Michelle Cooper's Blog

April 13, 2025

Miscellaneous Memoranda

An anonymous author of children’s literature tells it how it is at The Bookseller:

“This whole business is founded on the desperation of children’s authors to be published and then their willingness to put up with terrible pay, because they want to be published again…This allows publishers to pay us a pittance, but it’s okay, because we will make up the difference in school visits. The publishers expect it. They even arrange free ones for us, hoping that we will learn on the job and convert that into an income stream.

But it’s exhausting […] Above all, it is not fun. For many of us, the physical and mental toll of turning up and performing can be debilitating. And that’s if we can even do it. Giving up your day job to visit schools isn’t easy, nor is parking your own children or dealing with health issues on the road. Some of us feel massively unconfident about it. We are writers, not performers. We are not teachers either, and yet find ourselves running workshops for keen and unkeen young writers.”

Also, publishers prefer to publish children’s books ‘written’ by celebrities and most of these books are terrible. But not all of them! Here Emily Gould rates the best celebrity children’s books at The Cut.

Not that things are much better for those who write for adults, as Kate Dwyer explains in Has It Ever Been Harder To Make a Living As An Author?:

“Without any other revenue streams, it’s highly unlikely that someone could make ends meet or support a family by writing novels. Most novelists have day jobs, and the majority of those who don’t are either independently wealthy or juggling a handful of projects at once, often in different mediums like film, journalism, and audio.”

But here’s some advice on how to deal with the depressing life of an author. Ask Polly consoles an author who’s devastated that her book barely sold:

“Blaming yourself for not selling books is like blaming yourself for aging. It’s irrational. Books don’t sell, period. Have you ever skimmed the best seller list? If a book is truly great, it’s almost guaranteed not to sell. You’re calling yourself a failure for things that are out of your control […]

But listen to me: You write because you believe in it. You still believe, even now. You crave love, and that part of you isn’t humiliating. It’s sad and pure and true. It’s a gift. So stop telling yourself lies and repeating this world’s bad noises. No one smart measures quality on sales. No one enlightened reduces art to commerce.”

To be an author, you need to be intelligent, creative and resilient. You need to be stubborn. You must never give up on your goals.

You need to be Stoffel the honey badger:

March 21, 2025

Author Alert: Has Your Work Been Used To Train Meta’s AI?

From The Australian Society of Authors:

Today The Atlantic published a search tool allowing authors to search for their books in the LibGen dataset, which has been used to train Meta’s AI system. The ASA is horrified to see that Australian authors’ books have been included in this pirate database.

(By the way, this was posted on the ASA’s Meta-owned Instagram account.)

From the US Authors Guild:

Meta and other AI companies knew exactly what they were doing but they did it anyway. Why? Because they needed books for their quality writing, style, expression, and long-form narration and would rather steal them than ask and pay for them as they do for all of the other necessary components of their AI, such as electricity and programming.

From the UK Society of Authors:

The Atlantic says that court documents show that staff at Meta discussed licensing books and research papers lawfully but instead chose to use stolen work because it was faster and cheaper. Given that Meta Platforms, Inc, the parent company of Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, has a market capitalisation of £1.147 trillion, this is appalling behaviour.

Six editions of my own books are on the list of pirated books that was used to train Meta’s AI program. As if it isn’t bad enough that my books are constantly pirated, Meta is now taking authors’ work for their own commercial gain, without asking for permission from the authors or paying the authors or publishers.

If you’re an Australian author, you can check if your books are on the pirated LibGen list here and you can inform the ASA about this using this form.

US authors are automatically included in a class action against Meta and you can find out more here. UK authors can find more information here.

Authors, publishers and readers – if you use Facebook, Instagram, Threads or WhatsApp, you’re supporting Meta and its CEO Mark Zuckerberg. If the Cambridge Analytica scandal wasn’t enough, Meta also announced in January this year that it would no longer use professional fact checkers on its social media platforms.

