The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities

>

Book II, Chp. 7-13

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Now let’s turn to the last three chapters of this week’s reading plan: In Chapter 11, we see “A Companion Picture”. Carton is again hard at work, and at drink, for Stryver, when the latter by and by informs him about his intentions of offering marriage to Lucie Manette. Still more big-headed than he used to be, the lawyer expatiates on Carton’s lack of refinement and sensitiveness and advises him to find himself a possible bride, too, preferably in the landlady way, i.e. with a view to being looked after. Now, to make an aside, this reminded me of a peculiar German expression, namely of the word “Bratkartoffelverhältnis”, which is literally “a fried potato relationship”. It means a loose affair in which the man also tries to enjoy commodities like warm meals and other services. I wonder if the English language has a word for it or if this is a typically German thing.

Again, to come back to the chapter, I quite admired Carton’s repartee with Stryver, and I was surprised at the cold-bloodedness with which he greeted the news of his big-headed friend. Maybe he could muster up so much cold-bloodedness because something tells him that Lucie would not be likely to marry Stryver.

On his way to the Manettes – we are now in the next chapter –, Stryver gets the idea to drop by at Tellson’s Bank and to tell Mr. Lorry about his plans, which he accordingly does in a very self-complacent and all-hat-no-cattle way: “’I am going to make an offer of myself in marriage to your agreeable little friend, Miss Manette, Mr. Lorry.’” Now that’s really, really a “Fellow of Delicacy”! To his surprise, Mr. Lorry is not very much convinced that his suit will be a successful one, and he is clever enough to have Mr. Lorry see how the land is lying. When that very evening Mr. Lorry comes to Stryver’s place in order to inform him that there is little or no hope for Stryver to obtain Lucie’s hand, the lawyer has already decided on a course of action – namely on that of the fox who wasn’t able to reach the grapes he had actually wanted. He now pretends to have almost forgotten of the whole thing and to be actually glad for himself, but still a little bit sad for the young girl, whose fastidiousness was too much in her way.

Chapter 13 deals with “The Fellow of No Delicacy”, Mr. Carton, and it is set a few weeks after the events described before. Now Mr. Carton pays a visit to Miss Lucie, in which he pours out his heart to her, basically telling her that he knows that his life is without aim and purpose and value but that if it were not so, he would find it in his heart to strife for her love. But since it is not so … well. What might have made Sydney do such a thing? He must be very much in despair indeed, as the following words show:

”’I am like one who died young. All my life might have been!’”

As I said, I find that a very modern attitude, and this might be discussed in this week’s thread. But, of course, everybody is welcome to write what they liked or disliked or wondered about most.

Again, to come back to the chapter, I quite admired Carton’s repartee with Stryver, and I was surprised at the cold-bloodedness with which he greeted the news of his big-headed friend. Maybe he could muster up so much cold-bloodedness because something tells him that Lucie would not be likely to marry Stryver.

On his way to the Manettes – we are now in the next chapter –, Stryver gets the idea to drop by at Tellson’s Bank and to tell Mr. Lorry about his plans, which he accordingly does in a very self-complacent and all-hat-no-cattle way: “’I am going to make an offer of myself in marriage to your agreeable little friend, Miss Manette, Mr. Lorry.’” Now that’s really, really a “Fellow of Delicacy”! To his surprise, Mr. Lorry is not very much convinced that his suit will be a successful one, and he is clever enough to have Mr. Lorry see how the land is lying. When that very evening Mr. Lorry comes to Stryver’s place in order to inform him that there is little or no hope for Stryver to obtain Lucie’s hand, the lawyer has already decided on a course of action – namely on that of the fox who wasn’t able to reach the grapes he had actually wanted. He now pretends to have almost forgotten of the whole thing and to be actually glad for himself, but still a little bit sad for the young girl, whose fastidiousness was too much in her way.

Chapter 13 deals with “The Fellow of No Delicacy”, Mr. Carton, and it is set a few weeks after the events described before. Now Mr. Carton pays a visit to Miss Lucie, in which he pours out his heart to her, basically telling her that he knows that his life is without aim and purpose and value but that if it were not so, he would find it in his heart to strife for her love. But since it is not so … well. What might have made Sydney do such a thing? He must be very much in despair indeed, as the following words show:

”’I am like one who died young. All my life might have been!’”

As I said, I find that a very modern attitude, and this might be discussed in this week’s thread. But, of course, everybody is welcome to write what they liked or disliked or wondered about most.

Tristram wrote: "Hello Curiosities,

Tristram wrote: "Hello Curiosities,At the beginning of this week’s read, the narrator takes us back to France, where we will stay for about three chapters before going back to London. After all, it is a tale of t..."

I have always found these chapters very confusing: first because there is a Monseigneur, who it turns out is not our focus character but rather Monsieur the Marquis is--but then Monsieur the Marquis becomes Monseigneur--so that's both of them? Which one were we talking about in the city? And then there's all the bit about stone faces and which stone faces are really stone faces (the gargoyles outside the chateau) and which are not (the dead man on the pillow), and I still can't tell you without looking back again who or what the Gorgon is. It took me a great deal of time to sort all this out when I first read it, and I still go through a bit of a headspin trying to keep the people straight--including all the town and country people.

One thing I am still not sure of: Darnay went off to bed, presumably in the chateau, after he was dismissed by his uncle. So presumably he's also still around when his uncle turns up dead? He knows his uncle is dead?

Anyway: all still very good stuff. I guess the Marquis is kind of cartoonishly evil but I admire how quickly he is dispatched so we can get onto more complicated villainy, and in the meantime his presence (along with Dr. Manette's) does give us a sense of why France needs to change.

Tristram wrote: "Another strange thing is that this very night, Lucie has the impression that her father has reverted to his shoemaker’s bench again. Have you any theory as to why?"

Tristram wrote: "Another strange thing is that this very night, Lucie has the impression that her father has reverted to his shoemaker’s bench again. Have you any theory as to why?"I'm still stuck on why he continues to keep the shoemaker's bench around at all, but I like it. It's this quiet lurking reminder in the middle of their idyllic cottage that they haven't left the past as far behind as they might think they have.

but, strangely, the doctor waives all further words aside and says that there might be a time when they should revert to this subject.

Okay, not just *any* time: he says in the event that you're about to marry my daughter, tell me your family name on the morning of your wedding. Isn't that maybe a little too late?

This reminds me of Frankenstein, in which Victor tells Elizabeth he will explain all the crazy weird things *including deaths* that are happening all around them, tell her absolutely everything--as soon as they are married. Which works out every bit as badly as it sound like it will.

Unless Dr. Manette wants it to be too late when he finds out?

Tristram wrote: "this reminded me of a peculiar German expression, namely of the word “Bratkartoffelverhältnis”, which is literally “a fried potato relationship”. It means a loose affair in which the man also tries to enjoy commodities like warm meals and other services. I wonder if the English language has a word for it or if this is a typically German thing."

Tristram wrote: "this reminded me of a peculiar German expression, namely of the word “Bratkartoffelverhältnis”, which is literally “a fried potato relationship”. It means a loose affair in which the man also tries to enjoy commodities like warm meals and other services. I wonder if the English language has a word for it or if this is a typically German thing."As far as I know all we have is "friends with benefits," and the benefits are not fried potatoes.

In chapter 8, what is difference between Monseigneur and Monsieur?

In chapter 8, what is difference between Monseigneur and Monsieur?I noted that the monsieur (running his eyes over crowd) said " as if they had been mere rats coming out their holes." Sounds like the Marquis would say that. But I am not sure.

I'd forgotten all about the Marquis until his carriage started careening around bends, and then the coming scene came crashing back into my mind. The Marquis is worse than Skimpole.

I'd forgotten all about the Marquis until his carriage started careening around bends, and then the coming scene came crashing back into my mind. The Marquis is worse than Skimpole. Like Julie, I wondered where Darnay was and how he escaped his uncle's fate, but this particular attack seems to have been targeted.

When Darnay was meeting with the good doctor, was anyone else reminded of Prince and Caddy in Bleak House, with their assurances that their union would in no way take Prince away from Mr. Turveydrop? What is is with Dickens and these needy parents? I guess it was something with which he had personal experience.

I'm warming up to the story as it goes along. I do miss the humor and quirky characters. In fact, it's good that this novel has a smaller cast. Without the physical and verbal tics, it's harder to keep these characters straight - or would be if there were more of them. The interaction between Mr. Lorry and Stryver was mildly amusing, and didn't come a moment too soon!

Julie, I acknowledge the differences you pointed out between Lucie and "the other Marys". :-) Her attempts at convincing Carton that he could still turn his life around were admirable (and not overly soppy). I'll try to be open-minded and see how she continues to compare as the novel goes on.

Peter, I listened to this installment (rather than reading it), so might have missed some details. Did we have any mirrors? I think there may have been some mention of them when the Marquis was in his rooms, visiting with Darnay but, if so, they didn't register in that moment.

A "fried potato relationship" in its literal sense sounds like heaven. I love fried potatoes (with a little garlic). My favorite story of German culture that my kids had when they lived there was that the Kartoffelmann regularly came through their neighborhood selling potatoes, the way we have ice cream trucks coming around in the summertime. Not prepared (although that would have been even better!), just a cart of raw potatoes. But I digress....

Who said there was no humor in A Tale of Two Cities? Dickens without humor or satire (which I usually regard as humor) is not Dickens; he always points a finger at the vain, the proud, the obscene. Chapter 7 is just lovely. I laughed though all of it when Monseigneur keeps so many waiting until he can "take his chocolate" and has to have three strong men besides the cook create it for him. All of his "attendants" are so perfect, as is the great man as he carefully, slowly walks among the lowly petitioners. Not only does he walk among them, he turns around and walks back - just like the participants in the Miss America contest. Keep reading. After Monseigneur "eased" the four men of their burden of chocolate, he caused the doors of the "Holiest of Holiests" to be "thrown open" and he issued forth. I almost felt that I was reading the Bible.

Who said there was no humor in A Tale of Two Cities? Dickens without humor or satire (which I usually regard as humor) is not Dickens; he always points a finger at the vain, the proud, the obscene. Chapter 7 is just lovely. I laughed though all of it when Monseigneur keeps so many waiting until he can "take his chocolate" and has to have three strong men besides the cook create it for him. All of his "attendants" are so perfect, as is the great man as he carefully, slowly walks among the lowly petitioners. Not only does he walk among them, he turns around and walks back - just like the participants in the Miss America contest. Keep reading. After Monseigneur "eased" the four men of their burden of chocolate, he caused the doors of the "Holiest of Holiests" to be "thrown open" and he issued forth. I almost felt that I was reading the Bible. The Marquis has a nasty little speech after his reckless carriage driver has killed a child, "It is extraordinary to me that you people cannot take care of yourselves and your children." This is cruel but humorous. (Always putting the blame on others.) Of course, the later part is not so humorous for him.

peace, janz

Mary Lou wrote: "I'd forgotten all about the Marquis until his carriage started careening around bends, and then the coming scene came crashing back into my mind. The Marquis is worse than Skimpole.

Like Julie, I..."

Hi Mary Lou

You asked about mirrors so let me see … as for the physical presence of mirrors no, but looking a bit further …

Charles Darnay meets his uncle in an opulent chateau. They are obviously estranged from one another and the Marquis is a very unpleasant man. On two occasions in chapter the Marquis comments that he has learned that Charles in England has met “a compatriot who has found Refuge there? A Doctor.” (A bad pun coming) Dickens often repeats words or phrases for emphasis. If we reflect on this stylistic feature why would the Marquis make such a comment? The comment seems out of joint in their conversation.

This same evening the Marquis is killed. We read that “the Gorgon had surveyed the building again in the night, and had added the one stone face wanting; the stone face for which it had waited through about two hundred years.” Here is a reference to faces. The face of the Marquis is compared to the faces carved into the stone of the chateau. Dickens titled the chapter “The Gorgon’s head.” The faces of stone one the walls of the chateau and the dead face of the Marquis are thus compared, they look alike in death. So, no mirrors, but a clear comparison of faces. And, of course, Charles Darnay meets his uncle again in this chateau face-to-face.

Like Julie, I..."

Hi Mary Lou

You asked about mirrors so let me see … as for the physical presence of mirrors no, but looking a bit further …

Charles Darnay meets his uncle in an opulent chateau. They are obviously estranged from one another and the Marquis is a very unpleasant man. On two occasions in chapter the Marquis comments that he has learned that Charles in England has met “a compatriot who has found Refuge there? A Doctor.” (A bad pun coming) Dickens often repeats words or phrases for emphasis. If we reflect on this stylistic feature why would the Marquis make such a comment? The comment seems out of joint in their conversation.

This same evening the Marquis is killed. We read that “the Gorgon had surveyed the building again in the night, and had added the one stone face wanting; the stone face for which it had waited through about two hundred years.” Here is a reference to faces. The face of the Marquis is compared to the faces carved into the stone of the chateau. Dickens titled the chapter “The Gorgon’s head.” The faces of stone one the walls of the chateau and the dead face of the Marquis are thus compared, they look alike in death. So, no mirrors, but a clear comparison of faces. And, of course, Charles Darnay meets his uncle again in this chateau face-to-face.

Peacejanz wrote: "Who said there was no humor in A Tale of Two Cities? Dickens without humor or satire (which I usually regard as humor) is not Dickens; he always points a finger at the vain, the proud, the obscene...."

Hi Peacejanz

I agree with you. While there is very little light gentle humour, harmless quirky characters, slapstick comedy or situational Seinfeld type comedy there is a very bitter angry vein of events that, turned on their heads, can be seen as humourous. Jerry’s wife’s flopping is rather disturbing, in context with a child in the room worrisome, and Jerry’s response insensitive but one could see the episode as funny. The chocolate feeding scene is equally shocking, but if seen onstage could be very funny given the circumstances.

What makes a person laugh is a very subjective. I could not laugh at either the chocolate scene or the flopping scene within the context of the text but could see both a being humourous when done on Saturday Night Live in a different context.

Hi Peacejanz

I agree with you. While there is very little light gentle humour, harmless quirky characters, slapstick comedy or situational Seinfeld type comedy there is a very bitter angry vein of events that, turned on their heads, can be seen as humourous. Jerry’s wife’s flopping is rather disturbing, in context with a child in the room worrisome, and Jerry’s response insensitive but one could see the episode as funny. The chocolate feeding scene is equally shocking, but if seen onstage could be very funny given the circumstances.

What makes a person laugh is a very subjective. I could not laugh at either the chocolate scene or the flopping scene within the context of the text but could see both a being humourous when done on Saturday Night Live in a different context.

Tristram wrote: "Now, to make an aside, this reminded me of a peculiar German expression, namely of the word “Bratkartoffelverhältnis”, which is literally “a fried potato relationship”. It means a loose affair in which the man also tries to enjoy commodities like warm meals and other services. I wonder if the English language has a word for it or if this is a typically German thing...."

“Bratkartoffelverhältnis”? Is there an English word for it? If there is I hope I never discover it. It is a word only a German would know. I did look it up though, here it is:

"Bratkartoffelverhältnis literally translated means, “fried potato relationship” or one could say an “on-off relationship,” which does not have to be short-lived, just a casual arrangement of mutual convenience. The idiom, “Er hat ein Bratkartoffelverhätnis mit ihr.” translates into “he only see her because she provides water and food for him.” Even stranger, “Er sucht ein Bratkartoffelverhältnis.” which means, “he’s looking for a meal ticket.”

This colloquial expression, for a casual affair, is probably due to the impact WWI had on a man’s basic necessities. Having a woman who provided such things as a warm meal and shelter were more important than purposeful relationships. After the Second World War it was a popular term to describe the casual love relationship between returning veterans and widows, who were living in common-law relationships, to avoid losing the widows’ pensions.

Today, in Germany, it is used casually when referring to relationships that are sporadic or not very serious love affairs; sometimes also used as a metaphor for occasional friendly cooperation in other areas of life. This form of co-existence was considered a breach of good manners until the mid 1970’s. Extending a rental contract to an unmarried couple was seen as facilitating pandering, which was illegal, making the agreement invalid. Until 1969 it was a criminal risk for landlords to enter into these contracts. The protests of 1968 consisted of a worldwide series of protests, largely participated in by an anti-establishment culture. With the change in sexual tolerance since then, non-marital partnerships have been increasingly tolerated in Germany.

Some may ask, “what version of “Bratkartoffelverhältnis” did you mean?” Often it can be a little intimate and friendly relationship, and sometimes it can just be intimate while others say it can be just friendly.

Bratkartofflen are one of the most common side dishes in Germany. Simple, like many of the time-honored dishes in any traditional cuisine, but just perfect. Bratkartoffeln are raw or cooked potatoes fried with bacon and onion, often seasoned with salt and pepper. Bratkartoffeln are served as a side dish with many types of entrees and also make a good breakfast dish when served with “Rühreier” (scrambled eggs). It will take 20 – 30 minutes to cook them to a crispy golden brown, but the wait is worth it. One could call them “German soul food.”

As far as I know we have nothing like it. Thankfully.

“Bratkartoffelverhältnis”? Is there an English word for it? If there is I hope I never discover it. It is a word only a German would know. I did look it up though, here it is:

"Bratkartoffelverhältnis literally translated means, “fried potato relationship” or one could say an “on-off relationship,” which does not have to be short-lived, just a casual arrangement of mutual convenience. The idiom, “Er hat ein Bratkartoffelverhätnis mit ihr.” translates into “he only see her because she provides water and food for him.” Even stranger, “Er sucht ein Bratkartoffelverhältnis.” which means, “he’s looking for a meal ticket.”

This colloquial expression, for a casual affair, is probably due to the impact WWI had on a man’s basic necessities. Having a woman who provided such things as a warm meal and shelter were more important than purposeful relationships. After the Second World War it was a popular term to describe the casual love relationship between returning veterans and widows, who were living in common-law relationships, to avoid losing the widows’ pensions.

Today, in Germany, it is used casually when referring to relationships that are sporadic or not very serious love affairs; sometimes also used as a metaphor for occasional friendly cooperation in other areas of life. This form of co-existence was considered a breach of good manners until the mid 1970’s. Extending a rental contract to an unmarried couple was seen as facilitating pandering, which was illegal, making the agreement invalid. Until 1969 it was a criminal risk for landlords to enter into these contracts. The protests of 1968 consisted of a worldwide series of protests, largely participated in by an anti-establishment culture. With the change in sexual tolerance since then, non-marital partnerships have been increasingly tolerated in Germany.

Some may ask, “what version of “Bratkartoffelverhältnis” did you mean?” Often it can be a little intimate and friendly relationship, and sometimes it can just be intimate while others say it can be just friendly.

Bratkartofflen are one of the most common side dishes in Germany. Simple, like many of the time-honored dishes in any traditional cuisine, but just perfect. Bratkartoffeln are raw or cooked potatoes fried with bacon and onion, often seasoned with salt and pepper. Bratkartoffeln are served as a side dish with many types of entrees and also make a good breakfast dish when served with “Rühreier” (scrambled eggs). It will take 20 – 30 minutes to cook them to a crispy golden brown, but the wait is worth it. One could call them “German soul food.”

As far as I know we have nothing like it. Thankfully.

Julie wrote: "I have always found these chapters very confusing: first because there is a Monseigneur, who it turns out is not our focus character but rather Monsieur the Marquis is--but then Monsieur the Marquis becomes Monseigneur--so that's both of them? Which one were we talking about in the city?.."

I looked it up. It hasn't helped me at all, but here it is:

"Monseigneur is an honorific in the French language. It has occasional English use as well, as it may be a title before the name of a French prelate, a member of a royal family or other dignitary.

Monsignor is both a title and an honorific in the Roman Catholic Church. In francophone countries, it is rendered Monseigneur, and this spelling is also commonly encountered in Canadian English practice. Nowadays, the title is used for bishops. In France the use monsignori are not called monseigneur but the more common monsieur l'abbé, as are priests. The plural form is Messeigneurs."

And now on to Marquis:

"A marquess; French: marquis; Spanish: marqués is a nobleman of hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The term is also used to translate equivalent Asian styles, as in imperial China and Japan.

In Great Britain and Ireland, the correct spelling of the aristocratic title of this rank is marquess (although for aristocratic titles on the European mainland, the French spelling of marquis is often used in English). In Great Britain and Ireland, the title ranks below a duke and above an earl. A woman with the rank of a marquess, or the wife of a marquess, is called a marchioness in Great Britain and Ireland or a marquise elsewhere in Europe. The dignity, rank or position of the title is referred to as a marquisate or marquessate.

The theoretical distinction between a marquess and other titles has, since the Middle Ages, faded into obscurity. In times past, the distinction between a count and a marquess was that the land of a marquess, called a march, was on the border of the country, while a count's land, called a county, often was not. As a result of this, a marquess was trusted to defend and fortify against potentially hostile neighbours and was thus more important and ranked higher than a count. The title is ranked below that of a duke, which was often restricted to the royal family and those that were held in high enough esteem to be granted such a title.

In the German lands, a Margrave was a ruler of an immediate Imperial territory (examples include the Margrave of Brandenburg, the Margrave of Baden and the Margrave of Bayreuth), not simply a nobleman like a marquess or marquis in Western and Southern Europe. German rulers did not confer the title of marquis; holders of marquisates in Central Europe were largely associated with the Italian and Spanish crowns."

I looked it up. It hasn't helped me at all, but here it is:

"Monseigneur is an honorific in the French language. It has occasional English use as well, as it may be a title before the name of a French prelate, a member of a royal family or other dignitary.

Monsignor is both a title and an honorific in the Roman Catholic Church. In francophone countries, it is rendered Monseigneur, and this spelling is also commonly encountered in Canadian English practice. Nowadays, the title is used for bishops. In France the use monsignori are not called monseigneur but the more common monsieur l'abbé, as are priests. The plural form is Messeigneurs."

And now on to Marquis:

"A marquess; French: marquis; Spanish: marqués is a nobleman of hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The term is also used to translate equivalent Asian styles, as in imperial China and Japan.

In Great Britain and Ireland, the correct spelling of the aristocratic title of this rank is marquess (although for aristocratic titles on the European mainland, the French spelling of marquis is often used in English). In Great Britain and Ireland, the title ranks below a duke and above an earl. A woman with the rank of a marquess, or the wife of a marquess, is called a marchioness in Great Britain and Ireland or a marquise elsewhere in Europe. The dignity, rank or position of the title is referred to as a marquisate or marquessate.

The theoretical distinction between a marquess and other titles has, since the Middle Ages, faded into obscurity. In times past, the distinction between a count and a marquess was that the land of a marquess, called a march, was on the border of the country, while a count's land, called a county, often was not. As a result of this, a marquess was trusted to defend and fortify against potentially hostile neighbours and was thus more important and ranked higher than a count. The title is ranked below that of a duke, which was often restricted to the royal family and those that were held in high enough esteem to be granted such a title.

In the German lands, a Margrave was a ruler of an immediate Imperial territory (examples include the Margrave of Brandenburg, the Margrave of Baden and the Margrave of Bayreuth), not simply a nobleman like a marquess or marquis in Western and Southern Europe. German rulers did not confer the title of marquis; holders of marquisates in Central Europe were largely associated with the Italian and Spanish crowns."

Kim's research makes brakartoffelverhältnus sound so reasonable and practical, while Tristram's definition sounds so seedy.

Kim's research makes brakartoffelverhältnus sound so reasonable and practical, while Tristram's definition sounds so seedy.

Mary Lou wrote: "I'd forgotten all about the Marquis until his carriage started careening around bends, and then the coming scene came crashing back into my mind. The Marquis is worse than Skimpole."

Mary Lou wrote: "I'd forgotten all about the Marquis until his carriage started careening around bends, and then the coming scene came crashing back into my mind. The Marquis is worse than Skimpole."Whoa! Fighting words! :)

Julie, I acknowledge the differences you pointed out between Lucie and "the other Marys". :-) Her attempts at convincing Carton that he could still turn his life around were admirable (and not overly soppy). I'll try to be open-minded and see how she continues to compare as the novel goes on.

