The Old Curiosity Club discussion

A Tale of Two Cities

>

Book Three Chp 8-12

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 9

The Game Made

“I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: and whosoever liveth and believeth in me, shall never die.”

This is a chapter of revelation. Before we get to Sydney’s plan, let's briefly look at the conversation between Mr Lorry and Jerry. Mr Lorry now has confirmation that Jerry is a resurrection man. Lorry is horrified at the thought and worries how this might reflect badly on Tellson’s Bank. Jerry tries to convince Mr Lorry that such an occupation has dignity, honour, and is, in fact, needed. Jerry wants his son to work at Tellson’s and promises that he himself will go “into the line of reg’lar diggin’, and make amends for what he would have un-dug.” To me, Jerry’s defence of his other job to Mr Lorry’s has a humourous tone. (dare I call it gallows humour?)

Carton and Barsad complete their secret meeting. Subsequently, as Mr Lorry speaks with Carton, he begins to see beneath the image of Carton that is projected to the public. Slowly but surely, Lorry begins to see the depth of Sydney’s soul, the honour of his bearing, and ultimately the sacrifice he is willing to undertake for the person he vowed he would do anything for in life. Dickens goes on to describe more fully how Mr Lorry finally takes the time to look closely at Sydney, his face, and the expressions on that face. Carton and Lorry engage in a philosophical dialogue about how to value a person in life. Sydney comments that he has a solitary heart and says he sees himself as a man who has done “nothing good or serviceable to be remembered by!”

I find this conversation between Darnay and Mr Lorry fascinating. It is very different from what we have encountered between them elsewhere in the novel. Their conversation touches deep. In fact, I can recall no other instance of a similar conversation between characters in Dickens. Can you recall another conversation of such intimate depth in Dickens?

Carton goes to a chemist where he purchases items that lead to a warning from the chemist “you know the consequences of mixing them?” Caron responds “perfectly.” Whatever is going on, whatever Carton’s plans are, he is deliberate, methodical, and clearly focussed. For the remainder of the night Sydney wanders the streets of Paris. The words “I am the resurrection and the life … “ follow Sydney through the darkened streets of Paris.

The next morning Sydney goes to the courtroom to attend the trial of Charles Darnay. Here is a subtle parallel. The first trial of Charles Darnay was held in England. Charles was accused of being a spy for the French. Sydney Carton was his lawyer and it was Sydney Carton who, because of his physical likeness to Darnay, secured the release of Charles. Now, we are in France. Charles Darnay is on trial yet again, this time for being an aristocrat. Sydney Carton is attending this trial as well. How can Sydney, for a second time, save Charles Darnay, how can Sydney recall Charles Darnay to life once again?

To the surprise of no one, we learn that Charles Darnay is accused by the Defarge’s; to the shock of everyone the third accuser is Doctor Manette. How can this be? Defarge takes the stand and recounts the day the Bastille fell, and how he went to 105 North Tower which was where Doctor Manette had been held captive for years. There, in a hole in the chimney, Defarge found a hidden piece of paper. The paper is handed to the court to be read. And so ends the chapter.

Thoughts

The plot is moving quickly. Are you enjoying the weekly format of chapters?

The Game Made

“I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: and whosoever liveth and believeth in me, shall never die.”

This is a chapter of revelation. Before we get to Sydney’s plan, let's briefly look at the conversation between Mr Lorry and Jerry. Mr Lorry now has confirmation that Jerry is a resurrection man. Lorry is horrified at the thought and worries how this might reflect badly on Tellson’s Bank. Jerry tries to convince Mr Lorry that such an occupation has dignity, honour, and is, in fact, needed. Jerry wants his son to work at Tellson’s and promises that he himself will go “into the line of reg’lar diggin’, and make amends for what he would have un-dug.” To me, Jerry’s defence of his other job to Mr Lorry’s has a humourous tone. (dare I call it gallows humour?)

Carton and Barsad complete their secret meeting. Subsequently, as Mr Lorry speaks with Carton, he begins to see beneath the image of Carton that is projected to the public. Slowly but surely, Lorry begins to see the depth of Sydney’s soul, the honour of his bearing, and ultimately the sacrifice he is willing to undertake for the person he vowed he would do anything for in life. Dickens goes on to describe more fully how Mr Lorry finally takes the time to look closely at Sydney, his face, and the expressions on that face. Carton and Lorry engage in a philosophical dialogue about how to value a person in life. Sydney comments that he has a solitary heart and says he sees himself as a man who has done “nothing good or serviceable to be remembered by!”

I find this conversation between Darnay and Mr Lorry fascinating. It is very different from what we have encountered between them elsewhere in the novel. Their conversation touches deep. In fact, I can recall no other instance of a similar conversation between characters in Dickens. Can you recall another conversation of such intimate depth in Dickens?

Carton goes to a chemist where he purchases items that lead to a warning from the chemist “you know the consequences of mixing them?” Caron responds “perfectly.” Whatever is going on, whatever Carton’s plans are, he is deliberate, methodical, and clearly focussed. For the remainder of the night Sydney wanders the streets of Paris. The words “I am the resurrection and the life … “ follow Sydney through the darkened streets of Paris.

The next morning Sydney goes to the courtroom to attend the trial of Charles Darnay. Here is a subtle parallel. The first trial of Charles Darnay was held in England. Charles was accused of being a spy for the French. Sydney Carton was his lawyer and it was Sydney Carton who, because of his physical likeness to Darnay, secured the release of Charles. Now, we are in France. Charles Darnay is on trial yet again, this time for being an aristocrat. Sydney Carton is attending this trial as well. How can Sydney, for a second time, save Charles Darnay, how can Sydney recall Charles Darnay to life once again?

To the surprise of no one, we learn that Charles Darnay is accused by the Defarge’s; to the shock of everyone the third accuser is Doctor Manette. How can this be? Defarge takes the stand and recounts the day the Bastille fell, and how he went to 105 North Tower which was where Doctor Manette had been held captive for years. There, in a hole in the chimney, Defarge found a hidden piece of paper. The paper is handed to the court to be read. And so ends the chapter.

Thoughts

The plot is moving quickly. Are you enjoying the weekly format of chapters?

Chapter 10

The Substance of the Shadow

“ … in my unbearable agony, [I] denounce to the times when all these things shall be answered for. I denounce them to Heaven and to earth.”

In this chapter we have the climax of the novel. The letter found by Defarge in 105 North Tower is read in court. In it we learn why Doctor Manette was incarcerated, who were responsible for putting him in jail, and what the letter will mean for the families of both Manette and Darnay. I think a bit of history is necessary here. In 1793 the Law of Suspects came into effect. This law stated that within a family and their relatives people who had “not constantly demonstrated their devotion to the Revolution” could be put to death. If we trace the meaning of this law into our story that means most of our central characters are doomed.

I will recount all the major plot insights and revelations. Hopefully, by the end of the chapter, we will have all the major questions of the novel up to this point answered.

Let’s look at the chronology of events prior to the French Revolution. Doctor Manette’s letter was written in December of 1767. In December of 1757 Doctor Manette was approached by two cloaked and armed men who demanded Manette enter their carriage. These men took Manette to an isolated home. They strike the man who answers the door. Manette notices that the two men look alike. He assumes they are twin brothers. Upstairs a beautiful but dishevelled young woman of about 20 is found with her hands bound to her sides. Doctor Manette notices that there is the letter “E” in one of the bindings on her arms. The young woman repeatedly shrieks “my husband, my father, my brother” and then counts up to twelve. We learn that the men are not related to the young lady. Manette administers some medicine that is found in the house.

Manette is then told there is yet another patient in need of attendance. Manette is shown a young peasant-boy about seventeen years old. He is suffering from a sword wound and Manette knows he will die. Manette learns that the boy was wounded by the younger brother of the twins. We learn that the young lad is the brother of the woman who is bound. The young man explains the horrible treatment and liberties the Nobles force upon the peasants. Through the words of the young lad Dickens is able to tell his readers some of the reasons for the French Revolution. We learn that the young man’s sister was married and the Nobles took it upon themselves to kill the poor husband through maltreatment and neglect. The young girl’s brother then recounts how he took his other sister to a place safe from the Nobles and returned to face his sister’s captors. For his efforts he was run through with a sword. Just before the lad dies he makes a cross with his blood and curses the Nobles to their death. The doctor then turns his attention to the young girl again and realizes she is pregnant. The more dominant of the brothers then warns Manette that what he has seen he will never speak of again.

