Devdutt Pattanaik's Blog

June 15, 2019

Is Shiva the corporate destroyer or Kalki?

Art by Devdutt Pattanaik

Published on 15th June, 2018, in Economic Times

Kalki, the tenth avatar of Vishnu, is very popular amongst young people, who visualise him as an Avenger, part of a cosmic end game. He is visualised as riding a white horse, brandishing a fiery sword, cutting down people. The story about Kalki is not very wellknown; but the general belief is that he destroys bad people and restores the good world order, very much like a superhero. However, that is not the case.

The tenth avatar of Vishnu is seen as the form before Pralaya. He is mentioned first in Mahabharata and is linked to Parashurama, who kills unrighteous kings. His story is elaborated primarily in the Puranas and shows influence of Zoroastrian and Christian messianic ideas. But there is another destroyer in Hindu mythology and that is Shiva. Shiva is part of the Hindu trinity, and in popular understand these three forms of divine are responsible for Generating, Operating and Destroying the world (hence English acronym GOD, as per whatsapp forwards).

But is there a difference between Shiva, the Destroyer, and Kalki, the Destroyer? The confusion arises because Kalki is supposed to be a form of Vishnu also known as the Operator or preserver or sustainer. An understanding of this difference helps us understand the value of destruction in life.

In Hindu mythology, Brahma creates the world; therefore, he is associated with desire. He is visualised as a priest. Desire is expressed as and when the ritual performer expresses his sankalp, or intention, for conducting the ritual. While Shiva rejects rituals, he also rejects all things material. He wants nothing and so expresses no Sankalp. He is visualised as a hermit, as someone who destroys desire, and walks away from the life of a householder. He will not create an organisation. He does not see the value of creating a world that ultimately indulges the ego. Vishnu, on the other hand, is the preserver of culture, rituals and social structure, thereby restoring order. His actions attract Lakshmi (affluence and abundance). He places desire in context, and does not let it go out of hand.

The Hindu Trinity is not involved with nature ( prakriti) which is visualised as the Goddess, hence eternal; they are creating, sustaining or rejecting culture ( sanskriti). That is why destroyer Shiva who has no desires is visualised as a hermit smeared with ash, and the preserver Vishnu who does not reject desire is visualised as householder, with silk and sandal paste.

Why then does Vishnu destroy things? He destroys things, in the form of Kalki, when people stop respecting dharma, in other words, when humans behave like animals: territorial and dominating, more interested in being alphas than helping the omega. When people become dominating and territorial, the existing society needs to be destroyed and a new structure must be formed. We see Vishnu struggling to maintain the social order, in various forms: as Parashurama, Ram, and Krishna. But when everything fails the entire system, the entire edifice of the structure of society must be destroyed, and Vishnu shall do this as Kalki.

Organisations are built by people who have the desire to achieve something. This desire makes them Brahma, the creator of the organisation, but when their desire ceases and they let go of the organisation and they become Shiva, the destroyer.

Many leaders are so busy creating and desiring, they do not often wish to let go. This is the reason they don’t delegate, they don’t retire and they do not allow companies to move on without them. These leaders cling to their Brahma role, which creates chaos and disorder, necessitating the arrival of a Kalki, who, to save the organisation, needs to get rid of such leaders, and change the old order to a new system.

Shiva builds not organisations. He inspires leaders to let go of their attachment to organisations and retire, having realised the futility of ambition and success in the larger context. A Kalki on the other hand gets the old order forcibly dismantled to usher in a new era. He marks the transition from Kali-yuga (decline phase of organisation) through Pralaya (turmoil of restructuring) to Krita-yuga (golden phase of resurgent organisation).

June 10, 2019

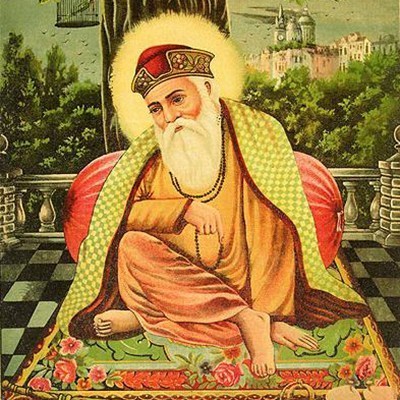

Where Hinduism and Sikhism meet

Source: Wikipedia Commons/Artist: Raja Ravi Varma

Published on 9th June, 2019, in Mumbai Mirror

WHO IS A HINDU?