I will try as well. The reason I list the first book of Tale of Two Cities as my favorite Dickens is that I vaguely remember feeling it went downhill after Book 1, largely for Lucie-related reasons. But I haven't read it for a long time, and I have a lot more Dickens under my belt since then, so we'll see. I'm still thoroughly enjoying it.

Tristram wrote: "Hello Curiosities,

At the beginning of this week’s read, the narrator takes us back to France, where we will stay for about three chapters before going back to London. After all, it is a tale of t..."

Tristram

There is much happening in these chapters. Where to start? I’m glad you pointed out the fountains and how they seem to be the central meeting place of a town, village or community. In an upcoming chapter I will be making more references to fountains. For now, let's just look at how they function in the chapter and realize that fountains and water may well form an ongoing and increasingly important role in the novel.

I too found it curious that Charles’s uncle seemed to know some of his nephew’s backstory, even though the two have not met in some time and apparently not been in written contact either. Now, why is it that the uncle knows about Doctor Manette? What concerns would the uncle have concerning who will have a claim to his title/power when he passes?

We know that Charles Darnay has been spied upon both in England and France. Who would have initiated such suspicions on Charles? Who would benefit, or at least be comforted, knowing that Charles would be put to death if convicted? Could it be the uncle has attempted to put Charles to death?

I see the shoemaker’s bench as a comfort zone for the Doctor. When agitated, worried, or in need of comfort many people revert back to some item, object, picture, or mémento that offers comfort and security.

I see the repetitive name of Jacques as a method to foil the enemies of the poor. If caught, tortured or threatened each Jacques could never give the real name of any other member of their group. If one is Jacques, all are Jacques.

At the beginning of this week’s read, the narrator takes us back to France, where we will stay for about three chapters before going back to London. After all, it is a tale of t..."

Tristram

There is much happening in these chapters. Where to start? I’m glad you pointed out the fountains and how they seem to be the central meeting place of a town, village or community. In an upcoming chapter I will be making more references to fountains. For now, let's just look at how they function in the chapter and realize that fountains and water may well form an ongoing and increasingly important role in the novel.

I too found it curious that Charles’s uncle seemed to know some of his nephew’s backstory, even though the two have not met in some time and apparently not been in written contact either. Now, why is it that the uncle knows about Doctor Manette? What concerns would the uncle have concerning who will have a claim to his title/power when he passes?

We know that Charles Darnay has been spied upon both in England and France. Who would have initiated such suspicions on Charles? Who would benefit, or at least be comforted, knowing that Charles would be put to death if convicted? Could it be the uncle has attempted to put Charles to death?

I see the shoemaker’s bench as a comfort zone for the Doctor. When agitated, worried, or in need of comfort many people revert back to some item, object, picture, or mémento that offers comfort and security.

I see the repetitive name of Jacques as a method to foil the enemies of the poor. If caught, tortured or threatened each Jacques could never give the real name of any other member of their group. If one is Jacques, all are Jacques.

A fried potato relationship. Well, that’s a new one on me. Tristram, how do you remember how to spell all these convoluted words? In English, I think the word gigolo may come close, but a gigolo also suggests someone who seeks comfort and companionship with more than one woman at a time.

re Bratkartoffelverhältnis

Mary Lou, I meant the word to take on a seedy connotation because as far as I know most people here use it in connection with a sexual relationship, which is entered into for the sake of convenience and without any romanticism involved. As I am a very romantic person, I never had a Bratkartoffelverhältnis, although I'd normally go out of my way for a dish of Bratkartoffeln, especially if they are served with Bratwürstchen (fried sausages) or Rollmops, which is a rolled fillet of raw marinated herring - very, very tasty!!! - and a big mug of beer.

Anyway, Bratkartoffeln and Spiegelei (fried egg) was the dish we always prepared at about three in the morning when, as young blades, we came home from a pub crawl in our uni days. It's a typical German thing to end a pub crawl at home like that so you won't have too much of a hangover in the morning.

Mary Lou, I meant the word to take on a seedy connotation because as far as I know most people here use it in connection with a sexual relationship, which is entered into for the sake of convenience and without any romanticism involved. As I am a very romantic person, I never had a Bratkartoffelverhältnis, although I'd normally go out of my way for a dish of Bratkartoffeln, especially if they are served with Bratwürstchen (fried sausages) or Rollmops, which is a rolled fillet of raw marinated herring - very, very tasty!!! - and a big mug of beer.

Anyway, Bratkartoffeln and Spiegelei (fried egg) was the dish we always prepared at about three in the morning when, as young blades, we came home from a pub crawl in our uni days. It's a typical German thing to end a pub crawl at home like that so you won't have too much of a hangover in the morning.

Peter wrote: "In an upcoming chapter I will be making more references to fountains. For now, let's just look at how they function in the chapter and realize that fountains and water may well form an ongoing and increasingly important role in the novel."

I regard the fountain as a subtle reference to the beginning of something, the spring, the source, and in this context it will be the spring and source of violence and bloodshed. So, it's no wonder that the first fountain is the place where the corpse of the little child run over by the vile nobleman - who is indeed the caricature of a villain, as Mary Lou points it out, but who also reminded me of Mr Chester - is laid.

I see the shoemaker’s bench as a comfort zone for the Doctor. When agitated, worried, or in need of comfort many people revert back to some item, object, picture, or mémento that offers comfort and security.

There are doubtless psychological reasons for Dr Manette's keeping that modest workbench, as a keepsake from times he may not want to remember but still cannot forget. After all, the bench and the work done at it were a vent of escape in their own modest way. On another level, a symbolical one, the bench may be a way to foreshadow that the doctor's days of trial and tribulation may not be over yet.

Could it be the uncle has attempted to put Charles to death?

I don't know about that, but we can be pretty sure that the uncle wanted to get a lettre de cachet against his own nephew in order to get him out of the way. I also have strong suspicions that either Charles's uncle or his late father had a hand in the doctor's term of prison: Why else should the doctor have that strange feeling when he sometimes looks at Charles's face? Is there a family resemblence reminding Manette of some of his former enemies? I don't think it will be too wise to tell Manette Darnay's real name.

I regard the fountain as a subtle reference to the beginning of something, the spring, the source, and in this context it will be the spring and source of violence and bloodshed. So, it's no wonder that the first fountain is the place where the corpse of the little child run over by the vile nobleman - who is indeed the caricature of a villain, as Mary Lou points it out, but who also reminded me of Mr Chester - is laid.

I see the shoemaker’s bench as a comfort zone for the Doctor. When agitated, worried, or in need of comfort many people revert back to some item, object, picture, or mémento that offers comfort and security.

There are doubtless psychological reasons for Dr Manette's keeping that modest workbench, as a keepsake from times he may not want to remember but still cannot forget. After all, the bench and the work done at it were a vent of escape in their own modest way. On another level, a symbolical one, the bench may be a way to foreshadow that the doctor's days of trial and tribulation may not be over yet.

Could it be the uncle has attempted to put Charles to death?

I don't know about that, but we can be pretty sure that the uncle wanted to get a lettre de cachet against his own nephew in order to get him out of the way. I also have strong suspicions that either Charles's uncle or his late father had a hand in the doctor's term of prison: Why else should the doctor have that strange feeling when he sometimes looks at Charles's face? Is there a family resemblence reminding Manette of some of his former enemies? I don't think it will be too wise to tell Manette Darnay's real name.

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "In an upcoming chapter I will be making more references to fountains. For now, let's just look at how they function in the chapter and realize that fountains and water may well form a..."

Yes. The doctor looking at Darnay’s face and then having such a response suggests some form of connection, ressemblance, or association. Whatever the answer is, we see the concept of the mirror and a person’s reflection being introduced in another way.

Yes. The doctor looking at Darnay’s face and then having such a response suggests some form of connection, ressemblance, or association. Whatever the answer is, we see the concept of the mirror and a person’s reflection being introduced in another way.

Chapter Nine, titled ´The Gorgon’s Head’ opens with a focus on stone and stone heads. Charles Darnay and his uncle confront each other. Perhaps I should say they face each other. Something to consider as we move forward. They are joined by blood and we know that Doctor Manette feels uneasy when he looks at Darnay.

Again, although is a subtle way, we see reflections of people who look like each other.

Again, although is a subtle way, we see reflections of people who look like each other.

The Stoppage at the Fountain

Book II Chapter 7

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"With a wild rattle and clatter, and an inhuman abandonment of consideration not easy to be understood in these days, the carriage dashed through streets and swept round corners, with women screaming before it, and men clutching each other and clutching children out of its way. At last, swooping at a street corner by a fountain, one of its wheels came to a sickening little jolt, and there was a loud cry from a number of voices, and the horses reared and plunged.

But for the latter inconvenience, the carriage probably would not have stopped; carriages were often known to drive on, and leave their wounded behind, and why not? But the frightened valet had got down in a hurry, and there were twenty hands at the horses' bridles.

"What has gone wrong?" said Monsieur, calmly looking out.

A tall man in a nightcap had caught up a bundle from among the feet of the horses, and had laid it on the basement of the fountain, and was down in the mud and wet, howling over it like a wild animal.

"Pardon, Monsieur the Marquis!" said a ragged and submissive man, "it is a child."

"Why does he make that abominable noise? Is it his child?"

"Excuse me, Monsieur the Marquis—it is a pity—yes."

The fountain was a little removed; for the street opened, where it was, into a space some ten or twelve yards square. As the tall man suddenly got up from the ground, and came running at the carriage, Monsieur the Marquis clapped his hand for an instant on his sword-hilt.

"Killed!" shrieked the man, in wild desperation, extending both arms at their length above his head, and staring at him. "Dead!"

The people closed round, and looked at Monsieur the Marquis. There was nothing revealed by the many eyes that looked at him but watchfulness and eagerness; there was no visible menacing or anger. Neither did the people say anything; after the first cry, they had been silent, and they remained so. The voice of the submissive man who had spoken, was flat and tame in its extreme submission. Monsieur the Marquis ran his eyes over them all, as if they had been mere rats come out of their holes.

He took out his purse.

"It is extraordinary to me," said he, "that you people cannot take care of yourselves and your children. One or the other of you is for ever in the way. How do I know what injury you have done my horses. See! Give him that."

He threw out a gold coin for the valet to pick up, and all the heads craned forward that all the eyes might look down at it as it fell. The tall man called out again with a most unearthly cry, "Dead!"

He was arrested by the quick arrival of another man, for whom the rest made way. On seeing him, the miserable creature fell upon his shoulder, sobbing and crying, and pointing to the fountain, where some women were stooping over the motionless bundle, and moving gently about it. They were as silent, however, as the men.

"I know all, I know all," said the last comer. "Be a brave man, my Gaspard! It is better for the poor little plaything to die so, than to live. It has died in a moment without pain. Could it have lived an hour as happily?"

"You are a philosopher, you there," said the Marquis, smiling. "How do they call you?"

"They call me Defarge."

"Of what trade?"

"Monsieur the Marquis, vendor of wine."

"Pick up that, philosopher and vendor of wine," said the Marquis, throwing him another gold coin, "and spend it as you will. The horses there; are they right?"

Without deigning to look at the assemblage a second time, Monsieur the Marquis leaned back in his seat, and was just being driven away with the air of a gentleman who had accidentally broke some common thing, and had paid for it, and could afford to pay for it; when his ease was suddenly disturbed by a coin flying into his carriage, and ringing on its floor.

"Hold!" said Monsieur the Marquis. "Hold the horses! Who threw that?"

He looked to the spot where Defarge the vendor of wine had stood, a moment before; but the wretched father was grovelling on his face on the pavement in that spot, and the figure that stood beside him was the figure of a dark stout woman, knitting.

"You dogs!" said the Marquis, but smoothly, and with an unchanged front, except as to the spots on his nose: "I would ride over any of you very willingly, and exterminate you from the earth. If I knew which rascal threw at the carriage, and if that brigand were sufficiently near it, he should be crushed under the wheels."

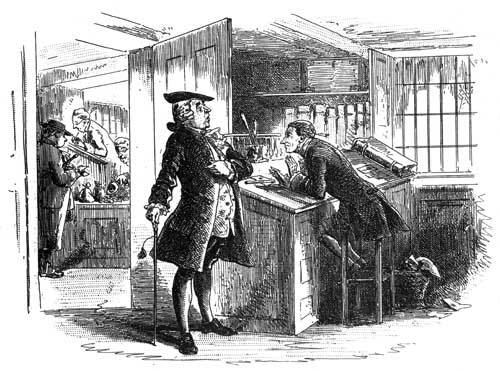

Mr Striver at Tellson's Bank

Book II Chapter 13

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"I am going," said Mr. Stryver, leaning his arms confidentially on the desk: whereupon, although it was a large double one, there appeared to be not half desk enough for him: "I am going to make an offer of myself in marriage to your agreeable little friend, Miss Manette, Mr. Lorry."

"Oh dear me!" cried Mr. Lorry, rubbing his chin, and looking at his visitor dubiously.

"Oh dear me, sir?" repeated Stryver, drawing back. "Oh dear you, sir? What may your meaning be, Mr. Lorry?"

"My meaning," answered the man of business, "is, of course, friendly and appreciative, and that it does you the greatest credit, and—in short, my meaning is everything you could desire. But—really, you know, Mr. Stryver—" Mr. Lorry paused, and shook his head at him in the oddest manner, as if he were compelled against his will to add, internally, "you know there really is so much too much of you!"

"Well!" said Stryver, slapping the desk with his contentious hand, opening his eyes wider, and taking a long breath, "if I understand you, Mr. Lorry, I'll be hanged!"

Mr. Lorry adjusted his little wig at both ears as a means towards that end, and bit the feather of a pen.

"D—n it all, sir!" said Stryver, staring at him, "am I not eligible?"

"Oh dear yes! Yes. Oh yes, you're eligible!" said Mr. Lorry. "If you say eligible, you are eligible."

"Am I not prosperous?" asked Stryver.

"Oh! if you come to prosperous, you are prosperous," said Mr. Lorry.

"And advancing?"

"If you come to advancing you know," said Mr. Lorry, delighted to be able to make another admission, "nobody can doubt that."

"Then what on earth is your meaning, Mr. Lorry?" demanded Stryver, perceptibly crestfallen.

"Well! I—Were you going there now?" asked Mr. Lorry.

"Straight!" said Stryver, with a plump of his fist on the desk.

"Then I think I wouldn't, if I was you."

"Why?" said Stryver. "Now, I'll put you in a corner," forensically shaking a forefinger at him. "You are a man of business and bound to have a reason. State your reason. Why wouldn't you go?"

"Because," said Mr. Lorry, "I wouldn't go on such an object without having some cause to believe that I should succeed."

"D—n me!" cried Stryver, "but this beats everything."

Mr. Lorry glanced at the distant House, and glanced at the angry Stryver.

"Here's a man of business—a man of years—a man of experience—in a Bank," said Stryver; "and having summed up three leading reasons for complete success, he says there's no reason at all! Says it with his head on!" Mr. Stryver remarked upon the peculiarity as if it would have been infinitely less remarkable if he had said it with his head off.

"When I speak of success, I speak of success with the young lady; and when I speak of causes and reasons to make success probable, I speak of causes and reasons that will tell as such with the young lady. The young lady, my good sir," said Mr. Lorry, mildly tapping the Stryver arm, "the young lady. The young lady goes before all."

Commentary:

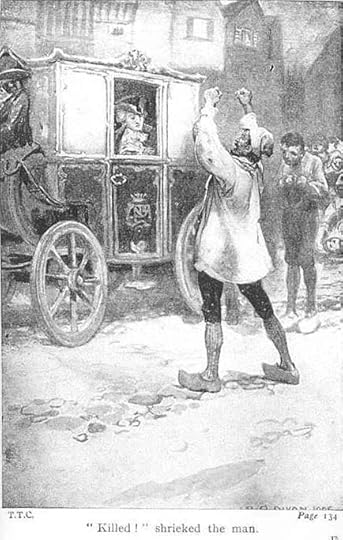

Once again, Browne illustrates incidents from early and late in the instalment, the former an outdoor Paris scene charged with a Baroque sense of movement and drama, the latter a mundane genre scene set indoors in London. In "The Stoppage at The Fountain," the action swirls around twin vortices: to the left, women lament over the dead child in a pose reminiscent of Breughel's Massacre of the Innocents and Giotto's Lamentation over the Dead Christ. The child has been laid at the base of a fountain literally bubbling over with life-giving waters, which pour from the water-pot of the presiding cherub above towards the other putti who support him, the streaming waters complementing the lachrymose state of the chorus of mourners. To the right, the burly Defarge (garbed as in "The Shoemaker," left, but this time facing us) comforts the anguished father, Gaspard, the road-mender whose labours are so necessary to the Marquis's sating his desire for speed. The dead child's lack of animation contrasts the lively poses of the stone cherubs of the gushing fountain, suggestive of an outpouring of tears.

