Dickensians! discussion

Short Reads, led by our members

>

The Drunkard's Death - 7th Summer read (hosted by Janelle)

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Thanks Jean :)

Thanks Jean :)The Drunkards Death was written specifically as the final tale for the second volume of Sketches by Boz published 17th December 1836.

It can be read online here at The Circumlocution Office:

https://www.thecircumlocutionoffice.c...

or here: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Sketch...

This grim story can be described as ‘Drink, destruction and death, a cautionary tale.’

Summary 1

Summary 1Opening : All Londoners would be familiar with men who have succumbed to drunkenness by their abject appearance. The narrator states that some have been degraded by misfortune and misery. But others have wilfully plunged into hopelessness. The story that follows is about one of these men.

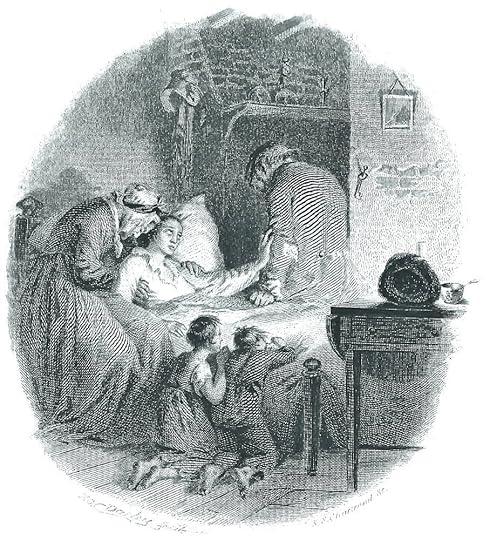

This man once stood beside the bed of his dying wife in a room scantily furnished. An elderly woman holds her dying daughter, while the children kneel around the bed.

The wife gazed at her husband who had been ’summoned from some wild debauch to the bed of sorrow and death’

A watch hung over the mantel-shelf; it’s low ticking was the only sound that broke the profound quiet, but it was a solemn one, for well they knew, who heard it, that before it recorded the passing of another hour, it would beat the knell of a departed spirit.’

When she dies the man sinks into a chair, and none of his crying children approaches to comfort him, all avoided him.

He had been deserted by friends and family, only his wife clung to him in good and evil, in sickness and poverty, and how had he rewarded her? He had reeled from the tavern to her bedside in time to see her die.

He leaves the house and returns to the tavern and keeps drinking. He curses his wife’s family because they’d always said she was too good for him.

It was a merry life while it lasted; and he would make the most of it.

Both Dickens' words and the illustration by Darley are emotionally moving. The wife still is looking at her husband with love although she knows he is a weak man. When his children need him, the father goes back to the tavern to drink away the money that should be used for their care.

Both Dickens' words and the illustration by Darley are emotionally moving. The wife still is looking at her husband with love although she knows he is a weak man. When his children need him, the father goes back to the tavern to drink away the money that should be used for their care.The husband feels all alone in the world, which probably makes him drink more to forget. It's a tragic downward spiral where alcohol is the most important thing in his life.

Yes Connie, Dickens has created a character that’s hard to like from the start yet it’s still very moving and the illustration shows it perfectly.

Yes Connie, Dickens has created a character that’s hard to like from the start yet it’s still very moving and the illustration shows it perfectly.

Summary 2

Summary 2Time passes and the children have grown up. Only his daughter remains with him. His sons have left. He is still a terrible drunk, and by words or blows he gets money for his vice from his hardworking daughter.

One wet December night, he is returning home early around 10pm, he has little money because his daughter has been sick. He buys a small loaf because it’s in his interest to keep his daughter alive. He returns to the slum area where they live (Whitefriars), to the last house in the court and makes his way to the attic. The sickly girl appears at the door, anxious, making sure it’s her father.

She tells him her brother William has returned. The father says he better not want money, meat or drink.

William asks for shelter because he’s in trouble. His father asks ‘robbing, or murdering?’ And William replies yes, and that it shouldn’t surprise him. He tells him his other two sons won’t be bothering him, John has gone to America and Henry is dead.

Dead,’ replied the young man. ‘He died in my arms—shot like a dog, by a gamekeeper. He staggered back, I caught him, and his blood trickled down my hands. It poured out from his side like water. He was weak, and it blinded him, but he threw himself down on his knees, on the grass, and prayed to God, that if his mother was in heaven, He would hear her prayers for pardon for her youngest son. “I was her favourite boy, Will,” he said, “and I am glad to think, now, that when she was dying, though I was a very young child then, and my little heart was almost bursting, I knelt down at the foot of the bed, and thanked God for having made me so fond of her as to have never once done anything to bring the tears into her eyes. O Will, why was she taken away, and father left?” There’s his dying words, father,’ said the young man; ‘make the best you can of ’em. You struck him across the face, in a drunken fit, the morning we ran away; and here’s the end of it.’

The next two days they all remain in the room, on the third evening the girl is quite sick and one of them must leave for food and medicine so the father goes out as night falls. He managed to get some food and money but on his return he passed the public house, he lingers and then succumbs. Two men were watching and his loitering attracted them, and they followed him in. They buy him drinks, until he’s drunk. They trick him by telling him they have booked passage for his son on a boat sailing at midnight.

Back in the room brother and sister wait, finally their father staggers in. The two policemen burst in after him and quickly handcuff William. He curses his father as he’s taken away.

Listen to me, father,’ he said, in a tone that made the drunkard’s flesh creep. ‘My brother’s blood, and mine, is on your head: I never had kind look, or word, or care, from you, and alive or dead, I never will forgive you. Die when you will, or how, I will be with you. I speak as a dead man now, and I warn you, father, that as surely as you must one day stand before your Maker, so surely shall your children be there, hand in hand, to cry for judgment against you.’ He raised his manacled hands in a threatening attitude, fixed his eyes on his shrinking parent, and slowly left the room; and neither father nor sister ever beheld him more, on this side of the grave.

Whitefriars Is an area between Fleet Street and the Thames. It was a monastery until 1540 and later a sanctuary but by the nineteenth century it was a slum area.

Whitefriars Is an area between Fleet Street and the Thames. It was a monastery until 1540 and later a sanctuary but by the nineteenth century it was a slum area.Dickens we can assume knew the area well as he had been working as a journalist at the Morning Chronicle from 1834-36 with its office on Fleet Street.

Link to an article about Dickens early work as an journalist:

https://www.charlesdickenspage.com/ch...

Poaching

PoachingMany of Dickens’ Victorian readers would have been sympathetic to William.

Poaching–the illegal hunting or trapping of wild animals on another person’s property–was not taken seriously as a crime, but the mid nineteenth century saw an increase in the crime after the Game Act of 1831, which made laws surrounding game, particularly birds, stricter, therefore leading to more arrests. Public opinion during this time remained mostly on the sides of the poachers, as even people who did not poach believed that there was nothing inherently wrong with it. The belief that poaching was an innocent crime stemmed from the larger belief that the game laws were made simply to benefit the wealthy.

Quote from this article: https://waterbabiesweb.wordpress.com/...

Policing

PolicingThis is the first appearance of police in a Dickens story and they aren’t Inspector Buckets! But this is the early days of policing in London and the new policemen were still badly paid. It was difficult for the Commissioners to attract respectable men to the role, and there was a very high turnover in the early years of the police force.

Reference: https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/Pol...

Summary 3

Summary 3When Warden awakens next morning he is alone. He searches for his daughter but never finds her.

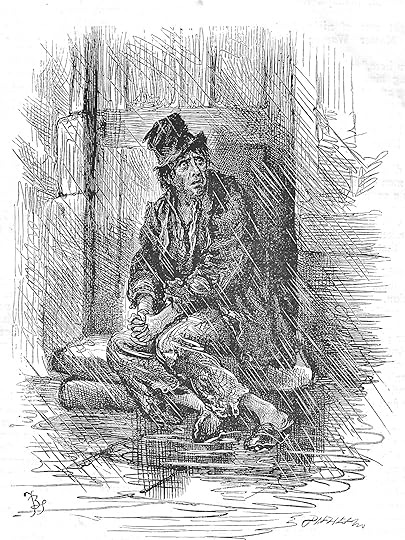

He spends the next year begging, and then drinking, some months in jail, otherwise homeless but always a drunkard.

One stormy night he collapses, he is physically in a bad way and memories from his misspent life overcome him. He remembers he once had a happy home, he remembers his children’s voices. But only for a short while then cold and hunger gnaw at him. He staggers away and tries to sleep in a doorway. His mind is acting strangely like he’s going mad, he hallucinates food and drink. He thinks death is near and there is no one to care or help him.

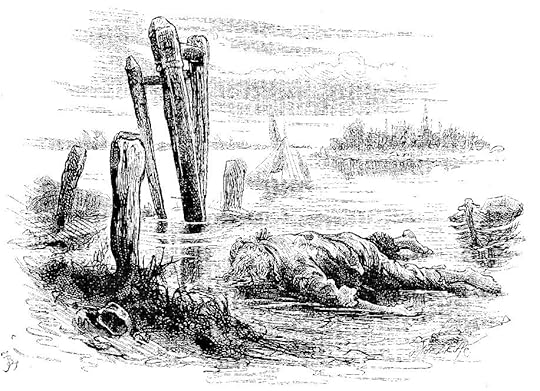

He resolves to make his way to the river, near the stone steps at Waterloo Bridge. He hides as the watch passes by. He sees forms in the water beckoning and at last he leaps into it.

Almost immediately he wants to live! He struggles against the water but the tide takes him away under the bridge, he continues to struggle.

A week afterwards the body was washed ashore, some miles down the river, a swollen and disfigured mass. Unrecognised and unpitied, it was borne to the grave; and there it has long since mouldered away!

The change of heart after jumping into it really tugs at my heart and the fact that the body was just left there and nobody recognised him. The illustrations make it even more pitiful. The man's eyes in the first illustration look so haunted

The change of heart after jumping into it really tugs at my heart and the fact that the body was just left there and nobody recognised him. The illustrations make it even more pitiful. The man's eyes in the first illustration look so haunted

Delirium tremens or commonly known as the drunkard’s madness

Delirium tremens or commonly known as the drunkard’s madness‘First described by the physician Thomas Sutton in Tracts on Delirium Tremens in 1813, delirium tremens, which was commonly known as ‘the drunkard’s madness,’ referred to a set of symptoms directly caused by excessive and/or prolonged use of intoxicating liquors.38 These symptoms included tremors of the limbs, complete sleeplessness, frequent exacerbations of cold, and an incoherent speech with a tremulous voice.39 Describing Master Warden’s descent to madness, Dickens writes that:

He rose, and dragged his feeble limbs a few paces further […] and his tremulous voice was lost in the violence of the storm. Again that heavy chill struck through his frame, and his blood seemed to stagnate beneath it. He coiled himself up in a projecting doorway, and tried to sleep.

But sleep had fled from his dull and glazed eyes. His mind wandered strangely, but he was awake, and conscious […] Hark! A groan! ― another! His senses were leaving him: half-formed and incoherent words burst from his lips […] He was going mad, and he shrieked for help till his voice failed him’ (SB 493, my emphasis).

As we observe from the above extract, Master Warden’s speech is fragmentary and dislocated, and his voice is described as tremulous. We are told that he frequently suffers from ‘cold shiver[s]’ (SB 492) and heavy chills, that he is sleepless and his limbs tremble and are feeble. One of the most defining aspects of delirium tremens, however, was the drunkard’s hallucinations and ‘delusions of sight.’40 As an anonymous writer who claimed to be a ‘medical adviser’ reported: ‘I have known patients fancy they saw devils running round the room, and that they are talking to their friends who have long been dead. In fact, they labour under all kinds of delusions.’41 Similarly, Master Warden experiences both visual and auditory hallucinations. He is haunted, for example, by the apparition of his dead children and by other ‘Strange and fantastic forms’ (SB 494). As Dickens explains:

the forms of his elder children seemed to rise from the grave, and stand about him ― so plain, so clear, and so distinct they were that he could touch and feel them […] voices long since hushed in death sounded in his ears like the music of village bells […] dark gleaming eyes peered from the water, and seemed to mock his hesitation, while hollow murmurs from behind urged him onwards.’

This is from an article called ‘ Dickensian Intemperance: The Representation of the Drunkard in ‘The Drunkard’s Death’ and The Pickwick Papers’ by Kostas Makras. It shows how accurately Dickens describes the symptoms.

Here’s the link: https://19.bbk.ac.uk/article/id/1597/...

It also mentions Gabriel Grub.

The final paragraph sums it up nicely:

From his description of the habitual drunkard in ‘The Drunkard’s Death’ and ‘The Stroller’s Tale’ to the occasional drunken Pickwickians, it is evident that even when Dickens was a ‘very young man’ making his ‘first attempts at authorship [with]…obvious marks of haste and inexperience,’ he was well aware of the harmful effects of alcohol abuse on both mental and bodily health.54 From the beginning of his literary career, Dickens could describe drunkenness and outline its effects, both acute and chronic, with remarkable medical precision. Dickens’s gift for keen observation and descriptive analysis of mental disorders had of course not gone unnoticed by his contemporaries. As an anonymous writer remarked in the British Medical Journal only nine days after Dickens’s death: ‘It must not be forgotten that his descriptions of […] moral and mental insanity in characters too numerous to mention, show the hand of a master.’

Waterloo Bridge

Waterloo BridgeAt the mention of Waterloo bridge Victorian readers would've known what to expect.

This paragraph is from The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London by Judith Flanders

“For, a mere dozen years after Waterloo Bridge opened, it had become a byword for suicides. A political essay as early as 1829 used the bridge as an obvious synonym for suicide without feeling the need for any explanation: ‘The man who loves his country with a sincere affection, unwilling to witness the decline of her prosperity and glory, already hesitates only between pistols and prussic acid, Waterloo-bridge and a running noose.’ In a short story in the late 1830s, Dickens had a drunkard end his life on the bridge. By then, however, it was generally women abandoned by their lovers who were said to kill themselves there: the bridge was known as ‘the English “Bridge of Sighs”...“Lover’s Leap”, the “Arch of Suicide”...a favourite spot for love assignations; and a still more favourite spot for the worn and the weary, who long to cast off the load of existence...To many a poor girl the assignation over one arch...is but a prelude to a fatal leap from another.”

Death scene

Death sceneDickens would write a similar drowning scene in The Old Curiosity Shop 1841

I’ll put it under spoilers.

(view spoiler)

Laura Cort wrote: "The change of heart after jumping into it really tugs at my heart and the fact that the body was just left there and nobody recognised him. The illustrations make it even more pitiful. The man's ey..."

Laura Cort wrote: "The change of heart after jumping into it really tugs at my heart and the fact that the body was just left there and nobody recognised him. The illustrations make it even more pitiful. The man's ey..."I didn’t see your comment, Laura , I was typing the other posts.

Yes, it’s a great detailed illustration isn’t it? The eyes and the hands stand out for me too.

I’ve just read up to the first section. What a despair Dickens has created. The scene is so sad and this man’s behavior is unforgivable. He is selfish not thinking of his children. I can’t see where any good is going to come from the rest of the story.

I’ve just read up to the first section. What a despair Dickens has created. The scene is so sad and this man’s behavior is unforgivable. He is selfish not thinking of his children. I can’t see where any good is going to come from the rest of the story.

No it doesn’t get any cheerier, Lori. It’s unusual for Dickens in that there’s nothing light in it at all, not even a clever character name!

No it doesn’t get any cheerier, Lori. It’s unusual for Dickens in that there’s nothing light in it at all, not even a clever character name!

The article, "Dickensian Intemperance," is excellent, Janelle. Dickens' powers of observation and reading of medical research gave great accuracy to his descriptions of alcoholics. It's interesting that in spite of the temperance movement, alcohol was never outlawed in England. (That's probably a good thing since people were ingesting toxic wood alcohol and other poisonous substances during Prohibition in the US.)

The article, "Dickensian Intemperance," is excellent, Janelle. Dickens' powers of observation and reading of medical research gave great accuracy to his descriptions of alcoholics. It's interesting that in spite of the temperance movement, alcohol was never outlawed in England. (That's probably a good thing since people were ingesting toxic wood alcohol and other poisonous substances during Prohibition in the US.)I

Connie, I’m glad you liked the article :)

Connie, I’m glad you liked the article :)This story reads like something the temperance movement could use, but Dickens in no way would’ve supported that. I assume more people in England liked a drink themselves rather than banning it to get rid of drunkenness!

Ach! I typed a long post, and have just lost it all! :( I'll try to remember the gist ...

Just to say that in 1837 the problem was well established - remember "Gin Alley" in Bleak House and Phiz's illustration for it based on William Hogarth's illustration https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

It was a social problem, partly due to the availability of cheap spirits, and the fact that the water was so incredibly filthy and polluted in London, until the introduction of a sewage system in 1868. We learned about that in in our side read of The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London by Judith Flanders, referenced by Janelle.

I had wondered if the Band of Hope was active yet, but they started up in 1847, 10 years after The Drunkard's Death (I remember doing their exams as a child!) It tended to be the nonconformist low church denominations who promoted temperance. As Janelle said, many people round the country liked a drink - but the Salvation Army was also active - especially in cities.

Interestingly one of the first groups to encourage beer-drinking in London were the Quakers! I believe they had their own distillery. They considered this a better alternative to gin, although now we think of them as teetotallers.

This is a very good article about the Temperance movement in the United Kingdom https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tempera....

Just to say that in 1837 the problem was well established - remember "Gin Alley" in Bleak House and Phiz's illustration for it based on William Hogarth's illustration https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

It was a social problem, partly due to the availability of cheap spirits, and the fact that the water was so incredibly filthy and polluted in London, until the introduction of a sewage system in 1868. We learned about that in in our side read of The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London by Judith Flanders, referenced by Janelle.

I had wondered if the Band of Hope was active yet, but they started up in 1847, 10 years after The Drunkard's Death (I remember doing their exams as a child!) It tended to be the nonconformist low church denominations who promoted temperance. As Janelle said, many people round the country liked a drink - but the Salvation Army was also active - especially in cities.

Interestingly one of the first groups to encourage beer-drinking in London were the Quakers! I believe they had their own distillery. They considered this a better alternative to gin, although now we think of them as teetotallers.

This is a very good article about the Temperance movement in the United Kingdom https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tempera....

Janelle, I had not made the connection that the sons were poaching. But it definitely makes sense when rereading the quote from your second summary - shot like a dog by a gamekeeper. Thanks for that clarification.

Janelle, I had not made the connection that the sons were poaching. But it definitely makes sense when rereading the quote from your second summary - shot like a dog by a gamekeeper. Thanks for that clarification.I’m amazed by the writing so early on -1836. This story is already pinpointing some of the issues that Dickens would promote for the rest of his career. Just from this group’s past reads, I knew what this man was about to do when he went to the river. Knowing the prevalence of suicides in this manner thanks to Jean’s tutelage!

Such a sad story and as you said, no hope or light at all, which I’m glad Dickens would bring into his stories later.

As Lori points out, some of this man's actions are unforgiveable. Yet the reader feels compassion for him. If Dickens wrote this as a cautionary tale, he probably did not want it to have a happy ending. Maybe he wanted any reader heading in the direction of alcoholism to feel that this could happen to them.

As Lori points out, some of this man's actions are unforgiveable. Yet the reader feels compassion for him. If Dickens wrote this as a cautionary tale, he probably did not want it to have a happy ending. Maybe he wanted any reader heading in the direction of alcoholism to feel that this could happen to them.I'm kind of confused about the poaching. Was that all the brothers did? Was poaching a killing/hanging offense?

Katy wrote: ".I’m kind of confused about the poaching. Was that all the brothers did? Was poaching a killing/hanging offence?”

Katy wrote: ".I’m kind of confused about the poaching. Was that all the brothers did? Was poaching a killing/hanging offence?”Katy, Dickens only gives us a couple of lines. As Lori points out when Warden asks William where Henry is, William replies ”Dead,’ replied the young man. ‘He died in my arms—shot like a dog, by a gamekeeper.”

Then in the next paragraph he says ” If I am taken,’ said the young man, ‘I shall be carried back into the country, and hung for that man’s murder.”

So my guess is William has shot the gamekeeper after his brother has been shot either in self defence or revenge.

The image that comes to mind when I think of English gamekeepers is the thugs that work for George Warleggan in Poldark patrolling his estate! It’s set in the previous century though.

The image that comes to mind when I think of English gamekeepers is the thugs that work for George Warleggan in Poldark patrolling his estate! It’s set in the previous century though.Many minor crimes were hanging offences up till 1823. It’s known now as ‘the bloody code’. Often these sentences were commuted to transportation. After 1823 the law was changed.

Reference : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bloody_...

Janelle wrote: "Katy wrote: ".I’m kind of confused about the poaching. Was that all the brothers did? Was poaching a killing/hanging offence?”

Janelle wrote: "Katy wrote: ".I’m kind of confused about the poaching. Was that all the brothers did? Was poaching a killing/hanging offence?”Katy, Dickens only gives us a couple of lines. As Lori points out whe..."

Thanks Janelle. That explanation makes sense.

Absolutely wonderful choice Janelle and thank you for the summary, pictures and additional notes. I loved the writing in the sketch with just a wee bit of sentimentality, and a double helping of vivid death scenes worth of any senational thriller.

Absolutely wonderful choice Janelle and thank you for the summary, pictures and additional notes. I loved the writing in the sketch with just a wee bit of sentimentality, and a double helping of vivid death scenes worth of any senational thriller.Dickens has that Jekyll/Hyde relation to alcohol in his writing and is as comfortable writing of warm and humorous scenes where drunkenness plays a part equally well as the scenes where costs and consequences of abuse are depicted in all their horror. One thing that he especially harsh on is the failure of the abuser to carry out his responsibilities and someone more informed than I would have to explain that seeming obsession with him.

But aside from content, I liked the rhythm of the prose in this. It is very fluid and despite the content relaxes the reader if one voices the words. I quite like it.

Thanks Sam, I’m glad you liked it :)

Thanks Sam, I’m glad you liked it :)Interestingly this piece was the first Dickens text translated into some languages: Hungarian (1838), Polish (1841), Romanian (1844),

and Italian (1845) and probably others (unfortunately I can’t read the full article with this info). So I think the subject matter was relevant across Europe. Although perhaps easier to translate without Dickens humour!

Janelle wrote: "perhaps easier to translate without Dickens humour!..."

That's very astute, Janelle. Before Goodreads I didn't know much about how non-English speaking countries viewed Charles Dickens. So when both Italian and German GR friends said that his language was particularly difficult compared with other Victorian writers, I was surprised. Now I can see it though. It's not so much the vocabulary he uses, but his style: how he employs it. I found summarising a chapter is difficult without sounding flat, and paraphrasing is well nigh impossible if you try to include his sarcasm. You and other members leading reads will probably have found this too :) Nobody does it like Dickens!

I'm also interested to learn the specific countries who translated this first. Is it more relevant to them, perhaps? Does The Drunkard's Death reflect something similar about their social conditions? Or is their literature overly concerned with depressing tales, rather than light-hearted ones? Just something to muse over :)

One particular well-read and popular GR reviewer said a while ago that she had not noticed much humour in Charles Dickens. (I think she's left GR now, to pursue academic studies.) I was speechless! She lives in India, but her English seems excellent, so I found this interesting. Even the most tragic scenes usually have some humour over the page.

That's very astute, Janelle. Before Goodreads I didn't know much about how non-English speaking countries viewed Charles Dickens. So when both Italian and German GR friends said that his language was particularly difficult compared with other Victorian writers, I was surprised. Now I can see it though. It's not so much the vocabulary he uses, but his style: how he employs it. I found summarising a chapter is difficult without sounding flat, and paraphrasing is well nigh impossible if you try to include his sarcasm. You and other members leading reads will probably have found this too :) Nobody does it like Dickens!

I'm also interested to learn the specific countries who translated this first. Is it more relevant to them, perhaps? Does The Drunkard's Death reflect something similar about their social conditions? Or is their literature overly concerned with depressing tales, rather than light-hearted ones? Just something to muse over :)

One particular well-read and popular GR reviewer said a while ago that she had not noticed much humour in Charles Dickens. (I think she's left GR now, to pursue academic studies.) I was speechless! She lives in India, but her English seems excellent, so I found this interesting. Even the most tragic scenes usually have some humour over the page.

Bionic Jean wrote: “I’m also interested to learn the specific countries who translated this first…”

Bionic Jean wrote: “I’m also interested to learn the specific countries who translated this first…”Yes I found it interesting too, Jean, because it seems such an obscure story. When I was looking for info on it, there really isn’t that much out there. Only a few references here and there.

This is the article that talks about the translations. It’s in the Dickens Quarterly :

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/776530/pdf

Form the abstract “ Due to both its thematization of alcohol and literary execution, it was often selected for translation in the 19th century, in some cases being the first work by Dickens to appear in particular countries.”

This one that talks about the Italian translation :

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3738172

Thanks Janelle! I don't have access all of the first one, as I'm not a subscriber, but the abstract is interesting :)

Janelle, thank you for all your work introducing and commentating on this story. Great discussion.

Janelle, thank you for all your work introducing and commentating on this story. Great discussion. I was very interested in the "Dickensian Intemperance" article you linked to - on the face of it, it seems strange that a story like The Stroller's Tale is included in Pickwick Papers with all its lovingly-described social drinking. There are quite a number of scenes where Mr Pickwick and his friends drink huge amounts and it is all presented humorously - Dickens must have felt it was important to present the darker side of drinking as well.

In The Drunkard's Death, it is stated that it is Warden's own fault he has become a drunk, but I don't think the story really feels like that - there is a feeling that he is falling down into a pit of despair and can't do anything to stop the descent.

Thanks Judy :)

Thanks Judy :)I agree with you, although some of Warden’s actions are despicable (his treatment of his daughter for instance), I still felt sorry for him as I was reading.

Thanks Janelle. I think Dickens's views on drunkenness varied over time. At the start of The Drunkard's Death, Dickens talks about respectable tradesmen falling into poverty and shows drink as the cause, although cause and effect are clearly bound up together as a relentless progress.

Thanks Janelle. I think Dickens's views on drunkenness varied over time. At the start of The Drunkard's Death, Dickens talks about respectable tradesmen falling into poverty and shows drink as the cause, although cause and effect are clearly bound up together as a relentless progress. I just remembered reading in one of the biographies that he criticised George Cruikshank for his two series of drawings The Bottle and the Drunkard's Children, published in the 1840s, which showed someone becoming a drunk and then poverty and ruin following.

I found this article about Cruikshank's books and Dickens's views of them on the Victorian Web:

https://victorianweb.org/art/illustra...

Interesting quote from the article:

Dickens thought the opposite — namely, that alcoholism, as Cruikshank depicted it in "The Gin Shop" in Sketches by Boz... stems from poverty and hopelessness rather than the other way round. He commented to his intimate friend and business advisor John Forster that "the drinking should have begun in sorrow, or poverty, or ignorance".

It's the final day for this read, though I'll leave it current for a few days for everyone to finish off, along with our new one which moves here tomorrow (on 31st).

Thank you so much Janelle, for choosing and leading this read so very well, with all the extra info you have found. I wondered what everyone would make of this one. As you have said, it is quite unusual for Charles Dickens. I am grateful that you grasped the nettle, and introduced it to us all. Thank you :)

Thank you so much Janelle, for choosing and leading this read so very well, with all the extra info you have found. I wondered what everyone would make of this one. As you have said, it is quite unusual for Charles Dickens. I am grateful that you grasped the nettle, and introduced it to us all. Thank you :)

Judy wrote: "Thanks Janelle. I think Dickens's views on drunkenness varied over time. At the start of The Drunkard's Death, Dickens talks about respectable tradesmen falling into poverty and shows drink as the ..."

Judy wrote: "Thanks Janelle. I think Dickens's views on drunkenness varied over time. At the start of The Drunkard's Death, Dickens talks about respectable tradesmen falling into poverty and shows drink as the ..."That’s a great link, Judy. I came across some of the illustrations for The Drunkards Children when I was researching Bu didn’t look for Dickens thoughts about them.

Bionic Jean wrote: "It's the final day for this read, though I'll leave it current for a few days for everyone to finish off, along with our new one which moves here tomorrow (on 31st).

Bionic Jean wrote: "It's the final day for this read, though I'll leave it current for a few days for everyone to finish off, along with our new one which moves here tomorrow (on 31st).Thank you so much Janelle, for..."

Thank you, Jean :)

Books mentioned in this topic

The Bottle And The Drunkard's Children (other topics)The Drunkard's Death (other topics)

The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (other topics)

Bleak House (other topics)

The Drunkard's Death (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Charles Dickens (other topics)George Cruikshank (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

Judith Flanders (other topics)

William Hogarth (other topics)

More...

This read is hosted by Janelle