's female servants — presumably "the women of the house" encompasses both chamber- and barmaids — gather outside Master Harry's door to spy upon him through the glass and the keyhole is far from the static Sixties realism of Harry French in the Illustrated Library Edition of forty years earlier. Furniss's impressionistic rendering of the staircase scene is highly dynamic as each of the attractive young women assumes a different pose around the door.

The scene occurs on the second floor of the rambling, old Yorkshire coaching inn from which the novella takes its name (in Dickens's mind based on The George and New Inn, Gretna Bridge, where the novelist stayed in 1838 while investigating the notorious Yorkshire schools for Nicholas Nickleby — April 1838 through October 1839 — which he epitomised in Squeers' Dotheboys Hall). However, all that we see in Furniss's drawing of the interior of the inn is the landing and stairs, his emphasis being on the comely young women whom he individualises by their poses rather than by their faces, forms, and costumes. A clever touch, however, that implies the servants' longing for romance and their own escape from the quotidien is the bucket and mop displayed prominently, down centre, and the push-broom, left of centre.

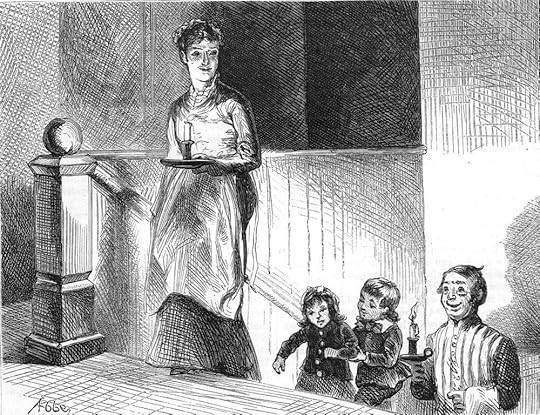

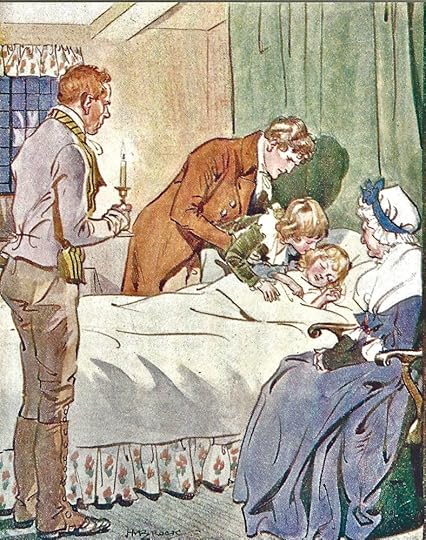

"There's Love Lane"

Second Branch

E. A. Abbey

From the Harper and Brothers Household Edition (1876) of Dickens Christmas Stories.

Commentary:

The sentimental frame tale involving the chief narrator, benighted on Christmas Eve in the middle of a Yorkshire blizzard, and the story-telling "Boots" of the inn has a certain nostalgic charm as Dickens recalls hostelries and transportation from the days before railways (as when, as a young reporter, Dickens raced about the country in coaches to follow events preceding the passage of the Great Reform Bill of 1832. Dickens himself provided just the introduction, a short story — the subject of Abbey's illustration — and the brief epilogue, leaving production of the other four pieces to his stable of staff writers. The much larger "Holly-Tree Inn" originally appeared without illustration in the sixth Extra Christmas number of Household Words, on 15 December 1855. Perhaps because only Dickens's contributions have been widely reprinted, posterity has lost sight of the other tales in the sequence, although these were penned by some of the mid-nineteenth-century's more popular writers of journalistic short fiction: William Howitt, Wilkie Collins, Adelaide Proctor, and Harriet Parr, the last three of whom got their start as professional writers on the staff of Household Words.

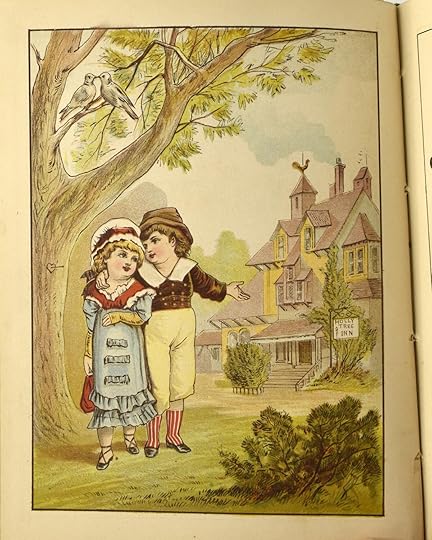

Text Illustrated:

Boots withdrew in search of the required restorative, and, when he brought it in, the gentleman handed it to the lady, and fed her with a spoon, and took a little himself; the lady being heavy with sleep, and rather cross. "What should you think, sir," says Cobbs, "of a chamber candlestick?" The gentleman approved; the chambermaid went first, up the great staircase; the lady, in her sky-blue mantle, followed, gallantly escorted by the gentleman; the gentleman embraced her at her door, and retired to his own apartment, where Boots softly locked him in.

Boots couldn't but feel with increased acuteness what a base deceiver he was, when they consulted him at breakfast (they had ordered sweet milk-and-water, and toast and currant jelly, over-night) about the pony. It really was as much as he could do, he don't mind confessing to me, to look them two young things in the face, and think what a wicked old father of lies he had grown up to be. Howsomever, he went on a-lying like a Trojan about the pony. He told 'em that it did so unfortunately happen that the pony was half clipped, you see, and that he couldn't be taken out in that state, for fear it should strike to his inside. But that he'd be finished clipping in the course of the day, and that to-morrow morning at eight o'clock the pheayton would be ready. Boots' view of the whole case, looking back on it in my room, is, that Mrs. Harry Walmers, Junior, was beginning to give in. She hadn't had her hair curled when she went to bed, and she didn't seem quite up to brushing it herself, and its getting in her eyes put her out. But nothing put out Master Harry. He sat behind his breakfast-cup, a-tearing away at the jelly, as if he had been his own father.

After breakfast Boots is inclined to consider they drawed soldiers — at least he knows that many such was found in the fireplace, all on horseback. In the course of the morning Master Harry rang the bell — it was surprising how that there boy did carry on — and said, in a sprightly way, "Cobbs, is there any good walks in this neighborhood?"

"Yes, sir," says Cobbs. "There's Love Lane."

"Get out with you, Cobbs!" — that was that there boy's expression — "you're joking."

"Begging your pardon, sir," says Cobbs, "there really is Love Lane. And a pleasant walk it is, and proud shall I be to show it to yourself and Mrs. Harry Walmers, Junior."

"Norah, dear," says Master Harry, "this is curious. We really ought to see Love Lane. Put on your bonnet, my sweetest darling, and we will go there with Cobbs."

As the above except makes clear, the title of Abbey's illustration ("There's Love Lane") has little to do with the maid's lighting Mr. and Mrs. Harry Walmers, Junior, up the stairs to their room in the second of seven selections (including a poem) about a Yorkshire Inn, perhaps based on the well-known George and New Inn at Greta Bridge. Retelling what he has been told by Cobbs, the "Boots" (that is, the hotel employee who, like Sam Weller in The Pickwick Papers of 1836-37, cleans boots and is the general factotum for a coaching inn), Dickens narrates the tale of the asexual attraction of two precocious children, Norah and Harry, who plan to elope to Gretna Green in Scotland. The humour of the story lies in the children behaving like adults, a strategy that Dickens would employ again in A Holiday Romance in Our Young Folks in 1867. When called upon by the traveller for a tale, the loquacious Cobbs recalls when, as the under-gardener to Mr. Walmers at Shooter's Hill, about seven miles from London, he had watched young Master Harry and Norah play in the garden, and goes on to narrate how the trajectory of their romance led to their being guests at the Holly Tree Inn in Yorkshire. Without the four contributions of Dickens's collaborators, the piece was often reprinted as "Boots at The Holly-tree Inn," the second of "The Holly-Tree: Three Branches." Cobbs's narrative as retailed by traveller (a first-person narrative at one remove, so to speak, for Dickens's focal character of the frame remains in charge of telling the story, although quoting Cobbs liberally) gives Dickens the opportunity to lapse into dialect and to offer a unique class perspective on the antics of the two charming, privileged children and their idyllic but ephemeral existence as a "couple" at the inn. The inn-keeper himself (the "guv'nor") is absent in York, trying to locate the children's relatives, and so has ordered Cobbs to find pretexts effectively preventing their departure for Gretna Green. Hence, Cobbs offers Master Harry one of the village's few attractions, "Love's Lane." In Abbey's illustration, both the maid and Cobbs are amused by Harry's attitude as they escort a sleepy Norah up to her room by candlelight.

The American Household Edition of The Holly Tree Inn, the remnant (as it were) of the mixed genre frame-tale for the 1855 Extra Christmas Number of Household Words contains only those components which Dickens himself wrote, so that (as in the later Oxford Illustrated Dickens) the multi-part frame-tale is reduced to just three chapters: "First Branch: Myself," "Second Branch: The Boots," and "Third Branch: The Bill."

Harry French's illustration of the genial Cobbs, watering can in hand, and a much larger Master Harry,"The Holly Tree Inn" realizes an earlier moment in Cobbs's account, when, instead of serving as a boots at a remote inn in the English north, he was under-gardener to Mr. Harry Walmers, Senior, on his estate at Shooter's Hill. Harry's father makes a reappearance at the conclusion of the story as Harry Jr.'s misrule comes to an abrupt end, and prosaic adult order restored. Since the filtering consciousness of the "Boots" account, Cobbs, is such an important aspect of the first-person narrative of the abortive attempt of Master Harry Walmers, Junior, to run off with Norah to be married at Gretna Green, it is unfortunate that in his illustration Harry and Norah, the maid and Cobbs Abbey has focussed on the attitude of the maid (left). In contrast, Harry French has elected to describe the affable Cobbs in his previous incarnation as a gardener, and therefore does not depict the chief characters in the story's principal setting. Although Abbey realizes a scene at the Holly Tree Inn, the American illustrator gives the reader no sense of the interior of the posting inn; indeed, the staircase is totally undistinguished, and the child actors not particularly engaging. Abbey's Norah seems surly, sleepy, and generally unattractive. Thus, Abbey's illustration fails to communicate the charm of Dickens's original narrative with respect to either the setting, or Harry, or Cobbs.

Mrs. Harry Walmers, Fatigued.

Henry Matthew Brock

1916

Text Illustrated:

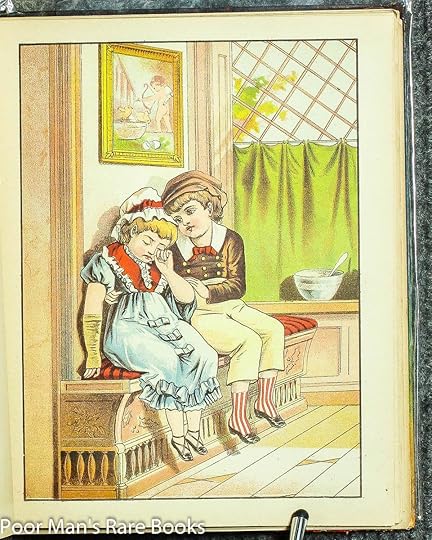

In the evening, Boots went into the room to see how the runaway couple was getting on. The gentleman was on the window-seat, supporting the lady in his arms. She had tears upon her face, and was lying, very tired and half asleep, with her head upon his shoulder.

"Mrs. Harry Walmers, Junior, fatigued, sir?" says Cobbs.

"Yes, she is tired, Cobbs; but she is not used to be away from home, and she has been in low spirits again. Cobbs, do you think you could bring a biffin, please?"

The father lifts the child up to the pillow.

Henry Matthew Brock

1916

Text Illustrated:

"Harry, my dear boy! Harry!"

Master Harry starts up and looks at him. Looks at Cobbs, too. Such is the honour of that mite, that he looks at Cobbs, to see whether he has brought him into trouble.

"I'm not angry, my child. I only want you to dress yourself and come home."

"Yes, Pa."

Master Harry dresses himself quickly. His breast begins to swell when he has nearly finished, and it swells more and more as he stands, at last, a-looking at his father; his father standing a-looking at him, the quiet image of him.

"Please may I" — the spirit of that little creatur', and the way he kept his rising tears down! — "please, dear Pa--may I — kiss Norah before I go?"

"You may, my child."

So he takes Master Harry in his hand, and Boots leads the way with the candle, and they come to that other bedroom, where the elderly lady is seated by the bed, and poor little Mrs. Harry Walmers, Junior, is fast asleep. There the father lifts the child up to the pillow, and he lays his little face down for an instant by the little warm face of poor unconscious little Mrs. Harry Walmers, Junior, and gently draws it to him — a sight so touching to the chambermaids, who are peeping through the door, that one of them called out, "It's a shame to part 'em!" But this chambermaid was always, as Boots informs us, a softhearted one. Not that there was any harm in that girl. Far from it.

Commentary:

The idyll concludes pleasantly when Harry's father, summoned by Cobbs, appears at the inn with the "Governor in a chaise", along with Norah's grandmother, to take the children home. In the concluding paragraph, we learn that the children never get to marry one another; rather, as a young woman, Norah marries a Captain in the regular army, and later dies in India, a place that was much on Dickens's mind as he had intended that his sons serve in the military there — Walter Landor Dickens (1841-1864) left England to take up the post of cadet in the private army of the British East India Company and never returned — and two years after Dickens wrote this Christmas story, the Sepoy Mutiny broke out near Delhi. The additional tailpiece here is a heart-shaped wreath of holly.

At The Holly Tree Inn - antique color lithograph from 1898 Charles Dickens book Beautiful Stories About Children

As for the artist:

The Holly Tree Inn

Henry French

1911

Commentary:

Dickens's The Holly-Tree Inn, originally published in Household Words, Extra Christmas Number, December 1855. "The Guest," "The Boots," and "The Bill," parts one, three, and seven respectively, were by Dickens, the other contributors being his chief collaborator, Wilkie Collins, William Howitt, Adelaide Anne Procter, and Harriet Parr ("Holme Lee"). The colourful cover, with snow scene of the inn and a carriage, suggests a chronological setting prior to the Railway Age, an impression that the 18th c. costumes of the ostler and his wife reinforce. The packaging (or, more accurately, re-packaging) of the framed-tale from Household Words suggests that Hodder and Stoughton were marketing the slight, 40-page volume as a children's book for Christmas sixty years after its initial publication, permissible under the revised provision of the Imperial Copyright Act of 1911, which implemented the Berne Convention (1886). Although Dickens died in 1870 and copyright on his works therefore ran until 1920 (fifty years after the author's death), the old provision would have given the publishers to right to publish the novella since, under the Copyright Act (1842) the term was 42 years from the publication of the work, or the lifetime of the author and seven years thereafter, whichever was the longer. Even though the original work involved multiple authors, this text contains only Dickens's contributions, and therefore until 1911 would have been free of copyright limitations from 1897. In all likelihood, Stodder and Houghton paid the estate and Chapman and Hall a modest royalty.

I’m spoilt by A Christmas Carol. It is so good and cast such a wide shadow that no other Christmas story can compare.

Christmas is a time for joy, love, and children so we do have the basic ingredients for a promising story in The Holly Tree. I too liked Part Two better than Part One. In “Boots” we find childish innocence, promises for the future, and tighter writing than Part One. There was so much tumbling through Part One I’m worried that I confused you all more than helped you. I confused myself.

I wonder how much our Victorian ancestors saw the marriages of very young couples in the same light as we do? Certainly life expectancy’s were shorter, and a person’s working conditions generally more challenging than in today’s world. How much of the knowledge of such factors lead to generally earlier marriages.

I also wonder how much the poor really concerned themselves with the quick trip to Scotland of the youth of the day, especially if the couples were from the working or lower classes?

Christmas is a time for joy, love, and children so we do have the basic ingredients for a promising story in The Holly Tree. I too liked Part Two better than Part One. In “Boots” we find childish innocence, promises for the future, and tighter writing than Part One. There was so much tumbling through Part One I’m worried that I confused you all more than helped you. I confused myself.

I wonder how much our Victorian ancestors saw the marriages of very young couples in the same light as we do? Certainly life expectancy’s were shorter, and a person’s working conditions generally more challenging than in today’s world. How much of the knowledge of such factors lead to generally earlier marriages.

I also wonder how much the poor really concerned themselves with the quick trip to Scotland of the youth of the day, especially if the couples were from the working or lower classes?

Peter wrote: "I’m spoilt by A Christmas Carol. It is so good and cast such a wide shadow that no other Christmas story can compare.

Christmas is a time for joy, love, and children so we do have the basic ingre..."

I think with the poor, the rules of whom to marry were less strict anyway. It probably were the rich going to Gretna Green

Christmas is a time for joy, love, and children so we do have the basic ingre..."

I think with the poor, the rules of whom to marry were less strict anyway. It probably were the rich going to Gretna Green

I don't think the blacksmith in Gretna Green would have married two eight-year olds if they had ever shown up in front of him even though life expectancy was on the average much lower than it is today. I once read that the average age of marriage was actually rather high in Europe before the Industrial Revolution as people were expected not to marry before they could be pretty sure to earn a living for themselves and their offspring - all the more so as there was no social security system and people depended on their neighbours and their parish for any support in case of dearth. When general wealth rose, for most people modestly, but still pereceptibly, in the wake of industrialization and when urbanization increased anonymity, the average age of marriage started to sink - but still, as far as I know, eight-year olds were not generally regarded as marriage candidates.

No, I don't think so either. Those two eight-year-olds probably heard some about Gretna Green - their former under-gardener worked in an inn on the way there, so I suppose they did not live all that far from there. And as it goes with children, stories got into their heads, especially in the head of the little boy I guess. But while I have heard about fourteen-year-olds or fifteen-year-olds marrying in those times, eight years old probably was way too young back then too.

This brought out to me that really, I'm not a fan of children. Other people's children of course. Even mine could get on my nerves, but usually didn't because they knew how mad I'd get so they didn't do things like touch every house in the village breaking quite a few, chasing the dog all over the house, then running to their parents when the dog started barking because they were afraid, me telling them not to run and she wouldn't chase them never helped. But the average child seems to talk, and talk a lot, and talk loud, it gives me headaches. Almost as bad is the child who doesn't say a word but you happen to end up in the same place with and since you are the adult you should have some sort of conversation with the child, only you can't think of a thing to say. Most people ask them how they like school, but since I have no interest in a conversation with an 8 year old about school we are left with nothing to say. So I am given a chapter with two children and not much else. And they are the two type I just mentioned, Master Harry would be the talk, talk, talk type and Norah almost never opens her mouth, then because Harry seems extremely spoiled he expects you to actually listen to him and do whatever it is he wants you to do. I would tend to neither listen or obey.

Anyway, Boots tells us a story about Master Harry Walmers, Boots happened to work for Master Harry's father as under-gardener and was always about in the summer, so he got to know the boy pretty well. One day Master Harry tells him that he is in love with Norah, a little girl in the neighborhood. He tells him that one day when he and Norah are married Boots shall go and be the head-gardener for them. Soon after this our under-gardener leaves the Walmers to go find his fortune and ends up working at The Holly Tree Inn not finding his fortune I would think.

Then one day in to the inn comes Master Harry and little Norah, they have run away and are on their way to Gretna Green to be married. It seems to me there are a lot of people who go to Gretna Green to be married, I'll have to look up why later. We're told everyone is amazed to see these two tiny creatures walk in, order chops and cherry-pudding for two, a sitting room, and two bedrooms. Boots tells the inn owner who they are and he leaves to tell their families where the children are. Meanwhile Boots shows himself to the two children who are extremely happy to see him. Boots then spends the next day keeping the children with him until their parents can arrive. As for the rest of the story, it isn't long and we all just read it together, so I'm sure you remember it without any more from me. So what do you think of these two dear children? Hopefully you liked them better than I do. And why are they the focus of the second part anyway? Couldn't they have at least run away at Christmas time? This book seems less Christmasy all the time. I wonder what put this story in Dickens head, if at sometime while staying at all the inns he did, if something similar happened. And I'm still waiting for the Christmas part of the story to begin. People getting murdered and eaten in the first part, and children running away in the summer aren't what I want in a Christmas story.