M.V. Clark's Blog

January 1, 2022

The zombie keeps the score

I often get asked what the heck The Splits is about and I can never really answer that question.

This is a terrible position to be in if you want people to read your book.

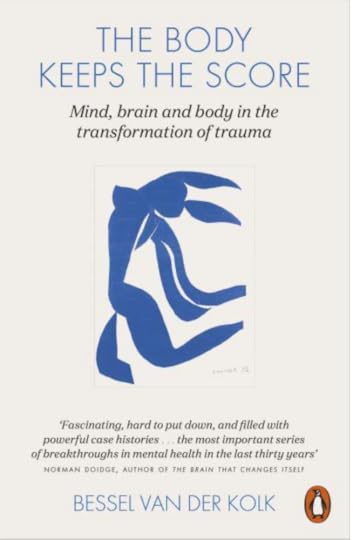

Recently I was reading The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk and I realised I might finally have found a way of explaining it - to myself as much as anybody else.

In a nutshell, The Splits (the book) is about a disease called ‘the Splits’. And that disease is an allegory for mental illness.

What now? I haven’t read The Splits.In case you haven’t read the book, let me set the scene a little. First off, the world of the Splits is not post-apocalyptic. It is exactly like our own, except that a mysterious zombie plague is endemic. After Covid that’s really not too difficult to explain!

Second, the zombie plague is a bit different from what people are used to.

My starting point for the Splits disease was a question asked by my kid - where do zombies’ minds go? Remember that the original Haitian zombies were simply empty bodies. They weren’t visibly decomposing nor were they trying to eat people like Romero zombies. That wasn’t the point of the original zombies. The point was that they were mindless, puppets controlled by voodoo masters, ruthless plantation owners or both.

I didn’t find it too hard to find the answer to my kid’s question - ghosts. Ghosts are feelings that won’t go away - hate, anger, sadness, love.

So in The Splits, humans who catch the zombie plague shatter into two - a mindless body and a disembodied mind - a zombie and a ghost. The two parts behave very differently - the zombies are gruesome and murderous and they gather to destroy whole parts of London. The ghosts are much less tangible. They stay on the margins, teasing at people’s sanity. They spread unease and transiently revive lost loves.

What has this got to do with The Body Keeps the Score?So what has this got to do with a book by a a psychiatrist about trauma? Haven’t I just explained what the Splits is about? What more is there to say?

In The Body Keeps the Score, Van der Kolk talks about how the idea of trauma developed in the 20th century, starting with war veterans who suffered from shell shock. It was then understood that children could be traumatised by abuse, and that even adults with good childhoods who had never been to war could be traumatised by extreme events - like violent attacks or natural disasters.

Van der Kolk describes trauma as a situation where you are in great danger physically or mentally or both, but you cannot take any action to get yourself to safety. You are immobilized. In such situations, your only option is to shut down and stop feeling anything.

What all these kinds of trauma do, says Van der Kolk, is prevent people from living in their bodies.

He describes a study which asked people to ‘think of nothing in particular’. It found that in people who hadn’t been through trauma, the ‘self-sensing’ part of their brain was activated. In other words, they thought about their bodies. Yet in the traumatized people, this part of the brain did not get activated. This was because it was shut down by trauma.

I am simplifying here, but essentially Van der Kolk says that because this ‘self-sensing’ part of the brain is shut down in people with trauma their minds and bodies don’t communicate.

This means that traumatised people often don’t realise they are in danger, because they can’t read the signals from their bodies that are telling them they are in danger. Sadly, because of this they are more likely to find themselves in dangerous situations.

At the same time, they can’t read the signals from their bodies telling them that they are safe. So they can’t enjoy a perfectly safe and fun situation like a family dinner. They ruin it by being numb or getting triggered by something that isn’t really a threat.

Okay but what has THAT got to do with a novel about zombies?The first link is this. The Body Keeps the Score describes minds and bodies that are seperated in some sense, that aren’t communicating. So does The Splits.

And look at these descriptions van der Kolk uses to describe traumatised people:

They simply went blank

Hollow-eyed men staring mutely into a void

Blank stares and absent minds

She just walked around with a vacant stare

Caving in, feeling hollow

Ute discovered that she could blank out her mind

The blanked out [kids] don’t bother anyone, and are left to lose their future bit by bit

I’m reminded of the original, pre-Romero zombies of Haiti, who are representations of one of the ultimate traumas, slavery.

Van der Kolk also describes how the behaviour of profoundly traumatised people lacks aspects of what makes us human (their behavior, not the people themselves):

Kittens, puppies, mice and gerbils constantly play around, and when they’re tired they huddle together, skin to skin, in a pile. In contrast, the snakes and lizards lie motionless in the corners of their cages, unresponsive to the environment. This sort of immobilization, generated by the reptilian brain, characterizes many chronically traumatized people.

I don’t know about you, but this description of unresponsive reptiles, oblivious to their surroundings, also reminds me of zombies.

One of the people Van der Kolk writes about, who was sexually abused by a preist as a child, describes literally ‘feeling like a zombie’ as he began to remember what had happened to him.

In another section, van der Kolk describes how the experience of being immobilized, which is at the root of most trauma:

Your heart slows down, your breathing becomes shallow, and, zombielike, you lose touch with yourself and your surroundings. You dissociate, faint and collapse [my italics].

So that’s the first reason why The Body Keeps the Score helps explain The Splits. One of the meanings carried in the trope of the zombie is that of trauma and how it shuts down our minds.

There’s more. In The Splits, scientists vie to find a biological explanation for the disease, and eventually settle on a molecule called a prion. But despite this apparent scientific triumph, I decided that there would be no definitive biological explanation for the Splits.

In the book, a journalist asks a maverick researcher about what causes the Splits. Here is their exchange:

Journalist: What is the cause?

Researcher: Trauma.

Journalist: Trauma?

Researcher: Yes. Psychological injury in early childhood, or in adulthood, or both. Physical injury too, if it’s sufficiently frightening. Being attacked by an infected is enough of a trauma for most people to contract the disease, so it appears to be transmitted by biting. But actually the cause is psychological.

So that’s the second reason why The Body Keeps the Score helps explain what the Splits is about. Because The Splits was already about trauma, long before I came across Van der Kolk’s book.

I still don’t get it. Give me an example in terms of one of your characters.The journalist in my book is called Anna. Anna is not obviously a zombie, nor is she obviously traumatised. But she was brought up by a very cruel mother. It is also part of her character that she is numb, unemotional, and what she does feel is quite strange.

Van der Kolk describes how attachment between caregiver and baby creates the communication between mind and body that trauma destroys. We only know what we feel as babies because our caregiver reflects it accurately. For example, if a baby is comforted when it cries it will know that it is sad, that this is normal, that it is okay to be sad, and that other people can help you be less sad. But if a baby gets hit when it cries it will learn it is dangerous to feel sad. If a baby gets ignored when it cries it will learn that its sadness is of no interest.

Anna has not had a healthy attachment to her mother. We know this from the first page of the book, when she says she would like to kill her mother, because she is giving a detailed description of stillbirth to Anna’s heavily pregnant sister. We also hear about the mother’s panicky, hysterical reaction to Anna’s first menstruation and to her daughters beginning to wear bras. It is as if Anna’s mother wants to attack her daughters’ creative and reproductive abilities at every turn.

When Anna has a baby of her own, a little boy called Danny, she struggles to establish a healthy care-giving attachment.

One day I lifted [Danny] and he smiled at me, a goofy helpless smile, happiness in its purest form. A voluptuous feeling slid over me and through me, but it wasn’t joy. It pulsated and penetrated, it seemed to lift my stomach and hands and upper lip, it seemed to rifle through my hair, stroke between my legs. Little shit – having fun, was he? I put him down and placed my hands on my head.

She just can’t respond appropriately to how he feels, even when he’s being about as gorgeous as any baby can be. This isn’t her fault, and to give her some credit, on some level she realises what is going on and she battles down her worst impulses.

Anna’s husband disappears just after she gives birth (read the book to find out why) and a little later she is visited by her mother-in-law Maureen. Anna is surprised by Maureen’s warmth, the generous rhythm of her conversation.

“I’m not here to take over,” [Maureen] said. “I just want to help you find him. And to get to know Danny a little bit.”

Then she stopped speaking, which surprised me. It was as if she was giving me a turn.

But Anna doesn’t have the Splits, you may say. Well, during the story it is discovered that the Splits is a spectrum disease. It is possible to have subtle symptoms that are invisible to anyone else and reveal themselves only in your behaviour and how you feel.

Parts of your mind are shut down, placed in a ghostly limbo, and your relationship with your body is simultaneously diminished. I think this is what Anna has, or is. We can see that the trauma that has caused her to have the splits is her terrible mother.

Interestingly, Ann spends the whole book terrified that she has the Splits and that she will ‘turn’ at any moment. I always thought she was wrong about this, but now I wonder if she doesn’t know herself better than the author.

Here is a summary of what the heck Splits is about in light of The Body Keeps the Score. The Splits is about the relationship between trauma and how it splits apart our minds and bodies. Such a split is most obvious in people with mental illness, but it exists more subtly in all of us when we are stressed by bad experiences in the present, or haunted by bad experiences from the past.

I’d love to hear what you think in the comments below, or send me an email.

And if The Splits sounds like your kind of story, it’s available here.

December 1, 2021

Horror film binge

The movie poster for Climax (2019). Don’t drink the Kool-Aid.

My husband has been dragging me down. He’s been ruining my life. When he went away for three weeks to do some kind of nonsense about saving the planet at COP26, dayum I was relieved. Finally… FINALLY … I could get away from the endless Mad Men and Breaking Bad reruns he likes and get down to the real stuff - a sweet 21-day binge on horror films, sometimes two a night.

I kept notes and I’ve got recommendations. Here’s a run down. Apologies if they’re old news to you - I had a lot of catching up to do.

Stone-Cold ClassicsClimax (2019). Sod the lukewarmness of Rotten Tomatoes - this is a thing of beauty. It’s about a group of dancers who meet to rehearse a show and their drinks gets spiked with some mad hallucinogen and it all goes horribly wrong. Beautiful bodies, extremely distressed minds, kind of the opposite of a zombie movie. The journey is truly horrific but also wonderful as long as you can keep a little detachment.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014). Art house movie and incredibly slow - I only watched it because my 12-year old son insisted, thinking it would be fun. How wrong we were. So why am I recommending it? Because those slow, slightly hard-going arthouse movies get under your skin like nothing else. It’s a funny one - it’s set in Iran and yet it’s bones, its characters, are American. It’s in a between world that doesn’t exist anywhere. It’s arguably Twilight on acid. I dreamed about it afterwards.

His House (2020). This is horror at its best - giving story to suffering. It’s about refugees from war torn Sudan making a life in the UK. Who is going to watch some earnest drama about that? Not me. But a horror? A dingy green house with peeling wallpaper in which supernatural horrors ensue? Hell yeah! And while you’re at it, gain greater empathy for refugees and insight into their subjective experience (assuming you aren’t one yourself, I suppose you might be) and become a better global citizen.

ExcellentThe Mortuary Collection (2019). See tweet below.

Watched The Mortuary Collection last night. Beautiful sets, outrageous body horror, amazing performances, hilarity, twists, and an ingenious story about the relationship between horror and conventional morality that will leave you incredibly satisfied. pic.twitter.com/bO4IPIdZRX

— MV Clark (@splitsarchive) November 14, 2021

Girl on the Third Floor (2019) This has an astonishing 22% audience score on Rotten Tomatoes but I agree with the critics, who give it 84%. it’s about a man decorating a new house in preparation for his wife and the baby they are expecting. The house used to be a brothel and is haunted by the ghosts of the prostitutes who worked there. Very interesting to me as my next novel is set in a brothel. The man is played by wrestler CM Punk and he’s a deeply unsympathetic protagonist - a complete dick basically. Yet it’s a fine performance and I felt so much for the character - I was on the edge of my seat throughout about what he stood to lose. Highly recommended.

The Boy Behind the Door (2020) . I think this may actually belong in the stone-cold classic section. It’s about two boys who are abducted and held in a creepy house where awful things are going to happen to them. One of the boys escapes but stays to rescue the other. Lonnie Chavis plays the rescuer and his performance is out of this world. The friendship between the boys contrasted with the threat they are facing made this one those rare films I was utterly gripped by from start to finish. It’s extremely dark and I did think - jeez, what does it take to entertain me these days? At least the darkness is all suggested, never explicit.

The Lighthouse (2019) . Anything about lighthouses always fascinates me. I blame Moominpapa at Sea (a children’s horror novel if ever there was one, to which Annihalation and the Southern Reach owe a great debt - must blog about it some time). This is a wonderful lighthouse narrative. It’s all about the lead actors Willlem Defoe and Robert Pattinson. Defoe plays a seasoned lighthouse keeper and Pattinsoon the rookie. They meet for a lonely three week shift at the eponymous lighthouse and basically gradually go mad. The PR around it was all about the genuinely uneasy and oppositional relationship of Defoe and Pattinson offscreen, and I don’t know how true that is but hell you feel the salty whiplash of their interactions coming out of the screen at you. Delightful (if you are that way inclined).

Relic (2020) . Tells the story of dementia and ageing as only horror can. It’s about a woman looking after her mum, who seems to be losing her mind. Her daughter - also the granddaughter - joins them and she and grandma gang up against Mum in the middle. As someone who is part of a long line of women myself, I found this unbelievably touching. A beautiful film which speaks truthfully of both the darkness and the sweetness of our mortal condition.

Apostle (2018). Probably the weakest of my excellent choices but still pretty wonderful. It’s about a man trying to determine the fate of his sister after she joined a very wierd and horrible cult. Had one scene I had to fast forward through. It was just very gripping.

Honorable mentionsCandyman 2021. Maybe it’s because nothing can top Get Out, possibly the greatest film of all time of any genre. But pretty fantastic.

Drag me to Hell (2009). This has been roaming around in the back of my mind forever and I finally got to watch it. Would have been a wow to the 14-year-old me, but at the age I find myself now it was a little limited. Still, perfect in its way.

The Perfection (2018) . That scene on the bus is so genuinely unsettling and not like anything you’ve seen before. You REALLY don’t know what’s going on. But totally unravels at the end.

PG: Psycho Goreman (2020). Watched this with my 12-year-old son. Pure entertainment, a complete blast, speaks more truly about the reality of the modern family than any serious film i’ve ever seen. The policeman saddened me though, and still haunts me.

I See You (2019). You’re already uneasy because of Helen Hunt’s much-changed facial appearance. That enough would make this film intriguing. But also great twists. Well worth a watch.

The Vigil (2019). Like The Babadook (grief) or His House (the subjective experience of the refugee) or Relic (ageing and death) this movie tells a serious story through the medium of horror. I’ve kind of forgotten the details but I think it is the immensity of a lapsed Jew’s relationship with his historical inheritance. Didn’t break any new ground but very good.

December 12, 2020

Title Fright: The Babadook v Under the Shadow

The Babadook (top) and Under the Shadow - uncannily similar

The Babadook and Under the Shadow are uncannily similar films.

Both are about single mothers – Amelie and Shideh - haunted by a vengeful spirit. But which is better?

I very occasionally do vlogs and blogs comparing two similar horror films.

So let’s find out.

Uncanny similaritiesMotherhoodBoth Amelia in The Babadook and Shideh in Under the Shadow, have given up everything that they used to be at the moment they became mothers. Both are struggling to adapt.

ClaustrophobiaBoth films take place within the home – a strange grey and white house in the Babadook and a 1980s Tehran apartment in Under the Shadow.

JudgementAmelia is judged by her sister, her son Samuel’s school, and social services. Basically that she’s getting things wrong as a mother because her child is so awful.

Shideh is judged by the Islamic regime – for having been politically active in her youth, and for going out of the house in her pyjamas.

Benign older womenBoth Amelia and Shideh gain succour from an older female neighbour. Mrs Roach is a consistent kindly presence in Amelia’s life and Mrs Fakur babysits Shideh’s daughter Dorsa.

Parent-child conflictBoth Amelia and Shideh get increasingly angry with their children as the film goes on, culminating in epic grapples on the floor.

Black gooThe monsters in both films manifests, amongst other things, through black goo.

DifferencesCommunity

Amelia (Essie Davies) - floating around with only the thinnest of ties to other people

In The Babadook Amelia is a typical figure from advanced capitalist society – she’s floating around with only the thinnest ties to other people.

Just one person, Mrs Roach, offers a real connection and she’s quite as disempowered as Amelia as she’s elderly and suffering from Parkinson’s disease.

Whereas in Under the Shadow, the community is really strong.

It has its oddballs and irritants – a strange orphan who moves into the apartment block, like a premonition of the djinn who rides in on magic winds. A gossipy landlady. And a man who complains constantly about the garage door not being closed.

But there is a much greater sense of support – Mrs Fakur looks after Dorsa, and Shideh, as a former medical student, is asked to treat a man suffering a heart attack.

Shideh isolates herself because she refuses to flee the bombing along with the other residents. But the presence of this community is quite distinct from Amelia’s non-community.

I call this round a draw. Community is an axis that reveals interesting differences in the two films, but clearly one is not better than the other, and both films portray these worlds equally well.

Parent-child relationshipDorsa is a lovely little girl and the fear we have in relation to her is that she will be hurt or killed. What complicates Shideh’s relationship with Dorsa is the state repression ruining Shideh’s career, and the bombs destroying their home.

Samuel evokes a different fear – that he’s one of those ‘difficult children’ with whom nothing can be done.

But there’s so much packed into The Babadook. It certainly peers into the abyss of Samuel being irredeemable. But by the end we realise his personality is much more dynamic – a co-created outcome of his relationship with his mother, and their shared trauma.

The dark heart of The Babadook is that Amelia doesn’t love Samuel – all she can say when he says ‘I love you mum’ is ‘me too’. When you think about the film in this light, Samuel’s behaviour is much more understandable.

Some critics see Samuel as an envoy of patriarchal oppression. But I don’t buy this. Motherly love isn’t just a submission to the patriarchy – that’s part of it… but reducing it to only that is facile.

When you’re faced with your own child, an actual small human being, their need for love is not something you can shrug off with identity politics.

Still, it’s not easy.

The Babadook gets all of this across.

I suspect that for people who have experienced war Shideh and Dorsa may be more compelling – the way they are haunted by the violence around them is unforgettable. And I’ll talk more about this distinction in the next round.

But if we are looking purely at the parent-child relationship, I think The Babadook has to win because of its sheer complexity. There are so many twists and turns to Samuel and Amelia’s relationship, all of them gripping, illuminating and essential.

The Babadook portrays a parent-child dyad struggling to be born and it is unbelievably moving.

Subjective vs systemic violenceYes, it’s time for the Z word! No, not zombies, Zizek!

In his book Violence, philosopher Slavoj Zizek drew a distinction between subjective and systemic violence.

Subjective violence singles particular people out for violence because of who or what they are, while treating others well. It chooses you specifically.

Systemic violence occurs in a violent system. Victims are simply in the wrong place at the wrong time, and it could have been anyone.

I thought of this when I compared The Babadook and Under the Shadow.

In war, your problems are not of your own making – there’s an external enemy. Shideh’s torment is because Iraq is bombing her and Iranian Mullahs are repressing her. She’s in the wrong place at the wrong time.

She does some very odd things - refusing to leave Tehran during a period of intensive bombing, and dancing in silence to an imaginary Jane Fonda tape. But under the circumstances this is totally relatable.

Amelia’s problems all stem from her. The death of her husband may have been bad luck, but how she’s dealt with it is not. Samuel’s dysfunction is her subjective failure, it’s happened because of who and what she is, a bad mom and possibly a bad person. Like Samuel, perhaps she’s irredeemable.

To me this is much more chilling, but that reflects the fact that I experience life more like Amelia than Shideh, because I live in a safe Western country. If I fuck my life up, I know it’s my fault.

However, I know without asking that anyone who lives in a war zone would consider it the ultimate luxury to be able to say, ‘I fucked my own life up’.

Another way of looking at this is from a psychoanalytic perspective. Therapists often say that what messes up the lives of their patients is that they can’t see the truth. This could certainly be applied to Amelia, as she faces up to the fact that she’s still broken by her husband’s death, and that it’s destroying the future for her and Samuel.

But for Shideh, the truth is abundantly clear, and that still doesn’t mean freedom.

Watching Under the Shadow for the second time, I was struck by how many scenes there are of female oppression at the hands of the Islamic republic. Shideh is basically a prisoner in her own country. She can do nothing to give her daughter the life she deserves, and she knows it.

On earlier viewings it had been the war that impressed me most as the metaphorical shadow over Shideh and Dorsa. It took an even deeper immersion to confront the fact that the shadow is also the systemic bullying of women.

Notably, Under the Shadow ends with Shideh and Dorsa fleeing their home which remains occupied by the untamed djinn. There’s no resolution for them.

Amelia and Samuel, on the other hand, achieve a precarious but profound co-existence with the Babadook.

I call this round a draw. The Babadook confronts us with the internal, subjective agonies of mothering. But Under the Shadow opens our minds to the terrible hopelessness of mothering within a violent system.

ConclusionThe Babadook wins two of the three categories and Under the Shadow wins one. So it’s a win on points for The Babadook.

But that’s just my opinion and I know I’ve arrived at it because I recognize myself more in Amelia than in Shideh.

Under the Shadow remains incredibly powerful and one of my all-time favourite horror films.

I’d really love to hear what anyone else thinks, so if you’ve read this far please do comment below.

May 22, 2020

Title Fright : Train to Busan v 28 Weeks later

Hello and welcome to Title Fright!

Title Fright used to be a vlog but I’m really bad on screen so it’s a blog now, and much better for it.

The concept is that two similar horror movies will fight, like boxers, to see which is the best.

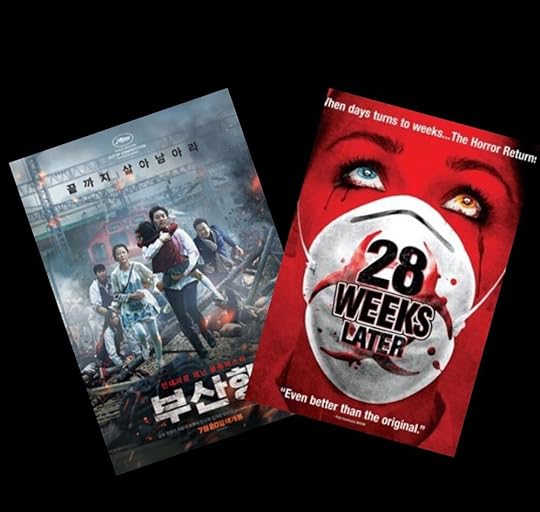

Today I’m pitting two critically-acclaimed 21st century zombie films against each other - Train to Busan and 28 Weeks Later.

28 Weeks Later was released in 2007. It stars Robert Carlyle as Don, the head of a family that’s been fractured by the Rage virus that is devastating the UK. Imogen Poots plays his daughter Tammy, and Mackintosh Muggleton plays his son Andy.

Train to Busan is a 2016 South Korean film. It stars Gong Yoo as fund manager and distracted father Seok-Woo. Kim Soo-Ahn plays his daughter Soo-An. She persuades him to take her on a fast train to Busan to see her mother, but on the way the train is attacked by zombies.

The question is this: which one would beat the other in a fight? In…er… my opinion.

The weigh inLet’s look at each film to establish if they’re a good match.

I initially intended to pair Train to Busan with La Horde – a French zombie film where the battle takes place in a tower block - because both are action-horrors where the action is shaped by particular physical structures. But after watching Train to Busan I changed my mind.

Despite it’s kinetic energy, La Horde’s characters are shallow and unlikeable. They also fail to learn – notoriously, they keep shooting zombies in the chest.

Whereas Train to Busan is crammed with simple but compelling characters whose interactions keep us emotionally invested and drive the plot forwards.

It just wouldn’t be a fair fight.

28 Weeks Later was the obvious replacement, despite it’s wider canvas. Like Train to Busan, it’s a critically acclaimed zombie flick full of astute social commentary, with a flawed father as the central character.

Parallel 1 - FamilyBoth films place family at the heart. For the first fifteen minutes of Train you could easily think you were in a touching family drama if you didn’t know better. It’s not just Seok-Woo and Seo-An - a couple expecting a baby also become integral to the action.

In 28 Weeks the family is broken up, reconstituted, then broken up again, and this is what propels the story forward.

Neither film relies on zombies to rivet your attention.

Parallel 2 - FathersIn Train, Seok-Woo is a callous fund manager. It’s obvious he vaues money over family, and he has a terrible relationship with both his daughter and his ex-wife.

In 28 Weeks, Don is a loving father but he’s not a hero. He deserts his wife during a zombie attack, and lies about it to his children. As I watch I always long for him to be a reassuring father figure, but he never quite makes it.

Both Don and Seok-Woo end up infected, like some kind of bad-dad karma.

Parallel 3 - LeadershipBoth films take a long hard look at leadership. In Train, Yong-Suk, a businessman, is singlemindedly devoted to his own survival. He’s quite happy to sacrifice others to this end. Seok-Woo takes the same approach initially. Whereas a tramp and a blue collar worker show much greater solidarity with their fellow humans. There’s a sense that only ordinary people can lead in a situation like this – powerful men are the last people you should trust.

In 28 Weeks, the military command is quick to move to a policy of extermination of all civilians, infected or not. Only a soldier on the frontline has an unshakeable urge to protect. He’s looking at each person through his gun sights and he sees them as individuals.

Let the fright beginThis is the part where we look at what divides the two films, and what makes one better than the other. I suspect this is going to be a very close, somewhat bloody fight. I really cannot tell you which film is going to win.

Round 1 - The fatherTo begin with, high flying finance executive Seok-Woo is a textbook terrible father. He has his secretary buy a gift for his daughter and it turns out to be the same gift she got last time. He doesn’t turn up to her school shows. It’s her birthday the next day and unsurprisingly she she wants to spend it with her mother. With great irritation he agrees to take her, and that’s how they end up on the train to Busan.

When the zombies arrive on the train Seok-Woo’s first reaction is to shut them out – along with an uninfected couple Sung-Gyeung and Sang Hwa. It’s even worse because Sung Gyeung is pregnant. Soo-An is horrified and comments on her father’s ruthlessness.

But when Sang-Hwa saves Soo-An’s life, Seok-Woo begins to reassess.

By the end of the film he’s completely changed his moral code. When he’s infected he throws himself off the train to save not just his daughter’s life but that of Sung-Gyeong, the pregnant woman.

Whereas Don in 28 Weeks Later is something much more curious. He loves his wife and children but he’s not a hero and he’s possibly a coward.

I’m torn on how to interpret Don. Is he as a realistic depiction of how some people will react at times of crisis, and all the more chilling for it? Or does he represent the debased state of British leadership in the world? A lingering shot of Lord Nelson on his column drives home this parallel.

After he gets infected, he becomes a murderous father. He seems to single out his children – after witnessing a heroic act by his son he follows him and attacks him.

This couldn’t be further away from Train to Busan.

It’s hard to choose a winner here on the question of fathers. Don is messy and horrifying and ambiguous, while Seok-Woo is a crystalline portrait of redemption. But ultimately both are equally powerful.

This round is a draw.

Round 2 - LeadershipThere’s a wider question in both films about how we lead society and civilisation in a time of threat.

In Train to Busan, Seok-Woo’s ruthless moral code is explicitly linked to his position in society. When he tells another character he’s a fund manager, he’s told he’s a leech.

Businessman Yong-Suk is even worse and remains committed to his ‘I’m alright Jack’ mentality until his death. The staff on the train cravenly follow his lead.

Apparently this is a comment on an incident where a Korean ferry was overloaded to increase profits. It overturned and 300 people died. The crew escaped on lifeboats but did not try to help passengers.

In 28 Weeks Later leadership is provided by the US, who have created a safe zone where Don and his children are reunited. When the rage virus breaks out inside the safe zone, the US command orders the implementation of Code Red, which means killing everyone regardless of whether or not they are infected.

Many commentators have suggested this is a comment on Iraq, and the bombing of civilians whether or not they are terrorists. If so, the character of Don who takes a job in the safe zone works nicely as a figure of British cronyism during that episode.

Again, both splendid and powerful comments on leadership. Another draw.

Round 3 - Father-turned-zombieI want to zoom in on the transformation of the father into a zombie, which is treated in a very interesting way in both these films.

Often in zombie movies, one infected will be singled out for special treatment. Instead of turning and becoming a mindless, weaponised human body, they will linger in a half-and-half world, where they still seem to have some sense of what was important to them when they were living.

These are the most powerful and revelatory moments in zombie films for me. These characters are a kind of ‘zombie plus’ as far as I’m concerned. They embody the meaning of the film in a concentrated form that as a horror fan I find intoxicating.

This moment comes with Don in 28 Weeks Later when he’s succumbing to the rage virus in a room with his wife. He knows what’s happening and he’s trying to resist but it’s hopeless. That’s the peak for me.

But it doesn’t end there. Don carries on being ‘not just a zombie’. When he comes face to face with Andy, he’s able to pause before he attacks. When Andy bravely runs out in front of a sniper to distract his attention and draw his fire, we see Don lurking in the background. Don does not attack, he merely exudes malevolence. A moment later he disappears, making him more like a ghost than a zombie.

When the final confrontation between Don and his children takes place in a deserted London underground station, it doesn’t feel like coincidence. It feels as if he’s been targeting them. It feels as if he always wanted to kill them, and the infection has freed him to do so.

It’s a very dark commentary on fatherhood.

Train to Busan has exactly the same rich transitional moment when the moment of infection is slowed down, yet the drama of it is hugely intensified.

Seok-Woo is bitten trying to protect Soo-An from the infected Yong-Suk. He succeeds in throwing Yong-Suk from the train and then has about a minute to spend with his daughter before he turns. He shows her how to stop the train and that he loves her. He’s successfully protected her throughout the film but now she’s on her own.

Seok-Woo stumbles to the back of the train and as the infection takes over there is a dream sequence in which he’s back at home with Soo-An and they are having the perfect father-daughter relationship.

Soo-Ann has lost her father, but she has also gained something - faith that he is a good man. This gives her the strength to sing as she approaches the soldiers in Busan, saving herself and pregnant Sung-Gyeung. Here we see a much brighter depiction of fatherhood. A grapple with the darkness – in the form of a zombie epidemic - becomes transformative and renewing. Quite a contrast with 28 Weeks Later, but I love this kind of optimism in horror when it’s done well.

Again very different, but equal. Another draw!

Round 4 - StructureTrain to Busan is two hours long but it flies by because it’s perfectly structured. It builds and builds and builds. The emotional climax - where the father is infected with the zombie virus but purged of his moral corruption – is perfectly timed at the end. As such, it’s a a beautiful film.

28 Weeks Later is actually shorter but feels longer. This is because the emotional climax comes in the middle, when Don kisses his wife, gets infected and then kills her. Shortly after he confronts his son Andy, in one of the most exhilarating ‘bad Dad’ scenes in the whole of horror history.

After that the story has nowhere to go. Perhaps the scene late in the film where Tammy kills Don as he’s attacking Andy has the potential to satisfy, but it doesn’t.

Ah - some kind of result at last. I call this round for Train to Busan.

Result – A win on pointsIt’s very, very close. There’s no knock-out blow here. But Train to Busan wins on points. Although both films are equally powerful, the lighter and more optimistic Train to Busan has a far better structure.

Thanks for reading. This is obviously totally subjective so please, please tell me what YOU think in the comments below.

March 29, 2020

Coronavirus - will we see a better world?

Coronavirus: can we hold on to our humanity in the face of so many dangerous bodies?

The number of people worldwide who have contracted coronavirus has risen to 600,000. The number of people contacting me to say my novel, The Splits, reminds them of real life has risen equally sharply, from zero over three years to eight in a fortnight.

“What do you think about the psychological impact?” said one reader. “I think there are already a few parallels with your book.”

“Your book feels prescient now the panic has settled in!” said another, based in London, the UK epicentre of the virus.

“Your book stayed with me anyway,” added a third. “Now I’m thinking about it all the time.”

The Splits is a zombie pandemic novel, and it would be ridiculous to compare COVID-19 to anything to do with zombies … were it not that my novel is an outlier within the genre. When I think about it, I’m truly surprised that my novel got so much right. And a little bit alarmed - but more of that later.

Unlike most zombie fiction, the infection I dreamed up is brought under control. The things that happen while it is ongoing are highly reminiscent of coronovirus - empty streets, food shortages, having to stay indoors, and the threat of martial law. But it’s all over by the end of the first chapter. The pandemic is not the end of the world, society does not disintegrate, there is no apocalypse. Once cases are brought down to an acceptable level, everything goes back to normal.

The same will happen with coronavirus, eventually.

However, the story of The Splits does not finish with the first chapter. The impact continues to be experienced and debated in my character’s homes and hearts. But here, too, there are parallels with coronavirus.

My characters want to understand the Splits, just as we are trying to understand Covid-19.

They want to be sure who has it and who doesn’t, but that turns out to be more complicated than ‘look - a zombie!’. It is the same with coronavirus - coughing might mean you have it, or it might not.

My characters are desperate for a cure, just as we are for coronavirus. There is a spectrum of vulnerability to the Splits - some people get the full blown disease while others have a asymptomatic but still infectious variety - just as with coronavirus.

My characters see the government get the disease under control in the short term, but they do not see it make the big changes needed to ensure long-term survival. This is similar to how real governments have behaved as Covid-19 spreads, and questions are already being asked about what will change in the aftermath.

The thing that alarms me is this. There is an added twist to my zombies, which is that they have ghosts. These ghosts are complete selves (whatever the human self is - soul, quantum computer, biological accident - your guess is as good as mine).

That means my infected are not just dangerous bodies - not just weaponised corpses like the zombies in World War Z - which you can shoot down without compunction. There is a treatment. It’s controversial, it’s unpredictable, it’s slow and it requires a massive change in mindset akin to the discovery that bacteria causes disease in the 18th century. But governments judge this cure unrealistic and unaffordable. So governments continue to shoot the infected.

This, to my mind, echoes the debate about whether or not to sacrifice the economy to save lives during the coronavirus pandemic. The UK government’s ‘herd immunity’ strategy basically meant letting people who are vulnerable to coronavirus die because it’s too expensive to keep them alive. In 2017, the UK government literally did not buy protective gear for NHS staff because it cost too much.

In The Splits human society doesn’t rise to the occasion. There’s no root and branch transformation, (although there might be later in The Splits Archive series). I hope this will not be the case after coronavirus. I hope we see real change.

Stay safe and well and full of hope, all of you.

Readers are telling me my book is like coronavirus

Coronavirus: can we hold on to our humanity in the face of so many dangerous bodies?

The number of people worldwide who have contracted coronavirus has risen to 600,000. The number of people contacting me to say my novel, The Splits, reminds them of real life has risen equally sharply, from zero over three years to eight in a fortnight.

“What do you think about the psychological impact?” said one reader. “I think there are already a few parallels with your book.”

“Your book feels prescient now the panic has settled in!” said another, based in London, the UK epicentre of the virus.

“Your book stayed with me anyway,” added a third. “Now I’m thinking about it all the time.”

The Splits is a zombie pandemic novel, and it would be ridiculous to compare COVID-19 to anything to do with zombies … were it not that my novel is an outlier within the genre. When I think about it, I’m truly surprised that my silly little novel got so much right.

Unlike most zombie fiction, the infection I dreamed up is brought under control. The things that happen while it is ongoing are highly reminiscent of coronovirus - empty streets, food shortages, having to stay indoors, and the threat of martial law. But it’s all over by the end of the first chapter. The pandemic is not the end of the world, society does not disintegrate, there is no apocalypse. Once cases are brought down to an acceptable level, everything goes back to normal.

The same will happen with coronavirus, eventually.

However, the story of The Splits does not finish with the first chapter. The impact continues to be experienced and debated in my character’s homes and hearts. But here, too, there are parallels with coronavirus.

My characters want to understand the Splits, just as we are trying to understand Covid-19.

They want to be sure who has it and who doesn’t, but that turns out to be more complicated than ‘look - a zombie!’. It is the same with coronavirus - coughing might mean you have it, or it might not.

My characters are desperate for a cure, just as we are for coronavirus. There is a spectrum of vulnerability to the Splits - some people get the full blown disease while others have a asymptomatic but still infectious variety - just as with coronavirus.

My characters see the government get the disease under control in the short term, but they do not see it make the big changes needed to ensure long term survival. This is similar to what we have seen with Covid-19, although the long term consequences remains to be seen.

There is an added twist to my zombies, which is that they have ghosts. That means they are not just dangerous bodies - weaponised corpses as Max Brooks puts it - which you can shoot down without compunction. Yet society in my book cannot afford the treatment which has been shown to work to heal people infected with the Splits, so governments continue to shoot them.

This, to my mind, echoes the debate about whether or not to sacrifice the economy to save lives during the coronavirus pandemic. The UK government’s ‘herd immunity’ strategy basically meant letting people who are vulnerable to coronavirus die because it’s too expensive to keep them alive.

In The Splits human society doesn’t rise to the occasion. There’s no root and branch transformation, (although there might be later in The Splits Archive series). I hope this will not be the case after coronavirus. I hope we see real change.

Stay safe and well and full of hope, all of you.

March 12, 2020

Guts Reaction - The Outsider

Ben Mendelsohn plays bereaved father and detective Ralph Anderson

Horror is stuffed with conventions and boy do those conventions get boring. A shape-shifting monster, a pursuit, a showdown – blah blah blah. That is the basic arc of The Outsider and on paper it sends me to sleep.

But when you watch the show you have complex characters played by superb actors. Ralph Anderson, the detective who has lost his son and is investigating a child murder, is played by Ben Mendelsohn, who I love for the way there is always a child peeping through his performances, one who seems to reach needily out of the screen to the viewer.

Paddy Considine crackles, once you realise he is not going to play dull Claude for the whole show. In fact, the character of dull Claude is a deliberate choice to explore the meaning of the supernatural premise.

The tortured Jack Hoskins (Marc Menchacha) is made three dimensional with a few deft strokes. At the start he’s secure, with a well-honed hail-fellow-well-met persona that allows him to relate warmly to people despite his childhood wounds. By the end his way of coping has been torn apart and he’s stripped down to just his pain.

The supernatural element is treated intelligently. It’s not expected to excite viewers merely by virtue of being supernatural. It’s presented in a strangely matter of a fact way, and the show does not dictate to anyone - either characters or audience - whether or not to believe. When the monster is vanquished there’s no celebration of a return to normality. There’s merely a dour agreement that the experience is taboo, it must be buried. Nobody who wasn’t part of it would have the will or the ability to understand

Yet ‘El Cuco’, as the monster comes to be known, neatly represents real terrors – cruelty, bestiality, the destruction of certainties. These certainties may be essential and protective as in the case of Glory Maitland, who has lost her husband and her sense of safety in the world. Or they may be unhelpful certainties, as in the clinging of sceptical Ralph Anderson to his dead son. By the end of the show he admits his world has been ‘cracked open’. He believes in the shape-shifting monster and he feels paradoxically closer to his lost boy.

Ultimately I felt the best analogy for El Cuco was death. Unspeakable, unfathomable, and once it’s as if nothing ever happened, as if the person was never there. There’s nothing to do but get on with your life.

I don’t actually believe in the supernatural, but I believe in what it stood for in this show – death’s implacability, it’s intransigence, it’s victory over us.

February 11, 2020

Guts Reaction – The Joker

The Joker is a dark star of provocation and I liked it a lot. It’s about as fun as confrontational, in your face, ‘problematic’ cinema can be.

First, the cons. It needs to be said that very few mentally ill people hurt anyone. Nor is the Joker as original as it’s thought to be - Carrie, Monster (about Aileen Wuornos) and of course Taxi Driver all tread similar ground. Finally, the protagonist’s metamorphosis – momentarily at least - into a triumphant supervillain feels like a direct invitation to copycats. How more unambiguously glamorizing can you get?

But The Joker poses its difficult questions brilliantly. Does it encourage vengeful violence, we are left wondering, or greater compassion? Does it humour dangerous individuals, or expose society’s responsibility for their behaviour? Does it vindicate murderous narcissism, or power up the downtrodden? It’s never clear, making it a genuinely troubling watch.

Arthur Fleck himself is hard to decipher. His mental illness is not the romantic type, it’s difficult and distressing. But his violent offending is relatively sympathetic - he’s not obviously sexually deviant and he only kills really unpleasant people. He’s delusional, infantile and out of control, but he’s not psychopathic, calculating or sadistic. He’s not Ted Bundy.

I found myself rooting for him, and felt duly uncomfortable. But we are all the heroes of our own stories and if you want to understand people that’s where you have to go.

What is more, it’s possible to go much further than The Joker ever does. American Psycho, for example, succeeds in making serial killer Patrick Bateman sympathetic. Bateman is psychopathic, calculating and sadistic, however most of us rationalise this as brilliant satire. This isn’t possible with the The Joker and not just because of its sober tone. It may be set in the mythical city of Gotham, but because Arthur Fleck is less extreme he’s also far more real.

There is no escaping what the film asks of us – to combine bitterly incompatible polarities into a single, uneasy whole. The vulnerability of violent offenders versus the threat they pose. Our safety as the law-abiding majority versus the harm we inflict on the less fortunate. The rewards of communicating with dangerous people versus the imperative to stop the danger.

Not everybody will see Arthur Fleck as vulnerable because not everybody has the luxury. Some of us have experienced nastier versions of him. But for those of us that can, watching him caper down the stone steps is, I think, mind-expandingly disquieting – the moment the film unifies its contradictions.

“Society should condemn a little more and understand a little less,” John Major said in the 90s during a clampdown on crime. This is certainly simpler, and in the short term it may be more effective. But The Joker reminds us it will only create more monsters.

5/5

February 8, 2020

Mentalisation - a boring name for a beautiful idea

What would it be like if you couldn’t understand the minds of others? Would it be like being locked in a dark room? Would it feel as if the things you needed – food, affection, peace and quiet, stimulation – came out of nowhere, if at all? Would it be as if there were monsters in the darkness?

Professor Peter Fonagy

This was the picture I had in my head after listening to Peter Fonagy on Radio 4’s The Life Scientific. He is one of the psychoanalysts behind mentalisation-based therapy (MBT), which focuses on the need to understand minds – our own and other people’s – to have good mental health.

To ‘mentalise’, you must be able to stand back from your own thoughts and feelings rather than simply experiencing them, and from the thoughts and feelings of others rather than simply reacting. This provides a “protective buffer” that cushions you from emotional pain. Without that buffer, says Dr Fonagy, many people lose control and become victims.

Dr Fonagy’s ideas are deeply rooted in attachment theory. This is the idea that people’s adult behaviour is affected by the care they receive in the first months and years of life.

If the ‘attachment’ is healthy and consistent, the child learns to trust others to understand him or her, and grows up able to understand others. But when the adult is abusive, the child learns not to expect understanding. He or she learns not to be curious about what others are thinking and feeling. In the devastating words of Dr Fonagy, if you had been abused would you want to understand your abuser’s thoughts?

Declaration – I have business with mentalisation theory. My father read up on it in an effort to understand difficult people (interestingly, for a few months after this was fresh in his mind, he became the most empathic and intuitive I have ever known him). I borrowed his books and fell in love with mentalisation.

I love it for the way it isolates the psychic violence that underlies all more tangible forms of violence. I love it for the way that it explains so much – why someone who is clearly sensitive can be aloof and unkind, why trying to resolve a falling out with certain folk just makes it worse, and why the people in your life who are most hurtful to others are themselves deeply hurt by relatively small things.

Currently I am most excited at the idea that mentalisation – or a difficulty with mentalising - is not one thing, it’s many. It makes some people into aggressors, but it makes others into victims. It‘s been linked to genocide in a masterful book, The Killing Compartments by Abram de Swaan. But it’s also been identified as a defence mechanism for coping with trauma. It can, in fact, indicate someone who is kinder and more sensitive than they can handle, and who has suffered great pain.

Some opponents of mentalisation feel that it is reductive, but I think it is merely simple. It insists, like the rest of psychoanalysis, that we expand beyond concrete, linear concepts of reality and embrace the dynamics of mind - a complex, unpredictable field of possibilities that defies ordinary logic.

Mentalisation is also is one of the themes of my book, The Splits. What is it like when we live in a world where minds are denied? What is left of people who cannot navigate the world of interacting psyches? Could they act like zombies, or be mistaken for zombies, when in fact what is going on is much more interesting?

The hardest passage I had to write was about a character, Michael, who seem to have a borderline condition of some kind with aspects of moral madness (I use these old fashioned terms because I’m not an expert, and because he doesn’t conform to any modern psychiatric diagnoses). It was one of the greatest challenges I have ever faced as a writer, to put myself in the mind of someone so destructive and understand their pain. I’m still not sure I did it justice.

But when I hear Dr Fonagy say that it is how we treat each other as a community that determines mental health I feel I did something good by making the effort. If you really want to know what I think it’s this: mentalisation should be taught in schools. In the meantime, maybe someone can read my book and think a little more carefully about that ridiculously vulnerable person they know who is always getting in a state about the slightest thing, or that wildly overemotional, unreasonable person who causes so much pain.

February 6, 2020

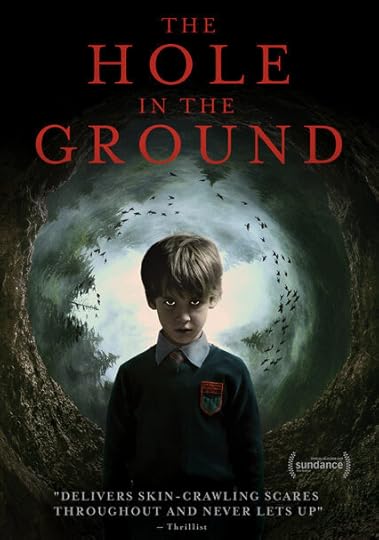

Guts Reaction - The Hole in the Ground

As a fan of The Babadook and Under the Shadow, I’ve always got room for another exploration of mother-child relationships through horror, so I enjoyed The Hole in the Ground.

Sarah and her son Chris move to a remote house in the countryside. They encounter a deranged old woman who apparently killed her son because she thought he was an imposter. After encountering a sinkhole in a pinewood, Sarah begins to suspect the same of Chris.

In The Babadook the engine of horror was complex grief. In Under the Shadow it was political repression and armed conflict. The Hole in the Ground never spells out what the trauma is, but I got the impression Sarah and Chris had suffered domestic violence at the hands of Chris’s father.

I felt the film could have dug into that much more deeply. Physical abuse within the family opens up its own deep well of questions. But the film seemed content to stay at a generic level. For example, the damage to Sarah and Chris’s relationship seems to come about purely as a result of the supernatural twist. Whereas with Amelia and Samuel in The Babadook, it is well established before, and apart from, the appearance of the eponymous monster.

However, The Hole in the Ground is rescued from mediocrity by the filmmaking. It is perfectly paced, and there are certain sequences that are just brilliant. The soft, muffled atmosphere of the pinewood where Sarah first discovers the strange, collapsing hole, for example. And the scenes where Sarah begins to suspect Chris is not her son are exquisitely uneasy. I wished there had been more of them, and that greater risks had been taken.

All in all, 4/5 stars and well worth a watch.