The Patrick Hamilton Appreciation Society discussion

This topic is about

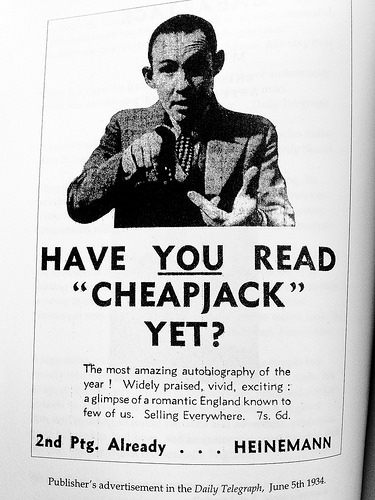

Cheapjack

Hamilton-esque books, authors..

>

"Cheapjack" by Philip Allingham

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

This article, from the Daily Express, is a very good summary that also helps to explain what makes it such an enjoyable and interesting book...

After 80 years, Cheapjack is now a priceless and nostalgic glimpse of an England that has quite vanished, with its canal boats, puffing trains, steam organs and roundabouts.

Allingham, a real-life Mr Toad who was bored by office jobs and always getting sacked, grew fed up with cadging off his parents and sister and so at the age of 22 set off on the open road as a fortune teller. Immaculate in his silk topper and evening attire, he acquired a booth, painted a sign and clients paid half-a-crown (12.5p) for their consultations.

If he was a confidence trickster, Allingham was very plausible, with a knack for assessing character. Today he’d be in demand as a psychotherapist or counsellor.

“People wanted their own views confirmed and a few of their doubts dispelled,” he explained. He had a way of quickly spotting a person’s moods and aspirations and, through a mixture of flattery and perspicacity, coaxed people into opening up. Young men “would offer me an extra shilling if I could describe their future wives”. Allingham had the gift of the gab, mesmerising audiences into wanting to buy his broken fountain pens, patent medicines, stain removers and curling tongs.

The takings mounted up; quite soon, “I was averaging a steady £18 a week.” Nevertheless, it was an insecure existence and nothing much came in during the lean winter months.

Despite the hardship, Allingham relished moving from town to town, free of responsibility. People in the provinces, he decided, were “more simple and illiterate” than Londoners and he was always busy in Lancashire during Wakes Week. He is particularly funny about a few months spent with the Welsh farming fraternity, “a dirty lot of devils, a cunning lot of clods” who are insultingly mean, try to wriggle out of paying their agreed fees but who are gimlet-eyed and credulous about prophecies and spells. (These are precisely my own ancestors; I recognise them.)

After loathing any settled bourgeois routine, Allingham finds he is quite in his element with gypsies who accept him as “a not unpleasant oddity”. He is proud to be told: “You know the value of flash and you can talk.” Where at first Allingham had looked upon his companions as adding “a certain picturesqueness to the scene”, after a few months he admires them more deeply as an honourable and splendid “people apart, living in caravans and marrying among themselves”.

During altercations with yobs, Allingham comes to depend on the gypsies’ courage and we meet such wonderful characters as Doncaster Jock, the Little Major, Cross-Eyed Charlie, Madame Sixpence, Three-Fingered Billy and sundry quack doctors and hunchbacked dwarves.

Having experienced and felt such an affinity with the carnival or circus spirit, Allingham realises: “I had conquered the problem of making a living. I should never be afraid again of being a complete and utter failure.”

Allingham never did settle for a conventional job. He and his wife, we are told in an afterword by Julia Jones, were to own and manage a successful enterprise called the Zodiac Circle, a national fortune-telling business.

http://www.express.co.uk/entertainmen...

After 80 years, Cheapjack is now a priceless and nostalgic glimpse of an England that has quite vanished, with its canal boats, puffing trains, steam organs and roundabouts.

Allingham, a real-life Mr Toad who was bored by office jobs and always getting sacked, grew fed up with cadging off his parents and sister and so at the age of 22 set off on the open road as a fortune teller. Immaculate in his silk topper and evening attire, he acquired a booth, painted a sign and clients paid half-a-crown (12.5p) for their consultations.

If he was a confidence trickster, Allingham was very plausible, with a knack for assessing character. Today he’d be in demand as a psychotherapist or counsellor.

“People wanted their own views confirmed and a few of their doubts dispelled,” he explained. He had a way of quickly spotting a person’s moods and aspirations and, through a mixture of flattery and perspicacity, coaxed people into opening up. Young men “would offer me an extra shilling if I could describe their future wives”. Allingham had the gift of the gab, mesmerising audiences into wanting to buy his broken fountain pens, patent medicines, stain removers and curling tongs.

The takings mounted up; quite soon, “I was averaging a steady £18 a week.” Nevertheless, it was an insecure existence and nothing much came in during the lean winter months.

Despite the hardship, Allingham relished moving from town to town, free of responsibility. People in the provinces, he decided, were “more simple and illiterate” than Londoners and he was always busy in Lancashire during Wakes Week. He is particularly funny about a few months spent with the Welsh farming fraternity, “a dirty lot of devils, a cunning lot of clods” who are insultingly mean, try to wriggle out of paying their agreed fees but who are gimlet-eyed and credulous about prophecies and spells. (These are precisely my own ancestors; I recognise them.)

After loathing any settled bourgeois routine, Allingham finds he is quite in his element with gypsies who accept him as “a not unpleasant oddity”. He is proud to be told: “You know the value of flash and you can talk.” Where at first Allingham had looked upon his companions as adding “a certain picturesqueness to the scene”, after a few months he admires them more deeply as an honourable and splendid “people apart, living in caravans and marrying among themselves”.

During altercations with yobs, Allingham comes to depend on the gypsies’ courage and we meet such wonderful characters as Doncaster Jock, the Little Major, Cross-Eyed Charlie, Madame Sixpence, Three-Fingered Billy and sundry quack doctors and hunchbacked dwarves.

Having experienced and felt such an affinity with the carnival or circus spirit, Allingham realises: “I had conquered the problem of making a living. I should never be afraid again of being a complete and utter failure.”

Allingham never did settle for a conventional job. He and his wife, we are told in an afterword by Julia Jones, were to own and manage a successful enterprise called the Zodiac Circle, a national fortune-telling business.

http://www.express.co.uk/entertainmen...

I have now finished…

Cheapjack by Philip Allingham

This compelling, witty, poignant, well written book deserves to be better known and is essential reading for anyone interested in the social history of early twentieth century England and Wales as it offers a priceless and nostalgic glimpse of a world that, whilst recognisable, has quite vanished.

Click here to read my 5 star review

Cheapjack by Philip Allingham

This compelling, witty, poignant, well written book deserves to be better known and is essential reading for anyone interested in the social history of early twentieth century England and Wales as it offers a priceless and nostalgic glimpse of a world that, whilst recognisable, has quite vanished.

Click here to read my 5 star review

Julia Jones, who wrote the afterword, tweeted to me about Cheapjack the other day...

@nigeyb We love this book - widely underrated, I fear

Widely underrated is right. Shame. Let's help to put that right.

@nigeyb We love this book - widely underrated, I fear

Widely underrated is right. Shame. Let's help to put that right.

Books mentioned in this topic

Cheapjack (other topics)Cheapjack (other topics)

Cheapjack (other topics)

Authors mentioned in this topic

Julia Jones (other topics)Philip Allingham (other topics)

Philip Allingham (other topics)

Francis Wheen (other topics)

Margery Allingham (other topics)

http://www.amazon.co.uk/CHEAPJACK-Van...

It seems like the sort of book that would be hard to go wrong with, and I'm planning to order a copy... unless one of you can warn me off? "

Started this earlier today Mark and so far so blimming wonderful. A wonderful glimpse into a lost world.

One interesting point, according to Francis Wheen’s introductory essay, Philip Allingham was responsible for introducing many now familiar slang words into the lexicon (e.g. bevy, busker, rozzer, gaffer, punter and many more).

So how is this Hamilton-esque? I'm saying it's another example of a genteel type sliding down the social scale a la our man Patrick. What differentiates this from, say, Orwell’s “Down and Out” is that Philip Allingham made not attempt to hide his genteel origins and tries to turn it to his advantage.

Cheapjack by Philip Allingham

This review on Amazon UK sounds very positive...

Philip Allingham was born into respectability. His father was a writer, his mother was a writer, his older sister Margery Allingham went on to become one of Britain's most popular crime novelists. Young Philip, sadly, distinguished himself at very little - unless you count flunking his Oxford entrance exam in heroic fashion as an achievement. What Philip did possess, though, was an uncanny ability to "read" people, and one day in 1927, tired of failing in a succession of boring, dead-end jobs his family connections had found for him, he decided to put that talent to use.

"Cheapjack" recounts Allingham's efforts to earn a living as a palmist and fortune-teller, initially in the pubs of London and then as an itinerant showman at fairs and markets the length of the land. It's a tale of rogues and charlatans, gypsies and fairground folk, tick-off merchants, pitchers and waver-workers. Allingham recalls his adventures among a cast of memorable characters - Three Fingered Billy, a hard-drinking Geordie, the Little Major, a walking encyclopaedia of every fairground trick in the book, and the appalling Alfie Holmsworth, theatrical "agent" to the gullible and deluded.

More than that, "Cheapjack" is a fascinating slice of social history. Studded with rich fairground slang, it evokes a pre-war era when every community had its thriving market, entire towns shut down and went on holiday during their "Wakes Weeks", and working people took their enjoyment collectively at the fairs and festivals that marked the passage of the seasons. It's a world that's all but disappeared now, but one that lives on in Philip Allingham's poignant memoir, which is often touching, occasionally hilarious, and never less than thoroughly absorbing.

I'll keep you posted with progress and perhaps inspire some of you to read it yourselves and contribute to this discussion.