Fraser Simons's Blog

May 28, 2021

You Need To Watch Dynamo Dream

The first episode of Dynamo came out yesterday and it had not really been on my radar. I saw footage of CGI being worked on for this, but I didn’t know it was for this title. There’s a scene where the main character walks onto a lift and is brought down a few levels which had been all over my Youtube quite some time ago, so you may recognize that scene as well.

Little did I know that it was for something like this.

If you like cyberpunk but also hate the current aesthetic Hollywood has placed it in, as in, regressive and aggressively technophobic borderline, or full-on racist Asian milieu—this is for you. The very first thing you will notice is that the extremely beautiful shots of this cyberpunk world look quite different than what we’ve been seeing. Yet we also recognize this as a cyberpunk aesthetic as well. The progression of technology and the oppressive state has given way to a recognizable dystopic motif, that’s clear, but there is obvious care to not ground it in the 80s fear of Asian technologies taking over western culture.

There are numerous tracking shots interspersed, reminiscent of Ghost in the Shell when there were orchestral arrangements that basically just showcase slice-of-life moments. And as in that movie, so too are these shots so good at providing soft worldbuilding moments and texture. Also: it is just completely gorgeous. The CGI looks as good as Blade Runner to me. Some things must be practically designed and other things support those vivid details in really effective compositions.

Now, people who think cyberpunk isn’t punk enough, I know you’re coming for me. But isn’t it just cyber now because there’s no punk in the subgenre anymore? No; wrong; incorrect; literally never been true, except for within the mainstream depiction of the subgenre. But that is literally the most diluted, co-opted state of the sub-genre and it arguably applies to ALL genres.

So, having said that, this is definitely cyberpunk in my book, and it is in a new, subversive way; which I happen to love. The agency the protagonist, a young woman who is clearly impoverished, hinges on futuristic technology which is tied to disenfranchisement and oppression.

In a world where everybody is eating what appears to be fast food, our woman is side hustling as a salad vendor. She makes small salads inside of cups and sells them, selling literal nourishment to people who never receive any.

Then, when the state is about to commit violence in front of her, she uses what she has at hand to disrupt it and save lives—which catapults her into the awareness of a faction we do not yet know, and subsequent events in future episodes.

All I can see is: yes, more of this, please. Please watch this. It is free! It is so good. And I hope someone picks up this show or supports the creators, or whatever needs to happen to continue this happens.

Here is the link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LsGZ_2RuJ2A

As for me, if you like this I am on Medium, I appear over @ cyberpunks.com and I am on Twitter and Goodreads.

December 22, 2020

Cyberpunk 2077: Is This To Be An Empathy Test?

Cyberpunk 2077 is an adaptation and extrapolation of the popular tabletop pen-and-paper role-playing game Cyberpunk, originally published in 1988. The video game uses an extrapolation of the setting and Interlock system, translated to video game format.

When I finished the game, credits rolled. And rolled. And rolled. More than 15 minutes went by.

Now, days later, as I reflect on more than 70 hours of playtime, Cyberpunk 2077 feels like many people have had their hands in the pie. Its strengths and weaknesses stem from its massive ambition, marketing, and promises.

Different ExperiencesI played CP2077 on a Ryzen 7 3700x with 32 gigs of RAM and an RX 2700 GPU. I was able to get around 35 FPS at 1440p without noticeable drops (except when looking in mirrors), and I played on ultra-settings without ray tracing on. I began playing it with the rest of the PC consumers with the day 1 patch.

As a crafted experience, I can say that it is the most impressive looking game I've ever played, and my playthrough seems to be a fortunate one, with maybe a handful of glitches or bugs across the entire 70 hours. None of which were remotely game-breaking. I was never unable to progress in the story. I never had a crash. The most annoying thing I experienced was sometimes crosshairs from a gun would continue to stay onscreen after it was holstered.

I mention this because I think a major component of why I come away with a positive experience is because my computer could deliver the intended experience. And Cyberpunk 2077 is unrivaled in its execution of a funneled narrative. Characters and environments have never felt more genuine and cinematic.

The sound design is some of the best I've heard, and it's perfect in every aspect of the game. From the sound of a throaty exhaust to the scraping of metal-tipped hands against hardwood, the sound is superb and adds to the immersion.

The World

With a setting as old as Cyberpunk, there will be consumers who are familiar with the setting and have a grasp on the worldbuilding. For the uninitiated, however—of which, I think most customers will be—the aesthetic and gameplay elements the marketing team used in advertisements will be the primary hook. The game doesn’t go out of its way to communicate that it is anything more than that, either.

What was most compelling about Night City was the meticulous detail and care devs clearly put into every nook and cranny of the city. Distinct and disparate, no part of it feels reused or like its filler. It is the most gorgeous and well-realized environment I've encountered in a video game.

Yet the gangs, fixers, and side jobs located within it feel one dimensional when viewed from a macro, worldbuilding perspective.

Typical fixer missions are varied enough and have different small bits of story, but usually just elucidating that specific mission and its characters. You’ll find little bits of lore some of the time, which augment the siloed stories, but often don’t give a wider context to help situate the faction you’re interacting with.

The gangs seem to have a central theme, but I never learned why they were actually there from a worldbuilding perspective, beyond the fact that the game wants you to be looting and shooting.

Culturally, the gang elements are too often a pastiche and don’t feel real. They have scripted lines that are often dehumanizing and feel unrealistic. Some of them don't even make any sense. They'll find a dead body and start yelling for you to come out, "cunt", or some other misogynistic pejorative. How do they know it's a woman? Making them all say and act that way feels so cheap, encouraging you to take them out because they're demonstrably “bad” people. And it doesn’t matter what kind of mission it is. Context doesn’t matter.

With the bits of lore you’ll find all over the place (often repeated), it feels like a missed opportunity to not humanize and characterize the gang identities as a whole; even if you are spending most of your time mowing them down, at least you’d come to understand why the city is the way it is and what its general makeup is better than just knowing which gang claims which area of the city.

The world feels overly concerned with aesthetics that the player never gets context for, so it feels like a caricature used for aesthetic purposes only.

For instance, Arasaka, the megacorporation controlling/running Night City, has a highly traditional, tyrannical, Japanese businessman who has had his life extended with cybernetics. He’s over one hundred years old and controls Arasaka with an iron fist. The inference on my part is that locations in Night City with heavy Asian aesthetics are there because of this megacorp’s influence. But it still feels strange because, in other lore given, the city has been run by other corporations not that long ago and had other cultural influences asserted. So why is Little China, Japantown, and Kabuki a weird pastiche and the only place that seems to assert its cultural influence on the city? When you enter other areas, they don’t look like they’re trying to recreate foreign cultures. Is it because of the Arasaka influence? Possibly, but I never found any lore that explained it. Visually, this aesthetic dominated my playthrough.

The result is a siloed microworld that feels like it might be there simply to justify some of the predominantly Asian gangs, who seem to be basically just cyberized yakuza and come up fairly often in fixer missions. The main story also springboards off some of these locations, so the game really wants this look to make an impression on the player.

When you explore in-depth, all of the interactable, consumable portions of the city have a faux quality because you can only look at them. Sometimes you can buy food from a couple of vendors and clothes, but everything exists solely to be interacted with in a hyper-specific way, rather than extrapolated from a perspective divorced from what would be merely aesthetically interesting and actually realistic enough to let V feel like a character that is a part of this world.

You can sleep with and date a few different people, depending on your gender presentation, but the relationship's extent beyond that varies. There are some texts between characters, but you don't get to, say, go home and do anything with them. Their interactions with you in person are the same as though you had phoned them.

You can talk to people on the sidewalk, but they have a regurgitated one-liner and then go back to what they're doing. You can't go up to a gang member and talk to them because once they see you, they’ll attack you if you get too close.

The only things that feel genuinely next level are the prescriptive story elements. And that's okay! It just doesn't jive with the level of detail or how much you think you'll be able to interact with things when you first see them. Marketing makes it seem like the world at large may be something you can interact with, but those all end up being the curated narratives.

Because the worldbuilding framework is from a first-wave cyberpunk perspective, unfortunately, pitfalls like techno-orientalism are prevalent.

The themes around the commodification of those things that make us human, from our body, faith, and art, are all interesting themes present in the genre—but here they are skewed toward fetishizing minorities and subcultures, just as first-wave cyberpunk texts tended to do.

V is ostensibly a cyberpunk and it follows that they would be a part of the same subgroup as the minorities who are underrepresented and lacking nuance in the CP2077 world, but V is actually traversing the story with their only integration into a subculture being that they’re a mercenary. With few exceptions, they all seem to not really share punk values, either. Some take jobs from corps (you certainly can if you want), some don’t like the corps but aren’t particularly anti-establishment or pro direct action. Most just seem to hang out at a bar. You don’t hear about what they do on the news or in the world. You don’t get jobs from fixers that are ideologically aligned with being punk. And you don’t integrate with any other subcultures when out of the main narratives.

The exploitation of people and the world's general themes and sensibilities still feel firmly rooted in the late 80s, early 90s. It is not aware enough to fully realize an actual subculture or even the dynamics of criminal elements in the city, so it frames the story from a mainstream perspective for mass appeal.

The problem is that, with so many people consuming the game, this becomes the default that those consumers will adopt. It has a responsibility precisely because it is so popular and will become a part of the general intellect. Rather than be progressive with its themes and push mainstream depiction of cyberpunk to something in line with what can be found in literature today, it is regressive.

Ultimately, the worldbuilding is the most disappointing aspect of Cyberpunk 2077. The main narratives, however, are a different story.

Story

Arguably, the most important thing for a role-playing game experience is the story. In 2077, you play V, a mercenary on the edges of society trying to make it big in Night City. In classic cyberpunk genre fashion, a chance at a big score drops into your relatively inexperienced hands, and you seize it. A heist is planned; it doesn't go as planned—and Johnny Silverhand, a long-dead anarchist and misogynistic jerk—basically a proto-typical embodiment of 70’s rock ethos—ends up in your head. He has his own agenda, and V can either go along, get along, or make their own decisions about what to do next. For the most part.

