The History Book Club discussion

HEALTH- MEDICINE - SCIENCE

>

PHYSICS

message 1:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(new)

Apr 26, 2011 04:21AM

Mod

Mod

reply

|

flag

by Richard P. Brennan

by Richard P. BrennanAmazon:

Physics turned weird recently--really weird. That doesn't necessarily mean that modern physicists are weird, though, does it? Well, yes and no, says science writer Richard P. Brennan, whose book Heisenberg Probably Slept Here chronicles the lives of seven great scientists of the 20th century--Einstein, Planck, Rutherford, Bohr, Heisenberg, Feynman, and Gell-Mann--as well as their spiritual father, Isaac Newton. Fascinating and funny, each biographical sketch illuminates the man, his surroundings, and his achievements with unusual clarity.

Writing about the enormous driving force engendered in physics by World War II, with scientists on both sides striving to advance their knowledge far enough to win a terrible war, Brennan shows us the delicate contingencies that led to our current level of understanding. What if the Nazis hadn't rejected "Jewish science"? What if the Allies had assassinated Heisenberg? More generally, he tells us stories of men working like maniacs to answer some of the hardest, most basic questions about our universe ever devised, only to find more questions for the next century to ponder. We may hope that a new generation will be inspired by these stories to take weird 20th-century science much further; perhaps some day quantum mechanics will seem more quaint than abstruse. --Rob Lightner

I hear good things about this book:

I hear good things about this book:

Kai Bird

Kai BirdPublisher's Weekly:

Starred Review. Though many recognize Oppenheimer (1904–1967) as the father of the atomic bomb, few are as familiar with his career before and after Los Alamos. Sherwin (A World Destroyed) has spent 25 years researching every facet of Oppenheimer's life, from his childhood on Manhattan's Upper West Side and his prewar years as a Berkeley physicist to his public humiliation when he was branded a security risk at the height of anticommunist hysteria in 1954. Teaming up with Bird, an acclaimed Cold War historian (The Color of Truth), Sherwin examines the evidence surrounding Oppenheimer's "hazy and vague" connections to the Communist Party in the 1930s—loose interactions consistent with the activities of contemporary progressives. But those politics, in combination with Oppenheimer's abrasive personality, were enough for conservatives, from fellow scientist Edward Teller to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, to work at destroying Oppenheimer's postwar reputation and prevent him from swaying public opinion against the development of a hydrogen bomb. Bird and Sherwin identify Atomic Energy Commission head Lewis Strauss as the ringleader of a "conspiracy" that culminated in a security clearance hearing designed as a "show trial." Strauss's tactics included illegal wiretaps of Oppenheimer's attorney; those transcripts and other government documents are invaluable in debunking the charges against Oppenheimer. The political drama is enhanced by the close attention to Oppenheimer's personal life, and Bird and Sherwin do not conceal their occasional frustration with his arrogant stonewalling and panicky blunders, even as they shed light on the psychological roots for those failures, restoring human complexity to a man who had been both elevated and demonized. 32 pages of photos not seen by PW. (Apr. 10)

Copyright © Reed Business Information,

This is supposed to be good as well:

This is supposed to be good as well:

Walter Isaacson

Walter IsaacsonAmazon:

As a scientist, Albert Einstein is undoubtedly the most epic among 20th-century thinkers. Albert Einstein as a man, however, has been a much harder portrait to paint, and what we know of him as a husband, father, and friend is fragmentary at best. With Einstein: His Life and Universe, Walter Isaacson (author of the bestselling biographies Benjamin Franklin and Kissinger) brings Einstein's experience of life, love, and intellectual discovery into brilliant focus. The book is the first biography to tackle Einstein's enormous volume of personal correspondence that heretofore had been sealed from the public, and it's hard to imagine another book that could do such a richly textured and complicated life as Einstein's the same thoughtful justice. Isaacson is a master of the form and this latest opus is at once arresting and wonderfully revelatory. --Anne Bartholomew

Freeman John Dyson

Freeman John DysonProduct info:

Spanning the years from World War II, when he was a civilian statistician in the operations research section of the Royal Air Force Bomber Command, through his studies with Hans Bethe at Cornell University, his early friendship with Richard Feynman, and his postgraduate work with J. Robert Oppenheimer, Freeman Dyson has composed an autobiography unlike any other. Dyson evocatively conveys the thrill of a deep engagement with the world-be it as scientist, citizen, student, or parent. Detailing a unique career not limited to his groundbreaking work in physics, Dyson discusses his interest in minimizing loss of life in war, in disarmament, and even in thought experiments on the expansion of our frontiers into the galaxies.

Bentley wrote: "Terrific books, we may have to do a read in this area."

Bentley wrote: "Terrific books, we may have to do a read in this area."If there is interest, I am so there. Science, especially physics and math, is sooooo interesting. I've got lots of books to add to these threads. Gotta get around to it.

This looks like fun for the lay scientist or sci-fi fan!

This looks like fun for the lay scientist or sci-fi fan! Goodreads Blurb:

A fascinating exploration of the science of the impossible—from death rays and force fields to invisibility cloaks—revealing to what extent such technologies might be achievable decades or millennia into the future.

One hundred years ago, scientists would have said that lasers, televisions, and the atomic bomb were beyond the realm of physical possibility. In Physics of the Impossible, the renowned physicist Michio Kaku explores to what extent the technologies and devices of science fiction that are deemed equally impossible today might well become commonplace in the future.

From teleportation to telekinesis, Kaku uses the world of science fiction to explore the fundamentals—and the limits—of the laws of physics as we know them today. He ranks the impossible technologies by categories—Class I, II, and III, depending on when they might be achieved, within the next century, millennia, or perhaps never. In a compelling and thought-provoking narrative, he explains:

· How the science of optics and electromagnetism may one day enable us to bend light around an object, like a stream flowing around a boulder, making the object invisible to observers “downstream”

· How ramjet rockets, laser sails, antimatter engines, and nanorockets may one day take us to the nearby stars

· How telepathy and psychokinesis, once considered pseudoscience, may one day be possible using advances in MRI, computers, superconductivity, and nanotechnology

· Why a time machine is apparently consistent with the known laws of quantum physics, although it would take an unbelievably advanced civilization to actually build one

Kaku uses his discussion of each technology as a jumping-off point to explain the science behind it. An extraordinary scientific adventure, Physics of the Impossible takes readers on an unforgettable, mesmerizing journey into the world of science that both enlightens and entertains.

by

by

Michio Kaku

Michio Kaku

Hi folks,

Hi folks,Not sure how active this thread is! Just to drop in a recommendation for a lovely book, Cosmic Imagery: Key Images in the History of Science. Mostly physics, but some other stuff as well, and from a nicely historical point of view.

Thank you Marc; all of the threads are active- only thing we need to have the correct citation: book cover, author's photo if available and also the author's link. Did you read the book Marc? This is how the citation should look. Was the book technical in nature or easy reading?

by

by

John D. Barrow

John D. Barrow

Review:

We live in an age of images — the first pictures of Earth from space; nuclear bomb mushroom clouds; Vesalius’s haunting human anatomy pictures — iconic and influential images. John Barrow traces their history and influence to tell the story of modern science.

by

by

John D. Barrow

John D. BarrowReview:

We live in an age of images — the first pictures of Earth from space; nuclear bomb mushroom clouds; Vesalius’s haunting human anatomy pictures — iconic and influential images. John Barrow traces their history and influence to tell the story of modern science.

Thanks for the info about post format! I read this, and have bought it is a present for several non-scientist friends. It's a lovely selection of short essays about key theories, each anchored around an image or illustration. Easy reading, and the short-chapter structure makes it ideal for browsing or as a coffee-table book.

Thanks for the info about post format! I read this, and have bought it is a present for several non-scientist friends. It's a lovely selection of short essays about key theories, each anchored around an image or illustration. Easy reading, and the short-chapter structure makes it ideal for browsing or as a coffee-table book.

Thank you Marc for your contribution. It sounds like an interesting read.

Thank you Marc for your contribution. It sounds like an interesting read.We are always on the look out for good books for the lay reader in the sciences and would love to hear more about your favorites. We have dozens of threads in this Health, Medicine, and Science folder and are looking to build activity here.

Thanks! My own background is in the history and philosophy of astronomy and cosmology. There are many great textbooks and monographs in the field, but the best introduction remains Koestler's The Sleepwalkers. It's a look at the development of our ideas about the universe. At its heart are three long, psychologically insightful, character studies of Copernicus, Tycho and Kepler (and if the last two names make you think "who?" then I highly recommend this as a starting place!)

Thanks! My own background is in the history and philosophy of astronomy and cosmology. There are many great textbooks and monographs in the field, but the best introduction remains Koestler's The Sleepwalkers. It's a look at the development of our ideas about the universe. At its heart are three long, psychologically insightful, character studies of Copernicus, Tycho and Kepler (and if the last two names make you think "who?" then I highly recommend this as a starting place!)

Thanks. I'm one of the ones that thinks "who?" so I think I'll add this one to my huge to-be-read pile!

Thanks. I'm one of the ones that thinks "who?" so I think I'll add this one to my huge to-be-read pile!

Hi Guys, the conversation is tremendous and Marc I want you to continue the dialogue; However, we have some rules for citations here and a rule of no self promotion with is iron clad. Sooooooo.

Here is the correct citation for message 16. You have got the book cover down, great thank you, and if there was no photo you would not have to post the no photo icon (but there was a photo) (see below); but you forgot the third item which is the author's name in linkable text. Here is the example (and Marc you are so making great progress). You will wonder when you get the hang of this why you thought it was so hard.

by

by

Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler

Now on the self promotion - sorry our rule is ironclad even just an itsy, bitsy step into that realm.

Here is the correct citation for message 16. You have got the book cover down, great thank you, and if there was no photo you would not have to post the no photo icon (but there was a photo) (see below); but you forgot the third item which is the author's name in linkable text. Here is the example (and Marc you are so making great progress). You will wonder when you get the hang of this why you thought it was so hard.

by

by

Arthur Koestler

Arthur KoestlerNow on the self promotion - sorry our rule is ironclad even just an itsy, bitsy step into that realm.

Completely understood -- and I'll do better with my next recommendation! Thanks for being patient with me...

Completely understood -- and I'll do better with my next recommendation! Thanks for being patient with me...

That is of course no problem Marc - that is what we are here for.

One thing which may help you is to introduce yourself on the introduction thread:

http://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/9...

Once you do that you will get some helpful tips and links to threads that will help you get acclimated and even learn those dastardly citations (smile).

Best,

Bentley

One thing which may help you is to introduce yourself on the introduction thread:

http://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/9...

Once you do that you will get some helpful tips and links to threads that will help you get acclimated and even learn those dastardly citations (smile).

Best,

Bentley

That is OK Marc we understand and that is what we are here for - to assist you when necessary.

You might want to post on the introduction thread:

http://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/9...

That will help you out a lot: because then one of the assisting moderators will post some helpful links to get you acclimated to how to do those dastardly citations which are critical for the goodreads software to properly populate our site; and other links which will help teach you the ropes - so to speak.

All best,

Bentley

You might want to post on the introduction thread:

http://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/9...

That will help you out a lot: because then one of the assisting moderators will post some helpful links to get you acclimated to how to do those dastardly citations which are critical for the goodreads software to properly populate our site; and other links which will help teach you the ropes - so to speak.

All best,

Bentley

The Dreams That Stuff Is Made Of

The Dreams That Stuff Is Made Of by

by

Stephen Hawking

Stephen HawkingSynopsis

God does not play dice with the universe.” So said Albert Einstein in response to the first discoveries that launched quantum physics, as they suggested a random universe that seemed to violate the laws of common sense. This 20th-century scientific revolution completely shattered Newtonian laws, inciting a crisis of thought that challenged scientists to think differently about matter and subatomic particles.The Dreams That Stuff Is Made Of compiles the essential works from the scientists who sparked the paradigm shift that changed the face of physics forever, pushing our understanding of the universe on to an entirely new level of comprehension. Gathered in this anthology is the scholarship that shocked and befuddled the scientific world, including works by Niels Bohr, Max Planck, Werner Heisenberg, Max Born, Erwin Schrodinger, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Richard Feynman, as well as an introduction by today’s most celebrated scientist, Stephen Hawking.

Jill wrote: "God does not play dice with the universe..."

Jill wrote: "God does not play dice with the universe..."That was, indeed, Einstein's view, to the end.

But one of the modern physicists said "not only does God play dice, but he doesn't let us see them".

Kathy wrote: "New book out this past month:

Kathy wrote: "New book out this past month:Time Reborn: From the Crisis in Physics to the Future of the Universe

by [..."

by [..."Many years ago I earned a BS and MS in physics and was thoroughly fascinated by relativity and quantum mechanics; so much so that I spent endless hours writing up notes about ideas of mine. But my career took me into software. It has been a long time since I read a book on physics but this sounds like the kind of book to stir my mind. Thanks Kathy.

There was an interesting review of this in the last month - but I forget if it was in the NY Times Book Review or NY Review of Books.

There was an interesting review of this in the last month - but I forget if it was in the NY Times Book Review or NY Review of Books.It does sound interesting.

Madame Curie

Madame CurieThis is an old book, but one dear to my heart. I checked it out from either my school or public library in my youth. My personal take-home message was this: girls can be science nerds too (even if they seem to be outnumbered by the boys)! I'm sure there are more objective works on the life and achievements of Marie Curie--this one is rather lovingly written by Curie's daughter.

Goodreads synopsis:

Marie Sklodowska Curie (1867�1934) was the first woman scientist to win worldwide acclaim and was, indeed, one of the great scientists of the twentieth century. Written by Curie’s daughter, the renowned international activist Eve Curie, this biography chronicles Curie’s legendary achievements in science, including her pioneering efforts in the study of radioactivity and her two Nobel Prizes in Physics and Chemistry. It also spotlights her remarkable life, from her childhood in Poland, to her storybook Parisian marriage to fellow scientist Pierre Curie, to her tragic death from the very radium that brought her fame. Now updated with an eloquent, rousing introduction by best-selling author Natalie Angier, this timeless biography celebrates an astonishing mind and a extraordinary woman’s life.

by

by

Eve Curie

Eve Curie

Kathy wrote: "Robert Oppenheimer: His Life and Mind

Kathy wrote: "Robert Oppenheimer: His Life and Mind by Ray Monk (no photo)

by Ray Monk (no photo)I am reading this now. It's outstanding. But the subtitle is not "His Life and Mind" but "A Life inside the Center".

Monk gives a nuanced view of Oppenheimer: A man of unquestioned brilliance (and not just in physics; he spoke Greek, Latin, French and Sanskrit well enough to read classics in each language; he was an expert on impressionist art; he knew a great deal about the southwest United States) but unusual naivete and arrogance. Naive? Before he had been granted security clearance he tried to hire two associates who were members of the Communist Party and interested in passing information to Russia; he also slept with a former mistress who was also a member). Arrogant? As a teen, he used to go up to people and say "Ask me a question in Latin and I will reply in Greek" and, much later, when asked why Groves picked him to head Los Alamos he said (with no apparent sarcasm) "he wanted the best man".

Monk concludes that while there is no evidence that Oppenheimer gave information to the Russians, he acted in ways that would raise legitimate concerns about whether he would or not.

A Kindle daily deal for $1.99. I've had this on my TBR list forever, so I grabbed it today.

A Kindle daily deal for $1.99. I've had this on my TBR list forever, so I grabbed it today.  by

by

Richard Rhodes.

Richard Rhodes.

I read this book last month and found it extremely disturbing but I couldn't put it down. There was so much that the scientists did not know before dropping the bomb on Hiroshima....would it create a break in the earth's crust or set the atmosphere on fire? And they didn't give a thought to the effects of the deadly radiation sickness which killed outright or lingered for years. Very scary indeed. (Please note that the synopsis taken from GR isn't particularly favorable.)

I read this book last month and found it extremely disturbing but I couldn't put it down. There was so much that the scientists did not know before dropping the bomb on Hiroshima....would it create a break in the earth's crust or set the atmosphere on fire? And they didn't give a thought to the effects of the deadly radiation sickness which killed outright or lingered for years. Very scary indeed. (Please note that the synopsis taken from GR isn't particularly favorable.)Day One: Before Hiroshima and After

by

by

Peter Wyden

Peter WydenSynopsis:

Wyden relies on novelistic touches drawn from interviews to spice up a story already well known. Here, too, we're treated to repetitions of insignificant pieces of color--such as J. Robert Oppenheimer's way with a martini--or of trivial details: does anyone care that the pistol tucked into General Leslie Groves' trousers was a "tiny Colt automatic...a .32 caliber on a .25 caliber frame"? But his technique, while no more insightful than in his previous narratives, is easier to take here--partly because the main figures, the physicists, are real characters. Take Leo Szilard, the Hungarian scientist who adopted the atomic bomb as a personal crusade in fear of a German military juggernaut. Living out of two suitcases that contained everything he owned, Szilard provided the impetus to fission research & teamed with Enrico Fermi in executing the successful chain reaction test at the Univ. of Chicago. (The test was kept secret from its president, Robert Hutchins, by physical science dean Arthur Holly Compton for fear that Hutchins would veto it as too dangerous.) Szilard, a delicatessenfare addict, didn't join Oppenheimer's Los Alamos project; but he did manage to keep up a running feud with Groves--in part, over the extravagant remuneration Szilard expected from his reactor patent. Wandering about, lost in thought, Szilard drove the security men tailing him crazy. (Groves was trying to get something on Szilard. He never did.) When Szilard began another crusade, this time to forestall the actual use of the bomb on Japan, he became Groves' principal pain (& a pain to Oppenheimer, who'd come out forcefully in favor of the bomb's immediate use). Particularly disturbing is the thread of lack-of-attention to radiation & its effects. (They assumed radiation effects wouldn't carry as far as the blast effects.) The news of radiation death from Hiroshima & Nagasaki was a shock to the scientists & covered up by Groves. The establishment of Los Alamos & the bureaucratic labyrinths are handled well.

Kathy wrote: "The Making of the Atomic Bomb: 25th Anniversary Edition

Kathy wrote: "The Making of the Atomic Bomb: 25th Anniversary Edition by

by  Richard Rhodes

Richard RhodesSynopsis:

Winner of the..."

One of the great science books. I read it many years ago (I think just after it came out)

Atomic Accidents: A History of Nuclear Meltdowns and Disasters: From the Ozark Mountains to Fukushima

by James Mahaffey (no photo)

by James Mahaffey (no photo)

Synopsis:

From the moment radiation was discovered in the late nineteenth century, nuclear science has had a rich history of innovative scientific exploration and discovery, coupled with mistakes, accidents, and downright disasters.

Mahaffey, a long-time advocate of continued nuclear research and nuclear energy, looks at each incident in turn and analyzes what happened and why, often discovering where scientists went wrong when analyzing past meltdowns.

Every incident has lead to new facets in understanding about the mighty atom—and Mahaffey puts forth what the future should be for this final frontier of science that still holds so much promise.

by James Mahaffey (no photo)

by James Mahaffey (no photo)Synopsis:

From the moment radiation was discovered in the late nineteenth century, nuclear science has had a rich history of innovative scientific exploration and discovery, coupled with mistakes, accidents, and downright disasters.

Mahaffey, a long-time advocate of continued nuclear research and nuclear energy, looks at each incident in turn and analyzes what happened and why, often discovering where scientists went wrong when analyzing past meltdowns.

Every incident has lead to new facets in understanding about the mighty atom—and Mahaffey puts forth what the future should be for this final frontier of science that still holds so much promise.

An upcoming book:

Release date: October 22, 2014

Serving the Reich: The Struggle for the Soul of Physics under Hitler

by

by

Philip Ball

Philip Ball

Synopsis:

After World War II, most scientists in Germany maintained that they had been apolitical or actively resisted the Nazi regime, but the true story is much more complicated. In Serving the Reich, Philip Ball takes a fresh look at that controversial history, contrasting the career of Peter Debye, director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in Berlin, with those of two other leading physicists in Germany during the Third Reich: Max Planck, the elder statesman of physics after whom Germany’s premier scientific society is now named, and Werner Heisenberg, who succeeded Debye as director of the institute when it became focused on the development of nuclear power and weapons.

Mixing history, science, and biography, Ball’s gripping exploration of the lives of scientists under Nazism offers a powerful portrait of moral choice and personal responsibility, as scientists navigated “the grey zone between complicity and resistance.” Ball’s account of the different choices these three men and their colleagues made shows how there can be no clear-cut answers or judgement of their conduct. Yet, despite these ambiguities, Ball makes it undeniable that the German scientific establishment as a whole mounted no serious resistance to the Nazis, and in many ways acted as a willing instrument of the state.

Serving the Reich considers what this problematic history can tell us about the relationship of science and politics today. Ultimately, Ball argues, a determination to present science as an abstract inquiry into nature that is “above politics” can leave science and scientists dangerously compromised and vulnerable to political manipulation.

Release date: October 22, 2014

Serving the Reich: The Struggle for the Soul of Physics under Hitler

by

by

Philip Ball

Philip BallSynopsis:

After World War II, most scientists in Germany maintained that they had been apolitical or actively resisted the Nazi regime, but the true story is much more complicated. In Serving the Reich, Philip Ball takes a fresh look at that controversial history, contrasting the career of Peter Debye, director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in Berlin, with those of two other leading physicists in Germany during the Third Reich: Max Planck, the elder statesman of physics after whom Germany’s premier scientific society is now named, and Werner Heisenberg, who succeeded Debye as director of the institute when it became focused on the development of nuclear power and weapons.

Mixing history, science, and biography, Ball’s gripping exploration of the lives of scientists under Nazism offers a powerful portrait of moral choice and personal responsibility, as scientists navigated “the grey zone between complicity and resistance.” Ball’s account of the different choices these three men and their colleagues made shows how there can be no clear-cut answers or judgement of their conduct. Yet, despite these ambiguities, Ball makes it undeniable that the German scientific establishment as a whole mounted no serious resistance to the Nazis, and in many ways acted as a willing instrument of the state.

Serving the Reich considers what this problematic history can tell us about the relationship of science and politics today. Ultimately, Ball argues, a determination to present science as an abstract inquiry into nature that is “above politics” can leave science and scientists dangerously compromised and vulnerable to political manipulation.

Krishna,

Krishna,Do you have a strong background in science? This sounds very interesting, but I'm afraid it would be beyond my level of understanding. On the other hand, I have seen author Michio Kaku on the CBS morning news show and he seems like a really dynamic man, who genuinely gets excited by science. I'm not surprised that he is also an excellent writer.

by

by

Michio Kaku

Michio Kaku

Your English is great!

Your English is great! CBS is a big television network in the United States. Here is a website which might give you some idea of what their morning news show is like: http://www.cbsnews.com/cbs-this-morning/

All of the big networks (CBS, NBC, ABC) have morning news shows. I am retired so I have time to watch one of them. :-) I like CBS because it is more news oriented than the others, which have more emphasis on pop culture.

Incidentally, I think it is great that you are in grade 10 and I am a retired person from different countries and cultures and yet we can communicate as equals on this site on the internet! I hope you stick around. I taught high school ESL (English as a Second Language) and I have always been interested in getting to know people from other places.

I've found the following to be interesting, not overly technical, science books. My 87 year old, non-native English speaking grandmother didn't have any problems understanding these books.

I've found the following to be interesting, not overly technical, science books. My 87 year old, non-native English speaking grandmother didn't have any problems understanding these books. by

by

Nessa Carey

Nessa Carey by

by

Elaine Morgan

Elaine Morgan by

by

Theo Colborn

Theo Colborn by Randolph M. Nesse [no photo]

by Randolph M. Nesse [no photo] by

by

Neil Shubin

Neil Shubin by Anthony D. Fredericks [no photo]

by Anthony D. Fredericks [no photo] by Peter Forbes [no photo]

by Peter Forbes [no photo] by

by

Emily Anthes

Emily Anthes by William Stolzenburg [no photo]

by William Stolzenburg [no photo] by David R. Montgomery [no photo]

by David R. Montgomery [no photo] by

by

David Quammen

David Quammen by Dennis McCarthy [no photo]

by Dennis McCarthy [no photo]

Krishna, keep posting and conversing in English and you will get better. I think you are doing fabulously.

All remember that this thread focuses on physics and only books dealing with something to do with physics should be posted here. There are threads devoted to specific other areas so just look through the listing and you will find them.

All remember that this thread focuses on physics and only books dealing with something to do with physics should be posted here. There are threads devoted to specific other areas so just look through the listing and you will find them.

Gravitational waves discovery now officially dead

Gravitational waves discovery now officially deadBy Ron Cowen

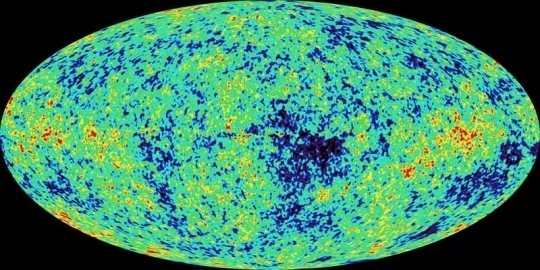

A team of astronomers that last year reported evidence for gravitational waves from the early Universe has now withdrawn the claim. A joint analysis of data recorded by the team's South Pole telescope and by the European spacecraft Planck has revealed that the signal can be entirely attributed to dust in the Milky Way rather than having a more ancient, cosmic origin.

The European Space Agency (ESA) announced the long-awaited results on 30 January, a day after a summary of it had been unintentionally posted online by French members of the Planck team and then widely circulated before it was taken down.

The March finding was released by researchers using a radio telescope at the South Pole called BICEP2. It had hinged on finding a curlicue pattern in the polarization of the cosmic microwave background, the Big Bang's relic radiation. The team attributed the pattern to gravitational waves — ripples in space-time — generated during the earliest moment of the Universe when cosmologists believe the cosmos underwent a brief but tumultuous episode of expansion known as inflation. If detected, the primordial waves would confirm the highly successful but unproven theory of inflation.

Read the remainder of Nature's news here: Gravitational waves discovery now officially dead

An upcoming book:

Release date: April 14, 2015

The Man Who Stalked Einstein: How Nazi Scientist Philipp Lenard Changed the Course of History

by Bruce J. Hillman (no photo)

by Bruce J. Hillman (no photo)

Synopsis:

By the end of World War I, Albert Einstein had become the face of the new science of theoretical physics and had made some powerful enemies. One of those enemies, Nobel Prize winner Philipp Lenard, spent a career trying to discredit him. Their story of conflict, pitting Germany’s most widely celebrated Jew against the Nazi scientist who was to become Hitler’s chief advisor on physics, had an impact far exceeding what the scientific community felt at the time. Indeed, their mutual antagonism affected the direction of science long after 1933, when Einstein took flight to America and changed the history of two nations. The Man Who Stalked Einstein details the tense relationship between Einstein and Lenard, their ideas and actions, during the eventful period between World War I and World War II.

Release date: April 14, 2015

The Man Who Stalked Einstein: How Nazi Scientist Philipp Lenard Changed the Course of History

by Bruce J. Hillman (no photo)

by Bruce J. Hillman (no photo)Synopsis:

By the end of World War I, Albert Einstein had become the face of the new science of theoretical physics and had made some powerful enemies. One of those enemies, Nobel Prize winner Philipp Lenard, spent a career trying to discredit him. Their story of conflict, pitting Germany’s most widely celebrated Jew against the Nazi scientist who was to become Hitler’s chief advisor on physics, had an impact far exceeding what the scientific community felt at the time. Indeed, their mutual antagonism affected the direction of science long after 1933, when Einstein took flight to America and changed the history of two nations. The Man Who Stalked Einstein details the tense relationship between Einstein and Lenard, their ideas and actions, during the eventful period between World War I and World War II.

Nucleus: A Trip Into the Heart of Matter

Nucleus: A Trip Into the Heart of Matter by Ray Mackintosh (no photo)

by Ray Mackintosh (no photo)Synopsis:

At the core of the atom, enshrouded by electrons, lies the nucleus. The discovery of the nucleus transformed the past century and will revolutionize this one. Though many persons associate nuclear physics with weapons of mass destruction, it is an exciting, cutting-edge science that has helped to save lives through innovative medical technologies, such as the MRI. In nuclear astrophysics, state-of-the-art theoretical and computer models help to explain the powerful stellar explosions known as supernovas, to account for how stars shine, and to describe how the chemical elements in the universe were formed.Nucleus: A Trip into the Heart of Matter by Ray Mackintosh, Jim Al-Khalili, Bjorn Jonsen, and Theresa Penae is a lavishly illustrated book filled with lively prose and captivating details that describe the evolution of our understanding of this phenomenon. The authors, who include expert nuclear physicists and acclaimed science journalists, tell the story of the nucleus from the early experimental work of the quiet New Zealander Lord Rutherford to the huge atom-smashing machines of today and beyond. Nucleus tells of the protons and neutrons of which the nucleus is made, why some nuclei crumble and are radioactive, and how scientists came up with the "standard model," which shows the nucleus composed of quarks held together by gluons. Nucleus is also the tale of the people behind the struggle to understand this fascinating subject more fully, and of how a vibrant research community uses the power of the nucleus to probe unanswered scientific questions while others seek to harness the nucleus as a tool of twenty-first-century medicine.

Intended for a general audience, this book unravels the scientific mysteries that surround the subject of the nucleus. Anyone with a passing interest in science will delight in this guide to the nuclear age.

Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology

Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology by Michelle M. Wright (no photo)

by Michelle M. Wright (no photo)Synopsis:

What does it mean to be Black? If Blackness is not biological in origin but socially and discursively constructed, does the meaning of Blackness change over time and space? In Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology, Michelle M. Wright argues that although we often explicitly define Blackness as a “what,” it in fact always operates as a “when” and a “where.”

By putting lay discourses on spacetime from physics into conversation with works on identity from the African Diaspora, Physics of Blackness explores how Middle Passage epistemology subverts racist assumptions about Blackness, yet its linear structure inhibits the kind of inclusive epistemology of Blackness needed in the twenty-first century. Wright then engages with bodies frequently excluded from contemporary mainstream consideration: Black feminists, Black queers, recent Black African immigrants to the West, and Blacks whose histories may weave in and out of the Middle Passage epistemology but do not cohere to it.

Physics of Blackness takes the reader on a journey both known and unfamiliar—from Isaac Newton’s laws of motion and gravity to the contemporary politics of diasporic Blackness in the academy, from James Baldwin’s postwar trope of the Eiffel Tower as the site for diasporic encounters to theoretical particle physics’ theory of multiverses and superpositioning, to the almost erased lives of Black African women during World War II. Accessible in its style, global in its perspective, and rigorous in its logic, Physics of Blackness will change the way you look at Blackness.

A New Approach to the Physics of the Dark Matter and Dark Energy and Generalized Hawking Entropy and Temperature

A New Approach to the Physics of the Dark Matter and Dark Energy and Generalized Hawking Entropy and Temperature by Shahram Khosravi (no photos)

by Shahram Khosravi (no photos)Synopsis:

My new approach to quantum gravity shows that the Universe is the net effect of multiple levels of universes. I'll shows that my new approach to quantum gravity also provides a new approach to the physics of the dark matter and dark energy. I'll prove that the non-ordinary matter and energy contributions from multiple levels of universes make up the dark matter and dark energy. I'll not only provide a mechanism for the dark matter and dark energy but also show why the dark matter and dark energy constitutes the overwhelming portion of the overall matter and energy content of the Universe.

I'll use my new approach to quantum gravity to show that matter and energy exists everywhere in the Universe setting the stage for my proposal for the generalized Hawking entropy and temperature not only for black holes but also for non-black hole spacetimematter regions. I’ll first derive the classical Hawking entropy and temperature from my new approach to quantum gravity and then add higher order corrections to them and also generalize them to non-black hole spacetimematter regions in addition to black holes.

I’ll also use this approach to provide theoretical calculation for the Universe entropy and temperature. Finally, I’ll show that the vacuum quantum fluctuations of multiple levels of universes contribute to the cosmological constant and use this to provide a new approach to the calculation of the cosmological constant.

Einstein and the Quantum: The Quest of the Valiant Swabian

by A. Douglas Stone (no photo)

by A. Douglas Stone (no photo)

Synopsis:

Einstein and the Quantum reveals for the first time the full significance of Albert Einstein's contributions to quantum theory. Einstein famously rejected quantum mechanics, observing that God does not play dice. But, in fact, he thought more about the nature of atoms, molecules, and the emission and absorption of light--the core of what we now know as quantum theory--than he did about relativity.

A compelling blend of physics, biography, and the history of science, Einstein and the Quantum shares the untold story of how Einstein--not Max Planck or Niels Bohr--was the driving force behind early quantum theory. It paints a vivid portrait of the iconic physicist as he grappled with the apparently contradictory nature of the atomic world, in which its invisible constituents defy the categories of classical physics, behaving simultaneously as both particle and wave. And it demonstrates how Einstein's later work on the emission and absorption of light, and on atomic gases, led directly to Erwin Schrödinger's breakthrough to the modern form of quantum mechanics. The book sheds light on why Einstein ultimately renounced his own brilliant work on quantum theory, due to his deep belief in science as something objective and eternal.

A book unlike any other, Einstein and the Quantum offers a completely new perspective on the scientific achievements of the greatest intellect of the twentieth century, showing how Einstein's contributions to the development of quantum theory are more significant, perhaps, than even his legendary work on relativity.

by A. Douglas Stone (no photo)

by A. Douglas Stone (no photo)Synopsis:

Einstein and the Quantum reveals for the first time the full significance of Albert Einstein's contributions to quantum theory. Einstein famously rejected quantum mechanics, observing that God does not play dice. But, in fact, he thought more about the nature of atoms, molecules, and the emission and absorption of light--the core of what we now know as quantum theory--than he did about relativity.

A compelling blend of physics, biography, and the history of science, Einstein and the Quantum shares the untold story of how Einstein--not Max Planck or Niels Bohr--was the driving force behind early quantum theory. It paints a vivid portrait of the iconic physicist as he grappled with the apparently contradictory nature of the atomic world, in which its invisible constituents defy the categories of classical physics, behaving simultaneously as both particle and wave. And it demonstrates how Einstein's later work on the emission and absorption of light, and on atomic gases, led directly to Erwin Schrödinger's breakthrough to the modern form of quantum mechanics. The book sheds light on why Einstein ultimately renounced his own brilliant work on quantum theory, due to his deep belief in science as something objective and eternal.

A book unlike any other, Einstein and the Quantum offers a completely new perspective on the scientific achievements of the greatest intellect of the twentieth century, showing how Einstein's contributions to the development of quantum theory are more significant, perhaps, than even his legendary work on relativity.

Tunnel Visions: The Rise and Fall of the Superconducting Super Collider

by Michael Riordan (no photo)

by Michael Riordan (no photo)

Synopsis:

Starting in the 1950s, US physicists dominated the search for elementary particles; aided by the association of this research with national security, they held this position for decades. In an effort to maintain their hegemony and track down the elusive Higgs boson, they convinced President Reagan and Congress to support construction of the multibillion-dollar Superconducting Super Collider project in Texas—the largest basic-science project ever attempted. But after the Cold War ended and the estimated SSC cost surpassed ten billion dollars, Congress terminated the project in October 1993.

Drawing on extensive archival research, contemporaneous press accounts, and over one hundred interviews with scientists, engineers, government officials, and others involved, Tunnel Visions tells the riveting story of the aborted SSC project. The authors examine the complex, interrelated causes for its demise, including problems of large-project management, continuing cost overruns, and lack of foreign contributions. In doing so, they ask whether Big Science has become too large and expensive, including whether academic scientists and their government overseers can effectively manage such an enormous undertaking.

by Michael Riordan (no photo)

by Michael Riordan (no photo)Synopsis:

Starting in the 1950s, US physicists dominated the search for elementary particles; aided by the association of this research with national security, they held this position for decades. In an effort to maintain their hegemony and track down the elusive Higgs boson, they convinced President Reagan and Congress to support construction of the multibillion-dollar Superconducting Super Collider project in Texas—the largest basic-science project ever attempted. But after the Cold War ended and the estimated SSC cost surpassed ten billion dollars, Congress terminated the project in October 1993.

Drawing on extensive archival research, contemporaneous press accounts, and over one hundred interviews with scientists, engineers, government officials, and others involved, Tunnel Visions tells the riveting story of the aborted SSC project. The authors examine the complex, interrelated causes for its demise, including problems of large-project management, continuing cost overruns, and lack of foreign contributions. In doing so, they ask whether Big Science has become too large and expensive, including whether academic scientists and their government overseers can effectively manage such an enormous undertaking.

Books mentioned in this topic

Atoms and Ashes: A Global History of Nuclear Disasters (other topics)The Soul of Genius: Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and the Meeting that Changed the Course of Science (other topics)

Principia Mathematica, by Isaac Newton (other topics)

How Physics Makes Us Free (other topics)

Seven Brief Lessons on Physics (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Serhii Plokhy (other topics)Jeffrey Orens (other topics)

Isaac Newton (other topics)

J. T. Ismael (other topics)

Carlo Rovelli (other topics)

More...