The Old Curiosity Club discussion

A Tale of Two Cities

>

Book 2 Chapters 1-6

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Book 2 Chapter 2

Sight

“Over the prisoner’s head there was a mirror to throw light down upon him.”

In this chapter we find ourselves in the Old Bailey Law Court where Jerry is waiting for instructions from Mr Lorry. There is a case of treason on the docket. A guilty conviction would mean “quartering” which is a rather messy punishment I need not describe in detail. What I will point out is the fact that the person, before he is tried for treason, will, in all probability, have already been found guilty. All Jerry does know is that he has no idea why Mr Lorry is in the court. The courtroom is buzzing with people who are eagerly awaiting the guilty verdict. There is one exception. He is a “wigged gentleman” who was staring at the ceiling.

The man on trial is named Charles Darnay. He is described as being “well-grown and well-looking.” Darnay carries himself like a gentleman. We learn that Darnay has pleaded not guilty to the charges of treason but he knows that everyone in the courtroom was already mentally hanging, beheading, and quartering him. The prisoner looks up to the ceiling and sees a mirror. Darnay is conscious “of a bar of light across his face … and when he saw the mirror his face flushed.” Darnay notices two people in the courtroom who turn out to be Lucie Manette and her father. Now, what are they doing in the courtroom? Why would they be witnesses against the man accused of treason? This chapter, like chapter one, moves quickly. Both chapters are brief and pose many more questions than they answer. As readers, we want to read on.

Thoughts

I mentioned that in this novel, because it was published in weekly parts, most chapters will be shorter, and the plot, characters, and even literary devices employed will all be somewhat compressed. Note that we are told again about Jerry’s rusty fingers. Here is one focus that Dickens wants us to be constantly aware of but for what reason we will have to wait and see. Ah, suspense and foreshadowing. Take your pick.

Did you note how this chapter firmly establishes that the death sentences of the guilty in the English court system are very brutal in nature. It appears everyone is found guilty. To what extent do you think Dickens was exaggerating? Why would Dickens point out the brutality of the English court system?

We read in this chapter that both Charles Darnay and a yet unnamed lawyer both look at the ceiling of the courthouse. Darnay sees a reflection of himself in a ceiling mirror but we are not told what the lawyer is looking at. Still, two men, in the same courtroom, what might be the purpose of them staring at the ceiling? Mirrors reflect the objects in their field of view. I suggest we keep alert to the presence of mirrors in this novel. Dickens will use mirrors to advance the plot and act as symbols to help us understand motifs in the novel.

The title of this chapter is “A Sight.” What is it that you see in this chapter? I wonder what it is we are meant to look at? What is it that the two men see as they look up at the ceiling?

Sight

“Over the prisoner’s head there was a mirror to throw light down upon him.”

In this chapter we find ourselves in the Old Bailey Law Court where Jerry is waiting for instructions from Mr Lorry. There is a case of treason on the docket. A guilty conviction would mean “quartering” which is a rather messy punishment I need not describe in detail. What I will point out is the fact that the person, before he is tried for treason, will, in all probability, have already been found guilty. All Jerry does know is that he has no idea why Mr Lorry is in the court. The courtroom is buzzing with people who are eagerly awaiting the guilty verdict. There is one exception. He is a “wigged gentleman” who was staring at the ceiling.

The man on trial is named Charles Darnay. He is described as being “well-grown and well-looking.” Darnay carries himself like a gentleman. We learn that Darnay has pleaded not guilty to the charges of treason but he knows that everyone in the courtroom was already mentally hanging, beheading, and quartering him. The prisoner looks up to the ceiling and sees a mirror. Darnay is conscious “of a bar of light across his face … and when he saw the mirror his face flushed.” Darnay notices two people in the courtroom who turn out to be Lucie Manette and her father. Now, what are they doing in the courtroom? Why would they be witnesses against the man accused of treason? This chapter, like chapter one, moves quickly. Both chapters are brief and pose many more questions than they answer. As readers, we want to read on.

Thoughts

I mentioned that in this novel, because it was published in weekly parts, most chapters will be shorter, and the plot, characters, and even literary devices employed will all be somewhat compressed. Note that we are told again about Jerry’s rusty fingers. Here is one focus that Dickens wants us to be constantly aware of but for what reason we will have to wait and see. Ah, suspense and foreshadowing. Take your pick.

Did you note how this chapter firmly establishes that the death sentences of the guilty in the English court system are very brutal in nature. It appears everyone is found guilty. To what extent do you think Dickens was exaggerating? Why would Dickens point out the brutality of the English court system?

We read in this chapter that both Charles Darnay and a yet unnamed lawyer both look at the ceiling of the courthouse. Darnay sees a reflection of himself in a ceiling mirror but we are not told what the lawyer is looking at. Still, two men, in the same courtroom, what might be the purpose of them staring at the ceiling? Mirrors reflect the objects in their field of view. I suggest we keep alert to the presence of mirrors in this novel. Dickens will use mirrors to advance the plot and act as symbols to help us understand motifs in the novel.

The title of this chapter is “A Sight.” What is it that you see in this chapter? I wonder what it is we are meant to look at? What is it that the two men see as they look up at the ceiling?

Chapter 3

A Disappointment

… the crowd came pouring out with a vehemence that nearly took him off his legs, and a buzz swept into the street as if the baffled blue-flies were dispersing in search of other carrion.”

For a bit of a change I am going to open this commentary at the very end of chapter three. The above words are the last words of the chapter. In those few words we find the result of the trial, the effect of the result of the trial on the onlookers, and a comparison of people who attend the court to flies in search of carrion. The public does not come to court to see Justice in action; rather they come to witness the first steps towards a human being being brutally put to death. We need to remember this of the British court system of the time.

The court case depends on two witnesses and some documents that the accused man had in his possession. The first man is John Barsad. He is a very unreliable chap, but since he claims to be a patriot that is all that matters to the court. The second witness is a man by the name of Roger Cly. He was, at one time, a servant to the accused, but in reality he was a spy against Darnay and had frequently gone through Darnay’s personal effects . Cly admitted to knowing John Barsad for 7 or 8 years. Both Barsad and Cly claim to be patriots of the highest order.

Next to the stand was Mr Lorry. Under a circuitous and rambling examination, Lorry reveals that he was on a boat from France to England with Lucie and her father Doctor Manette. This leads to Lucie being called to the stand. Lucie states that Charles Darnay acted like a gentleman, offered to comfort her father, and discussed briefly how Britain’s quarrel with America was foolish. Dr Manette then takes the stand. At this point we get more background on him. We learn, for instance, that he had been imprisoned in France for a long time and that his memory of past events is vague.

We now must consider the lawyer who spends all his time looking at the ceiling. At one point in the trial he throws a piece of paper to Mr Stryver, Darnay’s lawyer. Stryver then presents his case. Stryver states that Barsad is a traitor and Cly is a spy, Cly is equally untrustworthy, and the reason for Darnay’s trips to France were merely to attend to the affairs of his family as Darnay is of French extraction.

The key to Darnay’s defence occurs when Stryver draws the attention of the court to the fact that Darnay looks remarkably similar to the lawyer who continually stares at the ceiling. The resemblance is so striking that ultimately the jury cannot convict Darnay. As well as recognizing that Darnay looks like Sydney Carton (the man who is staring at the ceiling) Carton is the first person to observe that Lucie felt faint. Carton called the attention of others to this fact. Evidently, looking at the ceiling did not distract Carton from noticing his resemblance to Darnay or Lucie’s swoon. There must be more to this man than his seeming disinterest to his surroundings.

We read that Carton and Darnay stood “side by side, both reflected in the glass above them.” Here again we have Dickens incorporating a reference to a mirror. Carton and Darnay look alike and their similar reflections are captured by a mirror above them. What can this possibly mean, possibly suggest, possibly foreshadow? There must be a reason Dickens describes these two men as being very similar in appearance. As a point of interest, Dickens’s friend Wilkie Collins published his novel The Woman in White in Dickens’s journal “All the Year Round” in 1859. Collins’ novel has two woman characters who look remarkable similar.

The jury returns the verdict of “acquitted” to which Jerry Cruncher comments “if you had sent the message ‘Recalled to Life,’ again … I should have known what you meant, this time.” And so the chapter ends with yet another reference to being recalled to life. I wonder how many ways and forms a person can be recalled to life. I think this novel will tell us as we continue to read it.

A Disappointment

… the crowd came pouring out with a vehemence that nearly took him off his legs, and a buzz swept into the street as if the baffled blue-flies were dispersing in search of other carrion.”

For a bit of a change I am going to open this commentary at the very end of chapter three. The above words are the last words of the chapter. In those few words we find the result of the trial, the effect of the result of the trial on the onlookers, and a comparison of people who attend the court to flies in search of carrion. The public does not come to court to see Justice in action; rather they come to witness the first steps towards a human being being brutally put to death. We need to remember this of the British court system of the time.

The court case depends on two witnesses and some documents that the accused man had in his possession. The first man is John Barsad. He is a very unreliable chap, but since he claims to be a patriot that is all that matters to the court. The second witness is a man by the name of Roger Cly. He was, at one time, a servant to the accused, but in reality he was a spy against Darnay and had frequently gone through Darnay’s personal effects . Cly admitted to knowing John Barsad for 7 or 8 years. Both Barsad and Cly claim to be patriots of the highest order.

Next to the stand was Mr Lorry. Under a circuitous and rambling examination, Lorry reveals that he was on a boat from France to England with Lucie and her father Doctor Manette. This leads to Lucie being called to the stand. Lucie states that Charles Darnay acted like a gentleman, offered to comfort her father, and discussed briefly how Britain’s quarrel with America was foolish. Dr Manette then takes the stand. At this point we get more background on him. We learn, for instance, that he had been imprisoned in France for a long time and that his memory of past events is vague.

We now must consider the lawyer who spends all his time looking at the ceiling. At one point in the trial he throws a piece of paper to Mr Stryver, Darnay’s lawyer. Stryver then presents his case. Stryver states that Barsad is a traitor and Cly is a spy, Cly is equally untrustworthy, and the reason for Darnay’s trips to France were merely to attend to the affairs of his family as Darnay is of French extraction.

The key to Darnay’s defence occurs when Stryver draws the attention of the court to the fact that Darnay looks remarkably similar to the lawyer who continually stares at the ceiling. The resemblance is so striking that ultimately the jury cannot convict Darnay. As well as recognizing that Darnay looks like Sydney Carton (the man who is staring at the ceiling) Carton is the first person to observe that Lucie felt faint. Carton called the attention of others to this fact. Evidently, looking at the ceiling did not distract Carton from noticing his resemblance to Darnay or Lucie’s swoon. There must be more to this man than his seeming disinterest to his surroundings.

We read that Carton and Darnay stood “side by side, both reflected in the glass above them.” Here again we have Dickens incorporating a reference to a mirror. Carton and Darnay look alike and their similar reflections are captured by a mirror above them. What can this possibly mean, possibly suggest, possibly foreshadow? There must be a reason Dickens describes these two men as being very similar in appearance. As a point of interest, Dickens’s friend Wilkie Collins published his novel The Woman in White in Dickens’s journal “All the Year Round” in 1859. Collins’ novel has two woman characters who look remarkable similar.

The jury returns the verdict of “acquitted” to which Jerry Cruncher comments “if you had sent the message ‘Recalled to Life,’ again … I should have known what you meant, this time.” And so the chapter ends with yet another reference to being recalled to life. I wonder how many ways and forms a person can be recalled to life. I think this novel will tell us as we continue to read it.

Chapter 4

Congratulatory

“[Doctor Manette’s] face had become frozen, as if it were, in a very curious look at Darnay: an intent look, deepening into a frown of dislike and distrust, not even unmixed with fear … “

Our chapter begins with Dr Manette, Lucie, Mr Lorry, Stryver, Sydney Carton and Charles Darnay huddled together congratulating Darnay and his escape from death. Here again, we find the concept of being recalled to life being played out. Darnay will live to greet another day. Dickens then focuses on Lucie Manette and we learn how she is “the golden thread” that holds and loves her father so securely. Lucie is described as an Angel, as a person who can reach beyond her father’s misery. Her voice, the light in her face, the touch of her hand, her golden hair and blue eyes all combine to give her angelic qualities. Lucie is a light in the world, a world that has too much darkness, both in England and in France.

We also learn that Stryver is a bully with more than a touch of arrogance. Dickens once again reinforces the fact that Mr Lorry is a man of business. Does anyone want to count the number of times Mr Lorry refers to the fact he is a man of business? OK, I thought not. Dr Manette’s physical appearance alters greatly at one point in this chapter which I indicated in the epigraph above. How can we possibly account for this change in demeanour? What could upset him so much?

As the group disperses Dickens makes a comment that the Old Bailey will be deserted until tomorrow when people’s interest in “gallows, whipping-post, and branding-iron should re-people it.” How do we account for this seemingly unnecessary comment?

Mr Lorry and Sydney Carton exchange a few words. Only a few. Mr Lorry is a man of business while Carton admits to being not much of anything. And so off Lorry goes to Tellson’s. This leaves Sydney Carton and Charles Darnay together in the street. Carton says to Darnay “This is a strange chance that throws you and me together. This must be a strange night to you, standing alone here with your counterpart on these street stones?” Do you recall these men recently looking up to the ceiling, and Darnay’s reflection in the mirror looking down? And here we see something similar. This is a “short” Dickens novel. It is more compact. We can see his ideas, his symbols, his creatively much more closely. What is going on here between these seemingly so different men in character, if not different appearance? They decide to dine together. Sydney proposes a toast and tells Darnay that the object of Darnay’s toast is on “the tip of your tongue.” And so the toast is made to none other than Lucie Manette. Carton then asks Darnay “is it worth being tried for one’s life, to be the object of such sympathy and compassion?”

Darnay, always the gentleman, is much different from Carton, who is a “disagreeable companion.” As they part after dinner Carton defines his own personality as “a disappointed drudge … . I care for no man on earth, and no man on earth cares for me.” Darnay’s response is “Much to be regretted. You might have used your talents better.”

As our chapter ends we find Carton at home where he takes up a candle and looks into a mirror. There, he inspects himself closely. Caron realizes that what he has in common with Darnay is his appearance. Carton further realizes that Darnay “shows [Carton] what you have fallen away from, and what you might have been. Change places with him, and would you have been looked at by those blue eyes as he was …” Carton drinks more wine and slumps over his table. Beside him “a long winding-sheet in the candle [dripped] down upon him.” The appearance of a mirror again! Let’s make a note of that!

There is so much in these last sentences. We know that Sydney and Charles look alike, and we learn that both find Lucie Manette attractive. Carton knows that one like Lucie would never find him as attractive as Charles Darnay. As Sydney falls asleep in a drunken state the candle beside him forms a winding sheet, a shroud of death.

Thoughts

What might Dickens be signalling to his readers?

Congratulatory

“[Doctor Manette’s] face had become frozen, as if it were, in a very curious look at Darnay: an intent look, deepening into a frown of dislike and distrust, not even unmixed with fear … “

Our chapter begins with Dr Manette, Lucie, Mr Lorry, Stryver, Sydney Carton and Charles Darnay huddled together congratulating Darnay and his escape from death. Here again, we find the concept of being recalled to life being played out. Darnay will live to greet another day. Dickens then focuses on Lucie Manette and we learn how she is “the golden thread” that holds and loves her father so securely. Lucie is described as an Angel, as a person who can reach beyond her father’s misery. Her voice, the light in her face, the touch of her hand, her golden hair and blue eyes all combine to give her angelic qualities. Lucie is a light in the world, a world that has too much darkness, both in England and in France.

We also learn that Stryver is a bully with more than a touch of arrogance. Dickens once again reinforces the fact that Mr Lorry is a man of business. Does anyone want to count the number of times Mr Lorry refers to the fact he is a man of business? OK, I thought not. Dr Manette’s physical appearance alters greatly at one point in this chapter which I indicated in the epigraph above. How can we possibly account for this change in demeanour? What could upset him so much?

As the group disperses Dickens makes a comment that the Old Bailey will be deserted until tomorrow when people’s interest in “gallows, whipping-post, and branding-iron should re-people it.” How do we account for this seemingly unnecessary comment?

Mr Lorry and Sydney Carton exchange a few words. Only a few. Mr Lorry is a man of business while Carton admits to being not much of anything. And so off Lorry goes to Tellson’s. This leaves Sydney Carton and Charles Darnay together in the street. Carton says to Darnay “This is a strange chance that throws you and me together. This must be a strange night to you, standing alone here with your counterpart on these street stones?” Do you recall these men recently looking up to the ceiling, and Darnay’s reflection in the mirror looking down? And here we see something similar. This is a “short” Dickens novel. It is more compact. We can see his ideas, his symbols, his creatively much more closely. What is going on here between these seemingly so different men in character, if not different appearance? They decide to dine together. Sydney proposes a toast and tells Darnay that the object of Darnay’s toast is on “the tip of your tongue.” And so the toast is made to none other than Lucie Manette. Carton then asks Darnay “is it worth being tried for one’s life, to be the object of such sympathy and compassion?”

Darnay, always the gentleman, is much different from Carton, who is a “disagreeable companion.” As they part after dinner Carton defines his own personality as “a disappointed drudge … . I care for no man on earth, and no man on earth cares for me.” Darnay’s response is “Much to be regretted. You might have used your talents better.”

As our chapter ends we find Carton at home where he takes up a candle and looks into a mirror. There, he inspects himself closely. Caron realizes that what he has in common with Darnay is his appearance. Carton further realizes that Darnay “shows [Carton] what you have fallen away from, and what you might have been. Change places with him, and would you have been looked at by those blue eyes as he was …” Carton drinks more wine and slumps over his table. Beside him “a long winding-sheet in the candle [dripped] down upon him.” The appearance of a mirror again! Let’s make a note of that!

There is so much in these last sentences. We know that Sydney and Charles look alike, and we learn that both find Lucie Manette attractive. Carton knows that one like Lucie would never find him as attractive as Charles Darnay. As Sydney falls asleep in a drunken state the candle beside him forms a winding sheet, a shroud of death.

Thoughts

What might Dickens be signalling to his readers?

Chapter 5

The Jackal

“he threw himself down in his clothes on a neglected bed, and its pillow was wet with wasted tears.”

A jackal is not the most cuddly, cute, or huggable of animals. In fact, they are rather horrid both in looks and actions. I would not want to be associated with or compared to a jackal.

In this chapter we learn that Stryver and Carton are partners of a sort. They are a rather curious pair. Stryver is a bold, brash, unscrupulous man, full of confidence and full of himself. Carton, on the other hand, is, on the surface at least, a wastrel and a drunk. He has no pride in himself or his appearance. What is the dynamic that attracts these men to each other?

We read that Stryver “never had a case in hand, anywhere, but Carton was there, with his hands in his pocket, staring at the ceiling of the court.” It seems that Stryver is the one who is the visual and verbal presence in the courtroom but Sydney is the one with the superior legal mind. Stryver calls Sydney ‘Memory,” a word that suggests Sydney has not only a great capacity to drink but also has the ability to intake and recall vast amounts of legal information and tactics. Carton and Stryver share a meal but it is Carton who serves Stryver. After dinner their conversation turns to the day’s events, and, ultimately, to Lucie Manette the “golden-haired doll.” Carton leaves Stryver’s home and makes his way to his own poor residence where he falls on his bed and weeps.

Reflections

The chapter title is “The Jackal.” On the surface, it appears that the title must refer to Sydney Carton. Carton is without pride, feels no sense of self-worth, and appears to be in the service of Mr Stryver both in the court and during their dinner. Sydney is a jackal who gets no respect. He only receives scrapes of acknowledgement for both his work in court and at Stryver’s dinner table. To me, I think the title is ironic. I think Dickens is suggesting that Stryver is the jackal. It is Stryver who feeds off Sidney’s superior legal mind. It is Stryver who uses Sydney’s emotional weaknesses for his own ill-deserved gains. Who do you think the title of this chapter refers to?

The Jackal

“he threw himself down in his clothes on a neglected bed, and its pillow was wet with wasted tears.”

A jackal is not the most cuddly, cute, or huggable of animals. In fact, they are rather horrid both in looks and actions. I would not want to be associated with or compared to a jackal.

In this chapter we learn that Stryver and Carton are partners of a sort. They are a rather curious pair. Stryver is a bold, brash, unscrupulous man, full of confidence and full of himself. Carton, on the other hand, is, on the surface at least, a wastrel and a drunk. He has no pride in himself or his appearance. What is the dynamic that attracts these men to each other?

We read that Stryver “never had a case in hand, anywhere, but Carton was there, with his hands in his pocket, staring at the ceiling of the court.” It seems that Stryver is the one who is the visual and verbal presence in the courtroom but Sydney is the one with the superior legal mind. Stryver calls Sydney ‘Memory,” a word that suggests Sydney has not only a great capacity to drink but also has the ability to intake and recall vast amounts of legal information and tactics. Carton and Stryver share a meal but it is Carton who serves Stryver. After dinner their conversation turns to the day’s events, and, ultimately, to Lucie Manette the “golden-haired doll.” Carton leaves Stryver’s home and makes his way to his own poor residence where he falls on his bed and weeps.

Reflections

The chapter title is “The Jackal.” On the surface, it appears that the title must refer to Sydney Carton. Carton is without pride, feels no sense of self-worth, and appears to be in the service of Mr Stryver both in the court and during their dinner. Sydney is a jackal who gets no respect. He only receives scrapes of acknowledgement for both his work in court and at Stryver’s dinner table. To me, I think the title is ironic. I think Dickens is suggesting that Stryver is the jackal. It is Stryver who feeds off Sidney’s superior legal mind. It is Stryver who uses Sydney’s emotional weaknesses for his own ill-deserved gains. Who do you think the title of this chapter refers to?

Chapter 6

Hundreds of People

“There is a great crowd bearing down upon us, Miss Manette, and I see them! — by the Lightning … and I hear them! he added again … . Here they come, fast, fierce, and furious!”

Dickens gave over 470 public readings during his lifetime. I am unsure how many included excerpts from A Tale of Two Cities but I find this chapter particularly suitable to be read aloud. What do you think? Any volunteers?

The chapter begins with us learning that 4 months have passed since Darnay’s trial. Mr Lorry continues his friendship with Dr Manette and Lucie. They spend Sundays together. We are told that Dr Manette and Lucie live in a quaint and quiet corner of London. It is a place of peace. It is a place of “echoes, and a very harbour from the raging streets.” Doctor Manette has resumed his medical practice, and Lucie is as beautiful as ever, but wait! In this idyllic house Doctor Manette has kept his “disused shoemaker’s bench and tray of tools.” Why?

Lucie’s maid, a delightfully eccentric woman named Miss Pross, tells Mr Lorry that dozens of people who are “not at all worthy” come looking for Lucie. Actually, Miss Pross says it's “hundreds” of people. Lorry knows that Miss Pross is a jealous woman. In Miss Pross we have another example of an overprotective servant. Can you recall such a dynamic in earlier novels? As we read on we will find that Miss Pross will give some much needed levity to the novel. I think we will find, however, that the humour we find in Miss Pross will be rather dark in nature. Have you noticed that our most recent novels have become darker in nature, almost to the point of lacking humour at all? Mr Pickwick, where are you?

Miss Pross tells Mr Lorry that the only person worthy of Lucie is her brother Solomon “if he hadn’t made a mistake in life.” Solomon is evidently a total scoundrel who has left Miss Pross in complete poverty.

Mr Lorry asks Miss Pross whether Dr Manette has any idea or recollection of the name of the person who caused his imprisonment. Pross has some suspicion that Lucie may know. Pross also reveals that it is better to leave the past in the past since Dr Manette is very sensitive to his long incarceration. Since Manette still keeps his shoemaker’s bench and tools it is also evident that he has not buried his past. If so, of course, this means that Dr Manette’s past may well be recalled to life. Ah, there’s that theme again!

Hundreds of people do not come to Sunday dinner as Miss Pross claimed. One does, and that is Charles Darnay who tells a story about some alterations in the Tower of London. Evidently workers found the letters DIC in a dungeon. They then realized the letters were DIG which they did. They found “the ashes of a paper, mingled with the ashes of a small leathern case or bag.” This story causes an enormous response in Dr Manette. He recovers almost immediately and suggests the group go inside as it is raining.

Let’s pause. … Dr Manette was in jail for a very long time. In this chapter we have discovered the fact that Dr Manette still keeps his shoemaker’s bench in his room. Lucie, we learn, has suspicions her father has some recollections of his traumatic past. Add to this the discussion of a jail cell with the letters DIG and the discovery of some buried paper cause Dr Manette to violently react for a moment. And then it begins to rain. Dickens loves to use pathetic fallacy (when the elements of nature reflect the emotions of humans). Dickens appears to be giving his readers some hints as to the unfolding plot, but how to connect them? Let’s now add the fact that Mr Lorry’s eyes “detected, or fancied they detected, on [Dr Manette’s] face , as it turned towards Charles Darnay, the same singular look that had been upon it when it turned towards [Darnay] in the passage of the Court House.” Again, Dr Manette recovered quickly, but something is definitely in the wind. What do you think?

We read that Sydney Carton also comes for tea this same evening. The raindrops keep coming, keep intensifying. Lucie tells the assembled group that she sometimes hears footsteps and believes they are coming “into our lives.” More footsteps, more echoes, more rain. The suspense continues to build. At one point Sydney Carton says of the footsteps “Here they come, fast, fierce, and furious.”

There is both a literal storm and a psychological storm swirling around the group. Darnay, Carton, Pross, Lucie, Dr Manette. What is the storm? Where will it be? And, most importantly perhaps, when? As the chapter ends Mr Lorry says to Sydney “Good-night, Mr Carton … . Shall we ever see such a night again, together.” And then the narrator speaks the final words “Perhaps, perhaps, see the great crowd of people with its rush and roar, bearing down upon them, too.”

Thoughts

There is much to decode in this chapter. As a weekly publication we can see in this chapter how Dickens incorporates suspense and foreshadowing to propel the narrative forward. What part(s) of this chapter did you enjoy most? What is the one question you would like answered?

Do you recall how Dickens emphasized the tranquility of the Manette home in the beginning of this chapter? How should we reconcile the tranquil beginning of the chapter to the chapter’s tumultuous ending?

Hundreds of People

“There is a great crowd bearing down upon us, Miss Manette, and I see them! — by the Lightning … and I hear them! he added again … . Here they come, fast, fierce, and furious!”

Dickens gave over 470 public readings during his lifetime. I am unsure how many included excerpts from A Tale of Two Cities but I find this chapter particularly suitable to be read aloud. What do you think? Any volunteers?

The chapter begins with us learning that 4 months have passed since Darnay’s trial. Mr Lorry continues his friendship with Dr Manette and Lucie. They spend Sundays together. We are told that Dr Manette and Lucie live in a quaint and quiet corner of London. It is a place of peace. It is a place of “echoes, and a very harbour from the raging streets.” Doctor Manette has resumed his medical practice, and Lucie is as beautiful as ever, but wait! In this idyllic house Doctor Manette has kept his “disused shoemaker’s bench and tray of tools.” Why?

Lucie’s maid, a delightfully eccentric woman named Miss Pross, tells Mr Lorry that dozens of people who are “not at all worthy” come looking for Lucie. Actually, Miss Pross says it's “hundreds” of people. Lorry knows that Miss Pross is a jealous woman. In Miss Pross we have another example of an overprotective servant. Can you recall such a dynamic in earlier novels? As we read on we will find that Miss Pross will give some much needed levity to the novel. I think we will find, however, that the humour we find in Miss Pross will be rather dark in nature. Have you noticed that our most recent novels have become darker in nature, almost to the point of lacking humour at all? Mr Pickwick, where are you?

Miss Pross tells Mr Lorry that the only person worthy of Lucie is her brother Solomon “if he hadn’t made a mistake in life.” Solomon is evidently a total scoundrel who has left Miss Pross in complete poverty.

Mr Lorry asks Miss Pross whether Dr Manette has any idea or recollection of the name of the person who caused his imprisonment. Pross has some suspicion that Lucie may know. Pross also reveals that it is better to leave the past in the past since Dr Manette is very sensitive to his long incarceration. Since Manette still keeps his shoemaker’s bench and tools it is also evident that he has not buried his past. If so, of course, this means that Dr Manette’s past may well be recalled to life. Ah, there’s that theme again!

Hundreds of people do not come to Sunday dinner as Miss Pross claimed. One does, and that is Charles Darnay who tells a story about some alterations in the Tower of London. Evidently workers found the letters DIC in a dungeon. They then realized the letters were DIG which they did. They found “the ashes of a paper, mingled with the ashes of a small leathern case or bag.” This story causes an enormous response in Dr Manette. He recovers almost immediately and suggests the group go inside as it is raining.

Let’s pause. … Dr Manette was in jail for a very long time. In this chapter we have discovered the fact that Dr Manette still keeps his shoemaker’s bench in his room. Lucie, we learn, has suspicions her father has some recollections of his traumatic past. Add to this the discussion of a jail cell with the letters DIG and the discovery of some buried paper cause Dr Manette to violently react for a moment. And then it begins to rain. Dickens loves to use pathetic fallacy (when the elements of nature reflect the emotions of humans). Dickens appears to be giving his readers some hints as to the unfolding plot, but how to connect them? Let’s now add the fact that Mr Lorry’s eyes “detected, or fancied they detected, on [Dr Manette’s] face , as it turned towards Charles Darnay, the same singular look that had been upon it when it turned towards [Darnay] in the passage of the Court House.” Again, Dr Manette recovered quickly, but something is definitely in the wind. What do you think?

We read that Sydney Carton also comes for tea this same evening. The raindrops keep coming, keep intensifying. Lucie tells the assembled group that she sometimes hears footsteps and believes they are coming “into our lives.” More footsteps, more echoes, more rain. The suspense continues to build. At one point Sydney Carton says of the footsteps “Here they come, fast, fierce, and furious.”

There is both a literal storm and a psychological storm swirling around the group. Darnay, Carton, Pross, Lucie, Dr Manette. What is the storm? Where will it be? And, most importantly perhaps, when? As the chapter ends Mr Lorry says to Sydney “Good-night, Mr Carton … . Shall we ever see such a night again, together.” And then the narrator speaks the final words “Perhaps, perhaps, see the great crowd of people with its rush and roar, bearing down upon them, too.”

Thoughts

There is much to decode in this chapter. As a weekly publication we can see in this chapter how Dickens incorporates suspense and foreshadowing to propel the narrative forward. What part(s) of this chapter did you enjoy most? What is the one question you would like answered?

Do you recall how Dickens emphasized the tranquility of the Manette home in the beginning of this chapter? How should we reconcile the tranquil beginning of the chapter to the chapter’s tumultuous ending?

Somehow from these chapters I got the feeling that Pross is right in not trusting all those men in Miss Manette's life - men that were hardly there five years ago, and miss Mannette and Pross did well enough taking care of each other. On the other hand Pross is not the best person to judge men's characters, as fond as she seems to be of her brother. I now wonder if the brother will come back later. Somehow I remember even less of reading ATOTC than I remember of Little Dorrit. I don't know what kind of reading I did way back when ...

The court case was great in its imagery and symbolism, but I did find all of the 'thats' very hard to get through. It was a huge relief when those were finally over. Still, the looking at the ceiling, the mirror and Carton and Darnay being so alike, I loved it! I got the clear idea of them being each other's mirror image. They might be the same in looks, but they might end up totally opposite in more ways than we now know. I once read a story in a YA horror short story book about good people looking in the mirror who got sucked in, and their mirror counterpart took over, because they were bored from only coming in action to copy the real person. And the mirror persons were the complete opposite of the real persons, especially character-wise. I don't know the clue of the story anymore, but this part reminded me of that story.

The court case was great in its imagery and symbolism, but I did find all of the 'thats' very hard to get through. It was a huge relief when those were finally over. Still, the looking at the ceiling, the mirror and Carton and Darnay being so alike, I loved it! I got the clear idea of them being each other's mirror image. They might be the same in looks, but they might end up totally opposite in more ways than we now know. I once read a story in a YA horror short story book about good people looking in the mirror who got sucked in, and their mirror counterpart took over, because they were bored from only coming in action to copy the real person. And the mirror persons were the complete opposite of the real persons, especially character-wise. I don't know the clue of the story anymore, but this part reminded me of that story.

Jantine wrote: "Somehow from these chapters I got the feeling that Pross is right in not trusting all those men in Miss Manette's life - men that were hardly there five years ago, and miss Mannette and Pross did w..."

Hi Jantine

Miss Pross is a wonderful character. No spoilers of course, but she delivers one of the greatest lines in all of Dickens (well, to my way of thought anyway) near the end of the book. I will certainly point it out when we get that far.

Yes. Isn’t the use of the mirror symbolism wonderful? It is done so subtly, and yet the use of the mirrors goes to the very heart and essence of the novel. I think after the recurring concept of being recalled to life, the significance of mirrors is the central motif of the novel.

Hi Jantine

Miss Pross is a wonderful character. No spoilers of course, but she delivers one of the greatest lines in all of Dickens (well, to my way of thought anyway) near the end of the book. I will certainly point it out when we get that far.

Yes. Isn’t the use of the mirror symbolism wonderful? It is done so subtly, and yet the use of the mirrors goes to the very heart and essence of the novel. I think after the recurring concept of being recalled to life, the significance of mirrors is the central motif of the novel.

Here is a wonderful link to a Malcolm Andrews talk on Dickens’s use of mirrors in his novels. While he does not dwell on TTC there is much to discover in his talk.

Enjoy.

https://youtu.be/7PgdMFx5kWU

Enjoy.

https://youtu.be/7PgdMFx5kWU

Jantine wrote: "Somehow from these chapters I got the feeling that Pross is right in not trusting all those men in Miss Manette's life - men that were hardly there five years ago, and miss Mannette and Pross did w..."

I think Miss Pross a very interesting character, all the more so since she is clearly meant as a mere supporting character: She seems to be more self-confident and energetic than her young mistress, and, a bit like David Copperfield's aunt, inclined not to think too well of men in general. Her behaviour is even to much of a challenge to a businesslike man like Mr. Lorry, who meets her with well-advised meekness.

She is clearly jealous of Darnay and of Carton and wants to have Lucie all to herself. According to her, even Lucie's father is not good enough for his daughter, which leads me to the question what Lucie has done to merit such an amount of admiration - other than being the typical Dickens heroine, a passive goody-two-shoes.

With regard to her brother, however, Miss Pross is wilfully blind. It stands to reason how she would react if her brother actually turned up and expressed an interest in Lucie.

By the way, did you notice that Dr. Manette is not quite at ease in Darnay's company? I wonder why this is the case, and I also wonder why on earth that strange story about the prisoner in the Tower was brought up. There was nothing really that led straight up to it.

I think Miss Pross a very interesting character, all the more so since she is clearly meant as a mere supporting character: She seems to be more self-confident and energetic than her young mistress, and, a bit like David Copperfield's aunt, inclined not to think too well of men in general. Her behaviour is even to much of a challenge to a businesslike man like Mr. Lorry, who meets her with well-advised meekness.

She is clearly jealous of Darnay and of Carton and wants to have Lucie all to herself. According to her, even Lucie's father is not good enough for his daughter, which leads me to the question what Lucie has done to merit such an amount of admiration - other than being the typical Dickens heroine, a passive goody-two-shoes.

With regard to her brother, however, Miss Pross is wilfully blind. It stands to reason how she would react if her brother actually turned up and expressed an interest in Lucie.

By the way, did you notice that Dr. Manette is not quite at ease in Darnay's company? I wonder why this is the case, and I also wonder why on earth that strange story about the prisoner in the Tower was brought up. There was nothing really that led straight up to it.

The title of the last chapter, "Hundreds of People", was really well-chosen, wasn't it? On the surface, it seems to refer to Miss Pross's use of hyperbole in order to express her displeasure with Darney and Carton as friends of the household - by the way, did they ever explain how Carton found his way into the confidence of the Manettes?

On another level, the title links well with the motif of the echoing steps, who clearly bode doom for some of the people listening to the thunder and the storm in the Manette household. The steps also reminded me of the Ghost Walk in Bleak House, and the ominous talk of the characters and the comments of the narrator on the echo of the steps was redolent of Miss Wade, who said that those people who will affect your life one day, in Miss Wade's universe exclusively in a negative manner, of course, are already on their way. That's quite pessimistic and fatalistic.

On another level, the title links well with the motif of the echoing steps, who clearly bode doom for some of the people listening to the thunder and the storm in the Manette household. The steps also reminded me of the Ghost Walk in Bleak House, and the ominous talk of the characters and the comments of the narrator on the echo of the steps was redolent of Miss Wade, who said that those people who will affect your life one day, in Miss Wade's universe exclusively in a negative manner, of course, are already on their way. That's quite pessimistic and fatalistic.

Tristram wrote: "The title of the last chapter, "Hundreds of People", was really well-chosen, wasn't it? On the surface, it seems to refer to Miss Pross's use of hyperbole in order to express her displeasure with D..."

Yes. Footsteps and doom. A touch of the Gothic for us in the novel. There may be more to come.

Yes. Footsteps and doom. A touch of the Gothic for us in the novel. There may be more to come.

Peter wrote: "Book II Chapters 1-6

Peter wrote: "Book II Chapters 1-6Chapter 1

Five Years Later

“Mr Cruncher betook himself to his boot-cleaning and his general preparations for business.”

Thank you for sharing your personal journey with A Tale. It is inspiring.

Hello Curiosities

Here we are with another Dickens..."

Peter wrote: "Chapter 4

Peter wrote: "Chapter 4Congratulatory

“[Doctor Manette’s] face had become frozen, as if it were, in a very curious look at Darnay: an intent look, deepening into a frown of dislike and distrust, not even unmi..."

Was anyone else relieved, as I was, with Darnay's acquittal? Not having read A Tale before that was a revelation to me.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 5

Peter wrote: "Chapter 5The Jackal

“he threw himself down in his clothes on a neglected bed, and its pillow was wet with wasted tears.”

A jackal is not the most cuddly, cute, or huggable of animals. In fact, ..."

I agree I took Stryver to be the jackal.

Peter wrote: "Jantine wrote: "Somehow from these chapters I got the feeling that Pross is right in not trusting all those men in Miss Manette's life - men that were hardly there five years ago, and miss Mannette..."

Peter wrote: "Jantine wrote: "Somehow from these chapters I got the feeling that Pross is right in not trusting all those men in Miss Manette's life - men that were hardly there five years ago, and miss Mannette..."Having a challenge figuring out who Miss Pross is and what her role in this story is. Any thoughts or direction? thank you.

Hi Francis

Miss Pross is Lucie’s maid. To date we have seen that she is also Lucie’s companion and seemingly only female friend. She is very loyal to Lucie and is, it appears, more than a little jealous that anyone else may be of interest to Lucie.

As I mentioned preciously she also has one of the great lines (to me, anyway) in all of Dickens’s novels but we will have to wait until near the end of the novel to discover what they are.

Miss Pross is Lucie’s maid. To date we have seen that she is also Lucie’s companion and seemingly only female friend. She is very loyal to Lucie and is, it appears, more than a little jealous that anyone else may be of interest to Lucie.

As I mentioned preciously she also has one of the great lines (to me, anyway) in all of Dickens’s novels but we will have to wait until near the end of the novel to discover what they are.

Peter wrote: "Hi Francis

Peter wrote: "Hi FrancisMiss Pross is Lucie’s maid. To date we have seen that she is also Lucie’s companion and seemingly only female friend. She is very loyal to Lucie and is, it appears, more than a little j..."

Thanks Peter. This helps.

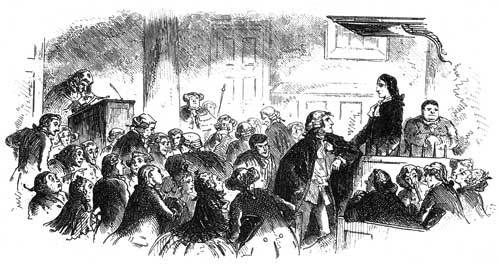

The Likeness

Book II Chapter 3

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Mr. Carton, who had so long sat looking at the ceiling of the court, changed neither his place nor his attitude, even in this excitement. While his learned friend, Mr. Stryver, massing his papers before him, whispered with those who sat near, and from time to time glanced anxiously at the jury; while all the spectators moved more or less, and grouped themselves anew; while even my Lord himself arose from his seat, and slowly paced up and down his platform, not unattended by a suspicion in the minds of the audience that his state was feverish; this one man sat leaning back, with his torn gown half off him, his untidy wig put on just as it had happened to light on his head after its removal, his hands in his pockets, and his eyes on the ceiling as they had been all day. Something especially reckless in his demeanour, not only gave him a disreputable look, but so diminished the strong resemblance he undoubtedly bore to the prisoner (which his momentary earnestness, when they were compared together, had strengthened), that many of the lookers-on, taking note of him now, said to one another they would hardly have thought the two were so alike. Mr. Cruncher made the observation to his next neighbour, and added, "I'd hold half a guinea that he don't get no law-work to do. Don't look like the sort of one to get any, do he?"

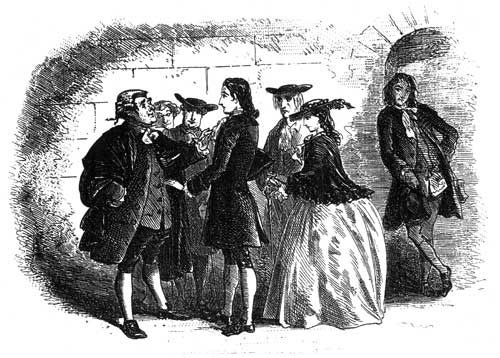

Congratulations

Book II Chapter 4

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"From the dimly-lighted passages of the court, the last sediment of the human stew that had been boiling there all day, was straining off, when Doctor Manette, Lucie Manette, his daughter, Mr. Lorry, the solicitor for the defence, and its counsel, Mr. Stryver, stood gathered round Mr. Charles Darnay—just released—congratulating him on his escape from death.

It would have been difficult by a far brighter light, to recognise in Doctor Manette, intellectual of face and upright of bearing, the shoemaker of the garret in Paris. Yet, no one could have looked at him twice, without looking again: even though the opportunity of observation had not extended to the mournful cadence of his low grave voice, and to the abstraction that overclouded him fitfully, without any apparent reason. While one external cause, and that a reference to his long lingering agony, would always—as on the trial—evoke this condition from the depths of his soul, it was also in its nature to arise of itself, and to draw a gloom over him, as incomprehensible to those unacquainted with his story as if they had seen the shadow of the actual Bastille thrown upon him by a summer sun, when the substance was three hundred miles away.

Only his daughter had the power of charming this black brooding from his mind. She was the golden thread that united him to a Past beyond his misery, and to a Present beyond his misery: and the sound of her voice, the light of her face, the touch of her hand, had a strong beneficial influence with him almost always. Not absolutely always, for she could recall some occasions on which her power had failed; but they were few and slight, and she believed them over.

Mr. Darnay had kissed her hand fervently and gratefully, and had turned to Mr. Stryver, whom he warmly thanked. Mr. Stryver, a man of little more than thirty, but looking twenty years older than he was, stout, loud, red, bluff, and free from any drawback of delicacy, had a pushing way of shouldering himself (morally and physically) into companies and conversations, that argued well for his shouldering his way up in life.

He still had his wig and gown on, and he said, squaring himself at his late client to that degree that he squeezed the innocent Mr. Lorry clean out of the group: "I am glad to have brought you off with honour, Mr. Darnay. It was an infamous prosecution, grossly infamous; but not the less likely to succeed on that account."

"You have laid me under an obligation to you for life—in two senses," said his late client, taking his hand.

"I have done my best for you, Mr. Darnay; and my best is as good as another man's, I believe."

It clearly being incumbent on some one to say, "Much better," Mr. Lorry said it; perhaps not quite disinterestedly, but with the interested object of squeezing himself back again.

"You think so?" said Mr. Stryver. "Well! you have been present all day, and you ought to know. You are a man of business, too."

"And as such," quoth Mr. Lorry, whom the counsel learned in the law had now shouldered back into the group, just as he had previously shouldered him out of it—"as such I will appeal to Doctor Manette, to break up this conference and order us all to our homes. Miss Lucie looks ill, Mr. Darnay has had a terrible day, we are worn out."

"Speak for yourself, Mr. Lorry," said Stryver; "I have a night's work to do yet. Speak for yourself."

Commentary:

The third and fourth plates, for July, "The Likeness" and "Congratulations," repeat the small- scale/large-scale dichotomy of the first number's illustrations. In "The Likeness," Elizabeth Cayzer in The Dickensian 1986, speculates upon the reason behind Browne's departing from Dickens's text:

Sydney Carton is asked to "lay aside his wig" (Book II, chapter 3) in order that his appearance may be compared with that of Charles Darnay. The artist sensibly leaves Carton with his wig on, in the plate illustrating the scene, as his contribution to the tension caused for the surprised on-lookers.

The courtroom is in uproar, according to Browne, even prior to the instruction by the presiding magistrate (extreme left, looking at his documents while the rest of the court regards the remarkable facial similarity between Darnay, in the dock and at the same height as the magistrate, and Carton on the floor of the court) that his learned friend to lay aside his wig to verify the likeness. This realisation is, in fact, not a deviation from the written text, but a demonstration of how carefully Browne has read that text. The judgment that Browne has exercised is evident in his choosing to depict both their facial likeness and their different roles: the prisoner (in profile only) is in the dock, guarded and behind a row of confining spikes; however, the attorney (face in profile, but body turned to reveal the full figure), in casual pose, hand on his hip, is self-possessed, at ease, and free. Finally, on a level with the accused is reader's analogue, the magistrate, who, receiving competing histories of events on that night in November 1775, must sort out who is telling the truth and what that truth is. Only later will we apprehend one further continuing character in the mêlée: the mysterious figure immediately behind Carton.

In both plates of the second number, Carton is alienated: in "The Likeness," he is detached from the others in the court by being depicted almost head-to-foot, slightly right of center, and dividing the jurymen in their box from the rest of the group scene of swirling action; in the stasis of "Congratulations," Carton is socially isolated more obviously from the main group, leaning aloofly right-rear, the casualness of the pose again suggestive of a nature "slovenly if not debauched" (Book II, Chapter 3). Here, however, the similarity in dress (and therefore social class) between attorney and client becomes much more obvious since Browne has placed Darnay center, and drawn him head-to-foot in knee-stockings, breeches, and trim frock-coat.

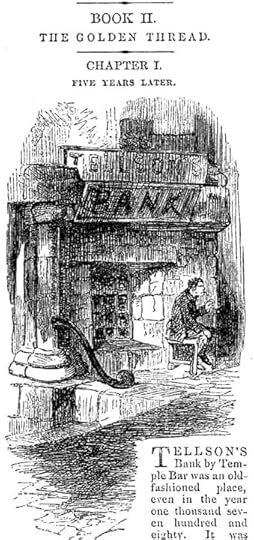

Headnote vignette

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 1, "Five Years Later"

Harper's Weekly (June 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"Outside Tellson's — never by any means in it, unless called in — was an odd-job-man, an occasional porter and messenger, who served as the live sign of the house. He was never absent during business hours, unless upon an errand, and then he was represented by his son: a grisly urchin of twelve, who was his express image. People understood that Tellson's, in a stately way, tolerated the odd-job-man. The house had always tolerated some person in that capacity, and time and tide had drifted this person to the post. His surname was Cruncher, and on the youthful occasion of his renouncing by proxy the works of darkness, in the easterly parish church of Hounsditch, he had received the added appellation of Jerry."

"You're at it again, are you?"

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 1, "Five Years Later"

Harper's Weekly June 1859

Text Illustrated:

"Mr. Cruncher's apartments were not in a savoury neighbourhood, and were but two in number, even if a closet with a single pane of glass in it might be counted as one. But they were very decently kept. Early as it was, on the windy March morning, the room in which he lay abed was already scrubbed throughout; and between the cups and saucers arranged for breakfast, and the lumbering deal table, a very clean white cloth was spread.

Mr. Cruncher reposed under a patchwork counterpane, like a Harlequin at home. At first, he slept heavily, but, by degrees, began to roll and surge in bed, until he rose above the surface, with his spiky hair looking as if it must tear the sheets to ribbons. At which juncture, he exclaimed, in a voice of dire exasperation:

"Bust me, if she ain't at it agin!"

A woman of orderly and industrious appearance rose from her knees in a corner, with sufficient haste and trepidation to show that she was the person referred to.

"What!" said Mr. Cruncher, looking out of bed for a boot. "You're at it agin, are you?"

After hailing the mom with this second salutation, he threw a boot at the woman as a third. It was a very muddy boot, and may introduce the odd circumstance connected with Mr. Cruncher's domestic economy, that, whereas he often came home after banking hours with clean boots, he often got up next morning to find the same boots covered with clay.

"What," said Mr. Cruncher, varying his apostrophe after missing his mark — "what are you up to, Aggerawayter?"

"I was only saying my prayers."

Headnote vignette

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 3, "A Disappointment"

Harper's Weekly (June 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"Mr. Carton, who had so long sat looking at the ceiling of the court, changed neither his place nor his attitude, even in this excitement. While his teamed friend, Mr. Stryver, massing his papers before him, whispered with those who sat near, and from time to time glanced anxiously at the jury; while all the spectators moved more or less, and grouped themselves anew; while even my Lord himself arose from his seat, and slowly paced up and down his platform, not unattended by a suspicion in the minds of the audience that his state was feverish; this one man sat leaning back, with his torn gown half off him, his untidy wig put on just as it had happened to fight on his head after its removal, his hands in his pockets, and his eyes on the ceiling as they had been all day. Something especially reckless in his demeanour, not only gave him a disreputable look, but so diminished the strong resemblance he undoubtedly bore to the prisoner (which his momentary earnestness, when they were compared together, had strengthened), that many of the lookers-on, taking note of him now, said to one another they would hardly have thought the two were so alike."

"The prisoner and his double"

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 3, "A Disappointment"

Harper's Weekly June 1859

Text Illustrated:

"A singular circumstance then arose in the case. The object in hand being to show that the prisoner went down, with some fellow-plotter untracked, in the Dover mail on that Friday night in November five years ago, and got out of the mail in the night, as a blind, at a place where he did not remain, but from which he travelled back some dozen miles or more, to a garrison and dockyard, and there collected information; a witness was called to identify him as having been at the precise time required, in the coffee-room of an hotel in that garrison-and-dockyard town, waiting for another person. The prisoner's counsel was cross-examining this witness with no result, except that he had never seen the prisoner on any other occasion, when the wigged gentleman who had all this time been looking at the ceiling of the court, wrote a word or two on a little piece of paper, screwed it up, and tossed it to him. Opening this piece of paper in the next pause, the counsel looked with great attention and curiosity at the prisoner.

"You say again you are quite sure that it was the prisoner?"

The witness was quite sure.

"Did you ever see anybody very like the prisoner?"

Not so like (the witness said) as that he could be mistaken.

"Look well upon that gentleman, my learned friend there," pointing to him who had tossed the paper over, "and then look well upon the prisoner. How say you? Are they very like each other?"

Allowing for my learned friend's appearance being careless and slovenly if not debauched, they were sufficiently like each other to surprise, not only the witness, but everybody present, when they were thus brought into comparison. My Lord being prayed to bid my learned friend lay aside his wig, and giving no very gracious consent, the likeness became much more remarkable. My Lord inquired of Mr. Stryver (the prisoner's counsel), whether they were next to try Mr. Carton (name of my learned friend) for treason? But, Mr. Stryver replied to my Lord, no; but he would ask the witness to tell him whether what happened once, might happen twice; whether he would have been so confident if he had seen this illustration of his rashness sooner, whether he would be so confident, having seen it; and more. The upshot of which, was, to smash this witness like a crockery vessel, and shiver his part of the case to useless lumber."

Headnote Vignette

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 4, "Congratulatory"

Harper's Weekly ( June 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"When he was left alone, this strange being took up a candle, went to a glass that hung against the wall, and surveyed himself minutely in it.

"'Do you particularly like the man?' he muttered, at his own image; 'why should you particularly like a man who resembles you? There is nothing in you to like; you know that. Ah, confound you! What a change you have made in yourself! A good reason for taking to a man, that he shows you what you have fallen away from, and what you might have been! Change places with him, and would you have been looked at by those blue eyes as he was, and commiserated by that agitated face as he was? Come on, and have it out in plain words! You hate the fellow.'

"He resorted to his pint of wine for consolation, drank it all in a few minutes, and fell asleep on his arms, with his hair straggling over the table, and a long winding-sheet in the candle dripping down upon him."

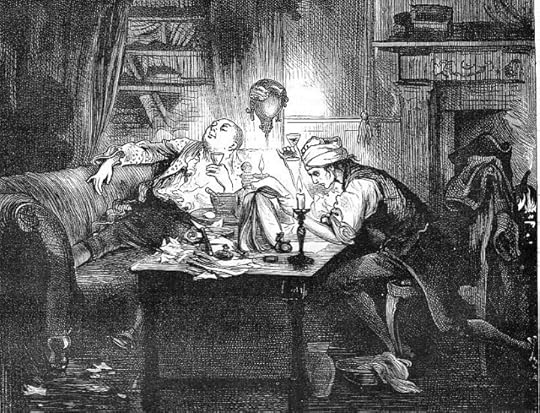

The Lion and the Jackal

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 5, "Jackal"

Harper's Weekly (June 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"Those were drinking days, and most men drank hard. So very great is the improvement Time has brought about in such habits, that a moderate statement of the quantity of wine and punch which one man would swallow in the course of a night, without any detriment to his reputation as a perfect gentleman, would seem, in these days, a ridiculous exaggeration. The learned profession of the law was certainly not behind any other learned profession in its Bacchanalian propensities; neither was Mr. Stryver, already fast shouldering his way to a large and lucrative practice, behind his compeers in this particular, any more than in the drier parts of the legal race.

A favourite at the Old Bailey, and eke at the Sessions, Mr. Stryver had begun cautiously to hew away the lower staves of the ladder on which he mounted. Sessions and Old Bailey had now to summon their favourite, specially, to their longing arms; and shouldering itself towards the visage of the Lord Chief Justice in the Court of King's Bench, the florid countenance of Mr. Stryver might be daily seen, bursting out of the bed of wigs, like a great sunflower pushing its way at the sun from among a rank garden-full of flaring companions.

It had once been noted at the Bar, that while Mr. Stryver was a glib man, and an unscrupulous, and a ready, and a bold, he had not that faculty of extracting the essence from a heap of statements, which is among the most striking and necessary of the advocate's accomplishments. But, a remarkable improvement came upon him as to this. The more business he got, the greater his power seemed to grow of getting at its pith and marrow; and however late at night he sat carousing with Sydney Carton, he always had his points at his fingers' ends in the morning.

Sydney Carton, idlest and most unpromising of men, was Stryver's great ally. What the two drank together, between Hilary Term and Michaelmas, might have floated a king's ship. Stryver never had a case in hand, anywhere, but Carton was there, with his hands in his pockets, staring at the ceiling of the court; they went the same Circuit, and even there they prolonged their usual orgies late into the night, and Carton was rumoured to be seen at broad day, going home stealthily and unsteadily to his lodgings, like a dissipated cat. At last, it began to get about, among such as were interested in the matter, that although Sydney Carton would never be a lion, he was an amazingly good jackal, and that he rendered suit and service to Stryver in that humble capacity."

Headnote Vignette

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 6, "Hundreds of People"

Harper's Weekly (June 1859)

"Miss Pross and Mr. Lorry"

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 6, "Hundreds of People"

Harper's Weekly (June 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"I don't want dozens of people who are not at all worthy of Ladybird, to come here looking after her," said Miss Pross.

"Do dozens come for that purpose?"

"Hundreds," said Miss Pross.

It was characteristic of this lady (as of some other people before her time and since) that whenever her original proposition was questioned, she exaggerated it.

"Dear me!" said Mr. Lorry, as the safest remark he could think of.

"I have lived with the darling—or the darling has lived with me, and paid me for it; which she certainly should never have done, you may take your affidavit, if I could have afforded to keep either myself or her for nothing—since she was ten years old. And it's really very hard," said Miss Pross.

Not seeing with precision what was very hard, Mr. Lorry shook his head; using that important part of himself as a sort of fairy cloak that would fit anything.

"All sorts of people who are not in the least degree worthy of the pet, are always turning up," said Miss Pross. "When you began it—"

"I began it, Miss Pross?"

"Didn't you? Who brought her father to life?"

"Oh! If that was beginning it—" said Mr. Lorry."

Messrs. Cruncher and Son

Book II Chapter 1

Fred Barnard

Dickens A Tale of Two Cities The Household Edition 1870s

Text Illustrated:

"Outside Tellson's — never by any means in it, unless called in — was an odd-job-man, an occasional porter and messenger, who served as the live sign of the house. He was never absent during business hours, unless upon an errand, and then he was represented by his son: a grisly urchin of twelve, who was his express image. People understood that Tellson's, in a stately way, tolerated the odd-job-man. The House had always tolerated some person in that capacity, and time and tide had drifted this person to the post. His surname was Cruncher, and on the youthful occasion of his renouncing by proxy the works of darkness, in the easterly parish church of Houndsditch, he had received the added appellation of Jerry."

Commentary:

Jerry, messenger and part-time medical supplier (read "grave-robber") is seated next to his son, young Jerry, the relationship made immediately manifest be similarities in the clothing, posture, and physiognomy. Jerry is every inch the eighteenth-century "bully boy" straight out of such Hogarth compositions as Chairing of the Candidate, complete with rough-hewn cane suitable for street fighting. Waiting to be called to deliver a letter for one of the bank's employees, the pair are leaning against the wall outside Tellson's. Jerry is of a much burlier, robust, and physically intimidating species of private messenger (the Victorian penny-post being many years in the offing as A Tale of Two Cities opens during the Seven Years War) than the gentle Trotty Veck, the humble ticket-porter of The Chimes (1844)."

"The Lion and the Jackal"

Book II Chapter 5

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

"The lion then composed himself on his back on a sofa on one side of the drinking-table, while the jackal sat at his own paper-bestrewn table proper, on the other side of it, with the bottles and glasses ready to his hand. Both resported to the drinking-table without stint, but each in a different way; the lion for the most part reclining with his hands in his waistband, looking at the fire, or occassionally flirting with some lighter document; the jackal, with knitted brows and intent face, so deep in his task, that his eyes did not even follow the hand he stretched out for his glass — which often groped about, for a minute or more, before it found the glass for his lips. Two or three times the matter in hand became so knotty, that the jackal found it imperative on him to get up, and steep his towels anew. From these pilgrimages to the jug and basin, he returned with such eccentricities of damp headgear as no words can describe; which were made the more ludicrous by his anxious gravity.

At length the jackal had got together a compact repast for the lion, and proceeded to offer it to him. The lion took it with care and caution, made his selections from it, and his remarks upon it, and the jackal assisted both. When the repast was fully discussed, the lion put his hands in his waistband again, and lay down to meditate. The jackal then invigorated himself with a bumper for his throttle, and a fresh application to his head, and applied himself to the collection of a second meal; this was administered to the lion in the same manner, and was not disposed of until the clocks struck three in the morning."

Commentary:

The "repast" that the Jackal thus prepares for the barrister is the case as he will argue it in court, the Lion taking full advantage of Carton's alcoholism to exploit his legal talents. A scene very similar to Barnard's occurred in McLenan's sequence for the Harper's Weekly serialisation; indeed, Mclenan's scene is also entitled "The Lion and the Jackal". Phiz, Barnard's friend and confidant, in the original monthly parts shows the public faces of the Lion and his Jackal in formal legal attire after Darnay's Old Bailey trial in the steel engraving "Congratulations", one of a pair of illustrations for the July, 1859, number.

"And smoothing her rich hair"

Book II Chapter 6

Fred Barnard

The Household Edition 1870s

Text Illustrated:

"Here they are!" said Miss Pross, rising to break up the conference; "and now we shall have hundreds of people pretty soon!"

It was such a curious corner in its acoustical properties, such a peculiar Ear of a place, that as Mr. Lorry stood at the open window, looking for the father and daughter whose steps he heard, he fancied they would never approach. Not only would the echoes die away, as though the steps had gone; but, echoes of other steps that never came would be heard in their stead, and would die away for good when they seemed close at hand. However, father and daughter did at last appear, and Miss Pross was ready at the street door to receive them.

Miss Pross was a pleasant sight, albeit wild, and red, and grim, taking off her darling's bonnet when she came up-stairs, and touching it up with the ends of her handkerchief, and blowing the dust off it, and folding her mantle ready for laying by, and smoothing her rich hair with as much pride as she could possibly have taken in her own hair if she had been the vainest and handsomest of women. Her darling was a pleasant sight too, embracing her and thanking her, and protesting against her taking so much trouble for her—which last she only dared to do playfully, or Miss Pross, sorely hurt, would have retired to her own chamber and cried. The Doctor was a pleasant sight too, looking on at them, and telling Miss Pross how she spoilt Lucie, in accents and with eyes that had as much spoiling in them as Miss Pross had, and would have had more if it were possible. Mr. Lorry was a pleasant sight too, beaming at all this in his little wig, and thanking his bachelor stars for having lighted him in his declining years to a Home. But, no Hundreds of people came to see the sights, and Mr. Lorry looked in vain for the fulfilment of Miss Pross's prediction."

Commentary:

Dickens describes the relationship between the beautiful Lucie Manette and her older friend — almost a surrogate mother — Miss Pross, who dotes upon the teenager, calling her "Ladybird" and generally doting upon her as if Lucie were her daughter in A Tale of Two Cities, Book the Second, "The Golden Thread," ch. 6, "Hundreds of People." Taking into account the lengthy title of the illustration, "And smoothing her rich hair with as much pride as she could possibly have taken in her own hair if she had been the vainest and handsomest of women" the reader would likely make the connection between this eighth woodcut and the following passage that begins on the facing page:

"Miss Pross was a pleasant sight, albeit wild, and red, and grim, taking off her darling's bonnet when she came up-stairs, and touching it up with the ends of her handkerchief, and blowing the dust off it, and folding her mantle ready for laying by, and smoothing her rich hair with as much pride as she could possibly have taken in her own hair if she had been the vainest and handsomest of women."

The relationship is not nearly so closely described in Phiz's original narrative-pictorial sequence for the novel, the relevant illustration being "Hundreds of People" (Dec., 1859), the frontispiece that shows Lucie with her father, Lorry, Carton, and Darnay, but significantly not Miss Pross, whom Phiz depicts clearly only in "The Double Recognition" (the other December, 1859, illustration).

John McLenan, the American illustrator for the Harper's serialization of the novel, appears not to have been much interested in Miss Pross, showing her in "Miss Pross and Mr. Lorry", June 25, 1859, and in the November 26, 1859 weekly installment. Certainly Barnard's old maid is a far more formidable figure than those of Phiz and McLenan.

Jerry Cruncher and Wife

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Book II Chapter 1

Diamond Edition of Dickens's Works 1867

Text Illustrated:

"What!" said Mr. Cruncher, looking out of bed for a boot. "You're at it agin, are you?"

After hailing the morn with this second salutation, he threw a boot at the woman as a third. It was a very muddy boot, and may introduce the odd circumstance connected with Mr. Cruncher's domestic economy, that, whereas he often came home after banking hours with clean boots, he often got up next morning to find the same boots covered with clay.

"What," said Mr. Cruncher, varying his apostrophe after missing his mark—"what are you up to, Aggerawayter?"

"I was only saying my prayers."

"Saying your prayers! You're a nice woman! What do you mean by flopping yourself down and praying agin me?"

"I was not praying against you; I was praying for you."

"You weren't. And if you were, I won't be took the liberty with. Here! your mother's a nice woman, young Jerry, going a praying agin your father's prosperity. You've got a dutiful mother, you have, my son. You've got a religious mother, you have, my boy: going and flopping herself down, and praying that the bread-and-butter may be snatched out of the mouth of her only child."

Master Cruncher (who was in his shirt) took this very ill, and, turning to his mother, strongly deprecated any praying away of his personal board.

"And what do you suppose, you conceited female," said Mr. Cruncher, with unconscious inconsistency, "that the worth of your prayers may be? Name the price that you put your prayers at!"

"They only come from the heart, Jerry. They are worth no more than that."

"Worth no more than that," repeated Mr. Cruncher. "They ain't worth much, then. Whether or no, I won't be prayed agin, I tell you. I can't afford it. I'm not a going to be made unlucky by your sneaking. If you must go flopping yourself down, flop in favour of your husband and child, and not in opposition to 'em. If I had had any but a unnat'ral wife, and this poor boy had had any but a unnat'ral mother, I might have made some money last week instead of being counter-prayed and countermined and religiously circumwented into the worst of luck. B-u-u-ust me!" said Mr. Cruncher, who all this time had been putting on his clothes, "if I ain't, what with piety and one blowed thing and another, been choused this last week into as bad luck as ever a poor devil of a honest tradesman met with! Young Jerry, dress yourself, my boy, and while I clean my boots keep a eye upon your mother now and then, and if you see any signs of more flopping, give me a call. For, I tell you," here he addressed his wife once more, "I won't be gone agin, in this manner. I am as rickety as a hackney-coach, I'm as sleepy as laudanum, my lines is strained to that degree that I shouldn't know, if it wasn't for the pain in 'em, which was me and which somebody else, yet I'm none the better for it in pocket; and it's my suspicion that you've been at it from morning to night to prevent me from being the better for it in pocket, and I won't put up with it, Aggerawayter, and what do you say now!"

Commentary: