Galadriel Coffeen's Blog

May 20, 2022

The Road Where Fruits Fell

“You recall how, when you gave me my robes, you told me you hoped I would find a student who taught me as much as I taught you?” Aphiros asked with a sidelong grin. “Well, I found one.” His grin felt at least halfway like a grimace.

“I’m glad to hear it,” the old man walking next to him said. He sidestepped around a pair of small children running down the road in pursuit of a ball, then resumed his calm pace beside Aphiros. He was definitely grinning, his laughter lines prominent around his green eyes. “The most challenging students are often the most promising.”

“Indeed,” Aphiros said, but he felt his smile slipping. He let it go. “She’s come to me for chimere work, but she’s mainly my captain’s student. Well, she was. We may lose her to a Grand Haias soon.”

“Promising indeed!” the old man said, but his smile had faded somewhat, too. “Why does that sadden you? A Grand Haias taking your student is a compliment.”

“It’s not that,” Aphiros said. He frowned absently over his old teacher’s head, only half-aware of the colorful shopfronts that lined the road. “Of course she would benefit from the tutelage of a Grand Haias. But she would be alone again. After four years aboard our ship, this past summer was the first time she didn’t seem so alone. But if she leaves us…”

“Alone?” the old man murmured. “And this is a bad thing?”

“Isn’t it?” Aphiros asked. He threw a sidelong glance at his teacher.

The older priest didn’t answer; he simply cupped his hand, and a pink sphere of magic appeared above his palm, growing to the size of a ripe orange. He held it sideways toward Aphiros without looking at him, and Aphiros slid his hand into place to receive it.

The magic tingled and buzzed against his palm, trying to break free of its shape, but Aphiros caught it with his own power. The shape solidified and darkened, taking on the crimson hue of Aphiros’ magic. They continued walking along the Road Where Fruits Fell. It was an old trade road that, despite being wide enough for two lamai carts to travel abreast, was considered too narrow for modern caravans. It had transformed over the years into a pedestrian road: all the old inns and corrals had been repurposed into craft schools and shops, small trees grew down the center of the road, and children too young to go to school played under the branches.

Aphiros’ former teacher liked walking this way because it led nowhere he or his students needed to go in a hurry. It was a good road to travel while reflecting on small problems that didn’t merit the rigors of the Four Desert Paths. The old priest also liked passing a sphere of magic back and forth while they were talking; the concentration needed to hold the magic in shape encouraged students to reflect more on how they truly felt about what they were saying.

They walked on for another twenty paces with Aphiros cradling the sphere of red light in his palm before his teacher asked, “Why is she alone?”

“Because she doesn’t trust anyone,” Aphiros answered immediately. He felt a sudden surge of power spring from his hand into the sphere. It pulsed outward unevenly, trying to escape into wild magic. Aphiros took a measuring breath to help him re-shape the sphere, now a little larger because of the power he’d inadvertently added. He realized that flash of magic had been born from a jolt of irritation. Was he irritated at Kelta for not trusting him?

He took another breath and let it out slowly as he reviewed his feelings and thoughts about Kelta. As he did so, he slowly passed the sphere of magic from one hand to the other in time with his steps. The rhythmic series of physical and magical motions kept him grounded as he sorted through what he felt and what he knew.

Yes, he was a little irritated at Kelta for not trusting him. After four years, he felt he’d earned at least a little trust from her, though he knew it wasn’t personal. She didn’t trust anyone.

“Trust comes from safety; distrust comes from fear,” he said aloud. So, if Kelta didn’t trust anyone it meant she felt fear around people.

That much was obvious in everything Kelta did, from the way she redirected conversations away from personal topics to the way she never ate or drank before anyone else. Ganat had tipped him off about that second habit, and he felt like an idiot for not noticing it before.

She chose to be alone. And that was what irritated him, he realized. It had been bothering him for a while now. After four years, she still chose not to trust him or anyone else on the ship. The crew had more than proven they had her back, but she held herself apart, deliberately thwarting all attempts to get to know her. Deliberately blocking Aphiros’ attempts to befriend and help her. He cared for her; when Ganat had introduced her as family, Aphiros had taken her into his heart as the cousin she claimed to be. So why did she choose to remain alone?

“I don’t know,” Aphiros admitted aloud. He held the magic out to his old teacher, who took it back. It resumed its original pink hue as they passed under a striped awning that stretched across the road. The spring sun was just warm enough to make walking in the shade pleasant.

“Then you don’t know if it’s a bad thing,” his teacher pointed out. “Solitude is not inherently unhealthy. In fact, many people could do with more of it.”

“If you met her, you would agree with me,” Aphiros muttered. “Kelta’s probably the most talented student I’ve ever seen. She’s not just a warrior, but a scholar, a musician, an artist, a keen thinker, brilliant at gathering intelligence. She could be an amazing diplomat, with the way she maneuvers people to get what she wants. But she refuses to make friends. She wears a very small family pattern. We only learned she was a musician when one of the other rohaiasi followed her ashore one night and caught her playing a flute by herself on an empty beach in the middle of the night.”

“It sounds to me as if she’s fighting to be alone because you won’t let her,” the old man snorted. He handed the sphere back to Aphiros; it changed back to red, then started straining against his control, trying to grow larger again. There was a trick to not letting emotions interfere with magic. The goal wasn’t stoicism, but holding a line between mind and heart.

“It must be hard to be alone on a ship,” the older priest continued. “And the minute Kelta tries to find that solitude, someone sneaks off and follows her. Is she ever truly alone, then?”

“Hm, you’re right,” Aphiros said, rolling the magic between his palms again. “She’s rarely alone at all on the ship. And when we go ashore, people usually try to drag her into some outing or other.” Aphiros had been guilty of that once or twice, he knew. “But she’s not surly or shy. She teaches drills and meditation; she even went well out of her way to bring that Ellondese on board.” Aphiros snorted slightly at the inevitable comparison between Kelta and the foreigner she’d recruited. “That young man told me more about himself in ten minutes than she has in four years.”