February 11, 2025

What I’ve Been Reading

The Secret to Superhuman Strength is Alison Bechdel’s latest graphic memoir. It’s a characteristically funny, thought-provoking read, but also makes me very glad I’m not Alison Bechdel’s friend, relative or partner because she splatters everything on the page. It’s probably small consolation to them that she’s even harder on herself than she is on everyone else. This memoir, her third, is about her obsession with exercise—skiing, cycling, strength training, running, yoga, karate and trying out every exercise fad since the 1980s. Her focus on a healthy body does not prevent her from abusing alcohol, recreational drugs and prescription drugs, and having the worst sleep habits ever, just as her desire for secure love does not stop her incessant chasing after unsuitable women, even when she’s already in a relationship. She attempts therapy of various kinds, investigates Buddhism, and seeks wisdom in the lives and works of Kerouac, the Wordsworths, Shelley, Coleridge, Emerson and Margaret Fuller, until she finally realises:

The Secret to Superhuman Strength is Alison Bechdel’s latest graphic memoir. It’s a characteristically funny, thought-provoking read, but also makes me very glad I’m not Alison Bechdel’s friend, relative or partner because she splatters everything on the page. It’s probably small consolation to them that she’s even harder on herself than she is on everyone else. This memoir, her third, is about her obsession with exercise—skiing, cycling, strength training, running, yoga, karate and trying out every exercise fad since the 1980s. Her focus on a healthy body does not prevent her from abusing alcohol, recreational drugs and prescription drugs, and having the worst sleep habits ever, just as her desire for secure love does not stop her incessant chasing after unsuitable women, even when she’s already in a relationship. She attempts therapy of various kinds, investigates Buddhism, and seeks wisdom in the lives and works of Kerouac, the Wordsworths, Shelley, Coleridge, Emerson and Margaret Fuller, until she finally realises:

“that you can’t repress pain and still expect to feel pleasure. And that feeling pain compared with the gray dread of avoiding it, was actually almost a kind of joy. In fact, joy was only possible because one’s existence—all this!—was going to end. What a tedious slog life would be without death!”

I also really liked The War of Nerves: Inside the Cold War Mind by Martin Sixsmith. It uses psychological analyses of Cold War leaders, from Churchill and Stalin to Reagan, Thatcher and Gorbachev, as well as whole-population studies, to examine how the fear, tension and paranoia in both East and West changed world history. The author studied Russian and psychology in the UK, US and USSR, and worked as a journalist in Moscow at the end of the Cold War, so his perspective is well-informed and fascinating. The edition I read was published in 2021, before Putin invaded Ukraine, so it would be interesting to read an updated edition (although I now see that he published a book last year about Putin).

I also really liked The War of Nerves: Inside the Cold War Mind by Martin Sixsmith. It uses psychological analyses of Cold War leaders, from Churchill and Stalin to Reagan, Thatcher and Gorbachev, as well as whole-population studies, to examine how the fear, tension and paranoia in both East and West changed world history. The author studied Russian and psychology in the UK, US and USSR, and worked as a journalist in Moscow at the end of the Cold War, so his perspective is well-informed and fascinating. The edition I read was published in 2021, before Putin invaded Ukraine, so it would be interesting to read an updated edition (although I now see that he published a book last year about Putin).

I know everyone has already read The Thursday Murder Club by Richard Osman, but I avoided it because something that popular written by a television celebrity would have to be bad, right? I was wrong. It’s a clever and very amusing mystery set in a retirement village, in which four elderly residents solve crimes with the reluctant help of a depressed detective inspector and his cheery sidekick. The plot does go completely off the rails towards the end, with three unconnected murders getting solved, several deaths, a Murder Club member reuniting with her estranged daughter, and the depressed detective gaining a girlfriend. There were just too many characters, too many red herrings, and not enough space devoted to the four main characters, who were all fascinating and funny.

