The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit

>

Little Dorrit, Book 1, Chp. 09-11

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 10, “Containing the Whole Science of Government“, shows, as I said, Dickens, once again, at his satirical best because we get introduced to the Circumlocution Office, which I would never have located in England but rather in my native country, Germany – which, to me at least, seems to be the perfect example of Circumlocution in any possibly imaginable way.

Now, the beginning of Chapter 10 is a brilliant satire, in which Dickens has a go at the cumbersome administration of public affairs, which is less a real form of administration and management but more a self-serving system of sinecures. Hence probably the name of Barnacle, which seems to be inseparable from the Circumlocution Office. A barnacle is a kind of crab that sticks to ships, rocks, blue mussels, or other shellfish and that will not change its position and thus it is a telling name, because the Barnacles stick to the Ship of State for all their lives’ worth. Kim might provide a picture of barnacles, since I have not mastered the art of inserting pictures yet. Among other things, the narrator says this of the Circumlocution Office:

”The Circumlocution Office was (as everybody knows without being told) the most important Department under Government. No public business of any kind could possibly be done at any time without the acquiescence of the Circumlocution Office. Its finger was in the largest public pie, and in the smallest public tart. It was equally impossible to do the plainest right and to undo the plainest wrong without the express authority of the Circumlocution Office. If another Gunpowder Plot had been discovered half an hour before the lighting of the match, nobody would have been justified in saving the parliament until there had been half a score of boards, half a bushel of minutes, several sacks of official memoranda, and a family-vault full of ungrammatical correspondence, on the part of the Circumlocution Office.

This glorious establishment had been early in the field, when the one sublime principle involving the difficult art of governing a country, was first distinctly revealed to statesmen. It had been foremost to study that bright revelation and to carry its shining influence through the whole of the official proceedings. Whatever was required to be done, the Circumlocution Office was beforehand with all the public departments in the art of perceiving—HOW NOT TO DO IT.”

How not to do it really means “not doing a thing” instead of “doing a thing the wrong way”, and therefore let me tell you again that the Circumlocution Office is probably a very German thing. Mr. Clennam is true to his business, or rather the Dorrits’ business, which can hardly be called his own but which he seems to be vividly interested in for no apparent reason at all, and therefore he decides to go to the Circumlocution Office in order to talk things over with Mr. Tite Barnacle. However, he only finds this worthy’s son there and is referred to the Barnacle House in the vicinity of Grosvenor Square. We are told that the house is ”a squeezed house” and rather shabby but that its closeness, not its closeness as such but its closeness to the prestigious address, makes it worthwhile for the likes of the Barnacles to pay very high rents in order to live there. Mr. Tite Barnacle, who is suffering from a bout of the gout, shows himself very unwilling to answer Clennam’s questions about the nature of Mr. Dorrit’s debts in a straightforward way but prefers to take recourse to circumlocution. In my opinion, of course, he is absolutely entitled to this course of action, or rather inaction, because why should he account to some stranger, who has no apparent concern in the matter?

From Mr. Barnacle’s answer, Clennam gathers that Mr. Dorrit is in debt with a Circumlocution-Office-related business, and he goes back to that institution to get further answers. Here, however, he gets some first-rate experience of the insolence of office and the spurn that patient merit – or impatient curiosity – of the unworthy takes. Finally, he ends up with another Barnacle, this time a very young and dapper gentleman, who explains to him the proper procedure in order to get, maybe, some information:

”’But surely this is not the way to do the business,’ Arthur Clennam could not help saying.

This airy young Barnacle was quite entertained by his simplicity in supposing for a moment that it was. This light in hand young Barnacle knew perfectly that it was not. This touch and go young Barnacle had 'got up' the Department in a private secretaryship, that he might be ready for any little bit of fat that came to hand; and he fully understood the Department to be a politico-diplomatic hocus pocus piece of machinery for the assistance of the nobs in keeping off the snobs. This dashing young Barnacle, in a word, was likely to become a statesman, and to make a figure.

‘When the business is regularly before that Department, whatever it is,’ pursued this bright young Barnacle, ‘then you can watch it from time to time through that Department. When it comes regularly before this Department, then you must watch it from time to time through this Department. We shall have to refer it right and left; and when we refer it anywhere, then you'll have to look it up. When it comes back to us at any time, then you had better look us up. When it sticks anywhere, you'll have to try to give it a jog. When you write to another Department about it, and then to this Department about it, and don't hear anything satisfactory about it, why then you had better—keep on writing.’

Arthur Clennam looked very doubtful indeed. ‘But I am obliged to you at any rate,’ said he, ‘for your politeness.’

‘Not at all,’ replied this engaging young Barnacle. ‘Try the thing, and see how you like it. It will be in your power to give it up at any time, if you don't like it. You had better take a lot of forms away with you. Give him a lot of forms!’ With which instruction to number two, this sparkling young Barnacle took a fresh handful of papers from numbers one and three, and carried them into the sanctuary to offer to the presiding Idol of the Circumlocution Office.”

I could not help thinking of Franz Kafka’s novel Der Prozeß at this point because the situation had grown to be quite absurd and nightmarish – in short, Kafkaesque – by then, and I am eager to learn how Mr. Clennam is going to fare in his dealings with the Circumlocution Office. It seems as though we had entered another kind of prison here, which only deals in life sentences and whose walls are nearly as impenetrable as those of a prison made of stone. Woe betide him who has some important business to do and depends for its successful conclusion on the Circumlocution Office. I really like that word.

On leaving, Mr. Clennam runs into his old acquaintance Mr. Meagles, who is somehow related to an engineer and inventor by the name of Daniel Doyce. Doyce is one of those who have to deal with the Office because twelve years ago he made an important invention which could prove very useful to his country – we don’t learn what kind of invention this is – and whose attempts at putting this invention to use are continuously balked by the gentlemen working in the Circumlocution Office. Mr. Meagles tells Arthur that Doyce is treated like a kind of criminal, and Doyce admits that his situation is extremely frustrating. At the end of the chapter, Clennam, Meagles and Doyce betake themselves to Bleeding Heart Yard, where Mr. Doyce’s factory is situated.

Now, the beginning of Chapter 10 is a brilliant satire, in which Dickens has a go at the cumbersome administration of public affairs, which is less a real form of administration and management but more a self-serving system of sinecures. Hence probably the name of Barnacle, which seems to be inseparable from the Circumlocution Office. A barnacle is a kind of crab that sticks to ships, rocks, blue mussels, or other shellfish and that will not change its position and thus it is a telling name, because the Barnacles stick to the Ship of State for all their lives’ worth. Kim might provide a picture of barnacles, since I have not mastered the art of inserting pictures yet. Among other things, the narrator says this of the Circumlocution Office:

”The Circumlocution Office was (as everybody knows without being told) the most important Department under Government. No public business of any kind could possibly be done at any time without the acquiescence of the Circumlocution Office. Its finger was in the largest public pie, and in the smallest public tart. It was equally impossible to do the plainest right and to undo the plainest wrong without the express authority of the Circumlocution Office. If another Gunpowder Plot had been discovered half an hour before the lighting of the match, nobody would have been justified in saving the parliament until there had been half a score of boards, half a bushel of minutes, several sacks of official memoranda, and a family-vault full of ungrammatical correspondence, on the part of the Circumlocution Office.

This glorious establishment had been early in the field, when the one sublime principle involving the difficult art of governing a country, was first distinctly revealed to statesmen. It had been foremost to study that bright revelation and to carry its shining influence through the whole of the official proceedings. Whatever was required to be done, the Circumlocution Office was beforehand with all the public departments in the art of perceiving—HOW NOT TO DO IT.”

How not to do it really means “not doing a thing” instead of “doing a thing the wrong way”, and therefore let me tell you again that the Circumlocution Office is probably a very German thing. Mr. Clennam is true to his business, or rather the Dorrits’ business, which can hardly be called his own but which he seems to be vividly interested in for no apparent reason at all, and therefore he decides to go to the Circumlocution Office in order to talk things over with Mr. Tite Barnacle. However, he only finds this worthy’s son there and is referred to the Barnacle House in the vicinity of Grosvenor Square. We are told that the house is ”a squeezed house” and rather shabby but that its closeness, not its closeness as such but its closeness to the prestigious address, makes it worthwhile for the likes of the Barnacles to pay very high rents in order to live there. Mr. Tite Barnacle, who is suffering from a bout of the gout, shows himself very unwilling to answer Clennam’s questions about the nature of Mr. Dorrit’s debts in a straightforward way but prefers to take recourse to circumlocution. In my opinion, of course, he is absolutely entitled to this course of action, or rather inaction, because why should he account to some stranger, who has no apparent concern in the matter?

From Mr. Barnacle’s answer, Clennam gathers that Mr. Dorrit is in debt with a Circumlocution-Office-related business, and he goes back to that institution to get further answers. Here, however, he gets some first-rate experience of the insolence of office and the spurn that patient merit – or impatient curiosity – of the unworthy takes. Finally, he ends up with another Barnacle, this time a very young and dapper gentleman, who explains to him the proper procedure in order to get, maybe, some information:

”’But surely this is not the way to do the business,’ Arthur Clennam could not help saying.

This airy young Barnacle was quite entertained by his simplicity in supposing for a moment that it was. This light in hand young Barnacle knew perfectly that it was not. This touch and go young Barnacle had 'got up' the Department in a private secretaryship, that he might be ready for any little bit of fat that came to hand; and he fully understood the Department to be a politico-diplomatic hocus pocus piece of machinery for the assistance of the nobs in keeping off the snobs. This dashing young Barnacle, in a word, was likely to become a statesman, and to make a figure.

‘When the business is regularly before that Department, whatever it is,’ pursued this bright young Barnacle, ‘then you can watch it from time to time through that Department. When it comes regularly before this Department, then you must watch it from time to time through this Department. We shall have to refer it right and left; and when we refer it anywhere, then you'll have to look it up. When it comes back to us at any time, then you had better look us up. When it sticks anywhere, you'll have to try to give it a jog. When you write to another Department about it, and then to this Department about it, and don't hear anything satisfactory about it, why then you had better—keep on writing.’

Arthur Clennam looked very doubtful indeed. ‘But I am obliged to you at any rate,’ said he, ‘for your politeness.’

‘Not at all,’ replied this engaging young Barnacle. ‘Try the thing, and see how you like it. It will be in your power to give it up at any time, if you don't like it. You had better take a lot of forms away with you. Give him a lot of forms!’ With which instruction to number two, this sparkling young Barnacle took a fresh handful of papers from numbers one and three, and carried them into the sanctuary to offer to the presiding Idol of the Circumlocution Office.”

I could not help thinking of Franz Kafka’s novel Der Prozeß at this point because the situation had grown to be quite absurd and nightmarish – in short, Kafkaesque – by then, and I am eager to learn how Mr. Clennam is going to fare in his dealings with the Circumlocution Office. It seems as though we had entered another kind of prison here, which only deals in life sentences and whose walls are nearly as impenetrable as those of a prison made of stone. Woe betide him who has some important business to do and depends for its successful conclusion on the Circumlocution Office. I really like that word.

On leaving, Mr. Clennam runs into his old acquaintance Mr. Meagles, who is somehow related to an engineer and inventor by the name of Daniel Doyce. Doyce is one of those who have to deal with the Office because twelve years ago he made an important invention which could prove very useful to his country – we don’t learn what kind of invention this is – and whose attempts at putting this invention to use are continuously balked by the gentlemen working in the Circumlocution Office. Mr. Meagles tells Arthur that Doyce is treated like a kind of criminal, and Doyce admits that his situation is extremely frustrating. At the end of the chapter, Clennam, Meagles and Doyce betake themselves to Bleeding Heart Yard, where Mr. Doyce’s factory is situated.

Chapter 11 starts with the portentous title “Let Loose”, and swiftly carries us back to France, where we witness a wanderer on his way to Chalons on a dull autumn night. Already the man’s vengeful words directed at the unwitting and actually unoffending inhabitants of the town, who have it nice and snug, whereas he still feels he has miles to go, show us that he is not too pleasant a customer:

”’I, hungry, thirsty, weary. You, imbeciles, where the lights are yonder, eating and drinking, and warming yourselves at fires! I wish I had the sacking of your town; I would repay you, my children!’”

He finally arrives at Chalons and looks for a cheap tavern, where he can spend the night. The ‘Break of Day’ offers itself to him, and when he orders his meal, he notices a group of men talking about a murderer that has been released in Marseilles because they could not prove his crime, murdering his wife, against him. One of the men says that the angry people of Marseilles said that that night the devil was let loose again, and the murderer is identified as one Rigaud. The landlady, on hearing one of her guests surmise that the man may have had “an unfortunate destiny” and that he may have been “the child of circumstances”, indignantly offers the following observations:

”’Hold there, you and your philanthropy,’ cried the smiling landlady, nodding her head more than ever. ‘Listen then. I am a woman, I. I know nothing of philosophical philanthropy. But I know what I have seen, and what I have looked in the face in this world here, where I find myself. And I tell you this, my friend, that there are people (men and women both, unfortunately) who have no good in them—none. That there are people whom it is necessary to detest without compromise. That there are people who must be dealt with as enemies of the human race. That there are people who have no human heart, and who must be crushed like savage beasts and cleared out of the way. They are but few, I hope; but I have seen (in this world here where I find myself, and even at the little Break of Day) that there are such people. And I do not doubt that this man—whatever they call him, I forget his name—is one of them.’”

Not only do most of her guests concur with her speech, but so does the narrator, who comments as follows:

”The landlady's lively speech was received with greater favour at the Break of Day, than it would have elicited from certain amiable whitewashers of the class she so unreasonably objected to, nearer Great Britain.”

It seems like the landlady (and Dickens) has given an apt definition of a psychopath and voiced the not quite unjustified idea that the business of the law should be rather to protect society from criminals rather than try to reform the criminal at all costs. In this case, however, it seems to have been a question of evidence, and not so much of “amiable whitewashing”, as the narrator puts it.

When she deals with her new guest, the landlady is never quite sure whether she has a good-looking man in front of her, or an extremely ill-looking specimen of humanity. We readers might already have noticed his nose going over his moustache in that typically mousetrap-like way that characterized Rigaud. Finally, the guest is led into his bedroom, which he has to share with another traveller, who has gone to bed very early. This sleeping guest is identified by the newcomer as Cavalletto, and now we are sure that the other traveller is Rigaud, who has, for obvious reasons, changed his name, and is now called Lagnier.

Lagnier wakes the unsuspecting Cavalletto – mark how the narrator describes the little evil white hand! – and seems to take it for granted that the other man will now join him as a kind of sidekick. He pours out his vengeful heart to Cavalletto, like this:

”’I am a man,’ said Monsieur Lagnier, ‘whom society has deeply wronged since you last saw me. You know that I am sensitive and brave, and that it is my character to govern. How has society respected those qualities in me? I have been shrieked at through the streets. I have been guarded through the streets against men, and especially women, running at me armed with any weapons they could lay their hands on. I have lain in prison for security, with the place of my confinement kept a secret, lest I should be torn out of it and felled by a hundred blows. I have been carted out of Marseilles in the dead of night, and carried leagues away from it packed in straw. It has not been safe for me to go near my house; and, with a beggar's pittance in my pocket, I have walked through vile mud and weather ever since, until my feet are crippled—look at them! Such are the humiliations that society has inflicted upon me, possessing the qualities I have mentioned, and which you know me to possess. But society shall pay for it.‘

And he also announces his intention to go to Paris, and from there maybe to London – so we will probably meet him again there. When Lagnier has gone to sleep, Cavalletto takes the opportunity of quietly absconding – he has already paid his bill – in order to avoid any further contact with his self-styled patron. I hope we will not have seen the last of him since I quite like him.

”’I, hungry, thirsty, weary. You, imbeciles, where the lights are yonder, eating and drinking, and warming yourselves at fires! I wish I had the sacking of your town; I would repay you, my children!’”

He finally arrives at Chalons and looks for a cheap tavern, where he can spend the night. The ‘Break of Day’ offers itself to him, and when he orders his meal, he notices a group of men talking about a murderer that has been released in Marseilles because they could not prove his crime, murdering his wife, against him. One of the men says that the angry people of Marseilles said that that night the devil was let loose again, and the murderer is identified as one Rigaud. The landlady, on hearing one of her guests surmise that the man may have had “an unfortunate destiny” and that he may have been “the child of circumstances”, indignantly offers the following observations:

”’Hold there, you and your philanthropy,’ cried the smiling landlady, nodding her head more than ever. ‘Listen then. I am a woman, I. I know nothing of philosophical philanthropy. But I know what I have seen, and what I have looked in the face in this world here, where I find myself. And I tell you this, my friend, that there are people (men and women both, unfortunately) who have no good in them—none. That there are people whom it is necessary to detest without compromise. That there are people who must be dealt with as enemies of the human race. That there are people who have no human heart, and who must be crushed like savage beasts and cleared out of the way. They are but few, I hope; but I have seen (in this world here where I find myself, and even at the little Break of Day) that there are such people. And I do not doubt that this man—whatever they call him, I forget his name—is one of them.’”

Not only do most of her guests concur with her speech, but so does the narrator, who comments as follows:

”The landlady's lively speech was received with greater favour at the Break of Day, than it would have elicited from certain amiable whitewashers of the class she so unreasonably objected to, nearer Great Britain.”

It seems like the landlady (and Dickens) has given an apt definition of a psychopath and voiced the not quite unjustified idea that the business of the law should be rather to protect society from criminals rather than try to reform the criminal at all costs. In this case, however, it seems to have been a question of evidence, and not so much of “amiable whitewashing”, as the narrator puts it.

When she deals with her new guest, the landlady is never quite sure whether she has a good-looking man in front of her, or an extremely ill-looking specimen of humanity. We readers might already have noticed his nose going over his moustache in that typically mousetrap-like way that characterized Rigaud. Finally, the guest is led into his bedroom, which he has to share with another traveller, who has gone to bed very early. This sleeping guest is identified by the newcomer as Cavalletto, and now we are sure that the other traveller is Rigaud, who has, for obvious reasons, changed his name, and is now called Lagnier.

Lagnier wakes the unsuspecting Cavalletto – mark how the narrator describes the little evil white hand! – and seems to take it for granted that the other man will now join him as a kind of sidekick. He pours out his vengeful heart to Cavalletto, like this:

”’I am a man,’ said Monsieur Lagnier, ‘whom society has deeply wronged since you last saw me. You know that I am sensitive and brave, and that it is my character to govern. How has society respected those qualities in me? I have been shrieked at through the streets. I have been guarded through the streets against men, and especially women, running at me armed with any weapons they could lay their hands on. I have lain in prison for security, with the place of my confinement kept a secret, lest I should be torn out of it and felled by a hundred blows. I have been carted out of Marseilles in the dead of night, and carried leagues away from it packed in straw. It has not been safe for me to go near my house; and, with a beggar's pittance in my pocket, I have walked through vile mud and weather ever since, until my feet are crippled—look at them! Such are the humiliations that society has inflicted upon me, possessing the qualities I have mentioned, and which you know me to possess. But society shall pay for it.‘

And he also announces his intention to go to Paris, and from there maybe to London – so we will probably meet him again there. When Lagnier has gone to sleep, Cavalletto takes the opportunity of quietly absconding – he has already paid his bill – in order to avoid any further contact with his self-styled patron. I hope we will not have seen the last of him since I quite like him.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 10, “Containing the Whole Science of Government“, shows, as I said, Dickens, once again, at his satirical best because we get introduced to the Circumlocution Office, which I would never ha..."

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 10, “Containing the Whole Science of Government“, shows, as I said, Dickens, once again, at his satirical best because we get introduced to the Circumlocution Office, which I would never ha..."It took me about 3 times as long as usual to read this week's installment because the Circumlocution Office nearly killed me. I fell asleep twice in the middle of it. I usually enjoy Dickens's satire, but either I was exceptionally tired this week (possible) or the point about pointlessness was proved a little too well.

Not just you, Julie. I, too, for the first time ever in a Dickens book was BORED. It was overkill and that is not his usual style. I suppose he had to get his word allocation in for the publication. Worse Dickens I ever read. peace, janz

Not just you, Julie. I, too, for the first time ever in a Dickens book was BORED. It was overkill and that is not his usual style. I suppose he had to get his word allocation in for the publication. Worse Dickens I ever read. peace, janz

Tristram wrote: "All in all, Clennam feels an impulse of pity for and interest in Amy, and the following sentence seems to take up a typically Dickensian theme, if we think of Dr. Strong and his wife, or the difference in age between Florence and Walter, or between Esther and Mr. Jarndyce:

Tristram wrote: "All in all, Clennam feels an impulse of pity for and interest in Amy, and the following sentence seems to take up a typically Dickensian theme, if we think of Dr. Strong and his wife, or the difference in age between Florence and Walter, or between Esther and Mr. Jarndyce:”The little creature seemed so young in his eyes, that there were moments when he found himself thinking of her, if not speaking to her, as if she were a child. Perhaps he seemed as old in her eyes as she seemed young in his."

Dickens does like his May-Decembers, but this passage struck me mostly for how it gets picked up a few pages later: How young she seemed to him, or how old he to her; or what a secret either to the other, in that beginning of the destined interweaving of their stories, matters not here.

I found this so intriguing! And I also think it's true of any two people meeting, still secrets to each other and not knowing where that meeting might go.

But I'm still going to be surprised if Amy and Arthur end up romantically entangled (though it does have a nice ring to it, Amy-and-Arthur) because I'm still hung up on Arthur's pre-existing love interest. But who knows, maybe the pre-existing love interest will fall prey to the shifting of the story through serial numbers and be forgotten, if unable to be edited out, since the number she appeared in would have already have been in print.

I can't remember if we have talked about Arthur having a kingly name? So far he doesn't seem all that kingly to me. I agree with Tristram that the novel is kind of fuzzy about why he's so interested in the Dorrits at all. My best guess is he feels he's under some kind of family curse due to his mother's guilt about some sin of his father's (probably done with her encouragement), and has settled on the Dorrits being the source of this because he can't think why else his mother would be taking Amy in, or at least hiring her for work.

My alternate explanation would be that Arthur sure seems to have a lot of free time on his hands, and has taken to stalking young seamstresses out of boredom. But I don't think this is the direction the novel wants me to go.

In an amazing bit of coincidental timing, my daughter, who works for the Federal government, has been embroiled in her own battle with the "Circumlocution Office" over a payroll matter for the past 6 weeks or so. For me, not being the one dealing with it, I found great amusement in comparing her frustration with that of Arthur, Meagles, and Doyce. Knowing her as I do, however, I was circumspect enough to keep this literary coincidence to myself. One musn't poke the bear. But it truly is uncanny how bureaucracy hasn't improved one iota in more than 150 years. If anything, it's worse.

In an amazing bit of coincidental timing, my daughter, who works for the Federal government, has been embroiled in her own battle with the "Circumlocution Office" over a payroll matter for the past 6 weeks or so. For me, not being the one dealing with it, I found great amusement in comparing her frustration with that of Arthur, Meagles, and Doyce. Knowing her as I do, however, I was circumspect enough to keep this literary coincidence to myself. One musn't poke the bear. But it truly is uncanny how bureaucracy hasn't improved one iota in more than 150 years. If anything, it's worse.

Tristram wrote: "Her face was not exceedingly ugly, though it was only redeemed from being so by a smile; a good-humoured smile, and pleasant in itself, but rendered pitiable by being constantly there...."

Tristram wrote: "Her face was not exceedingly ugly, though it was only redeemed from being so by a smile; a good-humoured smile, and pleasant in itself, but rendered pitiable by being constantly there...."What are we to make of poor Maggy? Is her purpose just to show us the extent of Amy's compassion, or will she play a more significant role? I love the passage above, and Dickens' observation that the smile, while pleasant, was pitiable by its constant presence. How does he come up with these wonderful observations? I can't help but compare Maggy to Jenny Wren, despite her limitations being physical rather than mental.

Tristram wrote: "Cavalletto takes the opportunity of quietly absconding ...in order to avoid any further contact with his self-styled patron. I hope we will not have seen the last of him since I quite like him..."

Tristram wrote: "Cavalletto takes the opportunity of quietly absconding ...in order to avoid any further contact with his self-styled patron. I hope we will not have seen the last of him since I quite like him..."Poor Cavalletto. I like him, too. He must be wondering what bad karma is responsible for bringing Rigaud into his life, and what he must do to rid himself of the association once and for all. The Biblical John the Baptist was "a messenger being sent ahead, and a voice crying out in the wilderness" which gives me hope that Rigaud's new name will not always protect him, though I imagine we aren't done with his villainous ways. Let's hope that John Baptist Cavalletto doesn't suffer a similar fate to his namesake, who was beheaded.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Cavalletto takes the opportunity of quietly absconding ...in order to avoid any further contact with his self-styled patron. I hope we will not have seen the last of him since I qu..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Cavalletto takes the opportunity of quietly absconding ...in order to avoid any further contact with his self-styled patron. I hope we will not have seen the last of him since I qu..."Yes, I really like Cavalletto! I thought he was going to end up the perfect reluctant sidekick: nicer than the villain but too dumb to avoid being caught up in the currents of his charismatic ways and maybe somehow throwing the game off for him at the finale. But he had other ideas! Not so dumb after all.

I also love how the landlady can't make her mind up about Rigaud's looks. OK, Rigauld is awful--but apparently there's Something About Him--if not something enough to keep Cavalletto nearby. :)

I agree, I quite like Cavalletto too. All the more because he clearly does not like Rigaud either.

And yes, the Circumlocution Office-chapter was quite circumlocutious! I did send a part to my husband, who is fond of the series 'Yes, Minister'. I had to think of those all the time. And okay, goodreads nowadays doesn't let me link to youtube - but if you search for 'Yes, Minister' on there, be aware to get a lot more of circumlocution office.

And yes, the Circumlocution Office-chapter was quite circumlocutious! I did send a part to my husband, who is fond of the series 'Yes, Minister'. I had to think of those all the time. And okay, goodreads nowadays doesn't let me link to youtube - but if you search for 'Yes, Minister' on there, be aware to get a lot more of circumlocution office.

I just realized that the humor in the circumlocution office is only humorous when it is not me. When it is me, I am angry. peace, janz

I just realized that the humor in the circumlocution office is only humorous when it is not me. When it is me, I am angry. peace, janz

Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow Curiosities,

This week, we will finally get a glimpse into the proceedings of the wonderful Circumlocution Office and see Dickens at his satirical best. Before this can be done, howeve..."

Tristram

You mention the word “duty” in your summary. I think this is an apt word to give to Amy. Whether we agree with the lengths Little Dorrit goes in fulfilling what she believes is her duty to her father is another matter. She also performs the duty of a parent by securing employment for her sister and trying to secure an occupation for Tip. Mr Dorrit refuses to do any duty at all for his three children.

On the other hand we have the rather convoluted and mysterious duty that Arthur has towards his mother and her equally mysterious reason for not fulfilling her duty to her son.

The duty of a government agency is to assist its citizens but the Circumlocution and the Barnacle clan do everything possible to thwart Arthur, Mr Doyce and countless others.

I think we need to keep an eye on the concept of duty as we move through the novel.

I would not call Maggy “deplorable.” Maggy calls Little Dorrit “Little Mother.” That too is a duty Little Dorrit fulfills.

In Chapter 9 Mr Dorrit says “We should have been lost without Amy. She is a very good girl, Amy. She does her duty.” I think this statement is, at once, both shocking and revealing. It is shocking as it shows the way Mr Dorrit perceives the role of his youngest daughter. At the same time — although I’m sure Mr Dorrit did not mean his comment to be a compliment — it reveals how important performing one’s duty society is.

This week, we will finally get a glimpse into the proceedings of the wonderful Circumlocution Office and see Dickens at his satirical best. Before this can be done, howeve..."

Tristram

You mention the word “duty” in your summary. I think this is an apt word to give to Amy. Whether we agree with the lengths Little Dorrit goes in fulfilling what she believes is her duty to her father is another matter. She also performs the duty of a parent by securing employment for her sister and trying to secure an occupation for Tip. Mr Dorrit refuses to do any duty at all for his three children.

On the other hand we have the rather convoluted and mysterious duty that Arthur has towards his mother and her equally mysterious reason for not fulfilling her duty to her son.

The duty of a government agency is to assist its citizens but the Circumlocution and the Barnacle clan do everything possible to thwart Arthur, Mr Doyce and countless others.

I think we need to keep an eye on the concept of duty as we move through the novel.

I would not call Maggy “deplorable.” Maggy calls Little Dorrit “Little Mother.” That too is a duty Little Dorrit fulfills.

In Chapter 9 Mr Dorrit says “We should have been lost without Amy. She is a very good girl, Amy. She does her duty.” I think this statement is, at once, both shocking and revealing. It is shocking as it shows the way Mr Dorrit perceives the role of his youngest daughter. At the same time — although I’m sure Mr Dorrit did not mean his comment to be a compliment — it reveals how important performing one’s duty society is.

My vote is with Tristram when he calls the Circumlocution Office a brilliant bit of satirical writing. Sometimes satire makes us laugh and sometimes it makes us cringe. The Circumlocution Office made me both laugh and cringe.

The nepotism and circumlocution that exists in government offices (at least in Canada) is always poking its head up in our newspapers. I live in a condo which, like most condos, has a very comprehensive list of rules and by-laws the owners must follow. Well, that’s the theory until the exceptions and special circumstances poke their heads up.

To me the Circumlocution Office in the novel is as fresh as today’s news.

The nepotism and circumlocution that exists in government offices (at least in Canada) is always poking its head up in our newspapers. I live in a condo which, like most condos, has a very comprehensive list of rules and by-laws the owners must follow. Well, that’s the theory until the exceptions and special circumstances poke their heads up.

To me the Circumlocution Office in the novel is as fresh as today’s news.

Peter - do you live in my condo project? Our rules are absolute, until a favorite or a golf partner breaks them. peace, janz

Peter - do you live in my condo project? Our rules are absolute, until a favorite or a golf partner breaks them. peace, janz

Peacejanz wrote: "Peter - do you live in my condo project? Our rules are absolute, until a favorite or a golf partner breaks them. peace, janz"

Peacejanz

While we do not live in the same condo development it seems the Circumlocution facts are international. I think Dickens is spot on when he peels back the way governments and agencies function. At times when I read about the Circumlocution Office I can’t help but think about Heller’s Catch 22.

Peacejanz

While we do not live in the same condo development it seems the Circumlocution facts are international. I think Dickens is spot on when he peels back the way governments and agencies function. At times when I read about the Circumlocution Office I can’t help but think about Heller’s Catch 22.

Peacejanz wrote: "Not just you, Julie. I, too, for the first time ever in a Dickens book was BORED. It was overkill and that is not his usual style. I suppose he had to get his word allocation in for the publication..."

Julie and janz,

It's interesting how differently readers react to the same text: For me, the satire on the Circumlocution Office was extremely entertaining and brilliant, and not less so as I have my own experiences with the insolence of office (and above all, its slowness and disinclination to get things done), whereas the preceding chapter, the conversation between Amy and Arthur and the introduction of Maggy, was an ordeal for my patience. Once again, Dickens has a young heroine and an older protector and we can see where this might be going, and the heroine is oh so modest and oh so self-sacrificing and oh so dutiful to people who take her devotion for granted. As to Maggy, I really think that her main purpose in this chapter is to show Amy's goodness in another context.

The question why Arthur is so interested in Amy is a tricky one. The text states once or twice that he has an inkling that Little Dorrit and her family might have been wronged by his mother, but I think that this is the way Arthur wants to think since he is merely struck by Amy's modesty and decency. Here's an ageing man, who has never really put his foot down with his overbearing parents and never done what he wanted in his life, and what is more natural for this man but to feel interested in a young woman who is even more beholden to her family obligations and who likes devoting her life to her relatives? He can protect her, guide her and for once feel superior, gently superior to someone. That's at least what the cynic in me thinks.

Julie and janz,

It's interesting how differently readers react to the same text: For me, the satire on the Circumlocution Office was extremely entertaining and brilliant, and not less so as I have my own experiences with the insolence of office (and above all, its slowness and disinclination to get things done), whereas the preceding chapter, the conversation between Amy and Arthur and the introduction of Maggy, was an ordeal for my patience. Once again, Dickens has a young heroine and an older protector and we can see where this might be going, and the heroine is oh so modest and oh so self-sacrificing and oh so dutiful to people who take her devotion for granted. As to Maggy, I really think that her main purpose in this chapter is to show Amy's goodness in another context.

The question why Arthur is so interested in Amy is a tricky one. The text states once or twice that he has an inkling that Little Dorrit and her family might have been wronged by his mother, but I think that this is the way Arthur wants to think since he is merely struck by Amy's modesty and decency. Here's an ageing man, who has never really put his foot down with his overbearing parents and never done what he wanted in his life, and what is more natural for this man but to feel interested in a young woman who is even more beholden to her family obligations and who likes devoting her life to her relatives? He can protect her, guide her and for once feel superior, gently superior to someone. That's at least what the cynic in me thinks.

Peacejanz wrote: "I just realized that the humor in the circumlocution office is only humorous when it is not me. When it is me, I am angry. peace, janz"

Absolutely!

When I was in the army, I once sprained my ankle during an endurance run, and the corporal sent me to the sickbay to get some treatment. On arriving there, they told me that I should have reported injured by 8 o' clock in the morning and that, as I had failed to do so, they would not treat me that day but the next - provided that I reported on time the next morning. I argued and argued, saying that I could not possibly have known in the morning that I was to sprain my ankle in the afternoon, but to no avail, and so I hobbled back to my unit. There I happened to run into the lieutenant, who asked me why I was not in the infirmary, and I truthfully told him the story. Well, my lieutenant went there and made a vociferous end to Circumlocution there. A happy ending for me.

Absolutely!

When I was in the army, I once sprained my ankle during an endurance run, and the corporal sent me to the sickbay to get some treatment. On arriving there, they told me that I should have reported injured by 8 o' clock in the morning and that, as I had failed to do so, they would not treat me that day but the next - provided that I reported on time the next morning. I argued and argued, saying that I could not possibly have known in the morning that I was to sprain my ankle in the afternoon, but to no avail, and so I hobbled back to my unit. There I happened to run into the lieutenant, who asked me why I was not in the infirmary, and I truthfully told him the story. Well, my lieutenant went there and made a vociferous end to Circumlocution there. A happy ending for me.

Tristram wrote: "Peacejanz wrote: "Not just you, Julie. I, too, for the first time ever in a Dickens book was BORED. It was overkill and that is not his usual style. I suppose he had to get his word allocation in f..."

Tristram

Ah, the race between Little Nell and Little Dorrit for your affections. I think Nell will always be my favourite. Perhaps that is because there is a major age difference between the two, perhaps because I see Nell as totally focussed on her grandfather who is a hopeless case. Little Dorrit does have some semblance of a private life and individual choice, but admittedly her father is an anchor around her neck.

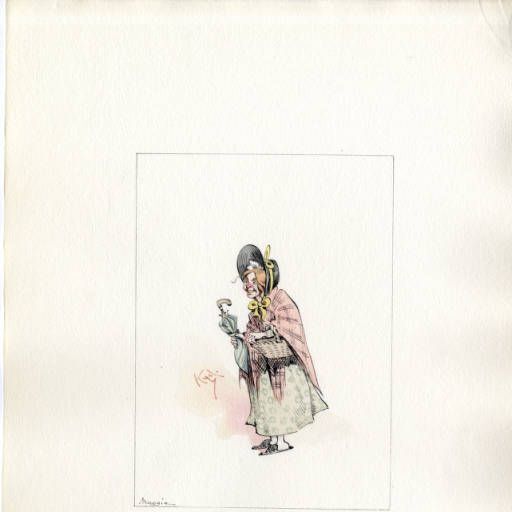

I also like Maggy. Perhaps Kim will post the remarkable Mahoney illustration of Little Dorrit and Maggy. It is a truly remarkable and evocative focus on the price of poverty and neglect.

Tristram

Ah, the race between Little Nell and Little Dorrit for your affections. I think Nell will always be my favourite. Perhaps that is because there is a major age difference between the two, perhaps because I see Nell as totally focussed on her grandfather who is a hopeless case. Little Dorrit does have some semblance of a private life and individual choice, but admittedly her father is an anchor around her neck.

I also like Maggy. Perhaps Kim will post the remarkable Mahoney illustration of Little Dorrit and Maggy. It is a truly remarkable and evocative focus on the price of poverty and neglect.

Tristram wrote: "When I was in the army, I once sprained my ankle during an endurance run, and the corporal sent me to the sickbay to get some treatment. On arriving there, they told me that I should have reported injured by 8 o' clock in the morning..."

Tristram wrote: "When I was in the army, I once sprained my ankle during an endurance run, and the corporal sent me to the sickbay to get some treatment. On arriving there, they told me that I should have reported injured by 8 o' clock in the morning..."I can top that. I spent a year arguing with a medical insurance company because my son had some emergency procedures done at birth and the administrator who filed the paperwork wrote down his birthdate a day late. So the insurance company rejected the claims on the grounds that my child had not been born yet at the time of the services. How they imagined he had undergone all those procedures without being born remains a mystery to me.

Tristram wrote: "When I was in the army, I once sprained my ankle during an endurance run, and the corporal sent me to the sickbay to get some treatment. On arriving there, they told me that I shou..."

That has to be one of the dumbest things I ever heard of. Until I read Julie's story that is, I think she topped it. Are there idiots everywhere? I thought I managed to keep most of them here in the valley.

That has to be one of the dumbest things I ever heard of. Until I read Julie's story that is, I think she topped it. Are there idiots everywhere? I thought I managed to keep most of them here in the valley.

Tristram wrote: "because the Barnacles stick to the Ship of State for all their lives’ worth. Kim might provide a picture of barnacles, since I have not mastered the art of inserting pictures yet."

Here you go:

Barnacles and limpets compete for space in the intertidal zone

Barnacles attached to the ventral pleats of a humpback whale calf

Goose barnacles, with their cirri extended for feeding

Gooseneck barnacles being enjoyed in a Spanish restaurant in Madrid

Here you go:

Barnacles and limpets compete for space in the intertidal zone

Barnacles attached to the ventral pleats of a humpback whale calf

Goose barnacles, with their cirri extended for feeding

Gooseneck barnacles being enjoyed in a Spanish restaurant in Madrid

Little Mother

Chapter 9, Book 1

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

They were come into the High Street, where the prison stood, when a voice cried, "Little mother, little mother!" Little Dorrit stopping and looking back, an excited figure of a strange kind bounced against them (still crying "little mother"), fell down, and scattered the contents of a large basket, filled with potatoes, in the mud.

"Oh, Maggy," said Little Dorrit, "what a clumsy child you are!"

Maggy was not hurt, but picked herself up immediately, and then began to pick up the potatoes, in which both Little Dorrit and Arthur Clennam helped. Maggy picked up very few potatoes and a great quantity of mud; but they were all recovered, and deposited in the basket. Maggy then smeared her muddy face with her shawl, and presenting it to Mr. Clennam as a type of purity, enabled him to see what she was like.

She was about eight-and-twenty, with large bones , large features, large feet and hands, large eyes and no hair. Her large eyes were limpid and almost colourless; they seemed to be very little affected by light, and to stand unnaturally still. There was also that attentive listening expression in her face, which is seen in the faces of the blind; but she was not blind, having one tolerably serviceable eye. Her face was not exceedingly ugly, though it was only redeemed from being so by a smile; a good-humoured smile, and pleasant in itself, but rendered pitiable by being constantly there. A great white cap, with a quantity of opaque frilling that was always flapping about, apologised for Maggy's baldness, and made it so very difficult for her old black bonnet to retain its place upon her head, that it held on round her neck like a gipsy's baby. A commission of haberdashers could alone have reported what the rest of her poor dress was made of, but it had a strong general resemblance to seaweed, with here and there a gigantic tea-leaf. Her shawl looked particularly like a tea-leaf after long infusion. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 9.

Commentary:

Maggy is another one of those peculiarly Dickensian characters with the mind of a child in the body of an adult, so that, by virtue of role reversal, Amy Dorrit is the "Little Mother" by virtue of her intellectual maturity, whereas the twenty-eight-year-old with the mental age of ten is the child. A similar role reversal occurs in Our Mutual Friend with Jenny Wren and Mr. Dolls, for Jenny must act as the sometimes-reproving parent to the alcoholic "child." Maggy's last name, although not given, is probably "Bangham," for her grandmother, Mrs. Bangham, is another inmate of the Marshalsea. Maggy's late mother was a prison nurse. Not a debtor herself, Maggy, like Frederick Dorrit, lives near rather than in the debtors' prison, and is free to come and go as a regular visitor, running errands for the inmates in order to support herself. Her development arrested by her illness, Maggy is the child-adult, permanently trapped in the oral stage of development, fixated on the gratification of appetite, and especially on "chicking."

