Lona Manning's Blog

September 2, 2025

CMP#226 I'm published in Notes & Queries

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#226 My article about one of Austen's youthful satires now online

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#226 My article about one of Austen's youthful satires now online

I've been juggling a few different topics here at Clutching My Pearls -- my investigation into who wrote the Regency novel The Woman of Colour, sorting out the tangled attribution chains of Mrs. E.G. Bayfield and Mrs. E.M. Foster, and recovering the tragic life of

Eliza Kirkham Mathews

. These three women are forgotten novelists of Jane Austen's era, but perhaps I should also write about Jane Austen now and then as well! After all this is a big anniversary year for her, the 250th anniversary of her birth. There are books and celebrations and articles and lectures galore.

I've been juggling a few different topics here at Clutching My Pearls -- my investigation into who wrote the Regency novel The Woman of Colour, sorting out the tangled attribution chains of Mrs. E.G. Bayfield and Mrs. E.M. Foster, and recovering the tragic life of

Eliza Kirkham Mathews

. These three women are forgotten novelists of Jane Austen's era, but perhaps I should also write about Jane Austen now and then as well! After all this is a big anniversary year for her, the 250th anniversary of her birth. There are books and celebrations and articles and lectures galore. Oh, and--lookee here! One article is by me! My short article, "An inspiration for Austen’s juvenile story Frederic and Elfrida" has been published by the venerable journal Notes & Queries. It's available online but only for those with a subscription or university access.

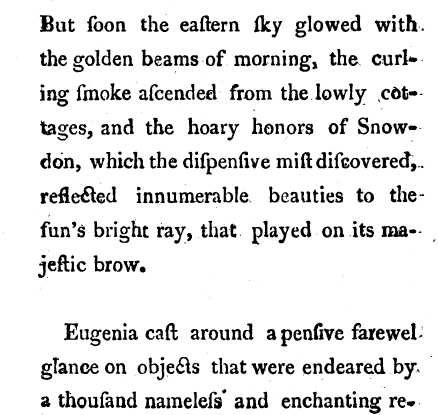

Frederic and Elfrida is a short juvenile piece of Jane Austen's and thought to be one her earliest, composed when she was only eleven or twelve years old. It begins with a satiric poke at the delicate reticence of the sentimental hero and heroine: THE Uncle of Elfrida was the Father of Frederic; in other words, they were first cousins by the Father's side. Being both born in one day & both brought up at one school, it was not wonderfull that they should look on each other with something more than bare politeness. They loved with mutual sincerity, but were both determined not to transgress the rules of Propriety by owning their attachment, either to the object beloved, or to any one else.

My article suggests that the novel Elfrida, or Parental Ambition (1786), which I reviewed here, supplied the names and some of the plot points for Austen's juvenilia, and that we can reasonably assume that young Austen read Elfrida. I picture her reading, or listening to the book as it was read aloud in the family circle, and sharing a laugh with her family members over some of its sentimental excesses.

My article suggests that the novel Elfrida, or Parental Ambition (1786), which I reviewed here, supplied the names and some of the plot points for Austen's juvenilia, and that we can reasonably assume that young Austen read Elfrida. I picture her reading, or listening to the book as it was read aloud in the family circle, and sharing a laugh with her family members over some of its sentimental excesses. I suppose you'd have to be a real Janeite to find this discovery at all interesting! But I am convinced that there are lots of discoveries waiting to be made in the texts of the forgotten novels of the long 18th century. Discoveries about Austen, about women writers, about how English society viewed itself, and about the development of the novel.

Speaking of discoveries, I had already submitted my article when I came across an article by my dissertation supervisor, Professor Jennie Batchelor, sharing the discovery that forgotten novelist Phebe Gibbes was the author of Elfrida. Luckily, I was able to add a footnote to my article.

More discoveries to share in the future! Frederic and Elfrida has been published with a scholarly forward by Juvenilia Press. It is also available in various anthologies of Austen's juvenilia.

Published on September 02, 2025 00:00

August 4, 2025

Back from England

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. Back from England with sore feet and great memories

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. Back from England with sore feet and great memories

My husband and our youngest son joined me for a trip to the UK, touring Edinburgh, St. Andrews, York, Oxford, and London. Had to put my feet up and rest after we got home! In London, we stayed in Bloomsbury, near Brunswick Square. Janeites will know why that matters.

My husband and our youngest son joined me for a trip to the UK, touring Edinburgh, St. Andrews, York, Oxford, and London. Had to put my feet up and rest after we got home! In London, we stayed in Bloomsbury, near Brunswick Square. Janeites will know why that matters.One reason for my visit--to walk in my graduation ceremony for my Masters degree (by research) from the University of York. The "by research" part means I wrote a dissertation for my degree and did not take classes. I did it as a distance student, under the encouraging supervision of Professors Alison O'Byrne and Jennie Batchelor. My dissertation looks at Austen's use of novel tropes in Emma (such as Harriet as the long-lost foundling heroine and Jane Fairfax being rescued from drowning).

While there, I visited some more locales that I had put into my novels but have never been to! Last year, I visited the site of the Peterloo Massacre and St. Pancras church. This time I went to St. James's Park in London, where Fanny Price is taken hostage in my second novel, A Marriage of Attachment. On this return trip, I got to visit libraries in York and Oxford to continue my research into the lives of some forgotten female authors.

On our narrowboat cruise in the canals of London.

On our narrowboat cruise in the canals of London.  Victorian splendour at the Museum of Natural History in Oxford. Beautiful building and so nice to see parents showing the displays to their children.

Victorian splendour at the Museum of Natural History in Oxford. Beautiful building and so nice to see parents showing the displays to their children.  St. Andrews castle at St. Andrews, home of the famous golf course. A beautiful day, as you can see from the photo.

St. Andrews castle at St. Andrews, home of the famous golf course. A beautiful day, as you can see from the photo.  Do you like cemeteries? I highly recommend Brompton cemetery in London.

Do you like cemeteries? I highly recommend Brompton cemetery in London.  The compact and colourful Chinatown in London.

The compact and colourful Chinatown in London.  Left: We have majestic, towering groves of old growth forests in British Columbia. But we don't have cathedrals with vaulted ceilings rising up halfway to heaven.

Left: We have majestic, towering groves of old growth forests in British Columbia. But we don't have cathedrals with vaulted ceilings rising up halfway to heaven.  Botanic Gardens at Oxford. Thanks to my son Joe for all the best photos.

Botanic Gardens at Oxford. Thanks to my son Joe for all the best photos.  A pot of tea and a delicious scone with clotted cream and jam (mixed together so you can't tell what went on first) aboard a narrowboat in London.

A pot of tea and a delicious scone with clotted cream and jam (mixed together so you can't tell what went on first) aboard a narrowboat in London.  Right: I saw this lady, who looks like a dead ringer for 1995 Mrs. Gardiner in my opinion, during my 2024 visit to England. It is at the Merchant Guildhall in York.

Previous post:

Off to England

Right: I saw this lady, who looks like a dead ringer for 1995 Mrs. Gardiner in my opinion, during my 2024 visit to England. It is at the Merchant Guildhall in York.

Previous post:

Off to England

Published on August 04, 2025 14:34

July 11, 2025

Off to England

I am busy packing up for another trip to England and won't have time to blog for the rest of the month. Below are some photos of a trip my husband and I took last year to Ireland, Wales and England. In Manchester, I visited the site of the Peterloo Massacre, an event I wrote about in my third novel, A Different Kind of Woman. A lowlight was staying at a posh B&B in Wales and feeling that the host regarded me as riff-raff. The house was much nicer than Fawlty Towers but the welcome wasn't so nice. But overall, we had a wonderful time--entranced by the beauty of the scenery in Ireland and Wales.

I am busy packing up for another trip to England and won't have time to blog for the rest of the month. Below are some photos of a trip my husband and I took last year to Ireland, Wales and England. In Manchester, I visited the site of the Peterloo Massacre, an event I wrote about in my third novel, A Different Kind of Woman. A lowlight was staying at a posh B&B in Wales and feeling that the host regarded me as riff-raff. The house was much nicer than Fawlty Towers but the welcome wasn't so nice. But overall, we had a wonderful time--entranced by the beauty of the scenery in Ireland and Wales.I am making lots of interesting research discoveries and am happily rabbit-holing. I'll be visiting some archives in the UK. Back soon!

Trinity Library, Dublin

Trinity Library, Dublin  A private library in Manchester

A private library in Manchester  A train festival in Wales

A train festival in Wales  Yorkminster

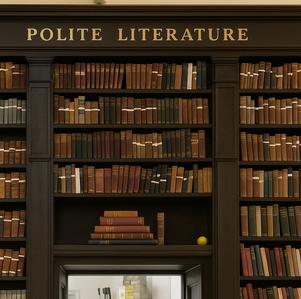

Yorkminster  A tribute to Mary Wollstonecraft at Trinity Library, so much better than that monstrosity they erected at Newington Green

A tribute to Mary Wollstonecraft at Trinity Library, so much better than that monstrosity they erected at Newington Green  Visiting St. Patrick's at Evensong. Upside, transporting music. Downside, I think this is where I caught COVID.

Visiting St. Patrick's at Evensong. Upside, transporting music. Downside, I think this is where I caught COVID.  Peterloo Massacre memorial

Peterloo Massacre memorial

Only another researcher can understand the pleasures of taking a seat at a library and digging in...

Only another researcher can understand the pleasures of taking a seat at a library and digging in...

Published on July 11, 2025 00:00

June 24, 2025

CMP#225 "Their lives were short, but lovely"

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#225 The mysterious deaths of EKM's teen cousins

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#225 The mysterious deaths of EKM's teen cousins

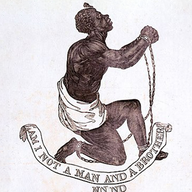

Frontispiece for Ellinor. I suspect this is a reused etching from an older book. I've uncovered more information about the life and family of obscure writer Eliza Kirkham Mathews (referred to

in this blog as EKM

). Her aunt Sarah Strong lost her husband Richard in 1786, when her children were still young. But he seems to have left her financially secure, as compared to EKM's mother Mary, whose husband George was also an apothecary. Although raised in genteel circumstances, EKM was poverty=stricken and alone in the world, receiving very little help from her better-off relatives. EKM left her native Devon and ended up in Wales, working as a teacher. There she met the youthful comic actor Charles Mathews who was struggling to make a name for himself on the theatre circuit. They married in September, 1797. That same month, Eliza got heart-wrenching news from her aunt Sarah; her teenage cousins, Sarah Amelia and Maria, had both died within a few days of each other, in an inexplicable fashion.

Frontispiece for Ellinor. I suspect this is a reused etching from an older book. I've uncovered more information about the life and family of obscure writer Eliza Kirkham Mathews (referred to

in this blog as EKM

). Her aunt Sarah Strong lost her husband Richard in 1786, when her children were still young. But he seems to have left her financially secure, as compared to EKM's mother Mary, whose husband George was also an apothecary. Although raised in genteel circumstances, EKM was poverty=stricken and alone in the world, receiving very little help from her better-off relatives. EKM left her native Devon and ended up in Wales, working as a teacher. There she met the youthful comic actor Charles Mathews who was struggling to make a name for himself on the theatre circuit. They married in September, 1797. That same month, Eliza got heart-wrenching news from her aunt Sarah; her teenage cousins, Sarah Amelia and Maria, had both died within a few days of each other, in an inexplicable fashion.EKM’s writing contains many autobiographical elements, and this tragic tale found expression in one her elegies (quoted below) and was narrated in one of her children's books.

Ellinor, or, the Young Governess was published in 1802—the year EKM died--by the York publisher, Thomas Wilson & Son, who also published more children’s books posthumously. This suggests that EKM approached this local publisher in the final years of her life with some of her novel manuscripts, and was encouraged to write some children’s books instead. Her earnings, if any, would have been meagre, but it was better than nothing. Paint-by-numbers children's books

Producing a children’s book, in those days, was not so very difficult. As I’ve learned, authors simply plagiarized freely from popular poets, biographers, historians and books of natural history. They interspersed these plundered lessons within a morally improving narrative. Another case of a plagiarized children’s book is discussed here. In Ellinor, as is typical, a governess corrects the faults of the children in the Selby household while giving them mini-lectures about ducks, evaporation and rain (cribbed from Goldsmith’s Natural History), Demosthenes and Richard the Lion Heart, (from Dodd’s The Beauties of History), and Archbishop Fenelon (from Augustus Toplady).

But one of the story's moral lessons is from the pen of EKM herself--the story of her cousins. This occurs when the Selby family receives a letter and Lady Selby calls her children to attention to hear the news:

“My dear children,” said Lady Selby, “you were well acquainted with the beautiful Maria, and Emily.”

“O yes, Mamma,” said Amelia; “I have often envied their extreme beauty.”

Well of course, Lady Selby can't let that pass by unremarked, and lands on her little daughter like a ton of bricks: “Envy is a vile passion, Amelia, and expressive of a weak mind.” Then she tells Ellinor to read the letter aloud, which she does:

ChatGPT image. “An affecting circumstance has happened here, which I wish to relate. Maria and Emily were, as you know, two of the most lovely young women within the circle of your acquaintance; Their beauty and accomplishments have long been the topic of conversation, in the gay and fashionable society which they frequented; they were surrounded by every luxury which the most unreasonable could desire, and received a tribute of flattery to their charms, such as might have gratified the vainest. The delight of their fond mother, she indulged them in every wish of their unexperienced hearts. About a week since, a splendid ball was given by the officers -------, at which the lovely Maria and Emily were invited. The day arrived, and was spent in preparations for their making an elegant appearance at the ball; the evening drew near; the lovely sisters were decked in all the brilliancies of dress and fashion.

ChatGPT image. “An affecting circumstance has happened here, which I wish to relate. Maria and Emily were, as you know, two of the most lovely young women within the circle of your acquaintance; Their beauty and accomplishments have long been the topic of conversation, in the gay and fashionable society which they frequented; they were surrounded by every luxury which the most unreasonable could desire, and received a tribute of flattery to their charms, such as might have gratified the vainest. The delight of their fond mother, she indulged them in every wish of their unexperienced hearts. About a week since, a splendid ball was given by the officers -------, at which the lovely Maria and Emily were invited. The day arrived, and was spent in preparations for their making an elegant appearance at the ball; the evening drew near; the lovely sisters were decked in all the brilliancies of dress and fashion.Emily, the youngest, was already arrayed; one moment her eyes elicited the fire of youth and health, and the blush of her cheeks showed the bright glow of the damask rose; the next, an ashy paleness overspread her countenance. She complained of a violent pain in her stomach, and was advised by Maria to apply to her mother for some cordial restorative. Racked with the most excruciating pain, she quitted her chamber, entered with difficulty the drawing-room, and dropped in strong convulsions at her mother’s feet. Alarmed by the shrieks which the unhappy parent sent forth, Maria flew to the drawing-room, where she found the once beautiful Emily, the fondly beloved sister of her heart, in the agonies of death. From that moment, Emily never breathed a syllable, and died the next morning, at ten o’clock. To paint the speechless agony of sorrow the poor Maria endured, is beyond the power of language.

The third day after Emily’s death was appointed for her funeral. It was impossible to prevent the noise and bustle which bringing her lifeless remains over the stairs occasioned, from reaching Maria: She heard the death-like sound, uttered a piercing shriek, and instantly expired in the arms of her distracted mother.”

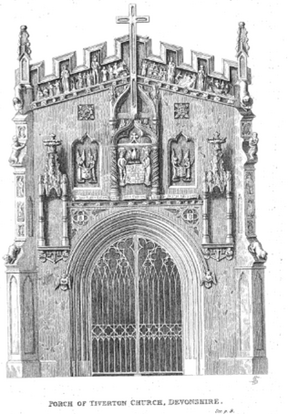

Former office of Wilson & Spence, EKM's publishers, Google Maps "Strictly True"

Former office of Wilson & Spence, EKM's publishers, Google Maps "Strictly True"EKM added in a footnote, *These affecting incidents are strictly TRUE—The young ladies were nearly related to the Author, and have not been dead three years."

Through genealogical (parish) records, I was able to confirm that Sarah Amelia and Emily Strong were EKM's first cousins and they died in 1797. There may be an error in the transcription of records, because both girls were buried on the 25th, but one was buried in November and the other in September. I’d like to see a copy of the original parish record from St Peter church in Tiverton, because I am inclined to believe EKM when she says her account was “strictly true” and that Maria died a few days after Sarah Amelia. Maria was 19 years old and Sarah Amelia was 16. "Three years" since their death means that EKM was writing Ellinor in 1800, at the same time she was preparing her novel What Has Been for publication.

Charles Mathews' second wife, in her memoir of her husband, suggested that EKM published only one novel and hid her other manuscripts from her husband, but the evidence suggests that this just isn't true. She must have had several children's books being prepared for publication before her death. I can picture her walking from her little apartment on Stonegate in York to the offices of Thomas Wilson & Son (aka Wilson & Spence) on High Ousegate, clutching a manuscript or some corrected proofs--at least before she was too ill with tuberculosis to go anywhere.

As for the cause of her cousins' deaths, at first I supposed that Sarah Amelia had died of appendicitis, but in re-reading the passage, I must say that poisoning comes to mind as a possible cause of death for both sisters. The story also suggests, as I mentioned, that Sarah Strong was better-off than her impoverished sister-in-law, EKM's mother, if she was able to indulge her daughters in "every luxury." A cautionary tale

EKM uses the deaths of her cousins for a moral purpose, in accordance with Christian doctrine that one should live acceptably in the eyes of God so as to be judged worthy of heaven. After listening to the tragic tale, "[E]very one present expressed a conviction of the necessity... of living in a constant preparation for death… The sudden death of Maria and Emily, had such an effect on the mind of Henrietta... that what love of virtue could not bring to pass, fear did. She was continually thinking how terrible it would be to die in an unprepared state; and therefore studied to be good and virtuous."

But alas, little Frederick…. He was “proud, obstinate and cruel,” and none of the admonitions and punishments he gets are sufficient to save him from his early death. He disobeyed his parents and fell into the pond, dying three weeks later. “During his illness, he expressed the utmost contrition for his past follies, and hoped that every child would learn from his fate, that wickedness and disobedience to parents, never go unpunished.” Thus at least we understand that Frederick will not go to the Bad Place when he dies.

The dire tone of these children's books may come as a surprise to modern readers. But Ellinor, or, the Young Governess is quite typical in meting out death to a disobedient child, pour encourager les autres.

In a future post, more about EKM's books for children. And now, time to strum the lyre

I left the poetry for last, to make it easier to skip over... here is an extended excerpt from the elegy EKM wrote for her cousins, which appeared in Ellinor and in a posthumous book of her poetry.

St Peter, Tiverton, Devon, where members of the Strong family were baptized and buried. (1828 Gentlemens Magazine)

Elegy on the Deaths of Maria & Sarah Amelia Strong

St Peter, Tiverton, Devon, where members of the Strong family were baptized and buried. (1828 Gentlemens Magazine)

Elegy on the Deaths of Maria & Sarah Amelia Strong

The midnight breeze sighs hollow thro’ the glade,

And wearied nature’s wrapt in soft repose;

Pale melancholy courts the gloomy shade,

And piteous tells her tale of many woes.

Now let the muse her solemn station seek,

On yon fall’n ruin, desolate and drear,

In sacred song, with resignation meek,

Breathe her sad numbers to the humid air…

O! death! Insatiate monster! Mortals dread,

Why drink the heart’s blood of the young and gay;

Why come in cunning ‘guise with silent tread

To crop those maids—sweet as the vernal day;

Chaste as the lilly—gay as the vermeil rose,

Light as the rein-deer, sprightly as the fawn;

The LOV’LY SISTERS every charm disclose!

Pure as the silver tints of early dawn.

Allur’d by pleasure’s bland enchanting call,

They sought the mazy, gay, fantastic train;

Smil’d at the concert—grac’d the festive ball,

Their young hearts throbbing to the tuneful strain,

While innocence was their’s—and sportive mirth,

And filial tenderness, and innate worth.

Maria! Emily! Lamented nymphs!

Who lately bloomed in all the pride of youth…

What, tho’ no trophied honours round them shine,

Love’s HOLY TEAR shall gem the turfy sod,

Maternal tenderness sigh o’er their shrine,

And resignation point our hopes to God!

To innocence like their’s ecstatic bliss is given,

Virtue’s unerring sure reward is heaven. EKM adds, “Theirs was the gaiety of innocence: No malignant passions destroyed the tranquility of their bosoms: their lives were short, but lovely.” Previous post: I gave a talk about Jane

Published on June 24, 2025 00:00

June 19, 2025

CMP#224 My visit to Victoria

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#224 Speechifying in Victoria

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#224 Speechifying in Victoria

A toast to Jane: "Blessed be her shade"! I recently spent a weekend with the Jane Austen Society of North America--Victoria Chapter to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Austen's birth. Celebrations and special events are planned for all over the world, but Victoria is an especially beautiful place for Janeites to gather together. The weather was fabulous, sunny but not too hot, and many participants were decked in their best Regency finery.

A toast to Jane: "Blessed be her shade"! I recently spent a weekend with the Jane Austen Society of North America--Victoria Chapter to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Austen's birth. Celebrations and special events are planned for all over the world, but Victoria is an especially beautiful place for Janeites to gather together. The weather was fabulous, sunny but not too hot, and many participants were decked in their best Regency finery. The weekend featured knowledgeable speakers talking about crafts, quilts, and fashions in Austen's time. I met some fellow authoresses of JAFF (Jane Austen fan fiction). We are all research junkies, I think. We love learning more about Regency life and putting these events in context for our readers.

The theme for the conference was "The Wit and Wisdom of Jane Austen," so I turned to some research I've posted here on my blog, concerning the social and even religious strictures against female wittiness in Austen's time. Since Austen knew she was a superb comic genius, what was it like for her to live in a world where moralists and authors of conduct books basically condemned female wittiness?

I really enjoyed sharing my research with a knowledgeable audience of Janeites. Who else would get my Fordyce's Sermons joke?

Jane with attitude

Jane with attitudeI was too busy listening to the interesting talks and enjoying myself to take many photos, but Michelle S. of our Vancouver chapter pulled us together for a group photo of the Vancouver delegation. That's my power point presentation behind us. "Snarky" Jane Austen was created by feeding the standard prettified version of Jane Austen into Chat GPT and asking for a snarky version of her. Victoria is a city with heritage architecture in a gorgeous natural setting. It is also a city famed for its gardens. Our ingathering reception was held at beautiful Goward House, placed amongst the arbutus trees in a quiet road near the university. The back yard was peaceful and gorgeous, my photo doesn't do it justice. The view from the breakwater near the conference venue was just stunning, and the Costume promenade on Sunday morning drew a lot of local publicity! I'm always so impressed by the detail and creativity that the costumers put into their elegant ensembles!

A peaceful evening at Goward House, Victoria, BC Thanks to all the volunteers of JASNA Victoria for all the hard work they put into making this event happen! Jane lies in Winchester, blessed be her shade!

A peaceful evening at Goward House, Victoria, BC Thanks to all the volunteers of JASNA Victoria for all the hard work they put into making this event happen! Jane lies in Winchester, blessed be her shade!Praise the Lord for making her, and her for all she made.

And while the stones of Winchester—or Milsom Street—remain,

Glory, Love, and Honour unto England's Jane!

-- Rudyard Kipling

Published on June 19, 2025 00:00

June 17, 2025

CMP#223 Another great tale from Allie Cresswell

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#223 The Standing Stone on the Moor, another engrossing tale from Allie Cresswell

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#223 The Standing Stone on the Moor, another engrossing tale from Allie Cresswell

I just had the pleasure of losing myself in the new release of Allie Cresswell's Talbot family series. Allie Creswell has created another story that pulls you into a different world with her skilful evocation of time and place—in this case, a small village on the Yorkshire moors during the Industrial Revolution, when the labouring classes of England were moving from their isolated farms to crowded tenements and the "dark satanic mills." What I love about Allie's heroine, Beth Harlish, is that she is not as a raving beauty. She's nice-looking, but her qualities of intelligence and character are what make two men fall in love with her. This romantic triangle was so exquisitely balanced that I had no idea who would prevail until the very end.

I just had the pleasure of losing myself in the new release of Allie Cresswell's Talbot family series. Allie Creswell has created another story that pulls you into a different world with her skilful evocation of time and place—in this case, a small village on the Yorkshire moors during the Industrial Revolution, when the labouring classes of England were moving from their isolated farms to crowded tenements and the "dark satanic mills." What I love about Allie's heroine, Beth Harlish, is that she is not as a raving beauty. She's nice-looking, but her qualities of intelligence and character are what make two men fall in love with her. This romantic triangle was so exquisitely balanced that I had no idea who would prevail until the very end. Allie keeps her storylines and all her varied characters in motion and you just want to keep turning the page. It's no easy feat to create so many vivid and distinct characters. It's almost Dickensian.

Another thing I really love about Allie’s historical fiction is her descriptions of every day life. With her skillful touch for the telling detail, you are right there, moving between a desolate group of Irish refugees from the Great Famine, to the dangerous depths of a Yorkshire coal mine, to the cloistered lives of genteel spinsters, to the brash, crude, rising class of the newly-prosperous mercantile class and the impoverished nobility clinging to their rank and privileges. Beth Harlish navigates a society dominated by class barriers and open bigotry. She follows her own convictions of right and wrong, but the most important person in her life—her brother Frank—turns her world upside down.

The Standing Stone on the Moor can be read as a stand-alone novel, but I suspect that after finishing it, you will want to turn to the other books in the Talbot family trilogy.

If you haven't read any Allie Cresswell and you are a Janeite, you will enjoy her Emma prequel, the Highbury Trilogy. I also loved The House on Winter Moss, in which--as with this book--the weather is a character in the novel. The north Yorkshire coast was a hotbed for smugglers bringing in luxury goods like tea and wine to avoid taxation. Smuggling is featured in The Standing Stone in the Moor. Here is an article about the Yorkshire smugglers and their techniques--sort of a smugglers' how-to. Previous post: The wealthy aunt who didn't help her nieces

Published on June 17, 2025 00:00

June 10, 2025

CMP#222 Rich Relations & Great Expectations

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP# 222 Rich widowed aunts and disappointed legatees

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP# 222 Rich widowed aunts and disappointed legatees

Jane Leigh Perrot at the time of her trial When you are a country clergyman of modest means with a large family, prudence requires that you stay on good terms with your wife's wealthy relations. So it was with the Rev. George Austen, his wife Cassandra, and his wife's relatives, the Leigh Perrots. The Austens lived in expectation and hope of receiving an inheritance from the childless Leigh Perrots (see Brenda Cox's blog post for an explanation of the family tree and the monies involved). When Mrs. Leigh Perrot was arrested in 1799 for shoplifting Mrs. Austen offered to send Cassandra and Jane to keep her company while she was held awaiting trial but the offer was declined. (She was acquitted). When the Rev. Austen retired, he and his family moved to Bath--where the Leigh Perrots lived. And, I wouldn't be at all surprised if Mrs. Austen dissuaded Jane from looking for a publisher for her novels for fear that the Leigh Perrots wouldn't like it, but that is speculation.

Jane Leigh Perrot at the time of her trial When you are a country clergyman of modest means with a large family, prudence requires that you stay on good terms with your wife's wealthy relations. So it was with the Rev. George Austen, his wife Cassandra, and his wife's relatives, the Leigh Perrots. The Austens lived in expectation and hope of receiving an inheritance from the childless Leigh Perrots (see Brenda Cox's blog post for an explanation of the family tree and the monies involved). When Mrs. Leigh Perrot was arrested in 1799 for shoplifting Mrs. Austen offered to send Cassandra and Jane to keep her company while she was held awaiting trial but the offer was declined. (She was acquitted). When the Rev. Austen retired, he and his family moved to Bath--where the Leigh Perrots lived. And, I wouldn't be at all surprised if Mrs. Austen dissuaded Jane from looking for a publisher for her novels for fear that the Leigh Perrots wouldn't like it, but that is speculation.The Austens were to be disappointed. When James Leigh Perrot died in 1817, he left everything to his wife. This happened near the end of Jane Austen's life and in fact, she believed the bad news set her health back. Mrs. Leigh Perrot lived on until 1836.

The Austens were not the only family to be disappointed by the last will and testament of a wealthy relative. The same blow fell--even more severely--upon authoress Eliza Kirkham Mathews, then Eliza Kirkham Strong. I will continue referring to her as "EKM" even though for this part of her story, she is "EKS." Faithful readers of this blog know I have written about EKM's life and her poetry and novels before. This is not because she has earned a significant place in the history of the novel. The only slight scholarly notice she has received is owing to her heroine in What Has Been, who tries to earn money by writing a novel. (EKM returns to this theme in a sub plot in Griffith Abbey). My affectionate interest in EKM first arose because I thought her poetry was maudlin, then I realized I had been too harsh on her because her life story truly was tragic. Now I'm hooked on delving up as much information as I can about her via the internet. I love a research rabbit hole. At any rate, here comes another sad chapter from EKM's life. It's easy to see how Eliza’s tragic experiences informed her writing...

Croan House, Egloshayle, Cornwall, in 1960, Country Life magazine, Vol 128 A disappointed legatee

Croan House, Egloshayle, Cornwall, in 1960, Country Life magazine, Vol 128 A disappointed legateeEKM's mother Mary was a Kirkham, a large, respectable and landed family in Devonshire. She married George Strong, an apothecary/surgeon who must have been moderately successful but who fell on hard times before his death. And he was evidently the son of a tradesman--a reasonably prosperous tradesman, but still! You can imagine how that went down with the Kirkhams. It's rather like Mrs. Price in Mansfield Park.

Mrs. Strong's oldest brother Fraunceis Kirkham owned lands in Exeter and Cornwall, including Croan House in Egloshayle, which he acquired when he married the heiress Damaris Hoblyn in 1751.

George and Mary Kirkham Strong named their first-born son George after his father but their second son was named Francis Kirkham Strong. Fraunceis Kirkham died in 1770 leaving Eliza’s Aunt Damaris a wealthy widow with a carriage and a houseful of servants. No doubt her sister-in-law Mary Kirkham Strong hoped that some of that wealth would find its way to her own family, especially after her husband George's business failed and the family sank into poverty. The last will and testament of another of Mary Kirkham Strong's siblings gives us a glimpse into the troubles of the Strong family. When Elizabeth Kirkham died in 1781, she left legacies of one hundred pounds to a niece and nephew. But her sister "Mary Strong, wife of George Strong, apothecary," received an annuity of five pounds per year, to be placed "in the hands of my said sister," for the rest of "her natural life." The other relatives could be entrusted with their entire inheritances, but the money was to be doled out to Mary. One certainly suspects that Elizabeth wanted to prevent Mary's husband George getting his hands on it, or perhaps it was to protect it from George's creditors.

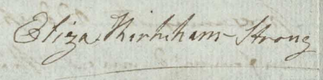

Damaris Kirkham survived her husband by almost 25 years, dying in March of 1794. By then Mary and George Strong had also died, their sons Francis and George were dead, and their daughter Mary was dead, leaving Eliza (EKM) alone in the world. Eliza, then 23 years old, wrote a pleading letter to the executor of her aunt’s will. I discovered this letter in the Cornwall (Konsel Kernow) archives and have transcribed it below:

She addresses a "Mr. Tremayne" and she mentions a "Mr. Tincombe," who is another one of her uncles, married to her Aunt Henrietta Kirkham Tincombe. Knowing you are the executor of the late Mrs. Kirkham of Croan; an Orphan Legatee impressed with an idea of yr Benevolence, and [honour?] presumes to address you, -- Mr. Tincombe sometime since informed me that my Aunt Kirkham had in her Will, bequeathed to my late revered Mother, sixty one guineas, my sister, and self 20 each; as Heiress to both, am told I can claim these legacy’s.

I trust [?] this is legal, as I am poor, --a hundred guinea’s would to me be of infinite service, were I rich, never would I intrude on Mr. Tremayne but poor and an Orphan, I appeal to his humanity and flatter myself no objection will be raised to this claim.

I never offended my Aunt – yet she left me, the niece of a much-loved husband, less than her servants, this astonishes me as I have heard her benevolence was unbounded, believe me Sir I do not repine, my Sainted Mother was a bright example of patience, she taught me to be submissive to the Will of Heaven, in her steps I would fain tread, -- I trust Sir you’ll peruse with an eye of Christian Humanity the request of an Orphan—And “may that Being who is a Father to the Fatherless, reward you for it.”

–I am Sir with every good wish,

yr humble Srvnt,

Eliza Kirkham Strong.

It looks like EKM pleaded in vain for the legacies intended for her late mother and sister. On the outside of the letter, a clerk jotted a note that £20 was remitted to Eliza, in keeping with Damaris Kirkham’s will. Or perhaps it was an additional £20, over and above the £20 she had already been given. The relevant section of Damaris Kirkham's will reads: “Also give unto my Sister in Law Mary Strong widow of George Strong Surgeon late of Exeter the sum of fifty guineas to be paid at the end of six months after my decease and I also give twenty pounds to each of her two Daughters Mary Strong and Elizabeth Strong to set them up in some Business the said twenty pounds to be paid to them each one year after my decease.”

It looks like EKM pleaded in vain for the legacies intended for her late mother and sister. On the outside of the letter, a clerk jotted a note that £20 was remitted to Eliza, in keeping with Damaris Kirkham’s will. Or perhaps it was an additional £20, over and above the £20 she had already been given. The relevant section of Damaris Kirkham's will reads: “Also give unto my Sister in Law Mary Strong widow of George Strong Surgeon late of Exeter the sum of fifty guineas to be paid at the end of six months after my decease and I also give twenty pounds to each of her two Daughters Mary Strong and Elizabeth Strong to set them up in some Business the said twenty pounds to be paid to them each one year after my decease.”

Lucky legatee: Rev. Henry Hawkins Tremayne (1741-1829) A measly twenty pounds apiece “To set them up in some Business”? Clearly Auntie Damaris believed that Mary and Eliza should resign all pretensions of belonging to the genteel class, despite being Kirkhams on their mother's side. Like EKM's frosty Mrs. Elton in What Has Been, Mrs. Kirkham thought that Mary and Eliza should get busy with their needles and become milliners or seamstresses.

Lucky legatee: Rev. Henry Hawkins Tremayne (1741-1829) A measly twenty pounds apiece “To set them up in some Business”? Clearly Auntie Damaris believed that Mary and Eliza should resign all pretensions of belonging to the genteel class, despite being Kirkhams on their mother's side. Like EKM's frosty Mrs. Elton in What Has Been, Mrs. Kirkham thought that Mary and Eliza should get busy with their needles and become milliners or seamstresses.The late lamented Damaris Kirkham

Damaris Kirkham bequeathed monies to dozens of people to purchase mourning clothes and mourning rings in her memory. She left forty pounds to be distributed amongst the poor of Elgoshayle. She gave her carriage-driver, who had a large family, a small yearly annuity. Her housekeeper, footman, dairy maid, gardener and housemaid got, so far as I can make out, five or ten pounds apiece along with the said monies for mourning clothes. In a codicil, she also left some furniture to her housekeeper. So yes, the widow Kirkham definitely had a closer and more affectionate relationship with her servants in Cornwall than she did with her sister-in-law or her nieces. There were no keepsake mourning rings for the Exeter branch of the family, either. The loss of her own sons and daughter in childhood did not incline her to be generous to her nieces.

Eliza's mother may have been thrown off by her family when she made her imprudent match to a man of undistinguished pedigree. Or, for all we know, her brother Francis had already stepped in to help the Strong family just as Sir Thomas Bertram helped the Prices in Mansfield Park. Perhaps they felt they had done enough. Perhaps a rift arose later. Or perhaps Mrs. Kirkham was just not interested in her late husband's side of the family and only felt close to her own family.

At any rate, an 1867 history of Cornwall explains that Damaris Hoblyn “[m]arried Francis Kirkham, Esq., of the Cornwall Militia; and having buried her husband and all of her children, she bequeathed his and other estates to her cousin, the Rev. Henry Hawkins Tremayne."

Croan House passed down through the Tremayne family for several generations and still stands today. The Rev. Hawkins was already well-to-do, thanks to the death of his older brother and his marriage to an heiress. He was not a blood relation of the Strong family of Exeter, and may have felt no connection with them. EKM made her feelings clear about rich people who wouldn't help their poor relations in What Has Been.

Jane Austen's family always insisted that her characters were not portraits of real people. I have trouble believing that she resisted that temptation. Perhaps Fanny Dashwood of Sense and Sensibility and Lady Denham of Sanditon are partly based on real, disagreeable, rich relations.

Church of St Petroc, Egloshayle, Derek Harper Fiction imitates life

Church of St Petroc, Egloshayle, Derek Harper Fiction imitates lifeAnd yes, I noticed that EKM uses the possessive apostrophe "S" when she should be using the plural. I am also surprised that she uses the same idioms and ideas that dominate her poems and her fiction--poetic language and resignation to the will of God.

In a short postscript to her letter, EKM told Mr. Tremayne that she was going to London "in a few days." She doesn’t explain why, but one assumes she planned to make the rounds of the publishers with some manuscripts, or a collection of her poems. Her interactions with publishers are referenced in What Has Been and Griffith Abbey.

EKM's first book of poetry, published by subscription (i.e. crowdfunded by benevolent people), came out the following year. Most of the subscribers are from Exeter, and a few are from Cornwall, including Lady Molesworth, the owner of a stately home near Elgoshayle, but "Tremayne" does not appear on the subscriber list. The Tincombes bought three copies.

Eliza Kirkham Strong met Charles Mathews in Swansea while she was working as a schoolteacher. They were married in September 1797 and lived mostly in Hull and York, until her death in 1801.

Janeites lament that so many of Jane Austen's letters were destroyed after her death--but in comparison to many obscure authoresses of the period, we have an absolute treasure-trove of biographical material. At least, by identifying EKM as a niece of Fraunceis and Damaris Kirkham, I have filled in her family genealogy on her mother's side.

In her fiction, EKM gave herself the inheritance she was denied in real life.

Previous post: Who wrote Griffith Abbey? Clifford, H. Dalton. “Far From the Madding Crowd,” Country Life, July 28, 1960, pp 196-197.

Polsue, Joseph. A Complete Parochial History of the County of Cornwall: Compiled from the Best Authorities & Corrected and Improved from Actual Survey ; Illustrated. United Kingdom, W. Lake, 1867.

The Kirkhams family was laid to rest in St. Petroc churchyard. The church bells of this ancient church inspired a Cornish folksong, "The Ringers of Elgoshayle."

Published on June 10, 2025 00:00

June 3, 2025

CMP#221 Which Mrs. Mathews?

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#221 Who Wrote the 1807 Novel Griffith Abbey?

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#221 Who Wrote the 1807 Novel Griffith Abbey?

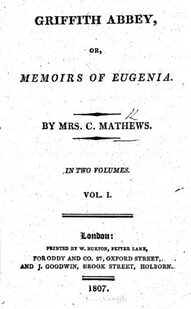

The novel was republished in the US in 1808, probably pirated. I've been doing a deep dive on the works of a forgotten female author of Austen's time, Eliza Kirkham Mathews (EKM) (1772-1802), trying to confirm or disprove her authorship of novels published in a time span covering her teenage years, to years after her death. Recently, I

gave a synopsis

of the 1807 novel Griffith Abbey, a domestic-sentimental-historical novel with some Gothic touches. The author is given as "Mrs. C. Mathews." Scholars have differed in their attributions. Does "Mrs. C. Mathews" refer to EKM, the wife of Charles Mathews, or is it "Mrs. Charlotte Mathews," an authoress who published two novels before 1800?

The novel was republished in the US in 1808, probably pirated. I've been doing a deep dive on the works of a forgotten female author of Austen's time, Eliza Kirkham Mathews (EKM) (1772-1802), trying to confirm or disprove her authorship of novels published in a time span covering her teenage years, to years after her death. Recently, I

gave a synopsis

of the 1807 novel Griffith Abbey, a domestic-sentimental-historical novel with some Gothic touches. The author is given as "Mrs. C. Mathews." Scholars have differed in their attributions. Does "Mrs. C. Mathews" refer to EKM, the wife of Charles Mathews, or is it "Mrs. Charlotte Mathews," an authoress who published two novels before 1800?To answer this question, I am using an approach which so far as I can tell hasn't been tried before--I actually read Griffith Abbey. I wanted to see if it resembles EKM's style in What Has Been, (a novel she undoubtedly wrote) or does it more closely resemble the style of Mrs. Charlotte Mathews, authoress of the 1794 novel Simple Facts, or, The History of an Orphan?

There are many similarities between these two authoresses--both the Mrs. Mathews tended to move their stories along at a brisk pace, unlike, say, Charlotte Smith or Mary Meeke, two popular writers who could turn out novels of four or five volumes. Both featured heroines who are orphaned and end up marrying their childhood sweethearts. But there are many such similarities between all novels of this era. You can scarcely ever find a heroine with two living parents. These stories all feature the travails of unimpeachably virtuous heroines, they stress Christian morality and they use the same narrative tics and plot points... Stylistic similarities

In this example from Griffith Abbey the narrator issues a warning when the hero rejoices over his engagement to Eugenia: “Ah! Erring youth! Sanguine, short-sighted Edmund, you thought not of misfortune, even when its ebon train was quickly approaching!” Likewise, in Simple Facts: “[Mrs. Harcourt] considered her little Maria, as a blessing from heaven…How little do mortals know the designs of heaven? –Could that tender parent have foreseen the distresses her beloved child was born to undergo, how different would have been her feelings?” And this, from Eliza Kirkham Mathews' What Has Been: “Frederick knew not then the misery in store for him; he knew not to what dreadful acts of atrocity the baser passions can lead the human mind.” And there are many such common traits. Many authors sprinkled little quotes throughout their narration, as in this example from What Has Been: “As Emily read this letter, she 'heaved no sigh, she shed no tear,' and, when she had finished reading it, sat stupidly grazing on it, insensible to every thing around her.”

And this example from Simple Facts: "Maria grew a beautiful child, and early discovered uncommon abilities; her tender mother undertook the delightful task ‘to teach the young idea how to shoot.’”

As for plot points, threats to chastity are ubiquitous, as are the impediments around class and riches that keep the hero and heroine apart until the happy ending. Heroines refuse to surrender their virtue to the wiles and designs of the villain. In What Has Been, the hero is briefly abducted to get him out of the way; in Griffith Abbey, the heroine is nearly abducted. In Simple Facts, the heroine is abducted and, to her credit, rescues herself. Both What Has Been and Griffith Abbey have women who go insane over losing the men they love, in Simple Facts, a nobly-born disappointed male suitor runs off and lives like a hermit.

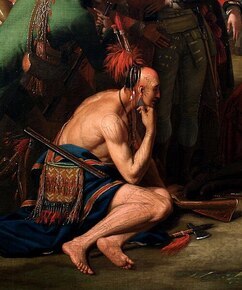

Sensibility for the sublime Chatgpt image Thematic differences:

Sensibility for the sublime Chatgpt image Thematic differences:But there are some discernable differences between Simple Facts and EKM's novels. EKM is an adherent of the cult of sensibility; in What Has Been, the "good" people in the book cannot step outside, or even look out of a window, without being transported by the beauties of the natural world. Likewise, Eugenia and Mrs. Evans in Griffith Abbey are "delighted with the sublimities of nature, [and] enjoyed the most refined and exquisite sensations while journeying over the tremendous hills of Scotland." Contrariwise, as scholar Ernest James Lovell explained, "a villain can take no delight in nature." In What Has Been, the heroine's aunt fails this test. She is “a good-natured though a weak woman" who agrees to walk with Emily along the western cliffs near Teignmouth, "at the same time remarking, she could not imagine what delight any body could take in ascending those frightful cliffs."

This critical test is not applied to heroine Maria Harcourt in Simple Facts. she does not exclaim over the scenery when she travels to Bath; rather, she is transfixed by the sight of a young hermit living in a hut, the one who turns out to be thwarted in love. Apart from that, "nothing worthy [of] notice happened the remainder of their journey."

Grammatical comparisons

I used artificial intelligence to compare Simple Facts with What Has Been, then I asked, does Griffith Abbey most closely resemble What Has Been or Simple Facts? Grok concluded that "Griffith Abbey’s sentence complexity, with longer sentences and frequent subordinate clauses, closely resembles What Has Been."

Here is an example of a sentence combining descriptions of nature with a complex sentence structure from Griffith Abbey: "Entering a cavern in the cliff, (hewn by the hand of hoary time,) from whence they had an extensive view of the expansive ocean, (whose lucid bosom reflected innumerous hues, the bright tinged purple, the lustrous silver, and the pallid green, till lost in the haze of distance) the little party seated themselves; and Eugenia lifted with fixed attention to Captain Donald, who now offered to relate all he knew of the fair maniac’s history.”

(For more about the sentence structure of What Has Been, see this earlier face off between What Has Been and the novel Constance.)

The sentences in Simple Facts are simpler and more straightforward, and are less apt to begin with an adverbial clause: ”Maria was received by her uncle and cousins with great pleasure, they at first shewed her every kind of attention, and Mrs. Young took a pleasure in hearing her praised. But her youngest daughter soon discovered a jealousy at her superior abilities, which she considered as a reproach to herself, and therefore conceived a violent hatred against her.”

Despite the clear differences, Grok AI concluded that one author could have written all three novels, if the greater sentence complexity and darker dramatic tone of the later novels reflected an evolution of the writer's style from 1794 to 1807. But I was holding back some crucial information from Grok AI... Biographical evidence for authorship

Mrs. Charlotte Mathews wrote Simple Facts and we know EKM wrote What Has Been. While EKM is undoubtedly the author of What Has Been, EKM was not "Mrs. Mathews" in 1794 when Simple Facts came out. She was Miss Strong and hadn't even met Charles Mathews back then. So she couldn't be the Mrs. Mathews who wrote Simple Facts.

We know that EKM was dead when Griffith Abbey came out, and look how the publisher advertised the novel:

Eliza's self-portrait

Eliza's self-portrait It would help if we knew Charlotte Mathews' life dates--was she also dead by 1807? Unfortunately, we don't know anything about her. However, we have another good reason for concluding that Griffith Abbey is a posthumous publication by EKM. She put a self-portrait into Volume II, in the person of a genteel girl fallen on hard times. The hero Sir Edmund, visiting friends while nursing his broken heart, is moping around Devonshire [which was EKM's home county] and notices “a young woman weeping over some papers which she held in her hand.” She awakes his compassion to an “exquisite degree.” It starts to rain so he approaches her cottage and asks to wait out the rain. He notices that the gentility of Eliza Dudley and her widowed mother is at odds with their poverty. “[E]very thing he saw, every sentence he heard, uttered by either of the strangers, increased his astonishment, and assured him they had seen brighter days”

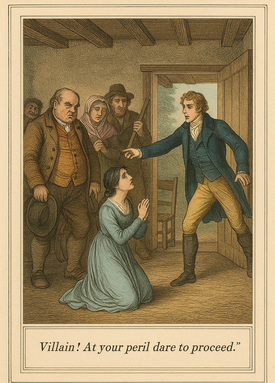

The next day, he is passing by when he overhears the mother and daughter begging for mercy from a bailiff, who snarls: “This is quarter-day, as you well know, and Mr. Heartless, the squire’s steward, says as how he must be paid… if you can’t these here honest fellows must take your goods. So, Dick and Roger, you may begin to remove.”

Sir Edmund interposes: “Villain! At your peril dare to proceed."

He pays the overdue rent, then we learn the backstory of the distressed mother and daughter. Mrs. Dudley explains she was reduced to living on thirty pounds a year with her only surviving child, Eliza, after her husband was killed by “an epidemical disorder.”

“My Eliza possesses many useful and elegant accomplishments, which she has endeavoured to turn to advantage, but small have been the emoluments arising from her industry. Nature has liberally bestowed on her talents, which, till lately, I flattered myself would have been of infinite service to her but alas! genius, unpatronized by the great, too often withers in obscurity. Much time and attention has she lately bestowed on a novel which, I hoped would have afforded us at least transient comfort.

“The publisher to whom she sent it received it with cool politeness, and at length returned it, saying he could not think of sending into the world a work in which he discovered few merits, unless she could prevail on some well-known literary character to patronize it. Alas! my child is a child of obscurity; ‘the world forgetting, by the world forgot.’ Her poetical talents are far from despicable, and her genius for other works of taste, vivid, elegant, and refined; yet of what service are these, without powerful friends."

The mother's description of Eliza's failure to find a publisher is surely an echo of the setbacks that EKM herself met with in her efforts to find a publisher, and resemble the travails of the heroine in What Has Been.

The mother's description of Eliza's failure to find a publisher is surely an echo of the setbacks that EKM herself met with in her efforts to find a publisher, and resemble the travails of the heroine in What Has Been.The real Eliza did find a patron for her final volume of poems, published posthumously. She was granted permission to dedicate the volume to the "Right Honourable [Charlotte] the Countess Fitzwilliam." (who is pictured at left in a portrait by Joshua Reynolds). I don't know how EKM came to the Countess's attention, but it must have been a final gratification for her before her death.

So I think this autobiographical subplot in Griffith Abbey settles the matter. Charlotte Mathews is not Mrs. C. Mathews. It pays to read the novel, you never know what you might find!

For more about the plot of Griffith Abbey, see here. For more about Eliza Kirkham Mathew's sad life story, see here and see here. One other thing--the sincerest form of flattery

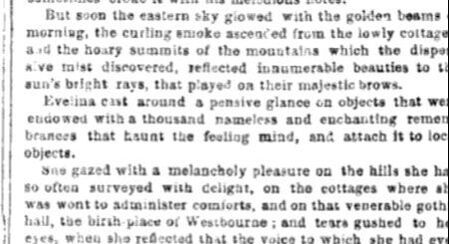

I haven't been very complimentary about EKM's writing skills, so it's only fair to tell you that someone thought she was worth plagiarizing from. An anonymous author writing a serialized novel for Lloyd's Entertaining Journal in 1847 must have had an old copy of Griffith Abbey on hand. The two passages I noticed were descriptions of scenery. Here is one of them--the left hand side is Evelina the Pauper's Child, on the right is Griffith Abbey. No doubt there were other borrowings.

I think EKM would have been flattered!

I haven't provided a synopsis or review of Charlotte Mathews' Simple Facts but I will return to this novel in the future in an extended discussion of fainting in these old novels.

I haven't provided a synopsis or review of Charlotte Mathews' Simple Facts but I will return to this novel in the future in an extended discussion of fainting in these old novels. Previous post: Griffith Abbey synopsis

Published on June 03, 2025 00:00

May 26, 2025

CMP#220 "Rears and Vices" rears up again

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I report on 18th-century attitudes that I do not necessarily endorse.

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I report on 18th-century attitudes that I do not necessarily endorse.This blog post is a deep dive on one single phrase in Mansfield Park. CMP#220 Once more into the breech (ha!) with "Rears and Vices"

Jonny Lee Miller and Embeth Davidtz in the 1999 film version of Mansfield Park. I am interrupting my

examination of the works

of Eliza Kirkham Mathews, for which I interrupted my examination of the authorship of The Woman of Colour, to clutch my pearls so hard that my knuckles whiten over a recent headline in the British newspaper The Telegraph. ‘Don’t change books to be more PC--that’s like cutting Jane Austen’s buggery joke.”

Jonny Lee Miller and Embeth Davidtz in the 1999 film version of Mansfield Park. I am interrupting my

examination of the works

of Eliza Kirkham Mathews, for which I interrupted my examination of the authorship of The Woman of Colour, to clutch my pearls so hard that my knuckles whiten over a recent headline in the British newspaper The Telegraph. ‘Don’t change books to be more PC--that’s like cutting Jane Austen’s buggery joke.”In this article, Paula Byrne, an eminent and telegenic Austen scholar, once again asserts that Mary Crawford’s dinner-party quip about “rears and vices” in Mansfield Park is a pun about sodomy. She, and millions of other Austen fans, evidently take enormous pleasure in repeating this. In fact, I have the impression that it is now received wisdom. So by protesting, I mark myself as a pedantic killjoy, and I’m throwing myself open to accusations of being a homophobic prude. Even if I’m right, a lot of people want to believe it anyway. It’s a prime exhibit in the gallery that proves Jane Austen was a rule-breaker, a gal after our own hearts and our own enlightened principles.

Despite knowing how invested so many of my fellow Janeites are in this ribald notion, I am going to reiterate why I think it just can’t be true...

A different age: "The Cully Flogg'd," 1680 erotic print, British Museum The Morals of the Age

A different age: "The Cully Flogg'd," 1680 erotic print, British Museum The Morals of the Age I cannot provide any positive evidence that this interpretation is mistaken. I can only give the arguments against, as Brian Southam and a few others have already done.

At the time of Mansfield Park’s publication, cultural mores dictated that all novels be subjected to strict scrutiny about their morals. Reviewers almost always mentioned whether a novel they were reviewing held up a strict moral lesson, and they condemned or praised novels on that basis. Authors often assured their readers that their only motive for writing a novel was to convey a moral lesson. Austen didn’t go for that kind of performative virtue-signaling, but her earliest reviewers praised the chasteness of her language and the inoffensiveness of her subject matter. There is, unfortunately, no contemporary review of Mansfield Park, but for Emma, for example, an 1816 reviewer praised the: “complete purity of ideas and images which is here conspicuous.”

Women and girls were the chief consumers of novels. In a cultural regime like this, a publisher would have been insane to sabotage his business by publishing a novel with a ribald joke in it.

I grew up reading second-wave feminist tracts which asserted that well-bred Victorian girls didn’t know the facts of life on their wedding night. Now I am supposed to accept that Regency virgins would understand a pun about sodomy? All right, suppose they would. Dr. Byrne has pointed out that Jane Austen knew what sodomy was because she made a joke about the king James I of England in her juvenilia and she had two brothers in the Navy. Granting both points, it does not follow at all that she’d be reckless enough to publish a sodomy joke in a novel notable for its earnest morality.

Johnson's Dictionary, 1st and 4th editions The unmentionable vice

Johnson's Dictionary, 1st and 4th editions The unmentionable viceSodomy as a subject was unmentionable. Absolutely unmentionable, as far as I can see. We’re not talking about Chaucer’s England, or the London underground, or Regency slang, or even the more rollicking age of Aphra Behn and Henry Fielding. Never mind, either, the experience of thousands upon thousands of British boys in boarding school. We’re talking about books marketed during the Regency period to the genteel class. Mansfield Park is not a joke-book to be laughed over by men sitting together with their bottles of port. It's a seriously profound novel about self-deception, virtue and vice.

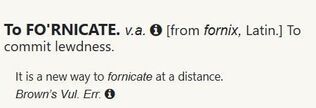

If buggery was alluded to in the popular press, say, in relation to a criminal matter, the writer used disparaging euphemisms such as “an odious and unnatural vice, which decency forbids us to mention,” or “a sin against nature,” which is hardly an explanation. Check here for a Google ngram for the frequency of the word "paederasty." And while we're at it, "pederasty." I can't find the terms "pederast" or "Sodom" or "buggery" in Dr. Johnson's dictionary. Nor does "rear" appear as a slang word for "buttocks". So I guess Blackadder was wrong when he quipped people would only use the dictionary to look up rude words. Or if they did, they would not be enlightened as to details.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, in discussing the practise of pederasty in Ancient Greece, wrote: “The laws of modern composition scarcely permit a modest writer to investigate the subject with philosophical accuracy.” The libertarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham wrote an essay arguing that homosexual acts should not be a capital crime, as they were at the time, but he buried it in his desk drawer, unpublished until 1978. The subject was unmentionable outside of a criminal legal text. A pun about sodomy would be as unthinkable in polite society in Austen's time as a racist joke about disparate crime levels would be today. A close reading of the text

So, what happened after Mary Crawford made her sodomy joke? Let’s review—or “interrogate,” as the kids say--the conversation in which the joke arose, in Chapter 6. Mary laughingly complains about the time her uncle wanted to landscape a cottage when they were living in it: “for three months we were all dirt and confusion." The narrator tells us “Edmund was sorry to hear Miss Crawford, whom he was much disposed to admire, speak so freely of her uncle. It did not suit his sense of propriety.” Then he gets all pedantic on Mary when she talks about not being able to get a farmer’s cart and horse to convey her harp to Mansfield. Finally, she makes her “rears and vices" joke, and we are told, “Edmund again felt grave, and only replied, ‘It is a noble profession.’”

The next day, Edmund asks Fanny, “But was there nothing in her conversation that struck you, Fanny, as not quite right?” Fanny does not say, “Yes, I almost fell off my chair when she made that sodomy pun about admirals!” She says, “Oh yes! she ought not to have spoken of her uncle as she did. I was quite astonished.” So the things that most disturbed Fanny was Mary's comic speech about her ”honoured uncle.” The sodomy joke doesn’t even come in second. The next thing Fanny resents is that Mary made a witty generalization about how all brothers write short letters.

Details about this print given below Probing deeply

Details about this print given below Probing deeplyI have applied the usual research methods I use when a scholar asserts that a phrase in Austen is an allusion to such-and-such a thing. For an example, see my research on the “Lord Mansfield” allusion in Mansfield Park. I search the literature of the time to study the phrase in context and to see how other writers used it. But I've come up with next to nothing.

Mary Crawford was not employing a phrase ("rears and vices") in common use, so far as I can discover in a search of the digital archives of university databases. I found only one example in Google Books, from Baily's Magazine of Sports and Pastimes, in 1868: “The Yachting Congress was a great success, an infinity of Commodores, Rears, and Vices taking part in the proceedings.” There, I think, the usage is innocent, though some may disagree.

I have come across only one example of the “rear,” (specifically the "rear" in “Rear Admiral”) used as a pun for “backside,“ arising in connection with a brawl involving two naval officers. When serving under Captain George Vancouver (no pun intended), young Lord Camelford was flogged for giving an “Otaheitean Venus,” that is a young woman of Tahiti, “a piece of old iron,” as reported in the St. James Chronicle for 1796. Back in England, Lord Camelford challenged Vancouver to a duel, which he refused. An enraged Lord Camelford attacked Vancouver in the street.

According to a biography of Camelford, The Half-Mad Lord, Vancouver escaped Camelford’s assault but did not escape derision for cowardice. ‘”Over the next few weeks a series of accounts and malicious squibs, clearly inspired by Lord Camelford’s friends, began to appear in the newspapers. There were suggestions that Vancouver, following his chastisement, should change his name to Rear-cover. [The "rear" as opposed to the "van"]. Worse puns were to follow with telling effect; for example, in the True Briton on 24 and 26 October 1796. ‘’Lord Camelford can boast of a power which rivals that of the First Lord of the Admiralty—He has made Captain Couver a yellow rear’’ (This pun was an allusion to the rank of Yellow Admiral: the next promotion to which Vancouver might aspire).”

Chatgpt image So, what is the joke?

Chatgpt image So, what is the joke?The obvious rejoinder is-- so, if Mary Crawford was not referring to sodomy, what was her pun about? I cannot find a plausible explanation, and I have looked in the vast Austen scholarly literature universe for an answer.

If I came across any other novel of this era that contains a sodomy joke, or any countervailing evidence of any kind, or any worthwhile arguments, I will post my findings. But I don’t expect to find anything.

Finally, authors of the day, including females, joked about effeminate men, as I’ve posted about here, but I haven't come across any examples of anyone who named, described, or alluded to homosexual activity in a three-volume novel. By the way, I've never found a sympathetic or earnest portrait of a homosexual either. Effeminate men are comical creatures, like spinsters, or fat women. If we were really going to approach this in the modern manner, someone ought to denounce Mary's joke, and by extension Austen, as being problematic. James Gillray satirical print of Vancouver and Camelford, courtesy British Museum.

In addition to making fun of everyone involved for this encounter, the cartoon pillories Vancouver for being corrupt and too strict with his men. Vancouver punished Camelford for giving away ship's property, a piece of iron which was valuable to the Tahitians, no doubt with the intent of inducing a native girl to sleep with him. The British Museum's explanatory note: "The stout officer, Captain Vancouver, wears an enormous sword; a fur mantle hangs from his shoulders inscribed 'This Present from the King of Owyhee to George IIId forgot to be delivered'. From his coat-pocket hangs a scroll which rests on the ground, part being still rolled up: 'List of those disgraced during the Voyage - put under Arrest all the Ships Crew - Put into Irons, every Gentleman on Board - Broke every Man of Honor & Spirit - Promoted Spies - ' His left foot is on an open book: 'Every Officer is the Guardian of his own Honor. Lord Grenvills Letter'. From the pocket of the civilian (Vancouver's brother) projects a paper: 'Chas Rearcovers Letter to be publish'd after the Parties are bound to keep ye Peace.' Vancouver's assailant, Lord Camelford, says: "Give me Satisfaction, Rascal! - draw your Sword, Coward! what you won't? - why then take that Lubber! - & that! & that! & that! & that! & that! & - Vancouver, staggering back, with arms outstretched, shouts: Murder! - Murder! - Watch! - Constable! - keep him off Brother! - while I run to my Lord-Chancellor for Protection! Murder! Murder! Murder". Behind him, on the ground, lies a pile of shackles inscribed 'For the Navy'. Two very juvenile sailor-boys stand together (left) watching with delight. On Vancouver's right is the lower part of a shop (right) showing a door and window in which skins are suspended. Round the door are inscriptions: 'The South-Sea-Fur-warehouse from China. Fine Black Otter Skins. No Contraband Goods sold here.' After the title: 'Dedicated to the Flag Officers of the British Navy.' 1 October 1796."

The Canadian city of Vancouver is of course named after George Vancouver, who pushed himself and his men to carry out the exhausting work of rowing all around the British Columbia archipelago, surveying and mapping the territory. His story is told more sympathetically in Madness, Betrayal, and the Lash, by Stephen Brown.

"While [Jeremy] Bentham published his political ideas widely, his personal papers found after his death contained hundreds of pages of writings on the issue of homosexuality, which remained unpublished for more than 140 years. Homosexuality, under British law, was defined as 'buggery' and punishable by death in Britain, France, and much of Europe. The word 'homosexual' itself was not used in eighteenth and early nineteenth century English; "paederast" was the preferred term."

"Offences Against One's Self: Paederasty ." Gender Issues and Sexuality: Essential Primary Sources. . Encyclopedia.com. 5 May. 2025 <https://www.encyclopedia.com>. Aldrich, R., & Wotherspoon, G. (Eds.). (2001). Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History Vol.1: From Antiquity to the Mid-Twentieth Century (1st ed.). A good article about Jeremy Bentham and the arguments in his essay. Routledge. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/10.4324/9780203986752

Cumming, Ed. “Don’t change books to be more PC--that’s like cutting Jane Austen’s buggery joke’: Writer Paula Byrne on celebrating 250 years of Austen, her obsession with literature and how a series of poison pen letters changed her life.” The Telegraph, 25 May 2025.

Review of Emma, Monthly Review, July 1816.

Tolstoy, Nikolai. The Half-mad Lord: Thomas Pitt, 2nd Baron Camelford (1775-1804). Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1979.

Published on May 26, 2025 00:00

May 20, 2025

CMP#219 Eugenia the forsaken heroine

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I report on 18th-century attitudes that I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#219 Synopsis: Griffith Abbey (1807), by Eliza Kirkham Mathews--or not?

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I report on 18th-century attitudes that I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#219 Synopsis: Griffith Abbey (1807), by Eliza Kirkham Mathews--or not?

Sublime Welsh scenery I am examining the

novels attributed