Works of Thomas Hardy discussion

The Mayor of Casterbridge

>

The Mayor of Casterbridge: 5th thread: Chapter 37-45

Welcome to our chapter 37, and our final thread! Without further ado, let's get started

CHAPTER 37

Summary

A royal personage plans to pass through Casterbridge. The town decides to make a fine and welcoming affair of the event, as this royal personage has worked to promote the science of farming on a national level. The council meets to discuss the proceedings. At this meeting, Henchard appears in his shabby clothes and asks to be able to walk with the rest of the council.

Farfrae, now the young Mayor of the town, is the one who must refuse Henchard’s request. Henchard’s interest in walking with the council to greet the royal personage was only a passing fancy, but the opposition, particularly from Farfrae, makes him determined to welcome the visitor.

The day arrives, and all the villagers appear at their best to welcome the visitor. Henchard meets Elizabeth-Jane in the street after he has primed himself with a glass of rum. He tells her that it’s lucky his drinking days have returned or else he would not have the courage to carry out his plan. Elizabeth-Jane is concerned and asks him about his plan, but he says only that he will welcome the royal personage.

Elizabeth-Jane sees Henchard go into a store and reappear with a small union jack flag and a large rosette. She surveys the scene, noting Lucetta seated at the front of the chairs set up for ladies. Lucetta is watching her husband, as he stands with his friends. Henchard stands near her as well. As Lucetta’s eyes pass over him it is clear that she will not acknowledge him in public anymore.

As the royal carriage arrives, a walking procession of the council is formed around it. Suddenly Henchard appears among them and steps directly up to the carriage, reaching out to shake the hand of the royal personage inside. Farfrae grabs Henchard and drags him away from the carriage. For a moment Henchard holds his ground before giving way.

Mrs. Blowbody, a lady sitting next to Lucetta, asks whether Henchard wasn’t once Farfrae’s patron when he first arrived in Casterbridge. Lucetta exclaims that Farfrae could have found his footing in any town without a patron. The townspeople, including Longways, Coney, and Buzzford, recall Farfrae’s humble beginnings and say how greatly he has changed since he sang that night at The King of Prussia. The rest of the royal's visit happens smoothly and after greeting Farfrae and Lucetta, he continues onward.

The townsfolk disperse after the event. Longways, Coney, and Buzzford remain in the street, while many others walk back toward their homes in Mixen Lane. Buzzford mentions the skimmington-ride, which is being planned. As Farfrae has risen to such a prominent position in town, he no longer inspires the interest and sympathy of men like Buzzford, Longways, and Coney, as he once did when he sang at The King of Prussia. These three are less inclined to help Farfrae, but agree to make an inquiry into the matter.

Longways, Coney, and Buzzford would have been surprised to learn of the imminent nature of the plan for a skimmington-ride. At Peter’s Finger, Jopp says to the company that the event will occur that very night, so as to stand in sharp contrast to Farfrae and Lucetta’s prominence that day. For Jopp, the plan is not a joke, but his means of revenge on both the mayor and his wife.

CHAPTER 37

Summary

A royal personage plans to pass through Casterbridge. The town decides to make a fine and welcoming affair of the event, as this royal personage has worked to promote the science of farming on a national level. The council meets to discuss the proceedings. At this meeting, Henchard appears in his shabby clothes and asks to be able to walk with the rest of the council.

Farfrae, now the young Mayor of the town, is the one who must refuse Henchard’s request. Henchard’s interest in walking with the council to greet the royal personage was only a passing fancy, but the opposition, particularly from Farfrae, makes him determined to welcome the visitor.

The day arrives, and all the villagers appear at their best to welcome the visitor. Henchard meets Elizabeth-Jane in the street after he has primed himself with a glass of rum. He tells her that it’s lucky his drinking days have returned or else he would not have the courage to carry out his plan. Elizabeth-Jane is concerned and asks him about his plan, but he says only that he will welcome the royal personage.

Elizabeth-Jane sees Henchard go into a store and reappear with a small union jack flag and a large rosette. She surveys the scene, noting Lucetta seated at the front of the chairs set up for ladies. Lucetta is watching her husband, as he stands with his friends. Henchard stands near her as well. As Lucetta’s eyes pass over him it is clear that she will not acknowledge him in public anymore.

As the royal carriage arrives, a walking procession of the council is formed around it. Suddenly Henchard appears among them and steps directly up to the carriage, reaching out to shake the hand of the royal personage inside. Farfrae grabs Henchard and drags him away from the carriage. For a moment Henchard holds his ground before giving way.

Mrs. Blowbody, a lady sitting next to Lucetta, asks whether Henchard wasn’t once Farfrae’s patron when he first arrived in Casterbridge. Lucetta exclaims that Farfrae could have found his footing in any town without a patron. The townspeople, including Longways, Coney, and Buzzford, recall Farfrae’s humble beginnings and say how greatly he has changed since he sang that night at The King of Prussia. The rest of the royal's visit happens smoothly and after greeting Farfrae and Lucetta, he continues onward.

The townsfolk disperse after the event. Longways, Coney, and Buzzford remain in the street, while many others walk back toward their homes in Mixen Lane. Buzzford mentions the skimmington-ride, which is being planned. As Farfrae has risen to such a prominent position in town, he no longer inspires the interest and sympathy of men like Buzzford, Longways, and Coney, as he once did when he sang at The King of Prussia. These three are less inclined to help Farfrae, but agree to make an inquiry into the matter.

Longways, Coney, and Buzzford would have been surprised to learn of the imminent nature of the plan for a skimmington-ride. At Peter’s Finger, Jopp says to the company that the event will occur that very night, so as to stand in sharp contrast to Farfrae and Lucetta’s prominence that day. For Jopp, the plan is not a joke, but his means of revenge on both the mayor and his wife.

A Little More . . .

The reason Casterbridge wishes to particularly support this royal personage is his commitment to promoting and supporting farming across England, which is Casterbridge’s primary industry.

When Farfrae refuses Henchard’s request, Henchard sees this as a personal affront, rather than realizing that Farfrae’s position as mayor made him the one to have to make the decision. It is consistent with Henchard’s character that he sees this as a challenge and his temper rises to the occasion.

Henchard’s actions seem innocuous: he purchases celebratory and patriotic items like the other villagers. But his costume is embarrassing, shown by Lucetta’s unwillingness to acknowledge him. Henchard has fallen below her notice now that she sees him as no longer a threat, and in her haughtiness, those of lowly backgrounds do not receive her attention.

Henchard being dragged away by Farfrae is a conflict which is both physical and public. Henchard had displayed his physical power, as when he subdues the bull, but here the power is Farfrae’s.

Other villagers have turned against Farfrae now that he is no longer a poor worker. Farfrae’s popularity has dwindled as he has raised himself above the villagers to a position of affluence. The haughtiness of his wife is attaching itself to him as well.

Longways, Coney, and Buzzford discussing the skimmington-ride shows a different class of working man in Casterbridge. They aren’t happy with Farfrae’s social rise, but they find the skimmity morally problematic:

”“’Tis too rough a joke, and apt to wake riots in towns. We know that the Scotchman is a right enough man, and that his lady has been a right enough ’oman since she came here, and if there was anything wrong about her afore, that’s their business, not ours.”

These three men are not among the crowd seen at Peter’s Finger, they are established as middle class, neither poor nor wealthy, and not enthusiastic about siding with either party. They are closer in opinion to what we as readers also think is fair and just.

But the good intentions of these men are probably too late. The skimmington-ride is planned for that night. The skimmington-ride is both a joke and a serious means for revenge. Those who view it as a joke do not stop to consider its consequences.

The reason Casterbridge wishes to particularly support this royal personage is his commitment to promoting and supporting farming across England, which is Casterbridge’s primary industry.

When Farfrae refuses Henchard’s request, Henchard sees this as a personal affront, rather than realizing that Farfrae’s position as mayor made him the one to have to make the decision. It is consistent with Henchard’s character that he sees this as a challenge and his temper rises to the occasion.

Henchard’s actions seem innocuous: he purchases celebratory and patriotic items like the other villagers. But his costume is embarrassing, shown by Lucetta’s unwillingness to acknowledge him. Henchard has fallen below her notice now that she sees him as no longer a threat, and in her haughtiness, those of lowly backgrounds do not receive her attention.

Henchard being dragged away by Farfrae is a conflict which is both physical and public. Henchard had displayed his physical power, as when he subdues the bull, but here the power is Farfrae’s.

Other villagers have turned against Farfrae now that he is no longer a poor worker. Farfrae’s popularity has dwindled as he has raised himself above the villagers to a position of affluence. The haughtiness of his wife is attaching itself to him as well.

Longways, Coney, and Buzzford discussing the skimmington-ride shows a different class of working man in Casterbridge. They aren’t happy with Farfrae’s social rise, but they find the skimmity morally problematic:

”“’Tis too rough a joke, and apt to wake riots in towns. We know that the Scotchman is a right enough man, and that his lady has been a right enough ’oman since she came here, and if there was anything wrong about her afore, that’s their business, not ours.”

These three men are not among the crowd seen at Peter’s Finger, they are established as middle class, neither poor nor wealthy, and not enthusiastic about siding with either party. They are closer in opinion to what we as readers also think is fair and just.

But the good intentions of these men are probably too late. The skimmington-ride is planned for that night. The skimmington-ride is both a joke and a serious means for revenge. Those who view it as a joke do not stop to consider its consequences.

Wonderful thoughts, Bridget!

Wonderful thoughts, Bridget!There is a great parallel between the long and minutious official preparation of the (brief) visit of a Royal Personage to Casterbridge, an event to be savoured very briefly - but that everyone will remember because of Henchard's disturbance, and the clandestine meetings at Peter's Finger concocting the skimmity ride.

This cortège is likely to have more lasting consequences than the Royal procession.

Elizabeth-Jane is back to her role as an observer:

"From the background Elizabeth-Jane watched the scene."

Elizabeth-Jane peeped through the shoulders of those in front, saw what it was, and was terrified; and then her interest in the spectacle as a strange phenomenon got the better of her fear."

Meanwhile, Lucetta is watching only her husband, in a fusional admiration, almost identifying herself with him.

Lucetta "was never tired of watching Donald (...). Every trifling emotion that her husband showed as he talked had its reflex on her face and lips, which moved in little duplicates to his. She was living his part rather than her own, and cared for no one’s situation but Farfrae’s that day."

Once again, the closing lines are keeping us waiting for what is up next.

To [Jopp], at least, it was not a joke, but a retaliation.

And we're back to disliking Henchard. I was feeling all warm and fuzzy about the magnanimity he shows to Lucetta and Farfrae, and he pulls this stunt.

And we're back to disliking Henchard. I was feeling all warm and fuzzy about the magnanimity he shows to Lucetta and Farfrae, and he pulls this stunt. I am having trouble reconciling this action with Henchard's character, as impulsive and volatile as it is. This request defies logic. It is clearly against official protocol and, as the council points out, opens the door for others to demand the same favor. Henchard is a lot of things, but stupid is not one of them, nor is he blind. Up until now, he has appeared to be well aware of how far his star has fallen and how much his appearance has changed from his more prosperous days. How can he possibly think, with everything that has happened, that the current council would condone this? His cryptic "I have a particular reason for wishing to assist at the ceremony" is very intriguing! What is this mysterious reason?

If it wasn't for the words "It had only been a passing fancy of his," I could almost see this as more of an orchestrated attempt to embarrass the town and Farfrae in a moment that will live in infamy--Henchard's performance is that outrageous. Add to that his ambiguous manner in making the request, and it is very suspect! However, Hardy's diction forces me to accept it as a momentary delusion on Henchard's part.

The suspense building to the revelation of Lucetta's scandalous past is almost unbearable!

Cindy Me too. Just when I could see a shaft of light shining from Henchard’s character he pulls this stunt. There must be more to his actions than simply making a fool of himself or embarrassing himself and Elizabeth-Jane as well. But what it is I cannot fathom.

Cindy Me too. Just when I could see a shaft of light shining from Henchard’s character he pulls this stunt. There must be more to his actions than simply making a fool of himself or embarrassing himself and Elizabeth-Jane as well. But what it is I cannot fathom.Perhaps his actions are meant to make the reader even more sympathetic towards Elizabeth-Jane? Perhaps it is to increase the tension of the coming promise that Jopp makes at the end of the chapter.

Jopp is a character to watch, and perhaps even to fear.

Perhaps it is the rum that is driving Henchard's thoughts, but if the shoe was on the other foot, would he have allowed it? It is a very serious chapter because it forecasts what will come and that is not only who Henchard has become but how Lucetta has behaved in her dealings with both men. You are right, Peter, Jopp is indeed the character to watch.

Perhaps it is the rum that is driving Henchard's thoughts, but if the shoe was on the other foot, would he have allowed it? It is a very serious chapter because it forecasts what will come and that is not only who Henchard has become but how Lucetta has behaved in her dealings with both men. You are right, Peter, Jopp is indeed the character to watch.

Farfrae, with Mayoral authority, immediately rose to the occasion. He seized Henchard by the shoulder, dragged him back, and told him roughly to be off. Henchard’s eyes met his, and Farfrae observed the fierce light in them despite his excitement and irritation. For a moment Henchard stood his ground rigidly; then by an unaccountable impulse gave way and retired. Farfrae glanced to the ladies’ gallery, and saw that his Calphurnia’s cheek was pale.

Farfrae, with Mayoral authority, immediately rose to the occasion. He seized Henchard by the shoulder, dragged him back, and told him roughly to be off. Henchard’s eyes met his, and Farfrae observed the fierce light in them despite his excitement and irritation. For a moment Henchard stood his ground rigidly; then by an unaccountable impulse gave way and retired. Farfrae glanced to the ladies’ gallery, and saw that his Calphurnia’s cheek was pale. Calphurnia was a wife of Julius Caesar who is famous for giving him warnings trying to prevent Caesar's assassination. She had received an omen and a prophetic dream, and tried to stop Caesar from meeting with the senate. "Beware the Ides of March!"

Hardy seems to be comparing Lucetta to Calphurnia, and foreshadowing some danger.

Farfrae is active in business and government like Julius Caesar. It leaves us wondering if Henchard is Brutus.

Connie wrote: "Calphurnia was a wife of Julius Caesar who is famous for giving him warnings trying to prevent Caesar's assassination. She had received an omen and a prophetic dream, and tried to stop Caesar from meeting with the senate. "Beware the Ides of March!""

I like the Julius Caesar connection, Connie! I think that really works. And thank you for explaining the Calphurnia reference. I meant to do that, but forgot ;-)

"I am having trouble reconciling this action with Henchard's character, as impulsive and volatile as it is. This request defies logic.

I'm glad you brought this up, Cindy, because it troubles me too. My first thought is what Pamela said, that its the Rum making Henchard act in such a stupefying manner. He did tell Elizabeth that he would lack the courage to act without the pints he consumed.

I wonder too, if this isn't partly the plot of the story becoming unwieldly for Hardy. Many critics have said there is just too much going on in this novel. And Hardy, himself, complained about that.

I like the Julius Caesar connection, Connie! I think that really works. And thank you for explaining the Calphurnia reference. I meant to do that, but forgot ;-)

"I am having trouble reconciling this action with Henchard's character, as impulsive and volatile as it is. This request defies logic.

I'm glad you brought this up, Cindy, because it troubles me too. My first thought is what Pamela said, that its the Rum making Henchard act in such a stupefying manner. He did tell Elizabeth that he would lack the courage to act without the pints he consumed.

I wonder too, if this isn't partly the plot of the story becoming unwieldly for Hardy. Many critics have said there is just too much going on in this novel. And Hardy, himself, complained about that.

Bridget wrote: "I wonder too, if this isn't partly the plot of the story becoming unwieldly for Hardy. Many critics have said there is just too much going on in this novel. And Hardy, himself, complained about that...."

Bridget wrote: "I wonder too, if this isn't partly the plot of the story becoming unwieldly for Hardy. Many critics have said there is just too much going on in this novel. And Hardy, himself, complained about that...."I wanted to express my disquiet but didn't quite have the courage to question Hardy's choices! :) If Hardy himself had reservations, that makes me feel a little better.

Cindy wrote: "I wanted to express my disquiet but didn't quite have the courage to question Hardy's choices! :) If Hardy himself had reservations, that makes me feel a little better..."

:-) I'm so glad it made you feel better!! I think we are really all having the same reaction to this story. And as you said the suspense is increasing. So here we go onto the next chapter. It's a swiftly moving chapter so buckle up :-)

:-) I'm so glad it made you feel better!! I think we are really all having the same reaction to this story. And as you said the suspense is increasing. So here we go onto the next chapter. It's a swiftly moving chapter so buckle up :-)

CHAPTER 38

Summary

After Henchard’s failed greeting of the royal personage, he stood behind the stand where the ladies sat. He overheard Lucetta deny that he had ever helped Farfrae. Returning home, he meets Jopp who says that he too has been snubbed by Lucetta and recounts his story.

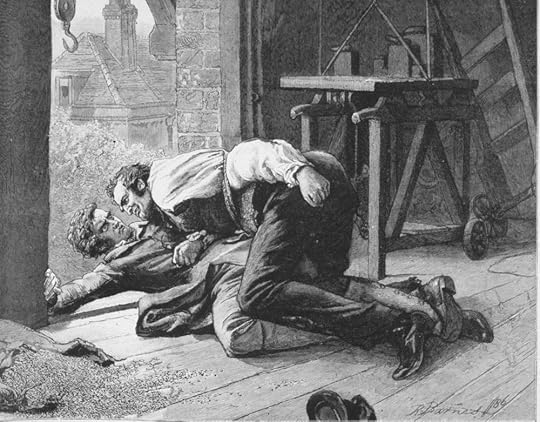

Henchard, without forethought and bent on taking drastic measures, goes looking for Farfrae after supper. He walks to Farfrae’s house where he knocks and leaves the message that he would like to see his employer in the granaries as soon as possible. He goes to the corn stores, which are empty, as no one is working on this celebratory day. He says aloud that he is stronger than Farfrae, and so he takes a rope and ties his left arm down to his side to even the fight. He ascends to the loft, where there is a drop from the edge of thirty or forty feet—the very spot where Elizabeth-Jane once saw him lift his arm, as if to push Farfrae over.

Farfrae arrives, singing the old tune he had once sung at The King of Prussia. Henchard is moved by the song and draws back saying, “No, I can’t do!” Eventually, Henchard calls for him to come up into the loft. Farfrae does and asks Henchard what’s wrong and why he isn’t celebrating like everyone else. Henchard says that they will now face each other man to man.

Henchard says that Farfrae should not have insulted him as he did by bodily dragging him away. Farfrae becomes irritated at this, saying that Henchard had no right to be there and do what he did. Henchard says that they will fight in the loft, and one of them will fall through the door, while the master remains. Immediately, he attacks Farfrae who can only "respond in kind." The wrestling match brings Farfrae close to the door, but Henchard’s tied arm hampers him.

Eventually, Henchard pins Farfrae at the edge, the young man’s head and arm dangling out the door. Henchard gasps that Farfrae’s life is in his hands, and Farfrae responds that he ought to just take it, as he has clearly wished to do for so long. Henchard is moved and exclaims that this is not true, and that he has never cared for any other friend, as he once cared for Farfrae. He says that although he came there to kill Farfrae, he finds he cannot do it, and he releases the younger man.

Farfrae leaves and Henchard sits in the loft for a long time, filled with self-reproach. He says aloud that Farfrae once liked him, but that now he is certain to hate him. He wishes to see Farfrae again that night, but, as he sat in the loft, he heard Farfrae come into the yard for his horse and gig. Abel Whittle brought him a letter and he told Abel that instead of heading to Budmouth, as he had planned, he had been summoned to Weatherby. Realizing that Farfrae won’t return until late, Henchard decides to wait for him. As he waits, he hears a confusion of rhythmic noises, like a band, but his humiliation is too great for anything else to catch his interest.

Summary

After Henchard’s failed greeting of the royal personage, he stood behind the stand where the ladies sat. He overheard Lucetta deny that he had ever helped Farfrae. Returning home, he meets Jopp who says that he too has been snubbed by Lucetta and recounts his story.

Henchard, without forethought and bent on taking drastic measures, goes looking for Farfrae after supper. He walks to Farfrae’s house where he knocks and leaves the message that he would like to see his employer in the granaries as soon as possible. He goes to the corn stores, which are empty, as no one is working on this celebratory day. He says aloud that he is stronger than Farfrae, and so he takes a rope and ties his left arm down to his side to even the fight. He ascends to the loft, where there is a drop from the edge of thirty or forty feet—the very spot where Elizabeth-Jane once saw him lift his arm, as if to push Farfrae over.

Farfrae arrives, singing the old tune he had once sung at The King of Prussia. Henchard is moved by the song and draws back saying, “No, I can’t do!” Eventually, Henchard calls for him to come up into the loft. Farfrae does and asks Henchard what’s wrong and why he isn’t celebrating like everyone else. Henchard says that they will now face each other man to man.

Henchard says that Farfrae should not have insulted him as he did by bodily dragging him away. Farfrae becomes irritated at this, saying that Henchard had no right to be there and do what he did. Henchard says that they will fight in the loft, and one of them will fall through the door, while the master remains. Immediately, he attacks Farfrae who can only "respond in kind." The wrestling match brings Farfrae close to the door, but Henchard’s tied arm hampers him.

Eventually, Henchard pins Farfrae at the edge, the young man’s head and arm dangling out the door. Henchard gasps that Farfrae’s life is in his hands, and Farfrae responds that he ought to just take it, as he has clearly wished to do for so long. Henchard is moved and exclaims that this is not true, and that he has never cared for any other friend, as he once cared for Farfrae. He says that although he came there to kill Farfrae, he finds he cannot do it, and he releases the younger man.

Farfrae leaves and Henchard sits in the loft for a long time, filled with self-reproach. He says aloud that Farfrae once liked him, but that now he is certain to hate him. He wishes to see Farfrae again that night, but, as he sat in the loft, he heard Farfrae come into the yard for his horse and gig. Abel Whittle brought him a letter and he told Abel that instead of heading to Budmouth, as he had planned, he had been summoned to Weatherby. Realizing that Farfrae won’t return until late, Henchard decides to wait for him. As he waits, he hears a confusion of rhythmic noises, like a band, but his humiliation is too great for anything else to catch his interest.

"Now," said Henchard between gasps, "Your life is in my hands." by Robert Barnes, appeared in the London The Graphic, 24 April 1886

A Little More . . .

Overhearing Lucetta’s high opinion of Farfrae and her denial of him is a breaking point for Henchard. To be insulted by Lucetta cuts more deeply than anything else. Jopp tries to commiserate (or perhaps agitate??), but Henchard, as has been demonstrated many times, is focused only on his own suffering.

Henchard’s plan to challenge, and kill, Farfrae occurs directly in the backlash of anger toward Lucetta. This means of destroying Farfrae is more fitting to Henchard’s character than using his secret past with Lucetta. Henchard has demonstrated his physical superiority before. He is not, however, unfair, and he wishes to defeat Farfrae fairly, which is why he ties down his own arm. A physical struggle seems to Henchard like a fair contest, since when they meet hand-to-hand wealth and popularity cannot give Farfrae the advantage. Henchard deliberates in the moment because Farfrae’s song reminds him of their past and their lost friendship.

Farfrae has rarely showed any anger, toward Henchard or any other character in the novel. Farfrae is presented as only able to “respond in kind” in the fight. Henchard is clearly the one who instigated the fight.

This scene is a dramatic climax of the novel: Henchard is moved from a desire to kill Farfrae to unwillingness to do so. His confession of how much he once cared for Farfrae emphasizes how deeply Henchard has been hurt. And while this hurt has often come about through his own doing, it is clear that Henchard has lost all the confidence he once had.

Henchard’s reflection in Farfrae’s loft is one of deep self-hatred and remorse. As with Lucetta and Elizabeth-Jane, Henchard realizes his connection to Farfrae in the moment that he loses him. He hopes to try to patch things up by speaking to Farfrae again, but the reader has already seen the problems with this approach with Lucetta and Elizabeth-Jane. Farfrae leaves for the evening, and only Henchard and Whittle know his change of plans.

Overhearing Lucetta’s high opinion of Farfrae and her denial of him is a breaking point for Henchard. To be insulted by Lucetta cuts more deeply than anything else. Jopp tries to commiserate (or perhaps agitate??), but Henchard, as has been demonstrated many times, is focused only on his own suffering.

Henchard’s plan to challenge, and kill, Farfrae occurs directly in the backlash of anger toward Lucetta. This means of destroying Farfrae is more fitting to Henchard’s character than using his secret past with Lucetta. Henchard has demonstrated his physical superiority before. He is not, however, unfair, and he wishes to defeat Farfrae fairly, which is why he ties down his own arm. A physical struggle seems to Henchard like a fair contest, since when they meet hand-to-hand wealth and popularity cannot give Farfrae the advantage. Henchard deliberates in the moment because Farfrae’s song reminds him of their past and their lost friendship.

Farfrae has rarely showed any anger, toward Henchard or any other character in the novel. Farfrae is presented as only able to “respond in kind” in the fight. Henchard is clearly the one who instigated the fight.

This scene is a dramatic climax of the novel: Henchard is moved from a desire to kill Farfrae to unwillingness to do so. His confession of how much he once cared for Farfrae emphasizes how deeply Henchard has been hurt. And while this hurt has often come about through his own doing, it is clear that Henchard has lost all the confidence he once had.

Henchard’s reflection in Farfrae’s loft is one of deep self-hatred and remorse. As with Lucetta and Elizabeth-Jane, Henchard realizes his connection to Farfrae in the moment that he loses him. He hopes to try to patch things up by speaking to Farfrae again, but the reader has already seen the problems with this approach with Lucetta and Elizabeth-Jane. Farfrae leaves for the evening, and only Henchard and Whittle know his change of plans.

One more thought . . . .

So, Farfrae is not going to Budmouth, but rather Weatherbury and Mellstock. If Mellstock sounded familiar to you, it’s because Hardy uses that fictional town in other stories, particularly in Under the Greenwood Tree where the Mellstock Quire (or choir/musicians) plays an important role.

Mellstock is based on the real town of Stinsford, which is very close to Dorchester (ie: Casterbridge). Hardy’s heart is buried in the Stinsford church.

So, Farfrae is not going to Budmouth, but rather Weatherbury and Mellstock. If Mellstock sounded familiar to you, it’s because Hardy uses that fictional town in other stories, particularly in Under the Greenwood Tree where the Mellstock Quire (or choir/musicians) plays an important role.

Mellstock is based on the real town of Stinsford, which is very close to Dorchester (ie: Casterbridge). Hardy’s heart is buried in the Stinsford church.

And to add to the authenticity, the "royal personage" visiting Casterbridge is based on an actual event.

Although The Mayor of Casterbridge was written during1885-6, Prince Albert visited Dorchester in July 1849, shortly after the period during which this novel is set. That's the most likely reference, particularly since it refer to the route of the railway.

However Thomas Hardy may also have had in mind earlier royal visits too. George III often passed through Dorchester, as he passed his summer months in Weymouth "Budmouth" - which is a busy seaside town even now. George III reigned from 1760-1820, and he made it fashionable. When the bus passes our stop from that direction rather than Bridport (Port-Bredy)'s it is always packed!

Great info and comments Bridget, and everyone. 🙂

Although The Mayor of Casterbridge was written during1885-6, Prince Albert visited Dorchester in July 1849, shortly after the period during which this novel is set. That's the most likely reference, particularly since it refer to the route of the railway.

However Thomas Hardy may also have had in mind earlier royal visits too. George III often passed through Dorchester, as he passed his summer months in Weymouth "Budmouth" - which is a busy seaside town even now. George III reigned from 1760-1820, and he made it fashionable. When the bus passes our stop from that direction rather than Bridport (Port-Bredy)'s it is always packed!

Great info and comments Bridget, and everyone. 🙂

Indeed, Jean!

Indeed, Jean!From the Victorian Web, about The Trumpet-Major, where historical facts (the Napoleonic Wars and more particularly Napoleon's threats upon the southern coast of England) and fiction are skillfully mingled:

"Hardy introduces King George III and his family, who stayed in Weymouth during the Napoleonic Wars, as well as his alleged ancestor Captain Thomas Masterman Hardy (later Vice Admiral), who served under Admiral Horatio Nelson and commanded the HMS Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar."

https://victorianweb.org/authors/hard...

Bridget wrote: "I wonder too, if this isn't partly the plot of the story becoming unwieldly for Hardy. Many critics have said there is just too much going on in this novel. And Hardy, himself, complained about that."

Bridget wrote: "I wonder too, if this isn't partly the plot of the story becoming unwieldly for Hardy. Many critics have said there is just too much going on in this novel. And Hardy, himself, complained about that."I am really beginning to feel this and am glad you mentioned it, Bridget, that the story is getting away from Hardy a little bit.

I'm beginning to tire of the revenge plot, but maybe that's because it doesn't seem to suit or work out very well for Henchard! I had to laugh a little at him putting one arm behind his back before he tries to kill Farfrae. Since if he followed-through, no one else would appreciate this chivalrous act, I'm thinking it shows Henchard really is the gentleman of the title. At this point I'm feeling sorry for him. He wants to be a bad guy but he just can't!

Someone - Bridget ? - said that Jopp agitated Henchard's grudge against Lucetta and Farfrae when he told him about his encounter with Lucetta.

Someone - Bridget ? - said that Jopp agitated Henchard's grudge against Lucetta and Farfrae when he told him about his encounter with Lucetta.From being a latent threat when his gaze follows Henchard and another time Lucetta, Jopp becomes, unplanned, because of a chain of coincidences (the letters read at Peter's Finger), the concrete instrument of Henchard's revenge on Lucetta and Farfrae.

Beyond this, Michael Henchard is accommodated in a cottage by Jopp, which may seem paradoxical at first, but makes perfect sense when Jopp appears recurrently through the whole novel, symbolically and persistently as an inner enemy, the embodiment of Henchard's own anger, impulsiveness, and arbitrariness.

Despite the risk of sounding like a broken record, I feel that Henchard's cohabitation with Jopp has an interesting resemblance to a similar situation in Les Misérables:(view spoiler)

The Henchard-Farfrae fight was most curious to me. Yes, I realize that Farfrae had humiliated Henchard earlier in the day and I do realize that Farfrae has taken everything from Henchard but somehow the fight just does not sit comfortably in my mind. The fight does, once again, demonstrate that Henchard’s mind has a terminal point. He cannot take a final step to harm Farfrae or Lucetta. Some moral imperative always clicks into place. I just can’t get a good grasp on his mind or character.

The Henchard-Farfrae fight was most curious to me. Yes, I realize that Farfrae had humiliated Henchard earlier in the day and I do realize that Farfrae has taken everything from Henchard but somehow the fight just does not sit comfortably in my mind. The fight does, once again, demonstrate that Henchard’s mind has a terminal point. He cannot take a final step to harm Farfrae or Lucetta. Some moral imperative always clicks into place. I just can’t get a good grasp on his mind or character.Surely Hardy must have exhausted the storyline of the Henchard, Lucetta, Farfrae and Elizabeth-Jane quartet. Where can Hardy go? My mind goes back to the stranger who entered the town a couple of days ago. There are subtle hints given as to who it could be. Interesting that once this stranger entered town Hardy left that plot strand and fell back/forward (?) into our ongoing drama. Was this a pause to increase suspense or another reason?

One core trope of literature is the story of a person who leaves their home to enter the world (Bildungsroman-type novels.) The second trope is the stranger who arrives in town and ignites a story around their mysterious presence. We shall see …

Bionic Jean wrote: "And to add to the authenticity, the "royal personage" visiting Casterbridge is based on an actual event.

Although The Mayor of Casterbridge was written during1885-6, Prince Albert vis..."

Thank you so much Jean and Claudia for adding the information about the "real life" visits of the royals through Dorset. I love seeing how Hardy took real life events and turned them into Wessex lore.

Hardy wrote a preface to TMOC in 1895 where he talks about the incidents of the story arising out of three events that occurred in and around Dorchester "at or about the intervals of time" that we've read.

"They were the sale of a wife by her husband, the uncertain harvests which immediately preceded the repeal of the Corn Laws**, and the visit of a Royal personalge"

So it seems Hardy always had in mind that a Royal would visit Casterbridge. I can imagine what a huge event it would be for a small rural town to receive Royalty.

**As I understand it, repealing the Corn Laws removed tariffs and allowed for the import of grains into England once again. So that when England had bad harvests, the people could still by decent grains at a reasonable price. But please do correct me if I've got that wrong. Bad harvests have played a huge role in TMOC.

"

Although The Mayor of Casterbridge was written during1885-6, Prince Albert vis..."

Thank you so much Jean and Claudia for adding the information about the "real life" visits of the royals through Dorset. I love seeing how Hardy took real life events and turned them into Wessex lore.

Hardy wrote a preface to TMOC in 1895 where he talks about the incidents of the story arising out of three events that occurred in and around Dorchester "at or about the intervals of time" that we've read.

"They were the sale of a wife by her husband, the uncertain harvests which immediately preceded the repeal of the Corn Laws**, and the visit of a Royal personalge"

So it seems Hardy always had in mind that a Royal would visit Casterbridge. I can imagine what a huge event it would be for a small rural town to receive Royalty.

**As I understand it, repealing the Corn Laws removed tariffs and allowed for the import of grains into England once again. So that when England had bad harvests, the people could still by decent grains at a reasonable price. But please do correct me if I've got that wrong. Bad harvests have played a huge role in TMOC.

"

"alleged ancestor" is right, Claudia!

I'm afraid the Victorian Web is being a little fanciful here - as was the ambitious Thomas Hardy himself.

They were not directly related, although they shared the same last name and both hailed from Dorset. Admiral Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy, who served with Nelson, and Thomas Hardy, were two distinct individuals. "Our Tom" used to boast a little about how he was was proud to acknowledge a distant family connection to the admiral, but they were not close relatives, according to Portesham Village Hall.

There is a monument to Admiral Hardy just up the coast road from here, and it is referred to as "Hardy's Monument".

It's amazing how many people assume it commemorates the novelist - but it is nothing to do with him! 😆.

I'm afraid the Victorian Web is being a little fanciful here - as was the ambitious Thomas Hardy himself.

They were not directly related, although they shared the same last name and both hailed from Dorset. Admiral Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy, who served with Nelson, and Thomas Hardy, were two distinct individuals. "Our Tom" used to boast a little about how he was was proud to acknowledge a distant family connection to the admiral, but they were not close relatives, according to Portesham Village Hall.

There is a monument to Admiral Hardy just up the coast road from here, and it is referred to as "Hardy's Monument".

It's amazing how many people assume it commemorates the novelist - but it is nothing to do with him! 😆.

Kathleen wrote: "I'm beginning to tire of the revenge plot, but maybe that's because it doesn't seem to suit or work out very well for Henchard! I had to laugh a little at him putting one arm behind his back before he tries to kill Farfrae. Since if he followed-through, no one else would appreciate this chivalrous act."

Kathleen - wonderful point, that if Henchard killed Farfrae no one would care that he had one arm tied down.

It reminds me that Henchard is an uneducated, self made, simple man. Remember at the beginning of the story he wasn't good with the science and the math of his business. That's why he needed a manager. All of Henchard's strength is physical (remember him fighting the bull). That is a wicked combination for a man with a temper. It's becoming more wicked as his drinking starts up again.

As Peter says, "Some moral imperative always clicks into place. I just can’t get a good grasp on his mind or character." And I agree with this. Henchard is impulsive, and I never quite know if the bull or lamb is going to show up.

Kathleen - wonderful point, that if Henchard killed Farfrae no one would care that he had one arm tied down.

It reminds me that Henchard is an uneducated, self made, simple man. Remember at the beginning of the story he wasn't good with the science and the math of his business. That's why he needed a manager. All of Henchard's strength is physical (remember him fighting the bull). That is a wicked combination for a man with a temper. It's becoming more wicked as his drinking starts up again.

As Peter says, "Some moral imperative always clicks into place. I just can’t get a good grasp on his mind or character." And I agree with this. Henchard is impulsive, and I never quite know if the bull or lamb is going to show up.

Bionic Jean wrote: ""alleged ancestor" is right, Claudia!

I'm afraid the Victorian Web is being a little fanciful here - as was the ambitious Thomas Hardy himself.

They were not directly related, alth..."

Beautiful picture Jean! I'm sure I would assume the monument was related to the author Thomas Hardy, if you hadn't told us!

I'm afraid the Victorian Web is being a little fanciful here - as was the ambitious Thomas Hardy himself.

They were not directly related, alth..."

Beautiful picture Jean! I'm sure I would assume the monument was related to the author Thomas Hardy, if you hadn't told us!

Peter wrote: "The fight does, once again, demonstrate that Henchard’s mind has a terminal point. He cannot take a final step to harm Farfrae or Lucetta. Some moral imperative always clicks into place. I just can’t get a good grasp on his mind or character...."

Peter wrote: "The fight does, once again, demonstrate that Henchard’s mind has a terminal point. He cannot take a final step to harm Farfrae or Lucetta. Some moral imperative always clicks into place. I just can’t get a good grasp on his mind or character...."You're right, Peter. How many times has it been now that Henchard has his "enemies" in his sights and takes his finger off the trigger? How many more times will it happen? At some point, you want your character to grow enough to learn something from their experiences. Hopefully, this time has made enough of an impression to convince Henchard that despite his anger at the trajectory his life has taken and the roles of Lucetta and Farfrae in that journey, he is not able to deliberately hurt them or destroy them emotionally. Maybe he will start seeking inner peace and healing for the wounds dealt by fate. Not that I think they're all going to link hands and sing "Kumbayah" at this point! Someone is going to do SOMETHING to create chaos, and my money is on Jopp. I just think this particular pattern of behavior by Henchard is played out.

This chapter just seems to not ring true to me. Perhaps as others have said, I'm getting tired of the revenge plot with Henchard always playing the fool. I can't believe that Farfae doesn't have emphathy with what Henchard is going through.

This chapter just seems to not ring true to me. Perhaps as others have said, I'm getting tired of the revenge plot with Henchard always playing the fool. I can't believe that Farfae doesn't have emphathy with what Henchard is going through. Wouldn't it have been better to show kindness to an old friend, to go to him and admit its only because of what Henchard offered Farfae, that he was able to succeed and grow? Maybe I'm putting too much on Farfae's shoulders but I would have expected more from him. He could have offered more to Henchard yet doesn't (and he also doesn't know yet how much Henchard's grievances extend).

I'm frankly not quite sure how Hardy is going to pull all the threads in this tale together for a successful ending. Where does he take these main characters as well as Elizabeth-Jane (who seems to have the biggest forgiving heart, maturity and practical head of them all.

Bridget - the detailed post about the Corn Laws is LINK HERE.

There were quite a few reasons and factors involved in repealing them.

There were quite a few reasons and factors involved in repealing them.

I think Henchard binding his arm behind his back so as to not have any advantage is so poignant. As Kathleen says, he just can't bring himself to be a thoroughly bad man. In fact in this chapter he seems profoundly moral to me. He can't bear Farfae peevishly accusing him of wanting to kill him often enough, and is so aghast at the idea, that it takes all the wind out of his sails. I'm not liking Farfrae much at the moment. He does not have much depth of feeling, and as we have said, seems oblivious to so much.

The chapter ends so ominously, with the apparent sounds of celebration. Henchard has no idea what it might be - but we do! And it was funded by a stranger who wanted to help with a quaint custom ... and then mysteriously disappeared. Was that just because (as we were told) he felt the company beneath him, or might we perhaps meet him again?

The chapter ends so ominously, with the apparent sounds of celebration. Henchard has no idea what it might be - but we do! And it was funded by a stranger who wanted to help with a quaint custom ... and then mysteriously disappeared. Was that just because (as we were told) he felt the company beneath him, or might we perhaps meet him again?

Bionic Jean wrote: "The chapter ends so ominously, with the apparent sounds of celebration. Henchard has no idea what it might be - but we do!

The chapter certainly ends ominously as Jean so aptly put it. Farfrae has left town. Henchard seems frozen on the bridge staring at the river below. He's steeped in his shame so much that he can't move, and meanwhile the skimmington-ride has begun. Where is Elizabeth in all of this? What will happen now to Lucetta - who is all alone? Well, lets find out :-)

The chapter certainly ends ominously as Jean so aptly put it. Farfrae has left town. Henchard seems frozen on the bridge staring at the river below. He's steeped in his shame so much that he can't move, and meanwhile the skimmington-ride has begun. Where is Elizabeth in all of this? What will happen now to Lucetta - who is all alone? Well, lets find out :-)

CHAPTER 39

Summary

After his fight with Henchard, Farfrae still wants to drive to Budmouth, until the letter requesting that he go to Weatherby reroutes him. Farfrae wishes to think over the situation with Henchard, and to not encounter Lucetta or act without thought.

The note about his business in Weatherby is an attempt by Longways, Coney, and Buzzford to remove him from Casterbridge for the evening, should the skimmington-ride take place. They won't warn Farfrae directly fearing backlash from friends and neighbors. They also take no precautions on Lucetta’s behalf, believing some truth in the scandal, and feeling she ought to endure the proceedings.

At about eight o’clock, Lucetta is happily sitting in her drawing room when she overhears a distant hubbub. This doesn't surprise or interest her, given the celebratory nature of the day, until she hears a maid from an upstairs window talking across the street to a maid in another window. The maids can see the figures of a man and a woman, tied back-to-back, riding on a donkey, and surrounded by a crowd of people.

One maid exclaims that the female figure is dressed exactly as Lucetta was dressed when she sat in the front row for a performance at the Town Hall. Lucetta hurries to the window, just as Elizabeth enters. Elizabeth attempts to close the window and curtains, but Lucetta tells her to let it be. Lucetta realizes that the two figures are effigies of herself and Henchard, and Elizabeth’s look betrays that she already knew this to be the truth.

Elizabeth attempts again to shut the window. Lucetta shrieks that Farfrae will see it and never love her again, which will kill her. Lucetta is determined to see it and rushes out onto the balcony. In the lights surrounding the two figures there is no mistaking whom they are meant to represent. Lucetta collapses and lies on the floor in a seizure.

Elizabeth rings for the servants, but they have all run out of the house to see what is happening. Eventually, the servants reappear. The doctor is called and Lucetta is carried to her bed. The doctor arrives and says Lucetta’s fit is serious, in her condition (which means she is pregnant), and Farfrae must be sent for immediately. They mistakenly believe that Farfrae has taken the road toward Budmouth, and a man is dispatched to find him.

Mr. Grower (a burgess) sees the proceedings and calls the Constable. The two look for backup to confront the crowd leading the skimmington-ride, and meet up with Mr. Blowbody (a magistrate). But when they split up to find the crowd, it has disbanded and the perpetrators cannot be found. Mr. Grower speaks to Charl, Joe, and Jopp, but they claim they haven’t seen anything.

Mr. Grower and Constable Stubberd organize a group to go into Mixen Lane in search of information. In Peter’s Finger they speak again to Charl, asking if they just saw him, but he claims to have been at Peter’s Finger for the last hour, which Nance Mockridge confirms. No incriminating evidence or information can be drawn from the Peter’s Finger crowd and the investigators leave.

Summary

After his fight with Henchard, Farfrae still wants to drive to Budmouth, until the letter requesting that he go to Weatherby reroutes him. Farfrae wishes to think over the situation with Henchard, and to not encounter Lucetta or act without thought.

The note about his business in Weatherby is an attempt by Longways, Coney, and Buzzford to remove him from Casterbridge for the evening, should the skimmington-ride take place. They won't warn Farfrae directly fearing backlash from friends and neighbors. They also take no precautions on Lucetta’s behalf, believing some truth in the scandal, and feeling she ought to endure the proceedings.

At about eight o’clock, Lucetta is happily sitting in her drawing room when she overhears a distant hubbub. This doesn't surprise or interest her, given the celebratory nature of the day, until she hears a maid from an upstairs window talking across the street to a maid in another window. The maids can see the figures of a man and a woman, tied back-to-back, riding on a donkey, and surrounded by a crowd of people.

One maid exclaims that the female figure is dressed exactly as Lucetta was dressed when she sat in the front row for a performance at the Town Hall. Lucetta hurries to the window, just as Elizabeth enters. Elizabeth attempts to close the window and curtains, but Lucetta tells her to let it be. Lucetta realizes that the two figures are effigies of herself and Henchard, and Elizabeth’s look betrays that she already knew this to be the truth.

Elizabeth attempts again to shut the window. Lucetta shrieks that Farfrae will see it and never love her again, which will kill her. Lucetta is determined to see it and rushes out onto the balcony. In the lights surrounding the two figures there is no mistaking whom they are meant to represent. Lucetta collapses and lies on the floor in a seizure.

Elizabeth rings for the servants, but they have all run out of the house to see what is happening. Eventually, the servants reappear. The doctor is called and Lucetta is carried to her bed. The doctor arrives and says Lucetta’s fit is serious, in her condition (which means she is pregnant), and Farfrae must be sent for immediately. They mistakenly believe that Farfrae has taken the road toward Budmouth, and a man is dispatched to find him.

Mr. Grower (a burgess) sees the proceedings and calls the Constable. The two look for backup to confront the crowd leading the skimmington-ride, and meet up with Mr. Blowbody (a magistrate). But when they split up to find the crowd, it has disbanded and the perpetrators cannot be found. Mr. Grower speaks to Charl, Joe, and Jopp, but they claim they haven’t seen anything.

Mr. Grower and Constable Stubberd organize a group to go into Mixen Lane in search of information. In Peter’s Finger they speak again to Charl, asking if they just saw him, but he claims to have been at Peter’s Finger for the last hour, which Nance Mockridge confirms. No incriminating evidence or information can be drawn from the Peter’s Finger crowd and the investigators leave.

We have another excellent illustration by Robert Barnes for this chapter. He chose to capture the moment Lucetta sees the effigies in the skimmington ride.

Lucetta's eyes were straight upon the spectacle of the uncanny revel.

Published 1 May 1886 (Part Eighteen), The Victorian Web, copied by Philip Allingham

Lucetta's eyes were straight upon the spectacle of the uncanny revel.

Published 1 May 1886 (Part Eighteen), The Victorian Web, copied by Philip Allingham

A Little More . . .

Farfrae’s wish to give the situation with Henchard thought reflects his fundamental difference from Henchard as a man of premeditation and planning rather than a man of spontaneous decisions.

The villagers are particularly cruel-hearted about scandal, allowing Lucetta, who they are suspicious of, to suffer through the skimmington-ride. Lucetta learns of the skimmington-ride through the gossip of the maids. Once again, a character learns of an event through the gossip of others. If not for this gossip, Lucetta may not have witnessed it at all. Elizabeth attempts to prevent Lucetta from seeing the spectacle and she is not relieved to see the truth come to life. Nor does she feel Lucetta is “getting what she deserved.”

When Lucetta fully realizes who the effigies portray, her first thought is of Farfrae and how he will never love her again and then she collapses. Lucetta’s emotional distress is clear and acute. Lucetta’s sickness appears to be life threatening, both for her and her baby.

The villagers who are not a part of the skimmington-ride and who attempt to disband it are all upper class. Mr. Grower we have met as he witnessed the Farfrae’s marriage and was one of Henchard’s creditors. Mr. Blowbody is Mrs. Blowbody’s husband, who we met at the Royalty viewing as a friend of Lucetta’s. This emphasizes the economic and class divide of the town.

Despite the attempt to catch the perpetrators of the skimmington-ride, these people escape. When Mr. Grower and Constable Stubberd confront Charl twice, he outsmarts them, by denying his presence in town, with the support of Nance Mockridge. This reinforces how the upper class don’t really pay attention to the lower class people they encounter. The fact that they easily believe Charl’s story that he wasn’t who they met, is because for the upper classes, all the people of low class look the same. The Mixen Lane inhabitants stick together and help each other.

Farfrae’s wish to give the situation with Henchard thought reflects his fundamental difference from Henchard as a man of premeditation and planning rather than a man of spontaneous decisions.

The villagers are particularly cruel-hearted about scandal, allowing Lucetta, who they are suspicious of, to suffer through the skimmington-ride. Lucetta learns of the skimmington-ride through the gossip of the maids. Once again, a character learns of an event through the gossip of others. If not for this gossip, Lucetta may not have witnessed it at all. Elizabeth attempts to prevent Lucetta from seeing the spectacle and she is not relieved to see the truth come to life. Nor does she feel Lucetta is “getting what she deserved.”

When Lucetta fully realizes who the effigies portray, her first thought is of Farfrae and how he will never love her again and then she collapses. Lucetta’s emotional distress is clear and acute. Lucetta’s sickness appears to be life threatening, both for her and her baby.

The villagers who are not a part of the skimmington-ride and who attempt to disband it are all upper class. Mr. Grower we have met as he witnessed the Farfrae’s marriage and was one of Henchard’s creditors. Mr. Blowbody is Mrs. Blowbody’s husband, who we met at the Royalty viewing as a friend of Lucetta’s. This emphasizes the economic and class divide of the town.

Despite the attempt to catch the perpetrators of the skimmington-ride, these people escape. When Mr. Grower and Constable Stubberd confront Charl twice, he outsmarts them, by denying his presence in town, with the support of Nance Mockridge. This reinforces how the upper class don’t really pay attention to the lower class people they encounter. The fact that they easily believe Charl’s story that he wasn’t who they met, is because for the upper classes, all the people of low class look the same. The Mixen Lane inhabitants stick together and help each other.

Definition some Humor

When Mr. Grower finally finds the constables who have gone into hiding, their excuse for hiding is "What can we two lammigers do against such a multitude", but then they also claim

'Tis tempting 'em to commit felo de se upon us.

For those of you wondering what "felo de se" meant, I did too and I looked it up. Its from Medieval Latin - "felon of him/herself". It was a concept applied against the personal estates (assets) of adults who ended their own lives. Early English common law, considered suicide a crime—a person found guilty of it, though dead, would ordinarily see penalties including forfeiture of property to the monarch and a shameful burial. Beginning in the seventeenth century precedent and coroners' custom gradually deemed suicide temporary insanity—court-pronounced conviction and penalty to heirs were gradually phased out.

Which didn't really make sense given the constables weren't suicidal, they were worried about the mob killing them. But I think what the constables are intimating here is that being overrun by this mob would lead to a shameful death for them, and bring shame to their families. At least that's what I deduced. I'm not at all certain I'm correct. I would love to hear all of your thoughts :-)

Whatever the meaning, I found the constables funny. As Peter said the other day, there hasn't been as much humor in this novel. But here, I was happy to find some humorous relief.

Over to you . . . .Tomorrow is a FREE day. We will resume with Chapter 40 on Friday

**Also, in case you like to plan ahead, over the next week we will be deviating slightly from our pattern of read three chapters and have a free day. Here is the schedule through August 18th

Thurs Aug 14 - FREE

Fri Aug 15 - ch 40

Sat Aug 16 - ch 41

Sun Aug 17 - FREE *

Mon Aub 18 - POEM - Before My Friend Arrived (led by Connie)

When Mr. Grower finally finds the constables who have gone into hiding, their excuse for hiding is "What can we two lammigers do against such a multitude", but then they also claim

'Tis tempting 'em to commit felo de se upon us.

For those of you wondering what "felo de se" meant, I did too and I looked it up. Its from Medieval Latin - "felon of him/herself". It was a concept applied against the personal estates (assets) of adults who ended their own lives. Early English common law, considered suicide a crime—a person found guilty of it, though dead, would ordinarily see penalties including forfeiture of property to the monarch and a shameful burial. Beginning in the seventeenth century precedent and coroners' custom gradually deemed suicide temporary insanity—court-pronounced conviction and penalty to heirs were gradually phased out.

Which didn't really make sense given the constables weren't suicidal, they were worried about the mob killing them. But I think what the constables are intimating here is that being overrun by this mob would lead to a shameful death for them, and bring shame to their families. At least that's what I deduced. I'm not at all certain I'm correct. I would love to hear all of your thoughts :-)

Whatever the meaning, I found the constables funny. As Peter said the other day, there hasn't been as much humor in this novel. But here, I was happy to find some humorous relief.

Over to you . . . .Tomorrow is a FREE day. We will resume with Chapter 40 on Friday

**Also, in case you like to plan ahead, over the next week we will be deviating slightly from our pattern of read three chapters and have a free day. Here is the schedule through August 18th

Thurs Aug 14 - FREE

Fri Aug 15 - ch 40

Sat Aug 16 - ch 41

Sun Aug 17 - FREE *

Mon Aub 18 - POEM - Before My Friend Arrived (led by Connie)

Bridget wrote: "We have another excellent illustration by Robert Barnes for this chapter. He chose to capture the moment Lucetta sees the effigies in the skimmington ride.

Bridget wrote: "We have another excellent illustration by Robert Barnes for this chapter. He chose to capture the moment Lucetta sees the effigies in the skimmington ride.Lucetta's eyes were straight upon the..."

Yes, this illustration is very interesting, both for itself and for the previous illustration that depicted Henchard and Farfrae grappling in the barn. If we put the illustrations side by side I think we would appreciate the Illustrations by Barnes even more.

In many ways these two illustrations mirror and reflect upon each other. First, both of Barnes’ illustrations show the characters in an elevated location. From such a position all the characters are raised above the ground. I think this is important as it places the characters in a superior position to the ground. While possibly an insignificant detail it does subliminally heighten the stature of the characters.

The barn confrontation occurs between the men. In the left foreground we see a bag of wheat broken open. This bag symbolizes the broken friendship of Henchard and Farfrae. Their friendship began with Farfrae helping Henchard resolve a problem with his infected crop. Now, it is not only a crop that is infected but their friendship is over. When we see the illustration Henchard and Farfrae are grappling on the floor of the loft. The loft is open to the outside and the elements. It is now Farfrae who is in danger of losing his life, whereas when we first saw these two men it was Henchard who was in danger of losing his money, his livelihood, perhaps even his reputation for selling compromised grain.

In the Barnes illustration of this chapter we see two women by an open window. Elizabeth-Jane has a hold on Lucetta and is also grappling with her. This time, however, Elizabeth-Janet’s hold is not to inflict pain or to threaten Lucetta’s life. Rather, in this illustration Elizabeth-Jane is trying to prevent Lucetta from experiencing humiliation and pain. Unlike the first illustration where the men were grappling on the floor, here we see the women in a standing pose. Soon after, Lucetta does fall to the floor. Elizabeth-Jane follows Lucetta in an effort to comfort her, not to inflict any sort of discomfort.

What is also important to note, I think, is who the characters in these illustrations are. Elizabeth-Jane is Henchard's step-daughter. Unlike Henchard, she is attempting to provide comfort, not pain — or even death — to Lucetta. Lucetta is Farfrae’s wife. Thus we have two men who are at serious odds with one another attempting to harm the other. We have in this illustration two women, both intimately linked to the two fighting men, embracing in an attempt to find comfort within each other’s arms.

In the two illustrations we can see the power of an illustration to offer in another medium the plot of the story. Quite remarkable insight and work by Barnes.

Bridget wrote: "Definition some Humor

Bridget wrote: "Definition some HumorWhen Mr. Grower finally finds the constables who have gone into hiding, their excuse for hiding is "What can we two lammigers do against such a multitude", but then they also..."

Yes Bridget the constables were funny. A long wait for a silent chuckle.

The chapter begins with Lucetta feeling very content. The day’s success, we are told, put her in ‘a more hopeful mood than she had enjoyed since her marriage’. And then the cacophony of sound is heard (much unlike her husband’s habit of singing to her ) and her world collapses. Her husband has been lured out of town and she can only find comfort in the arms and in the initial care of Elizabeth-Jane. The irony. Elizabeth-Jane was once hopeful of a courtship and marriage to Farfrae.

I thought Hardy did a masterful job of explaining how the Skimmington-ride participants dissolved into the night. I had another chuckle when the reason for why a tambourine was in an oven was given.

I agree Claudia - it's not often I laugh aloud when reading Thomas Hardy - but I did with the "cowardly constables"! And the quick-thinking landlady with her quip about why the tambourine was on the oven, was priceless! 😂

It's quite an achievement to have a chapter filled with tension, drama and passion as well as humour, but that's what we have here.

I enjoyed learning about the villagers, and that one or two "rustics" were more empathic and kindhearted (e.g. Solomon Longways, who sent the anonymous letter to Farfrae) rather than being out for a cruel laugh at someone else's expense (e.g. Nance Mockridge the leader of the skimmington plan and Mother Cuxsom).

However it's noticeable that they all thought Lucetta deserved what she got:

"For poor Lucetta they took no protective measure, believing with the majority there was some truth in the scandal, which she would have to bear as she best might."

It's a very different attitude for the woman involved than it would have been for a 19th century man "sowing his wild oats". I think there might have been envy here too, as she has no qualms about displaying her wealth.

Lucetta's behaviour seems to fit the description of 19th century "female hysteria", but we are told she:

"remained convulsed on the carpet in the paroxysms of an epileptic seizure."

The fact that "as soon as she remembered what had passed the fit returned" puzzled me. Can this happen with a type of epilepsy? Ah, but it rang a great bell when the doctor said:

"a fit in the present state of her health means mischief."

Could this be a coded message? 🤔

It's quite an achievement to have a chapter filled with tension, drama and passion as well as humour, but that's what we have here.

I enjoyed learning about the villagers, and that one or two "rustics" were more empathic and kindhearted (e.g. Solomon Longways, who sent the anonymous letter to Farfrae) rather than being out for a cruel laugh at someone else's expense (e.g. Nance Mockridge the leader of the skimmington plan and Mother Cuxsom).

However it's noticeable that they all thought Lucetta deserved what she got:

"For poor Lucetta they took no protective measure, believing with the majority there was some truth in the scandal, which she would have to bear as she best might."

It's a very different attitude for the woman involved than it would have been for a 19th century man "sowing his wild oats". I think there might have been envy here too, as she has no qualms about displaying her wealth.

Lucetta's behaviour seems to fit the description of 19th century "female hysteria", but we are told she:

"remained convulsed on the carpet in the paroxysms of an epileptic seizure."

The fact that "as soon as she remembered what had passed the fit returned" puzzled me. Can this happen with a type of epilepsy? Ah, but it rang a great bell when the doctor said:

"a fit in the present state of her health means mischief."

Could this be a coded message? 🤔

The other thing that struck me about this chapter is the architecture of the houses, which I mentioned before. In Bridport ("Port-Bredy") they are far apart, because of the ropemaking business, but in Dorchester ("Casterbridge") there are plenty of narrow streets. So the two maids were able to have a conversation from the upper gable windows, which would sit very close even though they were on opposite sides of the street. Here's an example of one side of the street:

wikimedia - Richard Croft

We can just imagine the two maids on either side of the street, having a conversation! The lower rooms were further apart. These upper windows could be used for a quick escape where necessary, or passing goods across, or all sorts of nefarious purposes. Here though it is just used as a literary device for overheard conversation.

(I posted a photo of the mayor's house, (where Lucetta and Farfrae now live) before; it's now a branch of Barclay's bank, but you can't really see this architectural detail in that one.)

wikimedia - Richard Croft

We can just imagine the two maids on either side of the street, having a conversation! The lower rooms were further apart. These upper windows could be used for a quick escape where necessary, or passing goods across, or all sorts of nefarious purposes. Here though it is just used as a literary device for overheard conversation.

(I posted a photo of the mayor's house, (where Lucetta and Farfrae now live) before; it's now a branch of Barclay's bank, but you can't really see this architectural detail in that one.)

Bionic Jean wrote: "The other thing that struck me about this chapter is the architecture of the houses, which I mentioned before. In Bridport ("Port-Bredy") they are far apart, because of the ropemaking business, but..."

I love the picture of the gabled house, Jean! It makes it easier to picture the maids talking from their windows to each other. Thank you for that.

Your other post mentioned a "coded message" when it comes to Lucetta's "present state of health". It is absolutely code for Lucetta being pregnant. And to be clear, she isn't having fits because she's pregnant; but rather she's having fits because of her fear of losing Farfrae's love - and that is not good for either her, or the baby!!

I love the picture of the gabled house, Jean! It makes it easier to picture the maids talking from their windows to each other. Thank you for that.

Your other post mentioned a "coded message" when it comes to Lucetta's "present state of health". It is absolutely code for Lucetta being pregnant. And to be clear, she isn't having fits because she's pregnant; but rather she's having fits because of her fear of losing Farfrae's love - and that is not good for either her, or the baby!!

Peter wrote: "Bridget wrote: "We have another excellent illustration by Robert Barnes for this chapter. He chose to capture the moment Lucetta sees the effigies in the skimmington ride.

Lucetta's eyes were s..."

What a wonderful analysis of the two illustrations, Peter! As we've talked about before there is so much "doubling" going on in this story. Looking at them together one can see the many layers of this doubling that Barnes is bringing out.

At first I wondered why Barnes wouldn't have illustrated the skimmington. Mostly because I would have like to see his interpretation of what it looked like. But after reading your post, I'm glad he did one of Henchard/Farfrae and another of Lucetta/Elizabeth.

I especially liked your observation that the bag of wheat is broken open in the Henchard/Farfrae illustration, and how that symbolizes so much that has happened between the two men. Nicely done!!

Lucetta's eyes were s..."

What a wonderful analysis of the two illustrations, Peter! As we've talked about before there is so much "doubling" going on in this story. Looking at them together one can see the many layers of this doubling that Barnes is bringing out.

At first I wondered why Barnes wouldn't have illustrated the skimmington. Mostly because I would have like to see his interpretation of what it looked like. But after reading your post, I'm glad he did one of Henchard/Farfrae and another of Lucetta/Elizabeth.

I especially liked your observation that the bag of wheat is broken open in the Henchard/Farfrae illustration, and how that symbolizes so much that has happened between the two men. Nicely done!!

I wonder how much of a disappointment Farfrae's absence is for the organizers of this fete. Clearly, humiliating Lucetta is a key object of this exercise, but it is incomplete if her unsuspecting husband is not a member of the audience. Will they make another attempt to bring this to his attention, or just sit back and wait for the town gossip to do the job for them?

I wonder how much of a disappointment Farfrae's absence is for the organizers of this fete. Clearly, humiliating Lucetta is a key object of this exercise, but it is incomplete if her unsuspecting husband is not a member of the audience. Will they make another attempt to bring this to his attention, or just sit back and wait for the town gossip to do the job for them?Elizabeth-Jane continues to be compassionate and selfless, hurrying to the side of the woman who usurped her in Farfrae's affections. I'm really becoming curious about her fate in this novel. I do so hope for a happy ending for her, but unless another Prince Charming rides into Casterbridge soon, it seems unlikely. :(

Regarding the constables and "felo de se," my take was that the constables were worried that the perpetrators would die by suicide. I took "upon us" to mean either "in our presence," or "as a result of being caught by us." (And yes, dying by suicide in this case seems ... a bit much.)

Regarding the constables and "felo de se," my take was that the constables were worried that the perpetrators would die by suicide. I took "upon us" to mean either "in our presence," or "as a result of being caught by us." (And yes, dying by suicide in this case seems ... a bit much.)

Bridget wrote: "It is absolutely code for Lucetta being pregnant. ..."

Yes indeed, but

"she isn't having fits because she's pregnant; but rather she's having fits because of her fear of losing Farfrae's love"

The quotation I included referred specifically to epilepsy, and this is actually what I was querying. Although I know there are several types of epilepsy, I didn't know of one with recurring fits just by thinking of something! 🤔

So I was asking anyone who might know more about it, whether this is authentic, or whether Thomas Hardy is indulging in a bit of dramatic license with the Victorian trope of "female hysteria".

Sorry if that wasn't clear.

Yes indeed, but

"she isn't having fits because she's pregnant; but rather she's having fits because of her fear of losing Farfrae's love"

The quotation I included referred specifically to epilepsy, and this is actually what I was querying. Although I know there are several types of epilepsy, I didn't know of one with recurring fits just by thinking of something! 🤔

So I was asking anyone who might know more about it, whether this is authentic, or whether Thomas Hardy is indulging in a bit of dramatic license with the Victorian trope of "female hysteria".

Sorry if that wasn't clear.

Jean wrote: The quotation I included referred specifically to epilepsy, and this is actually what I was querying. Although I know there are several types of epilepsy, I didn't know of one with recurring fits just by thinking of something! 🤔 You nailed it, seizures of any kind are not triggered by thoughts!!

Jean wrote: The quotation I included referred specifically to epilepsy, and this is actually what I was querying. Although I know there are several types of epilepsy, I didn't know of one with recurring fits just by thinking of something! 🤔 You nailed it, seizures of any kind are not triggered by thoughts!!She could definitely be having a seizure because of her pregnancy. It can occur when a pregnant woman develops eclampsia, but I'm not sure if doctors in the late 19th century had identified the symptoms of eclampsia yet that an author could have tapped into.

Cindy wrote: Elizabeth-Jane continues to be compassionate and selfless, hurrying to the side of the woman who usurped her in Farfrae's affections. I am continually surprised by EJ!!

Bionic Jean wrote: "The quotation I included referred specifically to epilepsy, and this is actually what I was querying. Although I know there are several types of epilepsy, I didn't know of one with recurring fits just by thinking of something! 🤔..."

Oh, I see what you mean now, Jean that totally makes sense, and its a good question to ask about epilepsy.

I don't know much about epilepsy, but its easy for me to agree with Keith that stress is a trigger. Eclampsia is an interesting thought too, Chris. I've only heard about pre-eclampsia as a condition in late term pregnancy, and I didn't think Lucetta was far enough along for that.

Whatever the reason, I'm happy to have some explanations for Lucetta's fit that don't involve "female hysteria". I get so tired of that trope, I would like to think Hardy meant something else entirely.

Keith - I also like your interpretation of "felo de se". That works too!!

And now to find out what happens to Lucetta . . . . .

Oh, I see what you mean now, Jean that totally makes sense, and its a good question to ask about epilepsy.