The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit

>

Little Dorrit, Book 2, Chp. 08-11

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

The following chapter is concerned with “Appearance and Disappearance”. First of all, we learn that Mr. and Mrs. Meagles are going to disappear for a while since they feel it better for them to join their daughter and her husband in Italy. Apparently Pet is pregnant, or I gathered as much from Mr. Meagles’s saying “Then again, here's Mother foolishly anxious (and yet naturally too) about Pet's state of health, and that she should not be left to feel lonesome at the present time. It's undeniably a long way off, Arthur, and a strange place for the poor love under all the circumstances.” Another reason for their going is their fear of being misrepresented in society by Mrs. Gowan (although I don’t understand how their going to Italy could change that), and then there are the debts run up by Mr. Gowan that need to be dealt with.

Arthur, who has become a kind of in-law to the Meagleses – as though, ghastly thought, he were married to the dead twin –, often walks up to their cottage in their absence, and one day, the cook Mrs. Tickit tells him, in a rather roundabout way, that she has seen Tattycoram linger near the house – the Appearance that has given this chapter its name, probably. Clennam is interested in this tale because he thinks that after all, the young girl can be persuaded to return to her old home, but at the same time, he has slight misgivings about Mrs. Tickit not having dreamt it all up. The matter might have hung in the balance for quite a while, if it were not for the novelist’s best friend: Miss Serendipity. This never-tiring damsel puts Clennam at the right place in the right moment:

”He was passing at nightfall along the Strand, and the lamp-lighter was going on before him, under whose hand the street-lamps, blurred by the foggy air, burst out one after another, like so many blazing sunflowers coming into full-blow all at once,—when a stoppage on the pavement, caused by a train of coal-waggons toiling up from the wharves at the river-side, brought him to a stand-still. He had been walking quickly, and going with some current of thought, and the sudden check given to both operations caused him to look freshly about him, as people under such circumstances usually do.

Immediately, he saw in advance—a few people intervening, but still so near to him that he could have touched them by stretching out his arm—Tattycoram and a strange man of a remarkable appearance: a swaggering man, with a high nose, and a black moustache as false in its colour as his eyes were false in their expression, who wore his heavy cloak with the air of a foreigner. His dress and general appearance were those of a man on travel, and he seemed to have very recently joined the girl. In bending down (being much taller than she was), listening to whatever she said to him, he looked over his shoulder with the suspicious glance of one who was not unused to be mistrustful that his footsteps might be dogged. It was then that Clennam saw his face; as his eyes lowered on the people behind him in the aggregate, without particularly resting upon Clennam's face or any other.”

We, of course, immediately know who the mysterious and unprepossessing stranger is. Clennam follows the girl and Blandois for a while, and finally they meet Miss Wade, who now seems to start some bargaining with Blandois, while Tattycoram loiters behind them. From the scratches Clennam can gather from their conversation, it is obvious that Blandois is reporting something to Miss Wade but that he wants some money first. Miss Wade angrily tells him that she has to get this money first, and after a while they separate. Clennam now follows Miss Wade and Tattycoram, who, to his wonderment, wend their way to Mr. Casby’s place and enter.

Clennam, after a while, also knocks at Casby’s door, and he is given a cordial welcome by Flora, who is sitting with Mr. F.’s Aunt, who is eating buttered slices of toast, leaving the crumbs for Flora. They talk about Little Dorrit and Italy for a while, with Mr. F.’s Aunt eying Arthur in a not too friendly way. Eventually, Clennam tells Flora the reason for his making this visit, and Flora agrees to go downstairs and ask her father for an interview. Clennam is left alone with Mr. F.’s Aunt, which provides another opportunity for great comedy, when this worthy old lady wants Clennam to eat the crumbs of her toast, and on finding that he declines this, says wonderful sentences like “He has a proud stomach, this chap!” and “Give him a meal of chaff!” Mr F.’s aunt is really my favourite character in this book!

Finally, Flora returns, and to his relief, Arthur is led into the presence of the Patriarch, who, all in all, is not more forthcoming than his portrait with regard to any valuable information concerning Miss Wade. He just says that from time to time, he has paid Miss Wade some money, but he denies any knowledge of her address. Luckily for Clennam, Mr. Pancks drops in, and when Clennam leaves and waits for a while outside (Mr. Pancks has signaled him to do this), Pancks gives him some more information on Miss Wade. He does not know her address, either, but he is pretty sure that his employer does and could get into contact with her if he were so inclined. He also says this about Miss Wade’s character:

” ‘I expect,’ rejoined that worthy, ‘I know as much about her as she knows about herself. She is somebody's child—anybody's, nobody's. Put her in a room in London here with any six people old enough to be her parents, and her parents may be there for anything she knows. They may be in any house she sees, they may be in any churchyard she passes, she may run against 'em in any street, she may make chance acquaintance of 'em at any time; and never know it. She knows nothing about 'em. She knows nothing about any relative whatever. Never did. Never will.’

‘Mr Casby could enlighten her, perhaps?’

‘May be,’ said Pancks. ‘I expect so, but don't know. He has long had money (not overmuch as I make out) in trust to dole out to her when she can't do without it. Sometimes she's proud and won't touch it for a length of time; sometimes she's so poor that she must have it. She writhes under her life. A woman more angry, passionate, reckless, and revengeful never lived. She came for money to-night. Said she had peculiar occasion for it.’

‘I think,’ observed Clennam musing, ‘I by chance know what occasion—I mean into whose pocket the money is to go.’

‘Indeed?’ said Pancks. ‘If it's a compact, I recommend that party to be exact in it. I wouldn't trust myself to that woman, young and handsome as she is, if I had wronged her; no, not for twice my proprietor's money! Unless,’ Pancks added as a saving clause, ‘I had a lingering illness on me, and wanted to get it over.’”

So Miss Wade is also an orphan like Tattycoram, a woman that does not know who her parents are and is utterly rootless in the world.

Mr. Pancks takes his leave of Arthur with a strange threat, namely that if Mr. Casby goes too far, he will one day cut his hair off.

Arthur, who has become a kind of in-law to the Meagleses – as though, ghastly thought, he were married to the dead twin –, often walks up to their cottage in their absence, and one day, the cook Mrs. Tickit tells him, in a rather roundabout way, that she has seen Tattycoram linger near the house – the Appearance that has given this chapter its name, probably. Clennam is interested in this tale because he thinks that after all, the young girl can be persuaded to return to her old home, but at the same time, he has slight misgivings about Mrs. Tickit not having dreamt it all up. The matter might have hung in the balance for quite a while, if it were not for the novelist’s best friend: Miss Serendipity. This never-tiring damsel puts Clennam at the right place in the right moment:

”He was passing at nightfall along the Strand, and the lamp-lighter was going on before him, under whose hand the street-lamps, blurred by the foggy air, burst out one after another, like so many blazing sunflowers coming into full-blow all at once,—when a stoppage on the pavement, caused by a train of coal-waggons toiling up from the wharves at the river-side, brought him to a stand-still. He had been walking quickly, and going with some current of thought, and the sudden check given to both operations caused him to look freshly about him, as people under such circumstances usually do.

Immediately, he saw in advance—a few people intervening, but still so near to him that he could have touched them by stretching out his arm—Tattycoram and a strange man of a remarkable appearance: a swaggering man, with a high nose, and a black moustache as false in its colour as his eyes were false in their expression, who wore his heavy cloak with the air of a foreigner. His dress and general appearance were those of a man on travel, and he seemed to have very recently joined the girl. In bending down (being much taller than she was), listening to whatever she said to him, he looked over his shoulder with the suspicious glance of one who was not unused to be mistrustful that his footsteps might be dogged. It was then that Clennam saw his face; as his eyes lowered on the people behind him in the aggregate, without particularly resting upon Clennam's face or any other.”

We, of course, immediately know who the mysterious and unprepossessing stranger is. Clennam follows the girl and Blandois for a while, and finally they meet Miss Wade, who now seems to start some bargaining with Blandois, while Tattycoram loiters behind them. From the scratches Clennam can gather from their conversation, it is obvious that Blandois is reporting something to Miss Wade but that he wants some money first. Miss Wade angrily tells him that she has to get this money first, and after a while they separate. Clennam now follows Miss Wade and Tattycoram, who, to his wonderment, wend their way to Mr. Casby’s place and enter.

Clennam, after a while, also knocks at Casby’s door, and he is given a cordial welcome by Flora, who is sitting with Mr. F.’s Aunt, who is eating buttered slices of toast, leaving the crumbs for Flora. They talk about Little Dorrit and Italy for a while, with Mr. F.’s Aunt eying Arthur in a not too friendly way. Eventually, Clennam tells Flora the reason for his making this visit, and Flora agrees to go downstairs and ask her father for an interview. Clennam is left alone with Mr. F.’s Aunt, which provides another opportunity for great comedy, when this worthy old lady wants Clennam to eat the crumbs of her toast, and on finding that he declines this, says wonderful sentences like “He has a proud stomach, this chap!” and “Give him a meal of chaff!” Mr F.’s aunt is really my favourite character in this book!

Finally, Flora returns, and to his relief, Arthur is led into the presence of the Patriarch, who, all in all, is not more forthcoming than his portrait with regard to any valuable information concerning Miss Wade. He just says that from time to time, he has paid Miss Wade some money, but he denies any knowledge of her address. Luckily for Clennam, Mr. Pancks drops in, and when Clennam leaves and waits for a while outside (Mr. Pancks has signaled him to do this), Pancks gives him some more information on Miss Wade. He does not know her address, either, but he is pretty sure that his employer does and could get into contact with her if he were so inclined. He also says this about Miss Wade’s character:

” ‘I expect,’ rejoined that worthy, ‘I know as much about her as she knows about herself. She is somebody's child—anybody's, nobody's. Put her in a room in London here with any six people old enough to be her parents, and her parents may be there for anything she knows. They may be in any house she sees, they may be in any churchyard she passes, she may run against 'em in any street, she may make chance acquaintance of 'em at any time; and never know it. She knows nothing about 'em. She knows nothing about any relative whatever. Never did. Never will.’

‘Mr Casby could enlighten her, perhaps?’

‘May be,’ said Pancks. ‘I expect so, but don't know. He has long had money (not overmuch as I make out) in trust to dole out to her when she can't do without it. Sometimes she's proud and won't touch it for a length of time; sometimes she's so poor that she must have it. She writhes under her life. A woman more angry, passionate, reckless, and revengeful never lived. She came for money to-night. Said she had peculiar occasion for it.’

‘I think,’ observed Clennam musing, ‘I by chance know what occasion—I mean into whose pocket the money is to go.’

‘Indeed?’ said Pancks. ‘If it's a compact, I recommend that party to be exact in it. I wouldn't trust myself to that woman, young and handsome as she is, if I had wronged her; no, not for twice my proprietor's money! Unless,’ Pancks added as a saving clause, ‘I had a lingering illness on me, and wanted to get it over.’”

So Miss Wade is also an orphan like Tattycoram, a woman that does not know who her parents are and is utterly rootless in the world.

Mr. Pancks takes his leave of Arthur with a strange threat, namely that if Mr. Casby goes too far, he will one day cut his hair off.

In Chapter 10 we see how “The Dreams of Mrs. Flintwinch Thicken”. One evening, after a longer absence from his mother’s house (due to Circumlocutionary Activities, or Non-Activities), Arthur decides to go and see his mother. When he arrives there, he sees waiting impatiently in front of the door the very man that had the nocturnal interview with Miss Wade. Clennam is very disgusted with the insolent behaviour Mr. Blandois shows in the presence of Flintwinch and later of Mrs. Clennam, and he ventures to utter his feelings.

Now although neither Mr. Flintwinch nor Mrs. Clennam betray any emotion in their faces, it is obvious that they somehow stand in awe of this strange visitor, who clings in a most disrespectful way to Flintwinch’s neck and pours down a torrent of familiarities upon him. Mrs. Clennam never for a moment takes her eyes off Blandois, as though he were some dangerous animal, and at the same time, Flintwinch keeps an eye on Clennam. Instead of taking her son’s side against the impertinent Blandois, Mrs. Clennam rebukes Arthur for insulting their guest, who – as she says – has struck up some sort of friendship with her partner Mr. Flintwinch.

It is obvious, though, that Blandois knows something to Mrs. Clennam’s disadvantage, and that he is enjoying his newly-won position of power, as the following extract might show:

”’The gentleman,’ pursued Mrs Clennam, ‘on a former occasion brought a letter of recommendation to us from highly esteemed and responsible correspondents. I am perfectly unacquainted with the gentleman's object in coming here at present. I am entirely ignorant of it, and cannot be supposed likely to be able to form the remotest guess at its nature;’ her habitual frown became stronger, as she very slowly and weightily emphasised those words; ‘but, when the gentleman proceeds to explain his object, as I shall beg him to have the goodness to do to myself and Flintwinch, when Flintwinch returns, it will prove, no doubt, to be one more or less in the usual way of our business, which it will be both our business and our pleasure to advance. It can be nothing else.’

‘We shall see, madame!’ said the man of business.”

Then, in a very gruff way, she asks her son to leave them alone for they intend to talk business with their guest. Arthur has now no choice but to leave, and outside the door, he finds good old Affery, distraught with fright, and her apron above her head. When he asks her what is going on, she says,

”’Don't ask me anything, Arthur. I've been in a dream for ever so long. Go away!‘“

Now although neither Mr. Flintwinch nor Mrs. Clennam betray any emotion in their faces, it is obvious that they somehow stand in awe of this strange visitor, who clings in a most disrespectful way to Flintwinch’s neck and pours down a torrent of familiarities upon him. Mrs. Clennam never for a moment takes her eyes off Blandois, as though he were some dangerous animal, and at the same time, Flintwinch keeps an eye on Clennam. Instead of taking her son’s side against the impertinent Blandois, Mrs. Clennam rebukes Arthur for insulting their guest, who – as she says – has struck up some sort of friendship with her partner Mr. Flintwinch.

It is obvious, though, that Blandois knows something to Mrs. Clennam’s disadvantage, and that he is enjoying his newly-won position of power, as the following extract might show:

”’The gentleman,’ pursued Mrs Clennam, ‘on a former occasion brought a letter of recommendation to us from highly esteemed and responsible correspondents. I am perfectly unacquainted with the gentleman's object in coming here at present. I am entirely ignorant of it, and cannot be supposed likely to be able to form the remotest guess at its nature;’ her habitual frown became stronger, as she very slowly and weightily emphasised those words; ‘but, when the gentleman proceeds to explain his object, as I shall beg him to have the goodness to do to myself and Flintwinch, when Flintwinch returns, it will prove, no doubt, to be one more or less in the usual way of our business, which it will be both our business and our pleasure to advance. It can be nothing else.’

‘We shall see, madame!’ said the man of business.”

Then, in a very gruff way, she asks her son to leave them alone for they intend to talk business with their guest. Arthur has now no choice but to leave, and outside the door, he finds good old Affery, distraught with fright, and her apron above her head. When he asks her what is going on, she says,

”’Don't ask me anything, Arthur. I've been in a dream for ever so long. Go away!‘“

This week’s final chapter gives us “A Letter from Little Dorrit” again, this time from Rome. Amy tells Arthur more about the Gowans, for example about their comparatively miserable lodging. I was wondering how a painter could work in a room that is not sufficiently bright, but then I am not a painter, and maybe many a painter can work in these circumstances.

Here’s an extract from the letter dwelling on Mr. Gowan’s strange relationship to his wife and his in-laws:

”Owing (as I think, if you think so too) to Mr Gowan's unsettled and dissatisfied way, he applies himself to his profession very little. He does nothing steadily or patiently; but equally takes things up and throws them down, and does them, or leaves them undone, without caring about them. When I have heard him talking to Papa during the sittings for the picture, I have sat wondering whether it could be that he has no belief in anybody else, because he has no belief in himself. Is it so? I wonder what you will say when you come to this! I know how you will look, and I can almost hear the voice in which you would tell me on the Iron Bridge.

Mr Gowan goes out a good deal among what is considered the best company here—though he does not look as if he enjoyed it or liked it when he is with it—and she sometimes accompanies him, but lately she has gone out very little. I think I have noticed that they have an inconsistent way of speaking about her, as if she had made some great self-interested success in marrying Mr Gowan, though, at the same time, the very same people, would not have dreamed of taking him for themselves or their daughters. Then he goes into the country besides, to think about making sketches; and in all places where there are visitors, he has a large acquaintance and is very well known. Besides all this, he has a friend who is much in his society both at home and away from home, though he treats this friend very coolly and is very uncertain in his behaviour to him. I am quite sure (because she has told me so), that she does not like this friend. He is so revolting to me, too, that his being away from here, at present, is quite a relief to my mind. How much more to hers!

But what I particularly want you to know, and why I have resolved to tell you so much while I am afraid it may make you a little uncomfortable without occasion, is this. She is so true and so devoted, and knows so completely that all her love and duty are his for ever, that you may be certain she will love him, admire him, praise him, and conceal all his faults, until she dies. I believe she conceals them, and always will conceal them, even from herself. She has given him a heart that can never be taken back; and however much he may try it, he will never wear out its affection. You know the truth of this, as you know everything, far far better than I; but I cannot help telling you what a nature she shows, and that you can never think too well of her.

[…]

Perhaps you have not heard from her father or mother yet, and may not know that she has a baby son. He was born only two days ago, and just a week after they came. It has made them very happy. However, I must tell you, as I am to tell you all, that I fancy they are under a constraint with Mr Gowan, and that they feel as if his mocking way with them was sometimes a slight given to their love for her. It was but yesterday, when I was there, that I saw Mr Meagles change colour, and get up and go out, as if he was afraid that he might say so, unless he prevented himself by that means. Yet I am sure they are both so considerate, good-humoured, and reasonable, that he might spare them. It is hard in him not to think of them a little more.”

We also learn that Amy and Pet have become friends, and that Pet refers to Amy by the name that is so dear to her since Arthur first applied it to her – Little Dorrit.

There are further references about Mr. Gowan’s listlessly working on Mr. Dorrit’s portrait and on Fanny’s doing very well – we can imagine – with her suitor, and the letter ends in a very melancholy way:

”Heaven knows when your poor child will see England again. We are all fond of the life here (except me), and there are no plans for our return. My dear father talks of a visit to London late in this next spring, on some affairs connected with the property, but I have no hope that he will bring me with him.

I have tried to get on a little better under Mrs General's instruction, and I hope I am not quite so dull as I used to be. I have begun to speak and understand, almost easily, the hard languages I told you about. I did not remember, at the moment when I wrote last, that you knew them both; but I remembered it afterwards, and it helped me on. God bless you, dear Mr Clennam. Do not forget

Your ever grateful and affectionate

Little Dorrit”

Here’s an extract from the letter dwelling on Mr. Gowan’s strange relationship to his wife and his in-laws:

”Owing (as I think, if you think so too) to Mr Gowan's unsettled and dissatisfied way, he applies himself to his profession very little. He does nothing steadily or patiently; but equally takes things up and throws them down, and does them, or leaves them undone, without caring about them. When I have heard him talking to Papa during the sittings for the picture, I have sat wondering whether it could be that he has no belief in anybody else, because he has no belief in himself. Is it so? I wonder what you will say when you come to this! I know how you will look, and I can almost hear the voice in which you would tell me on the Iron Bridge.

Mr Gowan goes out a good deal among what is considered the best company here—though he does not look as if he enjoyed it or liked it when he is with it—and she sometimes accompanies him, but lately she has gone out very little. I think I have noticed that they have an inconsistent way of speaking about her, as if she had made some great self-interested success in marrying Mr Gowan, though, at the same time, the very same people, would not have dreamed of taking him for themselves or their daughters. Then he goes into the country besides, to think about making sketches; and in all places where there are visitors, he has a large acquaintance and is very well known. Besides all this, he has a friend who is much in his society both at home and away from home, though he treats this friend very coolly and is very uncertain in his behaviour to him. I am quite sure (because she has told me so), that she does not like this friend. He is so revolting to me, too, that his being away from here, at present, is quite a relief to my mind. How much more to hers!

But what I particularly want you to know, and why I have resolved to tell you so much while I am afraid it may make you a little uncomfortable without occasion, is this. She is so true and so devoted, and knows so completely that all her love and duty are his for ever, that you may be certain she will love him, admire him, praise him, and conceal all his faults, until she dies. I believe she conceals them, and always will conceal them, even from herself. She has given him a heart that can never be taken back; and however much he may try it, he will never wear out its affection. You know the truth of this, as you know everything, far far better than I; but I cannot help telling you what a nature she shows, and that you can never think too well of her.

[…]

Perhaps you have not heard from her father or mother yet, and may not know that she has a baby son. He was born only two days ago, and just a week after they came. It has made them very happy. However, I must tell you, as I am to tell you all, that I fancy they are under a constraint with Mr Gowan, and that they feel as if his mocking way with them was sometimes a slight given to their love for her. It was but yesterday, when I was there, that I saw Mr Meagles change colour, and get up and go out, as if he was afraid that he might say so, unless he prevented himself by that means. Yet I am sure they are both so considerate, good-humoured, and reasonable, that he might spare them. It is hard in him not to think of them a little more.”

We also learn that Amy and Pet have become friends, and that Pet refers to Amy by the name that is so dear to her since Arthur first applied it to her – Little Dorrit.

There are further references about Mr. Gowan’s listlessly working on Mr. Dorrit’s portrait and on Fanny’s doing very well – we can imagine – with her suitor, and the letter ends in a very melancholy way:

”Heaven knows when your poor child will see England again. We are all fond of the life here (except me), and there are no plans for our return. My dear father talks of a visit to London late in this next spring, on some affairs connected with the property, but I have no hope that he will bring me with him.

I have tried to get on a little better under Mrs General's instruction, and I hope I am not quite so dull as I used to be. I have begun to speak and understand, almost easily, the hard languages I told you about. I did not remember, at the moment when I wrote last, that you knew them both; but I remembered it afterwards, and it helped me on. God bless you, dear Mr Clennam. Do not forget

Your ever grateful and affectionate

Little Dorrit”

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 8..."

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 8..."Was anyone else surprised at the lack of fanfare when MiniPet's pregnancy was mentioned? (I almost said revealed, but that word implies more joyous anticipation.) I suppose the assumption in Victorian society was that babies naturally followed marriage in rather quick succession as a matter of course. Still, my 21st century mentality expected, perhaps, a letter from Pet, sharing her elation at the happy news. But perhaps that's the rub. This baby cements what everyone - including Pet, herself by this time - knows is an unhappy union.

Tristram wrote: "Mr. Pancks takes his leave of Arthur with a strange threat, namely that if Mr. Casby goes too far, he will one day cut his hair off...."

Tristram wrote: "Mr. Pancks takes his leave of Arthur with a strange threat, namely that if Mr. Casby goes too far, he will one day cut his hair off...."Do I detect some foreshadowing here? Perhaps Casby, like Samson, will lose his strength and power when his hair is cut. Though I have trouble picturing Pancks as a would-be Delilah. How would Casby's losing his power impact the other characters and the story as a whole, I wonder? Perhaps he's more intricately involved in the plot than we know just yet.

Tristram wrote: "he finds good old Affery, distraught with fright, and her apron above her head...."

Tristram wrote: "he finds good old Affery, distraught with fright, and her apron above her head...."I'm going to resurrect some of my mom's old aprons. I quite like the idea of throwing my apron over my head in those moments when the world is just too scary to face.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "he finds good old Affery, distraught with fright, and her apron above her head...."

I'm going to resurrect some of my mom's old aprons. I quite like the idea of throwing my apron ..."

Mary Lou

Good idea. I’ll try it too.

I'm going to resurrect some of my mom's old aprons. I quite like the idea of throwing my apron ..."

Mary Lou

Good idea. I’ll try it too.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

Let us now move from morbid old Venice to … morbid old London – it seems that there is now no end to morbidity in this novel although there are also some pleasant developments on..."

This chapter occasioned two distinct responses from me. First, I have an increasing dislike for all people named Gowan. Both mother and son are self-centred and have more ego than any sensitivity for anyone other than themselves. Will they get their just desserts before the end of the novel?

Balancing my dislike to all people named Gowan comes my increasing respect for Doyce. His invention appears to be something that will greatly benefit society. Sadly the Circumlocution office, tasked to act in the interests of England, do the opposite. Their only actions are designed to preserve inertia.

Let us now move from morbid old Venice to … morbid old London – it seems that there is now no end to morbidity in this novel although there are also some pleasant developments on..."

This chapter occasioned two distinct responses from me. First, I have an increasing dislike for all people named Gowan. Both mother and son are self-centred and have more ego than any sensitivity for anyone other than themselves. Will they get their just desserts before the end of the novel?

Balancing my dislike to all people named Gowan comes my increasing respect for Doyce. His invention appears to be something that will greatly benefit society. Sadly the Circumlocution office, tasked to act in the interests of England, do the opposite. Their only actions are designed to preserve inertia.

Tristram wrote: "The following chapter is concerned with “Appearance and Disappearance”. First of all, we learn that Mr. and Mrs. Meagles are going to disappear for a while since they feel it better for them to joi..."

OK. Let’s have a look at all the players in this chapter. Casby, Miss Wade, Tattycoram, Blandois. This is quite the lineup of characters who dwell on the shadowy side of the street. Miss Wade and Blandois and money. Now there’s a toxic and mysterious combination.

There is much to be concerned about.

OK. Let’s have a look at all the players in this chapter. Casby, Miss Wade, Tattycoram, Blandois. This is quite the lineup of characters who dwell on the shadowy side of the street. Miss Wade and Blandois and money. Now there’s a toxic and mysterious combination.