The story beats are as meticulously crafted as corners of Night City. The character animations are the most advanced I’ve ever seen—: they’ll smoke a cigarette for a portion of the conversation, stub it out, then get up and pace nervously while delivering their lines. Their emotions will be written on their face and flow naturally. They'll touch items or other people in the scene. They look and act like real people and sound like it too.

There’s a 4-part storyline with a trans character in which you just won’t ever learn their story unless you talk with them and earn their trust. You can go through the whole narrative and help them out (or not), and never learn much about them. But if you spend the time and ask questions, you'll always get something from these storylines, even if they initially seem to be just another gig on the map.

Because the game's worldbuilding, including in-game ads, is blind to its own defaultism, stories like this are absolutely vital. I wish there were more of them and I hope the free DLC forthcoming are things like this.

2077 is populated with genuine, human moments. They communicate why you should care about the city and the people you encounter. And most importantly: these moments define V as much as the main storyline.

Whether intentional or purely a byproduct of how each facet of the game was developed, these stories augment the play experience a tremendous amount.

What I remember most is finding out if Johnny can, and will, actually change or if he's just trying to manipulate me, discovering how my decisions alter the way he interacts with me, and going down a rabbit-hole, sex trafficking narrative that initially feels a bit too archetypical, only to have it morph into a multi-part story that rooted V's narrative in an emotional and impactful way.

These are the stories that you can actually, meaningfully change. And because I did them all before the main storyline, they all felt like they meshed well with my V’s overall story.

Of course, you could do the main story right away and then go back and do these side stories. I think the experience would be quite different because of the knowledge and relationship you have with Johnny at the end of the main story experience, though.

The main storyline has multiple endings; I've experienced four of them, and they all deliver fairly well on expectations. These endings do not consider anything that isn’t a main or side job, which is labeled as such in your log. Your relationships with the main characters do change the endings slightly, but they don't change the overall outcomes for V and Johnny. This made the game's main attraction for me the fleshed-out side narratives and a few other mysterious side jobs that crop up without a fixer giving them to you.

These other stories were more enjoyable because I felt like I really mattered and could actually mess them up. The main storyline is only preoccupied with whether or not you did X and, if so, you can see the Y ending. It felt like it had lower stakes.

Conclusion

I do feel like 2077 is a new way to consume an immersive role-playing video game experience. It's unfortunate and unfair to many people that multiple promises the game makes cannot be fulfilled unless they can experience it on a particular platform (with a fairly sizeable amount of money in the investment). A decent computer to play it on is the best way, and it’s expensive if you want to max out absolutely everything. Next-generation consoles aren't even optimized for it yet. Last generation consoles are struggling. Crashes, bugs, poor textures, and framerates.

What is Cyberpunk 2077 when it can’t replicate the ideal delivery for its desired experience?

So much of what made the experience singular and noteworthy for me comes down to how life-like and human the people I came to care about the most in the game looked and acted. Take that veneer away, and the cracks in the façade appear.

Doing most of the side content before the main jobs gave my V a meta-narrative: they were a ruthless killer that would do pretty much whatever a fixer asked of them. Those were the expectations set by the world outside of the story. But then V morphs into a person confronting that life, questions who they want to be, and what it takes to thrive in Night City when you hit the main narratives. That’s why I had a positive experience. And that’s why I’ll return to the city and do things differently.

Ironically, Cyberpunk 2077's overall game experience relies on technology to build empathy between the player and the main cast. Yet, the world outside of the main narrative denies that same empathy to the denizens and factions it populates Night City with. If the platform you’re playing on can’t effectively utilize the demanding Red Engine developed for Cyberpunk 2077, the most likely outcome is an experience devoid of the only substantive thing it has to offer.

A quick thank-you to the anonymous person who requested a review, along with the money to purchase the game, and to Darren, for helping me with edits and feedback.

February 26, 2020

User Error Is The Undercover Through-line You Never Knew The Glitch Logs Needed

The third installment of The Glitch Logs, User Error, sees Glitch strapped for cash after her decision in the previous novel, Overclocked. Rather than laying low after surviving a series of unfortunate events, she has little choice but to take on a suspiciously well-paying job from her fixer to recoup her losses. Glitch has to go undercover at an elite university, providing cyber expertise in an ostensibly simple op centered on a student who ends up being more than what she seems.

After a fast-paced, thriller-like structure in the previous books, User Error could be a downbeat in this mixtape, allowing some breathing room to characterize further and flesh out Glitch by way of expanding on things briefly eluded to in previous novels.

One of the favorite things about this series is the author making pretty much every detail important.

I reread the previous books before starting User Error because I was all but certain past events would be expounded upon in the new book. I was pleasantly surprised when a small part of the first book comes back in a big way, even as the plot of the second book spirals into User Error. It is incredibly satisfying as a reader, knowing that everything you’re reading is pertinent and serves to both characterize and facilitate the plot.

After seeing a piece of the corporate world and, later, the underworld—the switch up to an undercover job at a prep school allows for some social commentary as the stratification of class situates Glitch and the other characters in the story. How, and why, Glitch chose to be a runner is nicely brought together here. It’s also just fun that the school ends up being as dangerous as the corporate job. Glitch is out of her comfort zone and element, leading to some great, humanizing moments for the character so far.

As with the previous Glitch Logs, User Error expands the world, pulls back a bit more of the mystery surrounding Glitch’s past, and ends with more interesting questions than the reader arrived with. There are more fantastic hacking sequences with well-realized imagery, something the author also excels at—and more action sequences too. User Error delivers what was well-liked and worked well, and then expands on it and deepens the protagonist. She’s fallible, human, and best of all, you can see the through-line of how she comes to be this way from her past catching up to her.

You can purchase User Error here: https://www.glitchlogs.com/product/glitch-logs-user-error/

January 30, 2020

Why You Should Read Infomocracy & Null States (Of The Centenal Cycle)

“…despite all the Information available, people tend to look at what they want to see.”

Infomocracy and Null States, the first two books in the Centenal Cycle series by Malka Older, could be the scariest post-cyberpunk series I’ve read. In it, micro-democracy has proliferated across the globe. The governments of choice being, for the most part, megacorporations. Borders have shifted and changed in the world, reflecting a physical change reflecting how much of society operates on social media today: curating their spaces to consolidate people with the same (among other things) ideologies.

When the borders settled, groups of 100,000 people—called a centenal—vote in the corporation of their choice using another megacorporation-like system, aptly called Information. The ‘corp that gets the most votes, netting the “supermajority,” wins the global election as though it were a federal election, except that it’s global. Otherwise, the granular control of a centenal is left to the ‘corp voted in.

This is, of course, a very reductive explanation of the system.

One of the strengths in both Infomocracy and Null States is Malka’s attention to detail. This system of governance, as well as every facet of the fiction in fact, all feel incredibly well-realized and researched. Infomocracy can feel overwhelming in that regard sometimes. It is so unlike anything I have written that the text needs to do a lot of heavy lifting, communicating, and breaking down complex philosophy, politics, and other interlocking systems that are integral to understanding the world.

“Systems include their by-products; it all comes from the pattern of incentives they create. It’s how they make people think, how they make people behave.”

This is why both books were, in a way, incredibly terrifying to me. Malka spends time on all details, both small and large, such that it becomes impossible not to trace the reasoning behind micro-democracy evolving from society as we know it. Part of why it is so believable is that “democracy,” at least, as it is practiced currently, feels like it’s short-lived. At the same time, the idea that corporations will end up being in control seems correct to me. The world envisioned in the fiction then, in no small part due to micro-democracy, ends up conjuring a mixture of emotions. But, strangely, micro-democracy coupled with corporations is…optimistic in many ways, too. This different application of democracy which caters to the realities we are facing currently, becomes eerie in its inevitability.

Infomocracy does this while also threading a globe-trotting, thriller type conspiracy that unfolds within the now well-established micro-democracy system the reader is learning about. It ends up feeling a bit like a techno-thriller paired with political intrigue. The cracks in the system are beginning to be exploited, a powder-keg situation unraveling as it bounces from perspective to perspective.

While the thriller aspect to the book felt well done to me, the problem I encountered was that the world being communicated to me far outstripped the thriller plot unfolding, in terms of my interest. To the point where it felt, to me, like a sub-plot. I’m not sure how you fix that when you have to hold the reader’s hand explaining the setting. There are futuristic technologies involved as well, expounding the information that needs to be conveyed. Almost everything about an average person’s life experience in the setting is altered from today, a tremendous undertaking.

However, Null States does not have this problem. With much of the world established, it hits the ground running. An Information agent is assigned to a suspicious investigation in which a governor has died. During the course of their inquiry, the fiction feels more grounded than Infomocracy had. A globalized plot is still presents, stemming from the initial events and works to tie together a couple other predominate characters, all of whom are relevant to the events of the first book. This shift from having to explain the world to a more consistent human perspective—including some characters that expose the problems within the system—made for a more exciting plot. It springboards off the first novel wonderfully to create a richer, more rewarding experience in just about every way.

‘minimally traceable,” Shamus corrected him; “nothing is one hundred percent untraceable”—to Policy1st.’

Reflecting on both of these books, there are a few things my mind consistently wanders to regarding my consumption of the Centenal Cycle so far:

I think most often, I find myself a little bit awed at how deep the investment in the setting feels to me, most notably in micro-democracy itself as a sort-of living experiment, but the same can be said for each aspect of the setting, I think. The attention to detail is astounding sometimes. Especially because these details actively work to expose the flaws and vulnerabilities. Showcasing them quite predominately at times.

It feels like some kind of active exercise in what the spirit of critique is. Something rarely experienced in this day of age in social media. To display such affection and then examine it, interrogating something you’ve created—feels like something rare and genuine and novel, especially in cyberpunk/post-cyberpunk fiction. There is a sense that Malka is willing to burn it down, if that is where the experiment leads.

“…those may be exactly the people who pose the greatest threat to the system: the people who can still remember, with rancor and longing and the inevitable distortions of time, what things were like before.”

The characters all feel well-realized and often break tropes or archetypes. They are also intersectional and people of colour. On Malka’s Twitter, her pinned tweet is this: “I write for the people whose names get underlined in red by Microsoft Word”. I think that’s as apt and succinct as you can be about how the fiction feels. There is a starkly contrasted difference between the marginalized and the privileged. The numerous points of view produced in the fiction are as diverse as you’d expect them to be in the future. All the pitfalls of punk and punk-adjacent fiction are not present, either.

When it is all placed together, I think what I’ve read in these two books is the most interesting and progressive piece of post-cyberpunk fiction. It is aware, sharp, and incredibly smart. It is easy to imagine these books as formative works for people working in the genre going forward. And I can’t wait to find out how it ends.

“…democracy is of limited usefulness when there are no good choices, or when the good choices become bad as soon as you’ve chosen them, or when all the Information access in the world can’t make people use it.”

December 5, 2019

Neon Wasteland Augments Your Reading Experience

Neon Wasteland #1

Chances are if you’re a part of any cyberpunk groups—be them on Reddit or Facebook, or other social media—you’ve seen some art by Rob Shields. His work is both gorgeous and distinctive. So a cyberpunk comic book filled with his art would be cause for celebration. An augmented reality comic? Heck yeah.

The artwork is inspired by 1980’s Japanese cyberpunk animation and the story is described as being Mad Max meets the Matrix on the Kickstarter page.

“Putting the Punk Back in Cyberpunk

At its core, Neon Wasteland is a satire about the world we live in, the real power and danger that we continue to uncover through technology and the seductive pull of artificial reality. It’s about the constant struggle between our physical and digital identities and the value of human connection in a society where we seem to be increasingly alienated.”

You should see this panel using the augmented reality app.

At first, I wasn’t sure how much I was going to like the AR experience. You use an app on your phone and then it animates on your screen; very simple instructions. I was blown away by how fun it was to read like this. When going through the spreads on my laptop, I laughed and giggled and was honestly floored by the detail of the animations and the effect it had on the overall experience. It feels new and just, well, fun as hell. It really does feel like a wild, over-the-top anime. It has clear themes, a one-of-a-kind aesthetic paired with a one-of-a-kind experience. There are some extremely cool augmented panels.

The first issue is about half the size of a trade and came as double page spreads, which fit how the phone app wants you to view the game. But you can still hold your phone in portrait and go one page spread to one page spread, if you like as well. I don’t want to go into the story too much, simply because with a first issue of a comic, what it’s about is often what #1 establishes. I’ll be picking up any future issues that might come out for sure.

Grab your own copy of Neon Wasteland #1 here: https://neonwasteland.bigcartel.com/

October 8, 2019

Systemic Trauma In Slow River

“She could become anyone she wishes. But how will she know she is still herself?”

More than anything, Slow River is, at least to me, about trauma. It is explicit in its focus on abuse and trauma, but I didn’t find it graphic in its depictions “on-screen.” Even still, it is a heavy and it makes it more difficult to talk about for me, since my reviews are usually what I enjoyed and found novel about whatever it is I’m consuming. There’s child abusive, emotional, physical, sexual abuse. It is supposed to be disturbing, so it is not for everybody.

Published in 1995, Slow River tells the story of a young woman named Lore, who comes from a wealthy family who made their money and renown creating cutting-edge sewage reclamation plants. That life, however, comes crashing down when she’s kidnapped and ransomed. Her family doesn’t pay, Lore escapes her abductors, goes off the grid, and enters a criminal underground via Spanner, a grifter who’s willing to help her—so long as Lore pays her back, however she can.

The story alternates between Lore’s past and her present. When she gets out of the dark and seedy underbelly that is this underground and begins working at a plant owned by her very own former family. And her life before her decision to move on, recapping the events with Spanner, which rapidly becomes disturbing as they showcase what the marginalized need to do to get continue to get by, as well as the various coping mechanisms utilized to disassociate from the things done.

The business carries your name. You’re responsible.

Lore comes from a life of privilege but, interestingly, the amount of focus on both of these worlds took me by surprise. Her family and her loved ones in the past are revealed to be as monstrous, if not more at times, than the slums everybody fears in that world, and where she ends up. So much so that when she does get free of her captors—she doesn’t choose to go home to them. This time Lore spends recounting these events seem like her attempt at making sense of a decision that doesn’t seem to make any sense. She’s processing what happened in a dissociative state because she needs to understand why she so adamantly refuses to go back.

“You’re too damn.. glossy. Like a racehorse. Look at your eyes, and your teeth. They’re perfect. And your skin: not a single pimple and no scars. Everything’s symmetrical. You’re bursting with health. Go out in the neighborhood, even in rags, and you’ll shine like a lighthouse.”

Spanner doesn’t understand why she’d stay. At any point, she can return home…which ultimately means that, to Spanner, she doesn’t embody the streets as she does. When Lore and Spanner’s relationship shifts from being complete strangers helping each other for mutual, temporary benefits, to something romantic. It begins to unravel them both—creating a sense of tension and unease that paces with the story well because of the alternating structure of past and present until they collide and you finally figure things out at the same time Lore does.

It is also surprisingly in-depth and thorough about water reclamation and other technologies, like digital currency and invasion of privacy technology and things like that. I wasn’t sure if this water reclamation technology actually exists or if it was completely hypothetical. Whatever the case may be, it certainly seemed completely believable to me, authentic or not. And that believability induced an element of horror. The problem of polluted water, and the fact that we’re going to have significant issues with water in a few generations, become both solvable and instantly already commodified. A simple solution for some, yet not available to everybody.

“All Lore understood about Spanner was that whenever Lore reached for her, she wavered and was gone, like the shimmering reflection on the oily surface of the river.”

That credibility permeates every other facet of the story, augmenting and accenting the terrible and the very human, kind moments punctuating the character interactions.

It becomes clear with these interactions that anybody of substance in the fiction carries some kind of trauma, and it is all rooted in systemic issues. What is so different and so captivating about this is—even if it’s never a “fun” story to read—that it points the finger at capitalism in a way that is so brutal; so messy and bloody and bare, that everything is always focused on this overall larger picture; rather than typical cyberpunk, which encases some of these same thoughts in a far more different style. This is not sex, drugs, and rock and roll. There are no mirrorshades and trench coats and futuristic weapons. It discards the trappings entirely.

I liked that about it because I found it to be very honest fiction that seemed very personal. The fiction is pretty clear that this system, capitalism, that we trust for no good reason—hurts us and traumatizes us, and it’s absurd and mean and unfair. These things are far too real in the fiction and thus it refuses to make them vehicles for catharsis or power fantasies. It’s just not going to be that kind of story and you find that out from page one. The future becomes much more profoundly upsetting when the predators are shown to be manufactured by a system that manufactures trauma, and is far from being reclaimed.

“Spanner said, without looking up from the screen: ‘I’ll see you again. You’ll always need me.’”

August 27, 2019

He, She, & It Underscores The Importance Of The Masculine And The Feminine Coexisting

“No one born now will experience the world of gentle air we could walk through on impulse, without protection, winds and rain that caressed our skin, deep thick woods, grass like green hair growing thick from the moist earth. We were killing the world, but it was not yet dead.”

It is no surprise that at the end of He, She & It, the author, Marge Piercy, acknowledges A Cyborg Manifesto. Written by Donna Haraway in 1985, is critical of traditional notions of feminism and hoped to empower writers to move past the conventional notions of gender, among other things. Never had this manifesto been more taken to heart and explored by an author until He, She, & It.

Shira lives in a corporate city with rigid structures and rules that stamp out that systemically gaslight her on every front of her life. Her work is undervalued on purpose. Divorce procedures for her and her husband favor him. In an act of contempt and malice, he takes their son. Left with nothing, Shira goes home to her mother and town entrenched in traditional Jewish to face old relationships and old pain she has been running from all her life.

“Information shouldn’t be a commodity. That’s obscene. Information plus theology plus political bias is how we sculpt our view of reality.”

At the same time, a cyborg, a man, is created in the town Tikvah she now goes back to, and her grandmother, Malkah, who raised Shira, helps to program Yod. Where other cyborgs crafted by a brilliant scientist have gone mad and failed, Yod seems to thrive because of the genius programming of Malkah; which instills femininity in the cyborg, bringing a balance to the programming.

As Yod is discovering himself for the first time and Shira is rediscovering herself in her roots, another story unravels: an old story, told by Malkah in the form of a story left for Yod in the town’s network (this books version of cyberspace). The story is of a rabbi in the 1600s living in Prague who has conceived of creating a golem that would protect the Jews from their oppressors. When Joseph is created, however, it becomes clear that he possesses a mind and a will. One which is constrained in the same manner as the ghetto limits the Jews who live there.

“I cannot always distinguish between myth and reality, because myth forms reality and we act out what we think we are’ we know on many levels truths that are irrational as well as reasoned or experimental. Our minds help create the world we think we inhabit.”

This story parallels the main story and has elements of Jewish folklore and cultural history that is both fascinating and works very well to show technology in this future world as a kind of foil for the unknown. As well as how the unknown is always dealt with. In the past and the future, the golem and cyborg encounter similar problems and similar growth that further lends context that becomes pertinent when the question of both man’s humanity.

Shira struggles with being a tool for the corporation as it becomes clear that her losing her son and her choice to return home may be a part of a larger game of factions. Yod struggles with being designed as a tool and a weapon when he views himself as a man, and it becomes clear to anyone that chooses to interact with him that as he learns, much like a child, it is not his functions that define him, but almost everything but them. And this same struggle is mirrored in the past with Joseph, of course. Which creates a growing tension in both stories.

“Everything felt…unregulated. How unstimulated her senses had been all those Y-S years. How cold and inert that corporate Shira seemed as she felt herself loosening.”

As both stories unravel, the characters embody the author's exploration of feminist ideas that are at the most interesting in Yod. The only reason Yod can have a steady mind at all is because Malkah has imprinted into him what a mother might. Where other models solely possessed the scientist’s objectives and personality that was ideal for their being able to protect the town and be an effective weapon, the humanity of the very thing he creates never occurs to him.

“A weapon should not be conscious. A Weapon should not have the capacity to suffer for what it does, to regret, to feel guilt…”

Nor would does it seem to in the case of Joseph. There is a horror in realizing that neither creator understands the importance of the femininity in a person. They appear blind when they look inward to themselves, unable to reach the self-awareness that the interactions they most cherish stem from interactions with their family; particularly the women in their lives, and how they soften from their self-destructive attitudes around them. Yet they choose to create another being and bind the person to themselves only. Where their children are given over to their mothers in other to be made proper men. Their inventions relegated to their task and work; their humanity continually denied. Is it any wonder that the cyborgs before Yod; before Malkah went mad?

“…an artificial person created as a tool is a painful contradiction.”

The women in the story do not exist only to embody these qualities and illicit this exploration. They all struggle themselves with their own notions of femininity. Shira with the cultural reprogramming from living in corporate society for so long. Malkah is almost the opposite of her, dwelling in masculine qualities and taking pride in going against the grain in her keen sense of sexuality that is predominate in every relationship she has ever formed. Each intuitively knows that a person needs masculine and feminine qualities. Or else be lost.

This exploration for the sense of self is never-ending, exemplified in the stories of the multi-generational, globally spanning women of the family; but also in every character. Cyberspace, a place for the mind to express its creativity, particularly in the case of problem-solving. Is similarly different from more masculine cyberpunk works. It is merely a medium, the inherent technophobia is not present at all. The thing to fear most, and fear you should, in He, She & It is always man and the systemic problems that comes with them. As long as the systems that run our lives embody the masculine, we are all doomed to a madness that serves only the creators.

“Men so often try to be inhumanly powerful, efficient, unfeeling, to perform like a machine, it is ironic to watch a machine striving to be a male.”

August 14, 2019

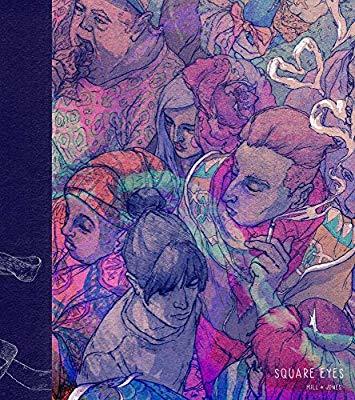

Square Eyes Is A User Interface Experience Unlike Any Other

Square Eyes features an interesting plot revolving around a woman named Fin who wakes up unsure of who she is after being unplugged from the network. She finds a woman seemingly living her life and slowly unravels a larger mystery about a program she was developing with enormous implications for basically everybody. That in itself would be enough to give it a read, in my opinion.

What is makes this graphic novel more compelling is the presentation. I have never seen futuristic, augmented reality better realized than in Square Eyes. The interface unfolds in intuitive ways, growing more complex as the story goes on and Fin begins to recall more and more of her past. It’s beautiful from a user interface standpoint but presenting the UI in tandem with the story makes for an intelligent and compelling experience; as a UI should be!

Additionally, every page; every spread feels carefully orchestrated to communicate details about the world. They are chock-full of them. It’s easy to get lost in pages roaming around spreads looking at details. This exploration is made even more satisfying due to the physical product itself, which is printed on nice, thick stock that lends even more substance to each page.

It’s a visual and physical feast that sets it apart. Other reviews, I have noticed, downplayed the plot; perhaps because the presentation is so incredible, the plot naturally takes a back seat for some. But I feel like what Square Eyes has to say about the world is prescient, especially regarding information being the number one commodity. Subtly reinforced throughout the reading experience, it can sometimes feel like the plot is shallow because it’s communicated all the time, presenting itself eerily within the world at all times.

With hindsight we now have regarding Cambridge Analytica’s role in various elections, and multiple other campaigns, the parts of the story where Fin feels disconnected from the world around her due to her being unplugged from the network seems like it might only days away for everyone. Our online experience is a curated bubble. But when everyone is in that bubble and you’re out of it, even when you’re attempting to interact with everyone physically, it’s a different kind of disconnect. Within this fiction, everyone is negotiating their own world in a more literal way due to the network. Their overlays are a far more curated experience that omits people even when they are right there with you.

Notions around forms of online piracy and the ways they might intersect with social class throughout, illustrated further by the interface that blooms from Fin’s own hands, make for an accessible and empathetic approach to communicate technological anxieties that feel new and fresh. Anyone can understand this because of the physicality of everything to do with the product. It’s as real as your hands pressing the next, thick page aside to make room for the next, and that’s a unique, cyberpunk story only available through Square Eyes.

July 23, 2019

Salt Fish Girl Intersects Genres, Gender, And Culture

“This is a story about stink, after all, a story about rot, about how life grows out of the most fetid-smelling places”

Salt Fish Girl is no ordinary offering; in fact, it is very clearly cyberpunk, specifically biopunk. It’s also, in part, magical realism—as it interweaves mythological components. This intersectionality in terms of genre makes for a uniquely fascinating contribution to the cyberpunk sub-genre.

“I was a sheltered child, living out my parents’ utopian dream as though it were reality. They did not show me the cracks. And out of loyalty and love for them, when I sensed the cracks, I refused to see them. But of course this unspoken pact could not last.”

Miranda grows up in a futuristic Canada that is dominated by corporations while struggling with being a minority. On top of her not being around people from her own culture, she also is born with a strange smell, reminiscent of “cat piss” that seems to wean as she gets older but results in an isolating and challenging childhood.

“I was a sheltered child, living out my parents’ utopian dream as though it were reality. They did not show me the cracks. And out of loyalty and love for them, when I sensed the cracks, I refused to see them. But of course this unspoken pact could not last.”

Paralleling Miranda’s story is one of Nu Wa, a creation story of a Chinese goddess who births humankind and eventually chooses to become one, born as Nu Wa. Similarly to Miranda, Nu Wa’s experience is one of poverty and classism that allows for her exploitation. These two stories elegantly depict complex systemic issues, such as stratification of class that transcends generations.

“When you own nothing, it’s hard to believe you have anything to lose. I can’t say what it was that made me follow the strange woman, except that it took more weakness than strength.”

Nu Wa and Miranda are both taken advantage of by people in a higher class, using their poverty to co-opt their intellectual property and personhood. For Miranda’s family to navigate society more easily, her father tries to trace the source of a rumor that Miranda’s smell is curable. Corporations are also mass-producing human clones as a source of cheap labor, it appears that biotechnologies, both sanctioned and unsanctioned by these corporations, is more pervasive than people are aware. As more and more people seem to be contracting something dubbed the “dreaming disease”—which appears to unlock generational memories—people are committing suicide and disappearing. And Miranda is beginning to remember some things herself.

“Why shed blood when people can be brought and sold so easily?”

The story is steeped with culture and the cultural issues that come along with them. From the different smell of other ethnicities cause ostracization to family dynamics and the very particular ways the corporations leverage the marginalization of the main characters. A fringe benefit of this authenticity is how the cyberpunk motifs resonate much more profoundly.

“What is the point of honour if it is always used against you?”

July 16, 2019

Tea From An Empty Cup Examines Problematic Aspects Of First Wave Cyberpunk

“You people, you lost your souls a long time ago, you sold them for a good parking space.”

Published in 1998, Tea from an Empty Cup is one of the later cyberpunk books from Pat Cadigan. Revolving around a mystery in which a person is killed, perhaps murdered, while in a virtual reality rig that just so happens to be located in a locked room, the book appears more straight forward than it actually is. This death is a catalyst for two people to enter the same program in cyberspace that eventually intersect. One is a detective attempting to solve the mysterious death, the other set to find a someone who’s suddenly gone missing.

Embodiment is put into focus and takes on a different shape, so to speak, than previous Pat Cadigan books. People put on a suit of varying quality derived by the number of contact points on the body in the suit, which allows for a more “real” experience. Previous books generally explore memories and mind-to-mind technologies, so this is quite different than other books. An entirely different focus.

“Doesn’t mean Japan is dead. It just means everyone’s left the geographical coordinates that once marked the location of the country that was called Japan. It doesn’t mean there isn’t a Japan. Somewhere”

In this world, earthquakes destroyed Japan and one of the most trafficked simulated environments, and where the majority of the story takes place, is New Yawk Sitty. The novel weaves in a theme of fetishization of Japanese people; a problem that first wave cyberpunk novels were academically criticized for. Whereas most of first wave novels were xenophobic and technophobic due to the anxiety surrounding Japan possibly becoming a technological superpower that would consume the west, this novel flips that notion on its head, showing that the culture that ended up being consumed was Japan by the west.

In this future, there remaining Japanese people are seemingly struggling to hold onto their identity and given a certain amount of social credit if they are “full Japanese.” I’ll note here that whether or not the handling of the cultural aspects of the plot and setting are handled well, I really couldn’t say, as I’m not educated in it enough to talk intelligently about it. But it did feel like a prevalent theme given proper weight.

The grit present in cyberpunk is certainly present online, but some of the navigation of cyberspace is a bit dated reading it today. Avatars and cultural touchstones have shifted nowadays, but where it shines is in displaying how people behave when afforded anonymity. It is prescient. This ability for people to customize their presentation and construct an alternate world, as well as what that would reflects in the real world proper, are all compelling and seem more progressive than previous novels by the author. Or perhaps are just more overtly so? Though, some of the original power of the text is most likely diminished because much of the technical aspects have already played out, whereas here it is supposition and exploration.

“No age given; under sex it said, Any; all; why do you care?”

As it is now, the mystery itself is interesting and drives the story reasonably well, and the commentary and exploration on the fetishization of marginalized groups and the seemingly inevitable recreation of violent colonialism playing out in the new digital frontier are the most compelling aspects in this relatively short and fast-paced story.

“A.R is humanity’s true destiny. In A.R, everyone is immortal.

If you don’t mind existing solely in reruns.”