Above the heads of the mixed proletarian and bourgeois crowd the twin towers of Nôtre Dame loom over the shrewd, calculating visage of the Marquis and the disconcerted face of his driver as the horses rear, out of control. Women cry, men gesticulate, while calmly (stage left) the reporter of the ancient regime's wrongs, Madame Defarge, knits the particulars of the incident (especially the name "Evrémonde") into her coded transcript. Above this highly partial recorder of events a lackey regards with apprehension the elements of the crowd outside our field of vision, as if he, the carriage, Monseigneur, and even the horses are about to swept away by the human tidal wave. In a sense, then, the highly dramatic tableau is Phiz's thesis-piece about the causes of the French Revolution: a callous nobility, supported by the established church, oppresses an increasingly restive third estate composed of critical professionals (note the well-dressed bourgeoisie, centre) and emotional proletarians. Phiz has provided his usual symbolic commentary in details of setting: the typical French houses and louvered window-shutters (stage right), the overturned water-pot (indicative of the young life senselessly spilled upon the Paris pavement), and the stone post and chain (stage left). Had the chain been secured, the carriage would not have been free to rattle through the densely populated areas of the capital at top speed, its driver and occupant heedless of pedestrians. Similarly, were France's laws in proper observed and enforced, insensitive noblemen such as the Marquis would not have been able to ride roughshod over the rights of the peasantry.

In the Parisian square, the marble children form a second chorus of grief, their physical contortions reflecting the inward agitation of the tragic chorus of women. In Paris, all faces are animated to suggest discord: accusation, shock, disbelief, and grief are written on all faces but those of the detached observers, the watchful, cold-hearted Marquis and his lower-middle-class counterpart, Madame Defarge. In the Parisian scene, the fountain, the houses, and in particular the clogs clearly establish the scene's context. The clogs, suggestive of social class as well as nationality, are foiled by the adults' shoes and the children's bare feet in the succeeding month's plate. Finally, the overall movement, right to left, is unimpeded in both scenes: the direction as suggested by the faces of all present is reinforced by the horses' heads, left of center.

One wonders to what extent these details and the overall conception of both scenes originated in Browne's imagination rather than Dickens's text. The passage of the Marquis' carriage, for example, is marked by "women screaming before it, and men clutching each other" (Book II, Chapter 7, p. 40), both of which Phiz's Paris scene includes; "there was a loud cry from a number of voices, and the horses reared" seems to be the precise moment that Phiz has chosen to illustrate. However, while Dickens has "twenty hands at the horses' bridles" , Phiz has rendered a single hand, and, more significantly, the "tall man in nightcap" (Gaspard) is not captured in the act of catching up his dead son, depositing the corpse at the fountain's base, and "howling over it like a wild animal." Rather, "some women [are already] stooping over the motionless bundle", "silent, however, as the men." Nowhere in the text does Defarge comfort Gaspard as he does in Phiz's plate. Thus, we can see which textual hints the artist took up, which he disregarded, and how he synthesized several pages of text into a single illustration that impresses its powerful poses and juxtapositions upon the mind of the reader, ready to be called forth in the next month's illustration of a London street scene ("The Spy's Funeral").

In contrast to the violence and emotionalism of "The Stoppage at the Fountain," in "Mr. Stryver at Tellson's Bank" Phiz presents a quiet scene of "business as usual" occupied by just a handful of tranquil individuals: pompous and self-important, meticulously dressed (although slightly overweight and top-heavy), attorney Stryver, a professional like some of the figures in the former plate, chats with Mr. Lorry, perched on his stool in the counting house. Beside the clerk a great ledger, closed, reposes on the long counter; undoubtedly it contains records of recent financial transactions, some of which perhaps involve French clients of the Paris house. Certainly, the recording of discrete moments is common to both the August plates. Behind the seated Lorry's head, eight ledgers of varying height and width attest to the house's prosperity, the result of such transactions as that depicted stage right, where a well- dressed gentleman (again carrying that symbol of patriarchal authority and noble status, a cane) is apparently depositing three bags of coins, which one clerk tells while another — like Lorry, perched on a stool — records. This, then, is the dispassionate counterpart of "The Stoppage at the Fountain," for here the wealth the aristocracy, the results of their abuse of the Social Contract, is tallied by clerks in respectable frock-coats and kept secure by iron bars at the windows.

Headnote Vignette

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities

Harper's Weekly (July 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"At the steepest point of the hill there was a little burial-ground, with a Cross and a new large figure of Our Saviour on it; it was a poor figure in wood, done by some inexperienced rustic carver, but he had studied the figure from the life — his own life, maybe — for it was dreadfully spare and thin."

To this distressful emblem of a great distress that had long been growing worse, and was not at its worst, a woman was kneeling. She turned her head as the carriage came up to her, rose quickly, and presented herself at the carriage-door.

"It is you, Monseigneur! Monseigneur, a petition."

I'm confused with this illustration because it clearly says chapter 7 above the illustration but the text illustrated is from chapter 8. I haven't figured it out yet.

"Killed!" shrieked the man

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter VII, "Monseigneur in Town"

Harper's Weekly (July 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"What has gone wrong?" said Monsieur, calmly looking out.

A tall man in a nightcap had caught up a bundle from among the feet of the horses, and had laid it on the basement of the fountain, and was down in the mud and wet, howling over it like a wild animal.

"Pardon, Monsieur the Marquis!" said a ragged and submissive man, "it is a child."

"Why does he make that abominable noise? Is it his child?"

"Excuse me, Monsieur the Marquis — it is a pity — yes."

The fountain was a little removed; for the street opened, where it was, into a space some ten or twelve yards square. As the tall man suddenly got up from the ground, and came running at the carriage, Monsieur the Marquis clapped his hand for an instant on his sword-hilt.

"Killed!" shrieked the man, in wild desperation, extending both arms at their length above his head, and staring at him. "Dead!"

The people closed round, and looked at Monsieur the Marquis. There was nothing revealed by the many eyes that looked at him but watchfulness and eagerness; there was no visible menacing or anger. Neither did the people say anything; after the first cry, they had been silent, and they remained so. The voice of the submissive man who had spoken, was flat and tame in its extreme submission. Monsieur the Marquis ran his eyes over them all, as if they had been mere rats come out of their holes.

He took out his purse.

"It is extraordinary to me," said he, "that you people cannot take care of yourselves and your children. One or the other of you is for ever in the way. How do I know what injury you have done my horses. See! Give him that."

He threw out a gold coin for the valet to pick up, and all the heads craned forward that all the eyes might look down at it as it fell. The tall man called out again with a most unearthly cry, "Dead!"

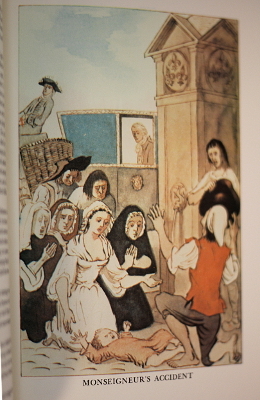

Headnote Vignette

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 9, "The Gorgon's Head"

Harper's Weekly (July 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"Lighter and lighter, until at last the sun touched the tops of the still trees, and poured its radiance over the hill. In the glow, the water of the chateau fountain seemed to turn to blood, and the stone faces crimsoned. The carol of the birds was loud and high, and, on the weather-beaten sill of the great window of the bed- chamber of Monsieur the Marquis, one little bird sang its sweetest song with all its might. At this, the nearest stone face seemed to stare amazed, and, with open mouth and dropped under-jaw, looked awe-stricken."

This text doesn't match the illustration either, I give up.

"This, from Jacques"

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 9 "The Gorgon's Head"

Harper's Weekly ( July 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"All the people of the village were at the fountain, standing about in their depressed manner, and whispering low, but showing no other emotions than grim curiosity and surprise. The led cows, hastily brought in and tethered to anything that would hold them, were looking stupidly on, or lying down chewing the cud of nothing particularly repaying their trouble, which they had picked up in their interrupted saunter. Some of the people of the chateau, and some of those of the posting-house, and all the taxing authorities, were armed more or less, and were crowded on the other side of the little street in a purposeless way, that was highly fraught with nothing. Already, the mender of roads had penetrated into the midst of a group of fifty particular friends, and was smiting himself in the breast with his blue cap. What did all this portend, and what portended the swift hoisting-up of Monsieur Gabelle behind a servant on horseback, and the conveying away of the said Gabelle (double-laden though the horse was), at a gallop, like a new version of the German ballad of Leonora?

It portended that there was one stone face too many, up at the chateau.

The Gorgon had surveyed the building again in the night, and had added the one stone face wanting; the stone face for which it had waited through about two hundred years.

It lay back on the pillow of Monsieur the Marquis. It was like a fine mask, suddenly startled, made angry, and petrified. Driven home into the heart of the stone figure attached to it, was a knife. Round its hilt was a frill of paper, on which was scrawled:

"Drive him fast to his tomb. This, from Jacques."

Headnote Vignette

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 10, "Two Promises"

Harper's Weekly (July 1869)

Text Illustrated:

"It was dark when Charles Darnay left him, and it was an hour later and darker when Lucie came home; she hurried into the room alone—for Miss Pross had gone straight up-stairs—and was surprised to find his reading-chair empty.

"My father!" she called to him. "Father dear!"

Nothing was said in answer, but she heard a low hammering sound in his bedroom. Passing lightly across the intermediate room, she looked in at his door and came running back frightened, crying to herself, with her blood all chilled, "What shall I do! What shall I do!"

Her uncertainty lasted but a moment; she hurried back, and tapped at his door, and softly called to him. The noise ceased at the sound of her voice, and he presently came out to her, and they walked up and down together for a long time.

She came down from her bed, to look at him in his sleep that night. He slept heavily, and his tray of shoemaking tools, and his old unfinished work, were all as usual.

"He stooped a little"

Book II Chapter 8

Fred Barnard

Household Edition 1870s

Text Illustrated:

"Monsieur the Marquis cast his eyes over the submissive faces that drooped before him, as the like of himself had drooped before Monseigneur of the Court—only the difference was, that these faces drooped merely to suffer and not to propitiate—when a grizzled mender of the roads joined the group.

"Bring me hither that fellow!" said the Marquis to the courier.

The fellow was brought, cap in hand, and the other fellows closed round to look and listen, in the manner of the people at the Paris fountain.

"I passed you on the road?"

"Monseigneur, it is true. I had the honour of being passed on the road."

"Coming up the hill, and at the top of the hill, both?"

"Monseigneur, it is true."

"What did you look at, so fixedly?"

"Monseigneur, I looked at the man."

He stooped a little, and with his tattered blue cap pointed under the carriage. All his fellows stooped to look under the carriage.

"What man, pig? And why look there?"

"Pardon, Monseigneur; he swung by the chain of the shoe—the drag."

"Who?" demanded the traveller.

"Monseigneur, the man."

"May the Devil carry away these idiots! How do you call the man? You know all the men of this part of the country. Who was he?"

"Your clemency, Monseigneur! He was not of this part of the country. Of all the days of my life, I never saw him."

"Swinging by the chain? To be suffocated?"

"With your gracious permission, that was the wonder of it, Monseigneur. His head hanging over—like this!"

He turned himself sideways to the carriage, and leaned back, with his face thrown up to the sky, and his head hanging down; then recovered himself, fumbled with his cap, and made a bow.

"What was he like?"

"Monseigneur, he was whiter than the miller. All covered with dust, white as a spectre, tall as a spectre!"

Commentary:

The contemptuous visage of the Marquis St. Evrémonde. — scowling at the interruption of his journey from the metropolis to his country chateau — competes for the viewer's attention at the centre of Barnard's composition with the questioning expressions of the peasantry surrounding the carriage in the square of the little village, in front of the posting-house gate beside the fountain, neither of which is in evidence in Barnard's ninth illustration. Barnard's lengthy title points to this specific moment in the text. Accosting the grizzled road-mender who has just joined the phlegmatic group looking under the carriage, the Marquis interrogates him:

"What did you look at so fixedly?"

"Monseigneur, I looked at the man."

He stooped a little, and with his tattered blue cap pointed under the carriage. All his fellows stooped to look under the carriage.

"What man, pig? And why look there?"

"Pardon, Monseigneur; he swung by the chain of the shoe — the drag."

Barnard probably concluded, after reviewing the original 1859 steel engravings, that it would be difficult to compete with Phiz's "The Stoppage at the Fountain" with its seething mob, rearing horses, and moment of high melodrama as the insensitive aristocrat's encouraging his driver to race through the crowded streets of St. Antoine has resulted in a child's death. Instead, realizing a moment in Chapter 8, "Monseigneur in the Country," of Book the Second, "The Golden Thread," Barnard elected to reinforce the moment of the Marquis' discovering that he has been carrying a hitchhiker under his carriage. The reader studies the reaction of the villagers near the Marquis' chateau and ponders why a denizen of St. Antoine has chosen to follow Monseigneur from town by so dangerous an expedient. Whereas Phiz's dual focus in is the group of grieving women at the fountain (left) and the Marquis' surveying the distraught father, Gaspard, and his comforter, Defarge (right), in a swirling vortex of action and raw emotion, Barnard's scene, showing the horses as entirely tranquil, is far more mundane: there is no social tragedy, no sudden loss of life, just a small mystery.

A detail wholly consistent with the text is that the man who is holding his cap in his right hand as he points downward with his left (left of center) has been brought forward by a fashionably attired courier, who has removed his own tricorn hat as the Marquis addresses the peasant in his charge. A detail not mentioned by Dickens but consistent with the fashions of the countryside in eighteenth-century France is the wooden shoes worn by the nine villagers. Although their presence on the horses is entirely logical in Barnard's woodcut, Dickens does not mention the Marquis' having mounted postilions accompanying him. In this respect, Phiz's illustration more closely follows the text in depicting a driver, a pair of horses harnessed side-by-side, and a courier at the very back of the carriage. However, whereas Phiz in "The Stoppage at the Fountain" as a visual complement to the seventh chapter, "Monseigneur in Town," had emphasized the rearing horses to further energize the scene, Barnard has effectively realized the ornately trimmed carriage of the Marquis, a shield with a cross on it ironically commenting on the owner's lack of Christian charity and also suggesting a connection with England as the decoration approximately the shield of St. George.

Curiously, in the Harper's serialization, John McLenan expressed little interest in the Marquis and his carriage, which is depicted in very small scale in the background of the headnote vignette for 2 July 1859, Chapter 7, "Monseigneur in Town.

"Drive him fast to his tomb. This, from Jacques"

Book II Chapter 9

Fred Barnard

Household Edition 1870s

Text Illustrated:

"The chateau awoke later, as became its quality, but awoke gradually and surely. First, the lonely boar-spears and knives of the chase had been reddened as of old; then, had gleamed trenchant in the morning sunshine; now, doors and windows were thrown open, horses in their stables looked round over their shoulders at the light and freshness pouring in at doorways, leaves sparkled and rustled at iron-grated windows, dogs pulled hard at their chains, and reared impatient to be loosed.

All these trivial incidents belonged to the routine of life, and the return of morning. Surely, not so the ringing of the great bell of the chateau, nor the running up and down the stairs; nor the hurried figures on the terrace; nor the booting and tramping here and there and everywhere, nor the quick saddling of horses and riding away?

What winds conveyed this hurry to the grizzled mender of roads, already at work on the hill-top beyond the village, with his day's dinner (not much to carry) lying in a bundle that it was worth no crow's while to peck at, on a heap of stones? Had the birds, carrying some grains of it to a distance, dropped one over him as they sow chance seeds? Whether or no, the mender of roads ran, on the sultry morning, as if for his life, down the hill, knee-high in dust, and never stopped till he got to the fountain.

All the people of the village were at the fountain, standing about in their depressed manner, and whispering low, but showing no other emotions than grim curiosity and surprise. The led cows, hastily brought in and tethered to anything that would hold them, were looking stupidly on, or lying down chewing the cud of nothing particularly repaying their trouble, which they had picked up in their interrupted saunter. Some of the people of the chateau, and some of those of the posting-house, and all the taxing authorities, were armed more or less, and were crowded on the other side of the little street in a purposeless way, that was highly fraught with nothing. Already, the mender of roads had penetrated into the midst of a group of fifty particular friends, and was smiting himself in the breast with his blue cap. What did all this portend, and what portended the swift hoisting-up of Monsieur Gabelle behind a servant on horseback, and the conveying away of the said Gabelle (double-laden though the horse was), at a gallop, like a new version of the German ballad of Leonora?

It portended that there was one stone face too many, up at the chateau.

The Gorgon had surveyed the building again in the night, and had added the one stone face wanting; the stone face for which it had waited through about two hundred years.

It lay back on the pillow of Monsieur the Marquis. It was like a fine mask, suddenly startled, made angry, and petrified. Driven home into the heart of the stone figure attached to it, was a knife. Round its hilt was a frill of paper, on which was scrawled:

"Drive him fast to his tomb. This, from Jacques."

Commentary:

Whereas Phiz had elected, perhaps at Dickens's instruction, not to attempt this moment for illustration in his series for the monthly part-publication (June through December 1859), John McLenan in his extensive series for the Harper's Weekly serialization had realized the moment at which some servant discovers the body of the Marquis in bed, an ornate screen partially obscuring our view of the body. In contrast, Barnard focuses on that beautiful face, devoid of the bitterness and malignancy that distorted that visage in life. Instead of deploying a symbolic object such as McLenan's eighteenth-century, Louis XV Chinoiserie screen in "This, from Jacques", Barnard conveys the context — the Marquis' affluent lifestyle supported by the labors of a downtrodden peasantry — by the elaborately decorated headboard, bedspread, and ruffled nightgown. An interesting touch is Barnard's transforming the note left by "Jacques" from Dickensian Franglais into actual French, albeit a fragmentary sentence ("Cecide"). Whereas McLenan contrasts the beauty of the natural world of bird song and vines in the headnote vignette for "The Gorgon's Head" with the artifice and luxury of the interior of the Marquis bed chamber in "This, from Jacques," showing the dead man from a distance (suggesting the perspective the nameless servant who discovers the corpse the next morning), Barnard zooms in for a close-up, and thereby humanizes and particularizes the victim of Nemesis. Barnard subtly contrasts the acidic personality of the Marquis, which Dickens has revealed so ably through description, narration, and dialogue, with his outward, physical beauty, as if he himself is a work of art. For the sake of visual continuity, Barnard reintroduces the ornamentation evident in the headboard and the swirling patterns and movements in the coverlet in the next illustration, specifically in the screen behind Lucie Manette and in her skirt, respectively.

"...there is a man who would give his life"

Book II Chapter 13

Fred Barnard

The Household Edition 1870s

Text Illustrated:

"Entreat me to believe it no more, Miss Manette. I have proved myself, and I know better. I distress you; I draw fast to an end. Will you let me believe, when I recall this day, that the last confidence of my life was reposed in your pure and innocent breast, and that it lies there alone, and will be shared by no one?"

"If that will be a consolation to you, yes."

"Not even by the dearest one ever to be known to you?"

"Mr. Carton," she answered, after an agitated pause, "the secret is yours, not mine; and I promise to respect it."

"Thank you. And again, God bless you."

He put her hand to his lips, and moved towards the door.

"Be under no apprehension, Miss Manette, of my ever resuming this conversation by so much as a passing word. I will never refer to it again. If I were dead, that could not be surer than it is henceforth. In the hour of my death, I shall hold sacred the one good remembrance—and shall thank and bless you for it—that my last avowal of myself was made to you, and that my name, and faults, and miseries were gently carried in your heart. May it otherwise be light and happy!"

He was so unlike what he had ever shown himself to be, and it was so sad to think how much he had thrown away, and how much he every day kept down and perverted, that Lucie Manette wept mournfully for him as he stood looking back at her.

"Be comforted!" he said, "I am not worth such feeling, Miss Manette. An hour or two hence, and the low companions and low habits that I scorn but yield to, will render me less worth such tears as those, than any wretch who creeps along the streets. Be comforted! But, within myself, I shall always be, towards you, what I am now, though outwardly I shall be what you have heretofore seen me. The last supplication but one I make to you, is, that you will believe this of me."

"I will, Mr. Carton."

"My last supplication of all, is this; and with it, I will relieve you of a visitor with whom I well know you have nothing in unison, and between whom and you there is an impassable space. It is useless to say it, I know, but it rises out of my soul. For you, and for any dear to you, I would do anything. If my career were of that better kind that there was any opportunity or capacity of sacrifice in it, I would embrace any sacrifice for you and for those dear to you. Try to hold me in your mind, at some quiet times, as ardent and sincere in this one thing. The time will come, the time will not be long in coming, when new ties will be formed about you—ties that will bind you yet more tenderly and strongly to the home you so adorn—the dearest ties that will ever grace and gladden you. O Miss Manette, when the little picture of a happy father's face looks up in yours, when you see your own bright beauty springing up anew at your feet, think now and then that there is a man who would give his life, to keep a life you love beside you!"

He said, "Farewell!" said a last "God bless you!" and left her."

Commentary:

Dickens has the hapless alcoholic whose addiction has blighted his personal and private lives, Sydney Carton, reveal his complete devotion to the beautiful young woman who is another's, Lucie Manette, Book the Second, "The Golden Thread," ch. 13, "The Fellow of No Delicacy." The dissolute attorney Sydney Carton (right) has just confessed his undying devotion for the beautiful Anglo-French physician's daughter Lucie Manette, her blond innocence and age reflecting perhaps those of Dickens's mistress, Ellen Ternan.

The "confession" that the dissipated attorney makes reveals the source of Dickens's inspiration for the novel, namely the role of Richard Wardour, the thwarted lover of Wilkie Collins's The Frozen Deep, first performed on 6 January 1857 for a select audience in the converted schoolroom of Dickens's London residence, Tavistock House. Dickens so strongly identified himself with the self-sacrificing, volatile hero of the play, that the role of Wardour contributed directly to his characterization of Sydney Carton, whose original Christian name ("Dick") points to the emotional connection, the initials "DC" being an inversion of Dickens's own. Indeed, he even confessed the connection between the novel and Collins's play in the "Preface":

"When I was acting with my children and friends, in Mr. Wilkie Collins's drama of The Frozen Deep, I first conceived the main idea of this story. A strong desire was upon me then to embody it in my own person; and I traced out in my fancy the state of mind of which it would necessitate the presentation to an observant spectator, with particular care and interest."

Rather than offering us a close up of Carton as he has just done of the Marquis in the previous illustration, Barnard stages the dialogue in a comfortably furnished eighteenth-century drawing-room. Lucie's embroidery on its frame is before her, and she and Carton are dressed in the upper-middle-class fashions of the mid-eighteenth century. She listens to him with rapt seriousness as he stands at the door, ready to depart to a life devoid of love and the domestic felicities he so earnestly and pointlessly desires to share with Lucie. Her ornately patterned dress and the screen behind her establish a visual continuity with the previous plate's pillows, headboard, and coverlet. The svelte figure, emaciated visage, and elegant figure of Carton imply his status as a Byronic hero, a handsome but embittered young man whose past harbors some terrible, dark secret, as is the case with "The Master of Thornfield," Edward Rochester, in Jane Eyre, a best-seller of the previous decade. Neither Carton nor Lucie is particularized in the original serial illustrations, Lucie Manette being a stock Phiz figure of slender-wasted, delicate feminine beauty in "The Knock at the Door," in Book Three, Chapter 7 (for November, 1859).

"Charles Darnay and The Marquis"

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Book II Chapter 9

Diamond Edition of Dicken's works 1867

Commentary: