Heather B. Moore's Blog

August 25, 2025

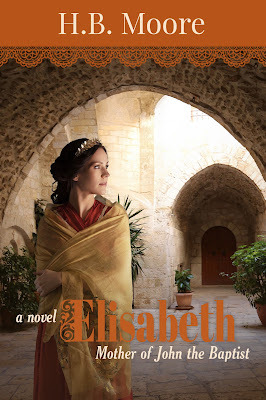

COVER REVEAL: Elisabeth: Mother of John the Baptist

So excited for this book to release!

Elisabeth: Mother of John the Baptist is coming this November. Preorder on Amazon!

SUMMARY:Her greatest sacrifice became her greatest legacy.

Zacharias has loved Elisabeth all his life. When negotiations are made for their marriage, the childhood friends trust that

their future will be bright. But as their story unfolds in their village near Jerusalem, the life they build together is marked by both the joy of love and the sorrows of loss and longing, for as the years pass by, the steadfast couple is never blessed with the thing they desire above all: a child.

Now beyond childbearing years, it seems that the couple’s righteous desire will never be granted—until a divine promise is made, and they learn that their fate will transcend the bounds of age and mortal comprehension. Elisabeth and Zacharias are destined to play a pivotal role in the fulfillment of ancient scripture, and they soon come to understand that God’s plan is far grander than they ever dreamed.

March 15, 2025

Julia: A Novel Inspired by the Extraordinary Life of Julia Child

My historical novel:

Julia: A Novel Inspired by the Extraordinary Life of Julia ChildReleases September 2025. Pre-order on Amazon.

It was an honor to write about the vivacious Julia Child. This biographical novel covers 20 years of Julia's life, starting in 1941. Julia served during WWII in the OSS, which was the precursor to the CIA. Julia's assignment took her to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and there she met her future husband, Paul Child. No, Julia didn't take cooking seriously until she was married. After some cooking classes, and many trials and errors, she dedicated herself to perfecting recipes. Once she moved to Paris with her husband for his work assignment, she promptly fell in love with French cuisine. There was no turning back for her. It would take her nearly ten years to see her coauthored cookbook, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, on the shelves. Her personality was larger-than-life, and after a guest television spot to promote her new cookbook, she was offered a cooking show series at a public television station, which would be known as The French Chef.

Summary:

Before she stepped into the spotlight as a master of French cooking, Julia Child navigated the shadows as a WWII intelligence officer.

On the sunny shores of California, Julia McWilliams is poised to embrace a life of comfort and financial security, with a marriage proposal from a wealthy man to consider. But as World War II erupts in the US, her patriotic fervor compels her to abandon her secure future. Trading country clubs for covert codes, Julia joins the Office of Strategic Services, where her sharp mind aids the Allied cause in the shadowy realm of espionage.

Amid strategic missions in Ceylon and China, Julia crosses paths with Paul Child, a fellow OSS officer whose delight in art, culture, and cuisine awakens a new hunger within her. Their chance meetings ignite a spark that blossoms into romance, leading to a proposal that Julia eagerly accepts. Together they embark on a new chapter in postwar Paris.

In the City of Light, Julia grapples with a different kind of challenge: she refuses to be confined by the societal expectations of a married woman. Drawn to the tantalizing world of French gastronomy—a pursuit her peers deem superfluous—she enrolls at the famed Le Cordon Bleu, and with Paul’s unwavering support, Julia immerses herself in her new passion.

Facing skepticism and prejudice in the male-dominated kitchens of Paris, Julia’s resolve never falters. Her relentless pursuit of culinary mastery not only transforms her own life but also introduces a revolutionary change in kitchens throughout America. From intelligence officer to beloved chef, this is Julia’s extraordinary journey.

Afterword

The pilots of The French Chef ran in August 1962, and Julia watched them at home on her new television. She wasn’t overly impressed with her performance but felt determined to learn from them. Despite her self-criticism of how she looked too large on camera and how she appeared breathless, not to mention her habit of closing her eyes, the letters from the public poured in—delighted with her genuine personality.

With the pilots deemed successful, the production of The French Chef began in February 1963, recording at the breakneck speed of four shows each week. The debut day of the new television program was Monday, February 11, 1963, on Channel 2 at 8:00 p.m. (see this episode on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@JuliaChildonPBS). Julia cooked the “perfectly delicious dish” of boeuf bourguignon (Dearie by Bob Spitz, 341). Julia might have been fifty years old, but her career was just beginning.

It didn’t take long for Julia Child to become a household name, and by the fourth show, WGBH-TV was receiving hundreds of letters a day from viewers. Affiliates included “KQED in San Francisco, WQED in Pittsburgh, WPBT in South Florida, WHYY in Philadelphia . . .” were just a few to start (Spitz, 346).