There is much to be concerned about.

Oh please call the awful mother-in-law Granny Gowen, I want to see the look on her face when she hears it. I wonder how she feels about being a grandmother anyway. And since the mother is so inferior to the father, does that make the baby inferior too? I can't stand most of these people.

Why are we following Tattycoram anyway? She was the companion/maid or whatever she was to MiniPet, then she quit and went with the evil Miss Wade. What is the big mystery in this? I see no reason to follow her just because you saw her walking down the street in front of you, I run into people I once knew often, I have never felt the urge to follow them.

Kim wrote: "Why are we following Tattycoram anyway? She was the companion/maid or whatever she was to MiniPet, then she quit and went with the evil Miss Wade. What is the big mystery in this? I see no reason t..."

I think, in part, Tattycoram deserves our attention because she has worn both a “good” hat (although she is not Pet’s main supporter) and a bad hat with her attachment to Miss Wade. Few female characters are presented to us by Dickens who change their loyalty or show a major character change in such a short time. Nancy, from OT is an exception.

So, to me, the big question is what side of the fence will Tattycoram end up on and, equally important, why?

I think, in part, Tattycoram deserves our attention because she has worn both a “good” hat (although she is not Pet’s main supporter) and a bad hat with her attachment to Miss Wade. Few female characters are presented to us by Dickens who change their loyalty or show a major character change in such a short time. Nancy, from OT is an exception.

So, to me, the big question is what side of the fence will Tattycoram end up on and, equally important, why?

Kim wrote: "Why are we following Tattycoram anyway? She was the companion/maid or whatever she was to MiniPet, then she quit and went with the evil Miss Wade. What is the big mystery in this? I see no reason t..."

Kim wrote: "Why are we following Tattycoram anyway? She was the companion/maid or whatever she was to MiniPet, then she quit and went with the evil Miss Wade. What is the big mystery in this? I see no reason t..."I honestly think its a bit of good-natured paternalism? The Meagles 'adopted' her and care for her, even if their perspective on the subsequent treatment isn't like our modern one. Good intentions and hell and so on...And Mr. Clenman is also a nosy, interfering paternalistic do-gooder with strong ties to the Meagles. I'm not surprised he followed her, character wise, even if it is also a blatant plot device by Mr. Dickens.

I have two stong responses to these chapters.

I have two stong responses to these chapters. That the dowager Mrs. Gowan is a character that leads me to understand how people get into physical altercations. I find my self wondering if there is anyway to attach an image of her face to a mass of enemies in my favorite video game, and just comment unspeakably violent atrocities upon her.

Granny Gowan is a problem and I don't blame the Meagles for deciding to leave town. It might not prevent her from bad mouthing them around town, but getting ahead in society was never a priority for them. This way they do not have to be around as the rumor mill turns. I do worry that her insinuations about Mr. Meagles dealings could hurt their business interests, and ultimately cause the inheritance (that Society's bosom already is aware is a win for the Gowans) to be affected? Its seems that the social machinations she is engaging in could come back to harm her. Short-sighted?

Secondly, I don't' understand how Mrs. Flintwinch manages to walk around with her apron over her head? I'm wondering if Victorian aprons were of a different construction to the modern one I wear. The image is amusing but also so unrealistic from the perspective a person who wears an apron almost everyday that I just cant get past it!

To me, Affery is one of Dickens’s delightfully quirky minor characters. Her apron-over-the-head antics are very visual and thus the original readers of the novel could well imagine her in such a pose. Like modern sketch comedy, I can imagine the audience actually expecting she would cover her head. In some ways, perhaps, her apron could be seen as the equivalent to more modern equivalent of the banana peel on the floor. We just know someone will slip on the banana. We just wait in delightful anticipation.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 8..."

Was anyone else surprised at the lack of fanfare when MiniPet's pregnancy was mentioned? (I almost said revealed, but that word implies more joyous anticipation.) I ..."

I had the impression that the only people who really cared about the new-born babe were the Meagleses - or maybe, they cared more about their daughter's health and well-being, and that is why they undertook the trip to Italy. I am sure, though, that seeing the baby will have made them love him.

But on the whole you are right: Nobody really seems to be very happy - at least, Little Dorrit's letter only offers sparse information on this subject.

Was anyone else surprised at the lack of fanfare when MiniPet's pregnancy was mentioned? (I almost said revealed, but that word implies more joyous anticipation.) I ..."

I had the impression that the only people who really cared about the new-born babe were the Meagleses - or maybe, they cared more about their daughter's health and well-being, and that is why they undertook the trip to Italy. I am sure, though, that seeing the baby will have made them love him.

But on the whole you are right: Nobody really seems to be very happy - at least, Little Dorrit's letter only offers sparse information on this subject.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "he finds good old Affery, distraught with fright, and her apron above her head...."

I'm going to resurrect some of my mom's old aprons. I quite like the idea of throwing my apron ..."

I'd have worn my first apron out by now. - It is quite a strange reaction, this apron thing of Affery's but it shows her helplessness in a household where everyone regards her as a piece of furniture to shove and push at their free will.

I'm going to resurrect some of my mom's old aprons. I quite like the idea of throwing my apron ..."

I'd have worn my first apron out by now. - It is quite a strange reaction, this apron thing of Affery's but it shows her helplessness in a household where everyone regards her as a piece of furniture to shove and push at their free will.

Kim wrote: "Oh please call the awful mother-in-law Granny Gowen, I want to see the look on her face when she hears it. I wonder how she feels about being a grandmother anyway. And since the mother is so inferi..."

The name Gowan

Makes me frow-an.

The name of Dorrit

Has not much forrit.

The name of Clennam

To me is venom.

But there is Flora,

I quit ador-a

And also Doyce

Is of my choice.

That's things in a nutshell for me. I was really annoyed, by the way, that Arthur only seems to want to visit Flora when he has some sort of ulterior motive in the back of his head. His impatience when talking to Flora was quite insulting and ruthless - it was clear he only wanted to get it all over with and learn more about Miss Wade.

The name Gowan

Makes me frow-an.

The name of Dorrit

Has not much forrit.

The name of Clennam

To me is venom.

But there is Flora,

I quit ador-a

And also Doyce

Is of my choice.

That's things in a nutshell for me. I was really annoyed, by the way, that Arthur only seems to want to visit Flora when he has some sort of ulterior motive in the back of his head. His impatience when talking to Flora was quite insulting and ruthless - it was clear he only wanted to get it all over with and learn more about Miss Wade.

Kim wrote: "Why are we following Tattycoram anyway? She was the companion/maid or whatever she was to MiniPet, then she quit and went with the evil Miss Wade. What is the big mystery in this? I see no reason t..."

I think Arthur follows Tattycoram because he feels that the Meagles are getting more and more lonely and that they miss Tattycoram and perhaps want to "giver her another chance", as they would put it. It is his interest in the Meagles family that makes him feel interested in Tattycoram. And maybe, he is also somewhat fascinated - in a negative way - by Miss Wade - who knows? Remember that she seemed to be well-informed about MiniPet's being courted by Gowan and about her impending marriage. Arthur's interest in MiniPet might have kindled his interest in Miss Wade and the sources of her knowledge?

I think Arthur follows Tattycoram because he feels that the Meagles are getting more and more lonely and that they miss Tattycoram and perhaps want to "giver her another chance", as they would put it. It is his interest in the Meagles family that makes him feel interested in Tattycoram. And maybe, he is also somewhat fascinated - in a negative way - by Miss Wade - who knows? Remember that she seemed to be well-informed about MiniPet's being courted by Gowan and about her impending marriage. Arthur's interest in MiniPet might have kindled his interest in Miss Wade and the sources of her knowledge?

Peter wrote: "So, to me, the big question is what side of the fence will Tattycoram end up on and, equally important, why?"

Good questions, Peter. I was thinking about Tattycoram's conflict, her submission to Miss Wade and her anger with the Meagles, too, and came up with the question why she should end up on either side of the fence at all. I guess that Dickens does not have this solution in store (maybe not even the question begging it) but even though Miss Wade may prove harmful to Tatty, that does not necessarily justify the Meagleses' attitude to and treatment of the girl, does it? Maybe, Tattycoram will realize this and search for a new opening in life?

Good questions, Peter. I was thinking about Tattycoram's conflict, her submission to Miss Wade and her anger with the Meagles, too, and came up with the question why she should end up on either side of the fence at all. I guess that Dickens does not have this solution in store (maybe not even the question begging it) but even though Miss Wade may prove harmful to Tatty, that does not necessarily justify the Meagleses' attitude to and treatment of the girl, does it? Maybe, Tattycoram will realize this and search for a new opening in life?

Avery wrote: "Kim wrote: "Why are we following Tattycoram anyway? She was the companion/maid or whatever she was to MiniPet, then she quit and went with the evil Miss Wade. What is the big mystery in this? I see..."

Sorry I hadn't read your remarks before I posted my response to Kim. You are expressing it all a lot better, also in terms of plot devices!

Sorry I hadn't read your remarks before I posted my response to Kim. You are expressing it all a lot better, also in terms of plot devices!

If I recall, Casby asked what his interest in Miss Wade was, and Arthur, after learning Tattycoram had been lurking around the Meagles' house, told him that he wanted to be sure Tattycoram knew she would still be welcomed back into the fold.

If I recall, Casby asked what his interest in Miss Wade was, and Arthur, after learning Tattycoram had been lurking around the Meagles' house, told him that he wanted to be sure Tattycoram knew she would still be welcomed back into the fold. By the way, Tristram, your poem was a thing of beauty, rivaling Ode to an Expiring Frog.

Tristram wrote : The name Gowan

Makes me frow-an.

The name of Dorrit

Has not much forrit.

Who wrote that for you, your son or your daughter? I'd add your wife to the list but she doesn't know English.

Makes me frow-an.

The name of Dorrit

Has not much forrit.

Who wrote that for you, your son or your daughter? I'd add your wife to the list but she doesn't know English.

Rigour of Mr. F's Aunt

Chapter 9, Book 2

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"None of your eyes at me," said Mr F.'s Aunt, shivering with hostility. "Take that."

"That" was the crust of the piece of toast. Clennam accepted the boon with a look of gratitude, and held it in his hand under the pressure of a little embarrassment, which was not relieved when Mr. F.'s Aunt, elevating her voice into a cry of considerable power, exclaimed, "He has a proud stomach, this chap! He's too proud a chap to eat it!" and, coming out of her chair, shook her venerable fist so very close to his nose as to tickle the surface. But for the timely return of Flora, to find him in this difficult situation, further consequences might have ensued. Flora, without the least discomposure or surprise, but congratulating the old lady in an approving manner on being "very lively to-night," handed her back to her chair.

"He has a proud stomach, this chap," said Mr F.'s relation, on being reseated. "Give him a meal of chaff!"

"Oh! I don't think he would like that, aunt," returned Flora.

"Give him a meal of chaff, I tell you," said Mr. F.'s Aunt, glaring round Flora on her enemy. "It’s the only thing for a proud stomach. Let him eat up every morsel. Drat him, give him a meal of chaff!"

Under a general pretence of helping him to this refreshment, Flora got him out on the staircase; Mr. F.'s Aunt even then constantly reiterating, with inexpressible bitterness, that he was "a chap," and had a "proud stomach," and over and over again insisting on that equine provision being made for him which she had already so strongly prescribed.

"Such an inconvenient staircase and so many corner-stairs Arthur," whispered Flora, "would you object to putting your arm round me under my pelerine?"

With a sense of going down-stairs in a highly-ridiculous manner, Clennam descended in the required attitude, and only released his fair burden at the dining-room door; indeed, even there she was rather difficult to be got rid of, remaining in his embrace to murmur, "Arthur, for mercy's sake, don’t breathe it to papa!"

She accompanied Arthur into the room, where the Patriarch sat alone, with his list shoes on the fender, twirling his thumbs as if he had never left off. The youthful Patriarch, aged ten, looked out of his picture-frame above him with no calmer air than he. Both smooth heads were alike beaming, blundering, and bumpy.

"Mr. Clennam, I am glad to see you. I hope you are well, sir, I hope you are well. Please to sit down, please to sit down." — Book the Second, "Riches"; Chapter 9, "Appearance and Disappearance".

Commentary:

This situation in the Patriarchal madhouse is utterly baffling for a reader who merely "drops into" the pages of text involved — in any event, whereas Phiz's pair of illustrations appeared at the front of installment thirteen (and in the volume very near this comic dialogue), the others are not so well situated that the reader construes the angry blathering of Mr. F.'s Aunt in the context of Chapter 9, in which Arthur Clennam, having followed Miss Wade and Tattycoram to the "Patriarchal mansion" of Mr. Casby, encounters the demented aunt by marriage who fears losing her devoted nurse and companion — in other words, her apparently irrational diatribe against Clennam, underscored in the original Phiz illustration, is clearly motivated and, in its own way, an understandable response to a potential threat, although the reader may not interpret the bizarre behaviour of Mr. F's aunt in such a light upon first reading this scene. However, even the unreflective reader would likely regard the tea-time confrontation as epitomizing so much of the book as normative characters such as Arthur Clennam and Amy Dorrit (Austenian True Wits) encounter a metropolis teaming with False Wits in a Comedy of Manners translated from the stage to the novel.

The illustrator's description of yet another pallid Dickens hero, Arthur, is all the more effective for his being juxtaposed against such a singularly odd and barely comprehensible a character as Mr. F.'s Aunt, whom the illustrators Eytinge, Phiz, Mahoney, and Furniss have costumed not as in her dotage, but as a perfectly respectable middle class matron of advanced years, complete with oversized hat and large linen napkin. Although none of the illustrations of this scene makes the situation completely clear, Mrs. F.'s Aunt has just thrust a piece of toast into Arthur's hand and is demanding that he finish for her, just as Flora would, were she present. With his nice sense of comic timing, Phiz has an oblivious Flora about to intervene, so that the viewer of the Phiz illustration is compelled to revert to the text to learn how she will handle this extremely awkward situation so that she mollifies her aunt-by-marriage, without driving a potential suitor away. Arthur, apparently a young, respectably dressed bourgeois, reacts with mild shock and surprise to the elderly lady's aggressive behaviour, which is clearly intended to drive the rival for Flora's affections out of the house, never to visit middle-aged Flora again. Critic J. A. Hammerton imposed beneath the Phiz engraving reproduced in The Dickens Picture-Book (1910) the caption "Flora found him in this difficult situation" to alert the reader to Flora's impending dilemma.

Contemporary American illustrator Sol Eytinge, Junior, following Phiz's lead, depicted Flora Finching as vacuous and Mr. F's Aunt as senile, but pliable in the 1867 Diamond Edition wood-engraving Flora and Mr. F's Aunt — a dual character study that, like the 1863 frontispiece by Sir John Gilbert, is based on Phiz's steel-engraving for Part 13 (December 1856) illustration. The social realist James Mahoney in the Household Edition's fifty-eight illustrations does not include this scene, choosing instead to realize Clennam's shadowing Miss Wade and Tattycoram in "He stopped at the corner stopped at the corner, seeming to look back expectantly up the street as if he had made an appointment with some one to meet him there; but he kept a careful eye on the three. When they came together, the man took off his hat, and made Miss Wade a bow — Book 2, chap. 9. Mahoney's treatment of Flora in "What nimble fingers you have," said Flora, "but are you sure you are well?". . . "Oh yes, indeed!" Flora put her feet upon the fender, and settled herself for a thorough good romantic disclosure. — Book 1, chap. 24. The illustrator betrays little sympathy for the querulous, old woman in the Furniss illustrations for the twelfth volume of The Charles Dickens Library Edition, Mr. F's Aunt, described as mildly ridiculous in Book One, Chapter 13:

There was a fourth and most original figure in the Patriarchal tent, who also appeared before dinner. This was an amazing little old woman, with a face like a staring wooden doll too cheap for expression, and a stiff yellow wig perched unevenly on the top of her head, as if the child who owned the doll had driven a tack through it anywhere, so that it only got fastened on. Another remarkable thing in this little old woman was, that the same child seemed to have damaged her face in two or three places with some blunt instrument in the nature of a spoon; her countenance, and particularly the tip of her nose, presenting the phenomena of several dints, generally answering to the bowl of that article. A further remarkable thing in this little old woman was, that she had no name but Mr F.'s Aunt.

Awkward, surly, and even demented as Mr. F's Aunt may appear in the work of these 19th c. illustrators, their characterization of her are consistent both with Dickens's text, although Furniss conveys something more of her imperious nature and self-importance, whereas Phiz is concerned with her tendency towards histrionics. All of these illustrations are studies in dementia, but Phiz's situates the episode dramatically, as if it were on stage, with the commanding aunt pointing vigorously to support her accusation (center), the stupefied straight man, Arthur Clennam (left of the center), and Flora Finching, blissfully unaware of what has transpired, entering from stage right, as it were, into a fully dressed stage set. The machine-ruled, horizontal lines complement the strong vertical of the three figures, the chairs, and the fireplace. Whereas in most Victorian parlors, the presiding presence in the the family portrait would be a distinguished-looking male, but Phiz has placed a female portrait above the piano, right.

He's too proud a chap to eat it

Chapter 9, Book 2

Sir John Gilbert

Text Illustrated:

"None of your eyes at me," said Mr F.'s Aunt, shivering with hostility. "Take that."

"That" was the crust of the piece of toast. Clennam accepted the boon with a look of gratitude, and held it in his hand under the pressure of a little embarrassment, which was not relieved when Mr. F.'s Aunt, elevating her voice into a cry of considerable power, exclaimed, "He has a proud stomach, this chap! He's too proud a chap to eat it!" and, coming out of her chair, shook her venerable fist so very close to his nose as to tickle the surface. But for the timely return of Flora, to find him in this difficult situation, further consequences might have ensued. Flora, without the least discomposure or surprise, but congratulating the old lady in an approving manner on being "very lively to-night," handed her back to her chair.

"He has a proud stomach, this chap," said Mr F.'s relation, on being reseated. "Give him a meal of chaff!"

"Oh! I don't think he would like that, aunt," returned Flora.

"Give him a meal of chaff, I tell you," said Mr. F.'s Aunt, glaring round Flora on her enemy. "It’s the only thing for a proud stomach. Let him eat up every morsel. Drat him, give him a meal of chaff!".

Commentary:

Sir John Gilbert provided sporadic relief for the series' principal illustrator, Felix Octavius Carr Darley, typically providing a frontispiece for the third volume in a four-volume set. Here, however, he had to provide the second in the series of four. Although he has provided a lengthy caption, Gilbert gives neither page number nor chapter number: “‘He has a proud stomach, this chap! He's too proud a chap to eat it!’ and, coming out of her chair, shook her venerable fist so very close to his nose as to tickle the surface.” Gilbert has provided no guidance as to chapter or page; the angry blathering of Mr. F.'s Aunt only makes sense in the context of the chapter, in which Arthur Clennam, follows Miss Wade and Tattycoram to the "Patriarchal mansion" of Mr. Casby. One wonders what motivated John Gilbert to choose so minor an incident and so peripheral a character as Mr. F's Aunt for the book's third frontispiece. However, in a sense the tea-time confrontation epitomizes so much of the book as normative characters such as Arthur Clennam and Amy Dorrit encounter a metropolis teaming with False Wits.

Gilbert's introduction of yet another pallid Dickens hero, Arthur, is all the more effective for his being juxtaposed against such a singularly odd and barely comprehensible a character as Mr. F.'s Aunt, whom the illustrator has costumed as a perfectly respectable middle class matron of advanced years, complete with oversized hat and large linen napkin. Although the illustration does not make the situation completely clear, Mrs. F.'s Aunt has just thrust a piece of toast into his hand and is demanding that he finish for her, just as Flora would, were she present. Arthur, apparently a young, respectably dressed borgeois, reacts with mild shock and surprise to the elderly lady's aggressive behaviour, which is clearly intended to drive the rival for Flora's affections out of the house, never to visit Flora again.

Contemporary illustrator Sol Eytinge, Jr., depicted Flora as vacuous and Mr. F's Aunt as senile, but pliable in the 1867 Diamond Edition wood-engraving Flora and Mr. F's Aunt — a dual character study that, like this frontispiece by Gilbert, is based on Phiz's steel-engraving for Part 13 illustration Rigour of Mr. F's Aunt, to which J. A. Hammerton in The Dickens Picture-Book has appended the caption "Flora found him in this difficult situation".

The social realist James Mahoney in the Household Edition's fifty-eight illustrations does not include this scene, choosing instead to realize Clennam's shadowing Miss Wade and Tattycoram. There is little sympathy for the querulous, old woman in the Harry Furniss illustrations for the twelfth volume of The Charles Dickens Library Edition, Mr. F's Aunt, described as mildly ridiculous in Book One, Chapter 13:

There was a fourth and most original figure in the Patriarchal tent, who also appeared before dinner. This was an amazing little old woman, with a face like a staring wooden doll too cheap for expression, and a stiff yellow wig perched unevenly on the top of her head, as if the child who owned the doll had driven a tack through it anywhere, so that it only got fastened on. Another remarkable thing in this little old woman was, that the same child seemed to have damaged her face in two or three places with some blunt instrument in the nature of a spoon; her countenance, and particularly the tip of her nose, presenting the phenomena of several dints, generally answering to the bowl of that article. A further remarkable thing in this little old woman was, that she had no name but Mr F.'s Aunt.

Awkward, surly, and even demented as Mr. F's Aunt may appear in this frontispiece by John Gilbert, his characterization of her is consistent with the approach taken by Hablot Knight Browne in the original serial, and preferable to that of Sol Eytinge, Jr., in the Diamond Edition, although Furniss conveys something more of her imperious nature and self-importance.

Mr. F's Aunt

Chapter 9, Book 2

Harry Furniss

Commentary:

As is typical of Furniss's studies, the figure of Mr. F's Aunt stands against no backdrop, but reveals herself psychologically by her facial expression, posture, clothing, and some sort of talisman or representative possession — in this instance, a partially consumed piece of toast, which represents her mastery over Flora and her attempt to subjugate or extirpate Arthur as a rival for Flora's attention.

Furniss's character study shows Mr. F.'s Aunt about to thrust a piece of toast into Clennam's hand and demand that he consume it. However, the reader has already encountered the scene in the text, and Furniss shows her holding a crust of toast to establish the context, even if he does not depict Clennam or the background. Therefore, the reader is likely to recognize that Mr. F's Aunt is demanding that Clennam finish the crust for her, just as Flora would, were she present.

Awkward, surly, and even demented as Mr. F's Aunt may appear in this study by Harry Furniss, his characterization of her is consistent with the approach taken by Hablot Knight Browne in the original serial, and preferable to that of Sol Eytinge, Jr., in the Diamond Edition since this demented senior is hardly catatonic. Moreover, Furniss provides more detail about her dress, characterizes her by her expression, and conveys something more of her imperious nature and self-importance.

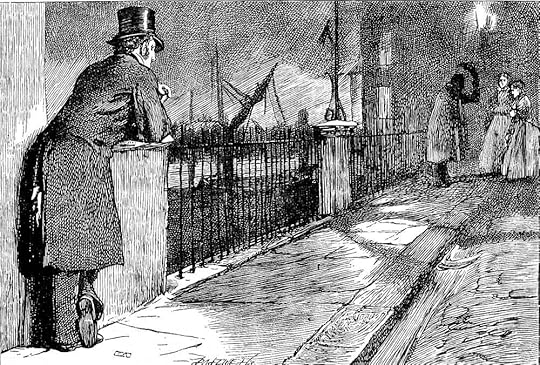

He stopped at the corner, seeming to look back expectantly up the street

Chapter 9, Book 2

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

At any hour later than sunset, and not least at that hour when most of the people who have anything to eat at home are going home to eat it, and when most of those who have nothing have hardly yet slunk out to beg or steal, it was a deserted place and looked on a deserted scene.

Such was the hour when Clennam stopped at the corner, observing the girl and the strange man as they went down the street. The man's footsteps were so noisy on the echoing stones that he was unwilling to add the sound of his own. But when they had passed the turning and were in the darkness of the dark corner leading to the terrace, he made after them with such indifferent appearance of being a casual passenger on his way, as he could assume.

When he rounded the dark corner, they were walking along the terrace towards a figure which was coming towards them. If he had seen it by itself, under such conditions of gas-lamp, mist, and distance, he might not have known it at first sight, but with the figure of the girl to prompt him, he at once recognised Miss Wade.

He stopped at the corner, seeming to look back expectantly up the street as if he had made an appointment with some one to meet him there; but he kept a careful eye on the three. When they came together, the man took off his hat, and made Miss Wade a bow. The girl appeared to say a few words as though she presented him, or accounted for his being late, or early, or what not; and then fell a pace or so behind, by herself. Miss Wade and the man then began to walk up and down; the man having the appearance of being extremely courteous and complimentary in manner; Miss Wade having the appearance of being extremely haughty. — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 9, "Appearance and Disappearance".

Commentary:

There is no comparable moment in the original Phiz illustrations. Back in London after the Italian sojourn, Mahoney takes readers to the Strand, somewhat defamiliarized after dark, where Miss Wade and Tattycoram rendezvous with an obsequiously charming stranger, whom the observer, Arthur Clennam, encounters a few days later at his mother's house. There, the foreigner (Blandois) is no longer charming, but insolent in the scene illustrated by Phiz for the sequence of chapters which make up serial installment 13 (December 1856). The reader, of course, wonders about the identities of the four figures in the scene, and, once he or she has encountered the textual passage seven pages later, about whatever commerce can exist between the aloof and anti-male Miss Wade and the devious Frenchman, who is evidently acting as Miss Wade's private investigator. Again, Mahoney underscores the curious conjunctions of disparate characters that occur in the second book.

