Jack Cheevers's Blog

January 5, 2015

Welcome home, sailor

As a captive of North Korea in 1968, USS Pueblo crewman Don McClarren often had dreams of gorging on a porterhouse steak smothered in chocolate ice cream.

As a captive of North Korea in 1968, USS Pueblo crewman Don McClarren often had dreams of gorging on a porterhouse steak smothered in chocolate ice cream.Like the other 81 sailors who’d survived an attack on the U.S. spy ship by North Korean gunboats on Jan. 23, 1968, McClarren was taken ashore and tossed into a communist prison. There he and the others survived for the next 11 months on a starvation diet consisting mostly of rice and turnips. Occasionally, the men also got chunks of a smelly fish they called “sewer trout.”

But on Dec. 23, 2014 – 46 years to the day after he and the other Pueblo seamen were freed – McClarren finally got his steak and ice cream. It was served up by friends and family at a rollicking “welcome home” party at VFW Post 8851 in Boiling Springs, Pennsylvania, near Don’s home.

The party was a complete surprise to Don, who’s now vice president of the USS Pueblo Veterans Association ( www.USSPueblo.org ). When he walked into the VFW hall, his relatives and friends began cheering and waving American flags. Each white-linen-covered table had red, white, and blue carnations on it. On one side of the room were American, Navy, and POW flags; on the other side was a big “welcome home” sign.

“Don was stunned,” said Nikki Noll, who helped organize the party. “He stood there for about 30 seconds just looking around at everything.”

The post commander presented Don with a plaque recognizing him “for keeping the faith and not breaking under duress” – a reference to the torture, beatings, and other brutality that he and other crewmen endured at the North Koreans' hands. The inscription continued: “You survived captivity with honor and are an inspiration to us all.” (The plaque was placed in a permanent display case at Post 8851 along with a photo of Don and, I’m proud to say, a copy of “Act of War.”)

Several people gave speeches about Don and his Navy service, including his daughter Nina Klinger, a police officer. When Nina was finished, Nikki reports, “There was not a dry eye in the house.” Journalists from the local newspaper and a TV station covered the celebration. You can read the terrific news story at http://cumberlink.com/news/local/communities/boiling_springs/boiling-springs-vet-remembers-time-as-pow-and-returning-home/article_af30a4bc-8bb6-11e4-85e3-eb2878f3fccd.html

The next day, Don shared all the photos and links with other members of the Pueblo Veterans Association, saying that the homecoming wasn’t just for him but for all of them.

By the way, in the photo above Don isn’t giving his reaction to the party. He’s re-enacting the Pueblo crew’s famous “Hawaiian good luck sign.” When the captive Americans realized that the North Koreans didn’t understand the derisive gesture, they began flashing it whenever a communist propaganda camera was turned on them. They succeeded in ruining numerous propaganda photos and films until the communists learned, from Time magazine, what the finger salute actually meant. The Americans paid for the “good luck sign” and other resistance efforts when they were viciously beaten during what they called “Hell Week.”

And to this day they’re damn proud of flipping off the commies.

Published on January 05, 2015 18:26

January 2, 2015

Hello, Harrisburg!

On Monday, Jan. 5, I'll be doing a live interview with Scott LaMar, host of "Smart Talk" on WITF-FM, the National Public Radio outlet in Harrisburg, PA. We'll be talking about the USS Pueblo, its mission, the crew's brutal imprisonment in North Korea, and the Navy's treatment of the men after they came home on Christmas Eve, 1968.

On Monday, Jan. 5, I'll be doing a live interview with Scott LaMar, host of "Smart Talk" on WITF-FM, the National Public Radio outlet in Harrisburg, PA. We'll be talking about the USS Pueblo, its mission, the crew's brutal imprisonment in North Korea, and the Navy's treatment of the men after they came home on Christmas Eve, 1968. The 30-minute interview begins at 9:30 a.m. Eastern Time (6:30 a.m. Pacific). You can hear the program live at www.witf.org/listen.

The photo above shows the Pueblo in Wonsan harbor, after it was attacked and captured on Jan. 23, 1968. The ship was pinpointed by CIA pilot Jack Weeks flying a top-secret A-12 Blackbird aircraft. Built by Lockheed, the extraordinary A-12 could reach altitudes of 90,000 feet and speeds of up to three times the speed of sound. In the late 1960s, A-12s flew 29 spy missions over North Vietnam and North Korea as part of Operation Black Shield. Weeks's mission over Wonsan is described in Chapter 6 of "Act of War."

Published on January 02, 2015 15:46

Naval Historical Foundation reviews "Act of War"

My thanks to John Satterfield for his thoughtful and well written review, which follows. Dr. Satterfield, a former naval intelligence officer, teaches at Wilmington University in Delaware. The photo, by the way, shows the Pueblo's skipper, Pete Bucher, speaking with North Korean "journalists" at a staged press conference in 1968. His executive officer, Edward R. Murphy, is seated at left (with glasses).

My thanks to John Satterfield for his thoughtful and well written review, which follows. Dr. Satterfield, a former naval intelligence officer, teaches at Wilmington University in Delaware. The photo, by the way, shows the Pueblo's skipper, Pete Bucher, speaking with North Korean "journalists" at a staged press conference in 1968. His executive officer, Edward R. Murphy, is seated at left (with glasses). Reviewed by John R. Satterfield, DBA

This excellent history, drawn from 11,000 pages of previously classified or unexamined documents as well as memoirs and other more contemporaneous accounts, is an omnibus review of the 1968 Pueblo incident.

This volume is the culmination of more than a decade of research by a former Los Angeles Times political reporter using much material unavailable to earlier works on the affair published soon after its conclusion. It summarizes the facts of the case and incorporates many more peripheral but significant activities gleaned from other sources that shaped the outcome and implications of the ship’s seizure. Other essential books that cover various aspects of the story are Ed Brandt’s The Last Voyage of USS Pueblo (1969), the captain’s account, Bucher: My Story (1970), Trevor Armbrister’s A Matter of Accountability (1970), and Mitchell Lerner’s The Pueblo Incident (2002). Cheevers includes these findings and adds many new insights from his relentless digging.

Cheevers’s analysis shows that nearly everyone involved, up to the highest levels of U.S. military and intelligence command, acted inadequately, with little planning for contingencies. This conclusion is no real surprise, but Cheevers discloses extensive background on the military activity immediately after the ship’s capture and the months of diplomatic maneuvering that reinforce his overarching judgment. Early on, the Navy took a page from Stephen Decatur and considered sending a destroyer with carrier air cover into Wonson Harbor to recapture Pueblo and a Marine raid onshore to rescue the crew. It was clearly a hare-brained scheme destined to fail if actually carried out.

Intelligence capabilities are far more sophisticated today. Vessels like Pueblo, operating just outside territorial waters, are long since obsolete. At the time, however, coastal surveillance conducted by ships or aircraft were a necessary part of intelligence gathering. High-altitude reconnaissance aircraft, like the A-12 and SR-71, capable of Mach 2 and Mach 3 airspeeds, respectively, were too few in number and in too high demand to cover North Korea, not considered a global threat back then. Still, command authority ignored the real risk attached to Pueblo’s mission despite repeated Soviet attacks on U.S. snooper flights close to USSR territory near the Sea of Japan. The U.S. apparently also underestimated North Korea’s capacity for outrageous actions, even after several terrorist raids against South Korea and the attempted assassination of the South’s president just days before Pueblo’s hijacking.

The overriding aspect of the incident, so resonant in memory, was the fact that Pueblo surrendered without firing a shot, making it the first U.S. Navy ship to be taken by a foreign power in peacetime since the capture of USS Chesapeake in 1807.

Moreover, Pueblo was no ordinary ship. It carried a vast inventory of classified papers, studies, codebooks, and surveillance equipment. The NSA later described these as the worst security breach in U.S. history. Because he failed to fight his ship, the captain, CDR Lloyd “Pete” Bucher, faced a court of inquiry and a court martial recommendation, which was quickly squelched by the Secretary of the Navy. Cheevers argues forcefully, however, that the Navy placed Bucher and his crew in an untenable situation with no options if anything went wrong. To back up his claim, Cheevers found the only surviving copy of a White House study headed by former Undersecretary of State George Ball which found fault with the “planning, organization, and direction” of the entire operation by command authority.

The Pueblo crew’s courage was never in doubt, despite nearly a year of horrendous and continued abuse, torture, and starvation. They all signed confessions. Anyone subjected to such treatment would. To their credit, the 82 sailors consistently resisted their captors, most famously displaying middle fingers, explained as “Hawaiian good luck signs,” in many North Korean publicity photos and acted with deliberate insubordination that could have led to their executions.