The attention and acclaim overwhelmed Julia, especially when people stopped her in public to tell her how much they loved the show. This only made her more determined to prepare to the smallest detail and perfect each episode, with Paul as her right-hand assistant. Paul once said, “These evenings, when other folk are at the movies or the symphony or lectures, find Julie and me in our kitchen—me with a stopwatch in hand, and Julie at the stove—timing various sections of the next two shows” (Spitz, 347).

From the beginning of her television appearances, Julia refused to participate in commercialism of products on her show since it was considered educational television. She didn’t want to feel forced to endorse any products or services. If she liked a product, she used it, plain and simple.

On a return trip to France, Julia and Simca fell back into their close friendship, and Julia approached the topic of writing a second cookbook that would eventually become Mastering the Art of French Cooking: Volume Two. This would, of course, be authored by only Julia and Simca. Louisette’s personal life had become very complicated, not only from her terrible divorce, in which her husband had incurred hefty debts and fled the country, but she was also dealing with arthritis in her hands, which made cooking difficult (see Spitz, 372).

Eventually, Julia proposed a buyout plan for Louisette. Julia was happy that Louisette was getting a royalty share in their book, but the contract also entitled Louisette and “her heirs the right to exploit and determine the future direction of the copyright, and that was not fine by Julia” (Spitz, 388–389). The agreed upon buyout amount was $30,000, and in exchange, Louisette would relinquish all contract rights to the book (see 389). This amount came out of the advance that Julia received for Mastering the Art of Cooking, Volume Two.

In planning out volume two, Julia reasoned that they’d eliminated so many excellent recipes when creating volume one that she and Simca already had a head start on a second volume. The new cookbook topped off at 555 pages, with seven sections, which included thirty-eight pages on modern equipment that hadn’t been available when the first volume was published (Appetite for Life: The Biography of Julia Child by Noël Riley Fitch, 360). Knopf published this second volume, releasing it October 22, 1970, with the first print run of 100,000 copies.

One of the most requested recipes that Julia received from her readers and viewers was for French bread. She’d attempted to make it plenty of times, of course, but she’d never truly succeeded. She would deflect her readers, saying that even in France, the French made a trip each day to the neighborhood boulangerie to buy their baguettes. But when editor Judith Jones made the request to include a French bread recipe in Mastering II, Julia could no longer brush it off. This led to a flurry of experiments, first conducted by Paul since Julia was entrenched in writing, and the recipe couldn’t be tested by Simca in France. It had to be a recipe that stood the test of American ingredients and American ovens.

Paul dove into what they called the “Great Bread Experiment” (Spitz, 382). His early attempts produced bread that was too hard and heavy and didn’t hit any of the requirements of the flawless crust, the right crumb, the delicious flavor, and the perfect color. Eventually, Julia joined Paul in the experiments, and between them, they had eighteen different methods they continued to tweak. It wasn’t until Julia and Simca arranged a tutorial session with Professor Raymond Clavel, a renowned authority on French bread, that Julia learned the secrets she’d so long been hunting for (see Spitz, 384). The final recipe? It was twenty pages long (see Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume Two, 54–74).

Throughout her television career, Julia received plenty of love and accolades as well as plenty of criticism. Cooking with wine on television was unheard of in the early 1960s, not to mention the audacity of a woman consuming alcohol on television. Over the years, and throughout many more cookbooks, Julia adapted and created recipes that would lend more to the health trends in America. Through it all, Julia stuck by her mantra of “moderation, moderation, moderation” (Spitz, 490) when she was scrutinized for the use of butter and other fats in her recipes. She called the naysayers against her French recipes “Nervous Nellies” (Spitz, 461), and she even adapted in later years by writing The Way to Cook, in which most of the main portions of the recipes were low calorie or fat-free (Spitz, 461).

For many years, Julia carried a proverbial weight of a culinary nemesis. Madeleine Kamman had issues with Julia that included claims—in criticism of The French Chef show—that Julia was “neither French nor a chef”—which, of course, Julia agreed with (see Fitch, 352). But the title of the television program was already set. And despite Julia and Kamman’s initial cordial friendship, Kamman took it upon herself to tell her students at her cooking school to destroy their copies of Mastering the Art of French Cooking and to never watch The French Chef (see Fitch, 352).

Kamman also loved to spread untrue rumors by telling industry professionals that Julia was retiring (see Spitz, 403). Julia had no trouble correcting Kamman’s misinformation and standing up for herself, but she was hurt that someone could be so vindictive. Julia got to the point where she refused to say the woman’s name anymore (see Spitz, 404).

After writing their second cookbook together, Julia and Simca didn’t coauthor again, but their friendship remained close. Julia and Paul spent most summers over the course of the next twenty-five years in France at La Pitchoune—a home they built on Simca’s property. The arrangement was that the Childs would pay for the construction and maintenance, but once they stopped using the home, it would revert to Simca’s family. The small house at La Pitchoune, completed in 1966, became a much needed refuge from Julia’s increasingly busy schedule.