If you ask a Hindu extremist, he will say that Sikhism is very much a dharmic religion like Hinduism, under the umbrella term, Sanatan Dharma. However, if you speak to a Sikh extremist, especially in the UK and Canada, he will deny this, completely. This division has been especially amplified since the tensions between the Indian state and the Sikh community in the 1980s. In the West, most white people confuse Sikhism with Islam as beards and ‘turbans’ are seen as common. Extremists always follow simplistic, binary concepts.

They cannot, and will not, understand the complexities of history and the origins of how religions evolve, over time, based on political and economic realities. Sikhism, in India, started more than 500 years ago, in an ecosystem where Hinduism had to cope with the arrival of a new religion called Islam, which entered the country, from the north-west, in a violent form, under the aegis of newly converted Central Asian warlords. This was much later and very different from the Islam that came via sea-faring merchants in the south. Sikhism manifested at the intersection of Hinduism and Islam and shows characteristics of both religions, yet maintains its own unique flavour.

Sikhism did not manifest in a single day; but over several generations. The first founder is identified as Guru Nanak, who travelled across India, and was deeply influenced by both the Bhakti and Sufi Movements. Hindu-friendly scholars will say that it was Bhakti that shaped Sikhism, while Hinduphobic scholars will tend to insist that it is Sufism that influenced the religion.

Politics aside, Sikhism is based on the idea of karma, or rebirth, but believes that, if you follow the Sikh way, or dharma, as explained in Sikhism, one will attain moksha, an idea also found in some Buddhist schools. These concepts of dharma, karma and moksha are key to Hindu beliefs too. Sikhism also values the sound Om. Omkar (venerated by Hindus, Buddhists and Jains) refers to the divine in Sikhism. The holy book ofSikhs, Shri Guru Granth Sahib, is a collection of Bhakti songs, from various poets of the time, from Kabir to Ravidas to Namdeo. The idea of a holy book comes to India via Islam; before that, Indians valued the oral over the textual, the fluid over the fixed. The Sikh practice of remembering God’s name (Simran, from the Sanskrit smaran) has roots in Bhakti and the importance of service (seva) makes Sikhism far more social and fraternal, much like Islam, than caste-based Hinduism.

Unlike Hindus, but like Muslims, Sikhs shun imagery. God in Sikhism is nirgun (formless). Sikhism is staunchly monotheistic, like Islam, though Sikh writings do reveal veneration of Krishna (Govind, Hari, Bitthal), Ram and Durga (Chandi) as well as Allah in the spirit of unity with all faiths, a hallmark of BhaktiSufi practices. In Sikhism, caste is completely rejected and genders are considered equal. A man who follows Sikhism is called Singh and a woman is called Kaur, meaning tiger and tigress, respectively.

Like in Islam, there is a code of conduct called the Rehat Nama or Rehat Maryada. Over time there has been a separation of religious affairs, Piri, from secular affairs, Miri. The vicious persecution of Sikh gurus by Mughals in 17th century played a key role in consolidating the Sikh identity, especially the rise of the Khalsa (the pure ones) who embraced martial arts and military discipline to protect the faith.

Until about a hundred years ago, divisions between Hinduism and Sikhism were not so sharp. Many of the gurudwaras, where the holy book was kept, and where people gathered to pray, were managed by mahants of the Udasin order. Udasinta means indifference. They trace their lineage to Sri Chand, who was the son of Guru Nanak. Although Guru Nanak believed in the life of a house-holder, Sri Chand believed in celibacy and asceticism. The Udasin Mahant order did not differentiate between Hinduism and Sikhism; they also believed in idolatry, and they worshiped Vishnu, Shiva and other Hindu gods. They played an important role in spreading Sikh thought in 18th and 19th century. But in the 1920s, the Khalsa Akali movement took place, a kind of a reform movement which urged Sikhs to reject casteism and idolatry. Very slowly, committees were formed, whereby Sikhs created democratic institutions, to manage the gurudwaras, and the Udasin babas were side-lined. Some believe the British facilitated this as part of divide-and-rule policy.

