Ron Base's Blog

September 5, 2025

HOPE, HEARTBREAK AND MAGIC: A BOOK-PUBLISHING TALE

If on the rare occasion anyone cares enough to ask, of all the novels I have written, I always answer that Magic Man is my favorite, the love of my ill-starred literary life.

As soon as I say this I am usually rewarded with a blank stare and a nervous half-smile. Magic Man?

The fight to get Magic Man published is a saga of hope and heartbreak. The hope is you have written a great novel, an international bestseller that will place you firmly on the literary map. The heartbreak is the realization you haven’t.

Here is the story: A mysterious young man named Brae Orrack arrives in Venice, California, in 1928. He claims to be a magic man who can turn stones into bees and is under a curse: he will die unless he finds true love. Brae, in need of money, becomes the chauffeur and bodyguard for a young actor named Gary Cooper. He enters the glamorous and chaotic world of early Hollywood, where he encounters real-life figures like Clara Bow and George Raft, and gets involved with gangsters and bootleggers.

An adventure novel, a fantasy, and a love story that I began writing while living in Los Angeles. Over the four years I worked on the book, it underwent many incarnations and a lot of frustration. What kept me going was the joy not only of taking the story to places I never would have imagined but also in doing the period research at the Library of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and in the archives of the Los Angeles Times newspaper.

I finally finished a version of the book after my wife Kathy and I moved to Montreal. Trepidatiously, I turned it over to my longtime agents, Francis Hanna and her husband Bill. They moved heaven and earth attempting to sell it in Canada and the U.S. To their everlasting credit, they never gave up. Bill pulled off some real life magic when he finally sold Magic Man to St. Martin’s Press in New York. A moment of euphoria was followed by the usual intrusion of stomach-churning reality.

The advance St. Martin’s Press offered was a pittance and, although I didn’t realize it at the time, signalled then and there they weren’t going to put much effort into marketing the book. The editor, Pete Wolverton—I was one of two hundred and fifty books Pitbull Pete, as one author nicknamed him, would be handling that year—liked the book but hated the ending. Months of rewrites ensued. The ending changed. The book only got better. Pitbull Pete was eventually, well, at least satisfied. Then silence to the point where I was certain they weren’t going to publish the book. Pitbull Pete was reassuring—it would be published.

Three years after the manuscript landed on Pete Wolverton’s desk, and seven years after I started to write it, Magic Man was finally a reality. Very quietly. I was told a publicist would get in touch. No publicist ever did.

The day of its publication, I happened to be in Chicago. I dropped into a big downtown bookstore. They were sure they had a copy in stock. A…copy? They tried their best, they searched high and low over the immense store, but they couldn’t find the book. They were sure they had it. Somewhere. Many apologies. A year or so later, I finally came across a single copy in Toronto’s The World’s Biggest Bookstore. It was the only time I ever saw the book in an actual bookstore. Every time I think about this, I still scratch my head. Why did St. Martin’s Press even bother?

The reviews were mixed. The book trade bible, Kirkus Reviews, gave it a starred review: “Beautiful women and gangsters, movie stars and dictators all rub shoulders in this delicious tongue-in-cheek debut set in 1920s Hollywood…. Base works his own magic as he crisply choreographs the entrances and exits of his large cast. There will be thrills aplenty before we are done, and disillusionment, but never defeat for the resilient Brae. A page-turner, spiffy and irresistible.”

In Canada, the Edmonton Journal liked it: “It takes off with relentless speed, refusing to permit us to catch our breath. Never boring, Magic Man makes for an entertaining and engrossing tale…”

But other reviews were less enthusiastic. The Globe and Mail thought the period detail was okay but otherwise… Entertainment Weekly, which could have made a difference with booksellers, gave it a no-sale B minus. In my dreams that B minus still comes back to haunt me.

Not that any of it made much difference when all was said and quickly done. No matter what happened to it—and nothing much did—I loved Magic Man then and I love it still. For me it said all the things I had always wanted to say about love and movies, the two things I could never have gotten this far in life without.

On Sunday I will be at the Eden Mills Writers Festival in the Ontario town of Eden Mills, courtesy of my good friend Stephen Froom. I will have copies of Magic Man with me. Like Brae Orrack, the hero of the book, I refuse to give up. Hope and heartbreak—the essence of life and book publishing.

If you are in Eden Mills this weekend, please drop by. I’m the guy with the big smile, holding a book, hoping…

August 31, 2025

Wallflower at the Orgy

The Toronto International Film Festival as it is now known, celebrates its 50th anniversary this week. From someone who, to paraphrase Nora Ephron, was a mere wallflower at the orgy—er—festival during those early years, a few memories…

The Corner Table: Bill Marshall pretty much owned the corner table at Club Twenty-Two (nick-named the two-two) Toronto’s most fashionable and celebrity friendly watering hole located inside the Windsor Arms Hotel. Watching from afar before I knew him, I was somewhat in awe. Bill spoke in a low, gruff growl so that you had to pay attention and he did not suffer fools gladly—as I found out on occasion. Meeting him, it wasn’t hard to believe he was the smartest guy in the room. He held court at the 2-2 most nights, often joined by his partner in crime, Henk Van der Kolk, a cowboy hat-wearing lawyer named Dusty Cohl, and the writer Tom Hedley who would go on to originate the screenplay for the hit Flashdance. Bill and Henk were movie producers at a time when Hollywood North was flourishing. They would have their biggest success with Outrageous in 1977. What you could not have imagined was anyone at that corner table coming up with the notion for a movie festival. What the hell was that all about? I wondered when I first heard the idea being floated.

From the (Carlton) Terrace: Back in the days when I was kicking around the Cannes Film Festival, everyone came to the terrace of the Carlton Hotel, and at one point or another, everyone seemed to find their way to Dusty Cohl’s table. Surrounded by an everchanging cast of characters, wearing his trademark black cowboy hat, he was hard to miss. It helped that Dusty was buying the drinks and remained something of a mystery in a place where everyone else was only too eager to let you know who they were. Invariably, as soon as Dusty got up to leave, someone would lean over and whisper to me: Exactly who is Dusty? I always replied, “Your guess is as good as mine.”

Affectionately, Henky-Panky: Henk Van der Kolk, christened “Henky-Panky” one evening at the Twenty-Two, avuncular and courtly, the gentlest and least flamboyant of the three founders. That constant twinkle in his eye was a reminder he wouldn’t be taking festivals or life too seriously. My first wife, Lynda, and I became good friends with Henk and his wife, Yanka, a popular Toronto model and one of the city’s great beauties. They were among the guests at our wedding. Yanka dazzled as always. If you saw the wedding photos you would have thought Yanka married Lynda.

The Miracle Workers: Bill, Dusty, and Henk may have founded the festival, but it was the combination of Wayne Clarkson and Helga Stephenson who provided the organizational gravitas and created the required daily miracles. Watching them in action was an object lesson in retaining one’s cool while overcoming the challenges and near catastrophes that always seemed to be flaring up. Everyone almost immediately fell in love with Helga. Two minutes after you met Wayne, he made you believe you were his best friend in the world. I could never resist either of them.

The Secret Weapon: The Paris-based American critic (and occasional actor), David Overbey, was, I would argue, as responsible as anyone for the early success of the festival. David introduced Asian cinema to North America, the films of the German director Reiner Werner Fassbinder as well as the Hong Kong action director John Woo. He was invaluable in helping to establish Toronto at the Cannes Film Festival. An extraordinary character, David was a combination of acerbic wit, sharp intelligence, and unflappable arrogance. Early one morning in Cannes, Steven Spielberg screened for the press his latest film. No one knew a thing about it except the title, E.T. When it ended, there was a moment of complete silence in the theatre as everyone took in the magic of what they had just experienced. Everyone except David. As the lights went up, he sprang to his feet and announced: “Well! What a piece of shit that was!” Pure David.

The (Sort Of) Big Festival Story Everyone Missed: As Helga Stephenson and I were leaving the Park Plaza Hotel with Lee Majors one year, we encountered Ryan O’Neal of Love Story fame. Lee was the star of the hit TV series Six Million Dollar Man and the husband of actress Farrah Fawcett-Majors, at the time, thanks to her bestselling poster, America’s pinup icon. Lee and Ryan exchanged greetings. Ryan mentioned that he was leaving Toronto the next day. Lee said he was staying on to shoot a movie. We all got on the elevator together. As it started down, Lee turned to Ryan. “Listen,” he said, “when you get back to L.A. will you do me a favor and stop in and see Farrah, make sure she’s all right?” Ryan quickly agreed. In fact, Ryan did as he promised. The rest was a whole lot of tabloid history.

The Magnificent Six: Bill and Dusty and David are gone now but Henk, Wayne and Helga carry on. Fifty years later it is impossible to imagine a film festival in Toronto without those six. They were the perfect combination of the talent, hutzpah and audacity needed back then. In different ways I adored them all. This week I’ll be lifting a kir royale in celebration of what they achieved.

A kir royale? It’s all right. They will know what I mean.

August 4, 2025

My Dinner with Hilary and Galen: Best Friends Forever!

The news of the death of former Lieutenant Governor and philanthropist Hilary Weston sent my mind spinning back to the night Hilary and her husband Galen Weston dined with me and my wife, Kathy. The night the four of us became best friends forever.

By happenstance, I found myself seated next to Galen Weston at what turned out to be the last lunch hosted by the Hollywood columnist George Christy as part of the Toronto Film Festival.

The two of us were seated with Lynne St. David, an old friend of mine and the wife of the great filmmaker Norman Jewison.

At the time, Galen maintained a controlling interest in Loblaws Companies and was the second (or third?) richest man in Canada.

When I mentioned to him that my wife was a vice-president at Loblaws, he immediately perked up. For the next three hours as the luncheon droned on, Lynne and Galen and I ignored everyone else, laughing and chatting away, having a whale of a time. Galen turned out to be a delightfully genial luncheon companion.

When lunch was over, Galen took me aside and said, This has been so much fun. Why don’t you and your wife have dinner with Hilary and me?

When I told Kathy I had lunched with Galen Weston and he wanted to get together for dinner, she didn’t quite turn white, but it was close. She looked at me in disbelief and said, “What?”

We both consoled ourselves that, yes, lunch was a lot of fun, but there was no way we would be getting together any time soon with the Westons.

Two weeks later, the phone rang. It was Galen Weston. Let’s figure out a date for when we can get together for that dinner we talked about, he said.

When Kathy arrived home that evening, I told her about the phone call. We were having dinner with the Westons. She said, “What?”

As the date approached, I was sure Galen would cancel. He didn’t. Instead, he called Kathy at Loblaws’ Mississauga, Ontario headquarters and invited her to his office.

They chatted for a time and then Galen announced he wanted to see where Kathy worked. Together, they went down to her desk. Everyone she worked with was agog—the owner of the company hanging around with Kathy.

On a stormy, blustery November night, we met the Westons at what they said was their favorite downtown Toronto restaurant. They were already seated when we arrived, both sipping on cosmopolitan cocktails. They greeted us like long lost friends. Whatever else they were good at, they were superb at putting their guests at ease.

In the subdued warmth of the restaurant, while a storm howled outside, there was endless conversation punctuated with lots of laughter. An onlooker might well have mistaken us for four friends who had known each other forever.

Eventually, Galen took control of Kathy for a tête à tête about her views on Loblaws. I was seconded to Hilary. Now I have to say that my memory of her is of a slightly batty but charming conversationalist.

While Kathy and Galen talked serious supermarket business, Hilary and I furiously dropped names. For example, when I let it out that I had recently worked on a script in Rome with director John Boorman, she countered excitedly that the Boormans were neighbors and close friends in Ireland!

As the evening drew to a close, Galen was inviting us to Windsor. Dummy that I was, I initially thought he was talking about Windsor, Ontario. On the verge of announcing that I had once worked in Windsor, in the nick of time it became apparent they were referring to the very high-end village they had created north of Palm Beach, named, not after the Ontario City, but their place in Windsor Great Park outside London.

By the time we hugged and said our goodbyes, Hilary and Galen were our new best friends forever. Why, I wouldn’t have been surprised if they arranged to have us move in with them.

Still laughing away and promising to keep in touch, they disappeared through the snow and into their chauffeured limo waiting outside the restaurant.

We never heard from them again.

But for a few hours on that snowy night, they were our very best friends in the whole world.

July 10, 2025

The Anne Frank Attraction

I

It is not easy to get into the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam.

Tickets are limited. A new batch becomes available every few weeks at 10 a.m., Amsterdam time. We got up at six a.m. to secure ours. They were gone in two hours.

The musings and recollections of a teenaged girl about life in the place where she and her parents hid from the Nazis during the worst days of the Holocaust, has continued to attract and fascinate the world for more than eighty years. The Diary of a Young Girl has been published in seventy-five languages and sold over thirty million copies since its publication in 1949.

The space that Anne referred to as the secret annex, was located in the back of a storage warehouse operated by Otto Frank, Anne’s German-born Jewish father. It has been transformed into a museum built around the original two floors where eight people were crammed together: Otto and his wife, Anne and her older sister, Margot. They were joined by the van Pels and their son, Peter. The eighth occupant was a dentist named Fritz Pfeffer, a curious addition since the others hardly knew him.

With help from friends and Otto’s employees, the group hid together for two years from 1942, when the Nazis started rounding up Jews, to 1944 when the family was discovered and sent off to Auschwitz.

During that time, Anne, who had a burning desire to become a writer, kept herself sane filling pages with her tiny handwriting, often critically detailing the daily frustrations, irritations, and arguments of eight people surviving together in constant fear.

Today, the visitor squeezes through the entranceway that was hidden from view by a specially built bookshelf and crawls up the steep, narrow staircase into the living quarters (the photo below shows the common room where the group gathered).

There is an eerie sensation as you pause in the hiding place where Anne wrote the diary that has resulted in millions of book sales, plays, and at least thirty film and television productions, including a major Hollywood movie directed by George Stevens in 1959.

These tiny rooms, lit dimly, preserved much as they were in 1944, are real enough. At the same time you have difficulty shaking off the surreal reality of a modern tourist attraction where you are pushed and pummeled by visitors all anxious to have the same experience.

The modern glass structure encased around the original building does not help the atmosphere, nor does the comfortable open-air cafeteria, and the nicely appointed Anne Frank gift shop. Here you can purchase, among other items, copies in many languages of her diary, pictures of Anne on postcards, a cardboard model of the secret annex, an Anne Frank jigsaw puzzle, and, wouldn’t you know it, an Anne Frank tote bag.

What Otto Frank would have thought of all this is anyone’s guess. He was the only member of the group who survived the death camps. Only after he was back in Amsterdam did he learn that everyone else had perished. Anne died of spotted typhus at the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp. She was fifteen.

A friend who had found Anne’s diary in the annex after the arrests held on to it until Otto returned. When he finally brought himself to read it, he couldn’t quite believe this was his daughter. He decided to try and get it published. After a number of false starts and rejections, Diary of a Young Girl was eventually published in 1949. International acclaim soon followed.

Otto, who died in 1980 at the age of 91, did a great deal of editing and trimming to amalgamate the two versions Anne created into a single publishable book. That has fuelled accusations that he wrote the diaries himself. It got to the point where handwriting experts were brought in to verify their authenticity. The original notebooks are on display at the museum.

Curiously, the subject of how Anne and the others were discovered by Dutch police on August 4, 1944, is not addressed in the museum (more information is available on its website). They were all arrested and sent to Auschwitz on what, ironically, was the last train carrying Jews out of Amsterdam. Viewing the artfully constructed bookcase, it is hard to imagine how Anne and her family could have been found—unless they were betrayed. Certainly, that is what Otto Frank believed.

But then who would have betrayed them? All sorts of theories and suspects have been suggested over the years, usually involving an informant calling the police, but nothing has been clearly proven.

A recent investigation by the Anne Frank House suggested an alternative: Police looking for ration-book fraud at the warehouse complex might have stumbled upon the hidden annex in the course of their investigation. Except when you look at that bookshelf, it seems unlikely the hiding place would have been discovered by accident.

Visitors in the summer of 2025 are probably unaware of the mysteries that still swirl around Anne Frank’s life and death. The more than one million people who annually visit the museum are simply drawn to the place where a young girl hid and wrote the diary that created the story that places the Holocaust into intimate tragic focus and continues to inspire generation after generation.

Hard to get into the Anne Frank House; impossible to leave, unmoved.

May 16, 2025

SAVING BOND: The Untold Story of How An Actor and A Journalist Saved James Bond

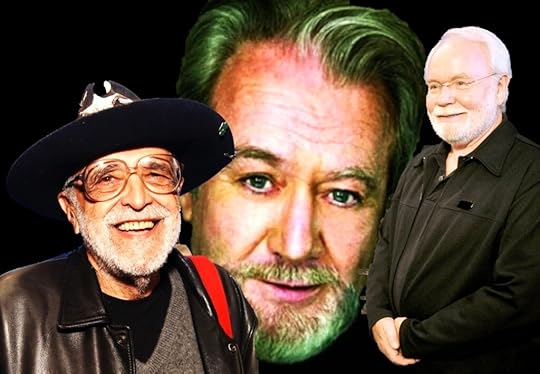

Joe Don Baker

Joe Don Baker

Craig Modderno

Craig ModdernoWhat follows is the untold story of how the actor Joe Don Baker and the journalist Craig Modderno together saved James Bond, with me standing by, slack jawed.

Craig was, to vastly understate the case, a Hollywood character. In all my time in Los Angeles I never encountered anyone quite like him.

With his bird’s nest comb-over and a pasty face that had never seen sunlight, Craig lumbered along, a tall, overweight guy who looked as close to an unmade bed as I’ve ever seen. He lived in a hellhole West Hollywood apartment and drove a beaten-up old shitbox of a car that I was always amazed he could ever get started.

He seemed never to have heard that in order to keep his white shirts white, he had to separate them from the colors in his wash. His baggy jeans were constantly headed for his ankles. He was a vagabond journalist, a very good writer when he wasn’t pissing off his editors for constantly missing deadlines.

What set Craig apart, for me, were his eyes. They were the sharp sly eyes of the accomplished confidence man who knew the room and could play the odds.

Craig befriended me almost as soon as I got to Los Angeles. I quickly discovered that with his endless bravado, an inability to be embarrassed, using a little guile and the sort of authoritative voice that demanded attention, he could get himself in just about anywhere—often with me tagging along, complaining, “Craig, they’re not gonna let us in there, Craig…”

They almost always did.

I had no idea how he did it, but Craig managed to get us invited to a special sneak preview of the latest James Bond movie, GoldenEye.

This was the first public showing of the film. There was huge interest because after the series had lain dormant for several years, it was back starring Pierce Brosnan, making his debut as Agent 007.

Would it work? Would Brosnan and the director Martin Campbell bring new life to what had become a stale franchise? The stakes were high. The future of Bond was riding on GoldenEye.

Craig and I sat through the movie. When it was over, Craig said nothing. I followed him into the lobby. Across the way, Joe Don Baker appeared.

Baker had become famous as Sheriff Buford Pusser in Walking Tall. He had also co-starred in an earlier Bond Movie, The Living Daylights. In GoldenEye he was the chief Bond villain.

“I’m going over to talk to Joe Don,” announced Craig.

“Do you even know Joe Don?” I asked, trailing after him. I should have known better.

“Craig!” Joe Don Baker’s face lit up as Craig approached. “Good to see you, man.”

The two shook hands and Craig introduced me. Baker’s eyes were only for Craig. Hesitantly, he asked, “What did you think of the movie?”

Craig paused, deep in thought. Baker moved in closer, tensing. Craig looked at him and said, “The best Bond in years.”

Immediately, the actor’s florid face flooded with relief. “Jesus, you mean that? The best?”

“It’s terrific, Joe Don,” Craig went on. “Pierce is the best James Bond since Sean Connery.”

“Jesus, man,” Baker said. He whipped around to a baldheaded man standing a few feet away. “Martin,” he called. “Martin, come here, you gotta hear this.”

Martin turned out to be Martin Campbell, the director of the film.

“Martin,” Baker said. “Craig thinks the movie is the best Bond in years!”

It was Campbell’s turn to light up. “You do?”

“Pierce is the best Bond since Sean Connery,” repeated Craig.

“That’s wonderful!” enthused Campell.

He waved over a couple of people who turned out to be producers. Campbell had Craig repeat what he had told him. Everybody broke into big smiles, heartily shaking Craig’s hand. Their joy was palpable. You would think that no one before Craig came along had ever complimented them on the movie.

And maybe they hadn’t.

They group wandered off, practically floating, laughing and talking together. As he left Baker slapped Craig affectionately on the shoulder. “Thanks man,” he said happily. “You saved us, you really did.”

Who knew a badly dressed balding guy who could barely afford to pay for the night’s parking, would have such an effect on a group of high-powered Hollywood filmmakers? But that was Craig. I was in awe. GoldenEye, incidentally, became the big hit that revived the franchise.

I thought of that crazy night hearing the news of Joe Don Baker’s death at the age of eighty-nine.

Craig Modderno died of a heart attack in 2018. He’s in heaven, I’m sure of it.

He talked his way in.

April 13, 2025

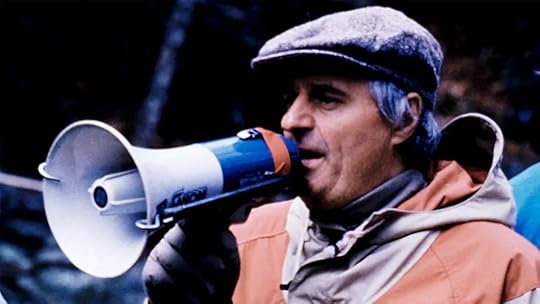

Hooray For Hollywood–and Ted Kotcheff

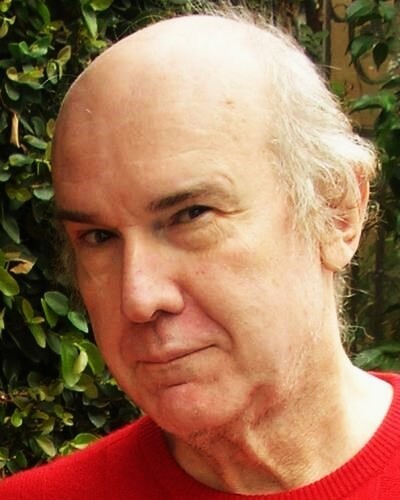

Ted Kotcheff, the Toronto-born filmmaker whose eclectic movie career ranged from the iconic The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz to the commercial phenomenon of First Blood, provided me with a tough lesson in Hollywood realities.

I was reminded of that lesson again last week when the news came of Ted’s death at the age of ninety-four.

Ted had one of those open intelligent faces that invite you to come in, but with Ted, I was to learn, it was unwise to forget that underneath it all was a hard-nosed Hollywood survivor who did what it took to get a movie made—or to make an unwary writer aware of a hard truth or two.

My first real encounter with Ted occurred when I drove down to my hometown of Brockville where he was shooting Joshua Then and Now from the novel by Mordecai Richler. It was a sort of follow-up to Duddy Kravitz, the film that had put writer and director on the map. Ted and Richler had been friends since they were young men down and out in London.

It quickly became apparent when I got to the set and everyone broke for lunch, that Richler’s reputation as a bit of an ass would be on full, rude, arrogant display. Ted, on the other hand, was the soul of friendly diplomacy. I liked Ted. I could have strangled Richler.

Years later I was living in Los Angeles and doing what everyone in Los Angeles seemed to be doing—writing screenplays. Something I had written, a film noirish thriller called First Degree, was making the rounds without much success.

Word came that Ted Kotcheff had read the script and liked it. Ted Kotcheff read a script of mine that he liked? In a town where, I had discovered, it was difficult to get anyone to read anything, let alone like it, this was terrific news.

I phoned Ted and he readily agreed to meet me for lunch. That was a good omen, I thought. Friendly, welcoming Ted who also liked my script. I could hardly wait. Hooray for Hollywood!

We met at Le Dome a French eatery on Sunset Boulevard, at the time tres-chic (Elton John was one of the founders). Ted was a regular. He seemed to know everyone and everyone seemed to know him. After all, he was a big-time Hollywood director. Did I mention that he liked my script?

We sat, ordered lunch and then for the next two hours we talked about everything under the sun—everything except my screenplay. I began to get nervous. Why weren’t we talking about my script, the script Ted Kotcheff liked?

Finally, I cleared my throat, gathered my diminishing courage and said, “I understand you’ve had a chance to read my script.”

“Yes, I have,” Ted allowed. Nothing more than that.

I took another deep breath and asked the question you should never ask in Hollywood: “What did you think?”

“I didn’t like it,” Ted answered matter-of-factly, as though it was a given he wouldn’t like it.

I blinked a couple of times and then said: “Oh.”

“It has all the things I don’t like in a script,” he went on. “Everything seemed artificial and contrived. I like scripts that are grounded in some sort of reality.”

Intuitive soul that I am, I gathered from Ted’s reaction that he was not about to direct First Degree. For the life of me, I couldn’t understand why he even agreed to have lunch, but hey, welcome to Hollywood. I spent a great deal of time out there debating whether I was the worst screenwriter who ever came to town or merely a serviceable hack. That afternoon I staggered out of Le Dome convinced I was the worst.

However, that should never stop anyone in Hollywood and it didn’t stop me. Not long after, something happened to First Degree that almost never happens—it actually got made into a movie starring Rob Lowe presented as a premiere on HBO.

Hooray for Hollywood—and Ted Kotcheff!

Mordecai Richler with Ted Kotcheff

Mordecai Richler with Ted Kotcheff

March 31, 2025

How Does Anyone Get to Look That Good: Remembering Richard Chamberlain

On the set of Murder by Phone

On the set of Murder by Phone“Come and have lunch with me and Richard Chamberlain,” ordered my dear friend Prudence Emery on the phone. Many years later, we would collaborate on a series of mystery novels set in her old stomping grounds at London’s iconic Savoy Hotel.

But at the time, having returned to Canada, she was much-in-demand as a unit publicist for movie productions shooting around the world.

Every so often I would get a call from her. “Basiekins!”—I was always Basiekins—“get on a plane and come to Isreal.” Or, “Basiekins, join me in a snowbank in Barkerville, British Columbia.” Or, “Come and get drunk with Oliver Reed in Montreal.”

This time the marching orders specified lunch with Richard Chamberlain.

He was in town making a now-forgotten thriller called Murder by Phone (it also was known as Bells). Shogun, the ground-breaking television mini-series in which he starred as John Blackthorne was about to be aired. It had yet to erupt into the phenomenon that transformed television—and Richard Chamberlain.

As we sat in a downtown Toronto restaurant once he was finished shooting for the day, he was still best remembered as the twenty-something heartthrob from TV’s Dr. Kildare.

Richard turned out to be a sweet engaging man, forthright about his career. But what struck me more than anything else, even with his John Blackthorne beard from Shogun still in place, was his beauty. I couldn’t keep my eyes off him, thinking, Come on, no one can look that good.

Television and film did not do him justice. Even so, that finely chiseled face with its dramatic cheekbones had not always been helpful. He got the role of Blackthorne by default, he conceded, after Albert Finney and Sean Connery passed.

The hellish months filming in Japan, the unremitting heat, the cultural differences, and the fact he was in nearly every scene in the five-part 180-minute series had taken a toll on him and the entire cast. Having survived what had been an ordeal, he was looking forward to the telecast, hoping that Shogun would bring him more work as a leading man.

He confessed his insecurity about acting on film. For a long time, he doubted his own worth. He felt that he had been unable to shake off a certain distant formality he brought to the roles he played.

The movie stars he knew were at ease in front of a camera. He wasn’t. Sitting in an airport, he read a review by the influential critic, Pauline Kael, in which she said he was foisted off as a movie star but really wasn’t one. The observation stung him to the core.

That was all about to change—dramatically.

Seventy million people would watch Shogun a couple of weeks after we talked. That number exploded to 110 million when he starred in The Thorn Birds.

Today, the producers of what are now known as limited series, would give their eye teeth for a quarter of that kind of mass audience. As the New York Times pointed out in its assessment of Richard’s career, he became overnight “TV’s mega star.”

Reports came Sunday of his death in Hawaii at the age of ninety. Wonderful Prudence exited last year. I’m left with a warm memory of the three of us together at lunch, and me sitting there, unable to stop thinking, How does anyone get to look that good?

February 27, 2025

The Way He Looked: Remembering Gene Hackman

A couple of things that Gene Hackman told me have always stuck in my mind.

Over lunch in Toronto one afternoon, he said that he never turned down any script he was offered. For a major star to admit this was, to say the least, highly unusual. It explained how even then he had made over a hundred movies, more than just about any other leading actor in Hollywood (Michael Caine was a close second).

The other thing he told me was that he never looked at himself on the screen. I told him I couldn’t believe it. After all the great films he had made, Bonnie and Clyde, Downhill Racer, The French Connection, The Conversation, Mississippi Burning, Unforgiven, Superman, not to see any of them struck me as remarkable. “I have this vision of myself and I look pretty good,” he explained quietly, “and then I see this person on the screen and there is someone else entirely. I don’t like him.”

In that moment, he seemed so vulnerable, a gentle, sensitive man trying to explain himself, not at all the tough, authoritative figure he often portrayed in the movies he never saw—the kind of violent roles he said he disliked. He had to be talked into doing both French Connection and Unforgiven.

He had taken time away from acting when I spoke to him for the first time in Niagara Falls where the premiere of Superman II was being held. Gene once again, as he had in the original Superman, was playing the villainous Lex Luthor. He explained he took three years off, worn out from all the movies he had been doing. Later, I spotted him in the gift shop at the hotel where we were all staying. He was standing in line at the checkout, unrecognized, looking a little lost and lonely. I kind of felt sorry for him.

Years later, at our lunch in Toronto, Gene was warm and affable, already at the table when I arrived, not a publicist in sight. By the time we finished, he was doing something very few actors ever do—he was asking me about myself. Of course, nothing was better for my ego. I could be forgiven for thinking we were just a couple of guys sitting around over a good meal, shooting the breeze. I was pouring out my life to him, he was listening intently.

He left our lunch, walking out alone. No one gave him a second glance. He continued to make dozens of movies before doing something else most actors almost never do (hello Harrison Ford, Anthony Hopkins and Clint Eastwood), he stopped. Instead of making every movie he was offered, he decided he would make none and retired to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Hearing of the strange, tragic circumstances surrounding Gene’s death at the age of 95 in the home he shared with his wife in Santa Fe, I fought to ignore all the rumor and speculation swirling around. I remembered that long ago lunch, the warm and gentle man eager to hear from me, the superb actor who hated the way he looked.

Not hard to do.

January 26, 2025

Cult Film: The Failed Canadian Movie That Became A Beloved Classic

“How does a film find an audience?” asks the critic Nathan Holmes who is also an associate professor of Cinema Studies.

“A blockbuster or even a sleeper hit is a rare thing, but rarer still is a film that slowly and surely builds a following over many years, finding its moment much further away from where it started.

“Case in point,” Holmes concludes, “Heavenly Bodies.”

Moreover, journalist and critic Margaret Barton-Fumo, writes enthusiastically that both the movie and its music soundtrack, “survive as treasured cult artifacts today.”

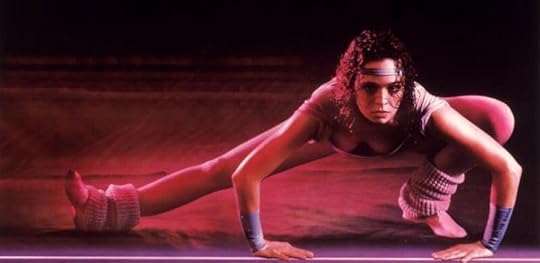

Heavenly Bodies? A treasured cult artifact? The low-budget workout movie accused of ripping off the hit Flashdance with its music, dancing, leg warmers, spandex, and head bands? The Heavenly Bodies I wrote with the film’s director, Lawrence Dane? The Heavenly Bodies released by MGM in February 1985 to a multitude of (Canadian) critical brickbats and then immediately died at the box office?

Yes, that Heavenly Bodies. Those reassessments are occasioned by the recent release by Unobstructed View of a restored 35 mm print on Blu-ray.

I could hardly believe what I was reading.

Does that mean those nasty 1980s critics got it wrong? Maybe they did.

A contemporary critic, Dillon Gonzales, writes of the Blu-ray restoration: “An infectious, effervescent and escapist dramedy, with a non-stop, high-energy soundtrack, it’s no wonder that Heavenly Bodies has become a beloved cable, home videocassette and midnight movie cult classic.”

On Amazon, the Blu-ray version receives an “Amazon’s Choice,” accompanied by rapturous reviews: “I’ve loved this movie forever,” reports one viewer. “A very good and very entertaining film that is never dull and delivers a film experience that is unforgettable,” says another.

Fortified with all this positivity, I sat down the other night with my wife Kathy to watch the restored Heavenly Bodies for the first time since its premiere forty years ago. I wasn’t sure what to expect after all this time. When Larry and I started to write the movie, I wasn’t the Toronto Star’s movie critic. By the time the movie came out, I was. Maybe I was too sensitive, but it seemed my fellow critics took particularly gleeful aim at me. Not that I could really blame them.

As a result, I’ve spent the last four decades trying to duck and run from Heavenly Bodies—with not much success, I should add. Now here it was, back again, resurrected as a much-loved cult favorite in a handsomely restored Blu-ray special edition.

With great trepidation I pressed the ‘play’ button on the DVD player.

Ninety minutes later, did I still see all the flaws that I saw when the movie was released?

Yes, I did.

But I also experienced, perhaps for the first time, the movie’s energy, driven by its infectious oh-so-1980s soundtrack. The dances looked a whole lot better now than they did at the time. The unabashed silliness gives it a kind of old movie innocence. Did Larry and I set out to accomplish that? I’d like to say we did, except we didn’t. But that’s what now comes off the screen.

Best of all, I was reminded of what held Heavenly Bodies together in 1985 and what holds it together today: the charm of Cynthia Dale’s star performance. We quickly realized at the time that she was an incredibly lucky find, the best thing in the movie, and all these years later, she still is. I took pleasure all over again in her tremendous talent as a dancer—and that winning charisma that still leaps off the screen. No wonder everyone who watches the movie falls in love with her.

Could it be that the time had come to stop running away from Heavenly Bodies and embrace it for what it has become for so many?

Not that I’ve got much choice.

My single regret is that Larry Dane, who died a couple of years ago at the age of 84, is not here to enjoy the revival. The movie was Larry’s brain child. He fought hard for it and refused to give up despite the many obstacles (including his co-writer who initially thought it was a terrible idea). He had only 20 days to shoot a movie with many locations and full of complicated dance sequences. He pulled it all off remarkably well.

In another movie that got more attention, Cynthia would have become an international star. As it was, she went on to a fine television career (a long run co-starring in CBC’s Street Legal) and as a musical leading lady at Stratford for thirteen seasons.

The film’s producer, Robert Lantos, whose unsung genius worked to get a low-budget film off the ground and convinced a major Hollywood studio to release it, undaunted by failure, went on to a long career as Canada’s most successful and probably richest producer.

Even I survived, save for a bruised ego, and managed to stumble along writing a lot more films, none of them as well remembered as Heavenly Bodies.

Thanks to the negative reception in print and at the box office, Larry was not allowed to direct again. In retrospect, more’s the shame. He returned to the supporting acting roles that had been his bread and butter throughout his career, but I don’t think he ever quite recovered from the experience of Heavenly Bodies.

He never knew what a beloved cult classic he had ended up creating.

September 30, 2024

His Lonely Way Back Home: Remembering Kris Kristofferson

There are two things I remember vividly from my encounter with Kris Kristofferson.

The first was his frankness about the end of his marriage to singer Rita Coolidge which had happened while he was on location in Montana. “I was jogging fifteen miles a day just so I could get tired enough to sleep.” he told me.

The second thing was his excitement over the movie he had recently shot, an epic western directed by Mike Cimino called Heaven’s Gate.

The production had been plagued by stories of a director out of control, crew mutinies, and cost overruns that had made the movie the most expensive, at $40 million, in Hollywood history. In an all-star cast, Kris was the lead, a lawman caught up in a cattlemen-versus-homesteaders war in the 1890s.

For a 44-year-old singer-songwriter from South Texas who had no acting training, it was easy to see this was a watershed moment for him.

I drove out to Malibu to talk to Kris about Heaven’s Gate. It was due to be released in a few weeks. We were to meet at the home of his friend and Jack-of-all-things-Kris-Kristofferson, Vernon White. Vernon lived in a small house at the bottom of a Malibu hill. Kris lived at the top.

He arrived after jogging along the beach for seven miles and driving his daughter to school. Dressed in a black T-shirt and jeans, he looked rested and fit (down to 155 pounds, the same as he weighed as a golden gloves boxer in college). It was often said of him in those days, but for a guy who had notoriously burned the candle at both ends, he looked pretty darned good.

As we chatted the morning away, he was amiable and forthright about his life—about love and the curious feeling of being single again. He talked at length about the unusual trajectory of his career, the son of an army general who had become a Rhodes scholar, a helicopter pilot ferrying workers around Texas oil fields , a janitor in Nashville, and, finally, an overnight country music sensation as a singer and songwriter who wrote classic hurtin’ songs that had helped so many of us to make it through the night.

He was still surprised by all his good fortune, considering what kind of shape he had been in arriving in Nashville in 1965. “I was on the bottom,” he recalled. “I thought they were going to throw me in jail because I owed my wife and child support. I had no dreams of ever getting on a movie set, although one of the last jobs I had was flying Jim Coburn around to some movie.”

At the end of our time together, he assessed his state of mind: “What a difference a year can make. The sun is shining. The birds are singing. It’s a Walt Disney world out there.”

I drove away hoping for the best for him. Little did either of us know that his Walt Disney world was about to come crashing down.

A few weeks later, Heaven’s Gate had a gala invitation-only premiere at the University Theatre in Toronto. Kris and Michael Cimino were in attendance. I ran into Vernon White in the lobby just before the movie started. He said Kris wanted to say hello after the screening. That never happened.

Three hours and thirty-nine excruciating minutes later, Cimino pulled the movie from release. What at the time was the worst financial disaster in Hollywood history, had opened and closed in a single night. I never spoke to Kris again.

Many years later, however, he and folksinger John Prine were touring together, playing one night at the Barbara B. Mann Performing Hall in Fort Myers, Florida. In company with my brother Ric and his wife, Alicia, we went to see him.

Kris arrived onstage armed only with a guitar and a harmonica. He still looked great, but he stumbled through a series of his classic songs, forgetting lyrics along the way. Later, he revealed that during this period he had been diagnosed with lyme disease which had affected his memory.

Hearing of his death Sunday at the age of 88, the Kris Kristofferson I saw in Fort Myers was not the one I stopped to remember. I preferred to think of the guy whose music over the years had meant so much to me; the movie star sitting in Vernon White’s living room, happy, at least on that morning in Malibu, to be hearing the birds singing in his newly discovered Walt Disney world.

He had taken, like so many of us, every wrong direction, but my hope is that in the end, he got back home to that world safely.