In her later years, when Julia was involved in the 1993–1994 television series Cooking with Master Chefs, it was decided that the second series would be filmed in her own kitchen at 103 Irving Street. This suited Julia well and saved her from traveling so much. It turned her house into a film studio, per se, where Julia welcomed and hosted America’s chefs in her kitchen (watch the series here: https://www.youtube.com/@JuliaChildonPBS).

Paul’s decline in health came on gradually, and in 1974, he endured a series of nosebleeds, adding to other symptoms that had plagued him for some time, including chest pain and a constant ache in his left arm. He continued to brush off every symptom until he ended up at the hospital in October 1974 (see Spitz, 408–09). It was discovered that he needed bypass surgery. The surgery seemed to be successful, but his recovery was agonizingly slow, and new, troubling symptoms appeared. Paul’s speech had slurred, and he could no longer speak French. He had trouble moving and couldn’t stand straight. It was eventually determined that he’d suffered several strokes during his surgery.

Paul’s condition eventually improved, but he never made a full recovery. He could no longer serve as a support to Julia’s writing and traveling schedule, yet Julia insisted that Paul still accompany her in order to keep an eye on him, despite the challenges of his becoming increasingly forgetful and disoriented (see Fitch, 440–41). They were eventually able to resume their visits to La Pitchoune, but Paul had trouble reading and often asked Julia to read to him.

Unfortunately, while they were in France in July 1977, Freddie passed away from a heart attack (see Spitz 417). She was seventy-three years old. In 1981, determined to slow down in life, Julia and Paul bought a home on Seaview Drive in Montecito Shores in Santa Barbara (see Fitch, 416). It was a huge blow to Paul when his twin brother, Charlie, died in 1983. They’d been brothers and best friends for eighty-one years (see Fitch, 430). Another blow came when Simca died in December 1991 at the age of eighty-seven. Her death came as a grievous shock to Julia—her best friend and coauthor had been as close as a sister, and now nothing would be the same.

Although it was with a heavy heart, Julia finally had Paul move into an assisted-living facility, Fairlawn Nursing Home, in Lexington (see Spitz, 465). Paul’s confusion had returned, and his incidents of wandering and forgetfulness had become unmanageable without professional help (see Spitz, 485). Despite Julia’s grueling promotion schedule with another cookbook, she visited Paul every day that she was in Cambridge. Most of the time, he didn’t recognize her, but “she would climb in bed next to him and rub his head lovingly, filling him in on everything” (Spitz 470). She’d also call him every night, and she’d go along with whatever topic he wanted to talk about. Sometimes, he’d switch to fluent French—it seemed his language skills had returned (see Spitz, 471). Paul died May 12, 1994, at the age of ninety-two (see Spitz, 494).

In 2001, at the age of eighty-nine, Julia permanently moved to California, (see Spitz, 518). She agreed to donate her kitchen to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History: Kenneth E. Behring Center, located in Washington DC, on the National Mall. She donated her house to Smith College and her papers and cookbook collection to the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe (see Spitz, 519).

With Julia permanently relocated to California, she took on another cat—a kitten, this time, that she named Minou. Even though pets were not allowed in her Montecito complex, Julia insisted, “My cat’s not going to bother anybody” (Julia’s Cats: Julia Child’s Life in the Company of Cats by Patricia Barey and Therese Burson, 133).

September 16, 2024

Lady Flyer: The Remarkable True Story of WWII Pilot Nancy Harkness Love

Grab your copy here:

While researching and writing about the WASP aviators who served in World War II, it was interesting to discover that many of those I spoke to didn't know that women pilots flew war planes during that era. A few had heard of the British women ferrying pilots, and even fewer knew of the women who flew for the Soviet Union combat missions.On American soil, women pilots weren’t militarized, so their contributions came under the umbrella of civilian pilots. Even before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, there was a pilot shortage as the US was frantically building and sending aircraft across the Atlantic to support the Allied forces. Two women, Nancy Harkness Love and Jacqueline Cochran, worked tirelessly to propose solutions to fill the pilot shortage. Their vision included establishing a women’s pilot organization that would ferry planes from the manufacturers to airfields, freeing up the men to train and prepare for combat missions.

Beginning in 1940, Nancy Love persisted in her agenda at home while Jacqueline Cochran headed to England to join the British ATA Civilian Ferry Pilot Program that allowed women to ferry planes as part of the war effort.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, and after the US declared war on Japan and the Axis powers, over 100,000 men and women enlisted in the military. Eventually 50 million of 132 million Americans became employed in the war effort, working for the government, and women entered the workforce as never before.

Nancy Love had a remarkable vision—one she didn’t give up on. Her perseverance and leadership became the catalyst to demonstrating how women could be integrated into and valued in the Army Air Forces as pilots. Nancy wanted to see female pilots given opportunities to serve their country, and though her vision did not become widespread in the 1940s, with persistence, she became a trailblazer.

Starting in 1940, Nancy Love waded through nearly two years of setbacks before Colonel William H. Tunner approved her idea of hiring women pilots to ferry planes for the Ferrying Command, a division of the Army Air Corps—picking up the planes at the manufacturing plants, then delivering them to air bases around the country, plus other ferrying duties. This filled in the gaps that male pilots created when they left to fly combat missions.

When Nancy Love’s program was finally approved in 1942, the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS) quickly filled with twenty-eight hand-selected women pilots, who were called the Originals. These women came from various backgrounds, but all were well-qualified to transition to the larger planes and bombers coming off the assembly lines.

Jacqueline Cochran, returned from Europe, headed up the Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD), which trained and qualified additional women pilots to join the Women’s Ferrying Program. By August 1943, the WAFS had increased to over 225 women strong. That same August, Love’s WAFS combined with Cochran’s WFTD to become the WASP (Women Airforce Service Pilots). See: https://cafriseabove.org/nancy-harkne...

During the nearly sixteen months of the WASP Program, more than 25,000 women applied for training. Of those, 1,879 candidates were accepted into the Training Program, which was moved from the Houston Municipal Airport to Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas. Only 1,074 women successfully graduated. See: https://www.army.mil/women/history/pi...

The WASP pilots spent 1942–1944 flying every type of combat plane and delivering 12,650 aircraft to seventy-eight different bases throughout the nation while logging in more than 60 million flight miles.

Women became the backbone of the progression of the war and the eventual Allied victory. They worked in factories, building aircraft, and as airplane mechanics at Army Air Corps bases. Thanks to the persistence of Nancy Love and Jacqueline Cochran, women ferried the war planes from the manufacturing floors to the airbases, where women also worked as instructors for male pilot trainees. In addition, women flew the towing targets for male combat pilot training, and they tested out planes with mechanical issues.

Nancy Love firmly believed that if women didn’t learn to fly multiengine war planes, it would create a bottleneck between the production line and ferrying the planes to the airfields. She took it upon herself to set the example that women could fly the larger, more complex aircraft. She qualified on virtually all the Army Air Force’s combat aircraft, including the P-51 Mustang, P-38 Lightning fighters, C-54 transport, B-17 Flying Fortress, Consolidated B-24 Liberator, and the B-29 Superfortress. Nancy became the trailblazer for many of the WASP pilots and future pilots who would follow in her footsteps. See: https://cafriseabove.org/nancy-harkne... and https://www.thisdayinaviation.com/tag...

With the war coming to an end and male pilots returning home, authorities viewed the need for a women pilots as obsolete, and the 1944 push for the WASP to militarize was

Nancy’s belief in herself and other women pilots never faltered. Through many setbacks of family tragedy, a world war, constant obstacles and roadblocks to earn trust for women pilots, and health challenges, Nancy continued to push forward, soaring higher in order to make the path smoother for female pilots in the future.

September 1, 2024

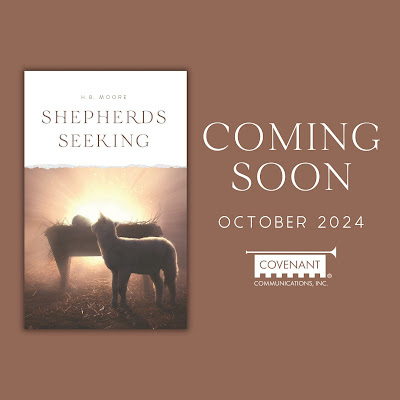

Shepherds Seeking: Coming in October

I'm looking forward to this short booklet, Shepherds Seeking, coming out in October! It was a special story to write and imagine how a shepherd might be influenced living in Christ's day and meeting the Shepherd Himself.

Pre-order on Amazon here. Summary:As young Elias shepherds his flock among the hills of Bethlehem, he enjoys contemplating the words of the prophets he once studied at the synagogue. But when a new star appears in the sky over the field, the scriptures are illuminated as never before. The Savior, born in humble circumstances, becomes a touchstone throughout Elias’s life as he records every account of Jesus of Nazareth. Perhaps no one will read the words of a lowly shepherd, but Elias does not seek recognition—his personal witness of the miraculous life and legacy of the Good Shepherd is enough.

March 25, 2024

Rebekah and Isaac: A Biblical Novel

Coming July 2024!

Add to Goodreads

Pre-order on Amazon

Author’s Note

Through conversations with my father, S.Kent Brown, and Dr. Kerry Muhlestein, in addition to reading several books andwatching podcast discussions on Abraham’s family, which included insights fromCamille Fronk Olson and Dr. Daniel Peterson, I discovered my first impressionsof reading the applicable chapters in Genesis were quite wrong. Not everyonehas the interest or ability to dive deep into a particular ancient family’slives, and I appreciate the scholars and historians who carve out the path forme when I’m working on a historical novel.

Among historians and scholars, there isdebate on some of the details of biblical events and dates. Muhlestein statesthat Abraham was born about 1943 BC, which places his adult life in the middleof Egypt’s Middle Kingdom (From Creation to Sinai by Daniel L. Belnapand Aaron Schade, 243). This paints a picture of the interactions thatAbraham had with the people of Canaan, as well as the Egyptians as theytraveled the caravan trails and occupied various cities over the decades.

Abraham and Isaac’s world would haveincluded trading with Egyptians since Beersheba and Hebron are along the traderoute to Egypt (ibid, 244, 249–250). They would have been exposed to the humantrafficking of slaves (ibid, 250), and of course the religious rites of multiplegods and human sacrifice (ibid, 252).

Abraham’s tribe was large, possibly around2,000 people in his community (ibid, 467). Histribe consisted of multi-generational households and multifamily clans (ibid,466), making Abraham’s personal household in thehundreds. We know that Abraham’s tribe had 318 men trained in combat, who wentto the aid of Abraham’s nephew Lot (see Genesis 14:14).

Interestingly enough, there’s a parallelbetween Abraham’s flight from Haran (see Genesis 12:1), andRebekah later leaving the same city and her family behind. Both did so at thebehest of Adonai.

Eliezer, who is mentioned as Abraham’s chiefservant and faithful steward, may or may not have been the servant who went insearch of a wife for Isaac (see Genesis 15:2; 24:2). Forstory purposes, I used Eliezer’s name and developed his character as theservant whom Abraham called upon for that very sacred task.

One hurdle I came across was whetherRebekah’s father, Bethuel, was alive at the time of Eliezer’s arrival andRebekah’s commitment to marry Isaac. Camille Fronk Olson points out that the ancientscholar Josephus believed that Bethuel had died, and this is why Rebekah runsto her mother’s house (or tent) to report the arrival of Abraham’s servant (seeWomen of the Old Testament by Camille Fronk Olson, 55; referencing Antiquitiesof the Jews by Flavius Josephus, 1.16.2). But in discussion with my father, he relatedthat women often owned their own tents in Bedouin society, so that wouldexplain why Rebekah named the family tent as her mother’s house. We also learnthat the handmaid Deborah is sent with Rebekah to Canaan, along with otherdamsels (see Genesis 24:59, 61; 35:8). This would be part of the bride price forRebekah.

Abraham lived as a nomad and didn’t stay inone place year after year. He traveled with the seasons to find the bestgrazing land for his cattle, herds, and flocks. Scholars believe that Canaanhad significant rainy seasons during Abraham’s lifetime, so the topographywasn’t as barren as we modern thinkers might believe (From Creation to Sinai,349–50). Muhlestein mentioned in a conference call thatIsaac was more sedentary than Abraham, and Jacob became more sedentary thanIsaac. This created a mixed nomadic lifestyle, in which they still lived out oftents but were increasingly sedentary.

According to Muhlestein, Abraham builtaltars of worship in locations such as Hebron, Beersheba, Bethel, and Shechem (ibid,346). When Abraham was asked to sacrifice Isaac,surely this was a repeated nightmare of when Abraham’s father attempted tosacrifice him. Child sacrifice was not uncommon in the ancient world, and itwas believed to be a form of worship to the god Molech (ibid, 364). Ofcourse, Abraham’s sacrifice was requested by Adonai and not false idolatry.

Now onto the difficult part of the story whereit’s hard to understand Abraham’s and Sarah’s actions toward Hagar when theysent her away. Hagar is Sarah’s slave—possibly from Egypt, although we do notknow with certainty. Due to Sarah’s barrenness, she enlists Hagar to bearchildren with Abraham, although the children will be born in Sarah’s name.

Hagar becomes pregnant, but living under therule of Sarah becomes intolerable, so she flees (see Genesis 16:6). Anangel of Adonai entreats Hagar to return to the tribe and reveals the blessingsthat will come her way, including naming her son Ishmael. Hagar then returns. WhenIsaac is born to Sarah years later, this displaces Ishmael. Although Ishmael ispromised the posterity of twelve princes and the future of a great nation and hiscovenant blessings are ensured because of Hagar’s return and Ishmael’s eventualcircumcision, he is not the birthright son (From Creation to Sinai, 472).

Tensions mount again between the two wives, andwhen Isaac is weaned (making him about three years old), an incident occursthat involves Ishmael mocking Isaac. This must be the last straw in a series ofevents because Sarah tells Abraham to “cast out this bondwoman and her son” (seeGenesis 21:10) much to Abraham’s grief. But when he inquiresof Adonai, He confirms Sarah’s decision, and reiterates that Ishmael willbecome his own great nation. Something that he couldn’t do living a subservientlife under Isaac’s future rule and birthright status.

Tradition states that to remove Hagar fromthe tribe, Sarah has every right to sell her back into the slave trade. ButSarah instead sets the woman free to live her own life, unencumbered by therule of Abraham and Isaac, which will, in turn, allow Ishmael to become his ownruler of a future nation (From Creation to Sinai, 413, 472, 474). Inthis way, Hagar is released from her marital obligation to Abraham. Her son,Ishmael, can now establish his own tribe and become the patriarch andforefather of the Ishmaelites in Islam.

Although Rebekah and Isaac’s marriage wascloser to an arranged marriage, since neither party knew each other before thebetrothal, Rebekah had full rights to accept or refuse the marriage offer. Thisis why we see Rebekah being consulted, even after her father and brother haveagreed to the betrothal (see Genesis 24:58 and From Creation to Sinai,477).

How long was the journey from Beersheba toHaran? Likely several weeks one way. Olson stated that the caravan would havespent at least a month on the trail (Women of the Old Testament, 51). Thecaravan would have been impressive with ten camels, perhaps ten men, travelingwith supplies and gifts. Olson also points out that Rebekah’s jar would haveheld maybe five gallons of water, and with ten camels who consume twenty-fiveto thirty gallons of water, she filled her jar about fifty times (ibid,51).

Rebekah likely heard of Abram, Sarai, andtheir story of leaving Haran. Rebekah wouldn’t have known much of what hadhappened after they left, so any news about Isaac would be new to her. Thepresentation of gifts by Eliezer to Rebekah and her family was essentiallysecuring the betrothal agreement, although I added an actual ceremony to thestory.

October 10, 2023

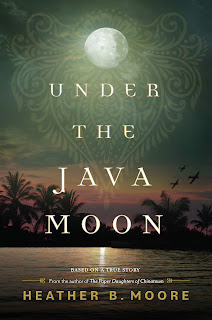

Under the Java Moon: now available

Photo: Heather & Marie Vischer Elliott (Rita), Aug 2021

In August 2021, I had the privilege of meeting Marie (Rita) Vischer Elliott for the first time when she traveled to my home state. My husband and I visited with her for a couple of hours, and she told us stories about her remarkable life in her lovely accent. Marie is now called Mary by family and friends, but I refer to her as Marie in this story for clarity. During our first meeting, Marie and I were both vetting each other. I wondered if I’d be able to do justice to a story that Marie had kept to herself for so many decades. She wondered if she was truly ready to share such private and difficult memories.

Marie told me that her family never spoke of the war after it ended. Her parents had wanted to fully move on. Years later, Marie ventured to ask her mother some questions, but her mother gave precious few answers. The topic was still considered a closed book to the past. Because of all that she’s endured, Marie never wanted to watch war movies or read about wars. She especially stayed away from stories about concentration or prison camps and their victims. Like her parents, she was keeping her past firmly behind her.

Yet, a slow change came over Marie in recent years, and she was surprised to realize that she wanted to share her past. She wrote up a brief summary of her experiences, and she began to tell her family about what had happened to her. The lock she’d kept on her memories and fears was slowly turned, then opened.

Marie’s remarkable story begins when she was a child, living in Indonesia (then called the Netherlands East Indies). Both her parents were originally from the Netherlands. Her father, George Vischer, who worked for the Royal Packet Navigating Company (KPM), was stationed on Java Island as his home base.

World War II left very few countries unscathed, and Marie’s family was divided up, then sent to live in Japanese prison-of-war camps after Japan invaded, conquered, and then occupied Indonesia. Marie, her mother, grandmother, and younger brother Georgie were sent to the Tjideng camp, which interned women and young children. Men and older boys were sent to their own camps. This began a period in Marie’s life that would shape her childhood, her future, and her beliefs.

Having read dozens of books about the World War II era over the years, I hadn’t ever read anything about the Dutch people’s experience in Indonesia. When I searched for books or films about the subject matter, I was only able to find self-published memoirs. I bought everything I could find and began to read.

I was already excited to write a historical novel about Marie’s early life just from what she’d shared with me in our first meeting, but I had no idea the impact of the war on Indonesia and its people until I dove deeper into research. Story after story, shared by former POW camp victims, revealed experiences long-buried. At the end of this novel is a list of the memoirs and other historical sources that helped frame this book.

As a backdrop to Marie’s story, it’s important to understand why Indonesia became an strategic asset to the Axis power of Japan during the war. Due to the oil embargos against the Axis powers, the oil fields that spanned the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) drew Japan to the islands since they were searching for mineral resources to fuel its war effort. To the Japanese, the Dutch colonies were a diamond in the Pacific.

In the early 1600s, the Dutch joined other traders such as the Spanish, Portuguese, British, Arabia, etc., bent on securing trade routes and trade posts throughout southeastern Asia and the Americas. In 1602, in order to establish a dynasty over other traders, the Dutch founded the world’s first multinational trading empire called the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) or Dutch East Indies Company. This began the next two centuries of the VOC running trading posts. When the VOC declared bankruptcy in 1796, the Netherlands government took over, and the Dutch colonization of the East Indies went into full effect. Over the next several decades, Dutch families moved to Java and Sumatra, seeking opportunities in private enterprise.

On the day that the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 (December 8 in the NEI), the NEI was spurred into action, and they declared war on Japan. Every Dutchman the age of eighteen or older was conscripted into one of the Royal military branches to undergo accelerated military training. Overall, the Dutch relied mostly on the Western Allied powers for help. But the Allies were busy defending other Pacific Rim countries such as the Philippines and Singapore, leaving the NEI vulnerable to attack.

Battles raged between Japan and the Dutch, on land and on sea, ending with the Battle of the Java Sea, in which the NEI and Allied fleet was soundly defeated. Three days later, Japanese forces landed on Java Island, and one week later, on March 8, 1942, the NEI governing body officially capitulated to Japan.

As a result, over 100,000 Dutch men, women, and children were funneled into prison camps. An additional 40,000 Dutch men became prisoners of war, many of them shipped to work camps in Burma, Japan, and Thailand.

The Dutch-Indonesians, or Indos, were caught in the middle. Descended from Dutch and Indonesian marriages, due to the decades of intermarriage from Dutch colonization, the Indos were given a choice: live in the prison camps or serve the new Japanese regime.

With the takeover of the NEI by the Japanese, everything related to the Dutch culture was replaced by Japanese culture. Even Batavia, the capital of the NEI, was renamed to Jakarta. The Japanese language was taught in schools, the Japanese calendar implemented, and local time became Tokyo time.

Over 6,000 of the 18,110 islands of the Indonesia archipelago are inhabited, and in 1941, the Dutch population made up most of the Europeans living throughout the islands. The total population of the NEI was about 60 million people. To understand the scope of the loss the Dutch people suffered throughout the prison camps in Indonesia, by the end of the war, 30,000 European internees had died, but even more sobering is that a total of four million civilians perished, which included Indonesians and Indo-Europeans, as a result of malnutrition and forced labor.

Under the Java Moon follows the story of Marie and her family, as they endured the hardships of living in a POW camp during World War II. At the end of February 1942, Marie’s father, George Vischer, fled for his life with a group of naval officers in order to join up with Australian Allied forces. On a fateful day in March 1942, Marie Vischer was ushered out of her home. Marie, her elderly grandmother, her mother, and toddler brother were forced into a women’s prison camp ran by the notoriously cruel Japanese commander, Captain Kenichi Sonei.

This is Marie’s story.

Available at most retailers!Book Club Kit available here.

September 3, 2023

Book Tour with Julie Wright

Join me and author Julie Wright!

Las Vegas, Nevada September 5th

12-1 Deseret Book

5750 Centennial Center Blvd

Upland, California Sept 6th

3-5 pm Ensign Books

1037 W Foothill Blvd Upland, Ca

Redlands, California Sept 7th

3-5 pm Ensign Books

700 E Redlands Blvd Ste 1 Redlands, Ca

Costa Mesa, California Sept 9th

11-1 pm Deseret Book

2200 Harbor Blvd Ste 8110 Costa Mesa, Ca

June 4, 2023

Salem Witch Museum--book signing

Bucket List. Check.

For several years, the Salem Witch Museum has been carrying paperback copies of the book I wrote about my 10th great-grandmother Susannah North Martin, CONDEMN ME NOT. I've long wanted to do a book signing there, and now I'll be heading to Massachusetts in a few weeks and signing at the Salem Witch Museum on June 22, 12-4:00 pm. Join me if you're in the area!

March 8, 2023

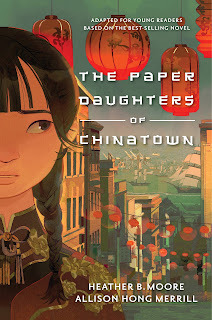

Spring 2023: Young Reader's Edition of The Paper Daughters of Chinatown

In 2019, I visited the Cameron House in San Francisco for the first time. Founded in 1874, originally established as the Occidental Mission Home for Girls, the Cameron House has a long history of bringing aid and relief to the community of Chinatown, (CameronHouse.org). My purpose in visiting was to learn more about the remarkable women who worked as volunteers in the early years, including former mission home director Donaldina Cameron, in preparation for writing the historical novel, The Paper Daughters of Chinatown (September 2020, Shadow Mountain). But one visit to the Cameron House, and I was deeply touched by the life and service of Tien Fu Wu.

In 2021, my publisher asked me to write a Young Readers version of The Paper Daughters of Chinatown. I hesitated because I was reluctant to go back into the depths of research that had brought me so much heartache. So I decided to read a few other YR versions of favorite books of mine. I discovered that most of them were either co-written or ghost-written. That gave me an idea. If I could share the emotional journey with a co-author while writing another version of this heart-wrenching story of what took place in San Francisco's Chinatown, then I would seriously consider it. The first writer who came to mind was Allison Hong Merrill. The minute I thought of her, I knew without a doubt, that she would be a stellar co-author. Allison had been my first reader of the original manuscript and had given me excellent insights. She'd also recently published a deeply personal memoir that left me grateful to have such a fierce and loyal friend.

Still, I was nervous to ask her because the deadline was pretty tight, and I needed her to be completely on board with not only the entire writing and editing process, but future marketing. I emailed Allison, and she replied almost immediately, even though she was flying in a small plane with almost nonexistent reception. Her resounding YES only confirmed I'd made the right choice. This was echoed over and over as we hammered out the plot and put together an intense writing and accountability schedule. We both agreed that the main character of this new version would be 6-year-old Tien Fu Wu. We kept part of the Donaldina Cameron story arc from the original book, but completely rewrote her chapters with a different focus. (So, yes, you can read both versions and come away with two stories.)

“Auntie Wu” or “Tien” as the residents of the mission home called her, was brought to Chinatown as a paper daughter in the late 1800s. A loophole in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 created a dubious opportunity for slave owners or members of the criminal tong to bring Chinese women into the country under false identities supported by forged paperwork. In this forged paperwork system, the young Chinese woman would memorize her new family’s heritage and claim to be married or otherwise related to a Chinese man already living and working in California, and the paper daughter was allowed into the country. “Upon arrival in San Francisco many such Chinese women, usually between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five, were taken to a barracoon, where they were either turned over to their owners or stripped for inspection and sold to the highest bidder” (see Unbound Feet by Judy Young, 27).

Such was Tien Fu’s experience. In the records from the Cameron House, we learn that Tien Fu was called Teen Fook or Tai Choi before her rescue. In an entry dated January 17, 1894, her rescue is detailed: “Tai Choie alias Teen Fook was rescued by Miss Houseworth, Miss Florence Worley and some police officers from her inhuman mistress who lived on Jackson St. near Stockton St. The child had been very cruelly treated—her flesh pinched and twisted till her face was scarred. Another method of torture was to dip lighted candlewicking in oil and burn her arms with it. Teen Fook is a pretty child of about ten years old, rosy cheeked and fair complexion” (see Chinatown’s Angry Angel by Mildred Martin, 46).

Adjustment to new life and expectations in the mission home wasn’t a simple road for any of the girls and young women, especially for Tien Fu. She harbored deep resentments for anyone who was in a position of power over her, but through the months and years of love and consistency, Tien Fu flourished and became an integral part of the mission’s work. She served as a translator for the mission home director, Donaldina Cameron, when they went on rescue work. Tien Fu wanted to continue contributing, to give back, and to serve those in need. She was determined to get a college education so that she could open more doors and serve in greater capacities in the mission home and throughout the community.

The mission home found a sponsor for Tien Fu’s education, and she spent four years in Germantown, Pennsylvania, and two years in Bible Training School in Toronto, Canada (Martin, 153). Before leaving San Francisco, she promised Donaldina Cameron that she would return to the mission home and continue to work for the cause. True to her word, Tien Fu returned to San Francisco and spent the remainder of her career as a champion for the women and girls of the Chinatown community. She truly lived a dedicated life in service, faith, and love as she persevered through extreme challenges, while lifting others with her along the way.

Add to GoodreadsBuy on Amazon

October 16, 2022

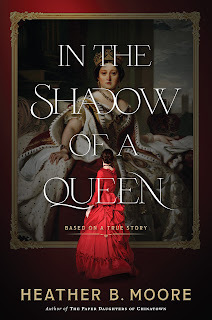

Now available: In the Shadow of a Queen

My interest in royal families dates back to the 1980s when I began reading about Queen Elizabeth I. Monarchies have always fascinated me. Queen Victoria became of particular interest to me when I learned more about her five daughters and the contributions they made to women’s causes throughout Europe by establishing schools and founding charities. Not only that, but her daughters also became the voice of the Crown. Queen Victoria relied on them to serve as her private secretaries while she battled with severe depression and kept her eldest son—and heir—at arm’s length.

More specifically, Princess Louise interested me because she deviated from the traditional path of royals during her era by marrying a commoner and pursuing the masculine career of a sculptor. One might consider the modern embodiment of Princess Louise to be Princess Diana, who was also committed to the downtrodden and redefined what it meant to be a royal.

My family lineage extends to British royalty, as does my husband’s, and I tried in vain to find a direct link with Princess Louise herself. There was no link since she didn’t have children, but my husband is a distant cousin to the Argyll family.

I spent a full six months researching and writing about Princess Louise. Even in the editing process, I was still discovering nuances and tidbits. Princess Louise might have been a member of the most prestigious royal family of her time, but she took a step back from glitter and glamour and found ways to positively impact the lives of others, even when the climb was straight uphill. She had a queen for a mother, and Louise’s voice was often strictly controlled and limited to what was considered acceptable for the era. Yet she managed to carve out a fulfilling life and push through barriers in order to achieve her hopes.

It was my honor to write her story.

For all things Queen Victoria & Princess Louise, join the Facebook page here.