So, one can see in Sikhism the influence of both one-life ‘book’ religions, as well as karmic religions. Today, of course, Sikhism is a religion in its own right, with its own reading of faith, enshrined in the Constitution just like Buddhism and Jainism – extremists notwithstanding.

June 9, 2019

Yoga Mythology: 64 Asanas and Their Stories

Yoga Mythology: 64 Asanas and Their Stories

The popular names of many yogic asanas – from Virbhadra-asana and Hanuman-asana to Matsyendra-asana, Kurma-asana and Ananta-asana – are based on characters and personages from Indian mythology. Who were these mythological characters, what were their stories, and how are they connected to yogic postures?

Devdutt Pattanaik’s newest book Yoga Mythology (co-written with international yoga practitioner Matt Rulli) retells the fascinating tales from Hindu, Buddhist and Jain lore that lie behind the yogic asanas the world knows so well; in the process he draws attention to an Indic worldview based on the concepts of eternity, rebirth, liberation and empathy that has nurtured yoga for thousands of years.

Buy from:

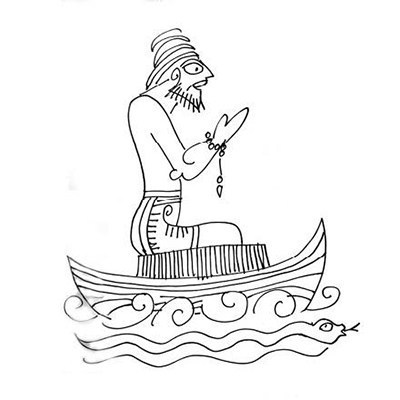

Sea-faring Kaundinya

Art by Devdutt Pattanaik

Published on 8th June, 2019, in Mid-day

If you travel to Cambodia, you will come across a folklore that a sage from India known as Kaundinya travelled across the sea to what is now called Cambodia, where he encountered a Naga princess, who fell in love with him. She happened to be the ruler of the local people and married Kaundinya. From them descend the kings of the Kingdom of Kamboja, which later came to be known as Cambodia. Was this Kaundinya Hindu or Buddhist? We really don’t know. In fact, in ancient times, in faraway lands, few differentiated between the two.

In Hindu mythology, Kaundinya does not play an important role, although he is recognised as one of the sages who travelled from the northern part of India to the southern part of India and over the sea to Southeast Asia. So, he is linked with the transmission of Vedic beliefs and practices, across the subcontinent and beyond.

Kaundinya plays a much bigger role in Buddhist mythology. When Siddhartha Gautama is born in the Sakya clan, many sages predicted that he may either be a sage who gives up the world and discovers wisdom, or he will become a great king who will conquer the world. Kaundinya is the only sage to insist he will never be a king but a hermit and he vows that he will be a follower of the hermit. Years later, when Siddhartha gives up his kingdom and goes to the forest and lives the hermit’s life, Kaundinya and his student follow him, but only until the day Siddhartha refuses to practise self-mortification. When Siddhartha returns as the awakened one or the Buddha, Kaundinya follows him once again and plays an important role in the establishment and spreading of the Buddhist thought across the world.

In Buddhist literature, we often hear that just as Buddha had previous lives, so did Kaundinya and they did engage with each other. In one story, we are told that the Buddha-to-be was a tiger and Kaundinya was a tigress and Buddha-to-be offered his own life so that the hungry tigress would not eat her own cubs. In another story, Kaundinya was shipwrecked. Desperately, he looks to the generous king of Kosala, only to discover that he has abandoned the kingdom and given the kingdom to the king of Kashi to avert war. When Kaundinya meets the king of Kosala in the forest, the king of Kosala says if you give me to the king of Kashi, he will give you a reward, which you can use to restore your business. And so, Kaundinya takes the Buddha-to-be, i.e., the king of Kosala to Kashi, and seeks the reward. The king of Kashi is impressed by the generosity and compassion of the king of Kosala and restores him to the throne. With his kingdom restored, the king of Kosala gives the merchant all the wealth he needs to restart the business. Thus, Kaundinya is associated with seafaring merchants in Jataka itself.

June 3, 2019

The sorcery of Harut and Marut

Art by Devdutt Pattanaik

Published on 2nd June, 2019 in Mid-day

In Middle Eastern (aka Islamic) mythology, when god created Adam, he expected all the angels to bow down before Adam. The angel, Iblis, refused to do so. Therefore, Iblis was cast out of paradise. He became the Devil, or Shaitan, who was determined to tempt humankind and make their life miserable on earth. His aim was to prove to god that his creation was faulty and that god’s anger on him was misplaced.

Two other angels, known as Harut and Marut, saw the follies of man. They kept asking god how he could place a creature of clay over angels, who are creatures of light. God challenged them to go down upon earth and do better and not succumb to temptations. The two angels took up the challenge and descended upon earth. They roamed around and resisted all forms of temptations, whether it was alcohol or womanising, until they met a woman called Zohra, who they fell in love with. They wanted to be intimate with her, but she refused, unless they consumed alcohol. In a state of inebriation, they also revealed to her the sacred name of god, and she became intimate with them. Using the secret name of god, Zohra rose to the heavens and became the planet, Venus.

When they came to their senses, Harut and Marut realised they were no better than humans and apologised to God for their mistake. God offered them a choice: eternal damnation or life on earth, suffering separation from God until the world ended. They chose the second punishment and they were hung upside down, in the city of Babylon.

Since they had access to the occult arts, many people who travelled to Babylon, met these two angels and asked them to teach black magic. The angels would always warn of the knowledge of magic as a temptation, which should be rejected in favour of faith in God. If one persisted, they revealed to him the black magic.

In other Middle Eastern mythology, the many angels who followed Iblis to tempt humankind were known as the shaitans. They would hear the whispers of angels in their own realm that gave them access to secret, unseen knowledge about the future, which they would share with humans. Finally, God gave Suleiman, the king of Israel, the power to control and enslave these shaitans, making use of their magic to build his temple. All their knowledge and prophecies, Suleiman wrote down in a book and hid under his throne.

After Suleiman’s passing, the demons figured out where the book was hidden. They found it and spread its knowledge around the world. However, it was in a garbled language, tough to decipher.

In another story, a sorcerer disguised himself as Suleiman and managed to get access to Suleiman’s library. He took away the knowledge related to the mystical and occult arts and shared it with humans, but they could not understand it completely. Therefore, all their magic remains faulty and not as accurate as Suleiman’s.

June 1, 2019

War-room culture celebrates violence where competition is seen as the enemy

Art by Devdutt Pattanaik

Published on 31st May, 2019, in Economic Times

Many corporate houses love to have a ‘War Room’ in their office. It is a glamorous and much publicised thing whether you are planning a new strategy or have a special project that needs to be done quickly, often a turnkey project, a market intervention, even an emergency.

An interdisciplinary, interdepartmental room, where quick decisions are taken, as in a war situation, becomes the need of the hour. There are charts put on the wall, post-its everywhere, lots of pens, whiteboard markers, and intense discussions to win! But why is a war metaphor used for business? Why is business seen as war? Why does modern management valorise a violent mindset so?

The history of management reveals that modern ideas of management forces come from, primarily, two sources. One source is from military traditions, traced to the Roman army, right up to colonial times, when training and logistics evolved into a fine art to ensure victory. The second is from Christian missionary activities that measured the strategy, implementation and success of harvesting souls in different parts of the world. In both cases, one sees the language of violence: penetrating the market, grabbing a market share, dominating a market, crushing the competition, phrases we use, today, so casually.

Then one talks about what kind of a culture we are creating in organisations. An organisation which creates a war-room culture, clearly, celebrates violence. It is most interesting that the owners of such companies subscribe to non-violent religions, allegedly, and insist on vegetarian canteens. The idea of war and the thrill of defeating the enemy is exciting enough to become the easiest form of inspiration in the world. Politicians have figured it out long ago. Businessmen do it, too, where the competition is seen as the enemy. Victory is followed by largesse. We call it Corporate Social Responsibility.

