Manish Gaekwad's Blog

April 15, 2025

POEM

It just so happens

That at bedtime

I am fortunate to see

Mangled human bodies

Some held altogether

Like rationed salt in a plastic bag

Others collected

In memory’s coin slots

I hastily skip them all

On my timeline

I am fortunate to be

Disoriented for a split second

Switching before I blink

To reels of cute canine

And feline friends

Chomping Wagyu beef

And lapping Dog Pérignon

My algo colludes with Palestine

But I am fortunate

To be numbed

By the video game simulation of violence

Watching ain’t playing y’all

I am fortunate to sleep unperturbed

A state of temporary death

I wake up from, reset

To be cuddled by forgetfulness

I am fortunate to not

Think, feel, act

In a gluttonous world that is

Indigestible night & day

I am fortunate to tread

Into my invisible self

Do not go gentle into that good night

Said one Dylan, not Bob

Hell ya!

The mangled bodies are

Returning to shape

The undead scream alive

To curdle my blood

To shake my inviolable

Fortunate soul[image error]

March 25, 2025

Sameer, the pedestrian poet

Quite aptly, his lyrics such as Tujhko mirchi lagi toh main kya karoon have no English equivalent.

Sameer

SameerLyricist Sameer has always prided himself as a pedestrian poet.

Consider this: Main toh raste se jaa raha tha/Main toh bhelpuri kha raha tha/Main toh ladki ghumaa raha tha

Raste se jaa raha tha

Bhelpuri kha raha tha

Ladki ghuma raha tha

So far so-so. The words are in metre.

He then introduces the fourth line of the stanza: Tujhko mirchi lagi toh main kya karoon.

No rhyme. No rhythm. Is it anti-metre? Is it a punch line? Is this a joke?

The addictively catchy tune gets cheekier in another invectice line: Teri nani mari toh main kya karoon!

Bloody rascal behaviour. The unfunny line provokes you to consider a chuckle in repose.

Indubitably, he must be ranked with the greats, even if lower in order of distinction, but comparable to Javed Akhtar whose refusal to write lyrics for a titillatingly titled film Kuch Kuch Hota Hai led to Sameer writing in maudlin resignation: Kya karoon haaye, kuch kuch hota hai.

In a recent Lallantop appearance, the interviewer eloquently introduces Sameer with a line from his lyrics in the song Dulhe Ka Sehra Suhana Lagta Hai.

The line is Main teri baahon ke jhule mein pali babul.

The interviewer says this line alone can melt even the coldest of hearts.

Sameer recalls the incident when the singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan teared up at this very line for over an hour in the recording room, reminded of his own daughter Nida.

With each new take, as he reached the line, he’d choke and weep.

Main teri baahon ke jhule mein pali babul.

An emotional Khan saab was persuaded to stop but he stubbornly completed the qawwali.

He said: If I can’t do it today, I’ll never complete it.

Khan sings the first line of the antara in lai with the second line of the antara Ja rahi hoon chhod ke teri gully babul.

He feels a jolt.

Unsatisfied with the melody, he then repeats the first line Main teri baahon ke jhule mein pali babul a second time with a taan, then scales octave in the third attempt and finally returns to the metre and scale in the fourth repetition of the same line.

It’s a record-smashing vocal quadrathlon.

He did not have to sing the line four times but the qawwali nurtures improvisation. Khan saab got carried away, perhaps foreseeing his daughter’s hand in marriage.

Khan had been ill for some time. He knew he would not be around for her wedding. He died in 1997, soon after the song recording. Nida was in her teens. In 2000, the song was featured in the film Dhadkan.

Sameer’s conversational poetry is his legacy. Khan sang those words like a plea, hoping it would make it to Nida’s special day. Nida remains unmarried, missing her father’s presence for her bidaai.

Main teri baahon ke jhule mein pali babul.

https://medium.com/media/44fe38abe89c9fcbe78332008d6ac8b3/href[image error]March 9, 2025

I Don’t Want To Talk About My Mom

She’s been dead for two years, but she’s going to be alive for much longer

Still from the movie Pakeezah

Still from the movie PakeezahAn edited version of this story appeared in The Tribune.

I am embarrassed to talk about my mother. Let me delineate that milquetoast statement with a pop culture reference to make this more, for the lack of a profound synonym, relatable.

Remember, like it was yesterday, when Karan Johar inexorably fixated on Alia Bhatt this, Alia Bhatt that, Alia Bhatt every two words I spout. The diminutive, baby-faced mascot of cute emojis had to sit the pouty gentleman down, and I will paraphrase his obsessive condition here, she said: You are not my mother! STFU.

Freud has said: If it’s not one thing, it’s your mother.

You will empathise if you find yourself overselling your mother outside the kitchen. Wait a minute, isn’t that what you do? My mother is the best cook in the world! As if she has no other function.

My mother has. Cooking, cleaning and ghar-sansar; she’s been much more than that.

I was recently re-watching Govinda’s old interview on the talk show Rendezvous With Simi Garewal. He answers every question with Meri maa kaha karti thi. His devotion to his mother is sweet, but after a few mentions it begins to sound mawkish, considering he’s sitting on the bench with his spunky and hilarious wife Sunita Ahuja, who lets his wallow. She has a thick hide. Govinda’s mother Nirmala Devi was an exceptional classical singer. He mentions that only in passing and keeps referring to her platitudes pertaining to his career, upbringing and lifestyle. He reveres her but only as his mother. The lady’s life before him is glossed. My guess is the stigma attached to a female performer in the fifties, nearly overlapping with a tawaif’s profession, being harshly judged by society’s standards for a woman working to raise her children when the husband falls on bad times. This can lead to her child growing up to paint her as a saint of aphorisms. Meri maa kaha karti thi is not where I want to be wistfully hanging up side down — an old vibes tale.

Ever since I wrote my mother’s memoir, on her life as a tawaif before and after me, the title of which I find too long to type and refer in its abbreviated form as TLC (acronym for tender loving care), I have been talking nonstop about her. I wish to wash my hands off her. As timelines refresh, I look forward to when I do not have to mention her name, except when I am paid to reflect like this gig. My ears may voluntarily turn deaf any moment now hearing my own nasal voice howl a thumri about her khooobsurti, hunar, adab, shokhi, adaa, saadgi and her unparalled akal-mandi arriving by the accidental criss-crossing of her gardish ke sitare.

My mother has been dead two years. Grieving isn’t a daily ritual like a prayer when prayer itself isn’t a habit I wear like an undershirt. I want to move on to the next story. I want to tell my own story. It may not be as raw, brave, courageous (same as brave), poignant and inspiring as hers, as reviewed and reported in the media. That has made me jealous, unapproving of her posthumous glory. She’s toast. In sync with the vainglorious times we inhabit, let’s move on to the next chapter: Me, me, me.

My mother had a rough, tumultuous life, and thereof she then had the smarts to make my life velvety and painless. Even privileged I would say. Not entitled, which is debatably a bulwark of lineage, but privilege, sure, in my case elite boarding school education, a sheltered childhood and a healthy dose of pep talk. Bade naazo se paala hai tujhe maine, she said, kisi baat ki kami nahi honay di hai. You can almost hear a taraqqii-pasand sher, a ghazal, a melody in her tender voice. Yes, I know, I should not be making fun of her. But here’s the thing: she would dil khol ke welcome it. Part of surviving with grit is the ability to make light of it. Humour alleviates suffering. She balanced it stupendously.

I don’t get to complain about having a hard life. Nonpareil to hers, mine’s a moonwalk eclipsed by her strife. She had improved me in her mould. I unctuously resent her for it. She gets all the smoky, sultry, messy, masaledar seventies disco and bang-bang drama. Mine is lyrically nineties post-existential art house as watching a red balloon float into the blue, blooming sky. After a few minutes, one gets bored of staring at something so dull and uneventful. What else is a balloon’s fate other than fading into the white sun? I ask myself if that’s all I have to do for the rest of my life, hover in the shadow of my mother’s brilliant, meteoric rise in death.

In the dark comedy film Throw Momma From The Train, every time Danny DeVito, a wannabe writer sits at his typewriter to punch a story, his irascible old mother interrupts him with an errand that makes him lose his train of thought. He struggles with his weird imagination to poison her Pepsi, impale her with a surgical scissor, make her trip down a basement staircase or by blowing a trumpet into her ear. I wish for a similar confrontation. I imagine my dear and positively departed mother punching my Adam’s apple and saying: Bas, chup kar, mujhe bolne de. Let her nautch ghost dance. Touché.

Actually, talking about her did not come naturally to me. The first time I was on stage at a literature festival to talk about my mother shortly after the release of her memoir, I was convinced that the glare of the strong light focused on us was partially blinding me. Nervous energy was clouding the other half. I was shaking like a leaf, my co-panellist, human rights activist Naseema Khatoon informed me later. She was raised in a brothel. She spoke eloquently, formidably about her mother. What she said allayed my fears of speaking on stage, interacting with a crowd, facing a spotlight; things I zealously avoid as I consider my work done in the written word.

She said: Hum andheron se nikalkar ab roshni mein hain, aur jo log ab tak roshni mein thay woh ab andhere mein hamey sunn rahe hain.

We emerge from the darkness into light, and those who were in the light now heed us in the dark.

Her encouraging words lit my tail. From then on it became todo sobre mi madre. I am able to re-direct the focus light on to my mother. When words fail me, I say: Just read the damn book!

I am, however, unequivocally abstemious of well-intentioned compliments from readers patting me for bringing my mother’s story to the fore, for making her famous. You are so brave, it takes a lot of courage, I hear. No. Bravery and courage were not silver-stacked in my quiver to pull out at convenience. It was just about plucking the right sur in her voice, her truth. I am, what we call in political parlance, the spokesperson for her story. I don’t want to take any credit for it. If only my mother would briefly return without spooking (and ghungroos), to inform that I didn’t make her famous, it’s them readers, and instead of me, they should never stop talking about her.

For, if this serves as a fitting tribute to her who is often reductively introduced as my mother, but whom I always re-introduce as a woman of her own making, her own personhood first before any permanent labels are applied; this sher of Allama Iqbal, read aloud in Pakeezah’s closing shot, places the writer as merely a gardener in the splendour.

Hazaaron saal nargis apni be-noori pe roti hai

Badi mushkil se hota hai chaman mein deeda-war paida

It can be loosely interpreted as:

Unadmired, the narcissus weeps a thousand years

For an aesthete to cherish its inimitable beautyhttps://medium.com/media/a06b39cde5cfca3979a11601c94933dc/href[image error]

November 9, 2024

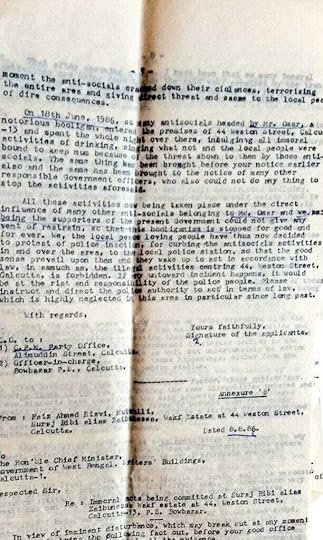

Raseed-E-Zindagi — from a tawaif’s treasure box

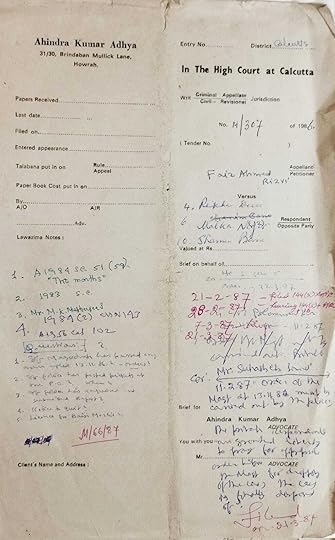

An unnamed love letter on a Hindi typewriter, a High Court eviction lawsuit by a goon, kotha rent receipts, music concert handbills, professional singing-dancing trade license, moral character certificate from an MLA; shaky signatures & subpoenas spill an era.

I’ve just discovered a love letter sent to my mother by her unnamed lover in 1975.

He identifies himself as ‘faqat ganwar toh ganwar hai,’ but comes across as an aesthete.

He begins: Hamari namurad ummedon ki bahar, sukoon-e-qalb, malka-e-hayat hamesha khush raho.

Uff allah.

Check the sher in the beginning.

Chashm-e-purnam khareed sakta hoon

Zulf barham khareed sakta hoon

Meri khushiyan agarche bik jaayein

Aap ka gham khareed sakta hoon

Consider the high-flown intro line & Hindi typewriter used.

But that’s not all.

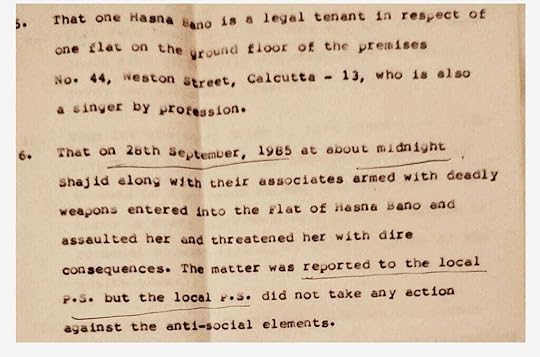

I also discovered how mother’s landlord was dragging her & other tawaifs to high court, to evict them from the kotha.

The women were running to court in the afternoon & dancing in the kotha at night.

Crazy.

The landlord called them immoral & prostitutes.

One of the tawaifs named in that lawsuit (see pix) is this lady, a ‘flim actress’ qawwala, a pamphlet of whose grand outstation show my mother had carefully held on to.

The landlord said the baijis were singing, dancing, indulging in illegal trade.

He calls it ‘baiji business.’

He said it disturbed the peace of the imambara in the kotha, above which they performed.

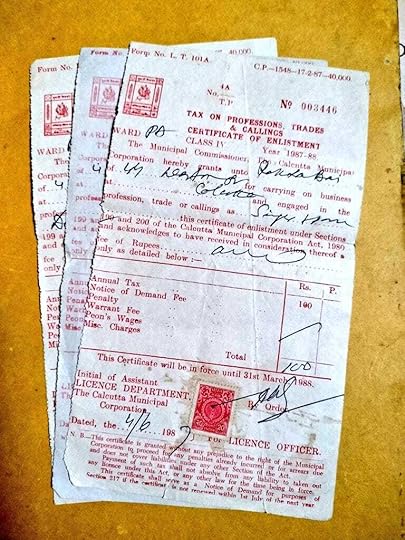

The women had a professional trade license as singer-dancer they framed and hung in their rooms to avoid hassle.

(Mother’s tax license in this pix.)

The baijis then got together, counter-claiming that the landlord set goons & weapons on them.

Landlord then said the baijis got a goon Omar who drank & sang ‘what not’ with them.

Ab aadmi pi ke thoda toh besura gayega.

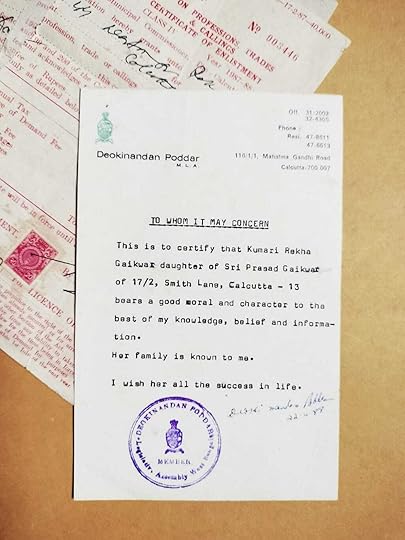

Here’s a pix of the tawaifs, mostly uneducated, who signed the affidavit saying they were being bullied. My mother signs as Rekha.

Mother had to procure a character certificate from a local Congress MLA to prove she had good moral bearings.

Mother saved important documents for me to discover after her death.

Here’s one showing she rented a room in the said kotha in 1973, for Rs250 a month.

She marked her life in receipts, paperwork she could not fully grasp.

Which is why she saved my school reports even more carefully.

Here’s one from the time i was in class 2.

The remarks section says: ‘Could do better with a little more effort.’

Now consider I stood 1st in class.

Teachers were brutal.

Thank goodness mother checked only rank.

Last night, before going to bed, I was thinking of the word faqat. I googled its meaning.

Merely, simply, only.

Today, it came back to me both as a surprise and a story to explore, perchance.

Perhaps, maybe, possibly.

[image error]July 18, 2022

How did I become a writer?

It took me 22 years to get here

I am often asked to give tips and advice. Am still clueless where to start.

It took me 22 years to get here.

In 2000, when I was making & selling desi daaru for 5 rupees a glass with my relatives in a slum in Poona, I spotted an ad that changed my life.

It was an ad to apply for a medical transcriptionist job. I didn’t know what it meant. All I understood from the newspaper ad is that the qualification was for an English-proficient candidate. It was either this or my cousins would soon find me a bell-boy job in a hotel.

I went to the Deepak Nitrite office in Yerwada and sat for the aptitude test. I was an Arts student bunking college, and here I was, trying to bluff my way into my mother’s dream of me becoming a doctor. They hired me saying I had scored more than some science applicants.

How was that possible? They were looking for candidates with basic grammar and spelling skills. I had read a ton of books in boarding school in Darjeeling. That helped. They trained me with others for two months. I was decent in transcribing a doctor’s audio notes into text.

After two months they asked me to sign a contract saying I wouldn’t leave — bonus was dangled to lure. I panicked. I didn’t want to be tied to a chair. I became confident that I did not have to rely on my mother’s family for work either. I returned to Calcutta to try my luck.

I wasn’t a particularly bright student in school, or college. Having no one at home in the kotha to guide me, I didn’t know where to start? How would I ever become the writer I had dreamed of, reading books secretly as a child, and as an adult who didn’t have any precedent?

Yet again I scoured newspapers to apply. I worked as a salesman in two clothing stores, both times quitting in two days. I applied for a tele-caller post at The Grand Oberoi. They rejected me because I was too nervous to talk in a crowd of aspirants who were all affluent.

But.

I befriended a girl there. We exchanged landline numbers. We began chatting. One day, she said she got the job as a tele-caller for a gourmet club at the Grand Oberoi where they telephoned guests and offered a club membership. They needed an errand boy to deliver documents.

Why don’t you apply, she said. I met the manager. He hired me. My first assignment was to deliver the membership package to a milkman in a cowshed some 50 kms away from the city. Am not joking. I nearly fell into a mountain of shit. The milkman offered no fresh cream of thought, or salve if i had fallen deep.

Another time I was sent to a tannery. I ran out after delivering the document. The stench in the place curdled my tummy. A vomit volcano reached my mouth. My manager lent me his dinner jacket for an art show. I memorised the spelling before sipping Beaujolais nouveau red wine. I looked at art like a curious bird, trying to shape the face of Jennifer Lopez in an abstract figure.

So here I was now, between the bourgeoisie, the bordello, and the bread work. I could tell no one where I went after office hours. The gourmet club wrapped up in six months. They said their membership quota was complete. Across the road, Citibank had a call-center.

I applied there. Got the job. It was Valentines Day. I got a rose and thought I was special. Anyways, I despised telling Bengalis who called repeatedly all day to check the balance in their account. As if it was looted in their afternoon nap time nightmare. I drew doodles too.

I quit in 2002 and decided to move to the fancy GE Electric call-center in Gurgaon. The malls were shining, the big-mac was tempting. I wanted to make friends. Live. I worked there as a Fraud Specialist. Hai na groovy?

So I had to look into Exxon Mobil gas card accounts and report any suspicious purchase activity. I chose Dave Matthews as my American name. Like the band. My remote location was I think Massachusetts. I still can’t pronounce it without sounding vulgar.

After 6 months there, I was asked to talk like Americans. They put us all in a class. Say de-mah-cracy. Not demo-cracy. Say akk-ount. Not a-ccount. I quit. I have a neutral accent. It was already hard pronouncing Maa-say-chu-setts.

A girl, who is still a very close friend, staying in the same Pg accommodation where I was, asked me to apply at her company, Smartanalyst. I had my next job in a week! At least here I didn’t have to talk. We scoured the internet for info on Nike shoes and lollipops in space.

I was reading a lot of info. The writing bug would soon kick in. I started blogging. Poems. All bloggers are undiscovered poets. Fell in love. Took some rash decisions. Between 2004 to 2007, I worked at WNS, Salegen, Edittalk (legal transcription), Purplepatch, KPIT Cummins.

At KPIT, I was developing Blogeverywhere for Sabeer Bhatia. It never took off. I felt my career as a writer was here. But this was the end. Sab khatm! I got to write movie reviews for Seventymm in Bangalore. A tech magazine printed my article about pendrives. That was it!

In 2008, confident, I moved to Bombay to write film scripts. Worked at Bigflix, Hill Road Media (Aakar Patel as boss), Midday, Bombay Bitch, Buzzintown, Business of Cinema, Everymedia, Scroll.

Freelanced for The Hindu, Firstpost, Arre, News18, The Wire, Satyagrah, The Deccan Herald, Film Companion, Himal Southasian, The Logical Indian, Bombay Dost, Kitaab, Outlook and Pinkvilla.

Tab jaake my novel came out in 2018.

Am I now ready to be identified as a writer? Umm, yes, but how do I tell others that I did not train anywhere, I don’t have any special knowledge to impart.

All I know is that in my spare time I read Beauvoir and Kierkegaard watched Rohmer and Ozu films, listened to Don McLean sing about Gogh’s starry nights, or the many Pakistani chanteuses sing ghazals of their beloved poets.

I read. I traveled the country. I wrote prolifically, especially when no one was reading and what I now also consider unreadable. 18 years ago I attempted my first couplet:

If we make death sound easier

Is it not so with the alibi of life

That must have freed me to write.

[image error]

[image error]

November 12, 2021

Kavita Paudwal: Singing Under Her Mother’s Watch

How her playback-singing career was nipped in the bud.

It was Kavita’s eighteenth birthday.

Her mother Anuradha Paudwal took her to the recording studio and said, ‘Yaad hai bachpan mein maine tumhe yahan ek khaas tohfa diya tha.’

‘Yes,’ Kavita said. ‘With Lata ji and Kishore uncle. In Tohfa, my first song.’

She sang from her memory.

Ringa-ringa roses, pocket full of poses, hasha-busha, all fall down!

They laughed in sync. It sounded like a mother-daughter duet gone awry, one in a high pitch bellow, the other a low giggle.

https://medium.com/media/c50f3e81a26b6ca5321d4bf233429acc/href‘Ab tum badi ho gayi ho. Aaj tumhara pehla solo recording hai,’ said Anuradha.

‘Oh Mummy,’ Kavita said. ‘You are the best.’

‘Hmn, theek hai beta, thank you, tum bhi ho jaogi best, dheere-dheere, bas meri tarah bano.’

‘Who’s the heroine?’

‘Bhatt saab ki beti, Pooja.’

‘Oh wow. Pooja Bhatt. I love her. She is my favourite.’

Composers Nadeem-Shravan greeted Kavita, rehearsed a few times and asked her to step into the recording booth.

She sang without a hiccup.

Tu mera meherbaan

Yeh jaan gaye sab

Main bhi hoon teri jaan

Yeh jaan gaye sab

Tu mera meherbaan

The song was ready by lunch.

‘Mummy, my friends have organised a small pool party at Sun and Sand. Can I please go?’ Kavita asked.

‘Ghar mein pooja hai beta, aur family ke saath…’ said Anuradha.

Music producer Gulshan Kumar piped in. ‘Jaane do na, ab woh bacchi thodi rahi.’

Anuradha looked sternly at Kavita and said: ‘Par barah baje se ek minute late nahi.’

The rules were made from fairy tales Kavita read to her mother as a child.

‘Thank you mummy. My favourite mummy.’

As if she had more than one.

As Kavita was leaving, she opened the gift box Gulshan Kumar had given her.

‘Yeh kya hai?’ she asked.

It was a bright red organza saree.

‘Tumhari pehli saree,’ he said.

‘Thank you uncle ji,’ she said dejectedly.

‘Yehi pehen ke jaana,’ Anuradha said.

‘Mummy it’s a pool party, jungle theme hai.’

‘Kya matlab?’

‘Matlab western dress.’

‘Kya? Woh chhote-chhote knicker pehnogi?’

‘Two piece,’ Gulshan said.

Anuradha stared at him to exhibit her irritation.

Kavita fumbled with the saree that evening. Anuradha counted and folded eighteen chunnats, ruffles in the six-yard cloth to secure and fasten Kavita’s modesty, adding safety pins to lock the drape to her full-sleeved blouse.

‘Kuch galat karne se pehle athra baar sochna,’ Anuradha gently tucked in her morality.

‘I can hardly walk in this,’ Kavita complained.

‘Dheere dheere, meri tarah, sab seekh jaogi,’ Anuradha smiled and assured her.

She sent Kavita to the party with the driver.

After she left, Anuradha telephoned Gulshan and confessed, ‘Mujhe toh darr lag raha hai. Kahin woh saree na utaar de.’

‘Arre, tum toh khamakha, chalo hum jaa ke dekhte hain,’ he said.

They went to the venue. They were handed animal masks at the door. Inside, everyone wore one. They spotted a lion, a tiger, a wolf, a cat, a bear, a dog, a monkey, and several other wild animals but no reptiles around the pool.

Anuradha got an elephant mask. Gulshan wore a horse face. They hid in a corner to spy.

‘Woh rahi,’ Gulshan spotted Kavita in a deer mask. Her saree was still the untouched gift she was neatly wrapped in.

Her friends were dancing around the pool. Some were dressed in animal costumes. Kavita looked like a regal doe-faced queen in a stuffed toy shop.

‘Mata rani ka laakh laakh shukar hai,’ Anuradha heaved.

They noticed Kavita’s friends were requesting her to sing. She announced how she had just recorded a song in the afternoon. They cheered and asked her to sing it. She took the microphone from the live band that was playing and sang.

Pyaasi raat din tadapu tere bin

Door na ja abb dilruba

Kya hai bebasi kyun hain berukhi

Aa zara tu mere paas aa

Mere sanam teri kasam

Raaj-e-dil mujhko bata

Dhadkano ki jubaan jaan gaye sab

‘Kaafi accha gaa leti hai live bhi,’ Gulshan said.

‘Meri beti hai, mujh pe hi gayi hai,’ Anuradha said.

A young boy wearing a tiger mask got close to Kavita, following her lyrics as invitation.

‘Yeh kaun hai?’ Gulshan asked.

Gulshan tried to step forward to intervene.

‘Abhi do minute baaki hai.’ Anuradha looked at her gold watch and stopped him. ‘Gaana poora gaa lene do.’

Kavita sang and danced.

Ho raat chaandni chhede raagini

Baahon mein mujhe thaam le

Kya haseen sama hum bhi hain jawaan

Husn ka mere jaam le

Jeene na de yeh bekhudi

Betaabiyaan na badha

Pyaar ki daastaan jaan gaye sab

The young man holding a drink, grabbed her in his arms.

The aroused tiger kissed the deer.

Kavita reacted by pushing him into the swimming pool and sang the last lines: Tu mera meherbaan, yeh jaan gaye sab.

The drummer played the final four beats to a dramatic treble effect.

Her friends clapped. She kept the mike, thanked her friends, looked at her watch and rushed out, past her mother and uncle, not identifying them in masks. She was following her mother’s rules.

‘Iska gaana bandh kar dein kya?’ Gulshan asked.

‘Nahi, uska passion hai, sirf genre badal denge,’ Anuradha said.

Since then, Kavita has been singing only bhajans. Prolific, never popular.

https://medium.com/media/3a3d96549930327fcb83289e86a5127d/hrefDisclaimer: This is a work of fan fiction or more formally known as real person fiction. It is not for any commercial use. Read more on Real Person Fiction here.

[image error]November 9, 2021

Parveen Sultana: What’s Hate Got To Do With Singing?

How she was tricked to sing Hamein Tumse Pyar Kitna Yeh Hum Nahi Jaante

After Kishore Kumar recorded Hamein Tumse Pyar Kitna, music composer R D Burman congratulated him and said he was thinking of approaching classical singer Parveen Sultana for another version of the melody.

‘Why not Asha?’ Kumar asked.

‘Because the situation in the film is such,’ he said, ‘A classical singer sings it on stage. I have composed it in raag Bhairavi.’

‘Oh,’ Kumar said. ‘Call her.’

‘I am scared. She hates Hindi film songs. Nafrat hai.’

‘How do you know?’

‘Don’t you remember, her song Kaun Gali Gayo Shyam was used in the background in Pakeezah. She was expecting better.’

‘Talk to her husband Dilshad.’

https://medium.com/media/2dfdce8535e27634766dce5f47f861c1/hrefBurman telephoned. Luckily, Dilshad picked up the receiver. Burman explained the situation. Dilshad said he would have a word with her and ask her to call back.

Burman crossed his fingers.

That night, when Dilshad broached the subject, Parveen reacted sharply.

‘Nafrat hai, nafrat,’ she said. ‘Talent ki koi qadar hi nahi inn logon ko. Na classical ka knowledge. Filmon mein gaana jaise qafas mein bulbul hai miya.’

She compared Hindi film songs to a talented bird in a cage. Dilshad called Burman the next morning and said they’ll have to find another way.

Kishore Kumar heard of it and called her. He explained the situation.

‘Can I sing you a line?’ he asked.

‘Ji,’ Parveen was curt.

He cleared his throat and sang.

Hamein tumse pyar kitna, yeh hum nahi jaante

Magar jee nahi sakte tumhare bina

Kishore stretched the last syllable like a meend to impress her.

‘Nafrat,’ she said and hung up.

Kishore told Burman to approach Kishori instead.

‘Amonkar?, she’s scarier,’ he said.

Asha Bhosle said she has a plan.

One evening, when Parveen Sultana was performing at Shanmukhananda Hall, the three musicians, Kishore, Burman and Asha sat in the centre, enjoying her performance.

As Parveen thanked the audience at the end of the show, Asha stood up and said ‘Parveen ji.’

The whole auditorium turned to her. Audience gasped and murmured.

‘Parveen ji,’ Bhosle said, ‘Ek chhoti si request hai. Ek gaana aap apne andaaz mein aagar gaa dein toh please.’

Parveen was cornered. She could not say no to Asha Bhosle, her idol.

Asha sang in a low octave, her voice filled the quiet room like an echo in an enchanted forest.

Hamein tumse pyar kitna, yeh hum nahi jaante

Magar jee nahi sakte tumhare bina

Parveen felt like she had to respond to Asha as if they were singing a jugalbandi, a duet. She followed it in her own thumri style, adding alaaps and taans, showing how a traditional sounding Hindi film geet can be given a classical twist.

Her impromptu performance was rewarded with a standing ovation. She was stunned by the audience’s reaction. Parveen’s hate for Hindi film songs was being flipped over.

She agreed to sing it on her own terms because it was based on a raag and with lyrics by Majrooh Sultanpuri, whom she respected. The music room was filled with a hundred violinists, several sarod, sitar and santoor players, a flautist, a sarangi player. She was overwhelmed by Burman’s troupe. She sang it in one take.

It fetched her a Filmfare best playback trophy, a song for which Kishore Kumar was also nominated but lost.

As a gesture of her appreciation, she decided to include the song in her concerts. In the end, she would smile and tell the audience, ‘Aur yeh geet aap sabhi ke liye, jinke bina hum kuch bhi nahi jaante.’

https://medium.com/media/7fe6ed6105d40d9cb41863ba8bb2214b/hrefDisclaimer: This is a work of fan fiction or more formally known as real person fiction. It is not for any commercial use. Read more on Real Person Fiction here.

[image error]Annette Pinto: The Girl Who Gargled For R D Burman

A back-up vocalist who helped the composer create a signature tune.

‘Who’s that girl?’ R D Burman asked his musicians.

He had just heard the James Bond theme-styled title track Gunmaster G9 from the film Surakksha on the radio. Music composer Bappi Lahiri was singing to funky disco beats. Synth pop, claps, sultry back-up vocals, the tune had all the elements for a hit sound. Midway between the marching beat, a woman warbled the hero’s codename: Gunmaster G9. It was a distinctly anglophone voice.

https://medium.com/media/8f62057f10f0a445ad7b40c9f1883788/href‘That’s Pinto, Annette Pinto,’ said the madal player sitting with Burman in his studio.

‘Like Bond, James Bond haan,’ Burman smiled. ‘She seems to be trained for opera. I’d like to meet her.’

A few days later, Pinto arrived at the Film Center recording studio in Tardeo. She was carrying a flask of hot water.

Burman immediately sensed that Pinto would not be able to sing.

‘Do you have a sore throat?’ he asked.

‘Sorry sir,’ she said, ‘Yes, but I gargle. It will be fine.’

‘Okay, gargle,’ he said.

She did as told. The hot water gurgled in her mouth.

Ga-gaa-ga-gaa-geee-gee-geee-gee-grl-grll-grl-grll-goo-go-goo-go

She carefully spat out in a cup and smiled awkwardly.

‘Even your gargle is musical, in teentaal,’ Burman said to comfort her.

She chuckled to contain her shyness.

‘Shall we start?’ Burman asked.

‘Actually, sir,’ she said, ‘I have sung for you before in The Great Gambler, The Burning Train.’

‘Oh,’ Burman said, ‘I don’t recall.’

‘I do back-up vocals mainly. So many of us girls come together, how will you notice,’ she said.

‘Then I must call you another time,’ he said.

She felt rejected and left without registering her displeasure. She thought she had spoken inappropriately about having sung for him. Back-up vocals never get to the front. The lead was reserved only for the sweet Indian voices of the singing sisters. Hers was the sultry voice of the moll, the vamp, the westernised voice of disco and cabaret, opera and gospel, sounds discordant with traditional Hindi film songs. Composer used her foreign voice as a siren’s call, to mislead, to open for an established lead singer. She wasn’t expecting a lead song today, but was now leaving, afraid that she was losing out on even those back-up sessions.

A week later, she was asked to sing along with Kishore Kumar.

‘Oh my god, I could never,’ she said to Burman.

‘Why not?’ he asked.

‘I mean sir, he is a legend and me?’

‘Why not?’

‘Okay, I’ll try. But I am very nervous.’

‘You won’t be when you read the lyrics.’

Pinto read the lyric sheet.

Chhodo sanam kahe ka gam, haste raho, khilte raho

Mit jayega sara gila, humse gale milte raho

‘The song is set in a club. You croon in your own style. And add your teentaal,’ Burman joked.

Pinto sang her two lines confidently and added the non-lexical vocables: Ai-yai-yai-yaa-ya-ya-ya-yaa-ai-yai-ya-yaa-ya-ya-ya-yaa.

https://medium.com/media/ac1f76c50c7715e0a41de541446a5499/hrefBurman was pleased with her singing. She was paid more than a back-up vocal, though still less than Kishore Kumar. She did not object. It was a start.

The song did reasonably well on the radio but she did not get the solos she was expecting.

A year later, she ran into Burman. He asked how she was doing professionally.

‘The same sir,’ she said, trying to appear unfazed.

‘Why don’t you drop by tomorrow?’ he said.

She did.

He put the microphone before her, handed her a glass of water, and said: ‘Gargle.’

She laughed and did as he instructed.

‘It is still musical, only this time, more memorable,’ he said.

In the film Satte Pe Satta, the gargle was used effectively as the background score to mark the villain’s entry.

It is considered one of Hindi cinema’s most unique and terrifying sounds, so unlike Pinto, and once heard, never forgotten.

https://medium.com/media/130184dd28dde6ac9bfcb471f7372d75/hrefDisclaimer: This is a work of fan fiction or more formally known as real person fiction. It is not for any commercial use. Read more on Real Person Fiction here.

[image error]November 8, 2021

Runa Laila: Hungry For A Song

Do Deewane Sheher Mein

When Runa Laila came to Bombay, she did not want to stay at the Taj hotel despite its panoramic view of the sea.

‘Oh, I love this city so much, I want a place of my own here,’ she said to music composer Jaidev, who had invited her from Bangladesh to sing a song in a film.

‘Let’s first record the song,’ he said,

‘No, please, Jaidev ji,’ she said.

‘But you have a house in Dhaka!’ he said.

‘But artists belong everywhere, no?’ she said. ‘We are like the wind, no fixed roots, no fixed home.’

Her exuberance left him with no choice.

‘Leave it to me,’ she said, ‘I will find out myself.’

Runa walked around the queen’s necklace, admiring the art deco buildings dotted across the road. She walked barefoot in the cool evening air, watching the sun, listening to the waves, sauntering at the chowpatty, humming and cooing.

At sunset, she climbed up the Charni overbridge for a bird’s eye view of the skyline. She took a taxi to Malabar Hill and sipped tea at Naaz café. She visited the Bandra fort, ate bhelpuri at Juhu beach and returned to Jaidev’s house at night.

‘Did you find a house?’ he asked.

‘No, I wasn’t looking. I just wanted to soak in the city’s sights and sounds,’ she said.

‘And what did you discover?’ he asked.

‘It is easy to get lost here.’

‘But you find your way back.’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘That is the other thing I noticed. The city never rests. Shall we record tomorrow?’

Jaidev was relieved to hear that.

Runa met her shy co-singer Bhupinder at the studio. They sang the upbeat melody Do Deewane Sheher Mein.

After the recording, in a singsong voice, Runa said: ‘Every time I had to sing aab-o-dana dhundte hain, I felt hungry for sa-bu-dana.’

Everyone laughed.

Lyricist Gulzar said: ‘Laazim hai itna umda gaane ke baad bhookh toh lagegi.’

Where can I get the best sabudana vada? she asked.

‘Matunga,’ said the drummer.

‘Dadar,’ said the violinist.

‘East,’ said the musician playing the cabasa.

‘West,’ said Bhupinder, picking up his guitar and strumming a string.

‘Oh ho,’ said Jaidev. ‘Why don’t you all go out and find out.’

‘Do deewane sheher mein, raat mein ya dopeher main, sa-bu-dana dhundte hain ek…’ Runa laughed before she could complete the line.

The musicians jumped into a taxi and set off in search. Runa felt at home in the world.

https://medium.com/media/92ac2425e6aa9c307a619803ba312120/hrefDisclaimer: This is a work of fan fiction or more formally known as real person fiction. It is not for any commercial use. Read more on Real Person Fiction here.

[image error]October 17, 2021

SRK, Is Your Silence Hindustani?

Get up, stand up, stand up for your rights. Speak up, your silence is hurting.

Sir, everyone should know by now that your mother was a social worker in contact with members of the Indian National Congress. Your father was a freedom fighter. Naturally, you can be expected to carry forward their beliefs and share the same ideology. Why shouldn’t you? But your deafening silence, that’s unlike your patriotic parents. Come to think of it, that’s unlike your own high-energy style too. Picture shown above is not for illustration purpose only.

The reason your son is in jail is not because he wanted to have a blast, but because you don’t walk the line that the establishment wants you to. What have you done to upset them? You’ve even endorsed those stinky national-pride gutka brands in godawful ads.

Your films have questionable merit but your character, oh no sir that is unimpeachable.

Your off-camera wit, charisma, and your dimples bolster half your everlasting appeal. Like in one of your better films, you have the nation’s women, children, and men eating chick pea out of your hands the way you fed pigeons with an assuring ‘aao aao aao’ feed call. You are an ingenious pied piper.

The establishment wants to employ precisely this imperishable skill of yours to herd us into an Orwellian nightmare. You must have politely declined to be a part of their evil schemes. You can distinguish between film and reality. They cannot.

Folks from the film industry are silently standing in your support. They are afraid to speak up because the attacks will begin with a tax raid. And it will be relentless bullying after that.

You have always kept a distance from politics. It has benefited you. But now they have come for you. Your family is being harassed. It will be your friends next. If you do not speak up now, you will forever silence your friends and supporters. When they are targeted, they will say you, king-like, didn’t say a word, why should they who are like feeble subjects before you? Who will stand for them? The film industry’s syncretic roots are being systematically dismantled to establish a new one nation, one religion order.

Speak up before your industry becomes a tool for political propaganda. We can see how a section of it has already become servile. Do not let them dictate how to make your films. Do not let them dictate how to lead your lives. They’ve already ruined radio, print, and television for generations to come. This country leads with the most Internet shutdowns in the world.

Your well-wishers will say do not speak up. Do not! You have everything to lose. Yes, you do, and no, you don’t. You have your father’s legacy, your mother’s spirit, and the gift to pass it on to your own children who are being tested.

Nobody doubts that you are a hero in reel and real life. Just say something. Don’t be quiet, even god tweets. Be human like us. Give us hope. Give us courage. Tell us you will not tolerate this nonsense. Tell us you will fight back. Don’t be mute. Tell us only two words if three will be too damaging (flag waving optional): Inquilab Zindabad.