The girl dies. Dr Manette recounts in his letter that he decided to write to the Minister and recount what had happened as he wished to relieve his mind. Before the letter is sent Dr Manette recounts that a lady came to see him. She was the wife of the Marquis St Evremonde. This woman had pieced the events her husband was involved in with the young girl together and had reason to believe that the young sister of the dead woman was living. She wished to help the young sister. She wishes to do this as she herself has a young son. She wishes that the first charge of her son’s young life is to bestow compassion on the sister of the injured family if she can be discovered. The name of her son was Charles.

On the last night of the year a man dressed in black came to the Doctor's house. He followed Dr Manette’s young servant Ernest Defarge to the room where Dr Manette and his wife were. Evidently there was a case needing the Doctor's attention. It was a trick. Once in the carriage Manette was seized, the two brothers appear, show Manette the letter he had written to the Minister. The letter is burnt before his eyes and Manette is taken to jail where he has been for years. And now, the fate of Charles Darnay is sealed. The jury vote. Darnay is to be put to death.

Thoughts

Well, that’s quite the backstory, but it does explain much and clear up some loose ends.To what extent does this chapter clarify the backstory to your satisfaction?

Doctor Manette’s own words were “them and their dependents to the last of their race.” Who exactly would be included in this broad statement?

The Substance of the Shadow

“ … in my unbearable agony, [I] denounce to the times when all these things shall be answered for. I denounce them to Heaven and to earth.”

In this chapter we have the climax of the novel. The letter found by Defarge in 105 North Tower is read in court. In it we learn why Doctor Manette was incarcerated, who were responsible for putting him in jail, and what the letter will mean for the families of both Manette and Darnay. I think a bit of history is necessary here. In 1793 the Law of Suspects came into effect. This law stated that within a family and their relatives people who had “not constantly demonstrated their devotion to the Revolution” could be put to death. If we trace the meaning of this law into our story that means most of our central characters are doomed.

I will recount all the major plot insights and revelations. Hopefully, by the end of the chapter, we will have all the major questions of the novel up to this point answered.

Let’s look at the chronology of events prior to the French Revolution. Doctor Manette’s letter was written in December of 1767. In December of 1757 Doctor Manette was approached by two cloaked and armed men who demanded Manette enter their carriage. These men took Manette to an isolated home. They strike the man who answers the door. Manette notices that the two men look alike. He assumes they are twin brothers. Upstairs a beautiful but dishevelled young woman of about 20 is found with her hands bound to her sides. Doctor Manette notices that there is the letter “E” in one of the bindings on her arms. The young woman repeatedly shrieks “my husband, my father, my brother” and then counts up to twelve. We learn that the men are not related to the young lady. Manette administers some medicine that is found in the house.

Manette is then told there is yet another patient in need of attendance. Manette is shown a young peasant-boy about seventeen years old. He is suffering from a sword wound and Manette knows he will die. Manette learns that the boy was wounded by the younger brother of the twins. We learn that the young lad is the brother of the woman who is bound. The young man explains the horrible treatment and liberties the Nobles force upon the peasants. Through the words of the young lad Dickens is able to tell his readers some of the reasons for the French Revolution. We learn that the young man’s sister was married and the Nobles took it upon themselves to kill the poor husband through maltreatment and neglect. The young girl’s brother then recounts how he took his other sister to a place safe from the Nobles and returned to face his sister’s captors. For his efforts he was run through with a sword. Just before the lad dies he makes a cross with his blood and curses the Nobles to their death. The doctor then turns his attention to the young girl again and realizes she is pregnant. The more dominant of the brothers then warns Manette that what he has seen he will never speak of again.

The girl dies. Dr Manette recounts in his letter that he decided to write to the Minister and recount what had happened as he wished to relieve his mind. Before the letter is sent Dr Manette recounts that a lady came to see him. She was the wife of the Marquis St Evremonde. This woman had pieced the events her husband was involved in with the young girl together and had reason to believe that the young sister of the dead woman was living. She wished to help the young sister. She wishes to do this as she herself has a young son. She wishes that the first charge of her son’s young life is to bestow compassion on the sister of the injured family if she can be discovered. The name of her son was Charles.

On the last night of the year a man dressed in black came to the Doctor's house. He followed Dr Manette’s young servant Ernest Defarge to the room where Dr Manette and his wife were. Evidently there was a case needing the Doctor's attention. It was a trick. Once in the carriage Manette was seized, the two brothers appear, show Manette the letter he had written to the Minister. The letter is burnt before his eyes and Manette is taken to jail where he has been for years. And now, the fate of Charles Darnay is sealed. The jury vote. Darnay is to be put to death.

Thoughts

Well, that’s quite the backstory, but it does explain much and clear up some loose ends.To what extent does this chapter clarify the backstory to your satisfaction?

Doctor Manette’s own words were “them and their dependents to the last of their race.” Who exactly would be included in this broad statement?

Chapter 11

Dusk

“Yes he will perish: there is no real hope,” echoed Carton. And walked with a settled step, down-stairs.

Charles Darnay has been found guilty and will die within 24 hours. With the sentence passed, the spectators in the court pile out into the streets to join in a public demonstration to celebrate. While Darnay was found innocent in the English court, I’m sure the flies that awaited the English verdict would have equally celebrated a death sentence. Darnay is able to speak these words to Lucie: “My parting blessing on my love. We shall meet again where the weary are at rest.” Lucie tells Charles that her heart will break and she will soon follow him. She assures Charles that there will be others to look after their child. Darnay then speaks to Doctor Manette and acknowledges the fortitude that he has shown. “Heaven be with you!” Darnay says. Doctor Manette responds with “a shriek of anguish.” As Charles is lead away Lucie faints. Sydney Carton relieves Doctor Manette of Lucie. As he holds her in his arms “there was an air about him that was not all of pity — that had a flush of pride in it.” When the coach reaches their residence Carton carried Lucie to her room and places her on a couch where she is tended by her child and Miss Pross. At this point Sydney Carton softly says “Don’t recall her to herself.”

Now, it is at this point in the novel we shall witness a bit of narrative magic from Dickens. Lucie Manette has fainted. Carton has asked the group not to “recall her to herself.” Little Lucie calls out “Oh Carton, Carton, dear Carton … now that you have come , I think you will do something to help mamma, something to save papa! O, look at her, dear Carton! Can you, of all the people who love her, bear to see her so?” Carton bends over little Lucie and puts her cheek against his face. Carton then asks if he can kiss Lucie. As he bends over her little Lucie hears Carton tell her mother “A life you love.”

Carton then asks Doctor Manette to try once again to plead for Charles. As Sydney Carton leaves Lucie’s residence Mr Lorry, a realistic man, says to Carton “there is no real hope” to which Carton replies “Yes, He will perish: there is no real hope.” And with those parting words Carton “ walked with a settled step, down-stairs.”

Thoughts

Deep breath. And again. By now, it is probably apparent what is about to happen, but I will not give any spoilers away. For those who have an idea of what is about to occur, how are you feeling at this specific point in the novel?

Let’s look at the dynamics of this chapter. Charles Darnay is sentenced to die within 24 hours. Nothing and no one will stop the sentence of the court. Lucie is understandably distraught, Doctor Manette is in shock having heard his own words, written long ago, condemn his son-in-law to death. If we read his words carefully we know that he has condemned to death not only his son-in-law, but others as well. Consider the words “to the last of their race to death.” Who else does that include?

When we look back in the text we recall that Sydney Carton once pledged to Lucie that “for you, and any dear to you, I would do anything.” Little Lucie pleads to Carton to do something to help her mother. The words that Little Lucie hears Sydney Carton whisper into her mother’s ear are “a life you love.” Earlier in this chapter Sydney Carton said “do not recall [Lucie] to herself.” Well, there is that word “recall” again. Dickens is never far from keeping this trope present in the novel in many different iterations.

Did you notice that at the end of the chapter Carton walked “with a settled step, downstairs.” What does the word “settled” suggest about Carton's physical state and his state of mind? It is stated here that Carton walked “down-stairs.” I ask you to keep this movement in your mind.

Why might “Dusk” be a good title for this chapter?

Dusk

“Yes he will perish: there is no real hope,” echoed Carton. And walked with a settled step, down-stairs.

Charles Darnay has been found guilty and will die within 24 hours. With the sentence passed, the spectators in the court pile out into the streets to join in a public demonstration to celebrate. While Darnay was found innocent in the English court, I’m sure the flies that awaited the English verdict would have equally celebrated a death sentence. Darnay is able to speak these words to Lucie: “My parting blessing on my love. We shall meet again where the weary are at rest.” Lucie tells Charles that her heart will break and she will soon follow him. She assures Charles that there will be others to look after their child. Darnay then speaks to Doctor Manette and acknowledges the fortitude that he has shown. “Heaven be with you!” Darnay says. Doctor Manette responds with “a shriek of anguish.” As Charles is lead away Lucie faints. Sydney Carton relieves Doctor Manette of Lucie. As he holds her in his arms “there was an air about him that was not all of pity — that had a flush of pride in it.” When the coach reaches their residence Carton carried Lucie to her room and places her on a couch where she is tended by her child and Miss Pross. At this point Sydney Carton softly says “Don’t recall her to herself.”

Now, it is at this point in the novel we shall witness a bit of narrative magic from Dickens. Lucie Manette has fainted. Carton has asked the group not to “recall her to herself.” Little Lucie calls out “Oh Carton, Carton, dear Carton … now that you have come , I think you will do something to help mamma, something to save papa! O, look at her, dear Carton! Can you, of all the people who love her, bear to see her so?” Carton bends over little Lucie and puts her cheek against his face. Carton then asks if he can kiss Lucie. As he bends over her little Lucie hears Carton tell her mother “A life you love.”

Carton then asks Doctor Manette to try once again to plead for Charles. As Sydney Carton leaves Lucie’s residence Mr Lorry, a realistic man, says to Carton “there is no real hope” to which Carton replies “Yes, He will perish: there is no real hope.” And with those parting words Carton “ walked with a settled step, down-stairs.”

Thoughts

Deep breath. And again. By now, it is probably apparent what is about to happen, but I will not give any spoilers away. For those who have an idea of what is about to occur, how are you feeling at this specific point in the novel?

Let’s look at the dynamics of this chapter. Charles Darnay is sentenced to die within 24 hours. Nothing and no one will stop the sentence of the court. Lucie is understandably distraught, Doctor Manette is in shock having heard his own words, written long ago, condemn his son-in-law to death. If we read his words carefully we know that he has condemned to death not only his son-in-law, but others as well. Consider the words “to the last of their race to death.” Who else does that include?

When we look back in the text we recall that Sydney Carton once pledged to Lucie that “for you, and any dear to you, I would do anything.” Little Lucie pleads to Carton to do something to help her mother. The words that Little Lucie hears Sydney Carton whisper into her mother’s ear are “a life you love.” Earlier in this chapter Sydney Carton said “do not recall [Lucie] to herself.” Well, there is that word “recall” again. Dickens is never far from keeping this trope present in the novel in many different iterations.

Did you notice that at the end of the chapter Carton walked “with a settled step, downstairs.” What does the word “settled” suggest about Carton's physical state and his state of mind? It is stated here that Carton walked “down-stairs.” I ask you to keep this movement in your mind.

Why might “Dusk” be a good title for this chapter?

Chapter 12

Darkness

“Then tell Wind and Fire where to stop,” returned Madame; “but don’t tell me.”

We begin this chapter with questions. First, we read that Sydney Carton has not had any strong drink “for the first time in many years.” Why might that be? The second question is why would Carton want to go to the Defarge’s wine store? We read that before Carton goes in the wine store he stops at a shop window “where there was a mirror, [ Carton ] slightly altered the disordered arrangement of his loose cravat, and his coat-collar, and his wild hair. This done, he went on direct to the Defarge’s, and went in.” Can any Curiosity offer any reasons why Carton took these actions?

We should note yet another mention of a mirror. Throughout the novel we have seen repeated references to mirrors, most in connection with Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton. The fact that there is a reference to a mirror where Carton slightly alters his appearance just before he enters the wine shop is fascinating to me. Reflections, doppelgängers, alterations. There is so much unfolding before us as the novel moves towards its conclusion.

In the wine shop Madame Defarge, Defarge and the Vengeance remark on the similarity in appearance between Carton and Darnay. Carton’s French is good, having studied it while in France as a youth, but he pretends not to understand it. By doing this he is able to accomplish two objects. First, his similarity to Darnay’s looks is confirmed. Second, and just as important, he is able to eavesdrop on the Defarge’s conversation. Through Carton’s eavesdropping we learn that the family so injured by the Evremonde brothers was Madame Defarge’s family. No wonder Madame Defarge hates the Evremonde name. The second thing Carton learns is that the word “extermination” is a doctrine to be followed to the end of the Darnay race.

Sydney Carton returns to consult with Mr Lorry and they both worry when Doctor Manette does not return from his mission to have his son-in-law’s conviction changed. At last Doctor Manette does return - in body - but not in mind. He asks for his work bench. He wants to repair shoes again. From his pocket falls a case with papers inside. They are the papers which will allow Doctor Manette, Lucie and her child to leave Paris. Carton also has a pass that will allow him to leave Paris. This pass he gives to Mr Lorry. Carton then lets the group know what he overheard in the wine shop. Lucie is in great danger. She has been seen making signals to her husband. This is prohibited. Lucie will be seized by the revolutionaries.

At this point Sydney Carton appeals to Mr Lorry to make plans to leave Paris tomorrow. The carriages need to be ready. All haste is necessary. Mr Lorry has Sydney’s certificate and so the moment he arrives everyone must flee back to England. Sydney makes Mr Lorry promise that nothing will be altered in these plans. Lorry does promise. Sydney leaves the house, looks up to Lucy’s window, and then “breathed a blessing towards it, and a Farewell.”

Reflections

Can you feel the pace of the story speeding up? I imagine the first readers of this novel must have been very excited. Many of those readers no doubt anticipated what was going to happen next. To what extent would you say the final chapters of A Tale of Two Cities are as good as, or even better than earlier Dickens novels?

The last word in this chapter is “Farewell.” Normally, this word, in this context, would not be capitalized. Why might the word be capitalized in this instance?

Darkness

“Then tell Wind and Fire where to stop,” returned Madame; “but don’t tell me.”

We begin this chapter with questions. First, we read that Sydney Carton has not had any strong drink “for the first time in many years.” Why might that be? The second question is why would Carton want to go to the Defarge’s wine store? We read that before Carton goes in the wine store he stops at a shop window “where there was a mirror, [ Carton ] slightly altered the disordered arrangement of his loose cravat, and his coat-collar, and his wild hair. This done, he went on direct to the Defarge’s, and went in.” Can any Curiosity offer any reasons why Carton took these actions?

We should note yet another mention of a mirror. Throughout the novel we have seen repeated references to mirrors, most in connection with Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton. The fact that there is a reference to a mirror where Carton slightly alters his appearance just before he enters the wine shop is fascinating to me. Reflections, doppelgängers, alterations. There is so much unfolding before us as the novel moves towards its conclusion.

In the wine shop Madame Defarge, Defarge and the Vengeance remark on the similarity in appearance between Carton and Darnay. Carton’s French is good, having studied it while in France as a youth, but he pretends not to understand it. By doing this he is able to accomplish two objects. First, his similarity to Darnay’s looks is confirmed. Second, and just as important, he is able to eavesdrop on the Defarge’s conversation. Through Carton’s eavesdropping we learn that the family so injured by the Evremonde brothers was Madame Defarge’s family. No wonder Madame Defarge hates the Evremonde name. The second thing Carton learns is that the word “extermination” is a doctrine to be followed to the end of the Darnay race.

Sydney Carton returns to consult with Mr Lorry and they both worry when Doctor Manette does not return from his mission to have his son-in-law’s conviction changed. At last Doctor Manette does return - in body - but not in mind. He asks for his work bench. He wants to repair shoes again. From his pocket falls a case with papers inside. They are the papers which will allow Doctor Manette, Lucie and her child to leave Paris. Carton also has a pass that will allow him to leave Paris. This pass he gives to Mr Lorry. Carton then lets the group know what he overheard in the wine shop. Lucie is in great danger. She has been seen making signals to her husband. This is prohibited. Lucie will be seized by the revolutionaries.

At this point Sydney Carton appeals to Mr Lorry to make plans to leave Paris tomorrow. The carriages need to be ready. All haste is necessary. Mr Lorry has Sydney’s certificate and so the moment he arrives everyone must flee back to England. Sydney makes Mr Lorry promise that nothing will be altered in these plans. Lorry does promise. Sydney leaves the house, looks up to Lucy’s window, and then “breathed a blessing towards it, and a Farewell.”

Reflections

Can you feel the pace of the story speeding up? I imagine the first readers of this novel must have been very excited. Many of those readers no doubt anticipated what was going to happen next. To what extent would you say the final chapters of A Tale of Two Cities are as good as, or even better than earlier Dickens novels?

The last word in this chapter is “Farewell.” Normally, this word, in this context, would not be capitalized. Why might the word be capitalized in this instance?

Things are hectic around here, and I lament that I've not been able to focus on Dickens, or anything else much, for that matter. But with the help of youtube, I've managed to get though this week's segment. Dickens is starting to cross those Ts and dot those Is, wrapping everything up in a nice bow for us. I've forgotten so much of this story, and have been surprised at how tightly woven it is.

Things are hectic around here, and I lament that I've not been able to focus on Dickens, or anything else much, for that matter. But with the help of youtube, I've managed to get though this week's segment. Dickens is starting to cross those Ts and dot those Is, wrapping everything up in a nice bow for us. I've forgotten so much of this story, and have been surprised at how tightly woven it is. Once again, my shallow attention span has gotten the better of me and I must ask for some clarification. Why was the doctor's rebuke of the Evermonde family so... hmm... holistic, after the mother came to him seeking a way to make amends, and vowing that she'd raise her son to continue that quest? Did I misunderstand this? His condemnation of the brothers is understandable but, as Peter points out, Doctor Manette’s own words were “them and their dependents to the last of their race.” Ill-advised hyperbole? Or did he not trust Mme. Evermonde?

I have another question here that may have to wait until next week for an answer, namely: Why was it important to Carton to have the Defarges see his resemblance to Darnay?

(And an aside: We now know the motivation behind Mme. Defarge, but why is "the Vengeance" so bloodthirsty? I suppose many families had similar stories, and we must content ourselves with that explanation.)

Things are speeding along nicely now, and I hope I can give next week's final installment closer attention. Aside from the opening scene of the people drinking wine off the street, the one scene I clearly remember from my first reading many years ago (which caused me to whoop aloud!) is coming up; I have looked forward to revisiting it. :-)

Hi Mary Lou

Don’t worry about your attention span. I’ve just returned from a babysitting odyssey with two of our grandchildren. I think I am still sane.

The backstory of Madame Defarge and her family seems to be intact but there are a few threads of confusion. The bit with Charles’s mother seems like a dead end. Pun perhaps intended. :-)

I think Sydney’s testing of the Defarge’s is just that. How can I pull this scheme off? And yes, the bit about the mirror was a nice Dickensian touch given the fact Darnay and Carton have spent some time gazing up at the ceiling in London and each other for years during their time in London.

As for the Vengence. My guess is Dickens wanted a female ´sidekick’ who was as invested in horror and destruction as Mme Defarge was. Defarge may have a good reason to hate the aristocracy (and the Evermonde’s in particular) but the Vengeance is just that. She is the embodiment of hate manifest as a human form. A chilling person to be sure.

Don’t worry about your attention span. I’ve just returned from a babysitting odyssey with two of our grandchildren. I think I am still sane.

The backstory of Madame Defarge and her family seems to be intact but there are a few threads of confusion. The bit with Charles’s mother seems like a dead end. Pun perhaps intended. :-)

I think Sydney’s testing of the Defarge’s is just that. How can I pull this scheme off? And yes, the bit about the mirror was a nice Dickensian touch given the fact Darnay and Carton have spent some time gazing up at the ceiling in London and each other for years during their time in London.

As for the Vengence. My guess is Dickens wanted a female ´sidekick’ who was as invested in horror and destruction as Mme Defarge was. Defarge may have a good reason to hate the aristocracy (and the Evermonde’s in particular) but the Vengeance is just that. She is the embodiment of hate manifest as a human form. A chilling person to be sure.

Well, Defarge appears to have let me down. It's interesting that the narrator describes him as weak: "Defarge, a weak minority." Everyone else is bent on running their vengeance as far as it can go, and while he doesn't agree, he doesn't have the strength to stand up to them.

Well, Defarge appears to have let me down. It's interesting that the narrator describes him as weak: "Defarge, a weak minority." Everyone else is bent on running their vengeance as far as it can go, and while he doesn't agree, he doesn't have the strength to stand up to them. No wonder I forgot what became of him. In the end (if this is the end for him), he's pretty forgettable. I am disappointed, but not in the book. It does make sense. Not everyone is fundamentally horrible: some people just go along with things they don't particularly feel they can or should stand against.

Look at Manette, though! Here's Darnay speaking to him at the conclusion of his trial:

“No, no! What have you done, what have you done, that you should kneel to us! We know now, what a struggle you made of old. We know, now what you underwent when you suspected my descent, and when you knew it. We know now, the natural antipathy you strove against, and conquered, for her dear sake. We thank you with all our hearts, and all our love and duty. Heaven be with you!”

Of course Manette falls apart after that, but I don't blame him. He vowed vengeance just like Madame Defarge, but he found in himself the strength to take it back. I don't see him as weak at all. He doesn't lose his mind until there's nothing left for him to do with it: he's given all he can.

Peter, thank you for pointing out all the ways that resurrection is playing as a theme here. I don't think Cruncher's variety of resurrection is really much of a parallel to the kind of sacrifice and resurrection we see happening in the rest of the book--but it does serve to keep the theme front and center for us, repeatedly.

Peter, thank you for pointing out all the ways that resurrection is playing as a theme here. I don't think Cruncher's variety of resurrection is really much of a parallel to the kind of sacrifice and resurrection we see happening in the rest of the book--but it does serve to keep the theme front and center for us, repeatedly. I don't know, does anyone else have thoughts on what digging up bodies for medical research might have to do with the rest of this? Loosely, I suppose it is a good that comes out of an evil.

Julie wrote: "Peter, thank you for pointing out all the ways that resurrection is playing as a theme here. I don't think Cruncher's variety of resurrection is really much of a parallel to the kind of sacrifice a..."

Hi Julie

Jerry’s part-time job as a resurrection man was an occupation that did exist and was more common that one would think. One reason was the expansion and interest in operations, the anatomy of a human, the money paid by medical schools and back alley quacks and partly due to the methods of burial. Graveyards were overflowing (yuck) with bodies. Coffins were often stacked one on top of another, or worse, older coffins were crushed so as to make more room for newer burials. When we get to OMF we will revisit burial procedures.

Now, as to how the role of Jerry fits into the novel, that’s a great question. I think, partly, it was Dickens pointing out a very distasteful practice, and partly to suggest another form of how one could be resurrected. TTC is so gloomy. Jerry and his son add to this distaste.

Gray’s Anatomy was published in London in 1858. I suspect it caused quite a stir. There must have been a Jerry or two who helped Gray. With the publication of TTC soon afterward I wonder if Dickens did not ride the publication of Gray’s Anatomy to some extent.

Hi Julie

Jerry’s part-time job as a resurrection man was an occupation that did exist and was more common that one would think. One reason was the expansion and interest in operations, the anatomy of a human, the money paid by medical schools and back alley quacks and partly due to the methods of burial. Graveyards were overflowing (yuck) with bodies. Coffins were often stacked one on top of another, or worse, older coffins were crushed so as to make more room for newer burials. When we get to OMF we will revisit burial procedures.

Now, as to how the role of Jerry fits into the novel, that’s a great question. I think, partly, it was Dickens pointing out a very distasteful practice, and partly to suggest another form of how one could be resurrected. TTC is so gloomy. Jerry and his son add to this distaste.

Gray’s Anatomy was published in London in 1858. I suspect it caused quite a stir. There must have been a Jerry or two who helped Gray. With the publication of TTC soon afterward I wonder if Dickens did not ride the publication of Gray’s Anatomy to some extent.

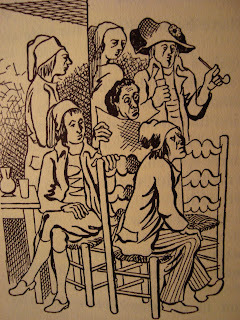

The double recognition

Book III Chapter 8

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"As their wine was measuring out, a man parted from another man in a corner, and rose to depart. In going, he had to face Miss Pross. No sooner did he face her, than Miss Pross uttered a scream, and clapped her hands.

In a moment, the whole company were on their feet. That somebody was assassinated by somebody vindicating a difference of opinion was the likeliest occurrence. Everybody looked to see somebody fall, but only saw a man and a woman standing staring at each other; the man with all the outward aspect of a Frenchman and a thorough Republican; the woman, evidently English."

After the sentence

Book III Chapter 11

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"My husband. No! A moment!" He was tearing himself apart from her. "We shall not be separated long. I feel that this will break my heart by-and-bye; but I will do my duty while I can, and when I leave her, God will raise up friends for her, as He did for me."

Her father had followed her, and would have fallen on his knees to both of them, but that Darnay put out a hand and seized him, crying:

"No, no! What have you done, what have you done, that you should kneel to us! We know now, what a struggle you made of old. We know, now what you underwent when you suspected my descent, and when you knew it. We know now, the natural antipathy you strove against, and conquered, for her dear sake. We thank you with all our hearts, and all our love and duty. Heaven be with you!"

Her father's only answer was to draw his hands through his white hair, and wring them with a shriek of anguish.

"It could not be otherwise," said the prisoner. "All things have worked together as they have fallen out. It was the always-vain endeavour to discharge my poor mother's trust that first brought my fatal presence near you. Good could never come of such evil, a happier end was not in nature to so unhappy a beginning. Be comforted, and forgive me. Heaven bless you!"

As he was drawn away, his wife released him, and stood looking after him with her hands touching one another in the attitude of prayer, and with a radiant look upon her face, in which there was even a comforting smile. As he went out at the prisoners' door, she turned, laid her head lovingly on her father's breast, tried to speak to him, and fell at his feet."

Headnote vignette

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, chapter 8 ("A Hand at Cards")

Harper's Weekly October 1859

Text Illustrated:

"Having purchased a few small articles of grocery, and a measure of oil for the lamp, Miss Pross bethought herself of the wine they wanted. After peeping into several wine-shops, she stopped at the sign of the Good Republican Brutus of Antiquity, not far from the National Palace, once (and twice) the Tuileries, where the aspect of things rather took her fancy. It had a quieter look than any other place of the same description they had passed, and, though red with patriotic caps, was not so red as the rest. Sounding Mr. Cruncher, and finding him of her opinion, Miss Pross resorted to the Good Republican Brutus of Antiquity, attended by her cavalier.

Slightly observant of the smoky lights; of the people, pipe in mouth, playing with limp cards and yellow dominoes; of the one bare-breasted, bare-armed, soot-begrimed workman reading a journal aloud, and of the others listening to him; of the weapons worn, or laid aside to be resumed; of the two or three customers fallen forward asleep, who in the popular high-shouldered shaggy black spencer looked, in that attitude, like slumbering bears or dogs; the two outlandish customers approached the counter, and showed what they wanted."

"So you put him in his coffin!"

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, chapter 8 ("A Hand at Cards")

Harper's Weekly October 1859

Text Illustrated:

"Here, Mr. Lorry perceived the reflection on the wall to elongate, and Mr. Cruncher rose and stepped forward. His hair could not have been more violently on end, if it had been that moment dressed by the Cow with the crumpled horn in the house that Jack built.

Unseen by the spy, Mr. Cruncher stood at his side, and touched him on the shoulder like a ghostly bailiff.

"That there Roger Cly, master," said Mr. Cruncher, with a taciturn and iron-bound visage. "So you put him in his coffin?"

"I did."

"Who took him out of it?"

Barsad leaned back in his chair, and stammered, "What do you mean?"

"I mean," said Mr. Cruncher, "that he warn't never in it. No! Not he! I'll have my head took off, if he was ever in it."

The spy looked round at the two gentlemen; they both looked in unspeakable astonishment at Jerry.

"I tell you," said Jerry, "that you buried paving-stones and earth in that there coffin. Don't go and tell me that you buried Cly. It was a take in. Me and two more knows it."

Book III Chapter 9

John McLenan

Harper's Weekly October 1859

Text Illustrated:

"While Sydney Carton and the Sheep of the prisons were in the adjoining dark room, speaking so low that not a sound was heard, Mr. Lorry looked at Jerry in considerable doubt and mistrust. That honest tradesman's manner of receiving the look, did not inspire confidence; he changed the leg on which he rested, as often as if he had fifty of those limbs, and were trying them all; he examined his finger-nails with a very questionable closeness of attention; and whenever Mr. Lorry's eye caught his, he was taken with that peculiar kind of short cough requiring the hollow of a hand before it, which is seldom, if ever, known to be an infirmity attendant on perfect openness of character."

"This is that written paper!"

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, chapter 9

Harper's Weekly October 1859

Text Illustrated:

"I knew," said Defarge, looking down at his wife, who stood at the bottom of the steps on which he was raised, looking steadily up at him; "I knew that this prisoner, of whom I speak, had been confined in a cell known as One Hundred and Five, North Tower. I knew it from himself. He knew himself by no other name than One Hundred and Five, North Tower, when he made shoes under my care. As I serve my gun that day, I resolve, when the place shall fall, to examine that cell. It falls. I mount to the cell, with a fellow-citizen who is one of the Jury, directed by a gaoler. I examine it, very closely. In a hole in the chimney, where a stone has been worked out and replaced, I find a written paper. This is that written paper. I have made it my business to examine some specimens of the writing of Doctor Manette. This is the writing of Doctor Manette. I confide this paper, in the writing of Doctor Manette, to the hands of the President."

"Let it be read."

In a dead silence and stillness—the prisoner under trial looking lovingly at his wife, his wife only looking from him to look with solicitude at her father, Doctor Manette keeping his eyes fixed on the reader, Madame Defarge never taking hers from the prisoner, Defarge never taking his from his feasting wife, and all the other eyes there intent upon the Doctor, who saw none of them—the paper was read, as follows:

Headnote vignette

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, chapter 10 ( "The Substance of the Shadow")

Harper's Weekly November 1859

Text Illustrated:

From the narrative of Dr. Mannette:

"One cloudy moonlight night, in the third week of December (I think the twenty-second of the month) in the year 1757, I was walking on a retired part of the quay by the Seine for the refreshment of the frosty air, at an hour's distance from my place of residence in the Street of the School of Medicine, when a carriage came along behind me, driven very fast. As I stood aside to let that carriage pass, apprehensive that it might otherwise run me down, a head was put out at the window, and a voice called to the driver to stop.

"The carriage stopped as soon as the driver could rein in his horses, and the same voice called to me by my name. I answered. The carriage was then so far in advance of me that two gentlemen had time to open the door and alight before I came up with it.

"I observed that they were both wrapped in cloaks, and appeared to conceal themselves. As they stood side by side near the carriage door, I also observed that they both looked of about my own age, or rather younger, and that they were greatly alike, in stature, manner, voice, and (as far as I could see) face too.

"'You are Doctor Manette?' said one.

"I am."

"'Doctor Manette, formerly of Beauvais,' said the other; 'the young physician, originally an expert surgeon, who within the last year or two has made a rising reputation in Paris?'

"'Gentlemen,' I returned, 'I am that Doctor Manette of whom you speak so graciously.' 'We have been to your residence,' said the first, 'and not being so fortunate as to find you there, and being informed that you were probably walking in this direction, we followed, in the hope of overtaking you. Will you please to enter the carriage?' "The manner of both was imperious, and they both moved, as these words were spoken, so as to place me between themselves and the carriage door. They were armed. I was not. "'Gentlemen,' said I, `pardon me; but I usually inquire who does me the honour to seek my assistance, and what is the nature of the case to which I am summoned.' "The reply to this was made by him who had spoken second. 'Doctor, your clients are people of condition. As to the nature of the case, our confidence in your skill assures us that you will ascertain it for yourself better than we can describe it. Enough. Will you please to enter the carriage?"

"I mark this cross of blood upon him, as a sign that I do it"

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, chapter 10 ("The Substance of the Shadow")

Harper's Weekly November 1859

Text Illustrated:

"The room was darkening to his sight; the world was narrowing around him. I glanced about me, and saw that the hay and straw were trampled over the floor, as if there had been a struggle.

"'She heard me, and ran in. I told her not to come near us till he was dead. He came in and first tossed me some pieces of money; then struck at me with a whip. But I, though a common dog, so struck at him as to make him draw. Let him break into as many pieces as he will, the sword that he stained with my common blood; he drew to defend himself—thrust at me with all his skill for his life.'

"My glance had fallen, but a few moments before, on the fragments of a broken sword, lying among the hay. That weapon was a gentleman's. In another place, lay an old sword that seemed to have been a soldier's.

"'Now, lift me up, Doctor; lift me up. Where is he?'

"'He is not here,' I said, supporting the boy, and thinking that he referred to the brother.

"'He! Proud as these nobles are, he is afraid to see me. Where is the man who was here? Turn my face to him.'

"I did so, raising the boy's head against my knee. But, invested for the moment with extraordinary power, he raised himself completely: obliging me to rise too, or I could not have still supported him.

"'Marquis,' said the boy, turned to him with his eyes opened wide, and his right hand raised, 'in the days when all these things are to be answered for, I summon you and yours, to the last of your bad race, to answer for them. I mark this cross of blood upon you, as a sign that I do it. In the days when all these things are to be answered for, I summon your brother, the worst of the bad race, to answer for them separately. I mark this cross of blood upon him, as a sign that I do it.'

"Twice, he put his hand to the wound in his breast, and with his forefinger drew a cross in the air. He stood for an instant with the finger yet raised, and as it dropped, he dropped with it, and I laid him down dead."

Headnote vignette

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, chapter 11 ("Dusk")

Harper's Weekly November 1859

Text Illustrated:

"When he had gone out into the next room, he turned suddenly on Mr. Lorry and her father, who were following, and said to the latter:

"You had great influence but yesterday, Doctor Manette; let it at least be tried. These judges, and all the men in power, are very friendly to you, and very recognisant of your services; are they not?"

"Nothing connected with Charles was concealed from me. I had the strongest assurances that I should save him; and I did." He returned the answer in great trouble, and very slowly.

"Try them again. The hours between this and to-morrow afternoon are few and short, but try."

"I intend to try. I will not rest a moment."

"That's well. I have known such energy as yours do great things before now—though never," he added, with a smile and a sigh together, "such great things as this. But try! Of little worth as life is when we misuse it, it is worth that effort. It would cost nothing to lay down if it were not."

"I will go," said Doctor Manette, "to the Prosecutor and the President straight, and I will go to others whom it is better not to name. I will write too, and—But stay! There is a Celebration in the streets, and no one will be accessible until dark."

"That's true. Well! It is a forlorn hope at the best, and not much the forlorner for being delayed till dark. I should like to know how you speed; though, mind! I expect nothing! When are you likely to have seen these dread powers, Doctor Manette?"

"Immediately after dark, I should hope. Within an hour or two from this."

"It will be dark soon after four. Let us stretch the hour or two. If I go to Mr. Lorry's at nine, shall I hear what you have done, either from our friend or from yourself?"

"Yes."

"May you prosper!"

"I swear to you, like Evremonde!"

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, chapter 12 ("Darkness")

Harper's Weekly November 1859

Text Illustrated:

"After looking at her, as if the sound of even a single French word were slow to express itself to him, he answered, in his former strong foreign accent. "Yes, madame, yes. I am English!"

Madame Defarge returned to her counter to get the wine, and, as he took up a Jacobin journal and feigned to pore over it puzzling out its meaning, he heard her say, "I swear to you, like Evremonde!"

Defarge brought him the wine, and gave him Good Evening.

"How?"

"Good evening."

"Oh! Good evening, citizen," filling his glass. "Ah! and good wine. I drink to the Republic."

Defarge went back to the counter, and said, "Certainly, a little like." Madame sternly retorted, "I tell you a good deal like." Jacques Three pacifically remarked, "He is so much in your mind, see you, madame." The amiable Vengeance added, with a laugh, "Yes, my faith! And you are looking forward with so much pleasure to seeing him once more to-morrow!"

Carton followed the lines and words of his paper, with a slow forefinger, and with a studious and absorbed face. They were all leaning their arms on the counter close together, speaking low. After a silence of a few moments, during which they all looked towards him without disturbing his outward attention from the Jacobin editor, they resumed their conversation."

"Here Mr. Lorry became aware, from where he sat, of a most remarkable goblin shadow on the wall"

Book III Chapter 8

Fred Barnard

The Household Edition 1870s

Text Illustrated:

"While he was at a loss, Carton said, resuming his former air of contemplating cards:

"And, indeed, now I think again, I have a strong impression that I have another good card here, not yet enumerated. That friend and fellow-Sheep, who spoke of himself as pasturing in the country prisons; who was he?"

"French. You don't know him," said the spy quickly.

"French, eh?" repeated Carton, musing, and not appearing to notice him at all, though he echoed his word. "Well; he may be."

"Is, I assure you," said the spy; "though it's not important."

"Though it's not important," repeated Carton in the same mechanical way — "though it's not important — No, it's not important. No. Yet I know the face."

"I think not. I am sure not. It can't be," said the spy.

"It — can't — be," muttered Sydney Carton retrospectively, and filling his glass (which fortunately was a small one) again. "Can't — be. Spoke good French. Yet like a foreigner, I thought?"

"Provincial," said the spy.

"No. Foreign!" cried Carton, striking his open hand on the table, as a light broke clearly on his mind. "Cly! Disguised, but the same man. We had that man before us at the Old Bailey."

"Now, there you are hasty, sir," said Barsad, with a smile that gave his aquiline nose an extra inclination to one side; "there you really give me an advantage over you. Cly (who I will unreservedly admit, at this distance of time, was a partner of mine) has been dead several years. I attended him in his last illness. He was buried in London, at the church of Saint Pancras-in-the-Fields. His unpopularity with the blackguard multitude at the moment prevented my following his remains, but I helped to lay him in his coffin."

Here Mr. Lorry became aware, from where he sat, of a most remarkable goblin shadow on the wall. Tracing it to its source, he discovered it to be caused by a sudden extraordinary rising and stiffening of all the risen and stiff hair on Mr. Cruncher's head.

"Let us be reasonable," said the spy, "and let us be fair. To show you how mistaken you are, and what an unfounded assumption yours is, I will lay before you a certificate of Cly's burial, which I happened to have carried in my pocket-book," — with a hurried hand he produced and opened it — "ever since. There it is. Oh, look at it, look at it! You may take it in your hand; it's no forgery."

Commentary:

Sydney Carton seizes the opportunity that the unmasking of Miss Pross's long-lost brother, Solomon, as the former English and ancien regime "intelligence-gatherer" and informer John Barsad, "The Sheep of the Prisons," presents him. Carton now threatens to denounce Barsad and his former accomplice Roger Cly as foreign spies in "A Hand at Cards".

Having suddenly discovered the explanation behind the empty coffin that he opened after the funeral of Roger Cly, Jerry Cruncher experiences a sudden shock as he listens to the dialogue between Carton and the turnkey at the Conciergerie (where Darnay has just been consigned after being re-arrested). The figures from left to right in the illustration are the elderly English banker Jarvis Lorry, the alcoholic attorney who speaks perfect French, Sydney Carton (just arrived from London), the "Resurrection Man" and quondam Tellson's messenger, Jerry Cruncher, and in a topcoat of French fashion John Barsad, now an official of the Republic. The scene is Jarvis Lorry's residence, just a few minutes' walk from the little wine-shop by the Pont Neuf where Miss Pross had recognized her brother.

But the certificate is a forgery, of course, leading the reader to wonder how far the trio should place their confidence in such a duplicitous rogue. Carton leans toward his interlocutor, grasping the brandy glass that he has been continually filling and draining, as he realizes he has sufficient evidence to condemn Barsad — unless of course Barsad agrees to assist him in his scheme (as yet undisclosed) to free Charles Darnay. Whereas John McLenan in the Harper's Weekly series had depicted the same group and realized almost the same narrative moment in "So you put him in his coffin!" (22 October 1859), McLenan had made the realization more theatrical by having Jerry rise to denounce Barsad. McLenan's Carton, not confronting Barsad, seems less astute; McLenan's Jerry is much stockier and muscular (note the great hand he lays on Barsad's shoulder); and his Barsad a thoroughly disreputable-looking Jacobin in a Phyrgian cap and drooping moustache. McLenan's realization lacks the dramatic tension that thoroughly informs Barnard's.

Barnard, known for his love of eccentric Dickens characters, cannot resist making Jerry a comic foil — his hair reminding the Household Edition reader of the tonsorial style of Seth Pecksniff in Barnard's illustrations for Martin Chuzzlewit. The illustration thus is an interesting blend of physical humor and growing suspense as the reader laughs at Jerry's reaction but wonders how Carton can blackmail Barsad into helping him break Darnay out of one of the Revolution's most secure prisons.

Phiz in one of the final four illustrations, "The Double Recognition", dealt with the crucial moment in which Miss Pross identifies one of the very French-looking customers of the Pont Neuf wine-shop as her wayward brother, Solomon; the customers in the left-hand register suspect that something is amiss; and Phiz so positions the turncoat spy that Miss Pross can see his face, but the reader cannot. Despite the importance to the plot of "The Double Recognition," the style of the picture is somewhat whimsical, with Miss Pross and Jerry Cruncher providing a comic counterpoint to Dickens's text. In terms of its dominant mood, then, Barnard's twentieth illustration is a considerable advance in capturing the essence of the text realized and treating the figures with a seriousness appropriate to the narrative's revelation, a seriousness underscored by the darkness of the scene, the chiaroscuro of the candles in the center, and shadow which seems to engulf the gesticulating figure in the great-coat.

"Twice he put his hand to the wound in his breast, and with his forefinger drew a cross in the air"

Book III Chapter 10

Fred Barnard

The Household Edition 1870s

Text Illustrated:

"The room was darkening to his sight; the world was narrowing around him. I glanced about me, and saw that the hay and straw were trampled over the floor, as if there had been a struggle.

"'She heard me, and ran in. I told her not to come near us till he was dead. He came in and first tossed me some pieces of money; then struck at me with a whip. But I, though a common dog, so struck at him as to make him draw. Let him break into as many pieces as he will, the sword that he stained with my common blood; he drew to defend himself—thrust at me with all his skill for his life.'

"My glance had fallen, but a few moments before, on the fragments of a broken sword, lying among the hay. That weapon was a gentleman's. In another place, lay an old sword that seemed to have been a soldier's.

"'Now, lift me up, Doctor; lift me up. Where is he?'

"'He is not here,' I said, supporting the boy, and thinking that he referred to the brother.

"'He! Proud as these nobles are, he is afraid to see me. Where is the man who was here? Turn my face to him.'

"I did so, raising the boy's head against my knee. But, invested for the moment with extraordinary power, he raised himself completely: obliging me to rise too, or I could not have still supported him.

"'Marquis,' said the boy, turned to him with his eyes opened wide, and his right hand raised, 'in the days when all these things are to be answered for, I summon you and yours, to the last of your bad race, to answer for them. I mark this cross of blood upon you, as a sign that I do it. In the days when all these things are to be answered for, I summon your brother, the worst of the bad race, to answer for them separately. I mark this cross of blood upon him, as a sign that I do it.'

"Twice, he put his hand to the wound in his breast, and with his forefinger drew a cross in the air. He stood for an instant with the finger yet raised, and as it dropped, he dropped with it, and I laid him down dead."

Commentary:

In the story-within-a story, Dr. Manette's epistolary denunciation of the St. Evrémonde brothers, his patient (Terese Defarge's brother, in fact), dying, damns the twin aristocrats for crimes against him and his family. In a rather melodramatic manner, Barnard divides the flashback's illustration along class lines, with the brothers St. Evrémonde, standing in their superior postures and wearing fashionable cloaks, wigs, and hats (left), and young Dr. Alexandre Manette supporting his poorly dressed patient, slain while trying to rescue his sister from the twin sexual predators. The peasant boy's sword — an old sabre that once belonged to an ancestor who served in the French army — lies in the foreground, between the two groups.

In this serial historical novel, written and originally illustrated over sixty years after the events it purportedly recounts, it is appropriate that the plot secret lies buried in the Bastille and is liberated on the very day of the prison-fortress's destruction. The 1767 narrative penned by the Bastille prisoner who was once the young physician Alexandre Manette at last brings to light in a French court the heinous deeds (executed a full century before the novel's publication) of the Marquis St. Evrémonde, Charles Darnay's father, and his younger brother and successor, later murdered in his bed by the road-mender Gaspard. Since the lad is pointing at the Marquis, Charles's father is the nobleman leaning forward with his hand on his knee, and the rapist is the other man, whose nemesis comes some thirty years later, after his carriage, careening through the streets of Saint Antoine, crushes the life out of another peasant girl. This testimony, read into the transcript of the trial, causes a sensation in both the Revolutionary court and the mind of the Victorian reader. The abuses of the ancien regime become insistently real as one reads of the younger St. Evrémonde's exercising his antiquated privilege, droit de seigneur, upon Terese Defarge's beautiful sister and then liquidating the rest of the peasant family, except Terese. Ironically, these unspeakable events transpired in Christmas week, 1757.

Barnard's effectively realizing his vision of the remote event makes it as insistently real as any from the period of the two revolutions that are the bookmarks of the story, the American and French risings against the oppressive colonizers. Barnard, as we have seen, has realized the precise moment at which the youth dying in the loft above his family's stable curses the present Marquis St. Evrémonde and all his line in Dr. Manette's blood-and-iron narrative of past wrongs to be avenged by and upon the next generation.

Although Phiz did not attempt to realize this sensational material, John McLenan in the Harper's Weekly series depicted the moment when Defarge reveals to the court the document he retrieved from Dr. Manette's cell in "This is that paper written!" (22 October 1859). McLenan realizes the moment at which the verdict against Darnay is assured as the courtroom erupts at the revelation; Barnard takes the reader back in time to discover in a telling image how such licentious aristocrats as the St. Evrémondes through their utter disregard for law and morality provided the fuel that would eventually supply the justification for the conflagration of revolution.

"As he was drawn away, his wife released him, and stood looking after him with her hands touching one another in the attitude of prayer"

Book III Chapter 11

Fred Barnard

The Household Edition 1870s

Text Illustrated:

"The wretched wife of the innocent man thus doomed to die, fell under the sentence, as if she had been mortally stricken. But, she uttered no sound; and so strong was the voice within her, representing that it was she of all the world who must uphold him in his misery and not augment it, that it quickly raised her, even from that shock.

The Judges having to take part in a public demonstration out of doors, the Tribunal adjourned. The quick noise and movement of the court's emptying itself by many passages had not ceased, when Lucie stood stretching out her arms towards her husband, with nothing in her face but love and consolation.

"If I might touch him! If I might embrace him once! O, good citizens, if you would have so much compassion for us!"

There was but a gaoler left, along with two of the four men who had taken him last night, and Barsad. The people had all poured out to the show in the streets. Barsad proposed to the rest, "Let her embrace him then; it is but a moment." It was silently acquiesced in, and they passed her over the seats in the hall to a raised place, where he, by leaning over the dock, could fold her in his arms.

"Farewell, dear darling of my soul. My parting blessing on my love. We shall meet again, where the weary are at rest!"

They were her husband's words, as he held her to his bosom.

"I can bear it, dear Charles. I am supported from above: don't suffer for me. A parting blessing for our child."

"I send it to her by you. I kiss her by you. I say farewell to her by you."

"My husband. No! A moment!" He was tearing himself apart from her. "We shall not be separated long. I feel that this will break my heart by-and-bye; but I will do my duty while I can, and when I leave her, God will raise up friends for her, as He did for me."

Her father had followed her, and would have fallen on his knees to both of them, but that Darnay put out a hand and seized him, crying:

"No, no! What have you done, what have you done, that you should kneel to us! We know now, what a struggle you made of old. We know, now what you underwent when you suspected my descent, and when you knew it. We know now, the natural antipathy you strove against, and conquered, for her dear sake. We thank you with all our hearts, and all our love and duty. Heaven be with you!"

Her father's only answer was to draw his hands through his white hair, and wring them with a shriek of anguish.

"It could not be otherwise," said the prisoner. "All things have worked together as they have fallen out. It was the always-vain endeavour to discharge my poor mother's trust that first brought my fatal presence near you. Good could never come of such evil, a happier end was not in nature to so unhappy a beginning. Be comforted, and forgive me. Heaven bless you!"

As he was drawn away, his wife released him, and stood looking after him with her hands touching one another in the attitude of prayer, and with a radiant look upon her face, in which there was even a comforting smile. As he went out at the prisoners' door, she turned, laid her head lovingly on her father's breast, tried to speak to him, and fell at his feet."

Well that was depressing.

Commentary:

In the aftermath of the reading into the court transcript of Dr. Alexandre Manette's 1767 epistolary denunciation of the St. Evrémonde brothers, his beloved son-in-law, now indicted as an enemy of the People and the Republic, leaves the courtroom under guard, to be executed the following day.

As in early stage adaptations of the novel, such as Fox Cooper's at The Victoria Theatre, London (7 July 1860) or Tom Taylor's at the Lyceum, London (28 January through 17 March 1860), the crowd scene "The Trial of Evrémonde", concluded and the prisoner by unanimous vote consigned to the Conciergerie and thence to the guillotine, "a notorious oppressor of the People" the liberal aristocrat who turned his back on his aristocratic lineage and wealth now makes his exit. Whether Fred Barnard, only fourteen at time those plays debuted, would actually have attended a performance of a stage adaptation of the novel prior to his Household Edition commission in the 1870s is uncertain, but he conceives of the moment as being theatrically staged. The picture has all the qualities of a tableau vivant.

Whereas Phiz had charged his realization of the scene with melodramatic emotion in "After the Sentence", showing Lucie swooning in her husband's arms immediately after the reading of the dread sentence, as her father tears his hair and Lorry stands helplessly by, here Fred Barnard captures the moment of dignified stillness that follows when, having embraced her husband for the last time (she thinks), Lucie releases Charles. The Household Edition illustrator disposes his figures across the space, directing the gazes of the characters upstage, to the departing Charles Darnay, organizing the characters into two groups of three; downstage right (i. e., the viewer's left), the psychologically shattered Dr. Manette, "draw[ing] his hands through his white hair, and wring[ing] them with a shriek of anguish", Jarvis Lorry, and Lucie; upstage left, a guard, Darnay, and the turnkey or gaoler, identified by his keys — presumably the shadowy profile just outside the door is Barsad's. Like Auguste Rodin's The Burghers of Calais (i. e., Les Bourgeois de Calais), 1889, the six figures convey in their poses and expressions differing responses to a death sentence imposed by an implacable and arbitrary judgment, from Dr. Manette's mental and emotional prostration, to Mr. Lorry's uncertainty as to how to act, to Lucie's tenderly waving farewell (not the attitude of prayer that Dickens specifies), to Darnay's stoical resignation. Foiling these attitudes are the guard's obvious indifference to the emotional parting and the gaoler's stern resolve to do his duty in liquidating a man who, despite his sympathetic domestic circumstances and nobility of character, is "At heart and by descent an Aristocrat", and therefore one to whom no true Citizen of the Republic should show pity. In contrast, all three functionaries of the justice system (left) in Phiz's illustration seem oblivious to the moving scene transpiring just feet away. Darnay turns from profile just slightly to exchange a parting, enigmatic glance."

Here's The Burghers of Calais:

"His head and throat were bare, and as he spoke with a helpless look straying all around, he took his coat off, and let it drop on the floor"

Book III Chapter 12

Fred Barnard

The Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

"Mr. Lorry waited until ten; but, Doctor Manette not returning, and he being unwilling to leave Lucie any longer, it was arranged that he should go back to her, and come to the banking-house again at midnight. In the meanwhile, Carton would wait alone by the fire for the Doctor.

He waited and waited, and the clock struck twelve; but Doctor Manette did not come back. Mr. Lorry returned, and found no tidings of him, and brought none. Where could he be?

They were discussing this question, and were almost building up some weak structure of hope on his prolonged absence, when they heard him on the stairs. The instant he entered the room, it was plain that all was lost.

Whether he had really been to any one, or whether he had been all that time traversing the streets, was never known. As he stood staring at them, they asked him no question, for his face told them everything.

"I cannot find it," said he, "and I must have it. Where is it?"

His head and throat were bare, and, as he spoke with a helpless look straying all around, he took his coat off, and let it drop on the floor.

"Where is my bench? I have been looking everywhere for my bench, and I can't find it. What have they done with my work? Time presses: I must finish those shoes."

They looked at one another, and their hearts died within them.

"Come, come!" said he, in a whimpering miserable way; "let me get to work. Give me my work."

Receiving no answer, he tore his hair, and beat his feet upon the ground, like a distracted child.

"Don't torture a poor forlorn wretch," he implored them, with a dreadful cry; "but give me my work! What is to become of us, if those shoes are not done to-night?"

Lost, utterly lost!"

Commentary:

As a consequence of Charles Darnay's being consigned to the guillotine as a member of the notorious St. Evrémonde family, Doctor Manette had left Tellson's on the same day as the announcing of the verdict, at 4:00 P. M., convinced that as a former Bastille prisoner he could persuade someone in authority to reverse the sentence; just after midnight, he returns, quite out of his senses.

As the novel moves to the culmination of the conflict between Terese Defarge, the sole survivor of her peasant family, and the St. Evrémonde family, Doctor Manette has suffered a double reversal: his attempts to use his status as a former Bastille prisoner as leverage with the officials of the revolutionary regime fail, and he loses his grip on present reality and reverts to his shoemaker identity.

As the original illustrator, Phiz, had suggested in the November 1859 illustration "After the Sentence", Doctor Manette is distraught after the reading of the death sentence upon his son-in-law; however, in the text he is still capable of making one final attempt to save Charles from the guillotine. Vowing to try both the Prosecutor and the President of the revolutionary tribunal, as well as "others whom it is better not to name", Doctor Manette leaves Tellson's in the late afternoon. Lorry and Carton, however, are privately convinced that their friend's mission will be fruitless because the new regime's minions will remain implacable to so notorious an enemy of the People. Now, having traversed the streets of the capital all evening to no avail, the Doctor returns after midnight, broken in spirit, his hair askew: "His head and throat were bare, and, as he spoke with a helpless look straying all around", unable to find his shoe-maker's bench and tools, the long-time properties of psychological survival amidst the wretched conditions of the Bastille. The stress of the state trial and its dread verdict have done their worst, shattering the sanity reacquired in the years of freedom. His raving "I must finish those shoes" bespeaks a mind struggling for balance and control in the face of chaos. He tears his hair and beats his feet upon the floor in impatience and frustration while Lorry expresses alarm, just having risen from his arm-chair by the fire, and Carton springs to support his old friend and prevent his falling. From his wasted frame, baldness, and white hair one would judge Barnard's Doctor Manette to be a man of eighty. However, since the character was likely born about 1730, being a young physician from Beauvais (about fifty miles north of the metropolis) but recently arrived in Paris in 1757, with a young wife and child, he is probably in his early sixties in this scene.