I know everyone has already read The Thursday Murder Club by Richard Osman, but I avoided it because something that popular written by a television celebrity would have to be bad, right? I was wrong. It’s a clever and very amusing mystery set in a retirement village, in which four elderly residents solve crimes with the reluctant help of a depressed detective inspector and his cheery sidekick. The plot does go completely off the rails towards the end, with three unconnected murders getting solved, several deaths, a Murder Club member reuniting with her estranged daughter, and the depressed detective gaining a girlfriend. There were just too many characters, too many red herrings, and not enough space devoted to the four main characters, who were all fascinating and funny.

I preferred the next book in the series, The Man Who Died Twice. The plot is still complex, but at least this time, the crimes are all linked and because they are related to the Secret Service past of enigmatic Elizabeth, the elaborate plot twists seem more plausible. There’s more attention paid this time to the relationships between the Murder Club members, which is very satisfying. Ibrahim is attacked and the others take revenge; Ron gets to act out his thuggish fantasies; Joyce’s narration is laugh-out-loud funny and her badly-knitted friendship bracelets become not only a running joke but an important clue. I’m looking forward to reading the other books in the series—although of course, there’s an enormous waiting list for them at the library. Apparently a film of the first book is being released this year.

January 21, 2025

Animals At War

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

The declaration of war in 1939 was heartbreaking for British pet owners, with hundreds of thousands of dogs and cats being put down. Pets were not allowed in public air raid shelters, and there were fears that there wouldn’t be enough food during the war for humans, let alone animals. However, many animals did their bit for the war effort.

For example, dogs were used to search bomb sites for buried victims, with seven dogs being awarded the Dickin Medal for ‘conspicuous gallantry or devotion to duty while serving in military conflict’. One of the most famous dogs in Britain was a St Bernard called Bamse, who was the mascot of the Free Norwegian forces stationed in Scotland. Bamse was an official crew member of a ship that managed to escape the Nazi invasion of Norway in 1940. While stationed in Scotland, Bamse rescued a Norwegian sailor who’d fallen overboard, and saved another from a knife-wielding assailant (by pushing the villain into the sea). The crew bought Bamse a bus pass, which hung around his neck, and he would take the bus into town by himself to round up any crew members who were late returning to the ship. Bamse would often have a bowl of beer with the men, and he was an enthusiastic goalkeeper and centre forward when they played football on deck. When he died of a heart attack in 1944, Scottish school children lined the streets to watch his funeral procession through the town of Montrose, where he was buried and where a statue of him stands today.

Horses also did their bit during the war, taking the place of tractors, delivery vans and cars after petrol rationing began. However, for the military, the most valuable animals were pigeons, who acted as messengers in circumstances when it was impossible to use radio communication. Thirty-two pigeons, including Commando, Winkie, G.I. Joe, Flying Dutchman, William of Orange, Gustav and Paddy, were awarded the Dickin Medal for their services during the Second World War (and you can watch pigeons Gustav and Paddy receive their medals here).

And that’s the end of my Inside a Dog posts! Before I return to my usual irregular Memoranda posts, here’s a set of links to all the Inside a Dog posts:

How To Write A Historical Novel In Seven Easy Steps

1. Think Up A Good Idea For A Story

2. Do Lots of Research

3. Get Organised

4. Write Lots of Words

5. Edit, Edit, Edit

6. Gaze Upon the Efforts of the Designer and Typesetter

7. Admire Your Finished Book

Planning vs Not Planning

Real People in Historical Fiction

Same Book, But Different

Keep Calm and Carry On

Looking Good in Wartime, Part One

Looking Good in Wartime, Part Two

Eating Well in Wartime

Blackout

Animals at War

January 20, 2025

Blackout

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

Even before war was officially declared, the British government banned anyone from showing any lights after sunset. This was meant to stop Nazi bomber planes from identifying targets on the ground. There were no street lights allowed. No illuminated advertising or shop signs. Cars, buses, trams, and even ambulances had to mask their headlights. You weren’t allowed to light a cigarette when you were outside. Only very dim lightbulbs were available (partly to save electricity), and every window, skylight and glass door in every house, apartment, factory and business had to be covered with heavy curtains before any indoor lights could be switched on. Often ordinary curtains weren’t thick enough, so people had to buy special blackout fabric and make new curtains. Not everyone could afford this, so some poor people had to paint or wallpaper over their windows, and they lived in darkness for the rest of the war. The rules were vigorously enforced by police and Air Raid Precautions wardens, who’d hammer on people’s doors and shout, ‘Put that light out!’ if the merest pinpoint of light was visible from the street.

Going out at night was very dangerous in the first months of the war, even though not a single German plane had been spotted. If you’ve ever gone for a walk during a power blackout, or in the depths of the country, you’ll know how it can feel, stumbling around in the pitch black. At first, pedestrians weren’t even allowed to carry torches, although after a while, this was permitted, provided the torch was aimed at the ground and was masked with two layers of paper. Not surprisingly, there were a lot of injuries. People fell down steps, onto roads and got run over by vehicles that loomed out of the darkness without any warning. Road fatalities doubled in the first months of the war. As one doctor pointed out, the Nazis managed to kill six hundred British people a month without even sending any bomber planes into the air.

There were a number of suggestions for coping with the blackout. People were advised to carry luminous walking sticks, untuck their white shirts, pin luminous flowers to their lapels or carry a white Pekinese. (It was recommended that the Pekinese wear a luminous dog collar and gleaming white blackout coat, plus a bell and a shiny identity disc.) (Note that the photo above was not actually taken during the war. It’s actually Alice Roosevelt, daughter of the US President, in about 1902. Also, if you want to get really picky, that isn’t a Pekinese she’s carrying, either. But I couldn’t find any photos of women walking around the streets of London during the war with their Pekineses, so sometimes, you just have to Make Do.)

A particularly annoying cartoon character called Billy Brown appeared on posters to give (rhyming) advice such as:

‘When Billy Brown goes out at night,

he wears or carries something white.

When Mrs Brown is in the blackout,

She likes to wear her old white mack out.

And Sally Brown straps round her shoulder

a natty plain white knick-knack holder.

The reason why they wear this white

is so they may be seen at night.’

Unfortunately, all these precautions didn’t help very much when the bombing started. The German bombers killed 50,000 British civilians during the Blitz. On moonlit nights, cities and towns were clearly visible from the air, and factory furnaces and lighthouses continued to burn brightly throughout the war. Besides, the Nazis had radar, and later they used pre-programmed robot bombs and rockets launched from the Continent. However, the blackout rules stayed in place until the final months of the war.

Next: Animals at War

January 19, 2025

Eating Well In Wartime

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

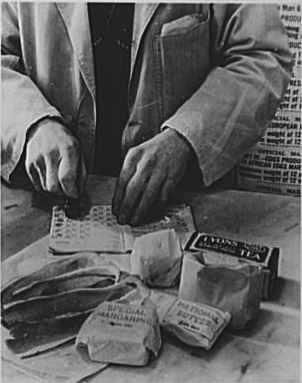

The British government was worried about the country running out of food during the war, so it brought in food rationing in January, 1940. Small amounts of sugar, meat, butter, bacon, tea and cheese were available each week, but only if you had the correct number of coupons in your ration book (the photograph below shows a week’s rations for one adult in 1943). Eggs, milk, fish and chicken weren’t rationed, but were in short supply. Later a points system came in, which allowed people to choose tinned meat, fish and beans, cereals, dried fruit, biscuits, lollies and canned puddings, based on the number of points they had saved. There were special allowances made for pregnant women, small children, vegetarians and those who had particular dietary requirements (for example, Jews and Muslims could exchange their bacon rations for cheese).

The Ministry of Food also provided information, in the form of recipe booklets, short films and a radio programme called The Kitchen Front to teach people how to cook creatively with such limited supplies. Recipes included ‘mock goose’ (made from potatoes, apples, cheese and vegetable stock), ‘mock apricot tart’ (potato pastry and carrots, with a few spoonfuls of plum jam) and ‘mock cream’ (margarine, milk powder and sugar). The most famous wartime recipe was for Woolton pie, named after the popular Minister of Food, Lord Woolton.

I did attempt to make a few of these wartime recipes myself. Carrot cookies were a success, but I was stumped by Spam. However, in recent times, some people have resolved to eat nothing but wartime food, either to lose weight or to save money or as part of a 1940s re-enactment. The Imperial War Museum in London also had a very popular exhibition in 2010, which included a café that sold meals based on wartime recipes.

Next: The Blackout

January 18, 2025

Looking Good In Wartime, Part Two

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

‘Looking beautiful is largely a duty,’ Vogue sternly informed young women during the war. Apparently, girls were meant to look as pretty as possible to cheer up their soldier boyfriends. Of course, girls might have wanted to look nice for themselves. Maybe they didn’t have enough coupons for a new dress, but some bright lipstick and a new hairstyle might help them forget the gloomy old war for a while.

The problem was that cosmetics were in short supply, just like everything else. Cosmetics companies such as Yardley’s and Cyclax had stopped making lipstick and perfume, so that they could concentrate on manufacturing sun protection creams and sea-water purifiers for the army. So, with no cosmetics in the shops, girls had to be creative. No mascara? Use shoe polish or burnt cork mixed with castor oil. No hand cream? Try rubbing lard or margarine or lemon juice into your hands. Perfume? Well, you might have to make do with lavender water. Unable to buy new stockings? Paint your legs with gravy powder mixed with water, then draw a ‘seam’ down the back of each leg with a pen.

Girls got creative with accessories, too. Everyone was meant to carry a gas mask at all times, in case the Germans dropped bombs filled with poison gas. Elizabeth Arden produced a special range of velvet-covered cases for gas masks, which included a silk pocket for cosmetics. When the poison gas attacks didn’t happen, people started ignoring the rules and left their gas masks at home – although some girls carried the empty case as a handbag.

Even hairstyles were affected by the war. Women in the services or working in factories needed to keep their hair up, out of the way. One popular style was the Victory Roll, an arrangement of curls held in place on top of the head with bobby pins. It got its name from either the V-shape of the hairstyle or in honour of the ‘victory rolls’ that fighter pilots would perform after an air battle. If you have long hair and would like to see how you look with a Victory Roll, here’s a handy how-to video from a modern-day girl who loves vintage fashions. Yes, I did attempt it myself. No, it wasn’t very successful, but then, I didn’t actually have any hairspray and I ran out of bobby pins. Anyone else have any success with it?

Next: Eating Well in Wartime

January 17, 2025

Looking Good In Wartime, Part One

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

It was a bit of a challenge, dressing well during the Second World War. To illustrate why, here’s an excerpt from an early draft of The FitzOsbornes at War:

“Julia and I went to a fashion show this morning, featuring the new official ‘Utility’ outfits. Of course, they are all very plain, to conserve both materials and labour – no more than three buttons per item, only one or two pleats, no lace trimmings or turned-back cuffs, no appliqué or embroidery, and the skirts are rather short, with hardly any hem. Still, they are beautifully cut and most importantly, new. I know I was lucky to own so many clothes when the war began, but some of them seem a bit schoolgirlish and old-fashioned now, and they’re all starting to look very shabby. There’s only so much one can do as far as re-dyeing fabrics and swapping buttons and letting down hems – sometimes a girl just longs to wear something crisp and bright and unfamiliar. So we all sat there at the show (in our baggy tweed suits and grey-seamed blouses), and practically salivated over the display. Just my luck I’ve recently had to use up eleven precious clothes coupons on new shoes and some socks, so I really can’t buy anything else for a while. But Julia said she’d found some lengths of curtain material, including a very pretty pale blue cotton, so she’s going to make me a short, plain summer frock from it. I’ll give her the pearl buttons from my old white blouse that had an unfortunate encounter with a leaky pen, and I’ll see if I can find a lace handkerchief for a little collar.”

German U-boats were sinking the ships that brought supplies to England, and any available materials were requisitioned by the military, so clothes for civilians were in short supply. As a result, the British government brought in clothes rationing. At first, everyone was allowed sixty-six coupons each year, although two years later, this had fallen to a mere forty coupons. You had to pay for the clothes as well as hand over the correct number of clothing coupons, and there were complicated rules about how many coupons were needed for each garment. For example, a woman’s woollen dress required eleven coupons, but a cotton dress only seven coupons. Women’s pyjamas needed eight coupons, but a nightdress only six. Shoes needed seven coupons, stockings needed two coupons and ankle socks needed only one coupon. Balls of knitting wool and lengths of fabric were also rationed. Some women made dresses out of sheets and furnishing fabrics, but soon even these were rationed, so the really creative types used torn parachutes (which were made from silk in those days), old blankets and pillowcases. Have a look at this Ministry of Supply film clip, part of the ‘Make Do and Mend’ campaign, to see how resourceful women were. [The photo above is of some volunteers from the Women of the University War Work Group in Brisbane, 1942.]

In 1943, the first ‘Utility’ clothes went on sale. The name wasn’t very appealing, but the clothes had been designed by famous fashion designers including Hardy Amies, Edward Molyneux, Norman Hartnell and Victor Stiebel, and the outfits turned out to be very popular.

Of course, some women were in uniform because they’d enrolled in the armed services or were working as nurses (the photo above shows three US Navy nurses in 1944). The Wrens (the British women’s navy) were especially popular with women, with some debutantes confessing that they’d only enrolled in it because the uniform was so glamorous. But then, other women, doing equally important war work in munitions factories, wore distinctly unglamorous blue overalls and cotton head scarves.

If you’re interested in 1940s fashions, check out this website, which is filled with pictures of everyday clothes, wedding dresses, hats, hairstyles and more.

Next: Looking Good in Wartime, Part Two

January 16, 2025

Keep Calm And Carry On

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

The FitzOsbornes at War is set (mostly) in England during the Second World War, and my characters get involved in all sorts of adventures. Sophie, my narrator, is dragged into a spy scandal at the American Embassy in London. Her cousin Veronica helps rescue a member of the British royal family from a kidnapping attempt. Her brother Toby becomes a fighter pilot and battles Nazis in the sky. Her friends Daniel and Rupert have top-secret jobs helping the military. Then Sophie has to investigate the circumstances surrounding a dear friend’s death when the authorities seem determined to hide the truth . . .

But you’re going to have to read the book if you want to find out more about that. What I’m going to write about here is how everyday life in England changed due to the war. Which is still pretty interesting, I think.

For example, during the Second World War, the British government had lots of information it needed to get across to the public. Often, it used posters to do this. There were posters reminding people to carry their identity cards and encouraging women to join the military services. There were posters asking people to donate their binoculars to the army or send money to the Red Cross. There were posters urging people to ‘Dig for Victory’ (that is, plant more vegetables) and warning them that ‘Careless Talk Costs Lives’ (because German spies might overhear vital information and use it to plan attacks). Most memorably, there were posters to boost the morale of the public, the most famous of which is probably this:

Ironically, this poster wasn’t widely distributed during the war. More than two million copies were printed, but they were designed to be displayed only if the Germans invaded Britain. Fortunately, this didn’t happen. So, most of the posters were destroyed after the war, but a few survived. The owners of Barter Books discovered one, displayed it in their shop and eventually started printing and selling the posters, which became very popular. Then came Keep Calm-o-Matic, a website that allowed you to create your own personalised versions. Naturally, I couldn’t resist creating some for the FitzOsbornes.

First, Sophie, who needs some encouragement to keep writing in her journal:

Then, her glamorous friend Julia:

And Julia’s brother Rupert, who loves animals:

And Carlos the Portuguese Water Dog:

There are more FitzOsbornes Keep Calm posters here.

What would your Keep Calm poster say?

Next: Looking Good in Wartime

January 15, 2025

Same Book, But Different

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

If you’re a Harry Potter fan, you’re probably aware that the first book in the series, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, was published as Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone in the United States. Apparently, the US publishers thought American children would be put off by the idea of reading about a philosopher. What you might not know is that the US publishers also made more than eighty changes to the story itself, which you can read about at the Harry Potter Lexicon. For example, ‘dustbin’ was translated as ‘trash can’, ‘jumper’ turned into ‘sweater’ and ‘lolly’ became ‘candy’. Some of the changes seem pretty silly to me – surely American readers can work out for themselves that ‘multi-storey car park’ means the same as ‘multilevel parking garage’. It was interesting to see that as the series progressed, the changes became fewer. By the final book, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, there were only a couple of vocabulary changes in the American edition (‘crib’ to ‘cot’, and ‘kitchen dresser’ to ‘kitchen sideboard’).

But it’s not just best-selling fantasy series that get tweaked for different publishing markets. If you happen to have read both the Australian and the North American editions of my first Montmaray book (and I’m not sure why you would have, but anyway), you might have noticed that they’re different books. I don’t just mean they have different covers. The words inside the covers are quite different.

There are a couple of reasons for this. Firstly, the North American edition of A Brief History of Montmaray came out more than a year after the original Australian edition, which gave us time to fix up some things that needed fixing. I trimmed the first section of the book, because the pacing was a bit slow (some people still think it’s too slow). I threw out the final chapter and rewrote it. There was also a scene that I thought could be more exciting and dramatic, so I rewrote that – which meant I also needed to change the location of one particular building, which led to minor changes in other parts of the book.

Then there were a lot of ‘But American teenagers won’t understand this!’ changes. Sometimes I went along with my American copy-editor’s suggestions, and sometimes I didn’t. For example, I was advised to take out some of the real history, because American teenagers would find it confusing or boring. Maybe they would, but Australian teenagers had managed to understand those bits. Are Australians smarter than Americans? I don’t know, but generally, I think teenage readers (especially the ones who choose to read long historical novels) are pretty smart. If they come across something new, they’ll use context to get the general idea of what it means. Or they’ll Google it. Or they’ll ask someone. Or they’ll just keep reading, figuring that if it’s important, there’ll be more about it later on in the book. At least, that’s what I do when I come across something unfamiliar in a book – which happens all the time to me. What’s the point of reading if you only read about stuff you already know?

Apart from the historical facts, there was also a lot of arguing about particular words. For example, in Australia, a ‘jumper’ is a long-sleeved top, usually knitted from wool. But for Americans, a ‘jumper’ is a collarless, sleeveless dress, worn over a blouse. Our ‘biscuit’ is an American ‘cookie’, whereas what Americans think of as a ‘biscuit’ would probably be called a ‘scone’ here. In the case of the Montmaray books, the vocabulary issues were complicated by my narrator speaking a posh 1930s version of British English. Sophie didn’t say ‘toilet’, ‘perfume’ or ‘mantlepiece’ – she said ‘loo’, ‘scent’ and ‘chimneypiece’. Having done a lot of research to ensure her language was authentic, there was NO WAY I was going to have Sophie suddenly talking about ‘cookies’ and ‘sweaters’. On top of that, the US edition had to use American spelling and punctuation, which is different to Australian (and posh 1930s British) spelling and punctuation.

The good news for me was that, just as with the Harry Potter series, my editors asked for fewer changes as the series went on. Maybe they figured that readers who’d made it through the first book would be able to cope with the characters eating ‘biscuits’ rather than ‘cookies’, and using ‘torches’ rather than ‘flashlights’, and so on. Or maybe my editors just got tired of arguing with me. Anyway, the final Montmaray book is pretty much the same book, no matter where in the world you happen to buy it. Apart from the spelling and the punctuation. Don’t get me started on how Americans use commas…

Next: Life in Wartime. Keep Calm and Carry On!