The Old Curiosity Club discussion

A Tale of Two Cities

>

Book Two Chp 19-24

Chapter 20

A Plea

“Mr Darnay,” said Carton, “I wish we might be friends.”

When Lucie and Charles return from their honeymoon the first person to appear and offer congratulations is Sydney Carton. Dickens describes Sydney as having “a certain air of fidelity.” I find this an interesting description. Generally, Sydney has been presented as being sloppy, slovenly, dishevelled, and seemingly always at least a bit drunk. The choice of the word “fidelity” is intriguing. I think Dickens used it with great precision. Fidelity is not something one can see easily, or at all. It is not a physical trait. How often do we initially judge a person by their looks? Too often, I fear, myself certainly included. Sydney hopes that Charles will not judge him.

Now, as their conversation carries on it becomes (with a nod to Lewis Carroll), ‘curiouser and curiouser.” Sydney asks if he can drop by to visit Darnay and Lucie and be considered “a privileged person.” Carton assures Darnay he will not “abuse the permission.” Carton and Darnay agree and shake hands. “Within a minute afterwards” we read that Sydney was, “to all outward appearance, as unsubstantial as ever.” Now, I don’t know about you but I found their entire conversation unusual. Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton are polar opposites. They speak, present themselves, think, and act in totally different ways. However, their outward physical appearance is strikingly similar. Indeed, it is because of their similar physical appearance that Darnay was “recalled to life.” Ah, that phrase again! The way Sydney looks is the sole reason Darnay is still alive.

Later in the evening, after Carton had left, Miss Pross, the Doctor, Mr Lorry, and Charles Darnay speak about Carton as a “problem of carelessness and recklessness.” When Charles and Lucie are alone Charles notices Lucie is rather pensive. He asks why. Lucie asks her husband not to press any question on her if she tells Charles what is on her mind. Charles agrees. Lucie then says that Sydney Carton deserves more “consideration and respect” and that Charles should always be “generous with him … and very lenient of his faults when he is not by. I would ask you to believe that he has a heart he very, very seldom reveals, and that there are deep, wounds in it.” My dear,” continues Lucie, “I have seen it bleeding.” Lucie concludes by saying “I am sure that he is capable of good things, gentle things, even magnanimous things.” Charles Darnay responds by telling Lucie “I will always remember it, dear Heart! I will remember it as long as I live.” Ah, Curiosities, remember those words.

Thoughts

I have quoted from the text a great deal in this chapter. In the chapter Dickens brings Sydney Carton and Charles Darnay to the front of the stage. Surely there must be some reason for it in the narrative. The third component, and important character in this chapter, is Lucie. Once again, Dickens demonstrates Lucie’s compassion, sensitivity, and intuitive nature. For those who see Dickens reaching into his bag of sugary treats once again when he is writing about Lucie, you are right. Some of us may be tempted to pull out our hair. Little Nell, Little Dorrit, Florence, Dora, and now, even more so, Lucie. Shouldn’t Dickens be able by this time to develop more rounded young females, more psychologically interesting heroines? This question will follow us forever.

A Plea

“Mr Darnay,” said Carton, “I wish we might be friends.”

When Lucie and Charles return from their honeymoon the first person to appear and offer congratulations is Sydney Carton. Dickens describes Sydney as having “a certain air of fidelity.” I find this an interesting description. Generally, Sydney has been presented as being sloppy, slovenly, dishevelled, and seemingly always at least a bit drunk. The choice of the word “fidelity” is intriguing. I think Dickens used it with great precision. Fidelity is not something one can see easily, or at all. It is not a physical trait. How often do we initially judge a person by their looks? Too often, I fear, myself certainly included. Sydney hopes that Charles will not judge him.

Now, as their conversation carries on it becomes (with a nod to Lewis Carroll), ‘curiouser and curiouser.” Sydney asks if he can drop by to visit Darnay and Lucie and be considered “a privileged person.” Carton assures Darnay he will not “abuse the permission.” Carton and Darnay agree and shake hands. “Within a minute afterwards” we read that Sydney was, “to all outward appearance, as unsubstantial as ever.” Now, I don’t know about you but I found their entire conversation unusual. Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton are polar opposites. They speak, present themselves, think, and act in totally different ways. However, their outward physical appearance is strikingly similar. Indeed, it is because of their similar physical appearance that Darnay was “recalled to life.” Ah, that phrase again! The way Sydney looks is the sole reason Darnay is still alive.

Later in the evening, after Carton had left, Miss Pross, the Doctor, Mr Lorry, and Charles Darnay speak about Carton as a “problem of carelessness and recklessness.” When Charles and Lucie are alone Charles notices Lucie is rather pensive. He asks why. Lucie asks her husband not to press any question on her if she tells Charles what is on her mind. Charles agrees. Lucie then says that Sydney Carton deserves more “consideration and respect” and that Charles should always be “generous with him … and very lenient of his faults when he is not by. I would ask you to believe that he has a heart he very, very seldom reveals, and that there are deep, wounds in it.” My dear,” continues Lucie, “I have seen it bleeding.” Lucie concludes by saying “I am sure that he is capable of good things, gentle things, even magnanimous things.” Charles Darnay responds by telling Lucie “I will always remember it, dear Heart! I will remember it as long as I live.” Ah, Curiosities, remember those words.

Thoughts

I have quoted from the text a great deal in this chapter. In the chapter Dickens brings Sydney Carton and Charles Darnay to the front of the stage. Surely there must be some reason for it in the narrative. The third component, and important character in this chapter, is Lucie. Once again, Dickens demonstrates Lucie’s compassion, sensitivity, and intuitive nature. For those who see Dickens reaching into his bag of sugary treats once again when he is writing about Lucie, you are right. Some of us may be tempted to pull out our hair. Little Nell, Little Dorrit, Florence, Dora, and now, even more so, Lucie. Shouldn’t Dickens be able by this time to develop more rounded young females, more psychologically interesting heroines? This question will follow us forever.

Chapter 21

Echoing Footsteps

“Headlong, mad, and dangerous footsteps to force their way into anybody’s life, footsteps not easily made clean again if once stained red, the footsteps raging in Saint Antoine afar off, as the little circle sat in the dark London window.”

This chapter opens at the London residence of Lucie, Charles, and Dr Manette where Lucie is “listening to the echoing footsteps.” Do you recall how an earlier chapter placed us at the Manette residence and Lucie heard the sounds of hundreds of footsteps which upset her? Sydney Carton told her he hoped the footsteps would not come into her life but yet again we are told “there was something coming in the echoes, something light, afar off, and scarcely audible yet.” We are told that for years the echoes Lucie hears were none but friendly and “soothing sounds.” Suspense and foreshadowing. There must be something horrific on its way as Dickens repeatedly makes references to footsteps.

We learn that Lucie and Charles have a young daughter. The years are passing. We learn that Charles and Lucie also had a son but he died. Sounds, more sounds. We learn that Sydney Carton was the first visiter baby Lucie held her “chubby arms” out to in life. We learn that Stryver is now married but has remained as odious as earlier in the novel.

We also learn that in France, about the time of little Lucie’s sixth birthday, there was an “awful sound, as of a great storm in France with a dreadful sea rising.” In mid July, 1789, we find Jarvis Lorry making plans to go to France. France is in turmoil. At this point in the letterpress there is a page break.

We next read that “headlong, mad, and dangerous footsteps to force their way into anybody’s life, footsteps not easily made clean again if once stained red, the footsteps raging in Saint Antoine afar off, as the little circle sat in the dark London window.” Remember the spilt wine cask in Saint Antoine? The desperate people licking the wine from the street’s gutters, chewing the wood of the broken wine casks, and one joker writing “Blood” on the wall of a building.

Dickens brings the French Revolution to his readers through the actions of the poor in the area of Saint Antoine. The poor grab weapons, stones, anything, everything, and were prepared to hold their life “to no account.” A “whirlpool of boiling waters” flooded out from the Defarge’s wine shop. “Come then!” cried Defarge, in a resounding voice ‘Patriots and friends, we are ready! The Bastille!’”

And so the French Revolution begins. I will not present a summary of the next paragraphs except to note that we are told the Defarge’s “had long grown hot.” I will pause, however, at one specific jail cell in The Bastille. One Hundred and Five, North Tower. Defarge demands that a turnkey pass his torch along the walls of the cell so he can see them clearly. On the wall is discovered the letters AM and the words “a poor physician.” The revolutionaries lead by Defarge search the cell but apparently find nothing.

There is violence and death in the streets. The revolutionaries show no mercy. No one is more destructive than Madame Defarge. What is it that drives such hate in her? Has there been any hints to date you can recall? Seven prisoners have been released and seven dead heads suspended on pikes. We are told that the revolutionaries had found some letters and other memorials of the prisoners.

As our chapter ends we find a prayer that Lucie will never be accosted by the footsteps that have erupted in Paris. Will Lucie be able to avoid the wine-red stains that ran years earlier through Saint Antoine?

Thoughts

We now have an answer to what the mysterious footsteps that Lucie has heard for years. But how can we link two such seemingly different and widely placed events? What/who is the link?

The events of the French Revolution had been a long time coming. Dickens has marked the time interval carefully. Why do you think Dickens did not introduce his reader to the French Revolution until this point in the text?

To what extent has Dickens been able to keep the reader’s attention to this point in the novel? What are the ways he has accomplished it?

Echoing Footsteps

“Headlong, mad, and dangerous footsteps to force their way into anybody’s life, footsteps not easily made clean again if once stained red, the footsteps raging in Saint Antoine afar off, as the little circle sat in the dark London window.”

This chapter opens at the London residence of Lucie, Charles, and Dr Manette where Lucie is “listening to the echoing footsteps.” Do you recall how an earlier chapter placed us at the Manette residence and Lucie heard the sounds of hundreds of footsteps which upset her? Sydney Carton told her he hoped the footsteps would not come into her life but yet again we are told “there was something coming in the echoes, something light, afar off, and scarcely audible yet.” We are told that for years the echoes Lucie hears were none but friendly and “soothing sounds.” Suspense and foreshadowing. There must be something horrific on its way as Dickens repeatedly makes references to footsteps.

We learn that Lucie and Charles have a young daughter. The years are passing. We learn that Charles and Lucie also had a son but he died. Sounds, more sounds. We learn that Sydney Carton was the first visiter baby Lucie held her “chubby arms” out to in life. We learn that Stryver is now married but has remained as odious as earlier in the novel.

We also learn that in France, about the time of little Lucie’s sixth birthday, there was an “awful sound, as of a great storm in France with a dreadful sea rising.” In mid July, 1789, we find Jarvis Lorry making plans to go to France. France is in turmoil. At this point in the letterpress there is a page break.

We next read that “headlong, mad, and dangerous footsteps to force their way into anybody’s life, footsteps not easily made clean again if once stained red, the footsteps raging in Saint Antoine afar off, as the little circle sat in the dark London window.” Remember the spilt wine cask in Saint Antoine? The desperate people licking the wine from the street’s gutters, chewing the wood of the broken wine casks, and one joker writing “Blood” on the wall of a building.

Dickens brings the French Revolution to his readers through the actions of the poor in the area of Saint Antoine. The poor grab weapons, stones, anything, everything, and were prepared to hold their life “to no account.” A “whirlpool of boiling waters” flooded out from the Defarge’s wine shop. “Come then!” cried Defarge, in a resounding voice ‘Patriots and friends, we are ready! The Bastille!’”

And so the French Revolution begins. I will not present a summary of the next paragraphs except to note that we are told the Defarge’s “had long grown hot.” I will pause, however, at one specific jail cell in The Bastille. One Hundred and Five, North Tower. Defarge demands that a turnkey pass his torch along the walls of the cell so he can see them clearly. On the wall is discovered the letters AM and the words “a poor physician.” The revolutionaries lead by Defarge search the cell but apparently find nothing.

There is violence and death in the streets. The revolutionaries show no mercy. No one is more destructive than Madame Defarge. What is it that drives such hate in her? Has there been any hints to date you can recall? Seven prisoners have been released and seven dead heads suspended on pikes. We are told that the revolutionaries had found some letters and other memorials of the prisoners.

As our chapter ends we find a prayer that Lucie will never be accosted by the footsteps that have erupted in Paris. Will Lucie be able to avoid the wine-red stains that ran years earlier through Saint Antoine?

Thoughts

We now have an answer to what the mysterious footsteps that Lucie has heard for years. But how can we link two such seemingly different and widely placed events? What/who is the link?

The events of the French Revolution had been a long time coming. Dickens has marked the time interval carefully. Why do you think Dickens did not introduce his reader to the French Revolution until this point in the text?

To what extent has Dickens been able to keep the reader’s attention to this point in the novel? What are the ways he has accomplished it?

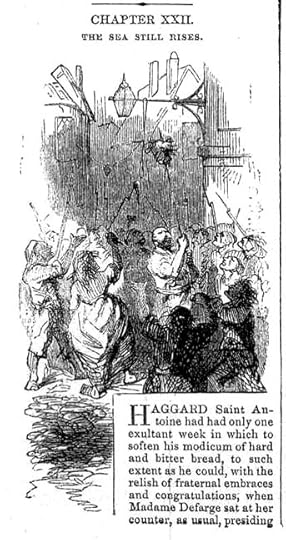

Chapter 22

The Sea Still Rises

“Haggard Saint Antoine had had only one exultant week, in which to soften his modicum of hard and bitter bread to such extent as he could, with the relish of fraternal embraces and congratulations…”

The above epigraph is the first sentence of this chapter. Did you notice the words ‘his,” “he” and “fraternal embraces” used to describe Saint Antoine? And, of course, a place cannot eat bread. The place and the people are made one by Dickens. The last sentence of the first paragraph states “the lamps across his streets had a portentously elastic swing with them.” I wonder how many people were hanged from those lamps?

There has been a shift in mood in Saint Antoine. It is now termed a “power enthroned.” Do you think Dickens would use the word “enthroned” to suggest the shift from the throne once so comfortably occupied by the kings of France?

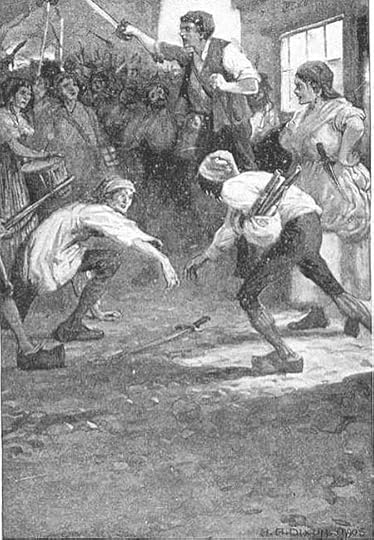

In this chapter we meet the wife of a starved grocer named “The Vengeance.” Keep an eye on her as the novel progresses. Defarge comes to the wine-shop and announces that he has news from “the other world.” A hated member of the elite named Foulon, a man who had once told the poor to eat grass, and who was supposedly dead is, in fact, not dead. He feigned his death in order to avoid the wrath of the poor. Well, he is, in fact alive. Here I go again … Foulon is yet another example of a person who has been Recalled to Life.

The residents rally together, arm themselves, and go to the Hall of Examination to see Foulon. The group intend to find Foulon and then hang him from a lamppost. They do seize him, drag him into the streets, stuff his face with straw and attempt to hang him. Twice the rope breaks. The third time is the charm. The mob from Saint Antoine are successful in hanging Foulon but I fear they will not be satisfied with only his death. Dickens calls the mob a “Wolf-procession.”

As our chapter ends we find Madame Defarge and her husband remarking on how their long wait for justice has been. The Bastille has fallen, Foulon has been killed. What else, who else, will be next?

Thoughts

The title of the novel is A Tale of Two Cities. First, we need to reflect once more on the opening chapter of this novel. I’ll pose a couple of contrasts and comparisons. We have a seemingly idyllic couple in London and an angry and bitter couple in Paris. We have a court system in England that seems to ignore the due process of law and a group of citizens who enjoy the spectacle of drawing and quartering humans. Dickens calls them flies. In France, we have a group of citizens who enjoy beating and old man and then hanging him from a lamppost. Can you think of other similarities and differences between France and England?

The concept of being recalled to life is once again in evidence in this chapter. This motif seems to be constant. What might Dickens be preparing us for with such a constant repetition?

The Sea Still Rises

“Haggard Saint Antoine had had only one exultant week, in which to soften his modicum of hard and bitter bread to such extent as he could, with the relish of fraternal embraces and congratulations…”

The above epigraph is the first sentence of this chapter. Did you notice the words ‘his,” “he” and “fraternal embraces” used to describe Saint Antoine? And, of course, a place cannot eat bread. The place and the people are made one by Dickens. The last sentence of the first paragraph states “the lamps across his streets had a portentously elastic swing with them.” I wonder how many people were hanged from those lamps?

There has been a shift in mood in Saint Antoine. It is now termed a “power enthroned.” Do you think Dickens would use the word “enthroned” to suggest the shift from the throne once so comfortably occupied by the kings of France?

In this chapter we meet the wife of a starved grocer named “The Vengeance.” Keep an eye on her as the novel progresses. Defarge comes to the wine-shop and announces that he has news from “the other world.” A hated member of the elite named Foulon, a man who had once told the poor to eat grass, and who was supposedly dead is, in fact, not dead. He feigned his death in order to avoid the wrath of the poor. Well, he is, in fact alive. Here I go again … Foulon is yet another example of a person who has been Recalled to Life.

The residents rally together, arm themselves, and go to the Hall of Examination to see Foulon. The group intend to find Foulon and then hang him from a lamppost. They do seize him, drag him into the streets, stuff his face with straw and attempt to hang him. Twice the rope breaks. The third time is the charm. The mob from Saint Antoine are successful in hanging Foulon but I fear they will not be satisfied with only his death. Dickens calls the mob a “Wolf-procession.”

As our chapter ends we find Madame Defarge and her husband remarking on how their long wait for justice has been. The Bastille has fallen, Foulon has been killed. What else, who else, will be next?

Thoughts

The title of the novel is A Tale of Two Cities. First, we need to reflect once more on the opening chapter of this novel. I’ll pose a couple of contrasts and comparisons. We have a seemingly idyllic couple in London and an angry and bitter couple in Paris. We have a court system in England that seems to ignore the due process of law and a group of citizens who enjoy the spectacle of drawing and quartering humans. Dickens calls them flies. In France, we have a group of citizens who enjoy beating and old man and then hanging him from a lamppost. Can you think of other similarities and differences between France and England?

The concept of being recalled to life is once again in evidence in this chapter. This motif seems to be constant. What might Dickens be preparing us for with such a constant repetition?

Chapter 23

Fire Rises

“… flames burst forth, and the stone faces awakened, stared out of fire.”

For those of us who have had the pleasure to travel in Europe we have, no doubt, learned that the city or rural fountain is a fixture of life. My wife comes from a rural area of Portugal and in her childhood town there still is a fountain where people go for their water needs. She remembers going to the fountain daily with her father. She recalls how the people would gather to visit, to talk, and to be with their neighbours. Today the townspeople still gather at the fountain. Like outdoor coffee shops, the town fountain serves as a heartbeat for the people.

In this chapter we are in the countryside. The area is “all worn out.” We read that “Monseigneur as a class, somehow or other, brought things to this.” The mender of roads worked, solitary, in the dust. He is starving. As he works breaking stones for the roads, I see a metaphor the state of France. It too is broken. The poor have no road to take to a better life. One day a man comes upon the road mender “like a ghost” and both men great each other as Jacques. As they settle in to talk the word “To-night” enters the conversation. As they talk we are told that they sat “on a heap of stones” while “hail [drove] in between them like a pigmy charge of bayonets, until the sky began to clear over the village.” Ah, hail, an unpleasant weather event, surrounds the men. What is going on here? Remember that Dickens frequently used pathetic fallacy to heighten the essence of warnings in his narratives.

The wayfarer is in need of sleep and so he prepares to rest. We are told he “slipped off his great wooden shoes.” The mention of wooden shoes emphasizes he is a very poor man. It also links back to the sound heard when hundreds, indeed thousands of pairs of wooden shoes ran through the streets of France and were imagined by Lucie in her quiet corner of London. The road mender looks at the sleeping man. Let’s look at what he sees. The wayfarer “had travelled far, and his feet were footsore, and his ankles chafed and bleeding; his great shoes, stuffed with leaves and grass, had been heavy to drag over the many long leagues and his clothes were chafed into holes, as he himself was into sores.” The road mender sees in his mind “similar figures, stopped by no obstacle, tending to centres all over France.”

Why does Dickens focus on the man’s shoes? If we look back to Browne’s illustration of the dead child who was run over by the Marquis’s carriage found in Book 2 Chapters 7-13 message 40 the role of wooden shoes is discussed. Here again, in this chapter, Dickens focusses on shoes. Dickens is a master of building and repeating symbols. In this chapter he first reintroduces the wooden shoe. This time, however, Dickens looks closely at the feet of the poor man. Closer and closer. What do we see? Poverty and pain. Our first look at Doctor Manette reveals him at a workbench working on a shoe. Over and over Dickens weaves the idea of shoes, footprints, and sounds of feet into the text.

The wayfarer leaves, the road-mender goes home to the village. After his meal the road mender and the rest of the town gather around the town fountain and look to the sky . Why?

Dickens then abruptly changes our point of view to the chateau of the former Marquis. First, it is dark. Then, the chateau seems to become visible “by some light of its own.” Monsieur Gabelle sees the fire but can find no one to help as “the mender of roads and two hundred and fifty particular friends, stood with folded arms at the fountain.” The chateau burned. It was totally destroyed. The fountain of the chateau “ran dry.” As we look towards the massive destruction of the chateau there are “four fierce figures” who trudged away “towards their next destination.” Clearly, there is a select group of men who travel about France destroying the property of the aristocracy.

The townspeople turn on Gabelle who they saw as a tax collector. For the time being his life appears to be spared. As our chapter ends we read that the horrors of the Revolution are spreading throughout France. It seems no one was exempt from the grind of death and destruction.

Fire Rises

“… flames burst forth, and the stone faces awakened, stared out of fire.”

For those of us who have had the pleasure to travel in Europe we have, no doubt, learned that the city or rural fountain is a fixture of life. My wife comes from a rural area of Portugal and in her childhood town there still is a fountain where people go for their water needs. She remembers going to the fountain daily with her father. She recalls how the people would gather to visit, to talk, and to be with their neighbours. Today the townspeople still gather at the fountain. Like outdoor coffee shops, the town fountain serves as a heartbeat for the people.

In this chapter we are in the countryside. The area is “all worn out.” We read that “Monseigneur as a class, somehow or other, brought things to this.” The mender of roads worked, solitary, in the dust. He is starving. As he works breaking stones for the roads, I see a metaphor the state of France. It too is broken. The poor have no road to take to a better life. One day a man comes upon the road mender “like a ghost” and both men great each other as Jacques. As they settle in to talk the word “To-night” enters the conversation. As they talk we are told that they sat “on a heap of stones” while “hail [drove] in between them like a pigmy charge of bayonets, until the sky began to clear over the village.” Ah, hail, an unpleasant weather event, surrounds the men. What is going on here? Remember that Dickens frequently used pathetic fallacy to heighten the essence of warnings in his narratives.

The wayfarer is in need of sleep and so he prepares to rest. We are told he “slipped off his great wooden shoes.” The mention of wooden shoes emphasizes he is a very poor man. It also links back to the sound heard when hundreds, indeed thousands of pairs of wooden shoes ran through the streets of France and were imagined by Lucie in her quiet corner of London. The road mender looks at the sleeping man. Let’s look at what he sees. The wayfarer “had travelled far, and his feet were footsore, and his ankles chafed and bleeding; his great shoes, stuffed with leaves and grass, had been heavy to drag over the many long leagues and his clothes were chafed into holes, as he himself was into sores.” The road mender sees in his mind “similar figures, stopped by no obstacle, tending to centres all over France.”

Why does Dickens focus on the man’s shoes? If we look back to Browne’s illustration of the dead child who was run over by the Marquis’s carriage found in Book 2 Chapters 7-13 message 40 the role of wooden shoes is discussed. Here again, in this chapter, Dickens focusses on shoes. Dickens is a master of building and repeating symbols. In this chapter he first reintroduces the wooden shoe. This time, however, Dickens looks closely at the feet of the poor man. Closer and closer. What do we see? Poverty and pain. Our first look at Doctor Manette reveals him at a workbench working on a shoe. Over and over Dickens weaves the idea of shoes, footprints, and sounds of feet into the text.

The wayfarer leaves, the road-mender goes home to the village. After his meal the road mender and the rest of the town gather around the town fountain and look to the sky . Why?

Dickens then abruptly changes our point of view to the chateau of the former Marquis. First, it is dark. Then, the chateau seems to become visible “by some light of its own.” Monsieur Gabelle sees the fire but can find no one to help as “the mender of roads and two hundred and fifty particular friends, stood with folded arms at the fountain.” The chateau burned. It was totally destroyed. The fountain of the chateau “ran dry.” As we look towards the massive destruction of the chateau there are “four fierce figures” who trudged away “towards their next destination.” Clearly, there is a select group of men who travel about France destroying the property of the aristocracy.

The townspeople turn on Gabelle who they saw as a tax collector. For the time being his life appears to be spared. As our chapter ends we read that the horrors of the Revolution are spreading throughout France. It seems no one was exempt from the grind of death and destruction.

Chapter 24

Drawn to Loadstone Rock

“The peril of an old servant and a good one, whose only crime was fidelity to himself and his family, stared him so reproachfully in the face that, as he walked to and fro in the Temple considering what to do, he almost hid his face from the passers-by.”

Three years have passed since the last chapter. In their quiet corner of London Lucie and her family still live and still hear footsteps of a people “tumultuous under a red flag … changed into wild beasts.” We learn that the “Monseigneur, as a class,” the Court system, and Royalty were all gone. By 1792 all had changed in France. Meanwhile, in England, Tellson’s Bank remained its old self. The Monseigneurs who had escaped from France find themselves hanging about Tellson’s and fondly wishing for the old days and, no doubt, very happy that they still had their heads.

It is at Tellson’s one hot day we find Mr Lorry and Charles Darnay. Mr Lorry is planning to travel to Paris. He has no fear of the mob. He is old. Tellson’s is old. He is a man of business. He will gladly inconvenience himself for the sake of Tellson’s. His purpose is to save financial documents and records that pertain to Tellson’s French clients. Lorry believes that one way of saving the documents will be to bury them. In any case, he is leaving for Paris this very night. Jerry Cruncher will accompany him. Is their anything that isn’t buried in the novel?

Darnay thinks that perhaps he should also go to France. He believes he would be listened to and might even be able to persuade some people to restrain themselves. To me this makes little sense. Darnay has not been to France, with the exception of a quick visit to his uncle, in a very long time. Does he really think he is that important, that respected, that remembered? At this point, he has decided not to travel to France.

Well, wait just a moment. A letter is delivered to Mr Lorry addressed to the Marquis St Evremonde. This is our own Charles. This is the name Dr Manette learned on the day of Lucie’s wedding. This is the reason Doctor Manette regressed for nine days after Lucie’s wedding. This is the secret between Charles and the Doctor that was never to be shared unless the Doctor wished it. We learn that both the late Marquis and his unknown nephew are vilified by the Monseigneurs. Stryver puts in his two cents worth of hatred for the nephew as well. Darnay claims he knows how to find young Evermonde and will deliver the letter. In a way, here is another example of pairing. The English Darnay will go to France to find, or to become, the French Darnay/Evremonde.

Darnay seeks a private place and reads the letter. It is from Gabelle who announces he has been seized by the mob and will shortly be summoned before the tribunal. He will certainly be put to death. Gabelle recounts how he has been fair to the poor and had shown them compassion and sympathy. It matters not to the crowd. Gabelle says his only fault is that he has been loyal to Charles. Gabelle begs for Charles to help.

At this moment Charles realizes the horrid dilemma he faces and that he has acted “imperfectly.” He loves Lucie, he has renounced and hopefully buried his connection to his family, but yet he has kept secrets from his wife. Now, the secrets are surfacing, his past, his connection to the most hated family in France are arising from the past. His past that once was buried has now assumed life again. What was thought dead and buried has been recalled to life. Charles Darnay is a man of honour. He decides he must return to France and hopefully be able to recall Gabelle to life. Yes, “The Loadstone Rock was drawing him back.

Charles decides he will not tell Lucie or her father his plans. Rather, he will write them when he is in Paris.

Thoughts

I’ve always been uneasy about the way Charles Darnay is portrayed in the novel. What is your opinion of him?

Let’s take a look at how Dickens uses physical structures as emblems of an idea or even a society. In the novel Tellson’s bank is portrayed as a very ancient place. Its clerks are ancient, its accounts are old and well-established. Those who work there are old or kept in the back offices until they are old. Tellson’s foundation is its massive ledgers that record both the bank’s past and its patrons. Physically, the Tellson’s building is old as well. As one of its most senior employees Mr Lorry self-describes himself as a man of business.

Let's compare this to the Defarge’s wine shop. There are no massive and ancient ledgers in the wine shop. The record keeping is done with knitting needles and wool. The record of names in the knitting is guarded carefully. These records span many decades. Mme Defarge is the Jarvis Lorry of the wine shop. She is loyal, constant, and faithful to the wine shop just as Mr. Lorry is faithful to Tellson’s Bank. There is an ancient stability that is present in Tellson’s. There are ancient grudges found in the wine store. In Tellson’s we have a place that is build to be stable; in the wine shop we have a place built to centre a revolution.

We have seen these differences in the illustrations. To what extent do you find the illustrations enhance your reading experience and comprehension of the novel?

Drawn to Loadstone Rock

“The peril of an old servant and a good one, whose only crime was fidelity to himself and his family, stared him so reproachfully in the face that, as he walked to and fro in the Temple considering what to do, he almost hid his face from the passers-by.”

Three years have passed since the last chapter. In their quiet corner of London Lucie and her family still live and still hear footsteps of a people “tumultuous under a red flag … changed into wild beasts.” We learn that the “Monseigneur, as a class,” the Court system, and Royalty were all gone. By 1792 all had changed in France. Meanwhile, in England, Tellson’s Bank remained its old self. The Monseigneurs who had escaped from France find themselves hanging about Tellson’s and fondly wishing for the old days and, no doubt, very happy that they still had their heads.

It is at Tellson’s one hot day we find Mr Lorry and Charles Darnay. Mr Lorry is planning to travel to Paris. He has no fear of the mob. He is old. Tellson’s is old. He is a man of business. He will gladly inconvenience himself for the sake of Tellson’s. His purpose is to save financial documents and records that pertain to Tellson’s French clients. Lorry believes that one way of saving the documents will be to bury them. In any case, he is leaving for Paris this very night. Jerry Cruncher will accompany him. Is their anything that isn’t buried in the novel?

Darnay thinks that perhaps he should also go to France. He believes he would be listened to and might even be able to persuade some people to restrain themselves. To me this makes little sense. Darnay has not been to France, with the exception of a quick visit to his uncle, in a very long time. Does he really think he is that important, that respected, that remembered? At this point, he has decided not to travel to France.

Well, wait just a moment. A letter is delivered to Mr Lorry addressed to the Marquis St Evremonde. This is our own Charles. This is the name Dr Manette learned on the day of Lucie’s wedding. This is the reason Doctor Manette regressed for nine days after Lucie’s wedding. This is the secret between Charles and the Doctor that was never to be shared unless the Doctor wished it. We learn that both the late Marquis and his unknown nephew are vilified by the Monseigneurs. Stryver puts in his two cents worth of hatred for the nephew as well. Darnay claims he knows how to find young Evermonde and will deliver the letter. In a way, here is another example of pairing. The English Darnay will go to France to find, or to become, the French Darnay/Evremonde.

Darnay seeks a private place and reads the letter. It is from Gabelle who announces he has been seized by the mob and will shortly be summoned before the tribunal. He will certainly be put to death. Gabelle recounts how he has been fair to the poor and had shown them compassion and sympathy. It matters not to the crowd. Gabelle says his only fault is that he has been loyal to Charles. Gabelle begs for Charles to help.

At this moment Charles realizes the horrid dilemma he faces and that he has acted “imperfectly.” He loves Lucie, he has renounced and hopefully buried his connection to his family, but yet he has kept secrets from his wife. Now, the secrets are surfacing, his past, his connection to the most hated family in France are arising from the past. His past that once was buried has now assumed life again. What was thought dead and buried has been recalled to life. Charles Darnay is a man of honour. He decides he must return to France and hopefully be able to recall Gabelle to life. Yes, “The Loadstone Rock was drawing him back.

Charles decides he will not tell Lucie or her father his plans. Rather, he will write them when he is in Paris.

Thoughts

I’ve always been uneasy about the way Charles Darnay is portrayed in the novel. What is your opinion of him?

Let’s take a look at how Dickens uses physical structures as emblems of an idea or even a society. In the novel Tellson’s bank is portrayed as a very ancient place. Its clerks are ancient, its accounts are old and well-established. Those who work there are old or kept in the back offices until they are old. Tellson’s foundation is its massive ledgers that record both the bank’s past and its patrons. Physically, the Tellson’s building is old as well. As one of its most senior employees Mr Lorry self-describes himself as a man of business.

Let's compare this to the Defarge’s wine shop. There are no massive and ancient ledgers in the wine shop. The record keeping is done with knitting needles and wool. The record of names in the knitting is guarded carefully. These records span many decades. Mme Defarge is the Jarvis Lorry of the wine shop. She is loyal, constant, and faithful to the wine shop just as Mr. Lorry is faithful to Tellson’s Bank. There is an ancient stability that is present in Tellson’s. There are ancient grudges found in the wine store. In Tellson’s we have a place that is build to be stable; in the wine shop we have a place built to centre a revolution.

We have seen these differences in the illustrations. To what extent do you find the illustrations enhance your reading experience and comprehension of the novel?

Peter wrote: "The obvious question is what exactly triggered the relapse? Putting on your hat as a psychologist/psychiatrist how would you explain what specially triggered Dr Manette’s relapse?"

Peter wrote: "The obvious question is what exactly triggered the relapse? Putting on your hat as a psychologist/psychiatrist how would you explain what specially triggered Dr Manette’s relapse?"In an earlier chapter I was commenting on how ridiculous it was that Dr. M tells Charles Darnay not to reveal his real name to him, and the reason he's left France, until the morning he marries Lucie. At the time my thought was "well that will clearly be too late--what a clunky plot device to extend the tension."

Now I think differently. I think the Doctor knew it would be too late. He knew Lucie and Charles were right for each other and he didn't want to get in the way of their marriage, as he inevitably would have if it were clear it was a prospect that would upset him--through no fault of Charles's. Lucie's not going to enter a marriage that troubles her father. So Manette puts off knowing for sure what he already sees coming, until it will be too late to do anything about it. Charles delivers the news, everybody promptly heads off to the church and the waiting minister, the newlyweds head off for the honeymoon and Manette immediately has a breakdown carefully timed so as not to put a blight on the marriage.

I am also going to have to reverse myself on last installment's discussion with Mary Lou, in which I said maybe Lorry should be treating Lucie like an adult and telling her what's up with her father. I don't think that anymore. Manette was under excellent care and Lucie was on her honeymoon. She has given up enough to secure her father's welfare already--she deserves a few untroubled days off, and although I don't think Lorry knows this, Manette has timed things very well to give them to her.

Again, so many small sacrifices in this book!

The whole thing about Manette's split personality that Peter has pointed out--how he knows things and doesn't know them, and can compartmentalize so well--is fascinating to me, and I don't know what to make of it.

I also don't quite know what to make of this parallel. Here's the women of Saint Antoine:

I also don't quite know what to make of this parallel. Here's the women of Saint Antoine:All the women knitted. They knitted worthless things; but, the mechanical work was a mechanical substitute for eating and drinking; the hands moved for the jaws and the digestive apparatus: if the bony fingers had been still, the stomachs would have been more famine-pinched.

And here's Dr. Manette on his shoemaking:

“You see,” said Doctor Manette, turning to him after an uneasy pause, “it is very hard to explain, consistently, the innermost workings of this poor man’s mind. He once yearned so frightfully for that occupation, and it was so welcome when it came; no doubt it relieved his pain so much, by substituting the perplexity of the fingers for the perplexity of the brain, and by substituting, as he became more practised, the ingenuity of the hands, for the ingenuity of the mental torture; that he has never been able to bear the thought of putting it quite out of his reach. Even now, when I believe he is more hopeful of himself than he has ever been, and even speaks of himself with a kind of confidence, the idea that he might need that old employment, and not find it, gives him a sudden sense of terror, like that which one may fancy strikes to the heart of a lost child.”

Peter wrote: "Let's compare this to the Defarge’s wine shop. There are no massive and ancient ledgers in the wine shop. The record keeping is done with knitting needles and wool. The record of names in the knitting is guarded carefully. These records span many decades. Mme Defarge is the Jarvis Lorry of the wine shop. She is loyal, constant, and faithful to the wine shop just as Mr. Lorry is faithful to Tellson’s Bank. There is an ancient stability that is present in Tellson’s. There are ancient grudges found in the wine store. In Tellson’s we have a place that is build to be stable; in the wine shop we have a place built to centre a revolution. "

Peter wrote: "Let's compare this to the Defarge’s wine shop. There are no massive and ancient ledgers in the wine shop. The record keeping is done with knitting needles and wool. The record of names in the knitting is guarded carefully. These records span many decades. Mme Defarge is the Jarvis Lorry of the wine shop. She is loyal, constant, and faithful to the wine shop just as Mr. Lorry is faithful to Tellson’s Bank. There is an ancient stability that is present in Tellson’s. There are ancient grudges found in the wine store. In Tellson’s we have a place that is build to be stable; in the wine shop we have a place built to centre a revolution. "What a great parallel. In answer to the question of why bloodthirsty England gets off the hook in this book and France doesn't--I don't think England does get off. I think it becomes pretty clear as you read through the book that people are people, and it takes only a very slight turn to channel impulses that are very good into actions that are very bad.

Maybe not entirely, though. It is also clear that the Monseigneurs in the book are relentlessly negligent and persistently unaccountable in ways that don't have an English parallel. They never see their actions as contributing to the Revolution. The English and French mobs are both awful, but I'm not seeing any evil English nobles in the book to parallel the French. The English aristocracy is off the hook.

The closest we could get to this maybe is to look at Tellson's Bank as the enabler to the French aristocracy--which really it is! But it's hard to see Tellson's as a corruptive force when marvelous Lorry is its face to the world. Maybe the role of "just business" institutions in all this is a point we can take away from the picture that Dickens possibly did not intend to make. You all know I love Lorry, but I do see him and his bank as part of the problem here.

Peter wrote: "I’ve always been uneasy about the way Charles Darnay is portrayed in the novel. What is your opinion of him?"

Peter wrote: "I’ve always been uneasy about the way Charles Darnay is portrayed in the novel. What is your opinion of him?"He is a well-meaning but vain fool. I find it interesting to juxtapose the grand sacrifice Charles takes here of going back and rescuing Gabelle, when as Peter points out, there is really no reason for him to believe he can pull this off, to the smaller daily domestic sacrifices people make in these books (Carton with his rare undrunken visits is looking good at the moment, folks!)--or to Lorry's well-informed decision to go back to France for a very specific and accomplishable purpose that he alone can carry out.

Darnay means well, but he is also impractical and too fond of his own image. He takes what he sees as the heroic step in renouncing the birthright he should have tended to. And when he realizes this was a mistake, he does the same thing all over again by taking what he sees as the heroic step in returning to France when it's too late to tend to things. His timing is off and he doesn't have a practical bone in his body.

Plus at this point, the not-telling-Lucie is inexcusable.

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "The obvious question is what exactly triggered the relapse? Putting on your hat as a psychologist/psychiatrist how would you explain what specially triggered Dr Manette’s relapse?"

I..."

Hi Julie

Thanks for directing our attention to the number of sacrifices that occur in this novel. The more I think about it the more I see how densely packed TTC is with themes, motifs, and recurring symbols.

Like you I find the development of Dr. Manette a very accomplished bit of writing on Dickens’s part. We have certainly moved far from the over abundance of flat cardboard characters that populated the earlier novels.

.

I..."

Hi Julie

Thanks for directing our attention to the number of sacrifices that occur in this novel. The more I think about it the more I see how densely packed TTC is with themes, motifs, and recurring symbols.

Like you I find the development of Dr. Manette a very accomplished bit of writing on Dickens’s part. We have certainly moved far from the over abundance of flat cardboard characters that populated the earlier novels.

.

One of the first things I thought when I read about Doctor Manette was 'here is Lucie, who would be capable of becoming a very good second Little Dorrit, but her father won't let her.' Manette is quite the contrast as a father from William Dorrit, isn't he? Dorrit brings his whole family with him into jail, Manette makes sure they are sent away, even if that means he might never see them anymore. Where Dorrit wallows in self pity and idleness, Manette picks up a trade to occupy himself with the shoe making. And where Dorrit indulges and takes his daughter and her care for him for granted, Manette makes sure she gets as good a life as he can give her, even if that means he has to relive his old traumas in some way.

Jantine wrote: "One of the first things I thought when I read about Doctor Manette was 'here is Lucie, who would be capable of becoming a very good second Little Dorrit, but her father won't let her.' Manette is q..."

Hi Jantine

You are right. We have two very different father-daughter relationships in the past two novels. Thanks for pointing out the differences.

More and more as we move through the novels we find connections, comparisons, and contrasts in the novels of Dickens. I find this part of reading him very interesting.

Hi Jantine

You are right. We have two very different father-daughter relationships in the past two novels. Thanks for pointing out the differences.

More and more as we move through the novels we find connections, comparisons, and contrasts in the novels of Dickens. I find this part of reading him very interesting.

I'm just catching up with last week's installment and discussion. So much to think about, and so many good observations.

I'm just catching up with last week's installment and discussion. So much to think about, and so many good observations. Dr. Manette: I'm not as appreciative of the way this plays out as Peter and Julie seem to be. As was mentioned, surely Manette had an inkling of what Darnay had hoped to confide when he asked for Lucie's hand. But no relapse. Even when Darnay finally revealed his true identity on the morning of the wedding, the doctor still managed to hold it together until the happy couple had departed. In an example of amazing timing, he comes out of his stupor just before their return. If he has this much control, is he truly having a psychotic break? Is this PTSD based on the past, or some kind of anxiety about Lucie's future as Mrs. Darnay? Perhaps both. But I do think the way this played out is more about plot contrivance than realism.

I appreciated Jantine's comparison of Dr. Manette to William Dorrit! Lucie isn't annoying me as much as "the other Marys" - perhaps having a good father has made a difference.

Regarding Julie's assessment of Darnay, I had been thinking of him as rather noble (as nobility should be, I suppose), but now that you've pointed out his weaknesses, I can't unsee them, darn it. It was the same with Clennam in "Little Dorrit". Interesting to compare and contrast these two books.

Regarding Julie's assessment of Darnay, I had been thinking of him as rather noble (as nobility should be, I suppose), but now that you've pointed out his weaknesses, I can't unsee them, darn it. It was the same with Clennam in "Little Dorrit". Interesting to compare and contrast these two books. As for Lucie, I hold to the same opinion I had last week. It would be nice to think that by the end of our story she has a moment like this one that Elizabeth Taylor has in the wonderful movie, Giant:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EUm2M...

But she won't.

Twice now, we've been subjected to conversations with Dr. Manette which are presented as being about a third party: when he and Lucie talk about his dreams of his child when he was imprisoned, and now with Lorry, pretending he has a "friend" who has suffered a mental breakdown. I find this unnecessarily muddled in the first instance, and condescending to the doctor - a medical man! - in the second. Any thoughts as to why Dickens would make this choice? Twice? Did you enjoy these conversations, or did you, too, find the third party presentation overly sensitive? Peter, do you consider this another example of the reflective theme?

Twice now, we've been subjected to conversations with Dr. Manette which are presented as being about a third party: when he and Lucie talk about his dreams of his child when he was imprisoned, and now with Lorry, pretending he has a "friend" who has suffered a mental breakdown. I find this unnecessarily muddled in the first instance, and condescending to the doctor - a medical man! - in the second. Any thoughts as to why Dickens would make this choice? Twice? Did you enjoy these conversations, or did you, too, find the third party presentation overly sensitive? Peter, do you consider this another example of the reflective theme?

Peter wrote: "I think it important that we look carefully at the ending of this chapter. Mr Lorry and Miss Pross...

Peter wrote: "I think it important that we look carefully at the ending of this chapter. Mr Lorry and Miss Pross...Well, it wasn't exactly subtle, was it? One of the things it showed me was that Lorry and Pross both have it in them to be somewhat brutal, though I'm not sure such ferocity was called for when destroying the cobbler's bench. Will they need to harness their violent tendencies again at some point?

Julie wrote: "Now I think differently. I think the Doctor knew it would be too late. He knew Lucie and Charles were right for each other and he didn't want to get in the way of their marriage, as he inevitably would have if it were clear it was a prospect that would upset him--through no fault of Charles's. Lucie's not going to enter a marriage that troubles her father. So Manette puts off knowing for sure what he already sees coming, until it will be too late to do anything about it. "

This is a very interesting thought, Julie, and it chimes in well with the Fate motif that pervades the book, don't you think? There is the sound of the footsteps telling of things that are to come and people that are to rise, there is Mme Defarge knitting the thread of some people's fate and saying to her husband that whenever Charles Darnay comes to France and falls into the hands of the revolution, he has to take whatever consequences there may arise no matter whether he is Lucie's husband or no, and there are the fates of individual people woven into the fabric of history and events larger than themselves. Sometimes people can resign themselves voluntarily to these events and developments, sometimes they are just made to resign themselves.

This is a very interesting thought, Julie, and it chimes in well with the Fate motif that pervades the book, don't you think? There is the sound of the footsteps telling of things that are to come and people that are to rise, there is Mme Defarge knitting the thread of some people's fate and saying to her husband that whenever Charles Darnay comes to France and falls into the hands of the revolution, he has to take whatever consequences there may arise no matter whether he is Lucie's husband or no, and there are the fates of individual people woven into the fabric of history and events larger than themselves. Sometimes people can resign themselves voluntarily to these events and developments, sometimes they are just made to resign themselves.

Julie wrote: "I also don't quite know what to make of this parallel. Here's the women of Saint Antoine:

All the women knitted. They knitted worthless things; but, the mechanical work was a mechanical substitute ..."

Thinking of how people engage into activities in order to escape from their hunger, their sorrow and despair or from other thoughts and longings haunting them - may not Mr. Lorry's unbending devotion to his bank result from the fact that there is no one waiting at home for him?

All the women knitted. They knitted worthless things; but, the mechanical work was a mechanical substitute ..."

Thinking of how people engage into activities in order to escape from their hunger, their sorrow and despair or from other thoughts and longings haunting them - may not Mr. Lorry's unbending devotion to his bank result from the fact that there is no one waiting at home for him?

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "Let's compare this to the Defarge’s wine shop. There are no massive and ancient ledgers in the wine shop. The record keeping is done with knitting needles and wool. The record of name..."

Part of the explanation may lie in the fact that English and French nobilities were slightly different. In England, the title was passed on to the eldest son whereas his younger siblings had to earn their own money and make their own ways in life. Partly, this was done by investing in trade and industry, and any sort of business activity, provided it was not too menial, was not regarded as something to be ashamed of. French noblemen were more secluded as a class, and there was hardly any intermarriage between noble people and the higher bourgeoisie, and neither was there any productivity on the part of noble families. They simply led parasitic lives of consumption and showiness.

As a consequence, there was more resentment and discontent in the higher bourgeoisie in France than in England, which was one of the reasons for the outbreak of the French Revolution. In England, the higher bourgeoisie gained access to political power slowly, by reforms often, whereas in France, it all come in a kind of thunderstorm. I was quite astonished to find Dickens solely concentrate on the Sansculottes as the driving force of revolution, whereas in reality, the political revolution was started by the higher classes. Likewise, he also describes the Grande Peur, i.e. the burning of châteaux in the countryside as some kind of conspiracy, with mysterious men moving around in the country and doing the actual job. As far as I know, these outbreaks happened in a climate of mass hysteria, though. Dickens's main source on the Revolution seemed to be Burke and Carlyle, sources I have never read.

Part of the explanation may lie in the fact that English and French nobilities were slightly different. In England, the title was passed on to the eldest son whereas his younger siblings had to earn their own money and make their own ways in life. Partly, this was done by investing in trade and industry, and any sort of business activity, provided it was not too menial, was not regarded as something to be ashamed of. French noblemen were more secluded as a class, and there was hardly any intermarriage between noble people and the higher bourgeoisie, and neither was there any productivity on the part of noble families. They simply led parasitic lives of consumption and showiness.

As a consequence, there was more resentment and discontent in the higher bourgeoisie in France than in England, which was one of the reasons for the outbreak of the French Revolution. In England, the higher bourgeoisie gained access to political power slowly, by reforms often, whereas in France, it all come in a kind of thunderstorm. I was quite astonished to find Dickens solely concentrate on the Sansculottes as the driving force of revolution, whereas in reality, the political revolution was started by the higher classes. Likewise, he also describes the Grande Peur, i.e. the burning of châteaux in the countryside as some kind of conspiracy, with mysterious men moving around in the country and doing the actual job. As far as I know, these outbreaks happened in a climate of mass hysteria, though. Dickens's main source on the Revolution seemed to be Burke and Carlyle, sources I have never read.

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "I’ve always been uneasy about the way Charles Darnay is portrayed in the novel. What is your opinion of him?"

He is a well-meaning but vain fool. I find it interesting to juxtapose t..."

I completely agree with you, Julie. He ought to have told his wife and his father-in-law instead of simply absconding. And then, I think he should not have gone in the first place, all the more so as there is a snowball's chance in hell for his mission to be successfully accomplished. Even if there were a chance, I daresay he owes his primary allegiance to his family, especially his child. He is obliged not to endanger his life for a lofty cause and to stay in England and provide for his family who depends on him. I think Darnays behaviour very egocentric and clearly spurred by the disdain his real name evokes in his fellow-noblemen and in that blundering ass Stryver.

He is a well-meaning but vain fool. I find it interesting to juxtapose t..."

I completely agree with you, Julie. He ought to have told his wife and his father-in-law instead of simply absconding. And then, I think he should not have gone in the first place, all the more so as there is a snowball's chance in hell for his mission to be successfully accomplished. Even if there were a chance, I daresay he owes his primary allegiance to his family, especially his child. He is obliged not to endanger his life for a lofty cause and to stay in England and provide for his family who depends on him. I think Darnays behaviour very egocentric and clearly spurred by the disdain his real name evokes in his fellow-noblemen and in that blundering ass Stryver.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "I think it important that we look carefully at the ending of this chapter. Mr Lorry and Miss Pross...

Well, it wasn't exactly subtle, was it? One of the things it showed me was that ..."

It's just another instance of people destroying something and thinking they are doing a good job, liberating somebody - in a book on the French Revolution, this is quite a telling detail.

Well, it wasn't exactly subtle, was it? One of the things it showed me was that ..."

It's just another instance of people destroying something and thinking they are doing a good job, liberating somebody - in a book on the French Revolution, this is quite a telling detail.

Tristram wrote: "Julie wrote: "I also don't quite know what to make of this parallel. Here's the women of Saint Antoine:

All the women knitted. They knitted worthless things; but, the mechanical work was a mechanic..."

Tristram

Yes, I also think that many people engage deeply in one aspect of life in order to fill a void somewhere else in their life. That said, many of us read a great deal, or even too much, but can anyone read too much? We are all well-balanced … right? :-)

All the women knitted. They knitted worthless things; but, the mechanical work was a mechanic..."

Tristram

Yes, I also think that many people engage deeply in one aspect of life in order to fill a void somewhere else in their life. That said, many of us read a great deal, or even too much, but can anyone read too much? We are all well-balanced … right? :-)

I am certainly not well-balanced, Peter :-)

I read a lot, although certainly not too much, which is not possible; and my wife sometimes says I also identify too much with my work. I also have to check electric gadgets way too often before I leave my house.

That doesn't sound quite balanced, unluckily.

I read a lot, although certainly not too much, which is not possible; and my wife sometimes says I also identify too much with my work. I also have to check electric gadgets way too often before I leave my house.

That doesn't sound quite balanced, unluckily.

Tristram wrote: "Thinking of how people engage into activities in order to escape from their hunger, their sorrow and despair or from other thoughts and longings haunting them - may not Mr. Lorry's unbending devotion to his bank result from the fact that there is no one waiting at home for him?"

Tristram wrote: "Thinking of how people engage into activities in order to escape from their hunger, their sorrow and despair or from other thoughts and longings haunting them - may not Mr. Lorry's unbending devotion to his bank result from the fact that there is no one waiting at home for him?"That's very sad and would also explain why he's willing to take some time off once he finally has someone to care for. Tellson's is pretty much his family until then. Then again, Tellson's is not entirely undeserving, if not actually familial. The bank offers him stability and real appreciation of his talents.

Tristram wrote: "Dickens's main source on the Revolution seemed to be Burke and Carlyle, sources I have never read."

Tristram wrote: "Dickens's main source on the Revolution seemed to be Burke and Carlyle, sources I have never read."That's helpful to know about the different positions of nobility in France and England at the time.

Regarding Dickens's sources, a million years ago I did a lot of grad school work on 19th novels and histories, including reading all of Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France and Carlyle’s French Revolution. I don't see much of Burke here beyond the anti-revolutionary attitude (which is admittedly significant), but it really is striking how much Dickens borrowed from Carlyle not just in content but in style and imagery. Remember he admired him so much he dedicated Hard Times to him. Other period historians, Thomas Macaulay for instance, did not write in the sort of head-over-heels dashes and exclamation point rush that you see in both Carlyle and Dickens. Here’s an example of the influence, for anyone who’s curious:

This is Carlyle:

Nevertheless, as is natural, the waves still run high, hollow rocks retaining their murmur. We are but at the 22nd of the month, hardly above a week since the Bastille fell, when it suddenly appears that old Foulon is alive; nay, that he is here, in early morning, in the streets of Paris; the extortioner, the plotter, who would make the people eat grass, and was a liar from the beginning!—It is even so. The deceptive “sumptuous funeral” (of some domestic that died); the hiding-place at Vitry towards Fontainbleau, have not availed that wretched old man. Some living domestic or dependant, for none loves Foulon, has betrayed him to the Village. Merciless boors of Vitry unearth him; pounce on him, like hell-hounds: Westward, old Infamy; to Paris, to be judged at the Hôtel-de-Ville! His old head, which seventy-four years have bleached, is bare; they have tied an emblematic bundle of grass on his back; a garland of nettles and thistles is round his neck: in this manner; led with ropes; goaded on with curses and menaces, must he, with his old limbs, sprawl forward; the pitiablest, most unpitied of all old men.

Sooty Saint-Antoine, and every street, mustering its crowds as he passes,—the Place de Grève, the Hall of the Hôtel-de-Ville will scarcely hold his escort and him. Foulon must not only be judged righteously; but judged there where he stands, without any delay. Appoint seven judges, ye Municipals, or seventy-and-seven; name them yourselves, or we will name them: but judge him! Electoral rhetoric, eloquence of Mayor Bailly, is wasted explaining the beauty of the Law’s delay. Delay, and still delay! Behold, O Mayor of the People, the morning has worn itself into noon; and he is still unjudged!—Lafayette, pressingly sent for, arrives; gives voice: This Foulon, a known man, is guilty almost beyond doubt; but may he not have accomplices? Ought not the truth to be cunningly pumped out of him,—in the Abbaye Prison? It is a new light! Sansculottism claps hands;—at which hand-clapping, Foulon (in his fainness, as his Destiny would have it) also claps. ‘See! they understand one another!’ cries dark Sansculottism, blazing into fury of suspicion.—‘Friends,’ said “a person in good clothes,” stepping forward, ‘what is the use of judging this man? Has he not been judged these thirty years?’ With wild yells, Sansculottism clutches him, in its hundred hands: he is whirled across the Place de Grève, to the “Lanterne,” Lamp-iron which there is at the corner of the Rue de la Vannerie; pleading bitterly for life,—to the deaf winds. Only with the third rope (for two ropes broke, and the quavering voice still pleaded), can he be so much as got hanged! His Body is dragged through the streets; his Head goes aloft on a pike, the mouth filled with grass: amid sounds as of Tophet, from a grass-eating people.

And here’s Dickens with part of the same scene:

The men were terrible, in the bloody-minded anger with which they looked from windows, caught up what arms they had, and came pouring down into the streets; but, the women were a sight to chill the boldest. From such household occupations as their bare poverty yielded, from their children, from their aged and their sick crouching on the bare ground famished and naked, they ran out with streaming hair, urging one another, and themselves, to madness with the wildest cries and actions. Villain Foulon taken, my sister! Old Foulon taken, my mother! Miscreant Foulon taken, my daughter! Then, a score of others ran into the midst of these, beating their breasts, tearing their hair, and screaming, Foulon alive! Foulon who told the starving people they might eat grass! Foulon who told my old father that he might eat grass, when I had no bread to give him! Foulon who told my baby it might suck grass, when these breasts were dry with want! O mother of God, this Foulon! O Heaven our suffering! Hear me, my dead baby and my withered father: I swear on my knees, on these stones, to avenge you on Foulon! Husbands, and brothers, and young men, Give us the blood of Foulon, Give us the head of Foulon, Give us the heart of Foulon, Give us the body and soul of Foulon, Rend Foulon to pieces, and dig him into the ground, that grass may grow from him! With these cries, numbers of the women, lashed into blind frenzy, whirled about, striking and tearing at their own friends until they dropped into a passionate swoon, and were only saved by the men belonging to them from being trampled under foot.

Nevertheless, not a moment was lost; not a moment! This Foulon was at the Hotel de Ville, and might be loosed. Never, if Saint Antoine knew his own sufferings, insults, and wrongs! Armed men and women flocked out of the Quarter so fast, and drew even these last dregs after them with such a force of suction, that within a quarter of an hour there was not a human creature in Saint Antoine’s bosom but a few old crones and the wailing children.

No. They were all by that time choking the Hall of Examination where this old man, ugly and wicked, was, and overflowing into the adjacent open space and streets. The Defarges, husband and wife, The Vengeance, and Jacques Three, were in the first press, and at no great distance from him in the Hall.

“See!” cried madame, pointing with her knife. “See the old villain bound with ropes. That was well done to tie a bunch of grass upon his back. Ha, ha! That was well done. Let him eat it now!” Madame put her knife under her arm, and clapped her hands as at a play.

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Dickens's main source on the Revolution seemed to be Burke and Carlyle, sources I have never read."

That's helpful to know about the different positions of nobility in France and ..."

Julie

Thank you for this informative and insightful posting. This novel is becoming much more interesting as we take a look at the history and the writers of the history that surround it.

That's helpful to know about the different positions of nobility in France and ..."

Julie

Thank you for this informative and insightful posting. This novel is becoming much more interesting as we take a look at the history and the writers of the history that surround it.

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Dickens's main source on the Revolution seemed to be Burke and Carlyle, sources I have never read."

That's helpful to know about the different positions of nobility in France and ..."

That little extract from Carlyle was already enough to make me buy his book on the French Revolution. Thanks, Julie, it sounds very like a gripping read. I also have Burke's book on the Revolution at home, and have read some odd passages. I generally like Burke quite a lot, and will one day intensify my knowledge on his revolutionary book. But Carlyle will be read first, for sure.

That's helpful to know about the different positions of nobility in France and ..."

That little extract from Carlyle was already enough to make me buy his book on the French Revolution. Thanks, Julie, it sounds very like a gripping read. I also have Burke's book on the Revolution at home, and have read some odd passages. I generally like Burke quite a lot, and will one day intensify my knowledge on his revolutionary book. But Carlyle will be read first, for sure.

Tristram wrote: "Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Dickens's main source on the Revolution seemed to be Burke and Carlyle, sources I have never read."

Tristram wrote: "Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Dickens's main source on the Revolution seemed to be Burke and Carlyle, sources I have never read."That's helpful to know about the different positions of nobility ..."

I hope you like it. I have very mixed feelings about Carlyle but I do enjoy his writing style.

Tristram wrote: "I am certainly not well-balanced, Peter :-)

Well look at that, once again we agree on something.

Well look at that, once again we agree on something.

The Accomplices

Book II Chapter 19

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"I would not keep it," said Mr. Lorry, shaking his head; for he gained in firmness as he saw the Doctor disquieted. "I would recommend him to sacrifice it. I only want your authority. I am sure it does no good. Come! Give me your authority, like a dear good man. For his daughter's sake, my dear Manette!"

Very strange to see what a struggle there was within him!

"In her name, then, let it be done; I sanction it. But, I would not take it away while he was present. Let it be removed when he is not there; let him miss his old companion after an absence."

Mr. Lorry readily engaged for that, and the conference was ended. They passed the day in the country, and the Doctor was quite restored. On the three following days he remained perfectly well, and on the fourteenth day he went away to join Lucie and her husband. The precaution that had been taken to account for his silence, Mr. Lorry had previously explained to him, and he had written to Lucie in accordance with it, and she had no suspicions.

On the night of the day on which he left the house, Mr. Lorry went into his room with a chopper, saw, chisel, and hammer, attended by Miss Pross carrying a light. There, with closed doors, and in a mysterious and guilty manner, Mr. Lorry hacked the shoemaker's bench to pieces, while Miss Pross held the candle as if she were assisting at a murder—for which, indeed, in her grimness, she was no unsuitable figure. The burning of the body (previously reduced to pieces convenient for the purpose) was commenced without delay in the kitchen fire; and the tools, shoes, and leather, were buried in the garden. So wicked do destruction and secrecy appear to honest minds, that Mr. Lorry and Miss Pross, while engaged in the commission of their deed and in the removal of its traces, almost felt, and almost looked, like accomplices in a horrible crime."

The Sea Rises

Book II Chapter 22

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"A moment of profound silence followed. Defarge and his wife looked steadfastly at one another. The Vengeance stooped, and the jar of a drum was heard as she moved it at her feet behind the counter.

"Patriots!" said Defarge, in a determined voice, "are we ready?"

Instantly Madame Defarge's knife was in her girdle; the drum was beating in the streets, as if it and a drummer had flown together by magic; and The Vengeance, uttering terrific shrieks, and flinging her arms about her head like all the forty Furies at once, was tearing from house to house, rousing the women.

The men were terrible, in the bloody-minded anger with which they looked from windows, caught up what arms they had, and came pouring down into the streets; but, the women were a sight to chill the boldest. From such household occupations as their bare poverty yielded, from their children, from their aged and their sick crouching on the bare ground famished and naked, they ran out with streaming hair, urging one another, and themselves, to madness with the wildest cries and actions. Villain Foulon taken, my sister! Old Foulon taken, my mother! Miscreant Foulon taken, my daughter! Then, a score of others ran into the midst of these, beating their breasts, tearing their hair, and screaming, Foulon alive! Foulon who told the starving people they might eat grass! Foulon who told my old father that he might eat grass, when I had no bread to give him! Foulon who told my baby it might suck grass, when these breasts were dry with want! O mother of God, this Foulon! O Heaven our suffering! Hear me, my dead baby and my withered father: I swear on my knees, on these stones, to avenge you on Foulon! Husbands, and brothers, and young men, Give us the blood of Foulon, Give us the head of Foulon, Give us the heart of Foulon, Give us the body and soul of Foulon, Rend Foulon to pieces, and dig him into the ground, that grass may grow from him! With these cries, numbers of the women, lashed into blind frenzy, whirled about, striking and tearing at their own friends until they dropped into a passionate swoon, and were only saved by the men belonging to them from being trampled under foot.

Nevertheless, not a moment was lost; not a moment! This Foulon was at the Hotel de Ville, and might be loosed. Never, if Saint Antoine knew his own sufferings, insults, and wrongs! Armed men and women flocked out of the Quarter so fast, and drew even these last dregs after them with such a force of suction, that within a quarter of an hour there was not a human creature in Saint Antoine's bosom but a few old crones and the wailing children."

Commentary: