The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit

>

Reflections on the Novel as a Whole

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

As long as we are sharing our reflections of the novel, here is the reflections of George Gissing on the book:

"In one of those glimpses of my childhood which are clearest and most recurrent, I see lying on the table of a familiar room a thin book in a green-paper cover, which shows the title, Our Mutual Friend. What that title meant I could but vaguely conjecture; though I fingered the pages, I was too young to read them with understanding; but this thin, green book notably impressed me and awoke my finer curiosity. For I knew that it had been received with smiling welcome; eager talk about it fell upon my ears; and with it was associated a name which from the very beginning of things I had heard spoken respectfully, admiringly. Charles Dickens, Alfred Tennyson -- these were to me as the names of household gods; I uttered them with reverence before two of the framed portraits upon our walls.

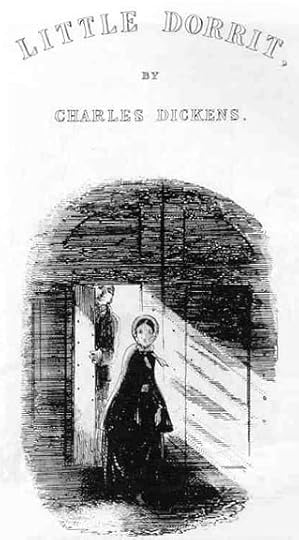

Another glimpse into that homely cloud-land shows me a bound volume, rather heavy for small hands, which was called Little Dorrit. I saw it only as a picture book, and found most charm in the frontispiece. This represented a garret bedroom, with a lattice through which streamed the sunshine; there amid stood a girl, her eyes fixed upon the prospect of city roofs. Often and long did I brood over this picture, which touched my imagination in ways more intelligible to me now than then. To begin with, there was the shaft of sunlight, always, whether in nature or in art, powerful to set me dreaming. Then the view from the window -- vague, suggestive of vastness; I was told that those were the roofs of London, and London, indefinitely remote, had begun to play the necromancer in my brain. Moreover, the poor bareness of that garret, and the wistful gazing of the lonely girl, held me entranced. It was but the stirring of a child's fancy, excited by the unfamiliar; yet many a time in the after years, when, seated in just such a garret, I saw the sunshine flood the table at which I wrote, that picture in Little Dorrit has risen before me, and I have half believed that my childish emotion meant the unconscious foresight of things to come."

George Gissing

"In one of those glimpses of my childhood which are clearest and most recurrent, I see lying on the table of a familiar room a thin book in a green-paper cover, which shows the title, Our Mutual Friend. What that title meant I could but vaguely conjecture; though I fingered the pages, I was too young to read them with understanding; but this thin, green book notably impressed me and awoke my finer curiosity. For I knew that it had been received with smiling welcome; eager talk about it fell upon my ears; and with it was associated a name which from the very beginning of things I had heard spoken respectfully, admiringly. Charles Dickens, Alfred Tennyson -- these were to me as the names of household gods; I uttered them with reverence before two of the framed portraits upon our walls.

Another glimpse into that homely cloud-land shows me a bound volume, rather heavy for small hands, which was called Little Dorrit. I saw it only as a picture book, and found most charm in the frontispiece. This represented a garret bedroom, with a lattice through which streamed the sunshine; there amid stood a girl, her eyes fixed upon the prospect of city roofs. Often and long did I brood over this picture, which touched my imagination in ways more intelligible to me now than then. To begin with, there was the shaft of sunlight, always, whether in nature or in art, powerful to set me dreaming. Then the view from the window -- vague, suggestive of vastness; I was told that those were the roofs of London, and London, indefinitely remote, had begun to play the necromancer in my brain. Moreover, the poor bareness of that garret, and the wistful gazing of the lonely girl, held me entranced. It was but the stirring of a child's fancy, excited by the unfamiliar; yet many a time in the after years, when, seated in just such a garret, I saw the sunshine flood the table at which I wrote, that picture in Little Dorrit has risen before me, and I have half believed that my childish emotion meant the unconscious foresight of things to come."

George Gissing

This review is from the "University Literary Magazine" whatever that is, and was published on October 1857.

"Dickens has given another production to the world; yes, Little Dorrit is finished, and the critics at last have a chance to use the author up to their hearts' content. We give the reader warning at the start that we do not intend any studied criticism of Mr. Dickens' production; we merely intend to glance at it, and give expression to our opinion of some of the characters, and to a few thoughts which the characters may suggest. To tell the truth, gentle reader, we hardly think Little Dorrit is worth reading. In the first place, it is too long, and then, too, it lacks interest; but there is one reason why it has claims upon our attention, which is, that it contains certain peculiarities of style and character which are to be found in no other of Dickens' works. Dickens' style, as we all know, is always peculiar, but in his last work he has carried this peculiarity to an almost absurd extent - to such an extent, in fact, that it becomes rather a difficult matter sometimes for us, simple plain Americans, to understand exactly what he is driving at.

The story begins in a manner most outrageously peculiar and "bizarre." "Thirty years ago, Marseilles lay burning in the sun one day," and then the whole of the following sentence is one extravagant figure, too extravagant, in fact, to be any thing but ridiculous. The sun is staring at the earth, the earth returning the compliment; and the grape vines busily engaged in the rustic, scandalous occupation of winking at each other, and at both sun and earth. Ridiculous ain't it, gentle reader? After puzzling ourselves over the above sentence for sometime, we came to the conclusion that the author meant simply to convey the impression that it was "powerful hot" in Marseilles about that time; but we will not attempt to go through the whole book, and give a list of the errors, grammatical and rhetorical, therein contained - that were well-nigh an endless task - but we will content ourselves with a review of some of its most prominent characters. The main feature of Little Dorrit is the mystery which pervades the whole story. There are more incomprehensible characters collected in the small space of one book than we generally see blended together in real life - to so great an extent is this mystery carried, that it is often no easy task to see the connection and relations which the different characters sustain to each other. In our opinion, there are a good many characters in the book which might have been altogether left out, without seriously detracting from the interest of the story - such as Maggie - whose most pleasant reminiscences were connected with the hospital and the good "chicken" found there; and there, too, is Baptiste, who seems introduced for no other purpose than to show the facility with which the author could speak broken English. And Flora too: what interest is inspired by her presence? we are disgusted by her continual attempts to entangle Clenam in the web of his old love, and by her utter disregard for all punctuation.

Speaking of incomprehensible characters, we will begin with the strangest of them all - Mrs. Clenam. We frankly confess that we do not understand her; who does? We do not believe that there resides in the world a parallel to this character - 'tis both false in fact and untrue to nature. She is represented as being devoid of all the finer feelings, some of which always characterize woman - no maternal affection for her son-no kindly feelings towards the rest of mankind. She is cold, calculating and selfish, avaricious and cruel, with but one passion gnawing at her heart, and that, that most unfeminine of all passions - revenge. We can imagine woman brought down to the lowest depths of misery and despair; we can picture her raging like the tigress deprived of her young; but we cannot fancy her the cold, calculating demon, Mrs. Clenam. And what is the cause of all this hate and revenge, which has turned her woman's heart into that of a fiend? Simply some intrigue of a weak-minded husband, who was terribly afraid of her, and whom she never loved. And next comes Arthur Clenam, who is a good sort of a fellow; the early part of whose life is shrouded in mystery; but to whom one would think some great calamity had happened in his youth, which had cast a gloom over the rest of his days, but of which the author does not see fit to inform us. He is the especial patron of Little Dorrit, who, by way of rewarding him for the same, falls in love with and finally marries him. Mr. and Mrs. Flintwintch complete this very mysterious Clenam establishment. We will dismiss them by saying, that Mr. F. Was a great rascal, and Mrs. F as great a fool.

And now we will wind up what we have to say, by a hurried sketch of another family, not quite so respectable, nor half so incomprehensible. Gentle reader we beg leave to introduce you to the father of the Marchalsea. Chapter VI, which treats of this gentleman and his family, is an exception to most of the chapters in Little Dorrit. In it you recognize something of the author of David Copperfield and Dombey and Son. This is one of the few chapters throughout the book in which "Richard is himself again;" where you see the old pathos beaming out from every line; where all the affectation of high life is forgotten, and Dickens is speaking the language of his heart, and describing a scene not uncommon in England's capital. Mr, Dorrit is making his first entrance into the debtors' prison of the Marchalsea. Suppose we compare him in adversity and prosperity, and see whether the difference is not so great as to be unnatural. In the words of the author, he was "a shy, retiring man, well-looking, though in an effeminate style; with a mild voice, curling hair, and irresolute hands-rings upon the fingers in those days-which nervously wandered to his trembling lips a hundred times in the first half four of his acquaintance-with the jail." And now, by way of contrast, let us look at him in prosperity. No one would recognize in the elegant Mr. Dorrit, travelling on the continent for his health, accompanied by his family and the accomplished Mrs. General, the poor, broken-hearted inmate of the Marshalsae. Prosperity effected too great a change in Mr. Dorrit's whole nature - his whole character, and even his personal appearance, undergoes a complete renovation - from being the humble recipient of the visitor's bounty, he becomes purse-proud, selfish and exacting. He treats his daughter Amy, who is devoted to him, with cruelty, and bestows all his affection upon Edward and Fanny, who have never done aught to deserve it. After a study of this character, we come to the conclusion that he is a cruel, remorseless, old tyrant, willing to sacrifice his daughter's happiness, and every thing else that should be held sacred, for the sake of appearances, or for his own private gratification. Dickens kills Mr. Dorrit off just in time to keep him from marrying Mrs. General, and thus saved Little Dorrit many tears, Fanny much useless opposition, and the whole Dorrit family from an everlasting disgrace.

We will pass hurriedly over the few remaining characters, merely stating that Mr. Edward Dorrit was a great "swell," Miss Fanny a heartless flirt, and Mr. Frederick Dorrit a milk-and-waterish sort of a character, who is a useless encumbrance, and is brought on for no other purpose than to fill up space; and now we come to the little heroine Little Dorrit. To sum up her character in a few words, she is what the old fogies call a real good girl-a model to the girls for all future generations. She is too good, in fact, to be natural. Girls of the Little Dorrit stamp generally reside in tracts and Sunday school books. They seldom inhabit our terrestrial sphere in this iron age of ours; and when they are born among us, they seldom are long for this world; they stay here but for a short space, and then wing their flight to another and a better world, where their precocious sanctity will be more appreciated and their death-bed sayings go abroad over the land, and many are converted by the reading thereof. Little Dorrit, however, meets with a better fate. She thrives on persecution, like a frog on buck-shot, and, in spite of the cruelty and bad treatment of her kinsfolk, arrives at the age of discretion, catches a beau, marries him, and is as happy as the day is long. Some how or other we have a sort of contempt for Little Dorrit. She is too good and easy and has too little fire and independence about her to please our fancy. We like to see a girl show the proper degree of spirit, and retaliate sometimes, instead of being, like Little Dorrit, always ready to offer the other cheek when one is struck, and for an insult return a never-failing tear.

Well, we will skip over the rest of the characters, and not stop to enlarge upon the terrible tempers of Miss Wade and Tattycoram, the energy of Panck's, the blandness of the Patriarch, and the mental hallucination of Mr. F's aunt. After having impartially and thoroughly reviewed the evidence, we can't help coming to the conclusion that Little Dorrit is a failure, and that "Boz" had better look to his laurels."

K.L.

Getting back to my "whatever that is" comment, looking further I found that the magazine was published in Richmond, Virginia by Chas. H. Wynne's Steam Printing House, and that the address of the magazine was simply: "Editors of University Literary Magazine, University of Va.

And now I am going to try to find out who "K. L." was and why he finished the book in the first place.

"Dickens has given another production to the world; yes, Little Dorrit is finished, and the critics at last have a chance to use the author up to their hearts' content. We give the reader warning at the start that we do not intend any studied criticism of Mr. Dickens' production; we merely intend to glance at it, and give expression to our opinion of some of the characters, and to a few thoughts which the characters may suggest. To tell the truth, gentle reader, we hardly think Little Dorrit is worth reading. In the first place, it is too long, and then, too, it lacks interest; but there is one reason why it has claims upon our attention, which is, that it contains certain peculiarities of style and character which are to be found in no other of Dickens' works. Dickens' style, as we all know, is always peculiar, but in his last work he has carried this peculiarity to an almost absurd extent - to such an extent, in fact, that it becomes rather a difficult matter sometimes for us, simple plain Americans, to understand exactly what he is driving at.

The story begins in a manner most outrageously peculiar and "bizarre." "Thirty years ago, Marseilles lay burning in the sun one day," and then the whole of the following sentence is one extravagant figure, too extravagant, in fact, to be any thing but ridiculous. The sun is staring at the earth, the earth returning the compliment; and the grape vines busily engaged in the rustic, scandalous occupation of winking at each other, and at both sun and earth. Ridiculous ain't it, gentle reader? After puzzling ourselves over the above sentence for sometime, we came to the conclusion that the author meant simply to convey the impression that it was "powerful hot" in Marseilles about that time; but we will not attempt to go through the whole book, and give a list of the errors, grammatical and rhetorical, therein contained - that were well-nigh an endless task - but we will content ourselves with a review of some of its most prominent characters. The main feature of Little Dorrit is the mystery which pervades the whole story. There are more incomprehensible characters collected in the small space of one book than we generally see blended together in real life - to so great an extent is this mystery carried, that it is often no easy task to see the connection and relations which the different characters sustain to each other. In our opinion, there are a good many characters in the book which might have been altogether left out, without seriously detracting from the interest of the story - such as Maggie - whose most pleasant reminiscences were connected with the hospital and the good "chicken" found there; and there, too, is Baptiste, who seems introduced for no other purpose than to show the facility with which the author could speak broken English. And Flora too: what interest is inspired by her presence? we are disgusted by her continual attempts to entangle Clenam in the web of his old love, and by her utter disregard for all punctuation.

Speaking of incomprehensible characters, we will begin with the strangest of them all - Mrs. Clenam. We frankly confess that we do not understand her; who does? We do not believe that there resides in the world a parallel to this character - 'tis both false in fact and untrue to nature. She is represented as being devoid of all the finer feelings, some of which always characterize woman - no maternal affection for her son-no kindly feelings towards the rest of mankind. She is cold, calculating and selfish, avaricious and cruel, with but one passion gnawing at her heart, and that, that most unfeminine of all passions - revenge. We can imagine woman brought down to the lowest depths of misery and despair; we can picture her raging like the tigress deprived of her young; but we cannot fancy her the cold, calculating demon, Mrs. Clenam. And what is the cause of all this hate and revenge, which has turned her woman's heart into that of a fiend? Simply some intrigue of a weak-minded husband, who was terribly afraid of her, and whom she never loved. And next comes Arthur Clenam, who is a good sort of a fellow; the early part of whose life is shrouded in mystery; but to whom one would think some great calamity had happened in his youth, which had cast a gloom over the rest of his days, but of which the author does not see fit to inform us. He is the especial patron of Little Dorrit, who, by way of rewarding him for the same, falls in love with and finally marries him. Mr. and Mrs. Flintwintch complete this very mysterious Clenam establishment. We will dismiss them by saying, that Mr. F. Was a great rascal, and Mrs. F as great a fool.

And now we will wind up what we have to say, by a hurried sketch of another family, not quite so respectable, nor half so incomprehensible. Gentle reader we beg leave to introduce you to the father of the Marchalsea. Chapter VI, which treats of this gentleman and his family, is an exception to most of the chapters in Little Dorrit. In it you recognize something of the author of David Copperfield and Dombey and Son. This is one of the few chapters throughout the book in which "Richard is himself again;" where you see the old pathos beaming out from every line; where all the affectation of high life is forgotten, and Dickens is speaking the language of his heart, and describing a scene not uncommon in England's capital. Mr, Dorrit is making his first entrance into the debtors' prison of the Marchalsea. Suppose we compare him in adversity and prosperity, and see whether the difference is not so great as to be unnatural. In the words of the author, he was "a shy, retiring man, well-looking, though in an effeminate style; with a mild voice, curling hair, and irresolute hands-rings upon the fingers in those days-which nervously wandered to his trembling lips a hundred times in the first half four of his acquaintance-with the jail." And now, by way of contrast, let us look at him in prosperity. No one would recognize in the elegant Mr. Dorrit, travelling on the continent for his health, accompanied by his family and the accomplished Mrs. General, the poor, broken-hearted inmate of the Marshalsae. Prosperity effected too great a change in Mr. Dorrit's whole nature - his whole character, and even his personal appearance, undergoes a complete renovation - from being the humble recipient of the visitor's bounty, he becomes purse-proud, selfish and exacting. He treats his daughter Amy, who is devoted to him, with cruelty, and bestows all his affection upon Edward and Fanny, who have never done aught to deserve it. After a study of this character, we come to the conclusion that he is a cruel, remorseless, old tyrant, willing to sacrifice his daughter's happiness, and every thing else that should be held sacred, for the sake of appearances, or for his own private gratification. Dickens kills Mr. Dorrit off just in time to keep him from marrying Mrs. General, and thus saved Little Dorrit many tears, Fanny much useless opposition, and the whole Dorrit family from an everlasting disgrace.

We will pass hurriedly over the few remaining characters, merely stating that Mr. Edward Dorrit was a great "swell," Miss Fanny a heartless flirt, and Mr. Frederick Dorrit a milk-and-waterish sort of a character, who is a useless encumbrance, and is brought on for no other purpose than to fill up space; and now we come to the little heroine Little Dorrit. To sum up her character in a few words, she is what the old fogies call a real good girl-a model to the girls for all future generations. She is too good, in fact, to be natural. Girls of the Little Dorrit stamp generally reside in tracts and Sunday school books. They seldom inhabit our terrestrial sphere in this iron age of ours; and when they are born among us, they seldom are long for this world; they stay here but for a short space, and then wing their flight to another and a better world, where their precocious sanctity will be more appreciated and their death-bed sayings go abroad over the land, and many are converted by the reading thereof. Little Dorrit, however, meets with a better fate. She thrives on persecution, like a frog on buck-shot, and, in spite of the cruelty and bad treatment of her kinsfolk, arrives at the age of discretion, catches a beau, marries him, and is as happy as the day is long. Some how or other we have a sort of contempt for Little Dorrit. She is too good and easy and has too little fire and independence about her to please our fancy. We like to see a girl show the proper degree of spirit, and retaliate sometimes, instead of being, like Little Dorrit, always ready to offer the other cheek when one is struck, and for an insult return a never-failing tear.

Well, we will skip over the rest of the characters, and not stop to enlarge upon the terrible tempers of Miss Wade and Tattycoram, the energy of Panck's, the blandness of the Patriarch, and the mental hallucination of Mr. F's aunt. After having impartially and thoroughly reviewed the evidence, we can't help coming to the conclusion that Little Dorrit is a failure, and that "Boz" had better look to his laurels."

K.L.

Getting back to my "whatever that is" comment, looking further I found that the magazine was published in Richmond, Virginia by Chas. H. Wynne's Steam Printing House, and that the address of the magazine was simply: "Editors of University Literary Magazine, University of Va.

And now I am going to try to find out who "K. L." was and why he finished the book in the first place.

There were a number of cover illustrations, title pages, wrappers, etc. that I skipped earlier because I felt they gave away too much of the story. Now that we are finished here they are:

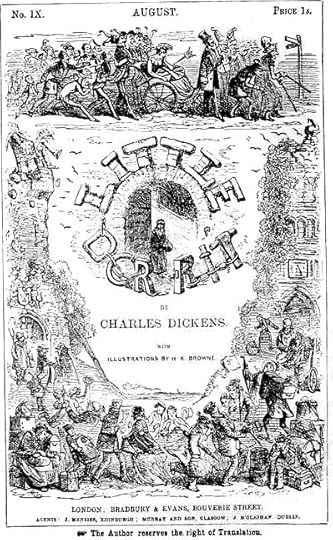

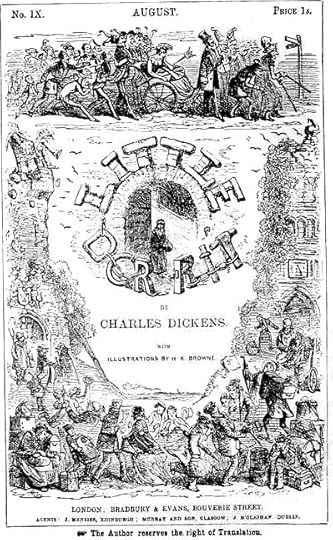

Cover for monthly parts of "Little Dorrit," August 1856

Phiz

Commentary:

Whereas millions of purchasers of the novel in volume form, beginning in June 1857, have had the opportunity to study Phiz's forty illustrations for Little Dorrit, placed immediately adjacent to the passages they realise, the thousands — Robert L. Patten notes that the opening circulation was 38,000 — who purchased the monthly parts had the disadvantage of not encountering the two illustrations for each monthly-part thus juxtaposed. However, each regular serial installment purchaser encountered nineteen times the blue-green monthly wrapper with its implicit commentary on the novel. At each successive monthly purchase, the serial reader re-considered the wrapper, studying how its design reflected upon chapters already read and pondering how the complicated design was a key to future chapters, although this design, unlike that for A Tale of Two Cities, is emblematic and does not enshrine certain scenes in the plot. The allegorical figures on the monthly wrapper are often ambiguous in their meaning, although the goddess Britannia, symbolic of Great Britain and British society, in the centre of the upper register, is obvious enough with her helmet, shield, and chariot. The book's title in bricks and chains makes manifest the connection between the female protagonist (centre, surrounded by the words) and the Marshalsea Prison in the Borough, immediately south of London Bridge. Two other recognizable figures are Jeremiah Flintwinch and Mrs. Clennam in her wheelchair, lower right.

Like Bleak House, Little Dorrit depends for a great part of its effectiveness upon Dickens' translation of his social vision into symbolic vision: Mrs. Clennam's paralysis, the parasitic Barnacles, and perhaps above all, the motif of the prison. The successes and failures of collaboration depend partly on Dickens' assignment of subject, and partly on Browne's execution of each subject. Like all the monthly serial novels from Nicholas Nickleby onward, this one begins with a cover design intended to embody the novel's main themes; and like Martin Chuzzlewit, Dombey and Son, and perhaps more arguably, David Copperfield and Bleak House, Little Dorrit ends in the monthly parts and thus opens in the bound edition with a complementary pair of etchings that serve both as foreshadowing and retrospective devices. The cover design is more unified than Bleak House's, and quite a bit less specific as to individual characters. In the center, Amy Dorrit stands at the outer gate of Marshalsea Prison, just having emerged from within; she stands "in a shaft of sunlight, this sunlight — which here, as in the etched title page, lends a sanctified air to Amy — comes from within the prison, and that in a sense Amy goes into a world much darker than the prison. When it is repeated on the title page, this image is in turn complemented by the novel's frontispiece.

The "political cartoon" across the top, showing the blind and halt leading a dozing Britannia with a retinue of fools and toadies, is largely the same in the drawing, but one important detail differs in the extension of this motif down the sides of the design, while others are developed more clearly in the actual woodcut. The crumbling castle tower is in the drawing, as is the man sitting precariously on top of it, a newspaper in his lap and a cloth over his eyes, oblivious of the deterioration of the building. But while in the cut the church tower is clearly ruined, with a raven (or jackdaw?) atop it, the ruin is less evident in the drawing, and on the tower we have a fat, bewigged man asleep on an enormous cushion; this looks like something out of the Bleak House cover, since the cushion is probably meant to be the woolsack, and the man a high member of the legal profession. I suspect that Dickens told Browne to remove him, as his place on the church is inappropriate. The black bird in the cut would seem to signify the general decay of Victorian society and the prevalence of death, or, if it is a jackdaw, the thievery of institutions; yet I cannot find it any more appropriate to the church. The child playing leapfrog with the gravestones, a concept we have earlier traced back to Browne's frontispiece for Godfrey Malvern, here underlines the theme of indifference and irresponsibility. One other alteration likely to have been at Dickens' insistence is the representation of Mrs. Clennam in her wheelchair, with Flintwinch standing alongside, In the drawing we see instead, from the rear, a woman in a bath chair, pushed by a man. Dickens probably wished to have a more particular representation of Arthur's mother, as she and Jeremiah have a malevolent appearance in the cut and stand out as the only other definite characters, apart from Amy.

Little Dorrit's cover is effective in conveying certain themes — decay, indifference, irresponsibility of government, and confusion — as well as foreshadowing major tonalities of the novel, such as the dark prison, Little Dorrit as central figure, and Mrs. Clennam and Flintwinch as evil genii presiding over the ramifications of the plot. Along with the Bleak House cover it is the most socially conscious of the designs, and presents its ideas more directly than its predecessor. Dickens must have supplied a good deal of direction for this wrapper, given that the date of the following letter (19 October 1855) is approximately six weeks before the publication date of Part 1:

"Will you give my address to B. and E. without loss of time, and tell them that although I have communicated at full explanation length with Browne, I have heard nothing of or from him. Will you add that I am uneasy and wish they would communicate with Mr. Young, his partner, at once. Also that I beg them to be so good as send Browne my present address?"

Cover for monthly parts of "Little Dorrit," August 1856

Phiz

Commentary:

Whereas millions of purchasers of the novel in volume form, beginning in June 1857, have had the opportunity to study Phiz's forty illustrations for Little Dorrit, placed immediately adjacent to the passages they realise, the thousands — Robert L. Patten notes that the opening circulation was 38,000 — who purchased the monthly parts had the disadvantage of not encountering the two illustrations for each monthly-part thus juxtaposed. However, each regular serial installment purchaser encountered nineteen times the blue-green monthly wrapper with its implicit commentary on the novel. At each successive monthly purchase, the serial reader re-considered the wrapper, studying how its design reflected upon chapters already read and pondering how the complicated design was a key to future chapters, although this design, unlike that for A Tale of Two Cities, is emblematic and does not enshrine certain scenes in the plot. The allegorical figures on the monthly wrapper are often ambiguous in their meaning, although the goddess Britannia, symbolic of Great Britain and British society, in the centre of the upper register, is obvious enough with her helmet, shield, and chariot. The book's title in bricks and chains makes manifest the connection between the female protagonist (centre, surrounded by the words) and the Marshalsea Prison in the Borough, immediately south of London Bridge. Two other recognizable figures are Jeremiah Flintwinch and Mrs. Clennam in her wheelchair, lower right.

Like Bleak House, Little Dorrit depends for a great part of its effectiveness upon Dickens' translation of his social vision into symbolic vision: Mrs. Clennam's paralysis, the parasitic Barnacles, and perhaps above all, the motif of the prison. The successes and failures of collaboration depend partly on Dickens' assignment of subject, and partly on Browne's execution of each subject. Like all the monthly serial novels from Nicholas Nickleby onward, this one begins with a cover design intended to embody the novel's main themes; and like Martin Chuzzlewit, Dombey and Son, and perhaps more arguably, David Copperfield and Bleak House, Little Dorrit ends in the monthly parts and thus opens in the bound edition with a complementary pair of etchings that serve both as foreshadowing and retrospective devices. The cover design is more unified than Bleak House's, and quite a bit less specific as to individual characters. In the center, Amy Dorrit stands at the outer gate of Marshalsea Prison, just having emerged from within; she stands "in a shaft of sunlight, this sunlight — which here, as in the etched title page, lends a sanctified air to Amy — comes from within the prison, and that in a sense Amy goes into a world much darker than the prison. When it is repeated on the title page, this image is in turn complemented by the novel's frontispiece.

The "political cartoon" across the top, showing the blind and halt leading a dozing Britannia with a retinue of fools and toadies, is largely the same in the drawing, but one important detail differs in the extension of this motif down the sides of the design, while others are developed more clearly in the actual woodcut. The crumbling castle tower is in the drawing, as is the man sitting precariously on top of it, a newspaper in his lap and a cloth over his eyes, oblivious of the deterioration of the building. But while in the cut the church tower is clearly ruined, with a raven (or jackdaw?) atop it, the ruin is less evident in the drawing, and on the tower we have a fat, bewigged man asleep on an enormous cushion; this looks like something out of the Bleak House cover, since the cushion is probably meant to be the woolsack, and the man a high member of the legal profession. I suspect that Dickens told Browne to remove him, as his place on the church is inappropriate. The black bird in the cut would seem to signify the general decay of Victorian society and the prevalence of death, or, if it is a jackdaw, the thievery of institutions; yet I cannot find it any more appropriate to the church. The child playing leapfrog with the gravestones, a concept we have earlier traced back to Browne's frontispiece for Godfrey Malvern, here underlines the theme of indifference and irresponsibility. One other alteration likely to have been at Dickens' insistence is the representation of Mrs. Clennam in her wheelchair, with Flintwinch standing alongside, In the drawing we see instead, from the rear, a woman in a bath chair, pushed by a man. Dickens probably wished to have a more particular representation of Arthur's mother, as she and Jeremiah have a malevolent appearance in the cut and stand out as the only other definite characters, apart from Amy.

Little Dorrit's cover is effective in conveying certain themes — decay, indifference, irresponsibility of government, and confusion — as well as foreshadowing major tonalities of the novel, such as the dark prison, Little Dorrit as central figure, and Mrs. Clennam and Flintwinch as evil genii presiding over the ramifications of the plot. Along with the Bleak House cover it is the most socially conscious of the designs, and presents its ideas more directly than its predecessor. Dickens must have supplied a good deal of direction for this wrapper, given that the date of the following letter (19 October 1855) is approximately six weeks before the publication date of Part 1:

"Will you give my address to B. and E. without loss of time, and tell them that although I have communicated at full explanation length with Browne, I have heard nothing of or from him. Will you add that I am uneasy and wish they would communicate with Mr. Young, his partner, at once. Also that I beg them to be so good as send Browne my present address?"

Wrapper for Dickens's Little Dorrit

Phiz

Commentary:

Of the novels that Dickens published serially — that is, the works of volume length that do not include the five The Christmas Books and his considerable journalistic contributions to Household Words (30 March 1850-May 1859) and All the Year Round (30 April 1859-1893) — only those issued in monthly parts were originally sold in wrappers (that is, unbound pages), although Oliver Twist is a special case in that it originally appeared as magazine fiction in Bentley's Miscellany and then was re-issued in monthly instalments in 1846 by Chapman and Hall. In a nineteen-part serialization, Little Dorrit was the ninth Dickens work to be issued in monthly wrappers (December 1855 through June 1857), the last being a "double" number with four illustrations.

The rear panel of the wrapper for Little Dorrit is of interest for its utter and complete commercial orientation, conveying the sense of Little Dorrit as a commodity text rather than a work of art; the back side of the wrapper exhorts readers to purchase products, and by implication asserts that the monthly part is a "product," too. This represents the evolution of the "advertiser" that appeared with the monthly numbers of Pickwick since it is devoted to the merchandise of William S., Burton's General Furnishing Ironmongery Warehouse in Oxford Street.

Significantly, the late paratextual critic Michael Steig in Dickens and Phiz (1978) refers to containers for bound pages of the monthly installments of Dickens's novels as "covers" rather than "wrappers," perhaps to dispel the illusion of impermanence. The former term, after all, suggests an integral part of a book, the latter (as in fish-and-chip "wrappers") as something best disposed of.

Little Dorritt and her father

Frontispiece

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Commentary:

The first illustration — "Little Dorrit and Her Father" — introduces the novel's focal characters. The dual character study is different from others in Eytinge's Diamond Edition sequences of sixteen for each volume in that it post-dates Eytinge's 1869 visit to London and Gadshill. As is typical of these studies, Eytinge appears to have in mind no particular moment in the narrative. William Dorrit, Amy's father, known as "The Father of the Marshalsea" because he has been incarcerated in that debtors' prison for so many years — twenty-five, in fact — is an amiable but utterly impractical middle-aged gentleman whom Dickens based in part upon his own father, John Dickens. Amy, William's youngest child, born in the prison, has acquired the nickname "Little Dorrit." At the time that the story opens, the industrious, self-denying Amy is about twenty-two, even though Eytinge's plate makes her look much younger.

Title-page Vignette, Little Dorrit at the door of a cell in The Marshalsea

James Mahoney

1871

Commentary:

This was the life, and this the history, of the child of the Marshalsea at twenty-two. With a still surviving attachment to the one miserable yard and block of houses as her birthplace and home, she passed to and fro in it shrinkingly now, with a womanly consciousness that she was pointed out to every one. Since she had begun to work beyond the walls, she had found it necessary to conceal where she lived, and to come and go as secretly as she could, between the free city and the iron gates, outside of which she had never slept in her life. Her original timidity had grown with this concealment, and her light step and her little figure shunned the thronged streets while they passed along them.

Worldly wise in hard and poor necessities, she was innocent in all things else. Innocent, in the mist through which she saw her father, and the prison, and the turbid living river that flowed through it and flowed on.

This was the life, and this the history, of Little Dorrit; now going home upon a dull September evening, observed at a distance by Arthur Clennam. This was the life, and this the history, of Little Dorrit; turning at the end of London Bridge, recrossing it, going back again, passing on to Saint George's Church, turning back suddenly once more, and flitting in at the open outer gate and little court-yard of the Marshalsea. — Book One, "Poverty"; Chapter 7, "The Child Of The Marshalsea."

Commentary:

Having himself been "a child of The Marshalsea" when his father was incarcerated for debt, Charles Dickens must have had a special affection for Amy Dorrit, whose father Dickens modelled closely upon his own father, John Dickens. Although the notorious debtors' prison closed in 1842, its lowering wall just off the Borough High Street in Southwark would have been familiar enough to Dickens's London readership, even when the Household Edition volume was published in 1873. The modern tourist, hunting for vestiges of the prison, will stroll by Clennam Street and Quilp Street (although Fred Quilp appears only in The Old Curiosity Shop), and pass the Church of St. George the Martyr (still known as the Little Dorrit church) before turning down Angel Place to encounter the remains of the high-walled Marshalsea, upon which he or she will Reader the following on a commemorative plaque:

Beyond this old wall is the site of the old Marshalsea Prison, closed in 1842. This sign is attached to a remnant of the prison wall. Charles Dickens, whose father had been imprisonbed here for debt in 1824, used that experience of the Marshalsea setting for his novel Little Dorrit.

How much of young Charles Dickens's intimate knowledge of that wretched pile was known to his original illustrator one can only guess, but he kept the secret of his working at the Blacking Factory at Hungerford Stairs from all but his future biographer and business agent, John Forster. However, such later illustrators as James Mahoney and Harry Furniss had the distinct advantage of having learned of Dickens's connection to the place by reading Forster's Life of Charles Dickens (3 volumes, Chapman and Hall, 1871-74).

Little Dorritt title page by Harry Furniss

Commentary:

Fin-de-siécle illustrator Harry Furniss's visual overture for the 1855-57 novel, depicting most of the fifty-four named characters, and most prominently the eponymous character, the diminutive Amy Dorrit (upper centre). Furniss's ornamental title-page is most effective for those readers already familiar with the characters and situations of the novel; moreover, many of these Picasso-esque sketches foreshadow the full-scale lithographs to come. In the upper-left-hand corner, the smoking Rigaud and his short, chubby companion (Cavaletto, or Mr. Baptist) does not foreshadow a particular plate. On the other hand, in the second vignette in the upper register Furniss is clearly utilizing The Father of the Marshalsea. In one of the most conspicuous positions in the ornamental frame, upper centre, Amy appears as she does in the facing Frontispiece and several regular illustrations.

Other characters recognizable from narrative-pictorial sequences by Furniss's predecessors, Phiz in the original, nineteen-part serialization (1855-57) and James Mahoney in the Household Edition (1873), include Jeremiah and Affery Flintwinch with Mrs. Clennam in her wheelchair (upper right); Mr. Casby, Arthur Clennam (lower right); Mr. Meagles, Tattycoram, and Miss Wade (centre left); and the memorable Maggy in her large hat holding a toasting-fork (centre left). The vignettes, numbering thirty-six, encompass both the major and minor characters of the novel, and anticipate several specific scenes. The closest approach to Furniss's ornate frame as a visual overture to the novel is Phiz's wrapper design for the novel, Cover for monthly parts, No. 7 (June 1856), which contains a myriad of symbolic figures surrounding the title and the names of author, illustrator, and publisher. However, the meaning of most of the vignettes on the wrapper (many of them allegorical, such as the Barnacles in the top register, impeding the progress of Britannia's chariot) would not have been fully apparent to most readers until well into the nineteen-month serialization.

Kim

What a treasure you have given us with the posting of the above material. I am going to go through each posting slowly and savour each.

I just wanted to let you know asap that you have made my day.

;-)

What a treasure you have given us with the posting of the above material. I am going to go through each posting slowly and savour each.

I just wanted to let you know asap that you have made my day.

;-)

Kim wrote: "How did you like this book, where does it fall on your Dickens favorite list? Just feel free to write any of your thoughts you have."

Kim wrote: "How did you like this book, where does it fall on your Dickens favorite list? Just feel free to write any of your thoughts you have."This was my last unread full-length Dickens novel! I feel sad to have finished it and have no more to come.

I'm tempted to say if it were my first unread Dickens novel, it might still be my last. What a mess of a plot! What alternately sanctimonious and irredeemable characters! But when I think about it at a little more distance, it still has some riches. There are beautifully written descriptions and good friendships: Meagles and Doyce and Clennam together are a pleasure. And I very much enjoyed the vivid cast of supporting characters: the bosom, Flora, John Chivery, Cavalletto, Fanny and Sparkler, Mr. Merdle. Behind the dreary tear-jerker main plot, there are so many riches.

Was anyone else surprised at how superfluous Pet ended up being at the end? I thought she'd merit a tragic ending of her own: murdered or at least widowed (the latter not that tragic). But nope, she just keeps on loving her worthless vicious husband, and her parents are sad about it, and that's that. I guess that's realistic. In real life she might have a better chance of coming to her senses in time, but then again, many people in similar positions don't.

Was anyone else surprised at how superfluous Pet ended up being at the end? I thought she'd merit a tragic ending of her own: murdered or at least widowed (the latter not that tragic). But nope, she just keeps on loving her worthless vicious husband, and her parents are sad about it, and that's that. I guess that's realistic. In real life she might have a better chance of coming to her senses in time, but then again, many people in similar positions don't.

Julie wrote: "Kim wrote: "How did you like this book, where does it fall on your Dickens favorite list? Just feel free to write any of your thoughts you have."

This was my last unread full-length Dickens novel!..."

Hi Julie

Yes. I too find the plot to be a mess. And to think this novel was planned out in advance. Yikes.

This was my last unread full-length Dickens novel!..."

Hi Julie

Yes. I too find the plot to be a mess. And to think this novel was planned out in advance. Yikes.

I’ve just finished reading an article in The Mudfog News, the Dickens Society Newsletter here in Toronto, that focusses on the Crimean War. From it, I think I may have found a tiny light of explanation for some of what happens in LD.

The Crimean War occurred between 1853-56. Little Dorrit was written between 1855-57. Dickens wrote several articles in Household Words concerning the Crimean War. Dickens knew Florence Nightingale and even helped pay for new laundry equipment at the Scutari Hospital. The article argues that the Victorians put a cultural significance on the idea of sacrifice and the idea of feminine service. This may partially explain the Victorian idea of the Angel in the House and the character of Amy.

The self-sacrifice of women such as Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole was seen as noble. Could this explain, at least in part, the nature and activities of Amy Dorrit? Tennyson’s ‘Charge of the Light Brigade’ speaks of British sacrifice as well. The lines “Theirs not to reason why/Theirs but to do and die” is (for better or worse) the ideal description of sacrifice.

It is suggested in the article that The Barnacles and the Circumlocution Office that Dickens so viciously attacked was directed at the bungling of the British Government during the war.

These points help me in understanding Amy and where the origins of Dickens’s development of the Circumlocution Office may have come from.

Any thoughts?

The Crimean War occurred between 1853-56. Little Dorrit was written between 1855-57. Dickens wrote several articles in Household Words concerning the Crimean War. Dickens knew Florence Nightingale and even helped pay for new laundry equipment at the Scutari Hospital. The article argues that the Victorians put a cultural significance on the idea of sacrifice and the idea of feminine service. This may partially explain the Victorian idea of the Angel in the House and the character of Amy.

The self-sacrifice of women such as Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole was seen as noble. Could this explain, at least in part, the nature and activities of Amy Dorrit? Tennyson’s ‘Charge of the Light Brigade’ speaks of British sacrifice as well. The lines “Theirs not to reason why/Theirs but to do and die” is (for better or worse) the ideal description of sacrifice.

It is suggested in the article that The Barnacles and the Circumlocution Office that Dickens so viciously attacked was directed at the bungling of the British Government during the war.

These points help me in understanding Amy and where the origins of Dickens’s development of the Circumlocution Office may have come from.

Any thoughts?

Peter wrote: "It is suggested in the article that The Barnacles and the Circumlocution Office that Dickens so viciously attacked was directed at the bungling of the British Government during the war."

Peter wrote: "It is suggested in the article that The Barnacles and the Circumlocution Office that Dickens so viciously attacked was directed at the bungling of the British Government during the war."That would help explain why the attack on bureaucracy in the book is so nationalized. As soon as Doyce leaves home, he's a hero. I thought it was odd that Dickens was presenting this as a particularly British problem and not a problem with human nature or institutions generally.

Julie wrote: "Was anyone else surprised at how superfluous Pet ended up being at the end? I thought she'd merit a tragic ending of her own: murdered or at least widowed (the latter not that tragic). But nope, sh..."

Julie wrote: "Was anyone else surprised at how superfluous Pet ended up being at the end? I thought she'd merit a tragic ending of her own: murdered or at least widowed (the latter not that tragic). But nope, sh..."I felt very sorry for her, that she seemed destined for many years of unhappy marriage.

I really enjoyed this book for some reason, despite the number of infuriating characters, tangled plot and messy ending. There were enough characters in there that I enjoyed (for different reasons) including Blandois, Fanny, Flora, Pancks, and Edmund.

Miss Wade I never understood - who was she and what were her motives ?

I'm not really a fan of sentiment in Dickens, but I was really moved by the scene when Arthur and Amy got together.

My least favourite character was Mr Dorrit - a horrible example of someone that has been rescued from penuary (through someone else's hard work) and then proceeds to behave in a patronising way to people he now sees as below him.

The parts of the book I least enjoyed were the long passages featuring the Barnacles, but I guess that was the point of them...

Very big thanks to Kim, Peter and Tristram as ever for the wonderful summaries and illustrations. They all make the books come alive.

Very big thanks to Kim, Peter and Tristram as ever for the wonderful summaries and illustrations. They all make the books come alive.

David wrote: "Very big thanks to Kim, Peter and Tristram as ever for the wonderful summaries and illustrations. They all make the books come alive."

Thanks a lot, David! :-)

Thanks a lot, David! :-)

Kim, as always, the additional material you provide gave me a lot of food for thought. I enjoyed reading about Gissing's childhood memories and I noticed that I, too, have quite vivid memories of certain illustrations going with Dickens novels, such as the caning of Squeers by our valiant Nicholas, Pip on the graveyard, and especially Mr Guppy and Mr Jobling coming across the smouldering remains of Mr Krook. Somehow, these novels cannot be separated from the accompanying illustrations!

The comment from the American newspaper set my teeth on edge. For starters, the writer must be an ignoramus if he cannot see the beauty in the first chapter, where Dickens conjures up the feeling of oppressive heat in contrast to the coolness and shade in the Marseilles prison. The prisoners may be confined but at least they are sheltered from the heat and the glaring sun: A few chapters later, we are learning about Mr Dorrit, who has come to regard his unending prison term not so much as a confinement but as a welcome way of escaping the challenges and hardships of real life. Now, may we not see the first prison scene as an instance of foreshadowing the idea that even such an experience as being in prison has, apparently, two sides? Mrs. Clennam's self-chosen prison term also has an alleged benefit going with it - namely that she can lord it over the rest of the world in terms of taking the moral high ground. At a closer sight, however, these seeming benefits prove vain and empty. So, I'd say the long introduction was justified. Apart from that, it was beautifully written, more beautifully written than by just saying it was "powerful hot". By the same token, the critic could say that all poetry could be summarized in short and easy sentences.

I couldn't find any of the countless grammar mistakes, either, the critic reproaches Dickens with, and it is telling that he does not even give one little example. Flora's lack of punctuation is a great stylistic device, and the incomprehensibility of most of what she is going on about is doubtless intended.

Neither can I agree with the critic's opinion of Mrs. Clennam, who seems like a perfectly credible character to me. There are lots of people who immure themselves in worlds of their own making, in their prejudice and their narcissm - and as to having no maternal love for Arthur, why! she is not his mother after all, and the boy was a constant remainder to her of the immense slight of her ego which lay in the fact that by her own standards, her soi-disant husband had made her a fallen woman by having married someone else before. The rightfulness of her claim to being married stands to reason, doesn't it? Of course, with her upbringing, she could never have forgiven her husband that kind of slight.

The only thing on which I agree with the critic is his assessment of Little Dorrit and her mania for self-sacrifice. Thriving on persecution like a frog does on buck-shot, I quite like that expression!

All in all, however, this review seems to me to confirm an aphorism by Arno Schmidt, who said, "A reviewer sometimes strikes me as the man who watches a cloud and resents it for not taking the shape of the camel he sees in the mirror every day."

The comment from the American newspaper set my teeth on edge. For starters, the writer must be an ignoramus if he cannot see the beauty in the first chapter, where Dickens conjures up the feeling of oppressive heat in contrast to the coolness and shade in the Marseilles prison. The prisoners may be confined but at least they are sheltered from the heat and the glaring sun: A few chapters later, we are learning about Mr Dorrit, who has come to regard his unending prison term not so much as a confinement but as a welcome way of escaping the challenges and hardships of real life. Now, may we not see the first prison scene as an instance of foreshadowing the idea that even such an experience as being in prison has, apparently, two sides? Mrs. Clennam's self-chosen prison term also has an alleged benefit going with it - namely that she can lord it over the rest of the world in terms of taking the moral high ground. At a closer sight, however, these seeming benefits prove vain and empty. So, I'd say the long introduction was justified. Apart from that, it was beautifully written, more beautifully written than by just saying it was "powerful hot". By the same token, the critic could say that all poetry could be summarized in short and easy sentences.

I couldn't find any of the countless grammar mistakes, either, the critic reproaches Dickens with, and it is telling that he does not even give one little example. Flora's lack of punctuation is a great stylistic device, and the incomprehensibility of most of what she is going on about is doubtless intended.

Neither can I agree with the critic's opinion of Mrs. Clennam, who seems like a perfectly credible character to me. There are lots of people who immure themselves in worlds of their own making, in their prejudice and their narcissm - and as to having no maternal love for Arthur, why! she is not his mother after all, and the boy was a constant remainder to her of the immense slight of her ego which lay in the fact that by her own standards, her soi-disant husband had made her a fallen woman by having married someone else before. The rightfulness of her claim to being married stands to reason, doesn't it? Of course, with her upbringing, she could never have forgiven her husband that kind of slight.

The only thing on which I agree with the critic is his assessment of Little Dorrit and her mania for self-sacrifice. Thriving on persecution like a frog does on buck-shot, I quite like that expression!

All in all, however, this review seems to me to confirm an aphorism by Arno Schmidt, who said, "A reviewer sometimes strikes me as the man who watches a cloud and resents it for not taking the shape of the camel he sees in the mirror every day."

Julie wrote: "That would help explain why the attack on bureaucracy in the book is so nationalized. As soon as Doyce leaves home, he's a hero. I thought it was odd that Dickens was presenting this as a particularly British problem and not a problem with human nature or institutions generally."

Frankly speaking, I could never understand why Dickens lambasted his own country with a tendency to prevent progress and change. After all, Britain was the workshop of the world in the 19th century, the forerunner of industrialization when Germany and France were still rather traditional societies in economic and scientific terms. They turned out more inventions than other European countries clubbed together in those decades. Therefore, if a man like Doyce would thrive and be listened to anywhere in Europe, it would have been in England.

Frankly speaking, I could never understand why Dickens lambasted his own country with a tendency to prevent progress and change. After all, Britain was the workshop of the world in the 19th century, the forerunner of industrialization when Germany and France were still rather traditional societies in economic and scientific terms. They turned out more inventions than other European countries clubbed together in those decades. Therefore, if a man like Doyce would thrive and be listened to anywhere in Europe, it would have been in England.

My favourite characters in this novel are

1) Mr F.'s aunt - She must be putting on much of her quirky behaviour, or else she could not have seen through Clennam so easily,

2) Flora - minus her volubility,

3) Miss Wade - as a literary creation, not as a person to live with,

4) Mrs Clennam - for the same reasons I liked reading about Miss Wade.

5) Fanny - for the same reasons Julie named.

I was annoyed by Clennam and all the Dorrits, with the exception of Fanny, and those boring Barnacles as well as by the smug Meagles. I don't know if Dickens intended this, but Mr. Meagles's aversion to picking up any bits of the languages spoken in the countries he travels, and being even proud of that obtuseness, is a good sign of his smugness. It would never even occur to me to go into a country without at least trying to learn some of the language (both as an effort of politeness and for the sake of expanding my horizons).

1) Mr F.'s aunt - She must be putting on much of her quirky behaviour, or else she could not have seen through Clennam so easily,

2) Flora - minus her volubility,

3) Miss Wade - as a literary creation, not as a person to live with,

4) Mrs Clennam - for the same reasons I liked reading about Miss Wade.

5) Fanny - for the same reasons Julie named.

I was annoyed by Clennam and all the Dorrits, with the exception of Fanny, and those boring Barnacles as well as by the smug Meagles. I don't know if Dickens intended this, but Mr. Meagles's aversion to picking up any bits of the languages spoken in the countries he travels, and being even proud of that obtuseness, is a good sign of his smugness. It would never even occur to me to go into a country without at least trying to learn some of the language (both as an effort of politeness and for the sake of expanding my horizons).

Peter wrote: "I’ve just finished reading an article in The Mudfog News, the Dickens Society Newsletter here in Toronto, that focusses on the Crimean War. From it, I think I may have found a tiny light of explana..."

I think that the historical background you are providing here is quite useful to understand the Victorians' obsession with self-sacrifice, but when we take a closer look at Dickens's novels, we will find that nearly each of them vaunts self-denial, subservience and sacrifice in female (and sometimes male) characters. It seems as though Dickens was obsessed with women who didn't mind being trampled on.

They say that our society is rife with narcissm, and that may be true to a certain extent. Nevertheless, the Covid crisis has shown to me that the appeal to self-denial and forebearance still hits its mark, which I find quite dangerous - if I may say so - because it enables governments to wean us from our basic rights. I don't want to open up such a discussion here, but, on a more general level, I think that the praise of self-sacrifice and renunciation may become a dangerous thing because it empowers governments and weakens individuals. Can we not say that the wars that ravaged Europe and the world in the 20th century (and before) were partly made possible by a culture that taught people to sacrifice themselves for a common good, for their nation or their beliefs?

I hope I am not a narcissist but whenever people are in a frenzy of "solidarity" and virtue, I rather stand back and watch, asking myself the old question of cui bono?

I think that the historical background you are providing here is quite useful to understand the Victorians' obsession with self-sacrifice, but when we take a closer look at Dickens's novels, we will find that nearly each of them vaunts self-denial, subservience and sacrifice in female (and sometimes male) characters. It seems as though Dickens was obsessed with women who didn't mind being trampled on.

They say that our society is rife with narcissm, and that may be true to a certain extent. Nevertheless, the Covid crisis has shown to me that the appeal to self-denial and forebearance still hits its mark, which I find quite dangerous - if I may say so - because it enables governments to wean us from our basic rights. I don't want to open up such a discussion here, but, on a more general level, I think that the praise of self-sacrifice and renunciation may become a dangerous thing because it empowers governments and weakens individuals. Can we not say that the wars that ravaged Europe and the world in the 20th century (and before) were partly made possible by a culture that taught people to sacrifice themselves for a common good, for their nation or their beliefs?

I hope I am not a narcissist but whenever people are in a frenzy of "solidarity" and virtue, I rather stand back and watch, asking myself the old question of cui bono?

Tristram wrote: "All in all, however, this review seems to me to confirm an aphorism by Arno Schmidt, who said, "A reviewer sometimes strikes me as the man who watches a cloud and resents it for not taking the shape of the camel he sees in the mirror every day." "

Tristram wrote: "All in all, however, this review seems to me to confirm an aphorism by Arno Schmidt, who said, "A reviewer sometimes strikes me as the man who watches a cloud and resents it for not taking the shape of the camel he sees in the mirror every day." "This is me, Tristram. I've criticized more than one author for writing a story that went one way when I wanted it to go another. I do not suffer disappointment quietly. :)

Today is catch-up day, and I hardly know where to start. Forgive me if I repeat myself or seem to disregard others' comments, which is certainly not intentional.

Today is catch-up day, and I hardly know where to start. Forgive me if I repeat myself or seem to disregard others' comments, which is certainly not intentional.This is my 3rd reading of Dorrit. The first time, I loved it, and counted it among my favorites by Dickens. With each subsequent reading, I find more to dislike. I blame (or credit, if you prefer) all of you, in part, as you are so good with your analysis, and pointing out things I glossed over! For example, I don't think I gave much thought to the age difference between Arthur and Amy at first. Now, I seem to only be able to think of Arthur as a replacement in Amy's affections for William, which makes me feel a little creepy.

I'm relieved, though, that others seem befuddled by the whole thing with Frederick, the will, etc. So often I think I'm just not reading carefully enough. While there's relief that perhaps I'm not as dumb as I feel, there's also disappointment that Dickens didn't seem to think this thing through as well as he might. How could he have improved it? He wasn't one for prologues, but perhaps that contrivance, showing William and Frederick as young men, would have given the reader a little historical context. We would have learned that they were, indeed, wealthy gentlemen, and could have maybe seen Frederick's philanthropic actions towards Arthur's real mother, etc. As it is, so much came out of the blue. Frederick seemed absolutely unnecessary through most of the novel.

Favorite characters? I've always had a soft spot for dear Flora, whose life just didn't turn out as she'd hoped, and yet she soldiers on with good humor and a warm heart. Losing her first love, losing Mr. Finching so early, and being saddled for life as the caretaker of his bitter (though entertaining) old aunt... well, she's a trouper, no doubt about it. I daresay if I were to run into an old beau, I would probably babble too much and make a fool of myself, as well. Some of us aren't blessed with self-confidence, particularly after having put on a few pounds over the years.

While I truly despise Miss Wade, I find her character fascinating. I do wish we could have learned about her through some other means than the letter she, herself penned to Arthur, which was entirely unrealistic. It's a shame that Arthur or Meagles couldn't have somehow run into her old employers or charges, in their search for Tattycoram, for example, who could have shed some light on her. I doubt anyone who is truly like Miss Wade would be a) so self-aware, and b) so willing to open up about it.

Unlike Tristram, I found Meagles' jingoistic attitude affectionately amusing -- on the page. In real life, I'm sure it would make me crazy. Same with Mrs. Plornish and her attempts at Italian, i.e. yelling at Cavaletto in broken English. Despite their limited world view and other faults, they were decent people.

Like Julie, I also appreciated the friendship between Doyce, Clennam, and Meagles. Throw Pancks and Cavaletto in there, as well.

In my first reading, I couldn't stand the Barnacles and the Merdle chapters. This time around, I got a lot more out of them. They're less important to the overall plot, but the prose can be a joy to behold.

How do you think Blandois rates as a Dickens villain? He reminded me a bit of Sir John Chester in Barnaby Rudge. No madness, like Bradley Headstone or Bill Sikes -- just pure evil in those soft, white hands.

There was a LOT going on in this novel, and whole story lines could have been omitted without it really changing the overall plot, e.g. the Meagles and the Gowans. There was little reason for us to all travel through the Swiss Alps together. There was little reason for Tip's existence at all! Ah, well. Little Dorrit just doesn't stand up to Bleak House, which has such a tight, well-executed plot in which all the peripheral characters and sub-plots seem relevant to the overall story.

Thanks, Peter, for the information on the Crimean War, Florence Nightengale, etc. It really does give us a broader perspective. Try as we might, I suppose we'll never truly be able to understand Victorian literature as people at the time would have. I see this in my own lifetime; younger people trying to interpret, for example, life before the internet, or life before 9/11. Having never been there, try as they might, they can never know exactly how things were, and can only see history through their own limited experiences, which can be a dangerous thing. Even being cognizant of that, it's still very hard for me not to judge Amy's self-sacrificing subservience.

Tristram wrote: "I think that the historical background you are providing here is quite useful to understand the Victorians' obsession with self-sacrifice....They say that our society is rife with narcissm, and that may be true to a certain extent...."

Tristram wrote: "I think that the historical background you are providing here is quite useful to understand the Victorians' obsession with self-sacrifice....They say that our society is rife with narcissm, and that may be true to a certain extent...."I'm sympathetic to the idea that I live in a society that's too individualistic, so I've been mulling over why I find Dickens's self-sacrificing characters so annoying.

Ultimately I think it's because they're not actually sacrificing anything. Amy has no desires other than serving other people. She is clearly unhappy when her father doesn't need her, because she has no interests of her own. So there's nothing noble about her so-called self-sacrifice. She's like a little vampire of suffering, living off of other people's needs. I find this neither realistic nor admirable.

Interesting insight, Julie. When Amy really COULD have sacrificed, by accepting John, she wouldn't do it. Compare Amy to Louisa Gradgrind, for example, who married Bounderby for her ungrateful brother.

Interesting insight, Julie. When Amy really COULD have sacrificed, by accepting John, she wouldn't do it. Compare Amy to Louisa Gradgrind, for example, who married Bounderby for her ungrateful brother.

Mary Lou wrote: "Interesting insight, Julie. When Amy really COULD have sacrificed, by accepting John, she wouldn't do it. Compare Amy to Louisa Gradgrind, for example, who married Bounderby for her ungrateful brot..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Interesting insight, Julie. When Amy really COULD have sacrificed, by accepting John, she wouldn't do it. Compare Amy to Louisa Gradgrind, for example, who married Bounderby for her ungrateful brot..."Exactly! I love Louisa.

What was the purpose of the repeated references to the white hands of Blandois ? What was it meant to tell us ?

What was the purpose of the repeated references to the white hands of Blandois ? What was it meant to tell us ?

For me it was the second time reading this book, and I liked it better this time. The whole 'hey, there are more people thinking about these things and finding them strange' actually helped with that.

I too am in the camp of people who disliked William Dorrit the most. Amy herself was high on the list too, I couldn't help screaming in my head: 'come on girl, grow a spine already!!!' - but all the same, I disliked old Dorrit all the same and even more for her sake. He raised his child to be a doormat, and then gladly wiped his feet on her back unless he could have them propped up and clean all day. To him she was no more than an asset, something he could use to give them more standing through a good marriage - either to John Chivery when they were poor, or to God knows who when they were rich - while she took care of his needs. Because he deserved it because he happened to be her father. I really, really, really see no redeeming traits in that man.

And Flora is amazing in how big her heart is, as well as for taking care of the aunt.

While I agree that the whole Meagles-pet-Gowan-Tattycoram-Miss Wade part was superfluous, I think it also gave us some insight in the characters we actually followed. They gave us insight in how different Amy and Fanny react to a stranger who is supposed to be wealthy/important enough to be interested in (while Pet and Gowan are poor compared to them, he has family connections while she has wealthy parents after all). Miss Wade was the most useless of all though.

I think Blandois' hands might have to do with them being clean. He is the one who all the time washes his hands in innocense, so that they always appear to be clean and not used for anything that can put a blemish on them. That's my little theory, I am curious if anyone has a different idea!

I too am in the camp of people who disliked William Dorrit the most. Amy herself was high on the list too, I couldn't help screaming in my head: 'come on girl, grow a spine already!!!' - but all the same, I disliked old Dorrit all the same and even more for her sake. He raised his child to be a doormat, and then gladly wiped his feet on her back unless he could have them propped up and clean all day. To him she was no more than an asset, something he could use to give them more standing through a good marriage - either to John Chivery when they were poor, or to God knows who when they were rich - while she took care of his needs. Because he deserved it because he happened to be her father. I really, really, really see no redeeming traits in that man.

And Flora is amazing in how big her heart is, as well as for taking care of the aunt.

While I agree that the whole Meagles-pet-Gowan-Tattycoram-Miss Wade part was superfluous, I think it also gave us some insight in the characters we actually followed. They gave us insight in how different Amy and Fanny react to a stranger who is supposed to be wealthy/important enough to be interested in (while Pet and Gowan are poor compared to them, he has family connections while she has wealthy parents after all). Miss Wade was the most useless of all though.

I think Blandois' hands might have to do with them being clean. He is the one who all the time washes his hands in innocense, so that they always appear to be clean and not used for anything that can put a blemish on them. That's my little theory, I am curious if anyone has a different idea!

Mary Lou wrote: "Today is catch-up day, and I hardly know where to start. Forgive me if I repeat myself or seem to disregard others' comments, which is certainly not intentional.

This is my 3rd reading of Dorrit. ..."

The question that plagues me most is how much I am missing because I am so far chronologically removed from the Victorian times. How many words have subtly changed their meanings in the past two centuries, how many visual cues and references are casually made by Dickens who knew his readers could easily understand his meanings while I frantically scramble to decode his meaning. In terms of geography, when Dickens mentions a landmark, a street name, a food or drink, even a type of clothing how much am I unable to decode the meaning that a Victorian would grasp in a second.

Mary Lou, you are right. Consider our own times. 9/11, Neil Armstrong walking on the moon, the Viet Nam War, heck, the phenomenon of the British Invasion and The Beatles. These events have little or no context to many reader’s today. How do each of us put into context that which we never experienced?

If I was allowed one frivolous wish I think it would be to be able to read a 19c novel with a 19c mind. I often wonder how different the experience would be.

This is my 3rd reading of Dorrit. ..."

The question that plagues me most is how much I am missing because I am so far chronologically removed from the Victorian times. How many words have subtly changed their meanings in the past two centuries, how many visual cues and references are casually made by Dickens who knew his readers could easily understand his meanings while I frantically scramble to decode his meaning. In terms of geography, when Dickens mentions a landmark, a street name, a food or drink, even a type of clothing how much am I unable to decode the meaning that a Victorian would grasp in a second.

Mary Lou, you are right. Consider our own times. 9/11, Neil Armstrong walking on the moon, the Viet Nam War, heck, the phenomenon of the British Invasion and The Beatles. These events have little or no context to many reader’s today. How do each of us put into context that which we never experienced?

If I was allowed one frivolous wish I think it would be to be able to read a 19c novel with a 19c mind. I often wonder how different the experience would be.

Since Dickens is my favorite author of all time, I gave this book a 5 rating. As usual, I enjoyed that Dickens digs at his society by pointing out the scams (who does this for us?) and the situation of the unbelievable poverty. We have such poverty today, I just read that one in seven children does not have enough to eat in the US.