In contrast to the diminutive but highly perceptive Little Dorrit, Maggy is a grotesque figure: gangly, bald, gigantic, and mentally retarded — almost androgynous, and certainly not "feminine." The diametrical opposite of Little Dorrit, Maggy is constantly hungry, both for food and for entertainment. Unlike the self-denying, angelic, and useful Little Dorrit, Maggy enjoys food — her fondest memory is of eating "chicking" when she was in hospital. Maggy’s fixation with food symbolizes that she is operating at the oral stage of development; she serves as Amy Dorritt's surrogate child as well as her companion.

(I would think Amy has enough "children" in her own family to take care of.)

He was a feeble, spare, and slow in his pinches as in everything else

Chapter 9, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

Arthur wondered what he could possibly want with the clarionet case. He did not want it at all. He discovered, in due time, that it was not the little paper of snuff (which was also on the chimney-piece), put it back again, took down the snuff instead, and solaced himself with a pinch. He was as feeble, spare, and slow in his pinches as in everything else, but a certain little trickling of enjoyment of them played in the poor worn nerves about the corners of his eyes and mouth.

"Amy, Mr. Clennam. What do you think of her?"

"I am much impressed, Mr. Dorrit, by all that I have seen of her and thought of her." — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 9.

Commentary:

The accompanying caption is somewhat different in the Harper and Bros. New York edition: In the back garret — a sickly room, with a turned up bedstead in it, so hastily and recently turned up that the blankets were boiling over, as it were, and keeping the lid open — a half finished breakfast of coffee and toast, for two persons, was jumbled down anyhow on a rickety table — Book 1, chap. ix. The Mahoney illustration departs from Phiz's original illustration for the chapter, in which Arthur Clennam and Amy encounter Maggy in the borough High Street near the prison after leaving William Dorrit's apartment, Little Mother in the third monthly part (February 1856).

Arthur Clennam interrogates the clarionet-player, Frederick Dorrit, in his rooms outside the Marshalsea about his niece, Amy, and her connection to Mrs. Clennam. Frederick explains that Amy serves an essential role for the Dorrits, the reasonable, caring parent — "We should all have been lost without Amy. She is a very good girl, Amy. She does her duty". The dinginess of the room suggests the slovenly lifestyle of the broken-down musician, and, indeed, Little Dorrit's origins. What is surprising, then, is that Amy herself is in no way tainted by the tawdry existence of the Dorrits.

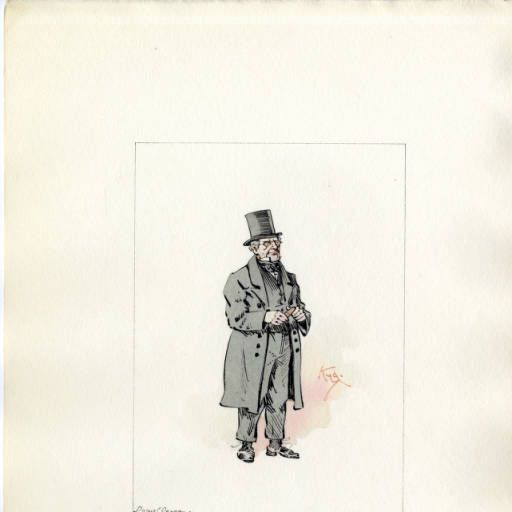

"Is it," said Barnacle, Junior, taking heed of his visitor's brown face, "Anything -about - tonnage?"

Chapter 10,Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

"But I say. Look here! Is this public business?" asked Barnacle junior.

(Click! Eye-glass down again. Barnacle Junior in that state of search after it that Mr. Clennam felt it useless to reply at present.)

"Is it," said Barnacle junior, taking heed of his visitor's brown face, "anything about — Tonnage — or that sort of thing?"

(Pausing for a reply, he opened his right eye with his hand, and stuck his glass in it, in that inflammatory manner that his eye began watering dreadfully.)

"No," said Arthur, "it is nothing about tonnage."

"Then look here. Is it private business?"

"I really am not sure. It relates to a Mr. Dorrit."

"Look here, I tell you what! You had better call at our house, if you are going that way. Twenty-four, Mews Street, Grosvenor Square. My father's got a slight touch of the gout, and is kept at home by it."

(The misguided young Barnacle evidently going blind on his eye-glass side, but ashamed to make any further alteration in his painful arrangements.)

"Thank you. I will call there now. Good morning." — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 10.

Commentary:

The term tonnage, about which Barnacle, Junior, affects to know little, is a nautical term denoting the volume or capacity of a mercantile ship, and therefore represents a more accurate picture of a nation's merchant marine than the mere number of registered vessels. For example, in the year 1857 the number of vessels that the various ports of the Great Britain in aggregate had registered (whether sailing vessels or steamships) was 27,097, but the tonnage or total storage capacity of those vessels amounted to some 4,558,740 tons. For example, the magnificent iron steam sailing ship S. S. Great Eastern, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel and at that point nearing completion on the Isle of Dogs, downriver from London, by far the largest vessel of her time, had a gross tonnage of 18,915. In contrast, the gross tonnage of the twenty-four vessels used to transport British troops in 1856 to the Crimea was 39,806. We may assume that the Circumlocution Office's oversight of British Trade meant that the term "tonnage" would have had considerably currency there, and that Barnacle, Junior, assumes that tanned, thirty-year-old Arthur Clennam is a businessman with interests in mercantile shipping. However, Clennam, in the midst of conducting an investigation of the case against William Dorrit, the Father of the Marshalsea. Clennam has been passed from official to another without finding a satisfactory answer. Here, moreover, Clennam meets another petitioner, the industrial inventor Daniel Doyce, who has been frustrated by the lack of cooperation of How-Not-To-Do-It Office.

In order to discover the nature of William Dorrit's debts and make arrangements to discharge them and effect the release of Amy's father, Clennam has to find out on which contract Dorrit defaulted. Barnacle, Junior, the functionary whom Clennam here consults in the Circumlocution Office, despite his inclination, at least reveals (on Clennam's second visit) which functionary and department he should consult in order to ascertain "the precise nature of the claim of the Crown against . . . William Dorrit":

"Well, I tell you what. Look here. You had better try the Secretarial Department," he said at last, sidling to the bell and ringing it. "Jenkinson," to the mashed potatoes messenger, "Mr. Wobbler!"

Another Kafkaesque runaround ensues, but eventually another young Barnacle elucidates Mr. Dorrit's case for Clennam, whose persistence will eventually result in William Dorrit's release:

"I suppose there was a failure in the performance of a contract, or something of that kind, was there?"

"I really don't know."

"Well! That you can find out. Then you'll find out what Department the contract was in, and then you'll find out all about it there."

"I beg your pardon. How shall I find out?"

"Why, you'll — you'll ask till they tell you. Then you'll memorialise that Department (according to regular forms which you'll find out) for leave to memorialise this Department. If you get it (which you may after a time), that memorial must be entered in that Department, sent to be registered in this Department, sent back to be signed by that Department, sent back to be countersigned by this Department, and then it will begin to be regularly before that Department. You'll find out when the business passes through each of these stages by asking at both Departments till they tell you."

"But surely this is not the way to do the business," Arthur Clennam could not help saying.

The large, overstuffed chair which occupies the center of the composition implies the owner of the comfortable, well-appointed office, Barnacle, Senior. The informing consciousness of the scene, Arthur Clennam, stands to the right, his face towards the bureaucrat rather than to the reader in this visual translation of the limited omniscient, and the whole focus of the scene is the elegantly attired, complacent, casually posed young aristocrat with the monocle. Only the large volumes on the mantelpiece, a large clock (only partially visible, upper left) and the overflowing wastebasket (right) suggest that this is an office as a roaring fire in the grate (to which the young Mr. Barnacle is standing rather close), thick, patterned carpets, and wallpaper with elaborately swirling designs proclaim comfort and affluence. Clennam's gesture with his hat implies that he is a petitioner, his topcoat and cane indicating that he has just come from outside.

(Thanks to this commentary I know what tonnage is, I wonder how long it will be until I forget it once again.)

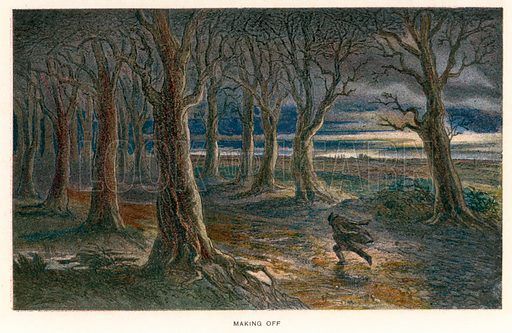

Making Off

Chapter 11, Book 1

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Shaken out of destiny's dice-box again into your company, eh? By Heaven! So much the better for you. You'll profit by it. I shall need a long rest. Let me sleep in the morning."

John Baptist replied that he should sleep as long as he would, and wishing him a happy night, put out the candle. One might have Supposed that the next proceeding of the Italian would have been to undress; but he did exactly the reverse, and dressed himself from head to foot, saving his shoes. When he had so done, he lay down upon his bed with some of its coverings over him, and his coat still tied round his neck, to get through the night.

When he started up, the Godfather Break of Day was peeping at its namesake. He rose, took his shoes in his hand, turned the key in the door with great caution, and crept downstairs. Nothing was astir there but the smell of coffee, wine, tobacco, and syrups; and madame's little counter looked ghastly enough. But he had paid madame his little note at it over night, and wanted to see nobody — wanted nothing but to get on his shoes and his knapsack, open the door, and run away.

He prospered in his object. No movement or voice was heard when he opened the door; no wicked head tied up in a ragged handkerchief looked out of the upper window. When the sun had raised his full disc above the flat line of the horizon, and was striking fire out of the long muddy vista of paved road with its weary avenue of little trees, a black speck moved along the road and splashed among the flaming pools of rain-water, which black speck was John Baptist Cavalletto running away from his patron. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 11.

Commentary:

In the original serial installment, the pair of monthly illustrations appeared before the text itself, rather than against the particular pages realised, so that, to the serial reader, the chapter title "Let Loose" must have seemed at first to be referring to Rigaud, the criminal released for lack of evidence of his having murdered his wife. Smuggled out of the region by authorities concerned about mob violence, Rigaud is bitter about "society's" treatment of him, and privately to his former cell-mate, Giovanni Battiste, vows that he will be avenged. At this point, the monthly illustration Making Off, as the reader must have realised, refers not to Rigaud, entering rural Burgundy from Provence, but the fearful Italian. Only the textual context, then, makes the plate, realizing the final page of Chapter 11, fully intelligible.

While The Birds in the Cage depends on emergence of detail from darkness, the scene of John Baptist's flight from Rigaud, "Making off" (Bk 1, ch. 11), uses an elaborate pattern of light and (dark, from the haze-covered rising sun on the horizon over the town and the faint glinimer of the puddles along the muddy road, to the ominous lines of trees which seem to march toward the vanishing point and into utter darkness. The figure of John Baptist, who flees from the oppressive association with Rigaud now that they are out of prison, recalls Lady Dedlock in The Lonely Figure, or the woman on the bridge in The Night.

The name of the river given in this passage at the beginning of the chapter, the Saone, gives the town its full name, "Chalon-sur-Saône" in Burgundy. Against the flat horizon in Mahoney's illustration for this chapter, One man slowly moving on towards Chalons was the only visible figure in the landscape, the traveller (identifiable by his nutcracker visage rather than his ragged clothing) can already see "Chalons" in the distance, as darkness is coming on — a suitably dramatic visual complement to the highly descriptive text. Phiz's approach in the original serial was quite different: in a dark plate intended to realize the last page of the chapter, a solitary figure is running from the right towards the tree lined avenue, left, with the village in the background. In this atmospheric scene, Phiz's focus is the apprehensions (as suggested by the looming avenue of leafless trees) of the other traveler, John Baptist Cavaletto, whose diminutive figure offers no particulars, but the general impression of haste.

John Baptist runs away from his patron

Chapter 11, Book 1

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

As he stretched out his length upon it, with a ragged handkerchief bound round his wicked head, and only his wicked head showing above the bedclothes, John Baptist was rather strongly reminded of what had so very nearly happened to prevent the moustache from any more going up as it did, and the nose from any more coming down as it did.

"Shaken out of destiny's dice-box again into your company, eh? By Heaven! So much the better for you. You'll profit by it. I shall need a long rest. Let me sleep in the morning."

John Baptist replied that he should sleep as long as he would, and wishing him a happy night, put out the candle. One might have supposed that the next proceeding of the Italian would have been to undress; but he did exactly the reverse, and dressed himself from head to foot, saving his shoes. When he had so done, he lay down upon his bed with some of its coverings over him, and his coat still tied round his neck, to get through the night.

When he started up, the Godfather Break of Day was peeping at its namesake. He rose, took his shoes in his hand, turned the key in the door with great caution, and crept downstairs. Nothing was astir there but the smell of coffee, wine, tobacco, and syrups; and madame's little counter looked ghastly enough. But he had paid madame his little note at it over night, and wanted to see nobody — wanted nothing but to get on his shoes and his knapsack, open the door, and run away. [Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 11]

Commentary:

Furniss's handling of this situation in the inn at Chalons is probably his direct response to the original serial illustration for this chapter by Phiz, Making Off, Part Three (February 1856). Although Rigaud has put a great deal of distance between himself and the prison at Marseilles, his evil reputation as the murderer of his wife has preceded him, as the landlady at the backstreet inn where Rigaud has taken refuge curses him as the Devil incarnate. Thus, Rigaud instructs his former cellmate, Giovanni Battiste Cavaletto ("John Baptist"), whom he meets by coincidence at Chalons, that henceforth he will be known as "Lagnier" — a nom-de-guerre made necessary by word of his crime and the "unproven" verdict having reached this part of France by the country's canal system. However, the alias is not the only aspect of their renewed relationship that the former Genoese smuggler finds disconcerting since "Monsieur Lagnier" has taken it into his head to treat John Baptist as his servant. Wisely, Cavaletto decides to make off as soon as possible, and escape from his "Patron" while he is still asleep at the Break of Day, rather than get caught up in another of Rigaud's confidence schemes. Furniss's John Baptist looks terrified at the prospect of awkening the vengeful Frenchman as he tries to make good his escape by turning the key in the lock, but the oblivious sleeper does not wake. And the snoring Rigaud, with his spiky hair, hand-bar moustache, and prominent nose seems suitably satanic.

Whereas Phiz in the original serial illustration for this chapter, Making Off focuses on the escaping John Baptist (the description of his flight from Chalons appears on the facing page, clarifying the identity of the figure fleeing along the tree-lined avenue) at the close of "Let Loose," James Mahoney in the Household Edition instead depicts the disgruntled, inwardly cursing traveller who by his nose, moustache, and nutcracker chin must be Rigaud, the former Marseilles prisoner. Both of Furniss's predecessors give the reader a sense of the French landscape, but Furniss instead sets the scene in the room at the Chalons backstreet inn, The Break of Day, to focus in close-up on the apprehensive Cavaletto in the very act of turning the key in the lock as Rigaud (now, "Lagnier") sleeps noisily in the foreground. Furniss makes the focal point of the composition the large, powerful right hand of the professional criminal, as if to suggest the very real danger the Italian faces if Rigaud feels his former cell-mate has betrayed him. The scene is animated by the contrasting expressions of the two figures, and by the kinetic sense of energy with which Furniss embues the entire composition.

One man slowly moving on towards Chalons was the only visible figure in the landscape.

Chapter 11, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

A late, dull autumn night was closing in upon the river Saone. The stream, like a sullied looking-glass in a gloomy place, reflected the clouds heavily; and the low banks leaned over here and there, as if they were half curious, and half afraid, to see their darkening pictures in the water. The flat expanse of country about Chalons lay a long heavy streak, occasionally made a little ragged by a row of poplar trees against the wrathful sunset. On the banks of the river Saone it was wet, depressing, solitary; and the night deepened fast.

One man slowly moving on towards Chalons was the only visible figure in the landscape. Cain might have looked as lonely and avoided. With an old sheepskin knapsack at his back, and a rough, unbarked stick cut out of some wood in his hand; miry, footsore, his shoes and gaiters trodden out, his hair and beard untrimmed; the cloak he carried over his shoulder, and the clothes he wore, sodden with wet; limping along in pain and difficulty; he looked as if the clouds were hurrying from him, as if the wail of the wind and the shuddering of the grass were directed against him, as if the low mysterious plashing of the water murmured at him, as if the fitful autumn night were disturbed by him. — Book the First, "Poverty.

Commentary:

The name of the river given in this passage at the beginning of the chapter, the Saone, gives the town in Burgundy its full name, "Chalon-sur-Saône." Against the flat horizon, the traveler can already see "Chalons" in the distance, as darkness and rain are coming on — a suitably dramatic visual complement to the highly descriptive text, and one which, appearing six pages ahead of the opening of Chapter 11, seems intended to generate an anticipatory set and a proleptic reading that only the reading of the text itself will clarify.

Whereas Hablot Knight Browne, Dickens's original illustrator, for this chapter, in Making Off, focusses on the escaping John Baptist (the description of his flight from Chalon appears on the facing page in the volume editions, clarifying the identity of the figure fleeing along the tree-lined avenue) at the close of "Let Loose," James Mahoney instead depicts the disgruntled, inwardly cursing traveler who by his nose, moustache, and nutcracker chin must be Rigaud, the former Marseilles prisoner.

In the illustration, Mahoney juxtaposes the lone traveler, left, with the distant city (upper right) and a tempestuous sky, a vigorous wind blowing the clouds and the trees on the horizon, immediately behind the walker. Agitated vegetation on the river bank completes the sense that nature itself is opposing Rigaud, complementing his assertion that the whole of French society seems to have turned against him.

Am I wrong that we have seen the Circumlocution Office before in Dickens? I have a feeling that it was in Bleak House but I could be wrong. I do remember falling asleep in one novel and I think it had to do with the long, long legal case in Bleak House so perhaps that is what I am thinking of. It has been awhile since I read that novel. When I saw Circumlocution Office in this I was sure I have seen it before and was expecting a long boring part but this was not as boring as I expected. Clue me in Tristram or Peter or someone.

Am I wrong that we have seen the Circumlocution Office before in Dickens? I have a feeling that it was in Bleak House but I could be wrong. I do remember falling asleep in one novel and I think it had to do with the long, long legal case in Bleak House so perhaps that is what I am thinking of. It has been awhile since I read that novel. When I saw Circumlocution Office in this I was sure I have seen it before and was expecting a long boring part but this was not as boring as I expected. Clue me in Tristram or Peter or someone. Also, here is I think our first coincidence of the novel, of Rigaud and Cavaletto being giving the same room in an inn. This is to be expected in a Dickens novel, of course. I was pleased to see that Cavaletto was smart enough to leave as soon as possible. I am interested to see if he is able to escape his old patron.

Bobbie wrote: "Am I wrong that we have seen the Circumlocution Office before in Dickens? I have a feeling that it was in Bleak House but I could be wrong. I do remember falling asleep in one novel and I think it ..."

Hi Bobbie

Your memory is just fine. In Bleak House there is a court case that has been going on seemingly for generations. Dickens carries the court case through the entire novel. It seems it will never be resolved. In Little Dorrit it seems that the Circumlocution Office may follow us throughout the entire novel and it will never help anyone who gets entangled in it.

So what we have in these two novels is a government institution in LD and a legal institution in BH both of whom seem to go nowhere and get nothing done. Both these institutions grind those who come into contact with them into small pieces. Both institutions serve themselves much more than serve the people who they should support and represent.

Hi Bobbie

Your memory is just fine. In Bleak House there is a court case that has been going on seemingly for generations. Dickens carries the court case through the entire novel. It seems it will never be resolved. In Little Dorrit it seems that the Circumlocution Office may follow us throughout the entire novel and it will never help anyone who gets entangled in it.

So what we have in these two novels is a government institution in LD and a legal institution in BH both of whom seem to go nowhere and get nothing done. Both these institutions grind those who come into contact with them into small pieces. Both institutions serve themselves much more than serve the people who they should support and represent.

For any who found the Circumlocution office bit boring to read, I'm going to recommend the Librivox reading of it. I was falling out laughing. I'm too lazy to download from Project Gutenberg but here is time stamp link to a YT version of it. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qv37o...

For any who found the Circumlocution office bit boring to read, I'm going to recommend the Librivox reading of it. I was falling out laughing. I'm too lazy to download from Project Gutenberg but here is time stamp link to a YT version of it. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qv37o...

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "When I was in the army, I once sprained my ankle during an endurance run, and the corporal sent me to the sickbay to get some treatment. On arriving there, they told me that I shou..."

You most certainly did top it. I hope it worked out all right for you in the end and you did not have to foot the bill all on your own?

You most certainly did top it. I hope it worked out all right for you in the end and you did not have to foot the bill all on your own?

Kim wrote: "That has to be one of the dumbest things I ever heard of."

By army standards, it wasn't too dumb a thing at all.

By army standards, it wasn't too dumb a thing at all.

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "because the Barnacles stick to the Ship of State for all their lives’ worth. Kim might provide a picture of barnacles, since I have not mastered the art of inserting pictures yet."..."

Yuck, how can they eat that?!

Yuck, how can they eat that?!

Bobbie wrote: "Am I wrong that we have seen the Circumlocution Office before in Dickens? I have a feeling that it was in Bleak House but I could be wrong. I do remember falling asleep in one novel and I think it ..."

Frankly speaking, the Circumlocution chapter did remind me of Bleak House, too, especially of the fact that Mr. Jarndyce always had to confer with the Chancery court before Richard Carstone could decide on a career. I always asked myself why the Lord Chancellor would have to give his okay to what a young man wants to do with his future, when other young men were free to choose as they liked. Then there were the uncountable bags of paper that were always carried into the courtroom whenever the case was on. There certainly are parallels.

Frankly speaking, the Circumlocution chapter did remind me of Bleak House, too, especially of the fact that Mr. Jarndyce always had to confer with the Chancery court before Richard Carstone could decide on a career. I always asked myself why the Lord Chancellor would have to give his okay to what a young man wants to do with his future, when other young men were free to choose as they liked. Then there were the uncountable bags of paper that were always carried into the courtroom whenever the case was on. There certainly are parallels.

The Circumlocution chapter certainly makes a point! Perhaps it's deliberate, to make it so long winded, that we get to feel the pain of the experience. Like people have said, times don't change.

The Circumlocution chapter certainly makes a point! Perhaps it's deliberate, to make it so long winded, that we get to feel the pain of the experience. Like people have said, times don't change.Given his audience of the day, I wonder what they would think of it? I imagine a father sat around the fire, in front of his children, reading this chapter to them with some unease, no doubt because of this own line of profession.

Avery wrote: "For any who found the Circumlocution office bit boring to read, I'm going to recommend the Librivox reading of it. I was falling out laughing. I'm too lazy to download from Project Gutenberg but he..."

Avery wrote: "For any who found the Circumlocution office bit boring to read, I'm going to recommend the Librivox reading of it. I was falling out laughing. I'm too lazy to download from Project Gutenberg but he..."I like that idea--thanks! I usually only do audiobooks if it's a book I've read before because unlike print books, audiobooks keep going when I get distracted, and I'm afraid I'll miss something. But I don't think it would be a problem if the Circumlocution Office just kept going.

Tristram wrote: "You most certainly did top it. I hope it worked out all right for you in the end and you did not have to foot the bill all on your own?."

Tristram wrote: "You most certainly did top it. I hope it worked out all right for you in the end and you did not have to foot the bill all on your own?."After a lot of offices, eventually we got there. It stopped short of Dickensian proportions!

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "because the Barnacles stick to the Ship of State for all their lives’ worth. Kim might provide a picture of barnacles, since I have not mastered the art of inserting pictures yet."..."

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "because the Barnacles stick to the Ship of State for all their lives’ worth. Kim might provide a picture of barnacles, since I have not mastered the art of inserting pictures yet."..."Those restaurant barnacles are kind of terrifying. Though I guess they come with an easy finger grip.