The physical setting would have been one familiar not only to Londoners but also to readers of David Copperfield as David and his Aunt Betsey Trotwood occupied rooms in the Adelphi, overlooking the Thames, after her financial reversals. Having heard from Mrs. Tickit, the housekeeper for the Meagles while they are away on the Continent, that Harriet (nicknamed "Tattycoram") had been at Twickenham recently, Arthur Clennam is nevertheless surprised to encounter her at a distance talking to a foreign gentleman in a cape in the Strand, which parallels the river between Somerset House and Charing Cross, a distance of about three-quarters of a mile. He then trails the pair to the Adelphi Terrace, eleven attached townhouses designed in late neoclassical style by the Adams Brothers (1768-72), the vaulted terrace having wharves beneath, as suggested by the commercial river traffic in Mahoney's illustration. Blandois then has a conversation with the taller of the two women (right rear), undoubtedly Miss Wade, whom Clennam (left foreground in a business suit) recognizes from the action of Book One, Chapter 8. The atmosphere of mist and the distant gas-lamp under which the trio meet suggests the clandestine nature of the rendezvous, which the reader sees from Clennam's perspective.

Flora and Mr. F's Aunt

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Commentary:

Mid-nineteenth-century American illustrator Sol Eytinge, Jr., depicted Flora as vacuous and Mr. F's Aunt as senile, but pliable in the 1867 Diamond Edition dual character study Flora and Mr. F's Aunt — a character study that, like the frontispiece by Gilbert, is based on Phiz's steel-engraving for Part 13 (December 1856) illustration Rigour of Mr. F's Aunt, to which J. A. Hammerton in The Dickens Picture-Book has appended the caption "Flora found him in this difficult situation". The caption is superfluous, especially if one encounters the illustration in the original monthly part or volume, because Phiz establishes a clear context for the scene: tea-time at Casby's "patriarchal" mansion.

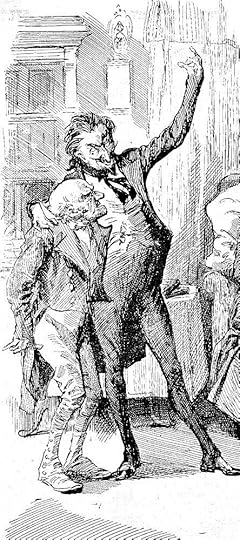

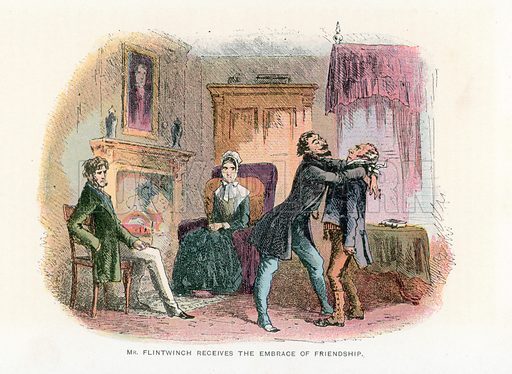

Mr. Flintwinch receives the Embrace of Friendship

Chapter 10, Book 2

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The key of the door below was now heard in the lock, and the door was heard to open and close. In due sequence Mr. Flintwinch appeared; on whose entrance the visitor rose from his chair, laughing loud, and folded him in a close embrace.

"How goes it, my cherished friend!" said he. "How goes the world, my Flintwinch? Rose-coloured? So much the better, so much the better! Ah, but you look charming! Ah, but you look young and fresh as the flowers of Spring! Ah, good little boy! Brave child, brave child!"

While heaping these compliments on Mr. Flintwinch, he rolled him about with a hand on each of his shoulders, until the staggerings of that gentleman, who under the circumstances was dryer and more twisted than ever, were like those of a teetotum nearly spent.

"I had a presentiment, last time, that we should be better and more intimately acquainted. Is it coming on you, Flintwinch? Is it yet coming on?" — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 10, "The Dreams of Mrs. Flintwinch thicken".

Commentary:

The drawing technique is characteristic of Browne's style in the late 1850s and early 1860s at its best, with a concern for composition, a pleasant handling of faces, and something of a sparseness of background details.

Indeed, the absence of emblematic details and visual commentary on the scene is quite remarkable, although, of course, Phiz here is exploiting the differences in height and body types for comedic effect and thoroughly enjoying the Englishman's discomfiture with the effusive affection of his French acquaintance. As always, Blandois is "insinuating" and horribly familiar, although here at least he is not smoking in the third chapter of the December 1856 (thirteenth monthly) instalment — perhaps out of deference to his hostess, a rigid Calvinist.

The other two figures in the scene constitute an audience for Blandois' flamboyant display of affection. To the right, Arthur Clennam (bearing a marked resemblance to his father, whose portrait hangs above the mantelpiece and its vases or urns) judges the pair critically. His gaze does not entirely match his "amazement, suspicion, resentment, and shame". Her business dealings with both men, however, oblige Mrs. Clennam to view their behaviour with tolerance, but clearly she is viewing the affectionate greeting of Blandois with any enthusiasm. The gazes of both aloof mother and disapproving son direct the reader to study Jeremiah Flintwinch's rigid posture and controlled expression, his failure to reciprocate implied by his arms hanging limply at his sides: "reticent and wooden" indeed! Although it is not immediately apparent from the fireplace (left) and chest of drawers (rear), the scene is the invalid Mrs. Clennam's bedroom, as suggested by the canopy and side table (right), on which is a conspicuous detail — a book, probably (given her fundamentalist bent) a Bible.

The Crimean War having just ended with the capture of Sebastopol, the awkward friendship of the phlegmatic Briton, Jeremiah Flintwinch, and his effusive Gallic chum (who bears some resemblance to the Emperor of the French, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, otherwise, Napoleon III) may be a reflection of the uneasy alliance of Great Britain and France. As a Liberal opposed to Russian autocracy and expansionism, Dickens made no bones about being a Francophile in his framed tale in Household Words, for December 1854, "The Tale of Richard Doubledick in The Seven Poor Travellers, and certainly the fall of the chief Russian port on the Black Sea on 8 September 1855 had vindicated Dickens's championing of the pact that resulted in Czar Alexander II's signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1856.

....He doesn't look like he is embracing him to me, he looks like he is murdering him.

The Plotters

Chapter 10, Book 2

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

The key of the door below was now heard in the lock, and the door was heard to open and close. In due sequence Mr. Flintwinch appeared; on whose entrance the visitor rose from his chair, laughing loud, and folded him in a close embrace.

"How goes it, my cherished friend!" said [Blandois, rolling Mr. Flintwich [sic] about.] "How goes the world, my Flintwinch? Rose-coloured? So much the better, so much the better! Ah, but you look charming! Ah, but you look young and fresh as the flowers of Spring! Ah, good little boy! Brave child, brave child!"

While heaping these compliments on Mr. Flintwinch, he rolled him about with a hand on each of his shoulders, until the staggerings of that gentleman, who under the circumstances was dryer and more twisted than ever, were like those of a teetotum nearly spent.

"I had a presentiment, last time, that we should be better and more intimately acquainted. Is it coming on you, Flintwinch? Is it yet coming on?" Chapter 10, Book 2

Commentary:

Fin-de-siécle illustrator Harry Furniss has reinterpreted the secondary antagonists of the novel. In this scene, the murderer Rigaud (alias "Lagnier" and now "Blandois"), having returned to London from Italy, warmly greets his "old friend," Mrs. Clennam's cunning business associate and confidant, Jeremiah Flintwinch. In the twenty-eight Charles Dickens Library Edition illustrations, the melodramatic Gallic scoundrel appears just three times, most prominently in this twentieth lithograph based on a vigorous pen-and-ink sketch which, unlike James Mahoney's realistic interpretation in the 1873 Household Edition, captures the whimsical and the fantastic elements of the villain as visualized by Phiz in 1856-57.

The chief illustrators of the book in the nineteenth century, Phiz and Mahoney, and the first great Dickens illustrator of the twentieth, Furniss, have all focused on the same aspect of the relationship between the French swindler and murderer and the crusty keeper of Mrs. Clennam's personal and business secrets, Jeremiah Flintwinch. Whereas Phiz and Mahoney, like Furniss, exploit to the situation for its character comedy as they use it to advance the plot, Furniss seems simply interested in the contrast between the stone-faced Englishman and the flamboyant, satanic Frenchman, emphasizing the difference in their height and in their faces.