Pueblo itself reflected the Navy’s shoestring level of support for activities unrelated to the Vietnam War. The ship was a small World War II-era Army freighter converted into an electronic and signals intelligence gathering vessel. Despite entreaties from Bucher, document destruction systems could not handle the volume of classified documents in an emergency, and the crew was inexperienced or inadequately trained. Pueblo was effectively defenseless; except for small arms, its only crew-served weapons were two .50-caliber machine guns, useless against the guns, cannons and torpedoes on the North Korean sub chaser and patrol boats that waylaid AGER-2, not to mention MiG fighters carrying missiles. Armament was absent because the Navy thought it might provoke a response. Bucher had clear responsibility to resist seizure, but doing so would have killed many if not all of those on board, in addition to the one sailor killed by cannon fire that forced Bucher to heave to. Even if the ship were sunk, North Korea could recover much of Pueblo’s classified information and equipment because sea depth was just 30 fathoms.

Pueblo’s seizure led to calls for retaliation nationwide, but President Lyndon B. Johnson had few real options for action. Within days, the Tet Offensive would disrupt the Vietnam War, shredding public support for the conflict and forcing Johnson’s withdrawal from the 1968 presidential election. Johnson quickly implemented diplomatic actions that kept the lid on South Korea, incensed by the North’s assassination attempt, and led to the crew’s release, two days before Christmas in 1968. American negotiators finally broke the impasse by agreeing to an apology that the U.S. renounced before signing it, a process Cheever documents in detail from contemporary memos and personal accounts.

Bucher and his crew returned to the U.S. as heroes, but the incident scarred many of them. Bucher, with no prospect of promotion, retired in 1973. He died in 2004 at the age of 76. Most of his shipmates left the service, many with crippling health issues after their time in captivity. North Korea today displays Pueblo as a Cold War trophy on the Taedong River in Pyongyang. The little ship remains in naval service, the second-oldest commissioned vessel in the U.S. Navy after USS Constitution, and will remain so until it is returned.

Dr. Satterfield teaches military history and served as a naval intelligence officer. Unfortunately, he is old enough vividly to remember the Pueblo incident.

http://www.navyhistory.org/2014/12/bo...

Published on January 02, 2015 15:11

November 28, 2014

"Act of War" out in paperback

I'm happy to report that the paperback edition will be available in book stores on Tuesday, Dec. 2. It features the same terrific cover design as the hardback, and fixes a few typos and factual errors (my thanks to sharp-eyed Goodreads reviewer Stephen Boiko for pointing out that the long-ago chairman of the House Armed Services Committee was L. Mendel Rivers, not Mendel Rivers). And all for just sixteen bucks! A gold burst on the front cover notes that "Act of War" is the winner of the 2014 Samuel Eliot Morison Award for Naval Literature. And the enthusiastic cover blurb is from my old Los Angeles Times colleague (and mega-successful mystery novelist) Michael Connelly. I just missed Mike earlier this month when he stopped off at Book Passage in the San Francisco Ferry Building to read from his latest book, "The Burning Room." So I'll use this opportunity to thank him for his much-appreciated support for "Act of War." Thanks, Mike!

I'm happy to report that the paperback edition will be available in book stores on Tuesday, Dec. 2. It features the same terrific cover design as the hardback, and fixes a few typos and factual errors (my thanks to sharp-eyed Goodreads reviewer Stephen Boiko for pointing out that the long-ago chairman of the House Armed Services Committee was L. Mendel Rivers, not Mendel Rivers). And all for just sixteen bucks! A gold burst on the front cover notes that "Act of War" is the winner of the 2014 Samuel Eliot Morison Award for Naval Literature. And the enthusiastic cover blurb is from my old Los Angeles Times colleague (and mega-successful mystery novelist) Michael Connelly. I just missed Mike earlier this month when he stopped off at Book Passage in the San Francisco Ferry Building to read from his latest book, "The Burning Room." So I'll use this opportunity to thank him for his much-appreciated support for "Act of War." Thanks, Mike!

Published on November 28, 2014 15:24

November 16, 2014

"Act of War" wins history book award!

I couldn't be happier -- or more amazed -- by this. "Act of War" has won the 2014 Samuel Eliot Morison Award for Naval Literature. The award is named for the Harvard historian who wrote an astonishing 57 books in his lifetime, twice winning the Pulitzer Prize. Professor Morison's books included excellent biographies of John Paul Jones and Christopher Columbus, along with a 15-volume history of the U.S. Navy in World War II. The Morison Award is given out by the Naval Order of the United States, a venerable group devoted to encouraging research and writing of American naval history. I received the award at a terrific dinner in New York City sponsored by the Naval Order's New York Commandery. I'm very proud and deeply humbled to be chosen for the Morison prize, whose past winners include former Navy Secretary John Lehman ("On Seas of Glory"); Marine Lt. General Victor Krulak ("First to Fight"); and Captain Edward L. Beach, whose gripping book, "Run Silent, Run Deep," was turned into one of the best submarine movies of all time. The award dinner at the New York Racquet & Tennis Club was a blast, and it was a real pleasure to meet the Commandery's members, including Commander Don Schuld; Bill Schmid, co-chairman of the book award committee; and Admiral Joe Callo, himself a past Morison Award winner.

I couldn't be happier -- or more amazed -- by this. "Act of War" has won the 2014 Samuel Eliot Morison Award for Naval Literature. The award is named for the Harvard historian who wrote an astonishing 57 books in his lifetime, twice winning the Pulitzer Prize. Professor Morison's books included excellent biographies of John Paul Jones and Christopher Columbus, along with a 15-volume history of the U.S. Navy in World War II. The Morison Award is given out by the Naval Order of the United States, a venerable group devoted to encouraging research and writing of American naval history. I received the award at a terrific dinner in New York City sponsored by the Naval Order's New York Commandery. I'm very proud and deeply humbled to be chosen for the Morison prize, whose past winners include former Navy Secretary John Lehman ("On Seas of Glory"); Marine Lt. General Victor Krulak ("First to Fight"); and Captain Edward L. Beach, whose gripping book, "Run Silent, Run Deep," was turned into one of the best submarine movies of all time. The award dinner at the New York Racquet & Tennis Club was a blast, and it was a real pleasure to meet the Commandery's members, including Commander Don Schuld; Bill Schmid, co-chairman of the book award committee; and Admiral Joe Callo, himself a past Morison Award winner.

Published on November 16, 2014 19:50

October 28, 2014

Ask me anything!

Well, almost anything. I'll be answering your questions about my new book on the USS Pueblo incident, my writing process, and anything else that strikes your literary fancy. You can submit your questions on this page, in the "Ask the Author" block above. Cheers, Jack

April 9, 2014

Radio interviews in April

I'll be doing live interviews with radio stations in Boston (go Sox!) and St. Louis in April. Please listen in and call with any questions you may have. The schedule is below. (Interestingly, one of the radio hosts has a close connection to this photo of Pete Bucher holding up his Prisoner of War Medal at a 1990 awards ceremony in San Diego. Bucher had to fight the Pentagon after it initially denied the medals to him and his men. But the skipper, who never forgot his sailors, eventually won the struggle, as I relate in the last chapter of "Act of War.")

I'll be doing live interviews with radio stations in Boston (go Sox!) and St. Louis in April. Please listen in and call with any questions you may have. The schedule is below. (Interestingly, one of the radio hosts has a close connection to this photo of Pete Bucher holding up his Prisoner of War Medal at a 1990 awards ceremony in San Diego. Bucher had to fight the Pentagon after it initially denied the medals to him and his men. But the skipper, who never forgot his sailors, eventually won the struggle, as I relate in the last chapter of "Act of War.")BOSTON - WEDNESDAY, APRIL 23

6:05 p.m. Pacific Time (9:05 p.m. ET)

WBZ NewsRadio 1030. Dan Rea, host of "NightSide," will interview me and possibly a former Pueblo crewman for one hour. (Dan, a veteran Boston journalist, introduced Bucher to a Massachusetts congressman, Nicholas Mavroules, who called the Navy on the carpet over the POW medals.)

ST. LOUIS - THURSDAY, APRIL 24

8:35 a.m. PT (10:35 a.m. CT)

KMOX NewsRadio 1120. Longtime talk-show host Charlie Brennan will interview me for a half hour.

Also, on April 25, I'll be taping an interview with Janice Hermsen, host of "The Book Hound" on Fox News Radio in Reno, Nevada. Not sure when this will air but I'll keep you posted.

Published on April 09, 2014 23:31

March 28, 2014

El Paso Times gives "Act of War" a nice writeup

Lessons from the Pueblo: Interviews, details put human element into political incident

Lessons from the Pueblo: Interviews, details put human element into political incidentBy Ramón Rentería / El Paso Times

POSTED: 02/16/2014 12:00:00 AM MST

Many young Americans probably have never heard of the USS Pueblo and its capture by North Korea more than 45 years ago.

The Navy vessel's history is often forgotten or neglected except by its crew, their families and persistent writers like Jack Cheevers, a former Los Angeles Times political writer now living in Oakland.

Cheevers recently published "Act of War: Lyndon Johnson, North Korea and the Capture of the Spy Ship Pueblo" (Penguin Group). The book is billed as the riveting saga of a Navy commander and his men, imprisoned for 11 months in North Korea and subjected to merciless torture.

"The loss of the Pueblo — which was jammed with sophisticated electronic surveillance gear, code machines, and top secret documents — turned out to be one of the worst intelligence debacles in American history," Cheevers writes in the prologue. "The ship's seizure pushed the United States closer to armed conflict on the Korean peninsula than at any time since the Korean War in the 1950s. And subsequent investigations by Congress and the Navy revealed appalling complacency and shortsightedness in the planning and execution of the Pueblo's mission."

Two El Pasoans — Donald R. Peppard, a first class petty officer, and Seaman Ramon Rosales — were aboard the "technical research ship," the only U.S. Navy ship still held captive by a foreign government and now used as a museum ship. Over the years, both men have described the disastrous voyage and their experiences under North Korean captivity.

North Korean patrol gunboats attacked and captured the Pueblo on Jan. 23, 1968. One crew member was killed and the remaining 82 were detained. North Korea claimed and the United States denied that the ship invaded its territorial waters.

The seizure made headlines across the United States and the world. But the so-called Pueblo incident was perhaps often overshadowed by other major news: the Vietnam War, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., civil rights marches and unrest, and the murder of Robert F. Kennedy while campaigning as a presidential contender in California.

Cheevers stumbled onto a 1970 memoir written by Lloyd M. Bucher, the Pueblo's captain and an ex-submarine officer, while browsing for something to read at a coffeehouse in Venice, Calif. He then spent years doing research and interviewing more than 50 people, including Bucher, crewmembers and U.S. officials.

Cheever also mined declassified federal documents and added fresh details to a story that had previously been told in a movie and earlier books.

"One important question I haven't been able to answer is exactly what motivated North Korea to seize the Pueblo," Cheevers writes. "My speculation is that North Korean dictator Kim Il Sung simply couldn't resist the opportunity to harass and humiliate the United States, while simultaneously diverting its attention and military resources from the Vietnam War."

Bucher argued in subsequent congressional and Navy inquiries that the ship was ill-equipped to defend itself or destroy classified materials. He said his superiors resisted his demands to better outfit the spy ship.

Cheevers points out that while the American public saluted Bucher and his crew as heroes, the Navy tried to paint the captain as a coward for surrendering the ship without firing a shot.

More than 45 years later, North Korea — with a new, young leader determined to embrace nuclear weapons — still poses a dangerous threat to stability and peace in Northeast Asia.

Cheevers argues that the Pueblo's core mission of gathering intelligence still matters as the United States continues to try to better understand its foes and their strengths and weaknesses. But it is the human element, the crew's brave attempts to resist their sadistic captors and Cold War tension, that makes this well-researched book worth reading.

"As we unleash spies and covert operations against a growing list of twenty-first-century adversaries, we'd do well to remember the painful lessons of the Pueblo," Cheevers writes.

Ramón Rentería may be reached at 546-6146.

Published on March 28, 2014 18:13

March 2, 2014

The Washington Times reviews "Act of War"

BOOK REVIEW: Seizing the Pueblo in an act of war

BOOK REVIEW: Seizing the Pueblo in an act of warBy Paul Davis - Special to The Washington Times

ACT OF WAR: LYNDON JOHNSON, NORTH KOREA AND THE CAPTURE OF THE SPY SHIP PUEBLO

By Jack Cheevers

NAL Caliber, $27.95, 448 pages

I was a high school student in 1968 eagerly waiting for my 17th birthday in 1969 so I could enlist in the U.S. Navy when the USS Pueblo was captured by the North Koreans. I recall that I was angry with the communists for taking the Pueblo, and I was especially angry with President Johnson for doing so little to rescue the ship and the crew.

Reading Jack Cheevers’s “Act of War: Lyndon Johnson, North Korea and the Capture of the Spy Ship Pueblo” rekindled my earlier anger — and then some.

Mr. Cheevers's book recounts the famous Cold War drama in January 1968 when a 176-foot electronic intelligence ship, equipped with tall antennae rather than top guns, and manned by a youthful crew of 83, was captured by North Korean patrol boats off the coast of Wonsan.

When the Pueblo’s commanding officer, Cmdr. Lloyd “Pete” Bucher, tried to sail away, the spy ship was pursued by the patrol boats. The patrol boats opened fire with shells and machinegun fire, killing one American sailor and wounding 10 others. Bucher felt he had no choice but to heave to and allow the North Koreans to board the Pueblo. The North Koreans took the crew prisoner and took control of the U.S. spy ship.

“Act of War” goes on to tell the horrific story of the crew’s brutal treatment by North Korea and the crew’s heroic — and humorous — efforts to survive while resisting the communists as much as possible.

Mr. Cheevers describes Bucher as an ex-submarine officer and a superb navigator and ship handler. He was a voracious reader and chess player as well as a heavy drinker, party animal and barroom brawler. A friend called him an “intellectual barbarian.”

Bucher was not a novice to the world of intelligence. He served aboard submarines that eavesdropped on the Soviet Navy. Although he hoped for command of a submarine, he was assigned to command the Pueblo. In conjunction with the Navy, the National Security Agency (NSA) assigned specific eavesdropping targets.

The Pueblo, described by one Navy officer as looking like the supply ship in the film “Mr. Roberts,” was to be home-ported in Japan, within cruising range of three potential wartime foes: the Soviet Union, China and North Korea. Prior to taking command, Bucher’s briefers at the NSAand the Navy Security Group told him not to worry about the ship being harmed. His best protection, they said, was the centuries-old body of international law and custom that guaranteed free passage on the high seas.

They were wrong.

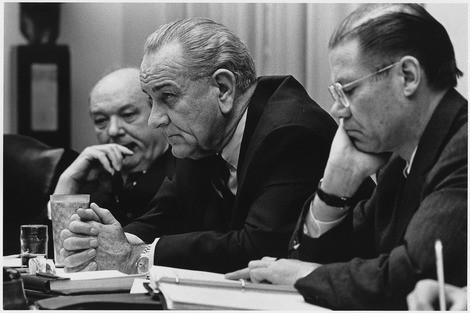

Mr. Cheevers gives the reader a seat back along the wall in the White House meetings held in response to the hijacking.

“Gathered now in the Cabinet Room, LBJ and his men tried to fathom the meaning of the seizure and devise a suitable response,” Mr. Cheevers writes. “They faced a minefield of dangerous unknowns. Why had North Korea grabbed the spy ship in the first place? Were the Russians involved in planning or executing the operation? Now that the North Koreans had the vessel and crew, what were they likely to do?” CIA Director Richard Helms saw Moscow’s fingerprints on the hijacking. He believed the Soviets had colluded with North Korea to divert Washington’s attention from Vietnam … . More ominously, a Romanian source had told the CIA that the North Koreans wanted to open a ‘second front’ on the Korean peninsula to tie up U.S. forces that otherwise could be deployed to Vietnam.”

“This is a very serious matter,” Helms told the president.

Mr. Cheevers later quotes LBJ adviser Clark Clifford as saying that although he felt sorry for the ship and crew, he didn’t think it was worth a resumption of the Korean War.

Mr. Cheevers also informs us that less than 48 hours before the Pueblo’s capture, North Korean commandos had attempted to assassinate South Korea’s president in Seoul. The assassination attempt and the taking of the Pueblo had the North and South Koreans poised for war with each other, which would draw the 50,000 U.S. troops stationed in South Korea into the conflict.

Although President Johnson ordered U.S. ships and aircraft off the North Korean coast and talked tough in public, he secretly negotiated with the North Koreans for a peaceful solution.

The last part of “Act of War” deals with the Navy’s inquiry of the incident, with some Navy brass placing most of the blame on Bucher. However, the general public proclaimed Bucher and his crew to be heroes. I suspect readers of “Act of War” will as well.

Paul Davis, a Navy veteran who served on an aircraft carrier during the Vietnam War, is a writer who covers law enforcement, intelligence and the military.

Published on March 02, 2014 20:02

February 16, 2014

The Economist's "Banyan" blogs about "Act of War"

(Note: Banyan is the pen name of Simon Long, a Singapore-based columnist for The Economist who specializes in Asia.)

(Note: Banyan is the pen name of Simon Long, a Singapore-based columnist for The Economist who specializes in Asia.)North Korea and the Pueblo

Gangster regime

Feb 15th 2014, 8:52 by Banyan

HIGH on the agenda of John Kerry, America’s secretary of state, as he paid brief visits to Seoul and Beijing this week, was the perennial headache of how to deal with North Korea. It is probably small consolation that at least things are not as bad as they were in 1968. That was the year North Korea seized an American spy ship, the USS Pueblo, killing one crew member and torturing the 82 others it held hostage for nearly a year.

A fine new book, however, “Act of War: Lyndon Johnson, North Korea and the capture of the spy ship Pueblo”, is a reminder also of how little fundamental has changed in the North Korean regime since then. It is still not so much a rogue state as a gangster one, which maintains its power with unmatched brutality at home and sets its own rules abroad.

The book, by Jack Cheevers, a former reporter for the Los Angeles Times, is based on extensive interviews with the crew and others involved in the disaster and on newly declassified material. It is in part a painful human story of the suffering of the crew and in particular its captain, Lloyd M. (“Pete”) Bucher.

They endured terrible physical beatings at the hands of their captors and appalling conditions. And Bucher had to live with the humiliation of being the first American naval commander since 1807 to surrender his ship without a fight—and to a tinpot communist dictatorship, at that, with what Mr Cheevers calls “a bathtub navy”.

As a result North Korea gained access to a treasure trove of American secrets, which it presumably shared with its then ally, the Soviet Union. It was, nearly half a century before the revelations of Edward Snowden, what one historian of America’s National Security Agency called “everyone’s worst nightmare, surpassing in damage anything that had ever happened to the cryptologic community”.

The American debacle was the result of what seems extraordinary incompetence. The Pueblo “groaned under the weight of a small mountain of secret papers”, yet had no means of disposing quickly of them or of its state-of-the art electronic snooping kit. It was too lightly armed to defend itself, yet other ships and planes were too distant to come to its aid when it was hijacked off the North Korean coast. Just before the Pueblo arrived, North Korean radio had threatened “determined countermeasures” against American “spy boats”, and tension had risen when North Korean commandoes were intercepted in South Korea, on a failed mission to assassinate President Park Chung-hee. Yet the warning signs were ignored.

For North Korea, the affair was a triumph. Besides the intelligence windfall, it is still able to portray the capture as a triumph over the superpower, using the Pueblo as a tourist attraction. And it only freed the crew after receiving an abject and untrue American apology.

Two outrageous characteristics of North Korean behaviour in 1968 are still, as it were, official policy. One is a total disregard for international law. The Pueblo was in international waters. Since then North Korea has engaged in terrorist attacks against airliners and in third countries (such as Burma in 1983); in counterfeiting currency and smuggling drugs; in walking out of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty; and, as recently as 2010, in sinking a South Korean naval ship.

Another is the skilful use of the fear of unacceptable escalation to get its way. Lyndon Johnson, at the height of the Vietnam war, was reluctant to open a second front in Korea, fearing that reprisals against the North might provoke it to attack the South, or indeed encourage President Park to invade the North. Now the North’s primitive nuclear arsenal gives its blackmail another deterrent edge. What Mr Cheevers writes about 1968 remains true: that the real danger on the peninsula is “miscalculation by one side about how the other would react to a serious provocation”.

A third aspect of North Korean behaviour then, however, may no longer be tenable. Before signing the humiliating American apology that secured the release of the Pueblo’s crew, the Americans made clear in public that they thought it was nonsense. This did not matter to the North Koreans, since their own people need never know about the “pre-repudiation”.

In dealing with North Korea now it is some comfort to think that its leaders can no longer be so sure their control of information is so impermeable. But then again, that might actually make them even more intransigent.

(Picture credit: AFP)

Published on February 16, 2014 19:39