“While respecting the Ways of Silence, can you tell me why she came to you to learn the chimere dances?” the old man asked.

Aphiros paused for a moment, considering his words to ensure he wouldn’t reveal any of Kelta’s secrets. Not that she’d revealed many to him in the first place. He said carefully, “Her pain interfered with her duties.”

“Pain,” the old man repeated. “Is that the same as solitude?”

“She won’t share her pain, not even with me,” Aphiros said. He found he was gently stroking the ball of magic with his fingers, a soothing gesture. Beneath his irritation at Kelta’s aloofness, he recognized sadness, a deep sorrow over how lonely she must feel.

“Aphiros…” the old man said, and Aphiros looked sideways to see the compassionately accusing look on the old man’s face. “I didn’t ask about her this time, did I?”

“No, you didn’t,” Aphiros said with a rueful smile. He’d sidestepped around the real question. “Which suggests that the answer to your question is yes, I do seem to be using ‘alone’ to mean ‘in pain.’ But I know solitude isn’t a bad thing. In fact, I spent a lot of my childhood alone. Whenever I couldn’t play with cousin Ganat and his friends, I would play by myself in the ruins or along the empty beaches. Hours and hours by myself in tidepools and old temples…”

“Hours and hours avoiding the pain of being at home,” his teacher corrected gently. “Solitude was your last resort. You were lonely, not solitary, Aphiros.”

Aphiros said nothing for a long time. They passed a silversmith’s shop that echoed with the chime of small hammers and a bakery that wafted scents of honey and nuts. Aphiros kept stroking the magical sphere nestled in his palm and reflected on the old familiar feeling like cords wrapped tight around his chest.

With his irritation peeled back and his sorrow revealed, there was nowhere for him to hide his own pain. It had been easy for him to accept his favorite cousin’s invitation to go to sea. In fact, he’d accepted before Ganat had finished asking the question. As his old teacher had pointed out, it was hard to be alone on a ship as small as the Keltorax, where the crew functioned like a tightly-knit school.

“You said Kelta was Ganat’s niece,” his teacher said. “That makes her family, doesn’t it?”

Aphiros nodded. Aside from Ganat, he was the only member of the crew who knew that Kelta wasn’t actually related to the captain, at least not closely. But Ganat had introduced her to the crew as his niece, and Aphiros was Ganat’s cousin. As far as Aphiros was concerned, that made Kelta family. He didn’t know why Ganat had adopted her, and he hadn’t pressed when Ganat declined to explain. But that didn’t matter. She was family.

“She’s not like my father,” Aphiros murmured. “She doesn’t avoid the sight of me. I think she might even enjoy sparring with me, though it’s hard to tell if she enjoys anything. She kept coming to practice chimere with me even after her required month was up. Yet when she avoids sharing her pain with me it feels much like the days when the only words my father would say to me were ‘sit there and be patient.’ I wanted nothing more than to understand what he was working on, what was so important…but whenever I dared ask, or speak at all…” He winced at the memories. Being dismissed in that irritated tone hurt almost worse than the insults and slaps.

He trailed off as his thoughts started to uncoil into a neat progression. Kelta was family. Kelta kept fiercely to herself, and what she was keeping to herself felt vitally important and mysterious, just like his father’s work. Aphiros had never really gotten over the feeling that his father didn’t trust him with anything important. He’d told Aphiros a thousand times that he was too impulsive, too passionate, to be given responsibility.

“I think I chose the ketzoa school to prove my father wrong,” he sighed. “I got lucky; it matches my birth spirit well enough. But so does chimere. I could have succeeded at either, but I entered a school that develops determination and responsibility above all else, in order to prove I was trustworthy. So, naturally, my first student doesn’t trust anyone.”

“Naturally,” his teacher chuckled, and Aphiros’ grimace slowly relaxed into a rueful smile.

They walked in silence for a while longer, letting the dwindling streams of apprentices and shop-keepers trickle around them down side streets to their homes. The sun sank below the level of the temples on the hill across the city. Aphiros felt tension seeping out of his chest as they walked; the magical sphere stopped struggling against his control and relaxed, shrinking back to the size of an orange. Aphiros let out a long breath and released the sphere to his teacher again.

“So, are you still worried about your student leaving?” his teacher asked.

“I wish she wouldn’t,” Aphiros said. “But – no.” Recognizing his own feelings, acknowledging that his anxiety was about his past and not Kelta’s future, had lifted a weight from his shoulders. “I think I can let her go,” he said. “Apart from anything else, I have my hands full with that Ellondese mage. He’s convinced he’s not a ‘real’ mage, but he has more natural talent than I’ve ever seen before. He’ll either be one of the most powerful battle mages afloat, or blow the Keltorax into pieces by accident. Or possibly both.”

“Is he making progress?” Aphiros’ teacher asked curiously. “I assume he doesn’t even know our language. How can you teach someone so old and yet so…young?”

“He speaks Fosseni fluently,” Aphiros said. “And he’s a quick learner; he’s already picked up a good bit of Taxian. And he never gives up on an exercise – at least, not once he understands what the exercise is for. He hates the idea of being given make-work. But he’s advancing; he couldn’t hold even the smallest sphere of power when we met, but now he can carry one all the way to the fighting top!”

“A fellow ketzoa?” the old man asked.

“Drachon,” Aphiros snorted. “All enthusiasm and no discipline. He reminds me of Ganat when he was younger, just with magic added to the mix. It’s no surprise he found his way to our ship.”

Aphiros realized he was getting excited. It was hard not to, thinking about Wren’s growing exuberance for magecraft. What the young man wanted most from Aphiros – and Aphiros gathered it was a childhood longing never fulfilled – was to learn to throw fireballs. Aphiros wasn’t ready to let him try anything so dangerous, not for a while yet. Wren seemed to understand, but that didn’t stop him from boiling with impatience. He, too, would be a challenging student in his own way. And he wouldn’t hold Aphiros at a distance like Kelta did.

“Kelta will be fine,” Aphiros said. Whether she stayed or left, Aphiros had taught her what he could. Now it was up to her to use what she’d learned — and he felt confident that she would use it well.

He swiped the ball of magic from his teacher and launched it into the air. A few flicks of his fingers reshaped it into a tiny scarlet ketzoa, wings out-spread as it shot upward, then exploded in a shower of ruddy sparks. “The ketzoa gives its young wings,” Aphiros quoted an old proverb, “but they find the wind on their own.”

May 6, 2022

Translating Writer’s Block

Everyone who writes has experienced the dreaded writer’s block, when the words simply won’t come and the story won’t progress no matter how hard you try. It’s a common topic for discussion, and there are hundreds of tips out there for how to overcome writer’s block, but I’d like to posit a perspective that I’ve never seen in any of the articles or blog posts I’ve encountered. I believe that writer’s block is a positive thing.

Now, I don’t mean it’s good that I’m having trouble writing. But I don’t believe writer’s block is “just” trouble getting words on paper. I think it’s my mind’s way of getting my attention and telling me something isn’t right. And until I fix what’s gone wrong, it doesn’t matter how many tips and tricks I try for busting writer’s block: my mind will stubbornly refuse to keep producing words until I listen to what it’s trying to tell me.

In my experience, there are two messages my brain tries to deliver by means of shutting down the flow of words. First, and more obviously, “Take a break!” If I’ve been writing a great deal (or doing a lot of other creative output such as painting or sewing), I’ll hit a point where I still have ideas and still want to write, but my brain is too wrung out to produce anything worthwhile. If I keep trying anyway, my mind gets fed up with my refusal to rest and stops working to force me to take a break.

A lot of articles out there on beating writer’s block touch on this aspect and offer tips such as going for a walk, switching tasks for a while, taking a shower, etc. These are all valuable ways of taking a short rest, but sometimes (and this is a lesson I’m still struggling to accept) a short rest just isn’t enough. Sometimes I need to step away from my writing for a day, or a week, or even longer, before I’m recharged enough to jump back into the story. It’s easy to feel guilty about taking time away from writing, but I’ve found that any time I allow my mental energy instead of my sense of obligation to dictate how long I rest, I inevitably come back to my writing with an incredible amount of new energy and excitement, which leads to me getting far more done than I would have if I’d forced myself to keep slogging through despite exhaustion.

Secondly, my mind sometimes presents me with writer’s block as a way to alert me to a problem with the writing itself. I’ve lost count of the number of times that I’m blithely working my way through a story and I suddenly lose momentum. I still have creative energy, I still want to write, but nothing I put on paper feels right, and eventually the words just grind to a stop. What’s happening here is that while my conscious attention is focused on the current chapter, some corner of my mind jumps ahead, considering future plot points and figuring out the repercussions of how I’m building a character arc — and sometimes I become subconsciously aware of a problem that I’m making worse with every sentence I write.

In this case, writer’s block is actually an extremely useful indicator that I need to take a step back, examine the big picture, and figure out where my writing has veered off course. Think of writer’s block like a headache: you can run through the gamut of tips and tricks and force yourself to keep moving forward, just like you can take some Ibuprofen and push through the rest of your day. But pain is the body’s way of communicating: maybe you have a headache because you’re sitting in a bad position and pulling something out of place in your back. And writer’s block is the subconscious mind’s way of communicating: maybe you can’t write because your plot beats aren’t arranged right and your character arc is going in the wrong direction.

So while there’s absolutely nothing wrong with trying quick tricks to break through a brief case of writer’s block, don’t be discouraged if it’s not that easy to get rid of. Remember that writer’s block isn’t necessarily a problem so much as it’s your mind trying to make you aware of a problem. Try reviewing your writing and looking for something that isn’t working as well as you thought it would. If revising your outline or your plan for the story doesn’t work, try giving yourself more of a break than the time it takes to walk the dog. And instead of focusing on getting rid of writer’s block, learn to translate writer’s block so you can get rid of the cause instead of just the symptom.

April 8, 2022

Sketching the Unseen

When worldbuilding for a fantasy or sci-fi story, one of the biggest dangers is getting caught up in the details, creating more and more minutiae about your world, and never getting to the actual writing of the story. Or, if you do manage to write, there’s a risk of trying to cram in as many worldbuilding details as possible and swamping the reader with fascinating but irrelevant information.

Many people advise that you avoid this problem by only worldbuilding the aspects of the world that are actually relevant to your plot. But this in turn can create the opposite problem: a narrow world, where the characters’ hometown or native land feels isolated, as if nothing else exists in the world around it. So how do you find the middle ground, where a world feels fully realized but not overly detailed?

This is a question I’ve been struggling with for years, but I think I’ve finally found the middle ground that works for me, along with a phrase to help describe my view on the matter: the best worldbuilding sketches the unseen.

There are two ideas in this phrase: first, the idea of worldbuilding as a form of sketching, as opposed to a complete and detailed image. Just like you wouldn’t want a portrait painting where the background is so detailed that it distracts from the subject’s face, you don’t want a story where the background information is so layered and complex that it distracts from the plot and characters. You should think about the whole world, not only the immediately relevant places, but most of the world should merely be sketched in, with just enough detail to reveal the general shape of things.

This will actually make your world seem more realistic rather than less, since this is how most people see the world around them. You meet a few rare people who might as well be Wikipedia with legs, but most people are intimately familiar with one area of life and only generally aware of places, peoples, and areas of study beyond their expertise. Thus, sketchy worldbuilding also becomes a form of character building. For example, if your character owns a tavern, she probably doesn’t know much about politics between nations, but she knows very well that imported wines are more expensive recently. From her point of view, the political situation is just some sort of complicated squabble happening far above her social tier and making her life harder — you can still give the reader a clear sense that there’s a bigger world with a complex political system and ongoing problems, but the scraps of information you reveal say as much about the character’s knowledge and values as about the world.

This leads to the second point, the idea of the unseen. One of the most powerful techniques of good writing is the ability to make the reader feel that they know or understand something without needing to spell it out. In the context of worldbuilding, this means giving the reader just enough information about the surrounding world that they feel aware of it even though they’ve never seen it. If your main character is never going to visit the far-off kingdom of Blob, the reader doesn’t need to know a ton of details about Blob’s political structure, education system, and unique flora. But drop an occasional comment about those crazy Blobians who think men are cool-headed enough to rule a country — oh, and did you hear the Blobian mage-colleges are competing to create an enchanted weed-killer to get rid of undead dandelions? — and the reader will feel like Blob is a real place somewhere beyond the border, never fully realized or clearly seen, but always there in the distance.

Different writing styles and different types of stories will require more or fewer background details, of course, but I think this idea of sketching the unseen is still valuable no matter what kind of story you’re telling. Lavish worldbuilding details have their place, but only in a context where the main character actually knows or cares a great deal about those details. Most of the time, sketchy glimpses of the world are more effective than piles of facts, both in terms of engaging the reader and developing the character and plot.

March 25, 2022

The Evolution of a Plantser

Over the years I’ve tried a number of different methods for planning and writing my books, but I always had trouble carrying through on my plans and actually finishing drafts. Finally, within the last couple years, I’ve managed to nail down the method that works best for me, which is a specific combination of discovery writing and outlining.

Usually, ideas come to me in the form of character moments or scenes with only a vague idea of a larger plot attached. For many years, I used to write the initial scene (rarely more than a page or two), then stop and spend a lot of time trying to nail down the plot and create an outline; I assumed this was the only correct way to approach a writing project thanks to years of listening to teachers tell me the importance — nay, absolute necessity! — of clear outlines. But by the time I finished high school, I’d come to the realization that I wrote far better essays and research papers if I didn’t outline first, and by extension I figured I should stop trying to outline stories as well.

For a while, I thought I’d figured it out: I was a discovery writer! No outlines for me! As soon as I started writing free-form, scenes flowed easily onto the page, thousands of words gushed forth — and then stopped. Story after story faltered and ground to a halt partway through. I figured I just needed a break; I set aside the incomplete drafts and started other projects — which also stopped flowing partway through. I tried going back to the incomplete stories, but I could never seem to regain momentum.

At last I recognized the pattern: every single one of these stories was between 20 and 25 thousand words long when the ideas stopped flowing. So I spent some time asking myself: why that length? What’s so important about the 20-thousand word mark?

The answer turned out to be fairly straightforward. The average novel is about 80 to 100 thousand words, which meant I was writing a quarter of each book before getting stumped. And what do you know, the first quarter of a book is usually setup, the section of the story that puts all the plot pieces into motion. That part of a story lends itself perfectly to discovery writing, because it’s all about throwing things at the characters, establishing questions that need to be answered or plot threads that need to be woven together.

But once I have a full novel’s worth of ideas, themes, and plot points established, I need to answer all the questions I’ve raised and solve all the problems I’ve created. And that’s where outlining comes into play. Once all the pieces of the story feel right, it’s time to take a more methodical approach to fit all those pieces together.

So at long last, I have my ideal writing process figured out! I get an idea and run with it, developing the characters as I go and introducing whatever themes or plot points feel right in the moment. Then, when I have enough pieces in play that I can’t keep track of them all by instinct, I take a step back, work out what I want to do with all the ideas I’ve introduced, and construct a satisfying ending from all the pieces. But my outlines are always plot-oriented, and I still discovery-write the character arcs as I go along, letting the characters do and say whatever feels right for them within the context of the plot I’m building.

So…that’s my current process. It’s clearly working, since I’ve completed and published two novels and two short stories in the past couple years! To any other writers who read this: if you haven’t nailed down the right process yet, don’t give up. It took me fifteen years to figure out how to finish a book, but I got there in the end, and sooner or later, you’ll find the perfect process for your stories, too.

March 11, 2022

Oops, Another Short Story (or Three)

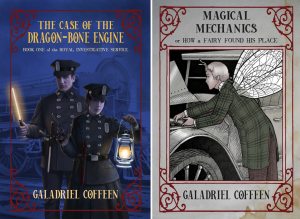

I never planned to write any short stories. But when I was preparing to self-publish my first novel, a lot of people advised me to start by releasing a free story to help market the novel and to give people a taste of my writing before they committed to buying a full-length book. So I picked my favorite side character from the novel, Pretty Pinchworth, and wrote a short story about her learning to drive. (Which you can find here for free if you haven’t read it yet.)

But then Pretty wouldn’t go away. She informed me she had a story arc that needed telling; true to her stubborn character, she wouldn’t leave me alone until I planned two more short stories to take place in the gaps between the Royal Invstigative Service novels. Well, I told myself, that was just fine. It would be nice to have something short to publish between novels to help keep my audience engaged and eager for the next book.

So I started working on Pretty’s second short story, but much to my surprise, Pretty’s determination to gain the spotlight had rubbed off on her boyfriend Denny, who insisted that this second story was actually supposed to be written from his perspective. He was right, but that threw a wrench in my plans. Focusing on Denny meant I wasn’t able to advance Pretty’s arc in this story the way I’d originally intended.

Obviously that meant I’d need to add another story. That’s where I am in the process now: drafting the third story about Pretty and Denny. Like the second story, this one will take place between books one and two of the Royal Investigative Service; but this time, I’m writing from Pretty’s point of view again, taking her another step closer to freedom and equality for herself, her family, and all fairies.

All well and good, but I’d barely started writing when Denny came knocking on the inside of my head again. He wasn’t satisfied with just one story. Now that I’ve introduced his point of view, clearly I’m going to start alternating stories told from his perspective and Pretty’s perspective, right? Which means the story set between books two and three of the Royal Investigative Service has to be about him, right?

Well, yes, as it turns out, that story would work better from Denny’s perspective. But now I face the same problem I encountered with the second story: switching to Denny’s point of view means de-emphasizing the character arc I already planned for Pretty. Which means adding yet another story to continue the initial plan. So the events that would have been story three now become stories four and five.

As I considered this new plan, both Pretty and Denny (by now quite accustomed to demanding more from me) showed up to insist that in fact there should be just one more story. And not a short story this time, no. Since I was already writing this much about them, why not finish off their arc with a novella? A novella would do nicely, thank you.

There was really no point in arguing. Once the idea entered my head, I knew it wouldn’t go away. And come to think of it, there was an important piece of worldbuilding that I wanted to introduce, but I hadn’t yet decided how to tell that story — and what do you know, that story would be a brilliant way to end Pretty and Denny’s arc.

So what was originally intended to be a single introductory short story has turned into a much larger arc for two delightful characters as well as a vehicle for some very important worldbuilding. It came a bit out of nowhere, but I’m very pleased with the new plan. And in case you didn’t quite follow the convolutions of this tale, here’s a nice orderly list of all the stories I’ll end up with:

“Magic and Motor-Cars, or How a Fairy Moved Up in the World”The Case of the Dragon-Bone Engine (Royal Investigative Service 1)“Magical Mechanics, or How a Fairy Found his Place”“Magical Moonlighting, or ______” (subtitle not yet determined, Pretty’s POV, coming August 2022)The Case of the Golden Vigilante (Royal Investigative Service 2) coming February 2023“Magical Methodology” (very uncertain working title, Denny’s POV)“Untitled Short Story” (Pretty’s POV)The Case of the Fairy Experiment (Royal Investigative Service 3)Magic and ____, or How to Fly without Wings (novella, has sections from both Pretty’s and Denny’s POVs)Pretty and Denny’s first five stories will initially be available only as ebooks, since they’re too short to be worth printing individually. However, when I get to their final story, I plan to publish that as part of an anthology, including the five short stories as well as the novella. This means that ultimately, there will be four volumes in this series: the three RIS books, plus the compilation of Pretty and Denny’s six stories. The complete series is a long way off, but I’m already imagining the four books lined up on a bookshelf with matching covers, and I’m really excited to reach that point someday.

February 25, 2022

Books on My Reading List

I rarely select books to read in advance; I’m an inveterate browser of library shelves and used bookstores, selecting books based solely on what catches my eye in the moment. But I’ve decided to try planning my reading a bit this year, and I’ve started by selecting four books to add to my official reading list. No doubt I’ll read a great many more books than that, but I’m committing to reading and reviewing these particular novels. I’ve already read the sample sections on Amazon, enough to pique my interest, and I’m looking forward to all of these!

![A Face Like Glass by [Frances Hardinge]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1645831863i/32618723.jpg)

A Face Like Glass, by Frances Hardinge

Frances Hardinge’s Website

Follow on Twitter

In the underground city of Caverna, the world’s most skilled craftspeople toil in the darkness to create delicacies beyond compare—wines that remove memories, cheeses that make you hallucinate, and perfumes that convince you to trust the wearer, even as he slits your throat. On the surface, the people of Caverna seem ordinary, except for one thing: their faces are as blank as untouched snow. Expressions must be learned, and only the famous Facesmiths can teach a person to express (or fake) joy, despair, or fear—at a steep price.

Into this dark and distrustful world comes Neverfell, a girl with no memory of her past and a face so terrifying to those around her that she must wear a mask at all times. Neverfell’s expressions are as varied and dynamic as those of the most skilled Facesmiths, except hers

are entirely genuine. And that makes her very dangerous indeed.

Last of the Memory Keepers, by Azelyn Klein

Azelyn Klein’s Website

Follow on Twitter

I had the pleasure of meeting Azelyn Klein at an author reading event last year, where I heard her read aloud a very enjoyable section from Last of the Memory Keepers. We exchanged books; I brought home a copy of Memory Keepers while she took a copy of The Case of the Dragon-Bone Engine. I’ve been meaning to read her book for some time but haven’t gotten around to it yet, so I’m particularly looking forward to this one!

“Just because something’s forgotten doesn’t mean it never existed. History may forget our names, but that doesn’t mean we never lived.” Rhona Farlane is among the top three apprentice Memory Keepers and an advocate for the unification of the remaining three races. But some days, she feels like she’s the only one willing to put in enough effort. Her closest friends, Finley and Ellard, are either too reckless or too reserved to make a positive impact on the world, and her uncle doesn’t even believe she deserves her apprenticeship. Determined to make a difference anyway, she joins her father on her first diplomatic mission in the Southern Rim where negotiations are going smoothly. Perhaps too smoothly. Then a tragedy threatens to cease all negotiations within her lifetime and even start a war. Will Rhona ever be able to achieve unity when everything she believes about her world is shattered?

![Secrets in the Mist (Skyworld Book 1) by [Morgan L. Busse]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1645831863i/32618725.jpg)

Secrets in the Mist, by Morgan L. Busse

Morgan L. Busse’s Website

Follow on Twitter

What’s lurking in the Mist is the least of their worries…

In a world where humanity lives in the sky to escape a deadly mist below, Cass’s only goal is survival. That is, until she finds a job on the airship Daedalus as a diver. Now she explores ruined cities, looking for treasure and people’s lost heirlooms until a young man hires her to find the impossible: a way to eradicate the Mist.

Theodore Winchester is a member of one of the Five Families that rule the skies. Following in his father’s footsteps, he searches for the source of the Mist and hopes to stop the purges used to control overpopulation. But what he finds are horrifying secrets and lethal ambition. If he continues his quest, it could mean his own death.

The Mist is rising and soon the world will be enveloped in its deadly embrace, turning what’s left of humanity into the undead.

A Drowned Kingdom, by P. L. Stuart

P. L. Stuart’s Website

Follow on Twitter

Once Second Prince of the mightiest kingdom in the known world, Othrun now leads the last survivors of his exiled people into an uncertain future far across the Shimmering Sea from their ancestral home, now lost beneath the waves. With his Single God binding his knights to chivalric oaths, intent on wiping out idolatry and pagan worship, they will have to carve out a new kingdom on this mysterious continent―a continent that has for centuries been ravaged by warlords competing for supremacy and mages channeling the mystic powers of the elements―and unite the continent under godly rule.

With a troubled past, a cursed sword, and a mysterious spirit guiding him, Othrun means to be that ruler, and conquer all. But with kingdoms fated on the edge of spears, alliances and pagan magic, betrayal, doubt, and dangers await him at every turn. Othrun will be forced to confront the truths of all he believes in on his journey to become a king, and a legend.

When one kingdom drowns, a new one must rise in its place. So begins the saga of that kingdom, and the man who would rule it all.

February 11, 2022

Names in the Shallic Sea

When Anneliese and I first named Wren and Kelta, we hadn’t done any worldbuilding or established any rules for the languages of the Shallic Sea. This means that the main characters’ names were the first examples we had of words from their languages. Ellondese and Taxian were born from those words: “Wren Elspur” and “Kelta.”

From the beginning, Ellond was a pretty blatant ripoff of Napoleonic-era England, so it was easy enough to develop naming conventions for Ellondese characters: if it sounded British, it would probably work. However, I didn’t want to use too many real-world names, so I was careful, especially with surnames, to pick constructed or uncommon options. We ended up with a few real last names, like Strathmore and Whitney, but most of the names were English-style constructions, such as Elspur, Wellerdon, Lawbright, and Cavender. Those family names could exist in English, but I’ve never encountered them.

When it came to first names, Wren set an obvious precendent for bird names, giving rise to characters such as Nightingale and Starling. Later, we determined that this is a recent naming trend: the crown prince of Ellond, age 25 at the time of the first book, bears the grand and magnificent name Canary. As soon as his name was announced, other nobles in the court began naming their children after birds as well, and within a couple years, the fashion spread throughout the nation. Canary was rarely used as a first name, to avoid imitating the prince too closely, but a large number of boys, including Wren’s elder brother, were saddled with the middle name Canary. However, by the time of Jubilant’s events, this naming trend has mostly passed, and it’s rare to find anyone younger than ten or twelve with a bird name.

During the writing process, we also thought it would be funny to stick Wren with the name Gentle, and this in turn set the precendent for virtue names. This gave us characters such as Gallant, Justice, and Considerate. As we filled in more first names, we continued the practice of using a few real English (and French) names along with potentially-English-sounding names. Thus we ended up with Gavin, Geraldine, and Clarabelle on the one hand; and Devald, Treman, and Pallin on the other hand. Hopefully the end result is a set of names that sounds familiar and comfortable to English speakers but doesn’t quite line up with real-world naming conventions.

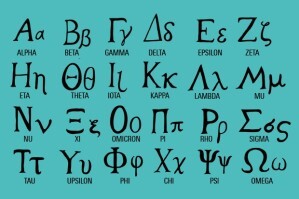

Taxian names actually developed more simply: although Taxia was never an analogue to a real-world nation like Ellond was, their language is heavily inspired by an existing language, namely Greek. Kelta’s name and the name of the country, Taxia, both hinted at a Greek sound, so we took that hint and ran with it. Some of the Taxian words that appear in Jubilant are literally just Greek with a few letters changed: for example, “dikaiat” (justice) comes directly from the Greek “dikaiosune” (justice). We’ve also used some preexisting Greek names, such as Kastor and Kalon. However, for the most part, especially when naming characters, we’ve created words from scratch using the established sounds. Names like Ganat, Keltorax, and Ragam use letters and common letter combinations from Greek, but don’t follow any of the actual Greek rules for names. Most notably, Greek names almost exclusively end in A, E, OS, or ON; we’ve expanded to end names with a variety of other letters, which hopefully gives Taxian names a unique sound despite the fact that we’ve lifted the phonemes straight from Greek.

We also decided early on that the Taxians don’t have surnames, instead identifying themselves by their clans and their relationship to notable teachers or leaders. This opened the door for a whole new naming convention, where Taxian “surnames” are essentially complex ideograms with no verbal component. They use these family patterns in place of traditional last names, wearing them prominently on their clothing and jewelry. Thus, the image to the left is essentially Kelta’s “last name,” though put into words, it would be more like a resume: member of Darias Clan, related to Haias Ganat, a warrior by trade, trained in the Snake School, taught by Grand Haias Kastor, owner of a drachon trophy. The Taxians don’t exactly think of family patterns as names, but they consider their patterns a core part of their identities and use them for identification in much the same way that we use surnames.

As for the other nations of the Shallic Sea, they have their own naming conventions as well, but we’ll save those for another time.

January 28, 2022

Self-Publishing an Audiobook

This month, I’m spending a lot of time recording an audio version of The Case of the Dragon-Bone Engine, so I thought I’d give you a quick walkthrough of the process. This is only the third audiobook I’ve ever recorded, and I barely comprehend the basics of audio editing, so this is far from expert advice! Still, I’ve learned a lot along the way and I’m excited to give you a quick glimpse into this month’s project.

Most posts I’ve found on the topic of home audio recording jump straight into the technical details, often leaving out the big prerequisite, which is reading practice. You can record in the world’s best sound studio and still end up with a poor quality audiobook if you don’t practice reading first. Thankfully, I’ve had a great deal of training in public speaking, acting, and reading aloud to an audience, which is immensely helpful in preparing for audiobook recording, but I still make sure to practice before recording.

If you listen to audiobooks at all, you’ve probably encountered some impressive actors who can produce hundreds of different voices and accents for the characters. I’m nowhere near that level (though I feel like my skills improve every time I listen to legends like Michael Kramer and Kate Reading), and you certainly don’t have to be on that level to produce a good audiobook either, but it is very important to practice your vocal skills. Practically every source I’ve found differs on the most important ways to practice for an audiobook, so I’ll just boil down the gist of what I’ve found both through research and my own practice:

The most important thing is confidence. You have to be familiar enough with the text to sound as if you’re simply talking, not reading. If you aren’t comfortable with the words coming out of your mouth, you’re more likely to stumble over words, and even if you don’t make mistakes, your uncertainty will be audible in the final recording. At the same time, don’t get flustered or worried if you do make mistakes. You can always do another take and edit out the errors. Also, it’s ok if you can’t do twenty accents or pitch your voice super low and super high: what’s more important is to alter your cadence, speed, enunciation, and general vocal quality to convey emotion and character. Does this character speak slowly and deliberately, or quickly and nervously? Does he put a lot of force and emphasis into his words? Does she talk down to everyone she meets? Do they always sound sardonically amused with life?

Now for the technical stuff. Experienced podcasters or youtube creators can give much better recommendations on recording equipment than I can, but the long and short of it is this: microphone technology has advanced far enough that you don’t need super expensive recording equipment to get good results. I’m using a Blue Yeti microphone, which costs a little over a hundred dollars and produces very nice sound quality despite the fact that I’m recording in my home office, which has no soundproofing or acoustic improvements. When I recorded “Magic & Motor-Cars” last year, I built a PVC pipe frame around my desk and hung pieces of old carpet from the frame to create a DIY sound booth. However, there was no discernable difference in audio quality with or without that precaution, so this time around, I’m not bothering. It seems that the quality of the microphone is more important than the acoustics, so long as you’re not in a particularly noisy or echoey space. I do pick up the occasional louder noise from the road outside, but it’s easy to filter out in editing.

On that topic, I record and edit in Audacity, which is one of the most highly recommended open-source audio programs. It doesn’t have the most user-friendly layout I’ve ever seen, and it took me a little while and a lot of tutorials to figure out how to use it, but it does what I need it to do with a minimum of fuss and bother. To start with, I streamline my process by doing a lot of editing while I record. This is a huge advantage to sitting in front of my computer as I record instead of being in a separate sound booth. If I mispronounce something, skip a word, or don’t like the intonation I put into a sentence, I just pause the recording, delete the sentence I messed up, click record again, and start fresh from the beginning of the sentence. This means that when I finish reading the chapter, the resulting audio file is already free from mistakes and unsatisfying takes. Then I run a few filters to reduce background noise, delete any clicking or hissing noises, and adjust the audio levels to match Audible’s requirements, and that’s it.

Once I’m happy with my recordings, I publish my audiobooks using ACX, which is Audible’s self-publishing service; essentially, it’s the audio version of Kindle Direct Publishing. If you create an author account on ACX, you can either hire a freelance voice actor to record your book for you, or upload your own recordings directly. Unlike when you publish a Kindle book, you don’t select the price for your audiobook: Audible calculates the price for you based on the length of the recording. Personally, I find this a bit of a relief, since I hate trying to figure out reasonable prices for things. When I uploaded “Magic & Motor-Cars” to Audible, I also discovered that ACX didn’t do a very good job of predicting how long it would take for them to review my audiobook and approve it for sale. That was a bit annoying, since it meant I couldn’t set a release date for the audiobook, but it was 2020, so hopefully they were just short-staffed and they’ll be able to approve my future books more quickly.

In any case, ACX has some fairly clear guidelines for uploads, as well as some tutorials that helped me figure out some of the basics of audio editing. Between that, the fairly impressive tools build into Audacity, and the good-quality microphone, I’m able to produce good quality audiobooks at home. I still feel a bit lost at sea when it comes to the more technical aspects of audio production and editing, but I’m learning more with every recording session, and hopefully The Case of the Dragon-Bone Engine will be available from Audible soon!

January 14, 2022

Projects for the New Year

Happy new year, humans! I’m gearing up for a year crammed full of writing projects, and I’m excited to give you all a peek at what I’ll be working on.

To start with, I’ll be spending January catching up on audio recordings that I didn’t have time to complete last year. Most importantly, I’m recording the Audible version of The Case of the Dragon-Bone Engine, which has now been out for over a year with no audio version available. I should also have time to record the audio version of “Magical Mechanics,” the second short story in this series. I don’t know how long those two projects will take, but if I have time left over before the end of the month, I’m hoping to start recording at least the first few chapters of Jubilant as well. I’ll then continue chipping away at that audiobook over the following months; starting with Jubilant, I’m hoping always to release audiobooks within six months of publishing the text versions.

Anneliese and I are also jumping straight into the second Shallic Sea novel, Keltorax. Technically we already have a complete draft, but things have changed enough during the process of writing the first book that we’re pretty much scrapping the current manuscript and starting over. The outline hasn’t changed significantly, but the characters have developed a great deal. We’ll work on our new rough draft in bits and pieces, whenever we have a bit of spare time to write, and hopefully we’ll have a complete manuscript before the end of the year, leaving us all of next year to edit before the February 2024 publication date.

However, my big project for this year will be the second Royal Investigative Service novel, The Case of the Golden Vigilante. I have a rough outline, but I need to do a lot of polishing and rethinking before I can even start drafting. My goal is to finish the outline by the end of February and the first draft by the end of April. That should leave me plenty of time to edit throughout the rest of the year, work on the illustrations and cover art during the winter, and have the book ready for publication in February 2023. I’m also planning a (somewhat unexpected) third short story about Pretty and Denny which I’m hoping to publish this summer, filling in a little more of what the fairy kids are doing between books 1 and 2 of the main series. I don’t have a subtitle for this story yet, but the first part of the title will be “Magical Moonlighting.”

All in all, it’s going to be a rather busy year in terms of writing, but this sort of schedule is going to be the “new normal” as I move forward, since I’m eventually hoping to start publishing two books per year. We’ll see how that goes in the long term, but for now, I’ve had a good break over the past month and I’m eager to jump into the new year’s writing projects!

December 29, 2021

A Brief History of the Shallic Nations

An excerpt from The Origin and Subsequent Development of the Civilized Nations of the World, by Professor Diligent Whiting of Accord University in Fossen

As you no doubt have heard, two great empires once dominated the Shallic Sea: Alok to the north and Nebor to the south. The eastern lands were mostly uninhabited at the time, though a collection of small tribes lived along the border of the Neborite Empire, largely ignored by their more powerful neighbor.

History has forgotten what first set the Alokites and Neborites in conflict against each other. Some say they fought over powerful magical artifacts, since both empires were led by mages. Others say that Nebor attacked to free the thousands of slaves upon whose backs Alok built its empire. However, most scholars who posit this theory are committed to the modern efforts to abolish the slave trade and are, perhaps, reading their own prejudices against Alok into their view of history.

Whatever the reasons, war raged between Alok and Nebor for years, perhaps decades, and soon took on the characteristics of a religious crusade, in which each empire considered itself bound by holy duty to end the atrocities of the other. It was this chaotic time that gave rise to the Sakussar Alok sect, those zealots who dedicated their lives to ridding Alok of all foreign influences and modern advancements that might alter their sacred traditions, and who still revive their efforts from time to time today.

Perhaps five years before the Destruction, the prominence of the Sakussar Alok movement prompted an Alokite warlord by the name of Badra Pora to turn against his tal-badra and desert from the Alokite war effort, taking with him approximately five thousand soldiers and at least three times that number of craftsmen, farmers, and their families from his principality. By various means, they acquired the “hundred ships” of legend — though in truth, given the size of ships at the time, they likely collected well over a hundred vessels into their fleet — and set sail into the unclaimed east in hopes of escaping from the war and establishing a new land of peace.

In time, they landed at the mouth of a broad river and established a city which they named Sorba, an ancient Alokite word meaning “new home,” which they later altered to Soruva as the colonists’ dialect shifted. They quickly expanded upriver and began constructing the great city of Porasis, where Pora built his palace; this, of course, was the origin of Poravia, named for its vaunted founder.

But as the self-styled King Pora began laying the foundation for his new nation, the war between Alok and Nebor raged on more fiercely than ever. Finally, Nebor’s starwatchers, magicians who were said to have prophetic abilities, proposed a plan to break Alok’s power once and for all. A great fleet sailed north, every bit as vast as Pora’s hundred ships, and landed on the eastern border of Alokite territory in preparation to march on the Alokite capital of Gath. While this army mustered in the wilderness, the Neborite mages prepared a spell such as the world had never seen before and, gods grant, will never see again: they called down fire from heaven, a rain of meteors to obliterate their enemies.

However, the Alokite mages were every bit as powerful as their Neborite counterparts, and as soon as they saw the spell of destruction taking shape in the south, they began weaving their own counterspells. Their reaction came late: before they could stop the Neborites, the city of Gath was destroyed, leaving only the broken ruins that still stand on their hilltop eighty miles east of the modern city of Alrose. But the mages managed to save their other great cities, deflecting the rain of fire away from Alok and turning the destruction back on its casters. The ancient Neborite city of Makpashir was burned to cinders, and the Great Circle Temple where Nebor held its deepest secrets of magic was shattered to pieces.

Despite this vast scale of destruction, most of the meteors the Neborites called down never struck either empire: instead they were pushed eastward by the clash between the mages, flung away into the ocean where, so the mages supposed, they would do no damage. However, one of the strikes fell at the eastern edge of Alok, where the Neborite army was gathered. The rain of fire and the resulting tidal waves destroyed their vessels and forced their army inland. Trapped in unfamiliar country with no shipwrights to rebuild their fleet, they had no choice but to begin building houses instead. They welcomed a number of Alokite refugees fleeing from the destruction of Gath, in particular a large delegation of women seeking relief from their harsh treatment as slave-wives. These women willingly married the more egalitarian Neborites and helped them to establish a prosperous settlement which eventually took the name Ellond.

Some years later, once the Ellondese had established themselves and begun relearning the art of ship-building, they sent an expedition south in hopes of returning to Nebor for aid. Halfway there, the travellers were astonished to find a large archipelago of islands that none of them had ever heard of. They quickly determined that the islands were newly formed by volcanic activity, and they concluded that the meteors that rained down in the ocean split open the earth beneath the water and birthed the chain of islands. One ship remained behind to explore the rich, fertile new land and to report back to Ellond, while the other ships of the expedition continued south toward Nebor.

As the Ellondese discovered, Nebor was still in chaos, its greatest cities destroyed and its forests overrun with strange new monsters born from the vast outpouring of magic during the Destruction; they had no ability to aid their lost army. On the contrary, hundreds of Neborite citizens took the chance to flee their ruined country: as soon as they heard the Ellondese expedition’s report about the island chain, they sailed north to claim new land and new lives for themselves. Many of the Ellondese chose to move there as well, since the islands were much warmer and more fertile than Ellond, and in time they named the archipelago Fossen and established their own traditions and language, separate from both Ellond and Nebor.

As decades and centuries passed, each nation naturally took on its own character and established its own rich history; indeed, the eastern nations became so independant that to this day, they often deny their Alokite or Neborite origins. The only nation which remained largely untouched by the Destruction and its aftermath was Taxia, which in all honesty was no nation at all, since each of its tribes remained autonomous and nomadic. While the rest of the Shallic Sea developed new technologies and treaties, Taxia remained solitary and inward-focused, so absorbed by its own affairs that until this very year, their culture and values remained almost entirely unknown to the other nations of the Shallic Sea.

But let more august historians reason out the isolated development of Taxia; for now, let it suffice that they changed very little over the years, while other nations rose and fell around them. One may write a hundred treatises on the history of each nation, but at its heart, the development of the Shallic Sea rests on one cataclysmic event: without the horror of the Destruction, the nations as we know them today would surely not exist.