Wars are of different types. For Greek mythology we have the famous Trojan war that was fought to get back from the rich city of Troy what they had stolen from Sparta, a queen called Helen. In that vein, we can have a strategy to reclaim customers that we thought were ours, or to reclaim talent that has been taken away by someone else. Then there is the Titanomachy, where the Olympian gods defeated the Titans, who had defeated the Giants earlier. In other words, a strategy to overthrow market leaders, through brute force (pumping in resources), trickery (manipulating regulations and policy) and ambush (surprising the market).

Another kind of war from the Bible is where the chosen tribe travels to the promised land and claims the land, because of God’s word, from the original residents.

This comes from a sense of entitlement, since it comes from God. So, it is you, basically, entering a hostile, alien market, and seeking space in that market. You have regulatory authorities, government and politicians working against you, while you try to penetrate this antagonistic ecosystem. This fills the war room team with a sense of righteous heroism.

The Mahabharata war is, of course, the war in which brothers fight over property. Each one thinks that the property belongs to them: this, we see, in a lot of business families. War room strategies designed especially with lawyers sitting there to divide the father’s property.

The idea of seeing business in violent terms is perhaps the reason why we see investment bankers being rather cocky, brutish and aggressive, revelling in irreverence, and why young MBA graduates are encouraged by peers to be brash and arrogant, trivialising the old school.

The idea of compassion and contentment is not taught in business schools around the world. That we are told is for losers, or after retirement, or for stress relief, like massaging warriors at night before they resume battle at dawn. Spirituality may value ‘letting go’, but motivational speeches in all corporates always speak of ‘never giving up, clinging on, no matter what’. And we expect our CEOs to care for the ecosystem or for rising inequality and unemployment?

May 26, 2019

A temple for a dog

Art by Devdutt Pattanaik

Published on 26th May, 2019, in Mid-day

In the state of Chhattisgarh, in Khapri village in Durg district, there is a temple dedicated to a dog. It is called Kukur Dev. The story goes that there was once a banjara (gypsy) who had a dog. During a famine, he had no money, so he gave up his dog as collateral to a moneylender. One day, there was a theft in the moneylender’s house. The dog saw where the thieves hid all the stolen goods and dragged the moneylender to the place, who retrieved the stolen goods. The moneylender then wrote a letter to the banjara, expressing his gratitude for the dog, and further stated that he had written off all the debts owed by the banjara. He tied this letter to the dog’s neck and sent him as a messenger to the banjara. However, when the banjara saw his dog coming back from the moneylender’s house, he beat the dog so hard with a stick that the dog died. After the dog died, the banjara saw the letter around the dog’s neck and realised what had actually happened. In sorrow and remorse, he built a temple, in the memory of the dog called the Kukur Samadhi.

This eventually became a Shiva temple, dating back 500 years, built by the local kings, for dogs are closely related to Shiva. The temple has the reputation of being Rinmukteshwar, where one is liberated from debts. Legend has it that Adi Shankaracharya came to this location to be free of all the debts he owed his guru.

Dogs are associated with Yama, who is the keeper of dharma. One of the meanings of dharma is the obligation of human beings to repay debts to ancestors, sages, gods, nature and society. As long as we are in debt, we are forced to be reborn and be a part of the cycle of birth and death. Only when we repay these debts are we liberated from the cycle. A dog’s association with death is the reason Shiva, in his Bhairava form, is associated with dogs. Dogs are generally considered inauspicious in Vedic tradition, but they are linked to ascetics like Dattatreya. And in Nepal, with its strong tantric leanings, there is a festival of dogs, Kukur Tihar, linked to Diwali, and Yama Dvitiya. In Gujarat, Vaghri Devi Pujaks worship Hadkai

Mata, who rides a dog to protect them from rabies.

A dog’s attachment to its master is a symbol of bondage. It becomes a metaphor for our attachment to the material world. How we free ourselves from this bondage is the question. The practice of yoga and bhakti is supposed to be the method by which we can be liberated from debts.

A dog’s loyalty, in a way, is a way of a repaying its debt to his master who feeds him. He loves his master and protects his master. By this, we are reminded of the obligations that we owe to other people in our society, to whom we are supposed to be loyal, and whom we have to protect. This is but one of the many interesting stories we find in India that connect animal life with high philosophy.

May 19, 2019

Narada, the cursed

Art by Devdutt Pattanaik

Published on 19th May, in Mid-day

In the Puranas, we are told that Narada, the mind, was born from the thoughts of Brahma, and like all sages had the knowledge of Brahma vidya, or the ultimate truth of the world. He would go around the world sharing this knowledge and enabling people to break the cycle of birth and death.

The problem was he went around divulging this knowledge to every son born of Daksha Prajapati. These sons, therefore, refused to marry, produce children, become householders and practise their vocation. Instead, they chose the path of renunciation, becoming hermits and ascetics. They began working towards moksha, because that is what the ultimate role of life was. Or at least, that is what they believed.

This made Daksha Prajapati very angry. He cursed Narada in his anger. Since Narada was the one who was telling everyone how to achieve moksha, Narada would not achieve moksha himself. Instead, he would forever wander between the realms: the celestial, the earthly and the subterranean realms, until the end of time.

We are told Narada remains travelling around the world to make people realise the limitations of worldly life, so that, eventually, they discover the path to god. And so, Narada is associated with creating quarrels. He goes around the world making mischief. He seems to be involved in spreading information, like a newspaper journalist; but he, continuously, compares and contrasts people. In doing so, he creates jealousy, anger and rage, all the things that indulge the ego. He, thus, plays an important role in storytelling. He becomes the catalyst of the plot. It is because of him things happen. He goes and goads Kansa to kill Devaki’s children. He goes to Ravana and extols to the demon-king the beauty of Sita.

But he is also associated with bhakti. He goes around singing songs of Vishnu. He propagates and tells people about the glory of Vishnu. For many people, Narada is a musician, and is, therefore, associated with the tambura. He is the original founder of kirtans and bhajans and plays a key role in Bhakti Yog.

So, this dual character, at one level, creates quarrels, which entrap us in the worldly life and in the material world; and, at another, manifests the spreading of the song and music of the lord, which helps us break from the material world. He does both these things, as he wanders between the three realms, instigating battles, disagreements and discord.

He often encounters Krishna in Dwarka, and the two are part of many adventures. In their adventures, humans discover the importance of bhakti and how bhakti enables a householder to live like a hermit and, eventually, attain Brahma vidya and break free from the cycle of life and death, without abandoning worldly duties.

May 12, 2019

Suleiman and the djinns

Art by Devdutt Pattanaik

Published on 12th May, 2019, in Mid-day

The right-wing communities around the world have one common feature: they believe there is only one truth and that truth is theirs. Therefore, they have a problem with other mythologies and science. This is true as much of Hindu/Christian/atheist radicals as it is of Islamic radicals. This stems from the assumption that mythology has something to do with falsehood (a 19th-century colonial definition), rather than cultural truths (a 21st-century postmodern definition).

A key figure in Islamic mythology popular across the Middle East is King Suleiman (Solomon of Old Testament). Suleiman was the third king of Israel and the son of Dawood (David). He was known as a wise king and the builder of the temple, where the arc of the covenant was housed. No matter how rich and powerful and famous he became, he never forgot to pray to Allah.

Allah gave Suleiman the power to understand the language of animals. He never understood why Allah had given him this gift until one day, when his army was marching, he heard ants talking of his approaching armies and learned of their fear of getting crushed by his battalions. Suleiman then directed his army on to such a path that the colony of ants was not harmed, thanking Allah for making him hear what no human could, and enabling him not to hurt innocent creatures accidentally.

Suleiman was also known as the great magician, who had full control over the djinns. Djinns are considered to be malevolent and benevolent spirits that were invoked in pre-Islamic mythologies. Allah, say the keepers of folklore, created djinns out of fire, angels out of light, and humans out of clay. God decreed that all must bow to the first human, Adam. Most angels agreed and so were given a place in heaven. A few refused, the leader of them being Iblis; they were the shaitans. Shaitans include Satan as well as demons. The djinns refused to bow to Adam, because they were convinced they were greater, because they had knowledge of the unseen and the future, in other words, mysticism and fortune-telling.

To teach them a lesson, Allah gave Suleiman complete control over them. Using spells, Suleiman could make them do his bidding. He could make them fly with his army and overpower his enemies. Thus, Suleiman was able to conquer vast lands and build fabulous palaces and structures in his lifetime. Even in later periods, when a magnificent temple was encountered by Muslim warlords in other countries (which they did not break down), it was admired and considered to be the work of Suleiman’s djinns.

Suleiman died while he sat on his throne. His corpse remained there, erect, holding his staff and nobody realised he was dead. Days later, when termites broke his royal staff, the dead body tumbled off the throne. Only then did the djinns admitted to themselves that they never had the power to see the unseen or the future. Otherwise, would they have not known that Suleiman was dead? Would they have not stopped following his orders? Humbled, they prayed to Allah, who alone knows what is unseen and in the future.

May 6, 2019

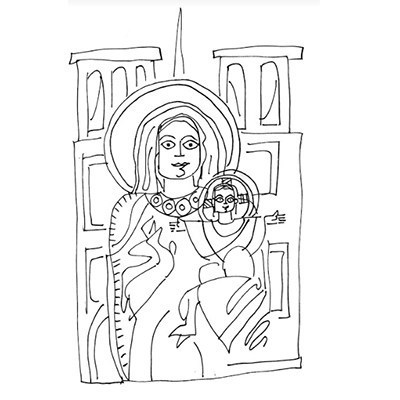

Love for Notre Dame

Art by Devdutt Pattanaik

Published on 5th May, 2019, in Mid-day

Notre Dame means Our Lady in French. Though popular as a name for the most famous Parisian church, which recently caught fire, it refers generally to Mary, Mother of Jesus, who plays an important role in Catholic mythology and in medieval European history.

The New Testament of the Bible mentions that, before her marriage, Mary was told that she was chosen by God to be the vessel through which the Son of God would be born on Earth. Though a virgin, she conceived and became the mother of Jesus. This idea of the virgin birth is critical to Christianity. It establishes Jesus as Christ, the anointed one, chosen by God, to enlighten humanity that they have been forgiven for the sin committed long ago, in Eden, by the first man and the first woman. While many scholars have traced Jesus to a historical figure who lived around 2,000 years ago, his popularity in the Christian world comes from the mythology of being born of a virgin. This idea of virgin birth is found even in Islamic traditions.

About 1,500 years ago, the Roman Empire adopted Christianity as its official religion, as a strategic move to keep its people together. Shortly thereafter, the idea was proposed that Mary should be venerated alongside Jesus, as she was no ordinary woman but the Mother of God. This idea of celebrating and venerating Mary is a primarily Catholic practice and is rejected by the Protestant Church that rose 500 years ago. It preferred to focus on God and Jesus and argued that the worship of the Virgin Mother had nothing to do with the gospels and was a remnant of ancient pagan fertility practices such as worshipping the Egyptian goddess Isis and her son Horus.

Around a thousand years ago, when the Crusades were being fought between the Christian and Islamic worlds over control of the Holy Land, especially the city of Jerusalem, we find several stories of the knight-in-shining-armour and of courtly love, of men who went into battle, defeating dragons and fighting on behalf of women, who they loved deeply. But their love was ‘pure’, meaning non-sexual, involving the spirit, not flesh. This idea of pure love, in which a man fought on behalf of a woman, submitting to her completely and unconditionally, was very popular with the bards of the time. It became a model to the various celibate monks, who fought in the Holy Land, such as the Knights Templar, who fought on behalf of Mother Mary, Our Lady, Notre Dame. It is the model found in 007 films, in which James Bond is willing to do anything for Queen and country.

In this period of the Crusades, the famous Notre Dame church was built in Paris, as much for Mary as for Jesus and God. After the French Revolution, which valued liberty and equality and rejected the ‘divine right of kings’, around 300 years ago, this church was completely desecrated by rational and secular forces, who replaced the image of Mother Mary with that of the Lady of Justice. Statues of biblical kings were beheaded because they were assumed to be local kings, who the revolutionaries hated. Later, the church was returned to the clergy and has since remained an important symbol of not just Paris, but Europe’s Catholic legacy.