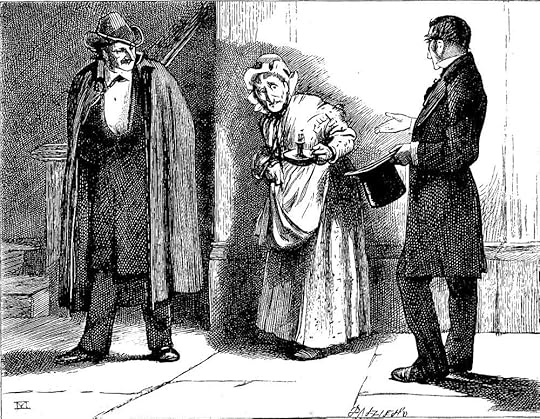

Pray tell me, Affery," said Arthur, "who is this gentleman?"

Chapter 10, Book 2

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

It's true! Him again, dear Mrs. Flintwinch," cried the stranger. "Open the door, and let me take my dear friend Jeremiah to my arms! Open the door, and let me hasten myself to embrace my Flintwinch!"

"He's not at home," cried Affery.

"Fetch him!' cried the stranger. "Fetch my Flintwinch! Tell him that it is his old Blandois, who comes from arriving in England; tell him that it is his little boy who is here, his cabbage, his well-beloved! Open the door, beautiful Mrs. Flintwinch, and in the meantime let me to pass upstairs, to present my compliments — homage of Blandois — to my lady! My lady lives always? It is well. Open then!"

To Arthur's increased surprise, Mistress Affery, stretching her eyes wide at himself, as if in warning that this was not a gentleman for him to interfere with, drew back the chain, and opened the door. The stranger, without ceremony, walked into the hall, leaving Arthur to follow him.

"Despatch then! Achieve then! Bring my Flintwinch! Announce me to my lady!" cried the stranger, clanking about the stone floor.

"Pray tell me, Affery," said Arthur aloud and sternly, as he surveyed him from head to foot with indignation; "who is this gentleman?"

"Pray tell me, Affery," the stranger repeated in his turn, 'who — ha, ha, ha! — who is this gentleman?" — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 10, "The Dreams of Mrs. Flintwinch thicken" p. 278.

Commentary:

Mahoney's realistic version of what had been a humorous and somewhat caricatural illustration in the original serial "Mr. Flintwinch receives the Embrace of Friendship" is accompanied by a much longer caption in the American Household Edition (New York: Harper and Brothers) — "Despatch then! Achieve then! Bring Mr. Flintwinch! Announce me to my lady!" cried the stranger, clanking about the stone floor. "Pray tell me, Affery," said Arthur aloud and sternly, as he surveyed him from head to foot with indignation, "who is this gentleman?" — Book 2, chap. 10. Blandois-Lagnier-Rigaud appears in twelve of fifty-eight illustrations (the majority — seven — of the Blandois illustrations occur in Book the Second).

The chief illustrators of the book in the nineteenth century, Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne) and James Mahoney, and the first great Dickens illustrator of the twentieth, Harry Furniss, have all focused on the same aspect of the relationship between the French swindler and murderer, Rigaud (alias "Blandois" and "Lagnier"), and the crusty keeper of Mrs. Clennam's personal and business secrets, Jeremiah Flintwinch. Whereas Phiz and Furniss exploit to the situation for its character comedy, Mahoney is more interested in using the nocturnal scene to advance the reader's construction of the plot. Whereas Furniss is simply interested in presenting the contrast between the short, stone-faced Englishman and the flamboyant, satanic Frenchman, emphasizing the difference in their height and in their faces, Mahoney (Furniss's immediate source) offers a highly realistic and rather bland interpretation of the Gallic scoundrel but renders Affery (center) a caricature. The reader is left to judge, based on Dickens's relating his suspicions of and antipathy for the caped figure calling so late, what the expression on Arthur's face must be.

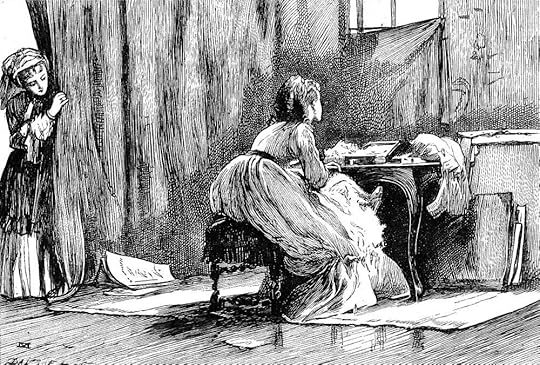

When I first saw her there she was alone, and her work had fallen out of her hand.

Chapter 11, Book 2

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

Well, it is a rather bare lodging up a rather dark common staircase, and it is nearly all a large dull room, where Mr. Gowan paints. The windows are blocked up where any one could look out, and the walls have been all drawn over with chalk and charcoal by others who have lived there before — oh, — I should think, for years!

There is a curtain more dust-coloured than red, which divides it, and the part behind the curtain makes the private sitting-room.

When I first saw her there she was alone, and her work had fallen out of her hand, and she was looking up at the sky shining through the tops of the windows. Pray do not be uneasy when I tell you, but it was not quite so airy, nor so bright, nor so cheerful, nor so happy and youthful altogether as I should have liked it to be.

On account of Mr. Gowan's painting Papa's picture (which I am not quite convinced I should have known from the likeness if I had not seen him doing it), I have had more opportunities of being with her since then than I might have had without this fortunate chance. She is very much alone. Very much alone indeed. — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 11, "A Letter from Little Dorrit".

Commentary:

Little Dorrit's letter to Arthur Clennam reveals her character in her own words rather than those of the narrator. Her modesty and her tendency not to take her recent good fortune for granted are obvious as she describes in a letter intended for Arthur Clennam back in London the artist's studio that Henry Gowan has rented in Venice, apparently without any regard for the sensibilities and comfort of his young bride, Pet Meagles. This is the same studio in which Phiz in the original serial had set the conflict between the painter and his mastiff, Lion, whom he punishes brutally for dog's threatening to attack the model, Blandois, in "Instinct Stronger than Training" in Book 2, Chapter 6, "Something Right Somewhere". There is no illustration for Book 2, Chapter 11, in the original serial.

In the Mahoney illustration, Little Dorrit looks behind the curtain she mentions in the letter and discovers Mrs. Gowan as a virtual prisoner without even the minimal view of the world that Little Dorrit enjoyed in her Marshalsea garret. In order to break her spirit and exert his control over his young wife, Henry Gowan has taken an artist's studio in an out-of-the-way spot; nevertheless, Pet receives a visit from her new friend, the English heiress Amy Dorrit (left in the illustration). There is no romance, no exotic backdrop for Henry Gowan's painting, but surely that is Mahoney's point: the self-centered artist has failed to provide any mental or emotional stimulation for his wife, who might as well be a prisoner in the Marshalsea as a rich foreign tourist in Venice.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 8..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 8..."Was anyone else surprised at the lack of fanfare when MiniPet's pregnancy was mentioned? (I almost said revealed, but that word implies more joyous anticipation.) I ..."

Or maybe this baby was expected by the time they were married. So, not a big to-do as we would expect from the parents. Was this what MiniPet was hinting to Clennam in their walk and talk. peace, janz

Kim wrote: "

When I first saw her there she was alone, and her work had fallen out of her hand.

Chapter 11, Book 2

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

Well, it is a rather bare lodging up a rather dark common..."

Ah Kim, what a powerful illustration from Mahoney you chose to post. The commentary is spot on and certainly helps the reader put into context the importance of illustrations.

As noted, in Browne’s illustration of Amy’s room in the Marshalsea we see her looking out a window in which the sun is streaming in. Her room is depicted as bright, well organized and, perhaps we could even say cheerful. Maggy is there as a companion. Browne’s illustration is in support of the text where Amy recounts the tale of a princess to Maggy. I think most important to the illustration is Browne’s placement of a bonnet and a cloak on the bed. The suggestion held within the illustration is that while Amy is in jail she can still dream, still have friends, still enter and exit the Marshalsea almost without restriction.

In the Mahoney illustration we see the brilliance of Mahoney. As an illustrator who had seen Browne’s illustration Mahoney offers the reader/viewer a completely different scenario. In his illustration, Pet is also in a room by a window, There is no bright light in the room. There is no sun streaming in the window. Pet’s head in looking down, not out as Browne showed in his illustration. How important is a single gesture, the tilting of a head in a picture! There is little furniture in the room. There is, however, a clear suggestion of neglect, faded curtains, lost chances.

Mahoney has presented the reader with what one could assume should be Amy’s world. On the other hand, Pet’s world should be more like what Browne depicted as Amy's room. Pet is is Venice. She is married. Her father is financially well off.